It Is Never Too Early: Social Participation of Early Childhood Education Students from the Perspective of Families, Teachers and Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- Is there a predisposition to accept students with ASD on the part of their peers? In this sense, what are their attitudes?

- -

- Are there positive friendship relations and a perception of social support from peers?

- -

- What barriers and facilitators are identified for the social participation of students in these classrooms?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Quantitative Study

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Instruments

2.1.3. Procedure

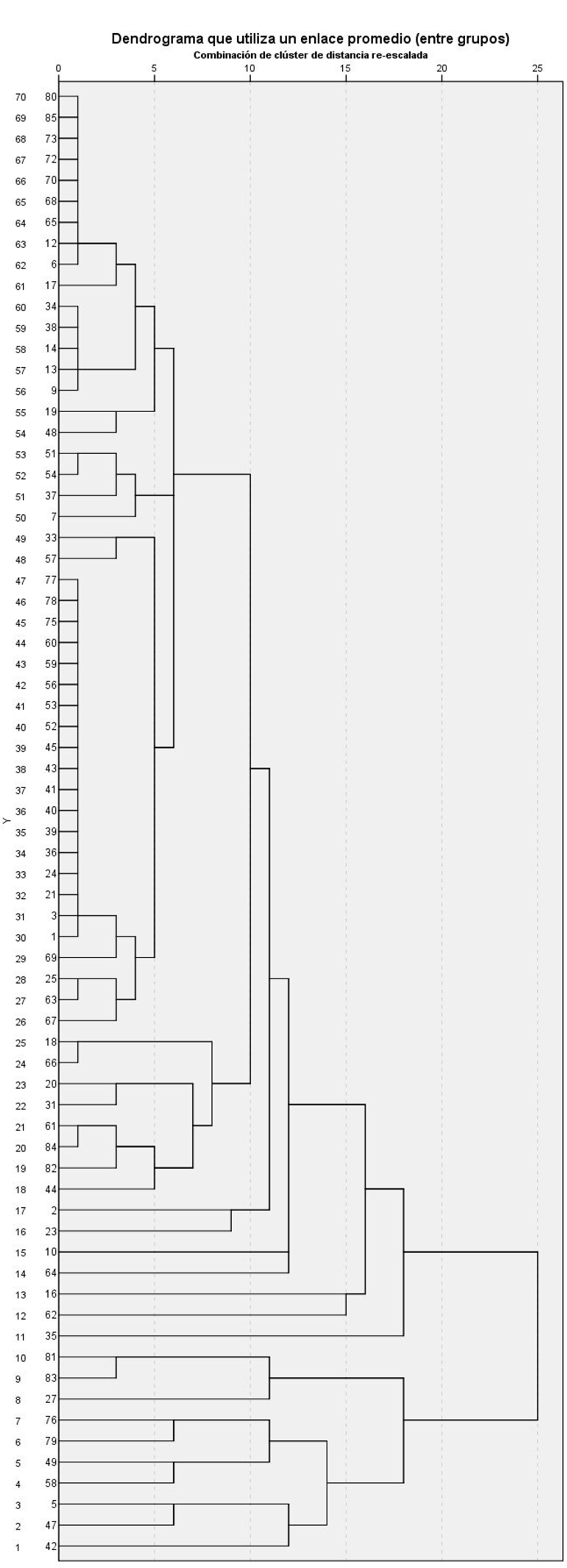

2.1.4. Data Analysis

2.2. Qualitative Study

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Instruments

2.2.3. Procedure

2.2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Study

- (a)

- Attitudes

- (b) Friends and social support

3.2. Qualitative Study

- (a)

- Barriers

Lack of knowledge/lack of competences: “We need to know how to reach the students”

At that moment, she wanted to express and do all those things; it was a great barrier [not having a language].

