2. Background

Creativity has received considerable attention and is extensively characterized in the literature. Often defined as having a unique or novel idea that has value, e.g., [

10], creativity is described as part of a system [

11] or with reference to models outlining its different “types” [

12] and “facets” [

13]. Though some elements of creativity are almost universally acknowledged, it remains inconsistently defined, with its definition often described as being “contentious” [

14]. The issue of ambiguity is discussed in the literature, in particular, the imprecision relating to what is meant by creativity in educational contexts [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Bleakley [

18], for instance, explains that “the term is often employed uncritically, in the singular, and is reified” (p. 463).

Whilst creativity, when considered in its entirety, constitutes a range of different elements and dimensions, in the context of education, creativity is often conceptualized in terms of a set of creative attributes, habits, or thinking skills, e.g., [

3,

8,

19,

20,

21]. For instance, in Australia, the national curriculum for schools identifies four main skill areas: inquiring, generating ideas, reflection, and analysis and synthesis [

3]. Henriksen [

19] similarly identifies the transdisciplinary skills of: observing, patterning, abstracting, embodied thinking, modelling, play, and synthesizing. In the higher education context, Jackson and Shaw [

8] identify: being imaginative, being original, exploring, processing, analysing and synthesising data and ideas, and communicating, as skills that academics view as important. Again, in higher education, Jahnke et al. [

20] identify the “facets” of self-reflective learning, independent learning, curiosity and motivation, producing something, showing multiple perspectives, and reaching for original, entirely new ideas.

There are slightly different variations on these descriptions across the literature, and it is also recognized that different disciplinary contexts influence the presence, significance, and meaning of such descriptions. Jahnke et al. [

20], for instance, assert that disciplinary background is essential for understanding creativity in higher education. In their research surveying academics on their views on creativity, they found that social science-aligned academics tend to emphasize creativity as manifest when students are involved in self-reflective learning and independent learning, whilst academics within science and engineering fields tend to conceptualize creativity as visible in the processes of producing something, showing multi-perspectives, and reaching for original, entirely new ideas. These authors, however, also explain that there remains significant ambiguity, particularly in terms of how creativity is understood by actors in different disciplinary contexts, calling for further research to be conducted in this area [

20]. This sentiment is echoed by Jackson and Shaw [

8], who agree that “to extend our understanding of creativity in higher education we have to elaborate the meanings of creativity and the way it is operationalized in each disciplinary field” (p. 89).

Scholars have recognized that perceptions of creativity as expressed by others, through either quantitative or qualitative research methods, remain difficult to interpret. Quantitative measures, particularly Likert-type responses, common in creativity research, are known to be insufficient in circumstances where interpretation is known to vary amongst participants [

22,

23]. However, when considering the perceptions of different groups, even qualitative methods are not immune from such validity issues. As Edwards et al. [

24] put it, when describing the interpretation of creativity from different disciplinary groups, “… the issue of meanings emerges once more. Did academics in mathematics departments ‘mean’ quite the same thing as those in arts departments when speaking about ‘creativity’ and ‘the new’, for example?” (p. 71).

The most influential theoretical model that is used to account for differences, including differences in interpretations, remains Csikszentmihalyi’s systems model [

11]. The systems model of creativity proposes that creativity is a “process that can be observed only at the intersection where individuals, domains, and fields interact” (p. 314), offering recognition to elements overlooked by purely psychological approaches to creativity, which tend to focus on the individual. With this model, the ‘domain’ refers to the discipline’s “existing objects, rules, representations, or notations” (p. 315). Csikszentmihalyi explains that creativity occurs when a relatively permanent change is made to the domain by an ‘individual’. Not all changes are accepted, however, and thus, the ‘field’ refers to the actors or groups who act as gatekeepers to determine which changes are sustained over time (p. 315). Though the systems model of creativity represented a considerable development in creativity theory in that it acknowledged factors beyond the individual mind, the domain and the field elements of the system remain undertheorized, and their connection to the individual thus remains fragile. Glăveanu [

25], for instance, explains that “we are missing … a theory that relates … individual-level outcomes to the social and cultural contexts that help them come into being (p. 335)”.

It is within this context that we undertake the current qualitative study. To make sense of the data, we draw on sociological theory, here, Legitimation Code Theory (LCT), to conceptualize the nature of creativity as viewed through different disciplinary perspectives. That is, we use LCT to provide a way to characterize knowledge, or Csikszentmihalyi’s ‘domain’. In this research, the domains of interest include the academic disciplines of physics, history, and poetry. In this research, we consider the academic fields of physics, history, and poetry because they represent the considerable variation in knowledge and inquiry practices identified in scientific and social sciences fields [

26]. Such a comparative approach has proven useful in studies of literacy and sociology, where studying an object in relation to others provides insight beyond study of the one object in isolation, e.g., [

21,

27]. In studying creativity through the lens of these three disciplines, we also hope to understand the nature of creativity within and across disciplines in a more detailed way.

