Academic Self-Efficacy and Value Beliefs of International STEM and Non-STEM University Students in Germany from an Intersectional Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Expectancy and Value Beliefs

1.2. Differences in Expectations and Value Beliefs by Gender and Parental Academic Background

1.3. Expectations and Value Beliefs and Cultural Characteristics

1.4. Intersectionality

2. Purposes of the Present Study

2.1. Relations with Gender

2.2. Relations with Parental Academic Background

2.3. Interactions of Gender and Parental Academic Background

3. Method

3.1. Sample

3.2. Instruments and Scales

3.3. Analytical Strategy

3.4. Power Analyses

4. Results

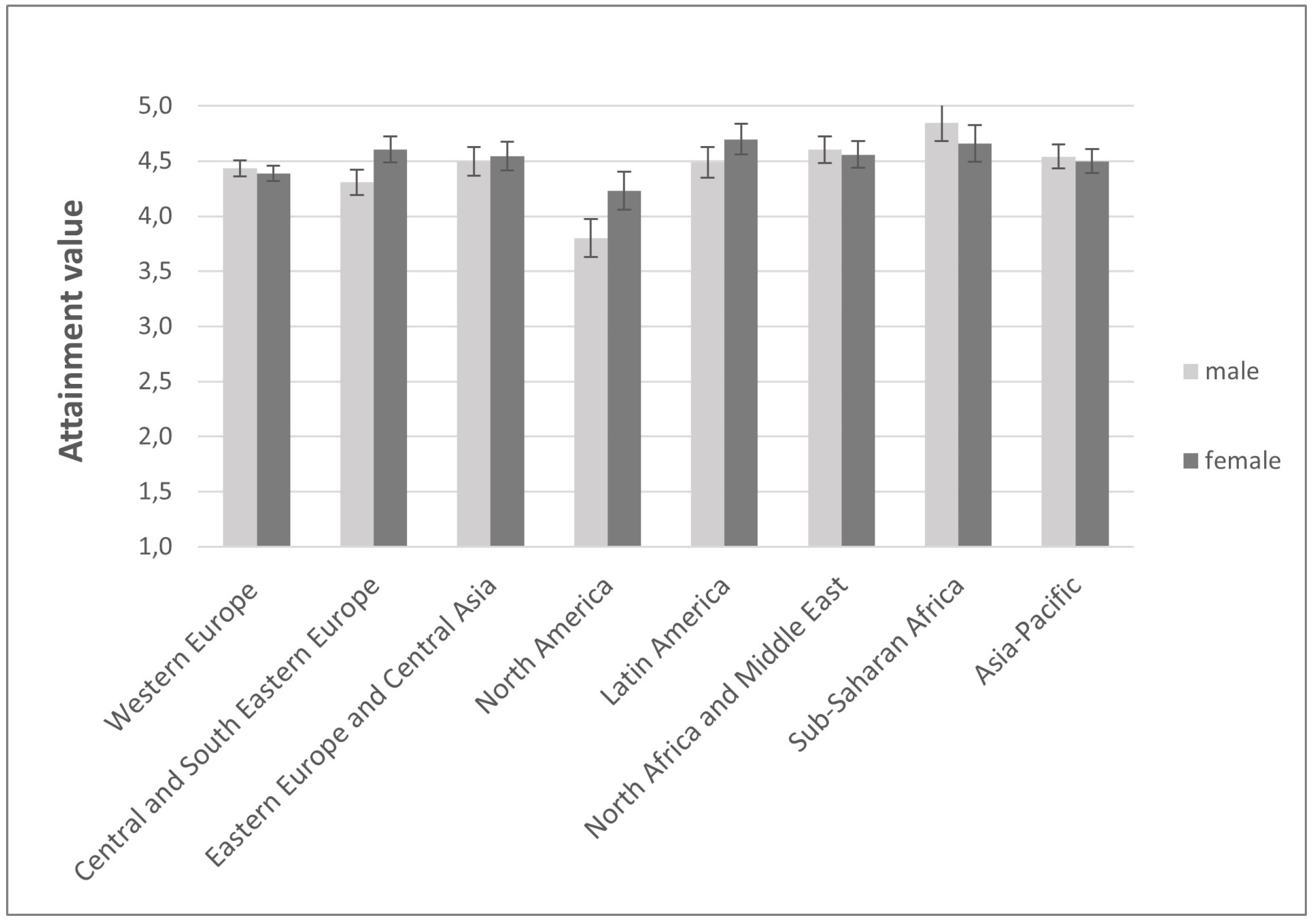

4.1. Descriptive Analyses

4.2. Multi-Group Analyses

5. Discussion

5.1. High Levels of Expectations and Value Beliefs Amongst International STEM Students

5.2. Differences in Expectations and Value Beliefs by Gender and Parental Academic Background

5.3. Differences in Expectations and Value Beliefs by Cultural Characteristics

5.4. Implications for Practice

5.5. General Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Federal Statistical Office—Destatis (Statistisches Bundesamt Destatis). Bildung und Kultur: Studierende an Hochschulen. Sommersemester 2020; Fachserie 11—Bildung und Kultur 4.1; Statistisches Bundesamt: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/DEHeft_derivate_00061732/2110410207314_fuer_Bibliothek.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- OECD. International Student Mobility (Indicator); OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. International Migration Outlook 2022; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DAAD; DZHW. Wissenschaft Weltoffen 2021; wbv Media GmbH & Co. KG: Bielefeld, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, P.; Grote, D. Anwerbung und Bindung von internationalen Studierenden in Deutschland: Studie der Deutschen Nationalen Kontaktstelle für das Europäische Migrationsnetzwerk (EMN); Working Paper; Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF) Forschungszentrum Migration, Integration und Asyl (FZ): Nürnberg, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-67593-8 (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Heublein, U.; Hutzsch, C.; Schmelzer, R. Die Entwicklung der Studienabbruchquoten in Deutschland; DSHW Brief; DZHW: Hannover, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Adler, T.F.; Fattermann, R.; Goff, S.B.; Kaczala, C.M.; Meece, J.L.; Midgley, C. Expectancies, values and academics behaviors. In Achievement and Achievement Motivation; Spence, J.T., Ed.; Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1983; pp. 75–146. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J.S.; Wigfield, A. From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, P.D.; van Zanden, B.; Marsh, H.W.; Owen, K.; Duineveld, J.J.; Noetel, M. The intersection of gender, social class, and cultural context: A meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 32, 197–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, E.R. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, G.-A. Verhältnisbestimmungen: Geschlecht, Klasse, Ethnizität in gesellschaftstheoretischer Perspektive. In Im Widerstreit: Feministische Theorie in Bewegung; Knapp, G.-A., Ed.; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 429–460. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J.S. Understanding women’s educational and occupational choices: Applying the Eccles et al. model of achievement-related choices. Psychol. Women Quart. 1994, 18, 585–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickhäuser, O.; Seidler, A.; Kölzer, M. Kein Mensch kann alles? Effekte dimensionaler Vergleiche auf das Fähigkeitsselbstkonzept. Z. Padagog. Psychol. 2005, 19, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W. Do university teachers become more effective with experience? A multilevel growth model of students’ evaluations of teaching over 13 years. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W.H. Freeman & Co., Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pajares, F. Self-efficacy beliefs in academic settings. Rev. Educ. Res. 1996, 66, 543–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Wigfield, A. Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2002, 53, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Pastorelli, C.; Barbaranelli, C.; Caprara, G.V. Self-efficacy pathways to childhood depression. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Vida, M.N.; Barber, B. The relation of early adolescents’ college plans and both academic ability and task-value beliefs to subsequent college enrollment. J. Early Adolesc. 2004, 24, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. 35 years of research on students’ subjective task values and motivation: A look back and a look forward. Adv. Motiv. Sci. 2020, 7, 161–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautwein, U.; Marsh, H.W.; Nagengast, B.; Lüdtke, O.; Nagy, G.; Jonkmann, K. Probing for the multiplicative term in modern expectancy–value theory: A latent interaction modeling study. Jpn. J. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 104, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wille, E.; Stoll, G.; Gfrörer, T.; Cambria, J.; Nagengast, B.; Trautwein, U. It takes two: Expectancy-value constructs and vocational interests jointly predict STEM major choices. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Wang, M.-T. What motivates females and males to pursue careers in mathematics and science? Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2016, 40, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, E.; Keller, L. Geschlechtsunterschiede in der Frühen MINT-Bildung—Forschungsüberblick; Stiftung-Kinder-Forschen: Berlin, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://www.haus-der-kleinen-forscher.de/ (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Jiang, S.; Simpkins, S.D.; Eccles, J.S. Individuals’ math and science motivation and their subsequent STEM choices and achievement in high school and college: A longitudinal study of gender and college generation status differences. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 2137–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Gender differences in academic self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2013, 28, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajares, F.; Miller, M.D.; Johnson, M.J. Gender differences in writing self-beliefs of elementary school students. J. Educ. Psychol. 1999, 91, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Freer, E.; Robinson, K.A.; Perez, T.; Lira, A.K.; Briedis, D.; Walton, S.P.; Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. The multiplicative function of expectancy and value in predicting engineering students’ choice, persistence, and performance. J. Eng. Educ. 2022, 111, 531–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Statistical Office—Destatis (Statistisches Bundesamt Destatis). Bildung und Kultur: Studierende an Hochschulen. Wintersemester 2017/18; Fachserie 11—Bildung und Kultur No. 4.1; Statistisches Bundesamt: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://www.statistischebibliothek.de/mir/receive/DEHeft_mods_00092410 (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Federal Employment Agency (Bundesagentur für Arbeit). Berichte: Blickpunkt Arbeitsmarkt—MINT—Berufe; Bundesagentur für Arbeit Statistik/Arbeitsmarktberichterstattung: Nürnberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Padgett, R.D.; Johnson, M.P.; Pascarella, E.T. First-generation undergraduate students and the impacts of the first year of college: Additional evidence. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2012, 53, 243–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascarella, E.T.; Pierson, C.T.; Wolniak, G.C.; Terenzini, P.T. First-generation college students: Additional evidence on college experiences and outcomes. J. High. Educ. 2004, 75, 249–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, J.; Heublein, U. Studienabbruch bei Studierenden mit Migrationshintergrund: Eine Vergleichende Untersuchung der Ursachen und Motive des Studienabbruchs bei Studierenden mit und ohne Migrationshintergrund auf Basis der Befragung der Exmatrikulierten des Sommersemesters 2014; DZHW: Hannover, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Janke, S.; Rudert, S.C.; Marksteiner, T.; Dickhäuser, O. Knowing one’s place: Parental educational background influences social identification with academia, test anxiety, and satisfaction with studying at university. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lörz, M. Intersektionalität im Hochschulbereich: In welchen Bildungsphasen bestehen soziale Ungleichheiten nach Migrationshintergrund, Geschlecht und sozialer Herkunft—und inwieweit zeigen sich Interaktionseffekte? Z. Erzieh. 