Abstract

This study shows that the incorporation of the first-person plural pronoun a gente has not only reached the southernmost tip of the Brazilian territory, but has crossed the border and entered Uruguayan Portuguese, or varieties of Portuguese spoken in northern Uruguay by Portuguese–Spanish bilinguals. This finding is based on the quantification of the a gente/nós variable in sociolinguistic interviews carried out in two border communities: Aceguá, Brazil, and Aceguá, Uruguay. The analysis of interviews recorded on each side of the border yielded a total of 1000 tokens that were submitted to a multivariate analysis. Following the premises of comparative sociolinguistics, we compared the distribution of the variable on both sides of the border and found that although Uruguayans used a gente less often than Brazilians, this innovation, preferred by young speakers, is incorporated in both dialects, following similar linguistic paths. These results show that Uruguayan Portuguese has incorporated the pronominal a gente in its grammar in a clear sign of convergence towards Brazilian Portuguese and divergence from Spanish, despite the coexistence with Spanish that categorically uses nosotros as the first-person plural pronoun and reserves the cognate la gente for its purely lexical meaning ‘the people’.

1. Introduction

In Brazilian Portuguese, the use of the first-person plural pronoun a gente, which resulted from the grammaticalization of the noun phrase ‘the people’, is well attested and is increasingly displacing the pronoun nós (‘we’) (Omena 1996a, 1996b; Lopes 2003; Zilles 2005; Vianna and Lopes 2015; among others). Example (1) illustrates a case where the speaker clearly uses a gente rather than nós to refer to himself and his wife:

| (1) | O final de semana mesmo que a gente pode se juntar geralmente. Aproveito com a minha família mesmo com meus filho com minha mulher, a gente leva eles para passear. |

| ‘It is on the weekends that we can gather usually. I enjoy it with my family really with my kids, with my wife, we take them to outings.’ (Middle-aged man, São Paulo, Brazil)1 |

As we show in this study, this ongoing linguistic change in Portuguese has not only reached the southernmost tip of Brazilian territory, but has entered Uruguayan Portuguese, a variety of Portuguese spoken in northern Uruguay by Portuguese–Spanish bilinguals. We base our findings on quantification of the a gente/nós variable in subject position in sociolinguistic interviews conducted in two border communities: Aceguá, Brazil, and Aceguá, Uruguay, by the first author (Pacheco 2014). A comparison of the distribution of this variable in both dialects points to similar trends in both communities, indicating that Spanish–Portuguese bilinguals in Uruguay have assimilated Brazilian linguistic innovations despite long-term contact with Spanish.

Portuguese in Uruguay

Since colonial times, Portuguese has been spoken in Uruguay alongside Spanish, the national language. The presence of Portuguese in Uruguayan territory resulted from a long period of disputes during colonial times between the Portuguese and Spanish crowns over a vast, open territory along the northern border of Uruguay that was sparsely populated by Portuguese-speaking settlers. Uruguayan independence in 1828 did not have immediate repercussions in the region, and not until the second half of the nineteenth century did the central government take measures to Hispanicize the north and rid the region of Portuguese and Brazilian influence through the foundation of border towns and the establishment of Spanish-only public schools. As Elizaincín (1992, p. 158) describes, the area around Aceguá was especially deserted, remaining unpopulated or barely populated until the nineteenth century. Not until 1852 were markers installed in the area to demarcate the national border (Pedemonte 1985). Then, in 1862, the Uruguayan government named the land Juncal Pacheco. By that time, Portuguese had been established as the local language on both sides of the entire Uruguayan–Brazilian border.

Due to prolonged contact with Spanish, Uruguayan Portuguese is characterized by a heavy presence of Spanish loanwords and Spanish–Portuguese code-switching. In addition, the occurrence of vernacular Portuguese morphosyntactic and phonological variants and archaic words from rural Portuguese indicates that Uruguayan Portuguese has undergone fewer diachronic changes than Brazilian Portuguese (Elizaincín et al. 1987; Carvalho 2016). In fact, Elizaincín et al. (1987, p. 85) documented only the presence of lexical a gente in Uruguayan Portuguese, plus consistent use of nós as the first-person plural pronoun. As we demonstrate, since Elizaincín and colleagues’ research, Uruguayan Portuguese has incorporated the pronominal a gente in its grammar. The presence of this innovative variant in Uruguayan Portuguese represents convergence toward Brazilian Portuguese and divergence from Spanish (given that Spanish categorically uses nosotros as the first-person plural pronoun and preserves the purely lexical meaning of its cognate la gente). Example (2) illustrates the coexistence of lexical la gente and the nosotros conjugation (acentuamos) in Uruguayan border Spanish:

| (2) | Ahora trato, lógico, de corregirme porque como todos se ríen principalmente la gente del sur porque dicen los riverenses acentuamos las “eses” y las “uves”. |

| ‘Now I try of course, to correct myself, because since everyone laughs, especially people from the South, because they say (Ø-we) Riverans stress the ‘s’ and the ‘v’.’ (Middle-aged man, Rivera, Uruguay)2 |

This study advances a long history of studies on Uruguayan Portuguese that began with Rona’s seminal work in 1965 (Rona 1965). Later, Hensey conducted a series of sociolinguistic analyses of the phonological variables of Uruguayan Portuguese (Hensey 1972, 1982; among others), and Elizaincín and associates published multiple studies on morphosyntactic and lexical characteristics from the perspective of dialectology (e.g., Elizaincín et al. 1987; Elizaincín 1992). Carvalho’s (1998) doctoral dissertation led to follow-up variationist studies on phonological (Carvalho 2003, 2004; Garrido Meirelles 2009; Castañeda 2011, 2016; Córdoba 2013), morphosyntactic (Carvalho and Child 2011; Pacheco 2013, 2014; Carvalho and Bessett 2015; Carvalho 2016, 2021; Pacheco 2017a, 2017b, 2017c, 2018, 2020), and discourse variables (Carvalho and Kern 2019). This research produced quantitative evidence that, despite prolonged bilingualism along the Uruguay–Brazil border, Spanish and Portuguese have retained distinct variable grammars, albeit with extensive presence of lexical borrowings and conversational code-switching. However, most of what is known about Uruguayan Portuguese has been based on data collected on the Uruguayan side, mainly in the border town of Rivera.

