1. Introduction

Relative clauses have been extensively studied from a wide range of perspectives, including typology and variation. Portuguese is no exception, with research focusing mostly on the European and Brazilian varieties (e.g.,

Alexandre 2000;

Brito 1991;

Kato 1993;

Kenedy 2007;

Peres and Móia 1995;

Tarallo 1985;

Veloso 2013), whereas relativization in African varieties of Portuguese (AVP) has been the object of a relatively limited number of studies (e.g.,

Alexandre et al. 2011a,

2011b;

Alexandre and Lopes 2022;

Brito 2001,

2002;

Chimbutane 1996;

Gonçalves 1996). The research agenda on relativization in Portuguese features topics such as non-standard relativization mechanisms, in particular, P-chopping and resumption, and the nature of the relativizer (pronoun or complementizer).

In this paper we aim to investigate variation in the formation of the relative clause of spatial location in three urban African varieties of Portuguese (AVP)—Luanda/Angola (AP), Maputo/Mozambique (MOP), and São Tomé/São Tomé and Príncipe (STP). These three varieties are particularly interesting because they are undergoing a process of nativization in a context of language contact and shift toward Portuguese. Based on spoken, contemporary corpus data, we seek to expand the knowledge on these varieties and to contribute to the understudied topic of locative relativization in Portuguese. We are particularly interested in understanding the distribution of the two main relative morphemes heading locative relative clauses, onde ‘where’ and que ‘that’, and whether and how the use of these two forms is constrained.

One hypothesis is that language contact plays a role since this factor has been argued to be the driving force behind linguistic features of AVP. The fact that the three AVP are historically in contact with different language typologies, including in the domain of locative relativization, provides an opportunity to assess the role of language contact from a cross-comparative perspective. In addition, we explore a more language-internal hypothesis, aiming to determine whether there are specific syntactic and/or semantic variables that motivate the selection of one or the other relativizer. We therefore selected and analyzed variables which had either been previously discussed for the domain of relativization or showing potential to correlate with the use of the two different relativizers. Addressing these hypotheses will also give insight into the language variation that characterizes the three varieties at stake, internally and among each other.

The paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 briefly reviews work on locative relativization in Portuguese;

Section 3 provides a brief background on the AVP in question and lays out the methodology used;

Section 4 focuses on the properties of locative relativization in the main contact languages and what they predict with respect to the AVP if contact plays a role;

Section 5 discusses, on the one hand, syntactic mechanisms involved in locative relativization, including the distinction between head nouns with an argument and an adjunct status, and, on the other hand, semantic variables that were tested in order to determine whether there is a (statistical) correlation between the semantic nature of the head noun and the selection of the main locative relativizers

onde and

que, in particular the semantic role of the head noun, the type of location it describes, and its definiteness;

Section 6 discusses the results; and

Section 7 concludes the paper.

2. Locative Relativization in Portuguese

Locative relative clauses are a type of relative clause that provide essential information about the location or place associated with a noun in a sentence. There is considerable variation in relativization across different languages (see, for example,

Comrie 1981;

Vries 2002 on relative clauses in general). For example, the structure and use of relative clauses can vary cross-linguistically in terms of word order and the syntactic mechanisms used; the choice of relativizers, i.e., different languages may have different relative pronouns or other lexical material to introduce relative clauses, such as conjunctions or complementizers and classifiers, the type of agreement between the head noun and the relativizer, and the semantic features of the head noun and the relative clause (e.g.,

Wiechmann 2015).

Portuguese exhibits postnominal relative clauses that are standardly introduced by invariable morpheme

que or by morphemes showing Case or number features, such as

quem ‘whom’ and

qual/quais ‘which’, as illustrated, respectively, in (1a–c). The latter two examples further show that Portuguese exhibits pied-piping (i.e., a relative pronoun preceded by prepositions) in cases of PP-relativization.

| (1) | a. | Perdi | o | livro | que | me | deste. | | | |

| | | I.lost | the | book | REL | me | you.gave | | | |

| | | ‘I lost the book you gave me.’ | | | |

| | b. | Não | conhecia | a | pessoa | a | quem | dei | o | livro. |

| | | NEG | I.knew | the | person | to | REL | I.gave | the | book |

| | | ‘I didn’t know the person to whom I gave the book.’ |

| | c. | Vi | o | filme | do | qual | toda | a | gente | fala. |

| | | I.saw | the | movie | of.the | REL | every | the | people | talks |

| | | ‘I watched the movie everybody talks about.’ |

Languages often display specialized relative markers that encode location, such as the English

where. In Portuguese the standard locative relativizer is

onde, ‘where’, but other forms are also used, namely the invariable morpheme

que, ‘that’, preceded by a pied-piped preposition, which is usually

em, ‘in’, as in (2), and by strategies involving the variable relativizer

o(a) qual/os(as) quais ‘which’, which exhibits gender and number features, illustrated in (3), and whose determiner contracts with prepositions used for locative purposes.

| (2) | A | casa | onde/em que | eu | moro | é | bonita. | | | |

| | the | house | REL/in REL | I | live | is | beautiful | | | |

| | ‘The house where/in which I live is beautiful.’ |

| (3) | As | esplanadas | em que/nas quais | gosto | de | ler | um | livro |

| | the | terraces | in REL/in.the which | I.like | to | read | a | book |

| | estão | viradas | a | poente. | |

| | are | turned | the | west | |

| | ‘The terraces where/in which I like to read a book are facing west.’ |

Locative relativization in Portuguese has generally only deserved brief mention in the extensive literature on other types and properties of relativization in this language. It is commonly stated that the relative morpheme

onde has a locative or place feature (

Alexandre 2000;

Brito 1991;

Corrêa 2001;

Móia 1992;

Veloso 2013) and that the head noun in these constructions does not refer exclusively to a dimension of physical space (

Peres and Móia 1995, p. 305), as in (4) below. In Caboverdean Portuguese, a variety not analyzed in this paper, the non-standard use of

onde in Portuguese can also carry additional (underspecified) features related to tense and event/situation (

Alexandre and Lopes 2022), as illustrated in (5) and (6).

| (4) | A parte do discurso onde a Ana foi mais convincente foi aquela em que enumerou as promessas não cumpridas do Governo. (Peres and Móia 1995, p. 305) |

| | ‘The part of the speech in which Ana was most convincing was the one in which she listed the government’s unfulfilled promises.’ |

| (5) | “Seria bom que a Expo ficasse na História como um momento onde a cultura e a ciência portuguesas se encontrassem com o futuro”, disse. (Alexandre and Lopes 2022, p. 4) |

| | ‘“It would be nice if the Expo was remembered as a moment when Portuguese culture and science met the future”, he said.’ |

| (6) | Nessa altura, os agentes da Judiciária de Tomar são chamados a actuar, num caso onde tinham já algum trabalho em marcha. (Alexandre and Lopes 2022, p. 4) |

| | ‘At that point, the officers of the Tomar Judicial Police were called into action, in a case on which they already had some work underway.’ |

Despite the widespread use of

onde, work on relativization in Portuguese has shown that there is a tendency to use the relativizer

que, especially in non-standard mechanisms such as P-chopping and resumption, to the detriment of strategies that privilege relativizers with agreement features, such as

quem or

qual/quais (e.g.,

Elisabeth and Rinke 2017;

Alexandre 2000;

Alexandre et al. 2011a;

Peres and Móia 1995;

Tarallo 1985). It has been argued that, due to its lack of phi-features,

que is being reanalyzed as a complementizer including in EP and AVP (e.g.,

Alexandre 2000;

Alexandre et al. 2011a).

1 While it has been established that

onde is increasingly used outside of locative relative structures, a fact that has been diachronically reported for other languages (e.g.,

Ballarè and Inglese 2022)

2, the role of

que in locative relativization has not been adequately assessed, i.e., is it the case that the general tendency to favor an invariable relativizer reflects or brings about changes in the domain of locative relativization?

The puzzle about Portuguese locative relative clauses in general is therefore that onde, ‘where’, extends its functions to semantic roles different from [+locative], while que, ‘that’, enters the domain of locative relative clauses, in particular in non-standard relativization strategies. With this study we attempt to shed new light on the distribution of these two relative markers in contemporary, spoken AVP, focusing on the role of putative syntactic and semantic variables and language contact.

