1. Introduction

Equity gaps refer to differences between groups that violate notions of equity [

1]. They describe “the inequitable treatment of diverse groups” [

2] (p. 377) such as social class [

3], ethnic groups [

4], or gender [

5]. Equity gaps in education occur in many fields, such as reading, sciences, and mathematics [

4,

6,

7], and take a variety of forms, including achievement gaps [

8], excellence gaps [

9,

10], and opportunity gaps [

11].

The design of equity-gap prevention and intervention is complicated by the phenomenon of intersectionality; that is, individuals can be disadvantaged across multiple gaps by possessing multiple characteristics [

12,

13]. The term “intersectionality” was introduced by the US legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw [

14], who illustrated how the manifold discriminatory experiences black women had were distorted by a one-sided focus on a single category of social inequality such as either femaleness or blackness. However, the intersectionality of the multiple disadvantaged group memberships resulted in discrimination that was “greater than the sum of racism and sexism” [

14] (p. 140). Consequently, the concept of intersectionality can be extended beyond the effects of multiple membership in disadvantaged groups. On one hand, an individual may be disadvantaged in multiple fields. For example, low socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with poorer performance in both language and math skills [

15,

16,

17]. On the other hand, an individual may suffer from multiple equity gaps due to their group membership, and these equity gaps may be mutually reinforcing. For example, compared to female students, male students applying to universities were judged to be more competent (i.e., excellence gaps), and consequently male students received more offers to obtain a mentor (i.e., opportunity gaps) [

18].

Further complicating the issue is that each equity gap has its own history and characteristic causal network [

1]. It is less clear what the common factors across the intersectionality of disadvantaged groups, fields, and types of equity gaps are from an educational perspective. In addition, research on potential causal mechanisms in the emergence and modulation of equity gaps is also lacking. Therefore, our goal is to empirically examine two educational factors that may impact equity gaps among intersectionally disadvantaged groups: social judgments and students’ learning capital. In particular, we seek to establish two causal mechanisms to explain the emergence and potential widening of equity gaps using these factors. Namely, the negative social resonance effect of intersectional disadvantage, which further increases equity gaps that are evident in objective disadvantages via social judgments, and the dampening effect of learning capital on equity gaps, which may help to narrow the equity gap by increasing students’ learning capital. Identifying such factors and mechanisms is of great importance for developing prevention and intervention strategies.

In what follows, we will first introduce the phenomenon of intersectionality among the three affected groups we studied: gender, migration background, and SES. Next, we introduce the negative social resonance effect of intersectional disadvantage and the dampening effect of learning capital on equity gaps.

1.1. Gender

For a long time, research on gender equity focused on females. Important reasons for this were the low participation rates of females in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) and their sometimes-poorer performance in mathematics and science [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Meanwhile, the participation rates in STEM are showing signs of improvement in some fields, but females are still less likely to opt for mathematics-intensive fields such as physics, computer science, or engineering [

23,

24,

25,

26]. In terms of performance in mathematics and science, girls are catching up with boys [

22]. International comparison studies such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) show hardly any differences in the performance of boys and girls, although these vary between countries [

20].

In the meantime, researchers also pay attention to the disadvantages of boys in the education system [

27]. Boys on average perform worse on standardized reading tests, achieve lower grades, and are more likely to drop out of school prematurely than girls [

28,

29,

30]. In particular, boys’ poorer performance in reading, which has been evident for nearly 50 years [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36], has led to discussions about whether schools may not be appropriately designed for boys [

37]. Although the achievement gaps between girls and boys have narrowed over the decades in some countries, PISA data indicate that gender gaps in reading are larger and more persistent than those in mathematics [

7,

38]. Achievement gaps for boys in reading also appear to persist throughout the educational career. International studies found that boys perform worse in reading than girls in the majority of countries in both the International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), which is administered at the fourth-grade level, and in the PISA, which is administered to 15-year-olds [

39,

40,

41,

42]. Longitudinal studies indicate that while achievement gaps in reading narrow somewhat over the course of an educational career, they do not dissipate. Robinson and Lubienski [

27] showed in a longitudinal study from kindergarten to eighth grade that the achievement disadvantage in reading for boys narrowed somewhat over time but remained overall. On the contrary, the gender achievement gap for low-achieving students widened over time [

27].

