Abstract

This study utilized a brief coaching package to train parents to support their children’s language development in home environments. Two parents of dual language learners were trained to use naturalistic language strategies that ranged in complexity. Parents participated in individual training sessions targeting three strategies: narration, imitation, and environmental arrangement and responding. A multiple baseline design across behaviors replicated across parent–child dyads was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the brief coaching package. Therapeutically accelerating data in a baseline condition affected interpretation of results for one dyad, while the package demonstrated effectiveness for the other dyad. Concomitant increases in children’s use of English language during sessions was also observed. Multi-level models were used to estimate the moderating effect of parent engagement in naturalistic language strategies on children’s vocal initiations. Implications for home-based service providers are presented.

1. Introduction

For young children with or at-risk for delays or disability, obtaining early access to appropriate types and dosages of services is critical for ensuring later success in school [1]. In early childhood education, a blended practices framework [2] provides multi-tiered assessments and instructions to align educator services to match the needs of each child. Three tiers of support are included in the blended practices framework. In Tier 1 of the framework, universal interventions address the shared and common needs of all children; in Tier 2 targeted interventions support the specific needs of some children; and in Tier 3 intensive interventions are used to address children’s individualized needs. By providing services within a tiered support system, educators can increase the likelihood that their children are receiving the appropriate types of interventions, and that the interventions are being provided at appropriate dosages to address children’s needs.

Across the United States, there are challenges to providing multi-tiered supports, as the percentage of children that qualify for these services has consistently increased over the last 20 years with the average amount of funding per child having decreased over the same time period [3]. Given the misalignment between resources and the amount of children needing services, providers of early intervention and early childhood special education often employ a family-centered approach to service provision, whereby parents and caregivers have increasingly been expected to serve as primary interventionists who can implement developmentally appropriate practices with fidelity [4].

Studies evaluating parents as interventionists have consistently identified that parents can learn to implement practices with fidelity and produce meaningful improvement in their children’s development [5,6]. In order for frontline practitioners (e.g., home-based service providers) to successfully replicate the results of research studies, it is necessary that the types of training practices and dosages at which the practices are provided be feasible within the service provision models that practitioners routinely operate. For example, Part C service providers have, on average, 4 h of contact with families per month [7]. If research-based parent trainings differ significantly with regard to the amount of contact hours required, then practitioners would need to carefully consider the feasibility of using such a model for preparing parents to serve as interventionists for their children. We identified only one review of parent implemented interventions that discussed the number of hours of training received parents, and 90% of reporting studies required at least 12 h of parent training [8]. This review did not report on how these hours were distributed (e.g., over two sessions each occurring within one week of the other). Considerations about both the number of hours and the distribution of those hours is needed when determining the feasibility of having practitioners effectively prepare parents to provide multi-tiered interventions to meet young children’s needs.

In two recent studies, a brief coaching package was evaluated across adult-child dyads within single-case experimental designs [9,10]. The dosage of this coaching package mirrored common dosages provided through Part C early intervention services (i.e., both total hours of training and the distribution of those hours). In past applications, the package consisted of three 1 h contacts with each adult-child dyad, during which adults were trained on different tiered intervention practices (i.e., environmental arrangement strategies [Tier 3], narration [Tier 1], and imitation [Tier 1]). An instructional coach provided adults with (a) a rationale for using a target behavior, (b) a handout discussing procedures for implementing the target behavior, (c) a video model of the target behavior, and (d) discussed how the adult could use the target behavior during play with their child. Adults then practiced using a target behavior with their child across 4 min sessions while the coach provided in-vivo prompting and reinforcement. After each session the coach provided performance-based feedback to adults for approximately 3 min. Following the provision of performance-based feedback, adults engaged in increased uses of parent target behaviors and children displayed concomitant increases in target behaviors. The previous studies were conducted in a university-based clinic [10] and in a Guatemalan orphanage [9] with parents and orphanage staff serving as participants. Children in both studies displayed developmental delays related to expressive communication. The purpose of the present study was to systematically replicate the brief parent coaching package in home environments with dual language learners (DLLs).

For young children with typical development who are native English speakers, they commonly learn to effectively communicate with adults and peers, with relatively few challenges during early interactions. If challenges arise, adults typically scaffold interactions until children are successful, removing supports as children display more advanced forms of communication. In contrast, a number of young children in the United States are learning English as a second language, while still acquiring their native language (i.e., DLLs). For children who are DLLs, early childhood can be a difficult period as they must acquire school readiness skills while learning to speak their native language at home and a new language at school [11]. Due to the myriad of skills DLLs must acquire in early childhood, many children are at risk for disproportionally poorer outcomes than their same-age peers [12]. Educational policies have sought to address the challenges facing DLLs within the recent provisions of the Every Student Succeeds Act [13]. These provisions stress the importance of early intervention services for the purpose of remediating delays prior to a child receiving special education services [14]. To remediate delays and prevent long-term communication and language-related difficulties in DLLs, involving families in blended practices and teaching them to use tiered early interventions may be critical to improve parents’ confidence and competence in supporting their children’s individual developmental needs [15]. Given the need to identify feasible parent training models that may be effective for remediating the delays of young children, such as those displayed by DLLs, the purpose of this study was to replicate a brief coaching package with parents of DLLs in home environments. The following research questions guided the study:

1. Is a brief coaching package functionally related to increases in parents’ use of tiered naturalistic language strategies?

2. What are the effects of parent engagement in naturalistic language strategies on the expressive communication behaviors of young DLLs?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Two parent–child dyads were recruited from the research team’s local community by sharing information of this study with two churches located in a city in the southeastern United States. Ann was a Romanian immigrant with a master’s degree in French, and her first language was Romanian. She was a homemaker in her 40 s. The primary language spoken at her home was English. Her son, Lee, was a 40-month-old boy who was adopted abroad when he was 26 months old. Lee’s first language was Mandarin. Assessments conducted during his international adoption check-ups indicated speech delay, developmental delay, and heart disease. He received no services related to his language development. Lee displayed many age-appropriate play and communication skills, such as assigning absent attributes to objects and using three-word vocal phrases. His parents and siblings indicated that they understood his speech; however, the family’s main concern was the consistency with which Lee used vocal speech, specifically around interactions with his family such as initiating a conversation or requesting. Ann described Lee as being “too quiet for a 3-year-old boy”. Lee stayed home with his mother during the day and did not attend daycare or preschool. This household included 3 older siblings. Lee’s father, who did not participate in this study, was a full-time employee at a local church.