With us it is easier [communicating] than with the rest of the children and the other teachers, because we have a wide range of possibilities: we can do it with signs, routines, pictograms; well-established routines in the ASD classroom, thus for us it is less of a barrier for the classroom. (Paraprofessional, Len)

When he started at the age of 3 years, he could not talk; he came from being in his classroom with his classmates, but he could not talk. Therefore, in the barrier of language, with his tutor of the reference classroom he was a stopper, it was a great barrier… In all the verbal activities, he quickly disconnected and lost all interest... (Mother, Len)

- (b)

- Facilitators/Support

Support in the face of challenges:“I want to play”

I see that the child wants to play and did not try hard enough. She goes near the other kids, waiting, but there was no chance. Then, she comes to us and tells us “I want to play”. “Len, why did you pull her hair?”, “they don’t let me play”, but the reason for this is that she may still not know how to express that she wants to play. (Special education teacher, Len)

Thus, in the end, I need someone who guides me, some specialist that says “look, he is in instrumental mode, and that cannot be, you must guide him, you have to take his hand and lead him”, “these activities are great for him...” And then I say things like “look, he loves this, and he hates this...” In the end I have to try. If someone tells me “do this, don’t do that”, we may advance more. (Teacher, Are)

Peers as a factor of inclusion: “All the kids love him/her”

With respect to the children, the other mothers tell me, “your child has changed a lot, and all the kids love him”. He certainly is very affectionate, so he obviously has friends and the friendship of his classmates”. (Mother, Are)

The importance of working on the relationships among the students: “They become sensitive”

They take great care of him. In fact, if they see that he gets a little nervous, they know, and they give him a ball or something round, so that he can make it spin. If he pulls their hair, they say “ouch! AG, no”, and that’s it; if someone else pulls their hair, they get angry, but not when AG does it. They take great care of him. If he needs something, they help him. For instance, if AG wants the tap open and splashes some water out, they tell him “no, that’s bad” and they help him to open and close the tap... They help AG a lot. (Teacher, Are).

Teachers’ willingness to learn: “I learned a lot”

It was great for everyone. In fact, it was like a game: we went to have lunch, and if the image was not there, they stood up and placed the image in its place, and that was useful for everyone. It was a bit difficult for me, since I could not follow the entire schedule, although I could include other things that were not planned and which were useful for everyone. (Teacher, Nic)

Partnerships with families: “They are really committed to everything”

Her father also loves hearing things like “look, this week she did this”, because he is not present in the daily activity of the classroom. Here in the school, when they come to bring and pick them up, they enter the classroom, leave the backpack, ask questions, we talk... All that improves our communication... (Teacher, Lar)

Natural context: “Opportunities”

We are happy with his advance in many aspects. He opened much more to the other children. The teachers showed us videos of him playing with other children in the yard; he looks very happy… I want Nico to learn the routines, to integrate, to sit down in meetings, to listen to others… And he is doing those things… He may not participate in the meeting, because he can’t talk, but he listens, sees what others do, and then he tries to transmit that at home. (Mother, Nic)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Global Education Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and Education: All Means All; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. A Guide for Ensuring Inclusion and Equity in Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000248254 (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Ainscow, M.; Booth, T.; Dyson, A. Improving Schools, Developing Inclusion; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- IBE-UNESCO. Training Tools for Curriculum Development. Reaching out to all Learners: A Resource Pack Supporting in Education. In International Bureau of Education; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2016; Available online: http://www.ibe.unesco.org/sites/default/files/resources/ibe-crp-inclusiveeducation-2016_eng.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Echeita, G. Educación inclusiva. In El Sueño de Una Noche de Verano; Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Koster, M.; Nakken, H.; Pijl, S.J.; van Houten, E. Being Part of the Peer Group: A Literature Study Focusing on the Social Dimensions of Inclusion in Education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2009, 13, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramidis, E.; Avgeri, G.; Strogilos, V. Social participation and friendship quality of students with special educational needs in regular Greek primary schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2018, 33, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvonen, J.; Lessard, L.M.; Rastogi, R.; Schacter, H.L.; Smith, D.S. Promoting Social Inclusion in Educational Settings: Challenges and Opportunities. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 54, 250–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignes, C.; Godeau, E.; Sentenac, M.; Coley, N.; Navarro, F.; Grandjean, H.; Arnaud, C. Determinants of students’ attitudes towards peers with disabilities. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2009, 51, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boer, A.; Pij, S.J.; Minnaert, A. Attitudes of parents towards inclusive education: A review of the literature. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2010, 25, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Mirenda, P. Including students with developmental disabilities in general education classrooms: Educational benefits. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 2002, 17, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kefallinou, A.; Symeonidou, S.; Meijer, C.J.W. Understanding the value of inclusive education and its implementation: A review of the literature. Prospects 2020, 49, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simón, C.; Martinez-Rico, G.; McWilliam, R.; Cañadas, M. Attitudes toward Inclusion and Benefits Perceived by Families in Schools with Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, A.; Gutiérrez, H.; Simón, C.; Echeita, G. Convivencia y educación inclusiva: Miradas complementarias. Convives 2018, 24, 6–13. [Google Scholar]

