Keeping Teachers Engaged during Non-Instructional Times: An Analysis of the Effects of a Naturalistic Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Inclusive, Blended Classroom Settings

1.2. Naturalistic Interventions

1.3. Social Skills Instruction

1.4. Teacher Training

1.5. Snack Talk

- What are the effects of the implementation of Snack Talk on teacher engagement with preschoolers with disabilities during mealtimes?

- What are teachers’ perceptions of the implementation of Snack Talk?

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Setting

2.1.1. Teacher Participants

2.1.2. Preschoolers Accessing Snack Talk

2.2. Materials

2.3. Behavioral Definitions and Measurement

2.4. Experimental Design

2.5. Procedures

2.5.1. Baseline Sessions

2.5.2. Teacher Training Procedures

2.5.3. Intervention Sessions

2.5.4. Follow Up

2.6. Procedural Fidelity

Interobserver Agreement (IOA)

2.7. Social Validity

3. Results

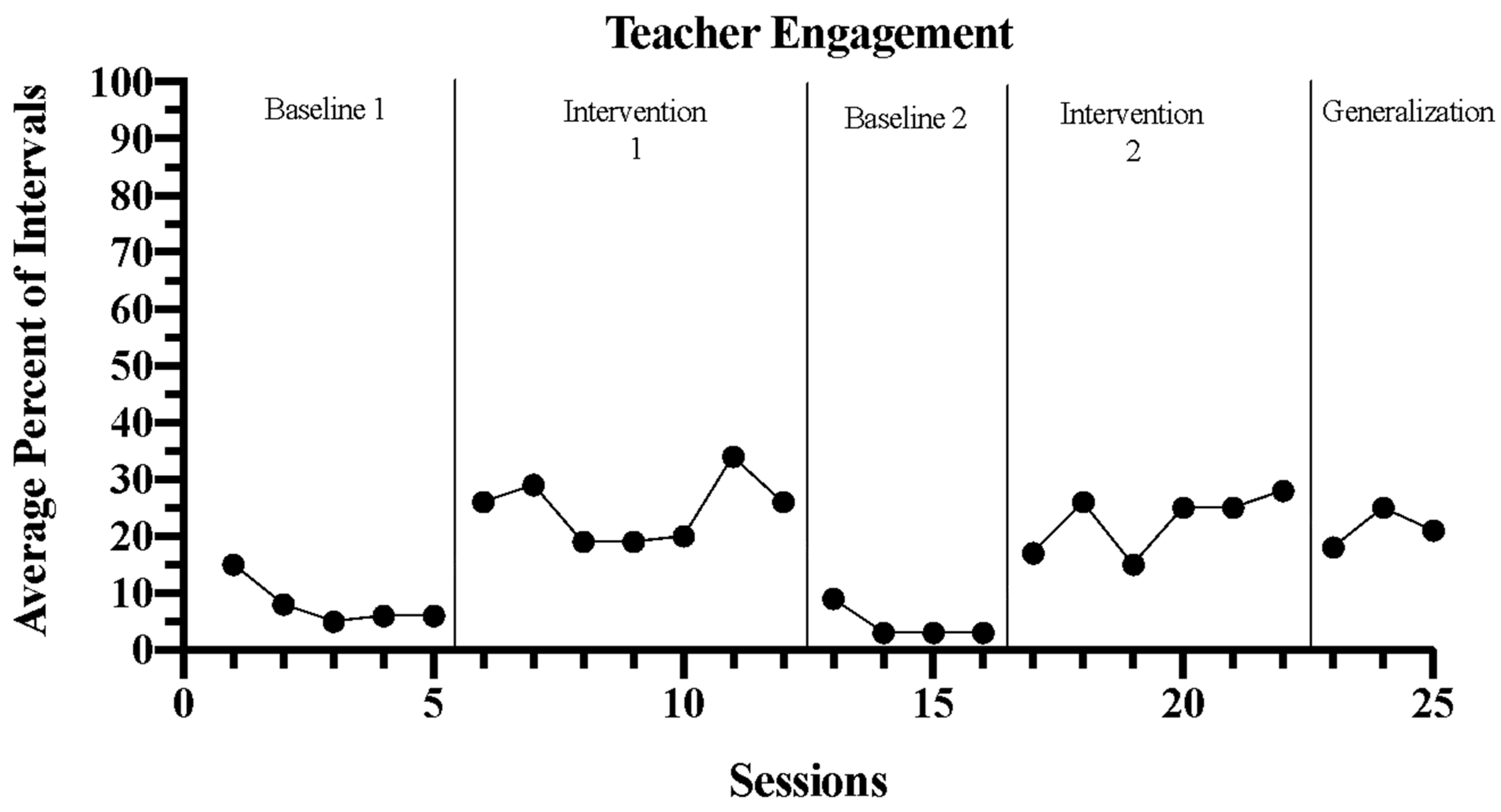

3.1. Teacher Engagement

3.2. Social Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Limitations & Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maenner, M.J.; Shaw, K.A.; Baio, J.; Washington, A.; Patrick, M.; DiRienzo, M.; Christensen, D.L.; Wiggins, L.D.; Pettygrove, S.; Andrews, J.G.; et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2020, 69, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guralnick, M.J.; Bruder, M.B. Early childhood inclusion in the United States. Infants Young Child. 2016, 29, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, S.L.; Vitztum, J.; Wolery, R.; Lieber, J.; Sandall, S.; Hanson, M.J.; Horn, E. Preschool inclusion in the United States: A review of research from an ecological systems perspective. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 2004, 4, 17–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, I.S.; Billingsley, F.F.; McBride, B.M. Including children with autism in inclusive preschools: Strategies that work. Young Except. Child. 1998, 1, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, I.S.; Ashmun, J.; McBride, B.; Scott, C.; Sandall, S.R. The DATA Model for Teaching Preschoolers with Autism; Paul, H., Ed.; Brookes Publishing Company: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Staub, D.; Schwartz, I.S.; Gallucci, C.; Peck, C.A. Four portraits of friendship at an inclusive school. J. Assoc. Pers. Sev. Handicap. 1994, 19, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, K.J.; Wilson, S.E.; Gauvreau, A.; Matthews, K.; Gucwa, M.; Therrien, W.; Mazurek, M. Visual supports to increase conversation engagement for preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder during mealtimes: An initial investigation. J. Early Interv. 2022, 45, 10538151221111762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, K.; Sam, A.; Mokrova, I.; Reszka, S.; Boyd, B.A. Facilitating social interactions with peers in specialized early childhood settings for young children with ASD. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 48, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odom, S.L. Preschool inclusion: What we know and where we go from here. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2000, 20, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, R.; Thousand, J. The Inclusive Education Checklist: A Checklist of Best Practices; National Professional Resources, Inc.: Lake Worth, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chardin, M.; Novak, K. Equity by Design: Delivering on the Power and Promise of UDL; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrenner, J.R.; Hume, K.; Odom, S.L.; Morin, K.L.; Nowell, S.W.; Tomaszewski, B.; Savage, M.N. Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults with Autism; FPG Child Development Institute: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen-Sandfort, R.J.; Whinnery, S.B. Impact of milieu teaching on communication skills of young children with autism spectrum disorder. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2013, 32, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, G.G.; Daly, T. Incidental teaching of age-appropriate social phrases to children with autism. Res. Pract. Pers. Sev. Disabil. 