Decomposing Perfect Readings

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Different kinds of ‘perfect’-like properties

- Experiential/existentialMary has visited the Louvre.(There is at least one instance of Mary visiting the Louvre prior to the speech time. This is also felicitous without a contextually salient past time.)

- ResultativeMary has arrived.1(The result state holds.)

- Recent past/hot newsThe Orioles have won the game!(A past event presented as new information, often recent.)

- Universal Perfect/ContinuativeMary has been studying since this morning.(Mary is still studying.)

- Present Perfect Puzzle*Mary has arrived yesterday.(Prohibited with a definite past temporal adverbial.)

- Lifetime effect#Einstein has visited Princeton.(Prohibited with dead subjects.)

- No narrative progression#Josef has turned around. The man has pulled out his gun.(Cannot be used in the narration of a series of past events which have taken place back to back.)(Iatridou et al. 2003; Katz 2003; Klein 1992; McCawley 1971; McCoard 1978; Portner 2003, 2011, a.o.)

- (2)

- The ‘general-purpose’ past perfective

- Has the experiential/existential reading but does not show the lifetime effect.

- Result state may hold at the utterance time but not required.

- Recent past possible.

- Definite past adverbials allowed.

- Narrative progression allowed.

- (3)

- Four cross-linguistic categories of perfect/past perfective forms

Times Events Pronominal past perfective forms — Existential quantified experiential forms resultative forms Hybrid forms

- (4)

- Different kinds of tense/aspect constructions

Presuppositions Domain Times Events Anaphoricity En past tense, Written Fr/Gr/It simple past MC verbal -le Uniqueness En past tense — None En present perfect, Fr/Gr/It present perfect MC sentence-final -le Anti-resultativeness — MC -guo En: English; Fr: French (standard variety, spoken version); Gr: German (standard variety); It: Italian (standard variety); MC: Mandarin Chinese

- (5)

- Presupposed Ignorance Principle (PIP)Let be a sentence, be an alternative of . If:

- whenever is defined, is also defined;

- in context c;

then is infelicitous in context c.

- (6)

- (It is common sense that this phone has only one weight.){ The, #A} weight of this phone is 300 g.

- Maria hat einen Ornithologen ins Seminar eingeladen. Ich halte {#vonMary has an ornithologist to-the seminar invited I hold {ofeinem/von dem} Mann nicht sehr viel.one/of thestrong} man not very much‘Maria has invited an ornithologist to the seminar. I don’t think very highly of the man.’

- (7)

- Last night, a pathologically curious neighbor of mine broke into the attic.

- (8)

- Anti-presupposition(We don’t know how many children John has.)All of John’s children play soccer.presuppositionally stronger alternative: Both of John’s children play soccer.

2. Anaphoricity vs. Non-Anaphoricity

2.1. Tenses

2.1.1. Present Perfect Puzzle

- (9)

- #Mary has arrived yesterday.

- (10)

- (The context does not contain any salient past time:)I went to Disneyland over the weekend. It was so much fun!

- (11)

- (Talking about Mary’s trip to Disneyland last Saturday:)A: Apparently, she had to wait for four hours to get onto any ride because it was so crowded.B: Yeah I can imagine that because it’s always crowded over the weekends. I went there last Wednesday and I barely had to wait.

- (12)

- Mary has visited the Louvre. She saw the Mona Lisa there.

- (13)

- Every farmer who has a donkey beats it.

- Every girl who has visited the Louvre saw the Mona Lisa there.

2.1.2. Narrative Progression

- (14)

- Mary turned the handle. The door opened. The room was dark. She turned on the light.

- (15)

- (A speaker talks about the conference from yesterday:)

- I was nervous, and then I wasn’t anymore.

- The first talk was boring. The second one was very nice.

- (16)

- Mary turned off the light. The room was pitch dark.

- (17)

- Mary has been sick.

- Existential: There is a state of Mary being sick, which is over, before the speech time.

- Universal Perfect: There is a state of Mary being sick which spans from the past and overlaps with the speech time (she’s still sick).

2.1.3. In the Absence of Competition

- (18)

- Different kinds of tense/aspect constructions

Presuppositions Domain Times Events Anaphoric En past tense, Written Fr/Gr/It simple past MC verbal -le Uniqueness En past tense — None En present perfect, Fr/Gr/It present perfect MC sentence-final -le Anti-resultative — MC -guo En: English; Fr: French (standard variety); Gr: German (standard variety, spoken version); It: Italian (standard variety, spoken version); MC: Mandarin Chinese

- (19)

- No Present Perfect Puzzle

- Gianni è arrivato ieri.Gianni aux arrived yesterday‘(Lit.) Gianni has arrived yesterday.’ (Italian)

- Jean est arrivé hier.Jean aux arrived yesterday‘(Lit.) Jean has arrived yesterday.’ (French)

- Maria ist gestern angekommen.Maria aux yesterday arrived‘(Lit.) Maria has arrived yesterday.’

- (20)

- Narrative progression

- Gianni si è girato. L’uomo ha tirato fuori la pistola.Gianni ref aux turned-around the-man aux took out the pistol‘(Lit.) Gianni has turned around. The man has pulled out his pistol.’

