Abstract

Over the last 30 years, international education policies have emphasised the need for more inclusive environments, especially for previously marginalised and excluded populations. This article explores the status of culturally and linguistically diverse students with special educational needs in Spain between 2009 and 2019. Disaggregating the data by gender and origin (Spanish, EU, and non-EU), we compare the relative risk ratio (RRI) of ending up in a special education pathway for each group and relate it to the poverty risk index. The results reveal that male students from non-European backgrounds are more likely to attend a special school and that poverty has a different impact on the schooling of students depending on their origin. Therefore, while all Spanish laws support the rights-based anti-discrimination principle of equitable education, international and national policy objectives do not appear to be confirmed by educational practices. We conclude that the findings indicate a Eurocentric perspective that reads ‘difference’ as a form of deficit and propose to begin to question the role that colonial culture can play in developing inclusive policies and practices.

1. Introduction

The Salamanca Statement and the Salamanca Framework for Action [1] have been a source of inspiration around the world, having a significant impact on how education systems respond to student diversity [2,3,4]. Subsequently, the 2030 Agenda [5] broadened the horizon by reinforcing the role that inclusion, together with equity and sustainable development, has in addressing the social, cultural, and economic barriers that limit quality education and learning. Sustainable Development Goal 4 emphasises the need for more inclusive environments not only for learners with SEN (special educational needs) but for everybody, especially previously marginalised and excluded populations [5].

Consequently, over decades, inclusion has developed as a field of constantly open tensions [6], the resolution of which is always partial because it is propaedeutic to the emergence of new tensions and challenges in an increasingly inclusive vision of social justice. One of these tensions relates to the question of who the groups of included students are and which students continue to be referred to special education, based on decisions made by guidance teams. In line with international guidelines, Spain’s recent Organic Law 3/2020 on Education states that the education administration is committed to developing a plan to ‘reduce’ the number of special schools, with a view to improving resources and conditions in ordinary schools and promoting inclusive education [7].

Currently, in Spain, students with special educational needs (SEN) can be classified into seven categories: hearing impairment, visual impairment, motor disability, intellectual disability, pervasive developmental disorders, severe behaviour/personality disorders, and multiple disabilities.

These students can be placed in mainstream schools, in an alternative classroom within the mainstream school or, in cases of greater severity and after a psycho-pedagogical assessment, in special schools until the age of 21 at the latest.

According to the current Spanish law [7], schooling in special schools will only be carried out when measures for attention to diversity in mainstream schools are insufficient to attend to these students’ needs. This schooling, aimed at students with different types of disabilities, is carried out during the daytime and includes a flexible curriculum focusing mainly on the acquisition of communication and motor skills.

Together with other authors [8,9,10,11], we share the conviction that the debate on inclusive education should not be reduced to the issue of the placement or allocation of students in certain spaces. We also believe it is necessary to look deeper into the dimensions of presence, learning, and participation in order to evaluate the progress of educational inclusion. However, we consider presence to be above all a necessary, although not sufficient, condition that can provide us with information on the institutional mechanisms of schooling and help us explore the subordinate and subaltern positions of those who remain on the margins of inclusion processes.

In this regard, one dimension of the growing concern for educational equity is disproportionality in special education, specifically with regard to culturally and linguistically diverse groups of students (CLD). Over the last 50 years, especially in the US, studies have flourished on the incorporation of CLD students in special education on the basis of dubious labels such as language, behavioural, or emotional disorders [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Some studies [19,20] found that the placement of students of colour in special education is related to low academic achievement, involvement in the juvenile justice system, and high dropout rates. In the European context, students from Mediterranean countries such as Italy, Portugal, Turkey, Greece, and Spain are overrepresented in German special schools [21], as are Afro-Caribbean students in the UK [22,23] and Romany students in the Czech Republic [24], Bulgaria, and Hungary [25,26]. In Israel, Palestinian students have higher rates of disability than Jewish Israelis [27] but lower rates of receiving special education services [28].

A key concern with disproportionality—the overrepresentation or underrepresentation of student groups in special education—is whether these trends mean certain students are misidentified for services [18,29]. In this regard, disproportionality has policy implications for schools seeking to provide appropriate educational services for all students [30]. Indeed, inappropriately placing students who do not need such support in special education pathways as well as failing to provide support to students who would benefit from such support means reducing students’ educational opportunities [23,31].

Therefore, the misplacement of students in special education is problematic as it is not only stigmatising, but it can also deny individuals the high quality and life-enhancing education to which they are entitled [32].

Among the causes of this inequality affecting CLD students, researchers highlight a form of institutional selection based mainly on the perception of language deficits as learning disabilities [33,34], misidentification due to the cultural biases of professionals [18,35,36,37], and the historical legacy of a deficit view of difference [38,39,40].

