Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic forced educational institutions to move online, and it is important to understand how students perceive learning in a digital learning environment. We aimed to investigate students’ perceived learning outcomes in a digital learning environment and associations between perceived learning outcomes and grades achieved. An anonymous electronic survey was used (n = 230, response rate 34%). A significant linear relationship between overall perceived learning outcome and grade achieved was found (B 0.644, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.77). Of the different learning activities, attending digital seminars were positively associated with grades (B 0.163, 95% CI 0.002 to 0.32). In particular, participating in voluntary colloquium group (B 0.144, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.26) and motivation to learn (B 0.265, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.41) predicted the students’ grades. Intrinsic motivation was positively associated with grades (B 0.285, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.45), and extrinsic motivation was negatively associated with grades (B-0.213, 95% CI-0.35 to -0.07). Nursing students’ perceived learning outcomes and grades were positively associated. Of the different learning activities, attending digital seminars predicted higher grades. Additionally, attending colloquium groups and being motivated to learn predicted higher grades, while high extrinsic motivation was associated with lower grades.

1. Introduction

Anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry (APB) together are one of the major bioscience concepts integrated into the nursing student curriculum. APB is essential for nursing students to understand diseases and the treatment of patients. However, the course is considered challenging, and the failure rate is high. The APB subject is also found in the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) professions; however, nursing is still not included among those [1]. The themes in APB provide nursing students with fundamental knowledge about the human body and how the body functions, and thus it is essential to understand diseases and treatments. Still, students often find biosciences challenging due to large volumes of content [2,3,4,5,6] and lack of clinical relevance [2]. Reasons for why students find this subject challenging include previous education in natural sciences [4], age, self-efficacy, and study skills [3,5]. Furthermore, courses in APB have long been recognized as challenging, and thus this may also be a result of student and faculty beliefs and inherent features of the discipline itself and not factors related to instruction or the students themselves [6].

Blended learning is rapidly becoming the new standard in nursing education and is used in an expanding number of approaches and also in bioscience [7]. Blended learning is defined as a combination of learning activities that involves both face-to-face interactions and technologically mediated interactions between students and teachers [8]. Still, blended learning may include any number of content delivery methods from web-based to mentor-based [9].

Active learning is a form of self-regulated learning that has been shown to increase student performance [10,11]. It is a model that encourages meaningful learning and knowledge construction through collaborative activities supporting the students’ thinking and doing [12]. Active learning strategies range from small peer discussions to fully flipped classrooms [11], such as in a blended-learning environment where students perform active learning activities after preparing with pre-recorded lectures before class [8,13]. It engages learners in the process of learning and, opposed to passive listening, emphasizes higher-order thinking [10]. Collaborative learning, an active learning concept where students work together in small groups to solve a problem [12], is one commonly used learning method in nursing education due to the positive influence on student learning [14]. Active learning has become increasingly popular in the past decades; however, a diverse set of assumptions about teaching and learning often impact perceptions and implementation of an active learning approach. Almost 50 years ago, Vygotsky insisted that learning is largely a social phenomenon, where learners construct their mental models through social collaboration, building new understanding while actively engaging in learning experiences with other people. This social constructivism stresses the importance of scaffolding, where instructors or peer assistants support the students in the zone of proximal development, where prompting, simplifying, and feedback support the learners in their learning process [12,15]. Today, a variety of blended-learning approaches are used in nursing education; however, the majority of which have been happening in the classroom [7]. Blended learning is regarded as an approach that combines the benefits of face-to-face and online learning components; however, challenges with the online component have been highlighted in a recent systematic review [16]. Students often use the online component at their own pace and navigate through the online learning materials on their own. This requires some self-regulating, which can be challenging for students due to procrastination, poor time management, or lack of self-regulation skills [17].

As the pandemic of COVID-19 has forced educational institutes, including instructors and learners, to move online, it is important to understand how students experience learning in this digital learning environment. On 12 March 2020, the universities in Norway closed due to COVID-19, and university lectures were switched to synchronous digital lectures and student-active group activities using a digital platform. Digital formats of learning may be both an effective, resource-saving, and participatory form of learning [18]. A scoping review found that students in general appreciate individualized and self-paced learning and that digital formats increased their motivation to learn [18]. Various strategies that may improve student engagement and interaction such as peer learning and flipped classrooms have been applied to anatomy education. A recent study found that nursing students receiving a blended-learning approach performed better on a national exam compared to those receiving face-to-face teaching [19].

