1. Introduction

Pano languages have highly complex systems of same/different subject marking. Same/different subject clauses are described as subordinate in many grammars of Pano languages (

Fleck 2003, p. 1001;

Valenzuela 2003, p. 413;

Tallman 2018a, p. 317;

Camargo Souza 2020). However, a detailed investigation of such clauses in terms of the criteria typically used to distinguish coordinate and subordinate clauses has not been conducted.

Neely (

2019, p. 434) claims that the relative coordinate or subordinate status of such clauses requires more research. Same/different subject clauses in Pano languages appear to be, in very general terms, structurally and functionally similar across Pano languages. Such clauses are marked for whether their subject is co-referential or obligatorily not co-referential with the subject of the main clause. Same-subject clauses also display “transitivity harmony” (

Valenzuela 2005,

2013). They code whether the subject of the main clause is an A (subject of a transitive) or an S (subject of an intransitive) argument.

Whether “switch reference” clauses are described as subordinate or coordinate in the linguistic literature can partially depend on theoretical considerations.

Finer (

1985) seems to assume that all switch reference clauses are subordinate, and

Roberts (

1988) argues that switch reference clauses are coordinate based on a number of diagnostics (see

Keine 2013 as well). More recent literature has claimed that some switch reference clauses are subordinate and others are coordinate (

Stirling 1993;

McKenzie 2015), while others have advocated for a third category or some subtype of coordination (

Weisser 2012). In McKenzie’s survey of switch reference in North America, he argues that the debate about whether switch reference is coordinate or subordinate is “moot” because “SR is North America occurs with all types of clause connectives” (

McKenzie 2015, p. 429). In other words, whether switch reference is subordinate or coordinate is a matter of typological variation (see the work of

Baker and Souza 2019, for a recent overview).

Such perspectives assume that a discrete distinction between “coordinate” and “subordinate” clauses, borrowed from traditional grammar, is necessarily theoretically valid. They assume that there is an a priori distinction between coordinate and subordinate clauses (perhaps as a matter of language design) and it is simply a matter of picking the right set of distinguishing features that home in on the ideal type. Functional–typological literature, applying wider array of diagnostics more consistently, has suggested that there is a continuum between subordination and coordination types (

Haiman and Thompson 1984;

Lehmann 1988;

Foley and Van Valin 1984;

Van Valin 1993;

Croft 2001;

Cristofaro 2003). From this perspective, a linked-clause construction is coordinate or subordinate to some degree. The question arises as to whether actual typological patterns organize themselves into prototypes (

Bickel 2010), perhaps due to functional and diachronic “attactor points” (

Hawkins 2004;

Bybee and Beckner 2015;

Schmidtke-Bode 2019). In order to investigate clause linkage from such a perspective, detailed descriptive works are necessary, which apply a methodology that does not reify or presuppose candidate attractor points.

As stated above, in most works on Pano linguistics, same-subject clauses are described as “subordinate”. Evidence for this in Chácobo may come from the fact that an interrogative constituent can be asymmetrically extracted from the same-subject clause as in (1) below and such asymmetric extraction is typically regarded as evidence of subordinate status (

Ross 1967). We can also see that the same-subject clause

yonoko=só “work before V” is center-embedded, potentially yet another piece of evidence for subordinate status (

Bickel 2010).

| 1. | hɨnawa=ʂói | tsi | yonoko=ʂó | ti | ina | taʃi= ́ | tɨpas=ʔá | |

| | how=sa | lnk | work=prior:sa | t | dog | Tashi=erg | kill=inter:pst | |

| | ‘How, after working, did Tashi kill the dog?

(‘How did Tashi work after killing the dog?’) |

Not all data point to a subordinate status for this construction in Chácobo, however. First, note that main clauses can also be center-embedded. An interrogative constituent can extract from a post-posed same subject clause (producing a sentence which is difficult to translate), which is generally unavailable to adjunct subordination (

Bošković 2020).

| 2. | hawɨi | kako | ho=ʔá | ti | kopi=ʔáʂna |

| | how=sa | lnk | work=inter:pst | t | buy=prior:ss |

| | ‘What, after Caco arrived, did he buy?’ |

Thus, center-embedding may not apply in this case, because it also suggests that the main clause is subordinate (

Weisser 2015 on problems in interpreting such diagnostics). Illocutionary scope suggests that same-subject clauses in Chácobo may be a coordinated structure (

Jendraschek and Shim 2018, inter alia). Subordinate clauses will typically be presupposed information, but in Chácobo, an interrogative illocutionary marker can scope over each predicate, suggesting a more coordinate-like structure.

| 3. | tʃaʃo | pi=ʔi | tsi | hɨɾɨ=yá | tʃani=ka(n)=ʔá |

| | pig | eat=concur:ss | lnk | Gere=com | speak=3pl=inter:pst |

| | ‘Were they eating and were they speaking with Gere?’, ‘While they were eating, did they speak with Gere?’ |

Furthermore, we also expect subordinate clauses to be de-ranked compared to main clauses, displaying less tense-aspect-modal contrasts, for instance. While there are some limitations in marking, overall same-subject clauses display most of the same marking as main clauses, suggesting a relatively higher coordinate status. Nor are such cases of mismatch rare (

Bickel 2010;

Weisser 2012,

2015;

Jendraschek and Shim 2018).

One approach to this apparent ambiguity is to discard the conflicting data.

1 We could choose one criterion (e.g., “extraction”) and discard the others as irrelevant to the assessment of that particular construction in Chácobo, changing which criteria are relevant or irrelevant depending on the language and classifying each construction based on whatever diagnostics give us the results that conform to our preferred theoretical position (see

Hofmeister and Sag 2010 for a relevant discussion on islands). However, this approach has been criticized as methodologically biased (

Croft 2001) and is foreign to the methods in all mature sciences (

Mayo 2018;

Tallman 2021a, among others). If the distinction between subordination and coordination is taken as a grammatical primitive or the distinction represents some sort of substantive universal, explicit conditions need to be stated for its falsification. However, positing that it is appropriate to discard conflicting evidence in order to maintain a desired hypothesis at best makes claims about the universality of the distinction confirmationally lax, and, at worst, immunizes such a claim against falsification, making it a tautology: a coordinate–subordinate distinction can be recognized because diagnostics exist and can be cherry-picked to rationalize the distinction; however, the linguist sees fit. To assume that because a distinction is used in descriptive work, it must reflect a distinction which manifests substantive universals, is to lift a heuristic methodological unit into a theoretical postulate without justification. And to insist that the distinction is a well-tested hypothesis (and not a metaphysical prejudice) while maintaining that its falsification is in principle impossible is to seriously misunderstand scientific method (see

Ozerov 2018 for a discussion of similar problems with the categories topic and focus categories, and

Tallman 2020,

n.d. on the notion of ‘word’, ω and X0).

From a typological perspective, allowing the definition of coordination and subordination to vary leads to problems for linguistic comparison. It is not clear that one linguist’s “subordination” will correspond to the next’s, if linguists are choosing criteria inconsistently. Assuming a distinction without providing a fixed and consistent empirically operationalized definition applied rigorously from one language to another will result in non-commensurability between language descriptions and hinder our ability to make verifiable and robust cross-linguistic generalizations. One solution to this problem would be to propose a fixed definition by fiat (a “comparative concept” or “retrodefinition”) defining coordination or subordination based on a single criterion so that the concept at least as mneumonic value (

Haspelmath 2010,

2018). This perspective would preserve the traditional terminology without making claims about its usefulness in accounting for constraints on cross-linguistic variation, apart for making it clearer what researchers mean by the terms.

In this paper, I take a different approach, inspired specifically by

Bickel’s (

2010) multivariate approach to clause linkage, but more generally by work on polythetic classification in the biological sciences and other fields (

Sokal and Sneath 1963;

Needham 1972;

Ellen 2008;

Parnas 2015). Polythetic classification refers to classification in the absence of necessary and sufficient criteria for the relevant classes. In a systematic review of the diagnostics that distinguish between coordination and subordination,

Bickel (

2010) deconstructs the properties that have been posited as diagnostics to distinguish between coordination, subordination and/or co-subordination into a typological variable.

2 While cluster methods show that there are perhaps subordinate and coordinate prototypes, the typological variation in clause linkage swamps the simple classifications used in general linguistics. In this approach, an interesting question arises as to whether there is some “statistical order” to the patterns: there are no jointly sufficient and necessary conditions for distinguishing between coordination and subordination, but perhaps cross-linguistically and in a given language, the relevant diagnostics cluster into two groups better than would be expected if such a distinction was not relevant. The distinction between coordinate and subordinate is seen as a latent variable responsible for correlations between test results. I apply this perspective to the description and analysis of clause-linkage clauses in Chácobo.

This paper also provides the first detailed description of clause linkage in Chácobo (Pano). I show that the majority of Chácobo clause-linkage constructions (which includes all “switch-reference” clauses) are neither subordinate nor coordinate. I make this argument in the first place, by considering how Chácobo clause-linkage constructions pattern with respect to a broader typological sample, showing that they fall into neither candidate subordinate nor into candidate coordinate “prototypes”, but simply occupy a liminal middle ground (

Weisser 2015;

Jendraschek and Shim 2018). I also make this argument language-internally, based on a wider variety of more fine-grained features than

Bickel (

2010). On language-internal grounds, the clause-linkage constructions of Chácobo do not cluster into two groups much better than chance with some differences arising depending on how the variables are aggregated. They do vary substantially from one another on language-internal grounds, but characterizing this variation in terms of coordination or subordination is misleading. I make this point with hierarchical clustering models coupled with simulation methods.

Section 2 provides language background on Chácobo.

Section 3 describes the dependent clauses of Chácobo.

Section 4 provides a description of the clause-linkage variables in relation to the clause-linkage constructions of Chácobo. This section contains some revisions of Bickel’s criteria. Such revisions are to be expected in an autotypology approach (

Bickel and Nichols 2002). Tests related to interrogative constituents need to be broken down further in Chácobo. Pano languages also display a type of “clause-skipping” in their agreement patterns that could be rallied as a diagnostic as well, since it plausibly related to Bickel’s “layer of attachment”.

Section 5 and

Section 6 are concerned with assessing the degree to which a coordination–subordination distinction is motivated in Chácobo. I argue that it is not, based on two types of arguments: (i) one relying on the relative closeness of Chácobo clause-linkage strategies to candidate “prototype” subordinate and coordinate constructions; (ii) another based on whether there is evidence for language-internal clustering into two types of clause-linkage strategies.

Section 7 provides some concluding remarks and discusses future research and problems with the application and comparability of some of the diagnostics.

2. Chácobo Language Background

Chácobo is a southern Pano language of the northern Bolivian Amazon. The language is spoken by approximately 1500 people. It is spoken in the town of Riberalta (Beni, Vaca Diez), and villages on or close to the Geneshuaya, Ivon, Benicito, and Yata rivers. The largest Chácobo village is Alto Ivon with about 500 inhabitants (and growing). Chácobo is still learnt as a first language by children in the villages. Typically, children who grow up in Riberalta do not learn to speak the language, perhaps acquiring a passive knowledge of it.

Chácobo has a relatively simple segmental inventory with four vowels (i, o, a, ɨ) and 14 consonants (p, t, k, β, ts, tʃ, n, m, s, ʃ, ʂ, ʔ, h, j, w). Syllable structure is (C)V(C). All consonants can occur in the initial position, but only sibilants can occur in the coda position. In some dialects of Chácobo, the glottal fricative /h/ can occur in coda position, but the number of forms with the coda /h/ in the lexicon is relatively small.

