Assessing Performance and Engagement on a Computer-Based Education Platform for Pharmacy Practice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

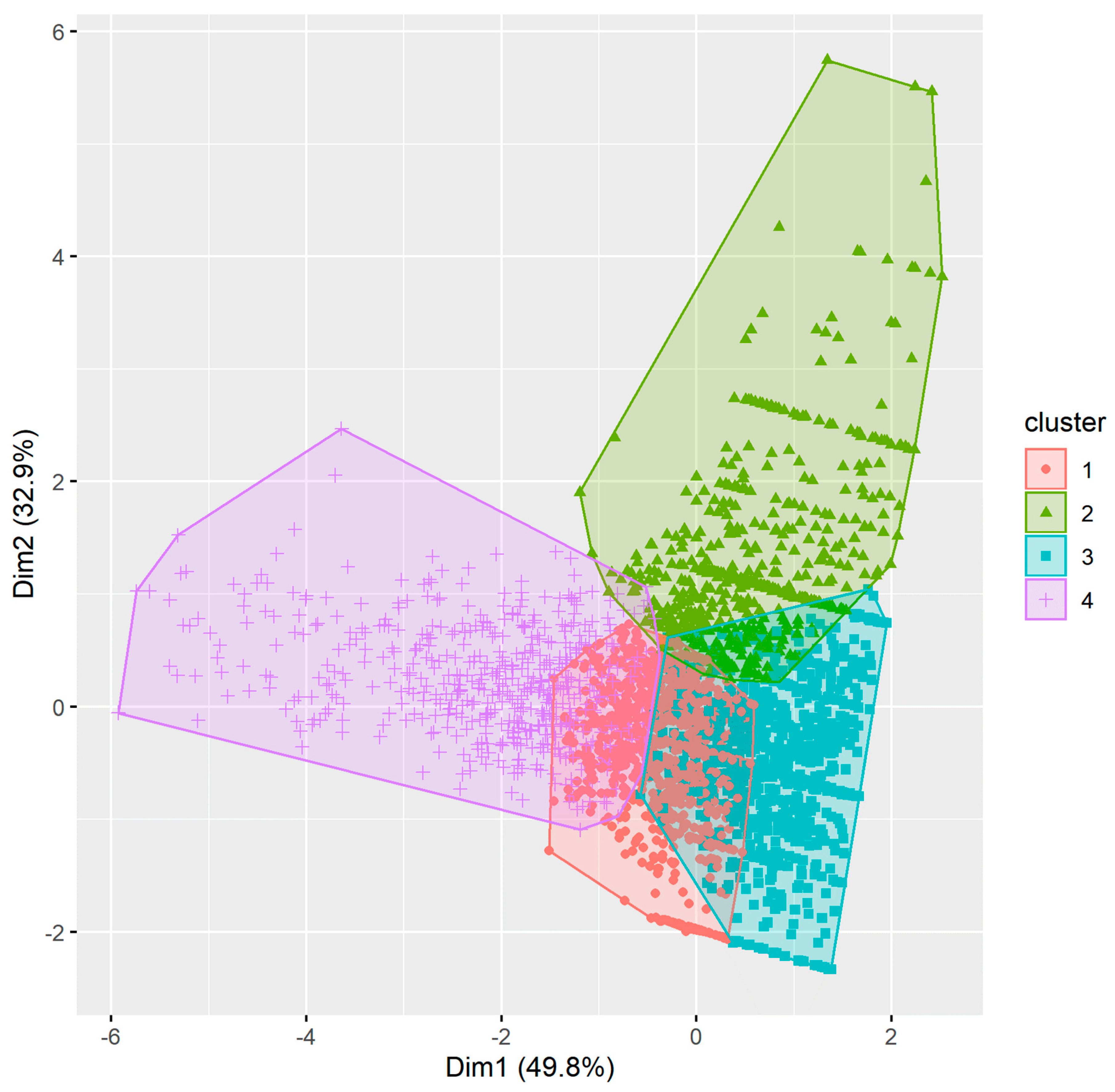

3.1. Cluster Analysis

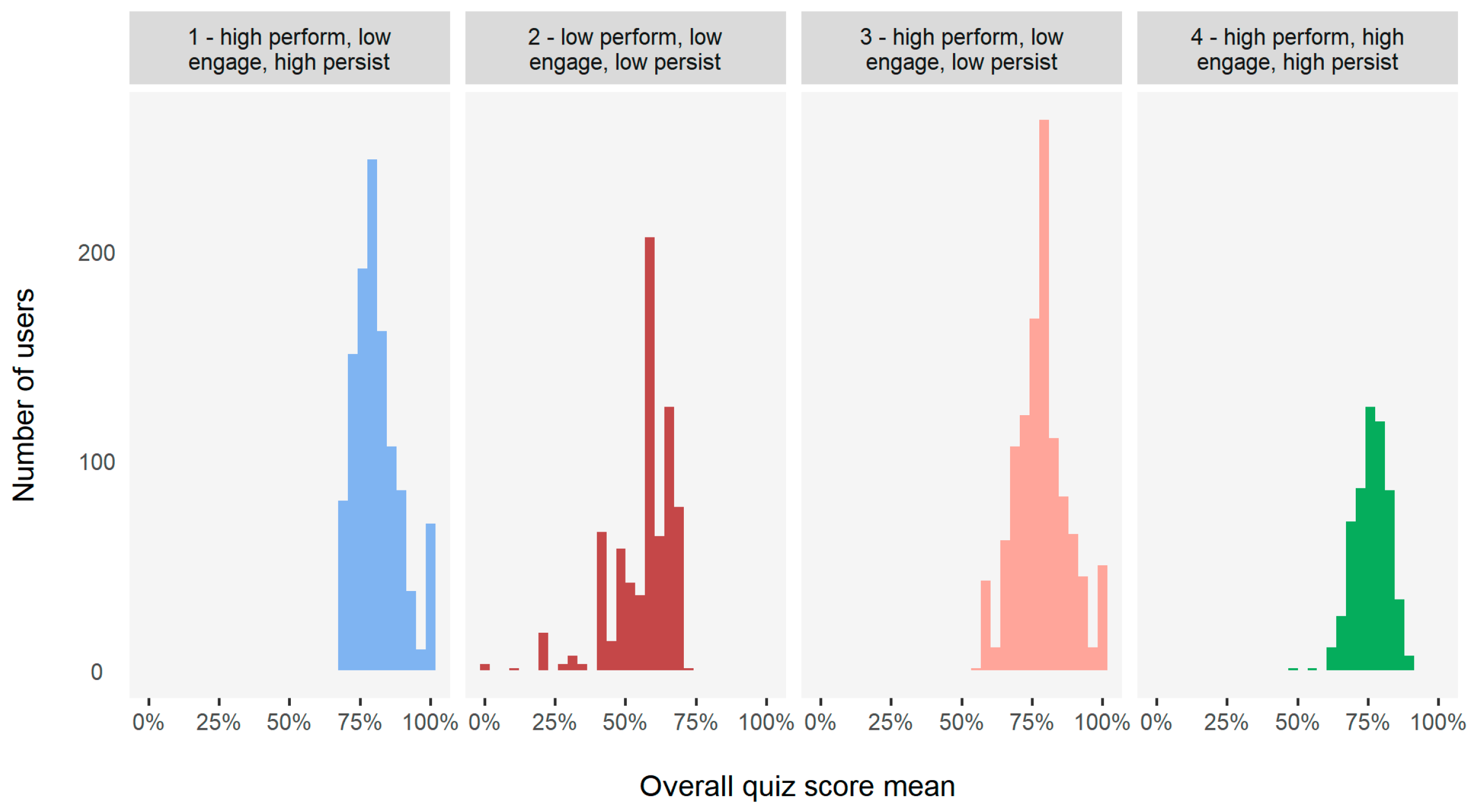

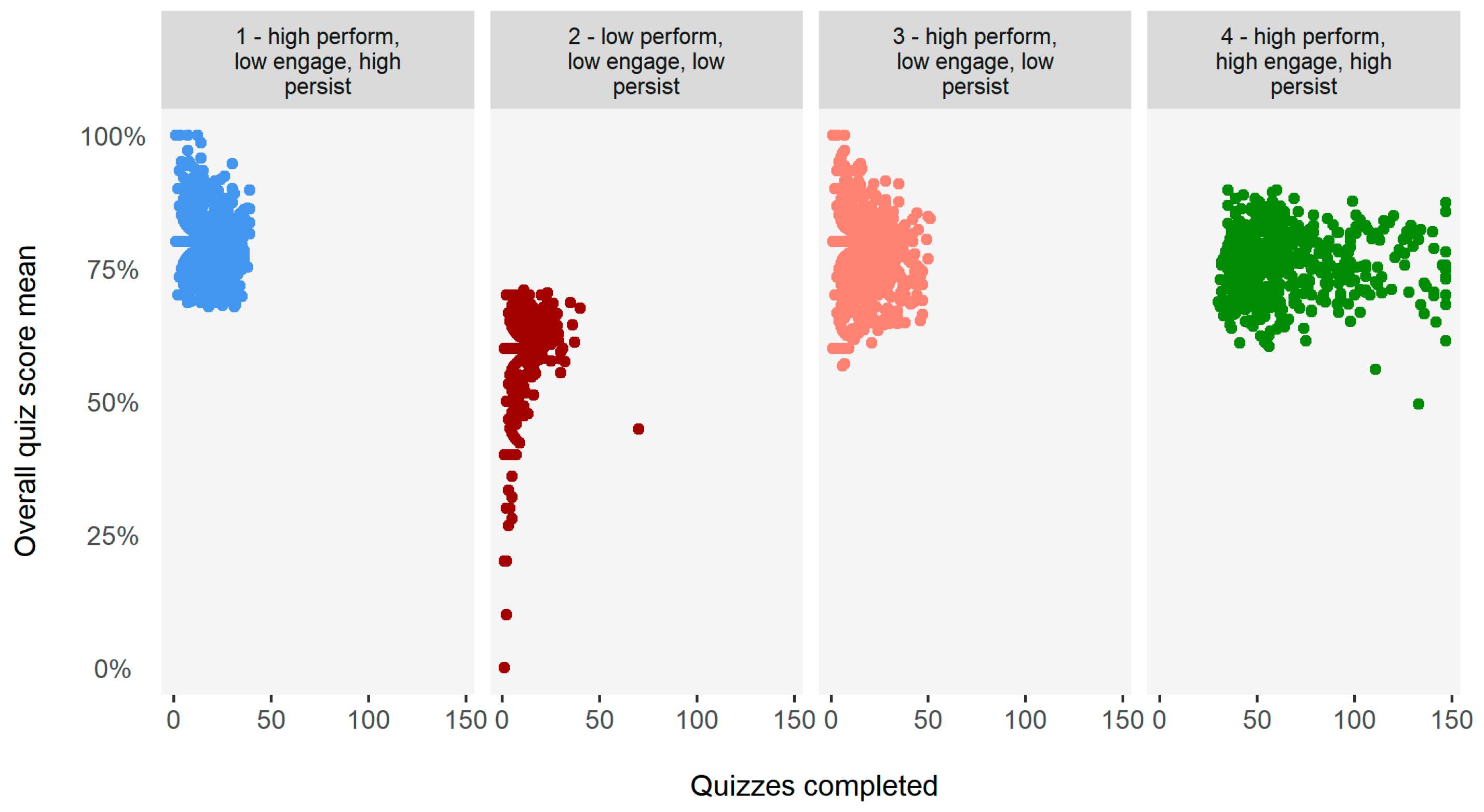

3.1.1. Pharmacist Cluster Analysis

- Cluster 1: High performance, low engagement, high persistence;

- Cluster 2: Low performance, low engagement, low persistence;

- Cluster 3: High performance, low engagement, low persistence;

- Cluster 4: High performance, high engagement, high persistence.