In Spain, there is no research on this subject to date. Therefore, this is a pioneering study that was carried out with the aim of opening a debate on the situation of CLD students in special education and the educational opportunities they are guaranteed in Spain. To this end, we use, on the one hand, temporality as a key dimension of our approach, situating ourselves at specific points in time to detect the historical nature of inequalities affecting culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) and SEN students. On the other hand, by recognising the culturally situated and historically produced nature of difference, we see disability policies as an expression of power relations that affect students, families, and communities [41]. In this regard, we use Quijano’s [42] notion of the coloniality of power as an analytical category to explore the nature of intersubjective relations and to investigate the practices of exclusion and oppression. This pattern of power, originating with European colonialism in the early sixteenth century, creates a universe of intersubjective relations of domination under Eurocentric hegemony [43] in which some social groupings exercise control over the behaviour of others. This produces subaltern subjectivities [44] that are not only subject to forms of political–economic domination, but also a Western cultural hegemony that places non-European culture in a structure of asymmetrical and hierarchical relations. Despite the end of historical colonialism, this dimension of cultural and intellectual domination of Western hegemonic power continues to operate and perpetuate situations of oppression that affect all social spheres, including education [42]. Thus, we consider that it is fundamental to adopt this perspective in order to investigate whether subalterns such as CLD students with SENs are being marginalised or excluded by ordinary schools.

At the same time, firmly believing that identities are not one-dimensional, we draw on intersectional theory [45] to describe how different axes of identity (gender, origin, income) intersect in subaltern subjectivities and what kind of experiences they produce.

Intersectionality has proved to be a productive concept for examining the dynamics of difference [46]. Therefore, we use it to understand how the interaction of multiple systems of oppression shapes opportunities.

This type of analysis allows us to avoid abstract and decontextualised narratives about CLD students and helps us to capture the impacts of different social constructions on their schooling.

Therefore, from these perspectives, our study aims to map the human geography of special education, exploring the complex relationships between educational inequalities, the role of special education, and culturally and linguistically diverse students (CLD). Specifically, our research aims to: (a) assess whether the linguistic and cultural origin of students, in combination with gender, is a factor that is related to a higher probability of being enrolled in special schools with regard to Spanish students, (b) establish the change in rates of the presence of CLD students in special schools during the period 2009–2019, according to their origin and gender, and (c) verify whether there is a link between the risk of poverty and social exclusion of families and the risk of enrolment in special schools according to their linguistic and cultural origin.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

This study is an ex post facto, longitudinal, and descriptive investigation. The data are taken from the official Spanish database of infant, primary, secondary and baccalaureate education and vocational training, which is compiled by the Sub-directorate General of Statistics and Studies of the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training “https://lc.cx/FFiyyz (accessed on 5 May 2021)”. As descriptive indicators of the data, we used the absolute frequencies of students in special schools compared to students in ordinary schools, percentages and two types of statistical indices capable of clearly reflecting the proportionality of the study data.

First, students were disaggregated according to whether they were from the European Union or outside the EU. The relative risk index (RRI) was used to compare the risk of ending up in a special education route for each minority group (students from EU and outside the EU) versus the risk for the majority group (Spanish students). The RRI is expressed as the coefficient between the risk of being enrolled in a special education school and the risk of being enrolled in an ordinary school for each analysis group (RRI = 1 when the RRI is the same in the group of analysis as in the reference group). Next, the variable of origin was interacted with the gender variable to see if this interaction led to a change in the composition of students enrolled in special education. Finally, trend lines most appropriate to the data were analysed using polynomial functions in order to define the change in rates of special education students from 2009 to 2019 and also to understand possible changes in the inclusion process.

Then, the poverty risk index or social exclusion of families according to their origin (Spanish, EU, and outside EU) was used to relate it to the RRI and find out if they are related through correlations. The poverty risk index is an external index used by the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE) which measures values in the range 0–1. With respect to the calculation of the correlations between the RRI and the poverty risk index, Spearman’s correlation has been used as a non-parametric test, since, as the data are of secondary origin, it is not known whether the population distribution meets the criteria of normality.

2.2. Variables Included in This Study

The following variables were included in this study:

- Modality of student enrolment: Dichotomous nominal variable that reflects whether the student has been enrolled in an ordinary or special education school. In addition, the concept of students diagnosed with special educational needs (SEN) has been taken into account as a mediating factor that usually determines the enrolment of students in special schools.

- Year of enrolment: Ordinal longitudinal variable with 11 levels representing the years from 2009 to 2019, which usually correspond to the years from 2009–2010 to 2019–2020. It is used to show the longitudinal evolution of the results obtained in the rest of the variables, thus enabling trend lines to be reflected through polynomial functions. It has not been included from the academic year 2020–2021 onwards, since the outbreak of the pandemic caused by COVID-19 completely halted face-to-face educational activity and migratory flows between different countries, meaning that from this point onwards, the data would be heavily biased.