Chácobo can be described as a tonal language in the sense that lexical items are distinguished by consistent indications of pitch (

Hyman 2006).

3 Lexical items in Chácobo have their syllables specified as either toneless or LH. The H has a relatively higher pitch on the syllable the LH is docked to. Throughout, I will mark a lexical LH with an acute accent. The timing of the L depends on morphosyntactic context. Within lexical items or highly frequent sequences of lexical items L is realized on the prior syllable. At less frequent junctures, the L is realized during on the syllable it is specified for. In other words, a form such as

kamáno “jaguar” with the LH on the second syllable will be realized as [kàmáno] “jaguar”. A form such as

honi “man” with the LH on the first syllable will be realized as [hǒni] with a contour tone on the first syllable. A tone reduction rule in Chácobo deletes an H if it occurs left-adjacent to a lexical LH (LHLH → LLH). The rule applies obligatorily, optionally, or not at all depending on context (

Tallman 2018a;

Tallman and Elías-Ulloa 2020). Chácobo also has grammatical (ergative, genitive, spatial) floating LH tones and morphemes which condition the appearance of an LH tone on an element to their left in certain circumstances. For instance, the adjectivalizer = ́

ʂɨni has a floating LH to its left which docks to the final syllable of the element the morpheme combines with:

tsaya “look” becomes

tsayá=ʂɨni “a looker”.

While I refer to LH as a lexical tone, it should be pointed out that, in this context, I mean “lexical” as in lexical item, not an element that has lexical content. Nor should lexical here be taken to imply that tone sandhi rules that affect LH occur inside a lexical (as opposed to post-lexical) phonology. It simply means that morphemes in Chácobo are listed as having LH tones docked on certain syllables.

Chácobo is dependent-marking: it codes grammatical relations with case on noun phrases. Case marking on noun phrases display an ergative alignment. The ergative case is marked with a floating LH tone which falls on the final syllable of an A noun phrase. The grammatical relations S and P are unmarked in full nouns. Pronouns display a nominative–accusative alignment, however.

All clauses in Chácobo come with a clause-type morpheme, which codes clause-type (declarative, interrogative, imperative reportative) and other categories such as tense depending on the marker. There are two main types of clauses: verbal and nonverbal predicate. These can be distinguished according to four properties: (i) the clause-type marker; (ii) ergative marking on full noun phrases; (iii) the order of predicate and A/S role (“subject”); (iv) the part of the speech category of the predicate.

Table 1 summarizes the differences between the different clause types. There is an additional mixed clause type, which combines properties of verbal and non-verbal predicates. In the work of

Tallman (

2018a), this is referred to as a

c-subj verbal predicate construction, because the A/S subject must occur after the clause-type morpheme.

Examples in (4), (5), and (6) below illustrate the verbal, non-verbal, and mixed predicate constructions in Chácobo.

| 4. | kamáno= ́ | hóni | á(k)=kɨ |

| | jaguar=erg | man | kill=decl:pst |

| | “The jaguar killed the man.” |

| 5. | hóni | ʂo | tóa |

| | man | decl | dem:dist |

| | “That is the/a man.” |

| 6. | áshi=kɨ | hóni |

| | bathe=decl:ant/perf | man |

| | “The man has/had bathed.” |

Salanova and Tallman (

2020) suggest that the mixed construction is a non-verbal predicate construction with an embedded verbal predicate. Apart from the properties listed in

Table 1, which it has in common with non-verbal predicate constructions, evidence for this comes from the fact that two of the clause-type markers of the mixed constructions contain material found in dependent clauses: =

ʔi is a concurrent same subject clause marker (see

Section 3 below). For the purposes of this paper, I treat mixed constructions as verbal predicate constructions. The reason for this is that, in contrast to the predictions of

Salanova and Tallman (

2020), transitivity agreement between the same/different subject clauses and mixed main clauses treat such constructions as verbal predicate constructions.

Chácobo verbal predicates can be modified by many temporal, aspectual, modal, and evidential categories including “lexically heavy” categories such as associated motion. Chácobo verbal predicates are coded obligatorily for temporal distance (or “graded tense”) for which there are six overtly expressed categories: =

ní “remote past”,

=yamɨ́t “distant past”,

=ʔitá “recent past”,

=yá “recent past (perfect, mirative)”,

=tsi~=tsa “immediate present/past”,

=ʃaɾí “tomorrow”,

=ʂɨ́ ‘remote future (

Tallman and Stout 2016). The language also has a highly elaborate associated motion (AM) system. The associated motion markers display suppletive allomorphy depending on the transitivity of the verb they combine with and the number of its S/A subject: (i) =

kaná~=βoná “going”, (ii) =

honá~=βiná “coming”, (iii)

=kayá~=βayá “do and go”, (iv) =

kiria~=βiria “do and come”, (v)

=kó~=boʔó “do and go (distributed)”, (vi)

=koná~=boʔoná “go, do and come”, among others (

Tallman 2020). These facts should be kept in mind when discussing whether a given dependent clause is “finite” or not: it is unclear what exactly finiteness means in the context of Chácobo verb structure as it is unclear which of the aforementioned categories should be considered inflectional and which not.

4 In this paper, I assume that the potential expression of associated motion can be considered part of the relative finiteness of a clause.

The data for this paper come from approximately 32 months of fieldwork and an annotated corpus of about 28 h, transcribed and translated in ELAN. Data from naturalistic speech are supplemented with data from elicitation. Data from elicitation come from Caco Moreno and were double-checked with Miguel Chávez. Some of the extraction data could only be verified with one speaker, however, and are thus not necessarily as reliable. Part of the corpus for these data is documented with ELAR (

Tallman 2018b).

3. Dependent Clauses

All dependent clauses in Chácobo can be usefully divided into four types depending on how they constrain subject A/S coreference. Same-subject (glossed ss or sa) clauses have A/S subjects which is coreferential with the S/A subject of the main clause. Different-subject (glosses ds/a) clauses have an S/A subject which is not coreferential with that of the matrix clause. Noun-modifying clauses (nmd) and nominalized clauses (nmlz) are unspecified with respect to whether their subject is coreferential with that of main clauses. Note that noun-modifying and nominalized clauses can take on an adverbial function.

Same and different-subject clauses vary in terms of the temporal relation they have with the main clause (‘Temporal relation” in the table below). Some dependent clauses alternatively function to modify noun phrases (“Noun-modifying”) and some can function as arguments of verbs (“Referential function”). An overview of the clause-type morphemes is provided in

Table 2.

None of the clause-linkage constructions are dedicated complementation constructions insofar as complementation is defined in terms of core arguments of the main verbs. However, the agentive nominalized clause

can take on this function: it can function as a clausal argument of the verb, even though this is not very common in natural speech (

Tallman, Forthcoming). This is important because

Bickel (

2010) claimed to only code clauses which were plausibly of an adjunct status. All clauses of Chácobo have such a status, or at least could be analyzed as such. The only caveat is that there is one clause-linkage strategy which can take on a complementation function (those clauses marked with =

ʔái(na) “agentive nominalizer”).

Note that some of the markers have phonologically short and long allomorphs. The short forms appear when the dependent clause occurs before the clause-type morpheme of the main clause. The long form occurs when the dependent clause occurs after the clause-type morpheme of the main clause. For instance, the short forms of the prior same-subject markers

=ʔaʂ(na)~=

ʂó(na) occur when the dependent clause occurs before the clause-type markers as in 7 and 8. Examples of the long forms are found in 35 and 36 (

Section 4.1). These examples also illustrate that same subject-clauses code the transitivity of the main clause. This is called inter-clausal participant agreement in Pano linguistics (

Valenzuela 2005).

5| 7. | hawɨ́ | poko | pi=ʂó | tsi | no | ima=ní=kɨ |

| |

3sg:gen | intestine | eat=prior:sa | lnk |

1pl | roast=rempst=decl:pst |

| | “After eating his intestines, we roasted it.” 0027:004 |

| 8 | paʔití | nima=ʔáʂ | tsi | kiá | áʃiná= ́ |

| | jug | put=prior:ss | lnk | report | Ashina=erg |

| | kí-tʃa=ní=kɨ | | | |

| | leg-open=rempst=decl:pst | | | |

| | “Ashina put down the jug and opened her legs (over it).” 0818:0003 |

Same-subject clauses can also be distinguished according to the temporal relation they code. The examples in 7 and 8 above encode that the event of the dependent clause is prior to that of the main clause. The morphemes =

ʔí(na) and

=kí(na) encode an event which is concurrent or subsequent to the event of the main clause. Examples are provided in 9 and 10 below.

| 9. | hátsi | ʂokóβa | ʃita=kí | tʃoʃ-a=kɨ́ |

| | then | children | cross=concur:ss | step.on=tr-prior:ds/a |

| | tsi | ratɨ=ʔi | kiá | hóni | |

| | lnk | be.scared=c | report | man | |

| | “Then when the children crossed (the patio), they would step on (near his penis), and the man was scared.” 0804:0038 |

| 10. | hátsi | kama | síɾi | hiá=ɾoʔá |

| | then | jaguar | old | good=limit |

| | map-a | hah | βaɾi | wɨ́sti |

| | close-tr | yes | sun | one |

| | no-kí | his-má-ʔi | kiá |

| |

1pl:acc | see=caus-concur:ss | report |

| | kamáno | nokí | pi=kína |

| | jaguar |

1pl:acc | eat=concur:sa |

| | “So he kept it well, yes, and after one day the jaguar visited (saw) us to eat us.” 0181:0105 |

Chácobo has a highly infrequent subsequent dependent clause marked with =

noʂparí (there are only four examples in my corpus).

| 11. | hakiɾɨkɨ́ | naa | ka=ʔita=ʔá=ka | βaɾi |

| | then | dem.prox | go=recpst=nmlz:pst=rel | day |

| | no | ho=noʂparí | hawɨ́ | yonóko |

| | 1pl | come=subseq:ss/a |

3sg.gen | work |

| | mi | a=kɨ́ | tsi | ní |

| |

2sg | do=prior:ds/a | lnk | inter |

| | naa | no | ho=ita=ʔána | |

| | dem.prox |

1pl | come=recpst=nmlz:pst | |

| | “After this, yesterday, before we came, “what work did you do before arriving?” (he said)” 1865:0060 |

Same-subject and different-subject clauses can occur in chains. In the following example, a concurrent same-subject clause marked with =

ʔi “same-subject S/A concurrent” is embedded under a prior same-subject clause as in 12.

| 12. | βakíʃmaɾí | tsi | sani | a(k)=ʔi |

| | morning | lnk | fish | do=concur:ss |

| | tsi | kaɾo | a(k)=ʂó | hawɨniá |

| | lnk | lumber | do=prior:sa | what.time |

| | baɾí=no | kaɾá | ho=kí=a | tiá |

| | day=spatial | epis | come=decl:nonpst=1sg | epis |

| | “After getting lumber and fishing, what time/day will I come back.” 0243:0094–0095 |

The relation between dependent and main clause can also be aspectual. The morpheme

=pama “same-subject, interrupted” encodes that the event expressed by the dependent clause is interrupted by an event of the main clause. Examples are provided in 13 and 14 below.

