There are at least two aspects to consider before we delve into the SO∼AO. The first one involves pronoun structure and features. In

Section 4.1, we focus on this aspect, presenting an approach to Spanish pronouns that pays considerable attention to the possibility they have to agree or not. The second aspect pertains to the argument structures in which the SO∼AO is found. In the verbal domain, although the DP introduced by the item

de can be interpreted as any accusative DP in terms of theta-role, it seems to be out of the canonical Probe-Goal relation with the

v-√ or C-T complexes (

Chomsky 2008). Further, in the adverbial domain, the DP introduced by

de is related to locative meanings like SOURCE, GOAL, or just PLACE. It is the meaning of the adverb, not the meaning of the item

de, that determines each interpretation of the DP. Both observations suggest that we should explore the formal properties of the structures that require the AO in order to clarify the syntactic contexts that trigger

de insertion. Beyond the SO∼AO in other domains, the question should be why the item

de introduces DP arguments so differently interpreted in terms of their theta roles. We explore an answer to this question in

Section 4.2. Once the AO is understood, we will be ready to discuss the SO∼AO as proposed in

Section 4.3.

Section 4.4 focuses on the variation regarding the different scopes that admit SOs following the containment relation observed: [[[nominal domain] adverbial domain] verbal domain].

4.1. Pronouns, Pronouns…

As previously mentioned, we follow

Picallo and Rigau’s (

1999) proposal that SOs are pronouns, as they have personal features. Of course, they codify something else, which is generally understood as a ‘genitive case’ feature. To start, we are going to classify pronouns just following their visible morphological behavior. Accordingly, leaving clitics aside, two groups of pronouns can be distinguished in Spanish: agreeing pronouns and non-agreeing pronouns. Agreeing pronouns are the so-called ‘possessive/genitive’ pronouns and can present double number and gender information because, beyond their person, number, and gender deictic features, they need to agree anaphorically. Representational nouns, such as

picture, allow us to observe this kind of double number/gender marking. As shown in (8), the pronoun agrees with the feminine singular noun

foto ‘picture’, but the participle

sentados ‘seatted’ shows gender and number information that seems to be copied from the internal pronoun features (masculine and plural).

| (8) | Nuestr | -a | foto | sentad | -o | -s |

| | 1PL.MASC | -FEM.SG | picture.FEM.SG | seated | -MASC | -PL |

| | ‘Our picture seated…’ | |

The agreeing group has four or five members, depending on the Spanish variety. The varieties under consideration have four members because 2PL is syncretic with 3SG and 3PL (

Table 2). These four members need to satisfy an agreement-of-nominal-features requirement. When there is not a noun in their scope that works as a Goal for agreement, they present defective nominal morphology in many varieties

7. As expected, there are many other varieties in which the pronoun seems to copy features from somewhere else (see

Feliu Arquiola and Pato 2020 for variation on nominal morphology in adverbs). We focus on defective morphology, but our proposal also applies to other options (see

Section 4.4).

The non-agreeing group of pronouns presents the same deictic features and does not show nominal agreement with external syntactic objects. Spanish, contrary to other Romance languages, has complex elements for the 1PL nosotros (and the 2PL vosotros in the varieties that present this lexical item). The word nosotros is formed by nos and the adjective-like element otros. This adjective-like element needs to copy gender and number features from a scope in which the number is always plural, and gender has deictic reference, as can be observed in (9), where the 1PL clitic nos can be indexed with both 1PL defective and 1PL feminine (see Note 13).

| (9) | Juan | nos | saludo | a | nosotros | /nosotras |

| | Juan | CL.1PL | greeted | to | 1PL.DEF | 1PL.FEM |

| | ‘John greeted us’ | |

Differently from agreeing

nuestr-, the agreement process inside

nosotros/nosotras does never give contrastive features as the example in (8) because the nominal features are copied from the information present in the projections related to

nos. The same explanation applies to 2PL

vosotros/

vosotras8.

The non-agreeing group can have more or fewer members depending on variation. As previously mentioned, the varieties under study do not present the vocabulary item

vosotros for 2PL but

ustedes. For 1SG, there are two items,

yo and

mí, the second being the materialization of 1SG under the scope of a prepositional element (see

Mare 2015 for discussion). The same happens with 2SG

vos/tú and

ti. 1PL presents the gender variation just mentioned (

nosotros/

nosotras), and the third person shows gender and number morphology (

Table 3).

