“Who’s Better at Math, Boys or Girls?”: Changes in Adolescents’ Math Gender Stereotypes and Their Motivational Beliefs from Early to Late Adolescence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Understanding Math Ability Stereotypes through Situated Expectancy-Value Theory and Social Status Theory

1.2. Empirical Evidence on the Prevalence and Differences in Adolescents’ Math Ability Gender Stereotypes

1.3. Adolescents’ Math Gender Stereotypes and Motivational Beliefs

1.4. Current Study

1.4.1. Hypothesis 1: Changes in the Prevalence of Math Gender Stereotypes over Time

1.4.2. Hypothesis 2: Group Differences in the Prevalence of Math Gender Stereotypes

1.4.3. Hypothesis 3: Adolescents’ Math Gender Stereotypes in Relation to Their Math Motivational Beliefs

2. Method

2.1. Datasets

2.1.1. Maryland Adolescent Development in Context Study (MADICS): Eighth and Eleventh Grades

2.1.2. High School Longitudinal Study (HSLS): Ninth and Eleventh Grades

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Adolescents’ Math Ability Gender Stereotypes

2.2.2. Adolescents’ Math Expectancy and Value Beliefs

2.2.3. Background and Covariates

2.3. Plan of Analysis

2.3.1. Hypothesis 1: Changes in the Prevalence of Math Gender Stereotypes over Time

2.3.2. Hypothesis 2: Group Differences in the Prevalence of Adolescents’ Math Gender Stereotypes

2.3.3. Hypothesis 3: Adolescents’ Math Gender Stereotypes in Relation to Their Math Motivational Beliefs