1.2. Migration Background

International studies point to the importance of migration background for achievement gaps. On average, students with a migration background are disadvantaged in the education system. They perform worse on standardized tests, are less likely to take advantage of institutionalized early intervention, are more likely to leave school without a certificate, and achieve lower levels of educational attainment [

7,

38,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49]. However, the patterns of disadvantage for different groups of migrants vary in different educational systems. For instance, a Turkish migration background is found to be particularly disadvantageous in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, and Norway [

50].

There are also performance differences in reading between students with a migration background and native students. In a quantitative synthesis of PISA and PIRLS data from 2000 to 2009, Andon et al. [

44] found that students with a migration background performed worse in both assessments. Although the authors were able to find a slight decrease in the reading achievement gap over the period considered, the result should be interpreted with caution, as only cross-sectional data were examined [

44].

1.3. Socioeconomic Status

The positive relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and educational attainment is among the most widely documented findings in educational research [

38,

51,

52,

53,

54]. Such a positive relationship between SES and educational attainment was found both in within-country and between-country comparisons [

55,

56]. Furthermore, the achievement gap between students of higher and lower SES families tends to widen as students advance in their education [

57]. The variations from low to high correlations between SES and achievement in different domains found in meta-analyses [

58,

59] can be attributed to various factors such as the way SES was assessed but also to the moderating influences of various individual characteristics such as age, gender, and race/ethnicity, as well as environmental characteristics such as peers’ background or school factors (for an overview [

55,

58]). However, it is important to note that the correlations between SES and academic achievement persist even after controlling for various co-variates.

Moderate-to-high correlations also exist for SES and reading. Children from families with low SES show significantly lower reading skills than their peers from families with high SES [

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]. However, no direct causal effects of SES on reading are evident. Instead, the relationships are often moderated by other variables [

60]. For example, children with low-SES backgrounds are exposed to a less nurturing environment and are less likely to attend preschools, which leads to insufficient acquisition of important preliteracy skills such as phonological awareness and vocabulary [

60].

1.4. The Intersection of Gender, Migration Background, and SES

As discussed above, numerous studies show achievement gaps in relation to gender, migration background, and SES. However, the intersection of two or three of these demographic variables seems to be especially disadvantageous for educational attainment [

64,

65]. Gender gaps in achievement tests are more pronounced among low-SES students [

66,

67]. Furthermore, male students with a migrant background reach lower educational qualifications and competence levels, with disadvantage patterns varying for different groups of migrants [

68,

69,

70,

71,

72]. Similarly, students with a migrant background from low-SES families reach lower educational achievement, including linguistic and mathematical competences [

73,

74,

75], and male students from a lower SES background reach lower educational qualifications and skill levels [

76,

77,

78,

79]. Furthermore, being male with a migrant background and low SES has an especially strong negative impact on educational outcomes [

80,

81,

82]. In a descriptive analysis of the results of the UK national examinations taken by 16-year-olds from 1988 to 1995, Demack et al. [

83] showed that boys with migration backgrounds and low SES consistently achieved the lowest scores and graduation rates. PISA data also indicate that male students with migration backgrounds and from lower SES families have the lowest reading skills [

84,

85]. Therefore, the intersection of being a male, having a migrant background, and low SES seems to be especially disadvantageous for educational attainment.

1.5. Negative Social Resonance Effect of Intersectional Disadvantage

Equity gaps in education have an objective component; that is, disadvantaged groups have restricted access to many resources and opportunities for developing their abilities [

86,

87]. To put this in the framework of the educational and learning capital model [

88,

89], disadvantaged groups have restricted access to educational capital (i.e., exogenous resources in their environment) such as didactic capital (e.g., adequate learning material at home and good schools) or infrastructural capital (e.g., libraries and museums; for more information concerning the five types of educational capital refer to

Table 1).

In addition to these objective factors, various subjective factors are discussed as reasons for achievement gaps. One such subjective factor is social judgements of authority figures (e.g., teachers principals, and school counselors). Studies indicate that teachers’ subjective judgements of students’ performance can differ greatly from students’ performance assessed by standardized tests [

90,

91] and that these judgements tend to be influenced by students’ gender, migration background, and SES, independent of objectively measured performance [

92,

93,

94]. In a longitudinal study from kindergarten to eighth grade, Robinson and Lubienski [

27] found that teachers consistently rated girls higher than boys in both math and reading, even when boys’ performance on standardized tests was better than girls’ performance. Voyer and Voyer [

95], in a meta-analysis based on 503 effect sizes drawn from 369 samples from elementary school to university, also found gender differences in teacher-assigned grades, moderated by nationality and racial composition of samples, among other factors. Similarly, Luedemann and Schwerdt [

96] found that students with migration backgrounds and from comparatively low-SES families received lower grades from their teachers than the other classmates. However, these grade differences could not be explained by differences in PIRLS test scores or student intelligence.

These social judgments form an own reality that might superimpose on or add to objective realities [

97]. Thus, objective disadvantages might resonate in social judgments that once again distort reality according to stereotypes and prejudices. For instance, children with a migration background often have inferior conditions to develop their reading skills [

98,

99]. But, besides this objective disadvantage, their teachers may judge their reading skills less favorably due to their migration status [

100]. Thus, the objective disadvantages may be amplified by subjective biases in teachers’ social judgments. The associated low expectations of the disadvantaged may lead to even poorer performance, known as the Golem effect [

101,

102]. In other words, those who are already disadvantaged are likely to adapt to the low expectations of authority figures (e.g., teachers, principals, and school counselors), which puts them even further below their own ability to perform. This additional disadvantage of social resonating of objective disadvantages is likely to be found in the intersection of group memberships. We will henceforth address this effect as the

negative social resonance effect of intersectional disadvantage. Specifically, it means that teachers, for example, would judge the abilities of intersectionally disadvantaged students even worse than their objective test performance. In summary, this effect may widen the equity gaps even more.

1.6. Dampening Effect of Learning Capital on Intersectionality

Intersectionality describes the phenomenon and consequences for students who belong to multiple disadvantaged groups and how they are denied access to resources and opportunities that are crucial for learning, development, and advancement. Although this does not necessarily mean that these students are generally denied access to resources or opportunities, their capacity to take advantage of the few opportunities and resources that are offered to them may also be limited. To put this in the framework of the educational and learning capital model [

88,

89], intersectionality refers to students who have limited educational capital (i.e., exogenous resources for learning in their environment; for more information concerning the five types of educational capital refer to

Table 1) and lack the learning capital (i.e., endogenous resources within the individual; for more information concerning the five types of learning capital refer to

Table 2) to exploit fully even the scarce resources and opportunities they have. In other words, these students not only lack adequate learning opportunities due to missing didactic or infrastructural capital but they in many cases also lack the motivation (telic learning capital) or learning strategies (episodic learning capital) to use the available resources (i.e., educational capital). However, there might also be a dampening effect of learning capital on intersectionality. In other words, students with more learning capital (e.g., higher motivation and better learning strategies) might be able to reduce the negative effects of missing or scarce resources and opportunities to a certain degree.

In the following we will use the example of gender gaps in reading to illustrate how learning and educational capital interact and how the availability of learning capital might have dampening effects on intersectionality. Boys formally have the same access as girls to reading instruction (didactic capital). But standardized educational curricula have a less advantageous effect on boys’ reading performance than on girls’ reading performance [

103]. Van Hek et al. [

103] explained this finding by suggesting that boys’ reading performance was more strongly influenced by whether they found the reading content interesting [

104]. In highly standardized educational systems, this is often a problem for boys [

105] because reading materials may not be well-matched to their interests and teachers do not have the flexibility to adjust reading materials accordingly. According to the education and learning capital model, in order to stimulate boys’ interest there should have been an adaptation to their interests, but this didactic education capital was not attended to. However, if a boy possesses more learning capital such as a higher interest in learning to read (i.e., telic learning capital) and effective learning strategies to stay focused even when interest is low (i.e., episodic learning capital), he is more likely to excel in the same learning environments of highly standardized reading instruction than boys with less learning capital. This is what we refer to as the

dampening effect of learning capital on equity gaps. In the same sense, the dampening effect of learning capital also applies to intersectionality. Even for students who belong to multiple disadvantaged groups, those who have more learning capital may experience less severe disadvantages. The dampening effect of learning capital on intersectionality thus leads to a mitigation of equity gaps.

