Resilience in Higher Education: A Complex Perspective to Lecturers’ Adaptive Processes in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Resilience in Socio-Ecological Systems

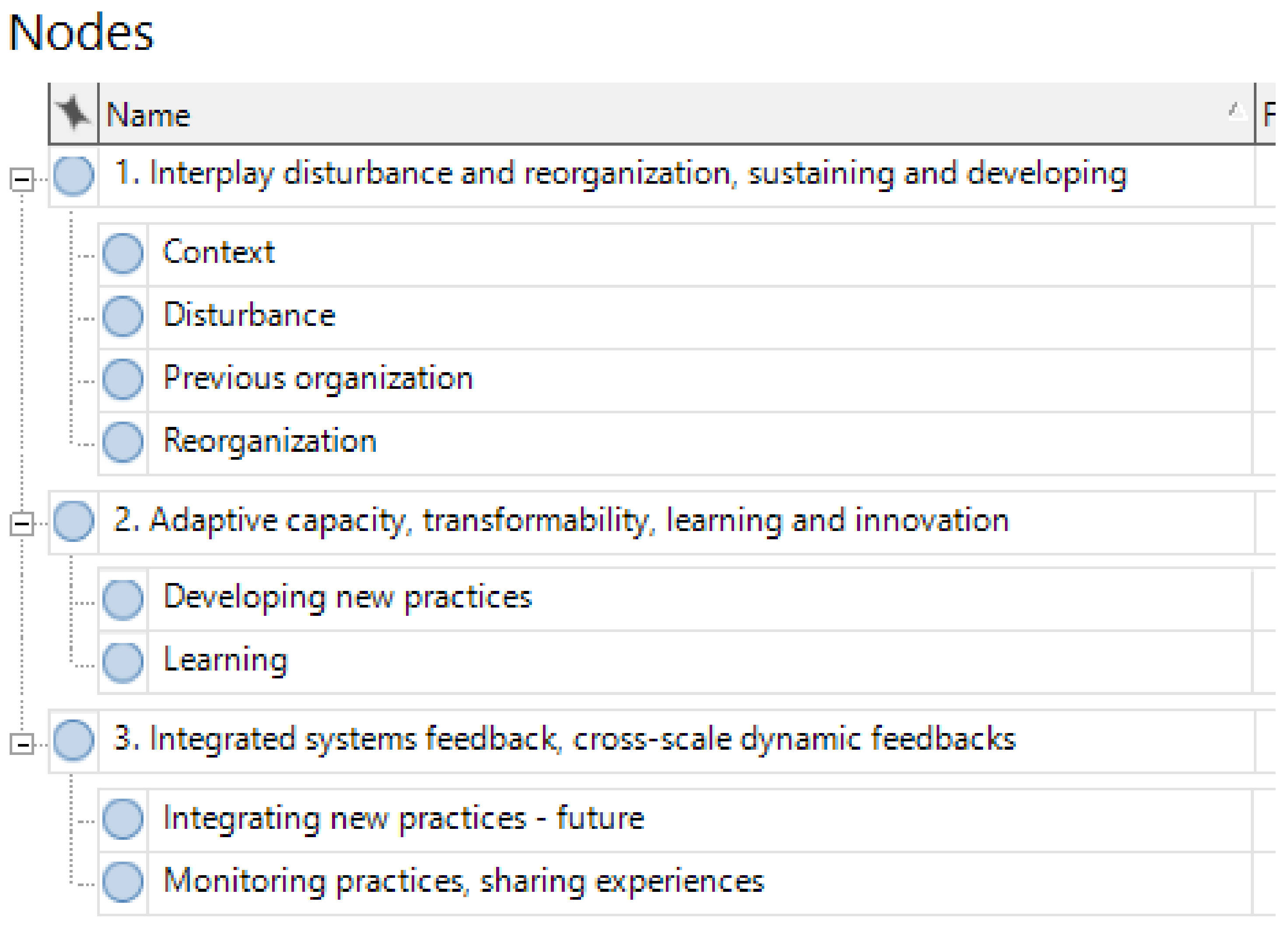

- Characteristics: interplay disturbance and reorganization, sustaining, and developing;

- Focus: adaptive capacity, transformability, learning, and innovation; and

- Context: integrated systems feedback and cross-scale dynamic feedback.