3. Results

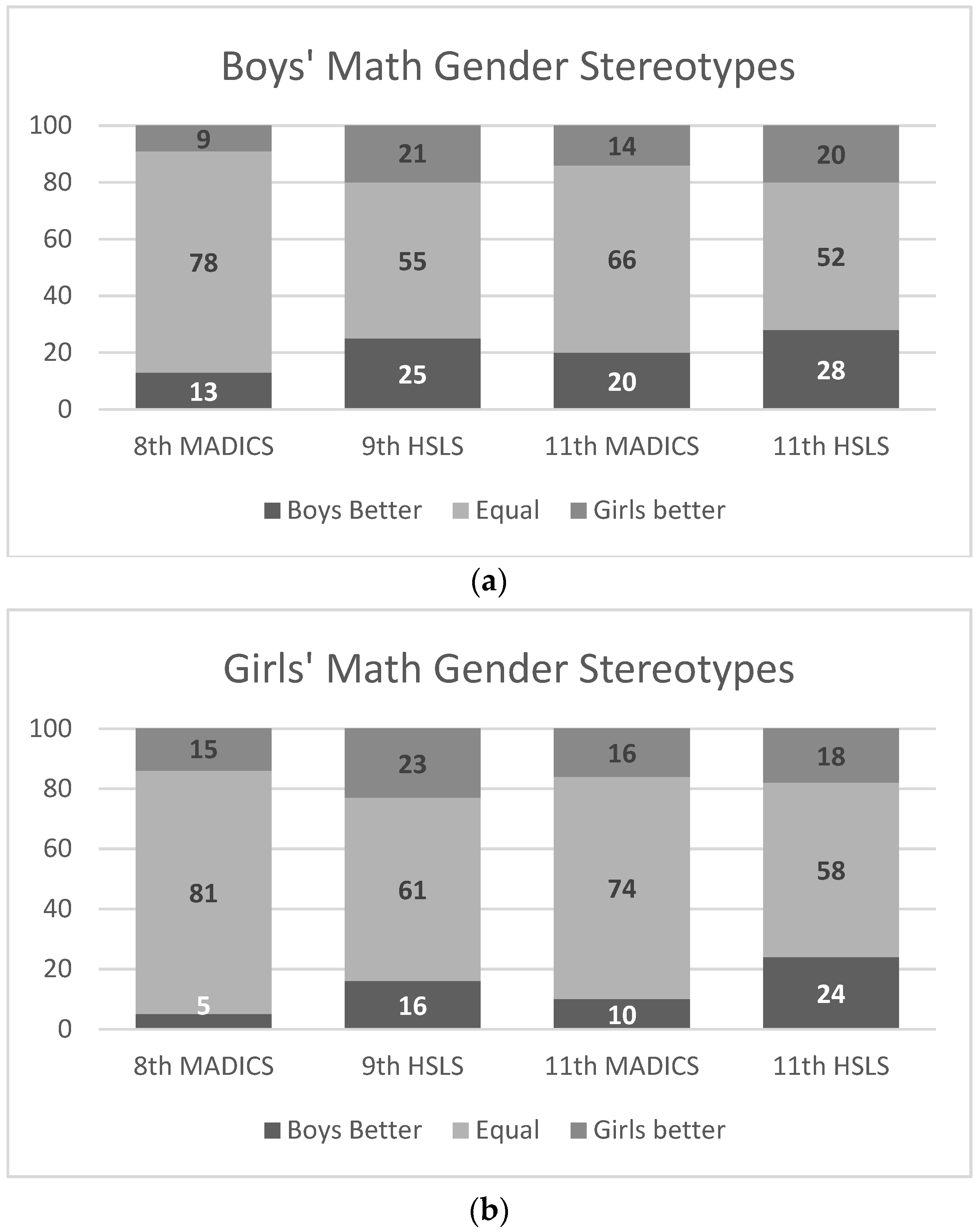

3.1. Hypothesis 1: Prevalence of Math Gender Stereotypes

3.1.1. Changes from Early to Late Adolescence

3.1.2. Prevalence in Early Adolescence

3.1.3. Prevalence in Late Adolescence

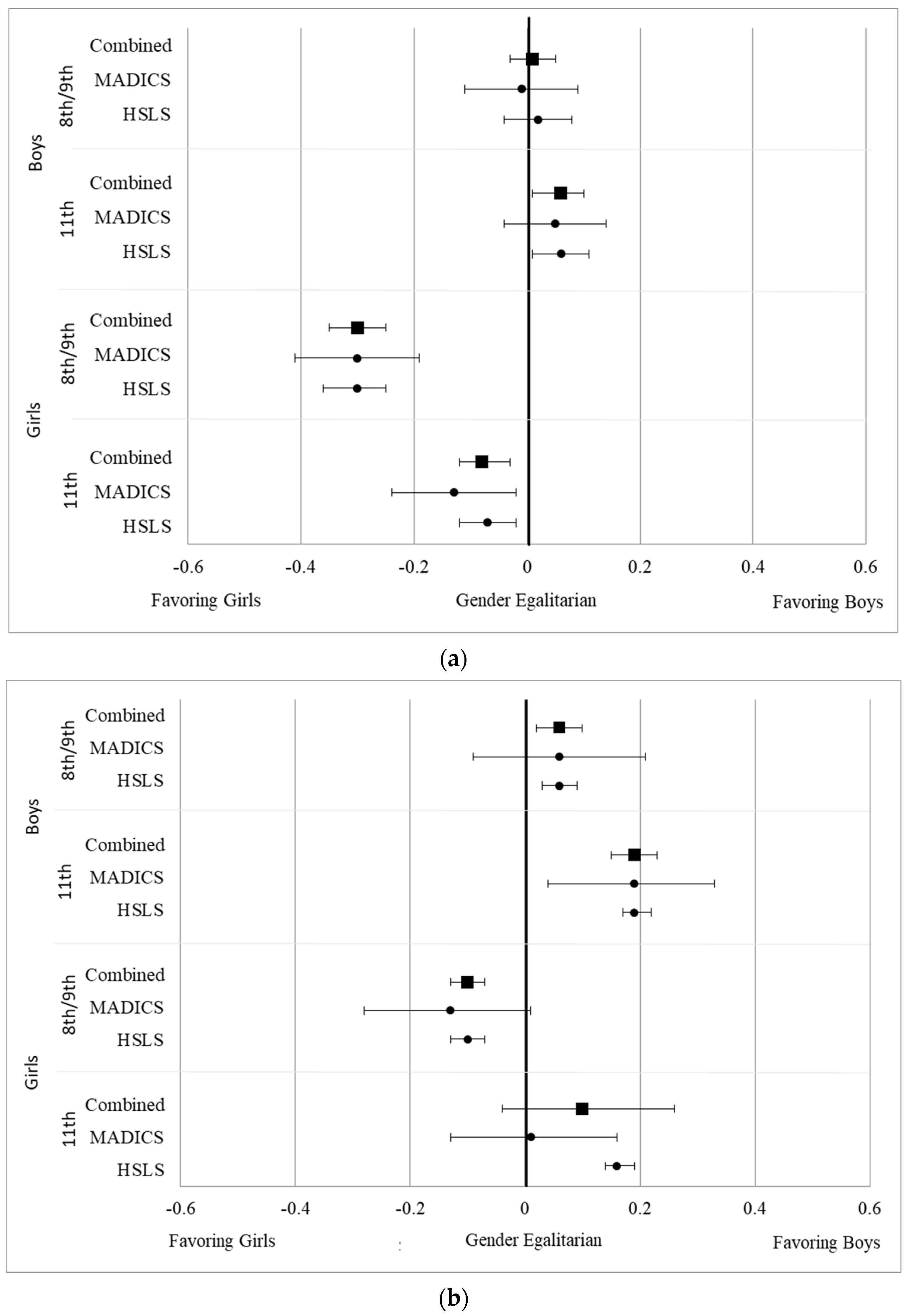

3.2. Hypothesis 2: Group Differences in Prevalence

3.2.1. Stereotype Prevalence by Gender

3.2.2. Stereotype Prevalence by Race/Ethnicity

3.3. Hypothesis 3: Adolescents’ Math Gender Stereotypes and Motivational Beliefs

4. Discussion

4.1. The Prevalence and Changes in Gender Stereotypes

Racial/Ethnic and Gender Comparisons

4.2. Adolescents’ Math Gender Stereotypes and Their Expectancy and Value Beliefs

4.3. Practical Implications

4.4. Future Directions and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Breda, T.; Jouini, E.; Napp, C.; Thebault, G. Gender Stereotypes Can Explain the Gender-Equality Paradox. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 31063–31069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubach, C.; Lee, G.; Starr, C.R.; Gao, Y.; Safavian, N.; Dicke, A.-L.; Eccles, J.S.; Simpkins, S.D. Is There Any Evidence of Historical Changes in Gender Differences in American High School Students’ Math Competence-Related Beliefs from the 1980s to the 2010s? Int. J. Gend. Sci. Technol. 2022, 14, 55–126. [Google Scholar]

