Audiovisual Translation, Multilingual Desire, and the Construction of the Intersectional Gay Male Body

Abstract

1. Introduction: Contemporary Complex Telecinematic Fiction

2. Method Design

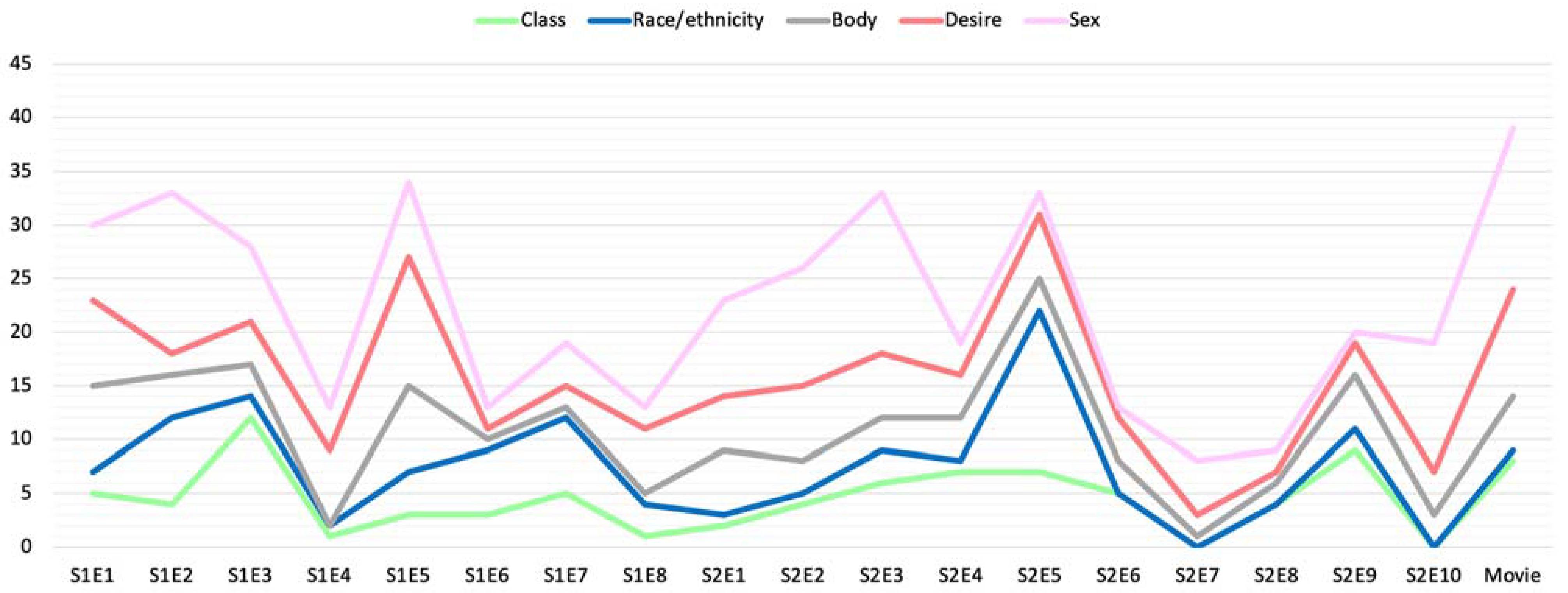

3. Looking as a Narrative: Overall Findings

- The stance of the white gay character determines the type of body that can be eroticized.

- Desire is marked by ethnic and class differences that give meaning to embodied differences.

4. Multilingualism and Semiotic Interaction in Looking

5. Cholo Boyfriend/Novio Panchito: Embodied Language Difference

5.1. Metaphorical Switching

| (1) | a. | Richie: Hola, prima. (L3) | Qué onda, prima. (L2a) | Hola, prima. (L2b) |

| b. | Ceci: Espérame. Is this the pinche puto desgraciado (L3) Patrick that broke your heart? | Espera, espera. ¿Es el pinche puto desgraciado que te rompió el corazón? (L2a) | Un momento. ¿Este es el Patrick del que me hablaste, que te destrozó el corazón? (L2b) | |

| c. | Ceci: ¿Todavía andas con ese güey? (L3) | ¿Todavía andas con ese güey? (L2a) | ¿Todavía sigues con él? (L2b) | |

| d. | Richie: Calmadita. No ando con él. (L3) | Calmadita. No ando con él. (L2a) | Cálmate. No sigo con él. (L2b) | |

| e. | Ceci: ¿Quieren unas chelas? (L3) | ¿Quieren unas chelas? | ¿Queréis una cerveza? (L2b) | |

| f. | Ceci: Hey, Manny. Bring these dudes some chelas (L3) from the fridge. | Oye, Manny. Tráeles a estos batos unas chelas de la refri. (L2a) | Eh, Manny. Trae dos cervezas de la nevera. (L2b) |