The second dyad included Yan and her son Easton. Yan was a Chinese immigrant with a master’s degree in anthropology; her first language was Mandarin. She was a home maker in early 30 s. Easton was a 46-month-old boy with no identified delays, but teachers in his classroom had strongly suggested his communication skills in English language needed extra support at home. He attended a tuition-based preschool 5 days a week. While at home, he communicated with his family in Chinese and at school he used English. Parents did not have concerns about Easton’s use of Chinese to communicate; however, Easton’s preschool teacher indicated that his communication skills in both receptive and expressive English language were under-developed compared to his English-speaking peers, and such disadvantage had impacted his classroom participation. Given that Easton’s family did not speak English at home and the concerns expressed by his preschool teacher, his mother sought participation in the study to acquire skills that could be used to promote Easton’s communication skills in English at home. This household had 1 younger sibling, a grandparent, and Easton’s father was a researcher at a local university.

2.2. Setting

All sessions took place in the children’s homes in areas where families typically engaged in child-led activities (e.g., playing with trains in the family room, reading books in the child’s bedroom). A variety of age-appropriate toys from each child’s home was used during all sessions (e.g., blocks, cars, ball, toy figures). For Lee, at least one sibling was present during all sessions. For Easton, siblings and grandparents were present during some sessions; they observed sessions but did not participate in trainings. Sessions for each dyad took place during 1-h visits occurring once per week for five weeks across two months. The first author served as video recorder, in vivo data collector, and instructional coach throughout the study.

2.3. Data Collection and Measurement

Each session lasted 4 min, with multiple sessions occurring per home visit. The number of sessions occurring for each of the five home visits varied based on parent performance or family circumstances. For example, in one visit, sessions were stopped after three sessions for Easton and Yan due to challenging behavior exhibited by a sibling that required Yan’s attention. During each home visit, data were initially collected in vivo by the first author to inform experimental decisions, but later recorded via video recordings for reliability purposes. For example, if a parent mastered a target behavior at the beginning of a visit, then the instructional coach could begin training on a new target behavior during that same visit; all sessions would later be coded via video recordings. The mastery criterion for each target behavior was at least four occurrences per session (i.e., an average of one occurrence per minute) across three consecutive sessions. This mastery criterion was informed by recommendations from similar research [10,16].

When coding videos, occurrences of behaviors were measured using time-stamped event recording [17]; when a target behavior occurred, the occurrence was marked, along with a time stamp of occurrence. All data on target behaviors reported in this manuscript reflect data recorded through video recordings. The three target behaviors for parents were (a) narration, (b) imitation and (c) environmental arrangement and responding (EAR). Target behaviors for children were initiations; initiations were selected to reflect the family’s goals for their child (i.e., increased vocal speech initiations using English language). Parents communicated with children in English in all baseline, intervention, and maintenance sessions.

2.4. Parent Behaviors

Targeted parent behaviors aligned with different tiers of support that may be needed to adequately address the needs of the child participants. The purpose of narration and imitation was to promote positive parent–child interactions and support development of general, universal communication outcomes (i.e., Tier 1). Narration and imitation are often considered as helping set the stage for more intensive or complex language interventions, such asenvironmental arrangement and responding (EAR), which is often considered a Tier 3 strategy.

Narration. Play narration referred to a parent describing in English the movements and actions of their child during play [10] The described movements and actions could pertain to what the child was doing or the movements and actions of a toy that the child was manipulating. Examples included “running fast” and “that plane is flying high”. Each occurrence of narration needed to be separated by at least 1 s. The instructional coach recommended that parents use 2–5 words within a narration phrase as this approximated the children’s level of language development.

Imitation. Correct imitation involved the parent reproducing their child’s play actions with same, similar, or pretend materials [10]. Occurrences of imitation were recorded when (a) there was 1 s separating a parent’s imitated actions, (b) the action being imitated changed based on the child’s play, or (c) the materials used to imitate the child’s play changed. In addition, for imitation to occur, the play action being imitated must have been initiated by the child. Lastly, each occurrence needed to last longer than 1 s and the child needed to be engaged in the same action for that 1 s (i.e., the parent and child needed to be simultaneously engaged in the same play action for at least 1 s). For example, a single occurrence of imitation was marked as occurring if the child began driving a toy truck, then the parent pretended to drive a toy cup as if it were a truck, and both the child and parent were engaged in driving actions at the same time for at least 1 s. If the parent switched from driving a cup to driving a block while the child was still driving the truck, then this would be scored as a second occurrence of imitation.

Environmental arrangement and responding (EAR). EAR required the parent to control access to preferred items or activities and respond contingently to a child’s request. Steps for EAR included (a) controlling access to materials, (b) waiting up to 3 s for child to vocalize, (c) providing a 2–5 word English language model if the child demonstrated interest in the materials but did not vocalize, (d) waiting up to 3 s for the child to imitate the vocal model, (e) giving the child access to the toy because the child imitated the model or indicated continued interest in the item (i.e., after 3 s with no response, the adult gave the child the item and modeled the target phrase), or (f) removing the object if the child lost interest (e.g., oriented away from the adult, playing with another item; [10]). A parent needed to complete all necessary steps for an occurrence of EAR to be recorded. If any step was not completed correctly then an occurrence was not recorded. If a child provided an independent vocal request in English following an environmental arrangement, then the parent did not need to engage in the prompting steps, and an occurrence of EAR was recorded if the parent engaged in all other steps correctly.

2.5. Child Behavior

Initiations were defined as a child’s intelligible vocal attempt to communicate in English, independent of a parent’s vocalization. Initiations were not scored if they occurred in response to a parent presented question or if they occurred within 4 s of a parent’s comment (i.e., parent word or phrase that had semantic meaning). Parent exclamations and environmental sounds were not considered comments. At least 2 s needed to separate each initiation, and initiations needed to contain at least one intelligible English language word.

2.6. Experimental Design and Data Analysis

A single-case multiple-baseline design across behaviors, replicated across two parent–child dyads was used to evaluate the effects of a brief coaching package to teach parents to use naturalistic language strategies [17,18]. Changes in child behaviors were measured concurrently with parent behaviors; however, experimental decisions were based on parent behaviors and, as such, changes in child behavior lack adequate experimental control to assess presence or absence of a functional relation. The multiple-baseline design allowed for a dichotomous determination regarding the relation between the independent and dependent variable; specifically, is our brief coaching package functionally related to increases in parents’ use of tiered naturalistic language strategies? Rigor of the single-case designs was evaluated across elements detailed by Ledford and Gast [17]: (a) data reliability and (b) data sufficiency. Within each design, parent data were visually analyzed with consideration of level, trend, stability, overlap, consistency of effect, and immediacy of effect, as well as vertical analysis of data.

