An Integrated Achievement and Mentoring (iAM) Model to Promote STEM Student Retention and Success

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Frameworks

2.1. Legitimate Peripheral Participation

2.2. Inclusivity, Community, and Belonging

2.3. Inclusivity

2.4. Community

2.5. Belonging

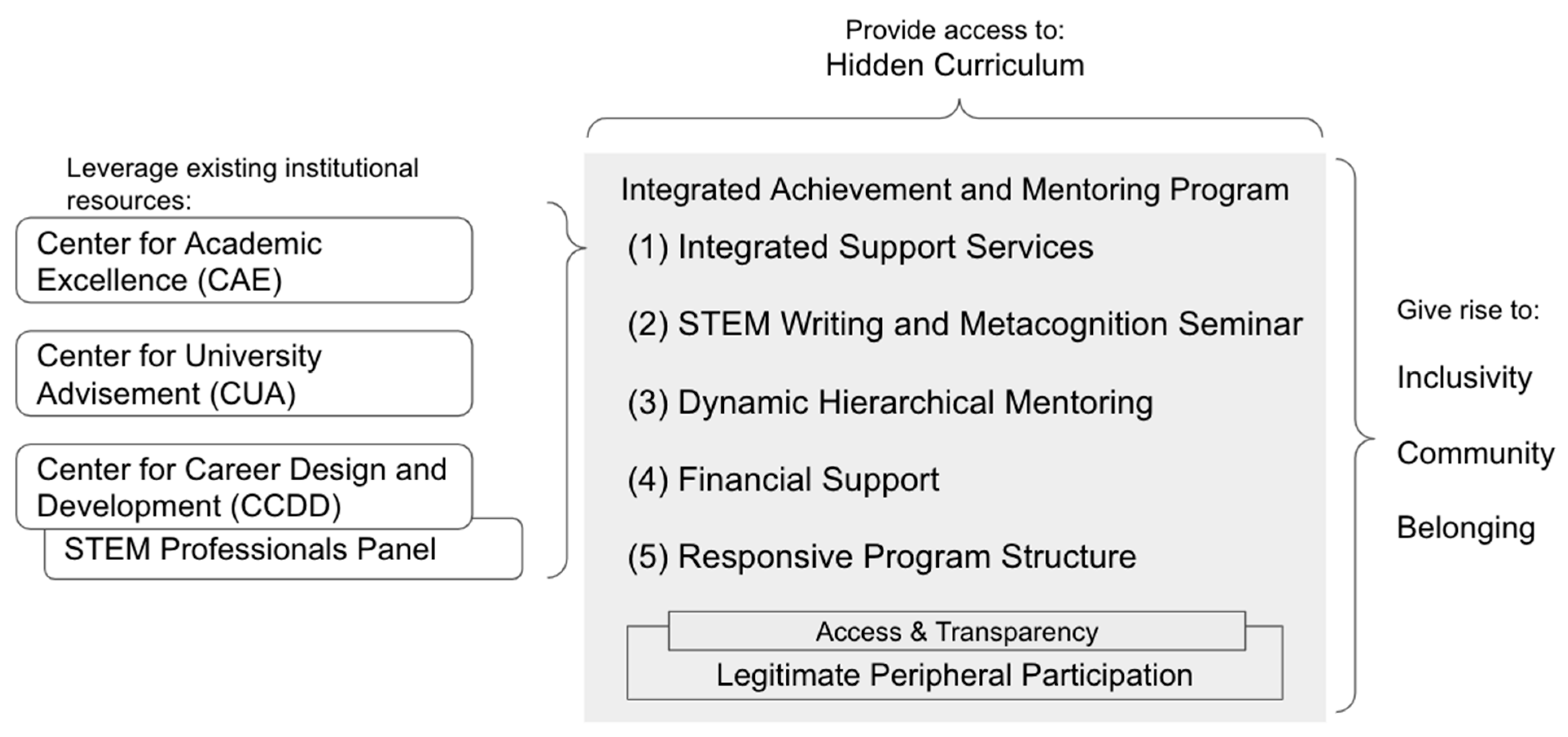

3. The iAM Program

3.1. Integrated Support Services

3.1.1. Success Workshops

3.1.2. STEM Professionals Panel

3.2. STEM Writing and Metacognition Seminar

3.3. Dynamic Hierarchical Mentoring

3.4. Financial Support for Pell-Eligible Students

3.5. Responsive Program Structure

3.6. All Program Events

3.7. Integration of Theoretical Frameworks with Program Implementation

4. Materials & Methods

4.1. Scholar Selection

- (1)

- Career goals: “State your career goals (50 words). Then make a bulleted list of the strategies you are using to meet these goals with a 10–25 word explanation for why you are employing each strategy.”