- Rickles, J.; Heppen, J.; Taylor, S.; Sorensen, N.; Walters, K.; Clements, P. Course Progression for Students Who Fail Algebra I in Ninth Grade; American Institutes for Research: Arlington County, VA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/Course-Progression-for-Students-Who-Fail-Algebra-I-in-Ninth-Grade-June-2017.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Regner, I.; Steele, J.R.; Ambady, N.; Thinus-Blanc, C.; Huguet, P. Our Future Scientists: A Review of Stereotype Threat in Girls from Early Elementary School to Middle School. Rev. Int. De Psychol. Soc. 2014, 27, 13–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ceci, S.J.; Ginther, D.K.; Kahn, S.; Williams, W.M. Women in Academic Science: A Changing Landscape. Psychol. Sci. Public. Interest. 2014, 15, 75–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Steinke, J.; Applegate, B.; Knight Lapinski, M.; Johnson, M.J.; Ghosh, S. Portrayals of Male and Female Scientists in Television Programs Popular Among Middle School-Age Children. Sci. Commun. 2010, 32, 356–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, C.R.; Ramos Carranza, P.; Simpkins, S.D. Stability and Changes in High School Students’ STEM Career Expectations: Variability Based on STEM Support and Parent Education. J. Adolesc. 2022, 94, 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. Global Gender Gap Report. 2023. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2023/ (accessed on 16 August 2023).

