Abstract

Recent studies have shown that shì ‘be’… (de) focus sentences in Mandarin Chinese are not structurally uniform. One of the criteria to make distinctions among them is the Adjacency Condition, that is, only the right adjacent element of shì can be focused. The debate has been centered on the question of why this restriction only holds in certain types of sentences involving focus but not in all of them. We argue that the so-called Adjacency Condition is not a primary condition that regulates the distribution of different types of foci; instead, the presence or the absence of adjacency-like restriction precisely indicates the existence of two different syntactic structures involving foci: one gives rise to the adjacency effects, whereas the other one does not. Importantly, our central proposal is that any constituent that falls under the c-command domain of shì will have a chance to get a focus reading if prosodically prominent, which naturally holds for the constituents that are not adjacent to shì. Along this line, shì is analyzed as a focus domain indicator rather than the focus marker itself.

1. Introduction

In this paper, we examine shì ‘be’… (de) focus constructions in Mandarin Chinese. (1) shows initial-shì sentences, where shì is positioned in the sentence-initial position. Since the same phonological form as well as the graphic form are found in copular sentences, shì has been glossed as be. Unlike (1a) with a bare initial-shì, (1b) has a sentence-final de in addition, which is often found in structures involving nominal modifications such as relative clauses (see Section 2.1 for a detailed discussion). Generally, in initial-shì sentences the element immediately following shì obtains a focus reading. The focused constituent is intonationally prominent, indicated by underlying.

(2) shows medial-shì sentences, where shì follows the subject, in a ‘medial’ position.

| (1) | a. | shì | wǒ | zuótiān | qù-le | Bālí. | |

| be | 1sg | yesterday | go-perf | Paris | |||

| ‘It is I that went to Paris yesterday.’ | |||||||

| b. | shì | wǒ | xiān | késòu | de. | ||

| be | 1sg | first | cough | de | |||

| ‘It’s I who coughed first.’ | |||||||

| (Cheng 2008, p. 251, ex. (34), originally from Zhu 1978) | |||||||

| (2) | a. | Zhāngsān | shì | zuótiān | qù-le | Bālí. | |

| Zhangsan | be | yesterday | go-perf | Paris | |||

| ‘It was yesterday that Zhangsan went to Paris.’ | |||||||

| b. | Zhāngsān | shì | yòng máobǐ | xiě | shī | de. | |

| Zhangsan | be | with brush | write | poem | de | ||

| ‘It was with a brush that Zhangsan wrote poems.’ | |||||||

| (Hole 2011, p. 1711, ex. (11b)) | |||||||

Traditionally, shì sentences with and without the particle de have been treated indistinctly as a cleft construction in the literature (see Teng 1979; Huang 1982; Chiu 1993). The morpheme shì has been analyzed as a focus marker (see Teng 1979; Huang 1982; Xu 2004). However, recent studies have shown that shì sentences with and without de can be structurally distinct (see Simpson and Wu 2002; Cheng 2008; Paul and Whitman 2008; Hole 2011).

Pan (2017, 2019a) studied one specific case with a sentence-initial shì. He observed that in ex-situ cleft focus sentences, where an object is in an ex-situ position (i.e., in the left periphery) following shì, only the element that immediately follows shì can be focused (cf. nǐ-de tàidù ‘your attitude’ in (3)) and that this construction exhibits exhaustivity effects. He proposed that the focus meaning of the adjacent element stems from a null Foc head in the left periphery and that the exhaustiveness is attributed to the semantics of shì, which was analyzed as an ordinary copula.

| (3) | Bare initial-shì, ex situ cleft focus | ||||

| shì | nǐ-de | tàidù | gōngsī-de | lǎobǎn bù xīnshǎng __. | |

| be | 2sg-de | attitude | company-de | boss neg appreciate | |

| ‘It is your attitude that the boss of the company does not appreciate.’ | |||||

| (Pan 2019a, p. 150, ex. (75)) | |||||

However, Paul and Whitman (2008) observed that some shì sentences do not give rise to exhaustivity effects and that any item to the right of shì can be associated with focus by assigning it intonational prominence (lack of Adjacency Condition, see Section 3.1 for a detailed discussion). As shown in (4), shì occurs after the subject, thus occupying a ‘medial’ position at the surface. Not only can the adjacent adjunct receive a focus reading, but also the non-adjacent object can be contrastively focused. They argued that shì, analyzed as the focus operator in this construction, may be associated with any constituent in its c-command domain that is marked by intonational prominence (p. 417).

| (4) | Bare medial-shì | ||||||

| a. | tā | shì | zài | Běijīng | xué | yǔyánxué, | |

| 3sg | be | at | Beijing | study | linguistics | ||

| bú | shì | zài | Shànghǎi | xué | yǔyánxué. | ||

| neg | be | at | Shanghai | study | linguistcs | ||

| ‘He studies linguistics in Beijing, not in Shanghai.’ | |||||||

| b. | tā | shì | zài | Běijīng | xué | yǔyánxué, | |

| 3SG | be | at | Beijing | study | linguistics | ||

| bú | shì | zài | Běijīng | xué | fǎwén. | ||

| neg | be | at | Beijing | study | French | ||

| ‘He studies linguistics, not French, in Beijing.’ | |||||||

| (Paul and Whitman 2008, p. 415, ex. (2)), original translation | |||||||

As will be argued in the paper, the Adjacency Condition is not a primary condition that regulates the distribution of different types of foci; rather, it is only a partial generalization based on the observed language fact. In our analysis, the presence or the absence of the so-called Adjacency Condition precisely indicates the existence of two different syntactic structures involving foci: one gives rise to the apparent adjacency effects, whereas the other one does not.

In addition, building upon Pan’s (2017, 2019a) and Paul and Whitman’s (2008) analyses, we argue that the focus reading can be assigned either by the Focus head of the focus projection FocP in the left periphery, or by prosodic or intonational prominence via stress assignment. In both situations, shì is not analyzed as a focus marker (contra Teng 1979; Huang 1982; Xu 2004); instead, it signals that only the constituents that fall into its c-command domain can receive a focus reading.1 In addition, it is still shì that contributes the exhaustive meaning of all the shì … (de) patterns.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we classify six patterns of shì sentences with and without the particle de, after an introduction of shì and de. In Section 3, we re-examine the so-called Adjacency Condition and show that all shì …(de) patterns exhibit Exhaustivity Effects. In Section 4, we assume two types of syntactic structures for shì …(de) patterns. In one structure, the focus meaning has a syntactic source, cf. the Focus head of FocP in the left periphery. In the other structure, the focus meaning is assigned by prosodic prominence. In both structures, shì is analyzed as a focus domain marker, which limits the focus assignment to the elements in its c-command domain. Since the c-command domain of shì varies with respect to these distinct structures, it gives rise to the presence or absence of adjacency-like effects. We conclude in Section 5.

2. Background and Basic Description

Before presenting our classification of shì … (de) sentences, we introduce some background related to shì and de.

2.1. shì and de

shì is often glossed as cop or be in the literature because the same phonological form and graphic form are found in the formation of copular sentences, cf. (5).

| (5) | a. | Zhāngsān | shì | lǎoshī. | ||

| Zhangsan | be | teacher | ||||

| ‘Zhangsan is a teacher.’ | ||||||

| b. | zuì | wúliáo de | rén | shì | Zhāngsān. | |

| most | boring de | person | be | Zhangsan | ||

| ‘The most boring person is Zhangsan.’ | ||||||

| c. | nà | shì | Zhāng lǎoshī. | |||

| that | be | Zhang teacher | ||||

| ‘That is teacher Zhang.’ | ||||||

| d. | chāorén | shì | Clark Kent. | |||

| superman | be | Clark Kent | ||||

| ‘The superman is Clark Kent.’ | ||||||

When shì ‘be’ occurs in the contexts other than copular sentences, the resulting structure is related to focus construal. In these focus sentences, shì has been treated either as a focus/emphatic marker (Teng 1979; Huang 1982; Chiu 1993; Shi 1994; Lee 2005), a copula (Paris 1979; Paul and Whitman 2008; Pan 2017, 2019a), or a raising verb (Huang 1988). As shown in (6), shì ‘be’ seems to ‘float’ inside the clause (cf. 6a, b), though it does not ‘float’ below the verb (cf. 6c). Cheng (2008) referred to (6a) and (6b) as bare shì sentences. While in (6a), shì occurs in the sentence-initial position, in (6b), shì occurs in a ‘medial’ position, between the subject and the rest of the sentence.

Generally, the element immediately following shì receives a focus reading, indicated by underlining. As a result, it could give an impression that shì is ‘inserted’ before the focused item. Shì sentences are translated with English clefts due to their exhaustiveness, which will be examined in Section 3.2.

| (6) | a. | shì | Zhāngsān | zuótiān | qù-le | Fǎguó. | |

| be | Zhangsan | yesterday | go-perf | France | |||

| ‘It was Zhangsan that went to France yesterday.’ | |||||||

| b. | Zhāngsān | shì | zuótiān | qù-le | Fǎguó. | ||

| Zhangsan | be | yesterday | go-perf | France | |||

| ‘It was yesterday that Zhangsan went to France.’ | |||||||

| c. * | Zhāngsān | zuótiān | qù-le | shì | Fǎguó. | ||

| Zhangsan | yesterday | go-perf | be | France | |||

| (‘It was France that Zhangsan went to yesterday.’) | |||||||

To improve (6c), the structure can be switched to a pseudo-cleft structure as in (7), where the string preceding shì is followed by the particle de. This string is translated as an English free relative.2

| (7) | [Zhāngsān | zuótiān | qù | de] | shì | Fǎguó. |

| Zhangsan | yesterday | go | de | be | France | |

| ‘Where Zhangsan went yesterday was France.’ | ||||||

Focus sentences with shì can involve the particle de in addition (Chao 1968). This particle is commonly found in structures involving nominal modifications, such as attributive adjectives (cf. 8a) and relative clauses (cf. 8b). It is to be noted that the eventive verb mǎi ‘buy’ in (8b) in its bare form has a past tense reading and is then translated with English past tense.

| (8) | a. | [měilì | de] | nǚhái | |

| beautiful | de | girl | |||

| ‘a/the beautiful girl’ | |||||

| b. | [Zhāngsān | mǎi | de] | shū | |

| Zhangsan | buy | de | book | ||

| ‘the book that Zhangsan bought’ | |||||

The particle de occurs either in the sentence-final position (cf. 9a) or in a non-final verb-adjacent position (cf. 9b). As will be presented in the next section, these two cases differ in their syntactic structures.

| (9) | a. | Zhāngsān | shì | zuò huǒchē | qù Bālí | de. |

| Zhangsan | be | sit train | go Paris | de | ||

| ‘It is by train that Zhangsan went to Paris.’ | ||||||

| b. | Zhāngsān | shì | zuò huǒchē | qù de | Bālí. | |

| Zhangsan | be | sit train | go de | Paris | ||

| ‘It is by train that Zhangsan went to Paris.’ | ||||||

Before proceeding to the classification of shì .. (de) focus sentences, we point out that the shì in focus sentences must be distinguished from the emphatic shì, which can be roughly paraphrased as ‘indeed’. While the latter can be associated with a prosodic stress, similar to English emphatic do, shì in shì .. (de) focus sentences cannot be stressed. In addition, as shown in (10), Pan (2019a, p. 31) demonstrated that when preceding the negative adverb bù, shì receives stress, while bù cannot. Unlike the shì in focus sentences, the emphatic shì is always stressed by itself. We refer the readers to Pan (2017, 2019a) for an extensive discussion of the emphatic shì, which will not be discussed in this paper.

| (10) | a. | wǒ | SHÌ | bù | xǐhuān | hē | hóngjiǔ. |

| I | be | neg | like | drink | red.wine | ||

| ‘I indeed do not like drinking red wine.’ | |||||||

| b.?? | wǒ | shì | BÙ | xǐhuān | hē | hóngjiǔ. | |

| I | be | neg | like | drink | red.wine | ||

| (Intended: ‘I indeed do not like drinking red wine.’) | |||||||

2.2. Patterns

Based on the positions of shì and de, we obtain six combinational possibilities, cf. Table 1. As shown in the first column, shì can occur either in the sentence-initial position or in a ‘medial’ position, following the sentence subject. Without the occurrence of de, bare initial-shì sentences are distinguished from bare medial-shì sentences in the second column. The third and fourth columns illustrate that shì sentences can involve a sentence-final de or a non-final de respectively. The non-final de occurs between V and O, adjacent to the verb. The six structural patterns comprise almost all the types of shì…(de) sentences discussed in the literature. We show each of them in turn.

Table 1.

shì …(de) Patterns.

Under bare initial-shì, the right adjacent element can be a subject (cf. 11a), an adjunct3 (cf. 11b) or an ex-situ object (cf. 11c). The translation indicates that the right adjacent element can be contrastively focused. As will be shown in Section 3.1, the bare initial-shì pattern does not behave uniformly in the Adjacency test.

| (11) | Bare initial-shì | |||||||

| a. | shì | tā | zài Wēinísī | xué-guò | hànyǔ. | |||

| be | 3sg | at Venice | study-exp | Chinese | ||||

| ‘It is he that studied Chinese in Venice.’ | ||||||||

| b. | shì | zài | Wēinísī | tā | xué-guò | hànyǔ. | ||

| be | at | Venice | 3sg | study-exp | Chinese | |||

| ‘It is in Venice that he studied Chinese.’ | ||||||||

| c. | shì | zhè-bù diànyǐngi, | tā | kàn-le | sān-cì | ti. | ||

| be | this-clf movie | 3sg | see-perf | three-time | ||||

| ‘It is this movie that he saw three times.’ | ||||||||

Examples (12) and (13) illustrate the bare medial-shì pattern, in which shì follows the subject tā ‘s/he’. In (12), shì precedes an adjunct. In (13), it seems that an ex-situ object can occur in the bare medial-shì pattern. However, the adjacency test as examined in Section 3.1 indicates that (13) in fact instantiates a bare initial-shì (11c), with the subject tā ‘he’ moved higher than the initial-shì.4

| (12) | Bare medial-shì | ||||||

| tā | shì | zài Wēinísī | xué-guò | hànyǔ. | |||

| 3sg | be | at Venice | study-exp | Chinese | |||

| ‘It is in Venice that he studied Chinese.’ | |||||||

| (13) | tāj | shì | zhè-bù diànyǐngi tj | kàn-le | sān-cì | ti. | |

| 3sg | be | this-clf movie | see-perf | three-time | |||

| ‘It is this movie that he saw three times.’ | |||||||

As shown in (14a, b) and (15a), the sentence-final de can co-occur with both an initial-shì and a medial-shì. As shown in (14c, 15b), both patterns do not tolerate an ex-situ object (see Paul and Whitman 2008).

| (14) | Initial-shì … final-de | |||||||

| a. | shì | tā | zài Wēinísī | xué-guò | hànyǔ | de. | ||

| be | 3sg | at Venice | study-exp | Chinese | de | |||

| ‘It is he that studied Chinese in Venice.’ | ||||||||

| b. | shì | zài | Wēinísī | tā | xué-guò | hànyǔ | de. | |

| be | at | Venice | 3sg | study-exp | Chinese | de | ||

| ‘It is in Venice that he studied Chinese.’ | ||||||||

| c. * | shì | zhè-bù diànyǐngi, | tā | kàn-le | sān-cì ti | de. | ||

| be | this-clf movie | 3sg | see-perf | three-time | de | |||

| (‘It is this movie that he saw three times.’) | ||||||||

| (15) | Medial-shì … final-de | |||||||

| a. | tā | shì | zài Wēinísī | xué-guò | hànyǔ | de. | ||

| 3sg | be | at Venice | study-exp | Chinese | de | |||

| ‘It is in Venice that he studied Chinese.’ | ||||||||

| b. * | tā | shì | zhè-bù diànyǐngi, | kàn-le | sān-cì ti | de. | ||

| 3sg | be | this-clf movie | see-perf | three-time | de | |||

| (‘It is this movie that he saw three times.’) | ||||||||

| c. * | wǒmen | shì | gùgōngi | qu (le) | ti | de. | ||

| 1pl | be | imperial.palace | go-perf | de | ||||

| (‘It was the imperial palace that we went to.’) | ||||||||

| (Paul and Whitman 2008, p. 432, ex. (48b)), -le ‘perf’ added by us | ||||||||

With the non-final verb-adjacent de, both initial-shì and medial-shì sentences exhibit extra restrictions. In contrast to the examples with the final-de, (16) and (17) show that de is adjacent to the verb xué ‘study’, preceding the object, and that only an eventive predicate in its bare form is allowed in these two patterns.

| (16) | Initial-shì … non-final de | |||||

| shì | tā | zài Wēinísī | xué | de | hànyǔ. | |

| be | 3sg | at Venice | study | de | Chinese | |

| ‘It is he that studied Chinese in Venice.’ | ||||||

| (17) | Medial-shì … non-final de | |||||

| tā | shì | zài Wēinísī | xué | de | hànyǔ. | |

| 3sg | be | at Venice | study | de | Chinese | |

| ‘It is in Venice that he studied Chinese.’ | ||||||

As observed in Paul and Whitman (2008, sec. 5.1.1), the “shì … non-final de’’ patterns cannot contain any material above vP, such as negation, aspect markers (cf. 18a) and modal auxiliaries (cf. 18b). Only bare eventive predicates are permitted, interpreted with a past tense reading. This reading has led scholars to analyze de as T (see Simpson and Wu 2002) or as Asp (see Paul and Whitman 2008) in this pattern (see also Long’s (2013) discussion).5

| (18) | a. | shì | tā | zài Wēinísī | xué(*-le/*-guò) | de | hànyǔ. | |

| be | 3sg | at Venice | study-perf/exp | de | Chinese | |||

| ‘It is he that studied Chinese in Venice.’ | ||||||||

| b. | tā | shì | zài Wēinísī | (*néng/*yīnggāi) | xué | de | hànyǔ. | |

| 3sg | be | at Venice | can/should | study | de | Chinese | ||

| (‘It was in Venice that he could/should study Chinese’) | ||||||||

In the next section, we examine two properties related to shì…(de) sentences.

3. Adjacency Condition and Exhaustivity Effects

Scholars have not reached an agreement regarding which shì … (de) patterns obey the Adjacency Condition and give rise to Exhaustivity Effects. We examine these two properties for each of the six patterns identified above. In Section 3.1, We revisit the Adjacency Condition, which has been under debate in recent studies, and show that there is no genuine Adjacency Condition for all the shì … (de) patterns. In Section 3.2, we will show that all the shì … (de) patterns exhibit exhaustiveness, evidenced by the incompatibility with the non-exhaustive meaning imported by the additive yě ‘also’.

3.1. Adjacency Condition

Generally, the focused element must be right adjacent to shì. Material to the left of shì may not receive a focus reading. This restriction has been referred to as the Adjacency Condition or Adjacency Effect. Recent studies have shown that some shì … (de) patterns are not subject to this restriction, that is, any material to the right of shì can be associated with focus if assigned intonational prominence. No consensus has been reached concerning which pattern(s) is/are exonerated from the Adjacency Condition, cf. Paul and Whitman (2008), Cheng (2008), Hole (2011).

The relevant test is to contrast the target sentence with its negated counterpart, with prosodic prominence being assigned to the element under contrastive focus. For instance, as shown in (19), with a bare initial-shì, not only can the adjacent subject bàoyǔ ‘rainstorm’ in (19a) be contrastively focused, but also the non-adjacent object Xiānggǎng ‘Hong Kong’ (see also (45)).6 Hence, when the initial-shì precedes the subject of TP, the bare initial- shì pattern does not obey the Adjacency Condition.7

| (19) | a. | shì | táifēng | xíjuǎn-le | Àomén, |

| be | typhoon | sweep-perf | Macau | ||

| bú shì | bàoyǔ | xíjuǎn-le | Àomén. | ||

| neg be | rainstorm | sweep-perf | Macau | ||

| ‘It is the typhoon that swept through Macau, not the rainstorm.’8 | |||||

| b. | shì | táifēng | xíjuǎn-le | Àomén, | |

| be | typhoon | sweep-perf | Macau | ||

| bú shì | táifēng | xíjuǎn-le | Xiānggǎng. | ||

| neg be | typhoon | sweep-perf | Hong Kong | ||

| ‘It is Macau that the typhoon swept through, not Hong Kong.’ | |||||

In contrast with (19), when the initial-shì precedes an ex-situ object, shì can only scope over the fronted ex-situ object, not over the whole sentence or any non-adjacent material. As shown in (20a), only the clefted ex-situ object zhè-bù diànyǐng ‘this movie’ can receive a contrastive reading, but not the entire clause ‘this movie, nobody likes’. This movie in the first clause only contrasts with that movie in the second clause. By contrast, (20b) shows that contrasting the whole string to the right of shì is not possible. Furthermore, as illustrated in (20c), contrasting an element that is not adjacent to shì, such as Zhāngsān, is not possible; (20) seems to exhibit the Adjacency Condition, as opposed to (19).

| (20) | a. | shì | zhè-bù diànyǐng, | dàjiā | hěn | bù | xǐhuān | kàn; |

| be | this-clf movie | everyone | very | neg | like | see | ||

| bú shì | [nà-bù diànyǐng], | dàjiā | hěn | bù | xǐhuān | kàn. | ||

| neg be | that-clf movie | everyone | very | neg | like | see | ||

| ‘It is [this movie] that nobody likes, not [that movie].’ | ||||||||

| (Pan 2019a, p. 149, ex. (73)) | ||||||||

| b. * | shì | zhè-bù | diànyǐng, | dàjiā | hěn bù xǐhuān | kàn; | ||

| be | this-clf | movie | everyone | very neg like | see | |||

| bú shì | nà-bù | diànyǐng, | guānzhòng | de rèqíng bù gāo. | ||||

| neg be | that-clf | movie | audience | de enthusiasm neg high | ||||

| (‘It is [this movie that nobody likes], not [it is that movie that the audience is not enthusiastic about].’) | ||||||||

| (Pan 2019a, p. 148, (71)) | ||||||||

| c. * | shì | zhè-bù diànyǐng, | Zhāngsān | hěn | bù | xǐhuān | kàn; | |

| be | this-clf movie | Zhangsan | very | neg | like | see | ||

| bú shì | zhè-bù diànyǐng, | Lǐsì | hěn | bù | xǐhuān | kàn. | ||

| neg be | this-clf film | Lisi | very | neg | like | see | ||

| (‘It is [Zhangsan] that does not like this movie, not [Lisi].’) | ||||||||

However, as shown in (21), the NP part under focus is in fact not adjacent to shì, indicating that the initial-shì sentence with an ex-situ object does not obey the Adjacency Condition. Hence, the contrast between (19) and (20) suggests that (19) has a bigger scope for the focus to be assigned than (20).

| (21) | Bare initial-shì, ex-situ cleft focus | ||||||

| shì | nǐ-de | tàidù, | gōngsī-de | lǎobǎn | bù | xīnshǎng __. | |

| be | you-de | attitude | company-de | boss | neg | appreciate | |

| bú shì nǐ-de | yīzhuó, | gōngsī-de | lǎobǎn | bù | xīnshǎng __. | ||

| neg be 2sg-de | dressing | company-de | boss | neg | appreciate | ||

| ‘It is your attitude that the boss of the company does not appreciate, not your way of dressing.’ | |||||||

Similarly, as illustrated in (22) and (23), bare initial-shì … de sentences seem to exhibit the Adjacent Condition because the non-adjacent adjunct and object cannot be assigned focus (cf. b, c). However, (d) shows that the non-adjacent NP part can be assigned focus, indicating a limited scope for focus assignment and the lack of a genuine Adjacency Condition.

| (22) | Initial-shì … final-de | ||||||

| a. | shì | Zhāngsān | zuótiān | qù | Fǎguó | de, | |

| be | Zhangsan | yesterday | go | France | de | ||

| bú shì | Lǐsì | zuótiān | qù | Fǎguó | de. | ||

| neg be | Lisi | yesterday | go | France | de | ||

| ‘It was Zhangsan that went to France yesterday, not Lisi.’ | |||||||

| b. * | shì | Zhāngsān | zuótiān | qù | Fǎguó | de, | |

| be | Zhangsan | yesterday | go | France | de | ||

| bú shì | Zhāngsān | qiántiān | qù | Fǎguó | de. | ||

| neg be | Zhangsan | day.before.yesterday | go | France | de | ||

| (‘It was yesterday that Zhangsan went to France, not the day before yesterday.’) | |||||||

| c. * | shì | Zhāngsān | zuótiān | qù | Fǎguó | de, | |

| be | Zhangsan | yesterday | go | France | de | ||

| bú shì | Zhāngsān | zuótiān | qù | Yìdàlì | de. | ||

| neg be | Lisi | yesterday | go | Italy | de | ||

| (‘It was France that Zhangsan went to yesterday, not Italy.’) | |||||||

| d. | shì | Zhāngsān de mèimei | zuótiān | qù | Fǎguó | de, | |

| be | Zhangsan de younger.sister | yesterday | go | France | de | ||

| bú shì | Zhāngsān de gēge | zuótiān | qù | Fǎguó | de. | ||

| neg be | Zhangsan de elder.brother | yesterday | go | France | de | ||

| ‘It was Zhangsan’s younger sister that went to France yesterday, not Zhangsan’s elder brother.’ | |||||||

| (23) | Initial-shì … non-final de | ||||||

| a. | shì | Zhāngsān | zuótiān | qù | de | Fǎguó, | |

| be | Zhangsan | yesterday | go | de | France | ||

| bú shì | Lǐsì | zuótiān | qù | de | Fǎguó. | ||

| neg be | Lisi | yesterday | go | de | France | ||

| ‘It was Zhangsan that went to France yesterday, not Lisi.’ | |||||||

| b. * | shì | Zhāngsān | zuótiān | qù | de | Fǎguó, | |

| be | Zhangsan | yesterday | go | de | France | ||

| bú shì | Zhāngsān | qiántiān | qù | de | Fǎguó. | ||

| neg be | Zhangsan | day.before.yesterday | go | de | France | ||

| (‘It was yesterday that Zhangsan went to France, not the day before yesterday.’) | |||||||

| c. * | shì | Zhāngsān | zuótiān | qù | de | Fǎguó, | |

| be | Zhangsan | yesterday | go | de | France | ||

| bú shì | Zhāngsān | zuótiān | qù | de | Yìdàlì. | ||

| neg be | Zhangsan | yesterday | go | de | Italy | ||

| (‘It was France that Zhangsan went to yesterday, not Italy.’) | |||||||

| d. | shì | Zhāngsān de mèimei | zuótiān | qù | de | Fǎguó, | |

| be | Zhangsan de younger.sister | yesterday | go | de | France | ||

| bú shì | Zhāngsān de gēge | zuótiān | qù | de | Fǎguó. | ||

| neg be | Zhangsan de elder.brother | yesterday | go | de | France | ||

| ‘It was Zhangsan’s younger sister that went to France yesterday, not Zhangsan’s elder brother.’ | |||||||

In contrast with initial-shì patterns, all the medial-shì patterns permit any element to the right of shì to be assigned a focus reading by intonational prominence, yielding the lack of the so-called Adjacency Condition. The bare medial-shì pattern is illustrated in (24). As shown in (24a), the right adjacent adjunct zài Shànghǎi ‘at Shanghai’ can be focused to contrast with zài Běijīng ‘at Beijing’. In addition, (24b) shows that the non-adjacent object can be contrastively focused. As illustrated in (24c), elements to the left of shì cannot be associated with focus, even if intonationally prominent.

| (24) | Bare medial-shì | ||||||||

| a. | tā | shì | zài | Běijīng | xué | yǔyánxué, | |||

| 3sg | be | at | Beijing | study | linguistics | ||||

| bú | shì | zài | Shànghǎi | xué | yǔyánxué. | ||||

| neg | be | at | Shanghai | study | linguistics | ||||

| ‘It is in Beijing that he studies linguistics, not in Shanghai.’ | |||||||||

| b. | tā | shì | zài | Běijīng | xué | yǔyánxué, | |||

| 3sg | be | at | Beijing | study | linguistics | ||||

| bú | shì | zài | Běijīng | xué | fǎwén. | ||||

| neg | be | at | Beijing | study | French | ||||

| ‘It is linguistics that he studies in Beijing, not French.’ | |||||||||

| (Paul and Whitman 2008, p. 415, ex. (2)), our translation | |||||||||

| c. # | tā | shì | zài | Běijīng | xué | yǔyánxué, | |||

| 3SG | be | at | Beijing | study | linguistics | ||||

| bú | shì | nǐ | shì | zài | Běijīng | xué | yǔyánxué. | ||

| neg | be | 2sg | be | at | Beijing | study | linguistics | ||

| (‘It is he that studies linguistics in Beijing, not you.’) | |||||||||

Examples (25) and (26) illustrate two medial-shì … de patterns. Any material to the right of shì can receive a focus reading if assigned prosodic prominence.9

| (25) | Medial-shì .. final-de | |||||||

| a. | tā | shì | zuótiān | kāichē | qù | Fǎguó | de, | |

| 3sg | be | yesterday | drive.car | go | France | de | ||

| bú | shì | qiántiān | kāichē | qù | Fǎguó | de. | ||

| neg | be | day.before.yesterday | drive.car | go | France | de | ||

| ‘It was yesterday that he went to France by driving, not the day before yesterday.’ | ||||||||

| b. | tā | shì | zuótiān | kāichē | qù | Fǎguó | de, | |

| 3sg | be | yesterday | drive.car | go | France | de | ||

| bú | shì | zuótiān | kāichē | qù | Yìdàlì | de. | ||

| neg | be | yesterday | drive.car | go | Italy | de | ||

| ‘It was France that he went to by driving, not Italy.’ | ||||||||

| (26) | Medial-shì .. non-final de | ||||||

| a. | tā | shì | zuótiān | qù | de | Fǎguó, | |

| 3sg | be | yesterday | go | de | France | ||

| bú | shì | qiántiān | qù | de | Fǎguó. | ||

| neg | be | day.before.yesterday | go | de | France | ||

| ‘It was yesterday that he went to France, not the day before yesterday.’ | |||||||

| b. | tā | shì | zuótiān | qù | de | Fǎguó, | |

| 3sg | be | yesterday | go | de | France | ||

| bú | shì | zuótiān | qù | de | Yìdàlì. | ||

| neg | be | yesterday | go | de | Italy | ||

| ‘It was France that he went to yesterday, not Italy.’ | |||||||

As shown above, there is in fact no genuine Adjacency Condition. The difference between two groups of patterns resides in the scope or domain to which a focus reading can be assigned. We have shown that most initial-shì patterns have a limited domain for focus assignment, whereas medial-shì sentences seem to be ‘freer’, since any material to the right of shì can be targeted by focus assignment. In Section 4, we argue for two types of syntactic structures, in which the domain for focus assignment varies with respect to the position of the domain marker shì.

3.2. Exhaustivity Effects

In the literature, the additive particle yě ‘also’ has been used to test whether the focus construction exhibits Exhaustivity Effects (see Zubizarreta and Vergnaud 2006) or the Exclusiveness Condition (see Paul and Whitman 2008). As shown in (27), the additive particle also indicates that ‘more instantiations of the action/state described in the predicate have occurred for different referents, therefore, marking the referent it modifies non-exhaustive’ (Van der Wal 2016, p. 275). The unacceptability suggests that the English cleft sentence gives rise to exhaustivity effects that are thus incompatible with also.

| (27) | It is Mary that I gave the book to. #And it is John that I gave the book to also. |

| (Paul and Whitman 2008, p. 419, ex. (10)) |

Although the surface string of shì …(de) sentences does not always resemble that of English clefts, the Exhaustivity test shows that all the shì … (de) focus sentences are not compatible with the additive yě ‘also’, indicating the presence of exhaustiveness, cf. Table 2.

Table 2.

Exhaustivity Effects.

We begin with initial-shì sentences. As shown in (28), Paul and Whitman (2008) demonstrated that the addition of the additive yě ‘also’ induces a contradiction, suggesting that the focused subject Akiu excludes other alternatives, such as Zhangsan.

| (28) | # | shì | Akiu | hē-le | hóngjiŭ, | dàn yě | shì | Zhāngsān. |

| be | Akiu | drink-perf | red.wine | but also | be | Zhangsan. | ||

| (‘It’s Akiu who drank red wine, but also Zhangsan.’) | ||||||||

| (Paul and Whitman 2008, p. 426, ex. (35)) | ||||||||

As shown in Pan (2017, 2019a), the bare initial-shì with an ex-situ object is incompatible with the non-exhaustive meaning induced by the occurrence of yě ‘also’.

| (29) | * | shì | zhè-bù diànyǐng, | dàjiā | hěn bù | xǐhuān | kàn; |

| be | this-clf movie | everyone | very neg | like | see | ||

| yě shì | nà-bù diànyǐng, | dàjiā | yě hěn bù | xǐhuān | kàn. | ||

| also be | that-clf movie | everyone | also very neg | like | see | ||

| (‘It is [this movie] that nobody likes; it is also that movie that nobody likes.’) | |||||||

| (Pan 2019a, p. 149, ex. (74)) | |||||||

As illustrated in (30) and (31), initial-shì … de sentences are not compatible with the additive yě ‘also’.

| (30) | * | shì | Zhāngsān | qù Bālí | de; | yě | shì | Lǐsì qù Bālí | de. |

| be | Zhangsan | go Paris | de | also | be | Lisi go Paris | de | ||

| (‘It is Zhangsan that went to Paris; it is also Lisi that went to Paris.’) | |||||||||

| (31) | * | shì | Zhāngsān mǎi de nà-běn shū; | yě | shì Lǐsì mǎi de nà-běn shū. |

| be | Zhangsan buy de that-clf book | also | be Lisi buy de that-clf book | ||

| (‘It is Zhangsan that bought that book; it is also Lisi that bought that book.’) | |||||

Bare medial-shì sentences are not compatible with yě either. As shown in (32), zuótiān ‘yesterday’ exclusively satisfies the content of presupposition, while excluding other alternatives such as qiántiān ‘the day before yesterday’.

| (32) | * | Zhāngsān | shì | zuótiān | qù-le | Fǎguó; |

| Zhangsan | be | yesterday | go-perf | France | ||

| yě | shì | qiántiān | qù-le | Fǎguó. | ||

| also | be | day.before.yesterday | go-perf | France | ||

| (‘It was yesterday that Zhangsan went to France; it is also the day before yesterday that Zhangansan went to France.’) | ||||||

Our judgement is not shared with some previous studies. Based on their examples in (33a), Paul and Whitman (2008) concluded that bare medial-shì sentences do not exhibit the Exclusiveness Condition because the additive yě ‘also’ does not induce a contradiction. They argued that bare medial-shì sentences pattern as a case of association with focus (see Jackendoff 1972; Rooth 1985), namely, any element to the right of the focus operator may be associated with focus by assigning it intonational prominence. Hence, Paul and Whitman (2008) did not translate the sentence of (33a) as involving clefts. This conclusion is followed by Hole (2011). However, we observe a problem in (33a), that is, the morpheme shì is absent in the second clause containing yě. This example is therefore unable to indicate whether the bare medial-shì is compatible with the additive particle. In contrast with (33a), Hole’s (2011) example as in (33b) included shì in the second clause. Native speakers do not judge these sentences as grammatical when the second clause is presented with a complete formulation of the first clause, giving rise to Exhaustivity Effects.

| (33) | a. | tā | shì zài Běijīng xué-guò zhōngwén Ø, | dàn yě zài Shànghǎi xué-guò. |

| 3sg | be at Beijing study-exp Chinese | but also at Shanghai study-exp | ||

| ‘She studied Chinese in Beijing, but she also studied Chinese in Shanghai.’ | ||||

| (Paul and Whitman 2008, p. 420, ex. (12b)), original translation | ||||

| b. | tā | shì zài Běijīng xué-guò yǔyánxué, | dàn yě shì zài Shànghǎi xué-guò. | |

| s/he | cop at Beijing study-asp linguistics | but also cop at Shanghai study-asp | ||

| ‘(S)he studied Chinese in Beijing, but also in Shanghai.’ | ||||

| (Hole 2011, p. 1714, ex. (22)), original translation | ||||

Regarding medial-shì … de sentences, as illustrated in (34) and (35), we agree with Paul and Whitman’s (2008) observation that they are subject to the exclusiveness condition.

| (34) | # | tā | shì zài Běijīng xué zhōngwén de, | dàn yě shì zài Shànghǎi xué de. |

| 3SG | be at Beijing study Chinese de | but also be at Shanghai study de | ||

| (‘It’s in Beijing that he studied Chinese, but also in Shanghai.’) | ||||

| (Paul and Whitman 2008, p. 420, ex. (12a)) | ||||

| (35) | # | wǒ | shì | xiě | de shī, | yě | shì | xiě | de sǎnwén. |

| 1sg | be | write de poem, | also | be | write de prose | ||||

| (‘It is poetry that I wrote, and also prose.’) | |||||||||

| (Paul and Whitman 2008, p. 429, fn.15 ex. (iv) | |||||||||

Pan (2019a) argued that shì is the source of exhaustiveness. A strong argument for this view stems from the diachrony of shì. In classical Chinese, shì was used as a demonstrative, equivalent to this. Since demonstratives are related to definiteness and uniqueness, it is reasonable to assume that shì bears a D feature that is associated with uniqueness, which is in turn responsible for the exhaustive meaning. Given that all the shì…(de) sentences are diagnosed with exhaustiveness, we extend Pan’s analysis to all of them.

4. Analysis

In our account, shì is analyzed as a focus-domain marker, rather than a focus marker (contra Teng 1979; Huang 1982; Xu 2004); namely, only constituents that fall in the c-command domain of shì will have a chance to have a contrastive focus reading if prosodically prominent. To account for the so-called Adjacency Condition in shì … (de) patterns, we argue for two types of syntactic structures, one involving a Focus head in the left periphery, the other not. As schematized in (36), (36a) and (36b) represent two specific structural configurations that exploit the focus head in the left periphery, whereas (36c) does not involve the focus head. In the structure (36a), since only XP falls in the c-command domain of shì, it can have a focus reading. YP cannot be focused, because it does not fall in the c-command of shì. As argued in Section 4.1, the structure in (36a) is concretized by Pan’s (2017, 2019a) FocP, in which it is the null focus head that assigns a focus reading. [Shì XP] is positioned inside the spec of FocP. This structure thus gives rise to the apparent Adjacency Effects.10 (36b) resembles (36a) in that FocP is implied in both structures; however, these two structures differ in one important aspect: in (36b), both XP and YP fall under the focus domain of shì. Since both XP and YP fall into the c-command domain of shì, both can receive a contrastive focus reading if assigned prosodic prominence, giving rise to the lack of Adjacency Effects. We propose that it is FocP that assigns a focus reading to XP and YP, but it is prosody that brings out a contrastive reading. Unlike (36a/b), the structure in (36c) does not involve a FocP in the left periphery. In the structure (36c), shì takes the rest of the sentence as complement, including XP, YP and ZP. Since XP, YP and ZP all fall in the c-command domain of shì, all of them can receive a focus reading if assigned prosodic prominence, giving rise to the lack of Adjacency Effects. In Section 4.2, we will argue that shì is the matrix verb and that the contrastive focus reading is assigned through prosodic prominence, such as stress assignment, to any material in the c-command domain of shì. As a result, there is no Adjacency Condition in our analysis.

| (36) | a. | [FocP [shì | XP], [Foc‘ [… YP …]] |

| b. | [FocP [shì | [ XP … YP …]], [Foc‘ [… ZP …]] | |

| c. | [TP [vP shì | [ XP … YP …ZP]]] |

4.1. Structure (36a): FocP

As shown in Section 3.1, there is no genuine Adjacency Condition in all the shì …(de) patterns. The adjacency-like behavior is in fact due to a limited scope for focus assignment. For this situation, we adopt the structure of (36a). It concerns ‘bare initial-shì + ex-situ object’, ‘initial-shì … final-de’ and ‘initial-shì … non-final-de’. We extend Pan’s (2017, 2019a) analysis of ex-situ cleft focus structure to this group of patterns.

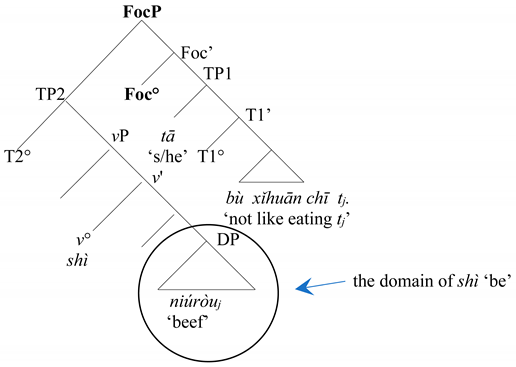

As argued in Pan (2019a), this object moves and remerges with shì, resulting as part of the specifier of FocP.11 The null Foc head provides its Spec with a focus reading. We clarify that shì never moves; instead, it is always base-generated. More importantly, shì alone can never occupy Spec, FocP; it is the entire constituent [shì + XP] that occupies Spec, FocP. Given the requirement imposed by the domain marker shì, the focus must fall in its c-command domain, which only includes the ex-situ object niúròu ‘beef’.

| (37) | Initial-shì + ex-situ object | |||||

| a. | [FocP [TP2 shì [niúròu]j, [Foc’ [Focº ∅] [TP1 | tā | bù | xǐhuān | chī tj ]]]]. | |

| be beef | 3sg | neg | like | eat | ||

| ‘It is beef that he does not like eating.’ | ||||||

| b. |  | |||||

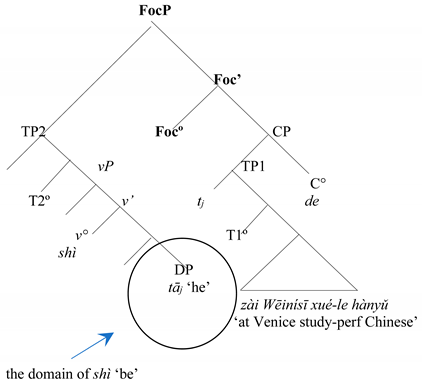

We extend this analysis to the two types of “initial-shì … de” patterns. To account for the ‘’initial-shì … final-de’’ pattern, we assume that de is in C (Cheng 2008; Hole 2011). Recently, Pan and Xu (2022) argued that the final de is in an Assertion head, which is higher than the S.Asp head and lower than the iForce head (see detailed discussion below). The null Foc head takes as complement a lower CP headed by de.12 The subject tā ‘he’ is dislocated and remerges with shì. The result of this merging is part of the Spec of FocP. The subject tā ‘he’ receives a focus reading from the Foc head. Since tā ‘he’ is in the c-command domain of shì, the focus assignment is rendered possible. The rest of the clause is not in the c-command domain of shì; therefore, no focus can be assigned to it. Consequently, the so-called Adjacency Condition is not a genuine condition that regulates the distribution of foci. The presence of this ‘restriction’ as in (38) is due to the fact that the c-command domain of shì is inside the Spec of FocP.13

| (38) | Initial-shì … final-de | |||||||

| a. | [FocP [TP2 shì | tāj ] [Foc’ [Focº ∅] [TP1 tj | zài | Wēinísī | xué-le | hànyǔ | de]]]. | |

| be | 3sg | at | Venice | study-perf | Chinese de | |||

| ‘It is he that studied Chinese in Venice.’ | ||||||||

| b. |  | |||||||

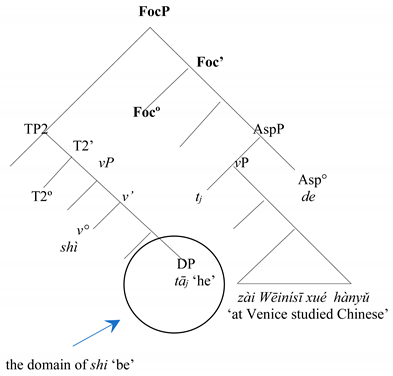

Regarding the ‘’initial-shì … non-final de’’ pattern, we follow Paul and Whitman (2008) in assuming that de is in Asp head. Recall that the structure between shì and non-final verb-adjacent de excludes any material above vP. To account for the Adjacency Condition, we apply the FocP analysis to the case with non-final de. As shown in (39), the AspP headed by de is part of the complement of Foc head. Again, the merging of shì with the dislocated subject tā ‘he’ is within Spec of FocP. The domain marker shì limits the focus reading, which is assigned by the Foc head, to its c-command domain. To explain the verb-adjacent position of de, either de undergoes some morphological movement, or the direct object moves out of AspP, followed by the remnant movement of AspP.

| (39) | Initial-shì … non-final de | |||||||

| a. | [FocP [TP2 shì | tāj ] [Foc’ [Focº ∅] [ [AspP tj | zài | Wēinísī | xué | de | hànyǔ]]]]. | |

| be | 3sg | at | Venice | study | de | Chinese | ||

| ‘It is he that studied Chinese in Venice.’ | ||||||||

| b. |  | |||||||

4.2. Structure (36b): FocP

Like the structure (36a, repeated below) shown in the previous section, (36b) involves a Focus projection in the left periphery, in which the c-command domain of shì is inside the Spec of FocP. Recall our claim that only the constituents that fall in the c-command domain of shì can be assigned a focus reading. In addition, the structure in (36b) concerns the same group of initial-shì …(de) patterns, namely, ‘bare initial-shì + ex-situ object’, ‘initial-shì … final-de’ and ‘initial-shì … non-final-de’. However, unlike the type of (36a) presented in Section 4.1, (36b) seems to lack the so-called Adjacency Effects, that is, both XP and YP, falling in the c-command domain of shì, can receive a contrastive focus reading if assigned prosodic prominence (see Section 3.1 for a detailed demonstration).

| (36) | a. | [FocP [shì | XP], [Foc‘ [… YP …]] |

| b. | [FocP [shì | [ XP … YP …]], [Foc‘ [… ZP …]] |

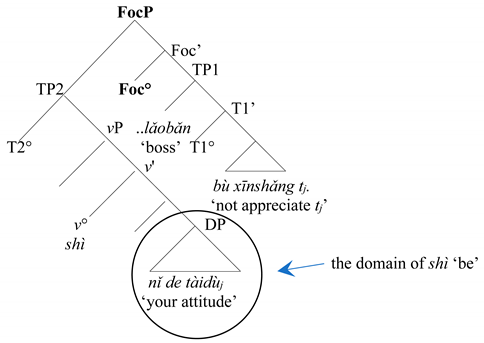

We use an example of the ‘bare initial-shì + ex-situ object’ to illustrate this. As shown in (40), both the adjacent nǐ-de ‘your’ and the non-adjacent NP tàidù ‘attitude’ of an ex-situ object can be contrastively focused. We argue that it is FocP that assigns a focus reading, but it is the prosody that brings out a contrastive meaning. We use (40c) to illustrate the domain of shì. Again, our claim is that any material in the c-command domain of shì can be targeted by a focus reading, be the whole complement of shì ‘be’, that is, nǐ-de tàidù ‘your attitude’, or part of it, that is, nǐ-de ‘your’ or tàidù ‘attitude’. While the null Foc head is responsible for the focus reading, the prosodic prominence brings about a contrastive meaning.

| (40) | Initial-shì + ex-situ object | |||||||

| a. | [FocP [TP2 shì | [nǐ-de tàidù]j, | [Foc’ [Focº ∅] [TP1 gōngsī-de | lǎobǎn | bù | xīnshǎng | tj ]]]. | |

| be | you-de attitude | company-de | boss | neg | appreciate | |||

| ‘It is your ATTITUDE that the boss of the company does not appreciate.’ | ||||||||

| b. | [FocP [TP2 shì | [nǐ-de tàidù]j, | [Foc’ [Focº ∅] [TP1 gōngsī-de | lǎobǎn | bù | xīnshǎng | tj ]]]. | |

| be | you-de attitude | company-de | boss | neg | appreciate | |||

| ‘It is YOUR attitude that the boss of the company does not appreciate.’ | ||||||||

| c. |  | |||||||

4.3. Structure (36c): No FocP

In contrast with (36a) and (36b), repeated below, the structure of (36c) shows a ‘freer’ focus assignment to any element to the right of shì, that is, XP, YP and ZP, because, as argued above, any material that falls in the c-command domain of shì can be assigned a focus reading. Furthermore, we argue that both the focus reading and the contrastive reading are assigned through prosodic prominence such as stress assignment in the case of (36c). The structure of (36c) concerns all the medial-shì patterns and the ‘initial-shì + TP’ pattern. We follow Pan (2019a) in assuming that the shì in these patterns takes as complement the entire string to its right. Unlike (36a) and (36b), there is no FocP in (36c).

| (36) | a. | [FocP [shì | XP], [Foc‘ [… YP …]] |

| b. | [FocP [shì | [ XP … YP …]], [Foc‘ [… ZP …]] | |

| c. | [TP [vP shì | [ XP … YP …ZP]]] |

Pan’s (2019a) analysis was originally made to explain the sentence as in (41), in which the negator bù scopes over the sentence-final aspect particle le, which has a change-of-state meaning. He argued that shì is the matrix verb and takes a clause CP as its complement. Here, the split CP projects until S.AspP (the projection of sentence-final aspectual particles), headed by le in S.Asp head on the right edge. Inside the complement of shì, there is a null subject pro controlled by wǒ ‘I’ (cf. Huang’s (1989) Generalized Control Rule). In addition, wǒ ‘I’ is in the matrix topic position (see also Huang 1988 and Cheng 2008 for topic analysis of pre-copula elements in this context).

| (41) | TopP > Neg > shì ‘be’ > le > TP-miss home | ||||

| [TopP wǒj | [TP1 bù | shì | [S.AspP [TP2 proj. xiǎng jiā] | le]]]. | |

| I | neg | be | miss home | le | |

| ‘As for me, it is not the case that I start missing home.’ | |||||

| (Pan 2019a, p. 25, ex. (28)) | |||||

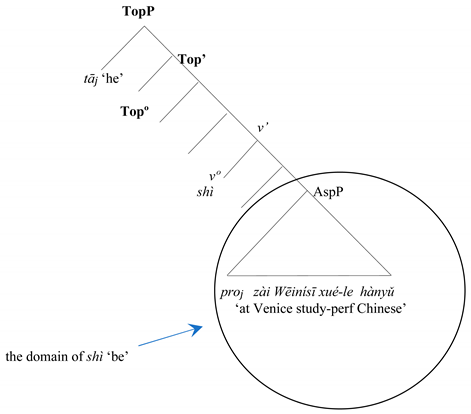

Example (41) is in fact a bare medial-shì sentence. We apply Pan’s analysis directly to another example of the same pattern as in (42). As shown below, the entire string to the right of shì is in the c-command domain of shì. Given our prosodic strategy, any item in that domain can be associated with focus by means of prosodic prominence and obtains a contrastive meaning. As a result, we observe the lack of the so-called Adjacency Effects.14

| (42) | Bare medial-shì | ||||||

| a. | [TopP | tāj | [TP1 [vP shì | [AspP proj zài Wēinísī | xué-le | hànyǔ]]]]. | |

| 3sg | be | at Venice | study-perf | Chinese | |||

| ‘It is in Venice that he studied Chinese.’ | |||||||

| b. |  | ||||||

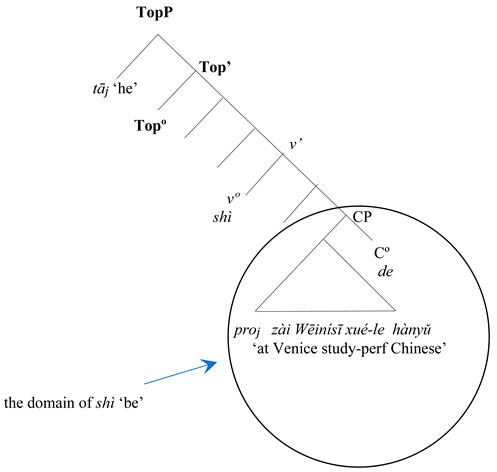

For the ‘’medial-shì … final-de’’ pattern, the particle de is merged in C, which in turn is taken as the complement of shì. The entire CP headed by de, which falls into the domain delimited by shì, can be targeted by prosodic prominence, giving rise to the contrastive focus reading.

| (43) | Medial-shì … final-de | ||||||

| a. | [TopP | tāj [TP1 shì | [CP [AspP proj zài Wēinísī | xué-le | hànyǔ | [Cº de ] ]]]]. | |

| 3sg be | at Venice | study-perf | Chinese | de | |||

| ‘It is in Venice that he studied Chinese.’ | |||||||

| b. |  | ||||||

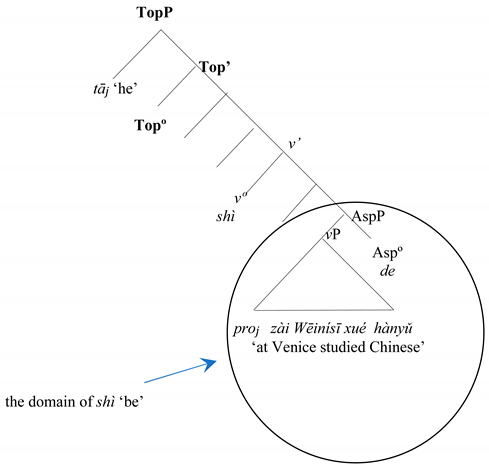

As shown in (44), the ‘’medial-shì … non-final de’’ pattern has a similar structure in which shì is the matrix verb. Recall the restriction that only the vP structure can occur in this pattern. The particle de is merged in Asp, taking vP as its complement (see Paul and Whitman 2008). The entire AspP is in the c-command domain of shì, to which the focus can be assigned by stress.15

| (44) | Medial-shì … non-final-de | ||||||

| a. | [TopP | tā [TP1 shì | [AspP [vP proj zài Wēinísī | xué | de | hànyǔ]]]]. | |

| 3sg be | at Venice | study | de | Chinese | |||

| ‘It is in Venice that he studied Chinese.’ | |||||||

| b. |  | ||||||

At last, we tackle the case in which the initial-shì precedes a TP. Recall that in this pattern, the focus can be assigned to any element c-commanded by shì. As shown in (45), shì takes the entire string to its right as complement. As a result, the entire TP, which is the c-command domain of shì, is legitimate to receive a focus reading via prosodic prominence (see Section 3.1 for examples).

| (45) | Bare initial-shì + TP | ||||

| [shì | [TP | táifēng | xíjuǎn-le | Àomén]]. | |

| be | typhoon | sweep-perf | Macau | ||

| ‘It is the typhoon that swept through Macau.’ Or ‘It is Macau that was swept through by the typhoon.’ | |||||

In all the shì … (de) patterns, shì is treated as a verb (Paul 2015; Pan 2017). In addition, to account for the exhaustivity effects, we follow Pan (2019a) in assuming that shì contributes to the exhaustive meaning, supported by a crucial diachronic argument. We have argued that shì is a domain marker rather than a focus marker. Its occurrence signals the domain to which the focus reading can be assigned. We have shown that shì can be merged either in a position inside the Spec of FocP or in the position of a matrix verb. Consequently, the c-command domain of shì varies, giving rise to the presence or absence of the so-called Adjacency Effects respectively.

Let us turn to root/non-root status of the sentence-final de. As argued by Paul and Whitman (2008), the sentence-final de in propositional assertion (that is, their ‘NP shì V O de’ pattern) is a non-root C head, which is associated with a [-finite] feature. Since the complement of the non-root C is non-finite, the subject must undergo A-movement to the matrix subject position.

| (46) | [TP | tāi | [VP | shì | [CP | [TP | ti | gēn nǐ | kāi wánxiào] | [C de] ]]]. |

| he | be | with you | open joke | de | ||||||

| ‘(It is the case that) he was joking with you.’ | ||||||||||

| Paul and Whitman (2008, p. 447, ex. (78)) | ||||||||||

An alternative view was proposed by Pan and Xu (2022). These authors used (47) to show that the sentence final de is structurally higher than the sentence-final aspectual particle le (in S.Asp head), and is lower than the yes-no question particle ma (in iForce head). They argue that de is in an Assertion head. The overall hierarchy they proposed is: AttP > SQP > iForceP > AssertionP > S.AspP > TP.

| (47) | a. | [iForce ma] > [Assertion de] > | [S.Asp le]; ’>’ | means ‘is structurally higher than’ | ||||

| [iForceP [AssertionP [S.AspP [TP | zuótiān | shì xià-guò yǔ] | le ] de ] ma]. | |||||

| yesterday | be fall-exp rain | le de ma | ||||||

| ‘Is it the case that it rained yesterday?’ | ||||||||

| b. | *[iForce ma] > [S.Asp le] > [Assertion de] | |||||||

| *[iForceP [AssertionP [S.AspP [TP | zuótiān | shì xià-guò yǔ] | de] le] ma] ? | |||||

| yesterday | be fall-exp rain | de le ma | ||||||

| Pan and Xu (2022, p. 111, ex. (53)) | ||||||||

Very importantly, this de in Pan and Xu’s framework is exactly the de in propositional assertion in the sense of Paul and Whitman (2008); however, different from Paul and Whitman’s view, we observe that this de can perfectly be used in a root sentence, thus it does not show non-root property at all. More examples can be seen in (48), where de can only have a root construal.

| (48) | a. | [AssertionP [TP | wǒ | chū | mén | qián | běnlái | kěyǐ | xǐ | gè | -zǎo] | de]. |

| 1sg | go.out | door | before | originally | can | wash | clf | shower | de | |||

| ‘It is indeed the case that I could have taken a shower before going out.’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | [AssertionP [S.AspP [TP | wǒ | běnlái | hái | xiǎng | pāi | zhāng | -zhàopiān] | láizhe] | de]. | ||

| 1sg | originally | still | want | take | clf | picture | laizhe | de | ||||

| ‘It is indeed the case that I intended to take a picture.’ | ||||||||||||

The original argument in support of the non-root status of de is that de must cooccur with the copular shì and shì takes the clause involving de as its complement. Importantly, shì can be omitted. In fact, this argument is problematic. Take (49) with the yes-no particle ma as an example. The copular shì can also appear freely in (49) and its presence is never obligatory. However, no one would use (49) to claim that the ma-sentence involves an obligatory presence of shì and that shì is phonetically omitted. Therefore, the same argument does not hold for de in shì…(de) constructions.

| (49) | tā | (shì) | míngtiān | qù | Bālí | ma? |

| 3sg | be | tomorrow | go | Paris | ma | |

| ‘(Is it) tomorrow (that) he will go to Paris?’ | ||||||

From this perspective, we have no reason to claim that de is a non-root only SFP. Therefore, it is more reasonable to treat sentences involving shì…de and those only involving the final de without shì as two different structures.

A reviewer raised a question concerning what mechanism governs the association between the intonational peak and the Focus constituent. Here are our clarifications: first, there is not necessarily a cause–consequence type of association between prosody and focus; rather, they are independent marking/interpretation strategies. For Chinese, contrastivity should be disassociated from topic and focus. A topic can be, but is not necessarily always, contrastive; the same applies to focus. A focus can be information focus or contrastive focus. According to Erteschik-Shir (2007), contrastivity should be treated as an independent component, which is differentiated from focus. Adopting this view, Pan (2015) further demonstrates that in Chinese, contrastiveness can be marked either syntactically or prosodically, and prosodic marking can only be activated as a last resort when the syntactic marking is not available. Second, in the study of interpretive ambiguities of wh-phrases in situ, Pan (2019b) showed that different combinations of stress with intonation on sentences can disambiguate the readings. He argued that those prosodic forms that have semantic effects at LF can be analyzed as phonological features in the feature bundles associated with a given lexical item in the Lexical Array. Each specific prosodic pattern (i.e., stress combined with sentence intonational pattern) corresponds to one and only one semantic interpretation at the C–I interface. Therefore, one-to-one mapping between prosody and semantics is ensured, even before the relevant derivation starts. As a result, the superficially observed ambiguity is only an illusion. Adopting this view, we argue that the focused element associated with prosodic prominence in shì sentences can have a focus feature as part of its feature bundles. See also Bianchi et al. (2015)16 for a similar proposal in their analysis of Italian corrective and mirative focus.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we argue that shì is analyzed as a domain marker rather than a focus marker. Only constituents that fall in its c-command domain can be assigned a focus reading, either by a syntactic head (Foc) or by prosodic prominence. In addition, we argue for two general syntactic structures that underlie shì .. (de) focus constructions in Mandarin Chinese. One structure has a Focus projection in the left periphery, in which the Foc head assigns a focus reading to its Spec. The copula shì is merged inside the Spec of FocP. The prosody can bring out a contrastive reading of the elements c-commanded by shì. In the other structure, shì is the matrix verb, taking as complement the entire string to its right. As a domain marker, shì limits the focus assignment to any elements in its c-command domain. The prosody contributes both a focus reading and a contrastive meaning. The fact that the domain of shì varies with these two distinct structures gives rise to the presence or absence of the adjacency-like effects. The so-called Adjacency Condition is not a primary condition that regulates the distribution of different types of foci.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.J.P. and C.L.; methodology, V.J.P. and C.L.; formal analysis, V.J.P. and C.L.; investigation, V.J.P. and C.L.; resources, V.J.P. and C.L.; data curation, V.J.P. and C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, V.J.P. and C.L.; writing—review and editing, V.J.P. and C.L.; supervision, V.J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The main claim made in this paper is that shì ‘be’ is a domain marker, not a focus marker. Based on the difference in the focus domain, we propose that the domain of shì ‘be’ varies with the different structures in which shì ‘be’ is merged. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | We comment on the structure with de which is translated as an English free relative. Unlike English free relatives, free relatives involving de in Mandarin Chinese do not involve a wh-phrase (Grosu 2002). In addition, in contrast with headed relative clauses with an overt relative Head to the right of de as in (8b), the relative clause in pseudo-clefts does not have an overt relative head. It could be the case that the headless structure as shown in (7) is related to the structure as in (i) where there is an overt head dìfāng ‘place’. The fact that (7) is head-less could be analyzed as involving omission of an overt Head or presence of a corresponding silent Head. In addition, there is one more derivational possibility to consider. By simply observing the surface structure of (ii), we could hypothesize that the free relative with de in pseudo-clefts as in (7) could be derived directly from a headed relative clause. For the moment, we must leave aside the analysis of the ‘headless’ relative clause in pseudo-clefts. We thank a reviewer for raising the question regarding the structure of the de-phrase in pseudo-clefts.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Note that it is not clear whether the adjunct in (11b) is base-generated or moved given that adverbials are quite free in distribution. By contrast, (11c) involves an ex-situ argument which originates in a post-verbal object position. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | One question is why it is not possible to have medial-shì pattern with a pre-posed object. This is because the complement of shì ‘be’ is smaller than a root clause. Hence, its complement does not tolerate a dislocated element. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Simpson and Wu (2002) used shì … final-de patterns to show that bare predicates must have a past tense reading inside the structure, cf. (ia). However, we observe that the past time reading is only associated with a bare eventive verb, not with a stative verb such as xǐhuān ‘like’, which has a present tense reading in shì …final-de patterns, cf. (ib). In addition, Shyu (2014) showed that a habitual reading is possible, cf. (ii).

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | We notice that (i) is judged as more natural than (19b), because the latter sounds redundant and phonologically heavy. Nevertheless, we will keep showing the full formulation of each shì … (de) pattern in this test for the reason that an elided, incomplete form like (i) can in fact be derived from several shì … (de) patterns after undergoing ellipsis.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | There is one distinct configuration in initial-shì sentences. As described by Paul and Whitman (2008), when the subject is not assigned intonational prominence, the truth of the entire sentence is strongly asserted. The meaning is comparable to ‘it is (really) that S’ or ‘it is because S’. Here, we share their intuition; however, we consider this case as involving a different structure. The fact that shì can be stressed itself as in (ib) suggests that we are dealing with an emphatic shì, which is of different nature than the shì in focus constructions. Recall that shì in focus constructions cannot receive stress itself (see Section 2.1; Pan 2019a). We will then leave it aside.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Without any special stress on a NP, (19) can have a broad information focus interpretation, for instance, as an answer to the question “What happened?”, as shown in (i).

Clearly, “the typhoon swept through Macau” is a piece of new information. Different from the English counterpart, shì ‘be’ in Mandarin Chinese indeed marks the focus domain. On the contrary, with shì ‘be’ preceding an ex-situ object, a broad informational focus construal is never possible. We thank a reviewer for raising the question concerning the broad focus. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | The medial-shì …non-final de pattern as shown in (i) has been referred to as object focus cleft since Zhu (1961). This pattern was considered as an oddity, because unlike (26a) the focused element is not adjacent to shì (see Paul and Whitman 2008; Hole 2011; Long 2013). However, we use (26) to show that there is nothing exceptional about this pattern because the post-de object simply finds itself in the scope of shì ‘be’ and therefore becomes legitimate for focus assignment if our account is on the right track. Furthermore, we have noticed that the examples of object focus cleft as listed in Zhu (1961), Paul and Whitman (2008) and Hole (2011) only involve a bare verb adjacent to shì ‘be’ (cf. xiě ‘write’ in (i)) and an object (cf. shī ‘poem’) without the occurrence of an adverb. By contrast, we use the example (26b) to show that the addition of an adverb (adjacent to shì) does not affect the possibility of forming an object focus sentence.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | As argued above, shì is not merged in the Focus head position. It does not assign the focus reading. Instead, the null Focus head assigns the focus reading. Shì, as a domain maker, further limits the domain in which the focus can be assigned. We follow Pan’s (2017, 2019a) idea that semantically, shì only contributes to the exhaustive meaning to the focus. As also argued by Pan (2017, 2019a), the Foc head is also involved in the lián … dōu (even-type of focus construction) where lián is in the left periphery. However, lián does not occupy the Foc head position. Lián has been analyzed as an adverb or a preposition, which contributes to the scalar meaning similar to English ‘even’. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | The ‘move and remerge’ involved in the example as in (37) (or the structure as in (36a)) is indeed like a Sideward Movement, as suggested by a reviewer. The movement is sensitive to island effects, as shown in (i).

Under the current Workspace-based definition of free MERGE, we can imagine that ‘beef’ is remerged to another Workspace. Whether this remerge gives rise to a correct interpretation, it is the C-I component that will handle the assignment of interpretation after Transfer. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | A reviewer asked why C is overtly realized in some structures while it is null in others. Our answer is that like other languages, C can be overt or covert in Mandarin Chinese. In the case of shì …final-de focus constructions, we follow Cheng (2008) and Hole (2011) in assuming that de occupies a C position. This assumption does not affect our main claim made in the paper, which is that shì is a domain marker, not a focus marker. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | A reviewer asked for a clarification of the head-final position of the particle de. As shown in the structure of (38), in contrast with the Focus head which is merged on the left (head-initial), de occupies a C head on the right (head-final), as any sentence-final particle in Chinese. We remain neutral as to whether the head-final position of C is derived by any movement for the following reasons. First, despite of being a SVO language, Mandarin Chinese can exhibit the head-final order in both clausal and nominal domains. In the clausal domain, there are many C-related sentence final particles that occur on the right (see Pan (2019a) and references therein). In the nominal domain, it is well known that Chinese is one of the few Sinitic languages which have pre-nominal relative clauses with a head-final relative Head. Second, attempts have been made to derive the head-final order from head-initial structures in the study of relative clauses. Simpson ([1997] 2003) applied Kayne’s (1994) [D+CP] structure to Chinese nominal modifications, in which de is merged in D. The relative clause CP is firstly merged as the complement of D, and then undergoes movement to the left of de, yielding a head-final de. The movement is arguably motivated by the need to satisfy the enclitic requirement of de. Another reviewer suggested us to treat de as a nominalizer. As far as focus constructions’ concern, we have not found evidence supporting the view of de as D or n. Unlike cases involving clear nominal modifications, the de-sequence in shì … de focus constructions do not distribute like DPs or NPs; two de-sequences in shì …de focus constructions cannot be conjoined by the nominal coordinator hé ‘and’. Given these reasons, we simply assume that de occupies a C head to the right of its complement. At current stage, what concerns us the most is that the structure headed by de is in the c-command domain of shi and that any material in its domain can be focused. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | In response to a reviewer’s concern of the assumption that V takes AspP as complement, this type of structure can be observed and argued for elsewhere in Mandarin Chinese such as certain control constructions, as exemplified in (i). Hence, the v-V-AspP structure is not unusual.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | A reviewer raised a question regarding the use of the term ‘medial-shì’: “the so called ‘medial-shì’: the left adjacent constituent is analyzed as a subject in (12) but as a Topic in (44). Indeed, if the structure in (44) is their proposal, the notion of ‘medial-shì’ could be dispensed with.” As described in (12), shì can follow the subject, yielding a medial-shì sentence at the surface. The term ‘medial-shì‘ is used as a descriptive term, following the recent literature particularly in Paul and Whitman (2008). The term itself only serves its descriptive purpose without implying any formal analysis. In order to be reader-friendly, we prefer keeping “medial” as a pure descriptive term. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | Bianchi et al. (2015) discussed a type of focus fronting in mirative contexts in Italian. As shown in (i), the fronted focus element col direttore ‘with the manager’ is about some unexpected and surprising information. Since mirative contexts can be out-of-the-blue contexts eliciting broad-focus sentences (as exemplified in (i)), the non-focal material is not necessarily given.

This type of fronting is not possible in Mandarin Chinese. By uttering (iia), the speaker intends to say that it is unexpected and surprising to fall in love with the boss. By contrast, fronting the focused lǎobǎn ‘boss’ as in (iib) results in the loss of the mirative meaning. The sentence (iib) can be uttered in a contrastive context in which there is another individual that she does not like. Finally, the closest example that we can come up with is shown in (iic), in which the focused element lǎobǎn ‘boss’ is uttered first, followed by an entire sentence including an in-situ focused lǎobǎn ‘boss’.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Bianchi, Valentina, Giuliano Bocci, and Silvio Cruschina. 2015. Focus fronting and its implicatures. In Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 2013: Selected Papers from ‘Going Romance’ Amsterdam 2013. Edited by Enoch O. Aboh, Jeannette Schaeffer and Petra Sleeman. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, Yuen Ren. 1968. A Grammar of Spoken Chinese. Berkeley: California University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen. 2008. Deconstructing the shi… de construction. The Linguistic Review 25: 235–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Bonnie H.-C. 1993. The Inflectional Structure of Mandarin Chinese. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Erteschik-Shir, Nomi. 2007. Information Structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grosu, Alexander. 2002. Strange relatives at the interface of two millennia. GLOT International 6: 145–67. [Google Scholar]

- Hole, Daniel. 2011. The deconstruction of Chinese shì…de clefts revisited. Lingua 121: 1707–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-T. James. 1982. Logical Relations in Chinese and the Theory of Grammar. Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.-T. James. 1988. Shuo shi he you [On shi and you]. Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology 59: 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.-T. James. 1989. Pro-drop in Chinese: A generalized control theory. In The Null Subject Parameter. Edited by Osvaldo Jaeggli and Kenneth Safir. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 185–214. [Google Scholar]

- Jackendoff, Ray. 1972. Semantics in Generative Grammar. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kayne, Richard S. 1994. The Antisymmetry of Syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. 2005. On Chinese Focus and Cleft Constructions. Doctoral dissertation, National Tsing-hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Hai-Ping. 2013. On the formation of Mandarin V de O focus clefts. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 4: 409–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, Shuxiang, ed. 2000. Xiandai hanyu babai ci [800 words of Modern Chinese]. Beijing: Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Victor Junnan, and Steven Zetao Xu. 2022. Xiàndài Hànyǔ Yíwèncí de Jùfǎ Céngjí Zài Tàn [On the Syntactic Hierarchy of Wh-words in Mandarin Chinese]. Yǔyánxué Lùncóng 1: 100–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Victor Junnan. 2015. Syntactic and Prosodic Marking of Contrastiveness in Spoken Chinese. In Information Structure and Spoken Language from a Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Edited by M. M. J. Fernandez-Vest and R. D. Van Valin, Jr. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Victor Junnan. 2017. Optional projections in the left-periphery in Mandarin Chinese. In Studies on Syntactic Cartography. Edited by Fuzhen Si. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press, pp. 216–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Victor Junnan. 2019a. Architecture of The Periphery in Chinese: Cartography and Minimalism. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Victor Junnan. 2019b. System repairing strategy at interface: Wh-in-situ in Mandarin Chinese. In Interface in Grammar. Edited by Jianhua Hu and Haihua Pan. [Language Faculty and Beyond (LFAB)]. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 133–66. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, Marie-Claude. 1979. Nominalization in Mandarin Chinese. Paris: Département de Recherches linguistiques, Université Paris 7. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, Waltraud, and John Whitman. 2008. Shi…de focus clefts in Mandarin Chinese. The Linguistic Review 25: 413–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Waltraud. 2015. New Perspectives on Chinese Syntax. [Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs 271]. Berlin: Mouton, De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Rooth, Mats. 1985. Association with Focus. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, D. T. 1994. The nature of Chinese emphatic sentence. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 3: 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyu, Shu-Ing. 2014. Topic and Focus. In The handbook of Chinese Linguistics. Edited by C.-T. Huang, Y.-H. Li and A. Simpson. West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 100–25. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Andrew, and Zoe Xiu-Zhi Wu. 2002. From D to T—Determiner incorporation and the creation of tense. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 11: 169–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, Andrew. 2003. On the status of modifying de and the structure of the Chinese DP. In On the Formal Way to Chinese Languages. Edited by Sze-Wing Tang and Chen-Sheng Luther Liu. Stanford: The Center for the Study of Language and Information, pp. 74–101. First published 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, Shou-Hsin. 1979. Remarks on cleft sentences in Chinese. Journal of Chinese Linguistics 7: 101–14. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Wal, Jenneke. 2016. Diagnosing Focus. Studies in Language 40: 259–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. 2004. Manifestation of informational focus. Lingua 114: 277–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Dexi. 1961. Shuo de [On de]. Zhongguo Yuwen [Studies of the Chinese Language] 12: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Dexi. 1978. ‘De’ zi jiegou he panduan ju [‘De’ construction and clefts]. Zhongguo Yuwen [Studies of the Chinese Language] 144: 23–27, 104–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zubizarreta, M., and Jean-Roger Vergnaud. 2006. Phrasal Stree and Syntax. Blackwell Companion to Syntax. Edited by M. Everaert. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 522–68. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).