- Jean s’est retourné. L’homme a sorti son arme.Jean ref-aux turned-around the-man aux took-out his gun‘(Lit.) Jean has turned around. The man has pulled out his gun.’

- John hat sich umgedreht, und der Mann hat seine Pistole gezogen.John aux ref around-turned and the man aux his pistol pulled‘(Lit.) John has turned around. The man has pulled out his gun.’

2.1.4. Comparison with Previous Analyses

- (21)

- I enjoyed/#have enjoyed yesterday’s party.

- (22)

- Mary arrived/#has arrived on yesterday’s flight.

- (23)

- (Talking about what happened yesterday:)# Mary has enjoyed the party.

- (24)

- #Mary has arrived on yesterday’s flight.

- (25)

- (In the absence of previous discourse:)

- I have seen last year’s best rated film.

- Mary has seen yesterday’s visitor.

- (26)

- Present, past and perfect in English (Pancheva and Von Stechow 2004)

- a.

- 〚present〛

- b.

- 〚past〛

- c.

- 〚perfrct〛where iff there is no s.t.

- d.

- Combined present perfect operator〚present perfect〛(where iff there is no s.t. )

- (27)

- Present, past and perfect in German (Pancheva and Von Stechow 2004)a. 〚present1〛where iffb. 〚past2〛c. 〚perfect〛where iff there is no s.t. .d. Combined present perfect operator〚present perfect〛

- (28)

- 〚present perfectstrengthened〛.

- (29)

- Mary read all the books.

- Mary read some of the books.Inference: Mary didn’t read all the books.

- (30)

- It’s not the case that Mary read any book.

- It’s not the case that Mary read all the books.Inference: Mary actually read some of the books.

- (31)

- It’s not the case that Mary has been to the Louvre.

- It’s not the case that Mary went to the Louvre.Inference:

- (32)

- (Talking about last year:)

- It’s not the case that Mary has been to the Louvre.

- It’s not the case that Mary went to the Louvre.

2.2. Aspects

- (33)

- (Context: We know Lisi exercises every day, including yesterday. What kind of exercises did he do?)

- Lisi zuotian you le yong.Lisi yesterday swim le.vb swim.n‘Lisi had a swim yesterday.’

- #Lisi zuotian you yong le.Lisi yesterday swim swim.n le.sf‘(Intended:) Lisi had a swim yesterday.’

- #Lisi zuotian you guo yong.Lisi yesterday swim guo swim‘(Intended:) Lisi had a swim yesterday.’

- (34)

- (Context: We are talking about the Tokyo Marathon this year. Who won the men and the women’s races?)

- Nanzi zu Kipchoge pao le diyi ming. Nüzi zu Kosgei paomen group Kipchoge run le.vb first place women group Kosgei runle diyi ming.le.vb first place‘In the men’s race, Kipchoge got first place. In the women’s race, Kosgei got first place.’

- #Nanzi zu Kipchoge pao diyi ming le. Nüzi zu Kosgei pao lemen group Kipchoge run first place le.sf women group Kosgei run firstdiyi ming.place le.sf‘(Intended:) In the men’s race, Kipchoge got first place. In the women’s race, Kosgei got first place.’

- #Nanzi zu Kipchoge pao guo diyi ming. Nüzi zu Kosgei pao lemen group Kipchoge run guo first place women group Kosgei run guodiyi ming.first place‘(Intended:) In the men’s race, Kipchoge got first place. In the women’s race, Kosgei got first place.’

- (35)

- (Context: There is no contextually salient event when the following are uttered.)

- #Lisi zuotian you le yong.Lisi yesterday swim le swim.n‘Lisi had a swim.’

- Lisi zuotian you yong le.Lisi yesterday swim swim.n le.sf‘Lisi has had a swim.’8

- Lisi zuotian you guo yong.Lisi yesterday swim guo swim‘Lisi has had a swim.’

- (36)

- Lisi zuotian you le yong.Lisi yesterday swim le swim.n‘Lisi had a swim yesterday.’

- Lisi zuotian you yong le.Lisi yesterday swim swim.n le.sf‘Lisi had a swim yesterday.’

- Lisi zuotian you guo yong.Lisi yesterday swim guo swim‘Lisi had a swim yesterday.’

- (37)

- Presuppositions of Mandarin Chinese perfective particles

Event antecedent presupposition Anti-resultative presupposition verballe ✓ — guo — ✓ perfective sentence-finalle — —

- (38)

- Presupposed Ignorance Principle (PIP)Let be a sentence, be an alternative of . If:

- whenever is defined, is also defined;

- in context c;

then is infelicitous in context c.

- (39)

- Presuppositions of Mandarin Chinese perfective particles (Alternative analysis)

Event antecedent presupposition Anti-resultative presupposition verballe ✓ — guo ✗ ✓ perfective sentence-finalle — —

3. Hot News, Existential and Resultative Readings

- (40)

- (Mary meets her friend after a long time:)A: How are you doing?B: I’ve been diagnosed with cancer.Inference: B is currently sick with cancer.

- (At a house party, we are waiting for friends to arrive. Bill hears the doorbell and opens the door for someone. Susan, however, is too focused on a video game and is unaware. She then notices voices at the door.)Susan: What’s happening?Katie: Mary has arrived. Let’s go meet her!Inference: Mary is here now.

