Abstract

Little attention is paid to prosody in second language (L2) instruction, but computer-assisted pronunciation training (CAPT) offers learners solutions to improve the perception and production of L2 suprasegmentals. In this study, we extend with acoustic analysis a previous research showing the effectiveness of self-imitation training on prosodic improvements of Japanese learners of Italian. In light of the increased degree of correct match between intended and perceived pragmatic functions (e.g., speech acts), in this study, we aimed at quantifying the degree of prosodic convergence towards L1 Italian speakers used as a model for self-imitation training. To measure convergence, we calculated the difference in duration, F0 mean, and F0 max syllable-wise between L1 utterances and the corresponding L2 utterances produced before and after training. The results showed that after self-imitation training, L2 learners converged to the L1 speakers. The extent of the effect, however, varied based on the speech act, the acoustic measure, and the distance between L1 and L2 speakers before the training. The findings from perceptual and acoustic investigations, taken together, show the potential of self-imitation prosodic training as a valuable tool to help L2 learners communicate more effectively.

1. Introduction

Prior research on teaching Italian prosody in a classroom setting employing computer-assisted pronunciation training (CAPT) methods has shown that a training approach centered around L2 learners imitating their own voice with native-like prosody (self-imitation) had a beneficial effect on their capacity to produce speech acts with prosody characteristics matching the expectations of native Italian listeners (Pellegrino and Vigliano 2015; Vigliano et al. 2016). The primary aim of this research was to delve deeper into the influence of self-imitation training on the prosodic improvements of Japanese learners of Italian. To this purpose, we quantified acoustically the extent to which (1) L2 learners exhibited prosodic convergence towards the L1 speakers, serving as models during self-imitation prosodic training; (2) the effect of training on prosodic convergence depended on the specific speech act and specific portions of the utterance; and (3) the baseline difference between the L1 models and the learners’ pre-training productions influenced the degree of prosodic convergence in the post-training productions.

The paper is structured as follows: Firstly, we outline the significance of CAPT systems in teaching and learning the prosody of a second language (Section 2). Subsequently, we present a line of research that demonstrates the greater effectiveness of self-imitation prosodic training compared to traditional imitation in enhancing L2 pronunciation (Section 2.1). Specific emphasis is given to studies involving Chinese learners acquiring L2 Italian (Section 2.2). Following that, we delve deeper into the research concerning L2 Italian spoken by Japanese learners (Section 2.2.1), which serves as the foundation for the acoustic analysis of prosodic convergence conducted in this present study (Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5).

2. Learning L2 Prosody with CAPT

Most individuals who speak a second language (L2) tend to exhibit perceivable traces of a ‘foreign accent’ (Moyer 2013). These non-native characteristics encompass aspects such as consonant and vowel articulation (segmental deviations), pitch range, fluency, speech rate, pauses, and rhythm (prosodic deviations) (see a.o., Anderson-Hsieh et al. 1992; Flege et al. 1997; Kang 2010; Trofimovich and Baker 2006; Gut 2007). Considering the centrality of prosody in speech communication, with prosodic modulations subserving linguistic, speaker-specific, emotional, and pragmatic functions (Cole 2015), it is not surprising that

- Prosodic deviations may be even more detrimental to the perceived intelligibility and nativeness of L2 speech than segmental deviations (Derwing and Munro 2005; Jilka 2000; Munro and Derwing 2006; Chun 2013).

- L2 speech typically gains in perceived nativeness and intelligibility when manipulated to align with the prosodic characteristics of L1 speech. For studies on foreign-accented English, see, a.o., Winters and Grantham O’Brien (2013); Ulbrich and Mennen (2015); Rognoni and Busà (2013); Polyanskaya et al. (2017); and Tajima et al. (1997). For research on Swiss German-accented Italian, cf. Pellegrino et al. (2021), and on Polish-accented Dutch, cf. Quené and Van Delft (2010).

Although there is a widespread agreement that deviations in L2 prosody pose a challenge to effective communication, many language learners do not receive sufficient guidance in this area, as there is a limited emphasis on teaching L2 prosody in a classroom context (Lengeris 2012). Especially in foreign language contexts where the teacher is not a native speaker, the focus is often on teaching grammar, vocabulary, and reading and writing skills (Medgyes 2001). When pronunciation is taught, an inverse relationship between communicative importance and teachability has been observed (Wrembel 2007). Formal instruction tends to concentrate on segmentals, which are higher on the learnability scale but less important in communication. On the other hand, prosodic patterns are usually regarded to be more difficult to perceive, produce, and adapt for direct teaching (Dalton and Seidlhofer 1994), as they involve multiple acoustic cues about which teachers and learners may not themselves know enough (Derwing and Munro 2015). The problem does not appear to be fully solved by the integration of research theories and models into classroom teaching, as evidenced by a few moderately successful attempts to implement discourse intonation in second language instruction (Brazil et al. 1980; Bradford 1988; Chapman 2007). Addressing the challenges associated with prosodic training in an L2 may, instead, require the utilization of computer-assisted pronunciation training (CAPT) to enhance the instruction and acquisition of L2 prosody.

In recent decades, the field of CAPT has seen substantial growth, with the emergence of web-based resources and mobile apps, designed to help learners improve their pronunciation (see, a.o., Fouz-González 2015). Such systems are especially relevant in foreign language learning settings, where opportunities for exposure to the target language are limited and non-native-speaking teachers, although proficient in formal aspects of the language, may still retain traces of their native language in their pronunciation (Seferoglu 2005; Neri et al. 2008; Levis 2007). With respect to traditional classroom instruction, CAPT systems go beyond merely addressing the individual segmental aspects of a language. They extend their reach into the realm of suprasegmental elements, including word accent, sentence stress, rhythm, and intonation (see, a.o., Donaldson 2009; Sztahó et al. 2018; Goldman and Schwab 2018).

2.1. Self-Imitation Prosodic Training

Although many CAPT resources appear to be technology-driven rather than pedagogy-led (Rogerson-Revell 2021), studies in the field of voice technology applied to second language learning have informed the design of CAPT systems. While it is undeniable that listening and imitating native speakers can be effective for enhancing pronunciation skills, since the nineteen nineties, several L2 studies have underscored the significance of aligning a student’s voice closely with that of the teacher to enhance prosodic pronunciation skills. In 1990, Nagano and Ozawa introduced a prosodic training approach for Japanese learners of English. This method involved generating synthetic speech stimuli by adjusting the fundamental frequency (F0) and duration characteristics of L2 English speech to match those of L1 English speech. They assessed the effectiveness of this approach in comparison to traditional imitation training. The results revealed that the voice conversion method, which modified the prosody of learners’ speech, was more successful in terms of achieving a higher perceived level of nativeness as rated by native English speakers. Comparable outcomes were observed in subsequent studies involving learners of L2 English, German, and Italian encompassing various language backgrounds (Probst et al. 2002; Bissiri and Pfitzinger 2009; Kusz 2022; De Meo et al. 2012, 2016; Vitale and De Meo 2020). Probst et al. (2002) showed a positive impact of a close match between learners’ voices and those of native speakers for pronunciation enhancement. When L2 English learners imitated a native speaker whose articulation rate and F0 closely matched their own, their accuracy was notably better compared to those imitating a less compatible match. These findings raised the concept of a user-dependent “golden speaker,” suggesting that the most optimal model for learners is their own voice with native-like prosody (Felps et al. 2009). In their study on teaching Italian speakers how to correctly pronounce lexical stress in German compound words, Bissiri and Pfitzinger (2009) demonstrated that feedback given in the learner’s own voice, adjusted to align with the local speech rate, intonation, and intensity of a reference German speaker, was more successful than receiving feedback in the voice of the native German speaker. Kusz (2022) compared the impact of traditional imitation tasks with self-imitation practices on the improvement of English pronunciation among Polish students. The study specifically examined how these two approaches affected the variation in articulation and speech rate, and average syllable duration between pre- and post-training production. The research findings demonstrated a major effect of self-imitation training on pronunciation improvements, especially for speech rate, thus providing further support for the claim that the more closely learners’ voices match their modified counterparts, the more positively it impacts their L2 performance.

Applying these findings to teaching practice, it becomes evident that self-imitation is an effective method for prosodic improvements in the second language. Learners should imitate their own voices while producing utterances with native prosody. The process of converting a foreign accent to a native-like one would also help students better recognize the differences between their accented speech and their ideal native counterparts (Felps et al. 2009). Thus, they receive valuable feedback, which is often missing in computer-assisted pronunciation training (CAPT) (Hismanoglu 2011). A major step towards the implementation of self-imitation as pronunciation training was made by Ding et al. (2019). They designed the Golden Speaker Builder (GSB), a tool that “allows learners to generate a personalized golden-speaker voice: one that mirrors their own voice but with a native accent” (Ding et al. 2019, p. 51). They showed that after three weeks of practicing with GSB, the performance of Korean learners of English gained in perceived fluency and comprehensibility as rated by native English speakers.

The significance of self-imitation prosodic training for pronunciation improvement becomes even clearer when considering the impact of social dynamics and identity on the degree of convergence1 between speakers of the same or different linguistic varieties. Research has demonstrated that social preferences or positive attitudes towards individuals from a specific dialectal region promote acoustic convergence (as observed in Babel 2010, 2012). This phenomenon is also applicable in an L2 setting, where one’s attitude towards native speakers, as well as the perceived attitude of native speakers towards the ethnic group of the interlocutor, was shown to affect the extent of pronunciation adjustments towards the native speakers. For instance, Giles and Johnson (1987) uncovered that L2 speakers are more inclined to mimic the speech patterns of native speakers when belonging to the same social group. In contrast, Zuengler (1982) found that when L2 speakers perceive negative attitudes or threats directed towards their ethnic group, they may choose to diverge phonetically from the L1 speakers. Given the considerable role that language, identity, and social dynamics play in determining the level of phonetic convergence between L1 and L2 speakers, self-imitation prosodic training may eliminate the potential biases related to language and accent, making it an effective method for enhancing pronunciation and prosody in a second language.

When considering factors that may potentially affect the effectiveness of self-imitation on prosodic convergence, one cannot disregard the role of the acoustic distance between the learner and the model prior to the training. While some studies offered evidence suggesting that a minimal distance between the phonetic repertoires of speakers is conducive to convergence (Kim et al. 2011; Babel 2012), other findings suggested that the baseline acoustic distance between the speakers is among the factors driving convergence. In research comparing dialectal varieties (Babel 2010, 2012; Walker and Campbell-Kibler 2015; Ross et al. 2021; Lin et al. 2021), for example, it has been found that cross-dialectal distinctive features tend to trigger more convergence than neutral dialectal features. Translating these findings into an L2 training context, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the degree to which self-imitation aids in acquiring L2 prosody varies depending on the baseline distance between the learners’ and the model’s pronunciation before any training takes place. When the baseline distance is large, there is more potential for improvement through self-imitation, while a small baseline distance may lead to divergence or maintenance.

2.2. Self-Imitation Prosodic Training in L2 Italian

The impact of self-imitation prosodic training as a tool for teaching L2 Italian prosody in relation to various speech acts (i.e., orders, requests, granting, and threatening) was tested on intermediate and elementary Chinese learners (De Meo et al. 2012, 2016; Vitale and De Meo 2020) and upper-intermediate Japanese learners (Pellegrino and Vigliano 2015; Vigliano et al. 2016). The training protocol typically included two sessions: In the initial recording session, the learners were instructed to produce the intended speech acts without explicit instructions. In the second session, the learners were instructed to replicate utterances in their own voices with native-like prosody (self-imitation training) and to imitate the utterances produced by a native speaker (imitation training). The items used for the self-imitation training were obtained by transferring prosodic features (e.g., duration and F0) from L1 speakers’ utterances to the L2 ones through the prosodic transplantation technique (Moulines and Charpentier 1990; Yoon 2007). In De Meo et al. (2012), the effectiveness of both self-imitation and imitation prosodic training were compared, considering several factors such as the degree of improvement in accurately identifying speech acts, communicative effectiveness, intelligibility, and foreign accent reduction. Except for intelligibility, where no significant differences in improvement were observed between the two techniques, intermediate Chinese learners who were trained to replicate utterances in their own voices with native-like prosody yielded a significantly higher improvement in speech act identification and communicative effectiveness than those who imitated utterances from a reference Italian speaker. The difference was especially evident for the requests (De Meo et al. 2012). Remarkably, in terms of accentedness, both imitation and post-self-imitation productions gained in nativeness. In both cases, the strength of the accent decreased from strong to mild, but only some of the post-self-imitation productions were rated as having a native accent.

The greater effect of self-imitation over imitation did not replicate when the study was conducted with elementary learners of Chinese (De Meo et al. 2016). Both teaching strategies promoted a general improvement in learners’ performances, but results varied depending on the communicative function and the length of the utterance. Without the availability of statistical analysis, which would have provided a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between training, speech acts, and the length of utterances, it was not possible to draw a more generalizable conclusion on the greater effectiveness of one strategy over the other for elementary learners.

2.2.1. Previous Research on Japanese Learners of Italian

The acoustic analyses of prosodic convergence conducted in the present study were, instead, based on research involving Japanese speakers learning Italian in a foreign language learning context (Pellegrino and Vigliano 2015; Vigliano et al. 2016) (cf. par. 3.1. Speakers). The specific combination of languages, i.e., L1 Italian and L2 Italian spoken by Japanese learners, was chosen as Italian and Japanese exhibit notable differences in various phonetic aspects, including how they convey pragmatic meanings in speech. In Italian, where there is a lack of morphological and syntactical tools for distinguishing sentence modality, intonation plays a pivotal role in shaping the pragmatic meaning of an utterance (D’Imperio 2002). Conversely, in Japanese, a wide range of syntactical, lexical, and prosodic devices are employed to convey various pragmatic meanings within an utterance (Abe 1998). Given this substantial cross-linguistic disparity, we anticipated that this task would pose a challenge for our group of learners. Consequently, we hypothesized that a tailored training approach, proven to be more effective than traditional imitation for learners (Nagano and Ozawa 1990; Bissiri and Pfitzinger 2009; Ding et al. 2019; De Meo et al. 2012; Vitale and De Meo 2020), would be instrumental in achieving effective communication. The same protocol for self-imitation training applied to Chinese students was replicated with the group of Japanese learners (cf. par. 3.2. Speech material). For this study, the speech acts under examination were commands, requests, and granting. In line with the findings of De Meo et al. (2012), the results of perceptual evaluation by native speakers indicated a significant increase in the percentage of correctly matched intended and perceived pragmatic functions after the training, shifting from 33.61% in the pre-training phase to 60.04% in the post-training phase. This effect was particularly notable for the act of granting, where the percentage of correct identification increased from 8.4% in the pre-training phase to 47.06% in the post-training phase. Additionally, for requests, the percentage increased from 52.52% to 75.21% and, for commands, from 39.92% to 57.98%.

Vigliano et al. (2016) conducted acoustic analyses with the goal of comparing the distance between L2 productions before and after the training in relation to the corresponding utterances produced by native speakers who served as the model for the training. We examined various features, including the duration of utterances as well as the durations of vocalic and consonant intervals. Initial descriptive findings indicated that, on average, the duration of L2 utterances and their vocalic segments became closer to the duration of L1 utterances after the training. To put it differently, there was an overall increase in the duration of utterances after the training. This increase was primarily due to an elongation of consonantal intervals, as the vocalic segments became shorter following the training. Like the results of the perception test, the effect of training on approximating the L1 acoustic behavior was especially evident for the act of granting.

3. The Present Study

In the present study, we aimed at further quantifying the degree of prosodic convergence towards the L1 Italian speakers used as a model for self-imitation training. We expanded upon the previous research by Vigliano et al. (2016) by conducting a more detailed examination of convergence in duration, F0 mean, and F0 max syllable-wise. We based our analysis on duration and F0 as (1) they were the parameters manipulated using the prosodic transplantation technique; (2) they are also among the prosodic features commonly employed for automatic speech act classification, as outlined in prior research in English (Hoque et al. 2007). Moreover, we took F0 mean and F0 max as indicators of F0 in the endeavor to capture the alterations in F0 associated with pitch accents and the shape of the final sentence contour.

Drawing upon the perceptual findings that underscored a general rise in the percentage of accurately matched intended and perceived pragmatic functions after the training (De Meo et al. 2012; Pellegrino and Vigliano 2015; Vigliano et al. 2016), we hypothesized that learners converge prosodically towards the L1 speakers used as the model for the self-imitation training. In other words, we expected to observe that the acoustic distance between the learners and the model would decrease after the training (Hypothesis 1).

Based on acoustic and perceptual findings that have underscored the most significant impact of the training on the act of granting (Pellegrino and Vigliano 2015; Vigliano et al. 2016), both in terms of the alignment between perceived and intended pragmatic functions and the duration of vocalic intervals, we anticipate that the most pronounced acoustic similarity to the native speaker model will be observed in the context of the act of granting (Hypothesis 2). We also tentatively hypothesize that the effect of training may vary depending on the position of the syllable in the sentence (sentence-initial vs. sentence-final position) and on the presence of a pitch accent.

Considering the insights from studies on phonetic convergence, which have revealed that greater initial differences between the shadowers and model talkers tend to promote convergence (Babel 2010; Walker and Campbell-Kibler 2015; Ross et al. 2021; Lin et al. 2021), we expect that the effectiveness of self-imitation in fostering prosodic convergence would hinge on the extent to which the learners’ pre-training acoustic patterns differed from those of the L1 speakers employed as models for the training (Hypothesis 3).

3.1. Participants

L2 Italian speakers: We recruited seven upper intermediate L1 Japanese learners of Italian (two males and five females), from Tokyo University in Japan, aged between 21 and 28. Before the experiment, they had studied Italian for five or six years in their home country, with the additional experience of studying the Italian language and linguistics in Italy for one year.

L1 Italian speakers: We recruited two native Italian speakers (one male and one female), aged 27 and 25, respectively. At the time when the research was conducted, they had been living in Japan for a period of six months.

Both L1 and L2 Italian speakers declared not to have any speech, language, or hearing impairment. All gave their informed consent to participate in the study.

3.2. Speech Material

The corpus for the current study was collected and manipulated according to the protocol described in Pellegrino and Vigliano (2015) and Vigliano et al. (2016). Here, we summarize the main steps:

Pre-training corpus

L1 and L2 Italian speakers were instructed to record two sentences in Italian, modulating their prosody to convey three distinct speech acts: command, request, and granting2.

Sentence 1: Accendi la radio.

- -

- (Request) Accendi la radio?/eng. Can you turn on the radio?

- -

- Command) Accendi la radio!/eng. Turn on the radio!

- -

- (Granting) Accendi la radio./eng. Ok, you can turn on the radio.

Sentence 2: Chiudi la finestra.

- -

- (Request) Chiudi la finestra?/eng. Can you close the window?

- -

- (Command) Chiudi la finestra!/eng. Close the window!

- -

- (Granting) Chiudi la finestra./eng. Ok, you can close the window.

Given the above-mentioned differences between Italian and Japanese in conveying pragmatic functions (D’Imperio 2002; Abe 1998), the sentences and their intended pragmatic meanings were also translated into Japanese by a Japanese linguist specialized in the Italian language to ensure the full comprehension of the task. During the pre-training phase, learners were instructed to utter the intended speech acts without receiving explicit instructions. They could repeat the utterances as many times as they needed, and when they felt confident, their performance was recorded. The native Italian speakers undertook the same task. The recordings were taken in single sessions, in a silent room at Tokyo University, at a 44.100 Hz sampling rate.

The collected speech corpus in the pre-training session consisted of

- A total of 42 utterances in L2 Italian (7 L2 speakers * 2 sentences * 3 communicative intentions) (henceforth pre-training corpus);

- A total of 12 utterances in L1 Italian (2 L1 speakers * 2 sentences * 3 communicative intentions) (henceforth L1 Italian corpus).

Self-imitation prosodic training and the post-training corpus

As mentioned above, an essential step of self-imitation prosodic training is the implementation of prosodic transplantation (Yoon 2007). Through this process, the L2 learners’ utterances (henceforth receivers’ utterances) were manipulated to match the duration and F0 characteristics of the corresponding utterances produced by the native speakers (henceforth donors’ utterances). To transfer the selected acoustic parameters from the donors’ to the receivers’ utterances, several steps were conducted:

- The donors’ and receivers’ utterances were manually segmented into consonantal and vocalic portions in Praat textgrids.

- Duration and pitch contour were transferred from donors’ to receivers’ utterances interval-wise by means of a Praat script automatizing the prosodic transplantation.

For the transplantation process, a matching criterion based on gender was followed, ensuring that the voices of the male and female donors would be paired with the voices of male and female receivers, respectively.

Following these manipulations, a new corpus of 42 synthesized receivers’ utterances was created. These newly generated utterances were used as stimuli for self-imitation prosodic training, during which the L2 learners imitated their own utterances with the prosody of the L1 speaker. The training was self-paced, and participants recorded the new performances when they felt confident. The average duration of the training session, including the recording of the post-training corpus, ranged from 20 to 30 min. As a result of the self-imitation prosodic training, a post-training corpus was collected that consisted of 14 requests, 14 commands, and 14 grantings.

3.3. Acoustic and Statistical Analyses

Acoustic Analyses: To measure the convergence of the L2 speakers towards the L1 speakers after the training, we followed the following steps:

- Step 1: We manually segmented and labeled in syllables the utterances of the L1 speakers and those of the L2 learners in the pre- and post-training corpora using Praat textgrids.

- Step 2: For each syllable of the L1 corpus, pre- and post-training corpora, we automatically extracted duration, F0 mean, and F0 max. The measurements were extracted from a total number of 576 syllables, of which 504 were in L2 Italian ((6 syllables * 2 utterances * 3 speech acts * 2 recording sessions (pre- and post-training) * 7 speakers) and 72 were in L1 Italian (6 syllables * 2 utterances * 3 speech acts * 2 speakers).

- Step 3: For each syllable in every corpus, we normalized the syllable duration, F0 max, and F0 mean using z-score transformation (z = (x − μ)/σ), computed per speaker, sentence, and speech act.

- Step 4: We calculated the absolute difference in duration, F0 mean, and F0 max between the syllables in the L1 Italian corpus and the corresponding syllables in the pre- and post-training corpora (henceforth Mod-Pre and Mod-Post). In the calculation of the distance between the L1 and L2 productions, we adhered to the gender-matching criterion applied in prosodic transplantation and self-imitation training. Hence, in the computation of Mod-Pre and Mod-Post, we matched the syllables of the female L1 speaker with those produced by the female L2 learners and, likewise, the syllables of the male L1 speaker with those of the male L2 learners.

Statistical Analyses: Statistical analyses were performed with R Studio (R Core Team 2023). To test hypothesis 1, i.e., L2 speakers converge prosodically towards the native model after self-imitation training, we tested the effect of the training session (before and after the training) on the distance to the model in terms of duration, F0 mean, and F0 max by using a linear mixed model including the L2 learners and the syllables as random intercepts.

To test hypothesis 2, i.e., the training exerts a different effect on the degree of approximation towards the L1 model depending on speech acts, we tested the interaction between the training session (before and after the training) and speech acts (command, grant, and request) on the distance to the model in terms of duration, F0 mean, and F0 max by using a linear mixed model. L2 learners and the syllables were entered into the model as random effects. In the presence of a significant interaction, we ran the post hoc comparisons with the Tukey method for multiple comparison tests. To understand if the training exerted a more noticeable impact in terms of duration and F0 adjustments on specific syllables of the utterances (e.g., stressed, unstressed, sentence-initial, and sentence-final position), we conducted a preliminary descriptive comparison of the differences in syllable duration, F0 max, and F0 mean between the pre-training and post-training phases on a syllable-by-syllable basis.

To test hypothesis 3, i.e., the baseline distance between pre-training and L1 productions influences the amount of convergence, we ran a correlation analysis. This analysis involved:

- Mod-Pre (i.e., the acoustic distance between the model and the pre-training productions syllable by syllable).

- Degree of convergence, quantified as the difference in the distance (henceforth DID) between Mod-Post (i.e., the acoustic distance between the model and the post-training productions syllable-wise) and Mod-Pre. Negative DID values indicate that Mod-Post is lower than Mod-Pre, providing evidence of convergence. Conversely, positive DID values signify that Mod-Post is higher than Mod-Pre, suggesting divergence. DID values centered around zero indicate maintenance.

4. Results

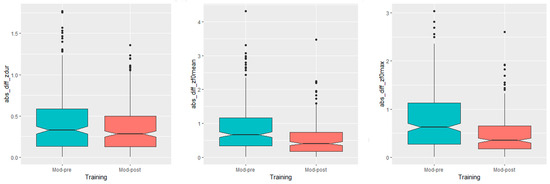

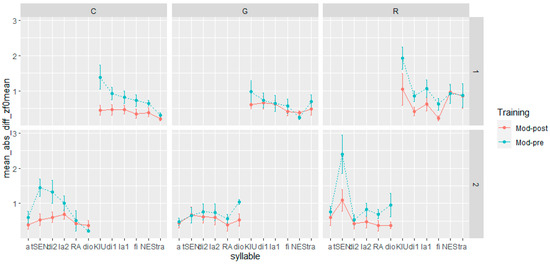

With respect to the first hypothesis, i.e., learners converge prosodically towards the native speakers after the training, the data in Figure 1 left, center and right display that the difference towards the native model was lower in post-training (Mod-post) than in pre-training (Mod-pre) productions for all examined acoustic parameters. This trend is confirmed by the statistical analysis, which showed a significant main effect of training session on the absolute difference in duration (F(1) = 8.4075, p = 0.003905), F0 mean, (F(1) = 36.984, p < 0.001), and F0 max (F(1) = 51.35, p < 0.001) between the learners and the model.

Figure 1.

Acoustic distance between the model and the learners before and after the training for syllable duration (left), F0 mean (center), and F0 max (right).

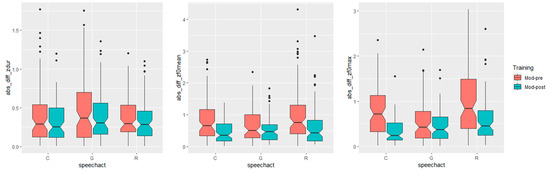

With respect to our second hypothesis, i.e., the effect of the training varies according to the speech act, with “granting” showing the most noticeable approximation towards the L1 speaker, Figure 2 left, center, and right illustrate that the absolute distance between the learners and model decreased in post-training productions (Mod-Post), with appreciable differences between speech acts and measures. From a visual inspection of the data, indeed, it appears that for duration (Figure 2 left), the differences between pre- and post-training look marginal for all speech acts, whereas for both F0 measures (Figure 2 center and right), the effect seems larger for the request and command but smaller for granting.

Figure 2.

Acoustic distance between the model and the learners before and after the training by speech act (C = command; G = granting; and R = request) for syllable duration (left), F0 mean (center), and F0 max (right).

The results of statistical analysis on the interaction between training and speech acts confirmed these observations. The interaction, indeed, was significant on every distance measure (duration: F(5) = 4.5782, p < 0.001; F0 mean: F(5) = 12.03, p < 0.001; F0 max: F(5): 19.725, p < 0.001), but post hoc comparisons with Tukey corrections revealed that

- For duration, the distance to the model from pre- to post-training productions did not change significantly for any speech act (Table 1).

Table 1. Post hoc comparisons with Tukey corrections for the distance to the model in pre- and post-training productions for duration (C = command, G = granting, and R = request). The full set of comparisons is available in Appendix A, Table A1.

Table 1. Post hoc comparisons with Tukey corrections for the distance to the model in pre- and post-training productions for duration (C = command, G = granting, and R = request). The full set of comparisons is available in Appendix A, Table A1. - For F0 mean and F0 max, the distance to the model from pre- to post-training productions was significantly different for command and request but not for granting (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2. Post hoc comparisons with Tukey corrections for the distance to model in pre- and post-training productions for F0 mean (C= command, G = granting, and R = request). The full set of comparisons is available in Appendix A, Table A2.

Table 2. Post hoc comparisons with Tukey corrections for the distance to model in pre- and post-training productions for F0 mean (C= command, G = granting, and R = request). The full set of comparisons is available in Appendix A, Table A2. Table 3. Post hoc comparisons with Tukey corrections for the distance to model in pre- and post-training productions for F0 max (C= command, G = granting, and R = request). The full set of comparisons is available in Appendix A, Table A3.

Table 3. Post hoc comparisons with Tukey corrections for the distance to model in pre- and post-training productions for F0 max (C= command, G = granting, and R = request). The full set of comparisons is available in Appendix A, Table A3.

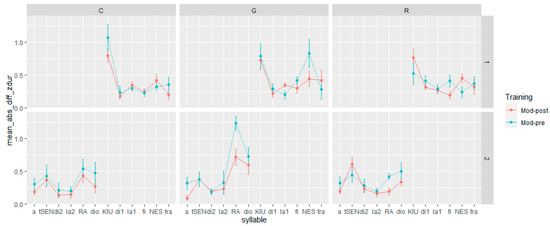

In relation to the impact of the training in terms of duration and F0 adjustments on specific syllables of the utterances (stressed, unstressed, sentence-initial, and sentence-final position), the results vary depending on the acoustic feature and speech act. Regarding duration (Figure 3), a noteworthy observation is that the training had its most significant impact on the final lexically stressed syllable within two sentences when they are realized as “granting” (RA:; NEST) (Figure 1, central panels). In the post-training realization of the syllables “RA” and “NEST,” indeed, there was a remarkable reduction in their distance from the model in comparison to their respective pre-training realizations. In contrast, the difference was less evident for the other syllables between pre-training and post-training realizations.

Figure 3.

Distance in syllable duration between pre- and post-training production from the model by utterance, syllables, and speech act. The dots represent the mean, and the error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

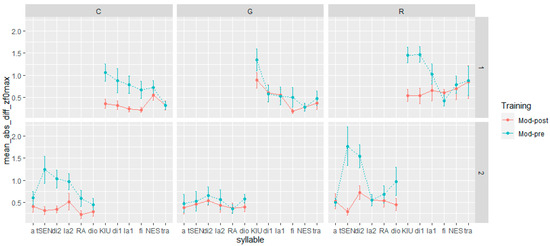

When considering F0 max and mean (Figure 4 and Figure 5), the influence of the training is more evident for the speech acts involving commands and requests. Both speech acts showed the closest approximation to the native model in post-training production, especially in sentence-initial lexically stressed syllables (tS:En; KJU:), which both native speakers produced with a rising pitch accent (L + H*). However, there are distinctions between commands and requests in terms of the differences observed in pre- and post-training production for nuclear and post-nuclear syllables (s1 = NES, tra; s2 = RA, dio). In commands, the training’s impact was minimal, as both pre- and post-training production closely resembled the realizations of native speakers to a similar degree. On the other hand, for requests, the effect appears to vary between sentences. In the first sentence, the difference in F0 max and mean between pre- and post-training recordings was negligible. In the second sentence, however, the post-training realizations of both nuclear and post-nuclear syllables were closer to those of native speakers than the pre-training versions.

Figure 4.

Distance in F0 max between pre- and post-training production from the model by utterance, syllables, and speech act. The dots represent the mean, and the error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Figure 5.

Distance in F0 mean between pre- and post-training production from the model by utterance, syllables, and speech act. The dots represent the mean, and the error bars represent the standard error of the mean.

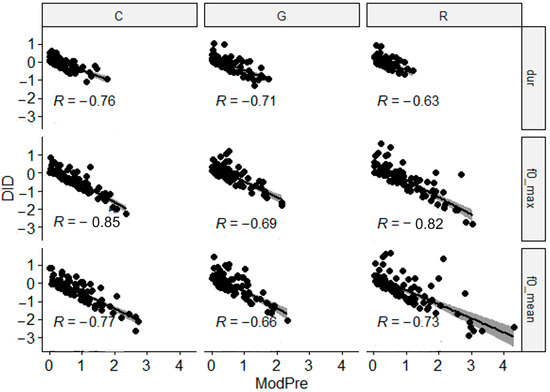

Regarding the third hypothesis, i.e., the baseline acoustic distance between the learners and the model influences the amount of convergence towards the native speaker, the results depicted in Figure 6 show a significant moderate negative correlation between the baseline distance (Mod-Pre) and the amount of convergence after the training (DID). In other words, the larger the baseline acoustic distance between the model and the learners, the greater the convergence in post-training production, as evidenced by negative DID scores.

Figure 6.

Correlation between pre-training distance to the model (ModPre) and degree of convergence towards the native model measured in DID. The p value of all correlations is 2.2 × 10−16.

5. Discussion

The current study investigated the effect of self-imitation prosodic training on the prosodic convergence of Japanese learners of Italian towards the L1 speakers used as a model for the training. We operationalized convergence in terms of the acoustic distance between the model and learners’ pre- and post-training productions in terms of syllable duration, F0 mean, and F0 max.

The overall results showed significant convergence towards the acoustic profile of the L1 speakers following self-imitation training. This convergence was not only evident in past perceptual evaluations conducted by native Italian speakers, which revealed a heightened alignment between the intended and perceived pragmatic function in post-training production (Pellegrino and Vigliano 2015; Vigliano et al. 2016), but it was also reflected in the reduction in the overall acoustic distance between the L2 learners and the L1 speakers across all examined acoustic measures. However, upon closer examination of the model-to-learner distance with respect to different speech acts and measurements, the training did not exhibit the expected strongest influence on the act of granting. Surprisingly, it was the acts of request and command for which L2 learners demonstrated the greatest proximity to the L1 speaker after the training. This finding is in line with a previous perceptual evaluation of Chinese learners (De Meo et al. 2012) but is in contrast with the prior perceptual and acoustic investigations of L2 Italian Japanese (Pellegrino and Vigliano 2015; Vigliano et al. 2016), which served as the basis for our initial hypothesis about the interaction between speech act and training. Specifically, at the perceptual level, our previous research on Japanese learners demonstrated that the act of granting exhibited the most substantial improvement in correct matches after the training followed by requests and orders (Pellegrino and Vigliano 2015). At the acoustic level, the preliminary comparisons of the acoustic distance between the L1 speakers and the L2 speakers before and after the training in terms of average utterance duration and duration of vocalic intervals revealed that the act of granting yielded the greatest convergence (Vigliano et al. 2016). The underlying reasons for this discrepancy are not yet fully understood and will be the focus of future investigations. In an attempt to interpret this finding, we present two alternative explanations. Regarding the divergence between perceptual and acoustic evaluations, it is worth mentioning that such disparities are not uncommon in the realm of vocal accommodation. In fact, numerous studies have reported that acoustic and perceptual assessments of convergence do not always align precisely (see, a.o., Pardo 2006; Pardo et al. 2013). This is because listeners tend to consider multiple acoustic–phonetic dimensions at the same time when assessing the overall similarity of speech excerpts. These may not necessarily correspond to the specific set of examined acoustic attributes. Consequently, it is plausible that the acoustic features investigated in this study do not precisely correspond with the criteria used by Italian listeners to identify the pragmatic function of the utterances presented in the perception test. Alternatively, listeners may have selectively focused on specific portions of the utterances (e.g., sentence-final and sentence-initial positions) to identify the speech act. In the case of “granting,” the enhanced alignment between the intended and perceived function of the “granting” in post-training production could be potentially attributed to the elongation of the final lexically stressed syllables. This elongation may have been perceived as more prominent compared to other aspects when identifying utterances as granting. Given the vital role of prosodic cues in guiding listeners to discern the speaker’s intentions (Gilbert 2014), the interplay between acoustic and perceptual assessments of prosodic convergence following self-imitation training represents an intriguing avenue for future investigations.

Several methodological reasons may account, instead, for the discrepancy between the current acoustic analyses and those in Vigliano et al. (2016). In the earlier study, the distance between native speakers’ productions and those of the learners before and after the training relied on averaging values from all learners’ productions in each respective training phase (before and after training). Moreover, this approach lacked descriptive measurements of variance or any statistical outcomes regarding the significance of the interaction between speech acts and training. Consequently, it is unclear whether the differences were statistically significant and whether the values might have been influenced by extreme forms of convergence exhibited by certain learners. In contrast, for the analysis of the present study, we adopted a more rigorous methodology. For every recording phase (before and after the self-imitation training), we calculated the distance between individual learners and the model on a syllable-by-syllable basis, incorporating both learners and syllables as random intercepts in the model. Although this approach resulted in a non-significant difference between the model and the learners’ pre- and post-training productions for the speech act of granting, we ensured a more robust and statistically rigorous assessment of convergence. A subsequent phase of this research will involve expanding the acoustic analysis to encompass additional suprasegmental parameters possibly affected by the prosodic transplantation (e.g., F0 range, rate, and timing properties of consonantal and vocalic intervals) as well as segmental parameters. This last level of analysis will help us gain insight into whether the impact of prosodic training can also lead to enhancements in the pronunciation of Italian segments, as has been evidenced for other languages and non-native accents (for Italian learners of German, cf. Dahmen et al. 2023; for Catalan learners of French, cf. Li et al. 2023).

Yet, another significant finding of this study is the influence of the baseline distance between the L2 learners and the L1 speakers on the degree of convergence, which was measured using the difference in distance approach. Across all speech acts and acoustic measures, it became evident that a larger initial distance led to a more substantial level of convergence. This finding was expected and corroborated the documented effect of the acoustic distance on convergence observed in vocal accommodation research (Babel 2010 2012; Walker and Campbell-Kibler 2015; Ross et al. 2021; Lin et al. 2021). By demonstrating that a larger initial acoustic distance between the speaker and the model leads to greater convergence, this study suggests that the self-imitation is a technique for improving L2 prosody, especially in a context where exposure to native speakers is limited and there is an increased risk of miscommunication due to differences in prosody.

Limitations and future research: While the primary objective of the paper is to examine prosodic convergence after self-imitation training, an important limitation in interpreting the study’s results arises from the absence of a control group that imitated native L1 speakers, enabling a comparison with the group that underwent self-imitation training. Additional research on the comparison between imitation and self-imitation through available interactive training tools, like, for example, the Golden Speaker (Ding et al. 2019), is needed to gain a more comprehensive understanding of whether the benefits associated with self-imitation in training are significant enough, in comparison to conventional imitation, to justify the procedural complexities and artifacts inherent in the self-imitation process.

Further research is also essential to explore the extent to which learners can effectively apply the prosodic patterns they have acquired to sentences and phrases that were not part of their training curriculum. While the present experiment centered on instructing learners to generate utterances with the intention of conveying speech acts, it did not offer specific contextual elements. Future studies should endeavor to create more ecologically valid situations (e.g., conversations and task-based dialogue situations) to scrutinize language usage in more realistic settings.

In order to attain a more linguistically focused interpretation of the data, which is only minimally considered in this paper, it is crucial to conduct a more comprehensive analysis of the prosodic–pragmatic relationship in the speech act realization. This should involve, for example, identifying how pitch accents or the intonation contour in the sentence-final position are realized within both the native language (L1) and the second language (L2) contexts, both prior to and following the training.

Funding

This research has been partially funded by “NCCR Evolving Language, Swiss National Science Foundation Agreement #51NF40_180888.”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study since exclusively behavioral data were acquired.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Debora Vigliano and Massimo Pettorino for their contribution to the realization of the preparatory steps for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Post hoc comparisons with Tukey corrections for the distance to model in terms of duration.

Table A1.

Post hoc comparisons with Tukey corrections for the distance to model in terms of duration.

| Contrast—Distance in Duration | Estimate | SE | df | t.Ratio | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mod-postC)-(Mod-preC) | −0.07873 | 0.0433 | 493 | −1.82 | 0.454 |

| (Mod-postC)-(Mod-postG) | −0.07807 | 0.0433 | 493 | −1.805 | 0.464 |

| (Mod-postC)-(Mod-preG) | −0.18938 | 0.0433 | 493 | −4.378 | <0.001 |

| (Mod-postC)-(Mod-postR) | −0.02797 | 0.0433 | 493 | −0.646 | 0.987 |

| (Mod-postC)-(Mod-preR) | −0.05722 | 0.0433 | 493 | −1.323 | 0.772 |

| (Mod-preC)-(Mod-postG) | 0.000657 | 0.0433 | 493 | 0.015 | 1.000 |

| (Mod-preC)-(Mod-preG) | −0.11066 | 0.0433 | 493 | −2.558 | 0.110 |

| (Mod-preC)-(Mod-postR) | 0.050758 | 0.0433 | 493 | 1.173 | 0.850 |

| (Mod-preC)-(Mod-preR) | 0.021506 | 0.0433 | 493 | 0.497 | 0.996 |

| (Mod-postG)-(Mod-preG) | −0.11132 | 0.0433 | 493 | −2.573 | 0.106 |

| (Mod-postG)-(Mod-postR) | 0.050101 | 0.0433 | 493 | 1.158 | 0.856 |

| (Mod-postG)-(Mod-preR) | 0.020849 | 0.0433 | 493 | 0.482 | 0.997 |

| (Mod-preG)-(Mod-postR) | 0.161416 | 0.0433 | 493 | 3.731 | 0.003 |

| (Mod-preG)-(Mod-preR) | 0.132164 | 0.0433 | 493 | 3.055 | 0.029 |

| (Mod-postR)-(Mod-preR) | −0.02925 | 0.0433 | 493 | −0.676 | 0.984 |

Table A2.

Post hoc comparisons with Tukey corrections for the distance to model in terms of F0 mean.

Table A2.

Post hoc comparisons with Tukey corrections for the distance to model in terms of F0 mean.

| Contrast—Distance in F0 Mean | Estimate | SE | df | t.Ratio | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mod-postC)-(Mod-preC) | −0.3819 | 0.0873 | 493 | −4.375 | 0.0002 |

| (Mod-postC)-(Mod-postG) | −0.089 | 0.0873 | 493 | −1.02 | 0.9112 |

| (Mod-postC)-(Mod-preG) | −0.2287 | 0.0873 | 493 | −2.62 | 0.0943 |

| (Mod-postC)-(Mod-postR) | −0.1764 | 0.0873 | 493 | −2.021 | 0.3315 |

| (Mod-postC)-(Mod-preR) | −0.5896 | 0.0873 | 493 | −6.756 | <0.0001 |

| (Mod-preC)-(Mod-postG) | 0.2929 | 0.0873 | 493 | 3.355 | 0.011 |

| (Mod-preC)-(Mod-preG) | 0.1532 | 0.0873 | 493 | 1.755 | 0.496 |

| (Mod-preC)-(Mod-postR) | 0.2054 | 0.0873 | 493 | 2.353 | 0.175 |

| (Mod-preC)-(Mod-preR) | −0.2077 | 0.0873 | 493 | −2.38 | 0.1652 |

| (Mod-postG)-(Mod-preG) | −0.1397 | 0.0873 | 493 | −1.6 | 0.5987 |

| (Mod-postG)-(Mod-postR) | −0.0874 | 0.0873 | 493 | −1.002 | 0.9173 |

| (Mod-postG)-(Mod-preR) | −0.5006 | 0.0873 | 493 | −5.736 | <0.0001 |

| (Mod-preG)-(Mod-postR) | 0.0523 | 0.0873 | 493 | 0.599 | 0.9911 |

| (Mod-preG)-(Mod-preR) | −0.3609 | 0.0873 | 493 | −4.135 | 0.0006 |

| (Mod-postR)-(Mod-preR) | −0.4132 | 0.0873 | 493 | −4.733 | <0.0001 |

Table A3.

Post hoc comparisons with Tukey corrections for the distance to model in terms of F0 max.

Table A3.

Post hoc comparisons with Tukey corrections for the distance to model in terms of F0 max.

| Contrast—Distance in F0 Max | Estimate | SE | df | t.Ratio | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mod-post C)-(Mod-pre C) | −0.43251 | 0.0759 | 493 | −5.701 | <0.0001 |

| (Mod-post C)-(Mod-post G) | −0.11198 | 0.0759 | 493 | −1.476 | 0.6799 |

| (Mod-post C)-(Mod-pre G) | −0.22987 | 0.0759 | 493 | −3.03 | 0.0307 |

| (Mod-post C)-(Mod-post R) | −0.23658 | 0.0759 | 493 | −3.118 | 0.0235 |

| (Mod-post C)-(Mod-pre R) | −0.6631 | 0.0759 | 493 | −8.74 | <0.0001 |

| (Mod-pre C)-(Mod-post G) | 0.32053 | 0.0759 | 493 | 4.225 | 0.0004 |

| (Mod-pre C)-(Mod-pre G) | 0.20264 | 0.0759 | 493 | 2.671 | 0.083 |

| (Mod-pre C)-(Mod-post R) | 0.19592 | 0.0759 | 493 | 2.582 | 0.1036 |

| (Mod-pre C)-(Mod-pre R) | −0.2306 | 0.0759 | 493 | −3.039 | 0.0299 |

| (Mod-post G)-(Mod-pre G) | −0.11789 | 0.0759 | 493 | −1.554 | 0.6294 |

| (Mod-post G)-(Mod-post R) | −0.12461 | 0.0759 | 493 | −1.642 | 0.5708 |

| (Mod-post G)-(Mod-pre R) | −0.55113 | 0.0759 | 493 | −7.264 | <0.0001 |

| (Mod-pre G)-(Mod-post R) | −0.00672 | 0.0759 | 493 | −0.089 | 1 |

| (Mod-pre G)-(Mod-pre R) | −0.43324 | 0.0759 | 493 | −5.71 | <0.0001 |

| (Mod-post R)-(Mod-pre R) | −0.42652 | 0.0759 | 493 | −5.621 | <0.0001 |

Notes

| 1 | The concept of phonetic convergence typically refers to interspeaker adjustments that occur during interactions or as a result of increased exposure to a conversation partner. Nonetheless, extensive research has explored this phenomenon in non-interactive contexts as well, such as shadowing or imitation tasks. In these scenarios, participants are tasked with replicating words or phrases after hearing them from a model speaker (cf. Pardo et al. 2022; Wynn and Borrie 2022 for recent overviews). Some studies have even compared phonetic convergence between conversational interactions and non-interactive speech shadowing tasks, involving a substantial number of speakers who participated in both types of tasks (Pardo et al. 2018). |

| 2 | As clarified in Pellegrino and Vigliano (2015), the rationale behind the choice of the three speech acts was to integrate directives (requests and commands), which are frequently used in classroom interactions and therefore appear in the early phases of interlanguage development, with the less commonly encountered act of granting. This selection aimed to mirror the natural progression of speech acts in language development, where directives are prominent in the initial stages whereas granting receives less emphasis in advanced-level language courses. |

References

- Abe, Isamu. 1998. Intonation in Japanese. In Intonation Systems—A Survey of Twenty Languages. Edited by Daniel Hirst and Albert Di Cristo. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, pp. 363–78. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-Hsieh, Janet, Johnson Ruth, and Kenneth Koehler. 1992. The relationship between native speaker judgments of nonnative pronunciation and deviance in segmentals, prosody, and syllable structure. Language Learning 42: 529–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babel, Molly. 2010. Dialect divergence and convergence in New Zealand English. Language in Society 39: 437–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babel, Molly. 2012. Evidence for phonetic and social selectivity in spontaneous phonetic imitation. Journal of Phonetics 40: 177–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissiri, Maria Paola, and Hartmut R. Pfitzinger. 2009. Italian speakers learn lexical stress of German morphologically complex words. Speech Communication 51: 933–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, Barbara. 1988. Intonation in Context. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brazil, David, Malcom Coulthard, and Catherine Johns. 1980. Discourse Intonation and Language Teaching. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, Mark. 2007. Theory and practice of teaching discourse intonation. English Language Teaching Journal 61: 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Dorothy M. 2013. Computer-assisted pronunciation teaching. In Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. Edited by Carol A. Chapelle. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 823–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Jennifer. 2015. Prosody in context: A review. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 30: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Imperio, Maria Paola. 2002. Italian intonation: An overview and some questions. Probus 14: 37–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahmen, Silvia, Martine Grice, and Simon Roessig. 2023. Prosodic and Segmental Aspects of Pronunciation Training and Their Effects on L2. Languages 8: 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, Christiane, and Barbara Seidlhofer. 1994. Pronunciation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Meo, Anna, Marilisa Vitale, and Elisa Pellegrino. 2016. Tecnologia della voce e miglioramento della pronuncia in una L2: Imitazione e autoimitazione a confronto. Uno studio su cinesi apprendenti di italiano L2. In Studi AItLA 4. Linguaggio e Apprendimento Linguistico. Metodi e Strumenti Tecnologici. Edited by Francesca Bianchi and Paola Leone. Milano: AItLA, pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- De Meo, Anna, Marilisa Vitale, Massimo Pettorino, Franco Cutugno, and Antonio Origlia. 2012. Imitation/self-imitation in computer-assisted prosody training for Chinese learners of L2 Italian. Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Proceedings 4: 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Derwing, Tracey M., and Murray J. Munro. 2005. Second language accent and pronunciation teaching: A research-based approach. TESOL Quarterly 39: 379–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwing, Tracey M., and Murray J. Munro. 2015. Pronunciation Fundamentals: Evidence-Based Perspectives for L2 Teaching and Research. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Shaojin, Christopher Liberatore, Sinem Sonsaat, Ivana Lučić, Alif Silpachai, Guanlong Zhao, Evgeny Chukharev-Hudilainen, John Levis, and Ricardo Gutierrez-Osuna. 2019. Golden speaker builder—An interactive tool for pronunciation training. Speech Communication 115: 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, Jonan P. 2009. Literature Review: Computer Aided Pronunciation Training. Available online: https://people.wou.edu/~donaldsj/TestWebsitePortfolio2/TestWebsitePortfolio2/portfolioartifacts/ResearchWriting/Jonan%20Donaldson%20ED%20633%20Final%20Literature%20Review.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Felps, Daniel, Heather Bortfeld, and Ricardo Gutierrez-Osuna. 2009. Foreign accent conversion in computer assisted pronunciation training. Speech Communication 51: 920–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flege, James Emil, Ocke-Schwen Bohn, and Sunyoung Jang. 1997. Effects of experience on non-native speakers’ production and perception of English vowels. Journal of Phonetics 25: 437–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouz-González, Jonas. 2015. Trends and directions in computer assisted pronunciation training. In Investigating English Pronunciation: Trends and Directions. Edited by Jose Mompean and Jonas Fouz-González. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 314–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Judy. 2014. Myth 4: Intonation is hard to teach. In Pronunciation Myths: Applying Second Language Research to Classroom Teaching. Edited by Linda Grant. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, pp. 107–36. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Howard, and Patricia Johnson. 1987. Ethnolinguistic Identity Theory: A Social Psychological Approach to Language Maintenance. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 68: 69–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, Jean-Philippe, and Sandra Schwab. 2018. MIAPARLE: Online training for the discrimination of stress contrasts. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018). Miyazaki: European Language Resources Association (ELRA). [Google Scholar]

- Gut, Ulrike. 2007. Foreign Accent. In Speaker Classification I. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 4343. Edited by Christian Müller. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hismanoglu, Murat. 2011. Computer Assisted Pronunciation Teaching: From the Past to the Present with its Limitations and Pedagogical Implications. In Frontiers of Language and Teaching, Proceedings of the 2011 IOLC. Parkland: Universal-Publishers, vol. 2, pp. 193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Hoque, Mohammed E., Mohammad S. Sorower, Mohammed Yeasin, and Max M. Louwerse. 2007. What Speech Tells Us About Discourse: The Role of Prosodic and Discourse Features in Speech Act Classification. Paper presented at the 2007 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, Orlando, FL, USA, August 12–17; pp. 2999–3004. [Google Scholar]