2019, 22, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspard, H.; Lauermann, F.; Rose, N.; Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. Cross-domain trajectories of students’ ability self-concepts and intrinsic values in math and language arts. Child Dev. 2020, 91, 1800–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.; Fleckenstein, J.; Köller, O. Expectancy value interactions and academic achievement: Differential relationships with achievement measures. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 58, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, J.; Heddy, B.C.; Cavazos, J. First-generation college students’ academic challenges understood through the lens of expectancy value theory in an introductory psychology course. Teach. Psychol. 2022, 49, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonks, S.M.; Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. Expectancy-value theory in cross-cultural perspective: What have we learned in the last 15 years? In Big Theories Revisited 2; Liem, G.A.D., McInerney, D.M., Eds.; IAP—Information Age Publishing, Inc.: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2018; pp. 96–116. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. The development of competence, belief, expectancies for success, and achievement values from childhood through adolescence. In Development of Achievement Motivation: Educational Psychology; Wigfield, A., Eccles, J.S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Else-Quest, N.M.; Hyde, J.S.; Linn, M.C. Cross-national patterns of gender differences in mathematics: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A.D.; Penner, A.M. Exploring international gender differences in mathematics self-concept. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2016, 21, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, D. Culture, cognition, and college: How do cultural values and theories of intelligence predict students’ intrinsic value for learning? JCVE 2020, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, S.Y.; Bakaç, C.; Froehlich, L. ‘My family’s goals are also my goals’: The relationship between collectivism, distal utility value, and learning and career goals of international university students in Germany. Int. J. Educ. Vocat. Guid. 2021, 21, 355–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, K.; Lenhard, W.; Möhring, J.; Spiegel, L. (Eds.) Sprache und Studienerfolg bei Bildungsausländerinnen und Bildungsausländern; Waxmann: Münster, Germany; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Glorius, B. Gekommen, um zu bleiben? Der Verbleib internationaler Studierender in Deutschland aus einer Lebenslaufperspektive. Raumforsch. Raumordn. 2016, 74, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, J.; Greischel, H.; Jonkmann, K. The development of multicultural effectiveness in international student mobility. High. Educ. 2021, 82, 1071–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W. Acculturation: A conceptual overview. In Monographs in Parenting Series: Acculturation and Parent-Child Relationships: Measurement and Development, 1st ed.; Bornstein, M.H., Cote, L.R., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J.W. Lead Article—Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 46, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierwiaczonek, K.; Kunst, J.R. Revisiting the integration hypothesis: Correlational and longitudinal meta-analyses demonstrate the limited role of acculturation for cross-cultural adaptation. Psychol. Sci. 2021, 32, 1476–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crenshaw, K. On Intersectionality: Essential Writings; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://permalink.obvsg.at/AC15054604 (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Ferree, M.M. Filling the glass: Gender perspectives on families. J. Marriage Fam. 2010, 72, 420–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhee, D.; Farro, S.; Canetto, S.S. Academic self-efficacy and performance of underrepresented STEM majors: Gender, ethnic, and social class patterns. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy 2013, 13, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegle-Crumb, C.; Moore, C.; Ramos-Wada, A. Who wants to have a career in science or math? Exploring adolescents’ future aspirations by gender and race/ethnicity. Sci. Ed. 2010, 95, 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaney, J.M.; Stout, J.G. Examining the relationship between introductory computing course experiences, self-efficacy, and belonging among first-generation college women. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGCSE Technical Symposium on Computer Science Education; Caspersen, M.E., Edwards, S.H., Barnes, T., Garcia, D.D., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest, N.M.; Mineo, C.C.; Higgins, A. Math and science attitudes and achievement at the intersection of gender and ethnicity. Psychol. Women Quart. 2013, 37, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.; Shen, Y.; Alfaro, E.C. Adolescents’ beliefs about math ability and their relations to STEM career attainment: Joint consideration of race/ethnicity and gender. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falk, S.; Thies, T.; Yildirim, H.H.; Zimmermann, J.; Kercher, J.; Pineda, J. Methodenbericht zum “International Student Survey” aus dem Projekt “Studienerfolg und Studienabbruch bei Bildungsausländern in Deutschland im Bachelor- und Masterstudium” (SeSaBa): Release 2.0; SSOAR, GESIS-Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften e.V.; Bayerisches Staatsinstitut für Hochschulforschung und Hochschulplanung (IHF): Mannheim, München, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Beierlein, C.; Kovaleva, A.; Kemper, C.J.; Rammstedt, B. ASKU—Allgemeine Selbstwirksamkeit Kurzskala; ZPID (Leibniz Institute for Psychology Information)-Testarchiv: Trier, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanz, M. Forschungsmethoden und Statistik für die Soziale Arbeit: Grundlagen und Anwendungen, 2nd ed.; Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Westermann, R.; Heise, E.; Spies, K.; Trautwein, U. Identifikation und Erfassung von Komponenten der Studienzufriedenheit. Psychol. Erzieh. Und Unterr. 1996, 43, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Heise, E.; Thies, B. Die Bedeutung von Diversität und Diversitätsmanagement für die Studienzufriedenheit. Z. Padagog. Psychol. 2015, 29, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspard, H.; Dicke, A.-L.; Flunger, B.; Brisson, B.M.; Häfner, I.; Nagengast, B.; Trautwein, U. Fostering adolescents’ value beliefs for mathematics with a relevance intervention in the classroom. Dev. Psychol. 2015, 51, 1226–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DAAD; DZHW. Wissenschaft Weltoffen 2022: Daten und Fakten zur Internationalität von Studium und Forschung in Deutschland; wbv Media: Bielefeld, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Demes, K.A.; Geeraert, N. Measures matter. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 28.0); Released; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus Users Guide, 7th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1998–2015. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. Available online: http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0731/88012110-d.html (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- DAAD; DZHW. Wissenschaft Weltoffen 2019: Daten und Fakten zur Internationalität von Studium und Forschung in Deutschland. Fokus: Studienland Deutschland—Motive und Erfahrungen internationaler Studierender; DAAD; DZHW: Bielefeld, Germany, 2019; Available online: https://www.wissenschaft-weltoffen.de/content/uploads/2021/09/wiwe_2019_verlinkt.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Lee, H.R.; von Keyserlingk, L.; Arum, R.; Eccles, J.S. Why do they enroll in this course? Undergraduates’ course choice from a motivational perspective. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 641254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, BMBF). Deutschland ist international Spitzenreiter in MINT; BMBF: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stifterverband; McKinsey & Company. Vom Arbeiterkind zum Doktor: Der Hürdenlauf auf dem Bildungsweg der Erststudierenden; Stifterverband für die Deutsche Wissenschaft e.V.: Essen, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schnettler, T.; Scheunemann, A.; Bäulke, L.; Thies, D.O.; Kegel, L.S.; Bobe, J.; Dresel, M.; Fries, S.; Leutner, D.; Wirth, J.; et al. Studienmotivation und Studienerfolg: Zusammenhänge zwischen Erwartung, Wert und motivationalen Kosten mit Studienleistungen und Studienabbruchintentionen [Paper presentation]. In Proceedings of the 10th Annual Conference Gesellschaft für Empirische Bildungsforschung GEBF, Duisburg-Essen, Germany, 2 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, L.; Tsukamoto, S.; Morinaga, Y.; Sakata, K.; Uchida, Y.; Keller, M.M.; Stürmer, S.; Martiny, S.E.; Trommsdorff, G. Gender stereotypes and expected backlash for female STEM students in Germany and Japan. Front. Educ. 2022, 6, 793486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poort, I.; Jansen, E.; Hofman, A. Promoting university students’ engagement in intercultural group work: The importance of expectancy, value, and cost. Res. High. Educ. 2023, 64, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspard, H.; Dicke, A.