2. Materials and Methods

In this study, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA,

http://www.prisma-statement.org/ accessed on 4 May 2021) (identifier registration number: DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/3J7VM) [

30] method was implemented, building on the original Quality of Reporting of Meta-Analyses (QUOROM) guide for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRIMA checklist can be found in the

Supplementary Material). A systematic literature review is a process of collecting and analysing data in aggregate that is conducted after establishing prior selection criteria, the aim being to answer a set of research questions posed around a hot topic or with a high number of publications. This systematic review applies the PRISMA 2020 standards [

31,

32] to identify eligibility criteria, information sources, search strategies, selection processes, data collection process and data list presentation. The systematic review process that has been conducted consists of different phases [

31]:

Phase 1: Research questions (RQs). They were organised around four dimensions or areas, as shown in

Table 1: (1) the documentary dimension (RQ1–RQ3), which aimed to identify the areas of knowledge to research on the topic, including the geographical origin of the researchers and the impact of their productions; (2) the methodological dimension (RQ4), which addresses the research approaches and methods applied; (3) the video game dimension (RQ5–RQ8), which aims to define the aspects associated with the technology and game tools used; and (4) the cultural dimension (RQ9–RQ12), to analyse the intrinsic cultural aspects of the video game and the impact of this medium on the transmission of culture.

Phase 2: Eligibility criteria and sources of information. The documentary sources used are from articles published in indexed scientific journals published during the period 2004–2022, which are the dates of the first and last inclusion in the first search. These documents and their searches include the following Unesco Thesaurus terms: video games, culture and subculture. The terms have been adapted and are not the same as those used in the database search because the novelty of this research means that some terms are not yet established or are synonymous with computer games—video games. Empirical studies with quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods were included. Exclusion criteria were applied to articles whose main theme was not culture and the relationship between culture and video games as an impact on cultural development.

Phase 3: Search strategies. The WOS and SCOPUS databases were used for the selection of scientific articles. Both are recognised as specialised databases in scientific research and have the support and recognition of the international scientific community. The search terms used were as follows: Video games, Computer Games, Culture and Subculture.