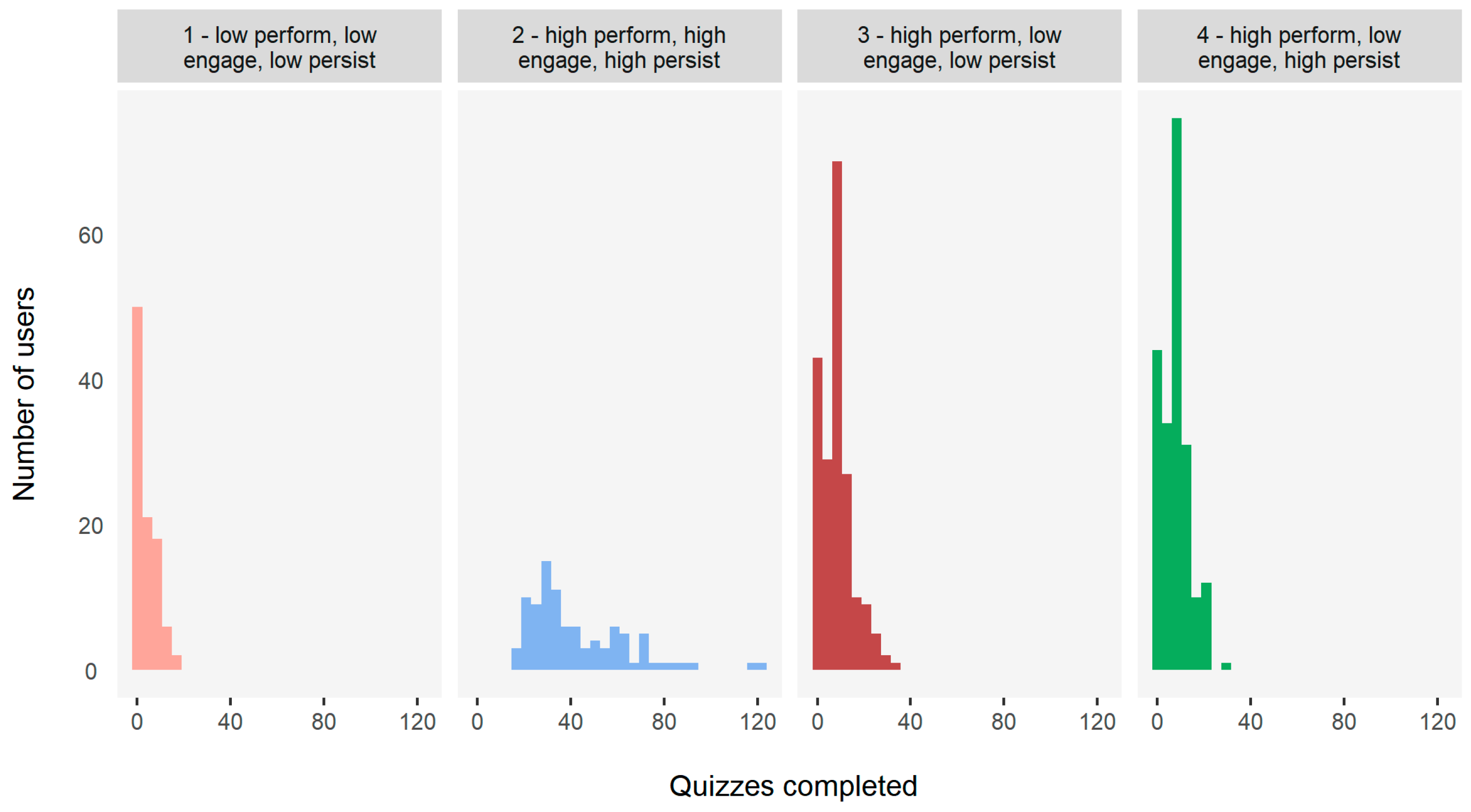

3.1.2. Technician Cluster Analysis

- Cluster 1: Low performance, low engagement, low persistence;

- Cluster 2: High performance, high engagement, high persistence;

- Cluster 3: High performance, low engagement, low persistence;

- Cluster 4: High performance, low engagement, high persistence.