- (The postman comes to deliver a package, without knowing whether Mary is still here:)A: Here is a parcel for Mary.B: Mary has gone home.Inference: Mary is no longer here.

- (Mary, who is not at home now, texts her roommate about the kitchen:)Mary: I’d like to use the kitchen but you guys made such a mess last night.Roommate: Don’t worry, I have cleaned the kitchen already.Inference: The kitchen is clean now.

- (I want to borrow Mary’s key to the office.)Mary: I’ve lost my key.Inference: The key is gone.

- (41)

- (Talking about Mary’s experiences.)She’s lost her key to the office (before).…in fact, it’s still not found.…but she found it later.

- (42)

- Lisi ba diannao nong-huai le.Lisi caus computer make-broken le.sf‘Lisi broke the computer yesterday.’Inference: The computer is still broken.

- Lisi nong-huai guo diannao.Lisi make-broken guo computer‘Lisi has broken this computer (before).’Inference: The computer is probably fixed.

- (43)

- (Talking about what happened yesterday:)Lisi ba diannao nong-huai le. Ranhou you xiu-hao le.Lisi caus computer make-broken le.sf then again fix-well le.sf‘Lisi broke the computer yesterday. And then it got fixed again.’

- (44)

- (What can you tell me about Lisi as a person?)Lisi nong-huai guo Zhangsan de diannao. Xianzai hai mei xiu-hao.Lisi make-broken guo Zhangsan gen computer now still neg fix-well‘Lisi has once broken Zhangsan’s computer. It’s still not fixed today.’

- (45)

- The presupposition of-guoA sentence with -guo is infelicitous if:, where

- e

- ans is true of a proposition if it is a complete or partial answer to the discourse topic at the time the sentence is uttered;

- is true iff , where is the modal base based on causality, accessed from world w and utterance situation u.

- (46)

- (Can I borrow the key to the office?)

- #Wo diu guo yaoshi.I lose guo key‘(Intended:) I’ve lost the key.’

- Wo ba yaoshi diu le.I caus key lost le.sf‘I’ve lost the key.’Inference: I can’t lend you the key because they are gone.

- (47)

- The presuppositions of the present perfect (Portner 2003)A sentence S of the form presupposes:, where

- p is the proposition expressed by ϕ, and

- the property ans is true of any proposition which is a complete or partial answer to the discourse topic at the time S is uttered, and

- the operator is similar to an epistemic must:is true iff , where is the epistemic conversational background accessed from world w and utterance situation u.

4. Uniqueness vs. Non-Uniqueness

4.1. Contextually Salient Results

- (48)

- (Pointing at a church:)

- #Who has built this church?#Borromini has built this church.

- Who built this church?Borromini built this church.

- (49)

- (Looking at some litter:)

- #Who has littered here?

- Who littered here?

- (50)

- (Looking at some litter:)

- Shui reng laji le?who throw litter le.sf‘Who littered here (the litter we are looking at)?’

- #Shui reng guo laji?who throw guo litter‘Who littered here (the litter we are looking at)?’

- (51)

- (Mary meets her friend after a long time. They are talking about how they are doing now.)

- Wo bei quezhen aizheng le.I pass diagnose cancer le.sf‘I’ve been diagnosed with cancer.’Inference: The speaker is currently sick with cancer.

- #Wo bei quezhen guo aizheng.I pass diagnose guo cancer‘(Intended:) I’ve been diagnosed with cancer (i.e., I’m currently sick with cancer).’

- (52)

- (Looking for Mary in the office.)

- Mali zou le.Mary leave le.sf‘Mary has left.’Inference: Mary is not here anymore.

- #Mali zou guo.Mary leave guo‘(Intended:) Mary has left (so she’s not here anymore).’

- (53)

- (I’m hoping to borrow the key to the office from Mary.)

- Wo ba vyaoshi nong-diu le.I caus key make-lost le.sf‘I’ve lost the key.’Inference: The key is gone now.

- #Wo nong-diu guo yaoshi.I make-lost guo key‘(Intended:) I’ve lost the key (so it’s gone now).’

4.2. Uniqueness Presupposition of the English Past

- (54)

- (Pointing at a church:)

- #Borromini costruì questa chiesa.Borromini built this church‘(Intended:) Borromini built this church.’ (Italian)

- #Borromini construisit cette église.Borromini built this church‘(Intended:) Borromini built this church.’ (French)

- #Borromini baute diese Kirche.Borromini built this church‘(Intended:) Borromini built this church.’ (German)

- (55)

- (Pointing at a church:)

- Borromini ha costruito questa chiesa.Borromini aux built.pp this church‘(Lit.) Borromini has built this church.’ (Italian)

- Borromini a construit cette église.Borromini aux built.pp this church‘(Lit.) Borromini has built this church.’ (French)

- Borromini hat diese Kirche gebaut.Borromini aux this church built.pp‘(Lit.) Borromini has built this church.’ (German)

4.3. Comparison with Previous Analyses

- (56)

- (Out of the blue:)#Mary danced.10

5. Lifetime Effects

- (57)

- (Talking about Miguel’s late great-grandmother. There is no contextually salient past time.)Her name was/#has been Coco, and she had/#has had such a personality.