- Origin of students: Nominal variable that represents the origin of students. For some analyses, this variable will be treated as a dichotomous variable (Spanish/CLD students), and for other analyses the category ‘CLD students’ will be broken down into students from European Union (EU) countries and students from non-European Union countries (non-EU).

- Gender: Nominal, attributive, dichotomous variable with two levels (female/male student or boy/girl).

2.3. Study Population and Sample

The target population of this study is CLD students with SEN between 3 and 18 years of age enrolled in ordinary and special schools between 2009 and 2019. The data used to define the type of schooling, origin, and attributive characteristics of all CLD students with SEN in Spain was taken from the official database of infant, primary, secondary, and baccalaureate education and vocational Training, compiled by the Sub-Directorate General for Statistics and Studies of the Ministry of Education and Vocational Training. Therefore, the sample participating in this study is virtually equivalent to the same population. Regarding the data extracted from the Spanish National Statistics Institute, these come from the report conducted for the Europe 2020 Strategy (INE, 2022) and describe the risk of poverty or social exclusion according to the nationality of the family of CLD students enrolled in school between 2009 and 2019.

Since the change in the participating sample in each school year is largely repeated in the following school years, it is not advisable to extract a sample number as the sum of the students in each school year as the final reference. Thus, specifying the arithmetic mean of the number of students for the school year period from 2009 to 2019 is recommended. In this period, the average number of students in compulsory education in Spain was M = 8,039,657, out of which an average of 2.2% (M = 176,815) were identified as students with SEN, and within this group, 19.44% were enrolled in special schools (M = 34,382). With respect to the nationality of students, 9.5% were CLD students (M = 763,416), while, within the student population enrolled in special education, the average percentage of CLD students was 11.82% (M = 4067.18). More specifically, within the CLD student body, 2.6% (M = 209,191.18) of the total number of students came from the European Union (EU) and 6.9% (M = 554,160.36) from non-EU countries, while in special schools, 2.3% (M = 801.91) come from the EU and 9.5% (M = 3263.45) come from non-EU countries. Finally, with respect to the gender of CLD students, 52.48% of students attending ordinary schools in Spain were girls (M = 3581,855) and 47.52% were boys (M = 3817,191), while in special schools the proportion was 58.24% boys (M = 19,812), compared to 41.76% girls (M = 11,839).

3. Results

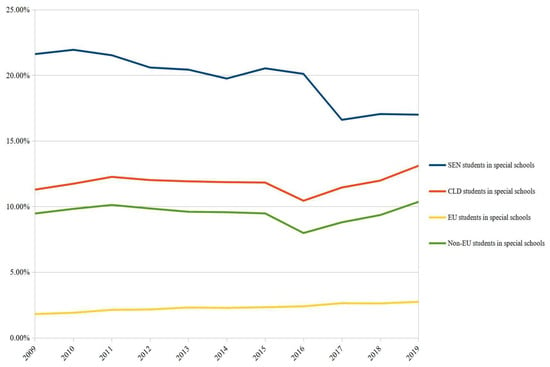

Our study reveals that the percentage comparison between the change in rates of all students with SEN enrolled in special schools and the change in rates of CLD students with SEN enrolled in special schools (Figure 1) clearly identifies two different trends. On the one hand, the rate of SEN students enrolled in special schools continues to decrease over the years, confirming a trend towards increasing inclusive education; on the other hand, the rate of CLD students, especially those from non-EU countries, increases from 11.30% to 13.12%. In contrast, the rate of EU students enrolled in special schools, remains stable throughout the period, showing an almost flat evolutionary line.

Figure 1.

Percentage comparison between the change in rates of students with SEN and the change in rates of CLD students with SEN according to their origin attending special schools between 2009 and 2019.

These data are particularly relevant, especially if we take into account the absolute frequencies of CLD students which, throughout the decade analysed, do not display an asymmetric flow, thus confirming that there were no major migratory waves that could have significantly altered the evolution of the distribution of non-university CLD students in Spain.

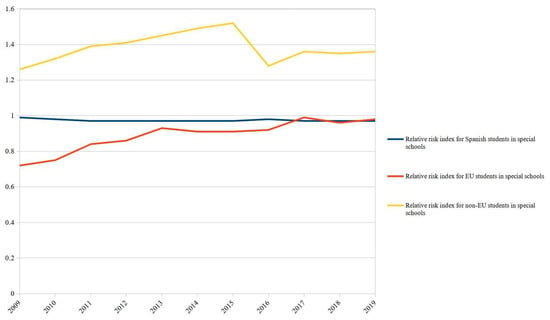

With respect to fulfilling the first research objective to assess whether the linguistic and cultural background of students is a factor related to a higher probability of being enrolled in special schools over the period 2009–2019, our study highlights two different trends (Figure 2). The pattern of disproportionality is particularly striking in the case of non-EU students, who show the highest RRI, with a tendency to increase until 2015, when the risk of being enrolled in a special education school or route for students from a non-EU country reaches an RRI = 1.52. On the other hand, although the RRI of students from the EU shows a slight increase to the present day, the figure does not exceed that of Spanish students.

