Abstract

Preadolescence is a critical period, characterised by changes in physical, hormonal, cognitive, behavioural, and emotional development, as well as by changes in social and school relationships. These changes are accompanied by the transition from elementary school to middle school. The literature shows that this transition is one of the most stressful events for preadolescents, which can have a negative impact on their well-being. The main objectives of this review, focused on the school context, were to identify protective and risk factors influencing the well-being of preadolescent students and to describe the interventions implemented. A systematic search of peer-reviewed papers published between 2011 and 2021 was conducted following the PRISMA reporting guidelines. A total of 36 full-text articles met the inclusion criteria. Studies converge in identifying risk factors that may affect student well-being in this age group: individual factors (levels of emotional awareness and self-esteem) and relational factors (friendship, teachers’ and parents’ supporting actions and roles). Intervention programs are mainly focused on improving emotional and social regulation skills that also influence academic achievement. Our findings have important implications for both research and intervention in school settings.

1. Introduction

Preadolescence is characterised by simultaneous changes in physical, hormonal, cognitive, behavioural, and emotional development, as well as by changes in social and school relationships [1]. These changes feature in the first transition preceding the adolescent period which involves challenges distinct from those of childhood and adolescence. Preadolescence, however, is not just a time of transition but deserves specific attention as a phase of life with all its specific characteristics. Preadolescence is proposed as a distinct period where changes that we observe more manifest in adolescence begin to take shape and begin to appear: a sense of internal decompensation and increased conflict in relationships, specifically, with peers and with parents [2]. The physical and hormonal changes are the first big changes in preadolescence, and they coincide with sexual maturation [2,3]. Physical development is evident in both sexes: girls are prone to breast development, hair grows in the pubic area and armpits, menstruation, height growth, and hormone changes can increase oil made by the skin that may cause acne; in boys, there are evident voice changes, the rapid growth of the trunk, hair growth in the pubic area, on the arms and legs and in armpits, and penis growth and the first involuntary erections [4]. Biological changes have important psychological and social impacts that influence preadolescents to accept themselves physically [5]. Changes that occur during puberty give rise to new emotional experiences such as a sense of insecurity or feeling nervous [6]. Additionally, the fluctuation of hormonal levels and brain development can affect mood and create mood swings and cause difficulties in emotional regulation: as a result, preadolescents show behavioural patterns such as parent–child conflicts, sensation seeking, and the development of romantic interests [7]. Preadolescence is, therefore, considered a period of vulnerability that increases the risk of the emergence of problems, above all in the relational and emotional field [8,9].

From the psychological point of view, this life season is characterised by the identification process, which means that preadolescents begin to identify with their peers and start to conflict with reference figures (parents and teachers)—comparison and identification with their reference group is the most important goal in this development period. The building of their individuality and identity starts from this stage of life [10]. Preadolescents live in an important conflict between the safety of the world of childhood and the drive to begin to create their own identity. Preadolescents start to redefine their relationship with their parents and begin to attach more importance to symmetric relationships than asymmetric ones [11,12].

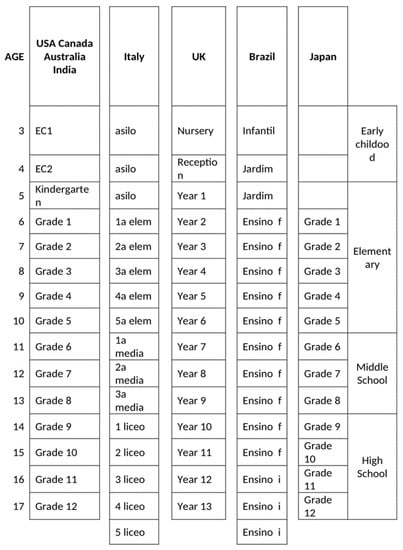

These changes in social relationships are accompanied by the transition from elementary school to middle school, almost everywhere in the world. Indeed, although school systems have different nomenclatures and classifications, it is agreed that there is a transition precisely in this age group. The different school systems of different nations refer to the same band and years of schooling even for different systems (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Different school systems classification.

This period of school plays a crucial role in educational development, transitions in the relational system both with peers and teachers, in the autonomy required, in the approach to study, etc.; students experience both a contextual change (schools) and a personal transition (puberty).