2007, 32, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koegel, R.L.; Koegel, L.K. Pivotal Response Treatments for Autism: Communication, Social, & Academic Development; Paul, H., Ed.; Brookes Publishing Company: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Suhrheinrich, J. Training teachers to use pivotal response training with children with autism: Coaching as a critical component. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 2011, 34, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmeter, M.L. Classroom-based interventions: Evaluating the past and looking toward the future. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2000, 20, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretti-Frontczak, K.; Bricker, D. An Activity-Based Approach to Early Intervention; Brookes Publishing Company: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- VanDerHeyden, A.M.; Snyder, P.; Smith, A.; Sevin, B.; Longwell, J. Effects of complete learning trials on child engagement. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2005, 25, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolery, M.; Hemmeter, M.L. Classroom instruction: Background, assumptions, and challenges. J. Early Interv. 2011, 33, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, P.A.; Rakap, S.; Hemmeter, M.L.; McLaughlin, T.W.; Sandall, S.; McLean, M.E. Naturalistic instructional approaches in early learning: A systematic review. J. Early Interv. 2015, 37, 69–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlop, M.H.; Lang, R.; Rispoli, M. Lights, Camera, Action! Teaching Play and Social Skills to Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder through Video Modeling. In Play and Social Skills for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 71–94. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-72500-0_5 (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Bellini, S.; Peters, J.K.; Benner, L.; Hopf, A. A meta-analysis of school-based social skills interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2007, 28, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresham, F.M.; Sugai, G.; Horner, R.H. Interpreting outcomes of social skills training for students with high incidence disabilities. Except. Child. 2001, 67, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, K.J.; Wilson, S.E.; Ingvarsson, E.; Doucette, J.; Therrien, W.; Nevill, R.; Mazurek, M. Snack Talk: Effects of a Naturalistic Visual Communication Support on Increasing Conversation Engagement for Adults with Disabilities. In Behavior Analysis in Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–15. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40617-023-00775-3 (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Harjusola-Webb, S.M.; Robbins, S.H. The effects of teacher-implemented naturalistic intervention on the communication of preschoolers with autism. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2012, 32, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warlaumont, A.S.; Richards, J.A.; Gilkerson, J.; Oller, D.K. A social feedback loop for speech development and its reduction in autism. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 1314–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, S.F.; Gilkerson, J.; Richards, J.A.; Oller, D.K.; Xu, D.; Yapanel, U.; Gray, S. What automated vocal analysis reveals about the vocal production and language learning environment of young children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2010, 40, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgeland, J.; Bruce, M.; Harihan, A. The Missing Piece: A National Survey on How Social and Emotional Learning Can Empower Children and Transform Schools; Civic Enterprises: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins, N.; Higgins, K.; Pierce, T.; Tandy, R.D.; Tincani, M. An analysis of social skills instruction provided in teacher education and in-service training programs for general and special educators. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2010, 31, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinsser, K.M.; Christensen, C.G.; Torres, L. She’s supporting them; who’s supporting her? Preschool center-level social-emotional supports and teacher well-being. J. Sch. Psychol. 2016, 59, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brian, M.; Stoner, J.; Appel, K.; House, J.J. The first field experience: Perspectives of preservice and cooperating teachers. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 2007, 30, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potthoff, D.; Alley, R. Selecting placement sites for student teachers and pre-student teachers: Six considerations. Teach. Educ. 1996, 32, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, I.P.; Day, B.D. Early field experiences in preservice teacher education: Research and student perspectives. Action Teach. Educ. 1999, 21, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiman-Nemser, S. From Preparation to Practice: Designing a Continuum to Strengthen and Sustain Teaching. Occas. Pap. Ser. 2000, 2000, 1013–1055. Available online: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series/vol2000/iss5/1 (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Jones, V.; Dohrn, E.; Dunn, C. Creating Effective Programs for Students with Emotional and Behavior Disorders; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, W.H.; Odom, S.L.; Conroy, M.A. An intervention hierarchy for promoting young children’s peer interactions in natural environments. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2001, 21, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, C.E.; Beals, D.E. Mealtime talk that supports literacy development. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2006, 2006, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, S.L. Teacher–child conversation in the preschool classroom. Early Child. Educ. J. 2004, 31, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, P.S.; Schwartz, I.S.; Barton, E.E. Providing interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorders: What we still need to accomplish. J. Early Interv. 2011, 33, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, K.J.; Wilson, S.E. Supporting diverse learners with autism through a culturally responsive visual communication intervention. Interv. Sch. Clin. 2021, 56, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauvreau, A.N. Using “Snack Talk” to support social communication in inclusive preschool classrooms. Young Except. Child. 2017, 20, 187–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, D.M.; Wolf, M.M.; Risley, T.R. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1968, 1, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greer, D.R.; Ross, D. Verbal Behavior Analysis: Inducing and Expanding Complex Communication in Children with Severe Language Delays; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, T.F.; Baer, D.M. An implicit technology of generalization 1. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1977, 10, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, T.F.; Fowler, S.A.; Baer, D.M. Training preschool children to recruit natural communities of reinforcement. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1978, 11, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, J.R.; Lane, J.D.; Gast, D.L. Dependent Variables, Measurement, and Reliability. In Single Case Research Methodology: Applications in Special Education and Behavioral Sciences; Ledford, J.R., Gast, D.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 97–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ledford, J.R.; Gast, D.L. (Eds.) Single Case Research Methodology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Severini, K.E.; Gast, D.L.; Ledford, J.R. Withdrawal and Reversal Designs. In Single Case Research Methodology: Applications in Special Education and Behavioral Sciences; Ledford, J.R., Gast, D.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 213–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill, T.R.; Hitchcock, J.H.; Horner, R.H.; Levin, J.R.; Odom, S.L.; Rindskopf, D.M.; Shadish, W.R. Single-case intervention research design standards. Remedial Spec. Educ. 2013, 34, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.B.; Rollyson, J.H.; Reid, D.H. Evidence-based staff training: A guide for practitioners. Behav. Anal. Pract. 2012, 5, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.O.; Heron, T.E.; Heward, W.L. Applied Behavior Analysis, 2nd ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, J.; de Courcy, K. The Pandemic Has Exacerbated a Long-Standing National Shortage of Teachers; Economic Policy Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Participants | Baseline 1 (Range) | Intervention 1 (Range) | Baseline 2 (Range) | Intervention 2 (Range) | Generalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corey | 98% (97–100) | 89% (87–92) | 99% (98–100) | 93% (90–97) | 92% |

