Methodologies for Fostering Critical Thinking Skills from University Students’ Points of View

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

- Feedback: A study by Castro and González-Palta [44] shows that most of the participant students perceived that the use of peer feedback and discussion through social networks, concretely Facebook, contributed to the development of critical thinking. Besides, there was a general degree of satisfaction and a favorable attitude towards the use of this platform to complement their classes.

- Debate: Lira Valdivia [8] highlights the importance of using active methodologies, and in particular, the face-to-face forum, for the development of critical thinking in higher education. Students value this methodology at a cognitive level, favoring “understanding complex ideas”, “ability to analyze problems”, “learning to confront different ideas”, “rethinking opinions before expressing them”, and the “ability to reflect”, to name but a few. Moreover, attitudinal aspects were described, such as “motivation to learn”, “valuing consensus”, “respect for the opinion of others”, “honesty in facing weaknesses”. Scott’s [16] study, which included 111 students in a technology classroom, also examines the effectiveness of debates for developing critical thinking. The results showed that students believed that this methodology helped them to improve their critical thinking skills due to the fact that debates require research, assessing arguments, analysis, questioning assumptions, and demonstrating interpersonal skills. This finding was also shared by Zare and Othman [19], who reached similar conclusions with undergraduate students majoring in Teaching English as a Second Language. According to their study, students thought that they developed their critical thinking skills through debates, as they had to look for evidence and proof to support their arguments and consider different perspectives, as well as points of view. Finally, Zelaieta and Camino [45] found that undergraduate students in Early Childhood Education stated that academic debates in the classroom improved their critical thinking skills as they had to search and analyze information.

- Problem-Solving, Service Learning, and Reflective Learning: Collazo Expósito and Geli de Ciurana [46] analyzed students’ points of view about three methodologies employed for the development of critical thinking: Problem-solving, service learning, and reflective learning through a teaching portfolio. Results showed that 90% of the 30 students surveyed were convinced that the application of active methodologies allowed them to develop critical thinking, teamwork, the search for solutions, and understand their surroundings in such a way that they could feel the need to engage themselves to change it for better. Approximately 82% of the participants strongly agreed that the problem posed as a starting point for PBL is essential for their learning process. PBL allows them to work on critical and reflective thinking, and providing a link with real experience and emotions is an effective way to foster greater engagement with the environment. Moreover, 83% of the students agreed that sometimes the questions or learning resources used in the classroom provoked a dilemma or reflection concerning their previous ideas on the topics covered. Further, 77% of the students thought that they sometimes preferred lectures, and 73% said that they would always like to be able to apply some of what they have learned in their work as a secondary school teacher.

- Practices in real contexts: García-Carpintero [47] analyzed the thoughts of students regarding the use of a portfolio as a part of an internship context subject (practicum). Results showed that the portfolio was a tool that facilitated students’ reflection and critical thinking during their practicum. They saw it as a valuable resource that facilitated self-assessment through a reflective process, as well as generating self-criticism, and the analysis of their practice. This process allowed them to make changes in order to improve their learning.

- Flipped Classroom: Rodríguez et al. [9] applied the Flipped Classroom methodology with Medicine students. They mixed jigsaw, cooperative work, and role-play activities. The students thought these activities and methodology contributed to the development of their critical thinking skills, as they had to use their imagination, reflect, and discuss different issues, and thus, the methodology led them to construct sound arguments, elaborate new ideas, and consider different points of view.

- Role-playing: Latif et al. [48] observed that role play and debate were both well accepted by medical students in the Problem-Based Learning curriculum as an effective teaching methodology. Both were perceived as good methodologies for improving critical thinking skills. However, role play was perceived as better than debates for integrating knowledge of basic medical sciences into clinical skills and reflecting on real-life experiences.

- Doing Research: Sahoo and Mohammed [49] claimed that medical students reported improvement in their critical thinking skills when doing research for writing tasks. All participants agreed that it helped to apply concepts to new situations in their studies. Moreover, it enhanced higher-order cognitive skills.