To estimate the association between parent engagement in naturalistic language strategies on children’s initiations, we created multi-level models using a time series analysis framework specific for analyzing data collected within single-case experimental designs (see [19]). All models were created in Stata version 16.0; syntax for all models is available for use and review upon request. The first level of the models reflects each measurement occasion (i.e., session), and the second level reflects each single-case design (i.e., parent–child dyad). Four continuous predictor variables were included throughout the models. Sessions indicated each measurement occasion, Narrations indicated the number of narrations performed by parent, Imitations indicated the number of imitations implemented by a parent, and EAS indicated the number of times a parent engaged in an EAS. The outcome variable for each model was the number of initiations that a child engaged in throughout a session (Initiations). Five models were created. Model 1 contained only the Sessions variable, as this provided an estimate of the linear trend present in the children’s initiations throughout the study. The Sessions variable was retained in all created models as a control for the trend present in the data. Models 2–4 contained the other predictor variables, with each entered individually, along with the Sessions variable. These models provided an estimate of the association between parent engagement in each instructional strategy and child initiations when controlling for the trend in child data. The final model (Model 5) contained all predictor variables and provided an estimate of the association between parent engagement in each instructional strategy and child initiations when controlling for the trend in child data and parent engagement in each instructional strategy. Based on recommendations from Ferron et al. (2009) [20], first-order autoregressive model was used to model the first level error structure in each model. Although included in the framework discussed by Declercq et al. (2020) [19], we did not model each predictor variable as a random effect due to a lack of variance attributable to the second level of the models, which resulted in our software program failing to report variance statistics; average estimates of effect were unchanged regardless of including predictor variables as random effects.

The formula for Model 5 is below. Subscript s indicates each session and subscript d indicates each design. The first level error term was indicated by r and the second level error term by u.

2.7. Conditions

Baseline sessions. Prior to introducing the coaching package, baseline sessions were conducted. Before the start of each baseline session, the instructional coach asked parents to play with their child as they typically would using the toys and materials present in the family’s home. The instructional coach observed and video recorded each session, but did not provide any prompting or feedback. A minimum of three sessions were conducted with each dyad until data were stable.

Coaching sessions. Following baseline sessions, parents were taught three naturalistic language strategies, one at a time and in a prescribed order by the instructional coach. Once the parent met the mastery criterion for a one strategy, training began on the next strategy. The brief coaching packaged employed a cyclical sequence of components to train the parents.

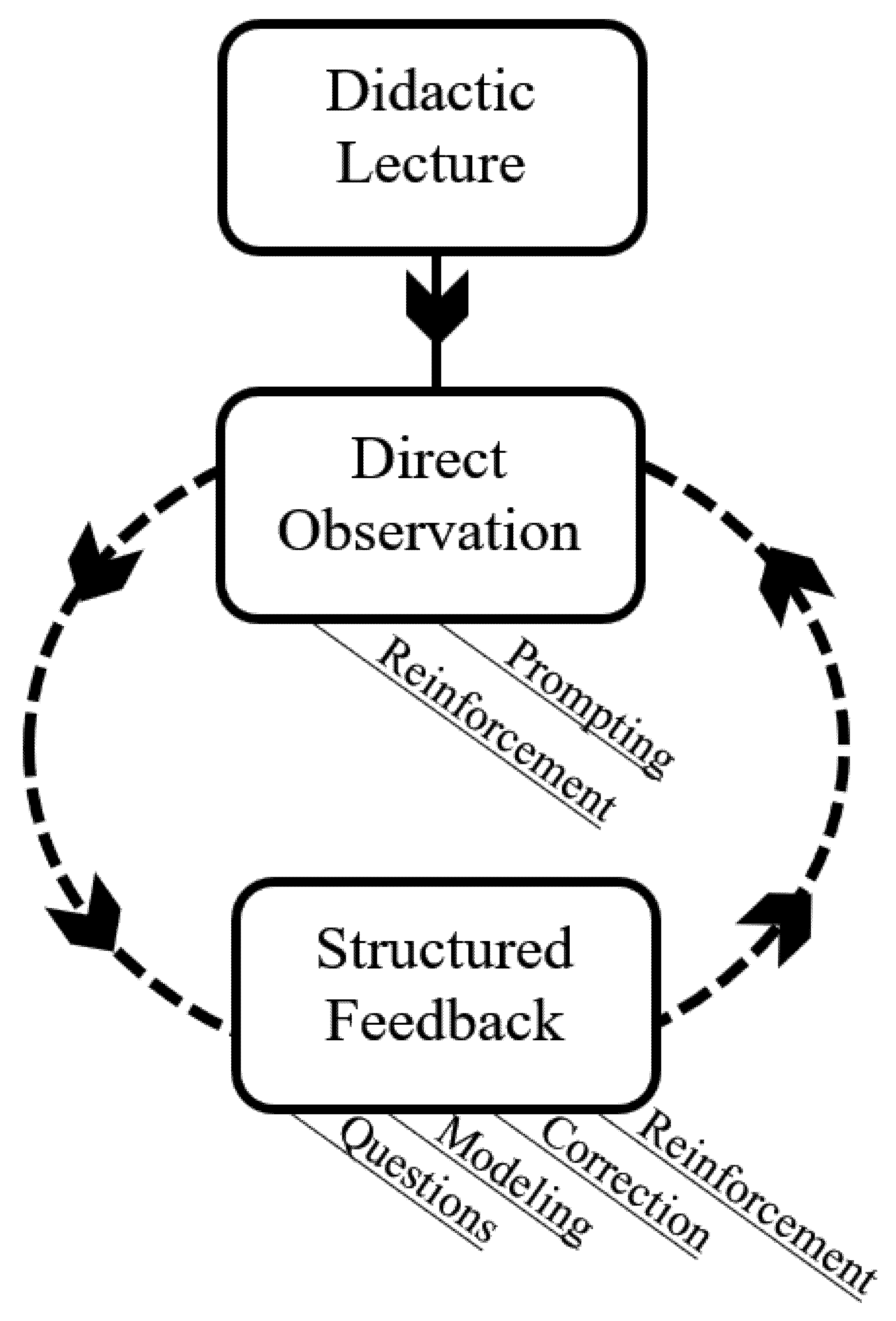

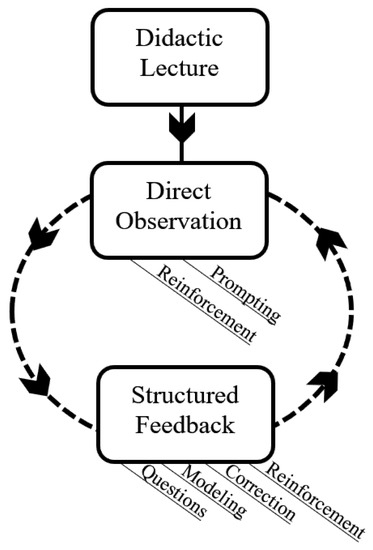

Initially, the instructional coach provided a brief didactic lecture lasting 2–3 min. Within the lecture, the coach (a) provided a rationale on a target naturalistic language strategy, (b) showed video examples of the target behavior occurring, (c) talked through a handout describing how the behavior could be used during play, and (d) allowed time for the parent to ask questions.