As pronouns have person features, they are referential expressions and, hence, behave like DPs. Building on

Panagiotidis (

2002), we propose that all these pronouns, agreeing and non-agreeing, present a structure with a nominal categorizer, projections for person information, and the projection of number (#). Unlike Panagiotidis and in line with

Vanden Wyngaerd (

2018), we do not assume a projection of D since the projections involved determine the referential character of the pronouns. This point does not in any way affect our proposal for SO∼AO.

Number information can be obtained deictically or by person features hypermarking (

Halle 1997): when the combination of opposite features occurs, the feature on # must be necessary [+PL]. As 3rd person is always interpreted as human, we propose that the node Hum(an) is in the structure of all three personal pronouns,

Harris’s (

1991) gender cloning taking place in this node

9.

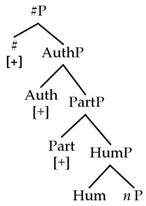

Regarding person, I employ the combination of Participant in Speech Event (Part) and Author in Speech Event (Auth), following

Halle’s (

1997, p. 129) proposal. However, I partially take the Nanosyntax view on features as projections and, consequently, in the system developed here Hum, Part, and Auth project in the structure. The projection PartP can be positively [+] or negatively [−] marked, while AuthP can be absent in the structure. HumP can merge with both Auth and Part

10. The feature [+PL] on # can be the result of two PartP with opposite features or of AuthP and PartP in #’s c-command domain. Given the above, the basic structures for pronouns are schematized below.

| (10) 1SG | (11) 2SG/2PL inclusive | (12) 3SG/PL |

![Languages 08 00233 i001]() | ![Languages 08 00233 i002]() | ![Languages 08 00233 i003]() |

| (13) 1PL inclusive | (14) 1PL exclusive | (15) 2PL exclusive |

![Languages 08 00233 i004]() | ![Languages 08 00233 i005]() | ![Languages 08 00233 i006]() |

These abstract structures are materialized by different Vocabulary Items. A Vocabulary Item (VI from now on) is understood as a relation between syntactic-semantic features/parts of structure and phonological exponents. When Vocabulary Insertion takes place, it is said that a specific part of the structure has been lexicalized. The scheme in (16) represents a VI in terms of the Distributed Morphology framework.

| (16) | /phonological exponent/↔ [syn-sem features] |

The difference between agreeing and non-agreeing pronouns is in the nominal categorizer requirements.

Mitrović and Panagiotidis (

2020) propose that adjectives are bicategorial elements in all languages, and that is the reason why they behave both as nouns and as verbs. The authors argue against adjectivizers while defending the proposal that the elements that are recognized as adjectives across languages present a verbalizer and a nominalizer in their structure. Typological studies show that adjectives are categorially ambivalent because they do not equally combine nominal and verbal characteristics. Simplifying Mitrović and Panagiotidis’ analysis, the authors argue that the predominance of one categorizer’s characteristics triggers the excorporation of the other categorizer. In Indo-European languages, it would be the verbalizer in the complement of

n the one that excorporates (17).

This bicategorial property explains that Indo-European adjectives are modified by adverbs—like verbs—and present nominal features like gender and number by φ-agreement (concord).

Going back to pronouns, it is clear that the members of both groups behave in all relevant contexts as arguments—i.e., as kinds—not as sub-events, and that is the reason why we do not consider that there is a verbalizer in their structure. However, agreeing properties can follow from the features of the nominalizer. Our hypothesis is that there are two kinds of

ns: one with unvalued φ- features (

n[uφ]) and one without φ- features (

n) at all.

n[uφ] remains in situ while

n merges internally to Hum, forming a complex node

n/Hum. In the nominal domain,

n[uφ] satisfies this requirement by copying number and person features from the DP in its scope. The result of this is that agreeing features are lexicalized independently of pronominal information. In the adverbial and the verbal domain, there is no DP which

n[uφ] can agree with, but nominal morphology is also recognized. As will be argued in

Section 4.4, this hypothesis explains the SO∼AO and seems to fit well with the empirical evidence of agreeing possibilities in non-nominal domains.

