Abstract

This paper deals with the use of anche (“also”) by German heritage speakers of Italian (“IHSs”). Previous research showed that anche and its German counterpart auch share many features but also display language-specific characteristics. According to previous research on bilingualism, heritage speakers show cross-linguistic influence (“CLI”) when a linguistic phenomenon is at the syntax–pragmatics interface and there is a partial overlap in the two languages at stake. Therefore, we expect the use of anche in IHSs to be influenced by CLI. By analysing data from a semi-spontaneous corpus, we investigate the production of anche in order to understand which factors shape the grammar of the IHSs. Our results indicate that a subset of IHSs uses anche in the same way as in homeland Italian. The other informants display CLI effects of different types: on the one hand, they have two positions in the clausal structure for anche dedicated to different syntactic–pragmatic contexts, as in German, and they overextend the use of anche as a modal particle. On the other hand, the intonational properties of anche are not affected by CLI.

1. Introduction

The study of language relied for many decades on the idea that the language rules interiorized by monolingual speakers of that language be the norm1. This “monolingual bias” was also at the basis of the generative theory: in its first years, Chomsky’s approach relied strongly on the idealized image of a monolingual speaker in a monolingual environment: “Linguistic theory is concerned primarily with an ideal speaker-listener, in a completely homogeneous speech community, who knows its language perfectly […]” (Chomsky 1965, p. 3).

In the last decades, however, bilingual and multilingual speakers of different types, among them Heritage Speakers (‘HSs’)2, have been paid increasing attention to: the study of their grammatical representations, as visible both in production and in comprehension, allows us to improve our general knowledge about the human language faculty, and, more specifically, about the syntactic competences and on the limits of variation within human language. This insight has led to the fundamental realization that heritage languages in adults are not the result of an “incomplete acquisition”: as observed by Kupisch et al. (2017) et seq., there should be a clear conceptual difference between development (during the acquisition process) and outcomes, because only an evolving grammar can be conceived as “incomplete”. An adult heritage grammar, on the other hand, is by definition complete, because, as observed by Polinsky (2018), adult heritage grammars are always internally coherent, albeit different from the grammars of speakers living in the homeland and from those of their parents.

In addition, Polinsky (2018) also observes that it is uninformative to compare adult HSs with speakers in the homeland “if we want to understand how heritage language acquisition works” (Polinsky 2018, p. 11) because the two varieties are not directly related: first of all, the baseline for HSs is the language of first-generation, attrited immigrants3, or of other HSs. In addition, speakers in the homeland are exposed to the language for their whole life and innovate in manyfold ways even when they are adults. Furthermore, their language is characterized by the presence of more registers, while HSs often lack education in the heritage language and thus may have low proficiency in the written language and in diaphasically high registers.

However, if our aim is a theoretical analysis of an adult HSs’ grammar, then the comparison makes sense: heritage languages can be considered as peculiar varieties of the homeland language (cf. also Nagy 2016), so that “the task becomes an exercise in dialect comparison” (Polinsky 2018, p. 349). It is exactly this view of heritage languages that we would like to pursue in this paper: we suggest that we can adapt the tools developed for the analysis of dialectal variation by the generative framework to a formal, qualitative analysis of heritage languages4. As we can compare the mechanisms that differentiate a property in two genetically related dialects, or between a dialect and the standard language, we can do the same by comparing a heritage language with the homeland language since the heritage language is just one of its varieties5.

Our study addresses the topic of transfer from the dominant language (i.e., the language in which a speaker is more proficient) in HSs, by comparing a variety that evolved in a context of language contact (heritage Italian in Germany, henceforth “HerIt”) with a variety, or more precisely a group of varieties, spoken by speakers that have grown up in Italy, without having such a strong experience of language contact (“Homeland Italian”, henceforth “HomIt”)6. The phenomenon chosen is the syntax of additive particles, which is governed by different rules in Italian and in German, the dominant language of the analysed heritage speakers of Italian (“IHSs”). For these speakers, German is the dominant language at a community level as well.

In the case discussed in this paper, there are at least two explanations for the deviations of HerIt from HomIt: the Italian additive particle anche might have changed in the production of the attrited parents and community members (which are HomIt speakers), and the children acquired it from them, or the attrited parents produced anche as in the homeland variety, but the second-generation immigrants reanalysed its rules as an effect of German, their dominant language7. In both cases, we expect the production of anche to be particularly subject to cross-linguistic influence (“CLI”) because the phenomenon is at the interface between syntax and pragmatics/discourse. This property has been claimed to pose particular difficulties for bilingual speakers (“Interface Hypothesis”, Sorace 2004; Tsimpli and Sorace 2006; Serratrice and Sorace 2009) because it requires more processing resources. In addition, in the case that the HSs themselves are the source of the innovation in the use of anche (and consequently they differ from the baseline), a second reason to expect CLI is given by the fact that the use of anche partially overlaps with the use of the corresponding German particle auch (see Section 2). According to Hulk and Müller (2000), Müller and Hulk (2001) and Platzack (2001), a partial overlap is a necessary condition for CLI to occur. In fact, these studies have shown that it is easier for bilinguals to acquire properties that are completely different in the two languages they are exposed to than to master a property that has some, but crucially not all, features in common between the two languages. As far as anche/auch are concerned, there is a partial overlap both in syntax (in both languages anche/auch occurs in the tense phrase, the TP, in a series of contexts8) and in prosody (related to different word orders); but the partial overlap also concerns the distribution of anche and auch across sentence types, as far as their use as modal particles is concerned.

To investigate how IHSs cope with the use of anche and to which extent their use of anche can be interpreted as the result of CLI, we organized the paper as follows: In Section 2 we provide a background of the three uses of Italian anche and German auch and highlight the properties they share and those they do not. Section 3 gives an overview of previous studies on the acquisition of anche and drawing on these puts forward some hypotheses on the use of anche by IHSs. Section 4 presents the methodology of our corpus study. In Section 5, we report the results of our analysis. Finally, Section 6 discusses the results, and Section 7 contains the conclusions.

2. Functions of Auch and Anche

Recent studies (Bidese et al. 2019; Moroni and Bidese 2021a; Cognola et al. 2022) show that Italian anche and German auch display the same functions but behave to some extent differently with respect to their syntactic, prosodic, and pragmatic properties. In this section, we describe the three functions of anche and auch in the two languages and highlight the asymmetries in their realizations.

2.1. Additive Particle

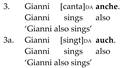

In their function as additive elements, anche and auch mark the addition of an element denoted by a constituent to a set of contextually relevant alternatives, for which the sentence holds. The constituent on which anche and auch scopes is called the Domain of Association (henceforth “DA”, see Andorno and De Cesare 2017). Both in Italian and German, the additive particle can directly precede its DA, as in (1), taken from Pasch et al. (2003, p. 577) and (2), our translation of (1) into Italian9:

In both cases, auch and anche signal that Peter must be added to a set of persons (Hans, Julia), for which the proposition “x called Lucie” holds. Anche and auch as additive particles interact with the focus-background structure of the sentence in that their DA is stressed/focalized. Therefore, they are also called focalizers or focus particles in the literature (cfr. Andorno 2000; König 1991; Dimroth 2004; De Cesare 2019, p. 79)10.

|

|

When auch and anche have the whole predicate as their DA and the verb form is synthetic, they must both be right adjacent to the verb, as in (3) from Andorno (2000, p. 95) and (3a) derived by us from (3):

|

For Italian, this holds both for main and subordinate clauses. By contrast, as German subordinate clauses are verb-final, auch in this case is on the left of the verb (and of its object), as in (3b):

|

Moreover, Andorno (2000, pp. 93–94) points out that when the DA is preverbal, Italian anche can possibly be placed right adjacent to it, as in (3c) (derived by us from (3)) and (3d) taken from Andorno (2000, p. 94):

|

However, the grammaticality of structures such as these is still a matter of debate in the literature and is probably subject to regional variation: examples like (3c) and (3d) seem to be more acceptable in central and southern varieties of Italian, and in an informal spoken register.

Except for cases such as (3) and (3c)–(3d), Italian anche is always left adjacent to its DA (see among others Andorno 2008; Bidese et al. 2019, pp. 350–51; Cognola et al. 2022, p. 214). Thus, structures such as (4) and (5) are taken to be ungrammatical11:

|

|

By contrast, the order “DA+additive particle” is very frequent in German and belongs to the main structures in which auch can be embedded. In this case, auch can be either adjacent to its DA (ex. (6)) or separated from it in what is often called “discontinuous construction” (cf. Cognola et al. 2022, (7)):

Note that in both cases auch also follows the inflected verb, i.e., it is in a TP (i.e., Tense Phrase, within the minimalist framework) position. As in structures such as (1) above (auch+DA), auch in (6) and (7) seems to operate on its DA by adding the element denoted by it to a set of alternatives, the only difference lying in the information structure. In (1a) and (6a)–(7a), we represent the two different information structures:

|

|

- 1a. Auch [PETER]DA/Focus hat bei Lucie angerufen.

