Abstract

This paper reports on a literary corpus study of four grammatical tenses across four European languages. The corpus consists of a selection of eight chapters from Javier Marías’s Spanish novel Así empieza lo malo ‘Thus bad begins’, and its translations to English, Dutch, and French. We annotated 1579 verb forms in the Spanish source text for tense, and, subsequently, their translations in the other languages, distinguishing between two registers within the novel, i.e., dialogue and narration. We found that the vast majority of the Spanish tenses are translated one-to-one to their counterparts in the three languages, especially in narration. In dialogue, we found several deviations, which we could partially account for within an Optimality Theoretic approach by appealing to the notion of markedness along two different typological dimensions, namely, tense (present versus past) and aspect (imperfective versus perfective).

Keywords:

literary corpus; grammatical tenses; present perfect; simple past; narration; dialogue; markedness 1. Introduction

This paper investigates how four grammatical tenses in a Spanish novel having a first-person narrator are translated to English, Dutch, and French. In particular, we focus on the different distributions between present perfect and simple past, as these may compete with each other to express past eventualities (de Swart 2007; Schaden 2009; Van der Klis et al. 2021).

We use the Reichenbachian notions of E for eventuality, S for speech time, and R for reference point or, perhaps more appropriately, viewpoint. Note that we use E for eventuality rather than event, in order to include events as well as states (Bach 1986). Reichenbach (1947) illustrates the distinction between E and R with the English sentence Peter had gone, where R is situated between E (Peter went) and S, and has to be provided by the context. Reichenbach (1947, p. 288) claims that, in the context of a story, “the series of events recounted determines the point of reference” (R), and other events “lying outside this point are then referred, not directly to the point of speech, but to this point of reference determined by the story” (boldface added). In the simple past, E and R are typically simultaneous (E,R-S), which distinguishes the simple past from the perfect. Sentences in the present perfect, such as I have seen Charles, are “not of a narrative type but affect us with the immediacy of a direct report to the reader” (boldface added) (Reichenbach 1947, p. 289). Hence, while E is before S in the present perfect, R coincides with S: E-R,S. Clearly, if E precedes R (E-R), it holds that the viewpoint is external, but E does not have to precede R, since an external viewpoint is also possible for a future event (R-E). We witness the same patterns in Spanish, as explained below.

The present perfect in Spanish (called pretérito perfecto compuesto or antepresente) is used to express a past eventuality with continuing relevance at the present moment (E-R,S) (Comrie 1976; Azpiazu 2013). The implied relevance of the past event to the current situation in (1), Reichenbach’s “immediacy of a direct report to the speaker”, is determined by the context. In (1) it could be that the speaker is satisfied because the washing machine is empty and the laundry will dry quickly in the sun:1

| (1) | Pablo | ha | tendido | la | ropa | en | el | balcón. |

| Pablo | have.3SG.PRS | hang.PRF | the | laundry | on | the | balcony | |

| ‘Pablo has hung the laundry on the balcony.’ | ||||||||

Just like the English pluperfect, the Spanish pluperfect (pluscuamperfecto or antecopretérito) refers to an eventuality prior to a reference point that itself is in the past, hence E-R-S. Again, the context of the narration determines R. In (2), Pablo’s hanging out the laundry is located earlier in time than some reference point (narrative point of view) in the past, for example, a point when the narrator arrived at Pablo’s place.

| (2) | Pablo | había | tendido | la | ropa | en | el | balcón. |

| Pablo | have.3SG.IMPF | hang.PRF | the | laundry | on | the | balcony | |

| ‘Pablo had hung the laundry on the balcony.’ | ||||||||

The characterization of the English simple past as a narrative tense, in which E and R coincide, makes it an appropriate tense to tell a story (de Swart 2007). Spanish has two past tenses, however, the imperfect (pretérito imperfecto or copretérito) and the preterite or simple past (pretérito indefinido or pretérito simple). We assume, following Reichenbach (1947) for French, that both past tenses in Spanish are narrative tenses in which E and R coincide and precede S. Reichenbach (1947, p. 291) characterizes the French tenses imparfait and passé indefini (also called passé simple) as E,R-S, with the difference that the simple past refers to E as a point in time, whereas the imperfect refers to E as an interval, the latter indicating that “the event covers a certain stretch of time”. Rather than as a difference between E as a point or E as an interval, we interpret the difference between the two tenses as the aspectual difference between non-homogeneous and homogeneous eventualities, i.e., between events and states (Bary 2009). The imperfect is used to denote states, whereas the simple past is used to refer to events. Importantly, however, for both past tenses in Spanish, as well as in French, the narrative point of view R coincides with E (Reichenbach 1947). The two past tenses in Spanish are illustrated in (3) and (4).

| (3) | Pablo | tendió | la | ropa | en | el | balcón. |

| Pablo | hang.PST | the | laundry | on | the | balcony | |

| ‘Pablo hung the laundry on the balcony.’ | |||||||

| (4) | Pablo | tendía | la | ropa | en | el | balcón. |

| Pablo | hang.IMPF | the | laundry | on | the | balcony | |

| ‘Pablo was hanging the laundry on the balcony.’ | |||||||

As can be seen in the English translation of (4), the imperfect corresponds to the progressive in English. Indeed, Reichenbach (1947, p. 290) gives the English sentence I was seeing John the same temporal representation as the imperfect Je voyais Jean in French, i.e., E,R-S, with an ‘extended’ E. Because progressive aspect denotes states, it inherently shifts events to states (Bary 2009). As such, (4) might occur in the background part of a narration, implying that Pablo was hanging the laundry on the balcony when something else happened (Bybee 1995, p. 447). Reichenbach (1947, p. 290) notes that the “extended tenses [such as the progressive in English and the imperfect in French] are sometimes used to indicate, not duration of the event, but repetition”. Imperfective aspect, which corresponds to Reichenbach’s notion of ‘extended tense’, refers to homogeneous eventualities, i.e., states, and can be further broken down into habitual and continuous aspect (Comrie 1976).

The imperfect in Spanish thus marks past tense as well as imperfective aspect. The progressive in English can be seen as a specific construction that marks imperfective aspect in English, but unlike the imperfect, it is an analytical construction of which the auxiliary indicates tense and the present participle indicates imperfective aspect. Similarly, a present perfect construction in English, Spanish, and many other languages consists of an auxiliary denoting tense and a past participle denoting perfective aspect.

The imperfect in Romance languages expresses past tense and imperfective aspect, thus making explicit reference to a state in the past (Comrie 1976, p. 24; Bybee et al. 1994, p. 125). In our view, this does not imply that the simple past in Romance languages marks perfective aspect, pace Comrie (1976, p. 18) and Bybee et al. (1994, p. 54). We follow Cipria and Roberts (2000) and Borik and Janssen (2008), who argue that the non-homogeneous (telic) reading of the simple past in Romance languages is not part of its meaning, whereas the homogeneous (atelic) reading is part of the meaning of the imperfect. In accordance with this view, we take the imperfect in Spanish and French to mark imperfective aspect, just like a present participle in English, but we do not take the simple past to mark perfective aspect. Instead, the Spanish and French simple past tense obtains the event reading as a result of its co-existence with the imperfect, a past tense that marks imperfective aspect. By contrast, the past participle, which is part of the perfect, does mark perfective aspect in French and Spanish, just like in English.

Perfective aspect “denotes a situation viewed in its entirety” (Comrie 1976, p. 12). An example of perfective aspect marking as opposed to imperfective zero marking in Russian is given in (5)–(6), adopted from Wiemer and Seržant (2017, p. 245).

| (5) | Petja | čita-l | roman. |

| Petja.NOM | read-PST.3SG.M | novel.ACC | |

| ‘Peter read/was reading a novel.’ | |||

| (6) | Petja | pro-čita-l | roman. |

| Petja.NOM | PFV-read-PST.3SG.M | novel.ACC | |

| ‘Peter finished reading a novel.’ | |||

Although perfective aspect and past tense are marked independently of each other in (6), there is an intuitive relation between past tense and perfective aspect. If an eventuality (e.g., Peter reading a novel) is completed, it has come to an end, and is therefore usually situated in the past. Languages that lack a dedicated category of tense, but do have perfective aspect marking, e.g., Maltese Arabic and Lango, generally use the latter to refer to the past, and sometimes to the future, but never to the present (Malchukov 2009, p. 22). In fact, a combination of perfective aspect with present tense has been argued to be functionally impossible, as perfective aspect imposes an external view on the eventuality, whereas present tense locates the eventuality at the time of speech (Comrie 1976; Malchukov 2009).