Following the didactic lecture, 4 min sessions were conducted in a manner similar to the baseline condition, in which the parent played with child using toys available in the home. In addition, the instructional coach provided (a) prompting to highlight opportunities when the target instructional strategy could be used (e.g., “now is a good time to hold on to what he wants.”) and (b) praise to indicate when the parent correctly used the target instructional strategy (e.g., “good job describing that car!”).

After each session, the instructional coach engaged in a structured sequence of feedback behaviors with the parent. The structured feedback consisted of (a) praising specific occurrences of the parent engaging in the target behavior, (b) highlighting missed opportunities or changes that the parent should make when using the strategy, (c) providing an opportunity to watch a video model of the target behavior, and (d) asking if the parent had any questions.

Following the provision of feedback, the parent conducted another 4 min session with the child. Sessions followed by feedback continued until the end of a home visit or when an instructional strategy was mastered. See Figure 1 for a depiction of the sequence of training components used to target each instructional strategy.

Figure 1.

Sequence of training components within the brief coaching package.

Maintenance and no-coaching probe sessions. Following mastery of narration and imitation, a no-coaching probe session occurred; and maintenance sessions occurred after the parent mastered a target behavior. Maintenance and no-coaching probe sessions were identical to baseline sessions in that the instructional coach provided no prompting or feedback. The final three maintenance sessions for each parent–child dyad occurred one week after mastering all target behaviors.

3. Results

3.1. Rigor

Reliability. The second author served as the reliability data collector for dependent variables (i.e., interobserver agreement [IOA]) and the procedural fidelity (PF) data collector for independent variables. The data collector was not blind to study conditions when coding. All data were collected from video recordings of coaching and sessions. Time-stamps were used to indicate agreements; that is, each data collector’s time-stamp needed to be within 3 s of one another for an agreement to occur. Any data collector’s time-stamp that was not within 3 s of the other data collector’s time-stamp was scored as a disagreement. Reliability percentages were calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements plus disagreements and multiplying by 100. Prior to beginning data collection, the primary data collector (i.e., first author) reviewed the definitions of the target behaviors with the reliability data collector. The data collectors coded three videos for practice purposes and compared their data to ensure adequate reliability. Data collectors were above 80% reliability on all target behaviors following each practice video.

At least 25% of sessions in each condition for each parent–child dyad were coded for IOA and PF. IOA and PF were collected for 34.9% of all sessions; 36.8% of Ann and Lee sessions and 33.3% of Yan and Easton’s sessions. With the exception of Ann’s narration during the maintenance condition, mean IOA on each behavior for each parent and child ranged from 80.0–100.0% in each condition. Mean IOA on Ann’s narration during the maintenance condition was 60.6% (range 50.0–81.8%). As discussed in other studies measuring free-operant communication behaviors (e.g., [21]), low occurrences of behaviors can influence IOA within a condition. Mean IOA for each child’s initiation behavior was 97.4% (range 81.8–100.0%) and 92.7% (66.7–100.0%) for Lee and Easton, respectively. Refer to Table 1 for detailed data on Ann and Yan’s reliability percentages across each condition. With regard to baseline and intervention conditions only, these reliability data meet contemporary framework standards for single-case designs (e.g., [18]).

Table 1.

Means and ranges of interobserver agreement data for Ann and Yan across all conditions.

PF was collected for behaviors the instructional coach planned to engage in during each session and during parent training. Planned behaviors during baseline and maintenance sessions included (a) answering parent questions and (b) providing no feedback. During the didactic lectures, planned behaviors included (a) providing a rationale, (b) showing a video model, (c) reviewing the handout, (d) allowing the parent to ask questions. During training sessions planned behaviors included: (a) prompting and (b) praising parents. During the provision of feedback planned behaviors included: (a) praising a specific occurrence of the target behavior, (b) providing suggestions on how to improve the parent’s use of the target behavior, (c) providing an opportunity to watch a video model of the target behavior, and (d) allowing the parent to ask questions. Across the entire study, one PF error occurred due to the instructional coach not adequately describing a correctly implemented target behavior during the provision of feedback; in one of Yan’s sessions the coach described the parent’s use of the strategy in general terms rather than discussing a specific occurrence of the strategy. These procedural fidelity data meet contemporary framework standards for single-case designs (e.g., [18]); however, it should be noted that the primary and secondary data collectors for this study were not blind to study conditions.

Data sufficiency. Each of the two designs allows for three attempts to demonstrate an effect at three points in time. A minimum of three data points was collected in each baseline, training, and maintenance condition within each design. The coaching package was never introduced in a subsequent tier until a mastery criterion was reached in a previous tier. In the first tier of Ann’s design, her narration data reflect a therapeutic accelerating trend, suggesting the presence of a potential threat to internal validity (e.g., testing, history). Despite no other tiers in Ann’s design replicating this threat (i.e., baseline data in other tiers were stable prior to the introduction of the training), we are unable to evaluate Ann’s design for the presence of a functional relation. In Yan’s design, baseline data were stable throughout all tiers prior to the introduction of the training. We perceive the data in Yan’s design as sufficient according to contemporary design standards to evaluate the presence of a functional relation (e.g., [18]).