3. Theoretical Framework

In characterizing knowledge and inquiry practices, we begin with the Bernsteinian delineation of everyday knowledge and academic knowledge and the further classification of the latter as consisting of “horizontal” and “hierarchical” knowledge structures [

28]. Bernstein’s horizontal knowledge structures represent domains where knowledge consists of a “series of specialized languages, each with its own specialized modes of interrogation and specialized criteria for the construction and circulation of texts” (p. 162). Horizontal knowledge structures develop through the addition of new set of languages because “the set of languages which constitute any one horizontal knowledge structure are not translatable, since they make different and often opposing assumptions” (p. 163). Horizontal knowledge structures are common in the humanities and social sciences, for example, English literature, philosophy, and sociology, where different, often contradictory “perspectives” on a subject can co-exist. Hierarchical knowledge structures are “explicit, coherent, systematically principled” (p. 161), where knowledge develops through integration “at lower levels” and “across an expanding range of apparently different phenomena” (p. 162). Such hierarchical structures can be found in disciplines such as biology or physics, where “uniformities” are integrated and subsumed into more “general” frameworks, such as theories and laws.

Within the creativity literature, the nature of the discipline (or ‘domain’) has been discussed to some degree as a factor that plays a role in giving creativity its distinctive character, in a way consistent with Bernstein’s classifications [

29,

30]. For instance, Li [

30] describes domains with horizontality as able to “allow novelty to occur in all dimensions, resulting in divergent developments of the domain …”, whilst domains with verticality “possess certain stable elements that are existentially fundamental to the domain, thus permitting alteration only around certain dimensions” (p. 107). Keinänen et al. [

29] draw on Li’s conceptualization within their concepts of “axis” and “focus”. Axis reflects the degree of constraint (vertical for a higher degree of constraint and horizontal for fewer constraints). Focus refers to the degree of discreteness (modular versus broad tasks). The example given by these authors is of different forms of dancing: ballet exhibits a vertical axis and a modular focus due to its adherence to specific positions and movements and prescribed choreographed pieces and where dancers develop expertise in a single form of movement. In contrast, modern dance is horizontal in its orientation and with a broad focus because the ethic of modern dance is to challenge tradition. Modern dancers are more likely to exhibit expertise in a wider range of movements compared to traditional ballet dancers. Of course, there are subdomains of ballet and modern dance that challenge these characterizations, just as there are different subdomains of law, physics, and business that vary, in some cases, quite substantially. Thus, although these descriptions, including the Bernsteinian description, are consistent with each other and the illustrations provided, they do not offer a way to systematically analyse practices.