4.2. Arguments Headed by de

We will now move on to discuss argument structure assuming a neo-constructionist framework, according to which there is nothing such as lexical items that select one or more arguments. Conversely, argument structure properties and the interpretation of arguments arise from their

locus in the syntactic structure.

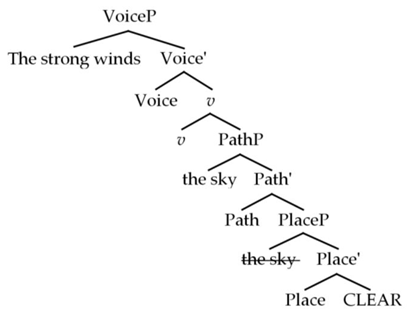

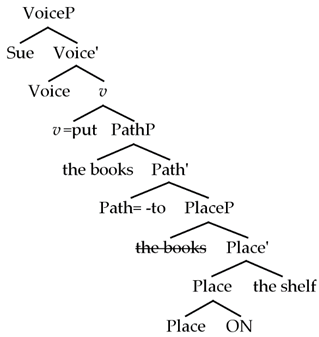

Acedo-Matellán (

2016) proposes argument configurations for verbs, which are the result of combining relational projections (VoiceP, PathP, and PlaceP) with non-relational elements (DPs and Roots). Place establishes a predicative relation, Path encodes a transition, and Voice introduces the Originator of the event. Roots and DPs are interpreted according to the position they occupy in the structure. For instance, a DP in the scope of VoiceP can only be interpreted as an Agent or a Cause. The DPs in the domain of lower heads are interpreted as Themes or Locations depending on the relation with the head they merge with. The configuration in (18) represents the structure proposed by

Acedo-Matellán (

2016, p. 35) for transitive events of change of state/location, with

v as a verbalizer according to

Marantz’s (

1997)

Categorization assumption.

| (18) a. | b. |

![Languages 08 00233 i008]() | ![Languages 08 00233 i009]() |

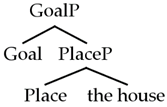

Some cartographic studies, such as

Fábregas (

2007a),

Pantcheva (

2011), or

Gibert Sotelo (

2017), propose more complex structures for locative interpretations based on crosslinguistic variation. Pantcheva, for instance, proposes that notions like Source as well as Goal project in the structure hierarchically. In (19), the item

to would lexicalize both Place and Goal, while in (20)

from lexicalizes Place, Goal, and Source.

| (19) To the house | (20) From the house |

![Languages 08 00233 i010]() | ![Languages 08 00233 i011]() |

Beyond these technical observations, there are some relevant descriptive points to consider. First, the theta roles for the arguments involved in the SO∼AO are related, one way or another, with PlaceP in both the verbal and the adverbial domains. Second, although there are some restrictions in the SO∼AO in the nominal domain (see Note 4), they do not affect the theta-role interpretation for complements of Place, i.e., Themes and Locations. Third, as we observed in

Section 3, there can be items different from

de that introduce the DP, but interestingly, they are VI related to projections proposed for goal, source, or place interpretation. Finally, in all the cases, we find a predicative relation in which the argument is marked in some way. For the adverbial and the nominal domain, we do not expect to find, for instance, accusative case markers because there is nothing such as a

v-√ that works as a Probe in a specific context (see

Chomsky 2001,

2008). However, in the verbal domain, we need to explain why this kind of internal argument is not part of the Probe-Goal relation with a

v-√.