- McGuire, L.; Mulvey, K.L.; Goff, E.; Irvin, M.J.; Winterbottom, M.; Fields, G.E.; Hartstone-Rose, A.; Rutland, A. STEM Gender Stereotypes from Early Childhood through Adolescence at Informal Science Centers. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 67, 101109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, C.R.; Simpkins, S.D. High School Students’ Math and Science Gender Stereotypes: Relations with Their STEM Outcomes and Socializers’ Stereotypes. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2021, 24, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.; Shen, Y.; Alfaro, E.C. Adolescents’ Beliefs about Math Ability and Their Relations to STEM Career Attainment: Joint Consideration of Race/Ethnicity and Gender. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.E.; Lau, M.Y.; Howard, G.S. Is Psychology Suffering from a Replication Crisis? What Does “Failure to Replicate” Really Mean? Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plucker, J.A.; Makel, M.C. Replication Is Important for Educational Psychology: Recent Developments and Key Issues. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 56, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Wigfield, A. From Expectancy-Value Theory to Situated Expectancy-Value Theory: A Developmental, Social Cognitive, and Sociocultural Perspective on Motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plante, I.; O’Keefe, P.A.; Aronson, J.; Fréchette-Simard, C.; Goulet, M. The Interest Gap: How Gender Stereotype Endorsement about Abilities Predicts Differences in Academic Interests. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 22, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, S.J.; Kurtz-Costes, B.; Mistry, R.; Feagans, L. Social Status as a Predictor of Race and Gender Stereotypes in Late Childhood and Early Adolescence. Soc. Social. Dev. 2007, 16, 150–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, A.R.; Peacock, N. Pleasing the Masses: Messages for Daily Life Management in African American Women’s Popular Media Sources. Am. J. Public. Health 2011, 101, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erikson, E.H. Identity: Youth and Crisis; Norton & Co.: Oxford, UK, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, M.M.; Bigler, R.S. Effects of Consistency between Self and In-Group on Children’s Views of Self, Groups, and Abilities. Soc. Social. Dev. 2018, 27, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña-Taylor, A.J.; Quintana, S.M.; Lee, R.M.; Cross, W.E., Jr.; Rivas-Drake, D.; Schwartz, S.J.; Syed, M.; Yip, T.; Seaton, E.; Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. Ethnic and Racial Identity During Adolescence and Into Young Adulthood: An Integrated Conceptualization. Child. Dev. 2014, 85, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. Who Am I and What Am I Going to Do With My Life? Personal and Collective Identities as Motivators of Action. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 44, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musto, M. Brilliant or Bad: The Gendered Social Construction of Exceptionalism in Early Adolescence. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2019, 84, 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinke, J.; Lapinski, M.K.; Crocker, N.; Zietsman-Thomas, A.; Williams, Y.; Evergreen, S.H.; Kuchibhotla, S. Assessing Media Influences on Middle School–Aged Children’s Perceptions of Women in Science Using the Draw-A-Scientist Test (DAST). Sci. Commun. 2007, 29, 35–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz-Costes, B.; Copping, K.E.; Rowley, S.J.; Kinlaw, C.R. Gender and Age Differences in Awareness and Endorsement of Gender Stereotypes about Academic Abilities. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2014, 29, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvencek, D.; Meltzoff, A.N.; Greenwald, A.G. Math–Gender Stereotypes in Elementary School Children. Child. Dev. 2011, 82, 766–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatard, A.; Guimond, S.; Selimbegovic, L. “How Good Are You in Math?” The Effect of Gender Stereotypes on Students’ Recollection of Their School Marks. J. Exp. Soc. Social. Psychol. 2007, 43, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, M.C.; Jelenec, P. Separating Implicit Gender Stereotypes Regarding Math and Language: Implicit Ability Stereotypes Are Self-Serving for Boys and Men, but Not for Girls and Women. Sex. Roles 2011, 64, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, M.; Homer, M.; Swinnerton, B. A Comparison of Performance and Attitudes in Mathematics amongst the ‘Gifted’. Are Boys Better at Mathematics or Do They Just Think They Are? Assess. Educ. Princ. Policy Pract. 2008, 15, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plante, I.; Théorêt, M.; Favreau, O.E. Student Gender Stereotypes: Contrasting the Perceived Maleness and Femaleness of Mathematics and Language. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J.; Laursen, B.; Dickson, D.; Hartl, A.C. Latino Children’s Math Confidence: The Role of Mothers’ Gender Stereotypes and Involvement Across the Transition to Middle School. J. Early Adolesc. 2018, 38, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.M.; Grower, P. Media and the Development of Gender Role Stereotypes. Annu. Rev. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 2, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieg, M.; Goetz, T.; Wolter, I.; Hall, N. Gender Stereotype Endorsement Differentially Predicts Girls’ and Boys’ Trait-State Discrepancy in Math Anxiety. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, J.S.; Fennema, E.; Lamon, S.J. Gender Differences in Mathematics Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, O.D.; Kurtz-Costes, B.; Vuletich, H.; Copping, K.; Rowley, S.J. Race Differences in Black and White Adolescents’ Academic Gender Stereotypes across Middle and Late Adolescence. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2021, 27, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.B.; Copping, K.E.; Rowley, S.J.; Kurtz-Costes, B. Academic Self-Concept in Black Adolescents: Do Race and Gender Stereotypes Matter? Self Identity 2011, 10, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez, B.C.; Halim, M.L.D.; Leaper, C. Variations in Recalled Familial Messages about Gender in Relation to Emerging Adults’ Gender, Ethnic Background, and Current Gender Attitudes. J. Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 150–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, L.T.; Blodorn, A.; Adams, G.; Garcia, D.M.; Hammer, E. Ethnic Variation in Gender-STEM Stereotypes and STEM Participation: An Intersectional Approach. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2015, 21, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starr, C.R. “I’m Not a Science Nerd!”: STEM Stereotypes, Identity, and Motivation Among Undergraduate Women. Psychol. Women Q 2018, 42, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz-Costes, B.; Rowley, S.J.; Harris-Britt, A.; Woods, T.A. Gender Stereotypes about Mathematics and Science and Self-Perceptions of Ability in Late Childhood and Early Adolescence. Merrill-Palmer Q 2008, 54, 386–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, E. “Black Genius, Asian Fail”: The Detriment of Stereotype Lift and Stereotype Threat in High-Achieving Asian and Black STEM Students. AERA Open 2018, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.; Simpkins, S.D.; Eccles, J.S. Gender by Racial/Ethnic Intersectionality in the Patterns of Adolescents’ Math Motivation and Their Math Achievement and Engagement. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 66, 101974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.E.; Losee, J.; Vitiello, C. Replication Attempt of Stereotype Susceptibility (Shih, Pittinsky, & Ambady, 1999): Identity Salience and Shifts in Quantitative Performance. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 45, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passolunghi, M.C.; Rueda Ferreira, T.I.; Tomasetto, C. Math–Gender Stereotypes and Math-Related Beliefs in Childhood and Early Adolescence. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2014, 34, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Statistics (NCES). High School Longitudinal Study of 2009 User Manuals; Institute of Education Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/hsls09/usermanuals.asp (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Eccles, J.S.; Jacobs, J.E.; Harold, R.D. Gender Role Stereotypes, Expectancy Effects, and Parents’ Socialization of Gender Differences. J. Soc. Social. Issues 1990, 46, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.G.; Matthews, R.A.; Gibbons, A.M. Developing and Investigating the Use of Single-Item Measures in Organizational Research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2016, 21, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hays, R.D.; Reise, S.; Calderón, J.L. How Much Is Lost in Using Single Items? J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1402–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, A.L.; Webster, G.D. The Single-Item Need to Belong Scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013, 55, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J.S.; Wigfield, A. In the Mind of the Actor: The Structure of Adolescents’ Achievement Task Values and Expectancy-Related Beliefs. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 21, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauermann, F.; Tsai, Y.-M.; Eccles, J.S. Math-Related Career Aspirations and Choices within Eccles et al.’s Expectancy–Value Theory of Achievement-Related Behaviors. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 53, 1540–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Simpkins, S.D.; Eccles, J.S. Individuals’ Math and Science Motivation and Their Subsequent STEM Choices and Achievement in High School and College: A Longitudinal Study of Gender and College Generation Status Differences. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 56, 2137–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diemer, M.A.; Marchand, A.D.; McKellar, S.E.; Malanchuk, O. Promotive and Corrosive Factors in African American Students’ Math Beliefs and Achievement. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1208–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C.K. Applied Missing Data Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; Chapter xv; 377p. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein, M. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.; Higgins, J.; Rothstein, H. Introduction to Meta-Analysis; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L.V.; Schauer, J.M. Statistical Analyses for Studying Replication: Meta-Analytic Perspectives. Psychol. Methods 2019, 24, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, I.; Eccles, J.S. Gender Differences in Aspirations and Attainment: A Life Course Perspective; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.E.; Schmidt, F.L. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings/Frank L. Schmidt, University of Iowa, John E. Hunter, Michigan State University, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Baguley, T. Standardized or Simple Effect Size: What Should Be Reported? Br. J. Psychol. 2009, 100, 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B. Effect Sizes, Confidence Intervals, and Confidence Intervals for Effect Sizes. Psychol. Sch. 2007, 44, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siy, J.O.; Germano, A.L.; Vianna, L.; Azpeitia, J.; Yan, S.; Montoya, A.K.; Cheryan, S. Does the Follow-Your-Passions Ideology Cause Greater Academic and Occupational Gender Disparities than Other Cultural Ideologies? J. Personal. Soc. Social. Psychol. 2023, 125, 548–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcia, J.E. The Empirical Study of Ego Identity. In Identity and development: An Interdisciplinary Approach; Bosma, H.A., Graafsma, T.L.G., Grotevant, H.D., de Levita, D.J., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 67–80, Chapter xii; 204p. [Google Scholar]