- Case studies: González-González and Jiménez-Zarco [50] found that, according to students, the use of audio-visual cases in an e-learning context helped students reach accurate problem identification, sensible problem resolution, and critical thinking development.

- RQ1: What are the main methodologies that, according to students, contribute more to developing critical thinking?

- RQ2: Is the perceived effectiveness of the methodologies for developing critical thinking different based on the conception the students have about critical thinking?

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

3.2. Instruments

- From these six dimensions, students were asked to choose a maximum of three dimensions that corresponded more to their understanding of critical thinking.

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Theoretical Model of the Different Dimensions of CT (Bezanilla et al., 2018)

- Analyzing/organizing: These are answers that refer to critical thinking as a way of examining something in detail (a text, a reality...) considering its parts in order to know its characteristics and draw conclusions. In some cases, they include aspects related to the structuring and organization of information, but do not go beyond that (e.g., I analyze the information by contrasting different sources).

- Reasoning/arguing: These definitions add to the analysis the relation and comparison of ideas and experiences based on arguments, to obtain conclusions and form a reasoned judgment. It involves expressing in words or in writing reasons for or against something, or justifying it as a reasonable action to convey a content and promote understanding (e.g., When I give my opinion I provide reasons or arguments that justify it).

- Questioning/asking oneself: Critical thinking is understood as the questioning of an issue that is controversial or commonly accepted. It means to question things, to ask oneself questions about the reality in which one lives (e.g., When reading an article, I ask myself questions about the topics covered).

- Evaluating: It means to value, to weigh, to determine the value of something, to estimate the importance of a fact, taking into account various elements or criteria. It is more than an argumentation (deducing pros and cons of a reality) because it implies determining the value of something according to certain criteria (e.g., Before making a decision, I evaluate the pros and cons of the situation).

- Taking a position/taking decisions: It implies not only analyzing, reasoning, questioning or evaluating, but also making a decision about it. It means to give a solution or make a definitive judgment on a matter in a certain way, including a position or proposed solution (e.g., When I make a decision, I take it and move forward, despite the fact that others may think differently).

- Acting/compromising: Critical thinking is understood as a means of transforming reality through social commitment. It is to take action, to act, to behave by performing voluntary and conscious acts in a determined and committed manner. It implies the adoption of a certain attitude or position before a certain matter (e.g., I get involved to respond to a situation of injustice or inequality).