| 13. | ka=páma | tsi | kiá | ʃinó | ha |

| | go=intrmp:ss/a | lnk | report | monkey |

3sg |

| | nika=ní=kɨ | | | |

| | hear=rempst=decl:pst | | | |

| | “As he was going (he stopped) and heard the monkey” |

| 14. | taʂaʔa(k)=βoná=pama | tsi | kiá | mai |

| | sweep=going:tr/pl=intrmp:ss/a | lnk | report | earth |

| | ha | ɾooʔa(k)=ní=kɨ | ɨɨ |

| |

3sg | fall.into.earth=rempst=decl:pst | ideo |

| | “As she started to sweep the floor, she fell through the ground and yelled ëë” 0638:0090 |

Chácobo also displays asyndetic clause conjunction (called asyndetic “coordination” in

Tallman (

2018b)). To the best of my knowledge, such an asyndetic clause linkage construction has not been described for any other Pano languages. The construction is typically used when the conjoined events display some parallelism, or even identity as in 15, respectively.

| 15 | ható | ʃina | βɨɨ | ható | ʃina |

| | 3pl:gen | soul | bring | 3pl:gen | soul |

| | bɨɨ | kiá | yoʃí | táʃi | i=pao=ní=kɨ |

| | bring | report | spirit | Tashi | aux=hab=rempast=decl:pst |

| | “He used to bring the spirits and brought the spirits.” 0783:0064 |

Asyndetic conjunction seems to be used to highlight the fast and perhaps planned succession of events acted out by the A/S participant. For instance, the following utterance comes from a story of a man who seeks to kill his in-laws by farting in their face after mixing his farts with tar—both actions (grabbing and coming) are performed purposefully and sequentially with the intent to kill via gastrointestinal gases.

| 16 | ʂɨto | atʃ-á | tsi | ho=ʔi | kiá |

| | pitch | grab-tr | lnk | come=c | report |

| | “He grabbed the tar and came (to fart in her face)” 0852:0076 |

As it will become relevant for the discussions below, I point out here that asyndetic clauses are somewhat hard to elicit. One often has to start with an instance of such clauses occurring in natural speech and then modify it to obtain elicitation judgments. This is perhaps due to the fact that I do not yet fully understand the semantics and/or pragmatics of these clauses.

There are two different subject clauses. Different subject clauses marked with =

kɨ́(no) code that an event occurs prior to the main clause. Switch reference clauses marked with = ́

no occur concurrently with the event of the main clause. Examples of the prior switch reference are provided in and 18 below.

6| 17. | hakirɨkɨ́ | toa | ha | pi=kɨ́ | tsi | kiá |

| | then | dem.dist |

3sg | eat=prior:ss/a | lnk | report |

| | ha | toa | ɨwati= ́ | yopa=ní=kɨ |

| |

3sg | dem.dist | gra.mo=erg | look.for.not.find=rempast=decl:past |

| | hawɨ́ | βakɨ́ | kamáno | … | toa |

| | 3sg.gen | child | jaguar | … | dem.prox |

| | kako= ́ | pi=ʔána | | |

| | Caco=erg | eat=nmd:past | | |

| | “And after he (Caco) ate him (his father), it is said that his gran mother looked for him and didn’t find him (Caco), nor the jaguar that Caco ate.” 0032:001 |

| 18. | tíma | há | wa=kɨ́ | tsi |

| | sound |

3sg | tr=prior:ds/a | lnk |

| | kia | há | ráya | ho=ní=kɨ |

| | report |

3sg | parrot | come=rempst=decl:pst |

| | “After he (the woodpecker) had been knocking (sounding), the parrot came.” 0780:0071 |

Examples of concurrent marked clauses are provided in.

7| 19. | háβi | tóka=ka | mai | kíni | oto |

| | surely | like.so=rel | earth | hole | cough |

| | oto | há | wa=no | tsi | kiá |

| | cough | 3 | tr=concur:ds/a | lnk | report |

| | hóni | wɨ́tsa | ho=ní=kɨ | |

| | man | other | come=rempast=decl:pst | |

| | “When they were coughing from the cave like this, another man arrived.” 0008:0110 |

Finally, there are dependent clauses which are not constrained with respect to whether they do or do not share an argument in common with the main clause. Clauses marked with =

ʔai(na) can be coreferential with the object or the subject of the main clause as in 20 and 21, respectively.

| 20. | a=βona=ʔái=ka | makína | tʃipatia=βona=ʔái=ka | kará | tóa |

| | do=going=nmlz=rel | machine | row=going=nmlz=rel | dub | dem:dist |

| | a(k)=pao=ní=kɨ | yamaβo= ́ | pápa |

| | kill=hab=rempast=decl:pst | dead=erg | father |

| | “While that one was rowing or going by motor (on the river), my father would kill him.” 0312:0334 |

| 21. | ʂáɾa=ka | ʂóβo | náa | paso=ní=kɨ | kiá |

| | inside=rel | house | dem:prox | be.slient=rempast=decl:pst | report |

| | nika=ʔáina | | | |

| | listen=nmlz:agt | | | |

| | “So the jaguar went silent listening to what was going on in the house” 0026:0019 |

There is a past tense

=ʔá(na) which is also unspecified with respect to whether it requires coreference with the subject of the main clause. It can be coreferential with the subject as in 22, or not as in 23.

| 22. | ima | ima=ʃina | ha | |

| | roast | roast=at.night | 3 | |

| | wa=ʔá=ka | káʂa=kɨ | kiá |

| | tr =nmd:ant=rel | angry=decl:pst | report |

| | yóʂa | | | | |

| | woman | | | | |

| | “After roasting it all night, the woman was angry (it is said)” 0483:0945 |

| 23. | ha | ho=ʔá=ka | yoanomano |

| | 3 | come =nmd:ant=rel | for.a.long.time |

| | ho=tɨkɨ́(n) | tsáka | =ní=kɨ | |

| | come=again | agouti | =rempast=decl:pst | |

| | “After he arrived, and then after a while, the agoutis came.” 0058:0032 |

Note that =

ʔái(na) and

=ʔá(na)-marked dependent clauses can modify noun phrases. In many cases, they are ambiguous between a noun-modifying and a predicate-modifying function (see

Guillaume 2011 for similar phenomena in Cavineña). This is illustrated in 24 and 25.

| 24. | yonoko=ʔái=ka | hɨnɨ | yoʂa= ́ | á(k)=kɨ |

| | work=nmlz=rel | chicha | woman=erg | make=decl:pst |

| | “The woman who is working made chicha.”/”While the woman was working, she made chicha.” |

| 25. | yonoko=ʔá=ka | hɨnɨ | yoʂa= ́ | á(k)=kɨ |

| | work=nmlz=rel | chicha | woman=erg | make=decl:pst |

| | “The woman who had worked made chicha.”/”After the woman worked, she made chicha.” |

There is a strong tendency for =

ʔá(na) and =

ʔái(na)-marked clauses to be predicates of non-verbal predicate constructions (

Tallman 2018b). When such clauses do occur in nonverbal predicate constructions, they also strongly tend to occur after the subject, contradicting the general trend for non-verbal predicate constructions that follow a predicate–subject order (

Tallman 2018b for details). Examples where the =

ʔái(na) and

=ʔá(na)-marked dependent clauses occur as predicates in non-verbal predicate constructions occur in 26 and 27.

| 26. | hati=roʔa=ka | noʔiria=bo | tsi | kiá | ho=yo=ʔáina |

| | all=limit=rel | people=pl | lnk | report | come=all=nmlz |

| | “All the people came.”/”The people were the ones who all came.” 0014:0187 |

| 27. | wɨ́tsa | tsi | kiá | naa | aka(n)=ita=ʔána |

| | other | lnk | report | dem.prox | be.killed=recpst=nmd:pst |

| | “This is the other one that was killed”/”This other one was killed.” 0056:0131 |

Dependent marked clauses marked with =

ʔái(na) can function as arguments of a verb. One could refer to such cases as headless relative clauses or simply claim that the clauses are nominalized themselves (

Shibatani 2019). Examples occur in 28 and 29. Dependent clauses marked with =

ʔá(na) cannot function as arguments of a verb (independent of a head noun that they modify).

| 28. | hatí=ɾoʔa | tʃani=kan=(ʔ)ai=βo | hoi | ha |

| | all=limit | speak=pl=nmlz=pl | speech | 3 |

| | bitʃ=(ʔ)i | kiá | | |

| | take=c | report | | |

| | “It grabs the speech, all that is spoken.” 2153:0409 |

| 29. | diezaño | ha | =ʔá=ka | ɨ-a=ɾí | kai=kí |

| | ten.year | 3 | =nmd:pst=rel | 1sg-epen=aug | mother=dat |

| | tsi | ka=kas=kí=a | i | kiá |

| | lnk | go=vol=decl:nonpast=1sg | say | report |

| | naa | rɨso=kan=(ʔ)ái=βo | ka=ʔai |

| | dem.prox | die=pl=nmlz=pl/assoc | go=nmlz |

| | kia=ʔái=ka=bo | | |

| | lie=nmlz=rel=pl/assoc | | |

| | “When they are 20 years of age “I want to go to my mother” they say, and these that are dead go and lie.” 0783:0031 |

Another type of clause-linkage device is marked with

=tí “purpose/instrumental nomalizer”, which codes a purpose clause. An example is provided in 30.

| 30. | toa | toʔotí | siɾi | ɨ | |

| | dem.dist | shot.gun | old |

1sg | |

| | bi=ní=kɨ | naa | roʔá | tsi |

| | grab=rempast =decl:pst | dem.prox | limit | lnk |

| | yona=kí=a | βikoβí | sani | a(k)=tí |

| | use =decl:nonpst=1sg | nail.arrow | fish | kill=nmlz:purp |

| | “I bought that old shot gun; I use this nail arrow to fish only.” 0903:0098 |

Dependent clauses marked with

=tí can also function as predicates in non-verbal predicate constructions as in 27.

| 31. | harí | náama | ʂo | mí | βana=ka(n)=tí |

| | again | already | decl |

2sg:gen | harvest=pl=nmlz:purp |

| | “It is already again time for your harvest.” 2153:0848 |

The marker also functions as an instrumental nominalizer. By “instrumental” I mean it creates a referent: “object is used for V”. Examples where

=tí-marked forms which have a referential function are provided in 32.

| 32. | hawɨ́ | tɨ-nɨʂ-ɨ=tí | pistia | tsi | kiá | ha |

| | 3sg:gen | neck-tie-itr=nmlz:purp | small | lnk | report | 3 |

| | tɨ-nɨʂ=ní=kɨ | | | | |

| | neck-tie-itr=rempst=decl:pst | | | | |

| | “He (Caco) tied his little scarf around his (the Kingfisher’s) neck.” 2119:0357 |

All dependent clauses in Chácobo require another clause to be present in the same sentence to occur—a clause which they are dependent to. However, this other clause needs not be a main clause, as I defined it above. Dependent clauses can be “co-dependent” with another dependent clause as in 33 and 34.

| 33. | βotɨ | ha | =wa=kɨ́ | tsi | naká |

| | go.down | 3 | =tr=prior:ds/a | lnk | chew |

| | naká | no | =wa=ʔána | | |

| | chew |

1pl | =tr=nmd:pst | | |

| | “When she went down, we had chewed everything (the yuca).” 1156:0091 |

| 34. | βaʔi= ́ | ʃita | ʃita=ʔái=ka | no |

| | road=spat | cross | cross=nmlz=rel |

1pl |

| | atʃ-a=ʔána | | |

| | grab-tr=nmd:pst | | |

| | “We grabbed it when it crossed the road.” 1157:0127 |

Based on the Chácobo data, I add “capacity to function referentially” and ability to modify nouns as another variable in the clause-linkage typology. These variables were not considered in

Bickel (

2010) but they are important for fully capturing variation in clause linkage, especially in a South American context (see the papers by

Zariquiey et al. 2019).

