Supported Open Learning and Decoloniality: Critical Reflections on Three Case Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Mentoring and Guidance: Learners may have access to mentors, tutors, or facilitators who provide guidance, answer questions, and offer personalised support. These mentors help learners set goals, develop learning plans, and navigate learning materials.

- Peer Collaboration: SOL often encourages community, collaboration, and interaction among learners. Peer networks and online communities can be established to foster collaboration, discussion, and knowledge sharing. Learners can engage in peer-to-peer learning, exchange feedback, and collaborate on projects or assignments.

- Learning Resources and Tools: SOL may provide learners with curated resources, learning materials, and tools that support their learning process. These resources could include textbooks, videos, interactive simulations, online quizzes, and more. Learners are guided to relevant and reliable resources to enhance their learning experience. Where applicable, OER fall under this category.

- Assessment and Feedback: SOL incorporates assessment and feedback mechanisms to evaluate learners’ progress and provide constructive feedback. This can be performed through self-assessment, peer assessment, or feedback from mentors. Regular feedback helps learners identify areas of improvement and adjust their learning strategies accordingly. Increasingly, analytics from virtual learning environments are used to support this process.

2. Materials and Methods

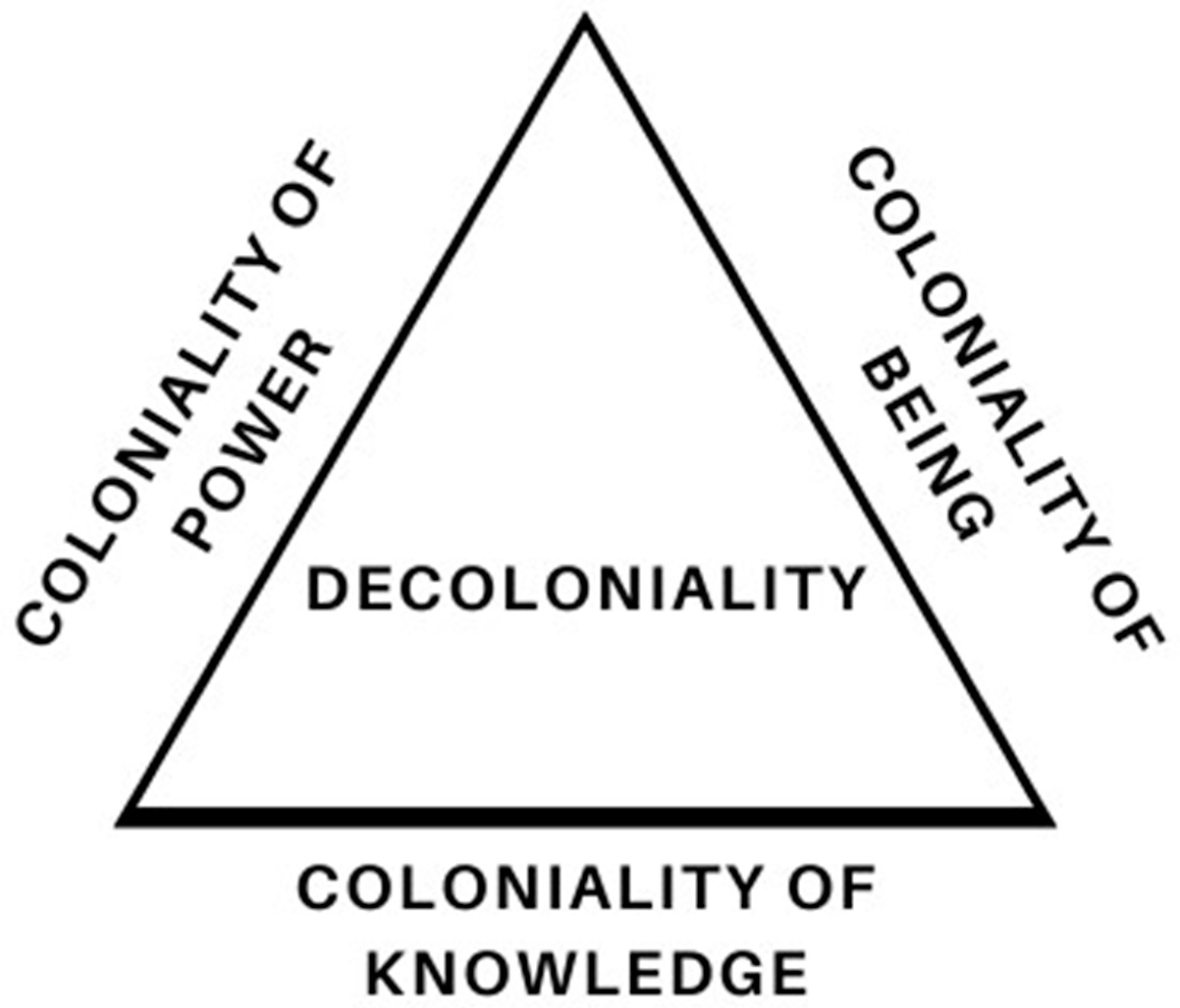

