Abstract

In the process of urbanization in China, the migrant worker population entering cities is an important force in building cities. The children of these migrant workers who do not have the qualifications to participate in college entrance examinations in the city generally become floating rural students. The education problem of the children of the migrant worker population entering the city is still insufficiently considered, and the education inequality and skill formation defects faced by floating rural students are worth paying attention to. This study selected P Middle School in Daxing District of Beijing as a case and took “input–process–output” as the thread to investigate and analyze the school’s source of students and enrollment situation, survival strategy and student graduation destination. It tried to present the original ecology of the school’s survival situation from the micro level and further interpret the education inequality and skill formation of floating rural students from the perspective of the school’s survival. Through the case study, we have found that the academic achievement of students in privately run schools for migrant workers’ children is not high. The level of teachers in these schools is low, and teacher turnover is high, resulting in a significant gap in the quality of education compared to public schools. The main source of funding for these schools is donations from members of the community, and government funding is inadequate. Floating rural students in privately run schools for migrant workers’ children have poor graduation destinations, with a low percentage of students going on to key high schools, and some students are forced to become returning children, facing institutional barriers to upward mobility through education. These aspects have led to education inequality and possible defects in the skill formation of floating rural students. We hope to clarify and grasp the actual situation of privately run schools for migrant workers’ children and put forward corresponding policy recommendations to help bridge the educational inequity in China.

1. Introduction

In recent years, China’s private education industry has developed rapidly. By the end of 2020, there were a total of 186,700 private schools (including preschool education) at all levels across the country, accounting for 34.76% of the total number of schools in the country, with 55.6 million students in school, accounting for 19.92% of the total number of students in school in the country [1]. Among them, compulsory education has received widespread attention as a form of public welfare that the state must guarantee. To regulate and promote the development of private compulsory education, the central and local governments’ reform exploration has been continuous. On 1 September 2020, the Central Committee for Comprehensive Deepening Reform passed the “Implementation Opinions on Regulating the Development of Private Compulsory Education”, which further included private compulsory education in the important policy agenda. According to the “Private Education Promotion Law of the People’s Republic of China” (revised in 2018), private schools are educational institutions held by social organizations or individuals outside of state institutions, using nonstate financial funds, and facing society. Currently, there are three main types of private schools in China. The first type is elite schools, which are private schools that accommodate families and provide international and elite education services with high charges. The second type is characteristic development schools, which have formed distinctive characteristics of operation after a certain period, with moderate charges. Parents’ paying for these schools is essentially due to public schools not being able to meet their demand for superior educational resources. The third type is privately run schools for migrant workers’ children, which are specifically established to meet the education needs of floating rural students with low charges [2]. In general, floating rural students refer to the population who are under 18 years old and have left their place of residence for more than 6 months with their parents from rural to urban areas [3,4]. In the process of urbanization in China, an increasing number of children of migrant workers have migrated with their parents to seek better educational opportunities in cities. However, due to the limited carrying capacity of urban education centers and the restriction of the expansion period of education, urban areas have set higher enrollment thresholds for public schools for floating rural students, who must choose to enter privately run schools for migrant workers’ children. As a special form of education that emerged in the process of urbanization in China [5], the survival situation and related problems of privately run schools for migrant workers’ children urgently needs attention and discussion.

According to the National Educational Development Statistics Bulletin, in 2020, 14.3 million students received compulsory education among the migrant population, accounting for 9.2% of the total number of students receiving compulsory education. The acceptance and protection of floating rural students in the place of reception have become a focus of policy discussion. In China, the implementation of compulsory education is based on household registration, meaning that once a child leaves their registered place of residence, their right to compulsory education is also lost. As a result, children of migrant workers become a vulnerable group in the places they move to. In other words, the main reason for sending children of migrant workers to schools for the children of migrant workers is that the government is unable to provide adequate educational opportunities in public schools. Furthermore, the problem of education for children of migrant workers in China is a systematic engineering problem. There are complex interests between the governments of the places they move to, public schools, private schools and the children and families of migrant workers, which weaken the effectiveness of policies to a large extent. In terms of admission and promotion policies, relevant policies such as “mainly managed by the place of reception, mainly by public schools” and “different place entrance examination” have, to a certain extent, guaranteed the legality of floating rural students receiving education in the place of reception. However, the specific policies introduced by local governments have imposed strict restrictive conditions on floating rural students’ admission and promotion in the place of reception, such as legal guardian work permits, actual residence certificates, family household registers, temporary residence permits in Beijing, and no-guardian condition certificates issued by relevant departments of the place of household registration. These hard requirements constitute insurmountable institutional barriers for most migrant families. Relevant evidence shows that whether floating rural students can enter public schools often depends on the economic and social resources of their own families. Students whose parents have unstable jobs, low income, and lack of social relationships are more likely to be rejected by public schools [6,7,8].

In terms of education financial protection policies, in 2015, the “Notice of the State Council on Further Improving the Financial Protection Mechanism for Urban and Rural Compulsory Education” officially announced the cancellation of the central government’s award and subsidy policies for urban compulsory education exemption of miscellaneous fees and floating rural students of urban workers receiving compulsory education, replaced by the new “money follows the person” policy. Therefore, the central government assumes part of the educational expenses of floating rural students of migrant workers on a project-by-project basis, while local governments have a certain amount of room to do their own thing and shirk their responsibilities, resulting in various local models for solving the financial burden of compulsory education for floating rural students of migrant workers. For instance, Shanghai City provides free compulsory education for eligible floating rural students through public schools. Zhejiang Province is based on public schools with private schools as supplements, and Guangdong Province deviates from the central government’s principle of “management by destination and public schools as the mainstay” and relies on private schools to provide compulsory education for floating rural students [9]. In the implementation process of policies, although the central government’s policy goals are ambitious, the ability and enthusiasm of local government policy implementers may not be as expected [10]. Faced with the influx of a large number of floating rural students, the local government often lacks financial support for public schools, and there is a phenomenon of insufficiency of public school enrollment quotas, and schools charging extra fees to floating rural students or depriving them of the opportunity to receive education are common in many cities [11,12,13]. In addition, under the Chinese school grading system, top schools are usually elite public schools or expensive private schools, which typically have superior infrastructure, strong faculties and comprehensive curricula and can provide a better environment for floating rural students [14]. However, floating rural students often lack the necessary resources to enter these schools and have to choose lower-grade migrant workers’ school [15], which contrasts sharply with their higher educational expectations [16]. As a result, floating rural students become the most vulnerable group to be deprived of the opportunity to study, facing the reality of unequal educational opportunities and unequal education processes.