3.2. Regression Analysis

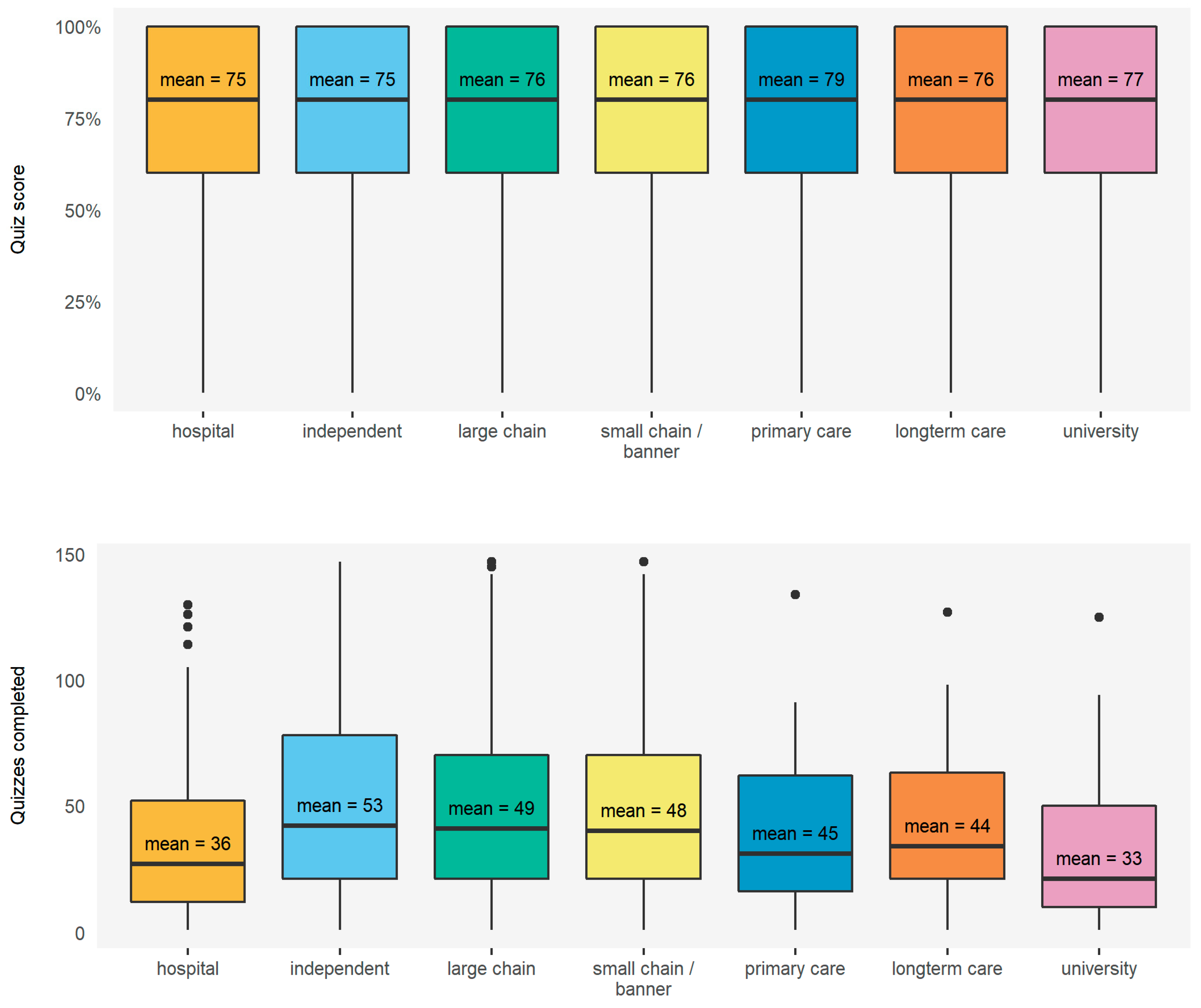

3.2.1. Relationships between Demographics, Performance, and Engagement

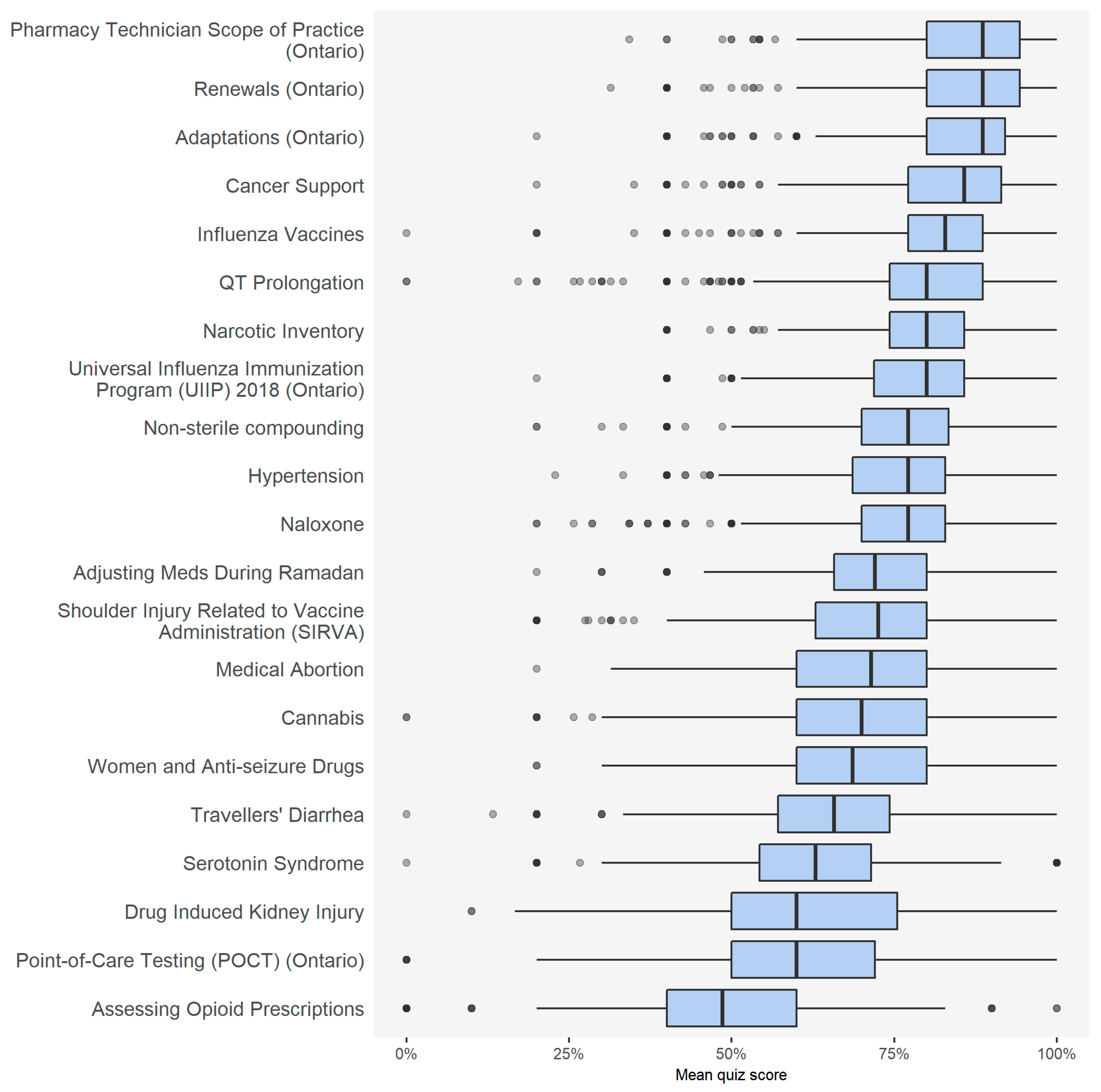

3.2.2. Relationship between Topic Type, Performance, and Engagement

3.2.3. Relationship between Self-Reported Past Behavior and Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Users Attempting Module | Users Completing Module | Module Completion Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptations (Ontario) | 1318 | 877 | 67% |

| Adjusting Meds During Ramadan | 523 | 270 | 52% |

| Assessing Opioid Prescriptions | 807 | 343 | 43% |

| Cancer Support | 569 | 323 | 57% |

| Cannabis | 1574 | 738 | 47% |

| Drug-Induced Kidney Injury | 532 | 281 | 53% |

| Hypertension | 748 | 416 | 56% |

| Influenza Vaccines | 1166 | 825 | 71% |

| Medical Abortion | 392 | 257 | 66% |

| Naloxone | 1087 | 710 | 65% |

| Narcotic Inventory | 634 | 336 | 53% |

| Non-sterile compounding | 1019 | 532 | 52% |

| Pharmacy Technician Scope of Practice (Ontario) | 958 | 663 | 69% |

| Point-of-Care Testing (POCT) (Ontario) | 986 | 441 | 45% |

| QT Prolongation | 1104 | 593 | 54% |

| Renewals (Ontario) | 1118 | 760 | 68% |

| Serotonin Syndrome | 1134 | 565 | 50% |

| Shoulder Injury Related to Vaccine Administration (SIRVA) | 1309 | 823 | 63% |

| Travellers’ Diarrhea | 676 | 388 | 57% |

| Universal Influenza Immunization Program (UIIP) 2018 (Ontario) | 1028 | 730 | 71% |

| Women and Anti-seizure Drugs | 202 | 99 | 49% |

References

- Houle, S.K.D.; Carter, C.A.; Tsuyuki, R.T.; Grindrod, K.A. Remunerated patient care services and injections by pharmacists: An international update. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2019, 59, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawoud, D.; Griffiths, P.; Maben, J.; Goodyer, L.; Greene, R. Pharmacist supplementary prescribing: A step toward more independence? Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2011, 7, 56–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tully, M.P.; Latif, S.; Cantrill, J.A.; Parker, D. Pharmacists’ changing views of their supplementary prescribing authority. Pharm. World Sci. 2007, 29, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, F.; Parsons, C.; Hughes, C.M. ‘It’s showed me the skills that he has’: pharmacists’ and mentors’ views on pharmacist supplementary prescribing. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2010, 18, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makowsky, M.J.; Guirguis, L.M.; Hughes, C.A.; Sadowski, C.A.; Yuksel, N. Factors influencing pharmacists’ adoption of prescribing: Qualitative application of the diffusion of innovations theory. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolhatkar, A.; Cheng, L.; Chan, F.K.; Harrison, M.; Law, M.R. The impact of medication reviews by community pharmacists. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2016, 56, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M.R.; Cheng, L.; Kratzer, J.; Morgan, S.G.; Marra, C.; Lynd, L.D.; Majumdar, S.R. Impact of allowing pharmacists to independently renew prescriptions: A population-based study. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2015, 55, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolovich, L.; Consiglio, G.; MacKeigan, L.; Abrahamyan, L.; Pechlivanoglou, P.; Rac, V.E.; Pojskic, N.; Bojarski, E.A.; Su, J.; Krahn, M.; et al. Uptake of the MedsCheck annual medication review service in Ontario community pharmacies between 2007 and 2013. Can. Pharm. J. (Ott) 2016, 149, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokanovic, N.; Tan, E.C.; van den Bosch, D.; Kirkpatrick, C.M.; Dooley, M.J.; Bell, J.S. Clinical medication review in Australia: A systematic review. Res. Soc. Admin. Phar. 2016, 12, 384–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, Z.; Gregory, P. Learning Needs of Pharmacists for an Evolving Scope of Practice. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor Car, L.; Soong, A.; Kyaw, B.M.; Chua, K.L.; Low-Beer, N.; Majeed, A. Health professions digital education on clinical practice guidelines: A systematic review by Digital Health Education collaboration. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cook, D.A.; Levinson, A.J.; Garside, S.; Dupras, D.M.; Erwin, P.J.; Montori, V.M. Internet-based learning in the health professions: A meta-analysis. JAMA 2008, 300, 1181–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gagne, J.C.; Park, H.K.; Hall, K.; Woodward, A.; Yamane, S.; Kim, S.S. Microlearning in Health Professions Education: Scoping Review. JMIR Med Educ 2019, 5, e13997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, K.; Gope, K. Challenges of implementing e-learning for higher education in least developed countries: A case study on Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the 2009 International Conference on Information and Multimedia Technology. South Korea December 16-18, 2009; IEEE Computer Society: Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 155–159. ISBN 978-1-4244-5383-2. [Google Scholar]

- Kowlowitz, V.; Palmer, M.H.; Davenport, C.S. Development and dissemination of web-based clinical simulations for continuing geriatric nursing education. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2009, 35, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiuchi, S.; Yaju, Y.; Koyo, M.; Sakyo, Y.; Nakayama, K. Evaluation of a web-based graduate continuing nursing education program in Japan: A randomized controlled trial. Nurs. Educ. Today 2009, 29, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawn, S.; Zhi, X.; Morello, A. An integrative review of e-learning in the delivery of self-management support training for health professionals. BMC Med. Ed. 2017, 17, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grindrod, K.A.; Killeen, R. Pharmacy5in5: Building a computer-based education platform for pharmacists. Under review.