- 6a. In den Urlaub ist [Johannes]DA/Topic [AUCH]Focus gefahren.

- 7a. [Johannes]DA/Topic ist [AUCH]Focus in den Urlaub gefahren.

Our definition of the information structural categories of topic and focus draws on Büring (1997). By focus, we understand a syntactic constituent that bears the most prominent accent within the utterance and encodes the most relevant piece of information in the given context. By topic, we refer to a constituent that encodes the element that the utterance is about (see also Uhmann 1991; Moroni 2010, pp. 43–60). In (1a) the DA Peter builds the focus. In this case, the additive particle auch signals that the encoded proposition (“jemand hat bei Lucie angerufen”, “someone called Lucie”) holds for more than one person, one of those being Peter. By contrast, accented auch in (6a)–(7a) is the focus12 and its DA is a topic (Krifka 1998; Nederstigt 2003, pp. 180–86; Dimroth 2004, pp. 151–64; Reimer and Dimroth 2021). In this case, the focalized information is the additive operation encoded by auch itself, i.e., the fact that the proposition also holds for the topic Johannes. Although the difference at the information structural/theoretical level is clear, the distribution of the two structures in natural language data is not always easy to track, that is, the two structures can appear in similar contexts and their difference in natural data is very subtle (see Reimer and Dimroth 2021; Dimroth 2004, pp. 154–55).

In this respect, Reimer and Dimroth (2021) carried out a corpus study on auch in spontaneous spoken data and showed that the presence of alternatives in the communicative context influences the choice between unaccented auch as an additive particle, i.e., the structure auch+DA (as in our example (1a)), and accented auch, i.e., DA+auch (as in our examples (6a) and (7a)). In their data, accented auch tends to occur when alternatives are explicit in the context, while unaccented auch can occur when alternatives are present in the context as much as when no alternatives are available (Reimer and Dimroth 2021, p. 11). Furthermore, the number of alternatives also seems to play a role in that accented auch tends to occur when only one alternative is present in the context whereas unaccented auch can also occur with more alternatives. In sum, Reimer and Dimroth’s (2021) study shows that accented auch (i.e., the structure DA+auch) and unaccented auch (i.e., auch+DA) not only display a different information structure but also correlate with different contextual features 13.

Unlike German “DA+accented auch”, discontinuous structures of the type “DA+accented anche” are taken to be either ungrammatical (Bidese et al. 2019, p. 350; Cognola et al. 2022) or marginal/rare. Andorno (2000, p. 96), for instance, maintains that the pattern “DA+accented anche” can in some cases be realized, but that it seems to be restricted to spoken Italian, as in (8):

According to Andorno, anche is accented and its DA is the constituent in the front position of the sentence il negozio sulla piazza, i.e., in (8) anche behaves like German auch in the example (7) above. Since our control data for HomIt (see Section 4 below) do not present any occurrences of this structure, following Bidese et al. (2019) and Cognola et al. (2022), we consider structures such as (8) as marginal in HomIt; however, we cannot exclude that they could be accepted by some speakers or in some regional varieties/registers because our reference corpus for HomIt does not cover all registers and geographical areas of Italy.

|

In Italian, the discontinuous construction with the DA in the first position can occur only when the DA is resumed by a strong pronoun, as pointed out by Kolmer (2012, p. 191) (see also De Cesare 2015, p. 40; Cognola et al. 2022, p. 216). Example (9) is an example taken from De Cesare (2015, p. 40):

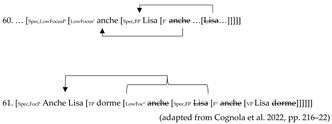

In this respect, Andorno (2008) argues that Italian anche follows the principle of right scope in opposition to German auch, which can often scope over a DA on its left (ex. (6) and (7)). Within the cartographic framework, Cognola et al. (2022) argued that this difference between German auch and Italian anche results from asymmetries in the movement properties of the two particles, i.e., from the fact that the DA of the additive particle can be moved alone to Spec,CP only in German, whereas this movement is not possible in Italian (see Section 6 below).

|

2.2. Sentence Connective

Auch and anche also serve as connective adverbs and connect two clauses. In this case, they mark the clause as an element that must be added to a set of items to which the preceding clause belongs. Let us first look at German auch. Examples (10) and (11) illustrate the two possible positions auch can occupy as a connective. In (10), it appears in sentence-initial position, whereas in (11), derived from (10), it follows the verb:

|

|

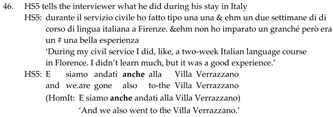

When used as a sentence connective, Italian anche can appear either in a syntactically non-integrated position or syntactically integrated in a postverbal position. As for the parenthetical use, we report the following examples that we have found in an online search14:

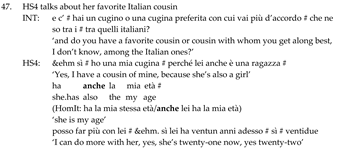

|

|

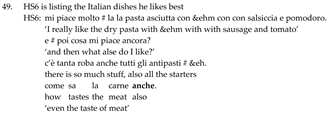

|

Example (15) illustrates the use of Italian anche as a sentence connective in the postverbal position. It is taken from Moroni and Bidese (2021a, p. 203) who carried out an empirical study drawing on Italian spoken data from the LIP corpus (see Section 4 below for a description of the LIP corpus):

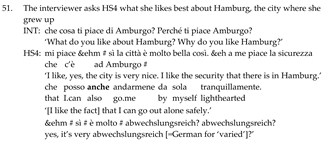

|

Unlike German auch, anche as a sentence connective can never appear in a syntactically integrated sentence-initial position, as pointed out by Andorno (2000, p. 100), who illustrates this restriction with the following two examples:

|

|

To sum up, both auch and anche share the same function of sentence connective but display asymmetries in their syntax: German auch can only appear within the sentence structure, either in syntactically integrated sentence-initial position or after the verb. By contrast, Italian anche can either appear in syntactically non-integrated initial, medial or final position or as a syntactically integrated item but only in postverbal position, a position that is frequently found in both languages (see Section 2.4 below, Table 1). In addition, it is possible that the frequency with which the sentence connectives auch and anche are used may differ, with the Italian word inoltre (“in addition”) potentially serving as the functional equivalent of auch in many cases (see Andorno and De Cesare 2017).

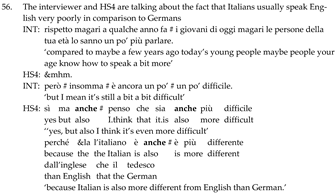

2.3. Modal Particle

Finally, auch and anche can be used as modal particles. In this case, they display the following constitutive properties of this functional class (see Thurmair 1989; Müller 2014, a.o.):

- they are always syntactically integrated and never appear in sentence-initial position (not even when this position is syntactically integrated);

- their occurrence is restricted to certain sentence/illocutive types;

- they express modality at the sentence level.

As for their syntax, it must be specified that auch and anche as modal particles must appear after the finite verb.

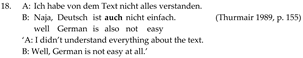

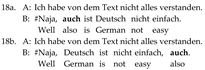

|

|

If auch and anche occur in another position, for instance, fronted or moved to a clause-external position, the modal interpretation is ruled out:

|

|

The meaning conveyed by auch and anche as modal particles relates to their additive semantics in that the speech act expressed by the auch/anche utterance is marked by the speaker as “to be added to the communicative situation”, which characterizes the utterance/speech act as coherent with the preceding context and thus expectable (Thurmair 1989, pp. 155–60; Bidese et al. 2019, p. 352).

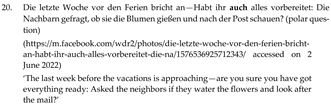

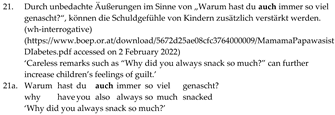

As for the sentence type, anche as a modal particle seems to be restricted to declarative or exclamative sentences such as (19) above15. By contrast, the modal particle auch is compatible with more sentence types, as illustrated in (18) above (in which auch appears in an assertion) and in the following examples (20)–(23a):

|

|

|

|

|

2.4. Summary: Partial Overlap

In this section, we showed that auch and anche share the same three functions (additive particle, sentence connective and modal particle) but that they are characterized by a partial overlap with respect to their syntactic and prosodic behaviour and their compatibility with different sentence types. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of auch and anche in their three functions.

Table 1.

Comparison of the properties of auch and anche.