As a special form of education, privately run schools for migrant workers’ children objectively provide education opportunities for children of migrant workers who cannot enter urban public schools. In recent years, privately run schools for migrant workers’ children have received more social donations and local government subsidies, and many poorly managed privately run schools for migrant workers’ children have been closed or taken over by the government. Therefore, the conditions for running privately run schools for migrant workers’ children have improved greatly [17]. However, despite this, the quality of education in most privately run schools for migrant workers’ children is poor, and the schools themselves face multiple crises. Specifically, privately run schools for migrant workers’ children often lack a stable source of funding and have limited teaching resources [18,19]. The quality of teachers in privately run schools for migrant workers’ children is generally low, with low wages, long working hours, and heavy workloads, leading to high teacher turnover [20,21]. Due to a lack of policy supervision and institutional support, privately run schools for migrant workers’ children often face the risk of closure and are unable to continuously provide educational resources for floating rural students [22]. As a result, most privately run schools for migrant workers’ children are unable to provide a supportive educational environment for floating rural students, which can undermine their academic progress and hinder the development of key skills. Studies have shown that compared to local students and floating rural students who attend public schools, students who attend privately run schools for migrant workers’ children perform worse academically [23]. Students in privately run schools for migrant workers’ children are more likely to suffer from mental health problems [11,24], lower levels of self-esteem and life satisfaction [25], and experience higher levels of stress, loneliness, depression, and social anxiety [26,27]. In addition, students in privately run schools for migrant workers’ children have lower quality employment prospects and face the challenge of class reproduction [28]. On the one hand, most floating rural students who complete junior high school choose to leave the city where they are studying when they enter high school, either to enter the labor market or to attend low-quality vocational schools, because they do not have the qualifications to take the college entrance exam or cannot afford to attend public high schools [29,30]. On the other hand, many students are forced to return to their hometowns to receive poor-quality education, meaning their chances of attending college are slim, and some students even choose to drop out due to poor adaptation [31]. A recent survey also reveals a more pessimistic conclusion that regardless of the qualifications, educational financial investment and early career aspirations of floating rural students, this group will ultimately be channeled into low-skilled urban service jobs [32].

The well-being of floating rural students is closely related to their educational achievements and China’s future social and economic development. Therefore, it is important and urgent to improve the learning and living conditions of floating rural students [33]. However, there are few studies on the educational experiences of floating rural students in privately run schools for migrant workers’ children, and the understanding of the actual living conditions of these schools is also limited. To bridge the literature gap, this study takes P Middle School in Daxing District of Beijing as a case study to microscopically investigate the actual living conditions of privately run schools for migrant workers’ children and related issues. In terms of research methods, quantitative studies are limited in their examination of meaning and the complexity of action interpretation. The case study is best suited to instances in which: the type of question is the ‘how’ and ‘why’, the object of study is a current event, and the researcher has little or no control over the current event. Therefore, this study adopts a case study approach, attempting to use the “input–process–output” as the guiding principle to analyze the source of students and enrollment situation, survival strategy, teaching quality and student graduation destination of P Middle School. It presents the original ecology of the school’s living conditions from a micro perspective, grasps the actual situation of the development of privately run schools for migrant workers’ children, and further interprets the educational inequality and skill formation difference of floating rural students from the perspective of the school’s way of survival to help bridge the phenomenon of educational inequity in China.

2. Research Strategy

2.1. Selection of Research Cases

This study selected P Middle School as a case study for two reasons. First, the appropriateness of the school’s nature. P Middle School was established in the spring of 2005 and is located in Daxing District, Beijing. The school building has an area of nearly 4000 square meters. P Middle School is a privately run school for migrant workers’ children, with a public welfare and nonprofit private middle school positioning, adhering to the principle of “returning the right to receive a qualified education to the children of migrant workers.” Since its official establishment in 2005, the school has received attention and support from various sectors of society. Under the policy background of the Beijing Municipal Government’s active response to the central leadership and the issuance of the “Opinions on Encouraging Social Forces to Promote the Healthy Development of Private Education,” the survey of P Middle School has important practical significance and necessity. Second, exploration space and research value. In March 2014, the central government issued the “National New Urbanization Plan (2014–2020)”, which required that “the population size of large cities with more than 5 million people in urban areas should be strictly controlled”. In accordance with this, the Beijing Municipal Government has adopted multiple measures to control the population, such as “controlling people by industry” and “controlling people by housing”. Since the implementation of the policy, several “incompetent” or unqualified privately run schools for migrant workers’ children have been shut down in Beijing. However, P Middle School has survived to this day due to its strong spirit of education and unique action strategies. Therefore, this research attempts to decode privately run migrant workers’ schools’ way of survival through a case study.

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

This study mainly uses interviews and observations to collect data. Before the survey, the researcher carefully reviewed relevant policy documents and literature on the operation of floating rural students’ schools and developed an interview outline (as shown in Appendix A). At the same time, based on the school’s official website, WeChat public platform and other media platforms, key information is collected to facilitate timely and effective follow-up interviews. This study uses the principle of purposive sampling and selects one school leader, one teacher representative, and two middle school students from P Middle School as interviewees. At the same time, we also visited the teaching facilities, teacher’s offices, library, and other places at the case school, obtaining fresh materials and extracting valuable information from them. After obtaining the consent of the interviewees, we recorded the interview dialog and promptly organized and analyzed the interview data.

3. Case Presentation and Analysis

This study uses the “input–process–output” model as a context clue and analyzes the source of students and enrollment situation, survival strategies, teaching quality, and students’ graduation direction in P Middle School. It presents the original ecology of the school’s living environment from the micro level and interprets the educational inequality and skill formation differences of floating rural students from the perspective of the school.

3.1. Input: Source of Students and Enrollment at P Middle School

The intended enrollment for P Middle School is non-Beijing and Beijing residents who have graduated from elementary school; however, the actual enrollment is almost entirely non-Beijing residents. The top three provinces in terms of student population are Henan (37.47%), Hebei (15.75%), and Shandong (13.60%). Currently, P Middle School has 15 classes with a total of 419 students enrolled. Of these, only one student is a Beijing resident, who is the child of a faculty member, while the rest are non-Beijing residents. According to P Middle School’s annual report, nearly 90% of students come from rural households, and over 80% of their parents have been working in Beijing for over 8 years.

