Abstract

As one of the productive approaches to L2 pragmatic development, study abroad (SA) has drawn the attention of numerous researchers during the past few decades. Different factors, specifically those related to L2 learners, implicate the impact of SA on pragmatic development. The present systematic review aims to identify the roles of individual differences, including personal as well as social and cognitive variables, on the pragmatic development of L2 learners who were involved in SA programs. To this end, 39 studies from peer-reviewed journals and books published from 2000 to 2022 were scrutinized. The results revealed that a substantial amount of research has been conducted on the intersection of L2 pragmatic competence and SA. However, more studies are required to investigate the impact of learner variables on different aspects of L2 pragmatics in the SA context. The results also indicated the extent to which learner variables were analyzed in these studies and how each variable impacted the effectiveness of SA programs. In addition to the effects of learner variables, the methodological features of the studies, including the context of the studies, designs of the studies, data sources, and characteristics of the involved participants, were explored and reported. The findings contribute to the fields of L2 pragmatic acquisition and study abroad by highlighting the gaps in the literature and identifying key learner variables that can have drastic influences on learners’ outcomes.

1. Introduction

The proliferation of international exchange agreements and the internationalization movements have led many school authorities and educators to support study-abroad (SA) programs to enhance the quality of their education (Matsumura 2022; Sánchez-López 2018). Due to the abundance of linguistic exposure and cultural experience opportunities provided to L2 learners, studying abroad has been preferred by numerous researchers for developing individuals’ language competence, including pragmatic competence, in comparison to home contexts (Taguchi 2018a; Xiao 2015a). As the literature suggests, the degree of the effectiveness of such programs is bounded by several individual and contextual factors. For instance, numerous researchers have explored the effects of different forms of pre-departure or whilst-abroad pedagogical interventions on learners’ pragmatic gains (e.g., Halenko 2017; Matsumura 2022; Pérez-Vidal 2014). They believe that such instructions can boost individuals’ learning experiences or enhance their language socialization with the host communities (e.g., Alcón-Soler 2015; Ishihara and Takamiya 2019; Kinginger 2011). However, given all the complexity of the SA experience and the nature of pragmatic competence, different and confounding results have been reported regarding the impact of SA on learners’ pragmatic gains. It is argued that one of the main reasons for these incomparable results among learners is the interplay of individuals’ idiosyncratic affective and cognitive profiles with the SA setting. Thus, as SA is by no means a static experience in essence, the impacts of these variables on learners’ pragmatic outcomes have been investigated (Ren 2018; Sánchez-Hernández and Alcón-Soler 2019a). Along the same line of inquiry, the current study aims to shed light on the roles of several learners’ variables on their pragmatic development whilst studying abroad by systematically reviewing the previous studies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Study Abroad and L2 Pragmatic Acquisition

In general, SA in second language acquisition refers to an L2 learning setting where individuals study the language in the target community. It has been considered an effective approach to enhance learners’ pragmatic competence as it affords them opportunities to observe and practice the appropriate use of language in different settings, experience authentic L2 conversations, and be exposed to linguistic and pragmatic variation in different contexts (Pérez-Vidal and Shively 2019; Taguchi 2018a; Xiao 2015a). The superiority of SA over home educational contexts for enhancing L2 pragmatic features has been repeatedly reported in the literature (e.g., Taguchi 2011; Félix-Brasdefer and Hasler-Barker 2015).

So far, the impacts of different variations of the SA experience on several aspects of L2 pragmatics such as speech act, discourse markers, and politeness have been explored (see Xiao 2015a). A body of research has focused on the effects of the length of stay and evidenced the positive effects of short-term stays, where learners have limited time and opportunity to assimilate with the target culture and to develop their L2 pragmatics (e.g., Al Masaeed 2022; Czerwionka and Cuza 2017; DiBartolomeo et al. 2019; Hassall 2013), as opposed to longer educational sojourns lasting a year or more (e.g., Iwasaki 2010; Ren 2013).

Other studies have coupled short stays with directed instructional intervention to facilitate the programs’ efficiency (e.g., Alcón-Soler 2015; Hernández 2018; Hernández and Boero 2018; Matsumura 2022; Shively 2011). For instance, Hernández and Boero (2018) studied the impact of pre-departure explicit instruction followed by task completion during the learners’ stay on the development of L2 learners’ Spanish requests as a result of their sojourn in Argentina. The comparison of participants’ performance in the pre-test, post-test, and delayed post-test implied the effectiveness of the experience. Although many studies have referred to the effectiveness of pedagogical instruction, Alcón-Soler (2015) reported a somewhat different result. She found that although pedagogical intervention during SA can have immediate effects on pragmatic development, results might not last long and are bound by the length of stay. The findings further suggested that the knowledge gained through instruction can be alternatively obtained after plenty of exposure to input and communication opportunities during the SA experience (Alcón-Soler 2015).

Another approach to increasing learners’ L2 communication and the effectiveness of their SA, which can occasionally be accompanied by pedagogical instructions (e.g., Matsumura 2022), is to provide the opportunity to live with host families where learners can live with native L2 speakers and spend more time practicing L2 (e.g., Czerwionka and Cuza 2017; DuFon 1999; Shively 2011). Nonetheless, it has been reported that host families provide information and feedback on learners’ pragmatic choices in limited opportunities, for example, when they are specifically asked by students (Shively 2011). The findings on L2 pragmatic improvements in the SA context are quite mixed as many factors, including different aspects of pragmatic features, aspects of pragmatic performance, individual differences, opportunities for practice, and the extent of interaction, influence individuals’ progress, which require further investigations (Alcón-Soler 2015; Ishihara and Takamiya 2019).

2.2. Learner Variables in Pragmatic Acquisition

Theorizing and researching in second language education show that many variables can impact the rate and route of language acquisition (Dörnyei 2005; Ellis and Shintani 2013; Yang and Wang 2022). These variables fall within a wide gamut, including learner variables, input, teaching materials, test washback, the effectiveness of teachers, home and study-abroad learning contexts, and macro- and micro-policies of language education. Among these, learner variables are central to the process of acquisition of communicative competence or its components (C. Li 2022; Tajeddin et al. 2022; Vandergrift and Baker 2015; Yang and Wang 2022). The large body of research on L2 acquisition has documented the impact of numerous learner variables in this process, which can be categorized into personal (e.g., age, proficiency level, L1 background, and the length of stay), cognitive (e.g., learning style and learning strategies), and affective (e.g., emotion, willingness to communicate, and motivation) variables.

Aligned with this strand of research in second language acquisition, learner variables have been the focus of studies in L2 pragmatics (e.g., Malmir and Derakhshan 2020; Plonsky and Zhuang 2019; Takahashi 2019; Xiao 2015b). This extensive volume of research has been conducted to broaden our knowledge on preparing the optimum SA programs that consider their learners’ variables to enhance their pragmatic competence more efficiently (Sanz 2014). A number of studies have focused on learners’ length of stay and amount of contact or interaction with the target community (e.g., Alcón-Soler 2015; Bella 2011; Hernández 2010; Ren 2019; Taguchi 2008), while others have investigated the role of learners’ linguistic and affective differences such as their language proficiency, motivation level, and age in their pragmatic gain in study-abroad contexts (e.g., Alcón-Soler and Sánchez Hernández 2017; Liu et al. 2022; Sánchez-Hernández 2018; Sánchez-Hernández and Alcón-Soler 2019b). They have also investigated how these variables affect the acquisition of pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic competencies (e.g., Bardovi-Harlig and Su 2018; Devlin 2019; Malmir and Derakhshan 2020), the comprehension and production of speech acts (Cornillie et al. 2012; Jernigan 2012; Russell and Vásquez 2018; Yang and Wu 2022), pragmatic routines (e.g., Alcón-Soler and Sánchez Hernández 2017; Bardovi-Harlig and Su 2018; Yang 2016), and politeness markers or other pragmatic markers (e.g., Economidou-Kogetsidis 2016; Magliacane and Howard 2019; Ren 2022).