To address this gap, the present study analyzes the use of pronominal a gente among Spanish–Portuguese bilinguals in Aceguá, Uruguay, and among Portuguese monolinguals in Aceguá, Brazil, so as to enable direct comparisons of cross-national varieties of Portuguese that are in daily contact. The comparison of a bilingual and a monolingual variety will allow us to identify convergent and divergent behavior, an essential element in the analysis of how language contact may drive language change. In comparative sociolinguistic studies (Tagliamonte 2013), it is vital that data collection and analysis of both dialects are handled in the same manner and that the varieties under examination serve as appropriate reference languages (Poplack and Levey 2010). First, this method enables us to identify to what extent a gente has spread to the Brazilian southern border, rather than comparing Uruguayan Portuguese with varieties of Brazilian Portuguese spoken far from the border, in regions where this linguistic innovation is widespread and well documented. Secondly, it allows us to investigate whether this innovation has crossed the border and influenced Uruguayan Portuguese, which would represent a linguistic change in light of Elizaincín and colleagues’ (Elizaincín et al. 1987) finding that it was not present in the 1980s. Importantly, if a gente has been incorporated into Uruguayan Portuguese, this would counter the thesis that the categorical use of lexical la gente in Spanish without a pronominalized counterpart would hinder this innovation in Portuguese. Finally, it is important to subject both datasets to the same variationist analysis, so that the factors that condition the realization of the variable can be compared cross-dialectally. The objective of such an analysis is to compare variable patterns in each dialect and determine whether Uruguayan Portuguese variable grammar matches the linguistic and social patterns that govern the use of a gente in the variety of Brazilian Portuguese spoken across the border. Ultimately, this analysis sheds light on the linguistic and social forces that advance or restrain the spread of a language change across a national border. In addition, by examining a context where cognate languages are in prolonged contact, this analysis tests commonly held assumptions that similar linguistic systems in contact tend to converge, resulting in bilingual dialects that differ significantly from their monolingual counterparts.

The consistent analysis of different datasets to the same analysis and their subsequent comparison is especially important in this case because the variable under study is subject to a wide range of variation in Brazilian Portuguese. Since the 1980s, multiple variationist studies have analyzed the distribution of first-person singular pronouns and found that the rate of a gente as opposed to nós ranges from 78% (Borges 2004) to 39% (Muniz 2008), depending on the community and the method used for quantification. Comparisons of a gente use between national varieties are rare. To our knowledge, they are limited to Vianna (2011) and Rubio (2012), who compared Brazilian and European Portuguese, finding that the innovative form is noticeably and significantly more prevalent in Brazil than in Portugal. In addition, Rubio (2012) reported that, while this variable presents stable variation in Portugal, it shows clear signs of rapid change toward the grammaticalized form and away from nós in Brazil. Rubio attributes this difference to the fact that in Portugal, a gente is seen as nonstandard and is avoided by women and well-educated speakers. The opposite situation occurs in Brazil, where since this innovation began (as early as the eighteenth century, according to Lopes (2003)), it has spread widely (Omena 1986, 1996a, 1996b) and does not have any stigma attached to it (Zilles 2007, p. 37). Unlike in Portugal, Uruguay Portuguese is spoken in communities that are in daily contact with monolingual speakers of Brazilian Portuguese, providing a favorable context for linguistic convergence, as we explain later.

In this paper, we first explain the speech community where sociolinguistic interviews were collected, the participants’ demographic information, and the methods used for data extraction and analysis. We then present our results, including the overall frequency of the variable in terms of communities and individuals and the multivariate analyses for each community. The analysis allows us to compare the variable BP and UP grammars in terms of the factor groups that are selected by each one and the ranking of the factors within these groups, and shows clear continuities across the dialects. Finally, we combine both datasets to test whether community would be chosen as a statistically significant factor due to any significant cross-dialectal distributional differences. We finally conclude that, while a gente has crossed the border and reached the UP grammar largely following the grammatical paths attested in BP, nós is still preferred by bilinguals, indicating that this linguistic change is more advanced in BP.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Aceguá Community

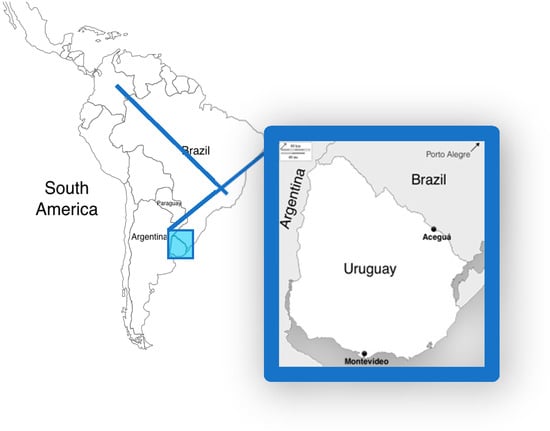

Aceguá is a border town of approximately 5000 residents located in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Its twin town of Aceguá, in the Department of Cerro Largo, Uruguay, hosts a smaller population of approximately 1500 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of the twin towns of Aceguá (from Pacheco et al. 2018).

No physical boundaries separate the two communities (Figure 2), and the national border is undetectable except for the linguistic landscape of public signs in Spanish in Uruguay and in Portuguese in Brazil. The movement of people and vehicles is uncontrolled, and residents cross from one side to the other often for work, visits, and shopping.

Figure 2.

Open border between Aceguá, Brazil, and Aceguá, Uruguay (photo by Pacheco 2014, p. 41).

2.2. Data Collection

The first author of this paper first visited Aceguá, Brazil, in 2009 and conducted sociolinguistic interviews with local residents. In 2011, she returned to the area and carried out similar sociolinguistic interviews with residents of Aceguá, Uruguay. The participants were identified through the snowball technique, and all promptly agreed to be interviewed. The recorded informal conversations lasted approximately one hour and took place at the participants’ homes or in public spaces such as plazas and restaurants. The present analysis is based on tokens extracted from 19 Portuguese speakers from Aceguá, Brazil, and 19 Portuguese speakers from Aceguá, Uruguay, divided into three age groups and two binary genders (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants.

2.3. Data Analysis

Once the interviews were transcribed, the first step was to distinguish the pronominal a gente from its lexical equivalent (‘the people’, occurring with a non-specific referent). The first token in Example 3, extracted from the corpus, is used with its lexical meaning: “toda a gente se confunde” (‘all people get confused’) carries an indeterminate referent and coincides with the Spanish equivalent, la gente. We excluded this type of token from our analysis because it does not carry the first-person plural meaning and, therefore, is outside the envelope of variation. The next token, nós notamos (‘we notice’), carries the first-person plural morpheme -mos, so was included in the analysis and coded as the nós form. The following three tokens were included as well—“a gente criou” (‘we created’), “a gente fala” (‘we speak’), and “não fala” (‘[we] don’t speak’)—since all are undoubtedly pronouns with first-person plural referents. Example (3) illustrates what Tagliamonte (2006, p. 168) calls a super-token that clearly shows both variants coexisting in the same conversational turn of a Uruguayan Portuguese speaker.

| (3) | Isso aqui, a cultura é mais ou menos a mesma, de toda a gente se confunde. Pra nós, não notamos… vocês que vem de longe podem notar a diferença, mas pra nós, a gente criou um dialeto pra falar, a gente fala portunhol, não fala nem espanhol nem português. |

| ‘This here, the culture is more or less the same, people get confused. For us, we don’t notice… you who come from far may notice some difference, but for us, we made up a dialect to speak it, we speak Portunhol, [we] don’t speak either Spanish or Portuguese.’ (50-year-old Uruguayan man3) |