- (58)

- (Talking about Einstein, whom we know is dead. There is no other contextually salient past time.)

- Einstein visited Princeton.

- #Einstein has visited Princeton.

- (59)

- (Talking about an exhibit which we know is over. There is no other contextually salient past time.)

- Did you visit the exhibit?

- #Have you visited the exhibit?

- (60)

- (Talking about Princeton. There is no contextually salient past time.)

- Princeton has been visited by Einstein.

- #Princeton was visited by Einstein.

- (61)

- (Talking about what I did last Sunday.)

- Did you visit the Monet exhibit?

- #Have you visited the Monet exhibit?

- (62)

- (We do not know if the Monet exhibit is still on:)

- Have you visited the Monet exhibit?Inference: The exhibit is still on.

- Did you visit the Monet exhibit?Inference: The exhibit is over.

- (63)

- The president has been assassinated.12

- (64)

- (Talking about Einstein today:)

- Einstein ha visitato Princeton.Einstein has visited Princeton‘(Lit.) Einstein has visited Princeton.’

- Einstein s’est exprimé sur ses convictions socialistes.Einstein 3rd.ref-aux expressed on his opinions socialist‘(Lit.) Einstein has expressed his socialist beliefs.’

- Einstein hat Princeton besucht.Einstein has Princeton visited‘(Lit.) Einstein has visited Princeton.’

6. More on ‘Hot News’

No Additional Presuppositions for the Present Perfect

- (65)

- The Orioles have won!Implicit topic question: How are the Orioles doing lately?

- (66)

- (There is no previous discourse or contextually salient past time.)Do you know? I’ve been to the Louvre.#I went to the Louvre.

- (67)

- A: What did Mary do last year?B: She moved to Kazakhstan.#She has moved to Kazakhstan.

7. Interim Summary

- (68)

- Tenses

- the present perfect can function as a presuppositionally neutral past tense;

- the past tense is a presuppositionally stronger alternative of the present perfect for the past reading;

- the English past tense has a non-anaphoric use, which follows from a uniqueness presupposition, and this presupposition is absent for languages such as French, German, and Italian;

- one can maintain the same analysis of the present perfect in English, French, German, and Italian and derive the variation of the present perfect from the availability of the presuppositionally stronger alternatives.

- (69)

- Aspects

- the Mandarin perfective verbal -le differs from the perfective sentence-final -le and -guo, in that it presupposes an event antecedent;

- Mandarin Chinese has a null nonfuture tense, as in Matthewson (2006); Sun (2014), and the perfective particles cannot be analyzed as reflecting the anaphoricity of the nonfuture tense;

- -guo differs from the perfective sentence-final -le, in that it presupposes that the result state of the event does not answer the topic question;

- the perfective sentence-final le is the presuppositionally neutral particle in Mandarin Chinese.

- (70)

- The source of perfect readings

- Non-anaphoricity (Present Perfect Puzzle, lack of narrative progression): follows from the competition with an anaphoric alternative;

- Hot news, existential: introducing new reference time into the Common Ground and asserting the existence of a culminated past event;

- Resultative: follows from Gricean principle of relevance and the existential reading above, answering a topic question about a current state with the assertion of a change-of-state event;

- Prohibition of the present perfect when the result state is contextually salient (Borromini church example): follows from the competition with the presuppositionally stronger unique past (English);

- Lifetime effect: follows from the competition with the presuppositionally stronger unique past (English)—past lifetime of an individual is unique.

8. Formal Analysis

8.1. Tenses

8.1.1. Unique Past Tense

- (71)

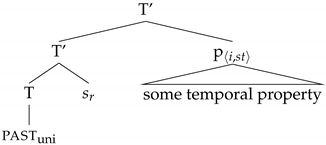

- Unique past tensea.b. 〚pastuni〛gwhere MI(t) wrt to p means t is maximally informative with respect to p as in (72).c. 〚(71-a)〛g

- (72)

- Maximal informativenessFor a temporal property , a time interval t is maximally informative w.r.t. q in s iff

- a.

- , and

- b.

- For all t′, .

- (73)

- λt.λs.∃e[e is the unique change-of-state event giving rise to a contextually salient state s ∧ τ(e) ⊆ t]

- λt.λs.∃s[Einstein-alive(s) ∧ t ⊆ τ(s)]

- (74)

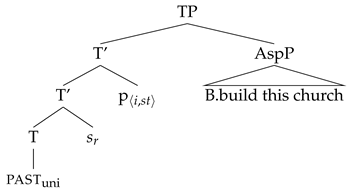

- (Pointing at a church:)

- Borromini built this church.

- (75)

- in s, where p is as explained above.

8.1.2. Anaphoric Past Tense

- (76)

- Anaphoric past tense

- a.

- b.

- c.

- 〚(76-a)〛g =

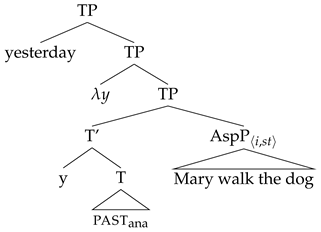

- (77)

- The temporal property for the anaphoric past.