As Table 1 shows, each function of anche/auch exhibits some degree of overlap. In particular, only German auch can follow its DA (and the inflected verb) bearing a focus accent in the discontinuous construction. As for auch/anche as sentence connectives, only Italian allows for the particle to be in parenthetical constructions, i.e., syntactically non-integrated. Finally, auch and anche as modal particles overlap only when embedded in declaratives and exclamatives, whereas German auch can appear in other sentence types (wh-interrogatives, polar interrogatives, wh-exclamatives and imperatives). These asymmetries will be crucial for the interpretation of our data (see Section 5 and Section 6 below).

3. Previous Studies on the Acquisition of Anche

While the acquisition and production of anche by IHSs have never been studied, there are some studies that deal with its acquisition by L2 speakers of Italian. In particular, Andorno (2000) is the first longitudinal study on L1 speakers of Chinese and Tigrinya, who were moving from a basic to a post-basic competence of Italian as L2 (Andorno 2000, p. 134). From a quantitative perspective, Andorno observes that anche is the first focalizer that appears in the speakers’ production and the most used (Andorno 2000, p. 139). Andorno observes that, especially at the initial stage of acquisition, several occurrences of anche do not seem to display either an additive or a scalar value16 (Andorno 2000, pp. 147–50) and lack a focalizing function. By contrast, they are used as generic sentence connectives and are placed between two utterances following the pattern in (24), which is not allowed in standard Italian:

With reference to Dimroth and Dittmar’s (1998) study on an Italian learner of German, who produces the same pattern in (24), Andorno (2000, pp. 194–95) argues that this use of anche cannot be interpreted as the result of CLI, as it does not belong to the L1 (German) system but rather it must be a typical pragmatic strategy independent from the speaker’s L1.

| 24. | sentence1 anche sentence2 (anche as a sentence connective) |

After this first stage, in which anche is used as a sentence connective, occurrences of anche as an additive particle emerge in Andorno’s data. As for the structural embedding of anche as an additive particle, Andorno investigates its position in relation to the topic-focus structure and shows that the L2 speakers of her corpus tend to produce in a first step elliptical structures of the type “anche-DA”, with the DA being the focus of the utterance. In this respect, Andorno takes this pattern to be the result of an analogy process following the pattern “negation particle (Ital. non/no)- focus”, which is acquired at a very early stage and, crucially, before focalizers.

When the speakers begin to produce utterances with finite verbs, they tend to put anche left adjacent to the DA as in the target, by placing the chunk “anche-x” in pre- or postverbal position, such as (25)–(26):

|

Finally, at a later stage, Andorno’s participants acquire the use of anche between the inflected and the non-inflected verb with anche taking scope over the predicate or the whole sentence. According to Andorno (2000, p. 195), this represents the most difficult structure to acquire because the intraverbal position is rarely used in Italian and thus rarely present in the input of the L2 speakers. To sum up, Andorno (2000) interprets her data on the production of anche as resulting from three main factors: (i) quantity of exposure to L2, (ii) universal pragmatic strategies of L2 speakers, which are independent of their L1 (initial anche as a sentence connective) and (iii) analogy processes within the L2 (pattern “anche-focus” and left adjacency in analogy to the negation pattern “negation particle-focus” in Italian). On the other hand, the rules governing the use of the adverb/particle corresponding to anche in their L1 do not seem to play a role.

Unlike Andorno (2000), two subsequent studies by Andorno and Turco (2015) and Caloi (2017) involve L2 speakers of Italian that have German as L117. Andorno and Turco focus on the two language pairs “Italian L1 + German L2” and vice versa, collecting spoken data via a retelling task based on a film clip (Dimroth 2006, 2012). The speakers are shown a film clip called “the finite story” produced with the purpose of eliciting various additive particles (see Dimroth et al. 2010)18. The authors focus both on the position and on the prosody of anche/auch, comparing the L2 speakers with a native control group. In the analysis of the data of the L2 speakers of Italian, they find that their participants mostly put anche in the position preceding the DA, which is target-like (see Section 2.1 above). Only three out of nine participants used the German postverbal position, and only one of them used it in most cases (three out of five) (Andorno and Turco 2015, p. 70). However, as far as prosody is concerned, the main Italian prosodic pattern, i.e., the falling contour on the last constituent of the DA in the scope of anche, is completely absent in the production by German learners. Rather, all types of sentences usually mirror the L1 contour: for example, the participants tend to produce the pattern “anche DA VP” (which is available both in German and in Italian) with the typical prosodic pattern of German, which is with a rising contour on the NP in the scope of anche and a rising contour or a high pitch accent on the VP. In a minority of cases, on the other hand, the sentence with anche shows a high plateau on anche, a falling accent on the DA and a flat pitch on the VO: this is an available pattern, although found only occasionally, in both Italian and German.

Andorno and Turco list various reasons to explain these data: first, they observe that there is a lack of transparency in the input because different orders with the same semantic content are available in some cases (but note that this concerns German L1 rather than Italian L1, cfr. Section 2). In addition, they invoke the partial overlap between anche and auch. Finally, according to the authors, anche and auch occur in marked structures, therefore, the realization of anche conflicts with other pragmatic principles (e.g., “topic first”). Andorno and Turco also claim that prosody is harder to acquire than syntax, and therefore, more CLI effects are expected.

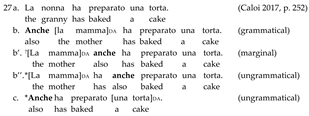

Caloi (2017) focuses on German learners of Italian only, using a multiple-choice task in which the participants, who all have a B1–B2 level, must choose the preferred word order. In her tasks, she considers three types of DA, distinguished through their syntactic role in the clause: subject, direct object, and VP. The speakers had to choose among three options: one was target-like, with anche immediately preceding its DA (27b); in the second, considered marginal by Caloi, anche immediately followed the DA (27b′). Finally, in the “ungrammatical” option, anche followed the finite verb when the DA was the subject (27b″), while it was in first sentence position when the DA was the object or the VP (27c):

|

The advantage of this study is that the results of different speakers are comparable, and there are enough data for the three DA types; in addition, it required less cognitive effort because the learners did not have to produce sentences on their own. On the other hand, such a task completely excludes information about the prosody with which these speakers would produce the sentences. Caloi’s results show that, in general, learners perform more target-like when the DA is the subject (66% of cases); when the DA is the object or the VP, the percentages drop (45% and 30%, respectively), but with a high degree of variability. These results are striking because it is in the subject condition that the ungrammatical option in Italian (the discontinuous construction) corresponds to the unmarked German word order so we would expect more CLI effects. On the other hand, in the other two cases, the order that is ungrammatical in Italian is possible but marked, in German. Hence, the L1 does not seem to be the main origin for the deviant answers, because otherwise, we would have a higher percentage of them in the subject condition, where German more consistently differs from Italian.

A second interesting result of Caloi’s study is that most of the participants seem to go for a fixed order, independently of the type and syntactic role of the DA. In this case, the position of anche varies: for some participants, it is preverbal, and for others, it is in the postverbal position. The author interprets these results as consistent with the activation either of the high FocusP in CP, or of the low FocusP in the periphery of vP (cf. Belletti 2004).

To sum up, in this section we have seen that although there are no studies dealing specifically with anche in HerIt, there are some studies on L2 Italian acquired by Germans that offer some important insights. If their results can be transferred to IHSs, we should be able to tentatively formulate the following predictions19:

- If (and only if) HerIt resembles L2 Italian in the use of anche, then its use should be comparable to that of HomIt:

- when the DA is the preverbal subject (cf. Andorno and Turco 2015; Caloi 2017);

- when anche is adjacent to the DA (Andorno 2000);

- If IHSs mirror L2 language learners in the production of anche, then their production differs from HomIt in the following respects:

- Anche should occur in a fixed position within the clause, unlike in HomIt (Caloi 2017);

- It should not show the same intonation as in HomIt, but the intonational pattern should have CLI from the dominant language, German (as shown for L2 speakers by Andorno and Turco 2015).

As far as (2b) is concerned, note that there are not many studies on HSs focusing on the production of intonation patterns. Polinsky (2018) only cites works on the prosody of focus (e.g., Van Rijswijk et al. (2017) on heritage Turkish in The Netherlands; Fenyvesi (2005) on heritage Hungarian in the US), which show that speakers tend to use the intonation patterns of their dominant language when producing foci. More in general, studies on the intonation of IHSs (Lloyd-Smith et al. 2020) have shown that the majority of them do not sound “native-like”, while a minority of them are perceived as native by homeland speakers: in Kupisch et al. (2014), less than 33% of the HSs tested were rated as having a native intonation.