Once all the verbs with first-person referents had been identified, both in their singular (referring to either expressed and unexpressed nós or a gente, depending on the previously expressed pronoun) and plural form (referring to nós), they were subjected to a multivariable analysis. The decision to include singular forms and further investigate whether the referent was nós or a gente (and code accordingly) was based on the fact that verbal agreement with nós subjects is variable in Brazilian Portuguese (Omena 1996a, 1996b; Naro et al. 1999; Vianna 2011; Vianna and Lopes 2015; Lopes 2003; Zilles 2005; Muniz 2008; Rubio 2012; Mattos 2013, 2017; Foeger 2014; Benfica 2016; Foeger et al. 2017; Naro et al. 2017; Scherre et al. 2018a, 2018b; among others). While a gente subjects may also take plural verbal morphemes in some areas of Brazil, this occurred only once in both varieties of Aceguá Portuguese (Pacheco 2014), coinciding with Zilles’s results for Porto Alegre, the largest city in the area (Zilles 2005, p. 36). Given the rarity of verbal -mos occurring with a gente referents, only singular verbal forms with a gente referents were included in the present analysis. Once all tokens had been identified, the first phase of analysis compared the frequency of occurrance of nós and a gente across the Brazilian and Uruguayan dialects to assess whether this linguistic innovation had reached both communities. Once the presence of a gente had been attested on both the Brazilian and Uruguayan sides of the border, our next step was to subject the two datasets to the same multivariate analysis in order to compare the variable patterns of each dialect and determine the permeability of the grammars.

Four linguistic factor groups and two social factors were included in this study. First, it was important to account for the type of subject; that is, to separately code verbal forms that were accompanied by an expressed subject (either nós or a gente) from those that were not. Example (4) illustrates the traditional first-person plural conjugation (temos, ‘[we] had’) preceded by an explicit pronoun nós, followed by another plural token (temo) without an expressed subject.

| (4) | Nós temos um clima semelhante ao do Rio Grande, pouquinha coisa mais frio. ∅ temo quatro estações bem definidas. |

| ‘We have similar weather compared to Rio Grande, just a little bit colder. [We] have four well-defined seasons.’ (50-year-old Uruguayan man) |

Example 5, uttered by the same speaker, illustrates the innovative first-person plural form (fala, ‘[we] speak’), first with an explicit pronominalized a gente as the subject, followed by repetition of the same verb (fala, ‘[we] speak’) without the subject.

| (5) | A gente fala portunhol, não fala nem o espanhol nem o português |

| ‘We speak portunhol, [we] don’t speak either Spanish or Portuguese’. (50-year-old Uruguayan man) |

As explained earlier, while plural verbs with unexpressed pronouns do refer to implicit nós, a verb that lacks a plural morpheme and has no explicit pronoun could have either nós or a gente as its referent. Thus, in cases where a singular verb was produced without an expressed subject, it was necessary to look at the preceding clauses to locate an explicit nós or a gente in order to correctly code the token. Example (6) illustrates the need to consider the preceding clause (a gente apresenta, ‘we present’) in order to properly classify the following verb clause (libera a mercadoria, ‘approve’) as an a gente token with an unexpressed subject.

| (6) | Então vem o cliente, a gente apresenta a mercadoria, libera a mercadoria, e aí é a aprovação do fiscal. Se ele carimbou tu tá aprovado. |

| ‘So the customer comes, we present the product, approve the product, and then it is up to the inspector’s approval. If he stamps it, it is approved.’ (Adult Brazilian male) |

Example (6) leads us to the second linguistic factor considered in the present analysis: persistence of one or the other variant. It is well documented that several morphosyntactic variants, once realized, tend to be repeated, due to a tendency for similar forms to occur together within a stretch of discourse (Poplack 1980; Weiner and Labov 1983; Scherre and Naro 1991; Scherre 1998; Paiva and Scherre 2022) Thus, the first verb in Example (7) (íamos, ‘went’) was coded as first token; and the second (juntávamos, ‘we gathered’) and third (movimentávamo, ‘[we] moved’) tokens were both coded as preceded by a nós form.

| (7) | Era um lixão aquilo. Nós do Rotary íamos lá, juntávamo o lixo, movimentávamo. |

| ‘That was a big dump. We, from Rotary, used to go there, gathered the trash, moved around’. (Middle-aged Uruguayan woman) |

Example (8) illustrates a series of singular verbs with a clear a gente antecedent. The first verb (chegava, ‘[we] arrived’) was coded as the first token, while the subsequent verbs (pagava, ‘[we] paid’; vinha, ‘[we] came’; and trazia, ‘[we] brought’) were also coded as preceded by a gente.

| (8) | A gente chegava ali, pagava 50% sobre o valor da mercadoria e vinha embora ou ia para qualquer lugar do Brasil, e o resto trazia. |

| ‘We arrived there, paid 50% on the product’s value, and came back or went somewhere else in Brazil, and brought the rest.’ (Elderly Brazilian man) |

The third linguistic independent variable included in the analysis was the verb’s tense and phonic salience. These features, when combined, have been proven to predict the choice of a gente in Brazilian Portuguese. The underlying hypothesis for why salience is a potential predictor of a gente is that the less salient the difference between nós vs. a gente verbal forms is (amava/amávamos; ama/amamos), the higher the chance that a gente will be chosen. In contrast, the more salient the difference between the plural and singular variants is (amou/amamos; foi/fomos), the higher the chance that nós will be chosen. When Naro et al. (1999) studied this variable in Rio de Janeiro, they found that, indeed, phonic salience was the main conditioning factor behind this variable in speakers from older generations. For younger speakers, however, verbal tense played a more significant role. The authors noted a strong interaction between the two variables of phonic salience and verb tense, given that the plural vs. singular opposition is less salient in imperfect forms (amava/amávamos) than in preterit forms (amou/amamos). More recent studies combine both variables into a single group (e.g., Mattos 2013, 2017; Foeger 2014; Benfica 2016; Foeger et al. 2017; Naro et al. 2017; Scherre et al. 2018a, 2018b). We follow the precedent of these previous studies in combining phonic salience and verbal tense into one variable.

