1. Introduction

Duration adverbials are part and parcel of the tense and aspect system of any language and are usually key ingredients for uncovering an aspectual system.

Vendler (

1967)’s seminal work on defining the English aspectual system and coining the quadripartition states–activities–accomplishments–achievements did exactly that.

Santos (

1996b,

1996a,

2004) replicated Vendler’s methodology for Portuguese.

However,

Santos (

1996b,

1996a,

2004) was concerned with the big picture of the overall systems and did not have access to large corpora. In this paper, I will concentrate specifically on particular adverbials, in this case, describing duration, to have a closer look at their behaviour, looking at a large number of occurrences.

Sentences with

for in English have two very different translations into Portuguese depending on whether the duration includes the present moment:

| (1) | I have lived in Oslo for two years. |

| Vivi em Oslo durante dois anos. [period totally in the past, using Perfeito1] |

| live-Perfeito;1S in Oslo for two year-PL |

| Vivo em Oslo há dois anos. [period including now, using Presente2] |

| live-Presente;1S in Oslo since two year-PLl |

This is one of the first instances of contrastive data that any foreign learner of Portuguese has to deal with. In fact, this is a general contrast between Germanic and Romance languages, but for ease of exposition, I will only deal with Portuguese and English in the present paper.

The second contrastive data, and one which we will be especially concerned with here, is that a

for adverbial can, in fact, be translated into Portuguese in two additional ways using the verb in Perfeito (‘vivi’), namely without a preposition or with the preposition

por. Cf. the following examples, also translating

I have lived in Oslo for two years:

| (2) | Vivi em Oslo por dois anos. [period totally in the past, using Perfeito] |

| live-Perfeito;1S in Oslo for two year-PL |

| Vivi em Oslo dois anos. [period totally in the past, using Perfeito] |

| live-Perfeito;1S in Oslo two year-PL3 |

It is this variability—or rather, the alternation between

por and

durante followed by temporal duration— that I want to study closer in this paper, using empirical data from distinct corpora.

This is an example of what

Talmy (

1983, p. 277f) has beautifully pointed out in his paper about how languages structure space:

Rather than a contiguous array of specific references, languages instead exhibit a smaller number of such references in a scattered distribution over a semantic domain. […] Their locations must nevertheless be to a great extent arbitrary, constrained primarily by the requirement of being “representative” of the lay of the semantic landscape, as evidenced by the enormous extent of non-correspondence between specific morphemes of different languages, even when these are spoken by the peoples of similar cultures.

So, although Portuguese and English are obviously related, they mark in their grammars different details of temporal specification.

This paper is structured as follows. In

Section 2, I discuss grammars and research papers on the subject of these adverbials. In

Section 3, I discuss the objectives of the present study and describe the corpora used in

Section 4. Then,

Section 5,

Section 6 and

Section 7, respectively, discuss duration length, tense usage, and more specific questions, such as planned vs. non-planned periods of time. This paper ends with a study of convergence and divergence between European Portuguese (EP) and Brazilian Portuguese (BP) in

Section 8, before concluding in

Section 9.

2. What Grammars and Previous Research Say about Duration Adverbials

2.1. Reference Grammars

It is a well-known fact that one can use Ø/durante/por to specify a period of time in Portuguese. However, there are not many works that discuss, let alone explain, why there are three competing forms. In general grammars of Portuguese, we see this presented without further comment.

In subsection

§16.3.1 Duração de estados e processos (‘duration of states and processes’),

Móia and Alves (

2013, p. 575ff) stated the following:

A duração de estados e processos é tipicamente marcada—em português europeu contemporâneo—por sintagmas com a preposição durante, que indicam o tempo durante o qual uma situação se mantém. […] Um facto linguístico interessante é que a preposição durante pode muitas vezes ser omitida sem alteração substancial de significado. (The duration of states and processes is typically marked—in contemporary European Portuguese—by phrases with the durante preposition, which indicate the time during which the situation is maintained. (…) An interesting linguistic fact is that the preposition durante can often be omitted without significantly changing the meaning. (my translation))

As for

por,

Móia and Alves (

2013, p. 577) added the following:

Quanto às expressões com por, apesar de não serem frequentes no português europeu atual como marcadores de duração equivalentes a durante, ao contrário do que acontece no português brasileiro, são possíveis em alguns contextos especiais;

A emissão esteve no ar apenas por alguns segundos.