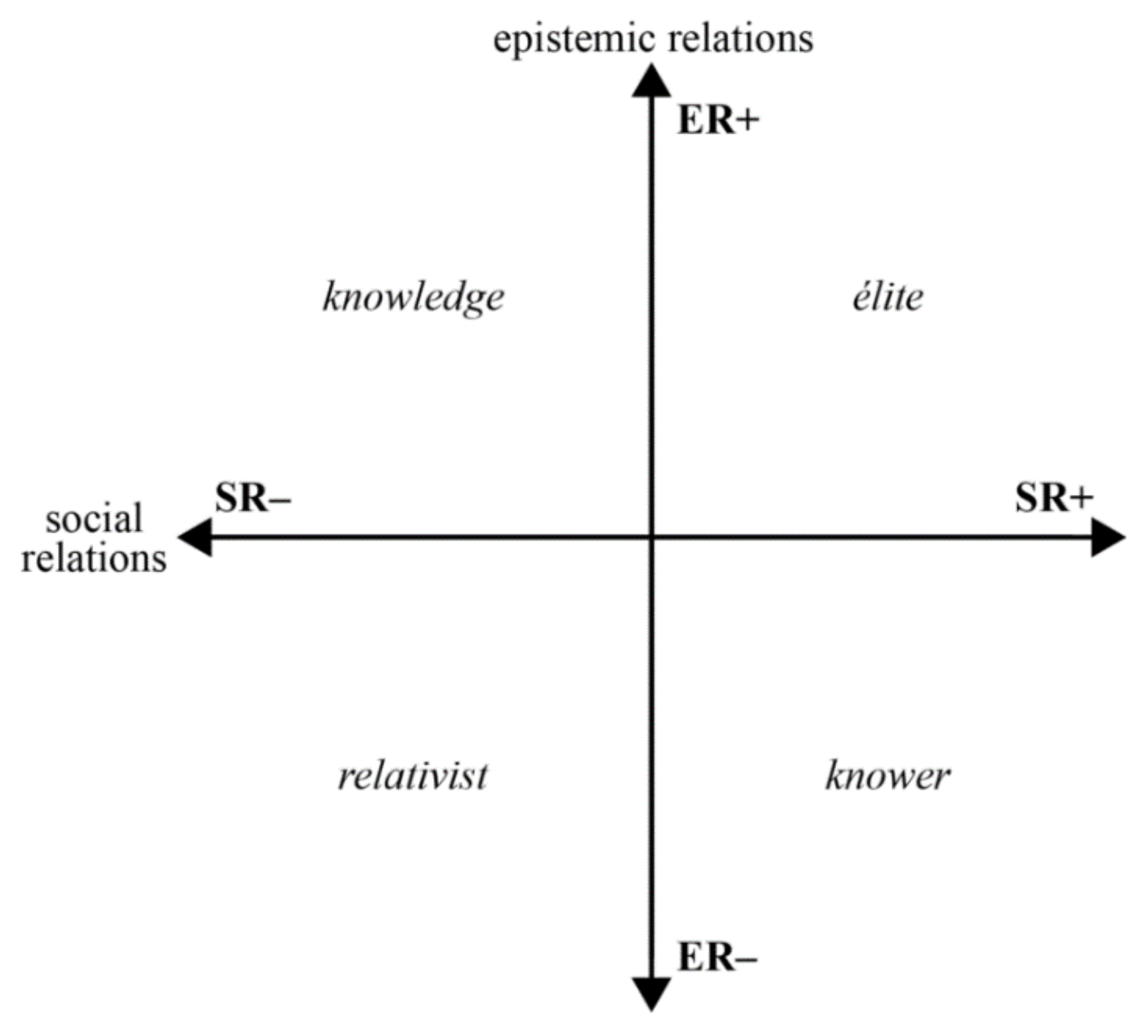

We thus draw on Legitimation Code Theory (LCT), a conceptual framework that builds on Bernstein’s knowledge structures, in order to take a more analytical and systematic approach to the empirical data. LCT operationalizes different types of knowledge through a construct known as Specialization, which is founded on the premise that “practices are about or oriented towards something and by someone” [

31] (p. 12). Specialization thus conceptualizes the relationships between practices and their object (known as epistemic relations) and practices and their subject (known as social relations). For example, physics is a “hierarchical” discipline known to be represented by stronger epistemic relations and weaker social relations: “possession of specialized knowledge, principles, or procedures concerning specific objects of study is emphasized as the basis of achievement, and the attributes of actors downplayed” [

31] (p. 12). As a contrastive example, weaker epistemic relations and stronger social relations characterise more “horizontal” disciplines where “specialized knowledge and objects are downplayed, and the attributes of actors are emphasized as measures of achievement, whether viewed as born (e.g., ‘natural talent’), cultivated (e.g., ‘taste’), or social (e.g., ‘feminist standpoint theory’)” [

31] (p. 12). The key to the operationalization of Specialization is that social relations and epistemic relations can vary in degree along a continuum, giving us an analytical tool known as the specialization plane and the associated four specialization codes that constitute the quadrants in

Figure 1 [

31].