- Lawson, R.G.; Jurs, P.C. New index for clustering tendency and its application to chemical problems. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1990, 30, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, L.; Rousseeuw, P.J. Clustering by means of Medoids. In Statistical Data Analysis Based on the L 1–Norm and Related Methods; Dodge, Y., Ed.; North Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1987; pp. 405–416. ISBN 0444702733. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, A.; Richards, G.; de la Iglesia, B.; Rayward-Smith, V. Clustering rules: A comparison of partitioning and hierarchical clustering algorithms. J. Math. Model. Algor. 1992, 5, 475–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calinski, T.; Harabasz, J. A dendrite method for cluster analysis. Comm. Statist. Theory Methods 1974, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, C. Cluster-wise assessment of cluster stability. Comp. Stat. Data An. 2007, 52, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, C. Dissolution point and isolation robustness: Robustness criteria for general cluster analysis methods. J. Multivar. Anal. 2008, 99, 1154–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Pharmacists. 2016. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/pharm-2016-data-tables-en-web.xlsx (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Deci, E.L.; Koestner, R.; Ryan, R.M. Extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation in education: Reconsidered once again. Rev. Ed. Res. 2001, 71, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemp. Ed. Psych. 2000, 25, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willis, S.C.; Seston, E.M.; Family, H.; White, S.; Cutts, C. Extending the scope of community pharmacists’ practice to patients requiring urgent care—An evaluation of a training programme using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Health Soc. Care Community 2019, 27, 999–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal, M.; Austin, Z.; Tsuyuki, R.T. Are pharmacists the ultimate barrier to pharmacy practice change? Can. Pharm. J. (Ott) 2010, 143, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number (%) | Performance (Mean Score) | Engagement (Mean Quizzes Completed) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Identity | |||

| Female | 3739 (71%) | 75 | 18 |

| Male | 1538 (29%) | 74 | 19 |

| Non-binary | 13 (0.3%) | 75 | 25 |

| Age | |||

| <25 years | 551 (10%) | 74 | 16 |

| 25–44 years | 3082 (58%) | 75 | 17 |

| 45–64 years | 1538 (29%) | 74 | 22 |

| >64 years | 119 (2%) | 71 | 31 |

| Years in Practice | |||

| <10 years | 3029 (57%) | 75 | 18 |

| 10–19 years | 971 (18%) | 75 | 16 |

| >20 years | 1290 (24%) | 74 | 23 |

| User Type | |||

| Pharmacist | 3579 (68%) | 75 | 20 |

| Technician | 595 (11%) | 75 | 13 |

| Pharmacy Student | 711 (13%) | 75 | 20 |

| Technician Student | 405 (8%) | 74 | 16 |

| Practice Type | |||

| Community (independent) | 1326 (25%) | 73 | 20 |

| Community (large chain) | 1883 (36%) | 75 | 21 |

| Community (small chain) | 768 (15%) | 75 | 20 |

| Primary Care | 92 (2%) | 76 | 15 |

| Long Term Care | 130 (2%) | 76 | 18 |

| Hospital | 935 (18%) | 75 | 12 |

| University/Academia | 156 (3%) | 74 | 12 |

| Entry-to-Practice Training | |||

| Canada | 4025 (76%) | 76 | 18 |

| International | 941 (18%) | 72 | 20 |

| Both | 324 (6%) | 70 | 21 |

| Daily Prescription Count | |||

| Median | 120 | ||

| Mean | 156 |

| Cluster 1 (N = 1141) | Cluster 2 (N = 727) | Cluster 3 (N = 1142) | Cluster 4 (N = 569) | Overall (N = 3579) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall quiz score | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 81 (8) | 57 (11) | 79 (9) | 76 (6) | 75 (13) |

| Median | 80 | 60 | 80 | 76 | 76 |

| Range | 68–100 | 0–71 | 57–100 | 49–90 | 0–100 |

| Number quizzes completed on the platform | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 13 (10) | 7 (7) | 11 (11) | 65 (28) | 20 (24) |

| Median | 10 | 4 | 7 | 56 | 9 |

| Range | 1–39 | 1–70 | 1–51 | 30–147 | 1–147 |

| Number of modules attempted | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 10 (4) | 4 (4) |

| Median | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 2 |

| Range | 1–10 | 1–13 | 1–11 | 5–21 | 1–21 |

| Proportion of quizzes completed per module attempted | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 87 (15) | 72 (27) | 31 (15) | 71 (27) | 64 (31) |

| Median | 94 | 77 | 29 | 79 | 67 |

| Range | 29–100 | 14–100 | 14–69 | 14–100 | 14–100 |

| Persistence Score (combination of proportion of quizzes and modules completed) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 50 (7) | 41 (13) | 21 (8) | 60 (14) | 41 (18) |

| Median | 52 | 44 | 20 | 62 | 43 |

| Range | 35–71 | 10–81 | 10–37 | 26–95 | 10–95 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 333 (29%) | 263 (36%) | 397 (35%) | 166 (29%) | 1159 (32%) |

| Female | 808 (71%) | 463 (64%) | 741 (65%) | 400 (70%) | 2412 (67%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 4 (0%) | 3 (1%) | 8 (0%) |

| Year of birth | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 1978 (11) | 1976 (12) | 1978 (11) | 1973 (13) | 1977 (12) |

| Median | 1980 | 1978 | 1980 | 1972 | 1979 |

| Range | 1918–2001 | 1918–2001 | 1918–2001 | 1918–2001 | 1918–2001 |

| Highest level of education | |||||

| Bachelor in Pharmacy | 837 (74%) | 532 (74%) | 848 (75%) | 448 (79%) | 2665 (75%) |