- (2)

- Academic success “How do you define academic success? (50 words) How well did you meet your definition of academic success before Hofstra? At Hofstra? Why? (100–200 words).”

- Tell us about your transition from high school to college—what was it like?

- What was your approach to your classes in the fall?

- What campus resources were you able to use on campus; tell us about your experiences with them?

- What is your plan for the upcoming semester to achieve academic success?

4.2. Program Outcomes

4.3. Program Cost/Benefit Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Program Outcomes

5.2. Program Cost/Benefit Analysis

6. Conclusions

- Avoid predicting who will succeed versus who will struggle in the first semester of college. Rather, identify students who actually struggle in that first semester. This provides better use of resources as it targets intervention to students who would most benefit.

- Look closely at the historical and current context of the institution to determine:

- Where critical attrition points exist;

- What skills might best support students in your context;

- What resources currently exist;

- How existing resources are organized.

- Utilize the LPP, inclusivity, belonging, and community frameworks to guide decisions about program structure:

- Ensure access;

- Provide transparency (visibility and invisibility);

- Recognize that access and transparency are necessary but not sufficient.

- Restructure existing resources as necessary (e.g., integrating support services).

- Provide a mechanism early in each student’s engagement with the iAM Program in which to provide access to resources and address the skills identified as important (e.g., the STEM Writing and Metacognition Seminar).

- Encourage relationship building among peers and faculty with structured opportunities for students to become invested in the community (e.g., dynamic hierarchical mentoring).

- Create a program structure that is responsive to the needs of students. This could be part of a formal knowledge generation component as we have at our institution or it could be more informal.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook, Table 1.11 Employment in STEM Occupations, 2021 and Projected 2031. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/stem-employment.htm (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Shapiro, H.; Ostergaard, S.F.; Hougaard, K.F. Does the EU Need More STEM Graduates?: Final Report|VOCEDplus, the International Tertiary Education and Research Database (p. 76) 2015, Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv:72530 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Independent Evaluation Group. Higher Education for Development: An Evaluation of the World Bank Group’s Support. 2017. World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/26486 (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Roemer, C.; Rundle-Thiele, S.; Pang, B.; David, P.; Kim, J.; Durl, J.; Dietrich, T.; Carins, J. Rewiring the STEM pipeline—A C-B-E framework to female retention. J. Soc. Mark. 2020, 10, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeke, I.N.; Babalola, C.P.; Byarugaba, D.K.; Djimde, A.; Osoniyi, O.R. Broadening Participation in the Sciences within and from Africa: Purpose, Challenges, and Prospects. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2017, 16, es2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- U.S. Department of Education; Institute of Education Sciences; National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of Education Statistics. Table 326.10. Graduation Rate from First Institution Attended for First-Time, Full-Time Bachelor’s Degree-Seeking Students at 4-Year Postsecondary Institutions, by Race/Ethnicity, Time to Completion, Sex, Control of Institution, and Percentage of Applications Accepted: Selected Cohort Entry Years, 1996 through 2013; 2020. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d20/tables/dt20_326.10.asp (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Chen, X. STEM Attrition: College Students’ Paths into and out of STEM Fields (NCES 2014-001); National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, C.S.; Kirsch, A.C.; Dickson, D.A.; Bryant, F.B. Negotiating the Transition to College: Developmental Trajectories and Gender Differences in Psychological Functioning, Cognitive-Affective Strategies, and Social Well-Being. Emerg. Adulthood 2014, 2, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffords, J.R.; Bayly, B.L.; Bumpus, M.F.; Hill, L.G. Investigating the Relationship Between University Students’ Psychological Flexibility and College Self-Efficacy. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2020, 22, 351–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, D.T. The Challenge of College Readiness. Educ. Leadersh. 2007, 64, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fanetti, S.; Bushrow, K.M.; DeWeese, D.L. Closing the Gap between High School Writing Instruction and College Writing Expectations. Engl. J. 2010, 99, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Conley, D.T. Mixed Messages: What State High School Tests Communicate about Student Readiness for College; College and Career Readiness and Success Center: Eugene, Oregon, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, S.Y. The Impact of Supplemental Instruction on Teaching Students How to Learn. New Dir. Teach. Learn. 2006, 106, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson Laird, T.F.; Shoup, R.; Kuh, G.D.; Schwarz, M.J. The Effects of Discipline on Deep Approaches to Student Learning and College Outcomes. Res. High Educ. 2008, 49, 469–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newmann, F.M. Authentic Achievement: Restructuring Schools for Intellectual Quality, 1st ed.; The Jossey-Bass education series; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1996; ISBN 978-0-7879-0320-6. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, T.W.; Colby, S.A. Teaching for Deep Learning. Clear. House A J. Educ. Strateg. Issues Ideas 2007, 80, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherif, A.; Wideen, M. The Problems of Transition from High School to University Science. BC Catal. 1992, 36, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis, E. The Hidden Curriculum in Higher Education; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2001; ISBN 978-0-415-92759-8. [Google Scholar]

