Abstract

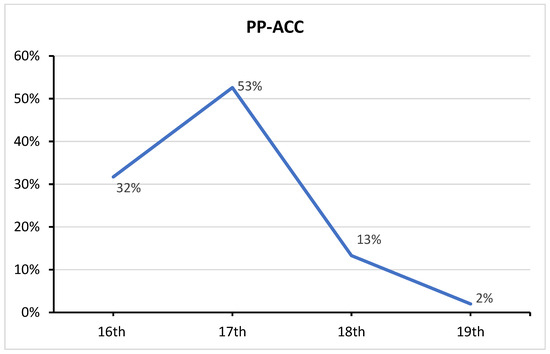

One of the several differences between Modern European Portuguese (EP) and Modern Brazilian Portuguese (BP) is the prepositional expression of complements licensed by the preposition a. While in EP the preposition a occurs in several contexts, this element has been substituted by other strategies in BP, as is extensively discussed in the literature. The aim of this paper is to investigate the historical behavior of a-marked prepositional accusatives (PP-ACC) in Portuguese. In order to do so, a search was conducted for PP-ACCs in the Historical Portuguese Corpus Tycho Brahe. The results showed an increase of PP-ACCs in the 17th century, followed by a decrease in the 18th century. Thereafter, unmarked accusatives (NP-ACC) were analyzed in the corpus, which resulted in 7756 sentences, contrasting with 624 PP-ACCs in the same contexts. This result shows that the a-marked accusative is far less common than bare accusatives in Historical Portuguese. Psych verbs, however, behaved differently, showing a constant increase in PP-ACCs. In EP, the preposition a still introduces Experiencer arguments in structures with some psych verbs (O vinho agradou ao João—lit. ‘The wine pleased ‘to’ John’). In BP, the preposition a has disappeared in psych predicates (O vinho agradou Ø o João—‘The wine pleased John’). In both Modern EP and BP, most PP-ACCs have become typical unmarked direct objects. In the context of psych verbs, however, structural accusative assignment has shifted to structural dative Case in Modern EP, so as to ascertain the interpretation of the Experiencer in the internal argument via the preposition a. While in Modern BP, the argument is not overtly marked since it receives inherent accusative case in the derivation.

1. Introduction

The argument structures found in Modern European Portuguese (EP) and Modern Brazilian Portuguese (BP) have undergone several changes historically (cf. Galves 2001, 2007, 2020, a.o.), especially regarding the prepositional expression of complements licensed by the preposition a. In EP, the preposition a is used to introduce indirect dative arguments, as in (1a) and (2a) below. In BP, synchronic data shows that the preposition a found in EP has been replaced by other prepositions with a more transparent thematic role, such as para and de in several contexts ((1b) and (2b)) (Torres Morais and Salles 2010; Torres Morais and Berlinck 2018). Additionally, some predicates with psych verbs encode their Experiencer argument with the preposition a in EP, but the same complement is unmarked in BP (cf. 3):

| (1) | a. | A | Maria | enviou | uma | carta | ao João | /enviou-lhe | uma | carta. |

| The | Maria | sent | a | letter | Pa(to) the João | /sent-CL.DAT.3SG | a | letter. | ||

| b. | A | Maria | enviou | uma | carta | ao | /para o João | /ele. | ||

| The | Maria | sent | a | letter | Pa(to) | /Ppara(to) the João | /him. | |||

| (2) | a. | A | Maria | roubou | o | relógio | ao João | /roubou-lhe | o relógio. | |

| The | Maria | stole | the | watch | Pa(to).the João | /stole-CL.DAT.3SG | the watch. | |||

| b. | A | Maria | roubou | o | relógio | do João | /dele. | |||

| The | Maria | stole | the | watch | Pde(of).the João | /his. | ||||

| (3) | a. | O | vinho | agradou | aos convidados | /agradou-lhes. | ||||

| The | wine | pleased | Pa(to).the guests | /pleased- CL.DAT.3PL | ||||||

| b. | O | vinho | agradou | (*a) os convidados | /os agradou | /agradou eles. | ||||

| The | wine | pleased | Pa(to).the guests | /CL.ACC.M.3PLpleased | /pleased they.ACC1 | |||||

The comparison between both varieties is based on the fact that they share a common historical background, as the language that arrived in Brazil in the 16th century was Classical Portuguese (CP) (Galves 2007). Over the years, CP has become EP and BP, as these varieties have parted ways in several syntactic and morphological aspects, such as the different strategies used to encode their arguments (cf. Galves 2001). Therefore, the texts produced by Portuguese authors from the 16th century on are essential to the study of both Portuguese varieties.2

Specifically, the main goal of this paper is to investigate the contexts in which accusative arguments were a-marked historically, as example (4) from the 17th century illustrates. Synchronic data from both BP and EP show that accusative direct objects selected by dicendi verbs such as chamar, ‘call’, are never marked.3

| (4) | (…) | chama | a | Pedro | e | André, | e | aos filhos | do | Zebedeu. |

| call | Pa(to) | Pedro | and | André, | and | Pa(to).the sons | of.the | Zebedeu | ||

| ‘(…) | call Pedro and André, and Zebedeu’s sons.’ | |||||||||

| 17th century (V_004,202.1819)4 | ||||||||||

The literature on Portuguese variation and change highlights that the great historical modifications in the structure of BP began to be noticed in the 18th century; some became stable in the 19th and 20th centuries, while others are still in the process of variation in current BP (Kato et al. 2009; Torres Morais and Berlinck 2018; Galves 2020). Furthermore, Galves (2020) attests that even though there are several studies with an empirical basis about the 19th and 20th centuries, there are fewer works on the 17th and 18th centuries. For that reason, an investigation on Historical Portuguese from the 16th to the 19th century is very relevant to understanding the contexts and possible reasons for the changes attested in EP and BP. Accordingly, to achieve the main aim of this paper, 19 texts from the Historical Portuguese corpus, organized by the Tycho Brahe Project at Unicamp, were analyzed.5 These texts cover precisely the period between the 16th and 19th centuries. The data collected provided clear evidence, especially, for psych verbs, which showed a distinct behavior in licensing arguments with the preposition a throughout the centuries, as we will discuss in more detail in the results section.

As shown in examples (1) to (3), the preposition a introduces indirect dative arguments in Modern EP. This element has been analyzed as a dummy marker that licenses the dative argument. According to Torres Morais (2007), there are two pieces of evidence for the a-DP dative status in EP: firstly, the possibility that the argument will be displaced to the topic position, maintaining the preposition (Ao João, a Maria enviou uma carta, ‘To João, Maria sent a letter’). Secondly, the fact that the a-DP in EP always alternates with dative clitics (lhe/lhes), as attested to in the examples above.

In Modern BP, on the other hand, the dative clitic lhe(s) has been replaced by other strategies, such as 3rd person pronouns preceded by contentful prepositions, such as de/para ele(s)/ela(s), ‘of/to him/her/them’, as exemplified above (Calindro 2015, 2016; Torres Morais and Berlinck 2018; Bazenga and Rodrigues 2019).6 This is evidence that case assignment in BP is different from EP, since the morphological case in the form of the clitic lhe has been lost and the dummy preposition a has been replaced by contentful prepositions that assign an oblique case to the argument they introduce or has disappeared, as in the context of psych verbs (cf. 3b) (Calindro 2015, 2020).