- (78)

- Temporal adverbialswhere means the interval corresponding to ‘yesterday’ in the context.

- (79)

- (80)

- (81)

8.1.3. The Present Perfect

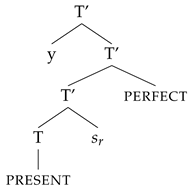

- (82)

- The present perfect

- a.

- ,where maps a situation to the temporal interval corresponding to that situation.

- b.

- c.

- (83)

- (84)

- ContextThe context c is a set of assignment function-world pairs such that:

- ∀f, f′ s.t. ∃w[〈f,w〉∈c], dom(f) = dom(f′), written as dom(c).

- (85)

- Presupposition satisfaction (variable-free)Let c be a context. Let p be a sentence with presupposition .Updating the context c with p, written as , is defined iff for some f, is true in w.

- (86)

- Context UpdateIf p does not contain any variable, and is defined,.

- (87)

- ‘It’s raining’.

- (88)

- Context update example of the present perfectLet c be a context, p be a sentence of the form [pp [perfective [Mary dance]] ].

- if :is defined iff for each , , where is the speech time.if defined,

- else:,where means is just like f except that .

- (89)

- Context update example of the anaphoric pastLet c be a context, p be a sentence of the form [pastana [perfective [Mary dance]] ].is defined iff:

- , and

- for each , , where is the speech time.

If defined,

- (90)

- Mary has been to the Louvre and it was/#has been very crowded.

- Every girl who has been to the Louvre saw/#has seen the Mona Lisa there.

- (91)

- p: Mary has been1 to the Louvre.

- q: She saw1 the Mona Lisa there.

- (92)

- Context update example of the unique pastLet c be a context, p be an atomic proposition of the form [pastuni [perfective [Borromini build this church]] ].is defined iff:

- , and

- for each , there is a unique interval such that MI(t) with respect to is the unique building event of this church,

If defined,is the unique interval t s.t. MI(t) wrt“λt.λs.∃e[e is the unique building event of this church” ∧ t ≺ tc ∧ ∃e[build(e) ∧Agent(e) = Borromini ∧ Theme(e) = this church ∧ τ(e) ⊆ f′(i)] in w,for some},where f′[i]f means f′ is just like f except that dom(f′) = dom(f) ∪ {i}

8.2. Aspects

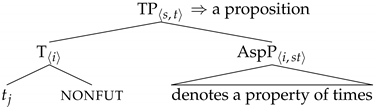

- (93)

- The NONFUTURE tense

- (94)

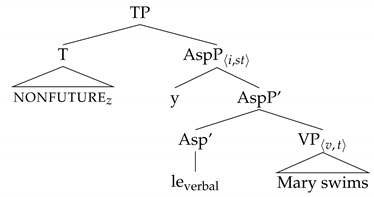

- verbal-le

- ,where is taken to be the identity or the part-whole relation (cf. Section 2.2).

- (95)

- The perfective sentence-final -le

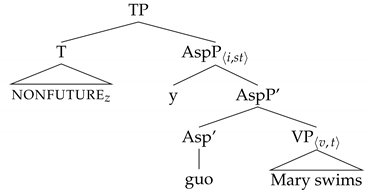

- (96)

- -guo

- (i)

- ans is true of a proposition if it is a complete or partial answer to the discourse topic at the time the sentence is uttered;

- (ii)

- is true iff , , where is the modal base based on causality, accessed from world w and utterance situation u.

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The resultative perfect reading is characterized by the fact that the result state cannot be cancelled: #I’ve lost my keys, but then I found them again. See (Bertrand et al. 2017, 2022); Matthewson et al. (2017). However, this only applies to the resultative reading and is not a general constraint of the present perfect. |

| 2 | The past-tense morphology may not denote a past time if embedded under a future operator, such as were in the following sentence: John decided a week ago that in ten days he would say to his mother that they were having their last meal together. These instances of embedded past are beyond the scope of this dissertation. |

| 3 | In German, this constraint excludes some statives, modals, and auxiliaries. |

| 4 | It has been observed that, in Dutch, there is no Present Perfect Puzzle, but the present perfect is not used for narrative progression (Bertrand et al. 2017). At this point, I do not have access to Dutch data regarding the availability of the simple past, so I cannot judge whether this is an exception to the pattern I observed. In any case, while the Present Perfect Puzzle seems to illustrate a simple, straightforward anaphoric reading, narrative progression involves additional mechanisms. The Dutch data may provide insights for a more complete analysis of the narrative progression that will account for Bertrand et al.’s (2017) observation, which is beyond the scope of this paper. |

| 5 | |

| 6 | In this paper, I distinguish the perfective sentence-final -le from the presuppositional particle labeled as the ‘sentential -le’ in the literature (Soh 2009; Soh and Gao 2006), which is is a sentence-level particle with a change-of-state presupposition. This distinction has not been made in the previous literature, which leads to confused judgements and conflicting data. Due to limited space, it will be impossible to give a detailed discussion to justify my claim. Briefly, the sentential -le and what I call the perfective sentence-final -le can be distinguished by: (i) the perfective sentence-final -le does not presuppose any change-of-state, and (ii) the perfective sentence-final -le does not allow the current stative, progressive, or habitual reading such as the presuppositional sentential -le, and (iii) it has been noted that the presuppositional sentential -le cannot occur with downward-entailing numeral-classifier phrase subjects (Soh 2009), while the perfective sentence-final -le is not subject to this constraint. |