| Entry Level PharmD | 143 (13%) | 71 (10%) | 140 (12%) | 53 (9%) | 407 (11%) |

| Graduate PharmD | 63 (6%) | 39 (5%) | 59 (5%) | 23 (4%) | 184 (5%) |

| Masters | 81 (7%) | 61 (8%) | 78 (7%) | 40 (7%) | 260 (7%) |

| PhD | 13 (1%) | 18 (2%) | 12 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 48 (1%) |

| Did not answer | 4 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 15 |

| Location of entry-to-practice training | |||||

| Canada | 823 (72%) | 422 (58%) | 813 (71%) | 376 (66%) | 2434 (68%) |

| International/Both | 318 (28%) | 305 (42%) | 329 (29%) | 193 (34%) | 1145 (32%) |

| Year started practicing | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 2005 (11) | 2004 (12) | 2005 (12) | 2001 (14) | 2004 (12) |

| Median | 2009 | 2008 | 2009 | 2004 | 2008 |

| Range | 1969–2019 | 1971–2019 | 1969–2019 | 1969–2019 | 1969–2019 |

| Type of pharmacy practice | |||||

| Hospital | 181 (16%) | 134 (18%) | 201 (18%) | 48 (8%) | 564 (16%) |

| Community | 888 (78%) | 557 (77%) | 880 (77%) | 503 (88%) | 2828 (79%) |

| Primary care | 36 (3%) | 12 (2%) | 22 (2%) | 8 (1%) | 78 (2%) |

| Long term care | 31 (3%) | 16 (2%) | 33 (3%) | 10 (2%) | 90 (3%) |

| University | 5 (0%) | 8 (1%) | 6 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 19 (1%) |

| Average number of prescriptions per shift | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 156 (150) | 158 (234) | 152 (136) | 143 (107) | 153 (161) |

| Median | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Range | 0–1700 | 0–3500 | 0–1500 | 0–1000 | 0–3500 |

| Not applicable | 721 | 438 | 727 | 315 | 2201 |

| Cluster 1 (N = 97) | Cluster 2 (N = 94) | Cluster 3 (N = 196) | Cluster 4 (N = 208) | Overall (N = 595) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall quiz scores | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 51 (11) | 71 (8) | 80 (10) | 83 (8) | 75 (15) |

| Median | 51 | 72 | 80 | 82 | 77 |

| Range | 20–66 | 48–88 | 60–100 | 64–100 | 20–100 |

| Overall quizzes completed | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 4 (4) | 43 (22) | 8 (7) | 8 (6) | 13 (16) |

| Median | 2 | 35 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Range | 1–17 | 16–123 | 1–33 | 1–28 | 1–123 |

| Persistence | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 40 (15) | 51 (15) | 19 (8) | 48 (8) | 37 (17) |

| Median | 44 | 50 | 17 | 52 | 38 |

| Range | 10–57 | 21–90 | 10–35 | 31–64 | 10–90 |

| Proportion of quizzes completed | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 72 (29) | 67 (27) | 29 (14) | 87 (16) | 62 (32) |

| Median | 79 | 64 | 29 | 98 | 64 |

| Range | 14–100 | 14–100 | 14–64 | 43–100 | 14–100 |

| Number of modules attempted | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 1 (1) | 7 (3) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Median | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Range | 1–4 | 3–17 | 1–7 | 1–7 | 1–17 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 11 (11%) | 10 (11%) | 20 (10%) | 11 (5%) | 52 (9%) |

| Female | 86 (89%) | 84 (89%) | 176 (90%) | 196 (94%) | 542 (91%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 1 (0%) |

| Year of birth | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 1980 (10) | 1978 (12) | 1978 (12) | 1979 (10) | 1978 (11) |

| Median | 1980 | 1977 | 1979 | 1980 | 1979 |

| Range | 1958–1997 | 1956–1999 | 1918–2001 | 1953–1997 | 1918–2001 |

| Location of entry-to-practice training | |||||

| Canada | 91 (94%) | 93 (99%) | 192 (98%) | 204 (98%) | 580 (97%) |

| International/Both | 6 (6%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 4 (2%) | 15 (3%) |

| Year started practicing | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 2007 (9) | 2006 (12) | 2005 (11) | 2007 (10) | 2006 (10) |

| Median | 2009 | 2012 | 2008 | 2010 | 2010 |

| Range | 1977–2019 | 1979–2019 | 1976–2019 | 1979–2018 | 1976–2019 |

| Type of pharmacy | |||||

| Hospital | 52 (54%) | 30 (32%) | 95 (48%) | 106 (51%) | 283 (48%) |

| Community | 42 (43%) | 55 (59%) | 90 (46%) | 96 (46%) | 283 (48%) |

| Primary care | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Long term care | 3 (3%) | 9 (10%) | 9 (5%) | 6 (3%) | 27 (5%) |

| University | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0%) |

| Average number of prescriptions per shift | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 330 (617) | 187 (139) | 234 (433) | 260 (305) | 252 (394) |

| Median | 200 | 175 | 150 | 200 | 200 |

| Range | 0–3000 | 0–500 | 0–3000 | 0–2200 | 0–3000 |

| Not applicable | 67 | 64 | 149 | 144 | 424 |

| Performance (Overall Quiz Score) | Engagement (Number of Quizzes Completed) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Estimate (Std. error) | Estimate (Std. error) |