References

- Song, X. ‘Critical Thinking’ and Pedagogical implications for higher education. East Asia 2016, 33, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezanilla, M.J.; Poblete, M.; Fernández-Nogueira, D.; Arranz, S.; Campo, L. El pensamiento crítico desde la perspectiva de los docentes universitarios. Estud. Pedagógicos 2018, 44, 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koreshnikova, Y.N.; Froumin, I.D. Teacher Professional Skills as a Factor in the Development of Students Critical Thinking. Psychol. Sci. Educ. 2020, 25, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, N.; Hackworth, R.; Case-Smith, J. Perceptions of the use of critical thinking teaching methods. Radiol. Technol. 2012, 83, 226–252. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelowicz, K.; Bain, J.D. Identifying academics’ orientations to assessment practice. High. Educ. 2002, 43, 173–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.; Baskerville, R. The experience of deep learning by accounting students. Account. Educ. Int. J. 2013, 22, 582–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marton, F.; Saljo, R. On qualitative differences in learning 2- Outcome as a function of the learner’s conception of the task. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1976, 46, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira-Valdivia, R.I. Las metodologías activas y el foro presencial: Su contribución al desarrollo del pensamiento crítico. Actual. Investig. Educ. 2010, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, G.; Díez, J.; Pérez, N.; Baños, J.E.; Carrió, M. Flipped classroom: Fostering creative skills in undergraduate students of health sciences. Think. Ski. Creat. 2019, 33, 100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumoto, Y. Enhancing critical thinking through active learning. CercleS 2018, 8, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourth Zambrano, S.; Tabares Díaz, Y.; Martínez Daza, V. Programa de intervención en debate crítico sobre el pensamiento crítico en universitarios. Educación y Humanismo 2020, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikeleze, M.; Johnson, I.; Gibson, T. Let’s Argue: Using Debate to Teach Critical Thinking and Communication Skills to Future Leaders. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2018, 17, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitru, D.; Bigu, D.; Elen, J.; Ahern, A.; McNally, C.; Ciaran, O. A European Review on Critical Thinking Educational Practices in Higher Education Institutions; UTAD: Vila Real, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Irman, J.N.; Angraini, N. Discussion Task Model in EFL classroom: EFL learners’ perception, oral proficiency, and critical thinking achievements. Pedagogika 2019, 133, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Dono, A.; Hernández-Fernández, A. Fostering Sustainability and Critical Thinking through Debate—A Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S. Perceptions of students’ learning critical thinking through debate in a technology classroom: A case study. J. Technol. Stud. 2008, 34, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.C.; Rusli, E. Using debate as a pedagogical tool in enhancing pre-service teachers’ learning and critical thinking. J. Int. Educ. Res. 2012, 8, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamir, S.; Yang, Z.; Sarwar, U.; Maqbool, S.; Fazal, K.; Ihsan, H.M.; Arif, A. Teaching methodologies used for learning critical thinking in higher education: Pakistani teachers’ perceptions. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2021, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, P.; Othman, M. Students’ perceptions toward using classroom debate to develop critical thinking and oral communication ability. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aránguiz, P.; Palau-Salvador, G.; Belda, A.; Peris, J. Critical Thinking Using Project-Based Learning: The Case of the Agroecological Market at the “Universitat Politècnica de València”. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortázar, C.; Nussbaum, M.; Harcha, J.; Alvares, D.; López, F.; Goñi, J.; Cabezas, V. Promoting critical thinking in an online, project-based course. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddoura, M.A. New Graduate Nurses’ Perceptions of the Effects of Clinical Simulation on Their Critical Thinking, Learning, and Confidence. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2010, 41, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarifsanaiey, N.; Amini, M.; Saadat, F. A comparison of educational strategies for the acquisition of nursing student’s performance and critical thinking: Simulation-based training vs. integrated training (simulation and critical thinking strategies). BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrami, P.; Bernard, R.; Borokhovski, E.; Waddington, D.I.; Wade, C.A.; Persson, T. Strategies for teaching students to think critically: A meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2015, 85, 275–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios Araya, S.; Rubio Acuña, M.; Gutiérrez Núñez, M.; Sepúlveda Vería, C. Aprendizaje-servicio como metodología para el desarrollo del pensamiento crítico en educación superior. Rev. Cuba. De Educ. Médica Super. 2012, 26, 594–603. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntjara, E.H. Students’ reflection on their service-learning experience as a way of fostering critical thinking and a peace building initiative. Citizsh. Teach. Learn. 2019, 14, 225–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangalaya Sevillano, L.M. Habilidades del pensamiento crítico en estudiantes universitarios a través de la investigación. Desde El Sur 2020, 12, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, S.; Sánchez, P. Efectos del entrenamiento de profesores en el pensamiento crítico en estudiantes universitarios. Rev. Latinoam. De Estud. Educ. 2008, 38, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez-López, S.; Ávila-Palet, J.E.; Olivares-Olivares, S.L. The development of critical thinking abilities in university students by means of problem-based learning. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Super 2017, 8, 84–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Olivares, S.L.; Heredia, Y. Desarrollo del pensamiento crítico en ambientes de aprendizaje basado en problemas en estudiantes de educación superior. Rev. Mex. De Investig. Educ. 2012, 17, 759–778. [Google Scholar]