The extant literature shows that transition in middle school is one of the most stressful events for preadolescents that negatively impacts their self-concept, self-esteem, and academic achievement [13,14,15]. Eccles et al. [16] identified the typical middle school or junior high environment as developmentally inappropriate for preadolescents. The drastic switch in the school environment is difficult for most students to manage. As students attempt to negotiate the contextual change, an intense personal change often occurs with the beginning of puberty. These normative changes create important challenges for students during transition. In the new school scenario, sometimes the student’s history is not known, and it is difficult to get in touch with students; sometimes this is because the system does not provide transition support. There is also a transition in the class group, which must re-form and establish a new relationship and peer support system [14,17]. Roeser et al. [18] report that preadolescents’ perceptions of academic competence, the valuing of school, and emotional health are all important predictors of students’ grades, conduct in school, and the quality of their peer relationships. A recent review [19] examined findings concerning the impact of the primary to secondary education transition on both psychological and academic outcomes, and they noted that individual difference factors such as cognitive and emotional ability levels, gender, and socio-emotional skills can moderate the association between young adolescents’ academic motivation and engagement, self-concept, affect toward school, and their intrinsic interest in school; additionally, the review highlighted the importance of the social support received from parents, teachers, and peers in helping students to feel more secure and socially accepted during the transition experience.

Although preadolescence represents a very delicate period and one to which continuous attention must be paid, one of the problems is to identify the boundaries between preadolescence and adolescence development periods, and this has led to an underestimation of this phase, which has fluid and sometimes undefined boundaries. It is important to think about this age group because we can glimpse some precursors that may later develop into problem behaviours. Many papers about preadolescence even present a gap of about two years in indicating the beginning and end of preadolescence. As well as overlap and confusion about the target age group, this confusion about boundaries can also be seen in the nomenclature used, with some articles referring to childhood [20], others to early adolescence [21], pre-teens [22], to young adolescence [23], and others directly to adolescence [24]. The issues and characteristics related to preadolescence are not new in the literature; formerly, Blair and Burton [25] described the period of later childhood, dwelling on physical and intellectual transformations, on the influence of social context in this development, above all to give suggestions for parents in guidance. The variables that are intertwined in preadolescence and the complexity that characterises it led researchers to constantly question who preadolescents are, how they experience change, and what, if any, precursors need to be monitored and acted upon with preventive or supportive interventions.

For this reason, it is important to constantly analyse the most recent literature in this area so that we can grasp the speed of change in an ever-changing world, providing a framework that will aid researchers in evaluating new literature and give new directions for future research.

In this paper, we have conducted a systematic review concerning preadolescents with special reference to the middle school context.

The main objectives of this systematic review were: to identify individual and relational factors influencing the well-being of preadolescents in the school context; to identify specific protective and risk factors related to the school transition period; and to describe the interventions implemented in the middle school context.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

This study was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [26].

2.2. Research

PsycInfo, PsycArticles, Scopus, PubMed, and the Psychology & Behavioral Science Collection were searched systematically, using the following keywords: “preadolescence” AND (“psychology mental health” OR “wellbeing” OR “psychology risk factors*” OR “psychology protective factors”). We focused on peer-reviewed articles published from 2011 to 2021 inclusive. Results were limited to English, Italian, and German language peer-reviewed journal publications. Primary searches were completed in December 2021.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be included in this review, studies must have participants aged 9 to 14 recruited in the school setting; the administration of the protocols and any intervention programmes must have been delivered within the school setting.

Outcomes must be measured through quantitative and/or qualitative methods. Book chapters, dissertations, meta-analyses, reviews, comments, letters, editorials, and theoretical papers were excluded.

Studies were also excluded if they were: case studies; instrument validation; medicalfocus; socialfocus; biological/organic/genetic/neurological factors; articles with adult perspective on preadolescents; articles on sleep regulation; physiological factors and stress; and articles with borderline age range (over 9–14).

As regards school setting, studies were included if they: (i) considered emotional and social development; (ii) considered risk and protective factors related to mental health in preadolescents; (iii) evaluated the effects of intervention programmes that promote well-being in school; and (iv) treated transition problems.

2.4. Study Selection and Extraction Steps

All identified citations were imported into the bibliographic manager software Zotero 5.0 (Corporation for Digital Scholarship, Virginia, USA). Duplicates were identified and removed, after which, abstracts and titles were screened by three independent reviewers (SC, GL, and MLM) for eligibility. Discordant eligibility determinations were resolved by consensus.

The full texts of the eligible records were then obtained and screened for eligibility according to the exclusion criteria. Any doubts or conflicts were resolved by discussion between the three reviewers (SC, GL, and MLM) to reach a consensus.