5.2. Intimacy and Affect

| (2) | Richie: | Ay, chiquito. (L3) You’re a funny guy. |

| Ay, chiquito. Qué simpático. (L2a) | ||

| Ay, chiquitín. Qué gracioso. (L2b) |

| (3) | Richie: Ay, Pato (L3). You worry about so much. | Ay, Pato, te preocupas por muchas cosas. | Ay, Pat, te preocupas demasiado. ¿Tú no? |

| Patrick: You do not? | ¿Tú no? | ||

| Richie: I worry about... getting a | Me preocupo porque me | Me preocupa cobrar la | |

| paycheck, paying my rent… | paguen, pagar mi renta. | nómina, pagar la casa. | |

| Patrick: Not the big stuff? | ¿Por lo importante no? | ¿Nada de lo gordo? | |

| Richie: That is what I got my señora (L3) for. | Para eso tengo a mi señora. (L2a) | Para eso tengo a mi señora. (L2b) |

| (4) | Richie: I just wanted to, um... You see me wear my thing? | Y quería que... ¿has visto lo que uso en mi cuello? | Quería que... ¿has visto lo que llevo? |

| Patrick: Your necklace? | Tu collar. | El collar. | |

| Richie: No, not my necklace. My | No, no mi collar. Mi | No, el collar no, el | |

| escapulario. (L3) | escapulario. (L2a) | escapulario. (L2b) |

5.3. Crossing

| (5) | Agustín: | Can you believe our little brother is getting himself a cholo (L3) boyfriend? |

| ¿Puedes creer que nuestro hermanito se consiguió un novio cholo? (L2a) | ||

| ¿Te lo puedes creer? Aquí el colega quiere echarse un novio Panchito. (L2b) |

| (6) | Richie: Yo, man. What’s your fucking problem with me, dude? Why do not you just say it to my face? | Oye, imbécil, ¿cuál es tu puto problema conmigo? Dímelo en la cara. | Oye, tío, ¿qué problemas tienes conmigo? Dímelo a la cara, vamos. |

| Agustín: Dude... no, I am sorry. I did not mean any disrespect. En verdad, hermano, fue sin querer. (L3) | Oye, yo no, no quería faltarte el respeto. En verdad, hermano, fue sin querer. | Oye, tío, no, no quería faltarte el respeto. De verdad, hermano, fue sin querer. | |

| Richie: Now I am your fucking hermano. (L3) Man, fuck you. | Ahora soy tu puto hermano. Vete a la mierda. (L2a) | Ahora soy tu puto hermano. ¡Que te follen! (L2b) |

6. Final Remarks

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ávila-Cabrera, José Javier. 2015. An Account of the Subtitling of Offensive and Taboo Language in Tarantino’s Screenplays. Sendebar 26: 37–56. [Google Scholar]

- Backus, Ad, and Margreet Dorleijn. 2009. Loan Translation versus Code-switching. In The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Code-Switching. Edited by Barbara Bullock and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 75–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, Benjamin. 2007. Language Alternation as a Resource for Identity Negotiations among Dominican American Bilinguals. In Style and Social Identities. Alternative Approaches to Linguistic Heterogeneity. Edited by Peter Auer. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 29–55. [Google Scholar]