5. Results

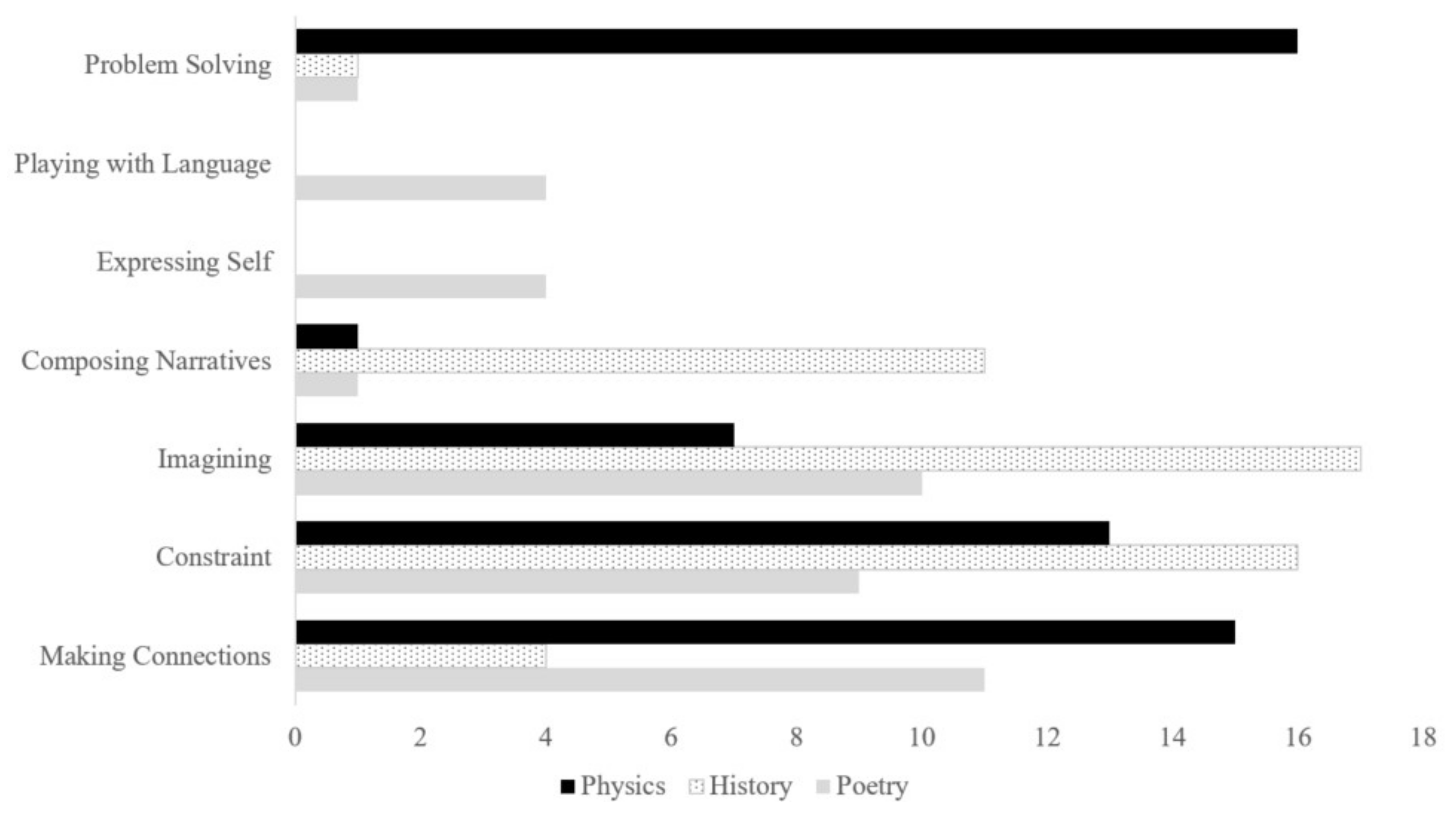

Seven thematic codes resulted, which reflect participants’ perceptions of the nature of creativity in physics, history, and poetry (

Table 1). It is important to note that each of the themes was not present in all discipline groupings.

Figure 2 shows the number of coding references for each theme across the three discipline areas.

The themes of Making Connections, Constraint, and Imagining exhibited a strong presence within the three discipline groups of participants, whilst Composing Narratives was mainly exclusive to history, Expressing Self and Playing with Language were exclusive to poetry, and Problem Solving was mainly confined to physics, with only one reference in both poetry and history.

5.1. Making Connections

Making Connections was a theme where creativity was described as making new connections between ideas, constructs, or fields. What was key to this theme was the novelty of the connections made, with links made being unexpected or surprising and involving discrete and likely disparate entities. Across the three disciplines however, although the concept of Making Connections was common, the practices involved differed. For example, in history, participants discussed the creativity in making “lateral connections”, making reference to the archives specifically. In physics, the connections were being made between existing knowledge or observations and “the latest theoretical thinking” or “pieces from here and pieces from … different subjects”. Interestingly, one of the physics experts and another history expert framed this as a series of questions, exemplifying how the differences in the substance of “creative connections” might manifest in the creative process:

“What’s the latest theoretical thinking? Why doesn’t this theoretical thinking match those observations? What if we do this, do that? … This doesn’t look right. How would I fix that?” (Physics)

“Well, where did this come from? Is it all on the paper here or is there …? You know, sometimes it’s just looking close and being like, ‘Hang on a minute. That date doesn’t accord to what I expected.’” (History)

In poetry, the connections made were discussed in fairly distinct ways by each of the three participants. One poet with a strong linguistics background made explicit connections between language and meaning: “All those strata … co-exist; the sounds that are alike and the meanings that are alike and the words that are alike and the grammatical structures that are alike—they’re all co-existing”. Poetry in this participant’s account involved a moment of creative inspiration, where the graphological, phonological, and semantic experience of language coalesce simultaneously in multiple ways. Another poet, however, emphasized instead how creativity in poetry fostered connections between experiences and people:

“You’re capturing the experiences of a person or the beliefs or perceptions of a person and interacting with those in some way, whether they’re, you know, on the stage for theatre or in a collection of poems.” (Poetry)

5.2. Constraint

The theme of Constraint represents a scale that is bookended by complete freedom and strong boundaries. Where this theme is identified in participants’ responses, it represents perspectives of creativity that sit somewhere on this scale. On the one hand, creativity was conceptualized as being spontaneous, unbounded, or not limited by conventions or rules. On the other, it was also perceived as only evident in relation to existing structures, knowledge, and norms and only made possible because of them. Of the 38 total references coded to Constraint (see