2.5. Study Selection and Extraction Steps

Three independent reviewers (SC, GL, and MLM) created a data extraction standardised form in Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The first author, year of publication, number, gender and age of participants, study setting, variables, protocols, test, intervention programmes, and outcomes were extracted from each of the studies included. Any discrepancies in the extracted data were resolved by discussion between the four reviewers (SC, GL, NSB, and MLM) to reach a consensus.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selections and Extractions

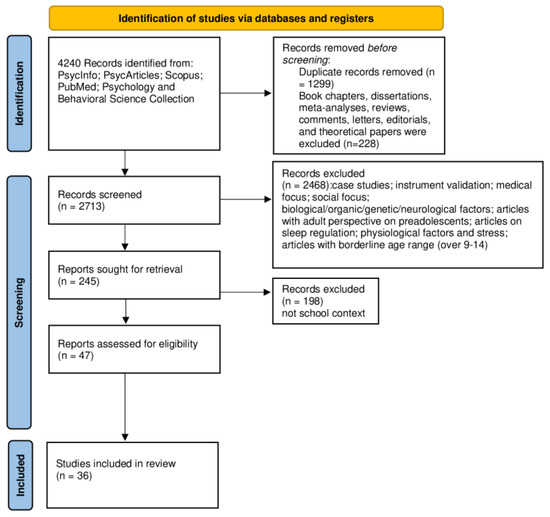

A total of 4240 abstracts were located of which 1527 were removed, being duplicates or not articles. A total of 2713 studies were screened against titles and abstracts. Subsequently, 2468 studies were excluded, principally because they did not fit the inclusion criteria and 47 studies were about school settings. A total of 36 studies finally met our inclusion criteria and, concerning the school context, were included (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

PRISMA Scheme.

3.2. Studies Characteristics

We summarized the key results of the study characteristics in Table 1 and Table S1 in the Supplementary Material.

Table 1.

Characteristics of publications included in review (N = 36).

The total of subjects in all selected studies was 35,669. Participants were all students attending the last year of primary school or middle school, while only one study of the longitudinal type considered the first year of secondary school.

Participants were principally students observed in the school context. The students considered had specific characteristics; in some cases, they present a disability (n = 3 studies).

Only a few studies (n = 9) used specific intervention programmes.

As regards methodology and study design, some of the selected studies used follow-up or a pre- and post-evaluation after intervention assessment (n = 15).

Most of the studies divided samples into subgroups (e.g., gender, separate conditions) (n = 24). Of these, ten studies have control groups or conditions and nine have reported results for control groups/conditions.

Only a few studies have selected conditions (n = 6) or subjects (n = 7) randomly. Thirteen used only validated measures, and five used only non-validated measures. No studies used a placebo condition.

4. Discussion

This systematic review focused on preadolescents’ age starting from the school context, looking to understand what kind of factors can be risky or protective in preadolescents attending middle school. What is immediately clear is the multitude of variables examined by the studies read and analysed. Although many studies used validated measures, only a few used rigorous methodological conditions such as control groups or conditions for comparison. Moreover, no studies used more than two control conditions, and only a few studies randomised subjects or conditions. For these reasons, results must be interpreted with caution.

It is important to reflect on some specific areas and focuses that require careful consideration, either to understand how to act preventively or to intervene. The findings on developing positive behaviours represent a common point among the papers examined. Promoting preadolescents’ well-being represents a complex challenge for parents, teachers, and the education world in general. Acting on preadolescence and individual and contextual variables is a key point to be able to help young people in their first outlook on life in an early form of autonomy and peer comparison. Preadolescents’ well-being is associated with many aspects of the relationship with parents, family, peers, friends, education, school, and academic performance.

Some of the main themes are presented in this review; the topics covered often intertwine and overlap, and the same study may present several themes at once. However, we found four principal kinds of factors: factors related to personal, cognitive, and individual aspects; factors related to relational aspects; factors related to the transition period to middle school; and factors related to support made by projects and programmes and specific figures such as teachers.

4.1. Aspects Related to Individual Factors

Individual factors such as personal and cognitive aspects can have a great influence on preadolescents’ lives and general well-being.

Long et al. [43] explore subjective well-being, given by frequent positive emotions, infrequent negative emotions, and a positive evaluation of life circumstances [57] looking to extend the model of social well-being to the specific context of youth and their schooling. They found a 4-factor model comprising positive emotions, negative emotions, fear-related negative emotions, and school satisfaction. An important function is represented by emotional awareness. The relationship between subjective well-being, emotional awareness, and emotional expression is confirmed by other studies [46]. Emotional awareness is also included in many programmes for students [15].

Among individual factors, as indicated by Coelho et al. [15] and Coelho and Souza [34], a crucial role is represented by self-esteem levels as predictors of well-being among students. Self-esteem is a factor to be monitored and enhanced, especially in the transition from childhood to adolescence. Preadolescents often face a decrease in their self-esteem, especially in the transition period.