In Brazilian Portuguese, verbal tense impacts the nós/a gente variable in several ways (Foeger 2014). For example, a gente is more common with imperfect verb forms, in order to avoid placing stress on the antepenultimate syllable (amava/amávamos). In addition, the lack of distinction between the present (amamos) and past (amamos) forms of first-person plural verbs may lead to more uses of a gente (ama) to avoid ambiguity. Finally, especially among urban speakers, the use of a gente has the potential to decrease the realization of verbal forms that lack standard plural agreement with present and imperfect forms, where the referent is nós (e.g., a gente fala instead of nós fala; a gente falava instead of nós falava). Thus, we follow previous studies (Zilles 2005; Foeger 2014; Scherre et al. 2018b) and include six factors within the verbal tense and phonic salience group, illustrated in Examples (9)–(15) from the least to the most salient forms:

- Gerund or infinitive (least salient)

| (9) | E a gente vendo da nascente lá… |

| ‘And we looking at the sunrise there.’ (Young Uruguayan male) |

- Imperfect (least salient singular/plural opposition)

| (10) | Daqui de Aceguá a gente tava em três. |

| ‘From here, from Aceguá, we were three.’ (Adult Uruguayan male) |

- Present, potentially with the same form as the preterit (least salient tense opposition)

| (11) | Porque aqui é muito raro ter um jornal ou algo do Uruguai. Aí nós lemo tudo brasileiro. |

| ‘Because here it is rare that there is a paper or something from Uruguay. Thus we read all in Brazilian.’ (Young Uruguayan woman) |

- Present, with a different form than the preterit (moderately salient opposition)

| (12) | E agora nós já estamos há dez anos aqui, né? |

| ‘And now we have been here for ten years, right?’ (Elderly Uruguayan male) |

- Preterit, potentially with the same form as the present (more salient opposition):

| (13) | A gente comprou faz pouco tempo até uma geladeira brasileira, mas a gente comprou em Melo, no Uruguai… |

| ‘We bought a short while ago even a Brazilian fridge, but we bought [it] in Melo, in Uruguay.’ (Adult Uruguayan Woman) | |

| (14) | E aí nós conseguimos para a Colônia, campeonato sete, saímo campeão último ano. Claro, muito cansativo! Eu saí daqui até Porto Alegre de carro, né? Terça-feira saímo daqui. |

| ‘And then we managed to go to Colonia, the seventh championship, we won the championship in the last year. Of course, very exhausting! I left here to Porto Alegre by car, right? On Tuesday we left.’ (Adult Brazilian male) |

- Preterit, with a different form than the present (more salient opposition):

| (15) | Aí nós fomos pra churrascaria, era 40.00 por pessoa e um horror a churrascaria. |

| ‘Then, we went to the steak house, it was 40.00 per person and a horrible steak house.’ (Young Brazilian woman) |

Finally, we included in the statistical analysis whether the semantic reference to the grammatical person was specific or generic. Example (16), from Aceguá, Brazil, illustrates the use of a gente with a clearly specific reference: the speaker and his family.

| (16) | Interviewer: Vocês moram aqui do lado do Brasil? |

| ‘Do you (pl.) live here, on the Brazilian side?’ | |

| Interviewee: Do lado brasileiro a gente mora. | |

| ‘On the Brazilian side we live.’ (Young Brazilian man) |

In contrast, Example (17) shows that the same form may carry a generic reference, one that does not specify a particular referent, but alludes instead to a collective, generalizing the first-person plural to include everyone in the region.

| (17) | E a gente aqui não tem trânsito né. Hoje mesmo eu saí com um chimarrão, eu vou guiando e tomando chimarrão. |

| ‘And we here have no traffic, right. Today I went out with my tea and went driving and drinking my tea.’ (Elderly Uruguayan man) |

Because the original meaning of the lexical item a gente is a collective ‘the people’, Omena (2003) argues that a generic reference should favor pronominal a gente, while a specific reference would favor nós. Previous studies (Omena 2003; Neves 2008) have shown that, indeed, generic reference often triggers the use of a gente, while specific reference tends towards nós in Brazilian Portuguese. In the current analysis, we investigate whether a first-person plural form with a generic reference favors a gente, as it does in Brazilian Portuguese, and whether Uruguayan Portuguese follows the same tendency.

Due to the small sample size, age group and binary sex were the only extra-linguistic factors included in the analysis. Age is an especially important factor in a study that investigates the possibility of language change in progress, since a preference for an innovative form among younger generations is usually interpreted as evidence that the innovation is underway in the community. Thus, three age groups were included in the analysis: 15–25 years old, 31–49 years old, and more than 50 years old.

The linguistic interviews of 19 speakers on each side of the border yielded a total of 1002 tokens that were submitted to Rbrul (Johnson 2009), yielding the following results.

3. Results

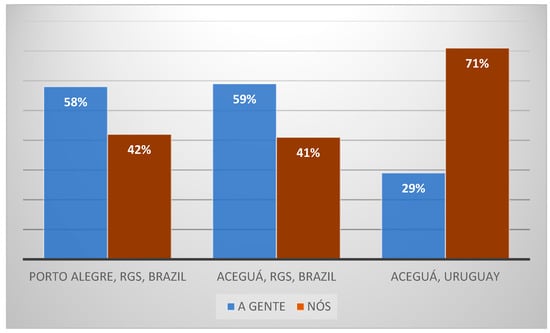

In Table 2, we compare the distribution of the nós/a gente variable on both sides of the border. Note that Uruguayans used a gente at a lower rate (29%) than Brazilians, who preferred the grammaticalized form 59% of the time.

Table 2.

Overall frequency of a gente vs. nós in subject position in Aceguá, Brazil, and Aceguá, Uruguay: data from all 38 participants (19 speakers from each country).

Zilles (2005) studied a gente vs. nós in Porto Alegre, the capital of the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul and the closest metropolis to Aceguá. She found that a gente was preferred at a rate of around 70% in all syntactic positions, and at around 58% in subject position (Zilles 2005, p. 40). Given the linguistic prestige of urban centers in Brazil, it is reasonable to assume that the speech of Porto Alegre serves as a linguistic model for the border communities. Thus, Figure 3 compares the rate of a gente vs. nós in subject position across the three communities: Porto Alegre; Aceguá, Brazil; and Aceguá, Uruguay.

Figure 3.

Overall frequencies of a gente and nós in subject position in Porto Alegre, Brazil (N = 1645), compared with Aceguá, Brazil (N = 541) and Aceguá, Uruguay (N = 461).

As Figure 3 shows, the Portuguese spoken in Porto Alegre and Aceguá, Brazil, shows similar rates of the innovative a gente pronoun, which has replaced more than half of the nós occurrences. Speakers in Aceguá, Uruguay, on the other hand, still prefer nós. The slower adoption of a gente, an urban linguistic innovation of Brazilian Portuguese, supports Carvalho’s (2016) claim that Uruguayan Portuguese tends to be more conservative and to lag behind language changes occurring in urban Brazilian Portuguese. The oscillation between nós and a gente in Uruguayan Portuguese is yet another reflection of the urban–rural continuum in which small towns in the area are situated (Carvalho 2003, 2004, 2016).

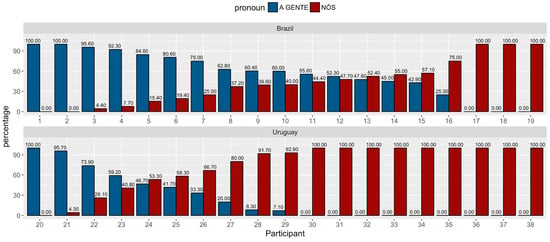

To account for individual variation, each speaker was coded in the data, allowing for identification of important differences (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Overall frequency of a gente vs. nós by individual speaker in Aceguá, Brazil (top), and Aceguá, Uruguay (bottom).