As for psych verbs specifically, their structure is transitive (cf. 3), not ditransitive as in (1) and (2). The direct object in (3) is the Experiencer of the event, overtly marked in EP (3a) but not in BP (3b). Most of the literature on variation and change in Portuguese has addressed ditransitive verbs with Goal indirect objects introduced by the preposition a in EP and para in BP. Transitive contexts with prepositional accusatives seem to be less explored (Ramos 1992; Gibrail 2003; Calindro 2017). Even less discussed are syntactic issues related to the licensing of the preposition a in psych predicates with Experiencer arguments (cf. Figueiredo Silva 2007; Carneiro and Naves 2010). This fact, coupled with the corpus analysis, led us to a second goal, which is to analyze the reasons why EP and BP mark Experiencers in a distinct way. We are assuming that, with psych verbs, since the Experiencer argument is generated as an internal argument, a conflict is displayed between case and theta assignment. To solve this divergence, the argument is a-marked, in some contexts, in predicates with psych verbs in EP. In BP, on the other hand, the Experiencer argument enters the derivation with inherent accusative case, and the Theme, such as vinho, ‘wine’, in (3b) is raised to receive the nominative case (in Chomsky’s (1981) terms).7

Finally, in the literature, a-marked accusative arguments are sometimes addressed as PP-ACC and/or are treated as differential object marking (DOM), so, in the next section, we present an overall view of how these phenomena are related and addressed in the studies about Portuguese, followed by a discussion on psych verbs. In Section 3, the research methods are exposed. Section 4 shares the data results and a discussion on the categorical status of a-marked objects. Based on these considerations, our proposal is put forward in Section 5, followed by the final remarks in the last section.

2. PP-ACC and DOM in Historical Portuguese

It seems not to be clear in the literature how and why accusative a-marking/DOM appeared in Romance. According to Bossong (1991), many languages employ what he calls DOM in order to syntactically encode subsets of direct objects. This phenomenon is present in several Romance languages, such as Spanish, Catalan, Romanian, and Italo Romance varieties (Andriani 2015). With the exception of Romanian, the DOM marker is homophonous to the dative used to introduce indirect objects, as the preposition a in Portuguese. Therefore, the data presented previously indicate the possibility of a-marked objects in Portuguese being instances of DOM. On the surface, DOM seems to share features with prototypical prepositions, hence this phenomenon may also be found in the literature about Romance as PP-ACC. According to Fábregas (2013), DOM only partially shares features of prototypical prepositions. Additionally, Gerards (2020) points out that the diachronic data on DOM poses a problem, as it has been attested that a-marking first appeared with [+human] personal pronouns—Isso agradou a ela, ‘lit’. This pleased ‘to’ her (Döhla 2014); that is, specifically, one of the few elements that display overt case marking in all Romance languages and which, for that reason would not need additional Case marking.

Overt marking seems to emerge when the argument is autonomous from the verb, i.e., with self-constituent objects. In fact, Bossong (1991) discusses that being dependent or independent of the verbs is a factor to be taken into account when analyzing instances of DOM. This leads us to the type of verb the argument is associated with. For example, in Spanish, there are two verbs that always select a marked argument: buscar (to look for) and querer (to want) (Bossong 1991, pp. 158–59).8

Actually, Bossong (1991, p. 160) claims that DOM is related to three domains: i. the domain of inherence − [+deictic] < [+proper] < {[+parent]] < [+human] < {[+person]] < [+animated] < [+discrete]; ii. the domain of reference − [+individuality] < [+/−referentiality]/[+/−definiteness]; and iii. the domain of constituence − [+/−independent existence]/[+/−pragmatic constituency]. The author argues that it is common to use a mixture of these dimensions when analyzing overtly marked arguments. For Spanish and Romanian, Bossong claims inherence is the dominant factor required for DOM to occur. In this paper, as further explained in the methods section, we analyzed the data via verb classes, so we will consider what the author calls constituence—the argument being dependent or not on the verb—the main factor for our analysis at this point of the research. López (2016) also claims that syntactic configuration is one of the aspects that trigger DOM in Romance, along with features of the verbs and features of the object.

Synchronic EP data shows overtly marked arguments in predicates with some psych verbs (cf. 3a). Hence, the main question that emerged from the examples presented in the introduction was when and how this marking appeared historically and whether structures with verbs other than psych verbs also present a-marked arguments. Therefore, as will be explained in more detail in the methodology and results sections, the first search in the corpus was for all the accusatives marked by the preposition a that had been labeled by the Tycho Brahe group as PP-ACCs. The results confirmed that psych verbs behaved differently from other verb groups. This was indeed a very relevant context to address in order to understand how a-marked arguments behave in Portuguese. Nevertheless, before addressing the types of verbs present in the corpus, another question required consideration—should we consider the a-marked arguments instances of PP-ACCs or DOM in Portuguese?

Given the DOM characteristics put forth by the aforementioned authors, PP-ACC seems to be part DOM, which can be seen as a wider phenomenon, as it is related to several factors. Gerards (2020, p. 1) observes that the Romance-specific term PP-ACC may be misleading and inferior, so the author suggests a “categorically agnostic label flagging DOM”. This seems to be a valid solution; however, it is not the aim of this paper to solve this issue. What concerns us at the moment is the historical change Portuguese has undergone, considering that our results showed a decrease in a-marked elements in general, which is in conformity with the synchronic Portuguese data, as the vast majority of direct objects are unmarked accusatives. Moreover, to address the specific differences regarding PP-ACC and DOM, it is important to analyze the features of the objects, as suggested by López (2016) and Bossong (1991), who consider the domains of inherence and reference when analyzing DOM arguments, as mentioned above. It is not in the scope of this paper, however, to analyze the specific features of the a-marked arguments, such as definiteness, referentiality, and animacy (to name a few features mentioned by Bossong (1991)). We intend to do so in future work.9

As shown in the introduction, argument marking changes depending on the verb class that the predicate belongs to. This first observation guided the research towards the analysis of all a-marked arguments, followed by the analysis of the different verb classes the marked object appeared with. Then, it led to the analysis of psych verb predicates specifically, since the pattern presented in this context differs from the other ones, as already explained. Therefore, alongside the disappearance of PP-ACCs in BP, one of the aims of this research was to understand the context in which the Experiencer argument ceased to be marked in all psych predicates in BP, as exemplified in (3b). In the following section, the properties of psych verbs will be addressed.

Returning to PP-ACC/DOM, historically, overtly marked arguments in Romance appeared with topicalized personal pronouns used anaphorically and emphatically (Döhla 2014, p. 272):

| Proto-Romance—11th century | |||||

| (5) | a | míbe | ṭu | no(n) | queréś. |

| Pa(to). | me | you | neg | love | |

| ‘(but) me you don’t love’ | |||||

| (adapted from Corriente 1997, p. 319 apud Döhla 2014, p. 272) | |||||

In Modern Spanish, where, differently from Portuguese, DOM is a core phenomenon, definite animate DPs, for instance, are always associated with DOM. Manzini and Franco (2016) claim that all definite arguments display DOM in Spanish, as these arguments are attached VP-internally via DOM. On the other hand, DOM with indefinite animate arguments depends on the verb it is associated with, as some verbs prefer DOM. The authors argue that some action, psych, and perception predicates, which have non-affected objects, seem to have more transparent v-V structures. These are exactly the classes with more a-marked cases in the corpus analyzed here, which will be discussed in the results section.

In Spanish, the development of the preposition a as an accusative marker used to be seen in the literature as a singular historical event that demanded a specific historical explanation. Bossong (1991) points out, however, that this manifestation is one of the most common ways case marking changes in natural languages. According to the author, if subject and object are no longer distinguishable in the system, morphological marking is then substituted by a new differential system, which may in turn “become non-differential again by the continuous extension of the sphere of positive object marking; at this point of the evolution, the life cycle of case marking may start anew” (Bossong 1991, p. 152), which seems to be the case of the data analyzed in this paper. Therefore, a-marking was a way to overtly case-mark atypical direct objects, but as Portuguese progressed, this marking was no longer necessary, because SVO order became even more common than VOS, for instance, as we will discuss further in this paper.

Specifically, when it is not possible to distinguish between subject and object by formal means, two things may happen. First, such as what happened from Latin to Romance, when morphological marking is eliminated, it may just disappear, as in French, which has replaced morphological marking with structural Case marking (Bossong 1991, p. 146). The same is true for Nominative and Accusative in Portuguese in general, as we see further in this paper. The second option is to resort to what Bossong calls a new grammemic marking, such as a-marking.