-L.; Flunger, B.; Schreier, B.; Häfner, I.; Trautwein, U.; Nagengast, B. More value through greater differentiation: Gender differences in value beliefs about math. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 107, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethel, A.; Ward, C.; Fetvadjiev, V.H. Cross-cultural transition and psychological adaptation of international students: The mediating role of host national connectedness. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 539950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suanet, I.; van de Vijver, F.J.R. Perceived cultural distance and acculturation among exchange students in Russia. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 19, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.; Simpkins, S.D.; Eccles, J.S. Gender by racial/ethnic intersectionality in the patterns of adolescents’ math motivation and their math achievement and engagement. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 66, 101974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Else-Quest, N.M.; Grabe, S. The political is personal. Psychol. Women Quart. 2012, 36, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrett, N.; Malanchuk, O.; Davis-Kean, P.E.; Eccles, J.S. Examining the gender gap in IT by race: Young adults’ decisions to pursue an IT career. In Women and Information Technology; Cohoon, J., Aspray, W., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 55–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski, K.; Möhring, J.; Lenhard, W.; Seeger, J. Zum Zusammenhang sprachlicher Kompetenzen mit dem Studienerfolg von Bildungsausländer/-innen im ersten Studiensemester. In Testen Bildungssprachlicher Kompetenzen und Akademischer Sprachkompetenzen: Zugaenge Für Schule und Hochschule; Drackert, A., Mainzer-Murrenhoff, M., Soltyska, A., Timukova, A., Eds.; Peter Lang GmbH, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften: Berlin, Germany, 2020; pp. 279–319. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig, E.Q.; Wigfield, A.; Hulleman, C.S. More useful or not so bad? Examining the effects of utility value and cost reduction interventions in college physics. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 112, 166–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, E.Q.; Song, Y.; Clark, S. Mixed effects of a randomized trial replication study testing a cost-focused motivational intervention. Learn. Instr. 2022, 82, 101660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middendorff, E. Studienbelastung im Bachelor-Studium—alles nur gefühlt? Befunde der 19. Sozialerhebung des DSW durchgeführt vom HIS-Institut für Hochschulforschung. In Rückenwind—Was Studis gegen Stress tun können: Ein Ratgeber mit informativen Texten und hilfreichen Tipps zum Umgang mit Stress für Studierende und Hochschulen; [Beiträge, die in den vergangenen drei Jahren bei den Karlsruher Stresstagen entstanden sind]; Duriska, M., Ed.; KIT Karlsruher Institut für Technologie: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2011; pp. 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Schunk, D.H.; Pajares, F. The development of academic self-efficacy. In Development of Achievement Motivation: Educational Psychology; Wigfield, A., Eccles, J.S., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Sánchez, J.; Zimmermann, J.; Jonkmann, K. When in Rome… A longitudinal investigation of the predictors and the development of student sojourners’ host cultural behavioral engagement. Int. J. Intercult. Rel. 2021, 83, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtrop, D.; Hughes, A.W.; Dunlop, P.D.; Chan, J.; Steedman, G. Do social desirability scales measure dishonesty? Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2021, 37, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mummendey, H.D. Methoden und Probleme der Kontrolle sozialer Erwünschtheit (Social Desirability). Z. Differ. Diagn. Psychol. 1981, 2, 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Harackiewicz, J.M.; Canning, E.A.; Tibbetts, Y.; Priniski, S.J.; Hyde, J.S. Closing achievement gaps with a utility-value intervention: Disentangling race and social class. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 111, 745–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | STEM | Non-STEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (SD) | 22.95 | (3.58) | 24.18 | (4.87) |