4. Materials and Methods

In order to analyse the production of anche by IHSs, we carried out a study on the corpus HABLA (“Hamburg Adult Bilingual Language”, Kupisch 2011; Kupisch et al. 2012). The corpus HABLA was collected in the research project “Linguistic aspects of language attrition and second language acquisition in adult bilinguals (German-French and German-Italian)” (Kupisch et al. 2012). It is a collection of semi-structured interviews with HSs and L2 speakers with the language pairs German–Italian and German–French; some of the participants grew up in Germany, and the others in Italy or France, respectively. As for the German–Italian data, the corpus HABLA contains the following interviews (cf. Kupisch et al. 2012, p. 168):

- 12 interviews conducted in German and 12 interviews conducted in Italian with IHSs who grew up in Germany and have German as their dominant language;

- 8 interviews conducted in Italian and 8 interviews conducted in German with German HSs who grew up in Italy and have Italian as their dominant language;

- 15 interviews conducted in Italian with German L2 speakers of Italian;

- 19 interviews conducted in German with Italian L2 speakers of German.

The data from the L2 language learners were collected to compare HSs with L2 speakers. For our study, we focused on the interviews conducted in Italian with IHSs who grew up in Germany and whose dominant language is German. All speakers grew up in a bi-national family and were exposed to German and Italian from birth with their parents adopting the one-parent-one-language approach (Romaine 1995). At the time of the collection of the data, the participants were aged between 19 and 39 years. In particular, we chose to analyse 6 interviews/participants. We made the selection taking into account (i) the overall number of occurrences of anche and (ii) the number of non-matching occurrences in every interview. The interviews that had a low number of occurrences were not considered. Among those that had a considerable number of occurrences, we selected three in which the speakers tend to use anche according to the rules of HomIt and three that exhibit a substantial number of non-matching uses (see Section 5 below, Figure 1 and Table 3). Table 2 gives an overview of the codes, abbreviations and the number of anche occurrences of the 6 interviews:

Table 2.

HABLA speakers’ codes, abbreviations, and the total number of occurrences of anche.

We manually annotated all occurrences of anche (n = 200) found in the six interviews. They were then classified according to their function, and evaluated as compatible or not with the rules of HomIt (see Section 2 above)20. To individuate these rules, we relied not only on our judgements as native speakers—which coincided with those of Caloi (2017), but also on an investigation of the LIP corpus (which stands for Lessico di frequenza dell’italiano parlato, “Frequency lexicon of spoken Italian”), a collection of 496 conversations between native speakers of HomIt21. The LIP was collected in the early 1990s and contains conversations from Florence, Milan, Naples and Rome belonging to one of the following types: (A) spontaneous face-to-face conversations; (B) phone conversations; (C) interviews, debates and oral exams; (D) monologues (i.e., speeches); (E) TV and radio shows. For our analysis, we considered the first 100 occurrences of anche appearing in face-to-face conversations (type A), 25 from each city represented in the corpus22. The uses of anche in this corpus correspond exactly to the rules that we, as native speakers, had previously individuated through introspection.

5. Results

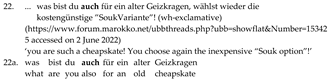

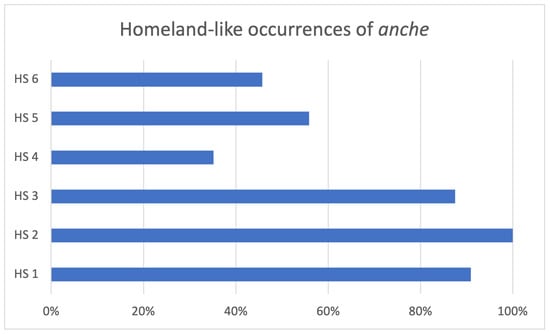

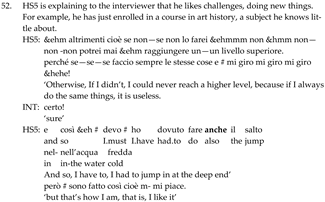

A first, strong result is a quantitative difference between the six analysed speakers: three of them (HS1, HS2 and HS3) performed at the ceiling, if compared to the HomIt grammar: their production was compatible with the HomIt rules in 91%, 100% and 88% of the cases, respectively (see below for a description of the non-matching uses)23. The other three interviewees (HS4, HS5 and HS6) followed the rules of HomIt in half of the occurrences, or even lower: only 35%, 56% and 46% of the realizations of anche matched the rules of HomIt. In absolute numbers, this corresponds to 19/54, 19/34 and 16/35 occurrences, respectively. Figure 1 illustrates the percentages.

Figure 1.

Occurrences of anche matching the HomIt grammar.

This sharp divide among the speakers witnesses the high individual variability, which could be due to various factors, such as the number and length of stays in the homeland, age of onset in German, the total amount of input in Italian, possibility or not of having education in Italian, attrition of the input coming from the parents, caregivers or other speakers that spent much time with the participant as a child; but there is also individual sensitivity to the rules present in the input24.

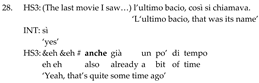

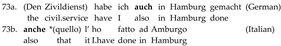

Let us turn to the qualitative results. The group of IHSs that perform very similarly to HomIt (HS1–3) produced just three non-matching anche: one modal anche that looks like a transfer from German auch (28), and two additive anche in postverbal position, a position that is admitted in German, but not in Italian (29):

In (28), anche is used as the German modal particle auch (das ist auch schon etwas her), while this use is not attested in HomIt. In (29), on the other hand, HS1 uses twice anche in the postverbal position, although the DA is preverbal (lì “there” and pioggia “rain”, respectively). This word order is ungrammatical in HomIt, while it would be perfectly fine in German (see Section 2.1 above, ex. (7)).

|

|

In the following sections, we do not consider HS1-3, because their production almost completely matches HomIt, but we focus on the other group (HS4–6), which is characterized by a high number of occurrences that would not be acceptable in HomIt. In our opinion, this clearly points to the fact that HS4–6 have a different grammar than that of HomIt, which obeys rules that are in part different (and that we will try to capture in the next sections). For expository reasons, we refer to the globality of these rules simply as “Heritage Italian” (HerIt), although we are well aware that there are individual differences, and that a high number of different “Heritage Italians” exist in the world.

The differences between HomIt and HerIt concern all functions of anche, although they are grounded on different bases: in the case of additive and connective anche, they are mainly syntactic, i.e., anche occupies a different position in HerIt, as compared to HomIt. In the case of modal anche, on the other hand, the main difference concerns its different degree of grammaticalization. In the production of IHSs, anche is used as a modal particle in cases in which German would use auch, but HomIt resorts to other means, i.e., there is a transfer of the functions of German auch to Italian anche. A crucial question in this respect is whether the three informants constitute a homogeneous group, i.e., whether their production is consistent across individual speakers, or whether every HS bases his production on different rules. Overall, at a descriptive statistical level, we did not find important differences between the three speakers in the number and type of occurrences that do not match HomIt.

Table 3 shows the overall occurrences of the different uses of anche and the amount of matching and non-matching cases, which we will analyse in the next sections.

Table 3.

The overall occurrence of the different uses of anche and the number of cases matching vs. non-matching the rules of HomIt (marginal cases are counted as ‘non-matching’ here).

Section 5 is organized as follows: Section 5.1 discusses the cases in which anche has the function of an additive particle; Section 5.2 deals with its role as connective; Section 5.3 focuses on the use of anche as a modal particle; Section 5.4 deals with some residual cases (indicated as “other cases” in Table 3).

5.1. Anche as an Additive Particle

The occurrences of anche as an additive particle are the most numerous in the corpus25: they amount to 72 out of 123. Overall, the occurrences of anche as an additive particle matching the rules of HomIt are 39 (54%), while 33 (46%) are deviant (including 9 marginal cases).

5.1.1. Types of Deviant Realizations

Recall that in HomIt anche as an additive particle is usually left adjacent to its DA, while right adjacency is marginally possible when the DA is preverbal. In the production of IHSs, when anche occurs in a position that is ungrammatical in HomIt (cf. Section 2.1), we mainly find three different patterns26:

- anche is right adjacent to the DA, which is usually preverbal (marginally possible in HomIt);

- anche occurs in a discontinuous construction, i.e., it immediately follows the inflected verb, while the DA is in the first position or in an internal position lower than anche (“DA—V anche” or “anche—XP—DA”);

- the DA is phonetically null; anche usually follows the inflected verb, as in type 2.