| 7 | I believe many of the conflicting and vague judgements are due to misclassification, especially with the various particles homophonous to le. It is beyond the scope of this paper to fully justify my classifications and analyses of these particles. The reader can refer to Zhao (n.d.) for a detailed discussion. |

| 8 | Here, it is important that we are dealing with the perfective sentence-final -le instead of the sentential -le, the latter of which is not a perfective particle, but rather a sentence-level operator that with a change-of-state presupposition. If the -le here is interpreted as the sentential -le, it will scope higher than Lisi youyong, which has only the habitual reading without aspectual marking (Sun 2014). The sentence will then presuppose that Lisi used to not swim and assert that Lisi now swims habitually. |

| 9 | For the litter example, the speaker also needs to assume that the litter is not accumulated gradually but discarded all at once. The judgement is subtle, but it seems that, under the ‘slowly accumulated’ pile of litter assumption, the present perfect in (49) significantly improves and may even be preferred. |

| 10 | A reviewer points out that Mary called. seems to be felicitous out of the blue and suggests a relevance-based analysis. However, I believe her example does not necessitate relevance. In particular, almost all the contexts I can think of for the so-called ‘out-of-the-blue’ use of Mary called are ones in which the addressee returns from a short period of absence. In these cases, one may simply assume that the reference time is the contextually salient ‘just now’ or ‘the time of the addressee’s absence’. In other words, these are not truly ‘out of the blue’, but rather, similar to Partee’s (1973) I didn’t turn off the stove example, where the reference time is the contextually salient ‘20 min before the speaker leaves the house’ and can easily be incorporated into a strictly pronominal analysis of the past tense. |

| 11 | |

| 12 | A reviewer argues that this sentence satisfies repeatability, since the future president could be assassinated. However, what I have in mind for this example has a de re interpretation of the president. In any case, the same judgement holds for examples with actual names, like Bill Gates has been assassinated!. |

| 13 | Due to limited space, I will only introduce the most necessary definitions I need in this paper. |

| 14 | Arguably, we may need an additional principle regulating index use: the speaker should avoid using a new index if it is to be assigned to a value already assigned to some old index. |

| 15 | Since, in English, the anaphoric and the unique past tenses have the same morphology, I assume that the anaphoric reading always involve an anaphoric past tense. This assumption will not make any difference in terms of the predictions. |

| 16 | Note that, since event anaphora in Mandarin Chinese are always via a relation (either identity or part-whole), we do not need to define the index of verbal -le as familiar. It suffices to define all three perfective particles as adding a new index for simplicity. |

References

- Abusch, Dorit. 1994. Sequence of tense revisited: Two semantic accounts of tense in intensional contexts. Ellipsis, Tense and Questions, 87–139. Available online: projects.illc.uva.nl (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Arkoh, Ruby, and Lisa Matthewson. 2013. A familiar definite article in akan. Lingua 123: 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, Anne, Bruno Andreotti, Heather Burge, Sihwei Chen, Joash Gambarage, Erin A. Guntly, Thomas J. Heins, Marianne Huijsmans, Kalim Kassam, Lisa Matthewson, and et al. 2017. Nobody’s perfect. Paper presented at the Workshop on the Semantics of Verbal Morphology in Underdescribed Languages, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, June 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand, Anne, Yurika Aonuki, Sihwei Chen, Joash Gambarage, Laura Griffin, Marianne Huijsmans, Lisa Matthewson, Daniel Reisinger, Hotze Rullmann, Raiane Salles, and et al. 2022. Nobody’s perfect. Languages 7: 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Sihwei, Jozina Vander Klok, Lisa Matthewson, and Hotze Rullmann. 2021. The ‘experiential’ as an existential past. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 39: 709–58. [Google Scholar]

- Chierchia, Gennaro. 1995. Dynamics of Meaning: Anaphora, Presupposition and the Theory of Grammar. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Swart, Henriëtte. 1998. Aspect shift and coercion. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 16: 347–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Swart, Henriëtte. 2016. Perfect use across lanugages. Questions and Answers in Linguistics 3: 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Depraetere, Ilse. 1998. On the resultative character of present perfect sentences. Journal of Pragmatics 29: 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbourne, Paul. 2013. Definite Descriptions. Oxford Studies in Semantics and Pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Groenendijk, Jeroen, and Martin Stokhof. 1991. Dynamic predicate logic. Linguistics and Philosophy 14: 39–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønn, Atle, and Arnim Von Stechow. 2016. Tense. In Handbook of Formal Semantics. Edited by Maria Aloni and Paul Dekker. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 313–41. [Google Scholar]

