Perfective Marking in the Breton Tense-Aspect System

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| 1. | a | Tevel a | rankas | ur pennadig, | ha derc’hel | gant he frezegenn. (…) | |

| quieten VRP | must-SPST | a moment | and keep-INF | with his rant | |||

| b | Er skol | he devoa kavet | ar Potter-se, emezi. | ||||

| in school | meet-PST.PRF.3SG | this Potter, she.said | |||||

| c | Goude e | oant dimezet, | bet | ur mab dezho, | |||

| after VRP | marry-PST.PRF.3SG have-PST.PRF.3SG | a son to.them | |||||

| ha te | an hini ‘oa. | Gouzout a-walc’h | a raen | ||||

| and you | the one was. | Know well | VRP do- IPF.1SG | ||||

| e | vijes | bet evelto | ken iskis | ken amordinal. | |||

| VRP | be-COND.2SG | be-PST.PTCP same | as strange as | abnormal | |||

| d | A-benn ar fin ez | eus | be | unan bennak | |||

| in the end | VRP | be-PRS.PRF.3SG someone | |||||

| o lakaat | he c’harr | da darzhañ | |||||

| making | her car | to crash | |||||

| e | ha | degaset out bet | amañ. | ||||

| and | bring-PRS.PRF.2SG | here | |||||

She stopped to draw a deep breath and then went ranting on. (…)

‘Then she met that Potter at school and they left and got married and had you, and of course I knew you’d be just the same, just as strange, just as–as–abnormal–and then, if you please, she went and got herself blown up and we got landed with you !’2

2. Description of the Breton Verbal System

2.1. Note on the Status of Breton

| 2. | a | Town of Penmarch (West): |

| local spelling: bar skol neus ket desket brezoneg he | ||

| peurunvan: e-barzh ar skol n’hon eus ket desket brezhoneg heñ | ||

| ‘At school we didn’t learn Breton, eh ?’ | ||

| b | Town of Kervignac (East) | |

| local spelling: ouiañ ket petra e oè digoéheit. | ||

| peurunvan: n’ouzon ket petra a oa degouezhet. | ||

| ‘I don’t know what had happened.’ | ||

| c | Town of Locmariaquer (South-East) | |

| Er hig en deoé débet e oé brain. | ||

| Ar c’hig en doa/en devoa debret a oa brein. | ||

| ‘The meat he had eaten was bad.’ |

2.2. The Different Inflectional Classes of the Breton Verb

2.2.1. Simple Verb Structure

- -

- First, there is the basic (or impersonal) conjugation, in which the verb remains uninflected and the subject must be expressed and precede the verb; a verbal particle (a) indicates an obligatory syntactic relation (S-V or O-V).

| 3. | Buan e van-as | an itron kousket, | ||

| He gwaz | avat | a chome | dihun. | |

| her husband | however | VRP remain-IPF.3SG | awake | |

| ‘Mrs Dursley fell asleep quickly but Mr Dursley lay awake.’ | ||||

- -

- Then, there is also a marked (or personal) conjugation, in which the verb bears a person and number inflection, but the pronominal subject must not be expressed preverbally (it may be cliticized after the inflection, for emphasis); the verb is preceded by the verbal particle e10 or by a conjunction (tra ma, ‘as long as’ in (4)):

| 4. | War greñvaat | ez ae | tra ma | choment |

| on stronger | VRP go-IPF.3SG | as long as | remain-IPF.3PL | |

| da sellout war-du | an daou benn d’ar | straed. | ||

| to look at | the two ends of the | street | ||

| ‘It grew steadily louder as they looked up and down the street.’ | ||||

- -

| 5. | Mousc’hoarzhin a reas Dumbledore o welout pegen saouzanet e oa Harry.(…) | ||||||||

| Chom | a | ra-e | Harry | difiñv | ha | digomz | war e | wele. | |

| remain VRP | do-IPF.3SG Harry | motionless and speechless on his bed. | |||||||

| ‘Dumbledore smiled at the look of amazement on Harry’s face. (…) Harry lay there, lost for words.’ | |||||||||