Pattern 1 concerns examples where anche follows, instead of preceding, the DA. In Caloi (2017), these cases are considered marginal in the production of German L2 learners of Italian. As for HomIt, we already pointed out in Section 2.1 (examples (3c)–(3d)) that anche following its DA seems to be possible only in the preverbal position but that its status is still underresearched. This is confirmed by the fact that in the LIP corpus there is just one instance of anche in this position, by a speaker from Rome:

|

In the HABLA corpus, there are nine instances; we illustrate them with two of them: in (31), the informant HS4 talks about her experience as a pupil and says that she did not like school because of both the teaching programme and the teachers. In (32), the informant talks about his summer holidays in Scandinavia.

| 31. | INT-GIU: | e | # ti | è piaciuta questa scuola? | |||

| ‘and did you like this school?’ | |||||||

| HS4: | così cosà | ||||||

| ‘so-and-so’ | |||||||

| HS4: | non ci andrei di nuovo | ||||||

| ‘I wouldn’t go there again’ | |||||||

| INT-GIU: | perché che cosa non ti è piaciuto? | ||||||

| ‘Why, what didn’t you like?’ | |||||||

| HS4: | sì # li # l’insegnamento | ||||||

| ‘well the teaching’ | |||||||

| HS4: | e | [l’insegnante]DA anche non mi | son piaciuti molto | ||||

| and the teachers | also | not me | are pleased much | ||||

| ‘and I didn’t like the teachers much either’27 | |||||||

|

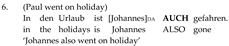

The second type of deviance, namely the discontinuous construction (Pattern 2), is much more frequent in our corpus (13 occurrences). Note that there are no examples of this construction in the LIP corpus: the adjacency principle between anche and the DA, with anche preceding the DA, is always respected, even when both occur in the postverbal position. This corresponds to our judgements as native speakers of Italian.

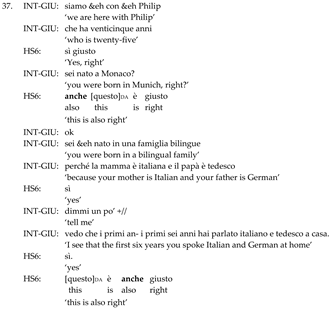

In the case of the IHSs, we have numerous cases illustrating the discontinuous construction. In example (37) the interviewer asks for some biographic data about the informant HS6. HS6 answers three times confirming the information read out loud by the interviewer. The second and third times, he confirms by saying: “This is also correct”, but first he uses the HomIt order, and then a deviant order:

In (37), HS6 is using the two word orders “anche DA V” (anche questo è giusto) and “DA V anche” (questo è anche giusto) apparently in free variation, while HomIt only allows the first one.

|

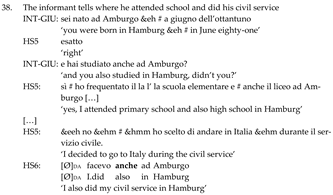

Finally, a special case of discontinuous construction concerns those cases in which the DA is a phonologically null topic (Pattern 3). An example is given in (38): here the object “civil service”, which occurs in the sentence before, is dropped, although it is the DA of anche:

The last line of example (38) contains an example of topic drop (see Helmer 2016), a common phenomenon in German, the dominant language of IHSs. In fact, this sentence (facevo anche ad Amburgo) would be fine in German (cf. (38a)). In HomIt, on the other hand, we would need to realize the topic (which is also the DA) in a left-dislocation structure, whereby the particle is left adjacent to it (38b):

|

|

Note that (38) also resembles German in the fact that the topic is not resumed by a clitic pronoun, while HomIt always requires clitic doubling when a direct object is topicalized (38b). We come back to this in the analysis (Section 6.3).

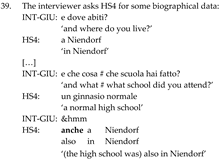

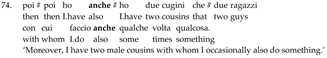

Another similar example is found in (39), where the null subject is the DA. In this case, again we find what looks like an instance of topic drop, but in an elliptical structure in which the verb is not realized either. This example would also be fine if translated into German, while it is ungrammatical in HomIt:28

|

The examples with topic drop are striking because they really seem to be based on a German pattern. However, it must be noted that there are only four unambiguous cases of this type, and they are produced only by two of the three informants. Therefore, we cannot exclude that they are just production mistakes related to the spontaneous oral form of the interviews, rather than a systematic pattern.

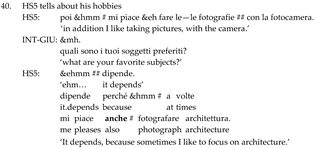

Finally, in addition to these four patterns, a last type of deviance that deserves discussion is when the IHS uses anche in a context that would be impossible in HomIt. We have identified four instances of this type; one of them is given in (40):

|

Here, anche is not used as a typical additive particle, because the informant does not add “architecture” to a set of alternatives present or inferrable from the cotext but rather he is mentioning “architecture” as an example, to underline that architecture is one of the various topics he likes to photograph29.

5.1.2. Total Number of Occurrences

We have seen that when anche is used as an additive particle, there are four main patterns, whereby three do not completely match the rules of HomIt: anche is right adjacent to its DA (marginal in HomIt), instead of being left adjacent to it; anche follows both the DA and the verb (discontinuous construction); the DA is phonologically null in what seems to be a topic drop configuration. These patterns do not show the same frequency (Table 4): the HomIt pattern is dominant, while Pattern 3 is the least attested. Note that the 44 occurrences of Pattern 1 include 39 occurrences that match the rules of HomIt and 5 occurrences that do not match them, for independent reasons.

Table 4.

The position of anche with respect to its DA, all occurrences.

5.1.3. Syntactic Properties of the Production of Anche as an Additive Particle

A first question that we might ask is whether the non-matching orders are linked to some specific syntactic role carried by the DA. This is an important question since Andorno and Turco (2015) and Caloi (2017) reported that their participants seem to have no problems when the DA is the subject of the clause. We have, therefore, classified all the instances in which anche is used as an additive particle. Table 5 shows the total numbers.

Table 5.

The realizations of the order “anche DA” according to the syntactic role of the DA.

Table 5 shows that the performance of the IHSs is not closer to HomIt when the DA carries the syntactic role of the subject. On the contrary, this is the context in which they diverge most from speakers in Italy. Therefore, we cannot extend the observations made by Andorno and Turco (2015) and Caloi (2017) on L2 learners of Italian to IHSs.

Now, these data lead us to another question: why does the IHSs’ grammar differ from HomIt, especially when the DA is the subject? We suggest that this asymmetry is due to the position of anche in the clause: since Italian is an SVO language, the unmarked position of the subject is preverbal (except for subjects of unaccusative verbs, Belletti 2004), while objects or PPs, especially when they are argumental, are postverbal. As seen in Table 4, IHSs have two orders available, one in which anche is left adjacent to the DA, and one in which it occurs in the postverbal position; when the DA is the object or VP, these two positions frequently overlap, while they remain distinct with preverbal subjects.

To properly understand the data, we, therefore, need to know the exact position of both the DA and anche with respect to the verb, because, as suggested in the literature on L2 learners, we might want to know whether IHSs also tend to assign a fixed position in the clause to anche, independently of the syntactic role and position of its DA (cfr. Caloi 2017).

Table 6 shows that in almost two-thirds of the occurrences, anche is postverbal (65.3%). However, the cases in which anche directly follows the verb are less numerous, namely 34 out of 72 (which corresponds to 47.2% of the total occurrences). Note that 15 of these 34 instances match HomIt, because the DA follows anche.

Table 6.

Position of additive anche with respect to the verb and to the DA, all occurrences.

Therefore, if we consider together Table 4 and Table 5, it is clear that the grammar of HerIt does neither match that of HomIt nor that of German (e.g., because it allows the order [DA anche]).

Now, a last question to ask is what the distribution of the different positions of anche in HerIt is. We have looked at the informational status of the preverbal DA when anche is left adjacent vs. when it is postverbal, and the corpus data show that HerIt exploits the two positions exactly as German does: anche is left adjacent to the DA when the latter is focalized, while it is in the postverbal position when the DA is not. We illustrate this with examples (41a) and (41b). In (41a), the interviewer asks SH4 whether she spent the whole summer in Milan, where some of her Italian relatives live.

In this example, which corresponds both to the grammar of HomIt and of German, HS4 realizes the structure ‘anche + DA’ in the preverbal position. From the information structural point of view, the DA a Natale is focalized as it encodes the most relevant piece of information within the utterance in the given context. With anche, HS4 adds a Natale to the list of alternative times of the year (summer, Christmas) when she spends time in Milan. Example (41b) (which was already discussed above as part of ex. (37)) shows that when anche is in the postverbal position within a discontinuous construction its DA encodes given information. In this case, the structure is not grammatical in HomIt but it mirrors the syntax of German.