A preposição por tem, entretanto, um uso corrente como marcador de uma forma particular de duração, que designamos duração planeada.

A Ana saiu por meia hora.

A Ana foi para Paris por duas semanas. (As for the expressions with por, although they are not frequent in present-day European Portuguese as duration markers equivalent to durante, in contrast to what happens in Brazilian Portuguese, they are possible in some special contexts: The emission was on air just for some seconds. The preposition por has, meanwhile, current use as a marker of a particular kind of duration, which we call planned duration. (my translation))

As for Brazilian grammars, I was only able to find a short mention of

por in the context of its relevant meaning by

Bechara (

[1971] 1999, p. 318), where the grammarian cited 14 meanings or uses of

por, of which the tenth referred to “time, duration”. As for

durante,

Bechara (

[1971] 1999, p. 299) only stated that it is considered a derived preposition from the verb

durar (‘to last’) but did not discuss its meaning or use.

This distinction was discussed in passing by (

Santos 1993, pp. 401–2), who claimed that the difference between

durante and

por is related to the original aspectual class before it becomes an accomplishment (in both cases). In this analysis,

por naturally applies to temporary states and

durante applies to activities (using a mix of new and Vendler’s categories).

4 2.2. Research Works

The first research I am aware of about

durante and

por and their differences was published by Rosinda Rodrigues in 1994 (

Rodrigues (

1994)). She looked at the felicity of these duration adverbials with Vendler’s four aspectual classes, relying on her own judgements in basic sentences. She made the following claims:

Because of the subinterval property, states and activities can occur with duration adverbials with durante (p. 500).

She discussed event-states (events that include a resulting state, in terms of the aspectual classification by

Borillo (

1984)). The examples given were

parar, cessar, partir, vir, deixar, fechar, abandonar (‘stop’, ‘quit’, ‘leave’, ‘come’, ‘leave’, ‘close’, ‘abandon’) on page 501, and she stated that they are felicitous with

durante.

Accomplishments in the progressive can occur with durante adverbials (p. 502).

Pluralised or iterative events occur with durante adverbials (p. 503).

Temporary situations can be used with por but not with durante.

When used with achievements,

por implies saturation. In other words, instead of indicating iterativity, it describes a total amount. This analysis was inspired by

Berthonneau (

1991).

5 The example given was:

- (3)

A Inês comeu gelados por um mês. (I. ate ice cream for a month (before getting fed up)).

Por can denote a planned interval before it is over.

Later on,

Móia (

2001) contended that

por is used by BP speakers in contexts where EP speakers would use

durante. As for European Portuguese, he claimed the following:

Por is not felicitous with states or activities but acceptable with achievements (he also used Vendler’s classification), in which case, it measures the duration of the result.

Por is more felicitous when the situation refers to a prediction for the future.

Por is more felicitous when the situation can be controlled.

Por is more felicitous when the period is vague.

Most of these claims were based on acceptability judgements, with three possibilities: “OK”, “?”, or “??”. However, how these judgements were elicited was not explained so they were probably mainly those of the author. Some claims were illustrated with corpus examples but no corpus study was undertaken.

Móia (

2011) revisited these matters, separating duration adverbials that work as arguments from those that are adjuncts. He suggested a binary partition of adjunct adverbials: those that are anchored and those that are not (referred to, respectively, as temporal location adverbs and strict duration adverbs by

Móia (

2005)). Anchored adverbials are those that, in addition to specifying the duration, also convey time (“normally coincident with the temporal perspective point implied by the tense” (

Móia 2011)).

6 In the tables presented in the aforementioned paper,

durante can only be used to specify the non-anchored duration of atelic situations. However, Móia did not discuss the difference between

durante and

por, except in a footnote by

Móia (

2005, p. 62), which is repeated here:

Modern European Portuguese does not normally use por-phrases to express simple atelic duration (unless in some restricted cases, e.g., those expressing very short duration like só a vi por uns segundos [‘I only saw her for a second’]). However, there are many instances of this use in classical Portuguese writers.