As Figure 4 shows, it is possible to find speakers who used one or the other variant categorically during their sociolinguistic interviews. In Aceguá, Brazil, two speakers used only a gente, while three used solely nós. In Aceguá, Uruguay, one speaker used only a gente, while nine speakers used only nós. In order to explore the linguistic and extralinguistic factors underlying variation, it was necessary to exclude these categorical users from the sample. Therefore, the data on Table 3 excludes three categorial nós users from Brazil and nine from Uruguay. The overall frequencies were recalculated, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Overall frequency of a gente vs. nós in subject position in Aceguá, Brazil, and Aceguá, Uruguay: data from 26 participants, (16 from Brazil, 10 from Uruguay).

As Pacheco (2014, p. 248) reported, when only speakers who used both variants are considered, the difference in overall rates between Brazilian and Uruguayan Portuguese are dramatically reduced. Both groups show higher rates of a gente: Brazilians’ usage increases slightly, from 59% to 63%, while Uruguayans’ usage of a gente increases more steeply, from 29% to 51% of the time. We have already established that the frequency of a gente is much higher in Brazilian than in Uruguayan Portuguese (Table 2), and that more Uruguayan than Brazilian speakers show categorical use of nós (Figure 4). This pattern allows us to conclude that a gente is more advanced in the Brazilian dialect.

A comparison of the factors that trigger the use of a gente in Brazilian Portuguese allows us, first, to explore the linguistic contexts in which the innovative variant has been incorporated and by what social groups. After we establish this baseline, we investigate the linguistic and social factors that condition the use of a gente in Uruguayan Portuguese to explore the extent to which that usage mirrors the same linguistic and social factors as for Brazilian Portuguese. To that end, our next step was to submit both datasets containing variation to a multivariate analysis in Rbrul (Johnson 2009). Following the premises of comparative sociolinguistics, we submitted both corpora to the same analysis, which included the type of subject, discourse persistence, tense and phonic salience of the verb, and the specificity of the pronoun, in addition to each speaker’s age group and sex (Table 4).

Table 4.

Rbrul results of pronominal a gente vs. nós in subject position in Portuguese from Aceguá, Brazil, and Aceguá, Uruguay (categorical users of nós excluded; random effects: individual).

Table 4 shows that five predictors statistically influenced the use of pronominal a gente in Brazilian Portuguese (discourse persistence, age, verbal tense and phonic salience, type of subject, and type of reference). However, only three were significant for Uruguayan Portuguese (verbal tense and phonic salience, discourse persistence, and type of subject). This finding suggests that a gente is more advanced in Aceguá, Brazil, than in Aceguá, Uruguay, where the incorporation of a gente is gradually catching up with the tendencies detected among Portuguese monolinguals.

For both communities, a strong predictor of the use of a gente is discourse persistence, also known as priming (see Paiva and Scherre (2022) for a review of the priming effect on variation). As expected, once one a gente is produced, the likelihood that this variant will recur is very high, reaching 0.79 for Brazilian border Portuguese and 0.89 for Uruguayan border Portuguese. On the other hand, a gente is strongly disfavored when preceded by nós in Brazilian border Portuguese (0.30), and even more so in Uruguayan border Portuguese (0.13). The probability weights show that a gente is disfavored as a first token in Brazilian border Portuguese (0.37) and slightly disfavored in Uruguayan border Portuguese (0.44). These results provide strong evidence that, once the innovative a gente is used, it by itself triggers recurring uses, in line with previous research (cf. Omena 1996a; Zilles 2005; Mendonça 2010; Rubio 2012; Mattos 2013; Foeger 2014; Pacheco 2014; Vianna and Lopes 2015; Souza 2020; among others). Notably, speakers in both communities respond to this factor, similarly showing continuity across variable grammars.

The next factor that conditions the use of pronominal a gente in Aceguá, Brazil, is the speaker’s age. As Table 4 illustrates, young participants in Brazil clearly prefer the innovative a gente (0.75), while elderly speakers tend to maintain nós (0.31). This is a typical pattern where age stratification signals an ongoing change led by young speakers. In Uruguay, however, age was not found to be significant, although the distribution of the use of a gente follows the same tendency detected on the other side of border: young Uruguayans, similarly to young Brazilians, are the ones leading the linguistic innovation in the community. The lack of significance could be the result of the small size of the sample and the fact that this statistical analysis includes speakers as a random effect. As more participants are added to future studies and a gente becomes more widespread in the community, age may become statistically significant in Aceguá, Uruguay. The next factor Rbrul identified for Brazilian Portuguese was verbal tense and phonic salience, which is the most influential factor in Uruguayan Portuguese. While both dialects are clearly influenced by this variable, there are some differences in the constraint ranking across the varieties, and they are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Ranking the impact of tense and phonic salience factors on a gente use in Aceguá Portuguese.

The results in Table 5 show that both dialects respond strongly to the same top two factors within the verbal tense and phonic salience group: present, potentially with the same form as the preterit (less salient opposition), and gerund or infinitive (forms with no person marking), both in italics. This result indicates that a gente is entering both dialects through similar linguistic routes, both of which are attested in previous studies of Brazilian Portuguese. Two other linguistic contexts also show a similar impact on both dialects: present with a different form than the preterit (‘vamos/fomos’) and preterit potentially with the same form as present (‘falamos/falamos’). The present with a different form than the preterit slightly disfavors a gente in Brazilian (0.44) and Uruguayan (0.43) varieties of Portuguese, while the preterit, potentially with the same form as the present, strongly disfavors a gente in both dialects (0.30 and 0.31, respectively).

Yet, the comparison of factor constraints in Table 5 points to two cross-dialectal discrepancies: the role of the imperfect (‘falava/falávamos’) and of the preterit that has a different form from the present (‘fomos/vamos’). As previously explained, in a few varieties of Brazilian Portuguese, contexts with imperfect verb forms favor a gente as a strategy to avoid words with the stress on the antepenultimate syllable, usually reduced in vernacular speech (Mattos 2013; Benfica 2016; Foeger et al. 2017; Scherre et al. 2018a; among others). This is the case in Aceguá, Brazil, albeit not to a great extent (0.56), while in Uruguayan Portuguese, the opposite tendency is found, where the imperfect strongly disfavors a gente (0.31) and favors nós. A closer look at the imperfect tokens in both dialects reveals the data shown in Table 6a, which indicates that while proparoxytones are avoided in Aceguá, Brazil (fewer than 10% of the imperfect tokens take plural morphemes), this tendency is not replicated in Aceguá, Uruguay, where 50% of the imperfect tokens take plural morphemes. While this apparent divergence between Brazilian and Uruguayan Portuguese merits future research, it might explain why imperfect tense has minimal impact on Uruguayan Portuguese speakers’ choice of a gente.