4. Parameters of Typological Variation in Chácobo-Dependent Clauses

This section applies diagnostics for the coordination–subordination distinction to the clause-linkage strategies of Chácobo. Most of these properties are described in the work of

Bickel (

2010). Some of these properties, or typological variables, are broken down further in order to account for the observed variation found in Chácobo. For instance, whether dependent clauses can have their own interrogative constituents depends on the part of speech of the constituent clause in question. Also, finiteness is not treated as a binary variable as it is in the work of

Bickel (

2010). Rather, I consider every TAAMME modification for which I have data.

As noted above, some elicitation data are used to fill gaps in my corpus or to provide negative evidence where necessary. To this end, I constructed a survey of elicitation questions designed to test all the relevant variables from Bickel. The original recordings for the data from naturalistic speech and the elicitation data can be found in the work of

Tallman (

2018b). The parameters are summarized in

Table 3 below.

Table 3 contains the variables from the work of

Bickel (

2010) and additional variables that I have added to this study. The new variables are marked off with “(new)” beside the name of the variables. The justification for adding such variables is provided throughout the description. I also code variables as they are found in Bickel as well, which allows me to contextualize the patterns with respect to Bickel’s data (see

Section 5). Note that, ideally, I would recode all of Bickel’s data according to the new variables I have added. This would follow autotypology methodology more faithfully (

Bickel and Nichols 2002). Unfortunately, I do not have the relevant data for these variables in all the languages of Bickel’s study. My goal in adding more variables is partially to provide a richer description of Chácobo, but also to encourage researchers to consider the new variables in their own descriptive studies, an issue that I return to in

Section 7.

An obvious example of a new variable I have in light of the evidence from Chácobo comes from the variable center-embed:pa. This refers to the possibility that a given dependent clause can be skipped over by a switch-reference marker. This variable may be very specific to Chácobo, or Pano languages, but its value for a given construction could be construed as evidence for subordinate or coordinate status for that construction and it good be seen as a sub-variable of Bickel’s layer. Center-embedding is plausibly more associated with subordination than with coordination. The other new variables Referential-function and Noun-modifying-function are more general. They are important to add in the context of South American languages, due to the tendency for many languages in the region to have constructions which can function as either noun modifiers or adverbial clauses. Other new variables are those that refer to the possibility of constituent interrogatives to function as arguments of or modify dependent clauses. This variable relates to both Wh and extraction.

4.1. Position in Relation to Main Clause

As

Bickel (

2010, p. 76) notes, the flexibility of the dependent clause in relation to the main clause is understood as an indicator of “subordinate” status. “Coordinate” or chained clauses are thought to occur in a more fixed order. In the generative literature, this criterion could be thought of following from the “Coordinate Structure Constraint” since it bans movement of conjuncts in coordinate structures, but not complex sentences with subordinate clauses (

Ross 1967, p. 161;

Weisser 2015, p. 11). All dependent clauses in Chácobo can occur on either side of the main clause except asyndetic conjunction, and the interrupted event =

pama clauses. Thus, with respect to the position variable, only the asyndetic conjunction and

=pama marked constructions are coordinate.

As noted above, some of the same/different subject markers display a different phonological form depending on whether they mark a clause that occurs after or before the main clause. The prior same subject clauses are realized as =

ʔáʂna and =

ʂóna rather than =

ʔáʂ and =

ʂó, respectively. Examples of the prior same-subject clauses occurring after the main clause, with their “long form” markers are provided in 35 and 36.

| 35. | haβa=ʔitá=kɨ | kiá | nika=ʔáʂna |

| | run=recpst=decl:pst | report | hear=prior:ss |

| | “He already escaped when he heard it.” 0841:0077 |

| 36. | ɨ | bi=ʔá=ka | ória=βo | ɨ́ | tʃokoʔa(k)=yamɨ́t=kɨ |

| |

1sg | grab=nmlz=rel | pot=pl |

1sg | clean=distpst=decl:pst |

| | hɨnɨ́ | páʂa | βi=yo=ʂóna |

| | water | raw/new | grab=cmpl=prior:sa |

| | “When I grabbed it, I washed the pots after gathering all the water.” 1156:0016 |

The prior-event different-subject clause is realized as

=kɨ́no rather than

=kɨ́ as in 37 below.

| 37. | no-ki=ti | tsi | hɨnɨ | a(k)=ki | no-a |

| | 1pl-dat=too | lnk | water | do=decl:nonpst |

1pl-epen |

| | ha | ka=kɨ́no | | |

| | 3 | go=prior:ds/a | | |

| | “When he goes, we make chicha.” 1840:0040 |

In asyndetic conjunction, the clauses cannot be reordered. Since there is no overt dependent marking, it is unclear which of the clauses should be regarded as dependent, but in any case, switching the order of the clauses is ungrammatical as in 39 below (the grammatical sentence on which this sentence is based is provided in 38.).

| 38. | ha-ʔ-ɨpa | yoa | ha-ʔ-ɨwa | tsaya | tsi |

| | 3-epen-father | tell | 3-epen-mother | see | lnk |

| | honi= ́ | =wa=ní=kɨ | | |

| | man=erg | =tr=rempst=decl:pst | | |

| | “The man told his father and visited his mother.” elic |

| 39. | *ha-ʔ-ɨwa | tsaya | tsi | honi= ́ | =wa=ní=kɨ |

| | 3-epen-mother | see | lnk | man=erg | =tr=rempst=decl:pst |

| | ha-ʔ-ɨpa | yoa | | |

| | 3-epen-father | tell | | |

| | “The man told his father and visited his mother.” elic |

On the other hand, reordering the conjuncts without moving the clause-type morpheme produces a difference in meaning. The conjuncts are therefore “tense iconic” in asyndetic clause linkage (see

Croft 2001).

I have no examples wherein the interrupting dependent clauses marked by =

pama occur after the main clause which they modify. Speakers also reject sentences where the =

pama-marked dependent clause occurs after the main clause as in 41 (40 is the correct formulation).

| 40. | naráha | raʂo=páma | ha | kɨɨsí=kɨ |

| | orange | peel=intrpt:ss/a | 3 | cut-intr=decl:pst |

| | “S/he was cutting the orange when he cut himself.” elic |

| 41. | *ha | kɨɨs-í=kɨ | naráha | raʂo=páma |

| | 3 | cut-intr=decl:pst | orange | peel= intrpt:ss/a |

| | “S/he was cutting the orange when he cut himself.” elic |

The values for the

position variable, which I have attempted to apply unmodified from the work of

Bickel (

2010), are provided in

Table 4.

4.2. Illocutionary (Interrogative) Marking and Scope (ILL-Marked, ILL-Scope)

Illocutionary force can be used as a criterion to distinguish coordination from subordinate clause-linkage. Clauses are more subordinate if they are not scoped over by illocutionary force and if they do not have illocutionary marking. An intermediate case is where illocutionary force scopes over both conjuncts but they cannot be each be marked by their own illocutionary force independently as in 42, referred to as cosubordination in some of the literature (

Foley and Van Valin 1984;

Good 2003, inter alia). The fact that 43 is not grammatical suggests that the relevant construction is cosubordinate to these authors.

- 42.

Jeff has already left for Wittenberg and should arrive there tomorrow.

- 43.

*Has Jeff already left for Wittenberg and should arrive there tomorrow?

Dependent clauses in Chácobo cannot have their own illocutionary marking independent of the main clause. However, an illocutionary marker of a main clause can scope over a dependent clause.

Bickel (

2010) described four possibilities with respect to illocutionary scope: (i)

local: the illocutionary operator scopes just over the main clause; (ii)

conjunct: the illocutionary operator scopes over the main and the dependent clause; (iii)

extensible: the illocutionary operator extends over the main clause or the main clause and the dependent clause, but never just the dependent clause; (iv)

disjunct: the illocutionary operator extends to either the main or the dependent clause but never both.

Data from elicitation reveal that all interrogative operators are

extensible across all dependent clauses in Chácobo except the “nominalized purpose/instrumental” clause marked by

=tí and the interruptive same-subject clause marked by =

páma. An illustration of the extensible character of interrogatives with dependent clauses is provided in 44. The interrogative marker scopes over just the main clause or the main clause and the dependent clause. The interpretation whereby the illocutionary operator scopes over both the dependent and main clause does not appear to be particularly common in naturalistic speech. Note that one knows that an extensible interpretation is possible nevertheless, because 45 and 46 are both permissible answers to the question in 44. From this point on, I will not include the permissible answers and assume that extensibility can be read off the alternative translations.

| 44. | tʃaʃo | pi=ʔi | tsi | hɨɾɨ=yá | tʃani=kan=ʔá |

| | pig | eat=concur:ss | lnk | Gere=com | speak=3pl=inter:past |

| | “While they were eating did they speak with Gere?”/”Were they eating pig and did they speak with Gere?” |

| 45. | hɨɾɨ=yá | tʃani=kɑ(n)=yáma=kɨ | hama | tʃatʃo |

| | Gere=com | speak=3pl=neg=decl:pst | but | pig |

| | pi=ká(n)=kɨ | | |

| | eat=3pl=rempst=decl:pst | | |

| | “They did not speak with Gere, but they did eat pig.” |

| 46. | tʃatʃo | pi=ká(n)=yáma=kɨ | hama | hɨɾɨ=yá |

| | pig | eat=3pl=rempast=decl:pst | but | Gere=com |

| | tʃani=ká(n)=kɨ | | |

| | speak=3pl=neg=decl:pst | | |

| | “They did not speak with Gere, but they did eat pig.” |

Extensible interpretations are also found with prior same-subject clauses and different subject clauses as in 47, 48, and 49.

| 47. | tʃaʃo | pi=ʔáʂ | tsi | hɨɾɨ=yá | tʃani=kan=ʔá |

| | pig | eat=prior:ss | lnk | Gere=com | speak=3pl=inter:pst |

| | “Did they speak with Gere after eating pig?”/

“Did they speak with Gere, and did they eat pig?” |

| 48. | tʃaʃo | pi=ʂó | tsi | hɨɾɨ | honi=βá |

| | pig | eat=prior:ss | lnk | Gere | man=pl:erg |

| | tsaya=ʔá | | | |

| | see=inter:pst | | | |

| | “Did the men see Gere after eating pig?”/

“Did they eat pig and see Gere?” |

| 49. | honi= ́ | ɾaʃa=kɨ́=ɾoʔá | tsi | ina |

| | man=erg | hit=prior:ds/a=limit | lnk | dog |

| | ɾɨso=ʔá | | | |

| | die=inter:pst | | | |

| | “Right after the man hit the dog, did it die?/Did the man hit the dog and did it die?” |

The same pattern applies to all dependent clauses except the interruptive clause and the purposive clause. The purposive clause does not display extensibility with respect to interrogatives, as is shown in 50. Rather, the interrogative only scopes over the main clause and the information in the

=tí-marked clause is presupposed. Thus, with this clause the scope property is local, rather than extensible.

| 50. | ʂoβo | a(k)=tí | karo | kɨɨs-a=ʔaí |

| | house | make=nmlz:purp | lumber | cut-tr=inter:2sg |

| | “Are you gathering lumber to build a house.”