According to Döhla (2014), DOM in Modern EP and BP is considered to be a marginal phenomenon. The author claims that DOM occurred in Old Portuguese due to three main reasons: i. parallelism (6)—when one a-marked object is followed by another one; ii. left dislocation—to emphasize the topicalized patient argument (7); and VSO order (8):

| Old Portuguese | ||||||||||||

| (6) | (…) | tendes | em | vossa | ajuda | muy | certos | a | mym | e | ao | Conde d’Ourem. |

| (you) have | in | yours | help | very | sure | Pa(to) | me | and | Pa(to) | .the Count of Ourem | ||

| ‘you have me and the Count of Ourem to help you.’ | ||||||||||||

| (7) | aos | proues | e | mjnguados | sostinha. | ||||

| Pa(to). | the poor | and | neglected | support | |||||

| ‘(he/she) supported the poor and the negleted.’ | |||||||||

| (8) | amando | mais | as | maes | a | seos | filhos. | ||||

| loving | more | the | mothers | Pa(to) | their | children | |||||

| ‘the mothers loving more their children.’ | |||||||||||

| (Delille 1970, pp. 36, 39, 42 apud Döhla 2014, pp. 274–75) | |||||||||||

As Döhla, Ramos (1992), and Gibrail (2003) also verified, there was a higher occurrence of a-marked arguments with VSO in the Historical Portuguese data they analyzed.10 As mentioned before, there seems to be an overlap between what is understood as DOM and what is understood as PP-ACC. These authors, for example, apply the name PP-ACC to the same examples Döhla refers to as DOM.

The numbers presented by Ramos and Gibrail show an increase in PP-ACCs in the VSO context in the 18th century. The authors claim that object marking in VSO sentences aims to disambiguate the syntactic function of NPs. One hypothesis is that as Portuguese started to present a more fixed SVO order (Galves 2020), object marking ceased to be necessary.

As mentioned before, our intent in this section was to present previous works on a-marked arguments in Historical Portuguese. Since these works address a-marked direct objects both as PP-ACC and DOM, it was important to give an overall view of these phenomena. Given what was presented in this subsection, there is indeed an overlap between the concepts of PP-ACC and DOM, as both strategies are responsible for overtly case-marking direct objects and may be related to the syntactic configuration and features of the verbs (López 2016). So, as specific features of the a-marked NPs in the data analyzed will not be discussed in this paper, we will continue to address a-marking arguments as PP-ACC. We leave the discussion on DOM vs. PP-ACC for future work, otherwise there would be too many variables to be considered here.11

Psych Verbs

In this paper, one of the main focuses is on structures with psych verbs where the Experiencer argument is still marked in Modern EP but unmarked in Modern BP.

In predicates with psych verbs, the Experiencer argument must be a person, hence [+animate] and [+human], who experiences a mental state (Belletti and Rizzi 1988). It can be either the subject (9) or the object (10) of the event. Additionally, the Theme argument, which is the content or the object of the mental state, may also be the subject (11a) or the object (11b). Even though these verbs fall into the same category, Belletti and Rizzi (1988) separate them into the three types, exemplified in (9) to (11), due to their distinct theta grids.

| Italian | |||||

| (9) | Gianni | teme | questo. | ||

| Gianni | fears | this | |||

| (10) | Questo | preoccupa | Gianni. | ||

| This | worries | Gianni | |||

| (11) | a. | Questo | piace | a | Gianni. |

| This | pleases | Pa(to) | Gianni | ||

| b. | A | Gianni | piace | questo. | |

| Pa(to) | Gianni | pleases | this | ||

| (Belletti and Rizzi 1988, pp. 291–92) | |||||

In Portuguese, sentence (12) is equivalent to (9). The examples in (13) show that there are also two possible mappings of the structure of some psych predicates (Carneiro and Naves 2010); (13a) is equivalent to (10), but the Theme argument can also be the content of the subject mental state, as we can see in (13b). In addition, the category of the verb assustar, ‘frighten’, also has an agentive component in Portuguese, since the [+human] subject can act intentionally, as in Maria assustou João, ‘Maria frightened John’ (Naves 2005, p. 122).

| (12) | JoãoEXP | teme | a | aranhaTHEME. |

| João | fears | the | spider | |

| ‘John fears the spider.’ | ||||

| (13) | a. | A | aranhaAGENT | assusta | o | JoãoEXP. | ||

| The | spider | frightens | the | João | ||||

| ‘The spider frightens João.’ | ||||||||

| b. | O | JoãoEXP | se | assusta | com | a | aranhaTHEME. | |

| The | João | CL.3SG | frightened | with | the | spider | ||

| ‘João gets frightened with the spider.’ | ||||||||

Among the many issues related to psych verbs, recall that we are specifically interested in the category of psych verbs such as agradar, ‘please’ (cf. 3)12, for three distinct reasons: firstly, the argument structure of these verbs includes object marking by the preposition a in EP, but it does not in modern BP; secondly, the data from the corpus analyzed showed that this context displays a-marked arguments throughout the four centuries; finally, the constituent order in these predicates is different in EP and BP, as shown specifically in examples (15) and (18):

| (14) | O | filme | agradou | ao | João. | (EP) |

| The | movie | pleased | Pa(to) | João | ||

| (15) | Ao | João | agradou | o | filme. | (EP) |

| Pa(to) | João | pleased | the | movie | ||

| (16) | O | filme | agradou | -lhe. | (EP) | |

| The | movie | pleased | -CL.DAT.3SG | |||

| (17) | O | filme | agradou | o | João. | (BP) |

| The | movie | pleased | the | John | ||

| (18) | *O | João | agradou | o | filme. | (BP) |

| The | João | pleased | the | movie | ||

| (19) | O | filme | agradou | -o. | (BP) | |

| The | movie | pleased | -CL.ACC.3SG. | |||

| (20) | O | filme | agradou | ele. | (BP) | |

| The | movie | pleased | he.ACC13 |

Observe that the structures with agradar in EP, with a prepositional-marked Experiencer argument, are the same as with piacere in Italian (cf. 11). In BP, however, the Experience is unmarked in the structures with agradar, similarly to (10) in Italian. Moreover, if we substitute the DP Theme filme, ‘movie’, in (17) for a [+animate] DP, such as João agrada Maria, ‘João pleases Maria’, there is the possibility of an agentive interpretation, which is not possible in (17) with the Theme filme, ‘movie’, but possible in (13a) with assustar, ‘frighten’. Thus, agradar would be part of a fourth class that combines the characteristics of (13a) and (17), which does not exist in Italian. In addition, the argument in BP is pronominalized with accusative elements with the abstract accusative case (cf. 19 and 20), while EP shows a dative counterpart (16).

Having presented some considerations on PP-ACC, DOM, and psych verbs crosslinguistically, in the next section we present the methodology employed to deal with the historical data at hand.

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, the data collected from the Tycho Brahe Corpus is presented. The corpus consists of 88 texts written by Portuguese and Brazilian authors who were born between 1380 and 1978. Out of the 88 texts, 19 texts had already been syntactically annotated at the time of the data collection (today there are 27 texts annotated syntactically), which adds up to a total of 819,932 words (Galves et al. 2017).

The main purpose of analyzing Portuguese historical data was to examine the contexts in which a-marked direct objects (DOs) presented variation between the 16th and 19th centuries. At first, a search was carried out for all occurrences of prepositional accusatives (PP-ACC-marked DOs) in the corpus, in sentences such as (4) (renumbered as (21)), below:

| (21) | (…) | chama | a | Pedro | e | André, | e | aos | filhos | do | Zebedeu. |

| call | Pa(to) | Pedro | and | André, | and | Pa(to). | the sons | of.the | Zebedeu | ||

| ‘(…) | call Pedro and André, and Zebedeu’s sons.’ | ||||||||||

| 17th century (V_004,202.1819) | |||||||||||

The relevant information about the texts examined in this paper is in Table 1:

Table 1.

Analyzed Texts.

All authors mentioned above were Portuguese.14 The 19 annotated texts add up to 39,761 sentences distributed as follows: 8930 in the 16th century; 8948 in the 17th century; 10,967 in the 18th century; and 10,916 in the 19th century.

In addition to a large amount of data available in the Tycho Brahe Corpus, the syntactic annotation of the corpus makes it possible to use the Corpus Search computational tool (available on the project website), which allows searching for specific syntactic contexts through queries.15 In the 39,761 sentences from the corpus, 624 sentences exhibited PP-ACCs. The results showed a vast variety of verbs accompanied by an overtly marked accusative argument.