If a synthetic form that combines perfective aspect and present tense is grammatically possible at all, it gives rise to the so-called ‘present perfective paradox’ (Malchukov 2009, 2011; De Wit 2016; Koss et al. 2022), triggering a shift in interpretation, resulting, for example, in a generic (narrative or habitual) meaning in Bulgarian and Serbo-Croatian, or a futurate meaning in Russian (Comrie 1976; Malchukov 2009). Malchukov, following Breu (1994), argues that, in Bulgarian, present tense has won the competition between tense and aspect, leading to a generic present tense reading. In this reading, E, R, and S coincide, which is a characteristic of the present tense, but not of perfective aspect. By contrast, perfective aspect has won the competition in Russian, leading to a futurate reading that involves an external viewpoint to a future eventuality. In this futurate reading, E and R do not coincide, which is in accordance with perfective aspect, but not with present tense. Compare the imperfective present tense (zero marked) in (7) with the ‘functionally impossible’ combination of present tense and perfective aspect in (8), a combination that leads to a futurate reading (Malchukov 2009).

| (7) | On | delaet. |

| he | do.PRES.3SG | |

| ‘He does.’ | ||

| (8) | On | s-delaet. |

| he | PFV-do.PRES.3SG | |

| ‘He will do.’ | ||

The aim of this article is to account for the differences between Spanish, French, English, and Dutch in their usage of the simple past and present perfect. As set out above, the simple past marks past tense and the perfect marks perfective aspect. This is the case in all four languages. In addition, the present perfect marks present tense, the pluperfect marks past tense, and the imperfect (only in French and Spanish) marks both past tense and imperfective aspect. Section 2 presents what we call ‘Schaden’s puzzle’, which is the observation that, in Spanish and English, the simple past seems to be the default tense to refer to eventualities in the past, whereas in French and German, the present perfect is. Section 3 will embed our solution to Schaden’s puzzle within an Optimality Theoretic (OT) framework, resulting in a number of hypotheses, to be tested in a literary corpus study reported in Section 4. The results of the corpus study are discussed in Section 5. Section 6 concludes.

2. The (Un)markedness of the Present Perfect: Schaden’s Puzzle

The present perfect seems to be neither a true tense nor a true aspect marker (cf. Reichenbach 1947; Comrie 1976; Lindstedt 2000; de Swart 2007; Schaden 2009; Ritz 2012; Fløgstad 2016). Some consider it a tense (Bybee 1995; Brinton 1988), some an aspect marker (Comrie 1976, p. 52), some avoid this classification altogether (Dixon 2012, pp. 31–32), and others, including us, consider it a combination of both (Ritz 2012). That the present perfect is a combination of tense and aspect is reflected by the fact that, in most languages, it is an analytic (periphrastic, complex) construction, consisting of an auxiliary and a past participle (Bybee and Dahl 1989; Hengeveld 2011; Ritz 2012), as opposed to the simple past. As pointed out above, the auxiliary provides the tense marker, which in the case of a present perfect is present tense, whereas the participle denotes perfective aspect.

The present perfect has been characterized as an unstable category across languages. It tends to evolve into either a ‘general past tense’, as in most Slavic languages and Southern German dialects, or a ‘perfective past’ as in spoken French (Bybee and Dahl 1989; Lindstedt 2000; Ritz 2012). The fact that French has two past tenses, whereas German has only one, accounts for this difference in development (Bybee and Dahl 1989). Indeed, the development by which the present perfect takes on the function of a ‘perfective past’ over time, called the aoristic drift, is found in the majority of the Romance languages (Harris 1982; Squartini and Bertinetto 2000; Schaden 2012; Drinka 2017; but see Azpiazu 2021 for an alternative approach to the perfect in Romance languages). As for Spanish, in large parts of America, the Canary Islands, and in the northwest of Spain, the present perfect has more or less retained its original meaning E-R,S, whereas, in other parts, viz., the rest of the Peninsula, the Andean area, and in the northwest of Argentina, the present perfect has increasingly evolved towards the ‘perfective past’ (E,R-S). Within these zones several different uses have been detected (Azpiazu 2013; Ariolfo 2019). Schwenter and Torres Cacoullos (2008) and Howe (2013) show clear differences in the distribution of the present perfect and the simple past. There are present perfect-favoring dialects (Peninsular Spanish dialects) and simple past-favoring ones (e.g., Mexican and Argentine Spanish) (Howe 2013, pp. 55–58; Howe and Rodríguez Louro 2013, p. 50). However, in northern parts of Argentina, a tendency opposite to the one found in Buenos Aires is observed, as here the present perfect is preferred over the simple past. Howe (2013, pp. 54–57) shows that the present perfect is used less in Argentinean Spanish than in Mexican and Peninsular Spanish.

Nevertheless, in the written register in Spanish, the current relevance meaning E-R,S of the present perfect is more or less standardized, as opposed to its evolution in spoken language (Azpiazu 2013, p. 28). A more radical process of divergence between registers has occurred in French. In contemporary French, the simple past is mainly used in written language registers, where it is still the standard tense for narrating a literary story. de Swart (2007, p. 2282) argues that when the narrator of a written story uses the present perfect instead of the literary simple past in French, as Camus did in his novel L’Étranger, this gives the story a very different ‘flavor’ and “calls up the atmosphere of letters or a diary”.

Reichenbach’s (1947) characterization of the present perfect as E-R,S, indicating an external point of view on a past eventuality (since E and R do not coincide), can account for several of its other features, namely its incompatibility with temporal adverbials that denote a specific reference time R for E, and also its unsuitability as a narrative tense (Lindstedt 2000; de Swart 2007). However, in French, German, and Dutch, the present perfect does allow for a temporal adverbial, and it can to a certain degree be used as a narrative tense (de Swart 2007). Van der Klis et al. (2021, p. 24) show examples in which Dutch and German translators opt for the present perfect (in accordance with the French source text) after a temporal connective such as ensuite ‘after that’, or puis ‘then’, while in Spanish and English a simple past is chosen:

| (9) | a. Tout s’est passé ensuite avec tant de précipitation, de certitude et de naturel, que je ne me souviens plus de rien. | [French] |

| b. Danach ist alles so überstürzt, vorschriftsmäßig und natürlich abgelaufen, daß ich mich an nichts mehr erinnere. | [German] | |

| c. Daarna is alles zo snel, met zoveel zekerheid en natuurlijkheid gegaan dat ik mij niets meer herinner. | [Dutch] | |

| d. Todo pasó después con tanta precipitación, exactitud y naturalidad; que no me acuerdo de nada. | [Spanish] | |

| e. After that everything happened so quickly and seemed so inevitable and natural that I don’t remember any of it anymore. | [English] |

| (10) | a. Et puis, je lui ai dit ses vérités. | [French] |

| b. Und dann habe ich ihr die Meinung gesagt. | [German] | |

| c. En daarna heb ik haar eens goed de waarheid gezegd. | [Dutch] | |

| d. Le dije cuatro verdades. | [Spanish] | |

| e. And then I told her a few home truths. | [English] |

In (9a–c) and (10a–c) the present perfect is used, whereas in (9d–e) and (10d–e) the simple past is used. This fits the observation that the present perfect can be used as a narrative tense in French and German (Bybee and Dahl 1989; Lindstedt 2000; Schaden 2012). Here, Dutch patterns with French and German, whereas Spanish and English do not.

That the present perfect can combine with a past-denoting temporal adverb in French, German, and Dutch, but not in Spanish or English, is illustrated by the following examples from Schaden (2009, p. 117) (we added the Dutch example (11c)). Note that we use the # sign to mark the infelicity of the sentences, instead of an asterisk indicating ungrammaticality:

| (11) | a. Jean est arrivé hier. | [French] |

| b. Hans ist gestern angekommen. | [German] | |

| c. Jan is gisteren aangekomen. | [Dutch] | |

| d. #Juan ha llegado ayer. | [Spanish] | |

| e. #John has arrived yesterday. | [English] |

de Swart (2007) argues in favor of a cross-linguistic Reichenbachian semantics E-R,S of the present perfect, augmented with further language-specific constraints in English and Dutch. According to her, the restrictions that the present perfect cannot combine with a temporal adverbial that refers to the eventuality in the past, and that it cannot be used as a narrative tense, do not stem from the Reichenbachian semantics E-R,S itself. However, it seems somewhat counter-intuitive that the more prototypical present perfect as in English needs additional semantic constraints, whereas the French and German present perfects, which are considered less prototypical because they have extended their use to a narrative past tense, would have the most prototypical core meaning without further modifications (thanks to Dennis Joosen p.c. for pointing this out to us). Yao (2014) argues that English is in the same historical process as French, German, Italian, and Spanish, and that grammaticalization of the present perfect in English goes hand in hand with gradual shifts in the nature of current relevance and co-occurring linguistic features. Similarly, Ritz (2012) reports that in Australian English the present perfect has started to acquire the past tense meaning E,R-S, for example in oral narratives. This extension of the present perfect’s use comes with a frequent co-occurrence with temporal adverbials to also refer to E. Ritz (2012, p. 21) concludes that “[w]hat is clear is that in a number of its uses, the Australian present perfect is no longer a true perfect”, thus arriving at a similar conclusion as Lindstedt (2000, p. 265), who states that “[w]hen a perfect can be used as a narrative tense (…) it has ceased to be a perfect”.