The P Middle School has an enrollment quota of approximately 200 students per year. In the early days of the school’s establishment, the school prioritized and admitted students from the poorest families among those who met the basic admission requirements, providing limited enrollment opportunities to the most disadvantaged students.

“Our school’s children are all workers’ children, so their families are relatively poor. More than half of the families are poor, and approximately one-third of the families need support in terms of school fees. In terms of parenting methods, guidance, and accompanying children, most children may be lacking.”(Teachers)

“The students we enroll are not very good at their level. Although some children learned English in primary school, when they are in junior high school, they are not very good at writing 26 letters.”(Teachers)

P Middle School has recently seen a shift in its enrollment trend from “demand exceeding supply” to “supply exceeding demand,” with the number of applicants remaining stable at approximately 170 to 180 per year. P Middle School student attrition is primarily influenced by the Beijing government’s policies, as one teacher mentioned in an interview:

“In recent years, Beijing has begun to concentrate on cleaning up illegal houses, and the number of people renting in Daxing District has decreased. Some families may have left Beijing to go to Hebei. This has actually had a very significant impact on the changes in enrollment numbers in recent years.”(Teachers)

This shows that P Middle School’s students are in a naturally disadvantaged position, which is not conducive to educational equality. On the one hand, these students are forced to enter the school for migrant workers’ children due to restrictions on the admission policy of public schools or economic resource constraints. They usually come from families with poor economic backgrounds, have poor academic foundations, and lack parental support and emotional support. On the other hand, under the influence of Beijing’s population dispersion policy, some students have no choice but to become returning children, following their parents out of Beijing to their hometown. They are deprived of the opportunity to enjoy urban educational resources and face the risk of poor adaptation upon returning to their hometown.

3.2. “Destiny and Pursuit”: P Middle School’s survival strategies

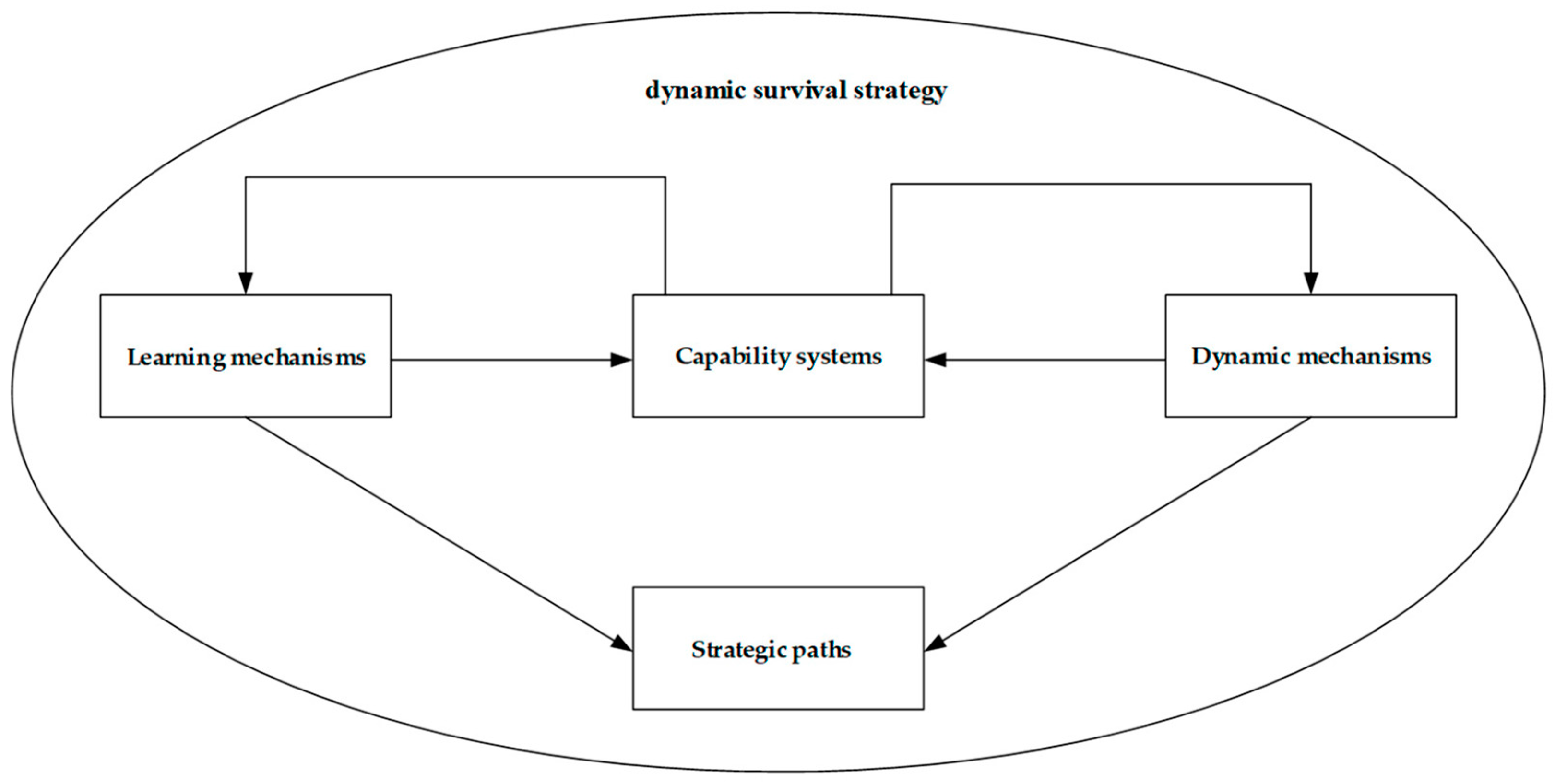

To gain a deeper understanding of the survival situation and strategies of the case study school, we use the dynamic ability framework proposed by Teece et al., including Processes, Positions, and Paths [34], to examine and analyze the survival strategy of P Middle School (as shown in Figure 1). Specifically, we focus on learning mechanisms, capability systems, dynamic mechanisms, and strategic paths.