Table 6.

(a). Verbal morphemes used in imperfect verbal forms in Aceguá, Brazil, and Aceguá, Uruguay (without 12 categorial users of nós). (b). Verbal morphemes used in preterit, with different form than present in Aceguá, Brazil, and Aceguá, Uruguay (without 12 categorial users of nós).

The other factor where the constraining order differs is preterit with a different form than the present (‘fomos/vamos’), which disfavors a gente in Brazilian Portuguese (0.36) but favors it in Uruguayan Portuguese (0.65). Brazilian Portuguese follows the tendency found in other varieties to use nós with plural agreement in forms where this difference is highly salient (e.g., nós fomos, ‘we went’). Uruguayan Portuguese, on the hand, tends to use a gente with singular agreement, also avoiding verbal non-agreement (e.g., a gente foi, ‘we went’). Therefore, both varieties in the samples tend to show standard verbal agreement with both variants (nós fomos and a gente foi). A further analysis that investigates the details of preterit forms is in order so that the reason why border Uruguayan Portuguese does not follow the general tendency seen in Brazilian Portuguese and other varieties of Brazilian Portuguese is clarified. Nevertheless, the results in Table 6b show that both dialects behave similarly in their preference for standard verbal agreement:

In summary, aside from the discrepancies in the phonic salience and verbal tense group, the cross-dialectal comparison of constraint ranking shows that the grammars are strikingly consistent, especially given that the incorporation of a gente into Uruguayan Portuguese is incipient and infrequent, totaling only 29% of the total tokens when categorical users of nós are included.

The next factor identified for both communities by Rbrul is the type of subject. In both varieties, an expressed pronominalized a gente favors more a gente at a probability rate of 0.65 for Brazilian Portuguese and 0.76 for Uruguayan Portuguese, while an expressed pronoun favors nós. The fact that the direction of the constraint ranking is identical demonstrates that, like discourse persistence, subject expression influences both dialects in the same way. The results for both factor groups together reveal that, even though a gente is more frequently used in Brazilian Portuguese (Table 2 and Table 3), the variable grammars behind first-person singular pronouns follow similar patterns, which leads us to conclude that both communities share similar grammars. Notably, the linguistic contexts where this change is being favored match tendencies in other dialects of Brazilian Portuguese, since subject expression and discourse persistence top the factors found to condition a gente (e.g., Mattos 2013; Foeger 2014; Benfica 2016).

The final factor identified by Rbrul is type of reference. Speakers in Aceguá, Brazil, follow the tendency found in previous studies of Brazilian Portuguese: generic references slightly favor a gente (0.58), presumably a vestige of the semantics from its lexical source, ‘the people’, while a specific reference slightly favors the use of nós. Interestingly, the type of reference did not achieve significance in the sample from Uruguayan speakers, even though a similar distribution points to the same tendency. Finally, sex was not significant in either speech community. Although women commonly lead linguistic changes, this tendency was not seen in the present analysis.

In summary, a comparison of the independent variables influencing the realization of a gente instead of nós in the Portuguese varieties spoken across the Brazilian–Uruguayan border shows that both varieties present very similar variable grammars, illustrating clear continuities across the dialects. On both sides of the national border, a gente is triggered by discourse persistence, verbal tense and phonic salience, and type of subject, indicating that this linguistic innovation is spreading into the Portuguese pronominal system following similar linguistic routes. While the factor constraints for discourse persistence and type of subject show that the use of a gente trends in the same direction for both dialects (mirroring tendencies found in previous studies of Brazilian Portuguese), the order of constraints within the verbal tense and phonic salience group reveals two differential impacts pertaining to imperfect and preterit with a different form than the present. First, the imperfect favors a gente in Brazilian Portuguese but favors nós in Uruguayan Portuguese. We interpret this difference as being based on greater use of (and thus less resistance to) proparoxytones such as falávamos (‘we spoke’) in Uruguayan Portuguese. The second difference—namely, that preterit, with a different form than the present disfavors a gente in border Brazilian Portuguese, unlike in Uruguayan Portuguese and other varieties of Brazilian Portuguese—is harder to interpret and needs further investigation. In addition, two factors explain some of the variance in the Brazilian Aceguá dialect, but not in its Uruguayan counterpart: age and type of reference. We interpret these differences as signaling that the inclusion of a gente in Uruguayan Portuguese is more incipient, and we predict that, as the variant spreads more widely, both factors may become relevant to the distribution of a gente across the linguistic system and the community.

Lastly, in Table 7, we present a similar multivariate analysis, but one that includes both corpora and adds ‘community’ as an additional factor. Doing so enables us to determine whether community is a significant predictor of the expression of a gente. If this is the case, it would provide evidence of significant cross-dialectal differences and lack of convergence between the two grammars. If, on the other hand, community is insignificant, this would be yet another sign that the communities in fact behave as one dialectal area that shares the same variable grammar.

Table 7.

Pronominal a gente vs. nós in subject positions in Portuguese from Aceguá, Brazil, and Uruguay (without 12 categorical users of nós; random effects: individual).

Table 7 shows that, when the two communities are merged in the same statistical run, the same linguistic factor groups are selected, and the same ranking of factors is maintained. Discourse persistence, verbal tense and phonic salience, type of subject, and type of reference are significant, similar to the results in Table 4. Age is also significant, as expected if a linguistic change is in progress: the youngest group is most likely to use a gente. Importantly, community does not reach significance, countering the hypothesis that the odds of using a gente would be lower among bilinguals, despite the difference in overall frequencies. Thus, there is no statistical support for dialect-specific linguistic behavior in the use of pronominalized a gente in the larger border area of Aceguá.

4. Conclusions

In summary, following the premises of comparative sociolinguistics, we compared the distribution of the nós/a gente variable on both sides of the Brazil–Uruguay border. We found that Uruguayans still prefer nós and use a gente less often than Brazilians, who prefer the grammaticalized form more than half the time. Yet, it is clear that a gente has not only reached speakers in small towns in the south of Brazil, but has also crossed the border in Uruguay and is currently establishing itself alongside nós there. This represents a clear development since Elizaincín et al.’s (1987) study, where the authors attested only nós in Uruguayan Portuguese. A multivariate analysis shows that a gente is entering both communities in largely the same linguistic contexts, which are parallel to tendencies found for other dialects of Brazilian Portuguese, since verbal tense and phonic salience, discourse persistence, type of subject, and type of reference are linguistic constraints commonly found to condition this variable in other areas of Brazil (e.g., Omena 1996a; Lopes 2003; Zilles 2005; Scherre et al. 2018a). In terms of extra-linguistic factors, in both communities, the younger group of speakers shows a tendency to use a gente. However, this tendency has not reached statistical significance in Uruguayan Portuguese yet, which could indicate that this change is more incipient, or less advanced, among bilinguals.