- Florian, L.; Beaton, M. Inclusive pedagogy in action: Getting it right for every child. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2018, 22, 870–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisham-Brown, J.; Hemmeter, M.L. Blended Practices for Teaching Young Children in Inclusive Settings, 2nd ed.; Brookes Publishing Company: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Simón, C.; Muñoz-Martínez, Y.; Porter, G. Classroom instruction and practices that reach all learners. Camb. J. Educ. 2021, 51, 607–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S.; Drummond., M.J. Learning without limits. Constructing a Pedagogy Free From Deterministic Beliefs about Ability. In The Sage Handbook of Special Education, 2nd ed.; Florian, L., Ed.; SAGE Publishing: London, UK, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 339–458. [Google Scholar]

- Naraian, S.; Schlessinger, S. When theory meets the “reality of reality”: Reviewing the sufficiency of the social model of disability as a foundation for teacher preparation for inclusive education. Teach. Educ. Q. 2017, 44, 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruin, K. The impact of inclusive education reforms on students with disability: An international comparison. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 23, 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González de Rivera, T.; Fernández, M.L.; Simón, C.; Echeita, G. Educación inclusiva en el alumnado con TEA: Una revisión sistemática de la investigación. Siglo Cero. Rev. Española Sobre Discapac. Intelect. 2022, 53, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.; Schwab, S.; Perren, S. Teachers’ beliefs about peer social interactions and their relationship to practice in Chinese inclusive preschools. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2022, 30, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, S. Attitudes towards Inclusive Schooling: A Study on Students’, Teachers’ and Parents’ Attitudes; Waxmann Verlag: Münster, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van Mieghen, A.; Verschueren, K.; Petry, K.; Struyf, E. An analysis of research on inclusive education: A systematic search and meta review. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2020, 24, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.; Perren, S. Promoting peer interactions in an inclusive preschool in China: What are teachers’ strategies? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghin, H. The Benefits of Inclusion for Students on the Autism Spectrum. BU J. Grad. Stud. Educ. 2021, 13, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Echeita, G.; Cañadas, M.; Gutiérrez, H.; Martínez, G. From Cradle to School. The Turbulent Evolution During the First Educational Transition of Autistic Students. Qual. Res. Educ. 2021, 10, 116–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EDITEA Team. La Participación social del alumnado con autismo. Luces y sombras; UAM Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, in press.