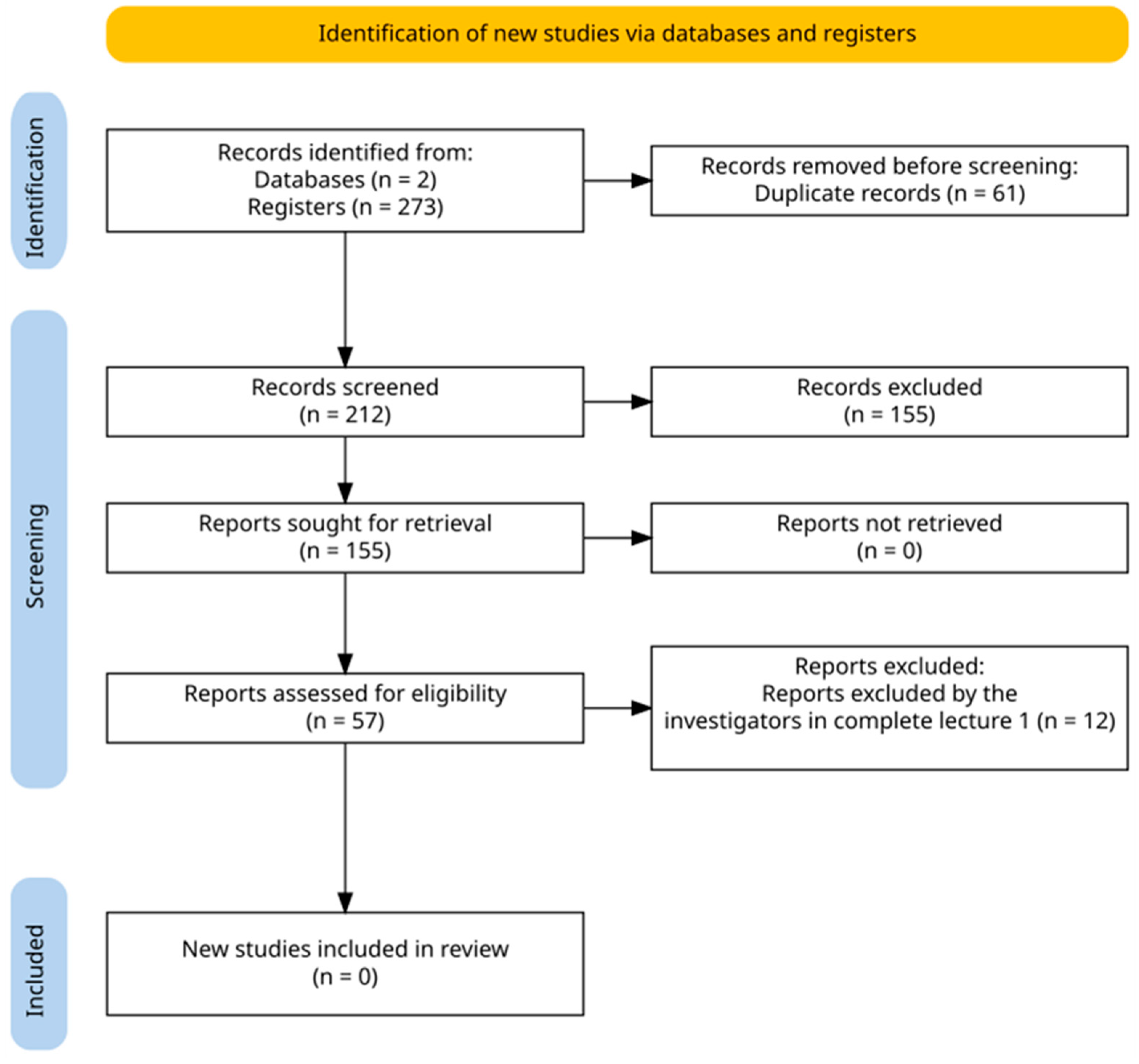

Phase 4: Study selection process. The initial search yielded 273 articles, of which 61 were duplicates. Thus, 212 articles were analysed on the basis of the title and abstract; the process is based on inclusion–exclusion criteria to agree on the final exclusion of a total of 155 articles. The remaining 57 articles were analysed independently and in their entirety, which led to the exclusion of a further 12 articles by prior agreement. Thus, the final sample of documents for the systematic review was composed of 45 articles. To facilitate this transcription, it was possible to use a flow chart developed according to the indications of the PRISMA 2020 Protocol, which was later specified by numerous authors [

31,

33]. Our diagram is shown in

Figure 1.

Phase 5: Data coding and synthesis. The Zotero bibliographic manager was used for data collection and compilation. The synthesis of information was carried out using a coding sheet with 33 fields (Excel). These were divided in relation to the following aspects: identification of the document according to authorship, date of publication, title, journal, etc. Fields relating to the methodological area were also included: subject, type and methodology of the study; next, we studied the conceptualization of the video–ludic aspect: the type of game, form of introduction and technology or video game used; and finally, we analysed the thematic or cultural perspective investigated, the cultural approach made and the results stated by each work of research. The researchers first analysed independently and then by consensus for the different phases of selection, according to the criteria agreed prior to the completion of the review.

3. Results

The results of this study are organised around the research questions set out in

Table 1. These questions allowed the studies to be categorised and differentiated for analysis and are, therefore, the most explicit way of presenting the research results.

3.1. RQ1. What Is the Conceptual Network Extracted from the Literature, and What Are the Topics of the Articles according to the Journal Category in the Databases?

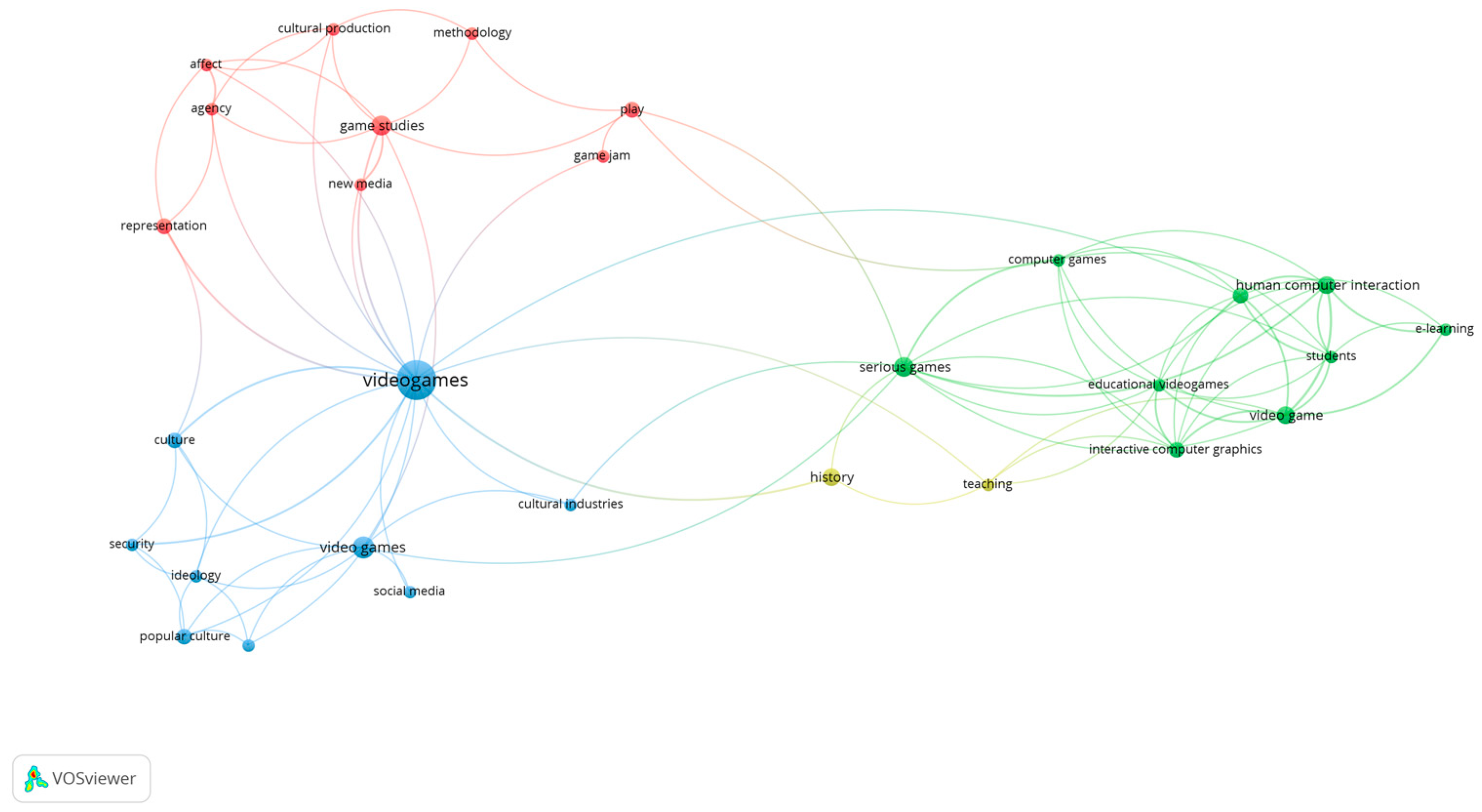

In the analysis of the conceptual network, we obtained a series of clusters generated by the co-occurrence of keywords in the articles and selected in the final phase. This co-occurrence was organised around a number of two keywords, as shown in

Figure 2. The first cluster (nine items) in red exposes a conceptual network around game studies and its main development environments, finds connections with new media, and affects the reproduction of culture or game jams. The second cluster, also (nine items) in blue, shows the general connections between video games, the media and the channels used in their interrelation with culture, which is, in fact, the cluster that most diversifies its connections, as these extend from the educational world to the creation of learning communities and video game designers.