- Coloniality of Being: Coloniality of being refers to the ways in which colonialism has shaped and continues to shape individual and collective identities. It refers to the deep-seated psychological and ontological impacts of colonialism, including the construction of racial hierarchies, cultural inferiority/superiority, and the marginalisation of indigenous and non-Western ways of being. Coloniality of being encompasses the lasting effects on subjectivity, self-perception, and the ways individuals understand themselves and their place in the world [45].

- Coloniality of Power: Coloniality of power refers to the persistence of power structures and systems that perpetuate colonial relations and inequalities. It encompasses the economic, political, and social mechanisms that continue to uphold and reproduce colonial hierarchies and oppression. Coloniality of power is concerned with the ongoing subjugation of colonised peoples, the exploitation of resources, and the maintenance of systems that perpetuate racial, cultural, and socio-economic inequalities. Coloniality of power has a strong association with the epistemological foundations of colonialism [46,47,48,49].

- Coloniality of Knowledge: Coloniality of knowledge refers to the ways in which colonialism has influenced and continues to influence knowledge production, dissemination, and validation. It highlights the power dynamics embedded in knowledge systems, where Western epistemologies and ways of knowing are privileged, while indigenous and non-Western knowledge(s) are often devalued or marginalised. Coloniality of knowledge exposes how Western-centric knowledge has been imposed as universal and authoritative, erasing and suppressing other knowledge traditions and ways of understanding the world [50,51].