- Hebbeler, K.; Spiker, D. Supporting Young Children with Disabilities. In The Future of Children; Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016; Starting Early: Education from PreKindergarten to Third Grade; Volume 26, pp. 185–205. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43940587 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Frederickson, N.; Dunsmuir, S.; Lang, J.; Monsen, J.J. Mainstream-special school inclusion partnerships: Pupil, parent and teacher perspectives. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2004, 8, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiati, I.; Dockrell, J.E.; Logotheti, A.E. Young children’s understanding of disabilities: The influence of development, context, and cognition. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2002, 23, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maras, P.; Brown, R. Effects of different forms of school contact on children’s attitudes toward disabled and non-disabled peers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 70, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowicki, E.A.; Sandieson, R. A metaanalysis of school-age children’s attitudes towards persons with physical or intellectual disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2002, 49, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım Hacıibrahimoğlu, B. Preschool children’s behavioural intentions towards and perceptions of peers with disabilities in a preschool classroom. Early Child Dev. Care 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Plano Clark, V.; Ivankova, N. How to use mixed methods research? understanding the basic mixed methods designs. In Mixed Methods Research: A Guide to the Field; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 105–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.C. Mixed Methods in Social Inquiry; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Quality of Inferences in Mixed Methods Research: Calling for an Integrative Framework. In Advances in Mixed Methods Research; Bergman, M.M., Ed.; SAGE Publishing: London, UK, 2008; pp. 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Mendoza, C.P. El matrimonio cuantitativo-cualitativo: El paradigma mixto. In Proceedings of the 6° Congreso de Investigación en Sexología, Villahermosa, México, 8 November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Why do Researchers Integrate/Combine/Mesh/Blend/Mix/Merge/Fuse Quantitative and Qualitative Research? In Advances in Mixed Methods Research; Bergman, M.M., Ed.; SAGE Publishing: London, UK, 2008; pp. 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. A general typology of research designs featuring mixed methods. Res. Sch. 2006, 13, 12–28. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie, C.; Tashakkori, A. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. El Diseño de la Investigación Cualitativa; Ediciones Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, R. Introducing Qualitative Research: A Student’s Guide; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Steps in Conducting a Scholarly Mixed Methods Study. 2013. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1047andcontext=dberspeakers (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, A.; Pijl, S.J.; Post, W.; Minnaert, A. Which variables relate to the attitudes of teachers, parents and peers towards students with special educational needs in regular education? Educ. Stud. 2012, 38, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balluerka, N.; Gorostiaga, A.; Alonso-Arbiol, I.; Haranburu, M. La adaptación de instrumentos de medida de unas culturas a otras: Una perspectiva práctica. Psicothema 2007, 19, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 11.0 Update, 4th ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ravens-Sieberer, U.; Gosch, A.; Rajmil, L.; Erhart, M.; Bruil, J.; Dür, W.; Auquier, P.; Poder, M.; Abel, T.; Czemy, L.; et al. KIDSCREEN. KIDSCREEN-52 medida de la calidad de vida de los niños y adolescentes. Revisión Expertos Farm. Y Result. De Investig. 2005, 5, 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- El KIDSCREEN Group Europe. Los Cuestionarios KIDSCREEN—Cuestionarios de Calidad de Vida Para los Niños y Adolescentes; Pabst Science Publishers: Lengerich, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- The KIDSCREEN Group. 2004. Available online: www.kidscreen.org (accessed on 12 March 2018).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friese, S. Qualitative Data Analysis with ATLAS. Ti; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mirete, A.B.; Belmonte, M.L.; Maquilón, J.J. Diseño, aplicación y validación de un instrumento para Valorar las Actitudes hacia la Diversidad del Alumnado (VADA). Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. Form. Del Profr. 2020, 23, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, S.; Sharma, U.; Hoffmann, L. How inclusive are the teaching practices of my German, Maths and English teachers?—Psychometric properties of a newly developed scale to assess personalisation and differentiation in teaching practices. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2019, 26, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emam, M.M.; Farrell, P. Tensions experienced by teachers and their views of support for pupils with autism spectrum disorders in mainstream schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2009, 24, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, S.; Proulx, M.; Scott, H.; Thomson, N. Exploring teachers’ strategies for including children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2014, 18, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamas, C.; Bjorklund Jr, P.; Daly, A.J.; Moukarzel, S. Friendship and support networks among students with disabilities in middle school. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 103, 101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGillicuddy, S.; O´Donnell, G.M. Teaching students with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream post-primary schools in the Republic of Ireland. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2014, 18, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nota, L.; Ginevra, M.C.; Soresi, S. School Inclusion of Children with Intellectual Disability: An Intervention Program. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2019, 44, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisham-Brown, J.; Pretti-Frontczak, K.; Hawkins, S.R.; Winchell, B.N. Addressing Early Learning Standards for All Children Within Blended Preschool Classrooms. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2009, 29, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisham-Brown, J.; Ridgley, R.; Pretti-Frontczak, K.; Litt, C.; Nielson, A. Promoting positive learning outcomes for young children in inclusive classrooms: A preliminary study of children’s progress toward pre-writing standards. J. Early Intensive Behav. Interv. 2006, 3, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agran, M.; Wojcik, A.; Cain, I.; Thoma, C.; Achola, E.; Austin, K.M.; Tamura, R.B. Participation of students with intellectual and developmental disabilities in extracurricular activities: Does inclusion end at 3: 00? Educ. Train. Autism Dev. Disabil. 2017, 52, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, G. A recipe for successful inclusive education: Three key ingredients revealed. Interacções 2014, 10, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisham-Brown, J.; Schuster, J.W.; Hemmeter, M.L.; Collins, B.C. Using an Embedding Strategy to Teach Preschoolers with Significant Disabilities. J. Behav. Educ. 2000, 10, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.D.; Schwartz, I.S. Siblings, peers, and adults: Differential effects of models for children with autism. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2004, 24, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobayed, K.L.; Collins, B.C.; Strangis, D.; Schuster, J.; Hemmeter, M. Teaching Parents to employ Mand-Model Procedures to Teach Their Children Requesting. J. Early Interv. 2000, 23, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruble, L.A.; Love, A.M.A.; Wong, V.; Grisham-Brown, J.L.; McGrew, J.H. Implementation Fidelity and Common Elements of High-Quality Teaching Sequences for Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder in COMPASS. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2020, 71, 101493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Division for Early Childhood. DEC Recommended Practices in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education. 2014. Available online: https://www.dec-sped.org/dec-recommended-practices (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Coople, C.; Bredekamp, S. (Eds.) Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth through Age 8, 3rd ed.; National Association for the Education of Young Children: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, P.N.; Shillingford, M.A.; Bryan, J. Factors Influencing School Counselor Involvement in Partnerships With Families of Color: A Social Cognitive Exploration. Prof. Sch. Couns. 2018, 22, 2156759X18814712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makin, C.; Hill, V.; Pellicano, E. The primary-to-secondary school transition for children on the autism spectrum: A multi-informant mixed-methods study. Autism Dev. Lang. Impair. 2017, 2, 2396941516684834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larcombe, T.; Joosten, A.; Cordier, R.; Vaz, S. Preparing children with autism for transition to mainstream school and perspectives on supporting positive school experiences. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2019, 49, 3073–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M.; Messiou, K. Investigación Inclusiva: Un Enfoque Innovador para Promover la Inclusión en las Escuelas. Rev. Latinoam. Educ. Inclusiva 2021, 15, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldar, E.; Talmor, R.; Wolf-Zukerman, T. Successes and difficulties in the individual inclusion of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in the eyes of their coordinators. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2010, 14, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majoko, T. Inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorders: Listening and hearing to voices from the grassroots. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 46, 1429–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segall, M.J.; Campbell, J.M. Factors relating to education professionals’ classroom practices for the inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorders. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2012, 6, 1156–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscow, M. Promoting inclusion and equity in education: Lessons from international experiences. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2020, 6, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messiou, K.; Ainscow, M. Inclusive Inquiry: Student-teacher dialogue as a means of promoting inclusion in schools. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2020, 46, 670–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, S.S.; Rice, J.; Boothe, A.; Sidell, M.; Vaughn, K.; Keyes, A.; Nagle, G. Social-Emotional Development, School Readiness, Teacher–Child Interactions, and Classroom Environment. Early Educ. Dev. 2012, 23, 919–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name (Initials) | Child’s Sex | Child’s Age at the Time of the Interviews | Type of Centre |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guille (Gil) | male | 2 | Charter |