2.2. Resilience and Education

3. Methods

3.1. Data Gathering

3.2. Analysis and Ethics

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics: Interplay Disturbance and Reorganization, Sustaining, and Developing

4.2. Focus: Adaptive Capacity, Transformability, Learning and Innovation

4.3. Context: Integrated Systems Feedback, Cross-Scale Dynamic Feedbacks

4.4. Main Clusters of Findings and Recent Developments

5. Discussion

5.1. Lecturers’ Adaptive Processes

5.2. System Level Resilience in Higher Education

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- What was the moment that you became aware that the pandemic would bring implications for your activity as a lecturer?

- How did it change educational practices?

- What changes in interaction with students did you experience?

- What did you learn in this period?

- How was your interaction with colleagues in this period? Did you have the opportunity to discuss/share experiences?

- And with the university college management?

- How do you expect that this experience will bring changes to your activity as a lecturer in the future, post-pandemic?

References

- Unesco. Education Response. 2020. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Gupta, M.M.; Jankie, S.; Pancholi, S.S.; Talukdar, D.; Sahu, P.K.; Sa, B. Asynchronous Environment Assessment: A Pertinent Option for Medical and Allied Health Profession Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristovnik, A.; Keržič, D.; Ravšelj, D.; Tomaževič, N.; Umek, L. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Life of Higher Education Students: A Global Perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peimani, N.; Kamalipour, H. Online Education and the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Case Study of Online Teaching during Lockdown. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.M.; Goh, C.; Lim, L.Z.; Gao, X. COVID-19 Emergency eLearning and Beyond: Experiences and Perspectives of University Educators. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adov, L.; Mäeots, M. What Can We Learn about Science Teachers’ Technology Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic? Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S.; Chhetri, R. A Literature Review on Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Teaching and Learning. High. Educ. Future 2021, 8, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, S.; Alsharari, N.M.; Abbas, J.; Alshurideh, M.T. From Offline to Online Learning: A Qualitative Study of Challenges and Opportunities as a Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic in the UAE Higher Education Context. In The Effect of Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) on Business Intelligence; Alshurideh, M., Hassanien, A.E., Masa’deh, R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 334, pp. 203–217. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bento, F.C. The contribution of complexity theory to the study of departmental leadership in processes of organisational change in higher education. Int. J. Complex. Leadersh. Manag. 2011, 1, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Axelrod, R.; Cohen, M.D. Harnessing Complexity; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.H. Complex adaptive systems. Daedalus 1992, 121, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.H. Hidden Order: How Adaptation Builds Complexity; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop, M.M.; Stein, D. Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos. Phys. Today 1992, 45, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preiser, R. Identifying general trends and patterns in complex systems research: An overview of theoretical and practical implications. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2019, 36, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Domenico, M.; Brockmann, D.; Camargo, C.Q.; Gershenson, C.; Goldsmith, D.; Jeschonnek, S.; Lorren, K.; Nichele, S.; Nicolás, J.R.; Schmickl, T.; et al. Complexity Explained. 2019. Available online: https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10871/124302/ComplexityExplained.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Heylighen, F. The science of self-organization and adaptivity. Encycl. Life Support Syst. 2001, 5, 253–280. [Google Scholar]