- Grønn, Atle, and Arnim Von Stechow. 2017. The perfect. In Wiley’s Linguistics Companion (Companion to Semantics). Edited by Daniel Gutzmann, Lisa Matthewson, Cécile Meier, Hotze Rullmann and Thomas Ede Zimmermann. Hoboken: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Heim, Irene. 1982. The Semantics of Definite and Indefinite Noun Phrases. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachussetts, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Heim, Irene. 1983a. File change semantics and the familiarity theory of definiteness. Semantics Critical Concepts in Linguistics, 108–35. Available online: scholar.archive.org (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Heim, Irene. 1983b. On the projection problem for presuppositions. In Formal Semantics—The Essential Readings. Hoboken: Blackwell, pp. 249–60. [Google Scholar]

- Heim, Irene. 1990. E-type pronouns and donkey anaphora. Linguistics and Philosophy 13: 137–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, Irene. 1991. Artikel und definitheit. In Semantik: Ein internationales Handbuch der Zeitgenössischen Forschung. Edited by Arnim Von Stechow and Dieter Wunderlich. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 487–535. [Google Scholar]

- Heim, Irene. 1994. Comments on abusch’s theory of tense. Ellipsis, Tense and Questions, 143–70. Available online: https://www.semanticsarchive.net/Archive/Tg5ZmI1N/heim-comments-Abusch-94.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Heim, Irene. 2011. Definiteness and indefiniteness. In Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning. Edited by Klaus Von Heusinger, Claudia Maienborn and Paul Portner. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 996–1025. [Google Scholar]

- Heim, Irene, and Angelika Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in Generative Grammar. Oxford: Blackwell Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Iatridou, Sabine, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Roumyana Pancheva. 2003. Observations about the form and meaning of the perfect. In Perfect Explorations. Edited by Artemis Alexiadou, Monika Rathert and Arnim Von Stechow. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Iljic, Robert. 1990. The verbal suffix-guo in mandarin chinese and the notion of recurrence. Lingua 81: 301–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Kyoko. 1979. An analysis of the English present perfect. Linguistics 17: 561–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenks, Peter. 2015. Two kinds of definites in numeral classifier languages. Semantics and Linguistic Theory 25: 103–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, Hans. 1981. A theory of truth and semantic representation. In Formal Semantics—The Essential Readings. Hoboken: Blackwell, pp. 189–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kamp, Hans. 1988. Discourse representation theory: What it is and where it ought to go. Natural Language at the Computer 320: 84–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kamp, Hans, and UI Reyle. 1993. From Discourse to Logic: Introduction to Modeltheoretic Semantics of Natural Language, Formal Logic and Discourse Representation Theory. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media, Volume 42. [Google Scholar]

- Kamp, Hans, Josef Van Genabith, and UI Reyle. 2011. Discourse representation theory. In Handbook of Philosophical Logic. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 125–394. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Graham. 2003. A modal account of the english present perfect puzzle. Semantics and Linguistic Theory 13: 145–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Katzir, Roni. 2007. Structurally-defined alternatives. Linguistics and Philosophy 30: 669–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Wolfgang. 1992. The present perfect puzzle. Language 68: 525–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Wolfgang. 1994. Time in Language. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kratzer, Angelika. 1998. More structural analogies between pronouns and tenses. Semantics and Linguistic Theory 8: 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzer, Angelika. 2004. Covert quantifier restrictions in natural languages. Paper presented at the Given at Palazzo Feltrenelli, Gargnano, Italy, June 11. [Google Scholar]

- Kratzer, Angelika. 2007. Situations in natural language semantics. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Summer 2019 ed. Edited by Edward N. Zalta. Stanford: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Available online: https://stanford.library.sydney.edu.au/archives/win2018/entries/situations-semantics/ (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Lascarides, Alex, and Nicholas Asher. 2008. Segmented discourse representation theory: Dynamic semantics with discourse structure. In Computing Meaning. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 87–124. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Charles N., and Sandra A. Thompson. 1989. Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press, vol. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Jo-Wang. 2006. Time in a language without tense: The case of chinese. Journal of Semantics 23: 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Jo-Wang. 2007. Predicate restriction, discontinuity property and the meaning of the perfective marker guo in mandarin chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 16: 237–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthewson, Lisa. 2006. Temporal semantics in a superficially tenseless language. Linguistics and Philosophy 29: 673–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthewson, Lisa. 2014. Mrs. smith’s Bad Say. Available online: http://www.totemfieldstoryboards.org (accessed on 16 September 2021).