- Orón Semper, J.V.; Blasco, M. Revealing the Hidden Curriculum in Higher Education. Stud. Philos. Educ. 2018, 37, 481–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, J.W.; Lowenthal, P.R. Academic Discourse and the Formation of an Academic Identity: Minority College Students and the Hidden Curriculum. High. Educ. 2011, 34, 283–318. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.W. Sociolinguistic Challenges to Minority Collegiate Success: Entering the Discourse Community of the College. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2005, 6, 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, R. Towards a Clearer Understanding of Student Disadvantage in Higher Education: Problematising Deficit Thinking. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2012, 31, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, J. Social Linguistics and Literacies: Ideology in Discourses; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-317-52519-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, B. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control, and Identity; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-1-4616-3620-5. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, W. Bounds of Democracy: Epistemological Access in Higher Education; HSRC Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Matt, G.E.; Pechersky, B.; Cervantes, C. High School Study Habits and Early College Achievement. Psychol. Rep. 1991, 69, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, M.C.; Chung, O.L. Relationship of Study Strategies and Academic Performance in Different Learning Phases of Higher Education in Hong Kong. Educ. Res. Eval. 2005, 11, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, M.E.; Wilson, G.S. Using Emotional and Social Factors to Predict Student Success. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2003, 44, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdes, H.; Mallinckrodt, B. Emotional, Social, and Academic Adjustment of College Students: A Longitudinal Study of Retention. J. Couns. Dev. 1994, 72, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayhorn, T.L. College Students’ Sense of Belonging: A Key to Educational Success for All Students; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- van Herpen, S.G.A.; Meeuwisse, M.; Hofman, W.H.A.; Severiens, S.E. A Head Start in Higher Education: The Effect of a Transition Intervention on Interaction, Sense of Belonging, and Academic Performance. Stud. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 862–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santangelo, J.; Cadieux, M.; Zapata, S. Developing Student Metacognitive Skills Using Active Learning Embedded with Metacognition Instruction. J. STEM Educ. Innov. Res. 2021, 22, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Balduf, M. Underachievement among College Students. J. Adv. Acad. 2009, 20, 274–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bromberg, M.; Theokas, C. Meandering toward Graduation: Transcript Outcomes of High School Graduates. Educ. Trust 2016, 1–14. Available online: https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/MeanderingTowardGraduation_EdTrust_April2016.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Olson, S.; Riordan, D. Engage to Excel: Producing One Million Additional College Graduates with Degrees in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics. Report to the President; Executive Office of the President: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rask, K. Attrition in STEM Fields at a Liberal Arts College: The Importance of Grades and Pre-Collegiate Preferences. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2010, 29, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ost, B. The Role of Peers and Grades in Determining Major Persistence in the Sciences. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2010, 29, 923–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, S.; Carter, D.F.; Spuler, A. Latino Student Transition to College: Assessing Difficulties and Factors in Successful College Adjustment. Res. High Educ. 1996, 37, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pascarella, E.T.; Pierson, C.T.; Wolniak, G.C.; Terenzini, P.T. First-Generation College Students: Additional Evidence on College Experiences and Outcomes. J. High. Educ. 2004, 75, 249–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayhorn, T.L. Factors Influencing the Academic Achievement of First-Generation College Students. J. Stud. Aff. Res. Pract. 2007, 43, 1278–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terenzini, P.T.; Springer, L.; Yaeger, P.M.; Pascarella, E.T.; Nora, A. First-Generation College Students: Characteristics, Experiences, and Cognitive Development. Res. High. Educ. 1996, 37, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, J.; Bulakowski, C.; Jumisko, M. A Study of White, Black, and Hispanic Students’ Transition to a Community College. Community Coll. Rev. 1998, 26, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, T.; Parker, S. Navigating Change: A Typology of Student Transition in Higher Education. Stud. High. Educ. 2014, 39, 734–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venezia, A.; Jaeger, L. Transitions from High School to College. Future Child. 2013, 23, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consalvo, A.L.; Schallert, D.L.; Elias, E.M. An Examination of the Construct of Legitimate Peripheral Participation as a Theoretical Framework in Literacy Research. Educ. Res. Rev. 2015, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaffini, E.J. Communities of Practice and Legitimate Peripheral Participation: A Literature Review. Update Appl. Res. Music Educ. 2018, 36, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spouse, J. Learning to Nurse Through Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Nurse Educ. Today 1998, 18, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, R.K.; Zegwaard, K.E. Enculturation into Engineering Professional Practice: Using Legitimate Peripheral Participation to Develop Communication Skills in Engineering Students. Available online: https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/content/www.igi-global.com/chapter/content/64005 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Park, J.Y. Student Interactivity and Teacher Participation: An Application of Legitimate Peripheral Participation in Higher Education Online Learning Environments. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2015, 24, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Donnell, V.L.; Tobbell, J. The Transition of Adult Students to Higher Education: Legitimate Peripheral Participation in a Community of Practice? Adult Educ. Q. 2007, 57, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teeuwsen, P.; Ratković, S.; Tilley, S.A. Becoming Academics: Experiencing Legitimate Peripheral Participation in Part-Time Doctoral Studies. Stud. High. Educ. 2014, 39, 680–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curnow, J. Climbing the Leadership Ladder: Legitimate Peripheral Participation in Student Movements. Interface A J. Soc. Mov. 2014, 6, 130–155. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B.F. Science and Human Behavior; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. Mind in Society. The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Asai, D.J.; Bauerle, C. From HHMI: Doubling Down on Diversity. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2016, 15, fe6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bangera, G.; Brownell, S.E. Course-Based Undergraduate Research Experiences Can Make Scientific Research More Inclusive. LSE 2014, 13, 602–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borda, E.; Schumacher, E.; Hanley, D.; Geary, E.; Warren, S.; Ipsen, C.; Stredicke, L. Initial Implementation of Active Learning Strategies in Large, Lecture STEM Courses: Lessons Learned from a Multi-Institutional, Interdisciplinary STEM Faculty Development Program. Int. J. STEM Educ. 2020, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton-Pedersen, A.; Sonja, C.-P. Making Excellence Inclusive in Education and Beyond. Pepp. L. Rev. 2007, 35, 611. [Google Scholar]