As one of the most researched variables, the language proficiency of learners and its relationship with their pragmatic level and development has always been something of an enigma for L2 researchers, as this question has been raised in many studies, although it has yielded mixed results. Xiao (2015b) targeted this issue by conducting a research synthesis of 28 cross-sectional studies focusing on the effects of L2 proficiency on adult L2 learners’ pragmatic competence. Findings revealed an overall positive proficiency effect, and, in most cases, higher proficiency led to higher pragmatic competence. Yet, increased linguistic proficiency does not guarantee a native-like pragmatic performance since the proficiency effect is bounded by various factors including the target pragmatic feature (e.g., types of speech acts). Motivation is another variable that, in most cases, has been assumed to be correlated with learners’ pragmatic competence (Tajeddin and Zand Moghadam 2012; Yang and Ren 2019). The majority of the previous studies revealed that intrinsic or communication-oriented motivation helps individuals to use more appropriate pragmatic forms, have a greater awareness of L2 pragmatics, and better identify pragmatic errors (Tagashira et al. 2011; Takahashi 2015; Tajeddin and Zand Moghadam 2012). However, so far, some variables such as learners’ age or gender and their role in their pragmatic development have received less attention (Schauer 2022; Tajeddin and Malmir 2014)

The findings from the studies reviewed above have contributed to our understanding of pragmatic acquisition and provided a lens to see how learner variables are implicated in this acquisition. However, despite the rich literature on SA as well as various reviews on pragmatic instruction and the roles of different variables on learners’ achievements (e.g., Barron 2019; Nightingale and Alcón-Soler 2023; Wyner and Cohen 2015; Xiao 2015b), no systematic review has yet specifically targeted the interplay of learners’ variables, including their cognitive, affective, personal, and psychological ones, with their pragmatic development during their SA programs. This gap corresponds with the current systematic review, which aims to give further evidence on the impact of individual differences on learners’ pragmatic competence during their sojourn in the target community by covering the research carried out in the field of SLA. Thus, based on the volume of research conducted through the past two decades (from 2000 to 2022), the following research questions were raised:

- What are the methodological characteristics of the studies investigating the effects of learner variables on L2 pragmatic development in SA contexts (including research designs and analyses)?

- What learner variables were investigated in the studies of L2 pragmatic development in SA contexts? What were their effects?

3. Method

3.1. The Studies and Selection Criteria

The studies were collected through a sequential process of (a) web search engine, (b) similar review studies’ search, (c) journal search, and (d) exclusion/inclusion based on the specified criteria to cover major studies on the role of learner variables in L2 learners’ pragmatic development during their SA from credible field-specific journals.

As suggested by several researchers (Gough et al. 2013; Lipsey and Wilson 2001) and followed in many reviews (Avgousti 2018; Tajeddin et al. 2022), we used different search engines and sources to better locate the relevant studies, since a single database might not be comprehensive (Avgousti 2018). Similar to many previous systematic reviews, Google Scholar was one of our primary databases for finding the studies (e.g., Yang et al. 2021; Marsden et al. 2018).

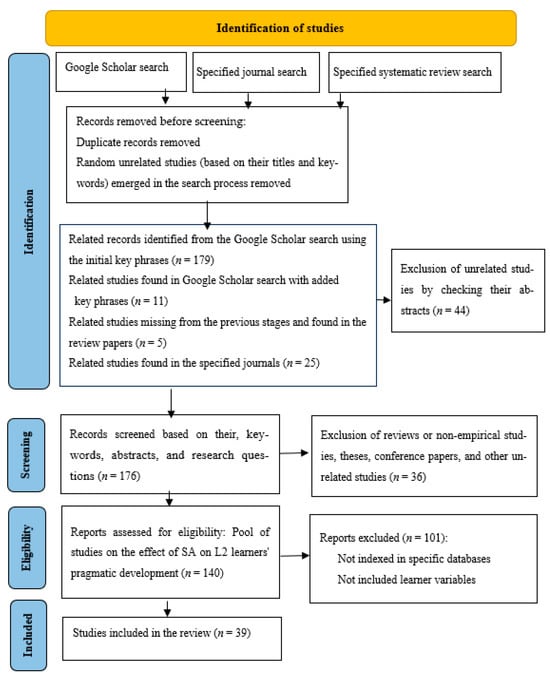

The literature search process was carried out according to the PRISMA guidelines (see Page et al. 2021) and started by searching certain terms and phrases on Google Scholar. First, the search phrases “L2 pragmatics and study abroad” and “L2 pragmatics and individual differences”, which included the keywords and the main topic of this study, were separately searched in Google Scholar, and about 200 studies that appeared on the first 20 pages for each key phrase of this search engine were considered. However, the search process revealed that some studies could not be found using the abovementioned key phrases as the titles of some studies did not include the combinations of the keywords; therefore, two other key phrases, namely “study abroad and speech act” and “study abroad and implicatures”, were individually searched. Also, some new studies which were not found in the previous stage were added. Next, the papers analyzed in two comprehensive and recent review studies on developing L2 pragmatics in SA (Nightingale and Alcón-Soler 2023; Ren 2018) and a review on the role of individual differences and L2 pragmatic development in SA (Wyner and Cohen 2015) were checked and added to the collected studies. Additionally, in case a related study was left in the last stages, we used the keywords “study abroad” to locate relevant studies in six main pragmatics-specific journals published by renowned publishers in the field of applied linguistics, namely, Lodz Papers in Pragmatics, Journal of Pragmatics, Pragmatics, Intercultural Pragmatics, East Asian Pragmatics, Applied Pragmatics, and Contrastive Pragmatics, as these journals have been observed to present high-quality research papers in the area of pragmatics. Furthermore, to find more related articles, all eight volumes of the journal of Study Abroad Research in Second Language Acquisition and International Education were scrutinized due to the similarity of this journal’s research focus with the current systematic review. In the next step, duplicate records as well as unrelated studies that emerged in the search process were excluded. A total of 220 studies remained, which included 179 studies found on the Google Scholar search using the initial key phrase, 11 studies found in Google Scholar search with added key phrases, 5 related studies in the review papers, and 25 related studies found in the specified journals. Finally, 44 studies that were not included within the scope of the current systematic review were excluded through analyzing their abstracts.

It should be noted that the studies were limited to journal articles and book chapters reporting on empirical studies; therefore, review papers, meta-analyses, conference papers, reports, and dissertations were not included (n = 36). Moreover, we restricted our analysis to papers in peer-reviewed journals published by some of the leading international publishers, such as Taylor and Francis, Sage, Springer, Elsevier, Wiley, Cambridge University Press, Oxford University Press, De Gruyter, JSTOR, John Benjamins, and Frontiers, or papers indexed by Scopus, ERIC, and Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI). Removing studies that did not explore learner variables led to the exclusion of 101 records. The final stage of identification of studies, which required delimiting our scope to studies investigating the role of learner variables in L2 pragmatic development in study abroad, was carried out by examining the titles, keywords, abstracts, and research questions of the studies. Figure 1 depicts our search and screening process, which took place from December 2022 to January 2023.

Figure 1.

Study search and exclusion flow chart.