The DA questo refers to what the interviewer has already said i.e., the fact as a child HS6 spoke Italian and German at home.

|

|

5.1.4. Prosodic Properties of the Deviant Realizations

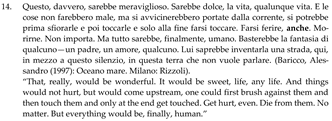

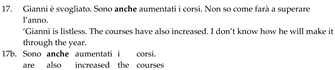

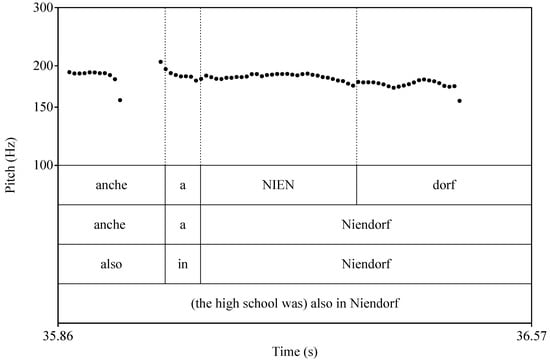

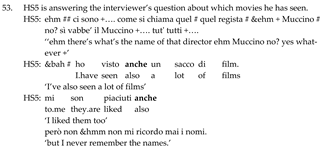

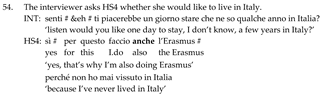

Let us now look at the prosody of our data. As reported above (Section 3), Andorno and Turco (2015) investigated German learners of Italian and found that their anche utterances tend to mirror the prosody of their L1 (i.e., German). Opposing that, the prosodic patterns of our IHSs do not seem to mirror the German ones. In particular, the non-matching anche utterances of the type “DA V anche” and “DA anche V” do not show the prosodic pattern of the German corresponding structure “DA V auch”/”V DA auch”, which are characterized by the presence of the focus accent on auch (see Section 2.1 above, ex. (6) and ex. (7), and Moroni and Bidese 2021a; Reimer and Dimroth 2021, a.o.). By contrast, anche in the utterances produced by the IHSs of our corpus never bears the focus accent. This can be seen in Figure 2 and Figure 3, which show the pitch contours of two deviant utterances by the speaker HS4 discussed above (ex. 31 and 39). The figures were created using Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2021).

Figure 2.

Pitch contour of the utterance [l’insegnante]DA anche non mi son piaciuti molto by speaker HS4.

Figure 3.

Pitch contour of [Ø]DA anche a Niendorf by speaker HS4.

The sentence in Figure 2 is realized with the major focal movement on the verb (piaciuti) and a secondary pitch movement on the DA (insegnante). By contrast, the particle anche is part of a flat segment. If the speaker were subject to transfer from German, we would expect a pitch track with the major focal movement on anche (see Andorno and Turco 2015, p. 67)

The pitch contour of the utterance in Figure 3 does not mirror the prosodic pattern of German either. In this case, the utterance is realized with an overall rather high-flat contour. The focus movement is realized on Niendorf, whereas if prosody were affected by CLI, we would expect the major focal movement to be on anche and the rest of the utterance to be unaccented/flat.

5.1.5. Interim Summary

HerIt, when anche is used as an additive particle, resorts to various orders, including the discontinuous pattern. This pattern order is frequent, irrespectively of the type and position of the DA. This contrasts with HomIt, where anche always precedes its DA, independently from its position in the clause or its informational status. Since Italian subjects appear in preverbal position in unmarked clauses (except when the predicate is an unaccusative verb), when they are the DA the divergence between HomIt (where anche precedes the DA in all cases) and HerIt (where anche tends to occupy the postverbal position) is particularly evident.

The postverbal position of anche superficially resembles what we find with German auch, which is also used in two different positions, depending on the pragmatic function of the DA. We might, therefore, think of a transfer phenomenon from the dominant language of the IHSs, German, to their weaker language, HerIt. However, in the use of the additive particle, HerIt does not completely overlap with German: although there is a syntactic resemblance, prosodically HerIt anche is clearly different than German auch: while the latter bears the major focal movement, this is not the case in HerIt, where anche is realized with a flat contour.

5.2. Anche as a Sentence Connective

The occurrences of anche as a sentence connective amount to 23 out of 123. Overall, those following the rules of HomIt are 13 (57%), while 10 (43%) are deviant.

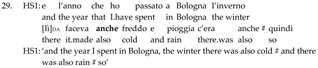

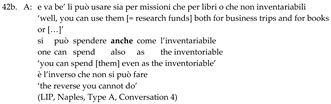

In the LIP corpus, our control corpus for HomIt, there are just 7 occurrences of anche as a sentence connective. In 6 out of 7 cases, anche appears immediately after the verb or the verb group (ex. 42a and ex. 42b), in one case it is sentence-initial, left adjacent to the causal conjunction perché (ex. 43):

|

|

|

Note that the position on the left of perché (“because”) in (43) could be due to the fact that here anche retains a stronger additive value (there are various reasons, one of which is the mentioned one).

Parenthetical uses of anche as illustrated above in Section 2.2 are not attested. This might be due to the fact that these uses are more typical of high, formal registers.

By analysing the meaning of the sentence in which anche appears, together with the context, we classified 10 occurrences in the HABLA corpus as deviant uses of anche as a sentence connective. Most of them (8) appear in the postverbal position. In one case, anche is left adjacent to the finite verb and in another case, it is sentence-final.

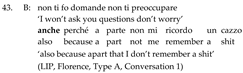

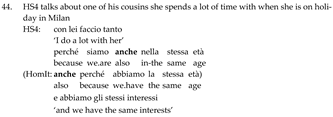

Let us first have a look at the deviant occurrences of anche as a sentence connective in the postverbal position. In this case, in HomIt, anche would be (i) sentence-initial preceding a subordinate conjunction (ex. 44), (ii) right adjacent to the finite verb (ex. 45–46) or (iii) inappropriate in the given context (ex. 47):

|

|

|

|

Example (44) concerns the position of anche when it takes scope over a subordinate clause. In this case, it must precede the subordinating conjunction (perché in (44)) according to the rules of HomIt (see above ex. 43 from the LIP corpus). Instead of placing anche in the sentence-initial position, the participant places it in the postverbal position. Instances such as this cannot be considered as a result of CLI, because German auch as sentence connective follows the same pattern as HomIt (anche perché, auch weil). Rather, this deviant use of anche could be due to a general tendency to place auch/anche in the postverbal position, this position being reanalyzed as the default one.

As for cases such as (45) and (46), anche is embedded in a main clause and should appear right adjacent to the finite verb according to the homeland variety. Instead, it is placed further to the right. Finally, in (47) there are two occurrences of anche. The first anche (in the utterance perché lei anche è una ragazza) is an additive particle in a non-canonical position (DA+anche, whereas anche+DA is expected) and it is analogous to anche in example (31) discussed above in Section 5.1.1. The second occurrence of anche (in ha anche la mia età) is not expected in Italian but rather a structure such as ha la mia stessa età (“she is my age”) or anche lei ha la mia età (“she is also my age”, lit. “also she has my age”) would be appropriate. Overall, these non-matching occurrences of anche seem to be due to the general dominance of the postverbal position of the particle in both languages.

In one case, anche occupies the left periphery of the sentence together with the discourse marker però (cf. Sansò 2020) and is left adjacent to the finite verb:

Differently from the previous occurrences, this one can be considered as the result of CLI, as it follows the German pattern illustrated above in Section 2.2 with the example (10), where auch is a sentence connective in the first position left adjacent to the finite verb, which is ungrammatical in HomIt.

|

Finally, anche as a sentence connective appears in one case in sentence-final position:

According to the HomIt grammar (see also ex. (43) from the LIP corpus), anche must occupy the first position left of the embedded clause, adjacent to the subordinating conjunction come, as in (50):

|

| 50. | c’è tanta roba anche tutti gli antipasti # &eh. anche come sa (= il sapore) la carne 30 |

| ‘There’s a lot of stuff, also all the starters, and [I also like] how the meat tastes’ |

Summing up, the deviant occurrences of anche as a sentence connective are quite heterogeneous. Only the (seldom) structure “sentence-initial anche—finite verb” can be interpreted as a CLI phenomenon based on the German structure (see example (10) Auch arbeitete sie als Foto-Modell in Section 2.2). In most cases, the participants fail at (i) placing anche in the first position when it takes scope over a subordinate clause (anche perché, anche come) or (ii) placing it right adjacent to the finite verb with analytical verb forms. In both cases, speakers place anche further to the right. In this respect, they seem to fall back to the general rule “put anche in post-verbal position” as the most frequent position.

5.3. Anche as a Modal Particle

Anche as a modal particle is attested five times in our data. In two cases, its use corresponds to the one of HomIt. In the other three cases, it is used in a deviant way. In addition, more occurrences could be interpreted as modal, but they show ambiguity and are difficult to classify. We will discuss this in Section 5.4 below.

Let us now first look at the two non-ambiguous cases that match HomIt. The first one stems from the interview with HS4:

|

In this example, the use of anche matches the rules of HomIt because it appears together with a modal verb construction (posso…andarmene), it is right adjacent to its finite part and it has scope over the whole proposition signalling that it is coherent with the previous context and thus expectable, i.e., the proposition “a me piace la sicurezza che c’è ad Amburgo”: the fact that HS4 can walk around the city alone is coherent with the fact that Hamburg is a safe city.