After looking for all PP-ACCs, the data were divided into different verb classes, based on studies on Spanish and Catalan (Pineda 2012, 2017) and Portuguese (Cançado 1996, 2013). Pineda’s work, for instance, focuses on a similar ongoing change in Catalan, but from dative to accusative; these studies were used as reference in order to divide the data collected into different groups, so that it would be possible to run another search for NP-ACCs in the same type of predicates in which the PP-ACCs were found. This division resulted in 11 distinct verb classes: contact; dicendi; psychological; social interaction;16 transfer; transfer related to values; reverse transfer; transfer of knowledge; related to places; quantity; and other types of verbs. See some examples from the 17th century data below:

| Contact Verbs | |||||||||

| (22) | Para | tirar | toda | a | duvida, | oiçamos | ao | mesmo | Christo. |

| To | solve | every | the | doubt | listen.1PL | Pa(to). | the same | Christ | |

| ‘To solve every doubt, let’s listen to the same Christ.’ | |||||||||

| (V_004,70.149) | |||||||||

| Dicendi Verbs | |||||||||

| (23) | mandou | chamar | a | Dom | Duarte | de | Castellobranco | seu | cunhado, |

| asked | call | Pa(to) | Dom | Duarte | de | Castellobranco | his | brother-in-law, | |

| marido | de | sua | segunda | irmã | Dona | Luiza | de | Mendonça. | |

| husband | of | his | second | sister | Dona | Luiza | de | Mendonça | |

| ‘(someone) sent for Dom Duarte de Castellobranco his brother-in-law, | |||||||||

| husband of his second sister Dona Luiza de Mendonça.’ | |||||||||

| (C_002,139.107) | |||||||||

| Psych Verbs | ||||||||||||

| (24) | Tambem | lhe era | duro deixar | nos | claustros | adonde | se | criara, | ||||

| Too | her was hard | to leave | in.the | cloisters | where | CL.3rd | was raised | |||||

| companheyras, | e | amigas | de | tantos | anos, | e | na | corte | a | uma | irmã | |

| colleagues, | and | friends | of | many | years, | and | in.the | court | Pa(to) | a | sister | |

| a | quem | tanto | amaua. | |||||||||

| Pa(to) | whom | so much | loved | |||||||||

| ‘It also hard for her to leave colleagues and friends of many years in the | ||||||||||||

| cloisters where she was raised, and in the court a sister who she loved so much.’ | ||||||||||||

| (C_002, 214.1039) | ||||||||||||

| Verbs related to places | |||||||||||||

| (25) | (…) | a | communicaçaõ | com | Deos; | o | retiro | de | toda | a | creatura, | alguma | doente, |

| the | communication | with | God; | the | retreat | of | all | the | creature, | some | sick, | ||

| a | quem | visitaua | precizada | da | charidade | com | as | mãos | e | olhos | prezos. | ||

| Pa(to) | whom | visited | in need | of.the | charity | with | the | hands | and | eyes | fixed. | ||

| ‘(…) | the communication with God; the retreat of all creatures, some sick, | ||||||||||||

| who (he/she) visited with the hands and fixed eyes.’ | |||||||||||||

| (C_002,165.427) | |||||||||||||

| Quantity related verbs | ||||||||||

| (26) | Resta | nos | o que | a | tudo | excede | a | notícia | das | gentes, |

| Remain | us | what | Pa(to) | everything | exceeds | the | news | of.the | peoples, | |

| que | habitam | uma, | e | outra | margem; | |||||

| that | inhabit | one, | and | other | margin | |||||

| ‘It is left for us everything related to the news about the peoples that live one | ||||||||||

| margin and the other.’ | ||||||||||

| (B_001_PSD, 88.700) | ||||||||||

| Verbs of Transfer | ||||||||||||||

| (27) | (…) | mandou | Dom | Jorge | Mascarenhas, | Marquês | de | Montalvão, | e | Vice-Rei | ||||

| sent | Dom | Jorge | Mascarenhas, | Marquis | of | Montalvão, | and | Vice-King | ||||||

| daquele | Estado, | a | seu | filho | Dom | Fernando | Mascarenhas | no | ano | de | 1641 | |||

| of.that | State, | Pa(to) | his | son | Dom | Fernando | Mascarenhas | in.the | year | of | 1641 | |||

| ‘Dom Jorge Mascarenhas, Marquis of Montalvão, and Vice-King of that | ||||||||||||||

| State sent his son Dom Fernando Mascarenhas in the year of 1641.’ | ||||||||||||||

| (B_001_PSD,19.162) | ||||||||||||||

| Verbs related to transfer of values | ||||||||||||

| (28) | Que | esta | Praça | Diuina | assim | como | alumea | aos | peccadores, | premeya | ||

| That | this | Square | Diuina | just | as | enlights | Pa(to). the | sinners | awards | |||

| aos | Justos, | a | huns | abrindo | os | olhos, | a | outros | enchendo | o | coraçaõ. | |

| Pa(to).the | Just, | Pa(to) | some | opening | the | eyes | Pa(to) | others | fulfilling | the | heart | |

| ‘May this Divine Square just as it enlights the sinners, awards the Just, opens | ||||||||||||

| the eyes of some and fulfills the heart of others.’ | ||||||||||||

| (C_002,205.928) | ||||||||||||

| Verbs of reverse transfer | |||||||||||

| (29) | O | Padre | António | Vieira | com | excessivas | expressões | recebeu | nos | braços | |

| The | Priest | António | Vieira | with | excessive | expressions | received | in.the | arms | ||

| aos | dois | Padres, | como | a | irmãos, | como | a | filhos, | e | como | |

| Pa(to).the | two | Priests, | as | Pa(to) | brothers, | as | Pa(to) | children, | and | as | |

| a | heróicos | companheiros | de | sua | glória; | ||||||

| Pa(to) | heroic | fellows | of | his | glory; | ||||||

| ‘The Priest António Vieira with excessive expressions received two priests in the | |||||||||||

| arms, as brothers, as children, and as heroic fellows of his glory.’ | |||||||||||

| (B_001_PSD,193.1528) | |||||||||||

| Verbs of transfer of knowledge | ||||||||||

| (30) | Com | estes | foi | um | Índio | Cristão | antigo, | a | quem | instruíram |

| with | these | went | an | Indian | Christian | ancient, | Pa(to) | whom | instruct | |

| os | Padres, | e | adestraram | na | forma | do | Baptismo, | para | que | |

| the | Priests, | and | train | in.the | way | of.the | Baptism, | in order to | that | |

| nos | casos | precisos | os | instruísse, | e | baptizasse; | ||||

| in.the | cases | necessary | them | instruct, | and | baptized; | ||||

| ‘An ancient Christian Indian, who was instructed by the Priests, and trained in | ||||||||||

| the ways of the Baptism, went with them, in order to instruct and baptize the | ||||||||||

| cases needed.’ | ||||||||||

| (B_001_PSD,196.1545) | ||||||||||

| Verbs of social interaction | |||||||||

| (31) | Teue | grandissimos | dezejos | da | solidaõ, | e | de | imitar | nella |

| There | were enormous | desires | of.the | loneliness, | and | of | imitate | in.her | |

| aos | antigos | Annacoretas; | |||||||

| Pa(to) | old | anchorites; | |||||||

| ‘There were enormous loneliness desires, and of imitating the old anchorites.’ | |||||||||

| (C_002,206.949) | |||||||||

| Other types of verbs | ||||||||||||

| (32) | Que | esta | Praça | Diuina | assim | como | alumea | aos | peccadores, | premeya | ||

| That | this | Square | Diuina | just | as | enlights | Pa(to).the | sinners | awards | |||

| aos | Justos, | a | huns | abrindo | os | olhos, | a | outros | enchendo | o | coraçaõ. | |

| Pa(to).the | Just, | Pa(to) | some | opening | the | eyes | Pa(to) | others | fulfilling | the | heart | |

| ‘May this Divine Square just as it enlights the sinners, awards the Just, opens the | ||||||||||||

| eyes of some and fulfills the heart of others.’ | ||||||||||||

| (C_002,205.928) | ||||||||||||

In the next section, the details of the data collected will be presented, in order to analyze the behavior and the contexts in which PP-ACC cases were found in Historical Portuguese.