Amado-Alonso et al. [27] concentrate on self-concept and self-representation. Self-concept is one of the most important outcomes of the processes of education and socialisation, and it is described as the perceptions that people have about themselves, formed through the interpretation of their own experience and of the environment, particularly influenced by significant others’ reinforcements and feedback, as well as by their own cognitive mechanisms [27]. Self-concept is a multidimensional construct which brings together academic, social, family, emotional, and physical dimensions [34]. In their study, Amado-Alonso et al. [27] underline this last dimension stating that organised sports practice could have a positive effect on self-concept in the preadolescent period.

Troop-Gordon et al. [54] state that significant mean-level decreases in academic and physical self-concepts occur from late childhood to preadolescence.

4.2. Aspects Related to Relational Factors

Children’s socialisation (above all between ages 6 and 12) is promoted because children not only develop in the family environment, but they also begin to get to know their peers, which allows them to relate to them through games, interactions, and so forth. Their participation in new situations and the link between affectivity and the environment will contribute to forming the child’s personality [34]. Many studies in this review focus on the advantages of socialisation for children and preadolescents. A body of literature identifies friendship as a protective factor in many areas of preadolescent life. In this period of life, a friendship develops and changes its balance, and its role becomes crucial for all the effects related to it, e.g., it can interfere with academic achievement and personal well-being [31], in particular, the authors show the results of the rapid changes in friendship patterns at the beginning of a school year.

Chen et al. [33] look to understand individual characteristics that may predict friendship quality during this developmental period, and they find that a hostile evaluation bias leads to a lower quality of friendship but only for girls. De la Haye et al. [36] concluded that overweight preadolescents have an elevated risk of psychosocial maladjustment when surrounded only by a small number of friendships.

Positive relational aspects have a fundamental role as a protective factor for preadolescents’ risk behaviours. This element is underlined in most of the papers’ focus on risks connected to bullying, which is extremely prevalent in this age group [35]. Victimisation experience, the other face of the bullying phenomenon, can lead to poor school engagement and high rumination levels and depressive symptoms [38]. Students in younger grades were bullied more often versus students from older grades; greater victimisation occurred in the lower grades, where peer relations and peer group structure play a more salient role [29]. Positive relational aspects among peers are fundamental to prevent all risks allied to victimisation in bullying behaviours [58].

Delgado et al. [37] found an interesting model that connects self-concept, academic goals, and the participation of the roles of victim, bully, and bystander in cyberbullying, showing how low scores in social self-concept and academic self-concept can explain cyber victimisation and the incidence of cyberbullying. Moreover, the authors reported that social self-concept with peers and learning goals can be protective factors against acting as a perpetrator.

A protective factor in this kind of risk is given also by teachers’ and parents’ supporting actions and roles [37,53]. Murray, Harvey, and Slee [45] found that a high level of stressful relationships and a low level of supportive relationships with family, teachers, and peers were associated with greater bullying, victimisation, and psychological health problems, as well as poorer social/emotional adjustment. In the preadolescent period, it is also sensible to provide education on the importance of relationships in life. Caprara et al. [32] underline the beneficial effects on preadolescents’ life of prosocial behaviours. The study by Layous et al. [42] shows that doing good to others leads to greater well-being and popularity. In their study, they demonstrate increased happiness and acceptance through prosocial activity. This has benefits for both the preadolescent and the community; well-liked preadolescents exhibit more inclusive and less externalising behaviour (e.g., less bullying) as adolescents. Other authors underline the importance of acting to promote inclusion and prevent racism or racial and ethnic disparities [45]. A fundamental role in the relationship’s foundations is played by classmates’ social support [46].

4.3. Factors Related to the Transition Period to Middle School

Some of the articles identified [15,24,44,55] dealt with the transition to “middle school”, while others focus on the transition to high school [44,55].

The results and reflections presented in these papers focus on some important concerns that students can manifest during school transition periods because, typically, the school transition involves simultaneous changes in life, the school environment, relationships, and academic expectations. The problems associated with transition are united by the fact that the student needs support and help to cope with a period full of changes. Coelho et al. [15] show that preadolescent students report lower levels of academic, emotional, and physical self-concept as well as lower levels of self-esteem by the end of fifth grade (1st year of U.S. middle school) compared to the fourth grade (last year of elementary school). As Coelho et al. [15], other research on this topic takes into account that this period of transition can present a decline in academic self and self-esteem attributed to individual and environmental factors; only Arens et al. [28] attribute this decline primarily to social and contextual factors. No gender differences are considered significant in all studies on transition considered in this review.