Figure 2), 35 referred to some element of constraint, whilst only 3 referred to ultimate freedom. All three of the freedom references originated in the one poetry interview, where the participant described poetry as “the freest way to engage in creative self-expression” through “freeform rather than through something really rigid like prose” because “there’s no rules for writing poetry in the way that it has to look for structure or form. It doesn’t have to rhyme … whatever (self-expression) sounds or looks like is great”. The importance of openness and possibility as central to creativity are pervasive ideas in the poetry interviews, with poetry as a form offering expressive possibilities: “I think poetry and its intensification is this alertness to the possibilities of every stratum”. Alongside the descriptions of potential freedom, two of the poets discuss creativity in poetry as adhering to some degree of constraint: it was reducing ideas to “pure meaning, through words”, which, in fact, was more difficult than in prose, where “you’ve got the capacity to expand and expand”. Rather, in poetry, the constraint is doing it in a concentrated way: “you’ve probably got about eight lines”.

In history, Constraint was mentioned with respect to being accountable to empirical verification. Views ranged from being constrained by the actual firsthand evidence to being constrained by accountability.

In physics, there was a strong view that “nature is the arbiter,” and that you “still have to agree with the data”. In a sense, this is similar to the discussion about empirical evidence in history although there was a key difference. In physics, to be creative, participants indicated that individuals are not only constrained by the data but also by all the theories and models that were generated from them: “you need to know that [why other theories have fallen by the wayside]… as part of that input into your creative process … It’s constrained thinking”. The notion of Constraint and the strong link between creativity and constraint is highlighted in the quotation below:

“So, it’s a really structured, constrained creativity, and I think that’s why it’s hidden sometimes … some people can’t see that from the outside, but actually, it’s a kind of creativity that then it’s quite hard to find because you have to absorb everything that’s already known and then try and figure out new things in that context.” (Physics)

5.3. Imagining

Represented within this theme is an understanding of creativity as involving a moment of imagination, speculation, or hypothesizing. It encompasses “thinking outside of the box” or envisioning possibilities that may be unusual or unexpected and at times involving the adoption of alternate viewpoints. Often, participants will characterize creativity as necessitating “seeing things from a different perspective” or will discuss taking a “new” approach.

An ability to speculate or imagine is described as being central to history due to the incomplete nature of historical data: “the problem, the further back you go is, you get fragments; fragment here, fragment there. And then, you get whole periods of time that are badly covered, so it’s very difficult. And in a sense, that’s where creativity comes in”. This form of thinking is described as having the potential to be a transgressive act, as the individual may need to challenge orthodoxy, confront previously held conceptions, or challenge the interpretation of others. To arrive at a new interpretation of history, the individual has to imagine an alternative to established narratives or histories. Unlike Constructing Connections, the key to this theme is a moment of speculation where the individual imagines data that are inaccessible, unknown, or silenced. It is not so much a matter of connecting potentially disparate sources but rather thinking of what evidence might as yet be undiscovered or whose voices might be missing from historical accounts: “So, I’d say, looking at … and saying, ‘where are the gaps in these stories? Whose voices are we not hearing? What stories are not being told?’” Similarly, in physics, this process of seeing differently might mean using established disciplinary thinking or processes in different or unexpected ways:

“The ability to look at something and think about it and for it to click in a way that it’s never clicked with anybody else … the best things is when you see it, you say, ‘Why didn’t I think of that’ and you … just sort of go, ‘That’s now so obvious. Why didn’t we think of that earlier?’ kind of thing.” (Physics)

There is perceptible tension within this theme, as the individual needs to negotiate the boundaries of their speculations. The respondents noted that not all creative interpretations were acceptable to the field, as they had to satisfy disciplinary demands of credibility, as encapsulated in the extract below:

“And so, you know, it is a creative, imaginative, speculative, responsible process, and the only way that we know of how to give that credibility, or warrantability is a better word, is that it’s a collective process; we have to put our ideas in a public forum where you have to have our colleagues and the public comment on them … If you just imagine your history without putting it out for collective discussion, it’s not a history.” (History)

This theme manifests differently in poetry, where the individual is encouraged to embrace another’s perspective to imagine the way that the other might use language or make meanings as they write. This can involve seeing as another might, rather than seeing “differently,” with the poet adopting multiple and alternative perspectives on the world to be able to look with “new eyes.” In poetry, this process of seeing from another perspective is more somatic and enables the poet to conceive of other ways of making meaning poetically: “if you can start thinking about different ways of constructing them [words] and putting them in particular forms and so on—different languages and cultures have different ways of locating those words and sentences. So, you know, let’s look at how we might locate the world differently in those words and sentences and structures.”