- Baldry, Anthony, and Paul Thibault. 2006. Multimodal Transcription and Text Analysis. A Multimedia Toolkit and Coursebooks with Associated On-Line Course. London: Equinox. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, Lawrie. 2012. The Role of Code-Switching in the Creation of an Outsider Identity in the Bilingual Film. Communicatio 38: 247–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthes, Roland. 1975. An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative. New Literary History 6: 237–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarek, Monika. 2011. The Stability of the Televisual Character. A Corpus Stylistic Case Study. In Telecinematic Discourse. Approaches to the Language of Films and Television Series. Edited by Roberto Piazza, Monika Bednarek and Fabio Rossi. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek, Monika. 2018. Language and Television Series. A Linguistic Approach to TV Dialogue. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beseghi, Micòl. 2019. The Representation and Translation of Identities in Multilingual TV Series: Jane the Virgin, a Case in Point. MonTI Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación 4: 145–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blommaert, Jan, and Ben Rampton. 2015. Language and Superdiversity. In Language and Superdiversity. Edited by Karel Arnaut, Jan Blommaert, Ben Rampton and Massimiliano Spotti. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 21–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosseaux, Charlotte. 2015. Dubbing, Film and Performance. Oxford and Frankfurt: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Cascajosa Virino, Concepción. 2009. La nueva edad dorada de la televisión norteamericana. Secuencias Revista de Historia Del Cine 26: 7–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cashman, Holly R., and Juan Antonio Trujillo. 2018. Queering Spanish as a Heritage Language. In The Routledge Handbook of Spanish as a Heritage Language. Edited by Kim Potowski and Javier Muñoz-Basols. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 124–141. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Charles B. 2021. Phonetics and Phonology of Heritage Languages. In The Cambridge Handbook of Heritage Languages and Linguistics. Edited by Silvina Montrul and Maria Polinsky. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 581–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaume, Frederic. 2004. Cine y Traducción. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Chaume, Frederic. 2012. Audiovisual Translation: Dubbing. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: St. Jerome Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Comeford, Chris. 2023. Cinematic Digital Television. Negotiating the Nexus of Production, Reception and Aesthetics. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Corrius, Montse, and Patrick Zabalbeascoa. 2011. Language Variation in Source Texts and Their Translations. Target: International Journal of Translation Studies 23: 113–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortvriend, Jack. 2018. Stylistic Convergences between British Film and American Television: Andrew Haigh’s Looking. Critical Studies in Television 13: 96–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W., and J. David Creswell. 2018. Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- De Higes-Andino, Irene. 2014a. Estudio descriptivo comparativo de la traducción de filmes plurilingües: El caso del cine británico de migración y diáspora. Ph.D. thesis, Universitat Jaume I, Castelló de la Plana, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- De Higes-Andino, Irene. 2014b. The Translation of Multilingual Films: Modes, Strategies, Constraints and Manipulation in the Spanish Translations of It’s a Free World…. Linguistica Antverpiensia 13: 211–31. [Google Scholar]

- De Higes-Andino, Irene, Ana María Prats-Rodríguez, Juan José Martínez-Sierra, and Frederic Chaume. 2014. Subtitling Language Diversity in Spanish Immigration Films. Meta 58: 134–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cadena, Marisol. 2000. Indigenous Mestizos: The Politics of Race and Culture in Cuzco, Peru, 1919–1991. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eder, Jens. 2010. Understanding Characters. Projections 4: 16–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embry, Marcus. 1996. Cholo Angels in Guadalajara: The Politics and Poetics of Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera. Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 8: 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falbe, Sandra. 2014. The Spoken Language in a Multimodal Context. Description, Teaching, Translation. In The Spoken Language in a Multimodal Context. Description, Teaching, Translation. Edited by Jenny Brumme and Sandra Falbe. Berlin: Frank & Timme, p. 135. [Google Scholar]

- Feuer, Jane. 2007. HBO and the Concept of Quality TV. In Quality TV. Contemporary American Television and beyond. Edited by Janet McCabe and Kim Akass. London and New York: T. B. Tauris, pp. 145–57. [Google Scholar]

- Franzosi, Roberto. 2010. Quantitative Narrative Analysis. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Frei, Dana. 2012. Challenging Heterosexism from the Other Point of View. Representations of Homosexuality in Queer as Folk and the L Word, 1st ed. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Goltz, Dustin Bradley. 2016. Still Looking. Temporality and Gay Aging in US Television. In Serializing Age: Aging and Old Age in TV Series, 1st ed. Edited by Maricel Piqueras and Anita Wohlmann. Biefield: Transcript Verlag, pp. 187–206. [Google Scholar]

- Haigh, Andrew. 2011. Weekend. Glasgow: Synchronicity Films. [Google Scholar]

- Haigh, Andrew. 2016. Looking: The Movie. New York: HBO. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Kira, and Chad Nilep. 2015. Code-Switching, Identity, and Globalization. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis. Edited by Deborah Tannen, Heidi E. Hamilton and Deborah Schiffrin. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp. 597–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargraves, Hunter. 2020. Looking. Smartphone Aesthetics. In How to Watch Television. Edited by Ethan Thompson and Jason Mittell. New York: New York University, pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Idrovo, René. 2021. The Immersive Continuity of Roma: Towards the Consolidation of an Alternative Audio-Visual Style. Music, Sound, and the Moving Image 15: 167–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias Urquízar, José. 2021. Looking at Redefining Sex(Uality). Reinforcing Sexual References in the Spanish Dubbing of Looking. Babel 67: 579–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias Urquízar, José. 2022. Chaperos, Rent Boys, and Sex Workers: Translating Attitudes towards Male Sex Work in the Spanish Dubbing of the US TV Series Looking. Sexuality & Culture. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Daniel. 2021. Serializing Accumulation: Resident Evil and the Synchronization of Hollywood Cinema and Japanese Television. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 27: 1360–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keegan, Cael M. 2015. Looking Transparent. Studies in Gender and Sexuality 16: 137–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Fountain-Stokes, Lawrence. 2007. Queer Ducks, Puerto Rican Patos, and Jewish American Feygelekh: Birds and the Cultural Representation of Homosexuality. CENTRO Journal 19: 192–229. [Google Scholar]

- Lannan, Michael. 2009. Lorimer, United States.