- Jilka, Matthias. 2000. The contribution of intonation to the perception of foreign accent: Identifying intonational deviations by means of F0 generation and resynthesis. In Arbeitspapiere des Instituts für Maschinelle Sprachchverarbeitung [Working Papers of the Institute for Machine Language Processing]. Stuttgart: Universität Stuttgart, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Okim. 2010. Relative salience of suprasegmental features on judgments of L2 comprehensibility and accentedness. System 38: 301–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Midam, William S. Horton, and Ann R. Bradlow. 2011. Phonetic convergence in spontaneous conversations as a function of interlocutor language distance. Laboratory Phonology 2: 125–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusz, Ewa. 2022. Effects of imitation and self-imitation practice on L2 pronunciation progress. Topics in Linguistics 23: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengeris, Angelos. 2012. Prosody and Second Language Teaching: Lessons from L2 Speech Perception and Production Research. In Pragmatics and Prosody in English Language Teaching. Educational Linguistics. Edited by J. Romero Trillo. Dordrecht: Springer, vol. 15, pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Levis, John. 2007. Computer technology in teaching and researching pronunciation. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 27: 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Peng, Florence Baills, Lorraine Baqué, and Pilar Prieto. 2023. The effectiveness of embodied prosodic training in L2 accentedness and vowel accuracy. Second Language Research 39: 1077–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Yuhan, Yao Yao, and Jin Luo. 2021. Phonetic accommodation of tone: Reversing a tone merger-in-progress via imitation. Journal of Phonetics 87: 101060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medgyes, Péter. 2001. When the Teacher Is a Non-Native Speaker. Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language. Boston: Heinle & Heinle, vol. 3, pp. 429–42. [Google Scholar]

- Moulines, Eric, and Francis Charpentier. 1990. Pitch-synchronous waveform processing techniques for text-to-speech synthesis using diphones. Speech Communication 9: 453–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, Alene. 2013. Foreign Accent: The Phenomenon of Non-Native Speech. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, Murray J., and Tracey M. Derwing. 2006. The functional load principle in ESL pronunciation instruction: An exploratory study. System 34: 520–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, Keiko, and Kazunori Ozawa. 1990. English speech training using voice conversion. Paper presented at the First International Conference on Spoken Language Processing (ICSLP 90), Kobe, Japan, November 18–22; pp. 1169–72. [Google Scholar]

- Neri, Ambra, Ornella Mich, Matteo Gerosa, and Diego Giuliani. 2008. The effectiveness of computer assisted pronunciation training for foreign language learning by children. Computer Assisted Language Learning 21: 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, Jennifer S. 2006. On phonetic convergence during conversational interaction. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 119: 2382–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardo, Jennifer S., Elisa Pellegrino, Volker Dellwo, and Bernd Möbius. 2022. Special issue: Vocal accommodation in speech communication. Journal of Phonetics 95: 101196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, Jennifer S., Kelly Jordan, Rolliene Mallari, Caitlin Scanlon, and Eva Lewandowski. 2013. Phonetic convergence in shadowed speech: The relation between acoustic and perceptual measures. Journal of Memory and Language 69: 183–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, Jennifer S., Adelya Urmanche, Sherilyn Wilman, Jaclyn Wiener, Nicholas Mason, Keagan Francis, and Melanie Ward. 2018. A comparison of phonetic convergence in conversational interaction and speech shadowing. Journal of Phonetics 69: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, Elisa, and Debora Vigliano. 2015. Self-imitation in prosody training: A study on Japanese learners of Italian. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Speech and Language Technology in Education. Edited by Stefan Steidl, Anton Batliner and Oliver Jokisch. Leipzig: ISCA Special Interest Group SLaTE, pp. 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino, Elisa, Sandra Schwab, and Volker Dellwo. 2021. Listeners pay attention to rhythmic cues when deciding on the nativeness of speech. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 150: 2836–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyanskaya, Leona, Mikhail Ordin, and Maria Grazia Busa. 2017. Relative salience of speech rhythm and speech rate on perceived foreign accent in a second language. Lang Speech 60: 333–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, Katharina, Yan Ke, and Maxime Eskenazi. 2002. Enhancing foreign language tutors—In search of the golden speaker. Speech Communication 37: 161–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quené, Hugo, and L. E. Van Delft. 2010. Non-native durational patterns decrease speech intelligibility. Speech Commun 52: 911–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2023. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Rogerson-Revell, Pamela M. 2021. Computer-Assisted Pronunciation Training (CAPT): Current Issues and Future Directions. RELC Journal 52: 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rognoni, Luca, and Maria Grazia Busà. 2013. Testing the Effects of Segmental and Suprasegmental Phonetic Cues in Foreign Accent Rating: An Experiment Using Prosody Transplantation. Proceedings International on the Acquisition of Second Language Speech 5: 547–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Jory, Kevin D. Lilley, Cynthia Clopper, Jennifer Pardo, and Susannah V. Levi. 2021. Effects of dialect-specific features and familiarity on cross-dialect phonetic convergence. Journal of Phonetics 86: 101041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seferoglu, Gölge. 2005. Improving students’ pronunciation through accent reduction software. British Journal of Educational Technology 36: 303–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sztahó, David, Gábor Kiss, and Klára Vicsi. 2018. Computer based speech prosody teaching system. Comput. Speech Lang 50: 126–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, Keiichi, Robert Port, and Jonathan Dalby. 1997. Effects of temporal correction on intelligibility of foreign-accented English. Journal of Phonetics 25: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofimovich, Pavel, and Wendy Baker. 2006. Learning second language suprasegmentals: Effect of L2 experience on prosody and fluency characteristics of L2 speech. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 28: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, Christine, and Inneke Mennen. 2015. When prosody kicks in: The intricate interplay between segments and prosody in perceptions of foreign accent. International Journal of Bilingualism 20: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigliano, Debora, Elisa Pellegrino, and Massimo Pettorino. 2016. L’apprendimento della prosodia dell’italiano in contesto LS: Uno studio su apprendenti giapponesi. In La Fonetica Nell’apprendimento Delle Lingue. Studi AISV 2. Edited by Renata Savy and Iolanda Alfano. Milano: AISV, pp. 101–15. [Google Scholar]

- Vitale, Marilisa, and Anna De Meo. 2020. Aspetti Prosodici Dell’acquisizione Dell’italiano da Parte di Sinofoni. Roma: Aracne. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Abby, and Kathryn Campbell-Kibler. 2015. Repeat what after whom? Exploring variable selectivity in a cross-dialectal shadowing task. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, Stephen, and Mary Grantham O’Brien. 2013. Perceived accentedness and intelligibility: The relative contributions of F0 and duration. Speech Communication 55: 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrembel, Magdalena. 2007. Metacompetence-based approach to the teaching of L2 prosody: Practical implications. In Non-Native Prosody: Phonetic Description and Teaching Practice. Edited by Jürgen Trouvain and Ulrike Gut. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Wynn, Camille J., and Stephanie A. Borrie. 2022. Classifying conversational entrainment of speech behavior: An expanded framework and review. Journal of Phonetics 94: 101173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, Kyuchul. 2007. Imposing native speakers’ prosody on non-native speakers’ utterances: The technique of cloning prosody. Journal of the Modern British & American Language & Literature 25: 197–215. [Google Scholar]

- Zuengler, Jane. 1982. Applying Accommodation Theory to Variable Performance Data in L2. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 4: 181–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).