Demonte (

1991) focuses on the so-called prepositional verbs in Spanish and distinguishes two major groups

11 according to the following pattern of behavior: A. the possibility of dispensing with the prepositional phrase (PP); B. agentivity; C. the option of being taken as a complement in a causative construction; D. PP extraction from weak islands. Interestingly, as follows from the results, the verbs under analysis behave exactly as one of Demonte’s types: the type that presents an agentive DP and in which the PP is not a syntactic argument.

| (21) | a. | –¿Juan abusó de vos? | [PP omission] |

| | | ‘Did Juan abuse you?’ |

| | | –No, no abusó. |

| | | ‘No, he did not’ |

| | b. | –¿Juan piensa en vos? |

| | | ‘Does Juan think about you?’ |

| | | –No, no piensa. |

| | | ‘No, he does not’ |

| (22) | a. | Juan abusó de sus compañeros para conseguir la beca. | [Agentivity] |

| | | ‘Juan abused his partners to get the scholarship’ |

| | b. | Juan piensa en sus compañeros para conseguir la beca. |

| | | ‘Juan thinks about his partners to get the scholarship.’ |

| (23) | a. | Esto hizo a Juan abusar de sus compañeros. | [Causative Constructions] |

| | | ‘This led Juan to abuse his partners’ |

| | b. | Esto hizo a Juan pensar en sus compañeros. |

| | | ‘This made Juan think about his partners.’ |

| (24) | a. | ¿De quiéni no sabés [CP si Juan abusó ti]? | [Extraction from weak islands] |

| | | ‘Who do you not know if Juan has abused?’ |

| | b. | ¿En quiéni no sabés [CP si Juan pensó ti]? |

| | | ‘Who do you not know if Juan has thought about?’ |

Gallego (

2022) revisits Demonte’s proposal and concludes that this type of prepositional verbs are unergative predicates (not special transitive predicates as in Demonte), in which the PPs are lexical adjuncts in

Mateu (

2002) terms: ‘adjuncts related to the specific roots as part of their non-compositional (read ‘encyclopedic’) meaning’ (

Gallego 2022, p. 303). In general, we agree with Gallego’s analysis, but we derive the idea of ‘lexical adjuncts’ from the syntactic structure so as to capture Demonte’s intuition about transitivity. In an attempt to explain both properties, we focus on defectiveness as the impossibility of a head to project a Specifier position for an argument. The result of this is that the corresponding head merges in the structure, contributing to the relevant interpretation, but as a defective head, the argument that this head should introduce can be omitted, and if present, it must be introduced by another head in the scope of the main projection. The proposal on defectiveness has been explored in relation to Voice, the head that introduces DPs interpreted as agents (25a). When Voice is defective, the predicate does not lose the agentive interpretation, as, for instance, in Spanish periphrastic passive constructions (25b) or

se constructions (see

Pujalte and Saab 2012, for instance). Rather, the predication is interpreted as being caused by an agent that is not present in the main structure but can be reintroduced by a preposition (25c).

| (25) | a. | Juan corrigió los parciales. |

| | | ‘Juan has reviewed the exams.’ |

| | b. | Los parciales fueron corregidos. |

| | | ‘The exams have been reviewed.’ |

| | c. | Los parciales fueron corregidos por Juan. |

| | | ‘The exams have been reviewed by Juan.’ |

Our proposal is that in (25c), the PP

por Juan ‘by Juan’ is an adjunct of Voice: the DP

Juan is introduced in the structure by a

p(redicative relator) merged in the domain of VoiceP. This is the reason why the DP is interpreted as an agent, and the item

por ‘by’ cannot alternate with other prepositions:

por is the Vocabulary Item that lexicalizes a p under the scope of VoiceP. Building on the idea of defectiveness, we would like to argue that most of the verbs under discussion, if not all of them, are the result of the impossibility of the head PLACE to introduce a DP argument. This means that the interpretation of the event is obtained compositionally thanks to the presence of that head (and the others involved), but the syntactic conditions for transitivity are not met because no DP merges in the relevant positions owing that PLACE is defective. Consequently, there is a required argument that can only be introduced in the area of this head—in fact, it will be interpreted as Theme or more specific kinds of locations as mentioned above—but it is hidden from the main structure’s Probe-Goal relationships (

Chomsky 2001). Accordingly, the unergativity proposed by Gallego is derived from a defective transitive structure, as in Demonte’s analysis. We use

p in (26) for ‘predicative relation’ in order to distinguish it from Place in the main structure, but both represent the same kind of relation.

| (26) | Jack habló de Jemmy |

| | ‘Jack talked about Jemmy’ |

| | ![Languages 08 00233 i012]() |

One of these verbs—although most probably not the only one—behaves like the other group of prepositional verbs in Demonte’s classification:

gustar (see

Bouzouita and Pato 2019 for the SO∼AO with this verb). Since Demonte and Gallego agree that this group consists of unaccusative predicates that select a small clause with a PP—our PlaceP—(see

Gallego 2022, p. 305), the conditions for the SO∼AO would be given without further ado.