| Female (%) | 283 | (32.1%) | 485 | (68.5%) |

| Parental academic background (continuous-generation students) (%) | 542 | (67.2%) | 445 | (67.4%) |

| Country groups (%) | ||||

| Western Europe (Reference category) | 95 | (10.8%) | 148 | (20.9%) |

| Central and South Eastern Europe | 117 | (13.3%) | 116 | (16.4%) |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 74 | (8.4%) | 133 | (18.8%) |

| North America | 21 | (2.4%) | 43 | (6.1%) |

| Latin America | 67 | (7.6%) | 53 | (7.5%) |

| North Africa and Middle East | 269 | (30.5%) | 62 | (8.8%) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 45 | (5.1%) | 33 | (4.7%) |

| Asia and Pacific | 194 | (22.0%) | 120 | (16.9%) |

| Previous residence in Germany (yes) (%) | 253 | (29.1%) | 300 | (43.0%) |

| Variables | STEM | Non-STEM | t-Tests | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t(df) | p | d | |

| Study-related language skills | 3.98 | 0.92 | 4.03 | 0.96 | 0.96(1561) | .335 | .05 |

| Home-culture orientation | 2.92 | 0.90 | 3.00 | 0.90 | 1.64(1518) | .102 | .08 |

| Host-culture orientation | 3.51 | 0.84 | 3.54 | 0.78 | 0.68(1519) | .498 | .04 |

| Dependent variables | |||||||

| Academic self-efficacy | 3.71 | 0.71 | 3.81 | 0.69 | 2.72(1553) | .007 | .14 |

| Value beliefs | |||||||

| Attainment value | 4.49 | 0.68 | 4.48 | 0.60 | −0.33(1559) | .745 | −.02 |

| Intrinsic value | 3.99 | 0.82 | 4.06 | 0.80 | 1.78(1559) | .075 | .09 |

| Utility value | 4.53 | 0.67 | 4.51 | 0.61 | −0.53(1559) | .598 | −.03 |

| Cost value | 3.45 | 0.89 | 3.39 | 0.91 | −1.30(1559) | .193 | −.07 |

| Correlations | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. | 12. | 13. | 14. | 15. | 16. | 17. | 18. | 19. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Academic self-efficacy | - | .15 ** | .30 ** | .20 ** | −.10 ** | .39 ** | .00 | .01 | .07 | .03 | .05 | .15 ** | −.02 | −.06 | −.04 | −.17 ** | .01 | .02 | .04 |

| Value beliefs | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Attainment value | .21 ** | - | .36 ** | .49 ** | .10 ** | .11 ** | .07 | −.01 | −.09 * | .04 | .00 | −.17 ** | .08 * | .05 | .11 ** | −.02 | .04 | −.02 | .19 ** |

| 3. Intrinsic value | .34 ** | .40 ** | - | .30 ** | −.22 ** | .31 ** | −.01 | .06 | −.05 | −.01 | .01 | −.01 | .03 | .04 | .04 | −.17 ** | .01 | −.07 | .10 * |

| 4. Utility value | .21 ** | .62 ** | .38 ** | - | .08 * | .16 ** | .07 | .01 | −.00 | .09 * | .10 ** | −.13 ** | .12 ** | .07 | .02 | −.15 ** | .10 * | −.04 | .18 ** |