Schaden (2009) argues that in English, Spanish, French, and German, the present perfect competes with the simple past, and the outcome of the competition depends on which of these is the default past-referring tense in the language in question. In French and German, the present perfect is the default tense, whereas in English and Spanish the simple past is. The paradigm in (11) above shows the possibility of a default present perfect to obtain an E,R-S use in French, German, and Dutch, but not in English or Spanish. In (12), the opposite pattern is presented, namely the use of a default simple past in an E-R,S context, which is a possibility in English and Spanish, but not in German, Dutch, or French (Schaden 2009, p. 128) (again, we have added the Dutch example):

| (12) | [Archimedes in his bath …] | |

| a. I found it! | [English] | |

| b. ¡Lo encontré! | [Spanish] | |

| c. #Ich fand es! | [German] | |

| d. #Ik vond het! | [Dutch] | |

| e. #Je le trouvai! | [French] |

Based on examples such as (12a–b), Schaden (2009, p. 129) concludes that “even though the present perfect in English or Spanish has sometimes been characterized as being a better example of a perfect because of its dominant current-relevance character, it is not the only way to express current relevance in these languages. In French or German, however, in order to bring across something like ‘current-relevance’, one has no other choice than to use the present perfect”. Schaden’s (2009) observation appears to be an important and very robust observation. The default tense in English and Spanish is the simple past (although this is not necessarily the case for all varieties of Spanish and English), which can therefore not only be used in a prototypical narrative E,R-S context, but also in a current relevance E-R,S context, as illustrated in (12). By contrast, the default tense in French, German, and Dutch is the present perfect, which can therefore not only be used for the prototypical E-R,S reading, but also in a narrative E,R-S context, as exemplified in (11) (although this extended use is more restricted in Dutch than in German and French, cf. Boogaart 1999; Le Bruyn et al. 2019).

Schaden (2009) analyzes the pattern sketched above in terms of a competition between the simple past and the present perfect, but argues that the pattern cannot be derived from the ‘intrinsic’ markedness of the two, the reason being that the present perfect is always the marked form, because it is the morpho-syntactically more complex form (a periphrastic construction), whereas the current relevance meaning is the marked meaning. Schaden (2009, p. 133) argues that the present perfect is also semantically marked because it asymmetrically entails the simple past (if E-R,S, then E-S). The simple past is thus compatible with more possible worlds, and is hence semantically unmarked. The unmarked form would therefore be the simple past across languages, and the analysis would be unable to distinguish between English and Spanish on the one hand, and German and French on the other.

Schaden’s proposed analysis is thus based on the concept of a ‘default’ form, which, however, cannot be the morpho-syntactically unmarked form. This notion of a default tense form distinguishes between Spanish and English, where the default tense form is the simple past, and German and French, where it is the present perfect. Schaden (2009) cannot explain how the two tenses obtained their default status, as according to him it cannot be based on either syntactic or semantic markedness. Schaden (2009, p. 133) therefore concludes “that it is not possible to simply derive the markedness from some intrinsic properties of the present perfect and the simple past, as one could do in the framework of bidirectional Optimality Theory”. This is what we refer to as ‘Schaden’s puzzle’. In the next section we propose an analysis in which the present perfect does emerge as the unmarked form in French, German, and Dutch. This is achieved by dividing the present perfect into its two components, the markedness of which can be measured along two dimensions, tense and aspect. This then opens the way for an OT analysis that Schaden (2009) considers impossible, which can explain the differences between Spanish and English on the one hand, and French, German, and Dutch on the other.

3. An Optimality Theoretic Solution to Schaden’s Puzzle

The analysis we propose is couched in the general framework of Optimality Theory. Optimality Theory views grammar as a set of violable and potentially conflicting constraints that interact with each other (Smolensky and Legendre 2006). In OT Syntax an input meaning is mapped onto the optimal output form expressing that meaning best, whereas in OT Semantics an input form is unidirectionally mapped onto the optimal output interpretation of that form. However, what is optimal from a speaker’s perspective need not be optimal from a hearer’s perspective, and vice versa. Therefore, for the interplay between structure and interpretation we take a bidirectional OT perspective, resulting in optimal pairs of form and meaning (Hendriks et al. 2010). Abstracting away from the difference between languages in having either one (English, German, Dutch) or two (Spanish, French) past tenses, we propose two optimization patterns, one for English and Spanish, and the other for French, German, and Dutch.2

The constraints that we use in our OT analysis are defined below. Cross-linguistically, past tense is the marked form compared to present (or non-past) tense (Bybee and Dahl 1989). Perfective aspect can be the marked form compared to imperfective aspect, or it can be the other way around. For example, Müller (2013, p. 90) presents a number of South American languages in which perfective but not imperfective aspect is marked, a number of languages in which it is the other way around, and a number of languages in which both imperfective and perfective aspect are marked. From this we derive two markedness constraints on form, *PST (avoid past tense marking) and *PFV (avoid perfective aspect marking). These constraints may outrank their counterparts *PRS (avoid present tense marking) and *IPFV (avoid imperfective aspect marking) or not, but crucially, these two constraints can also be ranked with respect to each other. The third and fourth constraints are bidirectional faithfulness constraints between meaning and form. The third constraint links past tense marking to past eventualities, and the fourth constraint associates perfective aspect marking to external viewpoint.

- *PFV: Avoid perfective aspect marking on the verb;

- *PST: Avoid past tense marking on the verb;

- E-S ↔ PST: Mark past tense if and only if the eventuality precedes the time of speech;

- E-R ↔ PFV: Mark perfective aspect if and only if the viewpoint is external.

Bidirectional Optimality Theory is a framework that models simultaneous optimization of form and meaning, thus leading to optimal form-meaning pairs, instead of just optimal forms on the basis of input meanings, or just optimal interpretations on the basis of input forms (Hendriks et al. 2010). When a language has two available forms for two related interpretations, there are four form-meaning pairs that participate in the bidirectional OT competition, of which two pairs will win. These winning pairs are both called superoptimal. When a language has four related temporal meanings, E,R,S, E-R,S, E,R-S, and E-R-S, and four related tenses, i.e., present tense, simple past, present perfect, and pluperfect, we obtain four superoptimal pairs relating each tense to one meaning. This is shown in Tableau 1 (constraint violations are indicated with *). Tableau 1 presents a global analysis of the competition between these four meanings in a language with these four tenses (present tense, simple past, present perfect, and pluperfect) on the basis of the four constraints given above. Ranking the constraints would not alter the outcome of the bidirectional optimization. Therefore, we leave them unranked with respect to each other. To indicate this, the lines between the constraints are dotted instead of solid in the tableau. The superoptimal (winning) pairs in Tableau 1 are indicated by the sign  .

.

.

.

Tableau 1.

Bidirectional optimization of tenses.

Tableau 1.

Bidirectional optimization of tenses.

| *PFV | *PST | E-S ↔ PST | E-R ↔ PFV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRS, E,R,S | ||||

| PRS, E-R,S | * | * | |||

| PRS, E,R-S | * | ||||

| PRS, E-R-S | * | * | |||

| PST, E,R,S | * | * | |||

| PST, E-R,S | * | * | |||

| PST, E,R-S | * | |||

| PST, E-R-S | * | * | |||

| PRF, E,R,S | * | * | |||

| PRF, E-R,S | * | * | ||

| PRF, E,R-S | * | * | * | ||

| PRF, E-R-S | * | * | |||

| PLUP, E,R,S | * | * | * | * | |

| PLUP, E-R,S | * | * | |||

| PLUP, E,R-S | * | * | * | ||

| PLUP, E-R-S | * | * |

Tableau 1 shows that the first superoptimal pair is the pair that associates present tense to the E,R,S meaning, because this form-meaning pair does not violate any of the four constraints. This superoptimal pair blocks all other pairs with E,R,S as a meaning, and all other pairs with PRS as a form. The second round of bidirectional optimization results in the superoptimal pair that links the simple past to the meaning E,R-S, as this pair only violates the markedness constraint that penalizes past tense marking (*PST). The third and fourth superoptimal pairs combine the present perfect with the meaning E-R,S (violating one markedness and one faithfulness constraint), and the pluperfect with the meaning E-R-S, violating the two markedness constraints, but satisfying the two faithfulness constraints.