- Krispin, J.V. Positive Feedback Loops of Metacontingencies: A New Conceptualization of Cultural-Level Selection. Behav. Soc. Issues 2017, 26, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouad, J.; Bento, F. A Complexity Perspective on Parent–Teacher Collaboration in Special Education: Narratives from the Field in Lebanon. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Centola, D. How Behavior Spreads: The Science of Complex Contagions; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchek, S. Organizational resilience: A capability-based conceptualization. Bus. Res. 2020, 13, 215–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berkes, F. Environmental Governance for the Anthropocene? Social-Ecological Systems, Resilience, and Collaborative Learning. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walker, B.; Gunderson, L.; Kinzig, A.; Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.; Schultz, L. A handful of heuristics and some propositions for understanding resilience in social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D.P.; Bestelmeyer, B.T.; Turner, M.G. Cross–scale interactions and changing pattern–process relationships: Conse-quences for system dynamics. Ecosystems 2007, 10, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, S. Ecosystems and the Biosphere as Complex Adaptive Systems. Ecosystems 1998, 1, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.R.; Walker, B.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, T.; Rockström, J. Resilience Thinking: Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K. Educational Philosophy and the Challenge of Complexity Theory. Educ. Philos. Theory 2008, 40, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Folke, C.; Berkes, F. Adaptive Comanagement for Building Resilience in Social? Ecological Systems. Environ. Manag. 2004, 34, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandaker, I. A Selectionist Perspective on Systemic and Behavioral Change in Organizations. J. Organ. Behav. Manag. 2009, 29, 276–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J. The evolution of evolution. In Evolutionary Dynamics of Organizations, 1st ed.; Baum, J., Singh, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Flach, F.F. Resilience: The Art of Being Flexible; Saraiva: São Paulo, Brazil, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, M.T.S.; Cerveny, C.M.O. Psychological resilience: Literature review and analysis of scientific production. Inter-Am. J. Psychol. 2006, 40, 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, I. Vulnerability and resilience. Lat. Am. Adolesc. 2001, 2, 128–130. [Google Scholar]

- Tardif, M.; Lessard, C. Teaching Work: Elements for a Theory of Teaching as a Profession of Human Interactions; Vozes: Petrópolis, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S. Introduction to qualitative research. In Qualitative Research in Practice. Examples for Discussion and Analysis, 1st ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoukas, H.; Hatch, M.J. Complex Thinking, Complex Practice: The Case for a Narrative Approach to Organizational Complexity. Hum. Relat. 2001, 54, 979–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. Doing Interviews; Sage: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, G.R. Qualitative Data Analysis: Explorations with NVivo, 1st ed.; Open University: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J. Social Network Analysis, 3rd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Parise, S. Knowledge Management and Human Resource Development: An Application in Social Network Analysis Methods. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2007, 9, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Mehra, A.; Brass, D.J.; Labianca, G. Network Analysis in the Social Sciences. Science 2009, 323, 892–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Codes | Extracts from Interviews |

|---|---|

| Context | “I first became aware of the situation when physical lectures were cancelled. I thought we would be able to continue in classrooms, even if keeping physical distance, wearing masks, using sanitizers, and so on. I didn’t expect that we would ever reach the point that we would have to move lectures to online platforms. It was very sad and painful then.” (Participant A) |

| Previous organization | “As I understand, the senior management of the university college had always had a good relationship with the lecturers, and this has been kept during the pandemic. They always listen and give us feedback. This hasn’t changed during the pandemic.” (Participant A) |

| Disturbance | “I first understood the seriousness of the situation when classes were cancelled. I remember wondering how I would be able to teach Calculus with slides. I got desperate. This was the moment when I realized that I would have to rethink the whole semester, even if my course plan was already being implemented. My strategy simply would not work remotely.” (Participant E) |

| Reorganization | “Each one of us started creating one’s own way of lecturing. I tried to understand the limiting conditions of my students in order to adapt myself to their scarce resources. This was very challenging. Some students lived in remote areas with bad internet coverage, or didn’t have a computer suitable to follow online lectures. This was very demanding, but these things started settling down after a while.” (Participant B) |

| Codes | Extracts from Interviews |

|---|---|

| New practices | “I understood that I had to improve my classes in order to make these more stimulating and, thereby, facilitating student participation. I have used more games, group dynamics, and questions to individual students during classes” (Participant A) |

| “I had to adapt my teaching to the restricted access to technological resources and internet faced by many of my students. Some students live in remote areas with bad internet coverage, and some do not even have computers. This was very demanding in the beginning, but we have adapted.” (Participant B) | |