It should be clarified that in what follows, I deal solely with what Móia calls “strict duration adverbs”, not anchored ones, when annotating and revising the corpus data.

As for Brazilian Portuguese,

Basso and Bergamini-Perez (

2016, p. 353ff) discussed several duration adverbials and claimed that the main difference between

durante and

por is the kind of duration measures accepted: while

por only accepts “primary” duration measures involving explicit temporal nouns,

durante also accepts “secondary” measures describing an event, like

jogo (‘game’),

filme (‘film’), and

peça (‘play’). Additionally, they explicitly mentioned the high similarity of the two adverbials, thus supporting Móia’s contention about their equivalence in Brazilian Portuguese.

3. Corpus Analysis

The research I describe here tries to validate (or challenge) these claims, as well as identify some other reasons and/or uncover new linguistic generalisations on these matters.

Specifically, I investigate the following factors:

In some cases, it is possible to automatically identify the features discussed, whereas in other cases, I use a random subset of cases and judge them one by one.

In any case, an important aspect of the present work is that it does not rely on the author’s idiolect to obtain examples, nor does it select examples according to a particular purpose: it is corpus-based. That is, it uses corpora of authentic examples. When, due to the sheer volume of the examples, it is impossible to analyse every example, the choice is again not directed by a particular theory or aim; it is simply random.

However, a corpus-based study does not mean that the linguist’s intuition is not called for. On the contrary, it has to be duly exercised when interpreting a plethora of examples, even though they may not be part of her idiolect at all. This is especially true when the material encompasses different varieties and ages, let alone different literary authors’ styles. Because I am aware that this interpretation may, at times, be challenged, and in order to allow for further work on the subject, all examples used, analysed, and referenced in the present paper are available for inspection at

https://www.linguateca.pt/documentacao/artigoPorDurante.html (accessed on 1 March 2024).

4. Corpora Used

I used four different corpora, each containing roughly the same amount of Brazilian and Portuguese material, covering four different genres: newspaper texts from 1994–1995 from the CHAVE collection (

Santos and Rocha 2005); specialised newspaper texts from the 1950s, 1970s, and 2000s about football, fashion, and health from the ConDiv corpus (

Soares da Silva 2008); literary fiction from the year 1500 onwards from the Literateca corpus (

Santos 2019); and transcribed interviews from the Museu da Pessoa corpus (

Almeida et al. 2001). The number of occurrences of the dration adverbials appear in

Table 1.

All these corpora are publicly available for querying on the Web through the AC/DC project (

Santos 2014). Some of them are also available for download.

The sizes of the different corpora, together with the (unrevised) counts of

durante and

por duration phrases in each variety, are presented in

Table 2. In

Appendix A, I provide the actual search expressions to allow for reproducibility, as well as the concrete versions of the corpora, which can change over time. As the corpora have not been fully revised, it is important to be aware that, notwithstanding the good performance of PALAVRAS (

Bick 2000), some cases may be missing, and others spurious. Some of these numbers are revised in the following sections.

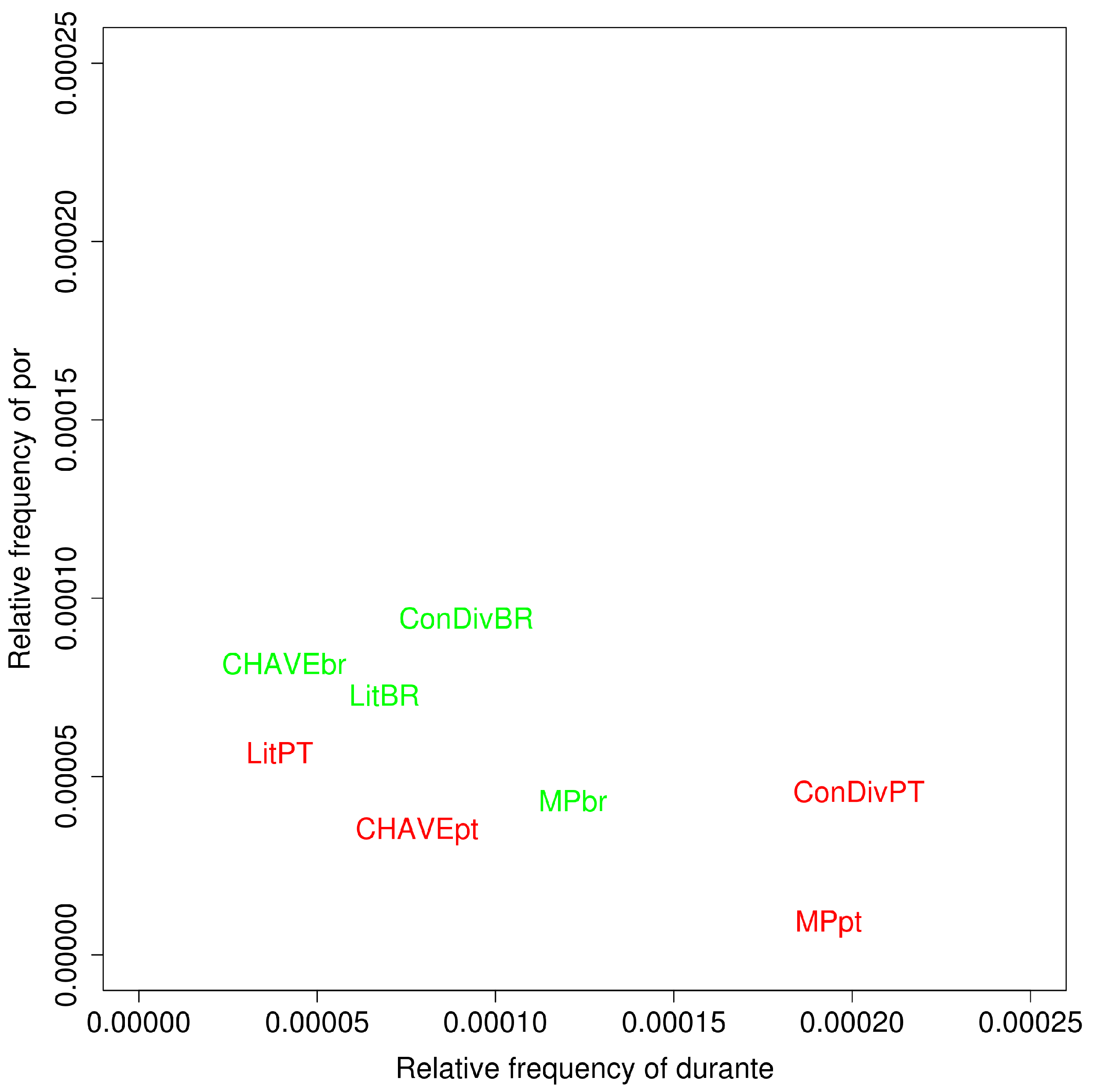

Another way to observe the differences is in

Figure 1.

One can immediately see that there is a wide range of differences among the corpora as far as these temporal adverbials are concerned. While in CHAVE, each variety is a mirror image of the other (with durante more frequent than por in Portugal, and por more frequent than durante in Brazil), in the other corpora, the two varieties behave more similarly. However, while durante predominates in interviews and specialised journalese, por is far more frequent in literary texts.

The rest of this paper is an attempt to explain these differences and identify or confirm the reasons for the use of each of these prepositions.

5. Long and Short Durations

I started by inquiring whether por emphasises short duration and durante emphasises long duration, assuming that no preposition represents the neutral case.

First, I counted the three instances of each duration noun in Literateca. It should be noted that “others” includes more than duration,

8 and “Total” includes a few other cases. I ordered the nouns by duration length, as shown in

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6. I also listed the vague cases, notably with the meta-noun

tempo (‘time’), to give a better quantitative characterisation of these durational phrases.

9The data confirm that

por is more frequent for short durations across all corpora and more frequent for vague duration specifications. Most interestingly, durations seem to sharply differ by genre. In the literature, as shown in

Table 3, there is a multitude of short durations unparalleled by any other kind of text.

One can also observe that the specification of temporal duration (using the adverbials we are concerned with here) is much more relevant in news compared to interviews (as described in

Table 4), even if those interviews are supposed to mirror the interviewee’s life and might, therefore, prompt several temporal descriptions.

In

Table 6, we can see that daily newspapers mainly report situations that last weeks, months, or years, whereas the specialised newspapers shown in

Table 5 are more focused on days, hours, minutes, and seconds. This may occur because of sports reporting—football in this case—but texts on health also seem to address this kind of temporal period).

However, it is not only absolute temporal duration that counts. An examination of the examples shows that what is long and what is short is dependent on the kind of event or situation described. Long and short are relative to the noun they modify (contrast long way and long hair), and, I would claim, are also often subjective.

The following examples show this clearly, and I believe that the durations are regarded as short given the entire period that the main clause event covers, namely a medieval war, the writing of a novel, and a period in a depressive mood:

| (4) | (a) As memórias desses tempos não nos dizem quem quebrou as pazes juradas: só sabemos que a luta interrompida por dois anos começou de novo. (‘the fight interrupted for two years started again’). |

| (b) Em Junho, de novo interrompi A Selva, desta vez não por alguns dias, mas por dois meses e sem desgosto algum, com um prazer todo febril e exultante. (‘I interrupted the book, nor for some days, but for 2 months’). |

| (c) Começou a viver solitário, e desse programa só o carnaval o arrancou por três dias. (‘out of that state of mind only Carnaval was able to grab him for three days’). |

Similarly, the following examples show that different absolute durations can be regarded as long given the context. Three days, seven weeks, and two months can be considered long for plundering, the preparation of a trip, and a convalescence, respectively.

| (5) | (a) O bairro levantado ficou durante três dias entregue ao saco e, expulsos os seus habitantes, foi arrasado. (was for three days ransacked). |

| (b) Jacinto não conhecia Torges, e foi com desusado tédio que ele se preparou, durante sete semanas, para essa jornada agreste. (with a rare tedium he prepared himself for seven weeks’). |

| (c) Silveira assistiu ao enfermo durante dois meses de morosa convalescença. (for two months of slow convalescence). |

So, in order to really ascertain whether a particular duration is regarded as short or long definitely requires close reading and manual annotation of each case, as reported in Table 10 in

Section 7.

Another important issue is whether por marks temporariness, as in the Portuguese expression por enquanto (in English, “for the moment” or “for the time being”). Something temporary is obviously shorter than what is considered permanent.

In addition, one tends to wish that bad things take less time than good things, which means that one would expect a preference for por when reporting bad things and durante when reporting good things. It is, therefore, important to note that if por carries with it a negative opinion, it might be rhetorically minimised, and then it would be natural to occur more often with shorter durations anyway. This means that these three features—short period, negative evaluation, and temporariness—may not be independent factors, but all somehow—and possibly even diachronically—related. I revisit this after the next section.

6. Tense with Duration Adverbials

I then tried to ascertain whether tense and aspect had anything to say about duration. Note that morphosyntactic tense in Portuguese is a very rich system, so I am not talking about past, present, and future here, but about distinguishing morphosyntactic tenses (which also encode aspect).

I started by counting the tenses in the smaller amount of material, the interviews.

Table 7 shows the number of times the (most frequent) tenses were present in the corpus, and the number of times they occurred with

por and

durante.

The picture was clear: almost only clauses in Perfeito had duration expressed (with

por or

durante). Many of the cases of

por seemed to imply a short period (Example (6) (a)) and/or seemed to be negatively conceived by the speaker (Example (6) (b)):

| (6) | (a) Depois porque me faltavam quatro anos para a jubilação, e o que é que eu ia lá fazer por quatro anos? (‘what would I do there for four years?’). |

| (b) E nessas missões o senhor ficava longe de casa por dois anos seguidos? (‘were you far from home for two years in a row?’). |

But in the Brazilian interviews, some cases with

por seemed merely a neutral way of stating duration:

| (7) | trabalhei em uma loja em Porto Alegre, e depois na Praia dos Ingleses, por cinco meses. (‘I worked in a shop…for five months’). |

I then turned to the literature to see whether there were significant differences in the way the duration adverbials were employed, and I ended up closely reading all the examples; therefore, I corrected the initial numbers. Several cases of

por that were not temporal adverbials were discarded, examples of which I present here:

| (8) | (a) Apesar de endurecido por quarenta anos de caça e carnificinas, eu próprio sentia um nó na garganta, e creio que me fiz pálido. (hardened by forty years of hunt and carnificine). |

| (b) Tinha eu chegado do continente, prostrado por duas horas de canal da Mancha…(‘tired by two and a half hours of the Channel’). |

| (c) E a população muçulmana, enfurecida por nove horas de bombardeamento, sem polícia para a conter, (‘infuriated by nine hours of bombing’). |

| (d) da Comenda que mereci, por dezesseis anos de serviço na guerra. (‘…I deserved for 16 years of service in war’). |

| (e) Era o conselheiro Andrade, conhecido por quarenta anos de ceias consecutivas, desde o remoto Rocher de Cancale até os desvairamentos dos atuais. (‘known for 40 years of consecutive dinners’). |

So,

Table 8 shows the actual distributions of these temporal adverbials in the literature by tense:

As for the CHAVE collection, the amount of data required a selection, so I just annotated 200 cases (100 per variety) randomly selected with Perfeito. The results are presented in

Table 9.

These data seem to agree with Móia’s claim that durante is clearly preferred in European Portuguese, whereas Brazilians may have a preference for por.

7. More Specific Questions about Duration

For each case, I annotated whether it was a clearly negative or clearly positive action or situation and whether I regarded it as long or short. In cases where I did not feel it conveyed any such connotation (long or short), I did not add any annotations.

I also annotated the (in this case, quite clear) cases of planned duration. Finally, I also identified the cases where a negative sentence with

por um momento/instante was an emphatic way to convey the negation through a minimiser, as in the following examples:

10| (9) | Mas o Tomé, servo cumpridor das ordens que lhe davam, nem por um momento hesitou em dirigir para ali os seus passos. (‘not for a moment he hesitated’). |

| Devo dizer também que, vendo-a, ouvindo-a, eu não supus nem por um momento que no homicídio de que ela se acusava pudesse haver o que se chama verdadeiramente um crime, isto é, uma intenção infame ou perversa. (‘I did not suppose for a moment that…’. |

| José, que tudo ouviu, não se intimidou por um momento. (‘did not cower for a moment’). |

First, I present the numbers obtained in

Table 10, which correspond to the most frequent tenses in Literateca, amounting to 937 sentences.

From these numbers, I concluded that a negative attitude about the event does not play any role, or at least, that the data cannot support this hypothesis. In fact, the data additionally showed that to make such decisions based only on the particular sentence is quite hard, as the three next examples try to illustrate:

| (10) | Depois, fujam, abandonem o lugar, a capela, tudo, porque a seca vai continuar ainda por dois anos (‘run away, leave the place, the chapel, everything, because the drought is going to go on for two years still’). |

| Ia ficar sozinha por um mês, o amigo era chamado a S. Paulo para um negócio urgente. (‘She would be alone for one month’). |

| As memórias desses tempos não nos dizem quem quebrou as pazes juradas: só sabemos que a luta interrompida por dois anos começou de novo. (‘the fight interrupted for two years’). |

While the first is probably consensual—it is not good for a drought to continue, and the sentence even exhorts people to flee—in order to ascertain whether it would be good (or negative or neutral) for the feminine character to be alone, one would have to know more about the plot. And although with modern eyes, to fight again would be considered negative, my impression is that in the text in question, the fight is considered good and, therefore, the interruption bad. So, regardless of my own interpretation of badness, what I should annotate is what the author meant. But anyway, I think we can safely conclude that this category plays no role in the choice between

durante and

por.

On the other hand, I believe it is fair to claim that

durante is clearly preferred when the speaker is conveying long duration (317 vs. 79 cases), and

por is clearly preferred when the speaker is conveying short or temporary periods (90 vs. 23 cases). I am aware that I was not able to distinguish between short and temporary in my subjective annotation.

11But, after considering all these short/temporary cases, a large proportion of which use

um momento, it was clear that this is a key ingredient of fictional narratives in Portuguese. It is often associated with changes in the disposition or thoughts of the character in question,

12 which are obviously out of place in factual journalese. And this may explain why

por is much more common in fiction, independent of the epoch.

Given that both

Rodrigues (

1994) and

Móia and Alves (

2013) cited planned duration as a clear case of

por adverbials in Portuguese, and

Rodrigues (

1994, p. 505) even explicitly said that

durante is not allowed in such contexts,

13 I expected that

por would be categorical with planned duration. However, there were enough instances in the literature of planned duration with

durante to show that it is—or was—just a preference or that “planned” is not the whole story.

Some examples of planned duration with

durante are as follows:

| (11) | (a) para aí edificarem o teatro do Bairro Alto, pagando anualmente 240000, durante catorze anos, renováveis, salvo se o proprietário quisesse continuar a reedificação do palácio. (‘in order to build the theatre, paying annually X for 14 years’). |

| (b) Àqueles que seguissem Sancho nas incursões contra os sarracenos ou formassem parte do seu exército concedia ele, papa, durante quatro anos, as mesmas indulgências que os concílios haviam decretado para os que se votavam ás longínquas expedições de ultramar (‘he, the Pope, would issue for four years the same indulgences…’. |

| (c) Liberato e Frederico deviam demorar-se apenas quatro meses com seus pais, seguindo depois para a América do Norte, onde durante dois anos estudariam com observação solícita os sistemas, processos, […] (L. and F. should stay only 4 months with their parents, and then go to North America, where for two years they would study…’). |

| (d) Eu também vou em breve atirar fora a minha pena e as minhas declamações, para me fazer durante três dias espontâneo e lógico (‘in order to become spontaneous and logical for three days’). |

As for the differences between having

durante or no preposition, I tried to rephrase a considerable amount of

durante adverbials

14 to ascertain whether this was possible at all, and if yes, what the difference would be, if any.

Interestingly, I was able to find 42 cases (out of 135) where

durante was not removable, as shown in the following examples:

| (12) | (a) Gillooly, que foi preso na semana passada e é considerado o «cérebro» da agressão a Kerrigan, foi interrogado durante seis horas pelo FBI. (‘was questioned for the duration of six hours’). |

| (b) Passada a fronteira, não pararam durante duas semanas e mantiveram-se sempre à frente dos indonésios. (‘did not stop for two weeks’). |

| (c) Nós conseguimos ter um escritório da ONG Vitae Civilis somente em 93, na época recebendo um apoio de U$ 2.500, nem sei quanto valeria hoje, mas com esse dinheiro a gente alugou uma sala durante um ano e ainda arrumou uma funcionária (‘we rent a room for one year’). |

| (d) No silêncio e na solidão dos claustros escapou durante seis séculos o ténue pergaminho que nos conserva a memória de Afonso Mendes Sarracines (‘escaped from destruction for six centuries the tenuous parchment’). |

In all cases,

durante specifies that one is talking about a consecutive period, not a simple (possibly discontinuous) duration. In addition, in (c), the alternative expression,

um ano, would mean something like once during a given year.

For the other cases, the large majority of durante adverbials convey a long duration compared to those with the bare adverbial.

8. Convergence and Divergence of Portuguese

Until now, we have been looking at different genres produced at different times, given the available corpora, namely contemporary Portuguese for CHAVE and Museu da Pessoa, and mainly the nineteenth century for the literature. Although I have argued that the differences are mainly due to genre, it is definitely an advantage to have another resource that may help us check whether time is also an important feature here.

The use of ConDiv, which was precisely designed to address the study of the convergence and divergence of the varieties from Brazil and Portugal, may help us here. In

Table 11, we show the numbers for the three different decades, per variety, as well as the ratio between

durante and

por.

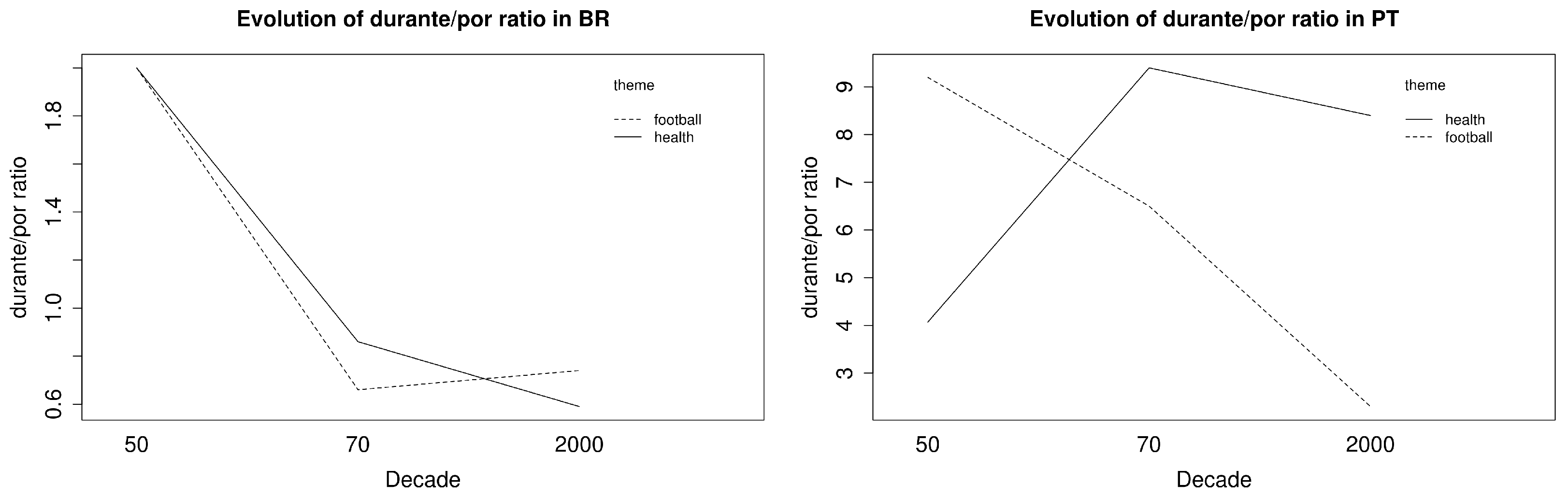

Although these numbers are probably not enough to come to a definite conclusion, it is interesting to observe that the use of por consistently increases in Brazilian Portuguese, whereas the predominance of durante in European Portuguese seems to diminish.

In order to check whether this is an artefact of different distributions per theme, I repeated the queries separately per domain, as presented in

Table 12, respectively, for football, fashion and health.

We can see no significant differences between the themes, except that in the football domain, the Portuguese practice in the 2000s seems to converge toward the Brazilian style, with

por increasingly more frequent. However, this cannot be seen in the health domain (see also

Figure 2).

9. Conclusions

This paper reported on a corpus study for the purpose of understanding the use of por and durante adverbials in Portuguese, both intervarietally and intergenre, as well as over three different decades spanning the 20th and 21st centuries.

This study was more than a simple comparison of counts since a considerable number of examples were closely read and annotated for categories such as “planned activity”, “contextually long duration”, “temporary/short duration”, “negatively seen”, and “emphatic negation”.

The main conclusions were that genre matters, and the marked preference for por in literary texts is related to the frequency of occurrence of events with short durations in fictional narratives. Planned activities favour the use of por in both varieties, but it is also possible to use durante. The use of durante compared to the use of no preposition, especially in fiction, seems to convey a long duration. It displays the attitude of the writer towards the period, in addition to expressing its length. Por, in fiction, seems to convey temporariness and short duration when not describing planned activities. In informative texts, where the attitude of the writer is less frequently expressed, there seems to be a marked preference for durante in texts from Portugal, and a more liberal use of por in texts from Brazil, which increased around the 1960s, if we take football- and health-related newspaper texts as good indicators of the language as a whole. In negative contexts, por um instante or por um momento simply emphasises negation. Duration adverbials with either preposition are mainly expressed using verbs in Perfeito, that is, indicating events that are completely in the past.

It is left for further research to investigate the possible dependence of the duration adverbials on (a) aspectual class, and (b) the existence of iterated readings. This would imply annotation of these two pieces of information, which has not yet been done.

Also, a more fine-grained study of literary texts might uncover (a) different stylistic preferences of different authors, and (b) a chronological map of the

durante–por variation on the two sides of the Atlantic. The literary corpus itself includes more than just fiction, as discussed in

Freitas and Santos (

2023), so it is possible to perform a more fine-grained analysis with such material.

All the data compiled for this paper, along with the annotations, are available for inspection

15 so that other researchers can validate and/or improve on them.