The second case of a matching realization of anche as a modal particle is (52):

|

As in (51), anche as a modal particle appears here in the postverbal position and in combination with a modal verb (dovere). It operates at the modal level in that it indicates that HS5′s going into new situations without any preparation is coherent with the fact (expressed in the preceding context) that he likes challenges.

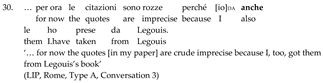

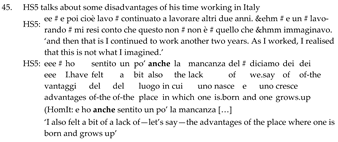

Let us now move to the deviant uses of anche as a modal particle in HerIt (3 occurrences). In these cases, anche appears right adjacent to the finite verb or the verb group and seems to mirror the German modal particle auch. The following sequence by speaker HS5 contains two examples in point:

Both anche occurrences are used in this case to mark the proposition as expected and coherent with the context: the fact that HS5 cannot remember the names of the films he has seen is coherent with the fact that he saw a lot of them (thus it is not easy to remember all names). Similarly, the fact that the speaker liked the films he saw is marked as coherent with the previous context. This modal use of anche is absent in HomIt because anche—unlike German auch—cannot occur with modal value unless there is another modal element like a modal verb (see above ex. 51 posso anche andarmene da sola tranquillamente) or a marked verb mode such as imperfetto or condizionale (Cognola et al. 2022).

|

In sum, the speakers of our corpus seem to use anche as a modal particle calquing the corresponding German structure without taking into account that the Italian modal particle anche is subject to more restrictions in that it needs a “modal environment” (i.e., the presence of a modal verb, or specific verb modes). This means that the use of anche as a modal particle seems to be affected by CLI.

5.4. Other Cases

In our corpus, there were 23 occurrences that are difficult to categorize. They are of two types: (i) in 17 cases, anche is ambiguous, that is, it could be interpreted as belonging to different categories (additive particle, sentence connective or modal particle); (ii) 6 occurrences cannot be drawn back to any of the functions of auch/anche. In this case, anche has an assertive function. We will delve into the two types separately.

5.4.1. Ambiguous Occurrences

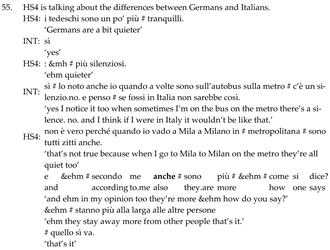

In some cases, it is difficult to disambiguate between the functions of anche. This is typical of multifunctional particles in standard (non-heritage) varieties (cf. Moroni and Bidese 2021a; Reimer and Dimroth 2021, p. 6). In the following sequence, anche could be interpreted either as an additive particle or as a modal particle:

Anche could be interpreted as an additive particle with scope over per questo in first position, meaning that there are many reasons why HS4 would like to do Erasmus in Italy, one of which is that she would like to live in Italy. According to this interpretation, the use of anche would be the result of CLI from the German structure ‘DA+accented auch’ (see Section 2.1 above, example (7)). However, the CLI would be only at the syntactic level because anche is not accented. This would be in line with what we already observed for a subtype of deviant uses of anche as an additive particle (see Section 5.1.1 above, example (37)).

|

On the other hand, anche could be interpreted as a modal particle marking the proposition “per questo faccio l’Erasmus” as expected and coherent with the contextual information about the speaker’s wish to live in Italy.

Disambiguation can also be difficult when anche is followed by a pause or a reformulation. In these cases, anche could be interpreted as a sentence connective. However, such a context prevents us from unambiguously categorizing such occurrences. An example in point is (55):

In (55), anche appears in the segment secondo me anche and precedes the finite verb. The pause following anche is probably due to a self-initiation of repair by the speaker, who continues to look for the right formulation after producing anche realizing further pauses and hesitation signals (ehm) and finally asks the interviewer’s help. As this kind of occurrence displays interruptions, we cannot detect which kind of anche the speaker intended to realize.

|

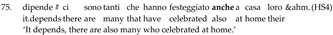

Another interesting sequence in this respect is (56), in which anche occurs three times:

The first and the third occurrence are difficult to classify because they are followed by a pause, which could be due to a self-repair by the speaker that decides to start the utterance again. As for the second anche, it represents in our view a typical non-matching realization of anche as a modal particle, which is supposed to mark the proposition as expected. However, it could also be interpreted as a sentence connective meaning “furthermore” or as an assertive anche, a particular type that is not part of the Italian grammar and that has not been described for German, as we will illustrate in the following subsection.

|

5.4.2. “Assertive” Anche

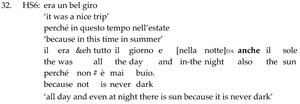

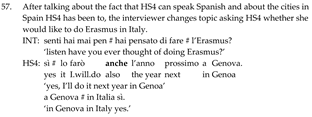

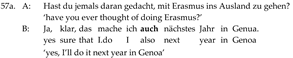

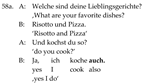

In our data, anche occurs six times in the postverbal position with an assertive value in that it is embedded in utterances that speakers realize to answer positively to polar questions. Let us have a look at an example of an “assertive” anche from the interview with HS4:

In example (57), it can be observed that anche does not display any additive value, as it does not operate on a phrasal constituent that should be added to a list: there is no reference to any other thing the speaker is going to do the following year in Genova, or to the following year in general; furthermore, the speaker is not using anche to connect the utterance with a previous one. Finally, the interpretation of anche as a modal particle (meaning “as can be expected”) is also inappropriate in the given context. Rather, the speaker produces the utterance with anche to respond positively to the question of the interviewer whether he has ever thought about doing Erasmus.

|

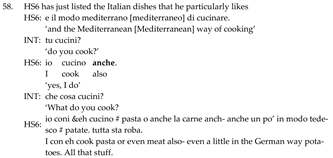

A similar example is (58) by the speaker HS6:

In (58), the speaker has just listed the Italian dishes he likes most. Then the interviewer moves on to a new (sub-)topic asking him whether he cooks. With the answer “Io cucino anche” HS6 intends to answer positively to the question. Neither the interpretation of anche as a sentence connective nor the one as a modal particle seem plausible in the given context.

|

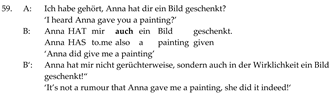

This use of anche in responsive utterances with assertive value is not present in our control data for HomIt (LIP corpus), nor does it sound grammatical to our native intuitions. Thus, assertive anche must be considered a deviant realization. As for German, research does not usually refer to auch with assertive value. To the best of our knowledge, only Dimroth (2004, pp. 148–50) puts forward the hypothesis that auch can take a focalized finite verb form in its scope thus acquiring an assertive value. She gives the following example31 (taken from Löbner 1990, p. 86):

According to Dimroth (2004, p. 148), the utterance by speaker B, in which a finite verb with a contrastive focus accent (hat) occurs together with auch, must be interpreted as in B′, i.e., when auch occurs in a sentence with a focalized finite verb, it operates on the degree of probability of the proposition signalling that the proposition is true, hence the assertive effect of such occurrences of auch.

|

As Dimroth (2004, pp. 148–50) supports her thesis based on a single example, we constructed a German version of the examples above (57)–(58) and asked three speakers with German as their L1 if they consider the dialogues felicitous:

Two out of three informants rated the dialogues as flawless. The third informant rated the use of the pronoun das in (57a) as incorrect, saying that das refers to the whole sentence of A and proposed to substitute it with the DP das Erasmusprogramm. In this case, the informant seems to rate the use of auch as incorrect and to only accept the interpretation of auch as an accented additive particle taking scope on das Erasmusprogramm. In the second step, the informants were asked whether the use of anche in both dialogues was fine and they all answered positively but one of them added that auch is not necessary. These judgements are in line with Dimroth’s (2004, pp. 148–50) hypothesis about an assertive auch and hint at the fact that uses such as (57) and (58) could be part of the grammar of German. Thus, “assertive anche” in HerIt could be due to CLI from German.

|

|

6. Discussion

The data discussed in the previous sections show that the grammar of HerIt neither coincides with HomIt nor with German. In fact, while some occurrences match both the rules of HomIt and German, others are consistent only with one of the two languages; a third type of occurrence would be ungrammatical in both of them, and it is thus unique to HerIt (e.g., the postverbal anche without stress). In this section, we aim at individuating the rules that govern the use of anche in HerIt and analyse them contrastively with HomIt and with German. In order to tackle this issue in an ordered and clear way, we discuss the different uses of anche one by one. Thereby, we first focus on its use as a connective and modal particle, whose analysis is more straightforward, and then we turn to the additive use, which is the most intricate.