- Bigler, R.S.; Patterson, M.M. Social Stereotyping and Prejudice in Children. In The Wiley Handbook of Group Processes in Children and Adolescents; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.; Utych, S.M. You’re Not From Here!: The Consequences of Urban and Rural Identities. Polit. Behav. 2021, 45, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.S.; Bigler, R.S. Children’s Perceptions of Discrimination: A Developmental Model. Child. Dev. 2005, 76, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.; Tanenbaum, C. NSF Award Search: Award # 1920401—The Development of Gender Stereotypes About STEM Abilities: A Meta-Analysis; National Science Foundation: Washington DC, USA, 2019. Available online: https://nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=1920401 (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Master, A.; Meltzoff, A.N.; Cheryan, S. Gender Stereotypes about Interests Start Early and Cause Gender Disparities in Computer Science and Engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2100030118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | MADICS | HSLS |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Longitudinal, 1 cohort | Longitudinal, 1 cohort |

| Data included | ||

| Years when collected | 1993–1996 | 2009–2012 |

| Youth waves (Year) | W3 (1993) and W4 (1996) | W1 (2009) and W2 (2012) |

| Youth’s grades | 8th and 11th Grades | 9th and 11th Grades |

| Sample sizes | ||

| Total N: Dataset | 1482 | 23,500 |

| Total N: Current study | 1186 | 23,340 |

| Demographic information | ||

| % Girls (n) | 49% (n = 585) | 50% (n = 11,670) |

| % White (n) | 30% (n = 350) | 50% (n = 11,670) |

| % Black (n) | 60% (n = 708) | 13% (n = 3030) |

| % Latinx (n) | 1% (n = 15) | 22% (n = 5140) |

| % Asian (n) | 2% (n = 20) | 4% (n = 930) |

| % Other race/ethnicity | 8% (n = 93) | 11% (n = 2570) |

| % Parent college degree | 42% | 45% |

| Family income | $30,000 or less: 23% | $35,000 or less: 28% |

| $30–60,000: 43% | $35–75,000: 32% | |

| Over $60,000: 34% | Over $75,000: 41% |

| Dataset | Boys | Girls | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M (SD) | t | d | N | M (SD) | t | d | |