3. Results

3.1. Case Study 1: Pathways to Learning (Sub-Saharan Africa)

3.1.1. Background and Context

3.1.2. Key Goals, Activities, and Challenges

3.1.3. Outcome(s), Impact, and Evaluation

3.1.4. Reflections from the Perspective of Decoloniality

- Coloniality of Being

- Coloniality of Power

- Coloniality of Knowledge

3.2. Case Study 2: Transformation by Innovation in Distance Education (TIDE), Myanmar

3.2.1. Background and Context

3.2.2. Key Goals, Activities, and Challenges

3.2.3. Outcome(s), Impact, and Evaluation

3.2.4. Reflections from the Perspective of Decoloniality

- Coloniality of Being

- Coloniality of Power

- Coloniality of Knowledge

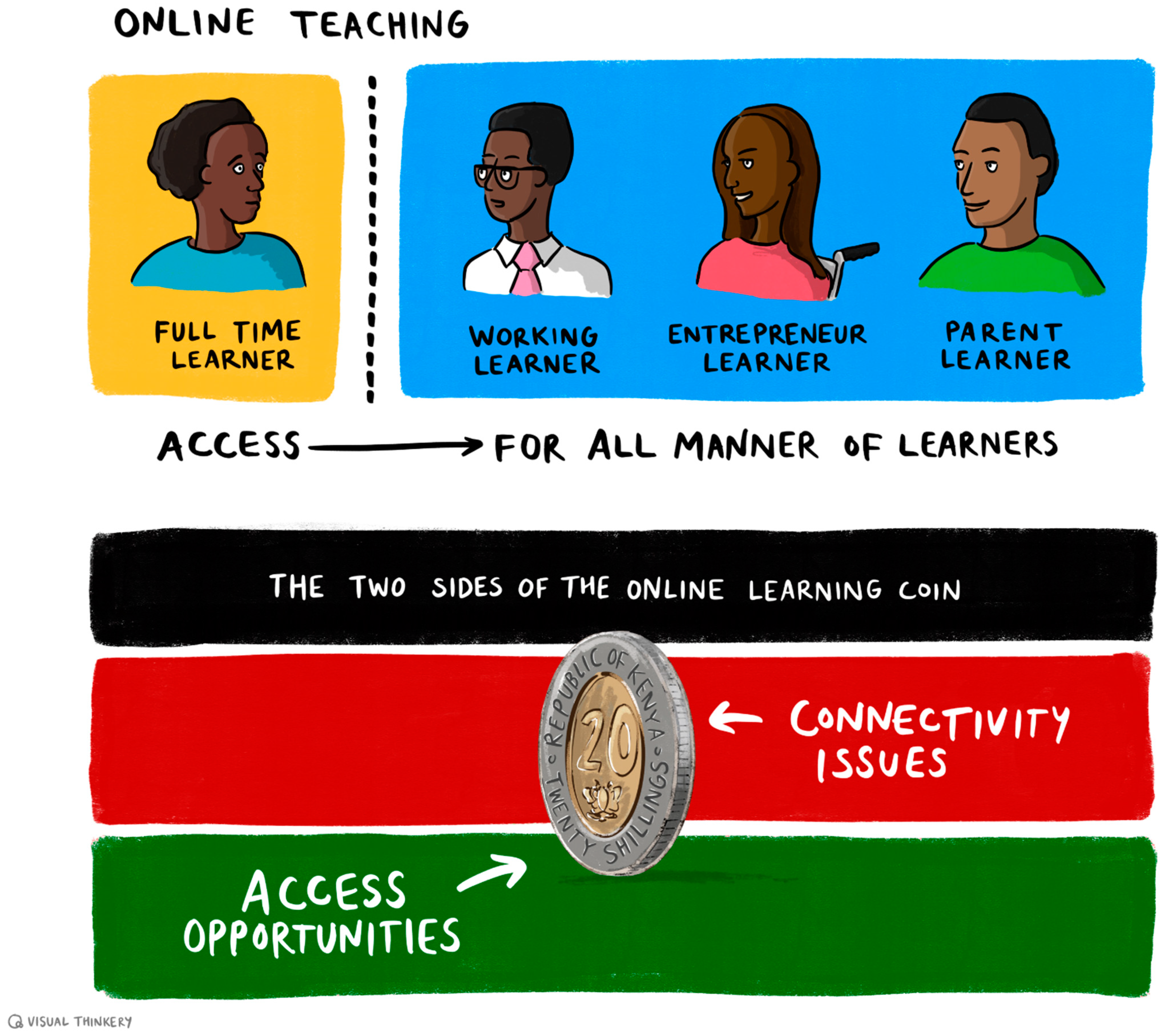

3.3. Case Study 3: Skills for Prosperity, Kenya

3.3.1. Background and Context

3.3.2. Key Goals, Activities, and Challenges

- Flexible scheduling with a self-paced delivery mode relying mostly on asynchronous activities to recognise participants’ needs and enable them to engage with the programme at their own pace, fitting study around work and other commitments.