“*Are you building a house and are you gathering lumber?” |

Thus, most dependent clauses in Chácobo pattern somewhat like cosubordination in that interrogative force scopes over them. But they are not like cosubordination in that they can also have an interpretation where the illocutionary operator does not scope over them. The instrumental nominalizer and the same-subject interruptive clause behave most like a subordinate clause in this respect as they can only display local scope. For the same-subject interruptive clause, this may be somewhat problematic because it patterns more like a coordinate clause with respect to the position variable.

The results for the

ill-scope and

ill-mark variables are provided in

Table 5. These variables are adopted from

Bickel (

2010) without modification.

4.3. Negative Marking and Scope (NEG-Marked, NEG-Scope)

In contrast to illocutionary marking, in Chácobo, negation can be marked in all dependent clauses. Despite this difference, similar questions about illocutionary scope can also be asked of negation. In Chácobo, all dependent clauses can be marked with negation, although it is not common in naturalistic speech. Some illustrative examples are provided in 51 with the purposive clause and in 52 with a same-subject clause.

| 51. | tʃani=yáma=tí | haβá=kɨ | hɨ́ɾɨ | | |

| | speak=neg=nmlz:purp | run=decl:pst | Gere | | |

| | “Gere ran away so he wouldn’t have to speak.” ptcp obsv |

| 52. | moʔi=yámɑ=ʔi | waaʂá=ki | honi |

| | move=neg=concur:ss | paddle=decl:nonpst | man |

| | “He is paddling without moving.” ptcp obsv |

Whether negative marking is extensible or local depends on which dependent clause is involved. Asyndetic conjunction and all same-subject clauses are extensible with respect to negation. This means that, when the negative marker occurs in the main clause, the negation can have a strictly local interpretation (modifying the event of the main clause) or display scope over the main and the same-subject clause, as in 53 below.

| 53. | ʂoβo=kí | kaʔɨ=ʔi | tsi | honi | |

| | house=dat | arrive=concur:ss | lnk | man | |

| | tsaʔo=yáma=kɨ | | | | |

| | sit=neg=decl:pst | | | | |

| | “When the man arrived at this house, he didn’t sit down.”

“The man did not arrive at his house, nor did he sit down.” |

However, the interpretation of the negation modification must be local when the dependent clause is a different subject clause.

| 54. | ʂoβo=kí | yoʂa | kaʔɨ=kɨ́ | tsi | honi= ́ |

| | house=dat | woman | arrive=prior:ds/a | lnk | man=erg |

| | tsaya=yáma=kɨ | | | |

| | see=neg=decl:pst | | | |

| | “When the woman arrived at the house, the man did not see her.”

*”The woman did not arrive at the house and the man did not see her.” |

In contrast to same/different-subject clauses, nominalized clauses marked with =

ʔái(na) require negation to be interpreted locally. That is, if a main clause is marked with the negative =

yáma, the negative scopes over the main clause and not the imperfective clause, as illustrated in 55.

| 55. | yonoko=ʔái=ka | yoʂa= ́ | hɨnɨ | a(k)=yáma=kɨ |

| | work=nmlz=rel | woman=erg | chicha | make=neg=decl:pst |

| | “As the woman worked, she made did not make chicha.”

“*The woman neither worked, nor made chicha.” |

This is not true of the nominal-modifying clause marked with =

ʔá(na), as illustrated in 56 below. Clauses marked with this marker are extensible with respect to negation marking.

| 56. | yonoko=ʔá=ka | yoʂa= ́ | hɨnɨ | a(k)=yáma=kɨ |

| | work=nmd:ant=rel | woman=erg | chicha | make=neg=decl:pst |

| | “After the woman worked, she didn’t make the chicha.”

“The woman neither worked, nor made chicha.” |

Thus, in Chácobo, all same-subject clauses display extensibility with respect to negation. This also includes asyndetic conjunction. This means that the negative marker can have a local or wide scope interpretation. However, with different subject clauses, the negation only has local scope. Finally, nominalized clauses display extensible scope. Different subject clauses would appear to be the most subordinate-like according to negative scope.

Table 6 summarizes the results of applying diagnostics based on negation.

4.4. Constituent Interrogatives (WH)

One of the criteria

Bickel (

2010) uses is whether a dependent clause can host a constituent interrogative. In Chácobo, research thus far suggests that all constituent interrogatives are fronted.

8 Furthermore, one cannot have a sentence with two constituent interrogatives of the same type even when one could, in principle, be licensed by a dependent clause. This is illustrated with the ungrammatical sentences in 57 and 58. The ability for another interrogative constituent to occur when one of the dependent clauses is present has been tested with all the dependent clauses.

| 57. | *tsowɨ | tsowɨ | tsaya | awini= ́ | =wa=kɨ́ |

| | who | who | see | woman=erg | =tr=prior:ds/a |

| | tsi | taʃi= ́ | raaʔak | =ʔá | |

| | link | Tashi=erg | scold | =inter:pst | |

| | Intended: “Who did the woman see and (after) who did Tashi scold?” |

| 58. | *tsowɨ | awini= ́ | tsaya | wa=kɨ́ | tsi |

| | who | woman=erg | see | tr=prior:ds/a | lnk |

| | tsowɨ | taʃi = ́ | ɾaaʔak=ʔá | |

| | who | Tashi=erg | scold=inter:pst | |

| | Intended: “Who did the woman see and (after) who did Tashi scold?” |

4.5. Information Structure Positions and Markers (FOC)

Bickel (

2010) describes having a focus position and being able to have a focus marker as potentially independent variable. However, testing for “focus” as a typologically consistent variable is made difficult by the fact that there is no cross-linguistically agreed-upon definition of focus: that is, the notions “focus” and “topic” can be similarly broken down into a number of distinct senses, uses, or “variables” (

Ozerov 2018,

2021).

It is outside the scope of this paper to attempt to integrate a typology of information structure categories into clause-linkage typology. Instead, I will refer to a variable that refers to positions that have information structural definitions. The clause-initial position in Chácobo has a number of functions. It is used for contrastive focus and in answer to questions for NPs, but is also associated with givenness, especially with verbs (

Tallman 2018a). In Chácobo, this position is marked off by having the Wackernagel-like morpheme

tsi occur before it, referred to as “position 5 morph” in

Tallman (

2018a) and glossed as “linker” here (for more examples, see

Tallman (

2018a)).

A contrastive focus-like function of this initial, prior to

tsi, position is provided in 59. The noun phrase

hawɨ roʔá “his large vulture” is in a position before

tsi and has a contrastive focus function in the following example.

| 59. | hawɨ | roʔá | tsi | kiá | kaʔɨ=ʂɨni |

| |

3sg:gen | large.vulture | lnk | report | know=v>adjlz |

| | hama | kiá | hawɨ | siyaβi | … |

| | but | report | 3sg:gen | Siyabi | … |

| | hawɨ́ | roʔá | tsi | kiá | |

| |

3sg:gen | large.vulture | lnk | report | |

| | βotɨ=ní=kɨ | | |

| | descend=rempst=decl:pst | | |

| | “His (Mabocorihua’s) large vulture knew, but not his siyabi… then it was his large vulture that descended.” 00063:0155–0157 |

The question which is relevant for clause-linkage typology is whether this focus/topic position can be projected in dependent clauses. That is, can dependent clauses have a “first position” before

tsi independent from the main clause? Chácobo-dependent clauses appear to be able to contain this pre-

tsi first position. Evidence for this is that

tsi can occur more than when in clause-linkage constructions with same-subject clauses as in (60), (61), and (62).

| 60. | hama | kako= ́ | tsi | kiá | toa |

| | but | Caco=erg | lnk | report | dem:dist |

| | kamano= ́ | βɨ́ɾo | moto | toka=ta(n)=ʂó |

| | jaguar=gen | eye | chive | do.so=go&do=prior:sa |

| | tsi | kamano= ́ | βɨ́ɾo | hana=kí | |

| | lnk | jaguar=gen | eye | mouth=dat | |

| | toa=ní=kɨ | | | |

| | explode=rempst=decl:pst | | | |

| | “But when Caco did so with the jaguar’s eye and chive, the jaguar’s eye exploded in his mouth.” 0181:0164 |

| 61. | ʂoβo | ak=(ʔ)á | tsi | tana | |

| | house | do=prior:ss | lnk | distance | |

| | raka-na=tan=i | ható | ɨwatí | βi=mitsa |

| | stay-intrc=go&do=concur:ss |

3pl:gen | gra.mo | recieve=psbl |

| | natani=βayá | tsi | ʂoβo | a(k)=βayá |

| | pass.by=do&go:tr/pl | lnk | house | do=do&go:tr/pl |

| | tsi | ʂoβo | a(k) =βayá | tsi |

| | lnk | house | do=do&go:tr/pl | lnk |

| | kiá | ha | βo=kan=ní=kɨ |

| | report |

3

| go=pl=rempst=decl:pst |

| | “When they made the house, they stayed there for just one week and then right after their grandmother could have recieved them, they passed by, they made the house, and they left.” 0181:0220 |

| 62. | tana | tsi | hoi-ko | =pama |

| | distance | lnk | get.up-distr | =intrmp:ss/a |

| | tsi | kiá | yáma | tsi | ʂo |

| | lnk | report | neg | lnk | decl |

| | “After he got up “there is nothing” (he said)” 0181:0090 |

Different subject clauses can also contain the marker

tsi in them as in 63.

| 63. | ha | ak=(ʔ)á=ka | wɨakɨ́ | tsi |

| |

3sg | do=nmd:ant=rel | after.day | lnk |

| | hɨnɨ | no | ak=(ʔ)á=ka | toʔo-ko |

| | chicha |

1pl | do=nmd:ant=rel | stir-distr |

| | ha | =kɨ́ | tsi | wɨakɨ́ | wai=kí |

| |

3

| =prior:ds/a | lnk | after.day | garden=dat |

| | ká=ki | noa | toka | tsi |

| | go=decl:nonpst |

1pl | do.so | lnk |

| | ha=βɨta | ká=ʔi | ɨ | i=pao=ní=kɨ |

| |

3=com | go=concur:s |

1sg | do =hab=rempst=decl:pst |

| | “When she did it, the day after we made the chicha, after she stirred it, the day after we go to the garden with her.” 1840:0041 |

The initial position is also present in nominalized clauses marked with =

ʔái(na), as in 64.

| 64. | toa | ɨ | haβi=ʔái=ka | tsi | piʃa |

| | dem:dist |

1sg | learn=nmlz=rel | lnk | little |

| | ɨ | ina=kanɑ=ʔái | tsi | ʂo |

| |

1sg | ascend=going:itr=nmlz | lnk | decl |

| | toa | haʔiki … | noʔó | naama |

| | dem:dist | then … |

1sg:gen | dream |

| | tsi | ʂo | toa | toa | haska |

| | lnk | decl | dem:dist | dem:dist | same |

| | =kato | | | | |

| | =rel | | | | |

| | “When I was learning, I got better and better, then something like my dream will be.” 1840:0133 |

The nominal-modifying clause marked with =ʔá(na) and the purpose-nominalized clause marked with =tí do not appear with tsi in them. Based on this, I assume that the first position is not available to these clauses.

The results of the informational structural variable are reported in

Table 7. The results may not be comparable to the data in the work of

Bickel (

2010). However, this is because the concept of

focus is not comparable. Thus, I have replaced the variable with something which is marked in Chácobo grammar which I consider to be relevant to the coordination–subordination distinction.