4. Results and Discussion

The search conducted in the corpus resulted in a total of 624 sentences with PP-ACCs, distributed throughout the centuries as shown in Figure 1: 17

Figure 1.

PP-ACC results.

The data show that PP-ACC occurrences increased in the 17th century; however, there followed an immediate fall in the 18th century (a preliminary analysis of this data was presented in Calindro 2017).

Gibrail (2003), who also analyzed the Tycho Brahe Corpus, attests to a high number of PP-ACCs with the NP ‘God’, as well as the combination guardar a Deus, ‘keep/save God’. In fact, in the data analyzed here, there were 96 examples of this structure in the 17th century, so these examples were excluded from this analysis. Moreover, it seems that such construction has become a crystallized expression even in Modern BP, in which sentences like adorar a Deus, lit. ‘worship ‘to’ God’, are still present in vernacular BP with an a-marked DO; hence, it does not show the variation and change process being addressed here.18

In the data we are concerned with, one explanation for the decrease in the PP-ACC cases in the 18th century may be the change in word order in Portuguese. Galves (2020, p. 21) attests to a rise in the VS order in the 17th century, followed by its fall in the next century. In fact, Ramos (1992) and Gibrail (2003) showed that PP-ACC was more productive in VS contexts.

Therefore, to verify whether word order influenced the occurrence of PP-ACCs in the corpus analyzed in this paper, the data was divided into the following contexts: SVO, VOS. Interestingly, the results showed that the order of the constituents does not seem to be relevant for a-marking the argument, as they presented very similar percentages, especially in the 16th (13% for both VS and SV) and the 17th century (15% for VS and 14% for SV). As mentioned before, we may assume that the accusatives ceased to be marked when the fixed SVO became more common in Portuguese, so we intend to look in more detail at the data collected in the future.

At the moment, two other facts are striking in the corpus analyzed: i. the quantity of PP-ACCs (624) in comparison with NP-ACCs (7756); ii. the increase in a-marked arguments in the 17th century, followed by an immediate fall in the 18th century, and the few cases found in the 19th century as well.

Ramos (1992), Gibrail (2003), and Döhla (2014) argue that Portuguese was greatly influenced by Spanish in the 17th century; therefore, these authors assume that this may explain why there was an increase in PP-ACCs in this particular century. Indeed, DOM is still a very productive phenomenon in Modern Spanish (López 2012, 2016; Fábregas 2013, a.o.). According to Gerards (2020, p. 2): “Spanish is the Romance language with the most advanced (…) DOM system”. Even Gil Vicente, a canonical Portuguese author, wrote plays in Spanish.

However, it does not mean this influence reached all the Portuguese population at that time. Galves (2020) observes that the written variety encountered in the sources available for diachronic empirical research corresponds to the written and spoken language of the dominant classes, who were probably the only ones who had access to literature. This register was presumably quite far from the oral language of the common people, who were mostly illiterate. Actually, the corpus we are dealing with is even further away from popular variety, insofar as it is composed of renowned authors, such as Camilo Castelo Branco and Almeida Garrett, but, unfortunately, this is the data we have available when it comes to Portuguese from the 16th to the 19th centuries.

Inasmuch as Spanish may have played a part in the increase of PP-ACCs in the 17th century, the smaller quantity of a-marked DOs in comparison to unmarked ones strongly suggests that there are language internal issues responsible for this marking.

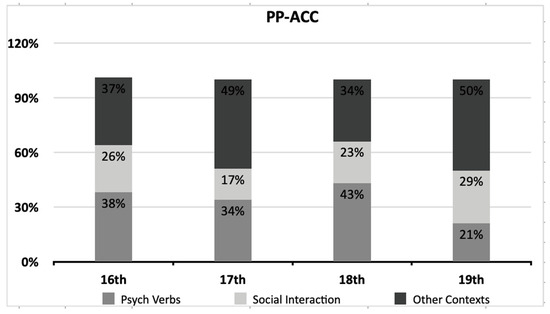

Since the data was divided into 11 verb classes, as mentioned in the methods section, each context was analyzed separately. The data showed that the quantity of a-marked DOs with psych verbs and social interactional verbs has remained a dominant factor throughout the centuries when compared to all the other nine verb classes combined, as we can see in Figure 2 (see also Calindro 2017). From the 328 overtly marked arguments in the 17th century, 33% (109) are sentences with psych verbs, 17% (57) are sentences with social interaction verbs, and 49% (162) are the other verb classes. Hence, the two former verb classes seem to be more relevant contexts for a-marked arguments to occur in. This is compatible with the fact that in Modern EP the Experiencer argument of some psych verbs is still introduced by the preposition a (cf. 6).19

Figure 2.

PP-ACC with psych verbs; social interaction verbs; other verbs.

When we analyze only the context of psych verbs, we notice a steady increase, proportionally, in PP-ACCs throughout the centuries, from 7.25% to 33.3% of the total data, as we can see in Table 2, when we compare pych verbs with PP-ACC and NP-ACC, followed by examples (33) and (34) from the 18th century, which illustrate PP-ACC and NP-ACC associated to psych verbs, respectively:20

| (33) | (…) | (ela) poderá muito bem agradar aos espectadores com um bom quadro. |

| may very well please Pa(to).the viewers with a good painting. | ||

| ‘(she) may very well please the viewers with a good painting.’ | ||

| (C_001, 140.1) | ||

| (34) | (…) | e os discursos gerais não podem ofender os particulares que são discretos. |

| and the speeches public not can offend the private citizens who are discreet | ||

| ‘and the public speeches cannot offend the private citizens who are discreet.’ | ||

| (C_001, 20.18) |

Table 2.

PP-ACC/NP-ACC with psych verbs throughout the centuries.

In the context of psych verbs, the Experiencer argument has referential properties typical of subjects. Thus, in order to guarantee its referential properties, a-marking was preserved in EP, while in BP it became unmarked. As psych verbs are two-place predicates, due to economy reasons, the fixed SVO order, attested by Galves (2020), seemed to be enough for the Experiencer to be read as accusative and not nominative in BP, so a-marking was not necessary anymore. We will return to this discussion in the next section.

5. Proposal

The differences in licensing indirect arguments in BP and EP led us to analyze the context in which the objects were traditionally labeled prepositional accusatives in Historical Portuguese. Recall that the starting point of this paper was the differences between Modern BP and EP, regarding a-marked objects in psych predicates (cf. 3). On the surface, a-marking has remained in psych predicates in EP (cf. 3a) and has disappeared in the same context in BP (cf. 3b).

As briefly discussed in the introduction, in Modern EP, the preposition a is a dummy dative marker that enters the derivation to assign dative Case to this element (for more details, cf. Torres Morais 2007; Figueiredo Silva 2007; Calindro 2015, 2016, 2020), similar to Spanish (Cuervo 2003) and other Romance languages. The dative case is confirmed by the possibility of the argument being displaced, as exemplified in (14), and for the alternation between the marked object (a-DP) and the dative clitic lhe. This alternation is no longer part of Modern BP, as the clitic lhe has been substituted by other strategies, as shown in examples (1b), (2b) and (3b) in the introduction (Calindro 2015); thus, the arguments introduced by para receive the structural oblique Case, while the complements of psych verbs are unmarked accusative, i.e., typical direct objects.

The examples in BP, EP, and Italian show crosslinguistic evidence that dative and accusative complements entail a different distribution. According to Manzini and Franco (2016), datives arise in the syntax to reflect a distinct mapping of Participant internal arguments in the event structure when necessary, as the presence of the dative may be due to the activation of a split eventive structure (Svenonius 2002). Manzini and Franco (2016) make an important distinction between Goal datives in ditransitive predicates, as the datives we saw in (1a), and DOM datives. The former are constituents required by the event, while the latter are constituents required by referential properties of the internal argument (similar to Bossong’s and López’s claims addressed previously in Section 2). Thus, based on Svenonius, Manzini, and Franco, DOM datives reflect neither a morphological regularity nor an accident. DOM may be a way to overtly assign case to internal arguments that show referential properties typical of subjects, for instance (cf. Bossong 1991; Gerards 2020).