Note that, irrespective of the ranking between the two markedness constraints *PFV and *PST, bidirectional optimization results in three superoptimal pairs of form and meaning for reference to eventualities in the past, indicated by the sign  in Tableau 1. This accounts for the fact that, in the languages under consideration in this article, the core meanings of simple past and present perfect are E,R-S and E-R,S respectively, whereas the pluperfect is linked to E-R-S. Although this is a welcome result, bidirectional optimization cannot account for Schaden’s puzzle, namely, the difference between Spanish and English on the one hand, and French, German, and Dutch on the other. We argue that the difference between these languages is the result of a different ranking between the two markedness constraints *PFV and *PST. This provides an opportunity to model Schaden’s observations in an asymmetric model of bidirectional optimization, in which the outcome of production is constrained by interpretation (de Swart 2011).

in Tableau 1. This accounts for the fact that, in the languages under consideration in this article, the core meanings of simple past and present perfect are E,R-S and E-R,S respectively, whereas the pluperfect is linked to E-R-S. Although this is a welcome result, bidirectional optimization cannot account for Schaden’s puzzle, namely, the difference between Spanish and English on the one hand, and French, German, and Dutch on the other. We argue that the difference between these languages is the result of a different ranking between the two markedness constraints *PFV and *PST. This provides an opportunity to model Schaden’s observations in an asymmetric model of bidirectional optimization, in which the outcome of production is constrained by interpretation (de Swart 2011).

in Tableau 1. This accounts for the fact that, in the languages under consideration in this article, the core meanings of simple past and present perfect are E,R-S and E-R,S respectively, whereas the pluperfect is linked to E-R-S. Although this is a welcome result, bidirectional optimization cannot account for Schaden’s puzzle, namely, the difference between Spanish and English on the one hand, and French, German, and Dutch on the other. We argue that the difference between these languages is the result of a different ranking between the two markedness constraints *PFV and *PST. This provides an opportunity to model Schaden’s observations in an asymmetric model of bidirectional optimization, in which the outcome of production is constrained by interpretation (de Swart 2011).

in Tableau 1. This accounts for the fact that, in the languages under consideration in this article, the core meanings of simple past and present perfect are E,R-S and E-R,S respectively, whereas the pluperfect is linked to E-R-S. Although this is a welcome result, bidirectional optimization cannot account for Schaden’s puzzle, namely, the difference between Spanish and English on the one hand, and French, German, and Dutch on the other. We argue that the difference between these languages is the result of a different ranking between the two markedness constraints *PFV and *PST. This provides an opportunity to model Schaden’s observations in an asymmetric model of bidirectional optimization, in which the outcome of production is constrained by interpretation (de Swart 2011).In order to account for Schaden’s (2009) patterns of ‘default’ tenses, we propose that in English and Spanish, *PFV outranks *PST, whereas in French, German, and Dutch, *PST outranks *PFV. Because of these different rankings, the simple past will be the unmarked (optimal) form to refer to past eventualities in Spanish and English, whereas the present perfect will be the unmarked (optimal) form to refer to past eventualities in French, German, and Dutch.

If *PFV ranks above *PST, which we argue is the case in Spanish and English, the unmarked form may win the competition in an asymmetric OT derivation, as long as the unmarked form does yield the right (intended) interpretation. This pattern is reminiscent of other linguistic phenomena, such as differential object marking (de Swart 2011), where a marked form is used to obtain a marked interpretation, whereas the unmarked (default) form can have both an unmarked and a marked reading (de Hoop et al. 2004). If the context allows the hearer to arrive at the marked reading in the absence of the marked form, the speaker may suspend the use of the marked form for economy reasons (Hendriks et al. 2010; Lestrade and de Hoop 2016). Whether this is the case depends on the context. Recall example (12), in which the context (Archimedes in the bath) facilitates the E-R,S-meaning, because the relevance of the finding at speech time is more important than the fact that the finding happened in the past. That is to say, Archimedes is not telling a story about how he found something in the past (E,R-S). Rather, Archimedes is in a state of excitement because of what he has just discovered. Hence, the use of a present perfect does not seem necessary to arrive at the intended meaning E-R,S, at least not in English and Spanish. If Archimedes had uttered Ik vond het! ‘I found it’ in Dutch, however, this would force an E,R-S reading, as if he were telling a story. This is not the case in English and Spanish, but to allow the speaker to use the simple past in English and Spanish, it must be checked whether this unmarked form would result in the right interpretation. For this, we use a general meaning constraint, called FIT, that requires an interpretation to fit the context (Zwarts 2004):

- FIT: The interpretation should fit the (linguistic or extra-linguistic) context.

In (12) the given context is in favor of an E-R,S-interpretation, and an E,R-S meaning would violate FIT. This means that a speaker of Spanish or English can choose the unmarked (unidirectionally optimal) simple past here, even if it is not the bidirectionally optimal form (de Swart 2011). This is illustrated in Tableau 2.

Tableau 2.

Asymmetrical optimization in English and Spanish (example (12)).

Tableau 2.

Asymmetrical optimization in English and Spanish (example (12)).

| Prod: E-R,S | *PFV | *PST | E-S ↔ PST | E-R ↔ PFV | |

| PST | * | * | ||

| PRF | * | * | ||

| Int: PST | FIT | PST ↔ E-S | PFV ↔ E-R | ||

| E-R,S | ||||

| E,R-S | * | ||||

| Int: PRF | FIT | PST ↔ E-S | PFV ↔ E-R | ||

| E-R,S | ||||

| E,R-S | * | * |

The upper part of Tableau 2 shows the productive optimization (Prod) of the input meaning E-R,S, specified in the top-left cell, with two relevant output candidate forms, PST and PRF. PST is the winning candidate from a unidirectional perspective, as it satisfies *PFV. This unidirectionally optimal form is preceded by  . The bidirectionally optimal form PRF, which is linked to the E-R,S meaning (see Tableau 1), is preceded by

. The bidirectionally optimal form PRF, which is linked to the E-R,S meaning (see Tableau 1), is preceded by  . The two candidate forms enter the interpretive optimization (Int) in the lower parts of Tableau 2. The two markedness constraints *PST and *PFV no longer play a role in the optimization (because now the form is the input to interpretation, *PST and *PFV are vacuously satisfied or vacuously violated). We assume that FIT does play a role in interpretation, such that the meaning that was not intended by the speaker (the meaning that is not in the top-left cell) would violate FIT.

. The two candidate forms enter the interpretive optimization (Int) in the lower parts of Tableau 2. The two markedness constraints *PST and *PFV no longer play a role in the optimization (because now the form is the input to interpretation, *PST and *PFV are vacuously satisfied or vacuously violated). We assume that FIT does play a role in interpretation, such that the meaning that was not intended by the speaker (the meaning that is not in the top-left cell) would violate FIT.

. The bidirectionally optimal form PRF, which is linked to the E-R,S meaning (see Tableau 1), is preceded by

. The bidirectionally optimal form PRF, which is linked to the E-R,S meaning (see Tableau 1), is preceded by  . The two candidate forms enter the interpretive optimization (Int) in the lower parts of Tableau 2. The two markedness constraints *PST and *PFV no longer play a role in the optimization (because now the form is the input to interpretation, *PST and *PFV are vacuously satisfied or vacuously violated). We assume that FIT does play a role in interpretation, such that the meaning that was not intended by the speaker (the meaning that is not in the top-left cell) would violate FIT.

. The two candidate forms enter the interpretive optimization (Int) in the lower parts of Tableau 2. The two markedness constraints *PST and *PFV no longer play a role in the optimization (because now the form is the input to interpretation, *PST and *PFV are vacuously satisfied or vacuously violated). We assume that FIT does play a role in interpretation, such that the meaning that was not intended by the speaker (the meaning that is not in the top-left cell) would violate FIT.Thus, as can be read from Tableau 2, while E-R,S combines with the present perfect in bidirectional optimization across languages, it may be expressed by the unidirectionally optimal simple past in English and Spanish, indicated by the sign  . In these languages, simple past is the unmarked form, due to the ranking *PFV >> *PST, which is indicated by the solid line instead of the dotted line between the two constraints. To allow for the use of this suboptimal yet unmarked simple past, it is required that the hearer/reader will nonetheless arrive at the intended E-R,S interpretation. Note, however, that the present perfect is also available, because this is the bidirectional winner, even though it has the marked tense. Hence, Lo he encontrado in Spanish and I’ve found it in English can also be used to express the E-R,S reading in the context of (12).

. In these languages, simple past is the unmarked form, due to the ranking *PFV >> *PST, which is indicated by the solid line instead of the dotted line between the two constraints. To allow for the use of this suboptimal yet unmarked simple past, it is required that the hearer/reader will nonetheless arrive at the intended E-R,S interpretation. Note, however, that the present perfect is also available, because this is the bidirectional winner, even though it has the marked tense. Hence, Lo he encontrado in Spanish and I’ve found it in English can also be used to express the E-R,S reading in the context of (12).

. In these languages, simple past is the unmarked form, due to the ranking *PFV >> *PST, which is indicated by the solid line instead of the dotted line between the two constraints. To allow for the use of this suboptimal yet unmarked simple past, it is required that the hearer/reader will nonetheless arrive at the intended E-R,S interpretation. Note, however, that the present perfect is also available, because this is the bidirectional winner, even though it has the marked tense. Hence, Lo he encontrado in Spanish and I’ve found it in English can also be used to express the E-R,S reading in the context of (12).