3.2. Effects

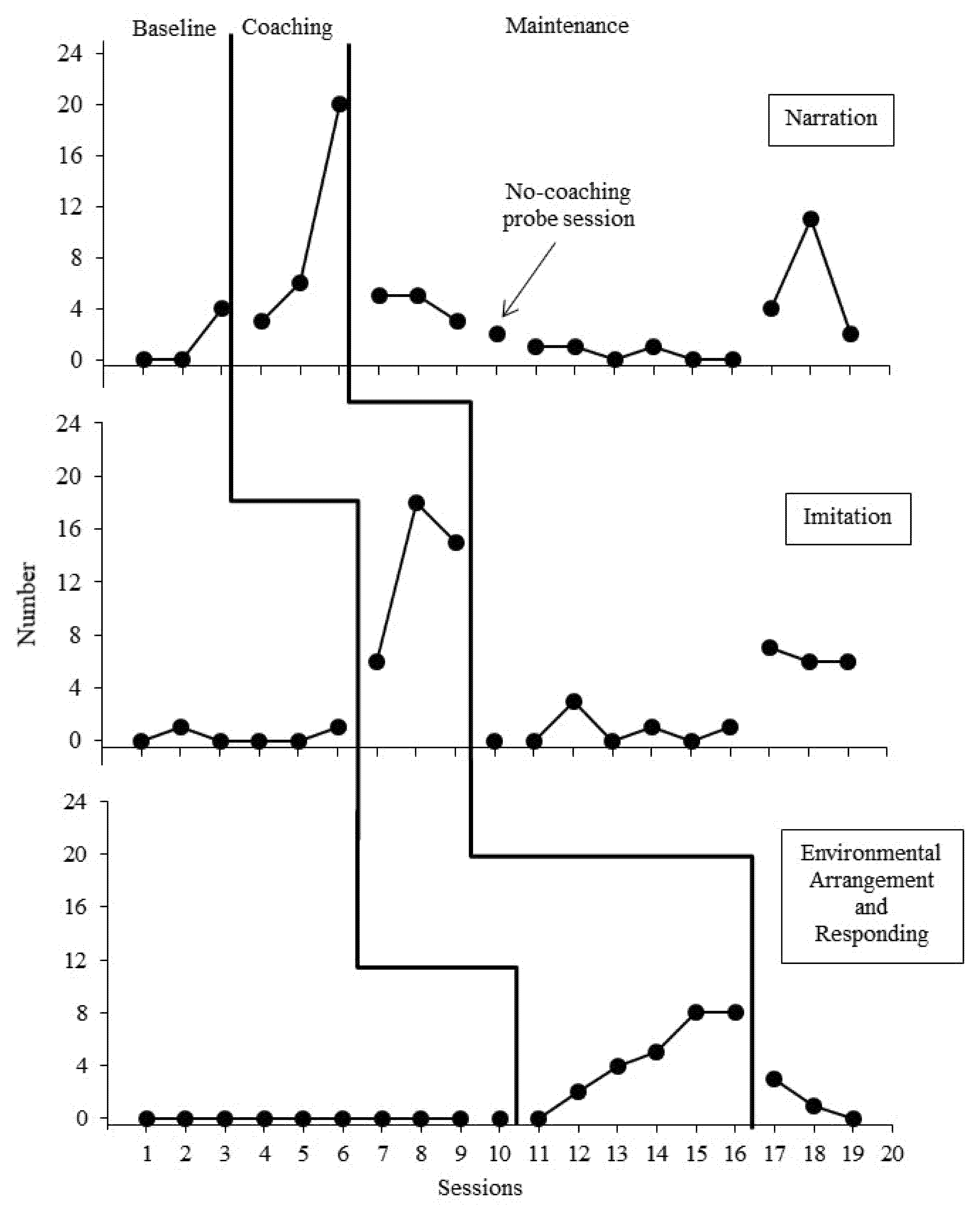

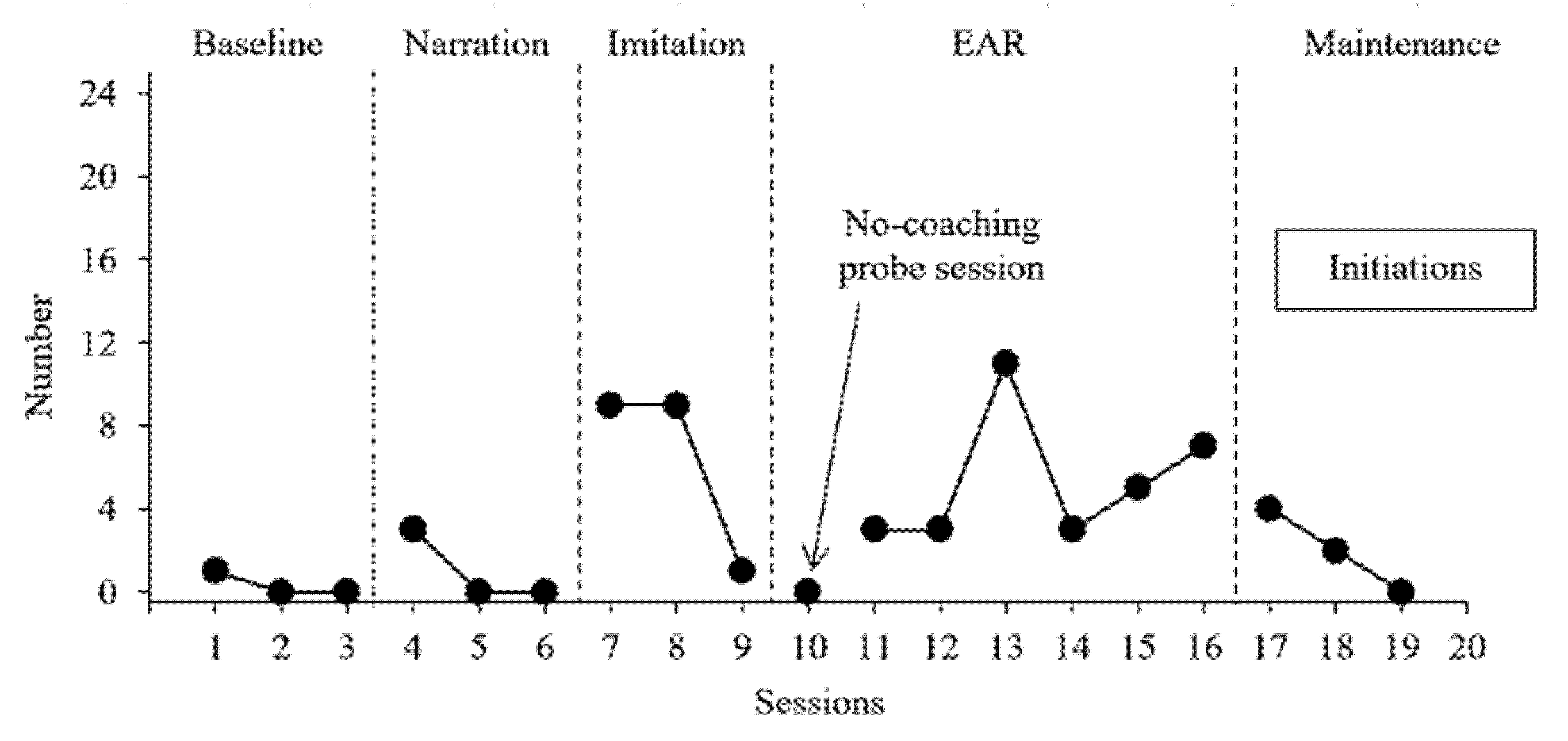

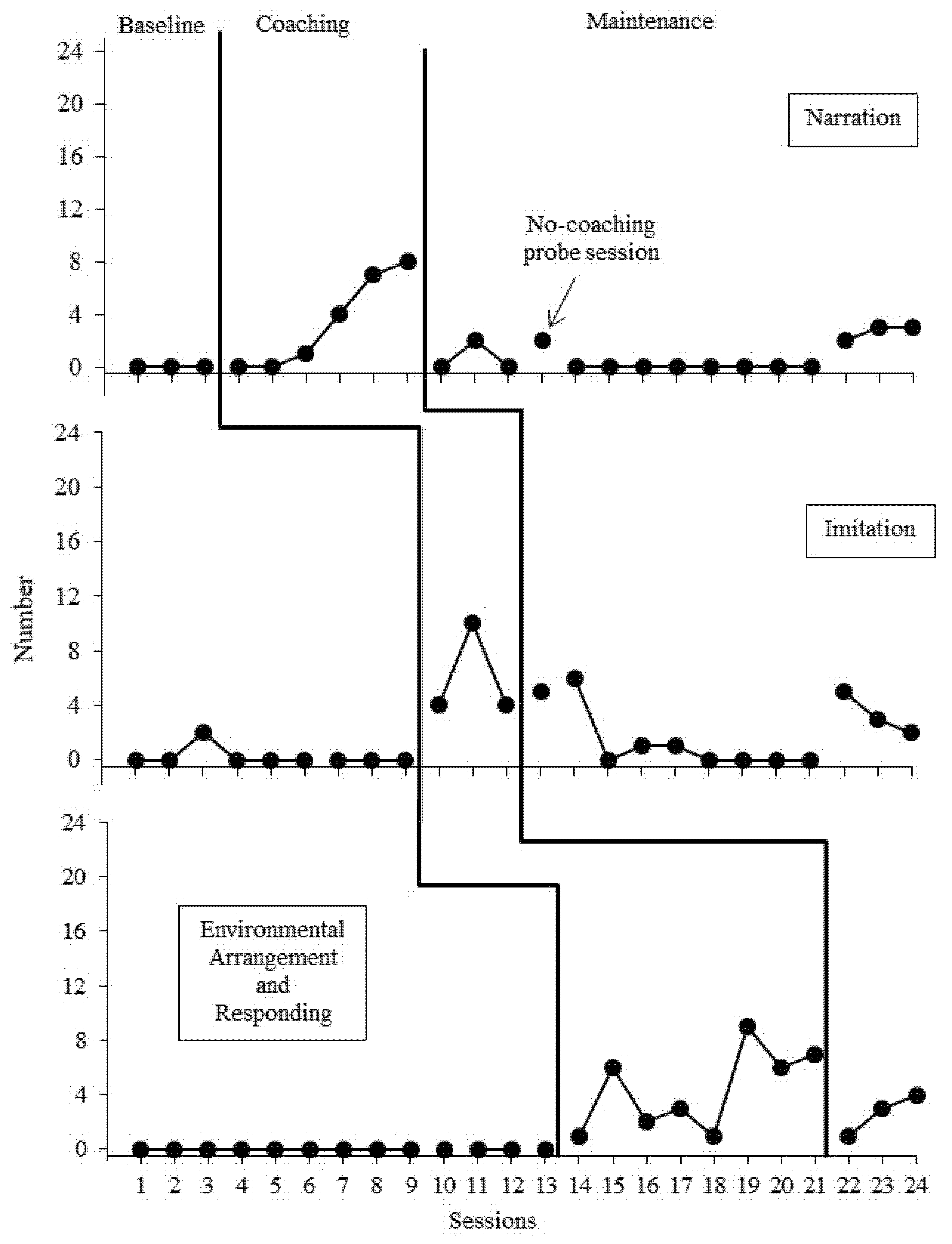

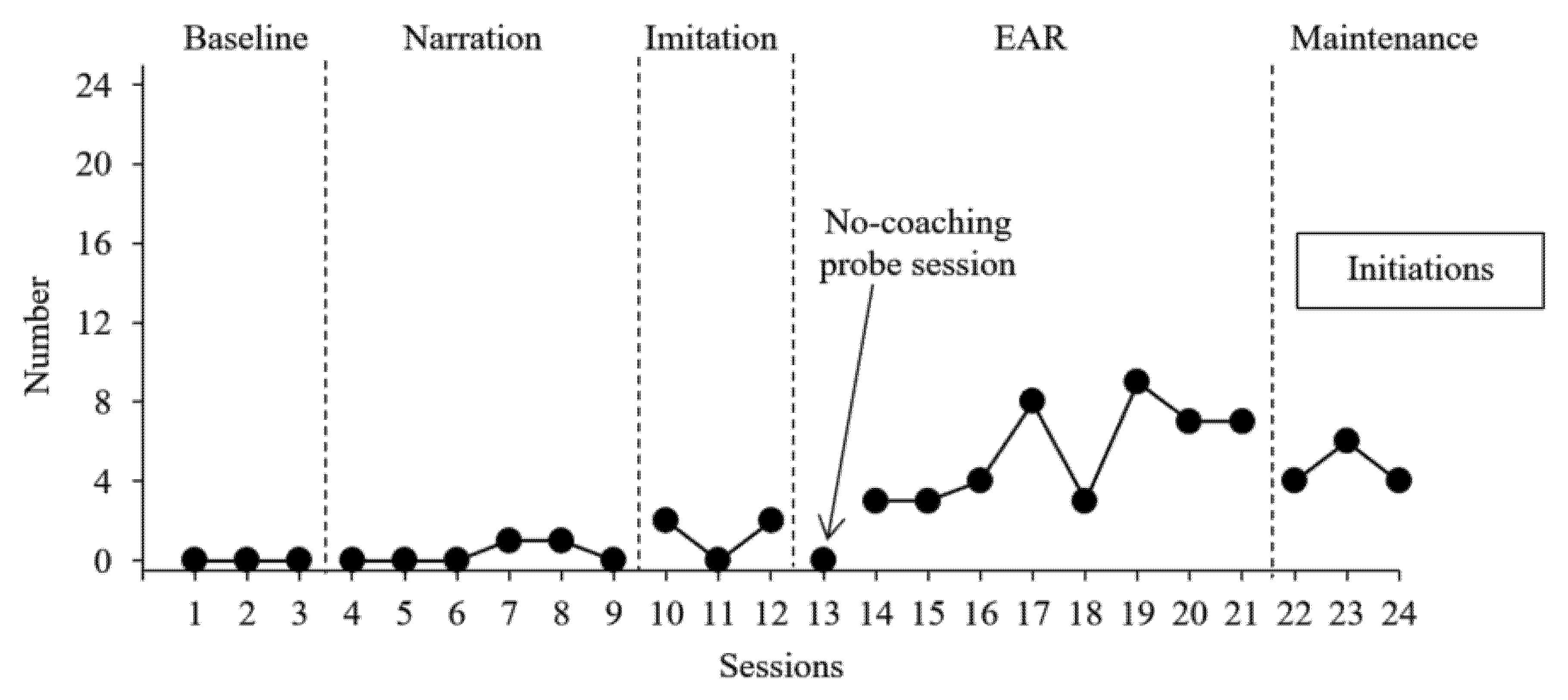

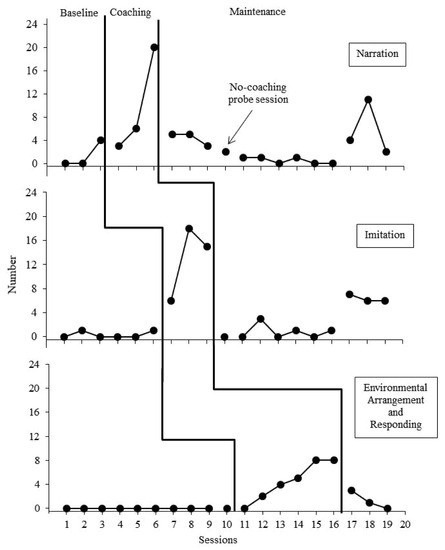

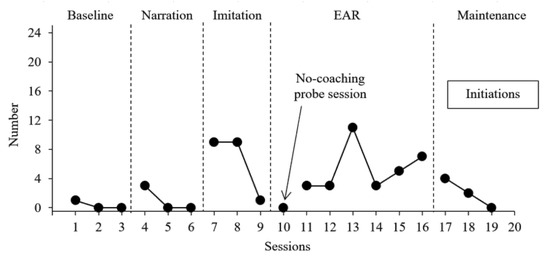

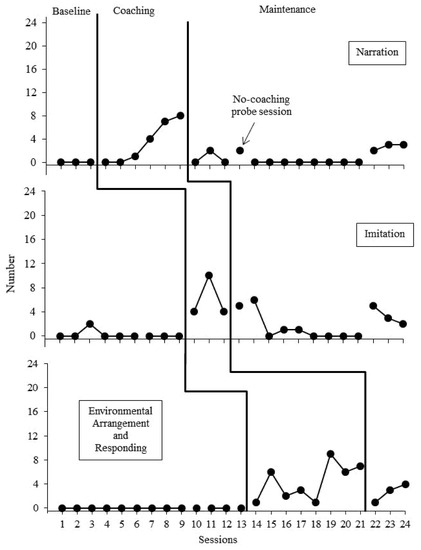

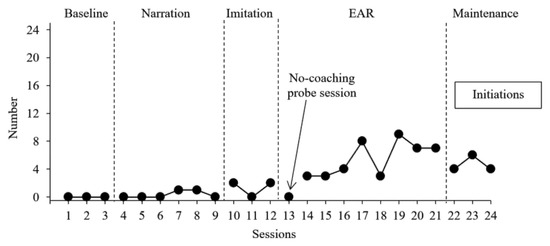

Ann and Lee’s data are displayed in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively; and Yan and Easton’s data are displayed in Figure 4 and Figure 5, respectively.

Figure 2.

Number of target behaviors performed by Ann throughout study conditions.

Figure 3.

Number of target behaviors performed by Lee throughout study conditions.

Figure 4.

Number of target behaviors performed by Yan throughout study conditions.

Figure 5.

Number of target behaviors performed by Easton throughout study conditions.

Ann. During Ann’s baseline sessions, stable data with near zero occurrences for all sessions were observed for imitation and EAR. For narration, there were zero occurrences across the initial two sessions and an increase to five occurrences in the third and final baseline session. The training was introduced after this increase based on in vivo data collection (i.e., instructional coach collecting data while directly observing parent interacting with child); it was not until Ann’s data from this session were measured more accurately through video recording that the increase in narration was observed. Following the introduction of training on each of the target behaviors, a therapeutic change in trend and or level was observed in the data. Ann reached the mastery criterion in 3–6 sessions for each behavior. Maintenance data for previously mastered behaviors approximated baseline levels for the session during which Ann was receiving training on a new behavior. During the final three maintenance sessions, narration and imitation data were at mastery criteria levels while EAR data indicated a decelerating trend towards baseline level.