Figure 1.

Analytical framework of the school’s dynamic survival strategy.

3.2.1. Learning Mechanisms

Private schools in the compulsory education stage may independently carry out education and teaching activities on the premise of completing the curriculum prescribed by the state. In the face of changes and development of the internal and external environment, it is particularly important to form a continuous learning mechanism and make corresponding adjustments to the school’s educational philosophy, curriculum, and teaching methods. With the goal of “returning the right to receive qualified education to the children of migrant workers, and ultimately realizing the integration of educational equity and high-quality education”, P Middle School implements the autonomy of school operation within a reasonable scope through a series of “combined punches”, such as the implementation of the “layered teaching” model and the establishment of a characteristic curriculum system. The survey found that P Middle School encountered difficulties in carrying out the abovementioned curriculum teaching actions. First, the energy of P Middle School teachers is finite, and their basic teaching work consumes more time and emotions. Especially for teachers who have assumed certain management positions, they also need to deal with daily class management and busy administrative work. Second, teachers lack the knowledge and ability to carry out characteristic courses and interest groups, and most teachers in the school lack teaching experience and professionalism that meet the corresponding teaching standards, except for some teachers who were originally interested in and mastered the relevant course content. Third, P Middle School has a limited budget and cannot afford to invest heavily in inviting teachers from outside the school to open classes. In this regard, P Middle School harnesses the power of volunteers. The interviews found that volunteers came to the school from all over the world with a genuine attitude, including senior teachers to provide course guidance and university student clubs or international students to provide services based on their expertise. In summary, the volunteer community is an integral part of the P Middle School education system.

“I think that is what makes P Middle School so attractive and special. In other words, when we want to volunteer, we will first consider whether the recipient group truly needs help. Therefore, when volunteers choose, they will consider coming to us. There is also a caring community from University A that has established a connection with us for many years, which is a good continuation. Such organizations are rare, and perseverance is invaluable to everyone. Therefore, we welcome such clubs and schools.”(Teachers)

In short, P Middle School currently provides low-cost, low-quality education. Existing learning mechanisms can lead to poor skill formation and lower skill formation than in ordinary schools. On the one hand, teachers in privately run schools for migrant workers’ children do not have long teaching experience, the quality of teachers cannot be compared with public schools, and the construction of characteristic courses and interest group activities in schools is also constrained. On the other hand, although P Middle School uses volunteer power to provide supplementary teaching services, most of these volunteers are college students who are highly mobile, and the quality of teaching is uneven; therefore, they cannot provide students’ skills formation and development stable learning guarantees.

3.2.2. Capability Systems

P Middle School adheres to the talent concept of “teachers are priceless”, and the training of teachers is the top priority of the school’s human resources construction. The school has 79 teaching staff, with an average teaching age of 6.1 years, mainly young and middle-aged teachers who are non-Beijing residents with college degrees. Among them, many young people have just graduated and entered society to seek employment. Not only do they lack teaching experience, but they also have to deal with three major challenges: a very weak student base, a tough school environment, and high standards of work but low pay. In the early days of its establishment, the staff turnover rate of P Middle School was as high as 59%. However, over time, the teacher turnover rate has decreased significantly each year and has shown a relatively stable development trend since 2010.

P Middle School implements a principal’s responsibility system under the guidance of the Council, which is composed of volunteers who have achieved certain achievements in various fields, pay attention to education and are passionate about giving back to the community. Major issues related to teaching staff are generally decided jointly by the standing council of the school and the teachers’ union. At the beginning of the establishment of the school, China International Finance Corporation set up the “Special Fund for Teacher Professional Growth” in the school, which has not been interrupted to this day, and has largely supported the school to always take the growth of the teaching team as a top priority and reduce the teacher turnover rate as much as possible. Each semester, the school sets the semester theme according to the mental and ability development of the teaching staff to overcome the weaknesses and deficiencies at the teacher level with collective strength to ultimately help improve the quality of school education and teaching and talent training. The school also provides corresponding training opportunities and training platforms for teachers at different stages of professional development. However, middle school teachers may not have an advantage over the treatment and professional development of public school teachers. In contrast, compared with material incentives, the school provides more spiritual support for teachers and thus attracts a group of teachers who truly recognize the original intention, educational philosophy, and school culture of P Middle School. However, it needs to be recognized that there are still certain differences between private school teachers and public school teachers in terms of professional training, job appointment, calculation of teaching and working years, and commendations and awards.

“We also go to some continuing education schools, but we still do not learn in the same way as public education. Public education actually has a system to accumulate credits. However, we’re just trying to learn. In fact, to be precise, we are not fully integrated into their system by the state.”(Teachers)

“We are in a special industry. We are in a nonprofit organization. The most important thing is that teachers should recognize our school philosophy, be patient and invest energy in education, and be willing to take care of and educate these floating rural students. However, in fact, we are also in the process of finding resources and possibilities. Because teachers have to teach children well, they must also continue to learn.”(Teachers)

Teachers are key to ensuring the quality of education. According to the interviews, although P Middle School has adopted a series of measures to help teachers grow by providing training opportunities and moral support, the problem of teacher turnover in P Middle School should not be underestimated. The interviews found that teachers in private migrant schools not only find it difficult to obtain salaries comparable to those of enterprise employees or public school teachers, but also have to put in more effort and bear great professional pressure due to problems such as poor student quality. These factors greatly reduce the attractiveness of the position for teachers. As a result, the instability of the teaching workforce further exacerbates the educational inequalities faced by floating rural students. On the one hand, teacher mobility disrupts the original teaching arrangements and poses challenges to students’ continuous learning and curriculum management. On the other hand, new teachers often have limited knowledge of students’ academic background, and it is difficult to establish close and stable relationships among teachers, students, and parents, which has a negative impact on students’ ability development for a long time.

3.2.3. Dynamic Mechanisms

The Beijing Municipal People’s Government’s Implementation Opinion on Encouraging Social Forces to Promote the Healthy Development of Private Education (hereinafter referred to as the ‘Implementation Opinion’) clearly states that social organizations or individuals are encouraged to engage in private education in the form of donations, investment, cooperation, and other forms. At the same time, social forces are encouraged to donate to nonprofit private schools and guide nonprofit private schools to use donated funds and school management surpluses to apply for the establishment of education foundations (funds) to provide financial support for the development of the school, teachers and students. In P Middle School, social donations are the main source of income for the school’s operation and maintenance. The research found that P Middle School’s total annual income was 10.29 million yuan, of which the social donation income was 8.19 million yuan, accounting for 79.60% of total income; domestic individual donations are the main source of social donation income for P Middle School. Overall, the main way for P Middle School to obtain donations is through the promotion of foundations and spontaneous donations by social figures, and the structure of donors is essentially stable, with individual donations as the mainstay, but the sources are relatively scattered and the amounts are relatively unstable.