- Gopalan, M.; Brady, S.T. College Students’ Sense of Belonging: A National Perspective. Educ. Res. 2019, 49, 0013189X19897622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killpack, T.L.; Melón, L.C. Toward Inclusive STEM Classrooms: What Personal Role Do Faculty Play? CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2016, 15, es3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nostrand, D.F.-V.; Pollenz, R.S. Evaluating Psychosocial Mechanisms Underlying STEM Persistence in Undergraduates: Evidence of Impact from a Six-Day Pre–College Engagement STEM Academy Program. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2017, 16, ar36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Sullivan, K.; Bird, N.; Robson, J.; Winters, N. Academic Identity, Confidence and Belonging: The Role of Contextualised Admissions and Foundation Years in Higher Education. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 45, 554–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, L.R.; Ye, F.; Schofield, J.W.; Woods, R.L. Sense of Belonging and Persistence in White and African American First-Year Students. Res. High. Educ. 2009, 50, 649–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, S.; Carter, D.F. Effects of College Transition and Perceptions of the Campus Racial Climate on Latino College Students’ Sense of Belonging. Sociol. Educ. 1997, 70, 324–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.A.; Berger, J.B.; McClendon, S.A. Toward a Model of Inclusive Excellence and Change in Postsecondary Institutions; American Association of Colleges and Universities: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer, E. Campus Life: In Search of Community; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Z.S.; Holmes, L.; deGravelles, K.; Sylvain, M.R.; Batiste, L.; Johnson, M.; McGuire, S.Y.; Pang, S.S.; Warner, I.M. Hierarchical Mentoring: A Transformative Strategy for Improving Diversity and Retention in Undergraduate STEM Disciplines. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2012, 21, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education; Institute of Education Sciences; National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of Education Statistics. Table 326.27. Number of Degree/Certificate-Seeking Undergraduate Students Entering a Postsecondary Institution and Percentage of Students 4, 6, and 8 Years after Entry, by Completion and Enrollment Status at the Same Institution, Institution Level and Control, Attendance Level and Status, Pell Grant Recipient Status, and Acceptance Rate: Cohort Entry Year 2011; 2020. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d20/tables/dt20_326.27.asp (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Grillo, M.C.; Leist, C.W. Academic Support as a Predictor of Retention to Graduation: New Insights on the Role of Tutoring, Learning Assistance, and Supplemental Instruction. J. Coll. Stud. Retent. Res. Theory Pract. 2013, 15, 387–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotkowski, V.A.; Robbins, S.B.; Noeth, R.J. The Role of Academic and Non-Academic Factors in Improving College Retention; ACT Policy Report; American College Testing ACT Inc.: Lubbock, TX, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ruscetti, T.; Krueger, K.; Sabatier, C. Improving Quantitative Writing One Sentence at a Time. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coil, D.; Wenderoth, M.P.; Cunningham, M.; Dirks, C. Teaching the Process of Science: Faculty Perceptions and an Effective Methodology. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2010, 9, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stanton, J.D.; Neider, X.N.; Gallegos, I.J.; Clark, N.C. Differences in Metacognitive Regulation in Introductory Biology Students: When Prompts Are Not Enough. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2015, 14, ar15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cook, E.; Kennedy, E.; McGuire, S.Y. Effect of Teaching Metacognitive Learning Strategies on Performance in General Chemistry Courses. J. Chem. Educ. 2013, 90, 961–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterholt, D.A.; Dennis, S.L. Assessing and Addressing Student Barriers: Implications for Today’s College Classroom. About Campus 2014, 18, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtner, J. The Use of Discriminant Analysis to Investigate the Influence of Non-Cognitive Factors on Engineering School Persistence. J. Eng. Educ. 2005, 94, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Taddese, N.; Walter, E. Entry and Persistence of Women and Minorities in College Science and Engineering Education. Research and Development Report. NCES 2000-601. National Center for Education Statistics. 2000. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2000/2000601.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2022).