Yan. Across all of Yan’s baseline sessions, there were two occurrences of target behaviors. Following the introduction of training, narration data indicated a therapeutic accelerating trend with the mastery criterion reached in six sessions. Imitation data reflect an absolute change in level from zero to four occurrences with mastery criterion achieved in three sessions. EAR data were initially variable across coaching sessions resulting eight sessions until Yan mastered the behavior. Similar to Ann, maintenance data for previously mastered behaviors mirrored baseline data levels while Yan was receiving coaching on a new behavior. Across the final three maintenance sessions Yan’s data were at or below mastery criteria levels and above baseline level responding (range 1–4 occurrences). These data reflect a functional relation between the brief coaching package and Yan’s engagement in the target instructional behaviors.

Child initiations. Table 2 provides results of multi-level models estimating the association between parent engagement in target naturalistic language strategies and children’s initiations using English vocabulary. Bivariate correlations between variables were weak and ranged from −0.28 to 0.15. Model 1 indicates that, on average, with each session, the frequency of initiations increased by an average of 0.25 (95% CI [0.10, 0.39]). This association was controlled for in all other models by including the Sessions variable. When Narrations, (Model 2) Imitations (Model 3), and EAR (Model 4) were entered as single variables alongside the Sessions variable, only parent engagement in EAR was meaningfully associated with children’s initiations (B = 0.60, CI [0.25, 0.95]). An interpretation of this association indicates that, on average, for every occurrence of EAR, a child engaged in 0.60 initiations (when controlling for Sessions). As an alternative interpretation, on average, for every two EARs that a parent engaged in, a child engaged in at least one initiation. When controlling for the linear trend in children’s initiations (i.e., Sessions) and the occurrences of each target naturalistic language strategy in Model 5, the meaningful association between parent engagement in EAR and child initiations remained (B = 0.71, CI [0.35, 1.07]). On average, each