| “I had to learn new technological tools and this was very important because otherwise we wouldn’t have lectures. Before we would go to the classroom, look at the student and ask them how the class went. Now we can’t interact in this way. We have to use more WhatsApp and now sometimes I receive pictures of assignments from students who need my help. Beyond that, I had to learn to edit videos and use learning platforms beyond simply storing teaching material.” (Participant H) | |

| Learning | “The main change here was to see myself in the shoes of the student and to see the situation from their perspective. They have bad internet coverage and sometimes have to send to some of their assignment in a hurry because their data package may expire. Sometimes they have to feed their families while attending lectures. Sometimes there was only one computer for the whole family.” (Participant G) |

| “I had to learn that education goes way beyond the classroom situation. There is the wide social context that we have to understand. I have always tried to use new teaching methods but now I understand much more how heterogeneous my students are.” (Participant D) | |

| “I have learned a lot in relation the social dimensions of education. In a normal classroom situation, we do not observe the same problems. In this new context, although physically distant, we can get closer to the students. Sometimes we realize that we lived in a bubble and that reality is much broader than we thought. I have a closer contact with students now and see how they struggle to pursue a higher education degree due to their economic situation or lack of access to technological resources.” (Participant F) | |

| “I learned a lot, but the most important was in terms of empathy. It may sound strange to talk about empathy when we are looking at a computer screen, but the truth is that interacting with students in this context made me realize that they feel the same as us: unsafe and uncertain about the future.” (Participant K) |

| Codes | Extracts from Interviews |

|---|---|

| Monitoring results | “We exchanged experiences as lectures were being conducted. We looked like the students trying to follow online classes. This was our reality: teachers exchanging experiences and trying to adapt new tools. It was nice to see the reciprocity as we were also trying to help each other. I think that distance teaching got us closer, as paradoxical as it may look.” (Participant B) |

| “I had some informal meetings with colleagues but this could have been further explored in the context that we are living. Technology could have been used to promote interaction among us lecturers. This was already difficult before the pandemic. The university college could have created more arenas to discuss experiences during the pandemic.” (Participant B) | |

| Integrating new practices | “I think that the pandemic created a new momentum for distance teaching and we lecturers will need to prepare ourselves for this new reality. This will not regress.” (Participant B) |

| “Before the pandemic, I would often tell my students: ‘This is a technological tool and you have to work it out’. I will not do that anymore. We are not here just to say a few things about Economics or Law. We are here to understand the students” (Participant E) |

| Areas of Findings. The Emergence of: | Participants | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Exploration/Innovation | 12 | 100% |

| Informal feedback systems: groups for experience sharing/discussions | 8 | 66.6% |

| Awareness of the students’ socio-economic environment | 8 | 66.6% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bento, F.; Giglio Bottino, A.; Cerchiareto Pereira, F.; Forastieri de Almeida, J.; Gomes Rodrigues, F. Resilience in Higher Education: A Complex Perspective to Lecturers’ Adaptive Processes in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090492

Bento F, Giglio Bottino A, Cerchiareto Pereira F, Forastieri de Almeida J, Gomes Rodrigues F. Resilience in Higher Education: A Complex Perspective to Lecturers’ Adaptive Processes in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Education Sciences. 2021; 11(9):492. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090492

Chicago/Turabian StyleBento, Fabio, Andréa Giglio Bottino, Felipe Cerchiareto Pereira, Janimayri Forastieri de Almeida, and Fabiana Gomes Rodrigues. 2021. "Resilience in Higher Education: A Complex Perspective to Lecturers’ Adaptive Processes in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic" Education Sciences 11, no. 9: 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090492

APA StyleBento, F., Giglio Bottino, A., Cerchiareto Pereira, F., Forastieri de Almeida, J., & Gomes Rodrigues, F. (2021). Resilience in Higher Education: A Complex Perspective to Lecturers’ Adaptive Processes in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Education Sciences, 11(9), 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090492