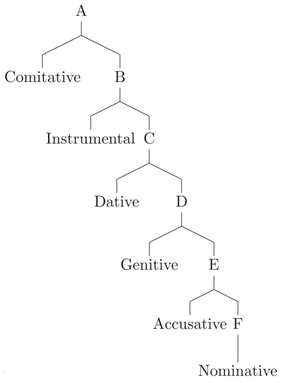

The data analyzed here showed this may be precisely the case with psych verbs, as the Experiencer argument in these structures remained a-marked over the years when it does not enter the derivation with its inherent case alongside its thematic role. Additionally, its case seems to have shifted from Accusative to Dative. This shift can be explained away using nanosyntax. In this approach, each syntactic–semantic feature is an independent head that projects (Baunaz and Lander 2018, p. 5); thus, cases can be decomposed into more primitive features and hierarchically organized (Caha 2009; Hardarson 2016), as we can see in (35):

| (35) |  |

| (Caha 2009, p. 23) |

In short, Caha (2009) observes that syncretic morphology in case assignment is not incidental across languages, as exemplified by the syncretism in Russian colored in gray in Table 3.

Table 3.

Syncretism in Russian.

The crosslinguistic data analyzed by Caha (2009) shows a contiguity relation between cases. Nominative pronouns and nominals can be syncretic with accusatives, for instance, but they will not be syncretic with genitive pronouns if the accusative has a different form. In this sense, Hardarson (2016) proposes a slightly different hierarchy of case features from Caha’s (cf. 36), which shows a direct contiguity between accusative and dative (without the interference of the genitive):

| (36) | NOM > ACC > DAT > GEN > LOC > ABL/INS>… |

According to Hardarson, the dative shares features directly with the accusative, but it is more specific than the accusative, as it is higher in the hierarchy and therefore composed of more features (cf. 36), including, for instance, accusative features.

In the context of psych verbs in EP, it seems that the historical PP-ACC underwent a specialization, which resulted in its accusative features being incorporated into the dative. Consequently, the Experiencer argument, which shows referential properties typical of subjects, displays an a-marked dative case in Modern EP to be mapped as an internal participant in the structure.21

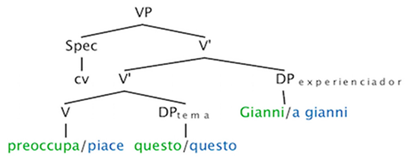

In BP, on the other hand, the PP-ACC argument with psych verbs is an unmarked accusative (cf. 3b). In order to account for this difference between EP and BP, let us return to the comparison of psych verbs in Italian and BP. In the argument structure of psych verbs, when the Experiencer is the complement of V’, the external argument position is available, as we can see in the representation of Italian proposed by Belletti and Rizzi (1988) and adapted by Figueiredo Silva (2007, p. 93) in (37):

| (37) |  |

For convenience, we repeat the examples with psych verbs in Italian, EP, and BP below:

| Italian | |||||

| (38) | Gianni | teme | questo. | ||

| Gianni | fears | this | |||

| (39) | Questo | preoccupa | Gianni. | ||

| This | worries | Gianni | |||

| (40) | a. | Questo | piace | a | Gianni. |

| This | pleases | Pa(to) | Gianni.DAT | ||

| b. | A | Gianni | piace | questo. | |

| Pa(to) | Gianni.DAT | pleases | this | ||

| (Belletti and Rizzi 1988, pp. 291–92) | |||||

In (39), the Theme questo is generated in the complement position of V, as well as the Experiencer Gianni, so the external argument position remains available. In (39), the Theme questo moves to receive Nominative Case, the unmarked Experiencer Gianni remains as an internal argument. Example (40b) shows that the marked Experiencer a-Gianni may move to a higher position, probably in the left periphery of the sentence (in Rizzi’s (1997) terms), but not to SpecIP, which is occupied by the Theme questo.22 In EP, the dislocation of the dative to the left periphery is possible as well, since the Experiencer carries the dative Case by being overtly marked (see 42), as we have just discussed.

| (41) | O | filme | agradou | ao | João. | (EP) |

| The | movie | pleased | Pa(to) | João.DAT | ||

| (42) | Ao | João | agradou | o | filme. | (EP) |

| Pa(to) | João.DAT | pleased | the | movie | ||

| (43) | O | filme | agradou | -lhe. | (EP) | |

| The | movie | pleased | -CL.DAT.3SG |

For BP, Figueiredo Silva (2007, pp. 93–94) argues that internal arguments licensed with psych verbs have inherent accusative case associated with the Experiencer theta role—João in (44) and (45). Subsequently, the Theme argument, o filme, ‘the movie’, in (44) and (45), may move to check its nominative case in SpecIP. Therefore, (45) is ungrammatical because the DP Theme O João already bears inherent ACC and cannot receive NOM in SpecIP.

| (44) | O | filme | agradou | o | João. | (BP) |

| The | movie | pleased | the | John.ACC | ||

| (45) | *O | João | agradou | o | filme. | (BP) |

| The | João.ACC | pleased | the | movie | ||

| (46) | O | filme | agradou | -o/ele. | (BP) | |

| The | movie | pleased | -CL.ACC.3SG./ACC |

It is remarkable that the only possible way to displace the Experiencer argument in BP to the left periphery would be to double it by a personal pronoun that will fill the accusative position, as in (47)23. It is interesting, though, that this position cannot be occupied by accusative clitics such as o/a, ‘him/her’; it may only be occupied by pronouns such as ele, ‘he’, which used to be only nominative but has undergone a change, and now it may also display accusative case, as we have seen before in (3b).24

| (47) | O | João, | o | filme | agradou | ele. |

| The | João | the | movie | pleased | he.ACC |

Furthermore, historically, BP has become quite resistant to the inversion of constituents (Galves 2020; Martins 2011), which also explains the ungrammaticality of (45). Therefore, we assume that the fixed SVO order is also a key factor on the loss of marked accusative in BP, as the internal argument receives inherent accusative case when entering the derivation in the complement position of V.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we explored the variation and change of a-marked arguments in Historical Portuguese, with a specific focus on its occurrence in historical texts from the 16th to the 19th centuries. The results of the data analysis demonstrated that the cases of PP-ACCs increased in the 17th century, followed by a decrease in the 18th century. The number of PP-ACC occurrences is much less frequent than of NP-ACCs, though, which has led other authors to treat a-marked arguments as a marginal phenomenon in Portuguese. Some authors deal with this phenomenon using the label PP-ACC, while others adopt the concept of DOM, as this is a widespread phenomenon in other Romance languages, such as Spanish. However, in order to accurately address the differences and/or similarities of PP-ACCs and DOM in Portuguese, it would have been necessary to address features of the objects, such as animacy, definiteness, and referentiality of the a-marked arguments. These important characteristics will be taken into account in future work, as they were not part of the scope of this paper.