4.6. Asymmetric Extraction of NP Constituent Interrogatives (WH-NP-EXT)

Extraction may be considered a classical test for distinguishing between coordination and subordination. In coordinate clauses, no elements from either of the conjuncts can be extracted asymmetrically (from one conjunct and not the other) (

Ross 1967;

Levine 2009;

Weisser 2015;

Bošković 2020), while “across-the-board” extraction is indicative of coordinative status.

9 One of the ways this diagnostic has been used is with the extraction of interrogative constituents. To simplify matters, I will only refer to the extraction of interrogative constituents. Future research will be concerned with assessing extraction in other types of contexts (e.g., right dislocation, adverb extraction).

The issue of extraction presented in

Bickel (

2010) is simplified compared to the number of variables and values relevant for capturing potential cross-linguistic variation.

Bickel (

2010) only has a single binary-variable

extraction. However, a distinction needs to be made between the (i) type of element being abstracted, as noted above; (ii) the status of the clause of the extraction site (main or dependent); (iii) whether the extraction site is local to the landing site.

In order to bring some order to these possibilities, I first make a distinction between noun phrase and adverbial phrase extraction (WH-NP vs. WH-Adv), with the latter being discussed in

Section 4.7. Then, these variables are split up further according to whether we are dealing with extraction from the marked-dependent clause or the main clause (WH-NP-MAIN vs. WH-NP-DEP; WH-Adv-MAIN vs. WH-Adv-DEP). Finally, each of these variables can take three values: (i)

ok: extraction of the NP/AdvP interrogative constituent is always allowed; (ii)

local: extraction of the NP/AdvP interrogative constituent is only allowed when the extraction site and the landing site are not interrupted from each other by more than one clause boundary (see

Section 4 above for a similar formulation); (iii)

banned: Extraction of the NP/AdvP interrogative constituent is not allowed. Cases where extraction can occur

only non-locally do not occur and thus this is not specified as one the potential values.

There are additional caveats and complications involved in interpreting asymmetric extraction of NP constituents in Chácobo. These are discussed in

Appendix A (

Appendix A.1).

Non-locally, NP constituent interrogatives cannot be extracted from a same-subject clause. If the same subject clause is on the right-side of the main clause, then the fronting cannot occur as illustrated by the ungrammaticality of the following examples.

| 65. | *hawɨi | kako= ́ | oʂa=ʔá | ___i | kopi=ʔáʂna |

| | whati | Caco=erg | sleep=inter:pst | ___i | buy=prior:sa |

| | “What did Caco buy and then slept?” |

| 66. | *hawɨi | kako | oʂa=ʔá | ___i | ʃiná=ʔina | |

| | whati | Caco | buy=inter:past | ___i | think=concur:ss | |

| | “What did Caco think about when he slept?” |

Extraction of constituent NPs from main clauses is permitted whether such extraction is non-local or not in a same-subject construction. This is illustrated in 67 and 68.

| 67. | hawɨi | hawɨ | ʂoβo | =ki | ho =ʂó | kako= ́ |

| | whati | 3sg:gen | house | =dat | arrive=prior:sa | Caco=erg |

| | ___i | kopi=ʔá | | | |

| | ___i | buy=inter:pst | | | |

| | “What did Caco think about when he slept?” |

| 68. | hawɨ | tsi | aʃi=kí | βoka= ́ | ___i | kopi=ʔá |

| | what | lnk | bathe=concur:sa | Boca=erg | ___i | buy=inter:pst |

| | “What while/before bathing did Boca buy?” |

For =

páma “interruptive”-marked clauses, non-local extraction out of its main clause is not allowed, however, as illustrated by the ungrammaticality of the example below.

| 69. | *hawɨi | ka=pama | tsi | kiá | ha | ___i | nika=ʔá |

| | whati | go=intrmp:s/a | lnk | report |

3

| ___i | listen=inter:pst |

| | Intended: “What while going did he hear?” |

Asyndetic same-subject clauses can display asymmetric extraction as in 70.

| 70. | tsowɨi | ___i | atʃ-a | hawɨ | taʔɨ | nɨʂ-a | |

| | whoi | ___i | grab-tr |

3sg:gen | foot | tie-tr | |

| | honi= ́ | =wɑ | =ʔá | | | |

| | man=erg | =tr | =inter:pst | | | |

| | Intended: “Who did the man grab and grab his foot?” |

Note that asyndetic same-subject clauses display a fixed position (

Section 4.1), which suggests that they are coordination constructions. However, they also allow for asymmetric extraction, as in the example above. A researcher who is dedicated to the coordination–subordination distinction will have to discard the position diagnostic

just so and claim that the clause is fact subordination, or state that this construction violates the coordinate-structure-constraint (

Hofmeister and Sag 2010 for relevant discussion).

Different-subject clause constructions marked with =

kɨ́ “prior” or = ̌

no “concurrent” appear to be more permissive with the extraction of noun phrase constituents. As with

=ʔáʂ(na)~=ʂó(na) and =

ʔi(na)~=kí(na) same-subject clauses, non-local extraction is permitted out of a main clause. In contrast to same-subject clauses, they appear to allow for non-local extraction from a dependent clause.

| 71. | hawɨi | kaɾá | ka | honi= ́ | kamá | tʃoiʃ-á=kɨ́ | tsi |

| | whati | epis | rel | man=erg | jaguar | shoot.at-tr=prior:ds/a | lnk |

| | ___i | haβá=ʔá | | | |

| | ___i | run=inter:pst | | | |

| | “What ever did Caco think about when he slept?” | |

| 72. | hawɨi | hawɨ́ | βakɨ́ | pistia | haβa=ʔá | honí | ___i |

| | whati |

3sg:gen | child | small | run=inter:pst | man=erg | ___i |

| | tʃoiʃ-a=kɨ́na | | | | |

| | shoot.at-tr=prior:d/sa | | | | |

| | “What did Caco shoot and then its child escaped?” |

Nominalized and noun-modifying clause constructions likewise both allow for extraction either locally or non-locall (Note, however, there is problem in interpretation of this example related to the potential presene of a null resumptive pronoun, see

Appendix A.1).

| 73. | hawɨ | kará | kai | tsi | yoʂá | hawɨ́ |

| | what | dub | reli | lnk | woman=erg |

3sg:gen |

| | haʔíni | =yá | tʃani=ʔá | ___i | a(k)=áina |

| | girl | =com | speak=inter:pst | ___i | make=nmlz |

| | “What ever was she making while she talked to her daughter?”

(“Whati was the woman who making iti talked to her daughter?”) |

Nominalizing purpose/instrumental clauses, however, cannot have NP-constituent interrogatives extracted out of them. For instance, the following is not grammatical in Chácobo according to the speakers I asked:

| 74. | ??hawɨi | ɾiberalta=kí | ha | ka=ʔá | ___i | kopi=tí |

| | ??whati | Riberalta=dat |

3sg | go=inter:pst | ___i | buy=nmlz:purp |

| | “What did he go to Riberalta to buy?” |

The full results of applying asymmetric extraction to each of the clause-linkage constructions are summarized in

Table 8.

4.7. Asymmetric Extraction of AdvP Constituent Interrogatives (WH-ADV-EXT)

In same-subject clause constructions, adverbial constituent interrogatives can be asymmetrically extracted from same-subject and main clauses in local and non-local contexts. One can see that, when the main clause is final, a fronted adverbial constituent can modify either a local same-subject clause or the main clause. Interpreted in terms of extraction, the interrogative constituent can be extracted from the same-subject clause or the main clause as in 75 and 76.

| 75. | hawɨniai | hɨnɨ | ak=(ʔ)aʂ | ___i | kako | tsaʔo=ʔá |

| | wherei | chicha | drink=prior:ss | ___i | Caco | sit=inter:pst |

| | “Where, after he drank chicha, did Caco sit?” |

| 76. | hawɨniai | ___i | hɨnɨ | ak=(ʔ)aʂ | kako | tsaʔo=ʔá |

| | wherei | ___i | chicha | drink=prior:ss | Caco | sit=inter:pst |

| | “Where did Caco drink chicha and then sit?” |

The adverbial interrogative constituent can be extracted from a local main clause as in 77 or a non-local same-subject clause as in 78.

| 77. | hawɨniai | kako | tsaʔo=ʔá | ___i | hɨnɨ | ak=(ʔ)aʂna |

| | wherei | Caco | sit=inter:pst | ___i | chicha | drink=prior:ss |

| | “Where did Caco drink and then sit?” |

| 78. | hawɨniai | ___i | kako | tsaʔo=ʔá | hɨnɨ | ak=(ʔ)aʂna |

| | wherei | ___i | Caco | sit=inter:pst | chicha | drink=prior:ss |

| | “Where did Caco drink before he sat?” |

There appear to be no constraints on the extraction of adverbial constituents from prior and concurrent same-subject clauses.

Same-subject clauses marked with the interruptive

=pama ban non-local extraction, even of adverbial constituents. The basic facts are illustrated in 79 and 80.

| 79. | hawɨʂoβai | ___i | hɨnɨ | a(k)=pama | tsi | ʃinó |

| | with.whati | ___i | chicha | do= intrmp:ss/a | lnk | monkey |

| | ha | nika | =ʔá | | |

| |

3sg | listen | =inter:pst | | |

| | “With what was he drinking chicha, when he heard the monkey?” |

| 80. | *hawɨʂoβai | hɨnɨ | a(k)=pama | tsi | ___i | ʃinó |

| | with.whati | water | do=intrmp:ss/a | lnk | ___i | monkey |

| | ha | nika | =ʔá | | |

| |

3sg | listen | =inter:pst | | |

| | “With what, while he was drinking chicha, did he hear the money?” |

Different-subject constructions marked with =

kɨ́(na) “prior different A/S” or = “

no concurrent different A/S” allow for all types of adverbial extraction. An example of local extraction of an adverbial constituent interrogative is provided in 81. An example of non-local extraction of an adverbial constituent interrogative from a different subject clause is provided in 82.

| 81. | hɨni=ʂói | ___i | hawɨ́ | βakɨ́ | pistia | haβa |

| | how=sai | ___i |

3sg:gen | child | small | run |

| | =kɨ | honi= ́ | kamá | tʃoiʃ-a | =kɨ́na |

| | =decl:pst | man=erg | jaguar | shoot-tr | =prior:ds/a |

| | “Why did hisj child escape when the man shot the jaguarj?” |

| 82. | hɨni=ʂói | hawɨ́ | βakɨ́ | pistia | haβa | =kɨ |

| | how=sai |

3sg:gen | child | small | run | =decl:pst |

| | ___i | honi = ́ | kamá | tʃoiʃ-a | =kɨ́na |

| | ___i | man=erg | jaguar | shoot-tr | =prior:ds/a |

| | “Why, when hisj child escape, did the man shoot the jaguarj.?” |

For clause-linkage with nominalized clauses, all extraction possibilities are available when the extracted constituent interrogative is an adverbial clause. This is illustrated in 83 through 86.