occurrence of EAR by a parent was associated with 0.71 initiations when controlling for the trend in children’s data and occurrences of other naturalistic language strategies. Regarding the performance of the models, we perceive Model 5 to be the best performing model due to it having the smallest log likelihood; although, we recognize that given the small sample size (i.e., 46 observations at Level 1, two cases at Level 2) overfitting of the data may influence the estimates.

Table 2.

Models examining child initiations as a function of parent engagement in target naturalistic language strategies.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of a brief coaching package, with previously demonstrated effectiveness for parents of young children with communication delays, on parent use of naturalistic language strategies with young DLLs. In this study both parents learned how to implement multi-tiered language interventions at home and at predetermined levels of mastery. Regarding maintenance of the strategies, modest gains above baseline levels were observed, but the gains did not sustain at levels observed during the provision of coaching. Visual analysis of the data indicates a functional relation between the brief coaching package and Yan’s engagement in the naturalistic language strategies. Due to accelerating baseline narration data immediately prior to the introduction of the coaching package, there is limited confidence in the presence of a functional relation with Ann. Although child behaviors were not evaluated within the context of an experimental design, our models estimated that parent engagement in EAR was meaningfully and positively associated with child engagement in English language initiations. This finding supports the use of actively manipulating of a child’s environment in conjunction with systematic prompting and reinforcement to achieve meaningful changes in vocal initiations. However, we cannot rule out the additive impact of more passive strategies, such as narration and imitation, as the children were exposed to these strategies immediately prior to the parents receiving training on EAR.

For both parents, the use of previously mastered strategies decreased during training sessions targeting a new behavior. For example, while Yan received training on EAR, her use of imitation and narration strategies returned to baseline levels. This was not observed in previous evaluations of the brief coaching package when targeting the same naturalistic language strategies [10]. One potential reason for this difference in maintenance data may be due in part to English being neither Ann nor Yan’s native language. That is, prompting from the instructional coach was given in English and may have required more intensive interpretation skills for Ann and Yan than for parents that participated in previous research. Despite the initial decreases in parent narration and imitation during maintenance sessions, all target behaviors were above baseline level responding during the final three maintenance sessions following mastery of all target behaviors.

Also different from prior research examining the brief coaching package, Ann and Yan required four home visits before mastering all target behaviors. In previous studies, three contacts were sufficient for parents reaching mastery criteria with all target behaviors. We think that conducting all trainings and study sessions in the home environment affected parents’ acquisition rates. For example, parents often needed to attend to another sibling or respond to a relative’s question throughout a home visit. In previous studies, sessions were conducted exclusively in a university-based outpatient clinic [10] or across both school and home settings [9]. Given that Part C services are commonly provided in home, additional research in home-based environments is warranted.

5. Limitations and Conclusions

The primary limitation of this study is the therapeutic accelerating trend observed in Ann’s baseline narration data. Ideally, additional baseline sessions would have been conducted until the data were stable. The instructional coach made the decision to introduce the brief coaching package based on data collected in vivo, rather than through video recordings. Given that the brief coaching package was developed to be provided across three 1 h contacts, decisions about when to introduce training may be needed midway through a home visit, and therefore, there may not be time to watch a video and code data. It should be noted that prior studies evaluating the brief coaching package involved multiple members of research teams during training sessions. For example, one member may operate a video camera to record the session and another member may collect data in vivo, all while the instructional coach focuses on providing prompting and reinforcement during the session. Within this study, the instructional coach was the only member of the research team present with families during the sessions. Therefore, the instructional coach setup the video camera, collected data on occurrences of target behaviors, and provided prompting and reinforcement all within the same session. It is likely that the multiple responsibilities of the instructional coach affected the reliability of the in vivo data that were collected on Ann’s narration during baseline, resulting in a decision to introduce training prior to obtaining stable data. Despite this limitation as it pertains to the study’s internal validity, we think it highlights considerations of ecological validity for future studies. That is, early intervention services are not generally provided by multiple providers simultaneously. Therefore, providers should be aware of challenges that they may encounter when attempting to replicate the brief coaching package in home environments with resources typical of early intervention services (e.g., one provider available to simultaneously collect data and provide prompting and reinforcement). Given these findings, this study extends the literature on training parents on naturalistic language strategies for young children using a brief coaching package. Supplementary materials are available for review.

Supplementary Materials

Study materials and syntax for conducted analyses are available at https://osf.io/gmdk4/.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z., J.G., and J.D.L.; methodology, L.Z. and J.D.L.; data collection, L.Z. and C.S.; validation, C.S.; analysis, L.Z. and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.S.; visualization, C.S.; supervision, J.G. and J.D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of University of Kentucky.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ballantyne, K.G.; Sanderman, A.R.; Levy, J. Educating English Language Learners: Building Teacher Capacity. Roundtable Report. National Clearinghouse for English Language Acquisition & Language Instruction Educational Programs. 2008. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED521360.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Grisham-Brown, J.L.; Hemmeter, M.L. Blended Practices for Teaching Young Children in Inclusive Settings, 2nd ed.; Brookes Publishing Co.: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center and Center for IDEA Early Childhood Data Systems. IDEA Child Outcomes Highlights for FFY2018. 2020. Available online: https://ectacenter.org/eco/pages/childoutcomeshighlights.asp (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Friedman, M.; Woods, J.; Salisbury, C. Caregiver coaching strategies for early intervention providers: Moving toward operational definitions. Infants Young Child. 2012, 2, 62–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, E.E.; Fettig, A. Parent-implemented interventions for young children with disabilities: A review of fidelity features. J. Early Interv. 2013, 35, 194–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fettig, A.; Barton, E.E. Parent implementation of function-based intervention to reduce children’s challenging behavior: A literature review. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2014, 34, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDEA Infant & Toddler Coordinators Association. ITCA Tipping Points Survey. Part C implementation: State Challenges and Responses. 2014. Available online: http://www.ideainfanttoddler.org/pdf/2014-ITCA-State-Challenges-Report.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Patterson, S.Y.; Smith, V.; Mirenda, P. A systematic review of training programs for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: Single subject contributions. Autism 2012, 16, 498–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatcher, A.; Grisham-Brown, J.; Sese, K. Teaching and coaching caregivers in a Guatemalan orphanage to promote language in young children. J. Int. Spec. Needs Educ. 2018, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, J.D.; Ledford, J.R.; Shepley, C.; Mataras, T.K.; Ayres, K.M.; Davis, A.B. A brief coaching intervention for teaching naturalistic strategies to parents. J. Early Interv. 2016, 38, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.H.; Snyder, P.; Reichow, B. Systematic review of English early literacy interventions for children who are dual language learners. Top. Early Child. Spec. Educ. 2020, 40, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, D.C. The development and early care and education of dual language learners: Examining the state of knowledge. Early Child. Res. Q. 2014, 29, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Conference of State Legislatures. Dual language learns: State options under the Every Student Succeeds Act. 2016. Available online: www.ncsl.org/Portals/1/Documents/educ/Proof_CP%26D_%20DualLanguage.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Division for Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children; National Association for the Education of Young Children; National Head Start Association. Frameworks for response to intervention in early childhood: Description and implications. Commun. Disord. Q. 2013, 35, 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- Division for Early Childhood of the Council for Exceptional Children. DEC Recommended Practices in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education 2014. Available online: http://www.decsped.org/recommendedpractices (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Lane, J.D.; Lieberman-Betz, R.; Gast, D.L. An analysis of naturalistic interventions for increasing spontaneous expressive language in children with autism spectrum disorder. J. Spec. Educ. 2016, 50, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, J.R.; Gast, D.L. (Eds.) Single Case Research Methodology; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 377. [Google Scholar]

- What Works Clearinghouse. Standards Handbook Version 4.0. 2017. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Docs/referenceresources/wwc_standards_handbook_v4.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2022).

- Declercq, L.; Cools, W.; Beretvas, S.N.; Moeyaert, M.; Ferron, J.M.; Van den Noortgate, W. MultiSCED: A tool for (meta-) analyzing single-case experimental data with multilevel modeling. Behav. Res. Methods 2020, 52, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferron, J.M.; Bell, B.A.; Hess, M.R.; Rendina-Gobioff, G.; Hibbard, S.T. Making treatment effect inferences from multiple-baseline data: The utility of multilevel modeling approaches. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, A.P.; Hancock, T.B.; Nietfeld, J.P. The effects of parent-implemented Enhanced Milieu Teaching on the social communication of children with autism. Early Educ. Dev. 2000, 11, 423–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).