3. Background and Methodology

The more widespread use of Portuguese in the former Portuguese colonies in Africa is mostly a 20th century phenomenon, related to the effective occupation, exploitation, and administration of these spaces (e.g.,

Gonçalves 2010,

2013;

Hagemeijer 2016). During the colonial period, it was mainly the language of a (privileged) minority and most typically an L2 for those without roots in the metropole. After the independences in the 1970s, when Portuguese became the exclusive official language of the new countries supported by the democratization of education in this language, increased social mobility, as well as other aspects of modernization such as exposure to audiovisual means, Portuguese became not only more widespread, but also increasingly nativized in Angola, Mozambique, and São Tomé and Príncipe. The boom of Portuguese is underscored by data from the national censuses that were held after the independences (

Hagemeijer 2016, p. 46). According to latest national censuses, Portuguese is spoken by 98.4% of the population of São Tomé and Príncipe (

INE 2013); 71.15% of the Angolan population speaks Portuguese at home, which reaches 85% in urban areas (

INE 2016); and Portuguese is spoken by 47.4% of the Mozambican population, which includes 16.6% of L1 speakers, again, with strong prevalence in urban areas (77%) (

INE 2019). Although the censuses in Angola and São Tomé and Príncipe do not distinguish between L1 and L2 speakers of Portuguese and the other languages, the combined percentages of the number of speakers of the other languages show the role of nativization. In the latest census in São Tomé and Príncipe (

INE 2013), for example, only slightly over 50% of the speakers were indicated to be speakers of one of the creole languages (

Hagemeijer 2018, p. 178), which also confirms that there is a growing body of Portuguese monolinguals.

Since Portuguese is (historically) an L2, language contact has been argued to play a prominent role in the shaping of AVP, in the sense that features (and lexicon) from the L1 languages have been transferred to L2 varieties of Portuguese (e.g.,

Gonçalves 2010;

Inverno 2011;

Mingas 2000). While the data do show (some) evidence in support of language contact, quantitative-based research has shown that AVP exhibit substantial intra and interspeaker variation (e.g.,

Gonçalves and Chimbutane 2004;

Gonçalves et al. 2022), which also includes substantial convergence with EP, the target language, as well as innovative patterns with respect to both EP and the relevant contact languages (e.g., discussion in

Gonçalves et al. 2022;

Hagemeijer et al. 2022a). The growing number of L2 and especially L1 speakers and the increased role of schooling may actually be taken as forces that increasingly counter the putative role of language contact.

With respect to the data, this case study is based on spoken, urban corpora of AP, MOP, and STP that were prepared within the project

Possession and Location: microvariation in African varieties of Portuguese (PALMA). The semi-structured interviews that form the corpora were collected in the capitals Maputo, Luanda, and São Tomé between 2008 and 2020, and were as much as possible balanced according to level of education, age, and gender (cf.

Hagemeijer et al. 2022b). Portuguese is the L1 or primary language of most of the informants, especially in the case of urban AP and STP, confirming the ongoing tendency toward nativization of Portuguese and its role as a lingua franca.

Table 1 summarizes the basic information of the corpora.

For the purpose of this paper, we proceeded to extract all the contexts with the relative markers

onde, ‘where’,

que, ‘which/that’, and

qual/quais, ‘which’, from the searchable CQPweb platform (

Hardie 2012) hosting the three corpora, and then manually excluded all the contexts which do not concern relative clauses of spatial location, as well as unclear contexts.

3 In doing so, we identified a total of 645 relevant contexts: 217 for AP; 271 for MOP; and 157 for STP, as shown in

Figure 1 below, which includes the numbers and percentages per variety.

Locative relative clauses formed with

qual/quais are practically absent (AP and MOP) or inexistent (STP) in our data, which is in line with tendencies observed in other work on relativization in European Portuguese (e.g.,

Rinke and Aßmann 2017;

Alexandre et al. 2011a;

Arim et al. 2004;

Selas 2014). We therefore excluded a total of 16 occurrences of

qual/quais from further analysis, focusing exclusively on data involving relativizer

onde, which is dominant in the three AVP (68–75%), and

que, which is also common (21–33%). This yields a final total of 629 contexts: 212 for AP; 260 for MOP; and 157 for STP.

We then proceeded to manually annotate the remaining extracted contexts with respect to the follow syntactic and semantic variables

4, which we briefly address further below:

The syntactic relativization mechanism;

The argument vs. adjunct status of the antecedent head noun;

The semantic role of the antecedent head noun (Locative vs. Goal/Source);

The type of location expressed by the antecedent head noun: physical (container or area) vs. non-physical;

Definiteness of the antecedent: [+definite] or [−definite].

A large amount of crosslinguistic work has been produced on the syntactic mechanisms of relativization (e.g.,

Comrie 1981). Hence, we aim to discuss to what extent the relativization mechanisms identified in previous work on Portuguese in general and AVP in particular occur in locative relative constructions, namely (i) pied-piping, (ii) P-chopping, (iii) resumption, and (iv) defective copying (

Alexandre 2012), how they correlate with relative markers

que and

onde, and whether there is evidence of contact-induced effects. In the domain of syntax, we will also assess whether the adjunct or argument status of the head noun leads to any prediction with respect to the use of

onde and

que.

We will further analyze the data considering semantic properties of the antecedent of the locative relatives to test whether semantic variables play a role in the selection of relativizers

onde/que. The semantic features that will be assessed are (i) the semantic role of the head noun, distinguishing between Locatives, on the one hand, and Goal/Source on the other; (ii) the type of location expressed by the antecedent, i.e., physical location or non-physical location and, within the former type, well-delimited head nominals (‘containers’) and those lacking sharp boundaries (‘areas’), a distinction adapted from work by

Nikitina (

2008) on spatial Goals; and, finally, we investigate whether the definiteness status of the head nominal is a predictor for the use of

onde/que.

Assuming that

onde has a basic locative feature (

Peres and Móia 1995;

Veloso 2013), whereas

que is unspecified, sharing properties with complementizers (e.g.,

Alexandre 2000;

Alexandre et al. 2011a;

Tarallo 1985), we will discuss whether this difference is reflected in the form of the relativizer that accompanies the head noun. In particular, we will assess whether

onde is more prone to occur with Locatives, physical locations, and definite locations, and

que in other contexts. Despite crosslinguistic research on the semantic features of the antecedent and/or the properties of the relative clause (e.g.,

Wiechmann 2015), these semantic variables have not been explored for locative relativization in Portuguese.

The validity of the syntactic and semantic variables will be subjected to statistical analysis through the online statistical software Jamovi (

The Jamovi Project 2023).

We do not distinguish between restrictive (the bulk of our data set) and appositive relative clauses, because we do not consider this distinction critical to our discussion.

Finally, standard European Portuguese (EP), as the target grammar for these varieties, is used for comparative purposes.

4. Language Contact

Although the domain of relativization has not been thoroughly investigated, research focusing on its syntactic properties, in particular

Brito (

2001,

2002) on genitive relatives in MOP and

Alexandre et al. (

2011a) on PP relativization in Caboverdean and Santomean Portuguese, has argued against a major role for language contact. For these two types of relativization, this assessment follows from the fact that the corresponding syntactic properties of the main contact languages, which differ typologically from Portuguese, occurred only marginally in these AVP.

Considering the importance that is traditionally assigned to language contact in the literature, this section aims to briefly address the main properties of locative relativization in the contact languages that are typically linked to the urban varieties under discussion, namely the Bantu languages Mbundu

5 for AP and Changana/Ronga for MOP, and the creole language Santome for STP.

4.1. Mbundu

Many Bantu languages still exhibit the three specific locative markers within the noun class system that have been reconstructed for proto-Bantu (class 16 *

pà-, 17 *

kù-, and 18 *

mù-), each with specific semantic functions (e.g.,

Zeller, forthcoming). This is the case of Mbundu, where locative relatives are expressed by an initial prefix in the verbal complex that is sensitive to the semantic role of the head noun: with Goal/Source antecedents, prefix

ku- occurs, whereas Locatives occur with stative

mu-, as shown in (7) and (8), respectively

6.

| (7) | Inzo | ku-nga-ya | ya-kala | mu | Luwanda. |

| | 5.house | LOC17-1SG.TAM-go | 5.TAM-be | LOC18 | Luanda |

| | ‘The house where I go to is in Luanda.’ (elicited with Afonso Miguel) |

| (8) | Inzo | mu-nga-tungila | ya-kala | mu | Luwanda. |

| | 5.house | LOC18-1SG.TAM-live | 5.TAM-be | LOC18 | Luanda |

| | ‘The house where I live is in Luanda.’ (elicited with Afonso Miguel) |

Differently from Portuguese, Mbundu thus uses a mechanism that is primarily morphological to yield a locative relative interpretation. Therefore, if language contact is a relevant factor for locative relativization in AP, the prediction is that the semantics of this morphologically encoded Goal/Source vs. Locative contrast could carry over to AP.