. In these languages, simple past is the unmarked form, due to the ranking *PFV >> *PST, which is indicated by the solid line instead of the dotted line between the two constraints. To allow for the use of this suboptimal yet unmarked simple past, it is required that the hearer/reader will nonetheless arrive at the intended E-R,S interpretation. Note, however, that the present perfect is also available, because this is the bidirectional winner, even though it has the marked tense. Hence, Lo he encontrado in Spanish and I’ve found it in English can also be used to express the E-R,S reading in the context of (12).French, German, and Dutch have the reversed ranking *PST >> *PFV, which means that the simple past is not the unidirectionally optimal form for an E-R,S reading in these languages. Thus, in the context of (12) a simple past cannot be used to express the E-R,S interpretation (as shown by the infelicity of (12c–e). This is illustrated in Tableau 3 below.

Tableau 3.

Symmetrical optimization in French, German, and Dutch (example (12)).

Tableau 3.

Symmetrical optimization in French, German, and Dutch (example (12)).

| Prod: E-R,S | *PST | *PFV | E-S ↔ PST | E-R ↔ PFV | |

| PST | * | ||||

| PRF | * | * | ||

| Int: PRF | FIT | PST ↔ E-S | PFV ↔ E-R | ||

| E-R,S | ||||

| E,R-S | * | * |

Similarly, the unidirectionally optimal form to refer to past eventualities in French, German, and Dutch is the present perfect, and as such it may sometimes be used to express an E,R-S reading, even though this pair is not the winner of bidirectional optimization. This is illustrated by Schaden’s (2009) examples in (11) above. Again, the possibility to use the unmarked present perfect for another reading is only allowed if the unidirectionally optimal form yields the right interpretation. This again depends on the context. We assume that the temporal adverbial signals an E,R-S reading in (11) above. The analysis is illustrated in Tableau 4.

Tableau 4.

Asymmetrical optimization in French, German, and Dutch (example (11)).

Tableau 4.

Asymmetrical optimization in French, German, and Dutch (example (11)).

| Prod: E,R-S | *PST | *PFV | E-S ↔ PST | E-R ↔ PFV | |

| PST | * | |||

| PRF | * | * | * | |

| Int: PRF | FIT | PST ↔ E-S | PFV ↔ E-R | ||

| E-R,S | * | ||||

| E,R-S | * | |||

| Int: PST | FIT | PST ↔ E-S | PFV ↔ E-R | ||

| E-R,S | * | ||||

| E,R-S |

Although the simple past is the bidirectionally optimal form for the E,R-S interpretation, the present perfect can be used as a unidirectionally optimal form in (11), as long as the form yields the intended interpretation in the context (otherwise, FIT would be violated). In English and Spanish, the simple past is the unidirectionally and bidirectionally form in this context, as shown in Tableau 5.

Tableau 5.

Symmetrical optimization in English and Spanish (example (11)).

Tableau 5.

Symmetrical optimization in English and Spanish (example (11)).

| Prod: E,R-S | *PFV | *PST | E-S ↔ PST | E-R ↔ PFV | |

| PST | * | |||

| PRF | * | * | * | ||

| Int: PST | FIT | PST ↔ E-S | PFV ↔ E-R | ||

| E-R,S | * | ||||

| E,R-S |

Hendriks et al. (2010) discuss several possible architectures of bidirectional optimization, including asymmetrical models. Bidirectional optimization crucially hinges upon the existence of two available related forms for two closely related meanings (three forms for three meanings, four forms for four meanings, etc.). If only one meaning is available for two related forms, then the speaker can choose between the two forms, but if only one form exists for two meanings, then this form has to be ambiguous (de Hoop et al. 2004). Lestrade et al. (2016) show how unidirectional constraints can be derived from generalizations over multiple bidirectional optimization processes. Therefore, if or when the simple past is not available anymore, as might be the case in a non-narrative context in French, this may eventually lead or already have led to the emergence of a unidirectional constraint penalizing the use of the simple past in a non-narrative spoken context. The selection of the intended meaning for a present perfect in spoken French would then solely be determined by the meaning constraint FIT, and the present perfect would then have become truly ambiguous between an E,R-S and an E-R,S meaning in this context.

Based on the analyses discussed above, and further explained below, we put forward the following four hypotheses on the use of present perfect and simple past in the four languages under consideration in this study.

Hypothesis 1.

Simple past in Spanish is almost always translated to simple past in English;

Hypothesis 2.

Simple past in Spanish is sometimes translated to present perfect in Dutch dialogue;

Hypothesis 3.

Simple past in Spanish is almost always translated to present perfect in French dialogue;

Hypothesis 4.

Present perfect in Spanish is almost always translated to present perfect in English, French, and Dutch.

Because simple past is the unidirectionally optimal form in Spanish and English, it is not only used for a regular narrative E,R-S reading, but it can also be used in an E-R,S context, as long as the intended E-R,S meaning is recoverable from the context. Because this holds for both Spanish and English, we do not expect to find any differences in the translation from Spanish simple past to English (Hypothesis 1).

The Spanish simple past can be translated as a present perfect in French and Dutch under certain circumstances. For Dutch, we only expect this to happen in cases where the Spanish simple past obtains an E-R,S reading or where the Dutch present perfect obtains an E,R-S reading. However, both can only happen if FIT is satisfied, and even then the bidirectionally optimal form will always be a good alternative. In a literary novel, the E-R,S reading may be found in dialogue, as a proxy for spoken language, where R and S are more likely to coincide than in a narrative context (Hypothesis 2).

The circumstances under which a French present perfect is used to translate a Spanish simple past are different from those in Dutch. The simple past in French is nowadays largely restricted to written narrative contexts. Therefore, under the assumption that dialogues in a literary novel represent spoken non-narrative contexts, we predict Spanish simple past in dialogues to be always translated to present perfect in French (Hypothesis 3).

Because the present perfect is the suboptimal form from a unidirectional perspective in Spanish, we only expect it to be used in an E-R,S context, where it is the bidirectionally optimal winning form. In these cases, it will also be the bidirectionally optimal form in English, French, and Dutch. Therefore, we expect that the present perfect in Spanish is almost always translated as present perfect in the other three languages (Hypothesis 4).

The four hypotheses are tested in a literary corpus study of a Spanish novel and its translations into English, Dutch, and French in the next section. Consider one example (13) from our corpus, in which the unmarked simple past is used three times in the Spanish original (13a) (in bold).

| (13) | a. | ¿Por qué no se separó? ¿Por qué no la abandonó de inmediato?—le pregunté sin embargo. | [Spanish] |

| b. | Pourquoi ne vous êtes-vous pas séparés ? Pourquoi ne l’avez-vous pas aussitôt abandonnée ? lui demandai-je. | [French] | |

| c. | ‘Waarom ging u niet scheiden? Waarom verliet u haar niet onmiddellijk?’ vroeg ik niettemin. | [Dutch] | |

| d. | However, I asked: ‘Why didn’t you separate? Weren’t you tempted to just leave at once?’ | [English] |

The Spanish simple past forms se separó ‘you separated’ and abandonó ‘you abandoned’ appear in a direct speech situation, hence in dialogue. The Spanish simple past form pregunté ‘I asked’, by contrast, appears outside of the dialogue. Hypothesis 1 predicts that all three occurrences of simple past will also be translated to simple past in English. This is indeed the case, as can be seen in (13d). Hypothesis 3 predicts that the two simple pasts in the dialogue will be translated by present perfect forms in French. Indeed, the French translation in (13b) uses the present perfect forms s’être séparé ‘have (lit. are) separated’ and avoir abandonné ‘have left’. The narrative simple past pregunté ‘I asked’ is outside the dialogue, and translated in French with a simple past form demandai ‘asked’. Dutch could also have used the present perfect in the dialogue, but that would have given a current relevance interpretation to the eventualities of parting and leaving in the past (Boogaart 1999), while those events did not even take place (as evidenced by the negation). The current relevance of these non-existent eventualities to the speaker of the utterance (the first-person narrator of the story) would be rather far-fetched. Therefore, the use of the narrative simple past in (13c) is the best option and satisfies FIT. The next section will test our four hypotheses in a more systematic way by means of a translation corpus study.

4. A Translation Corpus Study of Javier Marías’s Así empieza lo malo

4.1. Materials and Methods

We decided to test our hypotheses by means of a literary corpus study. Our corpus consists of a selection of eight chapters from Javier Marías’s Así empieza lo malo (2014) and its translations into French by Fortier-Masek (2016), English by Jull Costa (2016), and Dutch by Glastra van Loon (2015). The reason we chose a Dutch translation instead of a German one, even though Schaden’s puzzle originally concerned German rather than Dutch, was for practical reasons: the authors of the current paper are all native speakers of Dutch. The book contains eleven parts, which are subdivided into shorter chapters of approximately three to eight pages. Four of the chapters in our analysis are from the beginning of the book (part I and II), in which the main characters are introduced. These fragments are mostly written in a narrative ‘setting-the-scene’ style. The four remaining chapters in our corpus were selected from the back portion of the book (part IX and X), where there is more direct speech. The eight selected chapters from the Spanish source text and its translations into Dutch, English, and French were collated into a database. We aligned each Spanish sentence to its translations in order to be able to directly compare the verb forms across the four languages.3 We then listed each predicate from the original Spanish text in a separate column and added its translations to Dutch, English, and French. We annotated all predicates in each language for tense.