| Overall | ||||||||

| Early adolescence | ||||||||

| MADICS | 601 | 0.00 (0.71) | 0.055 | 0.00 | 585 | −0.16 (0.63) | −6.664 *** | −0.25 |

| HSLS | 11,750 | 0.05 (0.98) | 5.175 *** | 0.05 | 11,750 | −0.13 (0.87) | −17.070 *** | −0.15 |

| Combined | 0.05 | −0.19 | ||||||

| Late adolescence | ||||||||

| MADICS | 601 | 0.06 (0.81) | 2.216 * | 0.09 | 585 | −0.07 (0.77) | −2.742 * | −0.09 |

| HSLS | 11,750 | 0.15 (0.98) | 17.833 *** | 0.16 | 11,750 | 0.08 (0.87) | 10.617 *** | 0.10 |

| Combined | 0.11 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Black adolescents | ||||||||

| Early adolescence | ||||||||

| MADICS | 378 | −0.01 (0.74) | −0.409 | −0.02 | 330 | −0.21 (0.69) | −5.969 *** | −0.30 |

| HSLS | 1520 | 0.02 (1.07) | 0.754 | 0.02 | 1520 | −0.31 (1.02) | −10.412 *** | −0.30 |

| Combined | -- | -- | -- | 0.01 | -- | -- | -- | −0.30 |

| Late adolescence | ||||||||

| MADICS | 378 | 0.03 (0.88) | 0.911 | .05 | 330 | −0.10 (0.76) | −2.631 * | −0.15 |

| HSLS | 1520 | 0.06 (1.03) | 2.190 * | 0.06 | 1520 | −0.07 (1.05) | −2.562 * | −0.08 |

| Combined | -- | -- | -- | 0.06 | -- | -- | -- | −0.08 |

| White adolescents | ||||||||

| Early adolescence | ||||||||

| MADICS | 166 | 0.04 (0.68) | 0.776 | 0.06 | 184 | −0.06 (0.45) | −2.129 * | −0.16 |

| HSLS | 5840 | 0.05 (1.02) | 4.455 *** | 0.06 | 5840 | −0.08 (0.85) | −7.952 *** | −0.10 |

| Combined | -- | -- | -- | 0.06 | -- | -- | -- | −0.10 |

| Late adolescence | ||||||||

| MADICS | 166 | 0.14 (0.79) | 2.564 * | 0.19 | 184 | 0.00 (0.69) | 0.099 | 0.01 |

| HSLS | 5840 | 0.18 (1.00) | 15.104 *** | 0.19 | 5840 | 0.13 (0.84) | 11.960 *** | 0.16 |

| Combined | -- | -- | -- | 0.19 | -- | -- | -- | 0.10 |

| Asian adolescents | ||||||||

| Early adolescence | ||||||||

| HSLS | 470 | 0.17 (0.94) | 6.248 *** | 0.20 | 470 | −0.12 (0.83) | −4.656 *** | −0.15 |

| Late adolescence | ||||||||

| HSLS | 470 | 0.28 (0.91) | 10.217 *** | 0.33 | 470 | 0.09 (0.90) | 3.321 ** | 0.11 |

| Latinx adolescents | ||||||||

| Early adolescence | ||||||||

| HSLS | 2570 | 0.03 (0.98) | 2.291 * | 0.04 | 2570 | −0.19 (0.87) | −9.715 *** | −0.23 |

| Late adolescence | ||||||||

| HSLS | 2570 | 0.04 (1.41) | 2.113 * | 0.05 | 2570 | 0.02 (0.95) | 1.112 | 0.03 |

| Predictor | Expectancy Beliefs Predicted by Stereotypes | Value Beliefs Predicted by Stereotypes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | Boys | Girls | |