4.2. Changana/Ronga

Differently from Mbundu, Bantu languages of the Tsonga cluster, and Changana and Ronga in particular, only exhibit traces of the proto-Bantu tripartite locative noun class system (the morpheme

ka- in the examples below). The locative relativization strategy in this cluster consists of the use of class-agreeing relativizers identical to demonstratives

7, the use of verbal prefixes or suffixes that show agreement with tense-marking (-

taka- and -

nga- in the examples below), and the use of resumption, which is expressed by the locative + pronoun complex

ka-xone and

ka-drone in (9) and (10) (e.g.,

Macaba 1996;

Vondrasek 1999;

Chimbutane 2002;

Zeller, forthcoming).

| (9) | Axi-tramu | lexi | u-taka-trama | ka-xone. |

| | 7-chair | REL7 | 2SG-REL.FUT-sit | LOC-7PRON |

| | ‘The chair on which you will sit.’ (lit. ‘The chair that you will sit on it.’) |

| | (Ronga, adapted from Vondrasek 1999, p. 134) |

| (10) | Adoropa | ledri | ni-nga-kulela | ka-drone. |

| | 5.vila | REL5 | 1SG-REL.PST-crescer | LOC.5PRON |

| | ‘The town in which I grew up.’ (Lit. ‘The town that I grew up in it.’) |

| | (Ronga, adapted from Vondrasek 1999, p. 134) |

Differently from Mbundu, the examples show that Changana/Tsonga exhibits syntactic relativizers, which manifest themselves in different forms according to the noun class the head noun belongs to

8. (Mozambican) Portuguese of course lacks a noun class system and does not present special relative tenses. The use of resumptive pronouns, on the other hand, has been attested in all varieties of Portuguese and has been discussed for MOP in

Chimbutane (

1996), who analyzes instances of Direct Object and (mostly non-locative) Oblique relatives in this variety from the perspective of Universal Grammar, without discussing the hypothesis of language contact. If this factor plays a role, we expect it to manifest itself in the form of resumption, which is arguably the only feature of locative relativization in Changana/Ronga available for transfer to MOP.

4.3. Santome

In Santome (Forro, Sãotomense), the main creole language spoken on the island of São Tomé, relative clauses in general are headed by the relativizer

ku. In locative relatives with locative adjuncts and stative verbs of locative use, such as

vivê ‘to live’,

ta ‘to live, to be at’, and

sa ‘to be (at)’, as shown in (11) and (12), this form can be accompanied by the defective copy

nê9. Defective copying, i.e., an invariable third-person singular form

ê, which lacks number agreement with the head noun (which is particularly visible with plural head nouns), corresponds to the canonical PP-relativization mechanism in Santome (e.g.,

Alexandre and Hagemeijer 2002,

2013;

Alexandre et al. 2011a). The following examples were extracted from a Santome corpus (

Hagemeijer et al. 2014).

| (11) | Kabla | sêbê | xitu | ku | kabla | ka | kume | nê. (Santome) | |

| | goat | know | place | REL | goat | HAB | eat | in-3SG | |

| | ‘Goats know where goats eat.’ |

| | (Lit. ‘Goats know the place that goats eat in it) |

| (12) | ke | ku | êlê | tan | ku | anzu | se | saka | vivê | nê. (Santome) |

| | house | REL | 3SG | only | with | child | DEM | PROG | live | in-3SG |

| | ‘the house where only he and his child are living in.’ (Lit. ‘The house that only he and his child are living in it.’) |

Verbs of directed movement, on the other hand, introduce Goal arguments directly, as shown in (13a) by the sequence

ba ke, ‘go home’. Therefore, relativization of Goal arguments of these verbs shows the same properties as regular Direct Objects (leaving a gap) and does not trigger a defective copy, as shown in (13b). In the specific case of ‘to go’, there are two allomorphs,

ba and

be, whose distribution is determined by syntactic properties (

Hagemeijer 2004).

| (13) | a. | Mina | ba | ke | ka | sola | potopoto. (Santome). |

| | | child | go | home | TAM | cry | IDEOPHONE |

| | | ‘The child went home crying cats and dogs.’ |

| | b. | kwa | ku | n | mêsê | sa | sêbê | xitu | ku | bô | be (Santome) |

| | | thing | REL | 1SG | want | be | know | place | REL | 2SG | go |

| | | ‘what I want to know is where you went’ |

If Santome plays a role in the patterns observed in STP, the prediction is that this variety will exhibit defective copying as a relevant strategy and possibly also a tendency toward the use of que, since the Santome counterpart of Portuguese onde (andji or its short form an) is only used in locative interrogatives. Moreover, since directed motion verbs in Santome are transitive, under a contact-induced hypothesis we might also expect cases of (apparent) P-chopping when Goal arguments are transitivized.

4.4. Summary

This brief incursion in the mechanisms of locative relativization in the languages that have been historically in contact with AP, MOP, and STP shows substantial differences among them, not only between the Bantu languages and Santome, whose typologies are considerably different, but also among a western Bantu language (Mbundu) and southeastern Changana/Ronga. Some of the features of locative relatives in these contact languages, such as special tenses or specific locative morphology, are of course not available in Portuguese and therefore not good candidates for transfer; but others, especially those in the syntactic domain, such as resumption and defective copying or the use of an exclusive relative marker, are within reach of the typology of Portuguese and therefore potential candidates for transfer. Since the contact languages display different mechanisms and features in locative relativization, the role of language contact, if relevant, would tendentially lead to different outcomes in each of the AVP in this study.

5. Syntactic and Semantic Variables in AVP Data

In the subsections below, we discuss the syntactic mechanisms of relativization in the AVP, the syntactic relation between the head noun and the relative clause (argument or adjunct), as well as several semantic features, namely the semantic role of the head noun (Locative, Goal, Source) with respect to the predication, the type of location expressed by the head noun (physical, i.e., area or container, or non-physical), and definiteness of the head noun. The distribution of these variables is crossed with the use of onde/que and tested for statistical significance.

5.1. Syntactic Mechanisms of Locative Relativization

Pied-piping in locative relatives in AVP involves the relativizers

onde and

que (14a,b), which can be preceded by a preposition that is pied-piped from inside the relative clause. Most commonly, this preposition is

em, ‘in’ (14b), in which case it is accompanied by relative

que, but other combinations also occur, for example

a, ‘to(wards)’, and

de, ‘from’, for Goals and Sources or

por, ‘by, through’ (e.g.,

por onde). We treat locative relative clauses introduced by

onde as instances of intrinsic pied-piping.

| (14) | a. | fui | para | uma | oficina de marcenaria | onde | estive | durante | sete | anos (STP) |

| | | I.went | to | a | woodwork studio | REL | I.was | for | seven | years |

| | | ‘I went to a woodwork studio where I stayed for seven years’ |

| | b. | é | difícil | arranjar | emprego | no | país | em | que | nós | nos | encontramos |

| | | it.is | hard | to.find | job | in.the | country | in | REL | we | REFL | are (AP) |

| | | ‘it is hard to find a job in the country where we are’ |

In the cases of locative relatives, P-chopping, i.e., the deletion of argumental and non-argumental prepositions, primarily involves the deletion of the locative preposition

em, ‘in’, with relativizer

que, as illustrated in (15). However, the absence of other prepositions is also attested in the data, as shown in (16), in particular with

que (16a,b), but also with

onde (16c,d)

10.

| (15) | a. | e | é | uma | província | que | fala-se | muito | quimbundo (AP) |

| | | and | it.is | a | province | REL | speak.IMP | a lot of | Mbundu |

| | | ‘and it is a province where they speak a lot of Mbundu’ |

| | b. | é | como | São Tomé | é | um | país | que | chove | muito (STP) |

| | | and | since | São Tomé | is | a | country | REL | rains | a lot |

| | | ‘and since São Tomé is a country where it rains a lot’ |

| | c. | há | sítios | que | não | havia | escolas (MOP) |

| | | there.are | places | REL | NEG | were | schools |

| | | ‘there are places that didn’t have schools’ |

| (16) | a. | há | sítios | que | carro | mesmo | não | vais (AP) |

| | | there.are | places | REL | car | even | NEG | you.go |

| | | ‘there are places where you don’t even go by car’ |

| | b. | uma | região | ali | do | norte | também | que | eu | nunca | fui. (STP) |

| | | a | region | there | of.the | north | also | REL | I | never | went |

| | | ‘a region in the north where I never went to.’ |

| | c. | Para | os | ovimbundos | onde | eu | sou | originário (AP) |

| | | to | the | Ovimbundu people | Ø REL | I | am | originating |

| | | ‘To the Ovimbundu people where I belong to.’ |

| | d. | um | serviço | alargado | de | agenda | pública | Ø onde | os | ouvintes | trazem |

| | | a | service | extended | of | agenda | public | REL | the | listeners | bring |

| | | os | seus | avisos | ou | anúncios (STP) |

| | | the | their | notifications | or | announcements |

| | | ‘an extended service of the public agenda to which the listeners bring their notifications or announcements’ |