| 5. Cost value | −.07 * | .21 ** | −.11 ** | .17 ** | - | −.22 ** | −.01 | .14 ** | −.02 | .03 | −.00 | .12 ** | .03 | .08 * | .02 | .06 | .03 | .07 | .13 ** |

| 6. Study-related language skills | .27 ** | .11 ** | .27 ** | .13 ** | −.15 ** | - | −.05 | −.11 ** | .01 | .08 * | .02 | −.00 | −.03 | −.11 ** | .06 | −.41 ** | .04 | .01 | −.02 |

| 7. Previous residence Germany | .00 | −.06 | −.05 | −.03 | .02 | −.04 | - | .12 ** | −.01 | .02 | .21 ** | −.07 | .16 ** | −.14 ** | −.03 | −.06 | .12 ** | −.13 ** | .02 |

| 8. Age | −.04 | .01 | .01 | −.05 | .06 | −.07 | .08 * | - | −.12 ** | −.15 ** | .08 * | .15 ** | .06 | .14 ** | .09 * | .02 | −.03 | −.07 | .03 |

| 9. Parental academic background | .07 * | .02 | .07 | −.00 | .03 | .02 | .08 * | −.24 ** | - | −.05 | .12 ** | .14 ** | .11 ** | −.05 | .01 | −.06 | −.08 | .04 | .02 |

| Country groups | |||||||||||||||||||

| 10. Central and South Eastern Europe | .05 | −.06 | .04 | .04 | .00 | .09 ** | .08 * | −.22 ** | .01 | - | −.21 ** | −.11 ** | −.13 ** | −.14 ** | −.01 ** | −.20 ** | .05 | −.06 | −.01 |

| 11. Eastern Europe and Central Asia | .04 | .00 | .04 | .09 * | −.04 | .07 * | .22 ** | .03 | .11 ** | −.12 ** | - | −.12 ** | −.14 ** | −.15 ** | −.11 ** | −.22 ** | .16 ** | −.08 * | .02 |

| 12. North America | .04 | −.09 * | −.04 | −.11 * | .04 | .02 | .02 | .13 ** | .06 | −.06 | −.05 | - | −.07 | −.08 * | −.06 | −.12 ** | −.02 | .13 ** | .08 * |

| 13. Latin America | .07 | .03 | .05 | .07 * | .10 ** | .04 | .13 ** | .01 | .11 ** | −.11 ** | −.09 ** | −.05 | - | −.09 * | −.06 | −.13 ** | −.03 | −.02 | .12 * |

| 14. North Africa and Middle East | −.04 | .12 ** | −.10 ** | .03 | .07 | −.10 ** | −.15 ** | .21 ** | −.07 * | −.26 ** | −.20 ** | −.10 ** | −.19 ** | - | −.07 | −.14 ** | −.25 ** | −.07 | −.03 |

| 15. Sub-Sahara Africa | −.03 | .13 ** | .08 * | .12 ** | .00 | .04 | −.12 ** | .07 | −.08 * | −.09 ** | −.07 * | −.04 | −.07 * | −.15 ** | - | −.10 ** | −.02 | −.03 | −.00 |

| 16. Asia and Pacific | −.07 | −.09 * | −.09 ** | −.18 ** | −.05 | −.26 ** | −.02 | −.01 | −.01 | −.21 ** | −.16 ** | −.08 * | −.15 ** | −.35 ** | −.12 ** | - | −.00 | .06 | .03 |

| 17. Gender | −.04 | −.03 | −.00 | .07 * | .00 | .02 | .07 * | −.03 | .07 * | .08 * | .17 ** | .00 | .05 | −.21 ** | −.02 | .04 | - | −.01 | −.01 |

| 18. Home-culture orientation | −.05 | −.04 | −.06 | −.05 | −.00 | −.03 | −.11 ** | −.20 ** | .07 | −.04 | −.11 ** | .04 | −.03 | −.06 | −.00 | .12 ** | −.02 | - | .16 ** |

| 19. Host-culture orientation | .03 | .12 ** | .14 ** | .09 * | .01 | −.02 | .01 | .05 | −.03 | −.10 ** | .03 | .06 | .05 | .03 | −.04 | .04 | .03 | .08 * | - |

| Predictors | Academic Self-Efficacy | Attainment Value | Intrinsic Value | Utility Values | Cost Value | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Final Model | b | SE | p | b | SE | p | b | SE | p | b | SE | p | b | SE | p |