Finally, the cases in which

de seems to alternate with other items can be explained under the same system. In (26), for instance, if

p merges with a root-like SOBRE or EN (see for instance (18b)), it acquires a more specific encyclopedic kind of relation; otherwise, the less specified item

de lexicalizes

p when no root is merged. We follow the same reasoning proposed for

v lexicalization: some verbal elements like

be,

go and

do just lexicalize a

v in a particular predicative structure when no more specific roots are merged—or from other perspectives [BE], [GO] and [DO] are features or ‘flavours’ on this little

v (see

Folli and Harley 2005)—as in the contrasts between

do a dance and

dance. Furthermore, the SO would not alternate with an introducer different from

de because these introducers are not primitives in the structure. In other words, the SO requires that there be a

p/Place in the structure, not that this

p/Place lexicalizes in one way or another.

4.3. The SO∼AO

Now that we have the basic ingredients let us move on to the SO∼AO. As discussed in

Section 4.1, the arguments involved in the alternation are pronouns that can be materialized by different Vocabulary Items, depending on the syntactic structure and the features in it. On the other hand, the scopes in which the SO∼AO is found have in common that the DPs/pronouns this paper focuses on are introduced by the head Place/p that establishes a predicative relation. Out of the nominal domain, all these arguments are interpreted in a very restrictive way: they are either themes or locations. Last but not least, the general panorama shows that agreeing syntactic objects (examples in a) and

de + non-agreeing syntactic objects (examples in b) are in complementary distribution.

| (27) | a. | La | pesca | ballen | -er | -a |

| | | the.F.SG | fishing.F.SG | whale | -SUF | -F.SG |

| | | ‘Whale fishing’ |

| | b. | La | pesca | de | ballen | -a | -s |

| | | the.F.SG | fishing.F.SG | of | whale | -F | -SG |

| | | ‘Whale fishing’ |

| (28) | a. | Much | -a | -s | person | -a | -s |

| | | many | -F | -PL | people | -F | -PL |

| | | ‘Many people’ |

| | b. | Un | montón | de | person | -a | -s |

| | | a.M.SG | lot.M.SG | of | people | -F | -PL |

| | | ‘A lot of people’ |

| | | | | | | | | |

| (29) | a. | Una | amiga | nuestr | -a |

| | | a.F.SG | friend.F.SG | our | -F |

| | | ‘A friend of us…’ |

| | b. | Una | amiga | de | nosotros | /de | Juan |

| | | a.F.SG | friend.F.SG | of | we.M.PL | of | Juan |

| | | ‘A friend of us/of Juan…’ |

| | | | | | | | | |

In (27a), the adjective ballenera ‘of whales’ agrees in gender and number with la pesca ‘fishing’; in (28a), the quantifier muchas ‘many’ agrees in gender and number with personas ‘people’; and in (29a) nuestra ‘our’ agrees with una amiga ‘a friend’. When each syntactic object presents its own gender and number features, the relation between them seems to be materialized by the item de. The same happens in the SO∼AO, with the difference that—at least in the varieties under study—it is not easy to see agreement markers because we find the default (DEF) nominal item -o.

| (30) | a. | Cerca | nuestr | -o |

| | | near | 1.PL | -DEF |

| | | ‘Near us’ |

| | b. | Cerca | de | nosotros | /de | Juan |

| | | near | of | we.M.PL | of | Juan |

| | | ‘Near of us/of Juan…’ |

| | | | | | | | | |

| (31) | a. | Habló | nuestr | -o | |

| | | talked.3SG | 1.PL | -DEF | |

| | | ‘(S)he talked about us’ |

| | b. | Habló | de | nosotros | /de | Juan |

| | | talked.3SG | of | we.M.PL | of | Juan |

| | | ‘(S)he talked about us/about Juan’ |

| | | | | | | | | |

| (32) | a. | Juan está orgulloso | nuestr | -o12 |

| | | Juan is proud | 1.PL | -DEF |

| | | ‘Juan is proud of us’ |

| | b. | Juan está orgulloso | de | nosotros | /de | Estefanía |

| | | Juan is proud | of | we.M.PL | of | Estefanía |

| | | ‘Juan is proud of us/of Estefanía’ |

| | | | | | | | |

All things considered, it appears that SOs are not just person features, contrary to