Makover et al. [44] focus on depression and anxiety symptoms and show, once again, the effectiveness of intervention programmes, in this case, aimed at students facing the transition from middle school to high school and, more specifically, from preadolescence to adolescence. The targeted intervention programme seems to reduce the escalation of depression, anxiety, and associated school difficulties in a group of U.S.A. at-risk youth transitioning from middle to high school. Results indicated that in comparison to the control condition, the group who followed the programme showed a small moderate effect for depression symptoms and a small effect size for anxiety symptoms.

This review takes into account two studies from Vaz [55,56] on the effects of the transition on the experiences of typically developing students or those with a disability, trying to understand the strengths and difficulties encountered by the two groups examined but also the influence of background. Individual student factors and primary school contextual factors are more important contributors in post-transition adjustment than concurrent secondary school contextual factors, and there exists a greater responsibility on primary schools to ensure that the transition needs of the disadvantaged groups are met satisfactorily.

Research from Vaz [55,56] allows us to reflect on how important it is to structure transition pathways that ensure continuity and consider all types of students.

4.4. Factors Related to Support Made by Projects and Programmes and Specific Figures Such as Teachers

This age group appears receptive and if accompanied by the right support preadolescents welcome the cues to be able to improve and grow. It is against this backdrop that programmes organised primarily in the school setting, with different goals of helping the pre-teen, assume great importance. For example, the purpose of many programmes is to improve social skills, which, in this age group, are precisely those that begin to be built with the skills of self-regulation, both emotional and social, which also influence academic achievement. An interesting and original study by Fairweather-Schmidt et al. [40] presents a programme to give preliminary support for the effectiveness of an intervention focused on reducing levels of perfectionism. This makes us reflect on the fact that there are so many factors related to well-being on which we can intervene early.

These interventions play a key role because they provide the preadolescent with attention, make them feel welcome, and are very often structured to ensure motivation for action, present and future. Such programmes, therefore, also aim to ensure support.

For example, through participation in a programme called the ‘‘Positive Transition’’, Coelho et al. [15] promote school adjustment in the transition to middle school referring to the achievement of higher levels of self-concept representation and self-esteem.

The quality of social support plays a crucial role in the development of preadolescents, including their self-concept, mental health, academic achievement, social development, and the risk of victimisation and bullying. In the school context and this age group, in addition to their parents and family context, key support is generated in the relationship with the teacher. Olivier and Archambault [48] state that the closeness with teachers and prosociality towards peers protect students displaying hyperactive or inattentive behaviours against behavioural, emotional, and cognitive disengagement throughout the school year.

5. Conclusions

From our review, we identified 36 articles published over a 10-year period. This leads us to reflect that perhaps more attention should be paid to the psychological aspects that characterise this stage of life as a specific age. Instead, we observed that this age is predominantly equated with childhood studies or adolescent studies. However, this age group deserves a great deal of attention, above all, because it allows for preventive actions to be taken both to identify risk factors and to address protective factors or growth factors to foster effective development or the strengthening of all those skills that can contribute to the individual’s well-being, both personal and social. In particular, from the analysis of the articles taken in account in this review, we have identified four factors which the research has prioritised: personal, cognitive, and individual; relational; transition period problems; and support made by projects and programmes and by specific figures such as teachers. In this age group, the self is forming, and the individual has yet to become autonomous and must learn how to relate to themselves and others. The purpose of much research is to identify factors on which preventive action can be taken to be able to curb or avoid problems related to the individual’s present and future well-being. To this end, the aim of research is to understand how to help the construction of the self, how to make sure that the preadolescent has a positive self-representation, and what can be the supporting figures and elements that can accompany them on this path of discovery and growth. Literature presents also many of the programmes created, for example, to improve social skills that precisely in this age group are those that begin to be built, and the skills of self-regulation, both emotional and social, also influence learning. The focus of other programmes is to contrast bullying and cyberbullying, phenomena which are increasing globally, specifically in recent years, and have dangerous impacts on students’ lives and are allied to some negative aspects, such as moral disengagement [59]. It is fundamental to support preadolescents above all in the school context. Some research shows that positive, warm, and supportive relationships between the teacher and student are critical for healthy and positive development, including in terms of academic achievement, social skills, and in countering bullying [60,61]. For example, sometimes student–teacher conflict, defined as a type of student–teacher interaction characterised by a perception of mutual discontent, disapproval, and unpredictability [62], can impact student life beyond schooling.

A topic considered is also school transition, always worthy of attention, in all age groups. Developmental changes and challenges in preadolescence provide a unique opportunity for society; problems related to transition, above all in this moment of preadolescents’ lives, highlight the need for society and the schools to organise classroom goals, tasks, and assignments, and promote collaboration and help among all students in such a way as to give school belongingness and continuity [44].