- Orique, S.B.; McCarthy, M.A. Critical thinking and the use of nontraditional instructional methodologies. J. Nurs. Educ. 2015, 54, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrutia, M.E.; Hamui-Sutton, A.; Castañeda, S.; Fortoul, T.I.; Guevara-Guzmán, R. Impacto del aprendizaje basado en problemas en los procesos cognitivos de los estudiantes de medicina. Gac. Médica De México 2011, 147, 385–393. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.; Preston, A.; Kharruga, A.; Kong, Z. Making L2 learners’ reasoning skills visible: The potential of computer supported collaborative learning environments. Think. Ski. Creat. 2016, 22, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popil, I. Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Educ. Today 2011, 23, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDade, S.A. Case study pedagogy to advance critical thinking. Teach. Psychol. 1995, 22, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, R.; McNamara, P.M.; Seery, N. Promoting deep learning in a teacher education programme through self- and peer-assessment and feedback. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 35, 179–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, S.; Rofiuddin, A.; Nurhadi, N.; Priyatni, E.T. Development of mass media text-based instructional materials to improve critical reading skills of university students. Pedagogika 2018, 131, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bezanilla, M.J.; Fernández-Nogueira, D.; Poblete, M.; Galindo-Domínguez, H. Methodologies for teaching-learning critical thinking in higher education: The teacher’s view. Think. Ski. Creat. 2019, 33, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islamiyah, M.; Fajri, M. Investigating Indonesian Master’s students’ perception of critical thinking in Academic Writing in a British university. Qual. Rep. 2020, 25, 4402–4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusri. The Effects of Problem Solving, Project-Based Learning, Linguistic Intelligence and Critical Thinking on the Students’ Report Writing. Adv. Lang. Lit. Stud. 2018, 9, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dwyer, C.R.; Hogan, M.J.; Steward, I. The promotion of critical thinking skills through argument mapping. In Critical Thinking; Horvath, C.P., Forte, J.M., Eds.; Nova Science: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Dehghanzadeha, S.; Jafaraghaee, F. Comparing the effects of traditional lecture and flipped classroom on nursing students’ critical thinking disposition: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 71, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodzalan, S.A.; Saat, M.M. The perception of critical thinking and problem solving among Malaysian undergraduate students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 172, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, P.J.; González-Palta, I.N. Percepción de Estudiantes de Psicología sobre el Uso de Facebook para Desarrollar Pensamiento Crítico. Formación Universitaria 2016, 9, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelaieta, E.; Camino, E. El desarrollo del pensamiento crítico en la formación inicial del profesorado: Análisis de una estrategia pedagógica desde la visión del alumnado. Profesorado Rev. De Currículum Form. Del Profr. 2018, 22, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collazo Expósito, L.M.; Geli de Ciurana, A.M. Avanzar en la educación para la sostenibilidad. Combinación de metodologías para trabajar el pensamiento crítico y autónomo, la reflexión y la capacidad de transformación del sistema. Rev. Iberoam. De Educ. 2017, 73, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carpintero, E. El portafolio como metodología de enseñanza-aprendizaje y evaluación en el practicum: Percepciones de los estudiantes. REDU. Rev. De Docencia Univ. 2017, 15, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, E.; Mumtaz, S.; Mumtaz, R.; Hussain, A. A comparison of debate and role play in enhancing critical thinking and communication skills of medical students during problem based learning. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2018, 46, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Mohammed, C.A. Fostering critical thinking and collaborative learning skills among medical students through a research protocol writing activity in the curriculum. Korean J. Med. Educ. 2018, 30, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-González, I.; Jiménez-Zarco, A.I. Using learning methodologies and resources in the development of critical thinking competency: An exploratory study in a virtual learning environment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 51, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrari, A.; Samah, B.A.; Hassan, S.H.B.; Wahat, N.W.A.; Zaremohzzabieh, Z. Deepening critical thinking skills through civic engagement in Malaysian higher education. Think. Ski. Creat. 2016, 22, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, R.; Gulveren, H.; Aydin, E. A research on critical thinking tendencies and factors that affect critical thinking of higher education students. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 9, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Calderón, N. Implementación de la estrategia didáctica del desarrollo del pensamiento crítico-reflexivo en el análisis literario de Hamlet de Shakespeare. Educación 2014, 38, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ahuna, K.H.; Tinnesz, C.G.; Kiener, M. A New Era of Critical Thinking in Professional Programs. Transformative Dialogues. Teach. Learn. J. 2014, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bovill, C. A Co-creation of Learning and Teaching Typology: What Kind of Cocreation are you Planning or Doing? Int. J. Stud. Partn. 2019, 3, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminskiene, L.; Žydžiunaite, V.; Jurgile, V.; Ponomarenko, T. Co-Creation of Learning: A Concept Analysis. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 2020, 9, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methodologies | f (%) |