We included the following tense labels in our design: imperfect (IMPF), simple past (PST), present perfect (PRF), pluperfect (PLUP), and other (X). The latter category contained predicates that were translated with a tense form that was not included in our design, with an adjectival or adverbial phrase, or not translated at all. In total, 1579 predicates were annotated in the four languages, summing to a total of 6316 verb-form labels. We then annotated each predicate for the register in which they appear in the novel, i.e., narration vs. dialogue.

4.2. Results

Of the 1579 predicates, 1050 occurred in narration (66.5%) and 529 in dialogue (33.5%). The data for predicates in narration are presented in Table 1, where the columns represent the forms used in the Spanish original and the rows represent the forms used in the Dutch, English, and French translations (including category X). The cells with numbers printed in italics represent one-to-one translations (for the Dutch and English translations of Spanish imperfects and simple pasts, we printed the simple pasts in italics as well). The percentages between brackets indicate the number of predicates of the Spanish form (row) translated into a given form of the target language (column).

Table 1.

Number of Spanish forms (rows) translated to Dutch, English, and French forms (columns) in narration, with the relative proportion in % between brackets.

As noted, a difference between Spanish and French on the one hand, and Dutch and English on the other, is that Dutch and English do not have two past tenses, but only one. The data in Table 1 show that the vast majority of Spanish imperfects were translated to simple pasts in Dutch (91.6%) and English (76.3%), whereas most of these predicates were translated to imperfects in French (78.0%). Notice that a substantial number of Spanish imperfects were not translated with one of the four tense forms under investigation in English and French (English: 19.0%, French: 18.9%). This is also true for Spanish simple pasts, albeit to a lesser extent (English: 8.7%, French: 8.3%). Overall, the data demonstrate that most Spanish predicates in narration were translated with their direct counterparts in the three languages.

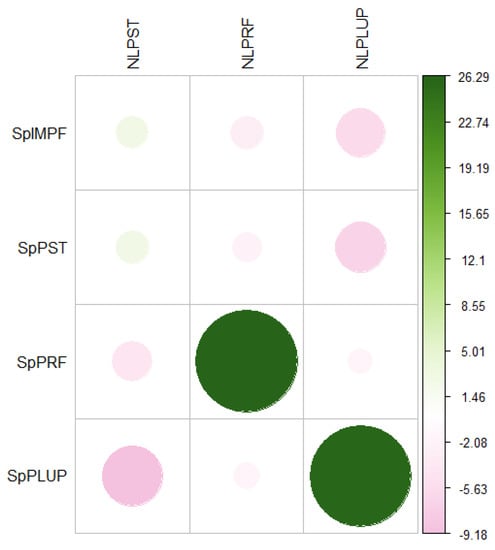

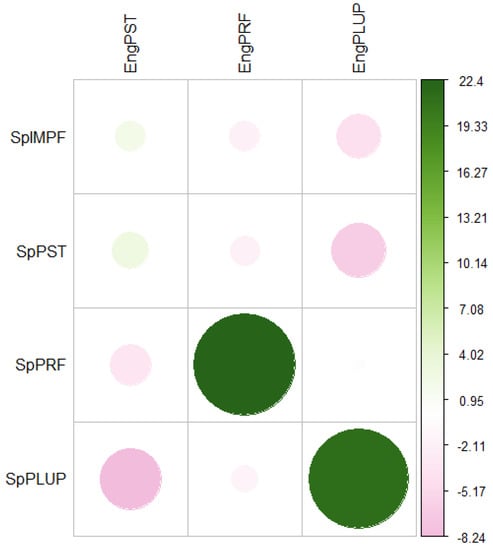

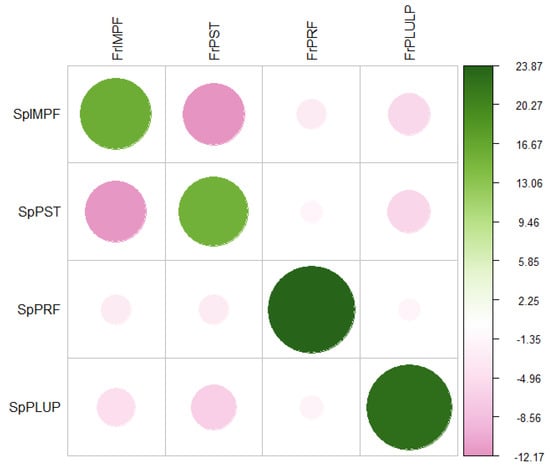

We removed the category X translations from the data and performed separate chi-squared tests of independence for each language in the software R (version 4.0.5, R Core Team 2020), to test whether there was a significant association between Spanish forms and their translations (in narration). We expected highly significant effects, given the high numbers of one-to-one translations. Indeed, each of the tests yielded a significant effect (Dutch: χ2(6) = 1577.3, p < .001; English: χ2(6) = 1127.2, p < .001; French: χ2(9) = 2029.4, p < .001). We calculated and visualized the Pearson residuals for each cell, using the package corrplot (Wei and Simko 2021), to determine which one contributed to the chi-square statistic the most. These are visually presented in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 below. The size of each circle and the intensity of its color are proportional to the corresponding contribution to the test statistic, with green circles representing positive associations and pink circles negative associations.

Figure 1.

Visualization of Pearson residuals of Spanish tenses translated to Dutch tenses in narration.

Figure 2.

Visualization of Pearson residuals of Spanish tenses translated to English tenses in narration.

Figure 3.

Visualization of Pearson residuals of Spanish tenses translated to French tenses in narration.

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show a positive association between, on the one hand, Spanish imperfects and simple pasts, and on the other, the simple past in both Dutch and English, which is the only available past tense in these two languages. French, by contrast, does have an imperfect, which shows a strong positive association with the Spanish imperfect. There is also a strong positive association between the French and the Spanish simple past, as shown in Figure 3. Moreover, there are strong negative associations between the Spanish imperfect and the French simple past, and vice versa. The graphs in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 further show strong positive associations between other one-to-one translations (i.e., the present perfect and pluperfect forms) and negative associations for Spanish forms translated to different forms, in all three languages.

Let us now turn to the 527 predicates that occurred in dialogue. The data are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Number of Spanish forms (rows) translated to Dutch, English, and French forms (columns) in dialogue, with the relative proportion in % between brackets.

Table 2 shows that most Spanish imperfects were again translated to the simple past in Dutch (91.0%) and in English (81.3%), and to the imperfect in French (75.0%). We again find a relatively high number of predicates not translated to a critical tense form in the English and French translations of Spanish imperfects (English: 12.5%, French: 18.0%) and simple pasts (English: 11.6%, French: 14.0%). The data crucially suggest that there is more variance in translations of tensed verbs in dialogue than in narration. There are three exceptions to the tendency to translate a form with the same tense, one for each language. In Dutch, the proportion of Spanish simple past forms translated to present perfects is relatively high, verifying Hypothesis 3 (N = 25, 10.7%). In English, the proportion of Spanish present perfects translated to simple pasts is relatively high, partly falsifying Hypothesis 4 (N = 23, 39.1%). In French, more Spanish simple pasts were translated to present perfects (N = 121, 52.0%) than to simple pasts (N = 61, 26.0%), which is in the direction of Hypothesis 2, but nevertheless falsifies it.