Finally, when the verb classes found in the data were examined, it became evident that the set of psych verbs showed a different path from other contexts, as the quantities even increased along the centuries (see Table 2). In EP, there are still a-marked arguments in psych predicates, as opposed to the zero morpheme in BP. The analysis led to the conclusion that, in these cases in EP, the accusative became the structural marked dative, which guarantees the thematic reading of the Experiencer to the internal argument of psych verbs. Meanwhile, in BP, to avoid an ambiguous interpretation, the argument displays inherent accusative case; hence, the Experiencer remains in the accusative position and the Theme rises to receive nominative, so overtly marking the Experiencer is no longer necessary.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used for the research can be found at the Tycho Brahe project website.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In BP, pronouns that used to be only nominative may also occur in accusative contexts (cf. Kato 2012); we will return to this topic further in this text. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | The first part of the research focuses solely on EP authors from the Tycho Brahe Corpus (Unicamp). In future work, we intend to analyze texts from Brazilian authors. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Cyrino and Irimia (2019, p. 187) point out that direct objects may still be overtly marked in Portuguese. Animated quantifiers may be umarked or overtly marked, especially if dislocated (see iii): i. Ele visitou todos, ‘He visited everyone’; ii. Ele visitou a todos, ‘He visited Pa(to) everyone’; iii. A todos, ele visitou, ‘Pa(to) everyone, he visited’. We intend to address this context of quantifier, and others mentioned by the authors in future work. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | The example was taken from the Tycho Brahe Corpus (Unicamp). The code V_004, 002.1819 indicates the following: V_004—text (in this case: Sermões do Padre Vieira—Padre Vieira Sermons); 202—page number in the original; and 1819—line number. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | See Historical Corpus of Portuguese Tycho Brahe: http://www.tycho.iel.unicamp.br/~tycho/corpus/en/index.html (accessed on 4 November 2023). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | The dative clitic lhe is still active in some areas of Brazil, but it was recategorized as second person (cf. Figueiredo Silva 2007; Martins et al. 2019). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | We are using Chomsky (1981) Government and Binding terms, because the discussion on psych verbs will be based on Belletti and Rizzi (1988), as well as Figueiredo Silva (2007), who still adopt this framework, and not on more recent versions of the generative approach, such as the Minimalism Program (Chomsky 1995). | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | We would like to thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing it out that both buscar and querer may take an unmarked DO, as well as +human DOs without a-marking—Busco una persona paea este puesto. As our focus is not Spanish, we intend to confirm if Bossong is right that there are verbs that always select marked objects in future work. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Additionally, during data collection, in order to use the computational tools described in the methods section, it is not possible to search for such categories, because the NPs in the corpus are not annotated according to these specific features. The methodology chosen permitted us to run a search in a corpus of 39,761 words very quickly. In future work, an analysis based on the thematic role of the complements may be indeed an interesting path to pursue. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Gibrail (2003) analyzed the texts from the Tycho Brahe Corpus. Ramos (1992, pp. 68–69) worked with letters and theater plays written between the 16th and the 20th centuries and newspapers from the 20th century. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | See Pires (2017) for another analysis on marked DOs in Historical Portuguese. Besides animacy, the author also divides the corpus according to the specificity and definiteness of the object. Additionally, works by Schwenter (2006) take specificity and definiteness into account when comparing DOM in Spanish and BP. I intend to analyze these features on this corpus in future work. Finally, Cyrino and Irimia (2019) also address marked DOs in Modern BP. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | According to Gonçalves and Raposo (2014, p. 1175), the following verbs present the same behavior as agradar—’please’: apetecer—‘feel like’, desagradar—‘upset’, importar—‘matter’, interessar—‘interest’, repugnar—‘repel’ etc. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | See note 1. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | Even though Matias Aires was born in Brazil, his parents were Portuguese, and he moved to Portugal at the age of 11, where he was raised and educated. Therefore, as his contact with written Portuguese was mainly in Portugal and it seems his text would have the same characteristics as the other Portuguese writers, his work was maintained for this analysis. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | The Corpus Search computational tool allows us to look for specific syntactic contexts, which is extremely convenient for syntactic diachronic studies. Query (ii), for example, guarantees the outcome of the search to be the contexts in which there is a PP-ACC (IP* idoms PP-ACC) in a structure where the NP subject precedes the verb (NP-SBJ* iprecedes VB*|TR*|HV*|ET*), hence SVO.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | It has been pointed out to us that the social interaction and transfer of knowledge groups seem to overlap. However, in this analysis, the intention was to separate verbs that are related to the idea of knowledge itself—such as conhecer (to know), instruir (to instruct), reconhecer (to recognize)—from social interaction verbs that demand a two-participant scenario, such as abraçar (to hug), acompanhar (to join), atacar (to attack), calar (to silence), consultar (to consult), convidar (to invite), curar (to cure), and imitar (to imitate). However, the name ‘transfer of knowledge’ may indeed not be the best choice as it is also a type of social interaction; we intend to revise all the data in future work and will take this issue into account. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | In absolute numbers, we have the following: 200 occurrences in the 16th century, 328 in the 17th, 83 in the 18th, and 13 in the 19th. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | In fact, if we replace ‘God’ with another noun, such as ‘John’, and use it as an a-marked argument with the same verb adorar ao João, ‘to worship John’, the term ‘John’ would appear to be some sort of deity. Therefore, in modern BP, if the speaker intends to use adorar in the same sense as ‘love’/‘like’, the argument will be unmarked: Eu adoro João, ‘I love John’. Moreover, when the complement has [-human] or [-animate] features, using the preposition a to label it makes the sentence very odd: #Eu adoro ao meu gato, ‘I love my cat’; or ungrammatical: *Eu adoro ao sorvete, ‘I love ice cream’. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | In this paper, the context of social interactional verbs will not be addressed. Most examples with this verb class in the corpus were a combination of the verb servir, ‘to serve’, and title DPs, such as Vossa Excelência, ‘Your Honor’, among others. In the 17th century, for instance, there are 18 occurrences with this arrangement. According to Sornicola (1997), the verb ‘to serve’ derives directly from Latin and has always been marked in Italo-Romance. Therefore, in future work, it will be interesting to investigate this particular context and DO a-marking. I would like to thank Luigi Andriani for calling my attention to this fact. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | An anonymous reviewer has pointed out that the difference among the tokens from the 16th to the 19th centuries may be an issue. We agree, but as explained in the methods section, we searched for PP-ACCs to find all the occurrences in the corpus. Then, we searched for the same verbal contexts with NP-ACCs, so we did not restrict the types of occurrences. In future work, we intend to look more carefully at why there was a decrease in both PP-ACCs and NP-ACCs in the 18th and 19th centuries in the corpus and hopefully compare with data from other corpora. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | The specific reasons for the shift from accusative to dative we leave for future work. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | It is not in the scope of this paper to discuss where exactly in the left periphery the Experiencer argument moves to. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | An anonymous reviewer asked if the following dislocation in EP is possible: Ao João, lhe/a ele agradou o filme, ‘To João, CL.DAT3SG/to him pleased the movie’—this sentence would not be possible in EP due to lhe in a proclitic position, and also a ele is only licensed in EP with clitic doubling—O filme agradou-lhe a ele, with a contrastive reading meaning ‘the movie pleased him not her’, for example. With enclisis and clitic left dislocation, the topicalization is grammatical in EP: Ao João, agradou-lhe o filme, ‘To João, pleased- CL.DAT.3SG the movie’. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 24 | I would like to thank Matheus Alves for calling my attention to this example. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Andriani, Luigi. 2015. Semantic and Syntactic Properties of the Prepositional Accusative in Barese. Linguistica Atlantica 34: 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Baunaz, Lena, and Eric Lander. 2018. The Basics. In Exploring Nanosyntax. Edited by Lena Baunaz, Karen De Clercq, Liliane Haegeman and Eric Lander. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bazenga, Aline, and Lorena Rodrigues. 2019. Usos do clítico lhe em variedades do português [Uses of clitic lhe in Portuguese varieties]. In Pelos Mares da Língua Portuguesa 4. Edited by António Ferreira, Carlos Morais, Maria Fernanda Brasete and Rosa Lídia Coimbra. Aveiro: Editora Universidade de Aveiro. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, Adriana, and Luigi Rizzi. 1988. Psych-verbs and Theta-theory. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 6: 291–352. [Google Scholar]

- Bossong, Georg. 1991. Differential object marking in Romance and beyond. In New Analyses in Romance Linguistics: Selected Papers from the XVIII Linguistics Symposium on Romance Linguistics. Edited by Dieter Wanner and Douglas A. Kibbee. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins, pp. 143–70. [Google Scholar]

- Caha, Pavel. 2009. The Nanosyntax of Case. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Tromsø, Tromsø, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Calindro, Ana. 2015. Introduzindo Argumentos: Uma proposta para as sentenças ditransitivas do português brasileiro. [Introducing arguments: The case of ditransitives in Brazilian Portuguese]. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of São Paulo, São Paulo. [Google Scholar]