Bertolotti’s (

2017) proposal, but they represent phonological exponents that materialize not only the relevant person/number information but also the predicative projection that introduces it as an argument. In other words, the difference between

nosotros and

nuestro is that the first only materializes the pronominal features (33), while the second, more specifically

nuestr-, lexicalizes pronominal information as well as the predicative relator (

p/Place) (34). In fact, the proposal here is that the syntactic objects named adverbs or adjectives have the same property: they also lexicalize a relational head (or more than one). This fits well with Mitrović and Panagiotidis’ analysis of adjectives because the nominalizer

n[uφ] relates to nominal features (gender and number), which are lexicalized independently by the corresponding vocabulary items.

| (33) de nosotros/nosotras13 | (34) nuestr- |

![Languages 08 00233 i013]() | ![Languages 08 00233 i014]() |

The lack of features on

n motivates head movement to Hum, where deictic gender features are located

14. The result is that when vocabulary insertion takes place, there will be just one node—the complex node

n/Hum—for gender information lexicalization. Non-agreeing pronouns like

nosotros never lexicalize PlaceP, and that is why this head/phrase must be lexicalized by other vocabulary items,

de ‘of’ being the default one in Spanish. The same happens with other DPs, i.e., lexical arguments (

de la mesa ‘of the table’) and proper nouns (

de Juan ‘of Juan). On the other hand,

n[uφ] needs to value its features from its local domain, but whichever these features are, the information related to this

n[uφ] lexicalizes independently. The second difference regarding lexicalization is that what we call agreeing pronouns also lexicalize Place (34), and this is the reason why they are not found as complements of prepositions or as sentence subjects or direct objects (consider the structures in

Section 4.2).

In brief, the general requirement for triggering the SO∼AO is having structures like (33) and (34), where the only difference is the kind of

n involved. If

n has no features to value, it remains subsumed into the deictic information in the structure and is lexicalized together with the other projection. The vocabulary items that lexicalize this information cannot lexicalize Place, i.e., Place is not part of the structure and the features related to these phonological exponents. In contrast, when

n is

n[uφ], it must (somehow) value the relevant features, and once valued,

n can be lexicalized. Hence, the rest of the structure is going to be lexicalized by a Vocabulary Item that also includes Place. This analysis captures

Mare’s (

2014) observation about the complementary distribution between the presence of the item

de and nominal markers. Furthermore, leaving aside the idea of possession or genitive case, it allows us to pay attention to a clear pattern related to the introduction of arguments: the SO∼AO occurs when a pronominal argument is introduced as a complement of

p/Place. Our next goal is to explain the two kinds of variation observed: (1) restrictions on the SO∼AO with adverbs, adjectives, and verbs and (2) variation regarding nominal markers resulting from agreement.

4.4. On Variation and Beyond

Now that we have the bases for SO∼AO, it is time to discuss why SO occurrence is restricted in many varieties (35).

| (35) | a. | Una amiga tuya (ok for all Spanish varieties) |

| | | A friend of yours |

| | b. | *Cerca tuyo (* for some Spanish varieties) |

| | | Near of you |

| | c. | *Me acordé tuyo (* for most of Spanish varieties) |

| | | I remembered you |

| | d. | *Estoy orgullosa tuyo (* for most of Spanish varieties)15 |

| | | ‘I am proud of you’ |

Regardless of the variation observed, it is remarkable that there seems to be a kind of containment relationship among the domains that admit the SO. The varieties that present SO in the adverbial domain also show it in the nominal domain, and the varieties in which the SO is found in the verbal (and in the adjectival) domain are also found in the adverbial domain.

| (36) | [[[nominal domain] adverbial domain] verbal domain] |

We have argued that the introduction of arguments that can be materialized by the SO∼AO in the three domains share the characteristic of being the complement of a predicative relator (

p/Place). This is the first formal property that could motivate what

Bertolotti (

2017) calls

constructional analogy. However, while the presence of this predicative relator is necessary, it is not enough to explain the containment represented in (36).