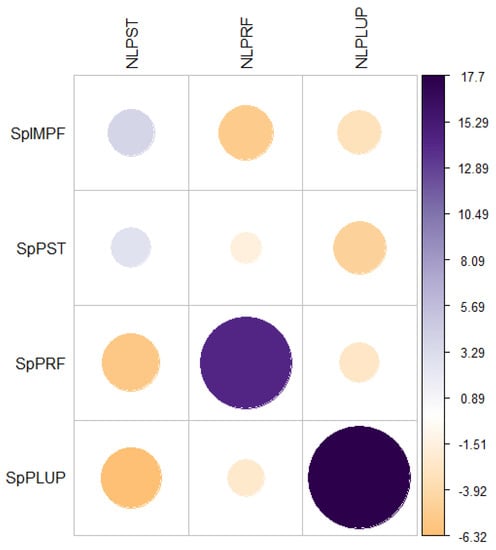

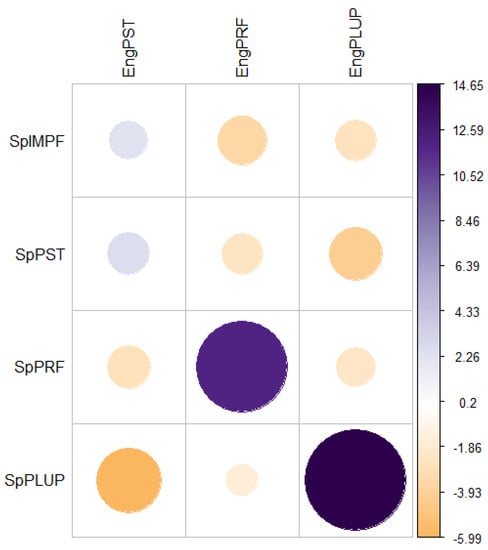

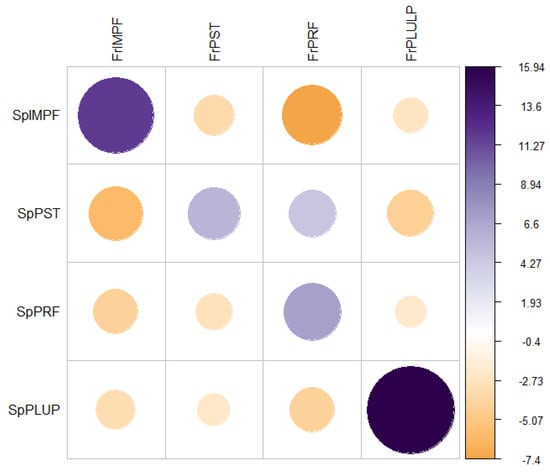

We removed the category X translations from the data and performed three more chi-squared tests for the predicates in dialogue, and once again found three significant effects (Dutch: χ2(6) = 684.9, p < .001; English: χ2(6) = 461.1, p < .001; French: χ2(9) = 694.4, p < .001). We calculated the Pearson residuals and visualized them in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 below, using a different color scheme to mark the contrast with the translations in narration. The size of each circle and the intensity of its color are again proportional to the corresponding contribution to the test statistic, but here purple circles represent positive associations and orange circles represent negative associations.

Figure 4.

Visualization of Pearson residuals of Spanish tenses translated to Dutch tenses in dialogue.

Figure 5.

Visualization of Pearson residuals of Spanish tenses translated to English tenses in dialogue.

Figure 6.

Visualization of Pearson residuals of Spanish tenses translated to French tenses in dialogue.

The same picture as before emerges: the one-to-one translations carry most of the weight. However, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 also reflect our three observations from above.

First, although there is a negative association between the Spanish simple past and the Dutch present perfect in Figure 4, this is much weaker than between the Spanish present perfect and the Dutch simple past. This crucially indicates that the translation of the Spanish simple past to the Dutch present perfect is not just arbitrary, even though the percentages of the two translation pairs in Table 2 are apparently similar. Further, note that the negative association between the Spanish imperfect and the Dutch present perfect is much stronger. That is, Spanish imperfects reject a Dutch present perfect translation much harder than Spanish simple pasts do.

Second, we mentioned that the number of Spanish present perfects translated to English simple pasts is relatively high. Figure 5 shows a negative association between these categories, but this is presumably because the overall number of present perfects is relatively low (that is, most English simple pasts are not translations of Spanish present perfects). Nonetheless, the Spanish pluperfect rejects English simple past translations harder, as indicated by the bigger and more orange circle (note that there is an equal number of English tensed verb translations of Spanish present perfects and Spanish pluperfects in dialogue, N = 54).

Third, Figure 6 shows a strong positive association between Spanish simple pasts and French present perfects. This finding clearly reflects a deviation from the one-to-one translation pattern, given that French also has the simple past form, which is underused in dialogue. However, since we predicted present perfect in French dialogue to be almost non-existent (Hypothesis 3), the number of French simple past translations in dialogue is remarkably high.

5. Discussion

Let us reconsider the hypotheses put forward in Section 3, in order to check whether they were falsified or verified by the results of our literary corpus study:

Hypothesis 1.Simple past in Spanish is almost always translated to simple past in English;Hypothesis 2.Simple past in Spanish is sometimes translated to present perfect in Dutch dialogue;Hypothesis 3.Simple past in Spanish is almost always translated to present perfect in French dialogue;Hypothesis 4.Present perfect in Spanish is almost always translated to present perfect in English, French, and Dutch.

Hypothesis 1 was verified by the results of the corpus study, as Spanish past tenses were translated to English past tense in the vast majority of cases, both in narration and dialogue.

Hypothesis 2 was also verified, since 10.7% of the simple past forms in Spanish were translated to present perfect in Dutch dialogue. This was expected, because the simple past is the unidirectionally optimal tense to refer to past eventualities in Spanish, whereas the present perfect is unidirectionally optimal in Dutch. Thus, a translation from Spanish simple past to Dutch present perfect can occur when either the Spanish simple past obtains an E-R,S reading, or when the Dutch present perfect obtains an E,R-S reading. Both options are constrained by FIT, and we did not expect them to happen frequently in a literary novel.

Strikingly, Hypothesis 3 was falsified. Although simple past was often (in more than half of the cases) translated to present perfect in French dialogue, as we predicted, this was clearly not (almost) always the case. In a quarter of the cases Spanish simple past was in fact translated to French simple past in dialogue. The question is how this is possible, since simple past is assumed to be very rare in non-narrative spoken French, hence in dialogue. However, many dialogues in our corpus still have a literary, narrative character. Almost half of the 61 cases occurred in one of three larger clusters reflecting (literary) narration within a dialogue. One example of a French simple past, used for narrating a piece of history (hence, narration) within a dialogue, is given in (14):

| (14) | a. | … y está algo vinculado un general responsable de una de las “caravanas de la muerte”, en la que se cargaron a sangre fría a setenta y tantos detenidos en octubre del 73, poco después del golpe | [Spanish] |

| b. | … on prétend qu’un général, responsable de l’une de ces « Caravanes de la mort » où ils tuèrent de sang-froid plus de soixante-dix détenus en octobre 73, juste après le coup d’État, aurait des liens avec le mouvement | [French] | |

| c. | … and it has some connections with one of the generals responsible for the “Caravan of Death”, which saw the cold-blooded murder of seventy or more prisoners in October 1973, shortly after the coup | [English] |

As Azpiazu (2021, p. 234) points out, the choice between the simple past and the present perfect is “linked to the type of information the speaker decides to prioritize: the content [simple past] or the interaction with the interlocutor [present perfect]”. In dialogue, even when an interlocutor is present, the narrative point of view R can coincide with E, especially when an explicit reference point is given in the past, as is the case in (14) above, ‘October 1973, shortly after the coup’ (cf. Corre 2022, on Breton, where this also seems to be the case). We assume that in a clearly narrative context, even within dialogue, the bidirectional optimization still yields the simple past as the superoptimal form for an E,R-S reading. Other factors may also be responsible for the unexpected use of the simple past in French dialogues. We found some simple pasts to be part of fossilized expressions in French, such as tel ne fut pas le cas ‘it wasn’t the case’.

Finally, Hypothesis 4 was verified for French and Dutch, but, surprisingly, only in part for English, since present perfect forms in Spanish dialogues were not almost always translated to present perfect forms in English. In dialogues, more than one-third of the present perfects in the Spanish source text (23 cases) were translated as simple pasts in English.4 We argued in Section 3 that, although the E-R,S reading is optimally expressed by the present perfect, it can also be expressed by a simple past in Spanish and English, as long as the intended reading is obtained in a straightforward way (satisfaction of FIT). Apparently, this bidirectionally suboptimal yet unidirectionally optimal option is more often chosen in the English translation than in the Spanish source text, and the question is why is this the case.

One important difference between the Spanish and English present perfect is that the former is considered hodiernal (Dahl 1985, p. 125; Schwenter 1994; Xiqués 2021). When a temporal adverbial expression, such as hoy ‘today’, explicitly links to the present, the present perfect is considered the default form in European Spanish (cf. Schwenter and Torres Cacoullos 2008), which does not hold for English. Van der Klis et al. (2021) also find that the present perfect is more restricted in English than in Spanish. Their dataset contains the occurrences of the present perfect from the first three chapters of the French novel L’Étranger, and its translations to Spanish and English, among other languages. Of 348 present perfect forms in the French source text, only 16 are translated to the present perfect in Spanish, and only 11 to the present perfect in English. Van der Klis et al. (2021) argue that the hodiernal use of Spanish cannot explain all differences between Spanish and English translations in their data set, however. They even point out one example in which Spanish aligns with English, and uses a simple past in combination with the adverb hoy ‘today’. The example comes from the 1971 translation of L’Étranger by the Spanish poet José Ángel Valente, where Aujourd’hui j’ai beaucoup travaillé au bureau is translated as Hoy trabajé duro en la oficina ‘I worked hard at the office today’, i.e., with the simple past in Spanish. In the 2021 translation by María Teresa Gallego Urrutia and Amaya García Gallego, the sentence is translated as Hoy he trabajado mucho en la oficina, so using the present perfect, as we would expect.

Nevertheless, we agree with Van der Klis et al. (2021, p. 28) that the hodiernal nature of the Spanish perfect “cannot be the entire story”. They argue that the Spanish present perfect is not incompatible with pragmatically presupposed events, whereas the English present perfect is (Michaelis 1994); however, they also show that this cannot be the entire story. Their conclusion is that the difference between the Spanish and English perfect resides in pragmatics, but a full account of the pragmatic differences between the two languages is beyond the scope of their paper. This is also the case of our paper, but we would like to make a small contribution to the discussion. As hinted at in Section 3, the choice of a bidirectionally or unidirectionally optimal form to express a particular meaning also affects that meaning itself. In most of the 23 cases in our corpus, the English translator opted for the simple past because a present perfect would render effects that are absent in the corresponding present perfect in the source text. It is worth discussing two representative examples in detail to clarify this.

The speaker of (15) is the male protagonist. He is in a violent mood, and when his wife appears at the door of his room, in a nightdress, he addresses her with scorn and anger.

| (15) | a. | A ver, ¿qué quieres que te mire? ¿Ese camisón? Qué pasa, ¿te lo has comprado o te lo han regalado? No seas ridícula, te tengo muy vista, (…). Ya te estoy mirando, ¿y qué? Sebo, siempre sebo, para mí no eres más que eso. | [Spanish] |

| b. | What is it you want me to look at? That nightdress? Did you buy it or did someone give it to you? Don’t be ridiculous, I’ve seen more than enough of you, (…). All right, I’m looking at you, so what? Lard, pure lard, that’s all you are to me. | [English] |

Obviously, the eventualities in the past that are referred to are relevant at the time of speech, because the nightdress seems the topic of the discourse in (15). Thus, the speaker of (15) takes an external viewpoint of the hypothetical eventualities of buying and giving this nightdress in the past. Nonetheless, the English translator chose the simple past here. As we argued in Section 3, it is possible to use a simple past with an E-R,S reading, as long as the current relevance reading is clear. This is indeed the case in both English and Spanish, but the present perfect in English places even more emphasis on the current relevance of the eventuality than the present perfect in Spanish. The present perfect in English often yields a presupposition of discourse relevance (Michaelis 1994; Portner 2003; Van der Klis et al. 2021). Therefore, if the present perfect had been used in the translation of the question (in boldface), Have you bought it or has someone given it to you?, the speaker would expect an answer to this question, which is clearly not the case. The Spanish source text, with the question in the present perfect, does not yield this presupposition, as is clear from the rest of the utterance. The questions are somewhat rhetorical, the nightdress does not really matter, and with the imperative no seas ridícula ‘don’t be ridiculous’, the speaker accuses his wife of trying to get his attention by showing her nightgown. He makes it very clear that he is not interested in the nightdress, nor in her, and he berates her with the word sebo ‘lard’.

The next example in (16) illustrates an effect that can be obtained with the Spanish present perfect. In this example a minor character in the novel speaks to the young man, who is the narrator, about the male protagonist of the previous example. He tells about the sexual morality of 1940s and 1950s, when Spain was under Franco’s dictatorship, and the practices of the male protagonist at that time. He calls him un depredador insaciable ‘an insatiable predator’. The fragment, given here in abridged form, contains several past tenses (imperfects and simple pasts), but also two present perfects (in boldface).

| (16) | a. | (…) ¿Tú qué te piensas, que la revolución sexual ya imperaba y existía la píldora? Por favor, el mundo no empezó a la vez que tú. Ha estado muy difícil echar un polvo en España. Había que malgastar mucho tiempo y hacer muchas promesas, y aun así. (…) A todas les ha tirado los tejos, a las que valían la pena; con peor o mejor gusto, con más o menos presiones y con más o menos éxito; y aún continúa haciéndolo, a sus sesenta años cumplidos.’ | [Spanish] |

| b. | Do you honestly imagine that the sexual revolution was up and running and that the pill already existed? It was really difficult to get laid in Spain. You had to waste a lot of time and make a lot of promises, and even then. (…) He tried it on with all of them, those worth having, that is; tastefully and not so tastefully, forcefully and not so forcefully, and with more or less success; and he’s still doing it in his sixties. | [English] |

In this fragment about past events that happened long ago (thirty or forty years before the story takes place), the two occurrences of the present perfect are marked. The speaker relates these two eventualities in the past to the present, i.e., the speech time of the conversation (E-R,S). The first present perfect marks the fact that the speaker himself also experienced how difficult it was to have sex at that time, although the story is not about him. The second present perfect marks the fact that the practices of the male protagonist are still occurring, which is made explicit in the last sentence ‘and he’s still doing it in his sixties’. This second present perfect could also have been translated with a present perfect in English, as it obtains a continuative (‘extended now’) reading, something like ‘He has tried it on with all of them to this day’. This is indeed an instantiation of the E-R,S reading, for which the Spanish present perfect is the bidirectionally optimal form and the English simple past in the translation is the unidirectionally optimal form. However, the first present perfect is more difficult to explain, as this could not have been translated with a present perfect in English. In Spanish, the present perfect can mark the external perspective of the speaker, who had similar difficulties in the past. This effect is consistent with the temporal conception that traditional scholars of Spanish, from Bello (1847) onwards, have taken as the central component to the Spanish present perfect (cf. Azpiazu 2018, 2021). Azpiazu (2018, p. 131) formulates it as follows: “In European Spanish, it [the present perfect] can also refer to a boundless lapse of time that encompasses any past event (…). The PTS [perfect time span] or IP [increased present] is (…) a temporal interval relevant to the speaker to the extent that it can be linked to the here and now of the speech act”. The temporal interval that is relevant here includes the present and the past eventuality; hence, the speaker can narrate the past eventuality from an external perspective at speech time. In English, E and R coincide, because there is no temporal overlap between the present and the past eventuality. Thus, the first present perfect in the fragment in (16) comes with an E-R,S reading in Spanish, which is not possible in English. In English, the E,R-S reading prevails, and hence only the (bidirectionally and unidirectionally) optimal simple past is possible here.

Based on the examples of English simple past translations of the Spanish present perfect, we seem to observe a different intensity of the components of the present perfect in the two languages. Although in English the perfective aspect seems predominant, allowing the past eventuality to be foregrounded by the speaker, in Spanish the present tense is predominant, giving the speaker the opportunity to connect a past eventuality with the situation at speech time. Thus, although the nuanced differences between the two languages in their use of the present perfect are not predicted by our OT analysis, it is suggested that a more gradual difference in markedness between the temporal and aspectual components of the present perfect can help explain these differences.

6. Conclusions

Under the assumption that the present perfect in Spanish, French, English, and Dutch marks both perfective aspect and present tense, we argue that this combination of marking tense and aspect makes the present perfect the optimal (unmarked) form to refer to past eventualities in French and Dutch, whereas in Spanish and English the optimal (unmarked) form is the simple past. The unidirectionally optimal form allows a tense to express not only its prototypical meaning (E-R,S for a present perfect and E,R-S for a simple past), but also the ‘other’ meaning, as long as certain conditions that guarantee the intended meaning are met. The results of a literary translation study from Spanish grammatical tenses to English, French, and Dutch indicate that Spanish tenses are mostly translated to their direct counterparts in all three languages. In dialogue, however, we found some deviations from these one-to-one translations, which partially confirmed our hypotheses. In particular, Spanish simple past was translated to the present perfect in French and Dutch in a significant number of cases. One unexpected finding was that, in a substantial number of cases, the Spanish present perfect was translated with an English simple past. This indicates nuanced differences in the present perfect between the two languages that go beyond referring to a past eventuality with a bidirectionally or unidirectionally optimal form, since, according to our analysis, these would be the same in the two languages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M., G.S., O.H., H.d.H.; Methodology, G.M., G.S., H.d.H.; Formal analysis, G.S.; Investigation, G.M., G.S., O.H., H.d.H.; Writing—original draft preparation, G.M., G.S., H.d.H.; Writing—review and editing, G.M., G.S., O.H., H.d.H.; Visualization, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to our colleagues Janine Berns, Corentin Bourdeau, Sebastiaan Faber, Ferdy Hubers, Andrej Malchukov, Dominique Nouveau, Marc Smeets, and Peter de Swart, for helpful discussions. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers and guest editors for their comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Abbreviations used in the glosses: acc = accusative case; ipfv = imperfective (aspect); impf = imperfect (past tense); nom = nominative case; pfv = perfective (aspect); prs = present; prf = perfect; pst = past tense; plup = pluperfect; SG = singular. |

| 2 | As argued in Section 1, the ‘perfective’ simple past in Romance languages does not violate the constraint that prohibits perfective aspect marking, because it does not explicitly mark perfective aspect (Cipria and Roberts 2000; Borik and Janssen 2008). The E for eventuality in the derivation could be further broken down into an e (for event) and an s (for state) in order to capture the competition between the simple past and the imperfect, but since this has no effect on the competition between the simple past and the present perfect, we will ignore this difference in the rest of this paper. |

| 3 | Some ‘sentences’ consisted of multiple lines in a given language, as the translations did not always follow the original sentence structure. |