In addition, how is the financial support provided by the government? The Implementation Opinion states that city- and district-level finances should arrange funds to support the development of private education and incorporate them into the annual budget to establish and improve a system of government subsidies, clearly defining the subsidy items, objects, standards, and uses. The research found that P Middle School received government subsidies of 907,700 CNY in a year, accounting for 8.82% of the year’s total income, which was relatively small compared to the income from social donations. At present, the government subsidy items for P Middle School mainly include the average quota subsidy of 875 CNY/person/semester for public funds in the compulsory education stage, the free textbook subsidy of 49,223.19 CNY, and some subsidies for basic facilities (such as school electric gate repairs, laboratory construction, projector equipment, etc.). In the interviews, some teachers responded to the issue of government financial support. Overall, for P Middle School, a privately run middle school for workers’ children, social forces fulfill the government’s responsibilities to a certain extent.

“For example, we now have approximately 600,000 yuan a year for heating, and it is actually very difficult to find someone to raise funds. However, for public education, this is a small move in financial allocation. Private education is all self-help with expenses like heating and electricity. Therefore, the pressure on school is truly high.”(A school Leader)

“I think government support is certainly better. Just now we were talking about the chalk in the classroom running out. We might be better off if we did not need to go outside to find resources ourselves. However, we also do not require the government to do everything in one step, which is impossible, and we also want to rely on the help of social forces. Our school is actually picking up the gaps and catching up the education of those children who still have many needs and are not fully covered by the policy. Of course, I also hope to work with the government to do a good job in education.”(A school Leader)

From the above interviews, P Middle School faces challenges in school fundraising, and the lack of government funds is one of the factors leading to poor teaching quality and student training. On the one hand, although government departments provide financial subsidies to privately run schools for migrant workers’ children, there is still a huge gap in funds for these schools. On the other hand, although privately run schools for migrant workers’ children have received strong support from caring people in society, these funds are mostly individual donations, and the sources are scattered. Therefore, the conditions for running privately run schools for migrant workers’ children still have room for improvement. Due to the lack of necessary government funding support, schools are unable to provide sufficient and high-quality teaching resources, and the school’s infrastructure and even curriculum construction are significantly different from those of public schools, which may not be conducive to students’ skill development.

3.2.4. Strategic Paths

The so-called strategic path, for P Middle School, is more of a beautiful vision for education, that is, an appeal and prospect on a normative level. Despite facing numerous obstacles and practical pressures, P Middle School, because of its clear educational positioning and sincere educational philosophy, has a strong irreplaceability. This was also confirmed to some extent in the interviews with the school leader.

“Only those who truly approach the school will realize this problem: what should the child do after elementary school, he does not want to go back and become a left-behind child. Therefore, people in society who care about children’s healthy growth are like this, hoping that there are schools like us to provide children with an opportunity to participate in quality education, so that these children can still have the opportunity to stay with their parents.”(A school Leader)

The achievement of any strategy is largely inseparable from the enrichment of material support and resource supply. With limited government support, “living in the present” is the most prominent survival strategy for P Middle School. P Middle School actively plays the role of a social force to gather effects, link and attract various social subjects, and benefits the development of the school and talent training. Because the school’s operating funds are mainly composed of tuition fees, government support, personal and group donations, and social donations are the main source of school income. Therefore, the school uses these valuable assets in accordance with the principles of high responsibility, professionalism, and transparency. In the early days of the school, the school’s finances were personally accounted for by volunteers from KPMG, and the training of accountants gradually transitioned to supervision. Since its establishment, the school has always regarded good financial management as the lifeline of survival and development and carefully uses hard-won social assets.

Good strategic planning is the key to better training students in privately run schools for migrant workers’ children. P Middle School faced a shortage of school funds and wisely chose to play a role in the development strategy of social forces funding. It is because of the community’s support and the school’s focus on managing its finances that privately run schools for migrant workers’ children are able to ensure basic schooling conditions and provide basic educational opportunities for floating rural students.

3.3. Output: Where to Go after Graduation?

Where do the students of workers’ children schools graduate from junior high school? Data show that the passing rate of P Middle School’s 2019 graduates in the middle school exam is 93.8%, and 85.7% of the total number of graduates enter ordinary high schools, while 14.3% of the total number of graduates enter vocational high schools. However, in 2019, the gross enrollment rate of higher education in China was 89.5%, close to 90%. Longitudinally, after three years of in-school study, P Middle School’s graduates have indeed achieved some academic achievements, and a certain proportion of students have been able to enter the next stage of study. However, horizontally, the proportion of P middle school junior high school graduates entering regular high schools still has a high potential for improvement.

“The proportion of students going to key high schools is not very high. They can go to other provinces to find high schools or vocational schools based on their Beijing high school examination results. Although Hebei Province enrolls students from Beijing to participate in the high school examination, Hebei Province still prioritizes enrolling its own students; unless it has the capacity to enroll more students, it can then recruit students from Beijing. Therefore, in fact, there are actually only one or two key high schools in Hebei province that our students can go to, and they are relatively few. Most good high schools actually do not admit them.”(A school Leader)

According to the interviews, P Middle school students generally go to poor destinations after graduation, and the proportion of students going to key high schools is not high, which is one of the factors that leads to educational inequality. On the one hand, although most students can take exams in Beijing, due to the fierce competition for admission to high schools in their hometowns, students have a hard time attending their favorite high schools and can only go to low-quality vocational schools; on the other hand, some floating rural students are forced to become “returning children” under the influence of the population redistribution policy, facing poor adaptation after returning home. These findings largely echo previous research [28]; that is, the education achievements of students in privately run schools for migrant workers’ children are low after junior high school, and the type of education they receive after junior high school is low. The reasons for the failure of these groups’ “high school dream” and “university dream” include, but are not limited to, family economic reasons, information reasons, lack of self-interest and motivation, education quality, etc. However, a large amount of evidence shows that the real cause of the shattered educational dreams of groups such as urban migrant workers’ children is the series of institutional barriers centered on the household registration system. As previously mentioned, the current education system and college entrance exam system are based on household registration, resulting in the difficulties of migrant children in making decisions at the end of junior high school. Most of the students at P Middle School are non-local residents in Beijing, and the quality of education they receive at school is not high, which leads to their low competitiveness in selective exams; thus, they are unable to enter higher level schools in Beijing after graduating from junior high school.