A variety of mechanisms may lead to increased academic engagement and achievement; however, student motivation also plays an important role in academic success [20]. Motivational regulators, as conceptualized by self-determination theory (SDT), should be viewed from a multidimensional perspective, where SDT differentiates between intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation [21]. Intrinsic motivation reflects engagement in an activity due to inherent interest and for the pleasure and satisfaction of performing it. When students are intrinsically motivated, they act out of choice for the pleasure derived during class participation and from completing the learning tasks [21]. In contrast, extrinsic motivation involves engaging in an activity due to a separate consequence, such as obtaining a reward or avoiding punishment [21].

Previously, both learning style and instructor feedback have been associated with students’ perceived learning outcomes in online learning [22]. In addition, course structure and self-motivation have been found to affect student satisfaction [22]. Recently, student motivation was found to be a determinant of students’ perceived learning outcomes, where various factors such as interaction, motivation, course content, and the role of the instructor were key determinants of a positive learning outcome [23]. Intrinsic motivation, especially, has been found to be the strongest predictor of perceived learning outcomes in an online setting [24].

In this shift towards online education, it is essential to gain more knowledge about students’ perceived learning outcomes and their association with their actual learning outcome (achieved grade). Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore potential relationship between nursing student perceptions of learning in an online learning environment and the grade achieved in the final exam. Furthermore, possible factors (gender, age, scientific/vocational background, COVID-19 situation, colloquium group, and motivation) that may predict the overall perceived learning outcomes and grade achieved were explored. Therefore, the research questions are:

- (1)

- What are the students’ perceived learning outcomes for each specific learning activity?

- (2)

- Is there any association between the students’ perceived learning outcomes of the learning design and the grade achieved?

- (3)

- Which factors (i.e., gender, age, vocational background, scientific specialization, COVID-19 situation) predict the overall perceived learning outcomes of the blended learning design in APB?

- (4)

- Which factors (i.e., gender, age, vocational background, scientific specialization, COVID-19 situation) predict the grade obtained in APB?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional study was conducted using an anonymous electronic survey created in Nettskjema [25].

2.2. Setting

The APB course was taught over 15 weeks during the first semester (12 ECTS). Furthermore, it was divided into eight topics with a digital blended learning design, with a flipped classroom approach. As preparation before the synchronous topic digital lecture and seminars, students were asked to review the topic’s pre-class digital learning resources (films and a preparation task assignment). After each of the digital topic lectures, students completed mandatory digital active learning seminars using a digital problem-based learning approach and a post-class mandatory multiple-choice (MC) test. In the seminars, the students worked in small groups of 3–5 students, supervised by both teacher and student assistants while solving the seminar tasks. The teaching strategies used in the seminars are based on the principles of student active learning that have been shown to increase student learning outcomes [10,11]. The student assistants were near-peers, guiding students in lower year (1–2 years), a form of peer-assisted learning (PAL) [26,27].

2.3. Participants

Participants were first year nursing students from Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway. They were recruited in the second semester, and the only eligibility criterion was being a nursing student having the APB exam in December 2020.

2.4. Questionnaire

The questionnaire was distributed to all first-year nursing students in the bachelor’s degree program at Oslo Metropolitan University (N = 670), registered as active students in the 2020 APB course. The students were invited to participate through an email invitation consisting of a short informational text and a link to the questionnaire. The invitation was sent the day after the announcement of grades (19 January 2021). A friendly reminder email was sent after one week. The questionnaire was based on the questionnaire used in our previous study [28] but further developed by the authors (CT, MEM, MM).

The students were asked to fill in their achieved grade on the APB course (A–F), where A stands for excellent and F for fail.

High school specialization was assessed by asking the questions: “Do you have specialization in one or more of the subjects biology, chemistry, or physics from high school?” and “Do you have a vocational background from high school?”.

The students’ overall perceived learning outcomes in the subject were assessed asking the question: “How would you rate your overall learning outcome in the course?”, using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = very bad and 6 = very good).

Student experience with COVID-19 was assessed by asking the questions: “The COVID-19 situation has had a deteriorating contribution to my learning outcome in the subject” (1 = disagree and 6 = agree) and “The COVID-19 situation has contributed to getting worse grade in the subject than expected” (1 = disagree and 6 = agree).