In addition, these results support Carvalho’s argument (Carvalho 2003, 2004, 2014, 2016) for dialect leveling in the region due to the recent urbanization of Uruguayan Portuguese. On one hand, the incorporation of a gente is less frequent in the speech of Aceguá, Uruguay, compared to its counterpart in Aceguá, Brazil, in line with previous claims that Uruguayan Portuguese shows conservative traits when compared to Brazilian Portuguese. On the other hand, the variable distribution is replicated in both communities, which indicates the continued sociolectal extension into Uruguayan Portuguese of Brazilian Portuguese features.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P., A.C. and M.P.S.; data collection, C.P.; data analysis, C.P., A.C. and M.P.S. original draft preparation, C.P., A.C. and M.P.S.; visualization, C.P., A.C. and M.P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Maria Marta Pereira Scherre receives research funds from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the University of Brasilia, Brazil.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data for this study is protected and unavailable to the public.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of this study for offering us their time and sharing their stories with us.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Extracted from Projeto SP 2010 (SO 2012-045-M41DPO interview). |

| 2 | Extracted from Carvalho (1998) corpus of Rivera Spanish (003 interview). |

| 3 | All examples henceforth were extracted Pacheco (2014) corpus of Uruguayan Portuguese. |

References

- Benfica, Samine de Almeida. 2016. A Concordância verbal na fala de Vitória. Master’s dissertation, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, Paulo R. S. 2004. A Gramaticalização de “a gente” no português brasileiro. Ph.D. dissertation, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, Ana M. 1998. The Social Distribution of Uruguayan Portuguese in a Bilingual Border Town. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, Ana M. 2003. Rumo a uma definição do português uruguaio. Revista internacional de Linguística Iberoamericana 2: 125–49. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, Ana M. 2004. I Speak Like the Guys on TV: Palatalization and the Urbanization of Uruguayan Portuguese. Language Variation and Change 162: 127–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, Ana M. 2014. Sociolinguistic Continuities in Language Contact Situations: The Case of Portuguese in Contact with Spanish along the Uruguayan-Brazilian Border. In Portuguese/Spanish Interfaces. Edited by Patricia Amaral and Ana M. Carvalho. Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 263–94. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, Ana M. 2016. The Analysis of Languages in Contact: A Case Study through a Variationist Lens. Cadernos de Estudos Linguísticos 58: 401–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carvalho, Ana M. 2021. Differential object marking in monolingual and bilingual Spanish. In The Routledge Handbook of Variationist Approaches to Spanish. Edited by Manuel Díaz-Campos. New York: Routledge, pp. 393–410. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, Ana M., and Joseph Kern. 2019. On the Permeability of Tag Questions in the Speech of Spanish-Portuguese Bilinguals. Pragmatics 29: 463–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, Ana M., and Michael Child. 2011. Subject Pronoun Expression in a Variety of Spanish in Contact with Portuguese. In Selected Papers of the Fifth Workshop in Spanish Sociolinguistics. Edited by Jim Michnowicz. Summerville: Cascadilla Press. Available online: http://www.lingref.com/cpp/wss/5/paper2502.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2023).

- Carvalho, Ana M., and Ryan M. Bessett. 2015. Subject Pronoun Expression in Spanish in Contact with Portuguese. In Subject Pronoun Expression in Spanish: A Cross-Dialectal Perspective. Edited by Ana M. Carvalho, Rafael Orozco and Naomi R. Shin. Washington: Georgetown University Press, pp. 143–66. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda, Rosa M. 2011. Linguistic Variation in a Border Town: Palatalization of Dental Stops and Vowel Nasalization in Rivera. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda, Rosa M. 2016. The Sociolinguistic Evolution of a Sound Change. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics 15: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Córdoba, Alexander S. 2013. A Neutralização das vogais postônicas finais do português uruguaio falado na cidade de Tranqueras, Uruguai. Master’s dissertation, Universidade Católica de Pelotas, Pelotas, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Elizaincín, Adolfo. 1992. Dialectos en contacto: Español y portugués en España y América. Montevideo: Arca. [Google Scholar]

- Elizaincín, Adolfo, Luis E. Behares, and Graciela Barrios. 1987. Nós falemo brasilero. Dialectos portugueses en el Uruguay. Montevideo: Amesur. [Google Scholar]

- Foeger, Camila C. 2014. A primeira pessoa do plural no português falado em Santa Leopoldina. Master’s dissertation, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo, Vitória, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Foeger, Camila C., Lilian C. Yacovenco, and Maria Marta Pereira Scherre. 2017. A primeira pessoa do plural em Santa Leopoldina/ES: Correlação entre alternância e concordância. Letrônica 10: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido Meirelles, Virginia. 2009. O português da fronteira Uruguai-Brasil. In Português em contato. Edited by Ana M. Carvalho. Madrid: Vervuert Iberoamericana, pp. 257–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hensey, Frederick G. 1972. The Sociolinguistics of the Brazilian Uruguayan Border. The Hague: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Hensey, Frederick G. 1982. Spanish, Portuguese and Fronteiriço: Languages in contact in Northern Uruguay. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 34: 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Daniel E. 2009. Getting off the GoldVarb Standard: Introducing Rbrul for Mixed Effects Variable Rule Analysis. Language and Linguistics Compass 3: 359–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, Célia R. dos Santos. 2003. A inserção de ‘a gente’ no quadro pronominal do Português. Frankfurt am Main and Madrid: Vervuert/Iberoamericana, vol. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Mattos, Shirley Eliany Rocha. 2013. Goiás na primeira pessoa do plural. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Mattos, Shirley Eliany Rocha. 2017. A primeira pessoa do plural na fala de goiás. Revista (Con) Textos Linguísticos (UFES) 11: 145–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça, Alexandre Kronemberger de. 2010. NÓS e A GENTE em Vitória: Análise sociolinguística da fala capixaba. Master’s dissertation, Universidade do Espírito Santo, Vitória, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Muniz, Cleuza A. G. 2008. Nós e A gente: Traços sociolinguísticos no assentamento. Master’s dissertation, Universidade Federal do Mato Grosso, Campo Grande, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Naro, Anthony J., Edai Görski, and Eulália Fernandes. 1999. Change without Change. Language Variation and Change 11: 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Naro, Anthony J., Maria Marta Pereira Scherre, Camila Foeger, and Samine de Almeida Benfica. 2017. Linguistic and Social Embedding of Variable Concord with 1st Plural Nós ‘We’ in Brazilian Portuguese. In Studies on Variation in Portuguese, 1st ed. Edited by Pilar Barbosa, Maria da Conceição de Paiva and Celeste Rodrigues. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 219–31. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, Maria Helena de Moura. 2008. Pronomes. In Gramática do português culto falado no Brasil. Edited by Ataliba Teixeira de Castilho, Rodolfo Ilari and Maria Helena de Moura Neves. Campinas: Editores UNICAMP. [Google Scholar]