4. Discussion

4.1. “Good Intentions” but “Insufficient Strength”: Who Will Pay for the Educational Dream of Floating Rural Students?

The mission and values of the case school, P Middle School, have always been to “unite equity and quality education”, and it is also a direction that the teachers of the school recognize and strive for, attracting donations and volunteering from the community. However, in terms of hardware facilities, teaching difficulty, curriculum positioning, and faculty composition, the school’s actual practices reflect only “passable education.” The biggest challenge for the school at present is having “good intentions” but “insufficient strength.” This is not only the reality of P Middle School as a case study but also the current situation of many other privately run schools for migrant workers’ children sharing the same fate and of those privately run schools for migrant workers’ children that have already been shut down.

The “Compulsory Education Law of the People’s Republic of China” clearly stipulates that compulsory education is the education that all eligible children and teenagers must receive and is a form of public welfare undertaking that the state must safeguard. Although the financial policy of compulsory education for children migrating to cities has always been aimed at education equity and the government’s delineation of funding structures and areas of responsibility has gradually become scientific and refined, there is a risk that the policy effect will be weak in the process of policy implementation to a greater or lesser extent. If adequate financial support is not provided to students in privately run schools for migrant workers’ children, the government will not fulfill its obligation under the “Compulsory Education Law” to provide equal access to compulsory education for children of migrant workers. Therefore, who should bear the cost for the education dream of this group, and how should it be done? These issues are worth considering and exploring.

4.2. “Reconcilable Tension”: A Conflict between Market Preferences and Quality Preferences

In contrast to public schools, private schools tend to regulate their schooling behavior based on the market, that is, through means of flexibility such as charging fees, social donations, curriculum and teacher settings, to adjust survival strategies to operate effectively and develop in the long run. Relevant research has found that many domestic privately run schools for children of migrant workers have tailored humanized services in terms of student accommodation and academic counseling. For instance, through flexible enrollment, tuition installments, and frequent home–school communication (such as after-school supervision and home visits), schools meet the educational needs of disadvantaged groups to some extent [35]. A similar finding was observed in this study based on a case study of P Middle School. It can be seen that privately run schools for migrant workers’ children have largely responded to the educational needs of disadvantaged families and are in line with the economic ability of these families and the market preference for accepting compulsory education. At the same time, along with the increasing popularity of higher education, an increasing number of families expect their children to have access to higher education and expect their children to be able to take a place in the first level of the labor market and achieve class mobility due to the sheepskin effect [16]. In China, the traditional idea of “knowledge changing fate” and “study hard and make a good career” is deeply rooted in the hearts of many parents, especially in some rural marginal areas. Parents have a stronger psychological and behavioral tendency to hope that their children can receive a good education to improve their family’s future economic situation. Even though the possibility of obtaining high-quality education is slim in the eyes of most disadvantaged families, it does not affect their view of it as a “stepping stone” to change their fate. The pursuit of high-quality education has given rise to these families’ preference for quality, and as a result, the relationship between market preference and quality preference has become more tense.

4.3. “Not Acclimatized” and “Habits of Division”: “Returning Children” in a Tight Institutional Space

Under the influence of the household registration system and “population control” policies, the migrant population engaged in labor-intensive industries has become the main group of evacuated people, which has forced some floating rural students to follow their parents, who are homeless in the city, to return to their place of household registration. This group is usually referred to as returning children who have lost the opportunity to receive relatively high-quality education and further study in the city and face systemic barriers to upward social mobility through education [22,36]. More importantly, after floating rural students return to their hometown, how to effectively adapt to local education and life has become an urgent practical issue. It is not difficult to imagine that returning children not only feel physiologically unacclimatized due to changes in their living environment but also suffer from huge psychological gaps and alienation due to the habits of division between urban and rural areas. Returning children face difficulties in academic continuity, interpersonal communication, and social adaptation, and their physical and mental health and individual development needs are urgently in need of attention.

5. Policy Implications

5.1. Ensure the Public Welfare of Compulsory Education in Accordance with the Law and Pay Equal Attention to Financial Support and Accountability

Adhere to the government’s legal responsibility to develop compulsory education, in accordance with the law to guarantee the public welfare of compulsory education, and reasonably coordinate the development of public and private compulsory education. The first is to strengthen financial support for privately run schools for migrant workers’ children and improve the quality of school management. In the meantime, we must effectively implement the “Private Education Promotion Law”, clarify the status of floating rural students’ schools and improve the quality of school management through various strategies. Among them, the focus is on financial support, with increased support in terms of average public funding for students and improved school conditions. The second is to implement support and accountability. All private compulsory education schools should be included in the daily supervision of the supervisory responsibility area, and places that do not fulfill the government’s responsibility for the development of compulsory education should be seriously accountable in accordance with relevant regulations. This also greatly enhances the awareness and initiative of private schools to accept external accountability and achieve a win–win situation. The third is to further implement and improve policies for floating rural students to participate in the college entrance examination in the place of flow and improve the fair access mechanism for college entrance examination opportunities.

5.2. Effectively Strengthen the Construction of Teachers and the Attractiveness of Teacher Positions in Schools for Floating Rural Students

The “Private Education Promotion Law” clearly stipulates that teachers in private schools have the same legal status as teachers in public schools. However, in terms of specific policies and practices, there are still differences in the status and policy treatment enjoyed by public and private school teachers. The 2018 “Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council on Comprehensive Deepening the Reform of the Construction of Teachers in the New Era” reaffirmed that private school teachers are legally protected and hold the same rights as public school teachers in terms of professional training, appointment of duties, calculation of teaching and working years, commendation and rewards, scientific research projects, and other aspects. Therefore, the first is step to strengthen the professional development of private school teachers. Particular attention should be given to the professional development of floating rural students’ school teachers. Previous experience has shown that there are differences in the professional preparation and impact on student performance among teachers of different types, and that the professional development of teachers in China requires a more precise system of subject-specific training support [37]. If the level of floating rural students’ school teachers does not reach the required and basic level of professional development, it is unfair to floating rural students. On the one hand, we must strengthen the regulation and management of private schools to protect the legitimate rights and interests of teachers, and on the other hand, we must increase financial support and supervision to ensure that private school teachers and public school teachers have equal training opportunities and learning resources. The second is to speed up the reform of the social insurance system, accelerate the integration of pension insurance for institutions and enterprise employees, and solve the problem of different treatment standards for public and private school teachers after retirement.