- Offering downloadable content in multiple formats since accessing online content with unreliable Internet is difficult, learning materials were available in multiple formats that could be downloaded and accessed via a mobile to a tablet. This meant offering more control to participants over their learning as they could download learning resources at times when they had Internet access, and then work on them offline.

- Accessible learning material meaning all learning content met international accessibility standards (e.g., images and diagrams were accompanied by alternative text for screen readers) to support participants with special learning needs and to be as inclusive and accommodating as possible.

- Distributed award system where a distributed award system of specialised digital badges (e.g., Online Assessment Badge; Learning Design Badge) and a certificate of completion was considered to motivate and encourage participation and to meet recognition expectations.

- Local support: In addition to the UK-based technical and academic teams, an online community of practice, a dedicated mailbox for individualised learner support, and a Kenyan coordinator dealt with inquiries and tasks that could not be addressed remotely. As well as dealing with local issues, the coordinator identified cultural and contextual factors that might otherwise have limited accessibility, inclusion, and diversity.

3.3.3. Outcome(s), Impact, and Evaluation

3.3.4. Reflections from the Perspective of Decoloniality

- Coloniality of Being

- Coloniality of Power

- Coloniality of Knowledge

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stracke, C.M.; Sharma, R.C.; Bozkurt, A.; Burgos, D.; Swiatek Cassafieres, C.; Inamorato dos Santos, A.; Mason, J.; Ossiannilsson, E.; Santos-Hermosa, G.; Shon, J.G.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 on Formal Education: An International Review of Practices and Potentials of Open Education at a Distance. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2022, 23, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.; Jung, I.; Xiao, J.; Vladimirschi, V.; Schuwer, R.; Egorov, G.; Lambert, S.R.; Al-Freih, M.; Pete, J.; Olcott, D., Jr.; et al. A global outlook to the interruption of education due to COVID-19 pandemic: Navigating in a time of uncertainty and crisis. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2020, 15, 1–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. Pedagogy of the Oppressed; Continuum Books: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. Preparing teachers for diverse student populations: A critical race theory perspective. J. Teach. Educ. 1999, 50, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.; Luckett, K.; Misiaszek, G. Possibilities and complexities of decolonising higher education: Critical perspectives on praxis. Teach. High. Educ. 2021, 26, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adefila, A.; Teixeira, R.V.; Morini, L.; Texeira Garcia, M.L.; Delboni, T.M.Z.G.F.; Spolander, G.; Khalil-Babatunde, M. Higher education decolonisation: Whose voices and their geographical locations? Glob. Soc. Educ. 2022, 20, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, J.; Dlamini, M.; Anonymous. Scaling Decolonial Consciousness?: The Reinvention of ‘Africa’ in a Neoliberal University. In Decolonisation in Universities; Jansen, J.D., Ed.; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019; pp. 116–135, JSTOR; Available online: www.jstor.org/stable/10.18772/22019083351.11 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Jansen, J. Decolonisation in Universities: The Politics of Knowledge; Wits University Press: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2019; JSTOR; Available online: www.jstor.org/stable/10.18772/22019083351 (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- McGregor, R.; Park, M.S. Towards a deconstructed curriculum: Rethinking higher education in the Global North. Teach. High. Educ. 2019, 24, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimpenny, K.; Beelen, J.; Hendrix, K.; King, V.; Sjoer, E. Curriculum Internationalization and the ‘Decolonizing Academic’. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2022, 41, 2490–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illich, I. Deschooling Society; Marion Boyars: London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfi, H.E. Decolonising the science curriculum in England: Bringing decolonial science and technology studies to secondary education. Curric. J. 2021, 32, 510–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, F. Decolonizing development education and the pursuit of social justice. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, J.; Guthadjaka, K. Indigenous Authorship on Open and Digital Platforms: Social Justice Processes and Potential. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2020, 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossu, C.; Pete, J.; Prinsloo, P.; Agbu, J.F. How to tame a dragon: Scoping diversity, inclusion and equity in the context of an OER project. Pan-Commonwealth Forum 9 (PCF9). 