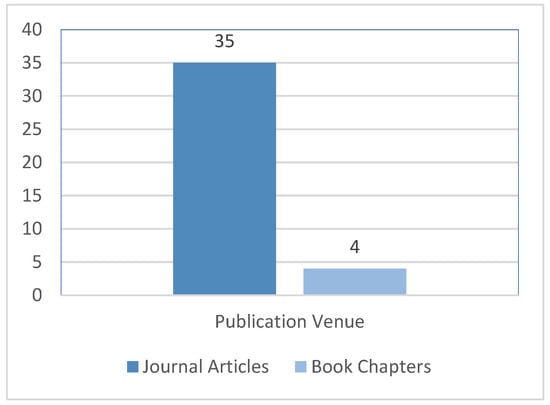

As illustrated in Figure 2, out of the 39 studies included in the current review, 35 were published in peer-reviewed journals and 4 of them were book chapters. Furthermore, the journal articles were selected from a wide range of journals (24 different journals) in the field of applied linguistics and education (Table 1). However, some journals, namely, Journal of Pragmatics and System, contributed the most to our pool of studies, followed by other journals such as Intercultural Pragmatics, The Modern Language Journal, East Asian Pragmatics, Study Abroad Research in Second Language Acquisition and International Education, and English Language Teaching. The remaining studies appeared across 17 different journals.

Figure 2.

Frequency of the studies in journals and book chapters.

Table 1.

Research distribution in different journals.

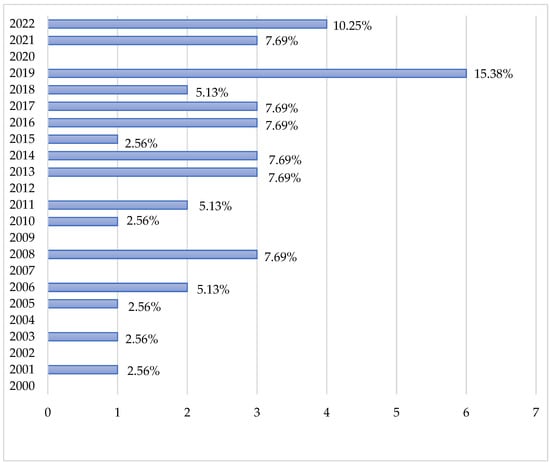

Through the process of selection, we limited our scope to studies published between 2000 to 2022 (Figure 3). However, as indicated in Figure 3, no studies were found in some years during this period, and limited research (23%) on the effects of learner variables on the development of L2 learners’ pragmatic competence was published in the first decade (2000–2010), except in 2008, and the majority of the studies (53.8%) were published from 2016 onward.

Figure 3.

Frequency of the studies in each year (2000–2022).

3.2. Coding and Analysis

This systematic review embarked on investigating the role of learner variables in pragmatic competence whilst learners stay abroad; thus, after selecting our pool, the relevant information was extracted from the studies. First, the research distribution of the collected studies such as the type of study, their publication date, macro- and micro-contexts (the countries and the education centers such as universities, schools, and language institutes where the studies were conducted), and publication venues were analyzed to have a better overview of the conducted studies.

Next, the methodological characteristics of the studies including the research design, number of participants, data collection methods, the use of Discourse Completion Tasks (DCTs) and its variations, data analysis techniques, learners’ L1s and L2s, and learners’ age range were explored and coded into different categories. The explanation of each code and their frequency in the studies are provided in more detail in the result section. Consequently, the analyzed learner variables were extracted and coded, and their reported effects were categorized and compared. The analyzed learner variables in the studies were divided into two categories: personal variables and social and psychological variables. The effectiveness of each variable was explained and discussed in the abstract or result sections of the corpus studies. The variables that were found to have significance on the learners’ pragmatic development during SA programs were coded as effective and those that were reported to have no significance were labeled as not effective during the coding process. It should be noted that the required information was first extracted from the studies and transferred to an Excel file. Afterward, the frequency of each code was calculated. The analyzed variables of the studies and the coding map are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Analyzed variables’ coding scheme.

Finally, to ensure the reliability of the coding process, about 10 percent of the data selected randomly were re-coded by another researcher in the field. The interrater reliability of the two sets of codes was calculated using Cohens’ Kappa, which signified a good level of agreement (K value = 0.8).

4. Results

4.1. Methodological Characteristics

The first research question set out to explore the methodological characteristics of the previous research on the role of learners’ variables on their development of pragmatic competence whilst studying abroad. Starting with the design of the studies, the designs of the studies were categorized into three types: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods. The qualitative category refers to purely qualitative research in terms of both data collection and analysis. The quantitative category includes studies that are purely quantitative regarding their data collection and analysis. Finally, the mixed-method category included studies that both explicitly mentioned that they followed a mixed methodology or those that employed a combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis. As summarized in Table 3, the majority of the studies embarked on the mixed-method (51.28%) and quantitative approaches (41.02%) as their designs, while the qualitative design was used in a small number of studies (7.69%).

Table 3.

Design of the studies.

Table 4 depicts the number of participants included in the SA programs of our study pool. It is important to note that the given information refers to the number of individuals who participated in the abroad programs, and the control groups or those who studied at home contexts are not considered. Evidently, more than half of the studies were conducted with 31 participants or more (53.84%), and 33.33% were conducted with 1–15 L2 learners. Studies with 16–30 participants were the least frequent ones (12.82%) in our pool.

Table 4.

Number of the participants included in SA programs in the studies.

To present a more vivid picture of the design of the studies and the number of participants, Table 5 illustrates the intersection of these two variables. Most of the quantitative studies (12 out of 16) were conducted with 31 or more participants, while qualitative and mixed-method studies, due to their nature, included a more limited number of participants. More precisely, studies that followed mixed-method designs employed different numbers of participants as nine of them were conducted with 1–15 participants, nine included more than 31 learners, and two of them included 16–30 participants. Not surprisingly, all three of the qualitative studies were conducted with 1–15 participants.

Table 5.

Crosstabulation of number of the participants and design of the studies.

Regarding the participants’ age groups, as shown in Table 6, nearly 80% of the studies focused on adult language learners, 2.54% of them included learners below 18 years old, and 5.12% were conducted with participants of different age groups. In addition, 12.82% of the studies did not provide any information about the participants’ age.

Table 6.

The age group of the participants in the studies.

As for the contexts of the studies, that is participants’ home countries and the target countries where they spent their abroad programs, most of the participants (33.33%) were Americans who traveled abroad for language learning (see Table 7). Japanese SA students (10.25%) were the second most frequent L2 learners, followed by Chinese (5.12%), Australians (5.12%), and Iranians (2.12%). Spain, the UK, Italy, and Brazil each were home countries of 2.56% of the studies. However, 25.64% of the participants in the studies were selected from different countries (a combination of countries); that is, the studies were carried out by participants from multiple countries.

Table 7.

Contexts of the studies.

Regarding the target countries hosting SA students, the USA and China were the most preferred destinations for L2 learners, each targeted in 23.07% of the studies. The UK was the second preferred SA context for learners, which was explored in 7.69% of the studies. The other countries including Spain, Mexico, Indonesia, Australia, and Japan each were the target countries in 5.12% of the studies. France, Argentina, India, Russia, Malaysia, and Canada were among the least studied target countries (2.56%). Additionally, two studies (5.12%) divided their participants into different categories and sent each to different SA destinations. For instance, in one study, the participants were sent to Spain and Latin American countries, and in another one, they spent their SA program in English-speaking countries such as the UK, Ireland, the USA, and Canada.

Quite in line with participants’ home countries and SA contexts were their L1s and target languages. As summarized in Table 8, 30.76% of the studies focused on native English speakers as their participants. Meanwhile, Japanese and Chinese L1 speakers were included in 10.25% and 7.69% of the studies, respectively. English was also the most frequently studied L2 as it constituted 46.15% of the investigated target languages. Chinese and Spanish were the second and third most popular L2 studied in 23.07% and 15.38% of the research, respectively. The native English speakers indicated in Table 8 were participants from the USA, the UK, and Australia, and those who studied English as L2 stayed in the USA, the UK, Australia, Canada, Malaysia, and India during their study-abroad programs.

Table 8.

First and target languages investigated in the studies.

Aside from the macro-contexts presented in Table 7, the micro-contexts of the studies, which were the education centers that the participants were selected from, are coded and summarized in Table 9. The majority of the studies (74.35%) focused on L2 learners who were participating in the SA programs organized and conducted at universities or colleges. Far fewer studies (12.82%) were conducted with language institute learners, and only about 7.69% of them selected their participant learners from different contexts. The educational contexts of 5.12% of the studies were not specified in the papers.

Table 9.

Micro-contexts of the studies.

Furthermore, the proficiency levels of the participants included in the studies were coded and analyzed. The coding of participants’ proficiency levels was decided based on the information provided by the researchers in the participant section of the corpus studies. As shown in Table 10, the majority of the studies (about 60%) tended to include different groups of language learners (mostly a combination of intermediate and advanced learners), while only a few studies (10.25%) specifically focused on elementary language learners.

Table 10.

Proficiency levels of the participants in the studies.

The main data sources of the studies are presented in Table 11. Adapting Hyland’s (2016) classification of data sources, the types of data collected through different methods were divided into four categories: elicitation, introspection, observation, and text. Elicitation included self-reports, questionnaires, interviews, and different forms of tests (including different variations of discourse completion tasks). Introspection and retrospection refer to verbal or written reports including think-aloud protocols, retrospective reports, interviews entailing retrospective reports, and diaries. Observation involves the data of participants’ live or recorded interactions. Finally, text refers to the records of naturally produced samples of writing such as single or chains of chats and corpora. The result of our analysis, as demonstrated in Table 11, revealed that elicitation techniques such as tests and questionnaires were the most prevalent data sources and employed in 76.92% of the studies. Moreover, 23.07% of the studies resorted to other data sources, such as introspection and retrospection or texts as well and complemented their data by mixing multiple data sources.

Table 11.

Types of data sources in the studies.

Since DCT has been the most frequent elicitation technique for data sources and to provide a more vivid picture of the employed data, Table 12 illustrates the frequency and types of DCT used in the studies. In general, different forms of DCTs were used as the main or only data collection technique in 38.46% of the studies. WDCTs, which were the most common form of DCT, were employed in 23.1% of the studies, and CDCTs, rarely used from 2016 onward, appeared in 10.3% of the studies. Furthermore, ODCT and MDCT were only used in 2.6% of the studies. Nonetheless, three of the four CDCTs were, in fact, DCTs in that they were implemented via the computer.

Table 12.

Frequency of types of DCTs in the studies.

Moreover, various pragmatic aspects targeted in the studies were coded (Table 13). Speech acts were the leading pragmatic aspect in this group, which was explored in 35.89% of the studies. The next commonly studied pragmatic aspects were formulaic expressions and routines (17.94%). Discourse/pragmatic markers, such as particles and choice of subject pronouns, and lexico-grammatical features, such as specific grammatical structures that have particular functions, each were targeted in 12.82% of the studies. Implicatures and learners’ general pragmatic competence appeared in 7.96% and 10.25% of the studies, respectively.

Table 13.

Different pragmatic aspects targeted in the studies.

4.2. Learner Variables

The second research question, which was the main aim of this systematic review, sought to portray the investigated learner variables and their roles in pragmatic development during sojourn abroad. The majority of the studies analyzed in this review (92.3%) did not include pragmatic instruction per se and did not consider the role of learner variables in the specific types of pragmatic instruction. The main instructions that the participants received included general L2 courses as a part of their SA programs with no mention of L2 pragmatic instruction. In general, 14 different learner variables were found in our pool of 39 studies. Given their theoretical ground and related literature (Ellis 2004; Gardner 1985), these variables were categorized into two main groups: personal variables and social and psychological variables. Personal variables included proficiency level, gender, language background, and study-abroad experiences, shown in Table 14. Social and psychological variables consisted of, among others, motivation, identity and agency, ICC and other cultural factors, attitude, cognitive processing, learning goals, learners’ status in the target community, desire to be accepted in the target community, learning styles, and willingness to communicate (Table 15).

Table 14.

Learners’ personal variables investigated in the studies.

Table 15.

Social and psychological variables investigated in the studies.

As depicted in Table 14, learners’ language proficiency was the most frequently studied variable that emerged in 19 out of the 39 studies (e.g., Kizu et al. 2019, 2022; Li et al. 2022). Reportedly, language proficiency was an effective variable in more than half of these studies (n = 10) and was found to have a facilitative role in learners’ pragmatic development while studying abroad altogether. However, the outperformance of less proficient L2 learners in recognizing pragmatic errors was observed in Niezgoda and Röver (2001). Also, language proficiency was reported to have no effect on learners’ pragmatic development in four studies (e.g., Alcón-Soler and Sánchez Hernández 2017; Quan 2018). In addition, some studies (n = 5) reported only partial effectiveness of language proficiency in developing learners’ L2 competence or found it to be effective for developing certain aspects of L2 pragmatics (e.g., Li et al. 2022; Sánchez-Hernández and Alcón-Soler 2019b); therefore, three codes were considered for this variable, as opposed to other personal and social and psychological variables whose effects were coded into two categories. It should be noted that some of the studies explored the effects of learners’ increased language proficiency, that is the ability they gained during their SA experience, on their pragmatic gains (e.g., Matsumura 2003; Yang 2016).

On the other hand, no effects were reported for learners’ genders, and all three studies that targeted this variable did not report its correlation with L2 pragmatic development (Liao 2009; Rasouli Khorshidi 2013; Shively and Cohen 2008). Unlike gender, the positive effects of individuals’ language background, for instance, the effect of their first language or any additional acquired languages, were found positive in all three studies that explored it (e.g., Liu 2017; Pozzi et al. 2021). Furthermore, previous living abroad experience, as the least studied variable in this category, was only mentioned in one study, which was reported to have no effect (Shively and Cohen 2008).

As for social and psychological variables (Table 15), learners’ cultural factors such as their ICC level, cultural similarities between L1 and L2 communities, and sociocultural adaptation were examined in six of the studies (e.g., Sánchez-Hernández 2018; Sánchez-Hernández and Alcón-Soler 2019a, 2019b; Shively and Cohen 2008) and were found to be effective in learners’ pragmatic development in most studies (e.g., Sánchez-Hernández 2018; Sánchez-Hernández and Alcón-Soler 2019a, 2019b). However, in some studies, the effects of cultural factors were indirect and bounded by other variables such as learners’ social contacts with the target community (e.g., Taguchi et al. 2016). The effects of learners’ identity and agency were explored in six studies, which turned out to be influential in all of them (e.g., Liu et al. 2022; Pozzi et al. 2021; Ying and Ren 2022). It should be noted that learners’ developed identities and their relationships with individuals’ pragmatic development were influenced by a range of other factors such as learners’ attitudes toward L2, L2 community (Liao 2009), and their internalized cultural values (Liu et al. 2022). Motivation as an important affective factor was investigated in four studies in our pool and was found to have positive effects on learners’ development (e.g., Inagaki 2019; Jin 2015; Kizu et al. 2022). Furthermore, learners’ attitudes toward the target communities, their culture, and languages were reported as another effective learner variable for pragmatic development in SA in four studies (e.g., Rafieyan 2016; Sánchez-Hernández and Alcón-Soler 2019b). The concept of attitude was closely related to individuals’ identities and ICC level as highlighted in some of the studies (Liao 2009; Rafieyan et al. 2013; Rafieyan 2016). In fact, in two of the studies (Rafieyan 2016; Rafieyan et al. 2013), the authors investigated learners’ acculturation level and referred to it as their acculturation attitude toward the target language community in their analysis.

Other understudied learner variables such as cognitive processing (Taguchi 2008), learning goals (Pozzi et al. 2021), learners’ status in the host community (Magliacane and Howard 2019), desire to be accepted in the target community (Alcón-Soler 2017), learning styles (Kizu et al. 2022), and willingness to communicate (Lv et al. 2021) each were investigated only in one study, and except for willingness to communicate, all of them were described as effective.

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to offer new insights into the role of L2 learners’ traits on their pragmatic competence development during SA programs. To this end, first, the methodological characteristics of 39 studies on this topic were explored as they could contribute to the outcomes of the studies and have significant implications in pragmatics and SA research. Next, the effects of each variable in these studies were reviewed. Additionally, the methodological characteristics and contexts of these studies were scrutinized and reported. The results are summarized and discussed accordingly.

Regarding the dominant research designs, our findings suggest that more than half of the studies employed a mixed-method research design that combined quantitative and qualitative measures. Moreover, unlike the qualitative design, which appeared only in three studies, quantitative research was also used abundantly in the studies we reviewed. According to Taguchi (2018b), mixed-method research is a promising trend in L2 pragmatic studies as it can reveal learners’ gradual patterns of change and divulge individual and contextual factors influencing the observed patterns simultaneously. However, she believes that there has been a dearth of mixed-method research in the area of pragmatic acquisition, which cannot be supported in our review. Moreover, it was found that elicitation techniques, especially DCTs, are commonly used in pragmatic studies (also see Bardovi-Harlig 2018). In fact, the overuse of instruments that are based on elicitation techniques such as DCT for speech act studies has been observed in previous research as well (Nurani 2009; Yamashita 2008), and their reliability and validity were recurrently questioned (Labben 2016; Yamashita 2008); yet, due to their practicality and established position among other pragmatic data collection instruments, it is still being used in many studies (Bardovi-Harlig 2018). It should be noted that the choice of data collection instruments can have substantial effects on the results of the studies (Roever et al. 2023; Xiao et al. 2019).

Regarding the context of the studies, previous studies have shown that the majority of SA programs have been skewed toward American students (Ren 2019). The same trend has somewhat been evidenced in the choice of L1 and L2 in previous pragmatic research. Our analysis suggests the predominance of English as L1 and L2 in the SLA literature. Similarly, the literature on L2 pragmatics and SA studies has shown an abundance of research on English as the target language, followed by Spanish (Ren 2018, 2019). This is of importance, especially when it comes to the generalizability and interpretations of the findings, as different L2 along various other arrangements of SA programs can have dramatic influences on learners’ pragmatic development (Ren 2019).

Another issue found in the methodological choices of the studies was an overemphasis on intermediate and advanced levels and a limited amount of research on lower-level learners. Apparently, a high level of language proficiency is considered a prerequisite for many L2 pragmatic studies, not to mention those conducted in SA contexts; therefore, they tried to include learners who had reached a certain level of L2 proficiency before undergoing their pragmatic instructions (Ren 2019). However, delimiting pragmatic instruction and research to higher-proficiency level learners can also end in neglecting its teaching and practice among younger L2 learners. It has been found that almost all of the studies focused on adult learners. This can be partly due to the nature of SA programs, which require individuals to spend a considerable period away from their families and home countries. Yet, as the literature suggests, this is not only the case for SA research, and in general, studies on young learners’ pragmatic competence and development have not received due attention (Alemi and Haeri 2020; Schauer 2022).

Aside from the methodological considerations, the impacts of individual difference factors or variables were addressed in the current review. As argued by Sánchez-Hernández and Alcón-Soler (2019b), a variety of contextual and personal factors can affect learners’ development process as they are studying abroad. Regarding the role of language proficiency, findings from previous studies are quite mixed. A large body of research has reported the significant effects of language proficiency on learners’ pragmatic development (Roever et al. 2014, 2023; Taguchi 2011; Xiao et al. 2019). In contrast, some studies evidenced the insignificance of language proficiency either at home (Taguchi 2013) or study-abroad contexts (Matsumura 2003). The analysis of 19 studies that have considered this factor in the SA context revealed that 15 studies have documented full or partial effects of language proficiency. Furthermore, Li et al. (2022), in one of our reviewed studies, reported a complex relationship between proficiency and the choices of speech act as well as some assessment factors such as performance measures and measures that evaluate pragmatic changes. In all cases, except one (Niezgoda and Röver 2001), this effect has been positive and contributed to learners’ progress. However, as highlighted by Roever et al. (2023), the degree of this contribution is highly bounded by the area of pragmatics investigated and measurement instruments used in the studies (also see Xiao et al. 2019).

Other variables have received scant attention as compared with language proficiency, although more conclusive findings that have been previously confirmed in other studies have been reported (Ren 2018; Sánchez-Hernández and Alcón-Soler 2019b). For instance, the analysis of the role of gender addressed in a few of the studies reviewed indicates the insignificance of this variable. In fact, despite the reported role of gender in learners’ attitudes and identities during their sojourn abroad (Kinginger 2011), not much effect has been observed regarding its role in students’ pragmatic development (Derakhshan et al. 2023; Tajeddin and Malmir 2014; for an exception, see Roever et al. 2014). Additionally, the role of learners’ previous backgrounds and living abroad experiences was scrutinized. Compared with their prior living abroad experiences, learners’ linguistic backgrounds, including their L1s and repertoire of other languages, unraveled more solid effects. The analysis of the effects of living abroad experiences has shown mixed findings in general (Taguchi 2011). However, empirical research on the effects of previous living abroad experiences on L2 pragmatic competence is largely limited.

Cultural factors and learners’ ICC were among the other analyzed variables. Evidently, learners’ cultural issues are operative factors in their L2 pragmatic development as they are highly intertwined with each other; thus, among six studies that considered this variable, five reported its significance. Despite a few contradictory findings (Shively and Cohen 2008), many researchers attest to the close relationship between ICC and pragmatics and believe that improving one’s pragmatic competence can lead to an enhanced ICC level (Jackson 2019; Taguchi and Roever 2017). Furthermore, the absolute effectiveness of learners’ identity has been proved in all six studies that investigated it. Identity as a learner variable is believed to be associated with pragmatics and sociocultural factors (Ishihara 2019). So far, learners’ pragmatic productions and choice of assimilation with L2 cultural and pragmatic norms have signified their identity and agency (e.g., Eslami et al. 2014; Ishihara 2010). Nonetheless, learners’ identity is mediated by a variety of other individual factors such as gender and cultural orientations (Ishihara 2019; Mirzaei and Parhizkar 2021; Tulgar 2019). In addition to identity, learners’ attitudes in the SA context, although not targeted in many studies, have turned out as one of the decisive factors, as previously evidenced in several studies (e.g., Davis 2007; Salsbury and Bardovi-Harlig 2001). Moreover, motivation is another predicting factor. This psychological factor is believed to be connected with learners’ attitudes and ICC (Ishihara 2019). The literature suggests that learners with stronger motivation, either intrinsic or communication-oriented, are more successful in the comprehension and production of L2 pragmatics (Tagashira et al. 2011; Tajeddin and Zand Moghadam 2012; Takahashi 2015).

Finally, it is worth noting that the interplay of different variables, including both individual differences and contextual factors, should be taken into account (Ren 2019), before interpreting the findings and incorporating pragmatics into L2 courses. For instance, one of the studies in our review (Taguchi et al. 2016) referred to this point by reporting the effectiveness of cross-cultural adaptability on L2 pragmatics when it is mediated by the amount of social contact. Additionally, the relationship between learners’ attitudes toward the target language, culture, or community and their identities and ICC was discussed by some researchers (Liao 2009; Rafieyan 2016).

6. Conclusions and Suggestions for Further Research

This systematic review was undertaken to scrutinize the literature on the impacts of a variety of learner variables on pragmatic performance and development during their sojourn abroad. The analysis of 39 studies illuminated some methodological preferences in pragmatic studies in general, as well as the main findings on the nexus of L2 pragmatics and SA. From the findings, it can be concluded that the literature lacks the necessary variation in designs, participant groups, study contexts, and data sources. Therefore, future studies need to consider this to enhance the quality of the research on learner variables in pragmatic development during SA.

The considerable range of research, despite the insufficient number of studies, on personal and social/psychological learner variables contributes to our understanding of effective factors in SA programs that have been organized to improve individuals’ pragmatic competence. Becoming aware of the effects of learners’ variables on the outcome of the SA programs for pragmatic development is beneficial for institutional authorities who conduct such courses as well as teachers who deal with SA students and aim to improve the productivity of these programs.

The studies reviewed have evidenced a few limitations. The distribution of studies on these variables has been uneven and hence more studies are needed on some variables such as learners’ previous living abroad experiences, cognitive processing, learning styles, and many other social and psychological characteristics. Furthermore, although some learner variables such as linguistic proficiency have been extensively studied in L2 pragmatics, mixed findings hinder us from drawing solid conclusions. Nonetheless, variations in the contexts of studies, learners’ L1s and L2s, and the employed assessment techniques, among others, all in all, make extrapolation from the findings challenging. L2 researchers need to delve into this area and consider exploring a wider range of learner variables. It is also recommended that future research explore different areas of L2 pragmatic development as the majority of the studies focused on the production and comprehension of speech acts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.T.; Methodology, Z.T. and N.K.; Formal analysis, Z.T. and N.K.; Resources, N.K.; Writing—original draft, N.K.; Writing—review & editing, Z.T.; Visualization, N.K.; Supervision, Z.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Al Masaeed, Khaled. 2022. Bidialectal Practices and L2 Arabic Pragmatic Development in a Short-Term Study Abroad. Applied Linguistics 43: 88–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcón-Soler, Eva. 2015. Pragmatic learning and study abroad: Effects of instruction and length of stay. System 48: 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcón-Soler, Eva. 2017. Pragmatic development during study abroad: An analysis of Spanish teenagers’ request strategies in English emails. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 37: 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcón-Soler, Eva, and Ariadna Sánchez Hernández. 2017. Learning pragmatic routines during study abroad: A focus on proficiency and type of routine. Atlantis 39: 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemi, Minoo, and Nafiseh S. Haeri. 2020. Robot-assisted instruction of L2 pragmatics: Effects on young EFL learners’ speech act performance. Language Learning & Technology 24: 86–103. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/44727 (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Avgousti, Maria I. 2018. Intercultural communicative competence and online exchanges: A systematic review. Computer Assisted Language Learning 31: 819–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardovi-Harlig, Kathleen. 2018. Matching modality in L2 pragmatics research design. System 75: 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardovi-Harlig, Kathleen, and Maria-Thereza Bastos. 2011. Proficiency, length of stay, and intensity of interaction and the acquisition of conventional expressions in L2 pragmatics. Intercultural Pragmatics 8: 347–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardovi-Harlig, Kathleen, and Yunwen Su. 2018. The acquisition of conventional expressions as a pragmalinguistic resource in Chinese as a foreign language. The Modern Language Journal 102: 732–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, Anne. 2019. Using corpus-linguistic methods to track longitudinal development: Routine apologies in the study abroad context. Journal of Pragmatics 146: 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bella, Spyridoula. 2011. Mitigation and politeness in Greek invitation refusals: Effects of length of residence in the target community and intensity of interaction on non-native speakers’ performance. Journal of Pragmatics 43: 1718–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, An Chung, and Clara C. Mojica-Diaz. 2006. The effects of formal instruction and study abroad on improving proficiency: The case of the Spanish subjunctive. Applied Language Learning 16: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornillie, Frederik, Geraldine Clarebout, and Piet Desmet. 2012. Between learning and playing? Exploring learners’ perceptions of corrective feedback in an immersive game for English pragmatics. ReCALL 24: 257–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwionka, Lori, and Alejandro Cuza. 2017. A pragmatic analysis of L2 Spanish requests: Acquisition in three situational contexts during short-term study abroad. Intercultural Pragmatics 14: 391–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, John McE. 2007. Resistance to L2 pragmatics in the Australian ESL context. Language Learning 57: 611–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhshan, Ali, Ali Malmir, Mirosław Pawlak, and Yongliang Wang. 2023. The use of interlanguage pragmatic learning strategies (IPLS) by L2 learners: The impact of age, gender, language learning experience, and L2 proficiency levels. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, Anne Marie. 2019. The interaction between duration of study abroad, diversity of loci of learning and sociopragmatic variation patterns: A comparative study. Journal of Pragmatics 146: 121–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiBartolomeo, Megan, Vanessa Elias, and Daniel Jung. 2019. Investigating the effects of pragmatic instruction: A comparison of L2 Spanish compliments and apologies during short term study abroad. Letrônica 12: e33989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán. 2005. The Psychology of the Language Learner. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- DuFon, Margaret Ann. 1999. The Acquisition of Linguistic Politeness in Indonesian by Sojourners in Naturalistic Interactions. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Economidou-Kogetsidis, Maria. 2016. Variation in evaluations of the (im) politeness of emails from L2 learners and perceptions of the personality of their senders. Journal of Pragmatics 106: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Rod. 2004. Individual differences in second language learning. In The Handbook of Applied Linguistics. Edited by Alan Davies and Catherine Elder. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 525–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, Rod, and Natsuko Shintani. 2013. Exploring Language Pedagogy through Second Language Acquisition Research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Eslami, Zohreh R., Heekyoung Kim, Katherine L. Wright, and Lynn M. Burlbaw. 2014. The role of learner subjectivity in Korean English language learners’ pragmatic choices. Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 10: 117–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix-Brasdefer, J. César, and Maria Hasler-Barker. 2015. Complimenting in Spanish in a short-term study abroad context. System 48: 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, Robert C. 1985. Social Psychology and Second Language Learning: The Role of Attitudes and Motivation. London: Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, David, Sandy Oliver, and James Thomas. 2013. Learning from Research: Systematic Reviews for Informing Policy Decisions: A Quick Guide. A Paper for the Alliance for Useful Evidence. London: Nesta. [Google Scholar]

- Halenko, Nicola. 2017. Evaluating the Explicit Pragmatic Instruction of Requests and Apologies in a Study Abroad Setting: The Case of Chinese ESL Learners at a UK Higher Education Institution. Lancaster: Lancaster University. [Google Scholar]

- Hassall, Tim. 2013. Pragmatic development during short-term study abroad: The case of address terms in Indonesian. Journal of Pragmatics 55: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassall, Tim. 2014. Individual variation in L2 study-abroad outcomes: A case study from Indonesian pragmatics. Multilingua 34: 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, Todd A. 2010. The relationship among motivation, interaction, and the development of second language oral proficiency in a study-abroad context. The Modern Language Journal 94: 600–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, Todd A. 2018. Language practice and study Abroad. In Practice in Second Language Learning. Edited by Christian Jones. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 197–227. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, Tod A., and Paulo Boero. 2018. Explicit intervention for Spanish pragmatic development during short-term study abroad: An examination of learner request production and cognition. Foreign Language Annals 51: 389–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, Ken. 2016. Methods and methodologies in second language writing research. System 59: 116–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, Akiko. 2019. Pragmatic development, the L2 motivational self-system, and other affective factors in a study-abroad context: The case of Japanese learners of English. East Asian Pragmatics 4: 145–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, Noriko. 2010. Maintaining an optimal distance: Nonnative speakers’ pragmatic choice. In The NNEST Lens: Nonnative English Speakers in TESOL. Edited by Ahmar Mahboob. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, Noriko. 2019. Identity and agency in L2 pragmatics. In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition and Pragmatics. Edited by Naoko Taguchi. London: Routledge, pp. 161–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, Noriko, and Yumi Takamiya. 2019. Pragmatic development through blogs: A longitudinal study of telecollaboration and language socialization. In Computer-Assisted Language Learning: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications. Edited by Carolin Fuchs. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 829–54. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki, Noriko. 2010. Style shifts among Japanese learners before and after study abroad in Japan: Becoming active social agents in Japanese. Applied Linguistics 31: 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Jane. 2019. Intercultural competence and L2 pragmatics. In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition and Pragmatics. Edited by Naoko Taguchi. London: Routledge, pp. 479–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan, Justin. 2012. Output and English as a second language pragmatic development: The effectiveness of output-focused video-based instruction. English Language Teaching 5: 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jin, Li. 2015. Developing Chinese complimenting in a study abroad program. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics 38: 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinginger, Celeste. 2011. English language learning in study abroad. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 31: 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizu, Mika, Barbara Pizziconi, and Eiko Gyogi. 2019. The particle ne in the development of interactional positioning in L2 Japanese. East Asian Pragmatics 4: 113–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizu, Mika, Eiko Gyogi, and Patrick Dougherty. 2022. Epistemic stance in L2 English discourse: The development of pragmatic strategies in study abroad. Applied Pragmatics 4: 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labben, Afef. 2016. Reconsidering the development of the discourse completion test in interlanguage pragmatics. Pragmatics 26: 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Chengchen. 2022. Foreign language learning boredom and enjoyment: The effects of learner variables and teacher variables. Language Teaching Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Shuai. 2014. The effects of different levels of linguistic proficiency on the development of L2 Chinese request production during study abroad. System 45: 103–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Shuai, Xiaofei Tang, Naoko Taguchi, and Feng Xiao. 2022. Effects of linguistic proficiency on speech act development in L2 Chinese during study abroad. Study Abroad Research in Second Language Acquisition and International Education 7: 116–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Silvie. 2009. Variation in the use of discourse markers by Chinese teaching assistants in the US. Journal of Pragmatics 41: 1313–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsey, Mark W., and David B. Wilson. 2001. Practical Meta-Analysis. New York: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Binmei. 2017. The use of discourse markers but and so by native English speakers and Chinese speakers of English. Pragmatics 27: 479–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, Xiaowen, Martin Lamb, and Gary N. Chambers. 2022. Bidirectional relationship between L2 pragmatic development and learner identity in a study abroad context. System 107: 102823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Xiaoxuan, Wei Ren, and Lin Li. 2021. Pragmatic competence and willingness to communicate among L2 learners of Chinese. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 797419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliacane, Annarita, and Martin Howard. 2019. The role of learner status in the acquisition of pragmatic markers during study abroad: The use of ‘like’ in L2 English. Journal of Pragmatics 146: 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnan, Sally Sieloff, and Michele Back. 2006. Requesting help in French: Developing pragmatic features during study abroad. In Insights from Study Abroad for Language Programs. Edited by Sharon Wilkinson. Boston: Heinle, pp. 22–44. [Google Scholar]

- Malmir, Ali, and Ali Derakhshan. 2020. The socio-pragmatic, lexico-grammatical, and cognitive strategies in L2 pragmatic comprehension: The case of Iranian male vs. female EFL learners. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research 8: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marqués-Pascual, Laura. 2011. Study abroad, previous language experience, and Spanish L2 development. Foreign Language Annals 44: 565–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, Emma, Kara Morgan-Short, Sophie Thompson, and David Abugaber. 2018. Replication in second language research: Narrative and systematic reviews and recommendations for the field. Language Learning 68: 321–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, Shoichi. 2003. Modelling the relationships among interlanguage pragmatic development, L2 proficiency, and exposure to L2. Applied Linguistics 24: 465–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, Shoichi. 2022. The impact of predeparture instruction on pragmatic development during study abroad: A learning strategies perspective. Study Abroad Research in Second Language Acquisition and International Education 7: 152–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, Azizullah, and Reza Parhizkar. 2021. The Interplay of L2 Pragmatics and Learner Identity as a Social, Complex Process: A Poststructuralist Perspective. TESL-EJ 25: n1. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1302585.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Niezgoda, Kimberly, and Carsten Röver. 2001. Pragmatic and grammatical awareness: A function of the learning environment. In Pragmatics in Language Teaching. Edited by Kenneth R. Rose and Gabriele Kasper. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale, Richard, and Eva Alcón-Soler. 2023. Investigating pragmatic development in study abroad contexts. In Methods in Study Abroad Research: Past, Present, and Future. Edited by Carmen Pérez-Vidal and Cristina Sanz. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 265–89. [Google Scholar]

- Nurani, Lusia Marliana. 2009. Methodological issue in pragmatic research: Is discourse completion test a reliable data collection instrument? Jurnal Sosioteknologi 8: 667–78. Available online: https://journals.itb.ac.id/index.php/sostek/article/view/1028 (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery 372: 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Vidal, Carmen. 2014. Language Acquisition in Study Abroad and Formal Instruction Contexts. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Vidal, Carmen, and Rachel L. Shively. 2019. L2 pragmatic development in study abroad settings. In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition and Pragmatics. Edited by Naoko Taguchi. London: Routledge, pp. 355–71. [Google Scholar]

- Plonsky, Luke, and Jingyuan Zhuang. 2019. A meta-analysis of L2 pragmatics instruction. In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition and Pragmatics. Edited by Naoko Taguchi. London: Routledge, pp. 287–307. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi, Rebecca, Chelsea Escalante, and Tracy Quan. 2021. The pragmatic development of heritage speakers of Spanish studying abroad in Argentina. In Heritage Speakers of Spanish and Study Abroad. Edited by Rebecca Pozzi, Tracy Quan and Chelsea Escalante. London: Routledge, pp. 117–38. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, Tracy. 2018. Acquisition of formulaic sequences in a study abroad context. Study Abroad Research in Second Language Acquisition and International Education 3: 220–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieyan, Vahid. 2016. Relationship between acculturation attitude and effectiveness of pragmatic instruction. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies 4: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rafieyan, Vahid, Norazman Bin Abdul Majid, and Lin Siew Eng. 2013. Relationship between attitude toward target language culture instruction and pragmatic comprehension development. English Language Teaching 6: 125–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli Khorshidi, Hassan. 2013. Study abroad and interlanguage pragmatic development in request and apology speech acts among Iranian learners. English Language Teaching 6: 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Wei. 2013. The effect of study abroad on the pragmatic development of the internal modification of refusals. Pragmatics 23: 715–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Wei. 2018. Developing L2 pragmatic competence in study abroad contexts. In The Routledge Handbook of Study Abroad Research and Practice. Edited by Cristina Sanz and Alfonso Morales-Front. London: Routledge, pp. 119–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Wei. 2019. Pragmatic development of Chinese during study abroad: A cross-sectional study of learner requests. Journal of Pragmatics 146: 137–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Wei. 2022. Effects of proficiency and gender on learners’ use of the pragmatic marker 吧 ba. Lingua 277: 103405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roever, Carsten, Natsuko Shintani, Yan Zhu, and Rod Ellis. 2023. Proficiency effects on L2 pragmatics. In L2 Pragmatics in Action: Teachers, Learners and the Teaching-Learning Interaction Process. Edited by Alicia Martínez-Flor, Ariadna Sánchez-Hernández and Júlia Barón. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 145–68. [Google Scholar]

- Roever, Carsten, Stanley Wang, and Stephanie Brophy. 2014. Learner background factors and learning of second language pragmatics. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 52: 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, Victoria, and Camilla Vásquez. 2018. Assessing the effectiveness of a web-based tutorial for interlanguage pragmatic development prior to studying abroad. IALLT Journal of Language Learning Technologies 48: 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsbury, Tom, and Kathleen Bardovi-Harlig. 2001. ‘I know your mean, but I don’t think so’: Disagreements in L2 English. In Pragmatics and Language Learning. Edited by Lawrence F. Bouton. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois, Division of English as an International Language, pp. 131–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Hernández, Ariadna. 2018. A mixed-methods study of the impact of sociocultural adaptation on the development of pragmatic production. System 75: 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, Ariadna, and Eva Alcón-Soler. 2019a. Pragmatic gains in the study abroad context: Learners’ experiences and recognition of pragmatic routines. Journal of Pragmatics 146: 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, Ariadna, and Eva Alcón-Soler. 2019b. The role of individual differences on learning pragmatic routines in a study abroad context. In Investigating the Learning of Pragmatics across Ages and Contexts. Edited by Patricia Salazar-Campillo and Victòria Codina-Espurz. Leiden: Brill, pp. 141–64. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-López, Lourdes. 2018. Cultural and pragmatic aspects of L2 Spanish for academic purposes: New data on the current state of the question. Journal of Spanish Language Teaching 5: 102–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, Cristina. 2014. Contributions of study abroad research to our understanding of SLA processes and outcomes. In Language Acquisition in Study Abroad and Formal Instruction Contexts. Edited by Carmen Pérez-Vidal. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Schauer, Gila A. 2022. Teaching L2 pragmatics to young learners: A review study. Applied Pragmatics 4: 137–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shardakova, Maria. 2005. Intercultural pragmatics in the speech of American L2 learners of Russian: Apologies offered by Americans in Russian. Intercultural Pragmatics 2: 423–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shively, Rachel L. 2011. L2 pragmatic development in study abroad: A longitudinal study of Spanish service encounters. Journal of Pragmatics 43: 1818–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shively, Rachel L., and Andrew D. Cohen. 2008. Development of Spanish Requests and Apologies during Study Abroad. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura 13: 57–118. Available online: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=s0123-34322008000200004&script=sci_arttext (accessed on 10 December 2022). [CrossRef]

- Tagashira, Kenji, Kazuhito Yamato, and Takamichi Isoda. 2011. Japanese EFL learners’ pragmatic awareness through the looking glass of motivational profiles. JALT 33: 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, Naoko. 2008. Cognition, language contact, and the development of pragmatic comprehension in a study-abroad context. Language Learning 58: 33–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, Naoko. 2011. The effect of L2 proficiency and study-abroad experience in pragmatic comprehension. Language Learning 61: 904–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, Naoko. 2013. Individual differences and development of speech act production. Applied Research on English Language 2: 1–16. Available online: https://www.sid.ir/en/vewssid/j_pdf/5064020130402.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Taguchi, Naoko. 2014. Cross-cultural adaptability and development of speech act production in study abroad. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 25: 343–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, Naoko. 2018a. Contexts and pragmatics learning: Problems and opportunities of the study abroad research. Language Teaching 51: 124–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, Naoko. 2018b. Description and explanation of pragmatic development: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research. System 75: 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, Naoko, and Carsten Roever. 2017. Second Language Pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi, Naoko, Feng Xiao, and Shuai Li. 2016. Effects of intercultural competence and social contact on speech act production in a Chinese study abroad context. The Modern Language Journal 100: 775–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddin, Zia, and Ali Malmir. 2014. Knowledge of L2 Speech Acts: Impact of Gender and Language Learning Experience. Journal of Modern Research in English Language Studies 1: 1–21. Available online: http://ikiu.ac.ir/public-files/profiles/items/090ad_1481397667.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Tajeddin, Zia, and Amir Zand Moghadam. 2012. Interlanguage pragmatic motivation: Its construct and impact on speech act production. RELC Journal 43: 353–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajeddin, Zia, Neda Khanlarzadeh, and Hessameddin Ghanbar. 2022. Learner variables in the development of intercultural competence: A synthesis of home and study abroad research. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 12: 261–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Satomi. 2015. The effect of learner profiles on pragmalinguistic awareness and learning. System 48: 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Satomi. 2019. Individual learner considerations in SLA and L2 pragmatics. In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition and Pragmatics. Edited by Naoko Taguchi. London: Routledge, pp. 429–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tulgar, Ayşegül T. 2019. Exploring the bi-directional effects of language learning experience and learners’ identity (re)construction in glocal higher education context. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 40: 743–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandergrift, Larry, and Susan Baker. 2015. Learner variables in second language listening comprehension: An exploratory path analysis. Language Learning 65: 390–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyner, Lauren, and Andrew D. Cohen. 2015. Second language pragmatic ability: Individual differences according to environment. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 5: 519–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Feng. 2015a. Adult second language learners’ pragmatic development in the study abroad context: Review. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad 25: 132–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Feng. 2015b. Proficiency effect on L2 pragmatic competence. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 5: 557–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Feng, Naoko Taguchi, and Shuai Li. 2019. Effects of proficiency subskills on pragmatic development in L2 Chinese study abroad. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 41: 469–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Sayoko. 2008. Investigating interlanguage pragmatic ability: What are we testing? In Investigating Pragmatics in Foreign Language Learning, Teaching and Testing. Edited by Eva Alcón-Soler and Alicia Martínez-Flor. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 201–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, He, and Wei Ren. 2019. Pragmatic awareness and second language learning motivation: A mixed-methods investigation. Pragmatics & Cognition 26: 447–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, He, and Xinxin Wu. 2022. Language learning motivation and its role in learner complaint production. Sustainability 14: 10770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Jia. 2016. CFL learners’ recognition and production of pragmatic routine formulae. Chinese as a Second Language 51: 29–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Li, and Chuanren Ke. 2021. Proficiency and pragmatic production in L2 Chinese study abroad. System 98: 102475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Shengli, and Weirong Wang. 2022. The role of academic resilience, motivational intensity and their relationship in EFL learners’ academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 6548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Xinyuan, Li-Jen Kuo, Zohreh R. Eslami, and Stephanie M. Moody. 2021. Theoretical trends of research on technology and L2 vocabulary learning: A systematic review. Journal of Computers in Education 8: 465–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Jieqiong, and Wei Ren. 2022. Advanced learners’ responses to Chinese greetings in study abroad. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 60: 1173–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).