5.3. Coordinate Social Forces to Help Improve the Quality of Talent Training in Schools for Floating Rural Students

For the case school, P Middle School should continue to uphold the original intention of running the school and consolidate its own irreplaceability and school attractiveness with its sincere emotions and practical actions. In terms of the overall development of floating rural students’ schools, it is necessary to encourage more individuals and social groups with aspirations for education to provide certain donations to floating rural students’ schools based on their own ability categories. College students at home and abroad should be encouraged to participate in volunteer service activities if they have spare time, play their professional strengths, and use their professional expertise to help build the school’s special curriculum and campus culture. Schools should also actively establish a long-term mechanism for home-school cooperation, enhance the sense of belonging of floating rural students and keep parents informed of the progress and growth of their children in a timely manner.

5.4. Pay Attention to the Physical and Mental Health and Education of Returning Children

In the long term, the fundamental cause of the plight of returning children is the disparity in development levels and the unequal allocation of education resources between urban and rural areas. Therefore, the government needs to further promote the optimization of education resource allocation in rural areas and support the construction of rural schools to improve the quality and attractiveness of rural schools. Urban areas also need to accelerate the reform of the household registration and school enrollment system and create more policy space for public services and social security for migrant workers and their children under the goal of urban population dispersion.

In the short term, the reform of the household registration system and the education system will not happen overnight, and the phenomenon of children returning will continue under the competitive situation of tight educational resources in large cities. Therefore, it is crucial to help children who have already or are about to “flow and left behind” to better integrate and adapt. First, the government needs to assist rural schools in receiving returning children. Schools not only need to help returning children adapt to the difference in teaching content through learning diagnosis, after-school tutoring, and textbook integration but also need to actively popularize “local knowledge” to returning children through school-based courses or daily cultural activities, helping them overcome obstacles such as dialect and customs. Second, teachers need to provide feedback on the psychological and interpersonal states of returning children through timely communication. Additionally, parents need to make more rational decisions on the issue of their children moving to the city and returning to the countryside. Parents who have the conditions can arrange for their children to return to schools in county towns around the working cities and seek the help of guardianship organizations, providing children with more “nearby” education support and growth care.

6. Limitations

The limitations of this research’s method are as follows. First, this research only selected one privately run school for migrant workers’ children in Beijing as the case study, and the findings cannot represent the general situation of privately run schools for migrant workers’ children in China but only illustrate the current problems of educational inequality and skill formation among floating rural students. Future research needs to be conducted on a larger scale of privately run schools for migrant workers’ children to reveal general conclusions. Second, case studies cannot provide causal conclusions. Future research needs to adopt more scientific quantitative survey methods to explore the impact of privately run schools for migrant workers’ children on the skill formation of floating rural students and to further compare the effectiveness of public and private schools as well as the differences in skill formation among floating rural students. Additionally, we will further use the data to verify the relevant conclusions in the future.

7. Conclusions

First, the academic achievement of the enrolling students at privately run schools for migrant workers’ children is not high. Most of these students are floating rural students from rural households and poor families. They have weak academic backgrounds and a lack of parental guidance and companionship.

Second, the learning mechanism of privately run schools for migrant workers’ children is not good. The school’s teacher level is not high, the teacher turnover rate is high, and the quality of characteristic courses is significantly lower than that of public schools.

Third, the main source of funds for privately run schools for migrant workers’ children is donations from social workers, which are dispersed and unstable, and the government’s investment in privately run schools for migrant workers’ children is insufficient.

Fourth, floating rural students in privately run schools for migrant workers’ children have poor graduation destinations, with a low percentage of students going on to key high schools, while some students are forced to become returning children, facing institutional barriers to upward mobility through education.

These aspects have led to education inequality and possible defects in the skill formation of floating rural students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.C. and X.L.; methodology, X.C.; writing—original draft preparation, X.C. and S.J.; writing—review and editing, X.C. and X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as we did not collect any information that could identify the participants during the data collection process. Therefore, according to the ethical review regulations, such research does not require ethical review.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study will be made available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Interview outline

For school leaders

- From the annual reports before 2016, we have learned about the basic information of the school, the sources of students and their situation after graduation, the composition of teachers, and some special activities held by the school. I would like to ask, in recent years, what are the major changes in these four aspects?

- Basic information (new school building’s rising costs, government subsidies)

- Where does your school recruit from? What are the criteria for admission? Do you know the further development of students after graduation? How many of the 80% of students who went on to general high school received higher education?

- As students generally come from migrant families, what specific measures have schools taken to establish a good home-school relationship and participate in students’ education?

- The principal once said that the school has accumulated a few good teachers in the development process; so, I want to ask how you recruited and attracted these teachers. We know that the total number of teachers has not changed very much over the years, how is their turnover and how do you motivate teachers to stay in the school for a long time? (Teachers’ salary structure, bonus performance, vocational training, etc.)

- How much subsidies do the government give to school each year, and has it always been so much? What are they probably used for?

- At present, we can only see the school’s information in 2016 from the internet and find that the school’s funding comes more from donations. You have also mentioned that the demand for funds is relatively large for a new building; so, I want to ask whether the structure of funding has changed in recent years. Can you introduce the source of funding (structural stability)? Affected by the epidemic, will there be a certain gap between this year’s donation and previous years? (Additionally, can you provide annual reports after 2016?)

For teachers

- Where are you from? How long have you been teaching at P Middle School? Why did you choose to be a teacher at P Middle School?

- In addition to the main teaching content, what special courses did you participate in? (Including life education, subject inquiry, differentiated instruction, and school-based curriculum, etc.) Can you introduce them in detail? How did you prepare? How about the effect and students’ feedback?