|---|---|

| Debates | 650 (19.7%) |

| PBL | 468 (14.2%) |

| Practices in real contexts | 364 (11.0%) |

| Doing research | 321 (9.7%) |

| Cooperative learning | 312 (9.5%) |

| Case studies | 263 (8.0%) |

| Feedback | 195 (5.9%) |

| Role-playing | 170 (5.1%) |

| Reading and analysis of resources | 161 (4.9%) |

| Written work | 114 (3.4%) |

| Conceptual maps | 103 (3.1%) |

| Service learning | 63 (1.9%) |

| Oral presentations | 59 (1.8%) |

| Flipped classroom | 30 (0.9%) |

| Master classes | 21 (0.6%) |

| Others | 2 (>0.01%) |

| Total | 3296 (100%) |

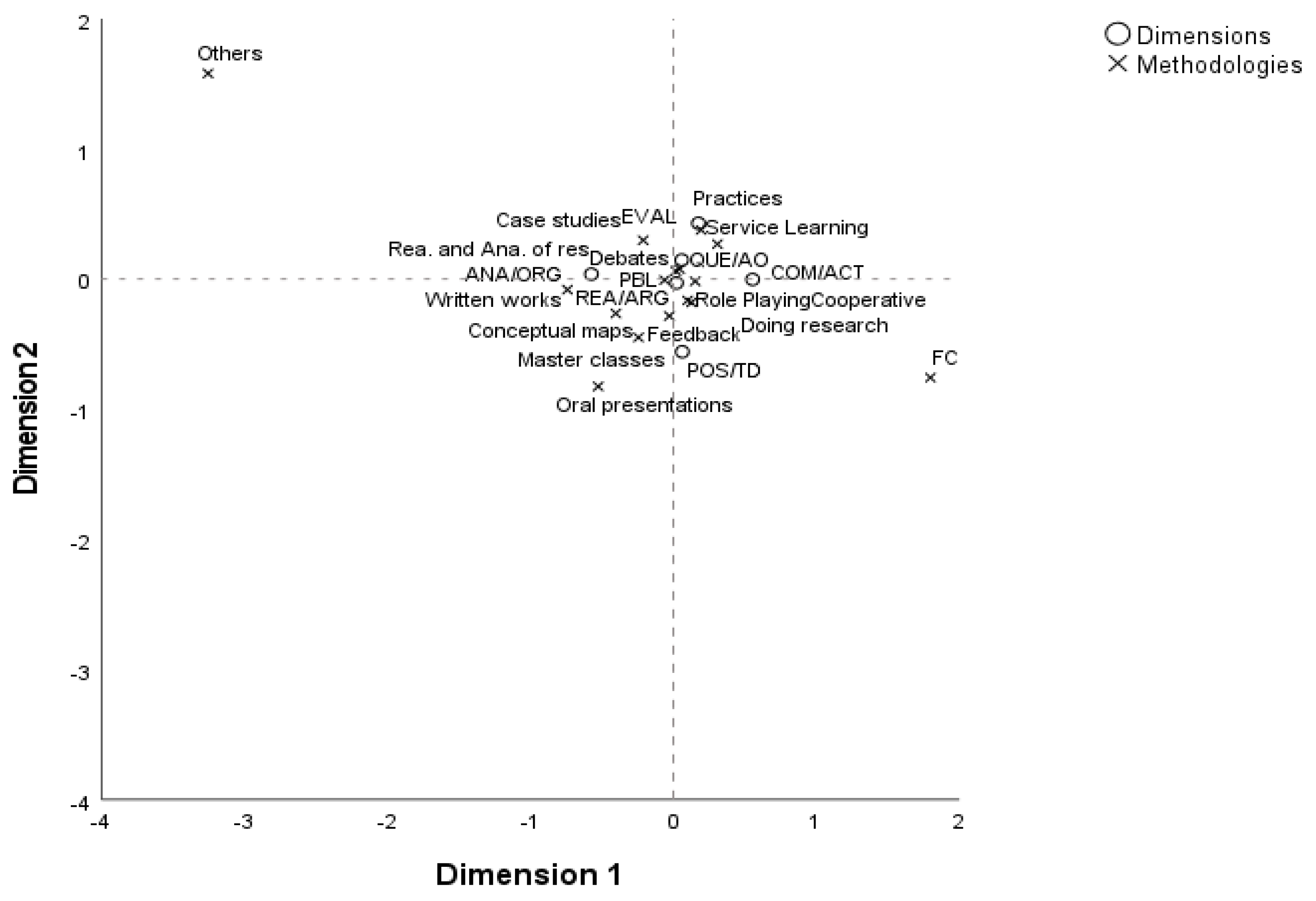

| ANA/ORG | REA/ARG | QUE/AO | EVAL | POS/TD | COM/ACT | TOTAL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debates | 97 | 190 | 185 | 49 | 78 | 51 | 650 |

| PBL | 75 | 134 | 127 | 36 | 59 | 37 | 468 |

| Practices | 49 | 110 | 110 | 29 | 34 | 32 | 364 |

| Doing research | 43 | 94 | 97 | 18 | 43 | 26 | 321 |

| Cooperative learning | 45 | 92 | 79 | 26 | 44 | 26 | 312 |

| Case studies | 47 | 77 | 68 | 24 | 27 | 20 | 263 |

| Feedback | 31 | 58 | 50 | 12 | 27 | 17 | 195 |

| Role-playing | 25 | 50 | 47 | 11 | 20 | 17 | 170 |

| Reading and analysis of resources | 22 | 50 | 47 | 12 | 19 | 11 | 161 |

| Written work | 24 | 34 | 28 | 9 | 15 | 4 | 114 |

| Conceptual maps | 21 | 30 | 25 | 5 | 13 | 9 | 103 |

| Service learning | 10 | 17 | 14 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 63 |

| Oral presentations | 11 | 19 | 14 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 59 |

| Flipped classroom | 0 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 30 |

| Master classes | 4 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 21 |