| User type (reference pharmacist) | ||

| Pharmacy student | −0.039 * (0.011) | 0.262* (0.008) |

| Pharmacy technician | −0.152 * (0.013) | −0.268 * (0.010) |

| Pharmacy technician student | −0.363 * (0.013) | −0.032 * (0.010) |

| Gender (reference male) | ||

| Female | 0.046 * (0.007) | 0.026 (0.006) |

| Other | 0.028 (0.059) | 0.297 * (0.044) |

| Location of training (reference Canada) | ||

| Outside Canada | −0.126 * (0.009) | 0.007 (0.007) |

| Both | −0.231 * (0.013) | −0.108 * (0.010) |

| Practice type (reference hospital) | ||

| Independent | 0.014 (0.012) | 0.331 * (0.009) |

| Large chain | 0.070 * (0.011) | 0.257 * (0.009) |

| Small chain | 0.058 * (0.013) | 0.232 * (0.010) |

| Primary care | 0.166 * (0.031) | 0.178 * (0.022) |

| Long term care | 0.074 * (0.024) | 0.237 * (0.018) |

| University | 0.101 * (0.027) | −0.136 * (0.020) |

| Year started practicing Year of birth | 0.002 * (0.000) 0.001 * (0.000) | −0.001 * (0.000) −0.032 * (0.000) |

| Module | Mean Quiz Score | Mean Module Completion Rate | Quizzes Completed Estimate (std. Error) | Quiz Score Estimate (std. Error) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptations (Ontario) | 87% | 67% | 0.126 * (0.01) | 0.194 * (0.013) |

| Adjusting Meds During Ramadan | 72% | 52% | −0.005 (0.012) | −0.01 (0.017) |

| Assessing Opioid Prescriptions | 52% | 43% | 0.083 * (0.008) | 0.237 * (0.014) |

| Cancer Support | 85% | 57% | 0.138 * (0.013) | 0.307 * (0.02) |

| Cannabis | 68% | 47% | −0.068 * (0.006) | −0.119 * (0.008) |

| Drug-Induced Kidney Injury | 64% | 53% | 0.126 * (0.011) | 0.211 * (0.014) |

| Hypertension | 76% | 56% | 0.022 * (0.01) | 0.042 * (0.014) |

| Influenza Vaccines | 83% | 71% | 0.083 * (0.01) | 0.097 * (0.012) |

| Medical Abortion | 72% | 66% | 0.052 * (0.015) | 0.07 * (0.018) |

| Naloxone | 76% | 65% | 0.029 * (0.009) | 0.045 * (0.011) |

| Narcotic Inventory | 78% | 53% | 0.012 (0.011) | 0.026 (0.017) |

| Non-sterile compounding | 76% | 52% | −0.018 * (0.009) | −0.036 * (0.013) |

| Pharmacy Technician Scope of Practice (Ontario) | 87% | 69% | 0.052 * (0.012) | 0.081 * (0.016) |

| Point-of-Care Testing (Ontario) | 64% | 45% | 0.089 * (0.007) | 0.262 * (0.013) |

| QT Prolongation | 81% | 54% | 0.055 * (0.009) | 0.129 * (0.014) |

| Renewals (Ontario) | 87% | 68% | 0.149 * (0.01) | 0.214 * (0.014) |

| Serotonin Syndrome | 64% | 50% | 0.063 * (0.007) | 0.134 * (0.01) |

| Shoulder Injury Related to Vaccine Administration (SIRVA) | 72% | 63% | 0.078 * (0.008) | 0.124 * (0.01) |

| Travellers’ Diarrhea | 65% | 57% | 0.034 * (0.01) | 0.065 * (0.014) |

| Universal Influenza Immunization Program (UIIP) 2018 (Ontario) | 80% | 71% | 0.086 * (0.01) | 0.092 * (0.011) |

| Women and Anti-seizure Drugs | 70% | 49% | 0.051 * (0.018) | 0.121 * (0.028) |

| Module | Users Reporting They Performed the Target Behavior | Mean Score for Users Who Did Not Perform the Behavior | Mean Score for Users Who Did Perform the Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptations (Ontario) | 43% | 90% | 88% |

| Adjusting Meds During Ramadan | 20% | 70% | 65% |

| Assessing Opioid Prescriptions | 24% | 55% | 58% |

| Cancer Support | 31% | 87% | 88% |

| Cannabis | 21% | 65% | 64% |

| Drug-induced Kidney Injury | 28% | 62% | 68% |

| Hypertension | 34% | 75% | 79% |

| Influenza Vaccines | 38% | 83% | 88% |

| Medical Abortion | 20% | 74% | 73% |

| Naloxone | 30% | 76% | 72% |

| Narcotic Inventory | 40% | 75% | 82% |

| Non-sterile compounding | 41% | 75% | 75% |

| Pharmacy Technician Scope of Practice (Ontario) | 35% | 86% | 88% |

| Point-of-Care Testing (POCT) (Ontario) | 14% | 67% | 65% |

| QT Prolongation | 38% | 81% | 81% |

| Renewals (Ontario) | 44% | 88% | 88% |

| Serotonin Syndrome | 35% | 61% | 68% |

| Shoulder Injury Related to Vaccine Administration (SIRVA) | 42% | 74% | 68% |

| Travellers’ Diarrhea | 27% | 65% | 62% |

| Universal Influenza Immunization Program (UIIP) 2018 (Ontario) | 38% | 76% | 85% |

| Women and Anti-seizure Drugs | 25% | 67% | 71% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grindrod, K.; Morris, K.; Killeen, R. Assessing Performance and Engagement on a Computer-Based Education Platform for Pharmacy Practice. Pharmacy 2020, 8, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8010026

Grindrod K, Morris K, Killeen R. Assessing Performance and Engagement on a Computer-Based Education Platform for Pharmacy Practice. Pharmacy. 2020; 8(1):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8010026

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrindrod, Kelly, Katherine Morris, and Rosemary Killeen. 2020. "Assessing Performance and Engagement on a Computer-Based Education Platform for Pharmacy Practice" Pharmacy 8, no. 1: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8010026

APA StyleGrindrod, K., Morris, K., & Killeen, R. (2020). Assessing Performance and Engagement on a Computer-Based Education Platform for Pharmacy Practice. Pharmacy, 8(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8010026