The third cluster, in green, is related to serious games and particularly to the educational aspect of cultural studies associated with video games. This network creates a final cluster with only two items that serve to identify relationships between the teaching of history and culture.

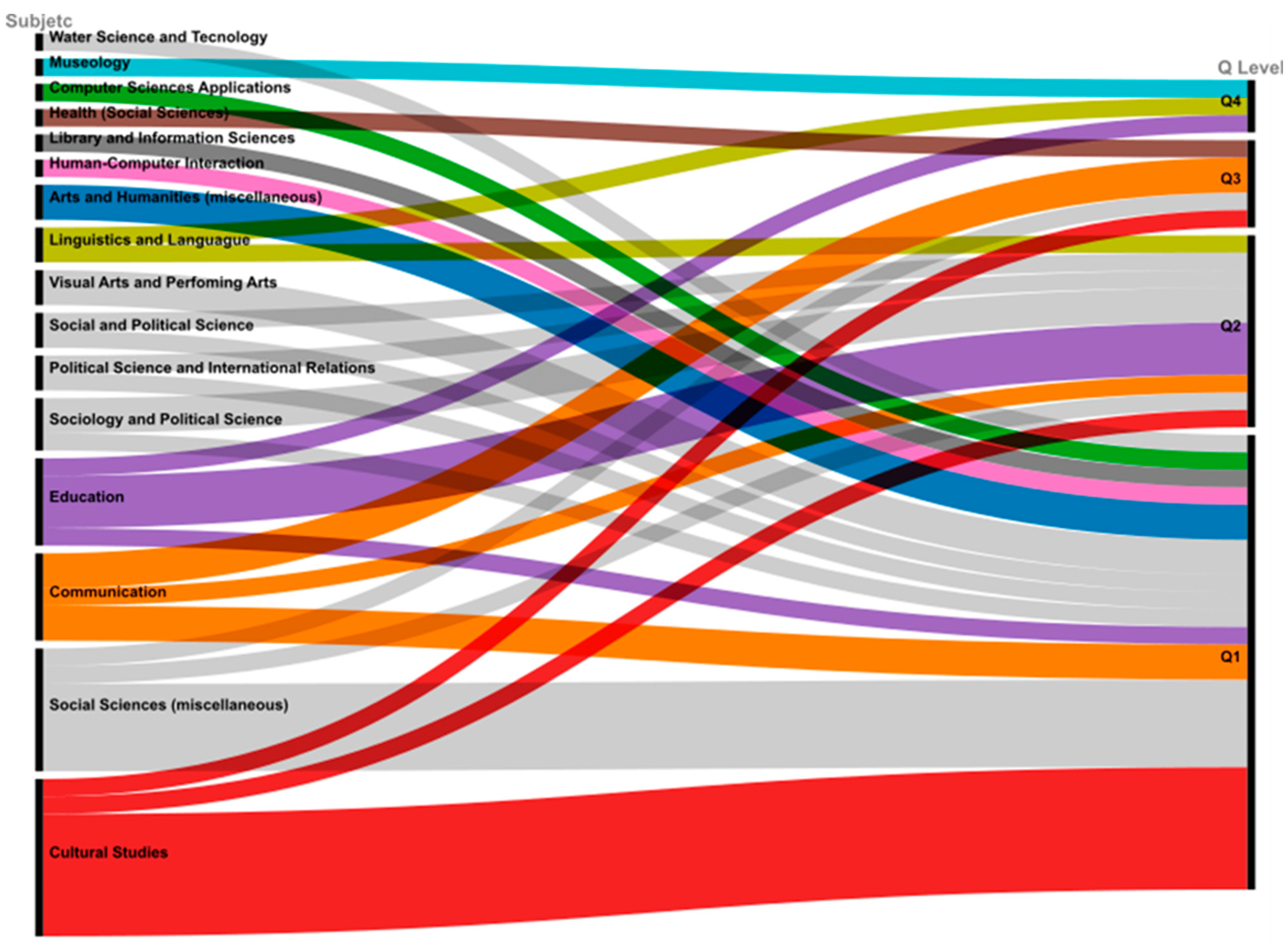

The articles analysed in the two databases (WOS and Scopus) were published in indexed journals, which are associated with specific categories. In particular, cultural study journals represented 20% and social science journals 15.56%, followed by communication 11.11% and education 11.11%. The rest belonged to less representative portions of various areas and lower percentiles, as represented in

Figure 3.

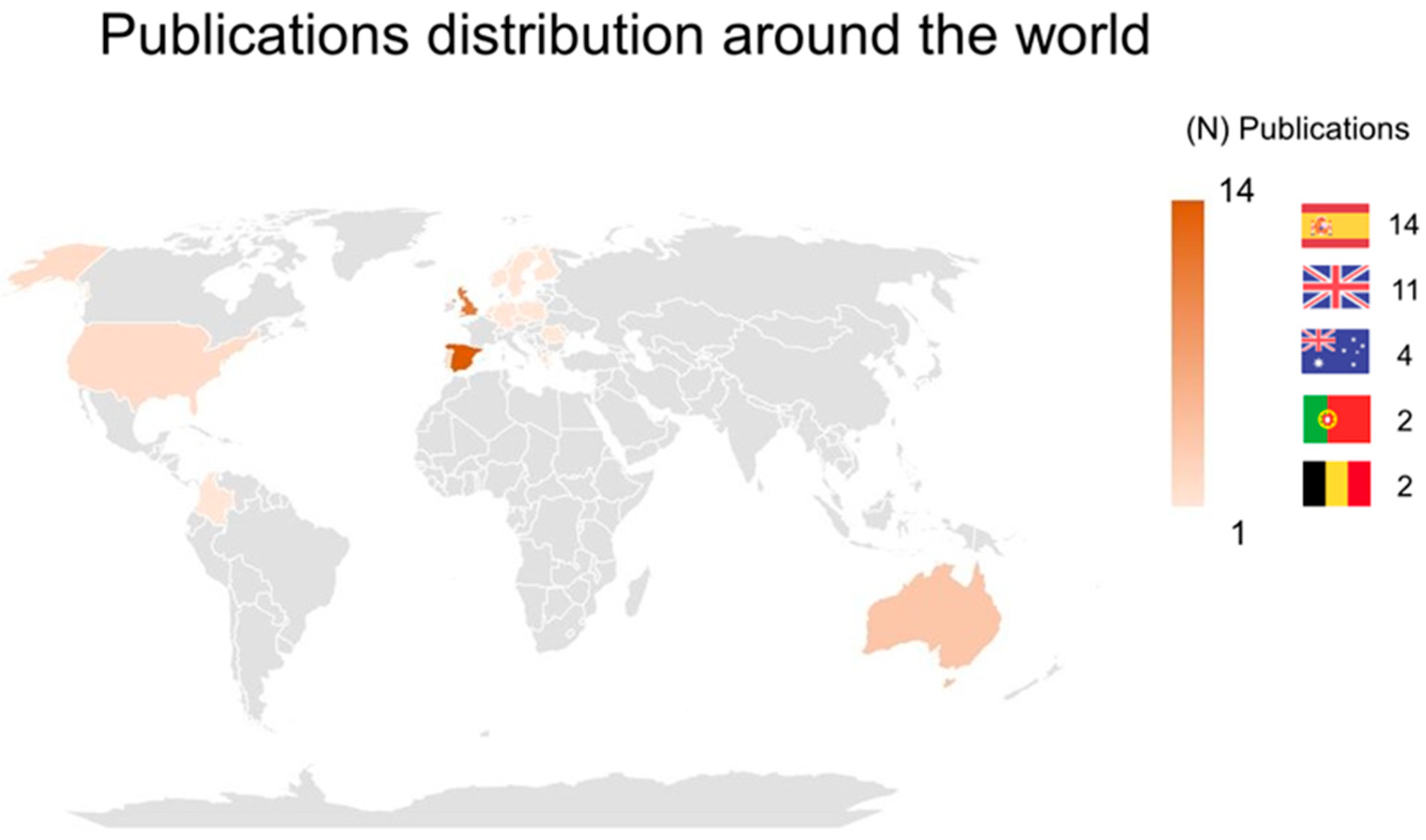

3.2. RQ2. What Is the Geographical Distribution of Publications?

This research establishes the first author of the articles and their provenance as a binding element when defining the geographical location of the research carried out. This criterion is selected as cultural objects are studied rather than populations or individuals. It is also due to the global nature of video games as a means of cultural dissemination. As a result, we found that analysed studies were distributed among a total of 18 countries. A detailed analysis showed that 31.11% of the studies were carried out in Spain, followed by the United Kingdom, where 11 publications represent 24.44% of the research analysed. This was followed by Australia with 8.88% and Portugal and Belgium with 4.44% each. Finally, with a presence of 2.22% and only one entry in the final study base were Germany, Poland, United States, Greece, Czech Republic, Cyprus, Slovenia, Norway, Netherlands, Finland, Sweden, Romania and Colombia. The heat map in

Figure 4 shows the areas with the highest number of publications.

3.3. RQ3. What Is the Distribution of Articles according to Their Position in the Database?

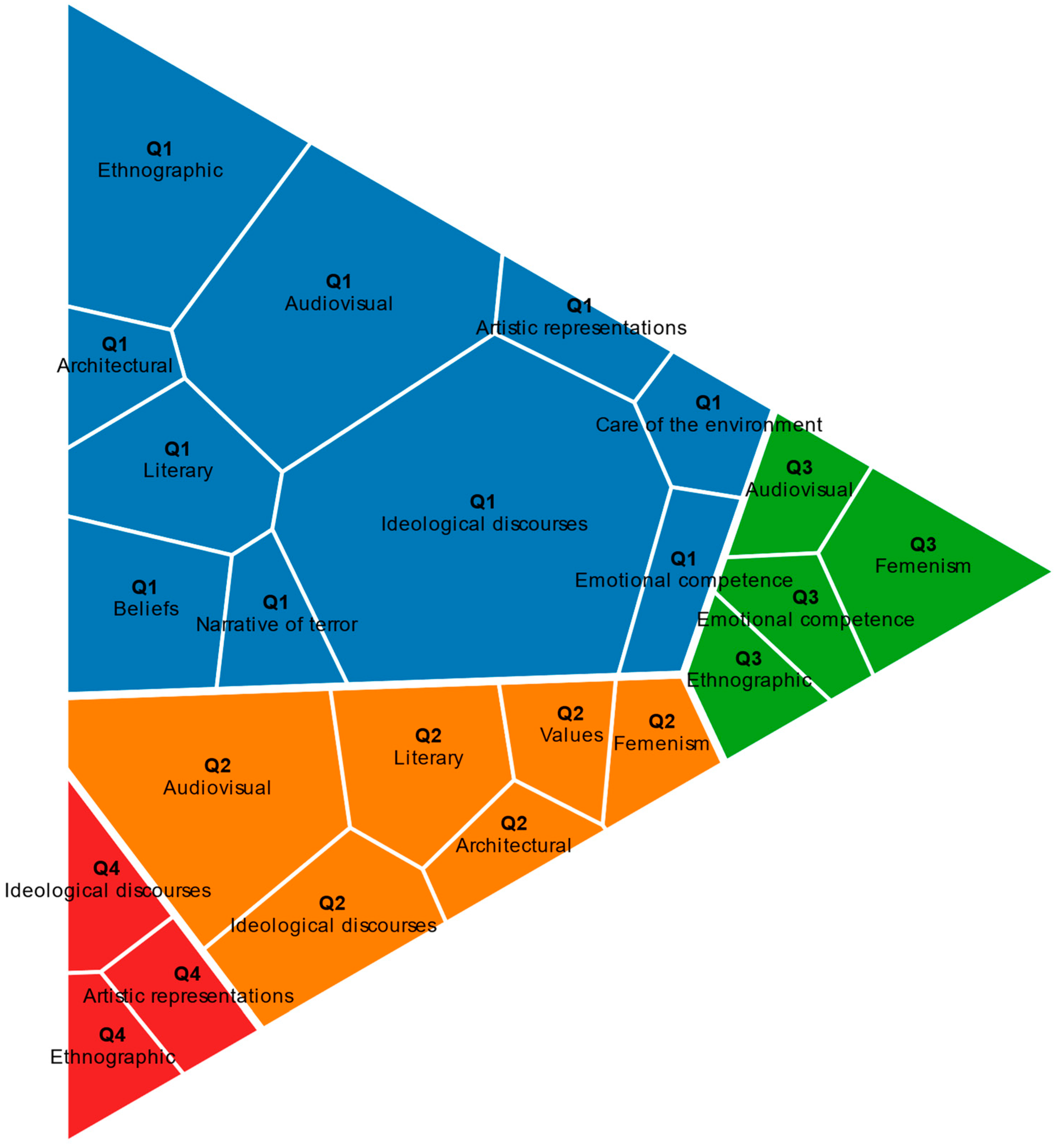

The journals containing the articles selected for this review were classified according to the quartile assigned to them in Scopus, in accordance with their year of publication. Thus, 57.77% of the articles were published in journals in quartile 1 (Q1), 24.44% of the articles belonged to the second quartile (Q2), 11.11% of the studies were in the third quartile (Q3), and finally, 6.66% of the articles were in the fourth quartile (Q4).

The analysis of publication rates allows researchers to find relationships between these and countries or areas of publication. These are distributed similarly to the number of publications and countries involved. It is striking that Spain, despite being the country with the highest number of publications, is also the country with the most moderate indexing indexes (Q3) and (Q4); while Spanish publications are distributed throughout all quartiles, British publications only appear in the first two (Q1) and (Q2), the language of all articles being English.

On the other hand, it is noteworthy that the origin of publications is not directly linked to indexation, as countries with few records in the database were found in the first quartile (Germany, Poland, Cyprus, the Netherlands, Finland, Czech Republic, Sweden, etc.).

Figure 5 clarifies these relationships.

3.4. RQ4. What the Methodological Approaches and Research Methods Are Used in the Selected Studies?

The studies were classified according to their approach as quantitative (6.67%), qualitative (68.89%) and mixed (24.44%). It is possible to establish a relationship with the methodologies used in this research;

Figure 6 connects them and states that case studies are the method most used by video game researchers (17.78%), followed by exploratory studies (13.33%) and ethnographic studies, which represent 11.11% of the total. Theoretical studies were used by 8.89% of the research, while systematic literature reviews, descriptive studies, experimental studies and autoethnographies each accounted for 6.67% of the studies, while video game analysis, content analysis and critical-reflexive studies accounted for 4.44% for each type of study. Finally, IAP research, comparative and multiple case studies stood at 2.22%.

3.5. RQ5. What Is the Typology of the Video Games Presented or Analysed?

With regard to the type of video games analysed, it was found that 26.67% of the studies analysed Mix-Games, followed by educational video games at 15.56% and shooters at 8.89%. Simulators or simulation games accounted for 6.67%, as did action games. RPGs and adventure games accounted for 4.44%, while strategy, interactive fiction and horror games accounted for only 2.22% each. Finally, there were up to eight game studies that could not be categorised, either because they did not directly use a video game but rather elements of it or because of the typology of the study; this sample represented 17.78% of the studies in this category.

Figure 7 allows researchers to establish relationships between genres and their use, making it clear that the preferred form of introduction is the direct use of the video game or DGBL; the fact is that, in its configuration, this table states the polyvalence of the video game in terms of its multiple forms of introduction or implementation and the typology of the game to be used, allowing researchers an almost endless range of possibilities of association.

3.6. RQ6. How Are the Video Games Introduced and How Do They Interact with the Objects of Study?

In order to analyse this form of introduction, categories were established based on the objects of study. This made it possible to differentiate between digital game-based learning or DGBL, simulators, serious games, blog analysis, etcetera. Specifically, the most commonly used form of introduction was direct introduction, categorised by the researchers as DGBL: video game and accounting for 35.56% of the studies. This was closely followed by the creation of video games at 17.78% and DGBL for serious games at 17.78%. Some studios merge DGBL with the creation of their own video games at 4.44% while blogs and simulators represent very low portions of around 2.22% for each form of introduction.

Studies that did not make a direct introduction of the video game, which often include theoretical studies and other research not focused on the video game and its use, accounted for 17.78%.

3.7. RQ7. What Technology Associated with the Video Game Is Used?

In order to answer this question, it was necessary to differentiate between the direct use of video games, their creation and the study of their elements or socialisation environments. In this way, the research allowed us to identify that the direct use of video games and their study represented the highest percentage of the 45 studies reviewed at 55.56%. In total, 15.56% used video game creators and analysed the process, and 22.22% of the studies analysed the video game environment and associated productions such as the creation of blogs, wikis or forums, the content of YouTube or Game Jam and the situation of the industry itself. In total, 6.66% could not be categorised as they were reviews of the literature with different perceptions or objectives and could not be categorised.

3.8. RQ8. What Are the Titles or Video Games Used?

The analysis of the titles and video games analysed was so extensive that it should be presented in subsequent research; however, the researchers identified a trend that can be stated in this study. This trend is manifested in the prevalence of narrative and war titles that mostly represent dominant cultures in the video game industry. The United States is undoubtedly the big winner in this area, with its productions accounting for 50% of the studios analysed. Of the 45 studies included in the final sample, 10 analysed war games produced in America narrating conflicts from an Americanising perspective. Only three of them included video games that depicted non-Americanised representations of conflicts. In total, 22.22% of the total mainly analysed the Medal of Honor, Call of Duty or Ghost Recon sagas and left a small space for productions such as This War of Mine and other stories with a different cultural perspective.

Research on well-known North American sagas such as Red Dead Redeptiom or GTA is also common in these studies; 17.78% of the studies include one of these games of American origin and representational culture [

34,

35].

There are Japanese titles such as Final Fantasy, which, despite being a mass game, makes a very diverse cultural reinterpretation, taking elements from different religions and cultures [

36].

The rest of the proposals are very unevenly divided between research that involves the creation of a video game through tools such as Roblox or Unity [

37] and research that serves to represent and highlight minority cultures [

38]; these video games that are not so massive, and with a very specific cultural perspective that is little-disseminated, opens the way to a representation of minorities and cultural peripheries in the video game industry with proposals such as Dominations, or an analysis of the representation of women throughout a long list of games about vampires [

39]. Spanish culture is represented in The Foolish Lady, a video game based on a play by Lope de Vega [

40].

3.9. RQ9. What Is the Cultural Theme Being Studied and Represented in the Studies Analysed?

The identification of cultural themes requires detailed analysis due to the thematic diversity of the objects of study and the great variety of themes obtained in the formal analysis.

Figure 8 is intended to shed light on this fact. In order to reach a consensus on the most representative cultural themes, several full-text readings were necessary, as the researchers had to agree on which cultural theme was represented in each study. After generating a debate and subsequent consensus on these themes, it was concluded that militarism and ideological transmission are the most repeated cultural elements at 26.67%. By contrast, other elements, such as audiovisual culture or “Game culture”, represent 13.33%. The rest are particular and minority interpretations of elements such as the Japanese, Portuguese, Mesopotamian culture or Spanish or North Korean popular culture; representations of specific cultures and geographical areas together account for slightly less than 20%. Some studies on sculpture, architecture, religion or theatre, all with rates of less than 2.22% and being too scattered, did not allow any decisive conclusions to be drawn.

3.10. RQ10. From Which Dimension Is the Cultural Approach Carried Out

The researchers identified a total of 15 cultural dimensions, which are set out in the coding section of this question described in the aforementioned table. Categorising these studies on the basis of cultural dimensions made it possible to identify the dimensions from which video games approach culture.

The dimension associated with ideological discourses was completed with a total of 12 studies, representing 26.67%, which is the most repeated cultural approach, followed by the audiovisual approach at 22.22% and the ethnographic approach at 13.33%. Literary approaches were reduced to 8.89%. This was followed by feminist studies 6.67%.

Other representations, such as architectural representations, artistic representations, human beliefs and the development of emotional competence, represent a very small, individualised percentage at 4.44%. This was only lower at 2.22% in the case of the approaches made in the dimension of terror narratives, values and care for the environment.

Figure 9 shows the relationships between the cultural dimensions and the indexation quartiles.

3.11. RQ11. What Results or Conclusions Do Researchers Obtain in Relation to the Culture-Video Game Binomial?

The culture–video game binomial is the main object of study in this research group and particularly of the Thesis within which this work is framed. It could take years of research and development to resolve a small part of it, but preliminarily, and on the basis of the studies analysed in this research, we can already reach some key ideas about this relationship, which are set out more extensively in the conclusions of this work.

The results obtained and analysed by the different studies reviewed show that video game is a powerful element of cultural dissemination, which has many diverse ways of reaching the population. It approaches culture from environments as different in cultural reproduction and transmission and does so both inside and outside the classroom. In the process, it works not only from the reproduction of content but also from the creation of video games and experiences of its own, representing both mass and minority cultures. And as if that were not enough, the relationship between video games and culture also manifests itself in the creation and generation of new cultural contexts associated with the groups or subcultures that are generated. This, in itself, makes the video game an element capable of generating and modifying cultural perceptions.

Specifically, it is observed that video games produced in English gain notable advantages, especially when using domain-specific programming languages, but also because of the dominant position of their industries worldwide. This suggests a correlation between the language of development and the success of video games in the global market and culture.

The research reviewed shows that video games can contribute to knowledge building and foster collaboration between players, leading to a better understanding of their own lives and realities. This aspect highlights the importance of video games as effective educational tools, especially in the transmission of cultural aspects.

Furthermore, video games based on social interactions have been found to have the potential to trigger positive emotions such as joy, satisfaction and enthusiasm in players. These emotions contribute significantly to increasing players’ motivation and interest, which supports the idea that the social dimension in video games is a crucial factor in their cultural impact. Such is the impact that video games are even considered tools for building resilience and self-acceptance [

41].

On the other hand, it is evident that the video game industry exerts a significant influence on the production of games for different genders and on the cultural construction around these genders. This determines how video games can reflect and perpetuate cultural norms and gender stereotypes, as well as influencing players’ preferences [

42]. However, it is the latter who must decide how to interpret the messages received, which makes the video game not only a disseminator of the message but also a means to expose it to criticism and reflection [

43].

Gaming tendencies vary according to culture and gaming preferences and are often structured around specific productions and cultural contexts. This indicates that video games have a cultural impact on how people spend their leisure time and relate to digital entertainment. But video games also generate their own culture and influence the socio-cultural profiles of players [

44]. Studies on visual culture or gamer culture support this, identifying not only the medium, but also production, gameplays, wikis, forums and other environments as an object of study that allows them to define the profile of players and the cultural content they generate [

44,

45,

46].

The results also indicate that video games are considered part of culture and that they influence the perception and understanding of the world. These games can serve as powerful tools to transmit values, foster empathy and identification with characters and situations, and contribute to the construction of cultural and national identities.

In summary, research on the culture–video game binomial reveals a series of results that highlight the importance of video games in today’s society. These results range from their impact on education and the construction of knowledge to their influence on politics, religion, the perception of illness and culture in general. Video games ultimately emerge as powerful cultural tools that influence various aspects of contemporary life and perceptions of reality.

3.12. RQ12. Is There a Direct Impact between Video Games and Human Culture?

Therefore, the answer is yes. There is a direct impact between video games and human culture. Although there is still not enough research on the subject, the conclusions of our study and some of the documents analysed allow us to affirm that there is a direct impact. It is also possible to differentiate two groups and ranges of scope.

Firstly, there is a general and global impact developed by the most commercial and extensive productions on the market. With greater dissemination and extension, multiplatform access and large financing campaigns, they allow their message to reach a large number of audiences. They transmit often ideological and cultural messages that have an impact on society by constructing an intentional image of different cultures or historical events, such as the World Wars, Terrorism or American Exceptionalism.

On the other hand, this study has made it possible to identify what are known as specific impacts. Specific impacts are those that are made on small portions of content, with a low diffusion but greater impact. They are mainly associated with minority cultures, with little representation in society, and which have often been biased or manipulated. But they find in video games an opportunity to show themselves to the world and to endure over time. In this way, some video game development and research proposals such as the Sami Game Jam [

40], or the video games Primeira Armada da Índia [

47] or The Rights Hero [

48] exemplify that there are spaces beyond the commercial industry to develop video games and culture, indigenous culture, Portuguese culture or social and emotional values in the struggle for human rights and non-discrimination.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

The main objective of this research is to analyse the relationship between video games and cultural transmission, investigating the motives, origins and cultural assets, as well as the impact of video games as a means of dissemination in the transmission of human culture. To this end, a systematic review of the literature was carried out to answer 12 research questions. These questions covered hot spots or terms in the literature, including the thematic scope of the journals and their positioning, their geographical location, and the methodological and technological characteristics of the studies carried out. In addition to that, this study sought to identify the cultural themes transmitted through video games, which are reviewed by the researchers, categorising the cultural dimensions and the procedures for their introduction into society to analyse the results and identify the impact of video games on culture.

The answer to all these questions has already been stated in the previous section, so in this last section, it is time to identify the most relevant findings of this research and relate them to each other.

First of all, we must relate our conclusions to the previous studies mentioned at the beginning of this article, concluding that this research has been able to confirm the initial preconceptions established around the research that point to video games as a powerful means of ideological transmission and dissemination [

24,

25]. And confirming that there is intentionality in the political–cultural development that is established around the production of video games [

28], our study manages to enunciate and clarify these relationships thanks to the establishment of elements such as the most reproduced dimensions of cultural approximation and the study of the origin of publications and video games analysed or their socio-cultural impact. It also explores the means for the use and analysis of video games both within and outside formal and educational contexts.

Having stated this general idea, it is very relevant to identify the journals involved in the topic of study of cultural, social science and communication journals. But it is also important to identify the environments and connections that exist between these articles. They highlight that cultural studies, game studies and new media of visual representation claim their space in modern culture and are directly interrelated with video games. The fact that 82.21% of the studies were published in journals in quartile 1 or (Q1/Q2) is representative of the fact that these are high-impact studies that generate a high level of interest in society and researchers.

On the other hand, the analysis of the areas or countries of publication reveals some relevant data on how research is conditioned by the characteristics of the research environment under study, the number of productions and their development. It is striking that although Spain is the country that publishes and researches most on culture and video games, only one of the objects of study focuses on its own culture.

With regard to methodological approaches, it is striking that qualitative studies predominate, to the detriment of quantitative studies, and that, in addition, most of these studies do not use samples or study populations that allow a direct impact on the assimilation of content or other factors to be measured. This identifies the need for an initial significant study for this thesis, which is to carry out a broader and more concrete study on the direct impact of video games on the consumer, which could have a mixed or quantitative component.

However, the wide variety of techniques and methodologies used allow for a very broad and diverse conceptual approach to the subject. A large number of resources and research methods are available. Although the preferred means of introduction is the direct introduction or DGBL, based on the subsequent study, it is true that these studies are not only structured around the video game as a tool already created.

From the educator’s perspective, a total of 12 research studies with educational objectives were analysed in this study. That is to say, 26.67% of the studies responded directly to research carried out in educational environments and with educational intentions, which demonstrates the close link between video games and the educational system and allows us to state the acceptance of researchers and teachers of this medium as a tool for cultural transmission and assimilation.

The role of methodological approaches and research that approach the problem from the perspective of video game design using video game creation tools and software allows them to create their own content and is also very relevant. This type of research and methodologies sets a reference as well as a fundamental tool for educators and for those who decide to research with video games. Its use is directly related to the transmission of non-dominant or peripheral cultural discourses or representations and allows us to identify a pattern of development that advocates minority proposals as a source of more diverse and inclusive cultural dissemination, reflecting all cultures and societies.

The most repeated titles and video games make it possible to identify and refute a previous idea; there is a predominant discourse and narrative in video game design, and it is in the hands of society to assimilate it as valid or not, for this it is important to verify those productions or ideas that are on the margins of the mainstream industry. This idea is based on the fact that most video games are produced in specific sectors, such as North America, Japan and Western Europe, which are politically and socially dominant geographical areas.

This study has also managed to establish a table with 15 dimensions from which video games approach culture. This categorisation makes it possible to identify those dimensions that currently prevail in the cultural dissemination carried out through video games, placing the reproduction of discourses and ideological messages as the most repeated cultural approach; whether or not this is the case in the future is something that will have to be elucidated by future research, which will be able to take the dimensions already established as a reference. This work is particularly significant and useful for researchers who, from now on, will not have to construct studies similar to this one from a vacuum.

Finally, as can be seen in the last two questions, after this research, it can be affirmed that video games have a direct impact on the transmission and assimilation of culture. In addition to the results presented above, on which no further discussion is considered, the aim is to expose the elements implicit in the process of the assimilation–transmission of cultural elements intrinsic to the video games that have been identified.

This study has identified three agents that intervene directly in cultural construction and that are reflected in the studies analysed. These are (1) the interlocutor or end consumer, (2) the researcher or video game developer and (3) the previous experiences or cultural heritage of both developers and consumers.

Having defined the impact of video games on human culture, this research identifies the impact of video games from their design, focusing on the origin of cultural manifestations and the directionality of the communicative intention with which video games are made and developed. It is important to differentiate between two types of productions as follows: (1) large-scale productions and (2) minority or peripheral productions; in this differentiation lies a large part of the basis of the study. Distinguishing these two types of productions is to distinguish the intentionality of these productions and is a first step to understanding the impact of video games on culture.

Large-scale productions are easily recognised by a marked context and cultural heritage, in which the message implicit in the video game is launched to players with a clear intentionality both in productions aimed at the general public and in more modest productions to impose or extend an idea [

22]. However, it is in these larger productions where these issues are more embedded due to the fact that their scope is undoubtedly greater, as well as the economic or socio-political objectives that drive them. In this case, the industry is guided, albeit to a lesser extent by social demands, with commercial and political demands deciding which narratives or cultural spaces are or are not represented. This has an impact on society and the interpretation of certain aspects of society.

Small productions can be developed either by small video game studios or by developers independent of the big industry who seek to create their own games with their own characteristics that may not fit into the general standards or typologies of marketing companies operating in the market [

48,

49]. In both cases, there is clearly an intentionality, but this is not market-driven and is often found on the so-called periphery or social-political margins. This allows them to move away from stereotypical messages and cultural representations and to embrace the representation of minority or marginalised cultures [

25].

On the other hand, the process of the transmission–assimilation of culture is not only nourished by the intentions of the development agents involved [

13]. It is also built on the basis of the interactions that consumers have with the environment. Additionally, considering the directionality of these interactions, in this study, we identify directionality from the inside out and from the outside in.

In the first place, we can identify the directionality that emanates from inside the video game toward the outside. The content a video game produces can be related to an already known culture or develop a new culture associated with the game environment; a living example is the so-called gamer culture [

15]. This directionality is represented by the creation of wikis, forums or video game transmission through Youtube, Twitch, and so on. These construct a new corpus with new ways of interacting, addressing someone, consuming content, and so on.

Specifically, we speak of directionality from the outside when video game studios or developers are influenced by specific aspects of the culture of their area or social moment [

22], as well as when they intentionally study and take elements from specific cultures that directly influence their design work. There are many examples of this, such as when the object of interest was the Wild West, the dehumanisation of war and conflicts or very recently, the interest of the general public in Viking people and myths. These patterns of choice or development always combine with a greater number of productions focusing on a particular culture.

Finally, the interpretation of the players comes into play, which is influenced by the two previous processes as well as by previous personal experiences and self-concept or critical thinking skills [

13,

15]. Thus, a modern Call of Duty video game set in the Middle East is not understood in the same way from the perspective of a North American player as it is from the perspective of a European or Eastern player. The player’s own cultural background has a direct influence on how he or she interprets messages implicit in the video game.

To conclude, these researchers consider that in the future, it is necessary to carry out new literature reviews that analyse a changing and evolving context in which the irruption of new media, forms and interests substantially modifies the cultural impact of video games. In a globalised society, it is complex to determine what the new dominant discourses could be, but research has the task of exposing these situations. It should also be borne in mind that although the research questions were broad and strongly debated, their specific nature may have left behind points of interest or points of study that could be analysed. In subsequent reviews, it is necessary not only to analyse such points but also to consider new media or developing spaces that are yet to come, such as the full implementation of virtual reality, haptic technology or the development of artificial intelligence within video games, which, for example, may give rise to generative AI within NPCs, Non-Player Characters, that restructure intrinsic cultural meanings.