Locative resumption entails the semantic recovery of the head noun by a deictic, in particular

lá, ‘there’, as in (17a–c) but less commonly also a (repeated) full-fledged NP, as in (17d). Resumption is observed with both the relative marker

que and

onde, which also shows that different mechanisms, such as pied-piping and resumption (17c) or chopping and resumption (17d), may cooccur

11.

| (17) | a. | volto | para | minha | província | que | já | não | vivo | lá | há | quinze | anos (AP) |

| | | I.return | to | my | province | REL | already | NEG | I.live | there | for | fifteen | years |

| | | ‘I return to my province where I haven’t lived for fifteen years’ |

| | b. | assemelha-se | a | uma | indústria | que | eu | estava | lá (MOP) |

| | | it.resembles-REFL | to | a | industry | REL | I | was | there |

| | | ‘it resembles an industry where I used to work’ |

| | c. | uma | zona | famosa | onde | dizem | que | tem | lá | algumas | pessoas (STP) |

| | | a | zone | famous | REL | they.say | that | has | there | some | people |

| | | ‘a famous region where they say some people live’ |

| | d. | é | um | lugar | que | hoje | ou | amanhã | pode | sair | daquele | lugar (AP) |

| | | it.is | a | place | REL | today | or | tomorrow | can | leave | from.that | place |

| | | ‘it’s a place which he may leave today or tomorrow’ |

Finally, locative defective copying consists of a stranded preposition that is accompanied by a third-person singular pronoun which lacks gender and number agreement features with the head noun, as illustrated in (18).

| (18) | própria | escola | que | estudei | nele (STP) |

| | self | school | REL | I.studied | in-3SG |

| | ‘the very school I studied in’ (lit. the very school I studied in it) |

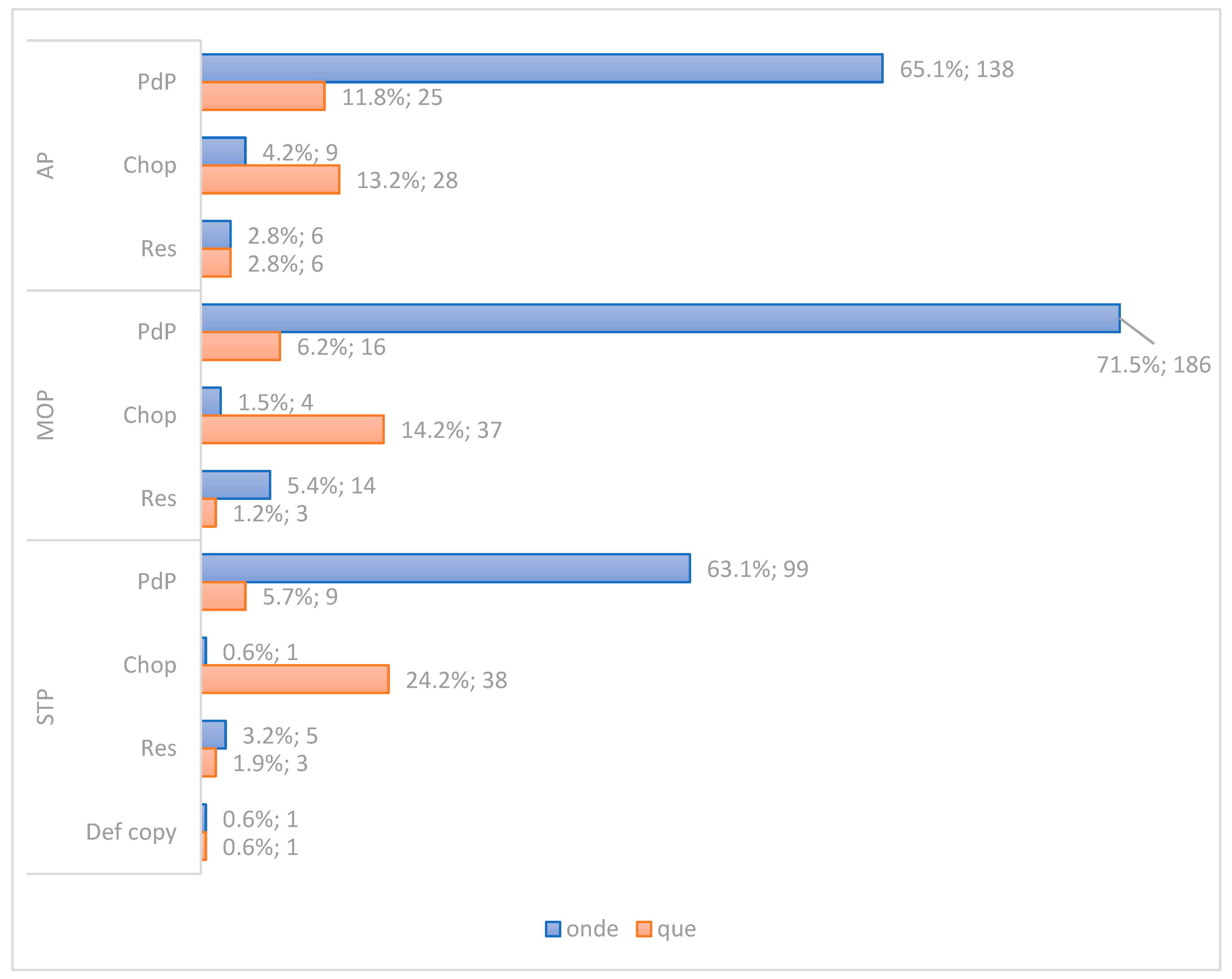

Figure 2 below sums up the results based on the extracted corpus data with the relativization mechanism and the relative markers

onde and

que. The first conclusion that can be drawn from the figure is that, in all three AVP, pied-piping is preferred (AP = 65.1%, MOP = 71.5%, STP = 63.3%), being followed by chopping, a mechanism that mainly affects

que locative relatives (AP = 13.2%, MOP = 14.2%, STP = 24.2%). Percentage wise, the ratio of use of these mechanisms in the AVP shows similarities, although P-chopping is more prominent in STP. Chopping with

onde, on the other hand, is almost inexistent in STP and more prominent in AP.

Figure 2 further shows that locative resumption and especially locative defective copying, which is exclusive to STP, are residual mechanisms in our data. Nevertheless, it should be noted that locative resumption is overall more common with

onde. Moreover, the fact that these two residual mechanisms are the canonical processes in the main contact languages Changana/Ronga and Santome, respectively (cf.

Section 4.2 and

Section 4.3 above), constitutes a strong argument against the role of language contact.

In order to assess whether there is a correlation between relativizer

onde/que and the relativization mechanisms, as suggested by the data and the results of previous research, which show a correlation between non-standard mechanisms and the use of

que, and given the characteristics of our data, in particular the limited occurrence of resumption and defective copying, we applied a Fisher’s exact test. Taking relativization mechanisms as independent variables and relative markers

onde and

que as dependent variables, the results indicate that the correlation is indeed highly significant (

p-value ≤ 0.001).

12 We further found that the correlation between relativizers

onde/que and the relativization mechanism is also highly significant in each variety (

p-value ≤ 0.001).