- Campbell, T.A.; Campbell, D.E. Faculty/Student Mentor Program: Effects on Academic Performance and Retention. Res. High. Educ. 1997, 38, 727–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown II, M.C.; Davis, G.L.; McClendon, S.A. Mentoring Graduate Students of Color: Myths, Models, and Modes. Peabody J. Educ. 1999, 74, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, J.R. Mentors in Life and at School: Impact on Undergraduate Protege Perceptions of University Mission and Values. Mentor. Tutoring Partnersh. Learn. 2004, 12, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.M.; Major, D.A.; Orvis, K.A. Understanding How Peer Mentoring and Capitalization Link STEM Students to Their Majors. Career Dev. Q. 2012, 60, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrion, J.L.; Leonard, D. A Taxonomy of the Characteristics of Student Peer Mentors in Higher Education: Findings from a Literature Review. Mentor. Tutoring 2007, 15, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cole, S.; Barber, E.G. Increasing Faculty Diversity; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-674-00945-5. [Google Scholar]

- Nettles, M.T.; Thoeny, A.R. Toward Black Undergraduate Student Equality in American Higher Education; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0-313-25616-5. [Google Scholar]

- Treisman, U. Studying Students Studying Calculus: A Look at the Lives of Minority Mathematics Students in College. Coll. Math. J. 1992, 23, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, C.D. Calming Fears and Building Confidence: A Mentoring Process That Works. Mentor. Tutoring 2001, 9, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorte, C.J.B.; Aguilar-Roca, N.M.; Henry, A.K.; Pratt, J.D. A Hierarchical Mentoring Program Increases Confidence and Effectiveness in Data Analysis and Interpretation for Undergraduate Biology Students. LSE 2020, 19, ar23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handelsman, J.; Lauffer, S.M.; Pribbenow, C.M.; Pfund, C. (Eds.) Entering Mentoring: A Seminar to Train a New Generation of Scientists, 1st ed.; Itchy Cat Press: Madison, WI, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-9815161-1-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pfund, C.; Pribbenow, C.M.; Branchaw, J.; Lauffer, S.M.; Handelsman, J. The Merits of Training Mentors. Science 2006, 311, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartup, W.W. Social Relationships and Their Developmental Significance. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.L.; Elreda, L.M.; Henderson, L.J.; Deutsch, N.L.; Lawrence, E.C. Dyadic Connections in the Context of Group Mentoring: A Social Network Approach. J. Community Psychol. 2019, 47, 1184–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All N = 18,492 | Non-STEM N = 14,052 | STEM N = 4440 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pell-eligible | 27% | 25% | 33% |

| White | 57% | 60% | 46% |

| Asian | 10% | 8% | 17% |

| Hispanic | 15% | 14% | 16% |

| Black | 10% | 9% | 12% |

| Native Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander | 0.6% | 0.5% | 1% |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.6% |

| Two or More | 3% | 3% | 3% |

| Not Reported | 5% | 5% | 4% |

| Retention to Year 2 (2011–2020) | 4 Year Grad (2011–2017) | 6 Year Grad (2011–2015) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-STEM | STEM | Non-STEM | STEM | Non-STEM | STEM | |

| Total | 79% | 76% | 57% | 47% | 63% | 57% |

| White/ Asian | 81% | 80% | 61% | 52% | 68% | 63% |

| Minoritized | 74% | 68% | 46% | 37% | 54% | 47% |

| Pell | 74% | 71% | 49% | 39% | 55% | 48% |

| Support Service | Description of Service |

|---|---|

| Center for Academic Excellence (CAE) | Supports student academic and personal success through one-on-one advising, tutoring, and workshops |

| Center for University Advising (CUA) | Provides academic advising regarding campus policies, academic planning, and major exploration. |

| Center for Career Design and Development (CCDD) | Offers career counseling and programming to empower students to find, apply for, and be hired into professional careers |

| iAM Program Component | LPP | Community | Inclusivity | Belonging | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access | Transparency | ||||

| Integrated Support Services | |||||

| Success workshops | X | X | X | ||

| The iAM Program ensures ease of operation and use as existing institutional support services are integrated into Scholars’ college experience rather than Scholars seeking them out. In integrating success workshops into the iAM Program, the tools for academic and career success become visible to Scholars. | Success Workshops ensure consistent engagement with institutional support services. As such, they serve as a mechanism to promote retention, graduation, and STEM career entry. | ||||

| STEM Professionals Panel | X | X | X | X | X |

| The STEM Professionals Panel provides Scholars access to STEM professionals. Rather than requiring Scholars to seek out STEM professionals themselves, the iAM Program integrates engagement with professionals seamlessly into Scholars’ experience. In doing so, it makes visible to Scholars the breadth of potential STEM careers and exposes Scholars to established and emerging fields. | The STEM Professionals Panel promotes STEM career entry by exposing Scholars to the breadth of potential careers and offering networking opportunities through which Scholars begin to identify with the profession and the professionals. | ||||