| Age | .00 | .00 | .468 | −.00 | .00 | .830 | .01 | .01 | .013 | −.00 | .00 | .566 | .01 | .01 | .017 |

| Previous residence in Germany | −.02 | .04 | .634 | .02 | .04 | .501 | −.05 | .05 | .271 | −.03 | .04 | .480 | −.00 | .05 | .971 |

| Study-related language skills | .27 | .02 | < .001 | .09 | .02 | < .001 | .23 | .02 | < .001 | .08 | .02 | < .001 | −.17 | .03 | < .001 |

| Country groupsa | |||||||||||||||

| Central and South Eastern Europe | .14 | .06 | .027 | −.13 | .09 | .160 | −.11 | .07 | .147 | .08 | .09 | .348 | .35 | .08 | < .001 |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | .10 | .07 | .122 | .06 | .11 | .557 | −.10 | .08 | .222 | .17 | .11 | .110 | .24 | .09 | .007 |

| North America | .30 | .10 | .002 | −.63 | .13 | < .001 | −.25 | .11 | .027 | −.61 | .13 | < .001 | .56 | .13 | < .001 |

| Latin America | .12 | .08 | .137 | .05 | .10 | .606 | −.05 | .09 | .561 | .15 | .10 | .143 | .50 | .10 | < .001 |

| North Africa and Middle East | .06 | .06 | .335 | .17 | .08 | .024 | −.21 | .07 | .004 | .11 | .07 | .135 | .39 | .08 | < .001 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | −.03 | .09 | .759 | .41 | .12 | < .001 | .05 | .11 | .666 | .21 | .12 | .063 | .33 | .12 | .006 |

| Asia and Pacific | .12 | .06 | .073 | .11 | .08 | .194 | −.15 | .07 | .047 | −.09 | .08 | .292 | .17 | .09 | .045 |

| Gender | −.05 | .04 | .160 | −.04 | .09 | .625 | −.01 | .04 | .829 | −.06 | .09 | .529 | .05 | .05 | .303 |

| Parental academic background | .08 | .04 | .027 | −.04 | .05 | .459 | .06 | .04 | .180 | −.04 | .05 | .434 | .00 | .05 | .998 |

| Home-culture orientation | −.02 | .02 | .439 | −.02 | .02 | .393 | −.07 | .02 | .002 | −.02 | .02 | .333 | .05 | .03 | .055 |

| Host-culture orientation | .03 | .02 | .151 | .12 | .02 | < .001 | .14 | .03 | < .001 | .10 | .02 | < .001 | .04 | .03 | .169 |

| Gender × parental academic background | −.01 | .07 | .873 | .03 | .07 | .618 | |||||||||

| Central and South Eastern Europe × gender | .34 | .12 | .003 | .19 | .12 | .096 | |||||||||

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia × gender | .09 | .13 | .475 | .11 | .13 | .400 | |||||||||

| North America × gender | .47 | .17 | .006 | .60 | .17 | < .001 | |||||||||

| Latin America × gender | .26 | .14 | .066 | .25 | .14 | .072 | |||||||||

| North Africa and Middle East × gender | −.00 | .12 | .987 | .11 | .12 | .347 | |||||||||

| Sub-Saharan Africa × gender | −.14 | .17 | .397 | .05 | .17 | .746 | |||||||||

| Asia-Pacific × gender | .00 | .11 | .999 | .12 | .11 | .263 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Preuß, J.S.; Zimmermann, J.; Jonkmann, K. Academic Self-Efficacy and Value Beliefs of International STEM and Non-STEM University Students in Germany from an Intersectional Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13080786

Preuß JS, Zimmermann J, Jonkmann K. Academic Self-Efficacy and Value Beliefs of International STEM and Non-STEM University Students in Germany from an Intersectional Perspective. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(8):786. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13080786

Chicago/Turabian StylePreuß, Judith Sarah, Julia Zimmermann, and Kathrin Jonkmann. 2023. "Academic Self-Efficacy and Value Beliefs of International STEM and Non-STEM University Students in Germany from an Intersectional Perspective" Education Sciences 13, no. 8: 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13080786

APA StylePreuß, J. S., Zimmermann, J., & Jonkmann, K. (2023). Academic Self-Efficacy and Value Beliefs of International STEM and Non-STEM University Students in Germany from an Intersectional Perspective. Education Sciences, 13(8), 786. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13080786