- Omena, Nelize Pires de. 1986. A referência variável da primeira pessoa do discurso do plural. In Relatório final de pesquisa: Projeto Subsídios do Projeto Censo à Educação. Edited by Anthony J. Naro. Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ, pp. 286–319. [Google Scholar]

- Omena, Nelize Pires de. 1996a. A referência à primeira pessoa do discurso no plural. In Padrões sociolinguísticos: Análises de fenômenos variáveis do português falado na cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Edited by Giselle Machline de Oliveira e Silva and Maria Marta Pereira Scherre. Rio de Janeiro: Tempo Brasileiro, pp. 183–215. [Google Scholar]

- Omena, Nelize Pires de. 1996b. As influências sociais na variação entre nós e a gente na função de sujeito. In Padrões sociolinguísticos: Análises de fenômenos variáveis do português falado na cidade do Rio de Janeiro. Edited by Giselle Machline de Oliveira e Silva and Maria Marta Pereira Scherre. Rio de Janeiro: Tempo Brasileiro, pp. 309–23. [Google Scholar]

- Omena, Nelize Pires de. 2003. A referência à primeira pessoa do plural: Variação ou mudança? In Mudança linguística em tempo real. Edited by Maria da Conceição de Paiva and Maria Eugênia Lamoglia. Rio de Janeiro: Contra Capa Livraria, pp. 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, Cíntia da Silva. 2013. Primeiras reflexões sobre o português fronteiriço de Aceguá. In Variação linguística: Contato de Línguas e Educação. Edited by Caroline Rodrigues Cardoso, Maria Marta Pereira Scherre and Heloísa Maria Moreira Lima-Salles. Cíntia Pacheco. Contribuições do III encontro do grupo de estudos avançados de sociolinguística da Universidade de Brasília. Campinas: Pontes Editores, pp. 187–207. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, Cíntia da Silva. 2014. Alternância NÓS e A GENTE no português brasileiro e no português uruguaio da fronteira Brasil-Uruguai (Aceguá). Ph.D. dissertation, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, Cíntia da Silva. 2017a. Como definir o falar da fronteira Brasil-Uruguai? (Con)textos linguísticos 11: 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, Cíntia da Silva. 2017b. Contato linguístico na fronteira de Aceguá (Brasil-Uruguai). Papia 27: 109–33. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, Cíntia da Silva. 2017c. Identidade sociolinguística na fronteira de Aceguá (Brasil-Uruguai). Revista de Estudos da Linguagem 25: 276–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pacheco, Cíntia da Silva. 2018. A diacronia e a sincronia dos pronomes de primeira pessoa do plural NÓS e A GENTE no português brasileiro e no português uruguaio. Revista de Estudos da Linguagem 1: 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, Cíntia da Silva. 2020. Contextualização sócio-histórica da fronteira Brasil-Uruguai. Revista de Estudos e Pesquisas Sobre as Américas 14: 257–93. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, Cíntia da Silva, Ana M. Carvalho, and Maria Marta Pereira Scherre. 2018. When a new pronoun crosses the border: The spread of a gente on the Brazilian-Uruguayan frontier. In 47 New Ways of Analyzing Variation—NWAV. New York: New York University. [Google Scholar]

- Paiva, Maria da Conceição, and Maria Marta Pereira Scherre. 2022. Revisitando o efeito da repetição na variação linguística. In Contribuições para a linguística brasileira: Uma homenagem a Dinah Callou, 1st ed. Edited by Josane Moreira de Oliveira, Jacyra Andrade Mota and Regiane Coelho Pereira Reis. Campo Grande: Editora da UFMS, vol. 1, pp. 259–77. Available online: https://repositorio.ufms.br/handle/123456789/5811 (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Pedemonte, J. C. 1985. Assembléia Geral. Diario El País. [Google Scholar]

- Poplack, Shana. 1980. The Notion of the Plural in Puerto Rico Spanish: Competing Constraints on /s/ Deletion. In Locating Language in Time and Space. Edited by William Labov. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 55–67. [Google Scholar]

- Poplack, Shana, and Stephen Levey. 2010. Contact-Induced Grammatical Change: A Cautionary Tale. In Language and Space: An International Handbook of Linguistic Variation. Edited by Peter Auer and Jürgen Erich Schmidt. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 391–419. [Google Scholar]

- Rona, José P. 1965. El dialecto “fronterizo” del norte del Uruguay. Montevideo: Adolfo Linardi. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, Cassio F. 2012. Padrões de concordância verbal e de alternância pronominal no português brasileiro e europeu: Estudo sociolinguístico comparativo. Ph.D. dissertation, Instituto de Biociências, Letras e Ciências Exatas, Universidade Estadual Paulista, São José do Rio Preto, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Scherre, Maria Marta Pereira. 1998. Paralelismo linguístico. Revista de Estudos da Linguagem 7: 29–59. Available online: http://periodicos.letras.ufmg.br/index.php/relin/article/view/2293/2242 (accessed on 25 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Scherre, Maria Marta Pereira, and Anthony J. Naro. 1991. Marking in Discourse: “Birds of a Feather”. Language Variation and Change 3: 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherre, Maria Marta Pereira, Anthony J. Naro, and Lilian C. Yacovenco. 2018a. Nós e a gente em quatro amostras do português brasileiro: revisitando a escalada da saliência fônica. Diadorim 20: 428–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherre, Maria Marta Pereira, Lilian C. Yacovenco, and Anthony J. Naro. 2018b. Nós e a gente no português brasileiro: Concordâncias e discordâncias. Estudos de Lingüística Galega 1: 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, Maria Helena Menezes. 2020. A variação nós e a gente na posição de sujeito na comunidade quilombola Serra das Viúvas/Água Branca—AL. Master’s dissertation, Universidade Federal de Alagoas, Maceió, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, Sali A. 2006. Analysing Sociolinguistic Variation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tagliamonte, Sali A. 2013. Comparative sociolinguistics. In The Handbook of Language Variation and Change. Edited by J. K. Chambers and Natalie Schilling. New York: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 128–56. [Google Scholar]

- Vianna, Juliana Barbosa de Segadas. 2011. Semelhanças e diferenças na implementação de a gente em variedades do português. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Vianna, Juliana Barbosa de Segadas, and Célia R. dos Santos Lopes. 2015. Variação dos pronomes “nós” e “a gente”. In Mapeamento sociolinguístico do português brasileiro. Edited by Marco Martins and Jussara Abraçado. São Paulo: Contexto, pp. 109–31. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, E. Judith, and William Labov. 1983. Constraints on the Agentless Passive. Journal of Linguistics 19: 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilles, Ana M. S. 2005. The Development of a New Pronoun: The Linguistic and Social Embedding of A Gente in Brazilian Portuguese. Language Variation and Change 17: 19–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilles, Ana M. S. 2007. O que a fala e a escrita nos dizem sobre a avaliação social do uso de a gente? Letras de Hoje 42: 27–44. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).