5.2. Syntactic Relation between the Head Noun and the Relative Clause

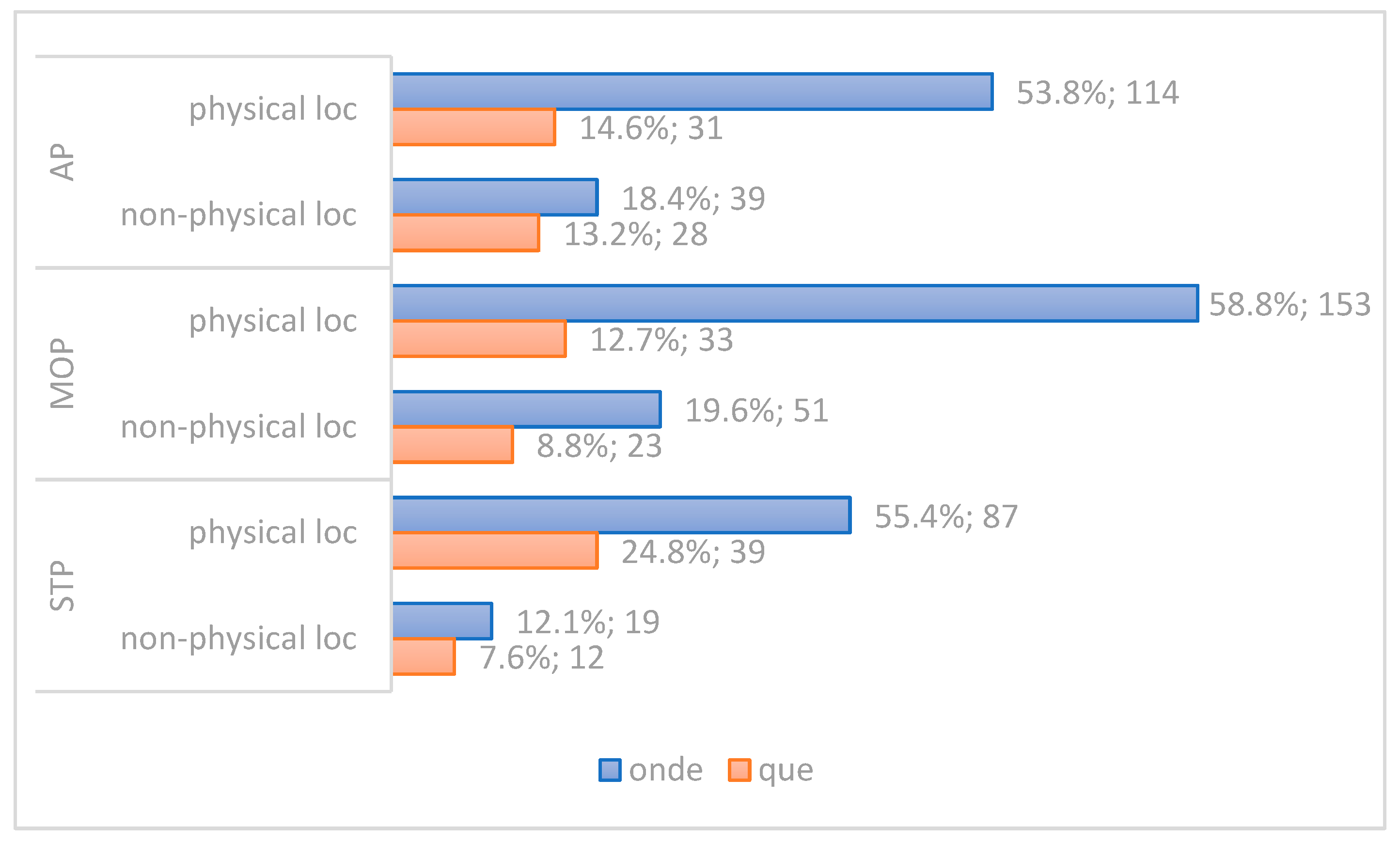

Figure 3 shows the distribution of relative markers

onde/que and the syntactic relation between the antecedent and the relative clause, i.e., whether the antecedent is an argument or an adjunct within the relative clause. We base the distinction between argument and adjunct on standard assumptions about argument structure. Locative objects of motion verbs such as

ir, ‘to go (to)’,

vir, ‘to come (to, from)’,

chegar, ‘to arrive (at)’ or

entrar, ‘to enter’, as well as the object of verbs such as

viver and

morar, ‘to live (in)’, were treated as arguments.

The figure shows that the use of the relativizer onde in the three AVP is largely preferred in locative relatives, independently of the syntactic relation between the head noun and the relative clause, i.e., irrespective of whether the antecedent is an argument, as in (14a), or an adjunct within the relative clause, as in (17c). With respect to the argument/adjunct distinction and the selection of relativizer que, AP and MOP show a proportionately higher number of contexts of locative head nouns that correspond to an adjunct in the relative clause (AP = 9.0% arguments vs. 18.9% adjuncts; MOP = 8.8% arguments vs. 12.7% adjuncts); in STP this proportion is more balanced and slightly favors arguments (17.8% arguments vs. 14.6% adjuncts).

In order to confirm the correlation between relativizers and the syntactic relation between the antecedent and the relative clause, we applied a Chi-square (χ2) test, taking argument and adjunct as independent variables and relativizers onde and que as dependent variables. Results indicate that differences observed in the production of those mechanisms are not significant (p-value = 0.373) and the correlation is, in fact, not significant in each AVP independently (AP, p-value = 0.229; MOP, p-value = 0.350; STP, p-value = 0.115).

In sum, the two sections on syntactic properties of locative relatives show that the three AVP do not differ substantially from one another in what concerns the relativization mechanisms and the distinction between argument and adjunct. The data further confirm the claim that P-chopping correlates with que in varieties of Portuguese. Locative resumption, however, is overall more common with onde in our data, but this finding requires further research, since it is based on a rather small number of occurrences.

5.3. Semantic Role of the Antecedent

Regarding the semantic role of the antecedent, a distinction was made between Locative in (19), which corresponds to static locations, and Goal/Source, which corresponds to locations introduced by verbs of movement, as shown, respectively, in (20) and (21). By considering this distinction, we aim to assess whether the selection of the relativizers

onde/que correlates with the semantic role of the antecedent.

| (19) | a. | frequentei | uma | escola | do | meu | bairro | onde | eu | cresci (MOP) |

| | | I.attended | a | school | of.the | my | neighborhood | REL | I | grew.up |

| | | ‘I attended a school in the neighborhood I grew up in’ |

| | b. | é | uma | zona | que | há | sempre | conflitos (STP) |

| | | it.is | a | region | REL | there.are | always | conflicts |

| | | ‘It’s a region where there are always conflicts’ |

| (20) | a. | nos | musseques | onde | eu | vivo (AP) |

| | | in.the | slums | REL | I | live |

| | | ‘in the slums where I live’ |

| | b. | diria | que | a | cidade | que | eu | provavelmente | me | mudaria... (MOP) |

| | | I.would.say | that | the | city | REL | I | probably | REFL | I.would.move.to |

| | | ‘I’d say that the city I’d probably move to…’ |

| (21) | a. | vivi | na | província | donde | veio | um | padrasto | meu | que | me | criou (AP) |

| | | I.lived | in.the | province | from.REL | came | a | stepfather | my | REL | me | raised |

| | | ‘I lived in a province from which came a stepfather of mine who raised me’ |

| | b. | há | palmeira | que | pode | sair | cinco | filhos (STP) |

| | | there.is | palm tree | REL | can | go.out | five | offshoots |

| | | ‘There are palm trees that may develop five offshoots.’ |

Figure 4 below sums up the results, showing that Locative antecedents by far outnumber Goal/Source antecedents and that the use of these semantic roles with

que and

onde is fairly proportional across the three AVP. Moreover, the expression of Locative is highly preferred with

onde across varieties. The main difference between the varieties concerns the use of

que vs.

onde with Goal/Source antecedents. Here, AP and STP are at opposite ends: AP shows a strong preference for

onde and STP for

que, with MOP in between (AP = 8.0% vs. 1.9%; MOP = 3.1% vs. 2.3%; STP = 1.9% vs. 7.0, for

onde and

que, respectively). As in the case of locative resumption in the previous section, this finding requires confirmation based on a larger data set.

Results of a Chi-square test, taking Goal/Source and Locative as independent variables and relativizers onde and que as dependent variables, indicate that the general correlation between these variables is significant (p-value = 0.006). However, the correlation between variables differs among the AVP. The correlation between the relative markers onde/que and the semantic role of the antecedent is significant in STP (p-value ≤ 0.001, result of a Chi-square test) but not in AP (p-value = 0.344) and MOP (p-value = 0.086) (results of a Fisher’s exact test).

Additionally, the Fisher’s exact test established a correlation between the relativization mechanism and the semantic role of the antecedent, since pied-piping is mostly registered with Locatives (<0.001). However, this correlation is significant in STP (p-value ≤ 0.001) and MOP (p-value ≤ 0.001), but not in (AP, p-value = 0.140).

At this point we should recall that it was shown that Goal/Sources and Locatives in Mbundu occur with different noun class prefixes, that is,

ku- for the former and

mu- for the later (cf.

Section 4.1). If language contact were playing a role in locative relativization, we might expect AP to exhibit a tendency toward the use of different relativizers for these different semantic roles. However, the more widespread use of

onde in AP with both Goals/Sources and Locatives than in MOP and STP shows that this prediction was not borne out. On the other hand, the more extensive overall use of

que in STP than in AP and MOP, especially with Goals, is potentially related to the use of the exclusive etymologically related relativizer

ku and the direct transitivity of Goal-selecting verbs in Santome (cf.

Section 4.3), thus arguably showing a mild contact-induced effect.

5.4. Type of Location Expressed by the Antecedent

The second semantic variable that was tested for the

onde/que distinction consists of the type of location expressed by the antecedent. Here, we adapted the typology proposed by

Nikitina (

2008) in her work on spatial Goals with motion event (‘in’ vs. ‘into’) to spatial locative relatives. This work was previously used in research on Goal arguments of verbs of directed motion in AVP (

Hagemeijer et al. 2022a), with interesting results with respect to the use of the type of location selected by the (non-standard) preposition

em with two verbs of directed motion.