The analysis proposed by

Mitrović and Panagiotidis (

2020) shed light on this puzzle. As was remarked in

Section 4.1, they argue against adjectivizers—or adverbializers—and propose that adjectives—as well as adverbs—are bicategorial elements with an

n and a

v in their structure. It means that, following the *ABA-effect way of reasoning, it is desirable, in fact, that a domain that presents a nominal categorizer triggers the SO∼AO before a domain that does not have

n. Moreover, as the adverbial domain is also characterized by the presence of a verbalizer, the extension of the SO∼AO to an exclusive verbal domain also follows. Found and unfound (*) SO containment relations are shown in background color in

Table 4.

The challenge now is to define the features that motivate the different possibilities of SO insertion in Spanish varieties. It seems to be the case that SO insertion is conditioned by the possibility of n[uφ] to value the relevant features. This kind of agreement operation takes place canonically in the nominal domain, where there is a nominal element with relevant features to value. In some varieties, when a structure like (34) merges in the scope of v, n[uφ] cannot value its φ-features and, consequently, it is computed as an n, giving rise to the insertion of a non-agreeing pronoun. As already explained, the result of this insertion is the AO. However, let us consider some ideas that can help us to further understand this topic.

First of all, contrary to previous research, we argue that the presence of SOs in non-nominal domains is not due to the characteristics of SOs but to the ‘solutions’ provided by each variety when the nominalizer in a pronominal structure is a n[uφ]. We propose that there are different solutions:

Hypothesis 1. When n[uφ] cannot value its features, the derivation is ruled out. It means that only the structure in (33) results in a good derivation.

Hypothesis 2. When n[uφ] cannot value its features, n[uφ] is computing as an n. It means that in Syntax, both (33) and (34) result in a good derivation. However, as n[uφ] is computed as an n, conditions for insertion change, and SOs are ruled out for vocabulary insertion.

If we follow hypothesis 2, we can go a step further because if

n[uφ] is not ruled out, some varieties could admit a

n[uφ] in the structure until it can value features with other

n, at least, a defective one. This could be the case of SOs in the adverbial domain. As pointed out by different authors (

Bartra and Suñer 1992,

1997), some adverbs’ morphology kicks in as a default option. Interestingly, it could also explain why the SO is not found with the same extension across varieties in the adjectival domain. As already mentioned, adverbs and adjectives are bicategorial, but SO is more frequent with adverbs than with adjectives. This could be caused by

n features again: while adverbs present default φ-features on

n—let us use [-F] and [-PL] for default—adjectives must value their φ-features inside the DP they merge with. This ‘delay’ could lead to the

n[uφ] of the pronoun being computed as an

n, and we know what the result is: the AO is the only possibility for materialization

16.

Finally, there would be varieties in which a n[uφ] that cannot value its φ-features with a nominal element attributes them a defective value, again [-F] and [-PL]. When this happens, it can trigger vocabulary insertion, and an SO can materialize the rest of the structure.

Table 5 summarizes the above-mentioned possibilities. We call V(ariety)1 the most restrictive variety, which only admits SOs in the nominal domain. V4 is on the opposite side: it admits SOs in the four domains. V2 admits SO with adverbs as well as in nouns, and V3 admits SOs with verbs also.

| (37) | a. | Cerca tuyo (with a [+F] or a [-F] referent) |

| | b. | Cerca tuya (with a [+F] or a [-F] referent) |

| | c. | Cerca tuya/tuyo (depending on the gender information of the referent) |

(37a) would exemplify varieties in which n[uφ] is marked by default ([-F]; [-PL]), and the phonological exponent for these default features is /o/. The default option and the defective features can be different across varieties, and this seems to be the case in (37b), where the exponent /a/ lexicalizes the nominalizer. The third option is the deictic solution: n[uφ] values its features with the deictic features in the pronoun (37c). Interestingly, none of these ways of solving the problem of having a n[uφ] out of the nominal domain affects the interpretation provided by the Syntax. It only affects the conditions for vocabulary insertion.