1.7. The Present Study

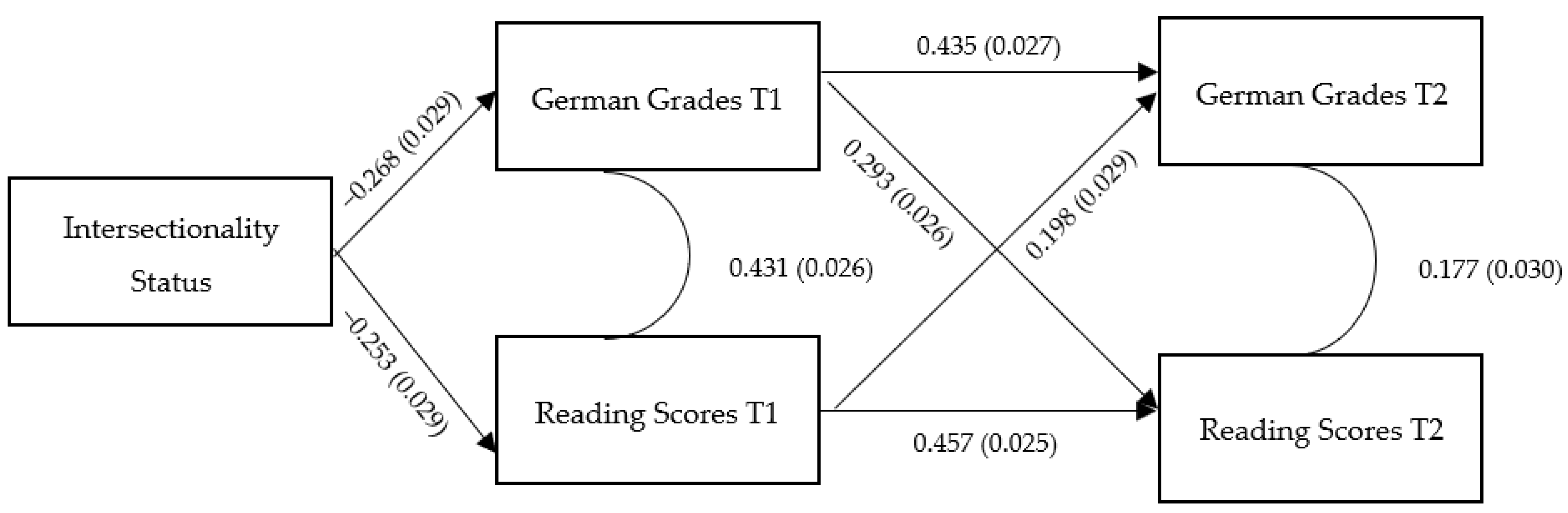

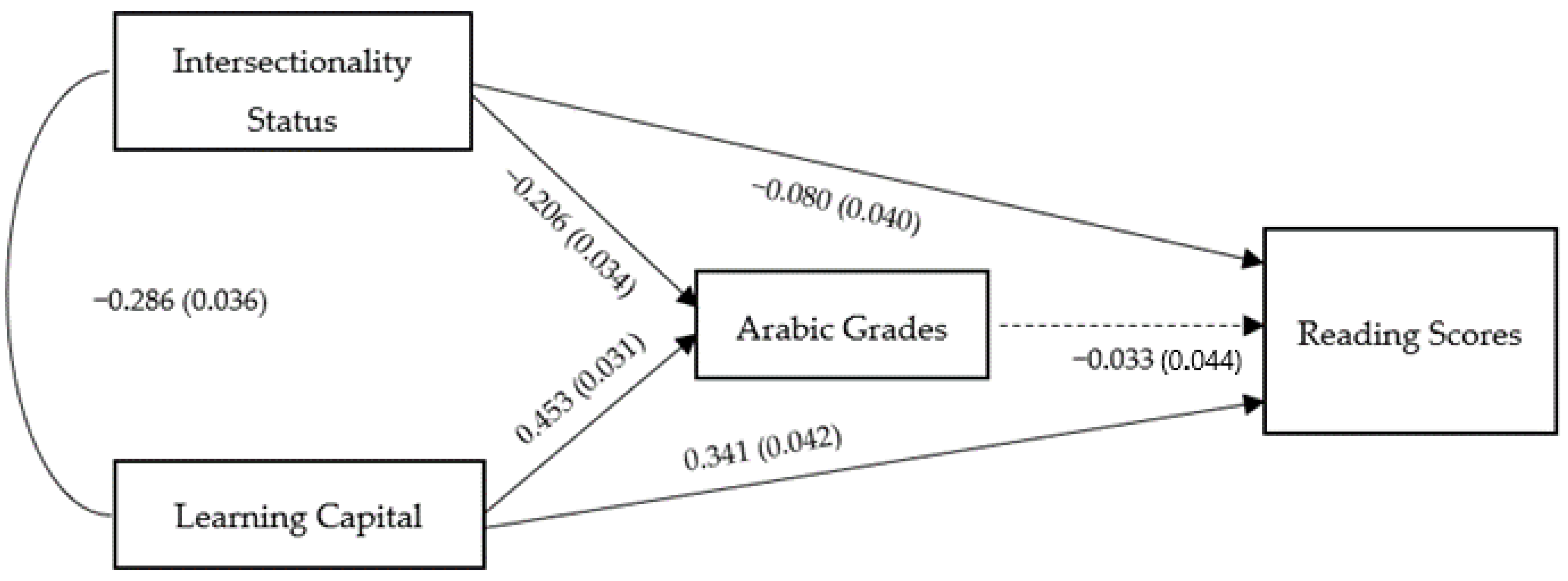

We undertook two studies of intersectionality and explored the two equity-gap modulating effects: the negative social resonance effect of intersectional disadvantage and the dampening effect of learning capital. Male students, students with migration backgrounds, and students with low SES typically exhibit lower achievement in their literacy skills [

7]. Therefore, we assumed in both studies that, first, these equity gaps exist. Second, we expected the equity gaps to be more evident in scores based on teacher judgments of students’ competence of reading comprehension than in objective reading tests (the negative social resonance effect of intersectional disadvantage). We attempted to replicate this effect in Study 2 with a different sample from another culture. In addition, we investigated whether the possession of learning capital can mitigate equity gaps (the dampening effect of learning capital).

4. Discussion

Equity gaps in education are arguably the most central of all educational problems in a world committed to human rights. Numerous research studies have been conducted on the topic [

1,

115,

116,

117]. They have shown equally the universality as well as the multifaceted nature and complexity of this challenge of modern societies. Equity gaps in education occur in many forms, in all domains studied so far, and among a variety of different groups [

3,

4,

5,

6,

8,

9,

11]. To make matters worse, they are localized at different scale levels. For example, many gender gaps can ultimately be traced back to patriarchal social structures [

118,

119,

120] and ethnicity gaps ultimately to racism [

121,

122]. But changing them is beyond the direct reach of the educational system. This is not to say that the education system should not work to overcome outmoded social and cultural structures, but this requires a whole-of-society commitment that extends beyond the education system. To do so, coalitions and alliances must be formed. In this paper, we focus on the phenomenon of intersectionality and on two causal mechanisms that clearly fall within the purview of the educational system, even though their distal causes may lie largely outside the educational system.

We conducted two studies in two countries that differ in many ways. Germany is a typical WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic) country [

123] with a strong educational tradition, whereas the UAE is an emerging Arab nation that has made impressive progress in recent years in establishing a modern education system [

124]. In the last assessments in PISA and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), Germany scored 498 points compared to an average of 487 points in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries on PISA 2018 reading literacy, while the UAE scored 432 points [