Figure 2.

Relative risk index of Spanish and CLD students by origin between 2009 and 2019.

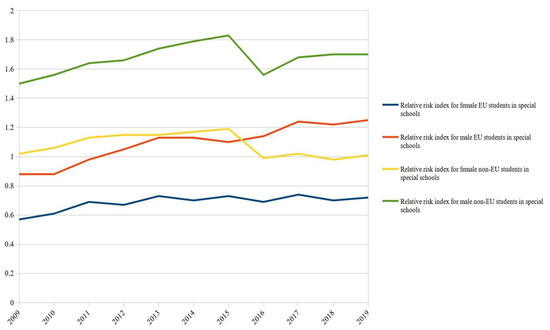

In order to identify other possible gaps, gender and student origin were interacted in a combined way in the configuration of the special education school student body in the period 2009–2019. Taking into account the interactions between origin and gender substantially increases the explanatory power of the model, as it highlights important variations in RRIs, especially for males from non-EU countries (Figure 3). In fact, our study reveals that, if we interact the data of these students with that of EU males and females and with that of non-EU females, these students are the most overrepresented in special education, reaching an RRI = 1.83 in 2015. Therefore, with an average RRI = 1.67, these students are much more likely to attend a special school than Spanish male students. This disproportion is particularly evident when considering the low RRIs of female students from the EU, who, with an average RRI = 0.69, are three times less likely to receive special education compared to male students coming from a non-EU country. It should also be noted that the situation of EU male students shows an upward trend towards increasing RRIs, although this is only slightly higher than the RRI of Spanish students (RRI = 1). These students end the period outnumbering the RRIs of female students from outside the EU. However, these female students continue to have higher RRIs (average RRI = 1.08) of attending a special school compared to female students coming from an EU country (average RRI = 0.69).

Figure 3.

Relative risk index of CLD students according to gender and origin between 2009 and 2019.

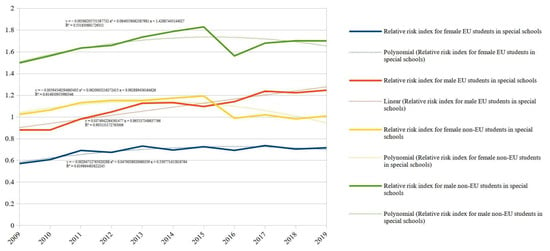

With regard to the second research objective of establishing the trend lines generated through the polynomial functions that best define the change in rates of CLD students in special schools during this period according to their origin and gender, Table 1 below shows the resulting coefficients of determination (R2) based on the polynomial regressions of degrees 1–6 for the distributions over the period 2009–2019 of the RRI of CLD students in special schools, taking into account their gender and origin.

Table 1.

Resulting coefficients of determination (R2) according to polynomial regressions of grades 1–6.

With reference to the results shown by the coefficients of determination (R2) in Table 1, the degree of the polynomial that best defines the distribution of the data is decided based on the increases in the coefficient of determination (R2), according to the degrees of the polynomial increase. The objective is to select a polynomial degree in which R² is close to 1 and which increases slightly with respect to the previous polynomial, making the decision based on the principle of parsimony. Below Figure 4 shows the final resulting trend lines for each of the six distributions, taking into account the polynomial regression selected in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Best trend lines for relative risk index distribution of CLD students attending special schools, considering their gender and origin between 2009 and 2019.

The resulting polynomial equations shown in Figure 4 point out very slight inclines/declines, indicating little increase or decrease on the y-axis for each unit increase on the x-axis, i.e., in each year of the period 2009–2019. This result indicates that the status of CLD students remains constant over 10 years, with no significant changes in the distribution of special education school students. Therefore, the condition of inequality that affects especially male non-EU students does not change, as they have a higher RRI of being placed in special schools.

Regarding the third specific objective to assess the possible link between the risk of poverty, social exclusion of families and a higher risk of enrolment in special schools according to students’ linguistic and cultural background, the RRI and poverty risk index correlations were calculated for each category, as shown in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Spearman’s correlations between relative risk index and poverty risk index according to the origin.