- Matthewson, Lisa, Bruno Andreotti, Anne Bertrand, Heather Burge, Sihwei Chen, Joash Gambarage, Erin Guntly, Thomas J. Heins, Marianne Huijsmans, Kalim Kassam, and et al. 2017. Developing a perfect methodology. Paper presented at the Workshop on the Semantics of Verbal Morphology in Underdescribed Languages. University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, June 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Matthewson, Lisa, Sihwei Cheni, Marianne Huijsmans, Marcin Morzycki, Daniel Reisinger, and Hotze Rullmann. 2019. Restricting the english past tense. Snippets 37: 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCawley, James D. 1971. Tense and time reference in English. In Studies in Linguistic Semantics. Edited by Charles J. Fillmore and D. Terence Langèndoen. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- McCawley, James D. 1988. Adverbial nps: Bare or clad in see-through garb? Language 64: 583–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoard, Robert. 1978. The English Perfect: Tense-Choice and Pragmatic Inferences. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis, Laura A. 1994. The ambiguity of the english present perfect. Journal of Linguistics 30: 111–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, Marc, and Mark Steedman. 1988. Temporal ontology and temporal reference. Computational Linguistics 14: 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Musan, Renate. 2001. The present perfect in german: Outline of its semantic composition. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 19: 355–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, Atsuko. 2006. The Semantics and Pragmatics of the Perfect in English and Japanese. Buffalo: State University of New York at Buffalo. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, Atsuko, and Jean-Pierre Koenig. 2004. What is a perfect state. In WCCFL 23 Proceedings. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 101–13. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama, Atsuko, and Jean-Pierre Koenig. 2010. What is a perfect state. Language 86: 611–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Haihua, and Peppina Lee. 2004. The role of pragmatics in interpreting the chinese perfective markers-guo and-le. Journal of Pragmatics 36: 441–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancheva, Roumyana, and Arnim Von Stechow. 2004. On the present perfect puzzle. In Proceedings of NELS. Edited by Keir Mouton and Matthew Wolf. Amherst: Graduate Linguistic Student Association of the University of Massachusetts, vol. 34, pp. 469–84. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Terence. 1990. Events in the Semantics of English. Cambridge: MIT Press, vol. 334. [Google Scholar]

- Partee, Barbara Hall. 1973. Some structural analogies between tenses and pronouns in english. The Journal of Philosophy 70: 601–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partee, Barbara Hall. 1984. Temporal and nominal anaphora. Linguistics and Philosophy 7: 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percus, Orin. 2000. Constraints on some other variables in syntax. Natural Language Semantics 8: 173–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percus, Orin. 2006. Antipresuppositions. In Theoretical and Empirical Studies of Reference and Anaphora: Toward the Establishment of Generative Grammar as an Empirical Science. Edited by A. Ueyama. Report of the Grant-Aid for Scientific Research (B), Project No. 15320052. Tokyo: Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, pp. 52–73. [Google Scholar]

- Portner, Paul. 2003. The (temporal) semantics and (modal) pragmatics of the perfect. Linguistics and Philosophy 26: 459–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portner, Paul. 2011. Perfect and progressive. In Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning. Edited by Klaus Von Heusinger, Claudia Maienborn and Paul Portner. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 1217–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein, Björn. 2008. The Perfect Time Span: On the Present Perfect in German, Swedish and English. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, vol. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Sauerland, Uli. 2008. Implicated presuppositions. In The Discourse Potential of Underspecified Structures. Edited by Anita Steube. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 581–600. [Google Scholar]

- Schaden, Gerhard. 2009. Present perfects compete. Linguistics and Philosophy 32: 115–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, Florian. 2009. Two Types of Definites in Natural Language. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachussetts, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, Florian. 2013. Two kinds of definites cross-linguistically. Language and Linguistics Compass 7: 534–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharvit, Yael. 2014. On the universal principles of tense embedding: The lesson from before. Journal of Semantics 31: 263–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Raj. 2011. Maximize presupposition! and local contexts. Natural Language Semantics 19: 149–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Carlota S. 2013. The Parameter of Aspect. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media, vol. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Soh, Hooi Ling. 2009. Speaker presupposition and mandarin chinese sentence final le: A unified analysis of the change of state and the contrary to expectation reading. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 27: 623–57. [Google Scholar]

- Soh, Hooi Ling, and Meijia Gao. 2006. Perfective aspect and transition in mandarin chinese: An analysis of double-le sentences. Proceedings of the 2004 Texas Linguistics Society Conference, Austin, TX, USA, March 5–7; pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, Benjamin, and Yasutada Sudo. 2017. Presupposed ignorance and exhaustification: How scalar implicatures and presuppositions interact. Linguistics and Philosophy 40: 473–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spejewski, Beverly. 1997. The perfect, contingency, and temporal subordination. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 4: 9. [Google Scholar]

- Stalnaker, Robert. 2002. Common ground. Linguistics and Philosophy 25: 701–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Hongyuan. 2014. Temporal Construals of Bare Predicates in Mandarin Chinese. Ph.D. thesis, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- van der Klis, Martijn, Bert Le Bruyn, and Henriëtte de Swart. 2020. Tense use in discourse and dialogue: Prototypical and non-prototypical uses of the perfect. Paper presented at the Beyond Time 2 Workshop, Brussels, Belgium, February 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Klis, Martijn, Bert Le Bruyn, and Henriëtte De Swart. 2022. A multilingual corpus study of the competition between past and perfect in narrative discourse. Journal of Linguistics 58: 423–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Ruoying. forthcoming. The Past Tense as a Definite Description. Glossa: Definiteness and referentiality across languages.

- Zhao, Ruoying. n.d. Definiteness Effects and Competition in Tenses and Aspects. Ph.D. thesis, University College London, London, UK.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, R. Decomposing Perfect Readings. Languages 2022, 7, 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7040251

Zhao R. Decomposing Perfect Readings. Languages. 2022; 7(4):251. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7040251

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Ruoying. 2022. "Decomposing Perfect Readings" Languages 7, no. 4: 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7040251

APA StyleZhao, R. (2022). Decomposing Perfect Readings. Languages, 7(4), 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7040251