- Lannan, Michael, David Marshall Grant, Sarah Condon, and Andrew Haigh. 2014. Looking (Season 1). New York: Fair Harbor Productions & HBO. [Google Scholar]

- Lannan, Michael, David Marshall Grant, Sarah Condon, and Andrew Haigh. 2015. Looking (Season 2). New York: Fair Harbor Productions & HBO. [Google Scholar]

- List, Christine. 1996. Chicano Images. Refiguring Ethnicity in Mainstream Film. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lytra, Vally. 2012. Multilingualism and Multimodality. In The Routledge Handbook of Multilingualism. Edited by Marilyn Martin-Jones, Adrian Blackledge and Angela Creese. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 533–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manganas, Nicholas. 2015. ‘You Only Like the Beginnings’ Ordinariness of Sex and Marriage in Looking. SQS-Lehti 9: 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Manganas, Nicholas. 2017. The New Gay Loneliness? Desire and Urban Gay Male Cultures. In Narratives of Loneliness. Multidisciplinary Perspectives from the 21st Century, 1st ed. Edited by Olivia Sagan and Eric Miller. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 225–34. [Google Scholar]

- Manganas, Nicholas. 2018. Queer Fantasies, Queer Echoes: The Post-Closet Word of Looking. In HBO’s Original Voices. Race, Gender, and Power, 1st ed. Edited by Victoria McGollum and Giuliana Monteverde. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Martí Ferriol, José Luis. 2010. Cine independiente y traducción, 1st ed. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez Pleguezuelos, Antonio Jesús. 2018. Traducción e identidad sexual. Reescrituras audiovisuales desde la Teoría Queer, 1st ed. Granada: Editorial Comares. [Google Scholar]

- Mittel, Jason. 2015. Complex TV. The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. New York and London: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montrul, Silvini. 2016. The Acquisition of Heritage Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, Sean. 2017. True Detective (2014), Looking (2014), and the Televisual Long Take. In The Long Take. Critical Approaches. Edited by John Gibbs and Douglas Pye. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 239–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz García, Javier. 2021. ‘All the Pieces Matter’: La traducción subtitulada del lenguaje vulgar en The Wire. Babel 67: 646–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz García, Javier. 2022. This America, Man. La traducción subtitulada de la variante AAVE en The Wire. Círculo de Lingüística Aplicada a La Comunicación 91: 173–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Hiram. 2015. A Taste for Brown Bodies. Gay Modernity and Cosmopolitan Desire. New York and London: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-González, Luis. 2014. Audiovisual Translation: Theories, Methods and Issues. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Perrachione, Tyler K. 2018. Recognizing Speakers across Languages. In The Oxford Handbook of Voice Perception. Edited by Sascha Frühholz and Pascal Belin. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, Roberta, Monika Bednarek, and Fabio Rossi. 2011. Introduction. Analysing Telecinematic Discourse. In Telecinematic Discourse. Approaches to the Language of Films and Television Series. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Queen, Robin. 2015. Vox Popular. The Surprising Life of Language in the Media. West Sussex: Willey Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Quijano, Anibal. 2000. Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South 1: 533–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampton, Ben, and Constadina Charalambous. 2012. Crossing. In The Routledge Handbook of Multilingualism. Edited by Marilyn Martin-Jones, Adrian Blackledge and Angela Creese. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 482–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ranzato, Irene. 2012. Gayspeak and Gay Subjects in Audiovisual Translation: Strategies in Italian Dubbing. Meta: Journal Des Traducteurs 57: 369–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranzato, Irene. 2015. ‘God Forbid, a Man!’: Homosexuality in a Case of Quality TV. Between 5: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Douglas. 2019. Transgender, Translation, Translingual Address. New York: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2012. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Stöckl, Hartmut. 2004. In Between Modes: Language and Image in Printed Media. In Perspectives on Multimodality. Edited by Eija Ventola, Cassily Charles and Martin Kaltenbacher. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Švelch, Jaroslav. 2013. The Delicate Art of Criticizing a Saviour. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 19: 303–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vich, Victor. 2003. ‘Borrachos de Amor’: Las luchas por la ciudadanía en el cancionero popular peruano. JCAS Occasional Paper 15: 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Vigil, James Diego. 2014. Cholo!: The Migratory Origins of Chicano Gangs in Los Angeles. In Global Gangs. Edited by Jennifer M. Hazen and Dennis Rodgers. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Jordán, Iván. 2021a. La traducción de masculinidades gay en la teleficción: Análisis multimodal del doblaje latinoamericano y peninsular de la serie de televisión Looking. Ph.D. thesis, Universitat Jaume I, Castelló de la Plana, Spain. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Jordán, Iván. 2021b. Translation and Telefiction: Multimodal Analysis of Paratextual Pieces for HBO’s Looking. Language Value 14: 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, Valentin, and Christoph Schubert. 2023. Zooming in Stylistic Approaches to Pop Culture. In Stylistic Approaches to Pop Culture. Edited by Valentin Werner and Chritoph Schubert. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Winke, Paula, and Susan Gass. 2013. The Influence of Second Language Experience and Accent Familiarity on Oral Proficiency Rating: A Qualitative Investigation. TESOL Quarterly 47: 762–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Description of Occurrences |