| Nico (Nic) | male | 3 | Public |

| Lara (Lar) | female | 3 | Charter |

| Dario (Dar) | male | 3 | Public |

| Lena (Len) | female | 5 | Public |

| Ares (Are) | male | 5 | Charter |

| Name of the Student (Initials) | Professional Profile | Type of Centre |

|---|---|---|

| Guille (Gil) | Teacher | Charter |

| Nico (Nic) | Teacher | Public |

| Lana (La) | Teacher | Charter |

| Dario (Dar) | Teacher | Public |

| Lena (Len) | Teacher | Public |

| Lena (Len) | Paraprofessional | Public |

| Lena (Len) | Special education teacher | Public |

| Ares (Are) | Teacher | Charter |

| Thematic Blocks | Theme |

|---|---|

| Barriers | Lack of knowledge/lack of competences: “We need to know how to reach the students”. |

| Facilitators | Support in the face of challenges: “I want to play” |

| Peers as a factor of inclusion: “All children love him/her” | |

| The importance of working on the relationships among the students: “They become sensitive” | |

| Teachers’ willingness to learn: “I learned a lot” | |

| Partnerships with families: “They are really committed to everything” | |

| Natural classroom context: “Opportunities” |

| Items | Responses N | Reponses Positive Attitudes | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 78 | 65 | 83.3% |

| 84 | 79 | 94% |

| 85 | 68 | 80% |

| 85 | 74 | 87.1% |

| 81 | 69 | 85.2% |

| 82 | 71 | 86.6% |

| 83 | 68 | 81.9% |

| 83 | 76 | 91.6% |

| 78 | 56 | 71.8% |

| 82 | 72 | 87.8% |

| 84 | 34 | 40.5% |

| 83 | 66 | 79.5% |

| 84 | 72 | 85.7% |

| 83 | 56 | 67.5% |

| ITEMS | Group 1 | Group 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO (N/%) | YES (N/%) | NO (N/%) | YES (N/%) | |

| 8 (13.3%) | 52 (86.7%) | 3 (30%) | 7 (70%) |

| 2 (3.3%) | 58 (96.7%) | 3 (30%) | 7 (70%) |

| 9 (15%) | 51 (85%) | 7 (70%) | 3 (30%) |

| 4 (6.7%) | 56 (93.3%) | 6 (60%) | 4 (40%) |

| 58 (96.7%) | 2 (3.3%) | 3 (30%) | 7 (70%) |

| 4 (6.7%) | 56 (93.3%) | 7 (70%) | 3 (30%) |

| 3 (5%) | 57 (95%) | 10 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| 1 (1.7%) | 59 (98.3%) | 5 (50%) | 5 (50%) |

| 9 (15%) | 51 (85%) | 10 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| 3 (5%) | 57 (95%) | 6 (60%) | 4 (40%) |

| 31 (51.7%) | 29 (48.3%) | 10 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| 5 (8.3%) | 55 (91.7%) | 8 (80%) | 2 (20%) |

| 3 (5%) | 57 (95%) | 7 (70%) | 3 (30%) |

| 16 (26.7%) | 44 (73.3%) | 9 (90%) | 1 (10%) |

| TOTAL | 60 (100%) | 10 (100%) | ||

| Items | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| 79 | 92.9% |

| 65 | 76.5% |

| 82 | 96.5% |

| 78 | 91.8% |

| 68 | 80% |

| 58 | 68.2% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barrios, Á.; Cañadas, M.; Fernández, M.L.; Simón, C. It Is Never Too Early: Social Participation of Early Childhood Education Students from the Perspective of Families, Teachers and Students. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090588

Barrios Á, Cañadas M, Fernández ML, Simón C. It Is Never Too Early: Social Participation of Early Childhood Education Students from the Perspective of Families, Teachers and Students. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(9):588. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090588

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarrios, Ángela, Margarita Cañadas, Mari Luz Fernández, and Cecilia Simón. 2022. "It Is Never Too Early: Social Participation of Early Childhood Education Students from the Perspective of Families, Teachers and Students" Education Sciences 12, no. 9: 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090588

APA StyleBarrios, Á., Cañadas, M., Fernández, M. L., & Simón, C. (2022). It Is Never Too Early: Social Participation of Early Childhood Education Students from the Perspective of Families, Teachers and Students. Education Sciences, 12(9), 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12090588