7]. On TIMSS 2019, Germany scored 521 and 518 points on mathematics and science (both Grade 4), respectively, above the scale center point, whereas the UAE scored 481 and 473 points, respectively, below the scale center point [

125]. In TheGlobalEconomy.com’s human rights and rule of law index [

126], the average among 177 countries was 5.37 index points (0 = high, 10 = low). Germany ranked among the top nations with a score of 0.80, while the UAE ranked among the bottom 35% with a score of 7.1 [

126]. Despite the diversity of countries, the expected equity gaps between boys and girls, between students with and without a migrant background, and between students with lower and higher SES were found in both samples. In some cases, group memberships interacted. This makes the development of prevention and intervention strategies more complex and increases the need to identify common causal mechanisms in the emergence of equity gaps.

The main objective of the two studies was to investigate two causal mechanisms that can modulate equity gaps. The first causal mechanism, the negative social resonance effect of intersectional disadvantage, further increases equity gaps that were already evident in objective disadvantages via social judgments. Those affected by equity gaps experience multiple disadvantages, including exclusions from learning opportunities and less access to learning resources [

1]. A crucial consequence is poorer learning outcomes [

127,

128]. This is bad enough; however, when access to learning resources and further learning opportunities is contingent on social judgments, further disadvantages can be imposed. When persons making these judgments are themselves a part of the educational system, the educational system has a responsibility to address and eliminate the source of disadvantage. In the present study, we were able to show that students from certain groups (male, migration background, and low SES) were already at a significant disadvantage when it comes to reading comprehension, as measured by test performance. The negative social resonance effect of intersectional disadvantage exacerbated the equity gaps: the equity gaps were even more pronounced in teachers’ judgments, as reflected in students’ grades in the subject. Our findings are consistent with other research. For instance, teachers make career recommendations [

129] according to disadvantaging stereotypes despite objectively equal student achievement. This is a source of equity gaps that appears avoidable. Teacher preparation and training can help reduce teachers’ bias, and providing teachers with more objective diagnostic tools is also critical [

130,

131,

132]. It is also important to consider how we measure students’ reading comprehension (e.g., multiple-choice tests, retelling what they read, and writing a summary), as there are also equity gaps in the ways we assess students from varying backgrounds.