It is essential to understand who preadolescents are in order to identify the factors that promote well-being, especially in the school context where preadolescents spend most of their time. It is fundamental to provide valuable insights into whether educators and other professionals in the field should focus on addressing developmental issues related to puberty or on environmental and class climate issues related to the teaching and learning processes at secondary school during this critical stage of life transition.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/educsci13020130/s1. Table S1: Classification of publications included in review (N = 36).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.M., G.L. and S.C.; methodology, M.L.M., G.L., N.S.B., M.P.P. and S.C.; investigation, G.L.; data curation, M.L.M., G.L., N.S.B. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.M., G.L., N.S.B., M.P.P. and S.C.; writing—review and editing, M.L.M. and S.C.; supervision, S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rathi, N.; Rastogi, R. Meaning in Life and Psychological Well-Being in Pre-Adolescents and Adolescents. J. Indian Acad. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 33, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rogol, A.D.; Roemmich, J.N.; Clark, P.A. Growth at Puberty. J. Adolesc. Health 2002, 31, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorn, L.D.; Hostinar, C.E.; Susman, E.J.; Pervanidou, P. Conceptualizing puberty as a window of opportunity for impacting health and well-being across the life span. J. Res. Adolesc. 2019, 29, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delemarre-van de Waal, H.A. Regulation of puberty. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2002, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compian, L.J.; Gowen, L.K.; Hayward, C. The Interactive Effects of Puberty and Peer Victimization on Weight Concerns and Depression Symptoms Among Early Adolescent Girls. J. Early Adolesc. 2009, 29, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Iwanski, A. Emotion Regulation from Early Adolescence to Emerging Adulthood and Middle Adulthood: Age Differences, Gender Differences, and Emotion-Specific Developmental Variations. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2014, 38, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddings, A.-L.; Burnett Heyes, S.; Bird, G.; Viner, R.M.; Blakemore, S.-J. The Relationship between Puberty and Social Emotion Processing. Dev. Sci. 2012, 15, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas, F.; González-Carrasco, M. Subjective Well-Being Decreasing with Age: New Research on Children Over 8. Child Dev. 2019, 90, 375–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anniko, M.K.; Boersma, K.; Tillfors, M. Sources of Stress and Worry in the Development of Stress-Related Mental Health Problems: A Longitudinal Investigation from Early- to Mid-Adolescence. Anxiety Stress Coping 2019, 32, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erikson, E.H. The Life Cycle Completed; Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, S.M.; Ceballos, P.; Cartwright, A.; Quinn, C.; Walker, M. Parents of Preadolescents’ Experiences of Child–Parent Relationship Therapy. J. Child Adolesc. Couns. 2022, 8, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicognani, E.; Zani, B. Conflict Styles and Outcomes in Families with Adolescent Children. Soc. Dev. 2010, 19, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanobini, M.; Usai, M.C. Domain-Specific Self-Concept and Achievement Motivation in the Transition from Primary to Low Middle School. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 22, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, A.M. Transition to Middle School: Self Concept and Student Perceptions in Fourth and Fifth-Graders; Ball State University: Muncie, IN, USA, 2009; ISBN 1-109-57514-9. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, V.A.; Marchante, M.; Jimerson, S.R. Promoting a Positive Middle School Transition: A Randomized-Controlled Treatment Study Examining Self-Concept and Self-Esteem. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eccles, J.; Wigfield, A.; Harold, R.D.; Blumenfeld, P. Age and Gender Differences in Children’s Self- and Task Perceptions during Elementary School. Child Dev. 1993, 64, 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akos, P.; Martin, M. Transition Groups for Preparing Students for Middle School. J. Spec. Group Work 2003, 28, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeser, R.W.; Eccles, J.S.; Sameroff, A.J. School as a Context of Early Adolescents’ Academic and Social-Emotional Development: A Summary of Research Findings. Elem. Sch. J. 2000, 100, 443–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.; Borriello, G.A.; Field, A.P. A Review of the Academic and Psychological Impact of the Transition to Secondary Education. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmensen, L.; Jepsen, J.R.M.; van Os, J.; Blijd-Hoogewys, E.M.A.; Rimvall, M.K.; Olsen, E.M.; Rask, C.U.; Bartels-Velthuis, A.A.; Skovgaard, A.M.; Jeppesen, P. Are Theory of Mind and Bullying Separately Associated with Later Academic Performance among Preadolescents? Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 90, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.S.; Pan, P.M.; Manfro, G.G.; de Jesus Mari, J.; Miguel, E.C.; Bressan, R.A.; Rohde, L.A.; Salum, G.A. Independent and Interactive Associations of Temperament Dimensions with Educational Outcomes in Young Adolescents. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2020, 78, 101817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojio, Y.; Foo, J.C.; Usami, S.; Fuyama, T.; Ashikawa, M.; Ohnuma, K.; Oshima, N.; Ando, S.; Togo, F.; Sasaki, T. Effects of a School Teacher-Led 45-Minute Educational Program for Mental Health Literacy in Pre-Teens. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2019, 13, 984–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorsky, M.R.; Langberg, J.M.; Evans, S.W.; Becker, S.P. The Protective Effects of Social Factors on the Academic Functioning of Adolescents With ADHD. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2018, 47, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffhuser, K.; Allemand, M.; Schwarz, B. The Development of Self-Representations During the Transition to Early Adolescence: The Role of Gender, Puberty, and School Transition. J. Early Adolesc. 2017, 37, 774–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, A.W.; Burton, W.H. Growth and Development of the Preadolescent; Appleton-Century-Crofts: East Norwalk, CT, USA, 1951. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado-Alonso, D.; Mendo-Lázaro, S.; León-del-Barco, B.; Mirabel-Alviz, M.; Iglesias-Gallego, D. Multidimensional Self-Concept in Elementary Education: Sport Practice and Gender. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arens, A.K.; Yeung, A.S.; Craven, R.G.; Watermann, R.; Hasselhorn, M. Does the Timing of Transition Matter? Comparison of German Students’ Self-Perceptions before and after Transition to Secondary School. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2013, 57, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, A.; Feng, C.X.; Neudorf, C.; Alphonsus, K.B. Bullying Victimization among Preadolescents in a Community-Based Sample in Canada: A Latent Class Analysis. BMC Res. Notes 2020, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar-Schwartz, S.; Mishna, F.; Khoury-Kassabri, M. The Role of Classmates’ Social Support, Peer Victimization and Gender in Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors among Canadian Youth. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 2335–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baerveldt, C.; Bunt, G.G.; Vermande, M.M. Selection Patterns, Gender and Friendship Aim in Classroom Networks. Z. Erzieh. 2014, 17, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Kanacri, B.P.L.; Gerbino, M.; Zuffianò, A.; Alessandri, G.; Vecchio, G.; Caprara, E.; Pastorelli, C.; Bridglall, B. Positive Effects of Promoting Prosocial Behavior in Early Adolescence: Evidence from a School-Based Intervention. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2014, 38, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; McElwain, N.L.; Lansford, J.E. Interactive Contributions of Attribution Biases and Emotional Intensity to Child-Friend Interaction Quality During Preadolescence. Child Dev. 2019, 90, e114–e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, V.A.; Sousa, V. Comparing Two Low Middle School Social and Emotional Learning Program Formats: A Multilevel Effectiveness Study. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 656–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coyle, S.; Cipra, A.; Rueger, S.Y. Bullying Types and Roles in Early Adolescence: Latent Classes of Perpetrators and Victims. J. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 89, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Haye, K.; Dijkstra, J.K.; Lubbers, M.J.; Van Rijsewijk, L.; Stolk, R. The Dual Role of Friendship and Antipathy Relations in the Marginalization of Overweight Children in Their Peer Networks: The TRAILS Study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0178130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, B.; Escortell, R.; Martínez-Monteagudo, M.C.; Ferrández-Ferrer, A.; Sanmartín, R. Cyberbullying, Self-Concept and Academic Goals in Childhood. Span. J. Psychol. 2019, 22, E46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorio, N.B.; Secord Fredrick, S.; Demaray, M.K. School Engagement and the Role of Peer Victimization, Depressive Symptoms, and Rumination. J. Early Adolesc. 2019, 39, 962–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursley, L.; Betts, L. Exploring children’s perceptions of the perceived seriousness of disruptive classroom behaviours. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 35, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairweather-Schmidt, A.K.; Wade, T.D. Piloting a Perfectionism Intervention for Pre-Adolescent Children. Behav. Res. 2015, 73, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ickovics, J.R.; Carroll-Scott, A.; Peters, S.M.; Schwartz, M.; Gilstad-Hayden, K.; McCaslin, C. Health and academic achievement: Cumulative effects of health assets on standardized test scores among urban youth in the United States. J. Sch. Health 2014, 84, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layous, K.; Nelson, S.K.; Oberle, E.; Schonert-Reichl, K.A.; Lyubomirsky, S. Kindness Counts: Prompting Prosocial Behavior in Preadolescents Boosts Peer Acceptance and Well-Being. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, R.F.; Huebner, E.S.; Wedell, D.H.; Hills, K.J. Measuring School-Related Subjective Well-Being in Adolescents. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2012, 82, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makover, H.; Adrian, M.; Wilks, C.; Read, K.; Stoep, A.V.; McCauley, E. Indicated Prevention for Depression at the Transition to High School: Outcomes for Depression and Anxiety. Prev. Sci. 2019, 20, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.; Zvoch, K. Teacher-Student Relationships among Behaviorally at-Risk African American Youth from Low-Income Backgrounds: Student Perceptions, Teacher Perceptions, and Socioemotional Adjustment Correlates. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2011, 19, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitkowski, D.; Laakmann, M.; Petersen, R.; Petermann, U.; Petermann, F. Emotion Training with Students: An Effectiveness Study Concerning the Relation between Subjective Well-Being, Emotional Awareness, and Emotion Expression. Kindh. Und Entwickl. 2017, 26, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogurlu, Ü.; Sevgi-Yalın, H.; Yavuz-Birben, F. The relationship between social–emotional learning ability and perceived social support in gifted students. Gift. Educ. Int. 2018, 34, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, E.; Archambault, I. Hyperactivity, Inattention, and Student Engagement: The Protective Role of Relationships with Teachers and Peers. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2017, 59, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothon, C.; Head, J.; Klineberg, E.; Stansfeld, S. Can social support protect bullied adolescents from adverse outcomes? A prospective study on the effects of bullying on the educational achievement and mental health of adolescents at secondary schools in East London. J. Adolesc. 2011, 34, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusby, J.C.; Westling, E.; Crowley, R.; Light, J.M. Concurrent and predictive associations between early adolescent perceptions of peer affiliates and mood states collected in real time via ecological momentary assessment methodology. Psychol. Assess 2013, 25, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Ayala, C.M.; Gastélum-Cuadras, G.; Huéscar Hernández, E.; Núñez Enríquez, O.; Barrón Luján, J.C.; Moreno-Murcia, J.A. Individualism, Competitiveness, and Fear of Negative Evaluation in Pre-adolescents: Does the Teacher’s Controlling Style Matter? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 626786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.A.; Elliott, M.N.; Kanouse, D.E.; Wallander, J.L.; Tortolero, S.R.; Ratner, J.A.; Klein, D.J.; Cuccaro, P.M.; Davies, S.L.; Banspach, S.W. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities among Fifth-Graders in Three Cities. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomada, G.; De Domini, P.; Tonci, E.; Cherici, S.; Iannè, S. Gli Affetti a Scuola: La Relazione Alunnoinsegnante e Il Successo Scolastico Alla Fine Della Scuola Primaria = Affection in School: Student-Teacher Relationship at the End of Primary School and School Achievement. Psicol. Clin. Svilupp. 2015, 19, 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Troop-Gordon, W.; Frosch, C.A.; Wienke Totura, C.M.; Bailey, A.N.; Jackson, J.D.; Dvorak, R.D. Predicting the Development of Pro-Bullying Bystander Behavior: A Short-Term Longitudinal Analysis. J. Sch. Psychol. 2019, 77, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaz, S.; Parsons, R.; Falkmer, T.; Passmore, A.E.; Falkmer, M. The Impact of Personal Background and School Contextual Factors on Academic Competence and Mental Health Functioning across the Primary-Secondary School Transition. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaz, S.; Falkmer, M.; Ciccarelli, M.; Passmore, A.; Parsons, R.; Black, M.; Cuomo, B.; Tan, T.; Falkmer, T. Belongingness in Early Secondary School: Key Factors That Primary and Secondary Schools Need to Consider. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective Weil-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agus, M.; Mascia, M.L.; Zanetti, M.A.; Perrone, S.; Rollo, D.; Penna, M.P. Who Are the Victims of Cyberbullying? Preliminary Data towards Validation of “Cyberbullying Victim Questionnaire”. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2021, 13, ep310. [Google Scholar]

- Mascia, M.L.; Agus, M.; Zanetti, M.A.; Pedditzi, M.L.; Rollo, D.; Lasio, M.; Penna, M.P. Moral Disengagement, Empathy, and Cybervictim’s Representation as Predictive Factors of Cyberbullying among Italian Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C.; Prino, L.E.; Marengo, D.; Settanni, M. Student-teacher relationships as a protective factor for school adjustment during the transition from middle to high school. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C.; Badenes-Ribera, L.; Fabris, M.A.; Martinez, A.; McMahon, S.D. Prevalence of student violence against teachers: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Violence 2019, 9, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, D.; Jungert, T.; Iotti, N.O.; Settanni, M.; Thornberg, R.; Longobardi, C. Conflictual student–teacher relationship, emotional and behavioral problems, prosocial behavior, and their associations with bullies, victims, and bullies/victims. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 38, 1201–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).