| B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | |

| All adolescents | ||||

| Early adolescence | ||||

| MADICS | 0.23 (0.08) ** | −0.16 (0.10) + | 0.12 (0.08) | −0.06 (0.11) |

| HSLS | 0.26 (0.02) *** | −0.17 (0.03) *** | 0.10 (0.01) *** | −0.10 (0.02) *** |

| Late adolescence | ||||

| MADICS | 0.25 (0.11) * | −0.28 (0.14) * | 0.13 (0.11) | −0.23 (0.09) * |

| HSLS | 0.27 (0.03) *** | −0.22 (0.03) *** | 0.20 (0.02) *** | −0.15 (0.02) *** |

| Black adolescents | ||||

| Early adolescence | ||||

| MADICS | 0.18 (0.14) | −0.20 (0.16) | 0.06 (0.14) | 0.07 (0.20) |

| HSLS | 0.04 (0.06) | −0.11 (0.07) | 0.05 (0.05) | −0.06 (0.06) |

| Late adolescence | ||||

| MADICS | 0.07 (0.12) | −0.21 (0.17) | 0.00 (0.13) | −0.37 (0.17) * |

| HSLS | 0.23 (0.07) *** | −0.29 (0.07) *** | 0.16 (0.06) ** | −0.01 (0.06) |

| White adolescents | ||||

| Early adolescence | ||||

| MADICS | 0.36 (0.16) * | −0.16 (0.20) | −0.12(0.13) | −0.18 (0.21) |

| HSLS | 0.22 (0.03) *** | −0.18 (0.04) *** | 0.14 (0.03) ** | −0.10 (0.03) ** |

| Late adolescence | ||||

| MADICS | 0.35 (0.14) * | −0.12 (0.20) | 0.21 (0.21) | −0.16 (0.31) |

| HSLS | 0.33 (0.03) *** | −0.23 (0.04) *** | 0.21 (0.03) *** | −0.16 (0.03) *** |

| Asian adolescents | ||||

| Early adolescence | ||||

| HSLS | 0.24 (0.11) * | −0.11 (0.09) | 0.03 (0.09) | 0.05 (0.08) |

| Late adolescence | ||||

| HSLS | 0.48 (0.12) *** | −0.49 (0.08) *** | 0.29 (0.09) *** | −0.24 (0.06) *** |

| Latinx adolescents | ||||

| Early adolescence | ||||

| HSLS | 0.23 (0.06) *** | −0.14 (0.06) * | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.10 (0.05) * |

| Late adolescence | ||||

| HSLS | 0.14 (0.07) * | −0.04 (0.07) | 0.18 (0.05) *** | −0.09 (0.05) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Starr, C.R.; Gao, Y.; Rubach, C.; Lee, G.; Safavian, N.; Dicke, A.-L.; Eccles, J.S.; Simpkins, S.D. “Who’s Better at Math, Boys or Girls?”: Changes in Adolescents’ Math Gender Stereotypes and Their Motivational Beliefs from Early to Late Adolescence. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090866

Starr CR, Gao Y, Rubach C, Lee G, Safavian N, Dicke A-L, Eccles JS, Simpkins SD. “Who’s Better at Math, Boys or Girls?”: Changes in Adolescents’ Math Gender Stereotypes and Their Motivational Beliefs from Early to Late Adolescence. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(9):866. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090866

Chicago/Turabian StyleStarr, Christine R., Yannan Gao, Charlott Rubach, Glona Lee, Nayssan Safavian, Anna-Lena Dicke, Jacquelynne S. Eccles, and Sandra D. Simpkins. 2023. "“Who’s Better at Math, Boys or Girls?”: Changes in Adolescents’ Math Gender Stereotypes and Their Motivational Beliefs from Early to Late Adolescence" Education Sciences 13, no. 9: 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090866

APA StyleStarr, C. R., Gao, Y., Rubach, C., Lee, G., Safavian, N., Dicke, A.-L., Eccles, J. S., & Simpkins, S. D. (2023). “Who’s Better at Math, Boys or Girls?”: Changes in Adolescents’ Math Gender Stereotypes and Their Motivational Beliefs from Early to Late Adolescence. Education Sciences, 13(9), 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13090866