It should be highlighted that for students with a higher poverty risk index in families, regardless of their European or non-European origin, there is a significant correlation with a higher RRI of enrolment in special schools. Moreover, within this group students from non-EU countries have the highest correlation (ρ = 0.723). In addition, since the effect size of this link is very high, it is a relationship of great statistical significance. On the other hand, it is striking that for Spanish students this correlation is negative.

4. Discussion

Our study makes it possible to reveal disparities in the levels of inclusion in the Spanish school system and, therefore, identify areas of injustice. We have particularly focused on those subjectivities associated with multiple identity markers (disability, origin, gender, income) in order to assess how the Spanish education system responds to the intersection of these multiple identities. By relating origin to the gender variable, it became clear that, with respect to Spanish and EU students, male students of non-European origin are more likely to attend a special school. We interpret these data as confirmation that gender intensifies the effects of nationality [47] constituting an element of intersectional oppression. In fact, in interaction with origin, it can be considered as a marker that can push boys more towards special education schooling. Therefore, being male and coming from a foreign country, especially a non-EU country, produces different educational opportunities.

These results reveal the complexity of intersectional analysis, which does not allow us to essentialise the experience of DCL students (all DLC students have a higher risk of attending a special school) but requires us to explore the different multiple factors that determine inequalities and raise the question of why there is such a pronounced difference in gender and origin.

Furthermore, this unequal status experienced by this student body does not vary over the years examined. In fact, the trend lines show that this situation remained constant between the years 2009 and 2019, thus revealing the structural character of this inequality and demonstrating that these students are exposed to exclusionary practices to a greater extent than students from Spain or other EU countries.

Therefore, while all Spanish laws support the rights-based anti-discrimination principle of equitable education, international and national policy objectives do not appear to be confirmed by educational practices.

These results are in line with studies demonstrating the role of the historical legacy of inequalities and the limitations of technical approaches to equity-oriented education policies [48]. In fact, the existence of a ‘differential’ inclusion model that focuses to a greater extent on non-European learners in special schools reveals the inability of these policies to question historically entrenched power relations and recognise the complex web of contextual forces in which they are produced [49].

We believe the results of our study, which report the same risk status for both Spanish and other EU students, are indicative of a Eurocentric perspective through which ‘difference’ is interpreted. By expelling those who most deviate from this cultural canon, this perspective draws a disturbing geography of power within the space of special education by revealing the colonial structure that reproduces social hierarchies [42], and marginalises non-EU students’ bodies. In this regard, the disproportionate ‘placement’ of certain students in special schools can be explained as the reproduction of existing power relations whose origins can be traced back to a historical culture founded on a deficit perspective.

Consequently, the context of special education becomes not only a place where the persistence of a pattern of relations [50,51] maintains the status quo and reproduces patterns of injustice, but also a tool of exclusion [52] and a device for the control of difference that contains those subjects whose differences are perceived as extreme and external to the standardised norm [10]. Therefore, although over the last fifteen years Spanish education policies have legally recognised inclusive education, by not considering the colonialist dimension of special education [24] they run the risk of reproducing ‘selective’ [53] and culturally homogeneous inclusion—that privileges Eurocentric values as universal—as long as the existence of structures that differentiate between population groups is accepted. In contrast, we agree with Sandoval et al. [54] in the conviction that inclusion does not arise naturally from the current social order, but as a result of conscious, reflexive, and voluntary actions and practices that transform the structures [55] of the educational institution and society.

The results also reveal a statistically significant relationship between the RRI of CLD students and the poverty risk index, which can be viewed as resulting in a higher risk of enrolment in special schools when faced with a higher poverty risk index. However, the absence of the same relationship for Spanish students confirms that poverty cannot be considered the explanatory variable for the disproportionate representation of certain CLD students in special education and that other explanatory models need to be considered. Therefore, our data reveal a contradiction regarding the role that poverty might play in the placement of students in special schools. On the one hand, the correlation between poverty and the risk of enrolling in a special school is recognised, but on the other, this correlation is mediated by origin.

We believe the results of our study suggest that origin continues to significantly influence the risk of ending up in a special school and that poverty amplifies the effects of other variables such as origin and ethnicity.

These findings are in line with a body of literature contesting the relationship among disproportionality and poverty [29,56]. Skiba et al. [56] argued that no reliable relationship was found in their study. Other researches [57] point out that, when interaction with different categories of disability is taken into account, a more complex relationship is evident.

It is clear that poverty is related to risks such as low birth weight or malnutrition and thus tends to be more associated with disability [58]. However, the problem of assuming that poverty offers the most accurate explanation ignores possible systemic factors that may have an impact on the higher placement rates of some CLD students in special education.

We believe that the nexus between poverty and disability produces a pathologisation process which is the result of a deficit-oriented perspective on disability. This pathologising gaze obscures the colonising structures of oppression [59] that construct an ability-normative space that subordinates culturally different subjectivities.