6.1. The Use of Anche as a Sentence Connective

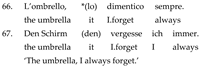

As shown in Section 5.2, in most cases anche occurs in the postverbal position (21 out of 23 cases); in 13 cases this matches the rules of HomIt, while in 8 cases the latter would require a different position in the clause. In particular, when anche connects a secondary clause to a preceding main clause, it always occurs in the leftmost position (e.g., anche perché… “also because…”) in HomIt, while IHSs tend to put it in a clause-internal, postverbal position (perché V anche “because V also”), cf. example (44). In addition, there are other cases where it is HomIt that requires anche in the position directly following the verb, but IHSs produce it in a position more on the right (after an adverbial expression in (45) and after the past participle in (46)). Note that (44) and (46) would be deviant in German as well because German also requires auch to precede subordinators such as weil (“because”) and the past participle (German being an SOV language). Therefore, these cases seem to point to the fact that IHSs have generalised the postverbal part of the clause as the target site for anche (with just a few exceptions); compared to HomIt, HerIt is more rigid, because it is insensitive to the context; on the other hand, it allows anche to be in a lower position, i.e., the sequence “finite V—anche” can be interrupted by other material, for example, adverbs or the past participle.

In the remaining two occurrences, anche is once in the left periphery (48) and once in the rightmost position of the clause (49). The first case is completely unattested in HomIt, and it could be due to CLI; the second is again a case of postverbal position, but in this case, anche follows the direct object as well. However, we cannot exclude that it might be added as an afterthought here.

In sum, the rules of HerIt concerning anche as sentence connective are characterized by a tendential insensitivity to pragmatics, which leads to a generalisation of the postverbal portion of the clause as the site of occurrence of anche. However, there is variability as far as syntax is concerned, because HerIt follows in part the rules of HomIt.

6.2. The Use of Anche as a Modal Particle

The unambiguous instances of anche used as a modal particle are not frequent in the corpus. For these cases, we should start from the observation that there are no clear syntactic differences between HomIt and German, as far as the modal uses of anche/auch are concerned: in both languages, it occurs in the TP (Coniglio 2008; Cardinaletti 2011). Since the structures overlap, it is not surprising that in HerIt as well all instances of the modal anche immediately follow the finite verb. The difference between HerIt and HomIt lies in the distribution of modal anche: IHSs extend its use to the contexts and sentence types in which anche would be ungrammatical in HomIt. The process that led to this result might be interpreted as a CLI effect from German, because CLI, and contact-induced change in general, typically affects properties that are already present in the target variety; therefore, the overextension of modal anche could be an acceleration effect of a tendency already present in HomIt (for similar effects in contact and heritage languages, cf. Benincà 1985–1986; Kupisch and Polinsky 2022).

6.3. The Use of Anche as an Additive Particle

We have seen that IHSs follow mainly four patterns when they use anche as an additive particle (see above, Section 5.1). In addition, we have already discussed that the analysis of anche as an additive particle must consider both syntax and intonation.

As far as syntax is concerned, we take as a point of departure the analysis of Cognola et al. (2022) for Italian, according to which anche is merged in a functional projection (“FP”) in the vP-space, within the low periphery (Belletti 2004). In this analysis, anche is always merged immediately below the low FocusP.

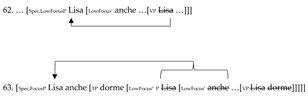

In the “HomIt Pattern”, namely, when the outcome is the order [anche DA] in preverbal position, anche attracts its DA to its Specifier; after that, anche itself moves to the next head, namely Foc° (60). Subsequently, the whole complex [anche DA] is moved (as remnant movement) to the high FocusP in the left periphery, if the informational structure requires so (61):

This analysis explains why the DA is focalized, and why anche and the DA must be adjacent in this construction.

The marginal pattern “DA anche” (Pattern 1), is acceptable in some central and southern areas32. Since we have no data about the regional Italian varieties from which the participants got their input, we cannot exclude that this rule came into HerIt from regional HomIt33. In addition, the use of this pattern could also be a matter of register and diamesic variation as it is probably more common in spoken/informal Italian34. The analysis that we can assign to this pattern is similar to Pattern 1, with the difference that the DA must precede anche at the end of the derivation. In principle, there are two possible ways to analyse this structure. The first is that, initially, we have the same configuration as in [anche DA] above (60), with anche moving from FP to LowFocus. Subsequently, anche attracts the DA Mario to Spec,LowFocusP and then both move. The second analysis is that anche is directly merged in LowFocus, and attracts Mario to its Spec. This would eliminate an intermediate step, involving an FP as the merging site of anche, and as the host of the first movement of the DA. In both cases, then, LowFocusP would move to the left periphery, if needed. At the moment, there is no evidence about which of the two analyses should be correct; for a principle of economy, we prefer the second analysis, because it dispenses us with a double movement that is not easy to justify semantically, which would make the structure unnecessarily more complicated35.

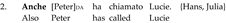

Let us move to the discontinuous construction (patterns 2 and 3), in which anche appears clause-internally, while the DA is in a preverbal position. First, note that in German the DA is interpreted as a topic, while focalized DAs require adjacency with anche/auch. As shown in Cognola et al. (2022), this configuration is ruled out in Italian because in this language topics are merged in CP directly (Cinque 1990). Therefore, anche cannot scope over the DA. The only way to rescue the discontinuous construction is through the insertion of a pronominal copy in the scope of anche:

|

In German, on the other hand, non-resumed Topics are moved to the left periphery. Therefore, when the DA moves to the left periphery it leaves a trace in the scope of auch. The link between auch and the spelt-out copy of the DA is marked by intonation:

|

Now, if we turn to HerIt, a first observation is that the discontinuous construction is documented only when the DA is a topic, as in German—but with important differences at the prosodic level (see below). In principle, two hypotheses are available to explain this distribution: either topics are moved in HerIt, as they are in German; or they are merged in the left periphery, as in Italian, but there is some link with a position in the scope of anche. Under the first hypothesis, syntax and intonation would go separate ways: speakers would have adopted a German-like syntax, while they would have kept the Italian intonation rules. The second hypothesis assumes that HerIt differs from German at both levels, syntax and prosody, and that the syntactic similarities are only superficial.

Due to the nature of the HABLA corpus, which collects semi-spontaneous speech and not grammaticality judgements, we have no decisive evidence for the movement vs base-generation nature of left-dislocated topics. What we can do, however, is discuss some pieces of evidence that in our opinion point towards the first hypothesis, namely that the HerIt syntax depends on transfer effects from German, and that topics move in HerIt, as they do in German. The reason why we think the first hypothesis is stronger has to do with some empirical and theoretical observations, which are:

- Overall properties of topicalization in HerIt;

- Properties of the use of anche;

- Evidence coming from other moved elements;

- Theory-internal reasons.

In the remaining part of this subsection, we discuss these observations separately, one after the other.

1. HomIt and German differ in topicalization, because the former has clitic resumption, while in German we find two types of topicalization: simple preposing without resumption and left dislocation with resumption through a weak pronominal (cfr. Cinque 1990; Rizzi 1997; Benincà and Poletto 2004 for Italian; Grewendorf 2008; Ott 2014; Casalicchio and Cognola (2023, forthcoming) for German). Crucially, for German the proposed analyses all contain a movement operation, while for Italian Cinque (1990) proposed a base-generation approach, which is still considered valid by many scholars:

|

In our corpus, there are eight unambiguous occurrences of left dislocation, all involving a direct object. In five of them there is a resumptive pronoun, so that the superficial outcome matches both HomIt and German (68). In the remaining three cases, clitic resumption is missing (69): this configuration resembles what we find in German, while it would be ungrammatical in HomIt:

|

|

The key aspect of these data is that while the presence of clitic resumption is per se compatible both with a movement and with a base-generation analysis, the examples without resumption are generally interpreted as involving movement.

2. As far as the syntax of anche is concerned, consider first that the discontinuous construction is compatible with clitic left dislocation (70):

|

Note that such a sentence would be perfectly fine in German, while in Italian we would need a full proform in the TP (in this case a demonstrative quello (“that”)):

Since anche needs at least a copy of its DA in its scope (on its right), we might presume that (70) is possible because quello has moved from the low left periphery to the high TopP (see below, point 4).

|

|

In addition, topic drop (Pattern 4) is another construction that points towards a movement analysis: as discussed in Section 5.1.1, the informants’ production contains instances of this phenomenon that is found in German, but not in HomIt. Example (73) is an example from HomIt we already discussed above in Section 5.1.1:

This example is noteworthy because the null topic is the silent DA of anche.

|

Examples (73a)–(73b) are derived from (73) and show that the topic drop structure is allowed in German but not in HomIt, i.e., in HomIt the DA is always spelt out (except for elliptical constructions):

|

Therefore, the syntax of topics in HomIt shows some properties that clearly match German (topic drop, left dislocations without clitic resumption and resumed left dislocations with anche), while there is no construction that matches only HomIt, but not German.

3. Further evidence for a movement analysis of the DA comes from cases in which the DA is undoubtedly moved to the left periphery, namely when it is an operator of a relative clause: