Confronting Focus Strategies in Finnish and in Italian: An Experimental Study on Object Focusing

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i).

- Does the trigger for FF lie in the combination of multiple features, such as [Correction] and [Exhaustivity], within the same context?

- (ii).

- Do Exhaustive Operators, which convey an exhaustive import, thus increasing the degree of feature combination, have an impact on the realization of FF?

- (iii).

- Can the External Merge of the focused constituents within the vP phase play a role in (dis)favoring FF?

2. The Notion of Focus and Different Focus Types

| (1) | a. | [Mary]F likes Sue = ⟨λx [likes(x, s)], m⟩ |

| b. | Mary likes [Sue]F = ⟨λy [likes(m, y)], s⟩ |

| (2) | a. | ⟦[Mary]F likes Sue⟧f = {like(x, s)| xϵE}, where E is the domain of individuals. | |

| b. | ⟦Mary likes [Sue]F⟧f = {like(m, y)| yϵE} | (Rooth 1992, p. 76) | |

2.1. Corrective Focus

| (3) | a. | A: Yesterday, Jordan bought a blue car. |

| B: Really? Yesterday, I bought a redContrF car. | ||

| b. | A: For the picnic this afternoon, John is going to bring a cold salad. | |

| B: Really? Mary is going to bring a cold soupContrF. |

| (4) | A: John invited Lucy |

| B: ⟦He invited [Marina]CF⟧f = {invite(j, x)| xϵE} |

| (5) | For the picnic this afternoon, John is going to bring a cold salad. |

| A: ‘No, ~[ he’s going to bring a coldCF soup]. | |

| B: ‘No, ~[he’s going to bring a cold soupCF].’ |

2.2. Exhaustive Focus

| (6) | a. | [CP | Anna-lle | [IP | Mikko | anto-i | kukk-i-a]] | |

| Anna-ade | Mikko.nom | give-pst.3sg | flowers-pl-part | |||||

| ‘It was to Anna that Mikko gave flowers.’ | ||||||||

| b. | [IP | Mikko | anto-i | [VP | kukk-i-a | Anna-lle]] | ||

| Mikko.nom | give-pst.3sg | flowers-pl-part | Anna-ade | |||||

| ‘Mikko gave flowers to Anna.’ | ||||||||

3. Focus Strategies

3.1. Focus Fronting vs. Realization In Situ

3.1.1. Object Focus in Finnish: SVO vs. OSV

| (7) | a. | Liisa | rakasta-a | Martti-a. | (SVO) |

| Liisa.nom | love-3sg | Martti-part | |||

| ‘Liisa loves Martti.’ | |||||

| b. | Martti-a | rakasta-a | Liisa. | (OVS) | |

| Martti-part | love-3sg | Liisa | |||

| ’Liisa loves Martti.’ | |||||

| c. | Liisa | Martti-a | rakasta-a. | (SOV) | |

| Liisa.nom | Martti-part | love-3sg | |||

| ‘It is Liisa who loves Martti.’ | |||||

| d. | Martti-a | Liisa | rakasta-a. | (OSV) | |

| Martti-part | Liisa.nom | love-3sg | |||

| ‘It is Martti who Liisa loves.’ | |||||

| e. | Rakasta-a | Liisa | Martti-a. | (VSO) | |

| love-3sg | Liisa.nom | Martti-part | |||

| ‘Liisa does love Martti.’ | |||||

| f. | Rakasta-a | Martti-a | Liisa. | (VOS) | |

| love-3sg | Martti-part | Liisa.nom | |||

| Lit. ‘Loves Martti Liisa.’4 | |||||

| (8) | A: | Luule-n, | että | Liisa | rakasta-a | Pekka-a. |

| think-1sg | that | Liisa.nom | love-3sg | Pekka-part | ||

| ’I think Liisa loves Pekka.’ | ||||||

| B: | Ei, | Liisa/hän | rakasta-a | Martti-a. | ||

| no | Liisa/she.nom | love-3sg | Martti-part | |||

| ‘No, Liisa/she loves Martti.’ | ||||||

| (9) | Martti-a | Liisa | rakasta-a. |

| Martti-part | Liisa.nom | love-3sg | |

| ‘(It is) Martti (whom) Liisa loves.’ | |||

3.1.2. Object Focus in Italian: SVO vs. OVS

| (10) | a. | Alex | ha | scritto | una | mail. |

| Alex.nom | have.3sg | write.prt | an | email.acc | ||

| b. | Una | ha | scritto | Alex. | ||

| an | email.acc | have.3sg | write.prt | Alex.nom |

| (11) | A: | Alex | ha | comprato | una | moto. | ||

| Alex.nom | have.3sg | buy.prt | a | motorcycle.acc | ||||

| ‘Alex bought a motorcycle.’ | ||||||||

| B: | Una | bici | ha | comprato (, | non | una | moto). | |

| a | bike.acc | have.3sg | buy.prt | not | a | motorcycle.acc | ||

| ‘A bike he bought (, not a motorcycle).’ | ||||||||

3.2. Cleft Constructions

| (12) | È | un | libro | che | Tom | ha | letto. |

| be.3sg | a | book.acc | rel | Tom.nom | have.3sg | read.prt | |

| ‘It is a BOOK that Tom read.’ | |||||||

| (13) | a. | (Kyllä) | se | ole-n/on | minä, | joka | määrää/määrää-n. | |||

| emph | it.acc/nom11 | be-1sg/.3sg | I.nom | rel.nom | command.3sg/-1sg | |||||

| ‘It is me who commands.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Minä | se | ole-n/on, | joka | määrää/määrää-n. | |||||

| I.nom | it.acc/nom | be-1sg/.3sg | rel.nom | command.3sg/-1sg | ||||||

| ‘It is me who commands.’ | ||||||||||

| (14) | a. | Kyllä | se | on | kiusaaja | jo-ta | lyö-dään | takaisin. | ||

| emph | it.nom | be.3sg | bully.acc | rel-part | hit-pass | back | ||||

| ‘It is the bully who gets hit back.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Kyllä | se | on | jalostus-ta | jo-ta | ne | siellä | harrasta-a. | ||

| emph | it.nom | be.3sg | refinement-part | rel-part | they.nom | there | do-3sg | |||

| ‘It is refinement that they do there.’ | ||||||||||

3.3. Focus Markers and the Finnish Discourse Marker -hAn

| (15) | a. | Matti-han | ost-i | pyörä-n. | ||||||||

| Matti.nom-fm | buy-pst.3sg | bike-acc | ||||||||||

| ‘Matti bought a bike.’ | ||||||||||||

| b. | Tämä | kirja-han | on | hyvä. | ||||||||

| this.nom | book.nom-fm | be.3sg | good | |||||||||

| ‘This book is good.’ | ||||||||||||

| c. | Ohjee-n | mukaan-han | lääke | pitä-ä | otta-a | illa-lla. | ||||||

| instruction-gen | according-fm | medicine.acc | must-3sg | take-inf | evening-ade | |||||||

| ‘According to the instructions, the medicine must be taken in the evening.’ | ||||||||||||

| d. | Matti | ja | Liisa-han | ost-i-vat | möki-n. | |||||||

| Matti.nom | and | Liisa.nom-fm | buy-pst-3pl | cottage-acc | ||||||||

| ‘Matti and Liisa bought a cottage.’ | ||||||||||||

| (16) | a. | Liisa-han | ost-i | pyörä-n. | (SVO) |

| Liisa-fm | buy-pst.3sg | bike-acc | |||

| ‘Liisa bought a bike.’ | |||||

| b. | Liisa-han | ost-i | pyörä-n. | ||

| Liisa-fm | buy-pst.3sg | bike-acc | |||

| ‘Liisa bought a bike.’ | |||||

| c. | Liisa-han | ost-i | pyörä-n. | ||

| Liisa-fm | buy-pst.3sg | bike-acc | |||

| ‘It was Liisa who bought a/the bike.’ | |||||

| (17) | Liisa-han | se | ost-i | pyörä-n. |

| Liisa.nom-fm | espl.3sg | buy-pst.1sg | bike-acc | |

| ‘It was Liisa who bought a/the bike.’ | ||||

| (18) | a. | Pyörä-n-hän | ost-i | Liisa. | (OVS) |

| bike-acc-fm | buy-pst.3sg | Liisa.nom | |||

| ‘(It was) Liisa (who) bought the bike.’ | |||||

| b. | *Pyörän-hän osti Liisa. | ||||

| c. | *Pyörän-hän osti Liisa. | ||||

| (19) | a. | Liisa-han | pyörä-n | ost-i. | (SOV) |

| Liisa.nom-fm | bike-acc | buy-pst.3sg | |||

| ‘(It was) Liisa (who) bought the bike.15 | |||||

| b. | *Liisa-han pyörän ost-i. | ||||

| c. | *Liisa-han pyörän ost-i. | ||||

| (20) | a. | Pyörä-n-hän | Liisa | ost-i. | (OSV) |

| bike-acc-fm | Liisa.nom | buy-pst.3sg | |||

| ‘(It was) a/the bike (that) Liisa read.’ | |||||

| b. | *Pyörän-hän Liisa osti. | ||||

| c. | *Pyörän-hän Liisa osti. | ||||

| (21) | a. | Ost-i-han | Liisa | pyörä-n. | (VSO) |

| buy-pst.3sg-fm | Liisa.nom | bike-acc | |||

| ‘Liisa did buy a/the bike.’ | |||||

| b. | Osti-han Liisa pyörän. | ||||

| ‘Liisa bought a bike.’ | |||||

| c. | Osti-han Liisa pyörän. | ||||

| ‘Liisa bought a bike.’ | |||||

| (22) | a. | Peka-lle | selvi-si | että | Liisa-han | rakasta-a | Martti-a. | |

| Pekka-all | become.clear-pst.3sg | that | Liisa-fm | love-3sg | Martti-part | |||

| ‘It became clear to Pekka that Liisa loves Martti.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Pekka | taju-si, | että | Liisa-han | rakasta-a | Martti-a. | ||

| Pekka.nom | understand-pst.3sg | that | Liisa-fm | love-3sg | Martti-part | |||

| ‘Pekka understood that Liisa loves Martti.’ | ||||||||

| c. | *Mies, | jo-ta | Liisa-han | rakasta-a, | on | Martti. | ||

| man.nom | rel-part | Liisa-fm | love-3sg | be.3sg | Martti.acc | |||

3.4. Combination of Features and Focus Operators

3.4.1. The Exhaustive Operator Solo in Italian

| (23) | Va be’… forse | perché | escono | solo | in | Germania! | ||||||

| well | maybe | because | go out.3sg | only | in | Germany | ||||||

| ‘Well…. Maybe because they only come out in Germany!’ | ||||||||||||

| (24) | Non | riuscirei | a | fare | un | intero | programma | solo | sul | |||

| not | can.cond.1sg | to | do | a | whole | program | only | on.DET | ||||

| computer. | ||||||||||||

| computer | ||||||||||||

| ‘I would not be able to do a whole program only on the computer.’ | ||||||||||||

| (25) | a. | Va be’…forse | perché | escono | solo | in | Germania! (= (23)) | |

| b. | *Va be’…forse | perché | escono | solo | in | Germania, | ||

| well | maybe | because | go out.3sg | only | in | Germany, | ||

| ed | escono | solo | anche | in | Francia | |||

| and | go out.3sg | only | also | in | France | |||

| ‘*Well…. Maybe because they only come out in Germany, and they only come out in France too’ | ||||||||

| (26) | a. | Ho | visto | solo | Leo | in | biblioteca. |

| Have.1sg | seen | only | Leo | in | library | ||

| ‘I only saw Leo in the library.’ | |||||||

| b. | *Solo, ho visto Leo in biblioteca. | ||||||

| *Only, I saw Leo in the library. | |||||||

| c. | *Ho visto Leo in biblioteca, solo. | ||||||

| *I saw Leo in the library, only. | |||||||

| (27) | a. | Ho | visto | sempre | Leo | in | biblioteca. |

| Have.1sg | seen | always | Leo | in | library | ||

| ‘I always saw Leo in the library.’ | |||||||

| b. | Sempre, ho visto Leo in biblioteca. | ||||||

| ‘Always, I saw Leo in the library.’ | |||||||

| c. | Ho visto Leo in biblioteca, sempre | ||||||

| ‘I saw Leo in the library, always.’ | |||||||

| (28) | a. | Ho | visto | forse | Leo | in | biblioteca. |

| Have.1sg | seen | maybe | Leo | in | library | ||

| ‘I saw maybe Leo in the library.’ | |||||||

| b. | Forse, ho visto Leo in biblioteca. | ||||||

| ‘I maybe saw Leo in the library.’ | |||||||

| c. | Ho visto Leo in biblioteca, forse | ||||||

| ‘I saw Leo in the library, maybe.’ | |||||||

3.4.2. The Exhaustive Operator Vain in Finnish

| (29) | a. | Nä-i-n | vain | Leo-n | kirjasto-ssa. | |

| see-pst-1sg | only | Leo-acc | library-ine | |||

| ‘I only saw Leo in the library.’ | ||||||

| b. | *Vain näin Leon kirjastossa. | |||||

| c. | *Näin Leon vain kirjastossa. | |||||

| d. | *Näin Leon kirjastossa vain. | |||||

| (30) | A: | Mitkä kynät Marko otti penaalista? |

| ‘Which writing tools did Marko take out of the pencil case?’ | ||

| B: | Lyijykynän, kuulakärkikynän ja tussin. | |

| ‘A pencil, a ballpoint pen and a felt pen.’ | ||

| C: | Katso kuvaa! Hän otti vain kuulakärkikynän. | |

| ‘Look at the photo! He only took a ballpoint pen.’ |

4. Research Questions and the Experimental Test

- (i).

- Does the trigger for FF lie in the combination of multiple features, such as Correction and Exhaustivity, within the same context?

- (ii).

- Do Exclusive Operators, which convey an exhaustive import, thus increasing the degree of feature combination, have an impact on the realization of FF?

- (iii).

- Can the External Merge of the focused constituents within the vP phase play a role in (dis)favoring FF?

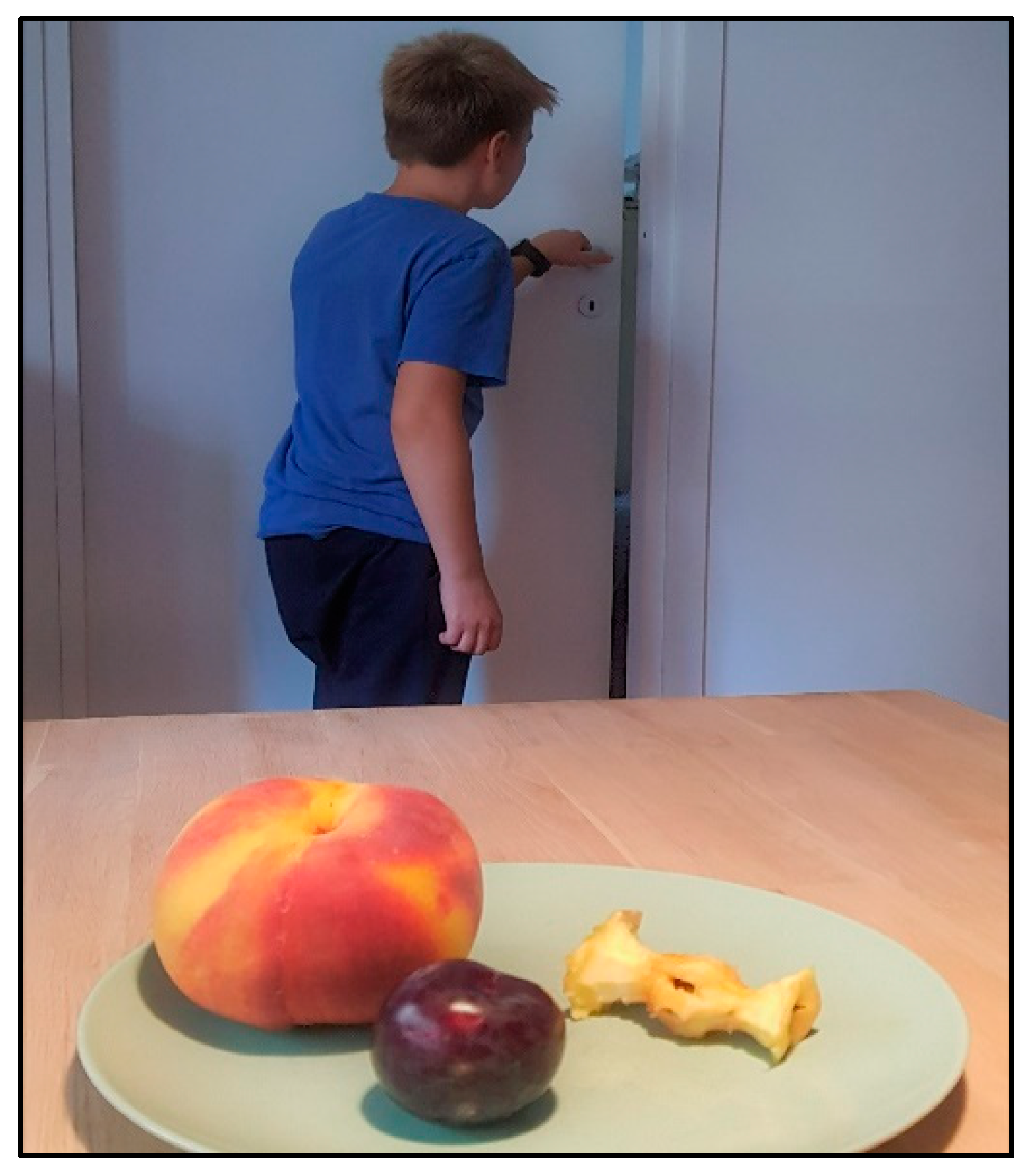

| (31) | A: | Mitkä hedelmät Lauri söi välipalaksi? | (FIN) |

| Quali frutti ha mangiato Leo per merenda? | (ITA) | ||

| Which fruit(s) did Lauri/Leo eat as a snack? | |||

| B: | Persikan, omenan ja luumun. | (FIN) | |

| La pesca, la mela e la prugna. | (ITA) | ||

| The/A peach, the/an apple and the/a plum. | |||

| C: | Katso kuvaa! Hän söi omenan. | (FIN) | |

| Guarda la foto! Ha mangiato la mela. | (ITA) | ||

| C’: | Katso kuvaa! Omenan hän söi. | (FIN) | |

| Guarda la foto! La mela ha mangiato. | (ITA) | ||

| C’’: | Katso kuvaa! Hänhän söi omenan. | (FIN) | |

| Guarda la foto! È la mela che ha mangiato. | (ITA) | ||

| Look at the picture! He ate the/an apple. |

| (32) | A: | Mitkä hedelmät Lauri söi välipalaksi? | (FIN) |

| Quali frutti ha mangiato Leo per merenda? | (ITA) | ||

| Which fruit(s) did Lauri/Leo eat as a snack? | |||

| B: | Persikan, omenan ja luumun. | (FIN) | |

| La pesca, la mela e la prugna. | (ITA) | ||

| The/A peach, the/an apple and the/a plum. | |||

| C: | Katso kuvaa! Hän söi vain omenan. | (FIN) | |

| Guarda la foto! Ha mangiato solo la mela. | (ITA) | ||

| Look at the picture! He only ate the/an apple. |

| (33) | A: | Millä leluilla Eino leikki? | (FIN) |

| Con quali giochi ha giocato Emilio? | (ITA) | ||

| What toys did Eino/Emilio play with? | |||

| B: | Rakennuspalikoilla, pallolla ja autolla. | (FIN) | |

| Con le costruzioni, con la palla e con le macchinine. | (ITA) | ||

| With (the) building blocks, with the/a ball and with (the) car(s). | |||

| C: | Katso kuvaa! Hän leikki pallolla. | (FIN) | |

| Guarda la foto! Ha giocato con la palla. | (ITA) | ||

| Look at the picture! He played with the/a ball. | |||

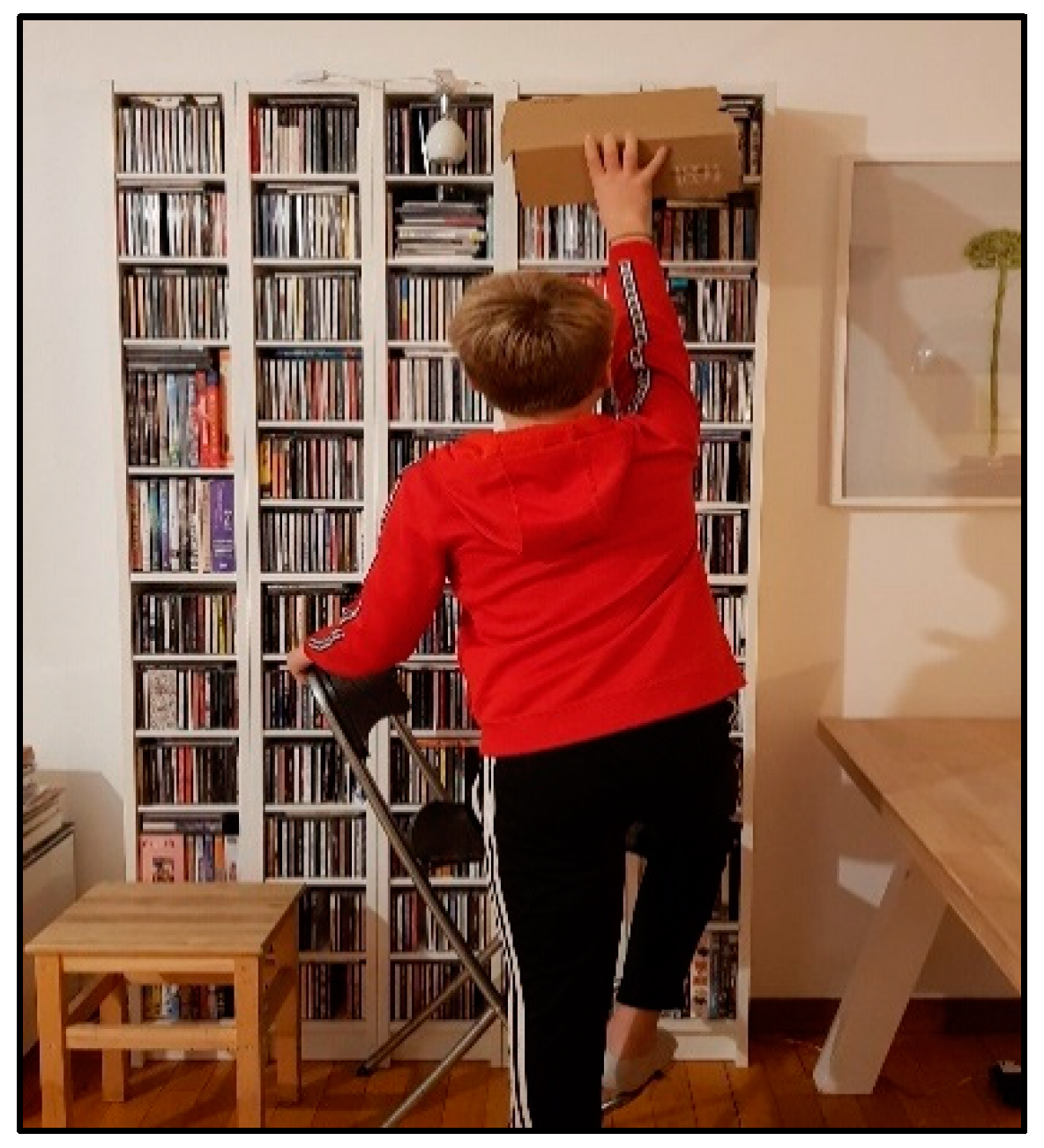

| (34) | A: | Mille huonekaluille Lauri nousi? | (FIN) |

| Su quali mobili è salito Carlo? | (ITA) | ||

| Which pieces of furniture did Lauri/Carlo climb on? | |||

| B: | Puujakkaralle, tuolille ja pöydälle. | (FIN) | |

| Sullo sgabello, sulla sedia e sul tavolo. | (ITA) | ||

| On the/a stool, (on) the/a chair and (on) the/a table. | |||

| C: | Katso kuvaa! Hän nousi tuolille. | (FIN) | |

| Guarda la foto! È salito sulla sedia. | (ITA) | ||

| Look at the picture! He climbed on the/a chair. |

5. Results and Analysis

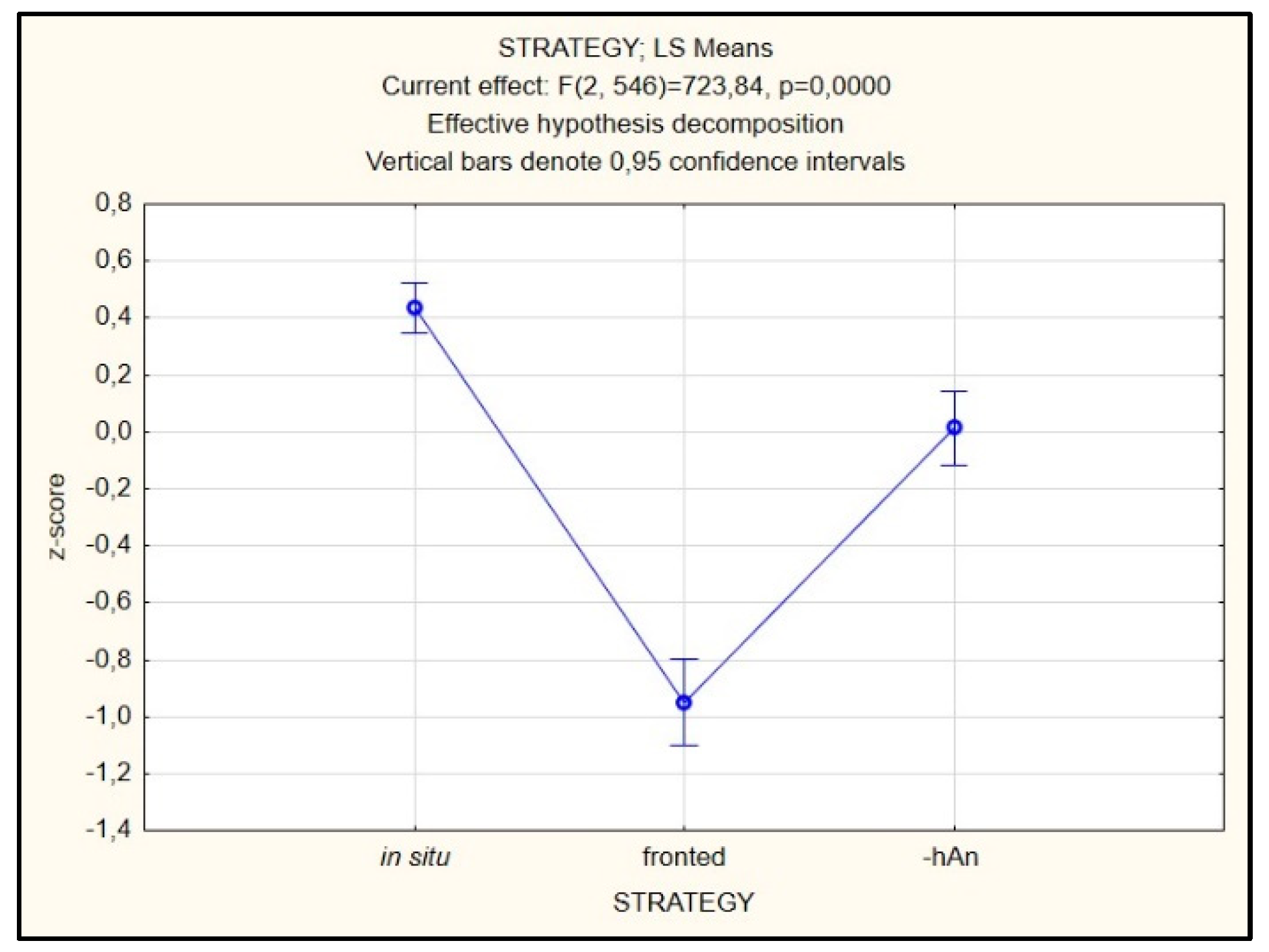

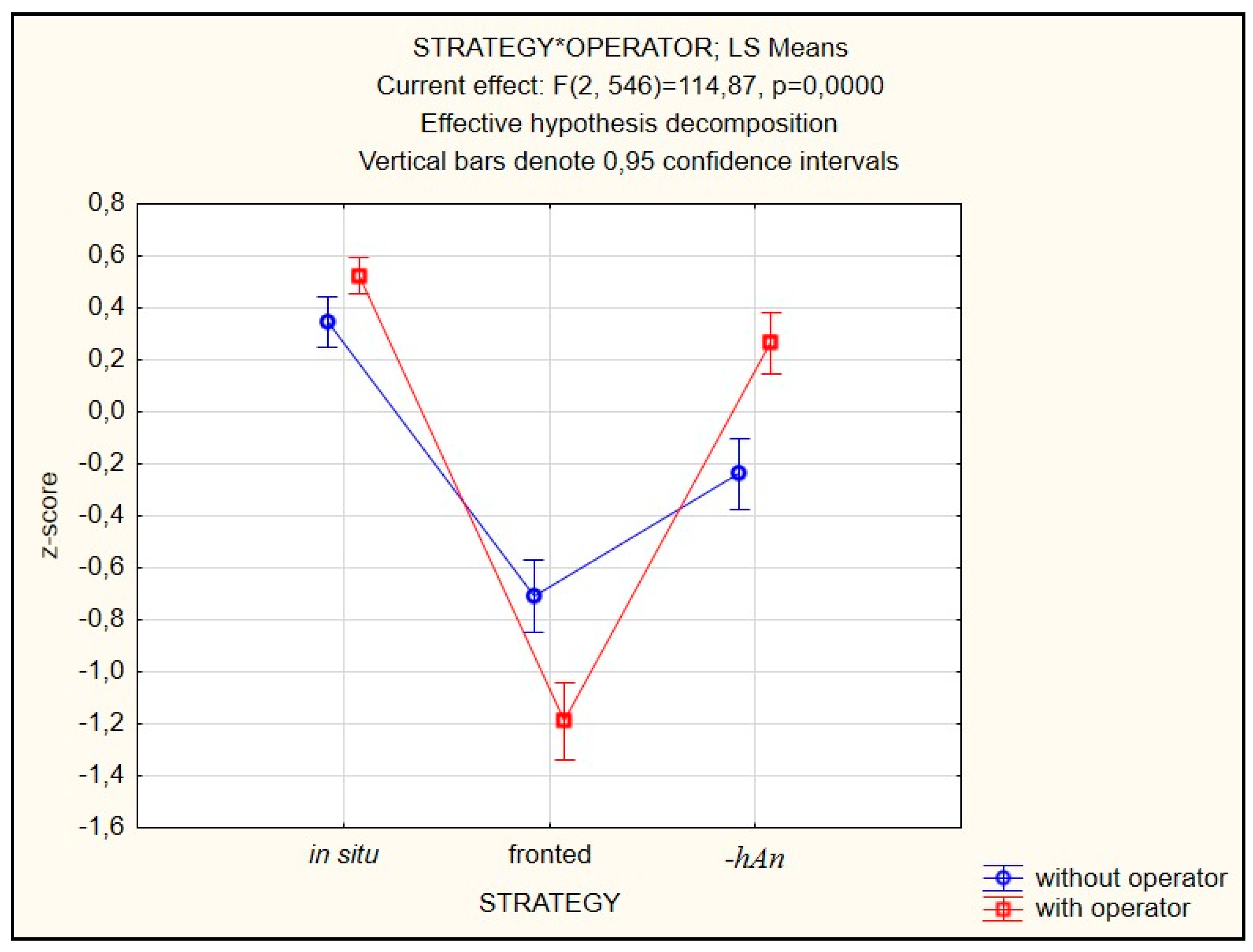

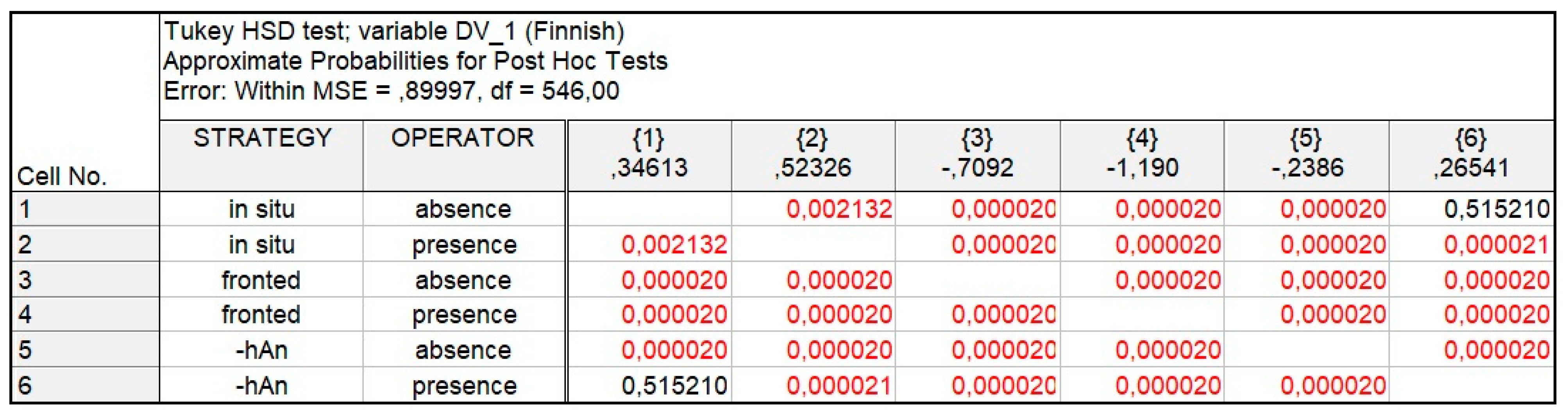

5.1. Finnish Data

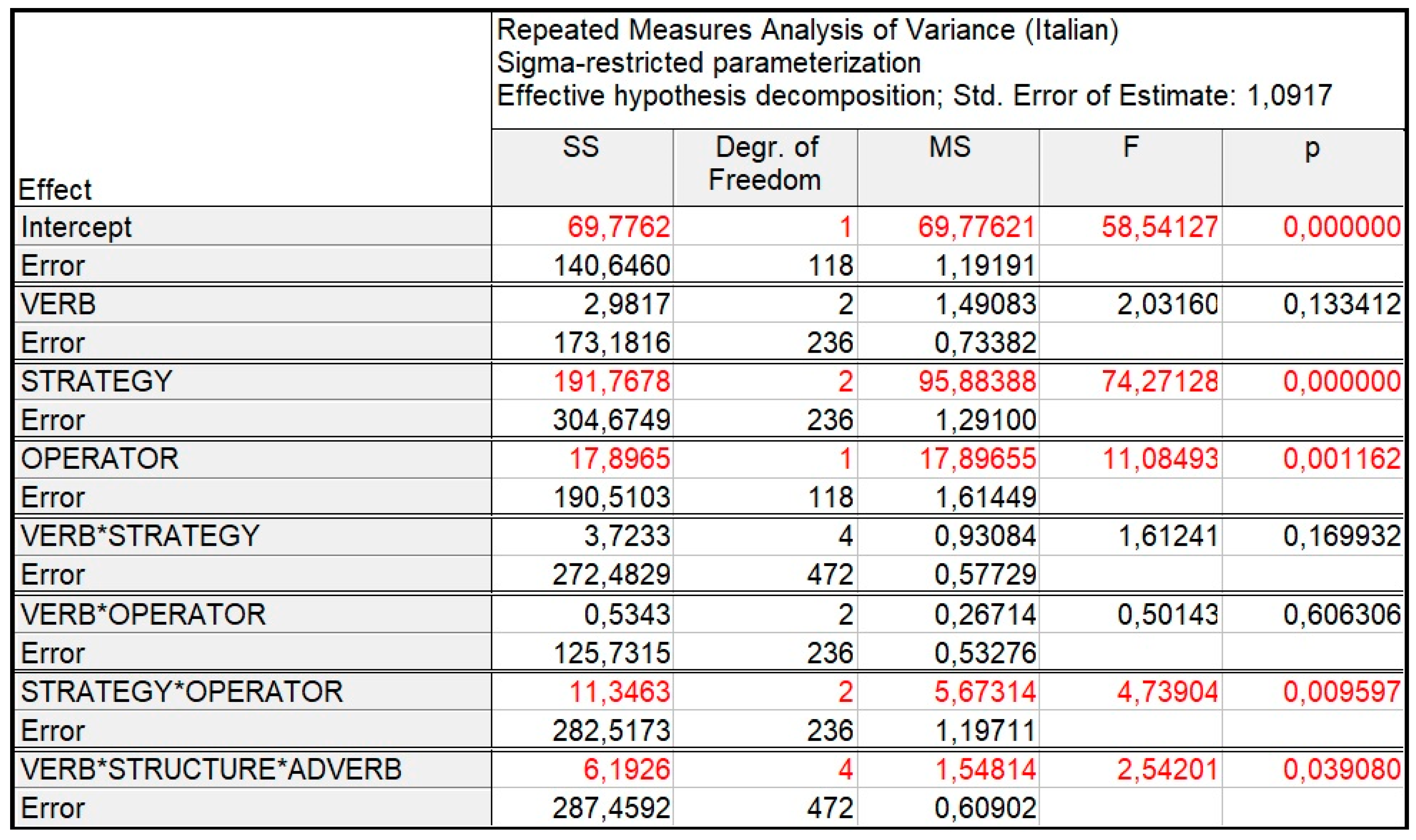

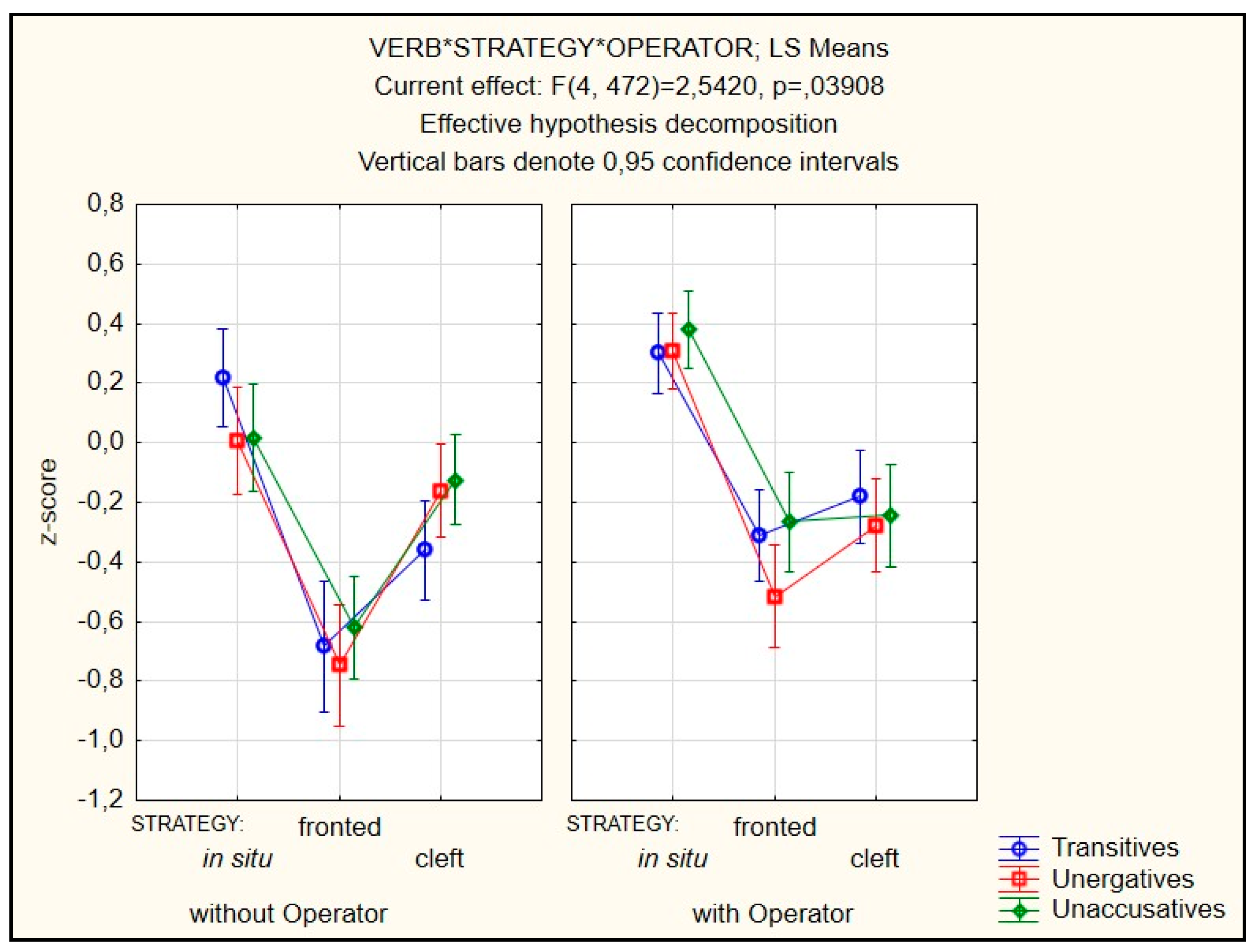

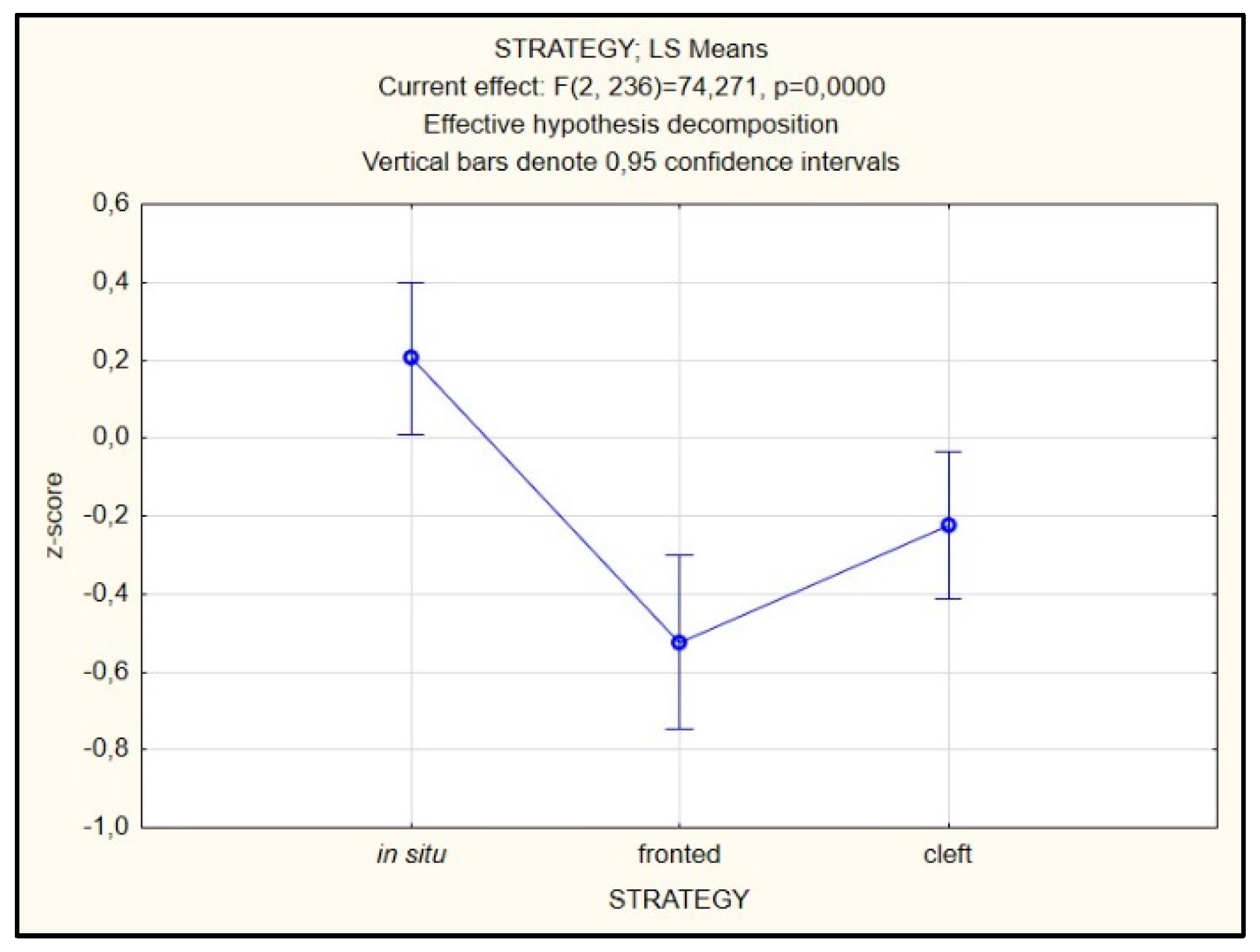

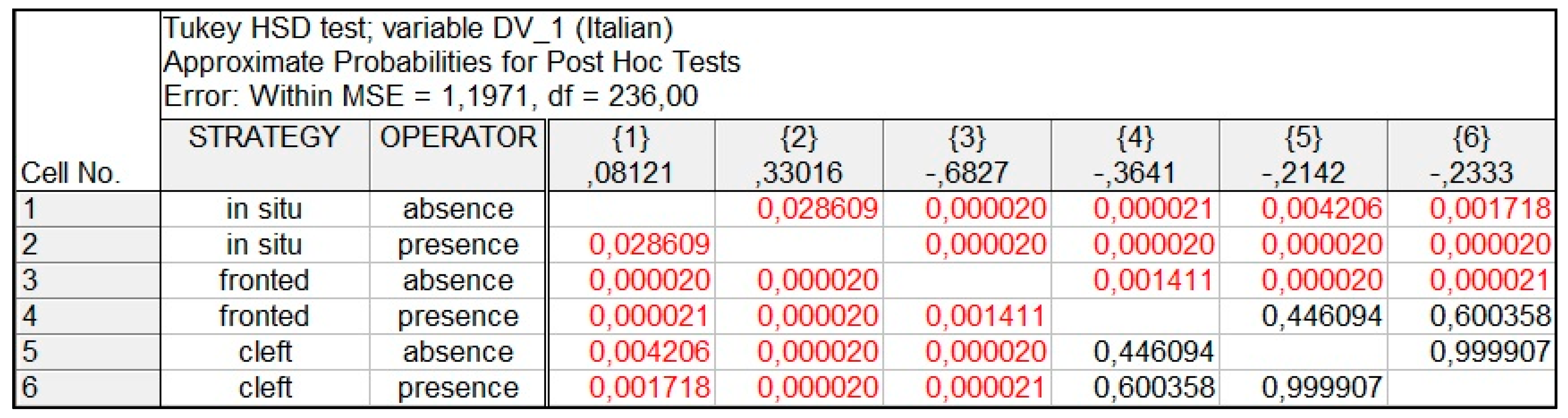

5.2. Italian Data

6. Conclusions

- (i).

- Does the trigger for FF lie in the combination of multiple features, such as [Correction] and [Exhaustivity], within the same context?

- (ii).

- Do Exhaustive Operators, which convey an exhaustive import, thus increasing the degree of feature combination, have an impact on the realization of FF?

- (iii).

- Can the External Merge of the focused constituents within the vP phase play a role in (dis)favoring FF?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In particular, Frascarelli and Ramaglia (2013a) concentrate on prosodic contours and show that the alternation between High and Low pitches in Topic constituents depends on the combination of the [givenness] feature which is assumed to be merged in the left periphery of the D-domain, with either [contrast] or [shift]. Since a Topic is [+given] by definition, to assume an ‘additional’ interpretation it must move to the Spec of other Topic projections, characterized by (and endowed with) a prosodic High (H*) feature. This allows a (basically low-toned) Topic to assume a marked intonation (whence the proposal that movement is triggered by “Information-Structure (IS) markedness”). |

| 2 | According to the authors, the difference between Italian and Hungarian can be derived from the fact that the Exhaustive Operator ‘associates’ with Focus in Hungarian and with Contrast in Italian. According to É. Kiss (1998), however, fronting in Hungarian is associated with Identification Focus (i.e., exhaustive) and not with mere Information Focus. |

| 3 | The abbreviations used in this paper are the following: acc (Accusative Case), ade (Adessive Case), all (Allative Case), CF (Corrective Focus), EF (Exhaustive Focus), FF (Focus Fronting), FM (Focus Marker), gen (Genitive Case), ill (Illative Case), ine (Inessive Case), inf (Infinitive), IS (Information Structure), m (Masculine), nom (Nominative Case), O (Object), obj (Objective Case (=Accusative or Partitive)), part (Partitive Case), pl (Plural), prt (Past Participle), pst (Past Tense), rel (Relative Pronoun), S (Subject), sg (Singular). |

| 4 | The VOS order only occurs in artistic expressions, such as songs and poems. |

| 5 | Partitive Case is one of the two Objective Cases in Finnish, the other one being the Accusative Case, and its use in these examples is conditioned by the aspectual character of the verb. The Partitive–Accusative Case alternation goes beyond the purpose of this work. For insight and details, the reader is referred to Kiparsky (1998); VISK (sct. 1234); Larjavaara (2019). |

| 6 | Mirative Focus expresses contrast against expectations. |

| 7 | Mono-clausal analyses of clefts were proposed within the generative framework in Akmajian (1970) and Emonds (1976). However, these approaches were thereafter abandoned in favor of a bi-clausal derivational analysis proposed in Chomsky (1977) and developed further in recent contributions (cf., among others, É. Kiss 1999; Frascarelli 2000b; Hedberg 2000; Belletti 2008; Frascarelli and Ramaglia 2013b, 2014). |

| 8 | |

| 9 | Frascarelli and Ramaglia (2013b) take the analysis further and, based on a syntax-prosody interface evidence, propose that the relative clause should be analysed as a Familiar Topic. |

| 10 | Based on corpus data of formal register (Eduskunta 2017), the frequency of occurrence of object clefting appears to be significantly lower than that of subjects, and specifically, 2 vs.49 occurrences, respectively, within a corpus of 22,458.581 words. |

| 11 | The syntactic functions (and Cases) of the constituents can be interpreted in different ways according to the verbal agreement. |

| 12 | For instance, this line of analysis is substantially supported by diachronic evidence in Afro-asiatic languages. As is shown in Puglielli and Frascarelli (2005), for instance, the Somali FM baa is derived from a cluster composed by the proto-Cushitic copula *ak, a 3sg subject clitic and an inflectional (tense) morpheme: (i) *ak + y + aa be 3sgm pres |

| 13 | The capital letter ‘A’ indicates the archigrapheme, which is realized as a or ä, according to vowel harmony. |

| 14 | The particle -hAn may convey different pragmatic information according to context, such as “a reminder of familiar information”, (cf. Hakulinen 1976, p. 58; Brattico et al. 2013), but this function will not be considered in the present study. |

| 15 | Finnish does not have articles, but in translation, the object ‘book’ bears the article ‘the’, as the constituent is situated between the Focus and the verb, an intermediate position that is dedicated to given constituents. The definitive article clearly shows that the referent is known to the interlocutors. |

| 16 | In (33), the three alternative Focus strategies tested (namely, in situ, fronting and -hAn/cleft constructions in C, C’, and C’’’, respectively), are shown together for clarity of exposition. In the test, items were presented with only one option at a time. For reasons of space, in the following examples only the in situ alternative is illustrated. |

| 17 | Specifically, (i) for transitive verbs: ottaa/prendere (‘to take’), kuvata/fotografare (‘to photograph’), syödä/mangiare (‘to eat’) and silittää/stirare (‘to iron’); (ii) for unaccusative verbs: käydä/andare (‘to go’), mennä läpi/passare per (‘to pass through’), kompastua/inciampare (‘to trip’) and nousta/salire (‘climb’); and (iii) for unergative verbs: leikkiä/giocare (‘to play’), lentää/volare (‘to fly’), osua (‘to hit’)/sparare (‘to shoot’) and vastata/rispondere (‘to answer’). |

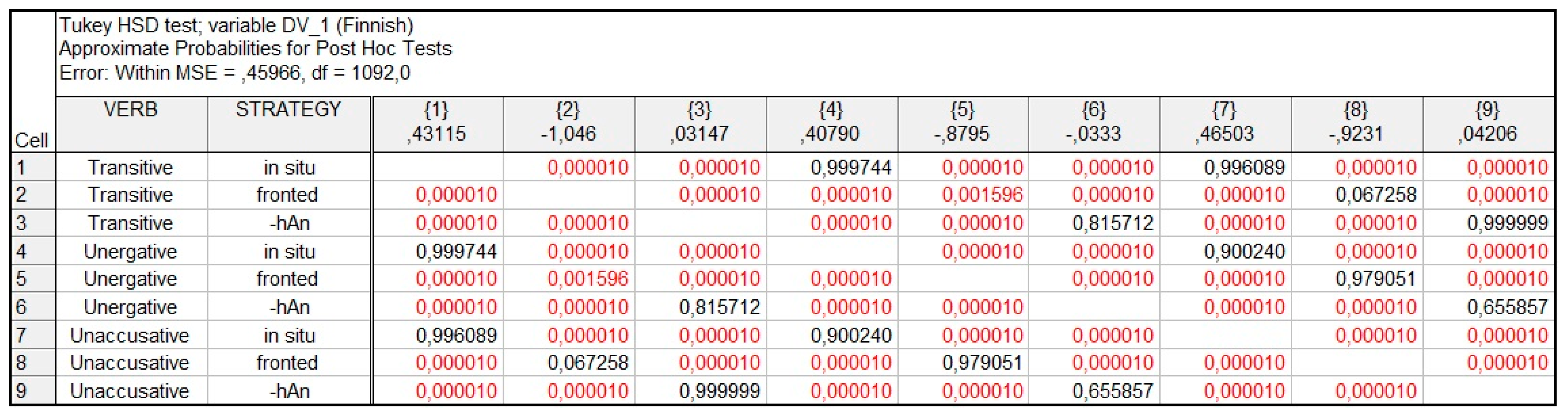

| 18 | Figure 4 shows, for each factor and for their interactions, the following data: Sum of squares (SS), namely, the sum of the squared deviations, representing the sum of the squared differences from the mean; Degree of Freedom, which is the number of values that may vary in a statistic, without violating any constraint; Mean squares (MS), namely, a representation of population variance, which is obtained by dividing the SS by the degrees of freedom; F-value (F); this is the result of the F-test calculated by dividing the MS value by the MS error and helps to check whether the variance between the means of two populations is significantly different; p-value (p), namely, the probability of getting a result at least as extreme as the one that was actually observed, given that the null hypothesis is true. Specifically, if the p-value is less than 0.05 the effect of the relevant factor or interaction is considered significant. In addition, the first line shows the value of the ‘Intercept’, which is the predicted value of the response when all predictors are 0, while under each factor an ‘Error’ line is showed, which represents the ‘unexplained random error’ found in the analysis. |

| 19 | For reasons of legibility, p-values in Figure 15 have been rounded off to 3 decimals. |

References

- Aboh, Enoc Oladé, Katarina Hartmann, and Malte Zimmerman, eds. 2007. Focus Strategies in African Languages. The Interaction of Focus and Grammar in Niger-Congo and Afro-Asiatic. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Adger, David, and Peter Svenonius. 2011. Features in minimalist syntax. In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Minimalism. Edited by Cedric Boeckx. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Akmajian, Adrian. 1970. Aspects of the Grammar of Focus in English. Ph.D. Dissertation, MIT, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis, and Elena Anagnostopoulou. 2004. Voice morphology in the causative-inchoative Alternation: Evidence for a non-unified structural analysis of unaccusatives. In The Unaccusativity Puzzle. Edited by Artemis Alexiadou, Elena Anagnostopoulou and Martin Everaert. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 114–36. [Google Scholar]

- Aller Media, Oy. 2014. Suomi 24 Virkkeet-Korpus (2016H2) [Tekstikorpus]. Kielipankki. Available online: http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:lb-2017021505 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Âmbar, Manuela. 1999. Aspects of the syntax of focus in Portuguese. In The Grammar of Focus. Edited by Georges Rebuschi and Laurice Tuller. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 23–53. [Google Scholar]

- Arnhold, Anja, and Aki-Juhani Kyröläinen. 2017. Modelling the interplay of multiple cues in prosodic focus marking. Laboratory Phonology 8: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avesani, Cinzia. 1999. Quantificatori, negazione costituenza sintattica. Costruzioni potenzialmente ambigue e il ruolo della prosodia. In Fonologia e morfologia dell’italiano e dei dialetti d’Italia. Atti del XXXI Congresso Internazionale di Studi della SLI. Edited by Paola Benincà, Alberto Mioni and Laura Vanelli. Roma: Bulzoni, pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver, David, and Brady Clark. 2003. Always and Only: Why not all Focus-Sensitive Operators are Alike. Natural Language Semantics 11: 323–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Sigfrid. 2016. Focus Sensitive Operators. In The Oxford Handbook of Information Structure. Edited by Caroline Féry and Shinichiro Ishihara. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 227–50. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, Adriana. 2004. Aspects of the Low IP Area. In The Structure of CP and IP. The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by Luigi Rizzi. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 16–51. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, Adriana. 2005. Answering with a cleft: The role of the Null-subject parameter and the vP periphery. In Contributions to the thirtieth “Incontro di Grammatica Generativa”. Edited by Laura Brugè, Giuliana Giusti, Nicola Munaro, Walter Schweikert and Giuseppina Turano. Venezia: Editrice Cafoscarina, pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Belletti, Adriana. 2008. Answering strategies: New information subjects and the nature of clefts. In Structures and Strategies. Edited by Adriana Belletti. London: Routledge, chp. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Valentina, and Giuliano Bocci. 2012. Should I Stay or Should I Go? Optional Focus Movement in Italian. Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics 9: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Valentina, and Mara Frascarelli. 2010. Is topic a root phenomenon? Iberia 2: 43–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Valentina, Giuliano Bocci, and Silvio Cruschina. 2015. Focus Fronting and its implicatures. In Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 2013. Edited by Enoch Aboh, Jeannette Schaeffer and Petra Sleeman. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Valentina, Giuliano Bocci, and Silvio Cruschina. 2016. Focus fronting, unexpectedness, and evaluative im-plicatures. Semantics and Pragmatics 9: 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, Valentina. 2013. On Focus movement in Italian. In Information Structure and Agreement. Edited by Victoria Camacho-Taboada, Ángel L. Jiménez-Fernández, Javier Martín-González and Mariano Reyes-Tejedor. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 194–215. [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore, Diane. 1987. Semantic Constraints on Relevance. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Brattico, Pauli, Saara Huhmarniemi, Jukka Purma, and Anne Vainikka. 2013. The Structure of Finnish CP and Feature Inheritance. Finno-Ugric Languages and Linguistics 2: 66–109. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, Michael, and Kriszta Szendrői. 2011. A kimerítő felsorolás értemezésűfókusz válasz. [Exhaustive focus is an answer]. In Új irányok Éseredmények a Mondattani Kutatásban Kiefer Ferenc 80. Születésnapja al-Kalmából. Edited by Huba Bartos. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó/Academic Press, vol. 23, Available online: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/~uczaksz/ (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Büring, Daniel, and Katharina Hartmann. 2001. The syntax and semantics of focus sensitive particles in German. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 19: 229–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büring, Daniel. 1999. Topic. In Focus, Linguistic Cognitive and Computational Perspectives. Edited by Peter Bosch and Rob van der Sandt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 142–65. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna. 2003. Stylistic Fronting in Italian. In Grammar in Focus. Festschrift for Christer Platzack. Edited by Lars-Olof Delsing, Cecilia Falk, Gunlög Josefsson and Halldór Á. Sigurðsson. Lund: Wallin and Dalholm, pp. 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, Noam. 1977. On WH-movement. In Formal Syntax. Edited by Peter W. Culicover, Thomas Wasow and Adrian Akmajian. New York: Academic Press, pp. 71–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cinque, Guglielmo, and Luigi Rizzi. 2008. The cartography of syntactic structures. Studies. Linguistics 2: 42–58. [Google Scholar]

- Coppock, Elizabeth, and Laura Staum. 2004. Origin of the English Double-Is Construction. Available online: https://bibbase.org/network/publication/coppock-staum-originoftheenglishdoubleisconstruction-2004. (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Cruschina, Silvio. 2011. Fronting, dislocation and the syntactic role of discourse-related features. Linguistic Variation 11: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruschina, Silvio. 2012. Discourse-Related Features and Functional Projections. New York /Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cruschina, Silvio. 2016. Information and discourse structure. In The Oxford Guide to the Romance languages. Edited by Adam Ledgeway and Martin Maiden. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 596–608. [Google Scholar]

- Cruschina, Silvio. 2019. L’anteposizione focale: Contrasto e i tipi di focus. In Per una prospettiva funzionale sulle costruzioni sintatticamente marcate. Special issue of Neuphilologische Mittei-lungen. Edited by Anna Maria De Cesare and Mervi Helkkula. Helsinki: Neuphilologischer Verein, pp. 247–267. [Google Scholar]

- Cruschina, Silvio. 2021. The greater the contrast, the greater the potential. On the effect of Focus in syntax. Glossa: A journal of general linguistics 6: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Farra, Chiara. 2018. Towards a Fine-Grained Theory of Focus. Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie Occidentale 52: 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- De Cesare, Anna-Maria, and Davide Garassino. 2015. On the status of exhaustiveness in cleft sentences: An empirical and cross-linguistic study of English also-/only-clefts and Italian anche-/solo-clefts. Folia Linguistica 49: 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cesare, Anna-Maria. 2017. Cleft constructions. In Manual of Romance Morphosyntax and Syntax. Edited by Andreas Dufter and Elisabeth Stark. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 536–68. [Google Scholar]

- Delfitto, Denis, and Gaetano Fiorin. 2015. Exhaustivity Operators and Fronted Focus in Italian. In Structures, Strategies and Beyond. Studies in Honour of Adriana Belletti. Edited by Elsa Di Domenico, Cornelia Hamann and Simona Matteini. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 163–80. [Google Scholar]

- Dikken, Marcel Den, André Meinunger, and Chris Wilder. 2000. Pseudoclefts and ellipsis. Studia Linguistica 54: 41–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- É. Kiss, Katalin. 1998. Identificational Focus versus Information Focus. Language 74: 245–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- É. Kiss, Katalin. 1999. The English cleft construction as a focus phrase. In Boundaries of Morphology and Syntax. Edited by Lunella Mereu. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 217–30. [Google Scholar]

- Eduskunta. 2017. Eduskunnan Täysistunnot, Korp-Version of Kielipankki 1.5 [Text Corpus]. Kielipankki. Available online: http://urn.fi/urn:nbn:fi:lb-2019101621 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Emonds, John. 1976. A Transformational Approach to English Syntax: Root, Structure-Preserving, and Local Transformations. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, Irene. 2009. Verbs, Subjects and Stylistic Fronting. Ph.D. thesis, University of Siena, Siena, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, Mara, and Francesca Ramaglia. 2013a. Phasing contrast at the interfaces. In Information Structure and Agreement. Edited by Victoria Camacho-Taboada, Ángel L. Jiménez-Fernández, Javier Martín-González and Mariano Reyes-Tejedor. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 55–82. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, Mara, and Francesca Ramaglia. 2013b. Pseudoclefts at the Syntax-Prosody-Discourse Interface. In The Structure of Clefts. Edited by Katherina Hartmann and Tonjes Veenstra. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 97–138. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, Mara, and Francesca Ramaglia. 2014. The interpretation of clefting (a)symmetries between Italian and German. In Romance Languages and Linguistic Theory 2012. Selected Papers from ‘Going Romance’ Leuven 2012 [RLLT 6]. Edited by Karen Lahousse and Stefania Marzo. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, Mara, and Roland Hinterhölzl. 2007. Types of topics in German and Italian. In On Information Structure, Meaning and Form. Edited by Kerstin Schwabe and Susanne Winkler. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 87–116. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, Mara, and Tania Stortini. 2019. Focus constructions, verb types and the SV/VS order in Italian: An ac-quisitional study from a syntax-prosody perspective. Lingua 227: 102690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frascarelli, Mara. 2000a. The Syntax-Phonology Interface in Focus and Topic Constructions in Italian. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory Series Nr. 50. Dordrecht: Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, Mara. 2000b. Frasi Scisse e ‘Small Clauses’: Un’Analisi dell’Inglese. Lingua e Stile XXXV: 417–46. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, Mara. 2004. L’interpretazione del Focus e la portata degli operatori sintattici. In Il Parlato Italiano. Atti del Convegno Nazionale. Edited by Federico Albano Leoni, Franco Cutugno, Massimo Pettorino and Renata Savy. Naples: M. D’Auria Editore–CIRASS, p. B06. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, Mara. 2007. Subjects, Topics and the Interpretation of Referential pro. An interface approach to the linking of (null) pronouns. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 25: 691–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frascarelli, Mara. 2010. Narrow Focus, Clefting and Predicate Inversion. Lingua 120: 2121–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frascarelli, Mara. 2017. Dislocations and Framings. In Manual of Romance Morphosyntax and Syntax. Edited by Andreas Dufter and Elisabeth Stark. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 472–510. [Google Scholar]

- Frascarelli, Mara. 2018. The interpretation of pro in consistent and partial NS languages: A comparative interface analysis. In Null-Subjects in Generative Grammar. A Synchronic and Diachronic Perspective. Edited by Federica Cognola and Joan Casalicchio. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 211–39, Part IIB, chp. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Melanie. 1997. Focus and Copular Constructions in Hausa. Ph.D. thesis, SOAS, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Haegeman, Liliane. 2004. Topicalization, CLLD and the left periphery. ZAS Working Papers in Linguistics 35: 157–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakulinen, Auli, Fred Karlsson, and Maria Vilkuna. 1980. Suomen Tekstilauseiden Piirteitä: Kvantitatiivinen Tutkimus. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. [Google Scholar]

- Hakulinen, Auli. 1976. Reports on Text Linguistics: Suomen Kielen Generatiivista Lauseoppia 2. Turku: Åbo Akademi. [Google Scholar]

- Hale, Samuel, and Jay Keyser. 1993. Prolegomenon to a Theory of Argument Structure. Language 81: 248–51. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, Michael A. K. 1967. Notes on Transitivity and Theme in English: Part II. Journal of Linguistics 3: 199–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedberg, Nancy. 2000. The referential status of clefts. Language 76: 891–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heggie, Lorie. 1993. The range of null operators: Evidence from clefting. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 11: 45–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herburger, Elena. 2000. What Counts: Focus and Quantification. Linguistic Inquiry Monograph. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg, Anders, and Urpo Nikanne. 2002. Expletives, Subjects and Topics in Finnish. In Subjects, Expletives, and the EPP. Edited by Peter Svenonius. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 71–105. [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg, Anders. 2000. Scandinavian Stylistic Fronting. How any category can become an expletive. Linguistic Inquiry 31: 445–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, Anders. 2005. Stylistic fronting. In The Blackwell Companion to Syntax. Edited by Martin Everaert, Henk van Riemsdijk, Rob Goedemans and Bart Hollebrandse. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 530–63. [Google Scholar]

- Jackendoff, Ray. 1972. Semantic Interpretation in Generative Grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Joachim. 1983. Fokus und Skalen: Zur Syntax und Semantik der Gradpartikeln im Deutschen. Linguistische Arbeiten Band 138. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Fernández, Ángel L. 2015a. When focus goes wild: An empirical study of two syntactic positions for infor-mation Focus. Linguistics Beyond and Within 1: 119–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Fernández, Ángel L. 2015b. Towards a typology of focus: Subject position and microvariation at the dis-course-syntax interface. Ampersand: An International Journal of General and Applied Linguistics 2: 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Fernández, Ángel L., and Shigeru Miyagawa. 2014. A feature-inheritance approach to root phenomena and parametric variation. Lingua 145: 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Michael A. 2013. Fronting, focus and illocutionary force in Sardinian. Lingua 134: 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, Elsi. 2000. The discourse functions and syntax of OSV word order in Finnish. In The Proceedings from the Main Session of the Chicago Linguistic Society’s Thirty-Sixth Meeting. Edited by Arika Okrent and John Boyle. Chicago, IL: Chicago Linguistic Society, vol. 36.1, pp. 179–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, Elsi. 2006. Negation and the left periphery in Finnish. Lingua 116: 314–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karttunen, Frances. 1974. More Finnish Clitics: Syntax and Pragmatics. Mimeo: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karttunen, Frances. 1975. The syntax and pragmatics of the Finnish clitic-han. Texas Linguistic Forum 1: 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kiparsky, Paul. 1998. Partitive case and aspect. In Projecting from the Lexicon. Edited by Miriam Butt and Wilhelm Geuder. Stanford: CSLI, pp. 265–307. [Google Scholar]

- Klok, Vander, Heather Goad Jozina, and Michael Wagner. 2018. Prosodic focus in English vs. French: A scope account. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics 3: 71. [Google Scholar]

- Krifka, Manfred. 1992. A compositional semantics for multiple focus. In Informationsstruktur und Grammatik. Edited by Joachim Jacobs. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, pp. 127–58. [Google Scholar]

- Krifka, Manfred. 2007. Basic Notions of Information Structure. In Interdisciplinary Studies on Information Structure. Edited by Caroline Féry and Manfred Krifka. Potsdam: ISIS, Universitätverlag Potsdam, pp. 13–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht, Knud. 1994. Informaction Structure and Sentence Form: Topic, Focus and the Mental Representation of Dis-Course Elements. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lambrecht, Knud. 2001. A Framework for the Analysis of Cleft Constructions. Linguistics 39: 463–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larjavaara, Matti. 2019. Partitiivin Valinta. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, Richard K. 1988. On the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry 19: 335–91. [Google Scholar]

- Leino, Pentti. 1982. Suomen Kielen Lohkolause. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. [Google Scholar]

- Leonetti, Manuel, and Victoria Escandell. 2009. Fronting and verum-focus in Spanish. In Focus and Background in Romance Languages. Edited by Andreas Dufter and Daniel Jacob. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 155–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ler, Vivien. 2006. A relevance-theoretic approach to discourse particles in Singapore English. In Approaches to Discourse Particles. Edited by Kerstin Fischer. Amsterdam and Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 149–66. [Google Scholar]

- Maling, Joan. 1980. Inversion in embedded clauses in Modern Icelandic. In Modern Icelandic Syntax. Edited by Joan Maling and Annie Zaenen. Leiden: Brill, pp. 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Molnár, Valeria. 2002. Contrast in a contrastive perspective. In Information Structure in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective. Edited by Hilde Hasselgård, Stig Johansson, Bergljot Behrens and Cathrine Fabricius-Hansen. Amsterdam and New York: Rodopi, pp. 147–61. [Google Scholar]

- Molnár, Valeria. 2006. On different kinds of contrast. In The Architecture of Focus. Edited by Valeria Molnár and Susanne Winkler. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 197–233. [Google Scholar]

- Molnár, Valeria. 2017. Stylistic Fronting and Discourse. Florida Linguistics Papers 4: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Neeleman, Ad, Elena Titov, Hans van de Koot, and Reiko Vermeulen. 2009. A syntactic typology of topic, focus and contrast. In Alternatives to Cartography. Edited by Joan van Craenenbroeck. Berlin: Mouton del Gruyter, pp. 15–51. [Google Scholar]

- Nevis, Joel Ashmore. 1986. Finnish Particle Clitics and General Clitic Theory. Columbus: Ohio State University, Department of Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, Dennis. 2009. Stylistic Fronting as remnant movement. Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 83: 141–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomäki, Jennimaria. 2013. Exploring possibilities for a syntactic account for the Finnish -han enclitic. In UGA Working Papers in Linguistics. Athens: The Linguistics Society at UGA. [Google Scholar]

- Palomäki, Jennimaria. 2016. The Pragmatics and Syntax of the Finnish -han Particle Clitic. Ph.D. thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Partee, Barbara H. 1991. Topic, focus and quantification. In SALT I: Proceedings of the First Annual Conference on Semantics and Linguistic Theory 1991. Edited by Steven Moore and Adam Zachary Wyner. Ithaca: CLC Publications, Department of Linguistics, Cornell University, pp. 159–187. [Google Scholar]

- Penttilä, Aarni. 1957. Suomen Kielioppi. Helsinki: WSOY. [Google Scholar]

- Platzack, Christer. 2009. Old wine in new barrels. The edge feature in C, topicalization and Stylistic Fronting. Paper given at the “Maling Seminar. Ráðstefna til heiðurs Joan Maling 30” at the University Iceland. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, Christopher. 2005. The Logic of Conventional Implicatures. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, Christopher. 2007. Conventional implicatures, a distinguished class of meanings. In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Interfaces. Edited by Gillian Ramchand and Charles Reiss. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 475–501. [Google Scholar]

- Puglielli, Annarita, and Mara Frascarelli. 2005. The Focus System in Cushitic Languages. In Proceedings of the 10th Hamito-Semitic Congress. Afroasiatic Linguistics (Quaderni di Semitistica 23). Edited by Pelio Fronzaroli and Paolo Marrassini. Florence: University of Florence Press, pp. 333–58. [Google Scholar]

- Repp, Sophie. 2010. Defining ‘contrast’ as an information-structural notion in grammar. Lingua 120: 1333–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the Left Periphery. In Elements of Grammar. Handbook in Generative Syntax. Edited by Liliane Haegeman. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 281–337. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 2001. On the position Int(errogative) in the left periphery of the clause. In Current Studies in Italian Syntax. Essays offered to Lorenzo Renzi. Edited by Guglielmo Cinque and Giampaolo Salvi. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 287–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 2004. Locality and Left Periphery. In Structures and Beyond. The Cartography of Syntactic Structures. Edited by Adriana Belletti. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 223–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 2006. On the form of chains: Criterial positions and ECP effects. In Wh-Movement: Moving on. Edited by Lisa Lai-Shen Cheng and Norbert Corver. Cambridge: MIT Press, pp. 97–134. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, Luigi. 2018. Intervention effects in grammar and language acquisition. Probus 30: 339–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Craig. 2012. Information Structure in Discourse: Towards an Integrated Formal Theory of Pragmatics. Semantics and Pragmatics 5: 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggia, Carlo Enrico. 2008. Frasi Scisse in italiano e in francese orale: Evidenze dal C-ORAL-ROM. Cuadernos de Filología Italiana 15: 9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rooth, Mats. 1992. A Theory of Focus Interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 75–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooth, Mats. 1996. Focus. In The Handbook of Contemporary Semantic Theory. Edited by Shalom Lappim. Cambridge: Blackwell Reference, pp. 271–297. [Google Scholar]

- Samek-Lodovici, Vieri. 2018. Contrast, Contrastive Focus, and Focus Fronting. UCL Working Papers in Linguistics, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzschild, Roger. 1997. Why Some Foci Must Associate. Ms. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/62286570/Why_Some_Foci_Must_Associate_1 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Skopeteas, Stavros, and Gisbert Fanselow. 2010. Focus types and argument asymmetries. A cross-linguistic study in language production. In Comparative and Contrastive Studies of Information Structure. Edited by Carsten Breul and Edvard Göbbel. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 169–98. [Google Scholar]

- Skopeteas, Stavros, and Gisbert Fanselow. 2011. Focus and the exclusion of alternatives: On the interaction of syntactic structure with pragmatic inference. Lingua 121: 1693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleeman, Petra. 2013. Italian clefts and the licensing of infinitival subject relatives. In The Structure of Clefts. Edited by Katherina Hartmann and Tonjes Veenstra. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 319–42. [Google Scholar]

- Smeets, Liz, and Michael Wagner. 2018. Reconstructing the syntax of focus operators. Semantics and Pragmatics 11: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, Dan, and Deirdre Wilson. 1986. Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford and Cambridge: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Sulkala, Helena, and Merja Karjalainen. 1992. Finnish. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Suomi, Kari, Juhani H. Toivanen, and Riikka Ylitalo. 2008. Finnish Sound Structure Phonetics, Phonology, Phonotactics and Prosody. Oulu: University of Oulu. [Google Scholar]

- Szabolcsi, Anna. 1981. Compositionality in Focus. Acta Linguistica Societatis Linguistice Europaeae 15: 141–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, Martti, and Juhani Järvikivi. 2007. Focus in production: Tonal shape, intensity and word order. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 121: EL55–EL61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Välimaa-Blum, Riitta. 1987. The discourse function of the Finnish clitic -han: Another look. The Nordic Languages and Modern Linguistics 6: 471–81. [Google Scholar]

- Välimaa-Blum, Riitta. 1993. A pitch accent analysis of intonation in Finnish. Ural-Altaische Jahrbucher 12: 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Vallduví, Enric, and Maria Vilkuna. 1998. On rheme and contrast. In The Limits of Syntax. Edited by Peter W. Culicover and Louise McNally. San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 79–108. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leusen, Noor. 2004. Incompatibility in context. A diagnosis of correction. Journal of Semantics 21: 415–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanrell, Maria del Mar, and Olga Fernández-Soriano. 2013. Variation at the interfaces in Ibero-Romance. Catalan and Spanish prosody and word order. Catalan Journal of Linguistics 12: 253–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkuna, Maria. 1989. Free Word Order in Finnish: Its Syntax and Discourse Functions. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kir-jallisuuden Seura. [Google Scholar]

- Vilkuna, Maria. 1995. Discourse configurationality in Finnish. In Discourse Configurational Languages. Edited by Katalin É Kiss. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 244–68. [Google Scholar]

- VISK = Hakulinen, Auli, Maria Vilkuna, Riitta Korhonen, Vesa Koivisto, Tarja Riitta Heinonen, and Irja Alho. 2004. ISO Suomen Kielioppi. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Available online: http://scripta.kotus.fi/visk (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- von Stechow, Arnim. 1981. Topic, Focus, and Local Relevance. In Crossing the Boundaries in Linguistics. Edited by Wolfgang Klein and Willem Levelt. Dordrecht: Reidel, pp. 95–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ylinärä, Elina. 2021. Word Order and Focus in Finnish Finite Clauses. An Overview of Syntactic Theories from a Formal Perspective. Studi Finno-Ugrici 1: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zubizarreta, María Luisa. 1998. Prosody, Focus and Word Order. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

| Condition | Strategy | Operator | Verb |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | in situ | absence | transitive |

| 2 | in situ | presence | transitive |

| 3 | fronted | absence | transitive |

| 4 | fronted | presence | transitive |

| 5 | cleft/-hAn | absence | transitive |

| 6 | cleft/-hAn | presence | transitive |

| 7 | in situ | absence | unergative |

| 8 | in situ | presence | unergative |

| 9 | fronted | absence | unergative |

| 10 | fronted | presence | unergative |

| 11 | cleft/-hAn | absence | unergative |

| 12 | cleft/-hAn | presence | unergative |

| 13 | in situ | absence | unaccusative |

| 14 | in situ | presence | unaccusative |

| 15 | fronted | absence | unaccusative |

| 16 | fronted | presence | unaccusative |

| 17 | cleft/-hAn | absence | unaccusative |

| 18 | cleft/-hAn | presence | unaccusative |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ylinärä, E.; Carella, G.; Frascarelli, M. Confronting Focus Strategies in Finnish and in Italian: An Experimental Study on Object Focusing. Languages 2023, 8, 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010032

Ylinärä E, Carella G, Frascarelli M. Confronting Focus Strategies in Finnish and in Italian: An Experimental Study on Object Focusing. Languages. 2023; 8(1):32. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010032

Chicago/Turabian StyleYlinärä, Elina, Giorgio Carella, and Mara Frascarelli. 2023. "Confronting Focus Strategies in Finnish and in Italian: An Experimental Study on Object Focusing" Languages 8, no. 1: 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010032

APA StyleYlinärä, E., Carella, G., & Frascarelli, M. (2023). Confronting Focus Strategies in Finnish and in Italian: An Experimental Study on Object Focusing. Languages, 8(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8010032