| 83. | hawɨniai | ___i | hɨnɨ | ak | =(ʔ)ái=ka |

| | wherei | ___i | chicha | make | =nmlz =rel |

| | yoʂa= ́ | hawɨ́ | haʔíni | =yá | tʃani=ʔá |

| | woman=erg | 3sg:gen | girl | =comit | speak=inter:pst |

| | “Where was she making chicha when the woman spoke to her daughter?” |

| 84. | hawɨniai | hɨnɨ | ak | =(ʔ)ái=ka | ___i |

| | wherei | chicha | make | =nmlz =rel | ___i |

| | yoʂa= ́ | hawɨ́ | haʔíni | =yá | tʃani=ʔá |

| | woman=erg | 3sg:gen | girl | =comit | speak=inter:pst |

| | “Where, when she was making chicha, did the woman speak to her daughter?” |

| 85. | hɨni=ʂói | ___i | yoʂa= ́ | hawɨ́ | haʔíni | =yá |

| | why=pai | ___i | woman=erg |

3sg:gen | girl | =comit |

| | tʃani | =kɨ | hɨnɨ | ak | =ʔáina | |

| | speak | =decl:pst | chicha | make | =nmlz | |

| | “Why did the woman speak with her daughter while she made chicha.” |

| 86. | hɨni=ʂói | yoʂa= ́ | hawɨ́ | haʔíni | =yá | tʃani |

| | why=pai | woman=erg |

3sg:gen | girl | =comit | speak |

| | =kɨ | ___i | hɨnɨ | ak | =ʔáina | |

| | =decl:pst | ___i | chicha | make | =nmlz | |

| | “Why, while the woman spoke with her daughter, was she making chicha?” |

As far as I have been able to discern, one cannot extract adverbial constituent interrogatives from purpose clauses. Evidence for this is provided in 87 and 88.

| 87. | hɨni=ʂó | pila | kopi | =tí | yonoko | =ʔá |

| | why | battery | buy | =nmlz:purp | work | =inter:pst |

| | “Why did s/he work to buy batteries?”??”Why after working did/she buy batteries?” |

| 88. | hɨni=ʂó | yonoko | =ʔá | pila | kopi | =tí |

| | why | battery | =inter:pst | battery | buy | =nmlz:purp |

| | “Why did s/he work” to buy batteries?”

??”Why after working did/she buy batteries?” |

The values of the adverbial constituent interrogative extraction variable are summarized in

Table 9.

As stated above, the

extraction variable of Bickel only codes whether any extraction can occur out of a dependent clause, as I understand him. However, the literature reports differences in extraction from main or dependent clauses and differences in the extraction of core and adverbial arguments (

Hofmeister and Sag 2010, inter alia), and in Chácobo there appears to be a difference. I, therefore, suggest that the variable may be worth expanding on in this paper.

4.8. Center-Embedding via Ergative Case Marking (Layer of Attachment)

Bickel (

2010) describes a variable that he calls “layer of attachment”, making a distinction between clauses that adjoin to the predicate (ad-V), clauses that adjoin to the sentence (ad-S and clauses that adjoin to “some higher level and appear “detached” from the main clauses…” (

Bickel 2010, p. 77)).

The main criterion for distinguishing between ad-V and ad-S is whether a dependent clause can appear center-embedded vis-à-vis a main verb. In Chácobo, ergative marking cannot skip over a dependent clause. An ergative case must be assigned locally. This is shown in 89 and 90.

| 89. | yonoko | =ʂó | tsi | ano | tɨpas |

| | work | =prior:sa | lnk | paca | murder |

| | taʃi= ́ | wa | =kɨ | |

| | Tashi=erg | tr | =decl:pst | |

| | “After working, Tashi killed the paca.” |

| 90. | *taʃi = ́ | yonoko | =ʂó | tsi | ano |

| | Tashi =erg | work | =prior:sa | lnk | paca |

| | tɨpas | =kɨ | | | |

| | murder | =decl:past | | | |

| | “After working, Tashi killed the paca.” |

I have no obvious cases wherein case marking from the main clause skips over a dependent clause. On this basis, all dependent clauses are classified as Ad-S. The problem with such a classification, however, is that, if we look at participant agreement, we arrive at the opposite result.

4.9. Center-Embedding via Participant Agreement

A clause which could be argued to be center-embedded could be argued to be subordinate. In Chácobo, there is a type of center-embedding that can occur when there are adjacent same-subject clauses. An example is provided in 91. In this example,

tsaʔo=ʂó could be argued to be center-embedded because the participant agreement marking of the previous clause skips over it and agrees with the transitivity of the main clause. In elicitation contexts, speakers find cases with no such agreement skipping preferable, as in 92.

| 91. | ?kaʔɨ=ʂó | tsaʔo=ʂó | tsi | honi= ́ | tsáya=kɨ |

| | arrive=prior:sa | sit=prior:sa | lnk | man=erg | see=decl:pst |

| | “The man arrived and then sat down and looked at them.” |

| 92. | kaʔɨ=ʔáʂ | tsaʔo=ʂó | tsi | honi= ́ | tsáya =kɨ |

| | arrive=prior:ss | sit=prior:sa | lnk | man=erg | see=decl:pst |

| | “The man arrived and then sat down and looked at them.” |

In Chácobo, the most common pattern is for a same-subject clause to agree with the clause directly to its right (or left for those clauses which occur after the clause-type morpheme of the main clause), regardless of whether this clause is dependent or not. Examples are provided in 93 and 94 below.

| 93. | toa | oʂa=kí | orikití | piʃa |

| | dem:dist | sleep=concur:a | food | a.little |

| | ma | βo=ʔá=ka | βɨtɨ=ʂó |

| |

2pl | bring=nmd:ant=rel | cook=prior:sa |

| | pi=ʔi | ma | ʔi=ní |

| | eat=concur:s |

2pl | aux.intr=inter:rempast |

| | “After sleeping, there you brought a little food, after cooking it you ate it?”

1851:0032 |

| 94. | pápi | há | a=ita=ʔáʂ | tsi |

| | paper | 3 | make=recpast=prior:ss | lnk |

| | kiá | ka=ʂó | há | hana=ní=kɨ |

| | report | go=prior:sa |

3

| leave=rempast=decl:pst |

| | “After he had made the paper, and after he went, he left it.” 2119: 368 |

There are a few attested cases of agreement which appear to skip over a right adjacent same-subject clause in natural speech. Examples are provided in 95 and 96. In 95, the dependent clause

aʃi=ʂó “after bathing” is intransitive. However, the same-subject clause before it,

nia=ʂó “after throwing it away”, takes a same subject clause which agrees with a transitive clause (

kɨɨsakaʂɨkawɨ́ ‘cut it’). This example thus shows that prior same-subject clauses can be center-embedded according to participant agreement. Another example is provided in 96 below.

| 95. | ma-to | ʃapokotí | nia=ʂó | tsi |

| |

2pl-acc | traditional.belt | throw =prior:sa | lnk |

| | aʃi=ʂó | tsi | naa | tsi |

| | bathe=prior:sa | lnk | dem.prox | lnk |

| | kɨ́ɨs-a=ká(n)=ʂɨ=ka(n)=wɨ́ | … | tiaroʔa | |

| | cut-tr=pl=fut=pl=imper | … | size=limit | |

| | “Put this on, throw away your shapocoti, bathe yourself and cut (your skirts) to this size.” (this is what Cai Mariana said) 0146:0153 |

| 96. | bi=ʂó | tsi | naa | ho=ʂó | mia-rí |

| | get=prior:sa | lnk | dem:prox | come=prior:sa | 2sg-too |

| | a=ita=ʔána | | | |

| | drink=recpast=nmd:ant | | | |

| | “After getting it (chicha), after arriving, you drank it (chicha) as well.” 1840:0096 |