We agree with Artiles et al. [60] that data on the impact of poverty on developmental problems in some groups also support the assumption that the consequence of living in particular conditions is the intrinsic defining characteristic of these groups. Historically, this logic has evolved into an essentialist stance about the nature of students from historically marginalised groups living in poverty.

On the other hand, by highlighting the different impact that poverty has on the schooling of students depending on their origin, our results are in line with other studies that have found that, despite equal economic conditions, CLD students are more likely to be enrolled in a special school [56,58].

Therefore, assuming that the correlation between special education and poverty reflects a true difference in the abilities of students with a high poverty risk index and those who do not have such a high index, allows us to continue without critically examining possible inequalities and the ways in which the school system may be creating or exacerbating these differences.

Limitations

This research shows some limitations in data collection. Firstly, it was not possible to distinguish between first- and second-generation students. This differentiation would have allowed us to investigate the impact of origin on inclusion processes more precisely. Secondly, as far as CLD students are concerned, the database used does not have data classified according to age, type of disability, or social class. These data would have helped us clarify under which conditions CLD students become especially vulnerable to the risk of being enrolled at a special school. At the same time, we are aware that the homogeneity to which the notion of ‘CLD students from EU and non-EU countries’ refers does not help the process of making identities visible, thus making it necessary to look more deeply into inter- and intra-group differences. The nature of the available variables makes it clear that more analysis along these lines is needed to improve our conceptual understanding of the disproportionate representation of this student body in special education.

However, despite the limitations of the dataset used in this analysis, we believe that our study contributes to providing a useful quantitative strategy to unmask the sedimentation of inequalities affecting subjectivities at the crossroads of different identity markers.

5. Conclusions

Our findings point to several important implications for inclusive policies and practices. First, in order to eliminate barriers to educational opportunities it is essential to understand and recognise the role that the context, in its socio-historical, socio-cultural, and socio-spatial dimensions, plays in the production of educational inequalities. This implies shifting the emphasis from a perspective centred on the intervention on individuals, the bearers of deficits, to institutional structures and the discursive order of educational policies. In our view, this approach would recognise special education as a colonial tool based on historical visions of deficit that affect some minorities and embedded in education policy and practice.

Second, it is critical to focus on the processes of disability identification and psycho-pedagogical assessments that determine the choice of schooling. Special educational assessment relies on tools and processes that measure and interpret culturally sensitive skills and behaviour. Therefore, we consider it necessary to explore these decision-making processes and to implement training on disability identification that includes the consideration of cultural and linguistic differences. This would help prevent practices that lead to patterns of inequality and avoid the potential harm that can come to a child who is misdiagnosed or with an inadequate education.

Third, if we recognise the paradoxical nature of special education, which although conceived with the intention of providing educational support has become a tool for social exclusion, we must consider the permanent dismantling of special education as a necessary condition for advancing educational equity.

To achieve this objective, we highlight the need to investigate special education practices at the micro level in order to discover the processes and structural effects of these practices. On the one hand, we consider this critical analysis to be a decisive element in moving towards the dismantling of special schools and, on the other hand, as a propaedeutic reflection to improve the practices of ordinary schools so that they can be the best alternative for families and guidance teams. This would consider inclusion not only as the opportunity to place the entire student body in the general education classroom, but as an environment whose practices can guarantee participation to all historically silenced subjectivities and thus advance towards the construction of a plural and just society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.A.C.; Investigation, M.A.C.; Methodology, M.A.C. and R.S.C.; Formal analysis, M.A.C. and R.S.C.; Data curation, R.S.C.; Software, R.S.C.; Writing—original draft, M.A.C.; Supervision, M.S.; Validation, M.S.; Writing—review and editing, M.A.C. and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been supported by project I+D+i “Co-teaching for inclusion: cultures, policies and practices for educational transformation” (Ref. PID2022-137000OB-I00) funded by the Spanish Ministry for Science and Innovation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: ”https://lc.cx/FFiyyz” (accessed on 5 May 2021).

Acknowledgments

I thank Gianluca Coeli for the valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- UNESCO. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education 1994; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ainscow, M.; Slee, R.; Best, M. Editorial: The Salamanca Statement: 25 Years On. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiles, A.J.; Kozleski, E.B. Inclusive Education’s Promises and Trajectories: Critical Notes about Future Research on a Venerable Idea. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2016, 24, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runswick-Cole, K. Time to End the Bias towards Inclusive Education? Br. J. Spec. Educ. 2011, 38, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Guía para Asegurar la Inclusión y la Equidad en la Educación. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000259592 (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Graham, L.; Medhurst, M.; Malaquias, C.; Tancredi, H.; De Bruin, C. Beyond Salamanca: A Citation Analysis of the CRPD/GC4 Relative to the Salamanca Statement. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 27, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefatura del Estado. Ley Orgánica 3/2020, de 29 de Diciembre, por la que se Modifica la Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de Mayo, de Educación. Boletin oficial del Estado. 2020, p. 340. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2020-17264 (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Artiles, A.J.; Kozleski, E.B.; Dorn, S.; Christensen, C. Learning in Inclusive Education Research: Re-Mediating Theory and Methods with a Transformative Agenda. Rev. Res. Educ. 2006, 30, 65–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeita, G.E. La educación del alumnado considerado con necesidades educativas especiales en la LOMLOE. Av. Supervisión Educ. 2021, 35, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieppa, M.A.; Sandoval, M. La sobrerrepresentación de los estudiantes pertenecientes a minorías culturales y lingüísticas en itinerarios de educación especial: Una revisión de la literatura en Europa. Rev. Educ. Espec. 2021, 34, e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, R. Beyond Special and Regular Schooling? An Inclusive Education Reform Agenda. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2008, 18, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiles, A.J. Untangling the Racialization of Disabilities: An Intersectionality Critique Across Disability Models1. Du Bois Rev. Soc. Sci. Res. Race 2013, 10, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beratan, G.D. Institutionalizing Inequity: Ableism, Racism and IDEA 2004. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2006, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchett, W.J. Telling It Like It Is: The Role of Race, Class, & Culture in the Perpetuation of Learning Disability as a Privileged Category for the White Middle Class. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2010, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erevelles, N. Thinking with Disability Studies. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2014, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, S.; Lindsay, G.; Pather, S. Special Educational Needs and Ethnicity: Issues of Over- and Under-Representation; Department for Education and Skills Research Report; University of Warwick: Coventry, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Youdell, D. Fabricating ‘Pacific Islander’: Pedagogies of Expropriation, Return and Resistance and Other Lessons from a ‘Multicultural Day’. Race Ethn. Educ. 2012, 15, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herry, B.; Klingner, J. Why Are So Many Minority Students in Special Education? 2nd ed.; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Skiba, R.J.; Arredondo, M.I.; Williams, N.T. More Than a Metaphor: The Contribution of Exclusionary Discipline to a School-to-Prison Pipeline. Equity Excell. Educ. 2014, 47, 546–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, T.; Hogan, D.P.; Sandefur, G.D. What Happens after the High School Years among Young Persons with Disabilities? Soc. Forces 2003, 82, 803–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, J. Constructing Disability and Social Inequality Early in the Life Course: The Case of Special Education in Germany and the United States. Disabil. Stud. Q. 2003, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, P.; Upton, G.; Smith, C. Ethnic Minority and Gender Distribution Among Staff and Pupils in Facilities for Pupils with Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties in England and Wales. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 1991, 12, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, S.; Lindsay, G. Evidence of Ethnic Disproportionality in Special Education in an English Population. J. Spec. Educ. 2009, 43, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, L. New Label No Progress: Institutional Racism and the Persistent Segregation of Romani Students in the Czech Republic. Race Ethn. Educ. 2017, 20, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Roma Rights Centre. Europe’s Highest Court Finds Racial Discrimination in Czech Schools. 2007. Available online: http://www.errc.org/cikk.php?cikk=2866 (accessed on 11 September 2022).

- European Roma Rights Centre. The Glass Box: Exclusion of Roma From Employment. 2007. Available online: http://www.errc.org/reports-and-submissions/the-glass-box-exclusion-of-roma-from-employment (accessed on 11 September 2022).

- Kasler, J.; Jabareen, Y. Triple Jeopardy: Special Education for Palestinians in Israel. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2017, 21, 1261–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinero, S.C. Special Education Use among the Negev Bedouin Arabs of Israel: A Case of Minority under Representation? Race Ethn. Educ. 2002, 5, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losen, D.J.; Orfield, G. Racial Inequity in Special Education Undefined; Harvard Education Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-1-89179-204-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cooc, N.; Kiru, E. Disproportionality in Special Education: A Synthesis of International Research and Trends. Race Ethn. Educ. 2018, 15, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhanu, G.A.; Dyson, A.G. Special Education in Europe, Overrepresentation of Minority Students. In Encyclopedia of Diversity; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 2070–2073. [Google Scholar]

- Artiles, A.J.; Herry, B.; Reschly, D.J.; Chinn, P.C. Over-Identification of Students of Color in Special Education: A Critical Overview: Multicultural Perspectives. Multicult. Perspect. 2002, 4, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werning, R.; Löser, J.M.; Urban, M. Cultural and Social Diversity: An Analysis of Minority Groups in German Schools. J. Spec. Educ. 2008, 42, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vouyoukas, C.; Tzouriadou, M.; Anagnostopoulou, E.; Michalopoulou, L.E. Representation of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students Among Students with Learning Disabilities: A Greek Paradigm. SAGE Open 2017, 7, 215824401668615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, M.; Cross, C. Minority Students in Special and Gifted Education; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-30907-439-1. [Google Scholar]

- Migliarini, V. ‘Colour-Evasiveness’ and Racism without Race: The Disablement of Asylum-Seeking Children at the Edge of Fortress Europe. Race Ethn. Educ. 2018, 21, 438–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pit-ten Cate, I.M.; Glock, S. Teacher Expectations Concerning Students with Immigrant Backgrounds or Special Educational Needs. Educ. Res. Eval. 2018, 24, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamma, S.A.; Jackson, D.D.; Morrison, D. Conceptualizing Color-Evasiveness: Using Dis/Ability Critical Race Theory to Expand a Color-Blind Racial Ideology in Education and Society. Race Ethn. Educ. 2017, 20, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiles, A.J. Fourteenth Annual Brown Lecture in Education Research: Reenvisioning Equity Research: Disability Identification Disparities as a Case in Point. Educ. Res. 2019, 48, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, B.A.; Connor, D. Tools of Exclusion: Race, Disability, and (Re)Segregated Education. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2005, 107, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigo-Arrazola, M.B.; Dieste, B.; Blasco-Serrano, A.C. Education Recommendations for Inclusive Education from the National Arena in Spain. Less Poetry and More Facts. J. Crit. Educ. Policy Stud. 2022, 20, 275–314. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, A. Ensayos en Torno a la Colonialidad del Poder—Colección El Desprendimiento; Traficante de Sueños: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, A. Cuestiones y Horizontes: De La Dependencia Histórico-Estructural a La Colonialidad/Descolonialidad Del Poder: Antología Esencial, 1st ed.; Colección Antologías; CLACSO: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2014; ISBN 978-9-87722-018-6. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, C. Interculturalidad, colonialidad y educación. Rev. Educ. Pedagog. 2009, 19, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.H. Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-47800-709-8. [Google Scholar]

- Khader, S.J. Intersectionality and the Ethics of Transnational Commercial Surrogacy. IJFAB Int. J. Fem. Approaches Bioeth. 2013, 6, 68–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefera, A.A.; Fischman, G.E. How and Why Context Matters in the Study of Racial Disproportionality in Special Education: Toward a Critical Disability Education Policy Approach. Equity Excell. Educ. 2020, 53, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramarczuk Voulgarides, C.; Tefera, A. Reframing the Racialization of Disabilities in Policy. Theory Into Pract. 2017, 56, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, A.N.; Leonardi, B.; Donnor, J.K. Perpetuating Inequalities: The Role of Political Distraction in Education Policy. Educ. Policy 2021, 35, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikelatou, A.; Arvanitis, E. Pluralistic and Equitable Education in the Neoliberal Era: Paradoxes and Contradictions. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel, S.L.; Curcic, S.; Powell, J.J.W.; Khader, K.; Albee, L. Migration and Ethnic Group Disproportionality in Special Education: An Exploratory Study. Disabil. Soc. 2009, 24, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitoller, F. La Paradoja de La Inclusión Selectiva. El Caso de Estados Unidos. In Aulas Abiertas A La Inclusión; Dykinson, S.L.: Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, M.; Muñoz, Y.; Márquez, C. Supporting Schools in Their Journey to Inclusive Education: Review of Guides and Tools. Support Learn. 2021, 36, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, B.A.; Ashby, C.U.S. Inclusion in the Era of Neoliberal Educational Reforms. In Special Educational Needs and Inclusive Practices: An International Perspective; Dovigo, F., Ed.; Studies in Inclusive Education; SensePublishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 21–31. ISBN 978-94-6300-857-0. [Google Scholar]

- Skiba, R.J.; Poloni-Staudinger, L.; Simmons, A.B.; Renae Feggins-Azziz, L.; Chung, C.-G. Unproven Links: Can Poverty Explain Ethnic Disproportionality in Special Education? J. Spec. Educ. 2005, 39, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosp, J.L.; Reschly, D.J. Disproportionate Representation of Minority Students in Special Education: Academic, Demographic, and Economic Predictors. Except. Child. 2004, 70, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grindal, T.A. Racial Differences in Special Education Identification and Placement: Evidence Across Three States. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2020, 89, 525–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcheon, E.J.; Lashewicz, B. Tracing and Troubling Continuities between Ableism and Colonialism in Canada. Disabil. Soc. 2020, 35, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artiles, A.J.; Kozleski, E.B.; Trent, S.; Osher, D.; Ortiz, A. Justifying and Explaining Disproportionality, 1968–2008: A Critique of Underlying Views of Culture. Except. Child. 2010, 76, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).