2019. Available online: http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/3349 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Hodgkinson-Williams, C.A.; Trotter, H. A Social Justice Framework for Understanding Open Educational Resources and Practices in the Global South. J. Learn. Dev. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.R. Changing our (Dis)Course: A Distinctive Social Justice Aligned Definition of Open Education. J. Learn. Dev. 2018, 5, 225–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivory, C.J.; Pashia, A. Using Open Educational Resources to Promote Social Justice. Association of College and Research Libraries. 2022. Available online: https://www.ala.org/acrl/sites/ala.org.acrl/files/content/publications/booksanddigitalresources/digital/9780838936771_OA.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Bali, M.; Cronin, C.; Jhangiani, R.S. Framing Open Educational Practices from a Social Justice Perspective. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2020, 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traxler, J. Using OER In Asia: Factors, reforms and possibilities. Asian J. Distance Educ. 2018, 13, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Crissinger, S. A Critical Take on OER Practices: Interrogating Commercialization, Colonialism, and Content. In the Library with the Lead Pipe. 2015. Available online: http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2015/a-critical-take-on-oer-practices-interrogating-commercialization-colonialism-and-content/ (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Watters, A. Ed-tech’s Inequalities. 2015. Available online: https://hackeducation.com/2015/04/08/inequalities (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Farrow, R. Open education and critical pedagogy. Learn. Media Technol. 2017, 42, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaeminck, S.; Podkrajac, F. Journals in Economic Sciences: Paying Lip Service to Reproducible Research? Paying Lip Service to Reproducible Research? IASSIST Q. 2022, 41, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lee, K. Who opens online distance education, to whom, and for what? A critical literature review on open educational practices. Distance Educ. 2020, 41, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Lane, A. From teaching to learning: Technological potential and sustainable, supported open learning. Syst. Pract. Action Res. 1998, 11, 629–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, R. Supported open learning and the emergence of learning communities. The case of the Open University UK. In Creating Learning Communities. Models, Resources, and New Ways of Thinking about Teaching and Learning; Miller, R., Ed.; Foundations of Holistic Education Series (1); Foundation for Educational Renewal, Inc.: Brandon, VT, USA, 2000; pp. 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew, P.; Weller, M. Applying Learning Design to Supported Open Learning. In Learning Design; Koper, R., Tattersall, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- TESSA. How the Network Developed. Teacher Education in Sub-Saharan Africa (TESSA). 2021. Available online: https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/index.php?categoryid=579 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Hutchinson, S.; Wolfenden, F. A new paradigm for teacher education: Supported, open teaching and learning at the Open University. In Proceedings of the European Educational Research Association Annual Conference, Geneva, Switzerland, 13–16 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T. New Ways of Mediating Learning: Investigating the implications of adopting open educational resources for tertiary education at an institution in the United Kingdom as compared to one in South Africa. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2008, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wolfenden, F. TESS-India OER: Collaborative practices to improve teacher education. Indian J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 1, 33–48. Available online: http://ncte-india.org/ncte_new/?page_id=1703 (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Bucker, A.; Perryman, L.-A.; Seal, T.; Musafir, S. The role of OER localisation in building a knowledge partnership for development: Insights from the TESSA and TESS-India teacher education projects. Open Prax. 2014, 6, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, C.; Nix, I. Supported open learning: Developing an integrated information literacy strategy online. In Teaching Information Literacy Online; Mackey, T.P., Jacobson, T.E., Eds.; Neal Schuman: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 91–108. Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/27434/ (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Pitt, R.; Ebrahimi, N.; McAndrew, P.; Coughlan, T. Assessing OER impact across varied organisations and learners: Experiences from the bridge to success initiative. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2013, 2013, 17. Available online: https://jime.open.ac.uk/articles/10.5334/2013-17 (accessed on 1 January 2020). [CrossRef]