| Marie | 93% (85–100) | 88% (87–93) | 90% (93–93) | 88% (83–93) | 93% |

| Jonathan | 100% | 85% (83–87) | 100% | 92% (92–92) | 90% |

| Claire | 97% (95–98) | 91% (88–93) | 98% (97–98) | 100% | 97% |

| Justin | 97% | 93% (92–95) | 98% (98–98) | 94% (92–97) | 92% |

| Social Validity Questions | Average Rating |

|---|---|

| 5 |

| 4 |

| 4.75 |

| 4.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bateman, K.; Wilson, S.E.; Matthews, K.; Gauvreau, A.; Gucwa, M.; Therrien, W.J.; Nevill, R.; Mazurek, M. Keeping Teachers Engaged during Non-Instructional Times: An Analysis of the Effects of a Naturalistic Intervention. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13060534

Bateman K, Wilson SE, Matthews K, Gauvreau A, Gucwa M, Therrien WJ, Nevill R, Mazurek M. Keeping Teachers Engaged during Non-Instructional Times: An Analysis of the Effects of a Naturalistic Intervention. Education Sciences. 2023; 13(6):534. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13060534

Chicago/Turabian StyleBateman, Katherine, Sarah Emily Wilson, Katherine Matthews, Ariane Gauvreau, Maggie Gucwa, William J. Therrien, Rose Nevill, and Micah Mazurek. 2023. "Keeping Teachers Engaged during Non-Instructional Times: An Analysis of the Effects of a Naturalistic Intervention" Education Sciences 13, no. 6: 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13060534

APA StyleBateman, K., Wilson, S. E., Matthews, K., Gauvreau, A., Gucwa, M., Therrien, W. J., Nevill, R., & Mazurek, M. (2023). Keeping Teachers Engaged during Non-Instructional Times: An Analysis of the Effects of a Naturalistic Intervention. Education Sciences, 13(6), 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13060534