| STEM Writing and Metacognition Seminar | X | X | X | X | X |

| The Seminar provides Scholars access to the hidden curriculum: the implicit expectations (e.g., go in office hours, talk to faculty, talk to upper division peers) and skills (e.g., how to write, how to study, how to communicate with faculty) for college success. Transparency is achieved both by making the hidden curriculum visible and via seamless integration into Scholars’ experiences. | The Seminar brings newcomers of the iAM community together in purposeful ways to provide equity for Scholars to connect, build relationships, and engage in the undergraduate STEM community. | ||||

| Dynamic Hierarchical Mentoring | X | X | X | X | X |

| DHM provides access to people and resources. Explicit inclusion of mentoring, as opposed to Scholars connecting with peers or faculty serendipitously, provides a pathway for Scholars to engage with the iAM Program, first as newcomers (mentees) and eventually as experts (mentors). Mentoring is, therefore, both visible as it is integrated into the iAM Program and invisible since Scholars are not required to seek out mentors. | DHM provides equitable opportunities to build relationships across the iAM community (upper-level students, faculty), develop identity related to STEM professions and professionals. | ||||

| Scholarships | X | X | |||

| Scholarships provide Pell-eligible students access to the institution. | Scholarships provide more equitable access to the university and a STEM degree. | ||||

| Responsive Program Structure | X | X | X | X | X |

| The responsive program structure provides Scholars voice to shape the iAM Program to meet their needs and claim ownership in the program. It provides a window into the program’s goals and structure. | The intent of the responsive program structure is to make the program more equitable through time, increase belonging and enhance community as Scholars provide actionable feedback to the program. | ||||

| Term | Comparison Retention Rate | Scholar Retention Rate | Number of Cohorts Used to Calculate Rates |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 to 3 | 73.2% | 100% | 3 |

| 3 to 4 | 100% | 91.3% | 3 |

| 4 to 5 | 91.4% | 76.9% | 2 |

| 5 to 6 | 93.8% | 110% | 2 |

| 6 to 7 | 105% | 100% | 1 |

| 7 to 8 | 90.0% | 100% | 1 |

| Projected Scholars lost | 9.73 | 5.46 | |

| Projected Revenue lost * | $1.27 M | $687 K | |

| Projected gross revenue benefit | $588 K | ||

| Projected university and grant investment | $476 K | ||

| Projected net revenue benefit | $112 K | ||

| Theoretical Foundations | |

|---|---|

| Frameworks Legitimate Peripheral Participation Shifts planning and implementation of program components away from a program-centered focus of resources offered and towards a student-centered focus on how students experience resources. Inclusivity, Belonging, Community Guide adjustments made to the program by maintaining a focus on Scholars’ experiences of these constructs. Frame program components within an achievement model Shifts the program focus away from “fixing” students and towards a focus on developing Scholar agency with the goal that student perception of interventions shifts from punitive to supportive. Approach Ground in an understanding of the institutional context Ensures that program components and structure are relevant to and appropriate for the institutional context and target population(s). | |

| Program Components | |

| Essential Each of the essential program components directly aligns with LPP in that each offers access and transparency to resources.

| Adaptable Each adaptable component is dependent on (1) an analysis of the institutional context, and (2) clearly articulated goals for the target population(s).

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santangelo, J.; Elijah, R.; Filippi, L.; Mammo, B.; Mundorff, E.; Weingartner, K. An Integrated Achievement and Mentoring (iAM) Model to Promote STEM Student Retention and Success. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 843. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120843

Santangelo J, Elijah R, Filippi L, Mammo B, Mundorff E, Weingartner K. An Integrated Achievement and Mentoring (iAM) Model to Promote STEM Student Retention and Success. Education Sciences. 2022; 12(12):843. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120843

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantangelo, Jessica, Rosebud Elijah, Lisa Filippi, Behailu Mammo, Emily Mundorff, and Kristin Weingartner. 2022. "An Integrated Achievement and Mentoring (iAM) Model to Promote STEM Student Retention and Success" Education Sciences 12, no. 12: 843. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120843

APA StyleSantangelo, J., Elijah, R., Filippi, L., Mammo, B., Mundorff, E., & Weingartner, K. (2022). An Integrated Achievement and Mentoring (iAM) Model to Promote STEM Student Retention and Success. Education Sciences, 12(12), 843. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12120843