|---|---|

| Class | Characters refer to the quality of their jobs (salary and status) and their need for or lack of money. They refer to their family history and highlight their social stratum or that of other characters (mentioning class differences). |

| Body | Characters talk about (their) physical appearance, the sexual spaces of the body, and body characteristics related to age, weight, and race. They refer to the body as an object of desire or pleasure. |

| Sex | Characters refer to sexual intercourse and sexual practices, such as anal, casual, group, and oral sex. They narrate or recount sexual experiences. |

| Desire | Characters talk about sexual attraction (conscious sexual desire). They refer to their objects of desire (other characters and their bodies). They use (colloquial) expressions to describe the intensity or other qualities of said sexual attraction. |

| Race/ethnicity | Characters mention belonging to an ethnic/racial community, such as when speaking of the Latinx identity or using expressions in Spanish (as heritage speakers) to build the racial/ethnic otherness of the characters. They also use racist expressions or refer to interracial relationships as taboo. |

| Season | Homoerotic Desire | Malaise/Guilt | Well-Being/Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Patrick looks for casual sex. Patrick has a date with a doctor. | Patrick imagines his mother berating him. | |

| Patrick meets/dates Richie. | Patrick feels ashamed of dating Richie. Patrick discovers his shame of gay sex. | Patrick feels cared for and understood by Richie. | |

| Patrick meets/befriends Kevin. | Patrick has sex with Kevin. Richie breaks up with Patrick. | ||

| 2 | Patrick has an affair with Kevin. | Patrick feels guilty/ashamed for being a secret. Patrick misses Richie. | |

| Patrick moves in with Kevin. | Patrick feels insecure about having an open relationship. Patrick breaks up with Kevin. | (Time jump between season 2 finale and Looking: The Movie). Patrick moves to a different city. | |

| The Movie | Patrick meets Richie again. | Patrick says good-bye to Kevin. Patrick commits to a relationship with Richie. |

| Language Used | Language Code |

|---|---|

| English as the main language of Looking | L1 |

| Spanish as the secondary language of Looking | L3 |

| Latin American (a) and Peninsular Spanish (b) as the dubbing target languages | L2a and L2b |

| Richie’s Voice in L1 Actor: Raul Castillo | Richie’s Voice in L2a Voice Actor: Carlos Hernández | Richie’s Voice in L2b Voice Actor: Iván Jara | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global segmental production | L3 phonological features in L1 | No interlanguage phonology | No interlanguage phonology |

| Voice quality | Raspy (Deep voice) | Smooth Varying pitches | Smooth Varying pitches |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Villanueva-Jordán, I. Audiovisual Translation, Multilingual Desire, and the Construction of the Intersectional Gay Male Body. Languages 2023, 8, 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020105

Villanueva-Jordán I. Audiovisual Translation, Multilingual Desire, and the Construction of the Intersectional Gay Male Body. Languages. 2023; 8(2):105. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020105

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillanueva-Jordán, Iván. 2023. "Audiovisual Translation, Multilingual Desire, and the Construction of the Intersectional Gay Male Body" Languages 8, no. 2: 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020105

APA StyleVillanueva-Jordán, I. (2023). Audiovisual Translation, Multilingual Desire, and the Construction of the Intersectional Gay Male Body. Languages, 8(2), 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8020105