The themes that will be discussed next were not commonly expressed across the dataset, tending to emerge within distinct disciplinary contexts.

5.4. Composing Narratives

Composing Narratives emerged as a distinct theme in interviews with the history experts. Mentioned by all four participants, this theme was identified as a key creative endeavour in the discipline; typical of their comments is this one: “For me, the creativity is the writing aspect of how to bring the past to life and to write in a compelling sort of way”. In retelling historical content, the participants describe a conscious attention to the delivery of historical content. Creativity is described as central to communicating history in a novelistic manner in order to capture the reader’s attention. For some respondents, the re-telling of history also involved presenting the content persuasively to effect real-world change: “So, part of the creativity in history is, well, okay, so you’ve got the history, but it’s how you present it and how you present it in a way that impacts people and can affect social change”. Producing a narrative appears to provide a creative impetus for the discipline, with the writing process involving the careful selection of information to be included—“You have to decide what you’re going to leave out and what you’re going to put in,”—as well as focusing on the lyricism of the account: “Good history will sing to you”. An appreciation of “creative” writing in terms of the aesthetics of the form emerges from the interviews: “I think if you read good history, it is, at its core, creative because a good history will sing to you; it is beautifully written; it’s telling a narrative that you want to know what happens next. That in itself, to me, is a creative endeavour”.

5.5. Expressing Self

Personal expression was captured as a minor theme isolated to one poetry participant’s responses. From their perspective, creativity is an opportunity to share aspects of oneself: “to be creative in poetry means to self-express. Yeah, just to self-express, and in multiple forms”. Pervasive in this description is the absence of boundaries, with individuals able to express themselves in whichever forms they chose: “it’s really special, and I guess poetry over other forms specifically because it feels like the freest way to engage in creative self-expression”. Creativity is also described as a process of discovery, finding different dimensions to personal experiences as you use your writing to make connections to others:

“So, poetry has been self-expression, it’s been mostly almost like a diarised version of events in my life, or self-exploration around different understandings of things, in experiences of people, places, and records of those things and an attempt to bring connection to other people into that experience and to find some kind of unity across those experiences.” (Poetry)

5.6. Playing with Language

Emerging from all of the poetry interviews was an account of creativity as “experimental play with words”. Creativity is described as an active process, exploring how language can be reshaped, restructured, and reformed. This involves experimenting with sound, meaning, and visual appearance of language without an explicit end in sight. Instead, creativity is about discovering and making something new as captured in the following example:

“I think with any kind of creative writing, particularly poetry, you really are much more open to experimentation and play, and I think that that’s a very important way of seeing the world differently. I mean, you’re not making sense of it; in some ways, you’re taking it apart and reconstructing it or making new meaning for things, and that in itself I think is quite challenging and also very exciting and inspiring a sort of process.” (Poetry)

5.7. Problem Solving

Finding solutions to complex and often open-ended questions emerged as an aspect of creativity across the interviews. However, it was only in physics that problem solving appeared as a major theme with all three participants identifying it as a key aspect of creativity in the discipline. Significantly, these “problems” were often weakly defined or open-ended, without a clear or readily accessible solution: “Real creativity comes when there isn’t an answer”. As a result, many of the tasks set for tertiary students were not considered to be creative as solutions were already known. In physics, Problem Solving is described as involving a series of processes, moving from considering problems anew to identifying appropriate methodologies, to then testing and retesting possible solutions, and eventually arriving at an appropriate solution. The physicists describe creativity as tending to emerge when individuals use new or untried methodologies to access solutions; for example, “She did something that a whole team of about 1000 people in total had never done”. Solutions valued as “creative” by the participants were described as being “new” or “innovative” or as offering greater efficiency or utility: “Creativity [is] finding better and more efficient solutions” as is demonstrated in the following excerpt: “Creativity is to develop something new, innovative, or make a discovery, you know, that really make a discovery, and it’s something that typically, it’s recognized to be useful, or we bring it to something, you know, to an end-point”.

Although infrequently mentioned in poetry, one of the poet respondents offered a similar understanding of creativity as problem solving, pointing to creativity in poetry as finding solution for social problems: “For me, poetry enables us to conserve language and landscape through poetry in [Project name redacted], and so therefore, poetry is creative in the way that it comes up first with solutions”.

5.8. LCT (Specialisation)

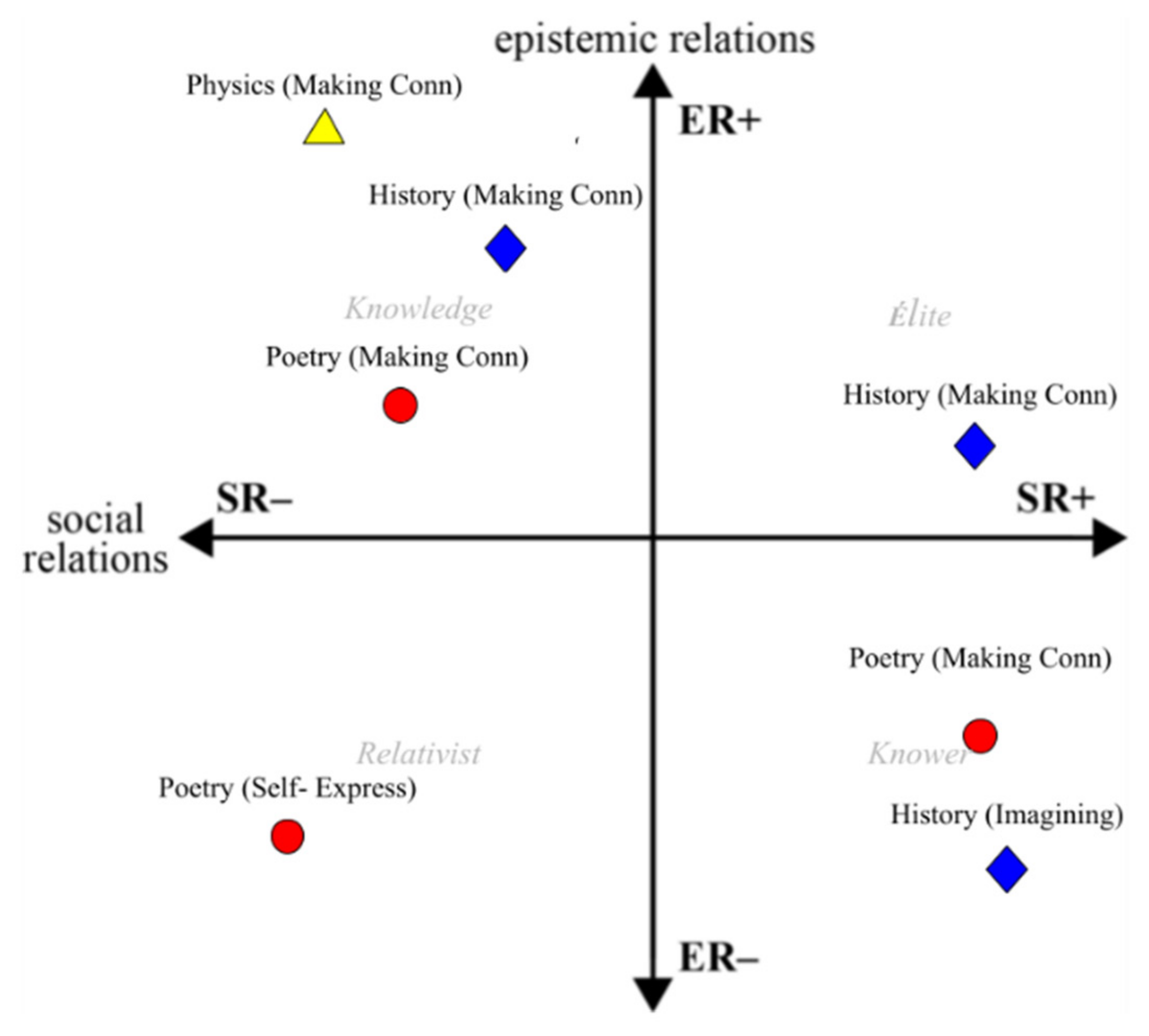

The dimension of Specialization from LCT was employed to suggest that interpretations of creativity in the respective academic disciplines differ along the two axes reflecting strengths of epistemic and social relations. That is, across the various themes, degrees of epistemic relations and social relations varied, ranging from weaker to stronger, and represented different positions on the Cartesian plane as well as different codes (

Figure 1). A knowledge code assignment, which is characterized by stronger epistemic relations (ER+) and weaker social relations (SR−), reflects coding references that emphasize the importance of empirical knowledge, such as in physics, where creative acts must agree with the data. A knower code, which is characterized by weaker epistemic relations (ER−) and stronger social relations (SR+) and, reflects coding references that emphasize the importance of the “knower,” such as with history, when it is said that certain perspectives (e.g., Indigenous, female) are valued as part of the creative process.

A selection of assignments that are based on coding references across the themes and for the different disciplinary groups of participants is presented in

Figure 3. Making Connections in physics can be described as a knowledge code (ER+, SR−) since it relates to connections of knowledge, observations, and theories that can be understood and recognized as novel by those in the field and where “who you are” is not considered to be as important (

Figure 3). In history, Making Connections similarly exemplified a knowledge code, with stronger epistemic relations associated with connections needing to align with records, material remains, or sources. However, participants explained that there was always some element of interpretation in Making Connections, thus its placement at a position of weaker epistemic relations and stronger social relations compared to physics. Creativity in history was also characterized as a knower code. In Imagining, for example, creativity in history is described as engaging perspective of voices that have been silenced or absent from the earlier historical accounts, such as Indigenous, immigrant, or feminist voices. This highlights the value placed on the who rather than the what. In poetry, however, different individual participants exemplify different specialization codes across as well as within the themes. For instance, within the Making Connections theme in one interview, epistemic relations were stronger (focusing on the use of language and form to make novel connections), reflecting a knowledge code, whereas a separate interview reflected a knower code within this same theme, as the participant described using poetry to identify and connect with the local community. Finally, within Self-Expression, a strong theme only present in one participants’ interview, we observe a relativist code in LCT (

Figure 3), as the participant describes a space where “anything goes” (in terms of constructing poetry).

6. Discussion

In conducting this research, we sought to provide a conceptualization of creativity drawing on perceptions of creativity from participants of three academic disciplines. Uniting the experts’ accounts of creativity was the assertion that theirs was a creative discipline and that creativity was recognized as inherent to their disciplinary practices. This supports the longstanding understanding that all disciplines exhibit and are driven by creative acts [

34,

35]. Again, consistent with the extant literature, emerging themes included imagining solutions to problems and composing narratives [

8], seeing the world from new perspectives [

8], and making new or lateral connections [

9].

We draw on Specialization from Legitimation Code Theory to make sense of these descriptions. Specialization conceptualizes creativity in the different disciplines as exhibiting different relative values of epistemic relations (“what you know”) and social relations (“who you are”). Specialization is the most elaborated and enacted dimension in LCT, which itself is an emerging framework in education [

31]. In coding the perspectives of participants in relation to creativity, we present two main findings: first, that the nature of creativity is notably distinct in terms of the specialization codes observed. Discussions of creativity in physics show that the concept is understood to be relatively consistent and stable—a knowledge code. Creative acts occur, for instance, when connections are made between empirical measurements and existing or developing models and theories. Discussions of creativity were similar in nature for all three participants. In contrast, different aspects of creativity were discussed amongst both history and poetry experts as knowledge, knower, élite, and relativist codes, thus having a more varied quality (

Figure 3). For instance, historical creativity was discussed as representing a knowledge code, as connections were being made between different empirical sources. At the same time, creativity in history could also involve reconceptualising historical events through different lenses, such as feminist or Indigenous perspectives, constituting a knower code. Creativity was discussed most disparately amongst the poetry experts. A knowledge code perspective describes creativity as occurring when connections are made between the different strata (levels) of language, whilst creativity was also described as a knower code in that it was used as a way to make connections to community. In one interview, creativity in poetry was also described as a relativist code: “anything goes” (as long as it is a form of self-expression).

Differences in how creativity is perceived in each field and the consensus regarding those perceptions strongly implies that although the same language could be used to describe different facets of creativity, what they represent is substantially different, as they refract differently through distinct disciplinary architectures. Theoretically, we can thus describe practices as either having more transient/fluid architectures (poetry), with notions of creativity shifting between various specialization codes, or showing more consistency (physics) and reflecting notions of creativity that are more universally understood. It is understood that fields and social structures play a role in understanding creativity [

13,

26] and also that disciplinary differences influence the nature of creativity in these disciplines [

29,

30], but theorization of disciplinary knowledge does not constitute a large part of creativity research.

Ultimately, this work aims to bring clarity to the notion of creativity so that it might be more fruitfully discussed in higher education contexts. There has been considerable work focused on describing creativity, e.g., [

19,

20,

21], but we know that these descriptions remain variously interpreted and differently emphasized, meaning it is difficult to conclude to what degree each is present or foregrounded in any specific context and why [

10,

22]. Further, researchers argue that theoretical descriptions remain difficult to utilize in practice [

15,

16,

17], and perhaps accordingly, the considerable work in the field of creativity has so far failed to produce any meaningful change in teaching and learning [

7]. The status quo in higher education is identified as a lack of expression of creative outcomes at the subject level [

8] or an overly generic representation of creativity as a “soft skill” or graduate attribute that is rarely assured [

6]. In order for creative outcomes to be effectively fostered, creative outcomes must be explicitly stated in curricula, assessed, and taught [

6]. As a sociological framework, LCT’s power is in revealing “what lies beneath.” That acts of creativity need to be intelligible within the field of study (whether that be physics, history, or poetry) is important, as otherwise, creative contributions may not be recognized as such in the discipline (and vice-versa) [

36]. Accordingly, and as universities become more centralized and interdisciplinary, consideration of the organizing principles of the disciplines is apt in order to understand creativity both within and across fields and, in particular, in order to express and foster creativity in teaching and learning.