The student’s perceived learning outcomes of each specific learning activity were assessed asking the question: “What was your learning outcome from the following learning activities?”. For each learning activity, students were asked to grade their level of perceived learning outcome on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = very bad and 6 = very good).

The learning activities included:

- Digital learning resources (films in “Canvas”, asynchronous)

- Preparation task before class (questions in “Canvas”, asynchronous)

- Digital lecture (synchronous in Zoom)

- Digital seminars (mandatory, synchronous in Zoom)

- MC test after class (mandatory, in Canvas, asynchronous)

The students were provided preparation tasks before class for each theme in the course in the university’s learning management system “Canvas”, which consisted of films and questions. Of the different learning activities, only the digital seminars and MC tests after class were mandatory. The students’ perceived learning outcomes of voluntary colloquium groups were assessed, also using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = very bad and 6 = very good).

In addition, participants answered questions concerning demographic data such as age and gender.

The students were asked to assess these statements concerning their motivation to learn APB (1 = totally disagree and 6 = totally agree): “Learning anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry is important to become a good nurse”, “Learning anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry is important to understand how the body works”, “The most important thing for me in learning anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry is to pass the exam”, and “I am very motivated to learn anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry”

2.5. Analysis

To investigate the perceived learning outcomes of various learning activities, descriptive analysis was used. Frequency and percentage distribution as well as mean score value with associated standard deviation for the different learning activities are presented.

To investigate associations between the overall learning outcome/perceived learning outcomes of the learning design and the grade achieved, a Pearson correlation test was conducted. To further investigate the different learning activities and grades achieved on the exam, ANOVA and linear regression models were used.

To investigate factors predicting the overall perceived learning outcomes in the learning design and grade achieved, linear regression was used with total perceived learning outcome/grade as the dependent variable, and gender, age, vocational background, scientific specialization, COVID-19, colloquium group, and motivation as independent variables. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Software (version 27).

3. Results

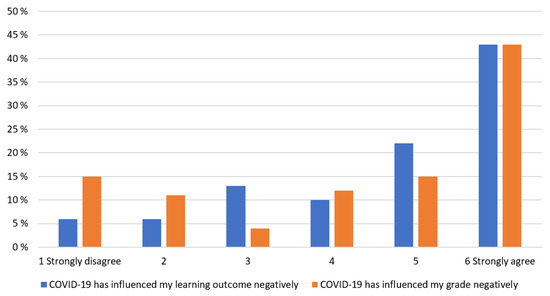

A total of 230 students completed the questionnaire (response rate 34%), 201 women and 29 men (age 19–56 y) (Table 1). One-third of the students had a background in science subjects and one-third had a background in vocational subjects from high school. More than half of the students agreed that COVID-19 had negatively influenced their learning outcomes as well as their achieved grade (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants (n = 230).

Figure 1.

Influence of COVID-19 on learning outcomes and grade.

3.1. Perceived Learning Outcomes of Various Learning Activities

The students were first asked to range their overall learning outcome of the APB course on a scale 1–6, and here the mean (SD) score given was 3.4 (SD 1.36). Of the various learning activities that were part of the course, the MC test after class (mandatory) received the highest mean score 4.1 (SD 1.54), and the digital learning resources received the lowest mean score (Table 2).

Table 2.

Perceived learning outcomes from low to high (1–6) of the various learning activities, n (%), mean (SD).

3.2. Perceived Learning Outcomes of the Learning Design and the Grade Achieved

To investigate if there was any association between learning outcomes and the grade achieved, a Pearson correlation was conducted. The overall learning outcome was positively associated with the grade achieved, r = 0.56, p < 0.0001.

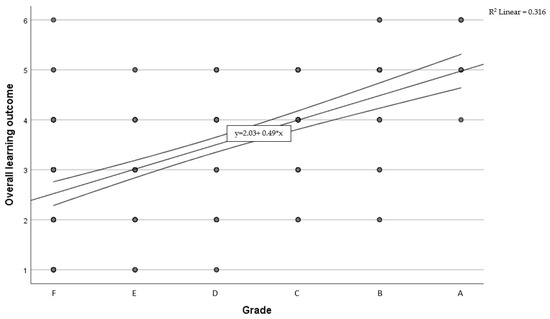

In linear regression models, associations between the perceived learning outcome of the learning design (independent) and the grade achieved (dependent) were investigated. A significant linear relationship between overall perceived learning outcome and grade achieved was found (B 0.644, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.77) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of grade achieved according to the average score of the overall learning outcome.

Possible associations between the mean score of the different learning activities and the grade achieved were investigated using ANOVA (Table 3). Of the various learning activities that were part of the course, the MC test after class (mandatory) and learning outcome descriptions received the highest mean scores (above five) among those with the highest grade (A), and student assistant supervising in seminars received the lowest mean score (Table 3). Furthermore, the MC test after class (mandatory) received the highest mean score among all grades, except for those with the highest grade, A. The students who achieved A grades also rated all teaching approaches more highly, except digital learning resources (films) and supervision by student assistants. Interestingly, the students that scored supervising from student assistants in seminars highest were those with grades C and D.

Table 3.

Mean (SD) scores of perceived learning outcomes of the various learning activities in the learning design and the grade achieved at the exam.

In the linear regression model, associations between the different learning activities and the grade achieved were investigated, and in the multivariate model, only attending active learning digital seminars was positively and significantly associated with grade (B 0.163, 95% CI 0.002 to 0.32). The multiple regression model explained 13% of the variation in the grades (Table 4).

Table 4.

Prediction of the different learning activities on the grade achieved.

3.3. Factors Predicting the Overall Perceived Learning Outcome

Linear regression models were fitted to examine the relationship between overall perceived learning outcome in the learning design as the dependent variable and gender, age, vocational background, scientific specialization, and COVID-19 situation as independent variables. Positive associations were found for colloquium groups (B 0.144, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.26) and motivation to learn (B 0.265, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.41), and negative associations were found for COVID-19. The multiple regression model explained 22% of the variation (Table 5).

Table 5.

Prediction of the overall perceived learning outcome of the blended learning design.

3.4. Factors Predicting the Grade Achieved

Linear regression models were fitted to examine the relationship between grade as the dependent variable and gender, age, vocational background, scientific specialization, and COVID-19 situation as independent variables. Positive associations were found for the colloquium group (B 0.149, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.40) and motivation to learn (B 0.319, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.53), and negative associations were found for COVID-19. The multiple regression model explained 39% of the variation (Table 6).

Table 6.

Prediction of the grade achieved.

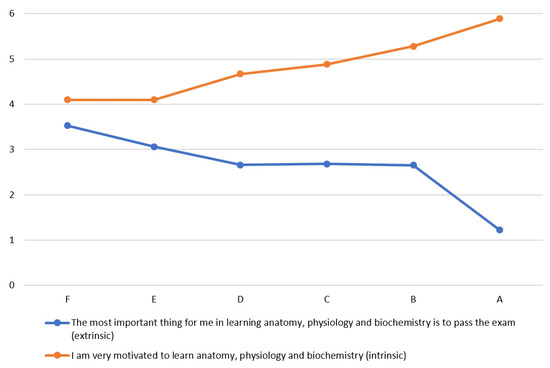

When further investigating the different motivation factors, intrinsic motivation was positively associated with grade (B 0.285, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.45), and extrinsic motivation was negatively associated with grade (B-0.213, 95% CI-0.35 to-0.07). The multiple regression model explained 16% of the variation in grades (Figure 3 and Table 7).

Figure 3.

Mean levels (1–6) of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation by grade level (1: Strongly disagree, 6: Strongly agree).

Table 7.

Estimated change in various motivation variables associated with grade.

4. Discussion

4.1. Perceived Learning Outcomes and Grade

This study examined the relationship between nursing students’ perceived learning through different learning activities in a blended digital learning environment and its associations with achieved grades. A significant linear relationship between overall perceived learning and grade achieved was revealed. This contrasts with what was found in a previous randomized controlled cross-over study that compared students perceived learning with their test results (MC) after active and passive lectures [29]. The study found that students in the active classroom learned more but perceived that they learned less, suggesting that students’ perception of their own learning can be anticorrelated with their actual learning [29].

In the present study, we found that especially high ratings of the perceived learning outcome in mandatory digital seminars were positively associated with grades. This is in line with previous studies [30,31]. In a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, seminar teaching was found to be an effective method for improving knowledge scores in medical education [31]. In seminar teaching, students achieved the purpose of learning by discussing assigned questions and issues under guidance [31]. In seminars, students are supposed to actively practice formulating, presenting, and discussing subject matter from the digital seminars, which demands active participation in the various learning activities.

Active learning is generally defined as an instructional method that engages students in their learning process and has been found to reduce achievement gaps in examination scores by 33% and narrow gaps in passing rates by 45% [32]. Increased examination performance in active learning was also found in a previous meta-analysis comparing active and passive learning (traditional lecture) [10]. The active learning approach places a greater responsibility on the learner, and it has been seen that students prefer low-effort learning strategies such as listening to lectures compared to active learning [29]. While students may discover the value of being actively engaged during a course, their learning may be impaired during the initial part if they are not made aware that they benefit from active instruction early in the semester [29]. Achievements can also increase if students get regular practice via prescribed (graded) active-learning exercises [33]. This was also seen in our study, where the mandatory MC test after class received the highest mean score for perceived learning outcomes across all grades, and the second highest (above five) among those with the highest grade (A).

In our study, the students solved the seminar tasks in small groups supervised by both teacher and student assistants. To have success in small group learning depends upon the roles and responsibilities taken by students and tutors, in addition to the group dynamic, which can be adversely affected by individuals [34]. The success of learning depends on the quality of student interaction within the group, which needs to be built in to promote active participation from each member and facilitate shared learning opportunities [35]. The preparation of peers may influence the quality of the seminars, and to improve deeper learning, the students must be well-prepared [30]. The lack of perceived learning outcomes due to dysfunctional groups and the lack of the preparation of peers was also reported in our study but is not presented here. A previous meta-analysis reported that even though the small group learning methods improved students’ academic achievements, it was most effective in higher levels of college classes, in groups of four or fewer, and where students can choose their own group. [36]. In our study, the students were placed into small, predefined groups, which thus may have influenced their perceived learning outcomes negatively.

Seminar teaching is a form of collaborative learning which has been used in nursing education for more than two decades due to its positive influences on student learning [14]. Collaborative learning is especially recommended in nursing education because it promotes student interactions and social skills [14]. Additionally, digital collaborative learning has been found to increase student knowledge and skills [37]. Students have been found to collaborate well in digital groups if the groups are small and the students know each other [38]. Student learning is best achieved if they participate actively in a friendly, relaxed atmosphere, with active participation of the students [39]. However, collaborative learning needs to be carefully designed if used as the main teaching approach [14]. Recently, four key themes were identified as important in a successful digital blended-learning approach: active learning, technical issues, support, and communication [40]. In a pandemic, it might have been challenging to address these key issues sufficiently.

In addition, APB is a challenging course due to the large quantity of material to learn and its interdisciplinary nature, where students need to be able to transfer knowledge from fields such as physics and chemistry with numerous principles [11]. In our study, however, we found no association between perceived learning outcomes and the students’ backgrounds within science subjects or vocational subjects from high school. However, for vocational subjects, we revealed an association with grades in the univariate model, but not in the multivariate. This may be explained by the fact that some of these students might have had some of the APB subjects previously and thus were more motivated to study nursing.

In our study, the students were supervised by both teacher and student assistants while solving the seminar tasks. The students were provided with a worksheet in the seminars, where a series of questions that were built on content previously described in lectures and preparation tasks were handed out. The questions varied between those that students should be comfortable answering and those introducing new material and, finally, material at a higher cognitive level. Even though students sometimes struggled with these higher-order questions, they received feedback from the teacher and student assistant. Interestingly, we found a U-shape for the student’s perceived learning outcome of supervising from student assistants in seminars, where the students with the middle grades C and D scored achieving the highest learning outcome from this learning activity. This was not found for the students’ perceived learning outcome of teacher counseling in seminars, where the perceived learning outcome increased with the grade. A recent review found that medical students experiencing PAL benefit in terms of academic performance relative to those not receiving PAL [41]. Timely feedback where instructors guide correct or incorrect answers is critical to avoid students making the predictions alone [42]. However, to time this communication can be challenging in an online setting [43].

4.2. Factors Predicting the Students’ Grades

In this study, higher grades were associated with being highly motivated to learn APB, which can be seen as intrinsic motivation. Furthermore, lower grades were associated with extrinsic motivation and learning APB to pass the exam. This is in line with previous research [44,45].

Intrinsically motivated students may try harder during the lesson, pay more attention, and persist more to learn compared with less intrinsically motivated students [44]. In particular, higher levels of autonomous motivation (internal regulated) have been associated with higher grades, while external regulated controlling motivation, which can be seen as extrinsic motivation, has been associated with lower grades [44]. The latter, an activity is performed to achieve some separate outcome or to avoid sanctions [21,46]. In our study, motivation to learn was not only associated with grade but also with the students’ perceived learning outcomes, which was also found in another study [23].

In the classic definitions of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, SDT argues that support for basic psychological needs enhances intrinsic motivation and internalization, resulting in higher achievement, whereas, controlling achievement outcomes through extrinsic rewards, sanctions, and evaluations may backfire and lead to lower-quality motivation and performance [46]. SDT assumes that people are drawn to psychological growth and integration and therefore towards learning, mastery, and connection with others [46]. However, these basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness must be satisfied across the life span and are fragile and can be negatively influenced by the attitude of the educator (e.g., if perceived as uncaring) [46]. Autonomy, especially, has been suggested to be associated with student motivation to engage in academic activities [47]. However, in addition to autonomy and competence, relatedness may also produce variability in intrinsic motivation [21]. Although this study did not explore the existing relationship between the students and the educators before teaching moved online, SDT indicates that the relationship between the teacher and learner is important to intrinsic motivation and hypothesizes that a similar dynamic may occur in interpersonal settings over the lifespan. Therefore, intrinsic motivation is more likely to flourish in contexts characterized by security and relatedness [21].

In our study, lower grades were negatively associated with COVID-19 situation, where the students reporting that their grade in the subject was worse than expected received the lowest grade. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the new normal was social distancing, and the students experienced social isolation and a general loss of motivation [38]. In our study, more than half of the students agreed that COVID-19 had influenced their learning outcome as well as their grade. In our curriculum, the blended learning was transferred from a combined face-to-face and online learning experience into a fully digital setting. This transition might be challenging for the students, and it has been reported that students have been affected by COVID-19 on several levels [38,48]. Students may fear themselves or others in their social network contracting the virus, changes in coursework delivery, unclear instructional parameters, loneliness, compromised motivation, sleep disturbances, as well as anxious and depressive symptoms [48]. Another study reports challenges with lack of academic and social contact with peers and that the students had felt alone in their studies [38]. It has also been reported that more than half of students miss traditional anatomy learning, i.e., with face-to-face lectures and interaction with mentors, and that, especially in APB, students feel a lack of confidence and find difficulty in the topics [49].

Recently, students’ and lecturers’ perspectives on the implementation of online learning due to COVID-19 were assessed in a German study [50]. Interestingly, both students and lecturers showed a predominantly positive perspective on the implementation of online learning, providing the chance to use online learning even beyond COVID-19 in the future curriculum [50].

4.3. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

A limitation of this study is the relatively low response rate, where only 34% participated. The questionnaire was based on the questionnaire used in our previous study [28]; however, it has not been validated. However, low attendance rates are common with online questionnaires [51]. This study included 230 participants, which is a similar number of respondents as in comparable studies [19,30].

This study investigated student perceived learning, which possibly was biased by their own preparedness. Still, self-reported learning outcomes and self-reports in scholarly research have been considered to be appropriate measures [52]. Another limitation is that students were asked to rate their perceived learning outcomes for the various learning activities after they received their grade, and it is therefore possible that students who achieved grade E or F graded their perceived learning outcomes as worse.

Another limitation may be that students who performed well or above their perceived level of expectation are more willing to respond to the questionnaire. However, the main strength of this study is that the distribution of grades found in our sample was the same as in the whole group of students in this APB course.

5. Conclusions

In this study we found a linear association between students’ perceived learning outcomes and grade achieved. The high ratings of the perceived learning outcomes in active learning seminars were positively associated with grades. Active learning is critically important for the students’ learning because it creates a learning environment that supports students in their learning process.

This study has implications for educators and students, especially in an online learning environment. Instructors should challenge the learners so that students’ intrinsic motivation is stimulated and basic needs such as autonomy, competence, and relatedness are satisfied.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.M., M.M. and C.T.; data curation, M.M. and C.T.; formal analysis, M.M. and C.T.; investigation, M.M. and C.T.; methodology, M.M. and C.T.; project administration, C.T.; resources, C.T.; supervision, M.M. and C.T.; validation, M.M. and C.T.; visualization, C.T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.T.; writing—review and editing, H.H., M.E.M., M.M., I.H.S. and C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This cross-sectional study was conducted using an anonymous electronic survey and did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to restrictions in the participants signed consent.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Green, C.; John, L. Should nursing be considered a STEM profession? Nurs. Forum. 2020, 55, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craft, J.A.; Hudson, P.B.; Plenderleith, M.B.; Gordon, C.J. Registered nurses’ reflections on bioscience courses during the undergraduate nursing programme: An exploratory study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 1669–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, K.T.; Knutstad, U.; Fawcett, T.N. The challenge of the biosciences in nurse education: A literature review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 1793–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, G. Why is biological science difficult for first-year nursing students? Nurse Educ. Today 2002, 22, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McVicar, A.; Andrew, S.; Kemble, R. The ’bioscience problem’ for nursing students: An integrative review of published evaluations of Year 1 bioscience, and proposed directions for curriculum development. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slominski, T.; Grindberg, S.; Momsen, J. Physiology is hard: A replication study of students’ perceived learning difficulties. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2019, 43, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leidl, D.M.; Ritchie, L.; Moslemi, N. Blended learning in undergraduate nursing education—A scoping review. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 86, 104318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bliuc, A.-M.; Goodyear, P.; Ellis, R.A. Research focus and methodological choices in studies into students’ experiences of blended learning in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2007, 10, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lothridge, K.; Fox, J.; Fynan, E. Blended learning: Efficient, timely and cost effective. Aust. J. Forensic Sci. 2013, 45, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.; Eddy, S.L.; McDonough, M.; Smith, M.K.; Okoroafor, N.; Jordt, H.; Wenderoth, M.P. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, B.E.; Barker, M.K.; Cooke, J.E. Best practices in active and student-centered learning in physiology classes. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2018, 42, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintzes, J.J.; Walter, E.M. Active Learning in College Science: The Case for Evidence-Based Practice, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; p. xiii. [Google Scholar]

- Hew, K.F.; Lo, C.K. Flipped classroom improves student learning in health professions education: A meta-analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Cui, Q. Collaborative Learning in Higher Nursing Education: A Systematic Review. J. Prof. Nurs. 2018, 34, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vygotskii, L.S.; Cole, M. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed, R.A.; Kamsin, A.; Abdullah, N.A. Challenges in the online component of blended learning: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2020, 144, 103701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bol, L.; Garner, J.K. Challenges in supporting self-regulation in distance education environments. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2011, 23, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sormunen, M.; Saaranen, T.; Heikkilä, A.; Sjögren, T.; Koskinen, C.; Mikkonen, K.; Kääriäinen, M.; Koivula, M.; Salminen, L. Digital Learning Interventions in Higher Education: A Scoping Review. Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2020, 38, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønlien, H.K.; . Christoffersen, T.E.; Ringstad, Ø.; Andreassen, M.; Lugo, R.G. A blended learning teaching strategy strengthens the nursing students’ performance and self-reported learning outcome achievement in an anatomy, physiology and biochemistry course—A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ. Pr. 2021, 52, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Cate, T.J.; Kusurkar, R.A.; Williams, G.C. How self-determination theory can assist our understanding of the teaching and learning processes in medical education. AMEE Guide No. 59. Med. Teach. 2011, 33, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, S.B.; Wen, H.J.; Ashill, N. The Determinants of Students’ Perceived Learning Outcomes and Satisfaction in University Online Education: An Empirical Investigation. Decis. Sci. J. Innov. Educ. 2006, 4, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baber, H. Determinants of students’ perceived learning outcome and satisfaction in online learning during the pandemic of COVID19. J. Educ. e-Learn. Res. 2020, 7, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sean, E. The Effects of Student Motivation and Self-regulated Learning Strategies on Student’s Perceived E-learning Outcomes and Satisfaction. J. High. Educ. Theory Pract. 2019, 19, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Nettskjema. Available online: https://nettskjema.no/?lang=en (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Evans, D.J.; Cuffe, T. Near-Peer teaching in anatomy: An approach for deeper learning. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2009, 2, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaussen, A.; Reddy, P.; Irvine, S.; Williams, B. Peer-Assisted learning: Time for nomenclature clarification. Med. Educ. Online 2016, 21, 30974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molin, M.; Meyer, M.E.; Medin, T. Anatomy, physiology and biochemistry: Nursing students’ perceptions of the learning outcome from a flipped classroom. Sykepl. Forsk. 2020, 15, e-82467. [Google Scholar]

- Deslauriers, L.; McCarty, L.S.; Miller, K.; Callaghan, K.; Kestin, G. Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 19251–19257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, R.A.M.; de Kleijn, R.A.M.; van Rijen, H.V.M. Peer-Instructed seminar attendance is associated with improved preparation, deeper learning and higher exam scores: A survey study. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, H.L.; Chen, D.X.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.Y. Effects of seminar teaching method versus lecture-based learning in medical education: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 1343–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, E.J.; Hill, M.J.; Tran, E.; Agrawal, S.; Arroyo, E.N.; Behling, S.; Chambwe, N.; Cintrón, D.L.; Cooper, J.D.; Dunster, G.; et al. Active learning narrows achievement gaps for underrepresented students in undergraduate science, technology, engineering, and math. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 6476–6483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.; O’Connor, E.; Parks, J.W.; Cunningham, M.; Hurley, D.; Haak, D.; Dirks, C.; Wenderoth, M.P. Prescribed active learning increases performance in introductory biology. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2007, 6, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmunds, S.; Brown, G. Effective small group learning: AMEE Guide No. 48. Med. Teach. 2010, 32, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scager, K.; Boonstra, J.; Peeters, T.; Vulperhorst, J.; Wiegant, F. Collaborative Learning in Higher Education: Evoking Positive Interdependence. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2016, 15, ar69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaian, S.A.; Kasim, R.M. Effectiveness of various innovative learning methods in health science classrooms: A meta-analysis. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2017, 22, 1151–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Männistö, M.; Mikkonen, K.; Kuivila, H.M.; Virtanen, M.; Kyngäs, H.; Kääriäinen, M. Digital collaborative learning in nursing education: A systematic review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2020, 34, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almendingen, K.; Morseth, M.S.; Gjølstad, E.; Brevik, A.; Tørris, C. Student’s experiences with online teaching following COVID-19 lockdown: A mixed methods explorative study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.P.; Radha, T.R.; Subitha, K. Comparison of effectiveness of lecture and seminar as teaching-learning methods in physiology with respect to cognitive gain and student satisfaction. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2017, 6, 4357–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowsey, T.; Foster, G.; Cooper-Ioelu, P.; Jacobs, S. Blended learning via distance in pre-registration nursing education: A scoping review. Nurse Educ. Pr. 2020, 44, 102775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, C.; Ellis, L.; Reid, E.R. Peer-Assisted learning in medical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. Educ. 2022, 56, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, J. Learning from Errors. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2017, 68, 465–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna, P. Blended Learning: An Institutional Approach for Enhancing Students’ Learning Experiences. J. Online Learn. Teach. 2013, 9, 271. [Google Scholar]

- Barkoukis, V.; Taylor, I.; Chanal, J.; Ntoumanis, N. The relation between student motivation and student grades in physical education: A 3-year investigation. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2014, 24, e406–e414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, S. Potential reciprocal relationship between motivation and achievement: A longitudinal study. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2018, 39, 38–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, C.; Binnie, V.I.; Wilson, S.L. Determinants and outcomes of motivation in health professions education: A systematic review based on self-determination theory. J. Educ. Eval. Health Prof. 2016, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasso, A.F.; Hisli Sahin, N.; San Roman, G.J. COVID-19 disruption on college students: Academic and socioemotional implications. Psychol. Trauma 2021, 13, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, A.; Bansal, A.; Chaudhary, P.; Singh, H.; Patra, A. Anatomy education of medical and dental students during COVID-19 pandemic: A reality check. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2021, 43, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenz, M.A.; Schmidt, A.; Wöstmann, B.; Krämer, N.; Schulz-Weidner, N. Students’ and lecturers’ perspective on the implementation of online learning in dental education due to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.; Henderson, J.; Alderdice, F.; Quigley, M.A. Methods to increase response rates to a population-based maternity survey: A comparison of two pilot studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, G.R. Using college students’ self-reported learning outcomes in scholarly research. New Dir. Inst. Res. 2011, 2011, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).