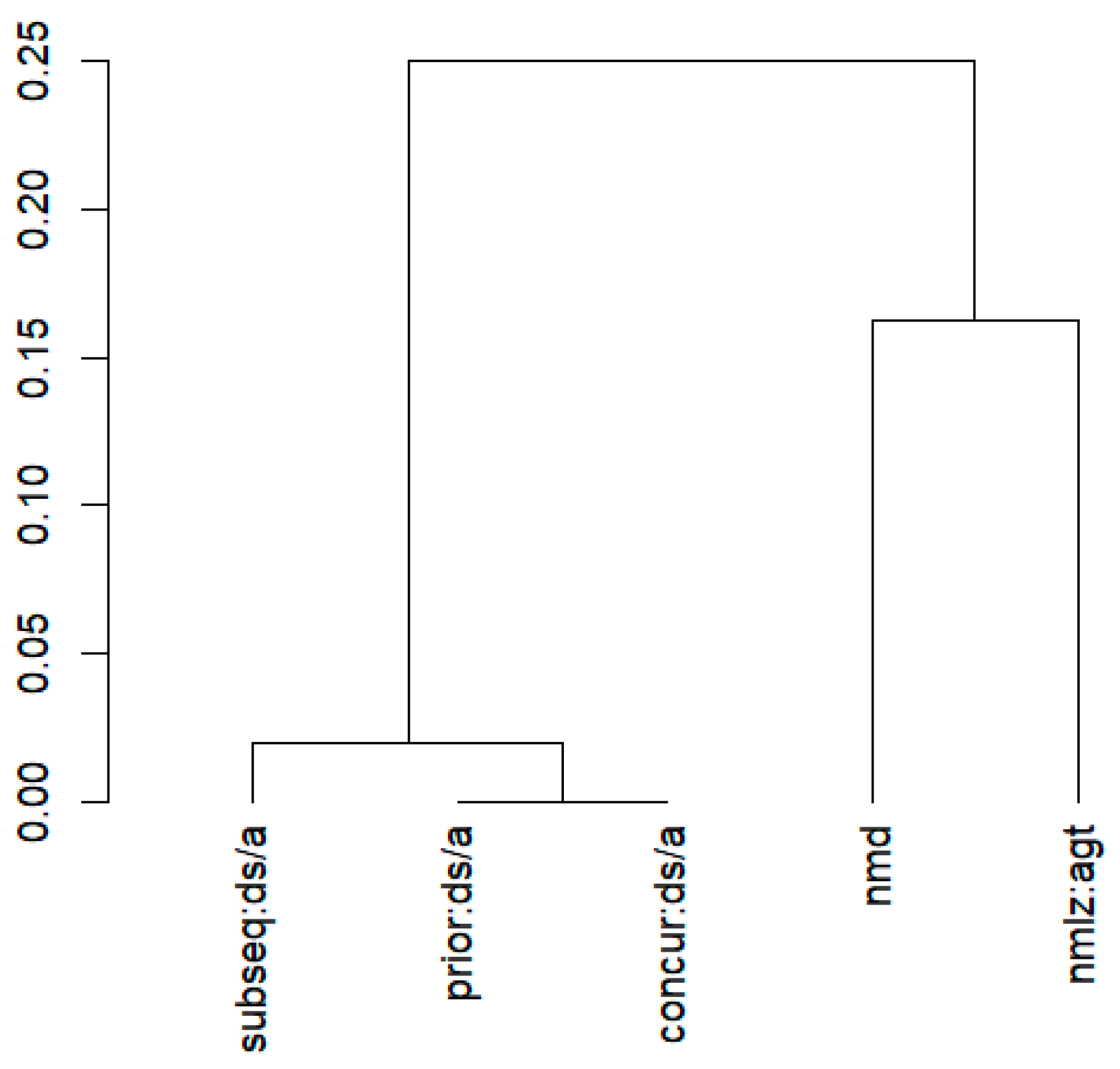

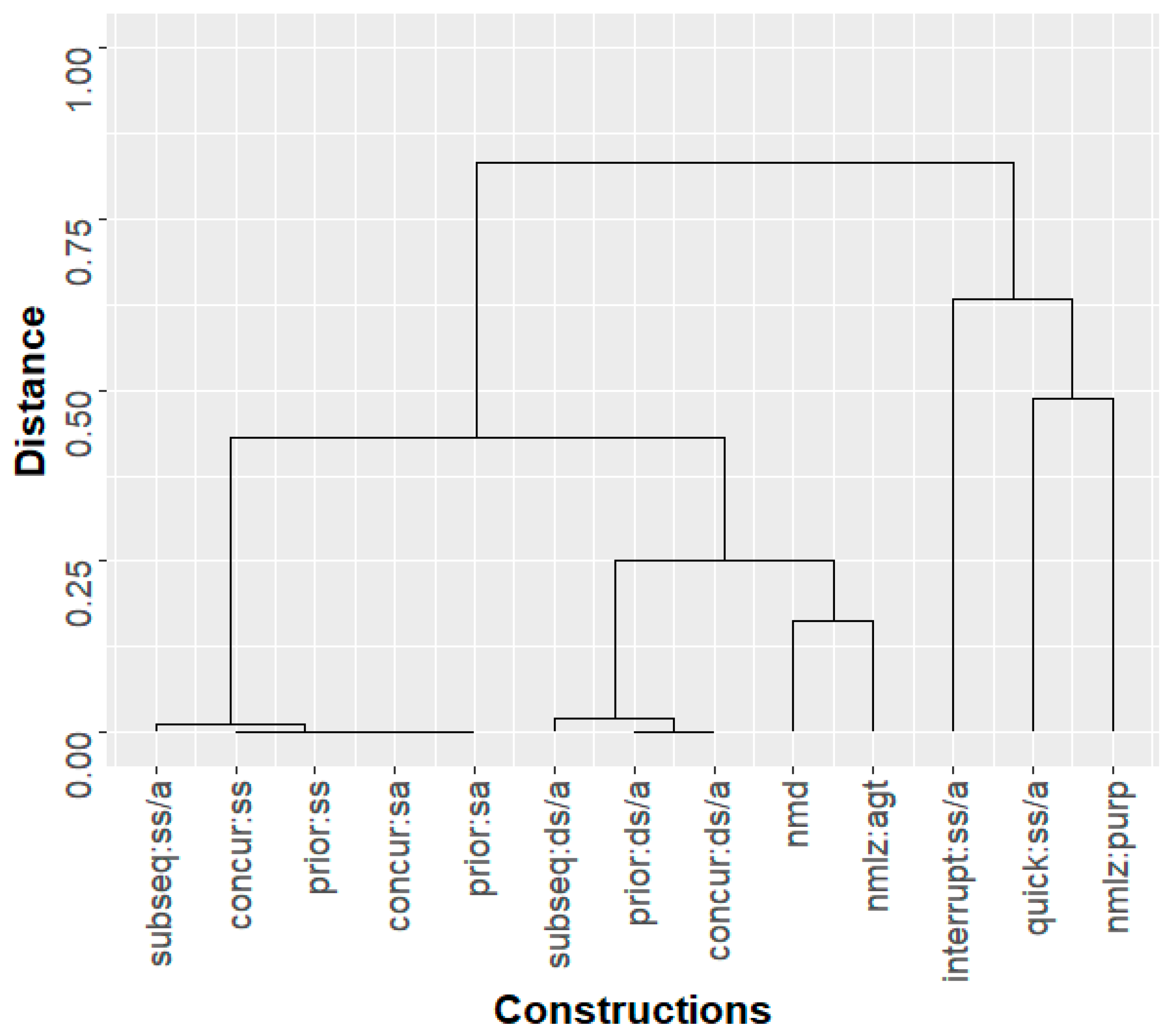

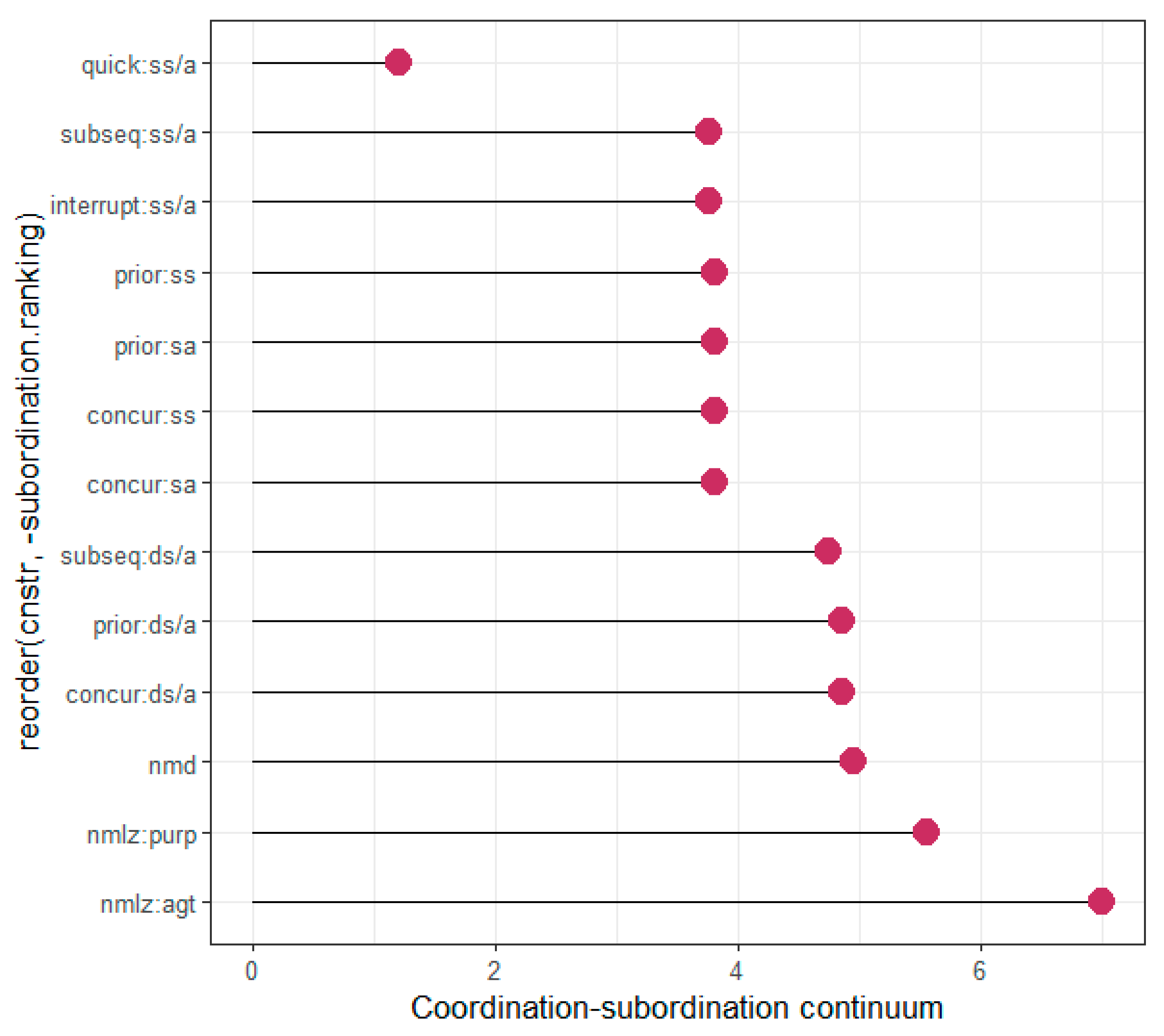

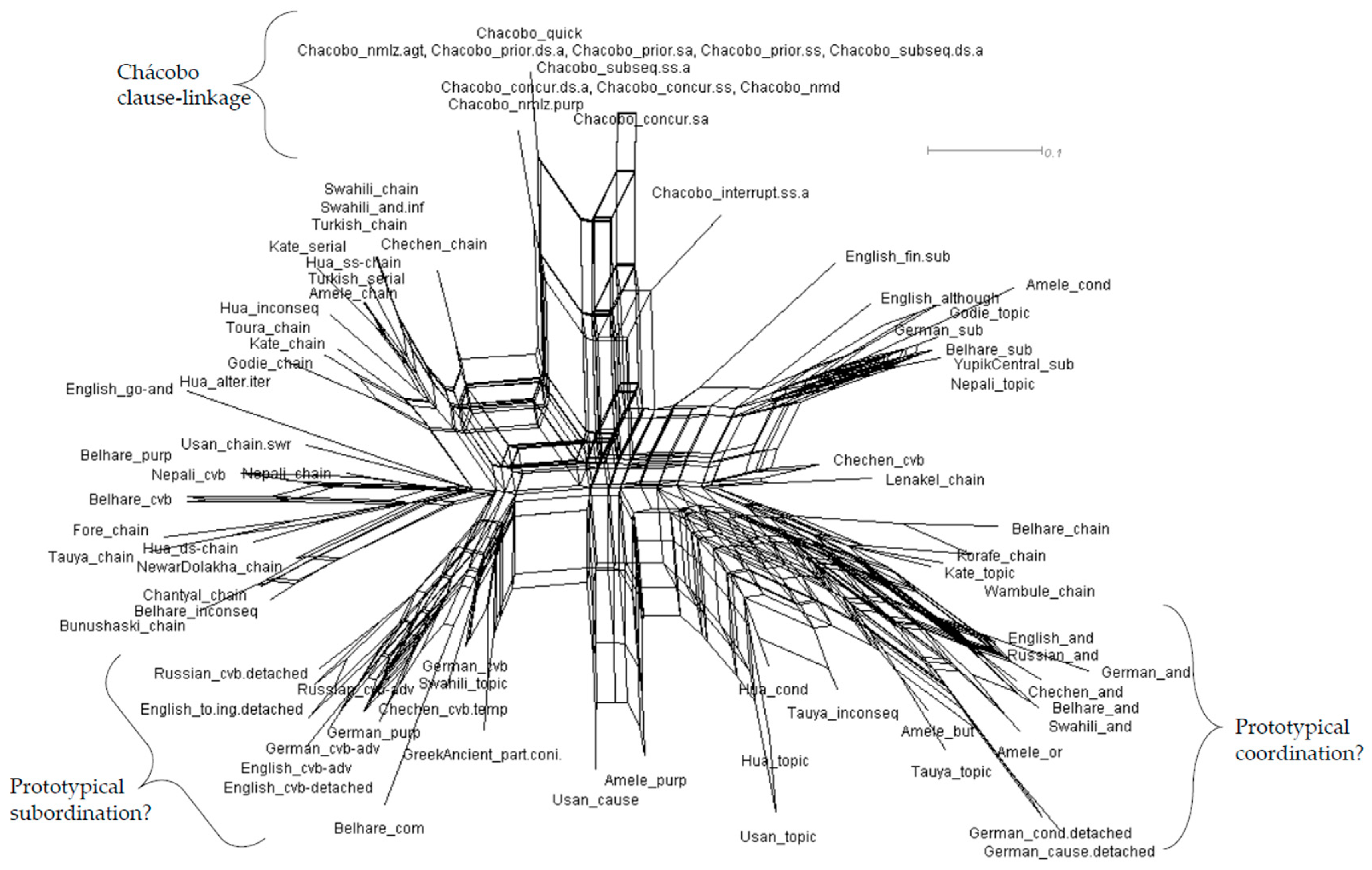

Dependent clauses linked through asyndetic combination can also be skipped over with respect to participant agreement. For instance, the transitive clause