13 With respect to our data, a primary distinction was made between head nouns corresponding to physical and non-physical locations, with the former type being further divided into two categories: containers and areas

14. Following Nikitina’s work, containers correspond to locations with well-defined borders lacking a transitional zone (e.g.,

house,

store,

lunch box,

sea)

15, whereas areas are locations without well-defined borders and therefore typically exhibit a transitional zone (e.g.,

neighborhood,

field,

countries,

market). The following examples illustrate the classification concerning the nature of the antecedent: (22) showcases non-physical locations, (23) containers, and (24) areas.

| (22) | a. | há | um | outro | fenómeno | aí | que | as | pessoas | trocam | de |

| | | there.is | a | other | phenomenon | there | REL | the | people | change | of |

| | | salário | durante | o | mês (AP) |

| | | salary | during | the | month |

| | | ‘There is another phenomenon there in which people change salaries during the month |

| | b. | num | ambiente | característico | de | dificuldades | onde | havia | falta |

| | | in.a | environment | characteristic | of | difficulties | REL | there.was | lack |

| | | de | quase | tudo (MOP) |

| | | of | almost | everything |

| | | ‘In a typical environment of difficulties where almost everything was lacking’ |

| | c. | Há | muitas | histórias | tradicionais | onde | o | tartaruga | aparece (STP) |

| | | there.are | many | stories | traditional | REL | the | turtle | shows.up |

| | | ‘there are traditional stories in which the turtle shows.up’ |

| (23) | a. | há | sempre | uma | capoeira | onde | se | cria | galinhas (AP) |

| | | there.is | always | a | hen house | REL | IMP | breed | chicken |

| | | ‘there is always a hen house where chicken are bred’ |

| | b. | estou | numa | loja | onde | vendo | telefones (MOP) |

| | | I.am | at.a | store | where | I.sell | phones |

| | | ‘I’m at a store where I sell phones.’ |

| | c. | dirigindo | um | centro | onde | trabalhávamos | cerca | de | trinta | mulheres (STP) |

| | | managing | a | center | REL | we.worked | around | of | thirty | women |

| | | ‘managing a center where around thirty women used to work’ |

| (24) | a. | estamos | num | sítio | em que | entrasse | um | mais | velho … (AP) |

| | | we.are | in.a | place | in REL | enter.SUBJ | a | more | old |

| | | ‘we are at a place where if an elderly person would enter…’ |

| | b. | o | tal | sítio | onde | o | meu | filho | escreveu (MOP) |

| | | the | DEM | place | REL | the | my | son | wrote |

| | | ‘that place where my son wrote’ |

| | c. | eu | estou | mais | habituado | no | bairro | onde | eu | nasci (STP) |

| | | I | am | more | used | in.the | neigborhood | REL | I | was.born |

| | | ‘I’m more used to the neigborhood in which I was born’ |

Figure 5 sums up the results for this semantic variable.

The figure shows that

onde outnumbers

que with both physical and non-physical locations in the three AVP and that the contexts with

que in all three varieties are proportionally greater with non-physical locations than with physical locations, which is especially visible in AP (13.2% vs. 18.4%). It also follows that

onde is commonly used with non-physical locations, similarly to what has been observed for EP (e.g.,

Móia 1992;

Peres and Móia 1995), a finding we do not explore in this paper.

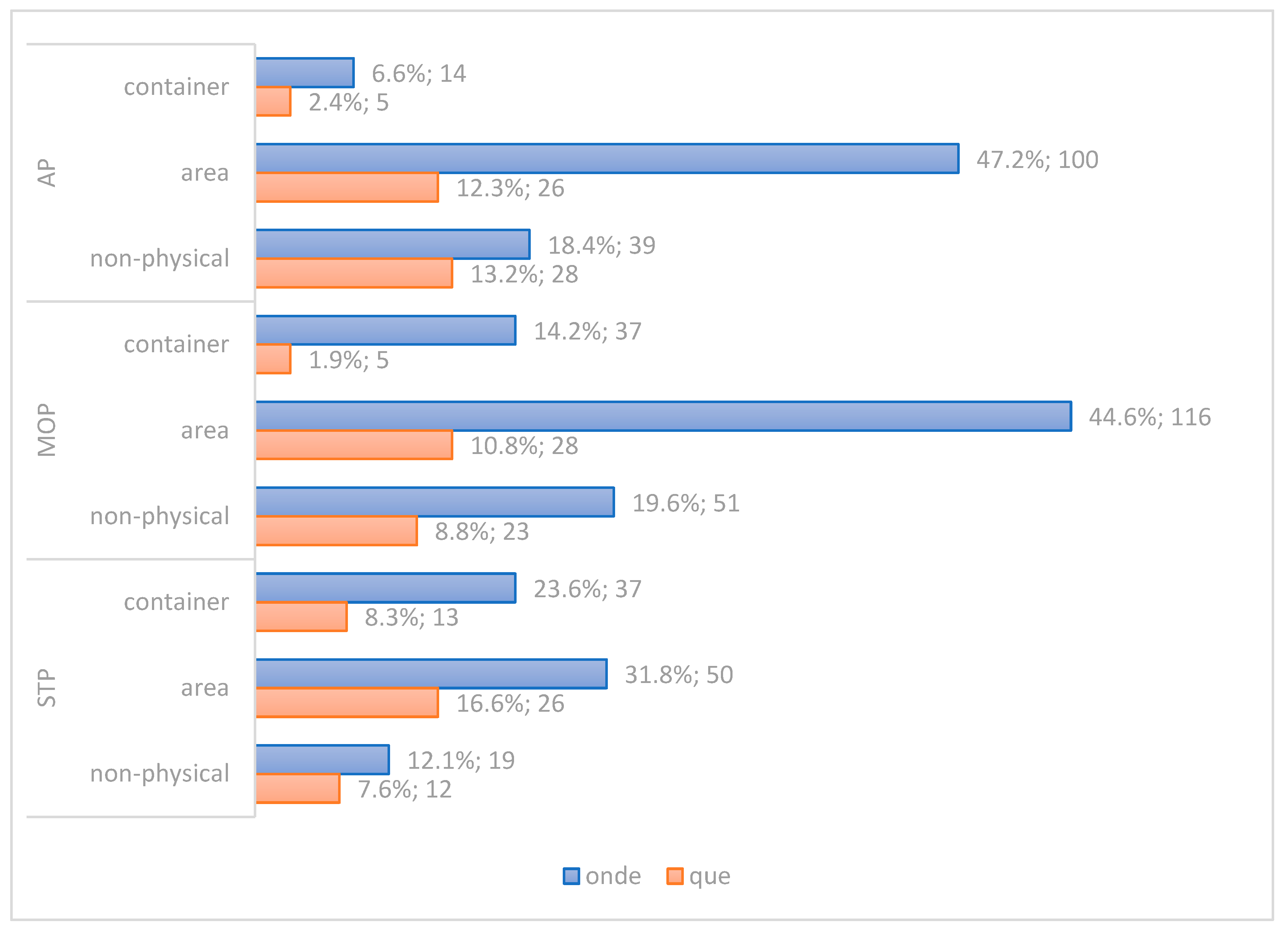

Zooming in on the distribution of relativizers according to the categories containers, areas, and non-physical, we observe several fine-grained differences between the varieties, which are represented in

Figure 6 below.

STP shows a proportionally greater number of cases in which antecedents that are areas cooccur with que instead of onde (16.6% vs. 31.8%), whereas this proportion is quite a bit lower in AP (12.3% vs. 47.2%) and MOP (10.8% vs. 44.6%). With containers, on the other hand, MOP stands out for the proportionally lesser use of que than onde (1.9% vs. 14.2%) than in AP (2.4% vs. 6.6%) and STP (8.3% vs. 23.6%).

Results of a Chi-square test, taking physical locations and non-physical locations as independent variables and relativizers onde and que as dependent variables, indicate that there is a significant correlation between these variables (p-value ≤ 0.001). Note, however, that the significance is not observed in each AVP. The correlation is significant in MOP (p-value = 0.018) and AP (p-value = 0.002), but not in STP (p-value = 0.409). An additional Chi-square test using areas, containers, and non-physical locations as independent variables confirms the correlation between relative marker and type of location in MOP (p-value = 0.036) and AP (p-value = 0.008), but not in STP (p-value = 0.447). The former varieties clearly prefer onde with areas, a tendency that is not observed in STP.

5.5. Definiteness of the Antecedent

Finally, we investigated whether the definiteness status of the head nominal is a predictor for the use of

onde and

que. Following

Wiechmann (

2015, p. 88), “[a] head was treated as definite if the entity referred to was specific and identifiable in a given context of utterance.” In most cases, the locative heads acquire this feature through definite articles and/or the presence of demonstrative and possessive pronouns. We did not analyze the variable ‘specificity’, which accompanies definiteness (e.g.,

Lyons 1999), because a relative clause by itself is a specification of the head noun. Some examples of [+definite] and [−definite] antecedents are illustrated in (25) and (26), respectively.

| (25) | a. | lá | no | escritório | onde | faço | o | part-time (MOP) |

| | | there | in.the | office | REL | I.do | the | part-time |

| | | ‘there in the office where I have a part-time job’ |

| | b. | acho | que | deve | ser | essa | escola | em que | estamos | agora (STP) |

| | | I.think | that | it.should | be | that | school | in REL | we.are | now |

| | | ‘I think it should be this school in which we are right now’ |

| (26) | a. | o | namoro | é | uma | fase | em que | duas | pessoa | do |

| | | the | dating | is | a | stage | in REL | two | person | of.the |

| | | sexo | opostos | vão | conhecendo-se (AP) |

| | | sex | opposite | go.3PL | knowing-REFL |

| | | ‘dating is a stage in which two people of the opposite sex are getting to know each other’ |

| | b. | é | um | país | livre | onde | as | pessoas | conseguem | fazer | tudo | que |

| | | it.is | a | country | free | REL | the | people | can | do | all | that |

| | | ‘It’s a free country where people can do whatever they need to.’ |

| | | eles | precisa (MOP) |

| | | they | need |

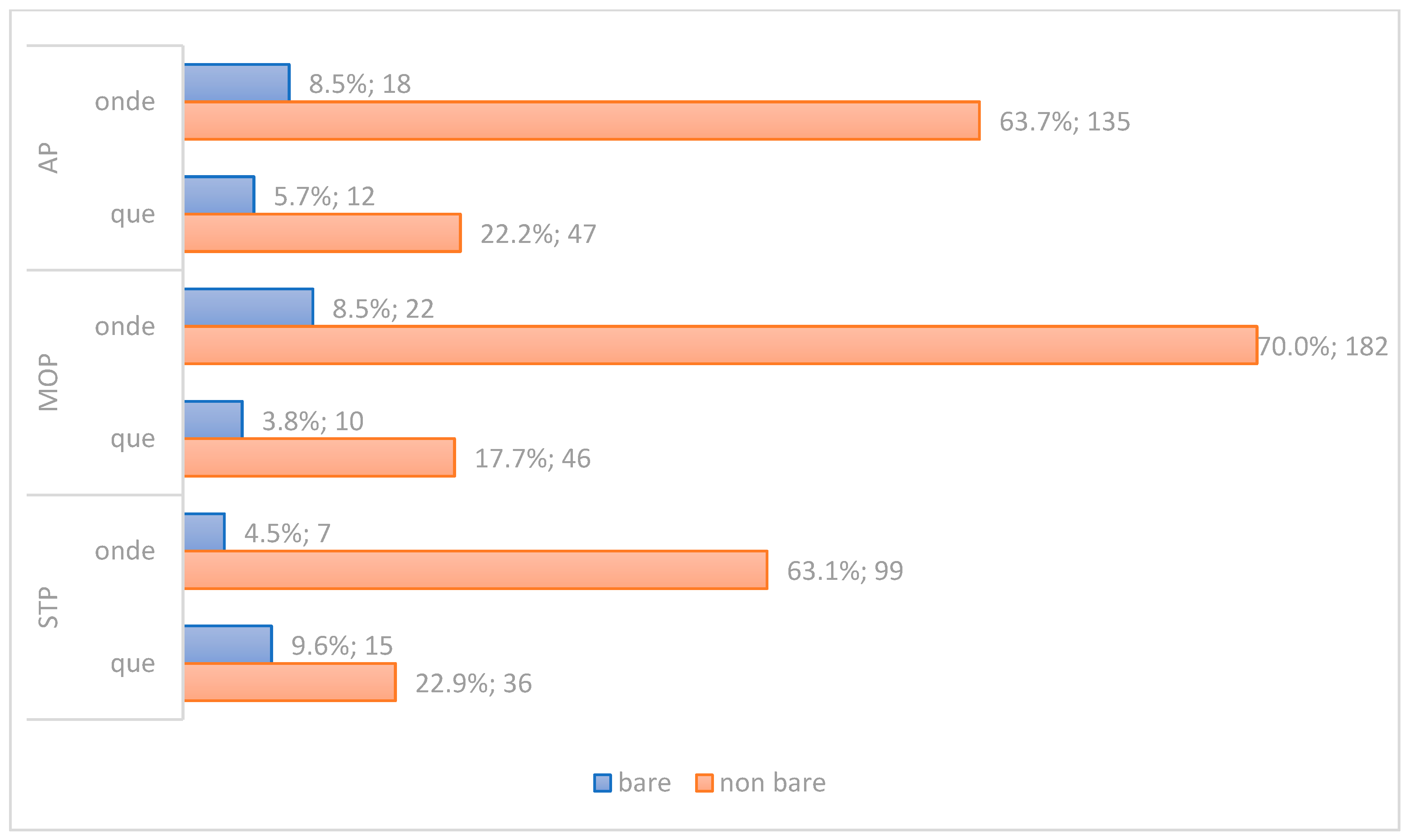

Figure 7 below shows the overall results for the three AVP.

The figure shows that [+definite] contexts largely outnumber the [−definite] contexts in all three AVP. Moreover, the relativizer onde is strongly preferred in [+definite] contexts. On the other hand, que correlates more strongly with [−definite] than with [+definite] in AP and STP (AP = 17.9% vs. 9.9%; STP = 20.4% vs. 12.1%), with MOP showing the weakest correlation (10.4% vs. 11.2%).

Results of a Chi-square test, taking [+definite] and [−definite] as independent variables and relative markers onde and que as dependent variables indicate that there is a significant correlation between these variables, which is observed in each AVP (AP p-value ≤ 0.001; MOP p-value = 0.008; STP p-value ≤ 0.001).

In order to further test whether less specified head nouns correlate with

que, we additionally analyzed the occurrence of singular and plural bare noun locative antecedents with

que and

onde. The following examples illustrate bare nouns with

que, which occur commonly in existential constructions with

haver, ‘to be’.

| (27) | porque | há | áreas | que | pedem | um | preço | elevado (AP) |

| | because | there.are | zone | REL | they.ask | a | price | high |

| | ‘because there are zones where they ask a high price’ |

| (28) | há | sítios | que | nem | dá | para | falar | changana (MOP) |

| | there.are | place | REL | not.even | is.possible | to | speak | Changana |

| | ‘there are places where it is not even possible to speak Changana’ |

| (29) | mas | há | casa | ainda | que | entra | água (STP) | |

| | but | there.are | house | still | REL | enters | water | |

| | ‘but there are also house where the water enters’ |

If our hypothesis is on the right track, the prediction is that bare nouns—the least specified head nouns—should cooccur more commonly with

que than

onde.

Figure 8 shows the overall results for the three AVP.

While locative bare nouns do occur with both que and onde, they are proportionally more common with the former relativizer. The main difference is observed in STP, which exhibits a higher number of bare noun locative antecedents with que than with onde, whereas the reverse situation applies to AP and MOP (STP: 9.6% vs. 4.5%, AP: 5.7% vs. 8.5%; MOP: 3.8% vs. 8.5%). These two findings underscore the hypothesis that less specified locative antecedents increase the likelihood that que is selected, and that this tendency is particularly relevant in STP. In fact, results of a Chi-square test, taking [bare] and [non-bare] as independent variables and relative markers que and onde as dependent variables indicate that there is a significant correlation between these variables (p-value ≤ 0.001). However, the correlation is only significant in STP (p-value ≤ 0.001). No correlation was found in MOP (p-value = 0.154) and AP (p-value = 0.108).

5.6. Summary

The previous sections have shown that, generically speaking, the three AVP at stake do not differ substantially from each other with respect to the syntactic and semantic variables under discussion, although some tendencies are worth emphasizing.

For the syntactic variables, the data convincingly show that the preferred relativization mechanism is (standard) pied-piping, which is mainly observed with onde, followed by P-chopping in contexts with the relative que, particularly in STP. With respect to syntactic relation of the antecedent, no correlation was found between the distinction argument/adjunct and the relativizers que/onde.

Regarding the semantic variables, the data lead to three main observations. In the first place, locative relatives, whose antecedent head noun has the semantic role of Locative, mainly occur with onde across varieties; when Goals/Sources are involved, AP prefers onde whereas STP prefers que. The second observation concerns the type of location. Considering the distinction between physical and non-physical locations, AP and MOP behave alike in their preference for areas with onde; STP, on the other hand, exhibits a higher variation between the two relativizers with head nouns that are areas. Third, the data clearly demonstrate a correlation between the definiteness of the antecedent and the relativizer in the three AVP: onde is strongly preferred with [+definite] antecedents, whereas que correlates with [−definite], a correlation that is particularly strong in STP, where it is also observed with bare head nouns.