- Farrow, R. Bringing Learning to Life: Evaluation of Everyday Skills in maths and English. Open Education Research Hub. The Open University (UK). CC-BY 4.0. 2019. Available online: http://oro.open.ac.uk/67478/ (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Coughlan, T.; Pitt, R.; Farrow, R. Forms of innovation inspired by open educational resources: A post-project analysis. Open Learn. J. Open Distance Learn. 2019, 34, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, A. Situating decolonial strategies within methodologies-in/as-practices: A critical appraisal. Sociol. Rev. 2023, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravitch, S.M.; Riggan, M. Reason & Rigor: How Conceptual Frameworks Guide Research, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moosavi, L. Turning the Decolonial Gaze towards Ourselves: Decolonising the Curriculum and ‘Decolonial Reflexivity’ in Sociology and Social Theory. Sociology 2023, 57, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silova, I.; Millei, Z.; Piattoeva, N. Interrupting the Coloniality of Knowledge Production in Comparative Education: Postsocialist and Postcolonial Dialogues after the Cold War. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2017, 61, S74–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Torres, N. Césaire’s Gift and the Decolonial Turn. In Critical Ethnic Studies: A Reader; Elia, N., Hernández, D.M., Kim, J., Redmond, S.L., Rodríguez, D., Echavez, S., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mfinanga, F.A.; Mrosso, R.M.; Bishibura, S. Comparing case study and grounded theory as qualitative research approaches. Int. J. Latest Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci. (IJLRHSS) 2019, 2, 51–56. Available online: http://www.ijlrhss.com/paper/volume-2-issue-5/5-HSS-366.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S.J. Coloniality of Power in Postcolonial Africa. Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa: Dakar, Senegal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Torres, N. The topology of being and the geopolitics of knowledge. City 2004, 8, 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosfoguel, R. Colonial Difference, Geopolitics of Knowledge, and Global Coloniality in the Modern/Colonial Capitalist World-System. Rev. (Fernand Braudel Cent.) 2002, 25, 203–224. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40241548 (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Grosfoguel, R. The Epistemic Decolonial Turn. Cult. Stud. 2007, 21, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignolo, W. Introduction: Coloniality of Power and de-Colonial Thinking. Cult. Stud. 2007, 21, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavala, M. Decolonial Methodologies in Education. In Encyclopedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory; Peters, M., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quijano, A. Coloniality of Power and Eurocentrism in Latin America. Int. Sociol. 2000, 15, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, M. Coloniality of Knowledge and the Challenge of Creating African Futures. Ufahamu A J. Afr. Stud. 2018, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanon, F. Black Skin, White Masks; Grove Press: New York, NY, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan, T.; Goshtasbpour, F.; Mwoma, T.; Makoe, M.; Tanglang, N.; Bonney, S.; Aubrey-Smith, F.; Biard, O. Digital Decision: Understanding and Supporting Key Choices in Online and Blended Teaching in Sub-Saharan Africa; The Open University: Milton Keynes, UK, 2021; Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/78705/8/78705VOR.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Coughlan, T.; Goshtasbpour, F.; Mwoma, T.; Makoe, M.; Tanglang, N.; Bonney, S.; Biard, O. Making Digital Decisions: A Guide for Harnessing the Potential of Online Learning and Digital Technologies; The Open University: Milton Keynes, UK, 2021; Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/78706/1/Making_Digital_Decisions.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Coughlan, T.; Goshtasbpour, F.; Mwoma, T.; Makoe, M.; Aubrey-Smith, F.; Tanglang, N. Decision Making in Shifts to Online Teaching: Analysing Reflective Narratives from Staff Working in African Higher Educational Institutions. Trends High. Educ. 2023, 2, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, R.; Adams, A.; Bushesha, M.; Biard, O.; Coughlan, T.; Cross, S.; Edwards, C.; Foster, M.; Ebubedike, M.; Herodotou, C.; et al. Pathways to Learning: International Collaboration Under COVID-19. Open Education Global 2021. Université de Nantes, France. 2021. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/robertfarrow/pathways-to-learning-international-collaboration-under-covid19-250318896 (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Coughlan, T. Pathways for Learning: Project Report. Unpublished Manuscript. Institute of Educational Technology; The Open University: Milton Keynes, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Goshtasbpour, F.; Ferguson, R.; Pitt, R.; Cross, S.; Whitelock, D. Adapting OER: Addressing the Challenges of Reuse When Designing for HE Capacity Development. In Proceedings of the 21st European Conference on e-Learning (ECEL), Brighton, UK, 27–28 October 2022; Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/84928/3/84928.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Goshtasbpour, B.; Pitt, B.; Cross, S.; Ferguson, R.; Whitelock, D. Challenges for innovation and educational change in digital education in low-resourced settings: A Kenyan example. In Proceedings of the EDEN 2023 Annual Conference, Dublin, Republic of Ireland, 18–20 June 2023; Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/89316/ (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Goshtasbpour, F.; Pitt, B. Skills for Prosperity: Using OER to Support Nationwide Change in Kenya. OER 2023, Inverness, Scotland. 2023. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/BeckPitt/skills-for-prosperity-using-oer-to-support-nationwide-change-in-kenya (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Gregson, J.; Lane, A.; Foster, M. Adaptive Project Design: Early insights from working on the transformation of the Distance Education System in Myanmar. In Proceedings of the Pan-Commonwealth Forum 9 (PCF9), Edinburgh, Scotland, 9–12 September 2019; Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/66720/3/66720.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Gregson, J.; Pitt, R.; Seal, T. Developing a Digital Strategy for Distance Education in Myanmar. In Pan-Commonwealth Forum 9 (PCF9). Commonwealth of Learning. 2019. Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/66351/10/Developing%20a%20Digital%20Strategy%20for%20Distance%20Education%20in%20Myanmar%20by%20Jon%20Gregson%20V2%20June21.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Gregson, J.; Pitt, R.; Seal, T. TIDE Digital Strategy Report. Transformation by Innovation in Distance Education (TIDE), Milton Keynes. 2020. Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/73219/15/Digital%20Strategy%202020%20v2.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Goshtasbpour, F.; Pitt, B. Skills for Prosperity, Kenya: Repurposing OER to Deliver a Large-Scale National Professional Development Training. OER22. 2022. Available online: https://youtu.be/8PIIar_MBLA (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Lane, A.; Gregson, J. Fostering innovations in pedagogical practices: Transforming distance education through a professional development programme using OERs. In Proceedings of the Pan Commonwealth Forum 9 (PCF9), Edinburgh, Scotland, 9–12 September 2019; Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/66721/3/66721.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- OpenLearn. Take Your Teaching Online. 2022. Available online: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/education-development/education/take-your-teaching-online (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- OpenLearn. Making Teacher Education Relevant for 21st Century Africa. Available online: https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/view.php?id=2745 (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- SPHEIR. Strategic Partnerships for Higher Education Innovation and Reform. 2020. Available online: https://www.spheir.org.uk/about (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Eckstein, D.; Künzel, V.; Schäfer, L. Global Climate Risk Index 2021: Who Suffers Most from Extreme Weather Events? Weather-Related Loss Events in 2019 and 2000–2019. Germanwatch. 2021. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-climate-risk-index-2021 (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- SPHEIR (n.d.) Transformation by Innovation in Distance Education (TIDE). Available online: https://www.spheir.org.uk/partnership-profiles/transformation-innovation-distance-education (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Lall, M. Myanmar’s Education Reforms: A Pathway to Social Justice? UCL Press: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, A. Transformation by Innovation in Distance Education (TIDE) Summative Evaluation Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.spheir.org.uk/sites/default/files/tide_summative_evaluation_report_fv-final_clarification_.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- The Government of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Education. National Education Strategic Plan 2016-21. 2016. Available online: https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/myanmar_national_education_strategic_plan_2016-21.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- OpenLearnCreate (n.d.). TIDE Collection. Available online: https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/index.php?categoryid=479 (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- SPHEIR (n.d.). Advancing Environmental Science in Myanmar via Distance Learning-Transformation by Innovation in Distance Education. Available online: https://www.spheir.org.uk/sites/default/files/tide_project_overview_final.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Fink, C. Living Silence in Burma: Surviving Under Military Rule, 2nd ed.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chinlone Project Myanmar’s Higher Education Reform: Which Way Forward? 2018. Available online: https://site.unibo.it/chinlone/it/report (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Foreign, Commonwealth Development Office. Development Tracker: Skills for Prosperity Programme. 2022. Available online: https://devtracker.fcdo.gov.uk/projects/GB-GOV-1-300310/summary (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Institute of Educational Technology (n.d.). Skills for Prosperity Kenya. Available online: https://iet.open.ac.uk/projects/skills-for-prosperity-kenya (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- JISC. Digital Capabilities Framework. 2015. Available online: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/rd/projects/building-digital-capability (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- FutureLearn (n.d.) Online Teaching: Creating Courses for Adult Learners. Available online: https://www.futurelearn.com/microcredentials/online-teaching (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- SFPK (n.d.). Skills For Prosperity Kenya Capacity Building Projects. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLZyHpGS20Ejo3ddA-cS7C1L4HE2QWQcM2 (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- King, F. Evaluating the impact of teacher professional development: An evidence-based framework. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2014, 40, 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. County Statistical Abstract. 2021. Available online: https://www.knbs.or.ke/publications (accessed on 26 May 2023).