| Others | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 505 | 970 | 904 | 244 | 405 | 268 | 3296 |

| Dimension | Singular Value | Inertia | χ2 | Proportion of Inertia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accounted for | Cumulative | ||||

| 1 | 0.079 | 0.006 | 0.440 | 0.440 | |

| 2 | 0.058 | 0.003 | 0.240 | 0.680 | |

| 3 | 0.052 | 0.003 | 0.193 | 0.873 | |

| 4 | 0.038 | 0.001 | 0.100 | 0.972 | |

| 5 | 0.020 | 0.000 | 0.028 | 1.00 | |

| Total | 0.014 | 46.86 (p = 0.996) | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campo, L.; Galindo-Domínguez, H.; Bezanilla, M.-J.; Fernández-Nogueira, D.; Poblete, M. Methodologies for Fostering Critical Thinking Skills from University Students’ Points of View. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020132

Campo L, Galindo-Domínguez H, Bezanilla M-J, Fernández-Nogueira D, Poblete M. Methodologies for Fostering Critical Thinking Skills from University Students’ Points of View. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(2):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020132

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampo, Lucía, Héctor Galindo-Domínguez, María-José Bezanilla, Donna Fernández-Nogueira, and Manuel Poblete. 2023. "Methodologies for Fostering Critical Thinking Skills from University Students’ Points of View" Education Sciences 13, no. 2: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020132

APA StyleCampo, L., Galindo-Domínguez, H., Bezanilla, M.-J., Fernández-Nogueira, D., & Poblete, M. (2023). Methodologies for Fostering Critical Thinking Skills from University Students’ Points of View. Education Sciences, 13(2), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13020132