In the next section, we discuss the results in more detail, and consider the extent to which our working hypotheses have been confirmed.

6. Discussion

The analysis of the syntactic and semantic variables in the previous sections has shown that the three AVP show considerable uniformity, differing among each other with respect to a few smaller details. Given the differentiated typological relativization properties of their main (historical) contact languages, the role of language contact, often considered a major factor with respect to the linguistic patterns found in these varieties, is not supported. First, the primary syntactic mechanisms in Changana/Ronga (resumption) and Santome (defective copying) are the exception rather than the rule in MOP and STP. In these varieties, as well as in AP, pied-piping, followed by P-chopping, are by and large the most common mechanisms. Second, the (morphological) distinction between Goal/Source and Locative relativization characterizing Mbundu lacks a counterpart in AP, which rather shows a tendency to generalize the relativizer

onde, also for Goal/Source, differently from MOP and STP. Third, the [±definite] status of the antecedent head noun does not lead to different strategies in the contact languages, where head nouns require noun class morphology (Mbundu and Changana/Ronga) or exhibit an invariable relativizer (Santome). On the other hand, the more extensive use of relativizer

que in STP, as compared to AP and MOP, appears to reveal a mild effect of language contact, possibly due to the etymological overlap with the generalized relativizer

ku in Santome. In addition, the greater number of cases of P-chopping of the preposition

a, ‘to’, with head nouns bearing the semantic role of Goal in STP, may also show the effect of language contact, since verbs of directed motion in Santome are transitive (V + Goal), as shown in

Section 4.3. Note, however, that these cases are restricted to relative clauses (and more generally to cases of fronted locatives), since Goal arguments of directed motion verbs in STP, in particularly the most common verb ir, ‘to go’, are typically introduced by a preposition (

para, a, em) when they occur in the canonical object position (

Hagemeijer et al. 2022a). In other words, it cannot be argued that P-chopping in STP relatives is a consequence of a general change to the subcategorization properties of directed motion verbs.

With respect to the syntactic mechanisms, we have shown that the three AVP follow standard European Portuguese in generally using pied-piping (mainly through

onde). While this finding also applies to STP, in this variety

que shows a proportionally higher use than in AP and MOP. Regarding the frequency of P-chopping (and resumption), the findings from the AVP are in line with what has been observed in the literature for EP and BP (e.g.,

Alexandre 2000;

Espírito Santo et al. 2023;

Selas 2014;

Veloso 2013 for EP; and

Corrêa 2001;

Kato 2010;

Ribeiro 2009;

Tarallo 1985 for BP), including the loss of agreeing or Case-specified relative markers and the rise of

que, associated to non-standard strategies, in particular P-chopping.

16 Locative defective copying is the exclusive territory of STP. As expected, the correlation between relativizers

onde/que and relativization mechanisms are statistically significant, since

onde is mainly found with pied-piping and

que with P-chopping. A couple of fine-grained differences arise with respect to the use of

que and the distribution of contexts of P-chopping with respect to arguments and adjuncts, but they were not statistically significant. Some of the more specific results are, on the one hand, the greater number of relatives with

que and chopping of the preposition

a, ‘to’, and

em, ‘in’, introducing arguments in STP, which we addressed above, and, on the other hand, the higher frequency of P-chopping with

em over pied-piping of this preposition in MOP and STP, with AP showing a more balanced distribution of these two mechanisms.

We further found that the distinction Goal/Source vs. Locative is proportionally balanced across the three AVP with respect to the occurrence of onde and que. In light of the [+locative] feature of this relative marker and the absence of this feature from que, this result was expected. The correlation between relativizer and semantic role of the antecedent was found to be statistically significant in MOP and STP, but not in AP, where onde is more extensively used with Goal/Source as well.

In what concerns the type of location, the data point to a significant correlation between the choice of relativizer and physical locations, specifically areas, which is observed exclusively in AP and MOP. The absence of this correlation in STP can be accounted for by the more balanced use of que with areas and containers in this variety than in AP and MOP. Moreover, and similarly to other varieties of Portuguese, onde is also commonly used with non-physical locations.

Finally, the most relevant and novel finding is that of a significant correlation between

onde and [+definite] head nouns and between

que and [−definite] head nouns. To account for this finding, we propose that (overtly) less specified antecedents show a greater preference for relativizer

que. In the literature on relativization in Portuguese, this form has been argued to lack feature specification as compared to other relativizers, such as

quem,

cujo/a(s),

qual/quais, and

onde, which has led several scholars to treat it as a complementizer (e.g.,

Alexandre 2000;

Tarallo 1985)

17. Although these studies do not focus on locative relativization, the idea of relativizers with a different featural makeup can be extended to the contrast between

onde, which arguably bears Oblique Case (

Alexandre 2000) and a locative feature (

Peres and Móia 1995;

Veloso 2013), and

que, which would of course lack such feature specification.

The hypothesis that that less functionally specified head nouns select the least specified relativizer requires further investigation, in order to determine whether this is yet another property that ultimately leads back to restructuring in the functional domain. It is well established that some of the most functional features of EP have undergone significant restructuring in AVP, and also in BP, which encompasses, for instance, the following tendencies: the loss of accusative clitics (e.g.,

Gonçalves et al. 2023); the partial replacement of locative preposition

a, ‘to’ (

Hagemeijer et al. 2022a); and a reduction in overt number agreement (

Brandão 2011;

Jon-And 2011). In this sense, the definiteness effect observed in locative relativization of AVP can be seen as a case of language-internal restructuring based on an agreement relation which involves the degree of feature specification and the available relativizers in Portuguese: each of the two relative markers specializes, to some extent, for a different semantic environment. Of course, as in many other domains of the grammar of AVP, these are tendencies within the large spectrum of variation which are unlikely to fully crystallize.

7. Final Remarks

The empirical data discussed in this paper resulted in a survey of locative relativization, a topic that has hardly been explored for Portuguese. We provided a first, corpus-based description and analysis of syntactic and semantic properties of spatial locative relativization in the nativizing, urban varieties of Portuguese spoken in Angola, Mozambique, and São Tomé and Príncipe. In addition, we developed a statistically supported discussion of the syntactic and semantic features of the head noun and the relative clause in order to determine what, if anything, drives the selection of the relativizer que or onde.

Overall, our analysis shows that the three AVP are considerably homogeneous in the domain of locative relativization: (i) the three varieties mainly exhibit

pied-piping as a primary mechanism and P-chopping as a secondary mechanism, independently of the distinction between argument and adjunct; (ii)

onde correlates with Locatives and areas, although AP also extends this relative marker to Goals/Sources, and STP exhibits a higher degree of variation between

onde and

que with areas and containers (physical locations); and (iii) [−definite] and generally less specified antecedents show a greater preference for relativizer

que in all three AVP, a preference that is especially pronounced in STP. Interestingly, while

que is gaining space in the domain of locative relativization, we also notice that

onde is extending its functions to other semantic roles (cf.

Ballarè and Inglese 2022) beyond physical locations, showing the dynamics of relativization and locative relativization in particular.

The results of our research also led us to argue that the role of language contact, which is often considered a driving factor in studies on AVP, should be largely dismissed, since the mechanisms of relativization that characterize the main contact languages are not only distinct from the AVP but also from each other. It also shows that language contact may be more or less prominent, or more or less direct, according to the (sub)domain of grammar under analysis. Using the same corpora,

Hagemeijer et al. (

2022a) also downplay the role of language contact in the domain of PP selection of directed motion verbs, although in other studies based on the same data,

Gonçalves et al. (

2022,

2023) show that language contact plays a role in the expression of dative objects and anaphoric direct objects (clitics and pronouns).

The larger spectrum of variation that typically characterizes AVP as compared to EP, and arguably—but perhaps less clearly—also BP, can be assigned to the fact that Portuguese in Africa was until recently, or still is, an L2 in complex multilingual settings. Nevertheless, several quantitative studies in the domain of syntax and morphosyntax show that, despite robust variation, the dominant patterns within the variation of certain features in the AVP are often also the ones that are also dominant in EP, which ultimately implies that variation does not necessarily lead to a new outcome, i.e., the consummation of change.

Finally, with the working hypotheses on the table, the findings of this paper can be further investigated for these and other varieties of Portuguese, especially EP and BP. Moreover, some of the findings require a larger data set or, for example, the application of elicitation tasks, in order to further test and confirm the observed tendencies.