- We know that the school will provide teachers with the opportunity to participate in high-quality training. How does the school arrange teacher training, teacher research, and professional title evaluation during tenure? Are there differences among teachers at different stages of their professional development in these aspects, and what efforts have you made?

- We notice that there are many volunteers in the school, and some volunteers participate in fixed courses. Why do volunteers need to be involved in long-term teaching?

- Are there many students in your class receiving financial aid? How much is the subsidy? What is the standard of subsidy?

For students

- Where are you from? How long have you been in Beijing? Where did you go to elementary school? How did you get into P Middle School?

- What do you like most about school? For example, what are you satisfied with and what are you not satisfied with (the overall environment, the curriculum, and the relationship with teachers and students)?

- What has been your biggest change since you came to P Middle School?

- You usually have some extracurricular activities, such as interest groups, classroom extensions, and summer (winter) camps. What extracurricular activities have you participated in, what is the most impressive activity, and are there any additional gains to share? Will it affect your usual learning? (What do you do after dinner?) (What is the meaning of short-term volunteering for students?)

- Have you received a scholarship? (If so, when is it usually sent?) What kinds of students are generally awarded scholarships?

- Do you usually contact your parents as you board at school? Do parents know your performance in school? How long have your parents been in Beijing? What kind of work do they do?

For volunteers

- Why did you choose to volunteer at P Middle School?

- Can you comment on P Middle School? Did you have any special feelings during your volunteer service?

References

- MOE. Statistical Bulletin on National Educational Development in 2020. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_sjzl/sjzl_fztjgb/202108/t20210827_555004.html (accessed on 18 December 2022).

- Chen, Y.; Feng, S. Access to public schools and the education of migrant children in China. China Econ. Rev. 2013, 26, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Comparative study of life quality between migrant children and local students in small and medium-sized cities in China. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2018, 35, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, M.; Xu, J.; Lu, J.; Akezhuoli, H.; Wang, F. Health status and association with interpersonal relationships among Chinese children from urban migrant to rural left-behind. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 862219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, J. Educating migrant children: Negotiations between the state and civil society. China Q. 2004, 180, 1073–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodburn, C. Learning from migrant education: A case study of the schooling of rural migrant children in Beijing. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2009, 29, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Luo, Y. Social exclusion and the hidden curriculum: The schooling experiences of Chinese rural migrant children in an urban public school. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2016, 64, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yan, F.; Chen, Y. A floating dream: Urban upgrading, population control and migrant children’s education in Beijing. Environ. Urban. 2020, 33, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. Local adaptation of central policies: The policymaking and implementation of compulsory education for migrant children in China. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 2016, 17, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhao, X. How far is educational equality for China? Analysing the policy implementation of education for migrant children. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 2019, 18, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Li, H.; Zou, H.; Cross, W.; Bian, R.; Liu, Y. The mental health of children of migrant workers in Beijing: The protective role of public school attendance. Scand. J. Psychol. 2015, 56, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Yue, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhou, A. Choices or constraints: Education of migrant children in urban China. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2020, 39, 671–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, K.H.; Wong, Y.C.; Guo, Y. Transforming from economic power to soft power: Challenges for managing education for migrant workers’ children and human capital in Chinese cities. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2011, 31, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Chen, L.; Harrison, S.E.; Guo, H.; Li, X.; Lin, D. Peer victimization and depressive symptoms among rural-to-urban migrant children in China: The protective role of resilience. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H.; Walker, A. The education of migrant children in Shanghai: The battle for equity. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2015, 44, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. Educational expectations of parents and children: Findings from a case of China. Asian Soc. Work Policy Rev. 2014, 8, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, S. Quality of migrant schools in China: Evidence from a longitudinal study in Shanghai. J. Popul. Econ. 2017, 30, 1007–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, F.; Liu, C.; Luo, R.; Zhang, L.; Ma, X.; Bai, Y.; Sharbono, B.; Rozelle, S. The education of China’s migrant children: The missing link in China’s education system. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2014, 37, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Holland, T. In search of educational equity for the migrant children of Shanghai. Comp. Educ. 2011, 47, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, E. Teachers’ work in China’s migrant schools. Mod. China 2017, 43, 559–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Holmes, K.; Albright, J. Teachers’ perceptions of educational inclusion for migrant children in Chinese urban schools: A cohort study. Education and urban society. Educ. Urban Soc. 2020, 52, 649–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, A. Is there any chance to get ahead? Education aspirations and expectations of migrant families in China. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2012, 33, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Hou, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Du, X. Educational inequality and achievement disparity: An empirical study of migrant children in China. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 87, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Lu, S.; Huang, C. The psychological and behavioral outcomes of migrant and left-behind children in China. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2014, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhong, Y. Young floating population in city: How outsiderness influences self-esteem of rural-to-urban migrant children in China. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Su, S.; Li, X.; Tam, C.C.; Lin, D. Perceived discrimination, schooling arrangements and psychological adjustments of rural-to-urban migrant children in Beijing, China. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2014, 2, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Strain, school type, and delinquent behavior among migrant adolescents in China. Asian J. Criminol. 2021, 16, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Tsang, B.; Zhuang, L. Where have the migrant students gone after junior high school. China Econ. Educ. Rev. 2017, 2, 20–37. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. To comply or not to comply? Migrants’ responses to educational barriers in large cities in China. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2022, 63, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jacob, W.J. From access to quality: Migrant children’s education in urban China. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 2013, 12, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, M.H. Returning to no home: Educational remigration and displacement in rural China. Anthropol. Q. 2017, 90, 715–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodburn, C. Growing up in (and out of) Shenzhen: The longer-term impacts of rural-urban migration on education and labor market entry. China J. 2019, 83, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, H. Academic achievement and loneliness of migrant children in China: School segregation and segmented assimilation. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2013, 57, 85–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.; Pisano, G. The dynamic capabilities of firms: An introduction. Ind. Corp. Change 1994, 3, 537–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C. Educating rural migrant children in interior China: The promise and pitfall of low-fee private schools. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2020, 79, 102276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, A.; Ming, H.; Tsang, B. The doubly disadvantaged: How return migrant students fail to access and deploy capitals for academic success in rural schools. Sociology 2014, 48, 795–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Gao, W.; Chen, L. Does pre-service teacher preparation affect students’ academic performance? Evidence from China. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).