- Calindro, Ana. 2016. Introducing indirect arguments: The locus of a diachronic change. Rivista di Grammatica Generativa 38: 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Calindro, Ana. 2017. O acusativo preposicionado na história do português: o caso dos verbos psicológicos. Revista da Academia Brasileira de Filologia XXI: 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Calindro, Ana. 2020. Ditransitive constructions: What sets Brazilian Portuguese apart from other Romance languages? In Dative Structures in Romance and Beyond. Edited by Anna Pineda, Jaume Mateu and R. Etxepare. Berlin: Language Science Press, pp. 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cançado, Márcia. 1996. Verbos Psicológicos: Análise Descritiva dos Dados do Português Brasileiro. Revista de Estudos da Linguagem 4: 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cançado, Márcia. 2013. Catálogo de Verbos do Português Brasileiro: Classificação Verbal Segundo a Decomposição de Predicados [Brazilian Portuguese verb catalogue: Verbal classification according to predicate decomposition]. Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, Beatriz, and Rozana Naves. 2010. Verbos Psicológicos: Hipóteses de mapeamento da estrutura argumental e aquisição da linguagem [Psych Verbs: Mapping hypothesis of the argument structure and language acquisition]. In Proceedings of IX Encontro do CELSUL. Palhoça: Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on Government and Binding. Dordrecht: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corriente, Federico. 1997. Poesía dialectal árabe y romance en Alandalús. Madrid: Gredos. [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo, Cristina. 2003. Datives at Large. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cyrino, Sônia, and Monica Irimia. 2019. Differential Object Marking in Brazilian Portuguese. Revista Letras 99: 177–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delille, Karl Heinz. 1970. Die geschichtliche Entwicklung des präpositional Akkusativs im Portugiesi-schen. Bonn: Romanisches Seminar der Universität Bonn. [Google Scholar]

- Döhla, Hans-Jörg. 2014. Diachronic convergence and divergence in differential object marking between Spanish and Portuguese. In Stability and Divergence in Language Contact: Factors and Mechanisms. Edited by Kurt Braunmüller, Steffen Höder and Karoline Kühl. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 265–89. [Google Scholar]

- Fábregas, Antonio. 2013. Differential Object Marking in Spanish: State of the art. Borealis. An International Journal of Hispanic Linguistics 2: 1–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo Silva, Maria Cristina. 2007. A perda do marcador dativo e algumas das suas consequências [The loss of the dative marker and some consequences]. In Descrição, História e Aquisição do Português Brasileiro. Edited by Ataliba Castilho, Torres Morais, Maria Aparecida, Ruth Lopes and Sônia Cyrino. Campinas: Pontes Editores, pp. 85–110. [Google Scholar]

- Galves, Charlotte. 2001. Ensaios Sobre as Gramáticas do Português [Essays on the grammars of Portuguese]. Campinas: Editora da Unica. [Google Scholar]

- Galves, Charlotte. 2007. A língua das caravelas: Periodização do português europeu e origem do português brasileiro [The language of the caravels: European Portuguese periodization]. In Descrição, História e Aquisição do Português Brasileiro. Edited by Ataliba Castilho, Torres Morais, Maria Aparecida, Ruth Lopes and Sônia Cyrino. Campinas: Pontes Editores, pp. 513–28. [Google Scholar]

- Galves, Charlotte. 2020. Mudança sintática no português brasileiro [Syntactic change in Brazilian Portuguese]. Cuadernos de la Alfal 12: 17–43. [Google Scholar]

- Galves, Charlotte, Aroldo Andrade, and Pablo Faria. 2017. Tycho Brahe Parsed Corpus of Historical Portuguese. Available online: https://www.tycho.iel.unicamp.br/home (accessed on 8 August 2020).

- Gerards, David. 2020. Differential Object Marking in Romance Languages. Leipzig: University of Leipzig, Ms. [Google Scholar]

- Gibrail, Alba. 2003. O Acusativo Preposicionado do Português Clássico: Uma Abordagem Diacrônica e Teórica. [The prepositional accusative in Classical Portuguese: A diachronic and theoretical approach]. Master’s thesis, University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, Anabela, and Eduardo Raposo. 2014. Verbo e sintagma verbal [Verb and verbal phrase]. In Gramática do Português. [Portuguese grammar]. Edited by Eduardo Raposo, Maria Fernanda Nascimento, Maria Antónia Mota, Luísa Segura and Amália Mendes. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, vol. II, cap. 28. pp. 1155–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hardarson, Gísli. 2016. A case for a Weak Case contiguity hypothesis: A reply to Caha. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 34: 1329–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Mary. 2012. Caso inerente, caso default e ausência de preposições [Inherent case, default case and the absence of prepositions]. In Por amor à Linguística, 1st ed. Edited by Adeilson Sedrins. Maceió: Edufal, pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, Mary, Sônia Cyrino, and Vilma Corrêa. 2009. Brazilian Portuguese and the recovery of lost clitics through schooling. In Minimalist Inquiries into Child and Adult Language Acquisition. Edited by Acrisio Pires and Jason Rothman. Jason: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 245–72. [Google Scholar]

- López, Luis. 2012. Indefinite Objects: Scrambling, Choice Functions, and Differential Marking. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- López, Luis. 2016. (In)Definiteness, Specificity, and Differential Object Marking. In Manual of Grammatical Interfaces in Romance. Edited by Susann Fischer and Christoph Gabriel. Berlin and New York: de Gruyter, pp. 241–65. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, Rita, and Ludovico Franco. 2016. Goal and DOM datives. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 34: 197–240. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Ana Maria. 2011. Clíticos na história do português à luz do teatro vicentino [Clitics in history of Portuguese in the light of Vicente’s plays]. Estudos de Lingüística Galega 3: 83–109. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, Marco Antonio, Kássia Moura, and Franklin Costa da Silva. 2019. Análise diatópico-diacrônica dos complementos pronominais de verbos na escrita brasileira dos séculos XIX e XX [Diatopic-diachronic analysis of verbs pronoun complements in Brazilian writing of the 19th and 20th centuries]. Working Papers em Linguística 20: 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naves, Rozana. 2005. Alternâncias Sintáticas: Questões e Perspectivas de Análise [Syntactic Alternations: Issues and analysis perspectives]. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Universidade de Brasília, Brasilia, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, Anna. 2012. What lies behind dative/accusative alternations in Romance. Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 2012: Selected Papers from ‘Going Romance’ 2012: 123–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, Anna. 2017. From dative to accusative: An ongoing syntactic change in Romance. Paper presented at Anglia Ruskin—Cambridge Linguistics Seminars for Easter Term, Anglia Ruskin University, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK, May 19. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, Aline. 2017. A Marcação Diferencial de Objeto no Português: Um Estudo Sintático-Diacrônico. [Diferential Object Marking in Portuguese: A Syntactic Diachronic Study]. Master’s thesis, University of Campinas, Campinas. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, Jânia. 1992. Marcação de Caso e Mudança Sintática no Português do Brasil: Uma Abordagem Gerativista e Variacionista. [Case Assignment and Syntactic Change in Brazilian Portuguese: A Generative and Variationist Approach]. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The Fine Structure of the Left Periphery. In Elements of Grammar: Handbook of Generative Syntax. Edited by Liliane Haegeman. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 281–337. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenter, Scott. 2006. Null objects across South America. In Selected Proceedings of the 8th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sornicola, Rosanna. 1997. L’oggetto preposizionale en siciliano antico e in napoletano antico: Considerazioni su un problema di tipologia diacronica. Italienische Studien 18: 66–80. [Google Scholar]

- Svenonius, Peter. 2002. Icelandic Case and the Structure of Events. Journal of Comparative 55 Germanic Linguistics 5: 197–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Morais, Maria Aparecida. 2007. Dativos. [Datives]. Professorship thesis, USP, São Paulo, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Morais, Maria Aparecida, and Heloisa Salles. 2010. Parametric change in the grammatical encoding of indirect objects in Brazilian Portuguese. Probus 22: 181–209. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Morais, Maria Aparecida, and Rosane Berlinck. 2018. O objeto indireto do português: Argumentos aplicados e preposicionados [Portuguese indirect object: Applied arguments and prepositional]. In História do Português Brasileiro: Mudança Sintática do Português Brasileiro: Perspectiva Gerativista. Coord. by Sonia Cyrino and Maria A. Torres Morais. São Paulo: Contexto. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).