The second causal mechanism we examined was the dampening effect of learning capital. The framework of educational and learning capital illustrates that equity gaps are due to both exogenous and endogenous factors. Those affected have less educational capital; that is, access to exogenous resources such as materials, devices, and institutions for learning. Furthermore, they lack learning capital (i.e., endogenous resources) to take advantage of the limited exogenous resources they have [

133]. This results in a double responsibility for modern societies and their specialized subsystems (educational, political, legal, economic, and cultural). They have to ensure that all those concerned are (or can be) equally provided with educational capital. This is not even close to being achieved in any society in the world, as the many equity gaps show. The second responsibility is to ensure that everyone can draw equal benefit from educational capital. We addressed this obligation in Study 2. The results show that students can capitalize from the same amount of educational capital depending on the amount of learning capital available to them. This has enormous educational consequences and requires a strategic rethink.

Equity gaps have often been associated with underprivileged groups having less access to resources and opportunities, and closing these gaps helps restore equity [

134,

135]. However, the dampening effect of learning capital found in Study 2 shows that the strategy of equal opportunities and resources runs up against an obvious limit defined by differential learning capital possession. Rather, in the reality of education, there is a reasonable possibility that equity gaps are steadily widening in line with a Matthew effect [

136]. Indeed, at its core, the Matthew effect is defined in such a way that some subgroups (who already possess more) benefit disproportionately from identical educational opportunities compared to other subgroups. Thus, equity gaps, once formed, can become increasingly pronounced. Such cumulative effects have already been shown empirically [

137] as well as theoretically thoroughly discussed [

138]. In order to close equity gaps, it is therefore necessary not only to ensure that at least as many exogenous resources reach the disadvantaged as the privileged, but also to ensure that they have the capacities to use them for successful learning and development processes. With the dampening effect of learning capital, the educational starting points are identified by the five learning capitals. For example, if boys conform to the stereotype of the non-reading male gender in the media and at home [

139,

140], schools can try to provide appropriate telic and episodic learning capital (e.g., via a reading curricular also tailored to boys’ interests or reading strategy training). If children with a migration background are inhibited by language barriers, appropriate actional and episodic learning capital (e.g., via language courses and joint project work with natives) might be provided.

Limitations and Future Research

There are several limitations to the design of the present studies and findings. First, both studies were questionnaire studies. Thus, all the limitations of questionnaire studies such as the accuracy of the responses due to the self-reported nature can be a problem. For instance, students may not accurately assess the number of books in their household in Study 1. Similarly, teachers’ assessment of each student’s economic educational capital in Study 2 may not reflect the actual economic capital a student had. Furthermore, in both studies, we used a proxy measure for SES. We used the number of books in the household to gauge SES in Study 1 and teachers’ assessment of economic educational capital as a proxy for SES in Study 2. Even though studies show that books in the household, as well as economic educational capital, are strongly correlated with family’s SES [

141,

142], it would have been better to use a composite measure for SES, such as the Duncan Socioeconomic Index or the Nam–Powers Occupational Status Score [

143,

144].

Further, Study 2 was a cross-sectional study in which students’ test scores and grades were both examined at the same time. Therefore, no causal conclusion could be drawn. It would have been more ideal to collect data at multiple time points as in Study 1 and compare the predictive power of teachers’ subjective judgment and students’ previous test performance on their later test performance and course grades. Still, Study 2 was able to show the dampening effect of learning capital for intersectional disadvantages on students’ literacy achievement. The initial findings have value for the practice and policy for narrowing equity gaps by equipping students subject to intersectionality with learning resources. Future research on the dampening effect of learning capital on intersectionality and equity gaps should also plan and implement a longitudinal study.

Another limitation of our study is that there was no objective measurement as a substitute for the subjective school grades in native language education given by teachers. Course grades of a native language class may include multiple aspects such as spelling, reading, and creative writing. Although one can argue that reading is among the most important sub-skills and that it is often correlated with all other literacy sub-skills, future research should nonetheless employ additional objective testing procedures that measure other facets that go into a native language classroom grade. Our prediction is that all sub-scores will show smaller equity gaps than in the native language grade, as they are amplified by the social resonance effect.