- Giroux, H. Critical Pedagogy. In Handbuch Bildungs- und Erziehungssoziologie; Bauer, U., Bittlingmayer, U.H., Scherr, A., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, S.M.; Stommel, J. If Freire Made a MOOC: Open Education as Resistance. Open Education 2014. Hilton Crystal City, Arlington, Virginia, USA. 2014. Available online: https://hybridpedagogy.org/freire-made-mooc-open-education-resistance/ (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Amano, T.; Ramírez-Castañeda, V.; Berdejo-Espinola, V.; Borokini, I.; Chowdhury, S.; Golivets, M.; González-Trujillo, J.D.; Montaño-Centellas, F.; Paudel, K.; White, R.L.; et al. The manifold costs of being a non-native English speaker in science. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusbaum, A.T. Who Gets to Wield Academic Mjolnir? On Worthiness, Knowledge Curation, and Using the Power of the People to Diversify OER. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2020, 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, T. Between Social Justice and Decolonisation: Exploring South African MOOC Designers’ Conceptualisations and Approaches to Addressing Injustices. J. Interact. Media Educ. 2020, 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Online Education (Stage 1) Baseline Capacity Development | Digital Education (Stage 2) Mastery Capacity Development |

|---|---|

|

|

| Decoloniality | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Being | Power | Knowledge | |

| Supported |

|

|

|

| Open |

|

|

|

| Learning |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Farrow, R.; Coughlan, T.; Goshtasbpour, F.; Pitt, B. Supported Open Learning and Decoloniality: Critical Reflections on Three Case Studies. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111115

Farrow R, Coughlan T, Goshtasbpour F, Pitt B. Supported Open Learning and Decoloniality: Critical Reflections on Three Case Studies. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(11):1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111115

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarrow, Robert, Tim Coughlan, Fereshte Goshtasbpour, and Beck Pitt. 2023. "Supported Open Learning and Decoloniality: Critical Reflections on Three Case Studies" Education Sciences 13, no. 11: 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111115

APA StyleFarrow, R., Coughlan, T., Goshtasbpour, F., & Pitt, B. (2023). Supported Open Learning and Decoloniality: Critical Reflections on Three Case Studies. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111115