2.2.2. Compound Tenses

| 6. | Lavaret en deus: | « Ha Harry zo aet | war e lec’h, neketa? » |

| say-PRS.PRF.3SG | and Harry is gone | after him, isn’t he | |

| ‘He just said, “Harry’s gone after him, hasn’t he?”’ | |||

| 7. | Setu dres pezh | am eus lavaret | d’ar | c’helenner Dumbledore. | |

| here just thing | say-PRS.PRF.1SG to the | professor Dumbledore | |||

| ‘That’s what I said to Dumbledore.’ | |||||

2.2.3. Periphrastic Structures

| 8. | An holl | gelennerien all | a soñje ganto | edoSnape | o klask |

| the whole teachers all | VRP think-IPF | be-IPF Snape | PROG try | ||

| mirout ouzh ar Gripi-Aour | da c’hounit. | ||||

| stop | the Gryffindor | to win | |||

| ‘All the other teachers thought Snape was trying to stop Gryffindor winning.’ | |||||

| 9. | Hejet em eus | Ron, | ur pennad brav on | bet | oc’h ober, |

| shake-PRS.PRF.3SG Ron | a moment good | be-PRS.PRF.1SG PROG do | |||

| Ha disemplañ | en devoa graet. | ||||

| and come.round-INF do-PST.PRF.3SG | |||||

| ‘I brought Ron round–that took a while.’ | |||||

| 10. | a | Lazh anezhañ | neuze, genaoueg | Echu an abadenn!” | a wic’has | Voldemort. | ||

| kill him | then, fool | finished the game | VRP screech-SPST.3SG V. | |||||

| b | HaQuirrell da sevel | E zorn | da deurel mallozh | ar marv | warnañ, | |||

| and Quirrell to raise-INF his hand | to perform curse | the death | on.him | |||||

| c | met Harry, | hep | gouzout dezhañ, | a lakaas | ||||

| But Harry | without | realizing | VRP throw-SPST.3SG | |||||

| E zaouarn | war dremm | ar c’helenner. | ||||||

| his hands | on face | the teacher | ||||||

| ‘Then kill him, fool, and be done!’ screeched Voldemort. | ||||||||

| Quirrell raised his hand to perform a deadly curse, but Harry, by instinct, reached up and grabbed Quirrell’s face –‘ | ||||||||

2.3. The Tense-Aspect System of Breton

| 11. | a | Gantañ e | oan en em gavet | ||||

| with.him VRP | meet-PST.PRF.1SG | ||||||

| ‘I met him…’ | |||||||

| b | Pa oan | o | vale | dre ar bed. | Un den diboell a | oan | |

| when I.was PROG travel.INF through the world. A man foolish VRP be-IPF.1SG | |||||||

| neuze, leun a vennozhioù diot diwar-benn ar mad hag an droug. | |||||||

| ‘… when I travelled around the world. A foolish young man I was then, full of ridiculous ideas about good and evil.’ | |||||||

| C | Met Lord Voldemort an hini | en deus diskouezetdin pegen bras e oa | ma fazi. | ||||

| But Lord Voldemort the one show-PRS.PRF.3SG me how big VRP was my mistake | |||||||

| ‘Lord Voldemort showed me how wrong I was. (…) | |||||||

| d | Abaoe an amzer-se em eus e | servijet | ez-leal, | ||||

| since that time | serve-PRS.PRF.3SG.1SG faithfully | ||||||

| petra bennak ma | ’m eus e zilezet | dre veur a wech. | |||||

| Although | let.down-PRS.PRF.3SG.1SG many times | ||||||

| ‘Since then, I have served him faithfully, although I have let him down many times.’ | |||||||

| E | Garv ouzhin-me en deus | ranket | bezañ.” | ||||

| Hard on.me | must-PRS.PRF.3SG be.INF | ||||||

| A-greiz-holl e redas | ur gridienn | dre e gorf. | |||||

| Suddenly | VRP run-SPST.3SG a shiver through his body | ||||||

| “Pardoniñ ar fazioù ne ra eta es. | |||||||

| ‘He has had to be very hard on me.’ Quirrell shivered suddenly. ‘He does not forgive mistakes easily.’ | |||||||

3. Materials, Methods, and Preliminary Results

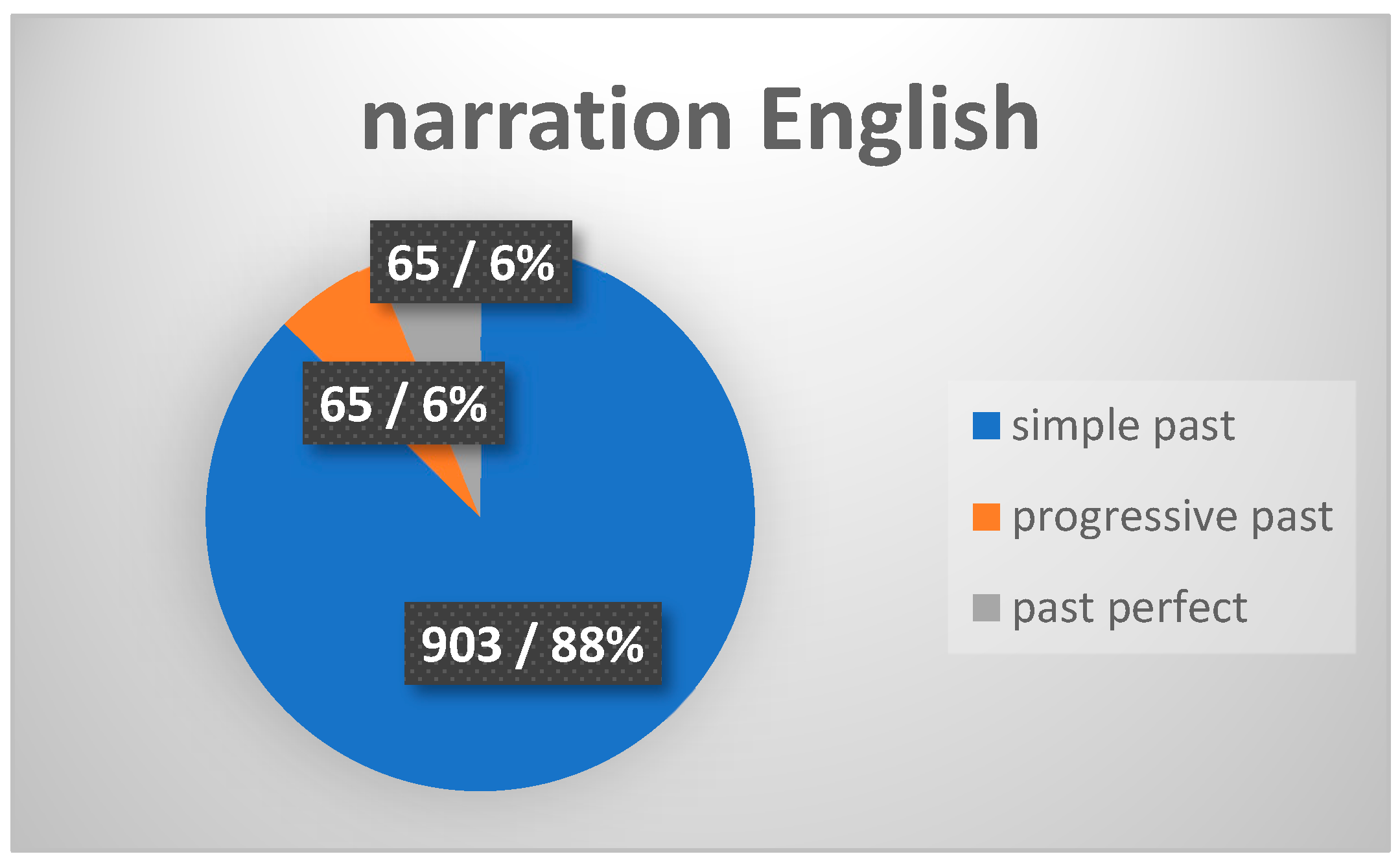

3.1. Corpus A: Narrative Discourse

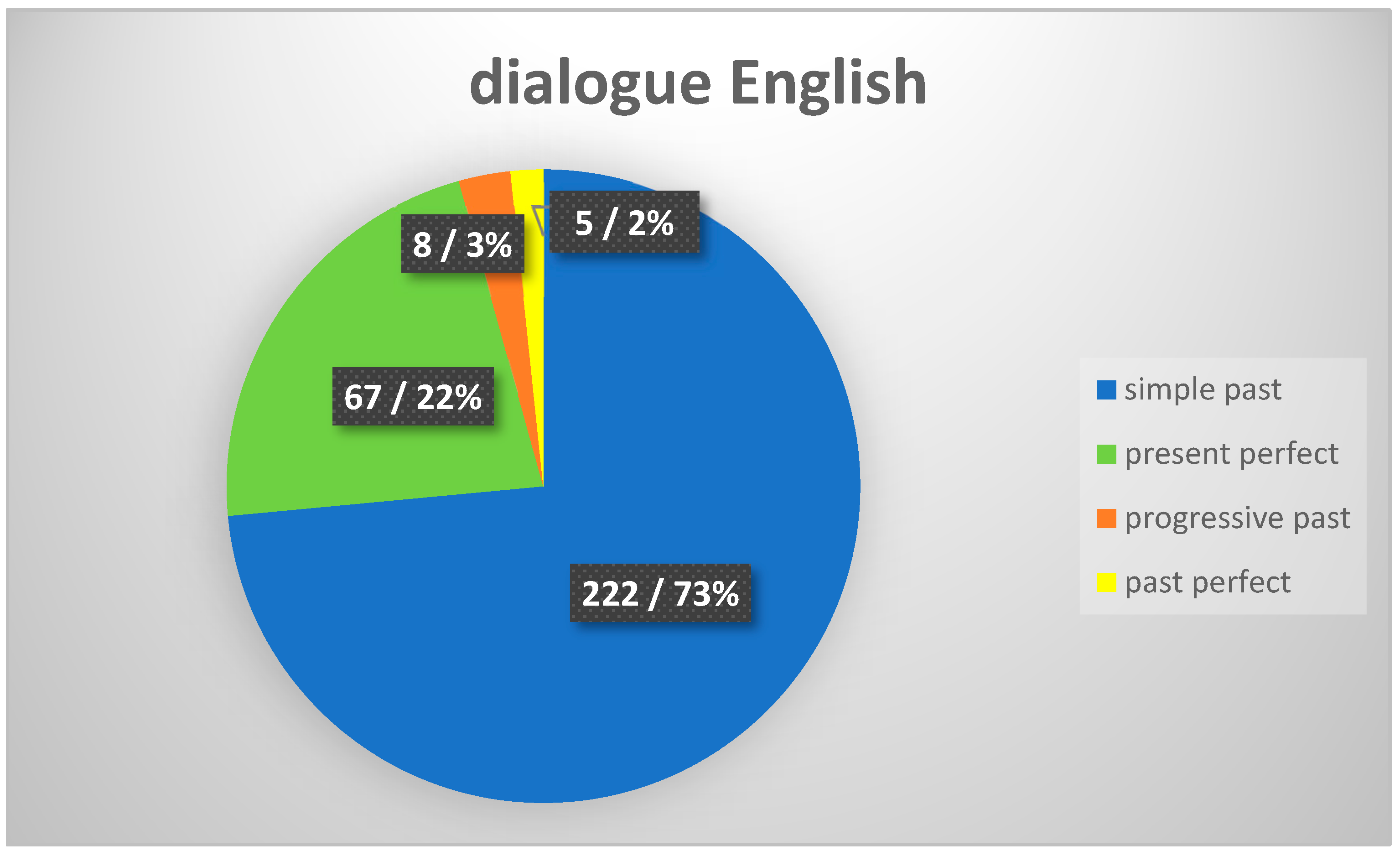

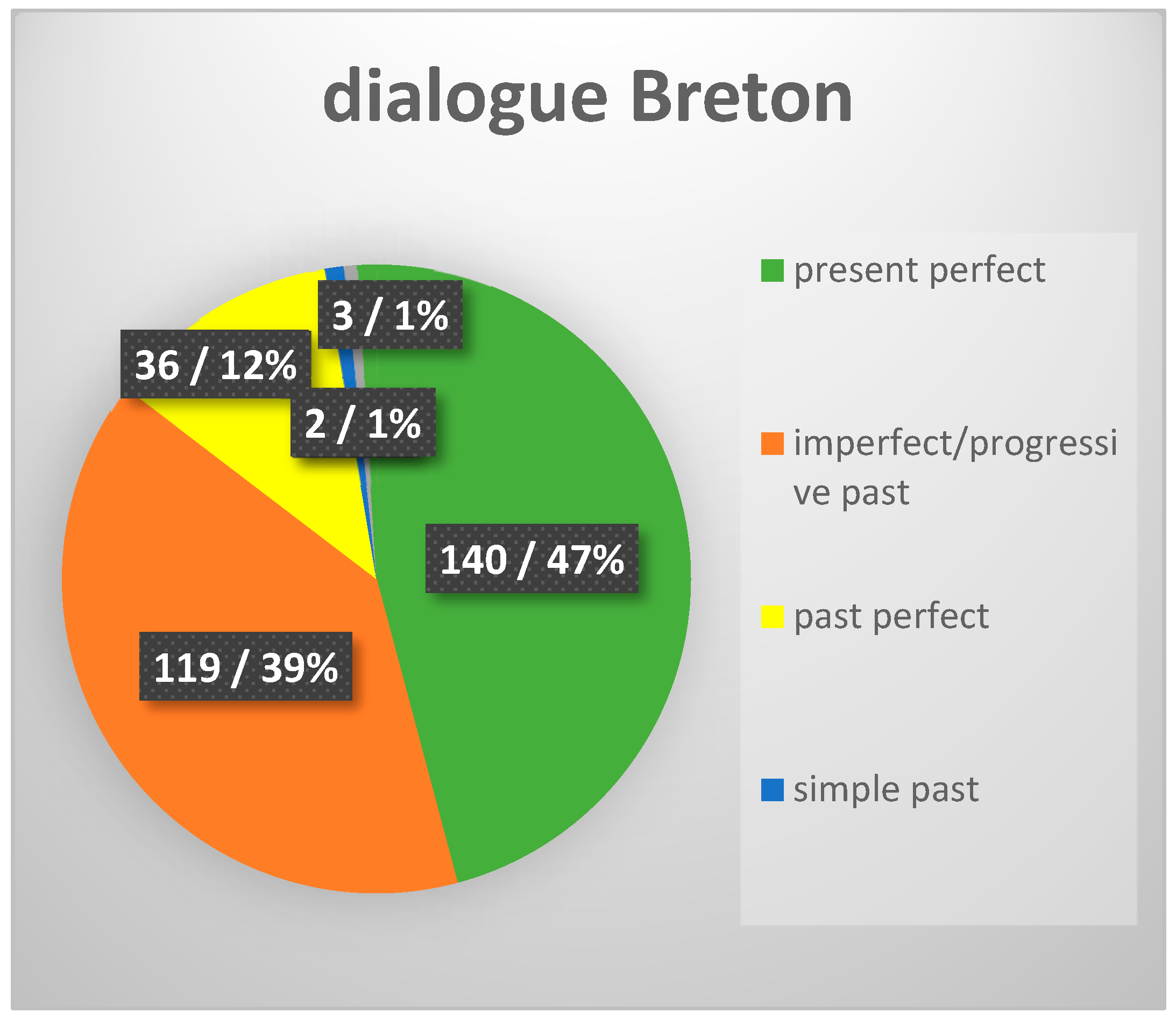

3.2. Corpus B: Dialogue with Weak Narration

- English SPST → Breton PRS.PRF/imperfect (states)/PST.PRF

- English PRS.PRF → Breton PRS.PRF

| 12. | ‘Did you never wonder where yer parents learnt it all ?’ | ||||

| ‘Feusket klasket | biskoazh | goût | |||

| try-PRS.PRF.2SG NEG | never | know | |||

| p’lec’h ’oa bet | da dud | ‘tiskiñ | ‘n traoù-se ? | ||

| where be-PST.PRF.3SG | your parents | PROG learn | those things | ||

| 13. | ‘An’ it’s your bad luck you grew up in a family o’ the biggest Muggles I ever laid eyes on.’ | |||

| Feus | ket a chañs | ‘vezañ degouezhet e tiad | ar gwashañ Mougouled | |

| you.have NEG the luck | be raised in family | the biggest Muggles | ||

| zo bet | biskoazh | er vro. | ||

| be-PRS.PRF never | in.the country | |||

| 14. | ‘He’s going to Stonewall High and he’ll be grateful for it. I’ve read those letters and he needs all sorts of rubbish’ | ||||

| Mont a raio da skolaj ar Poull-Fank, ha gwelloc’h dezhañ bezañ anaoudek. | |||||

| Lennet em eus | ho lizhiri | ha | gwelet em eus | ||

| read-PRS.PRF.1SG their letters | and | see-PRS.PRF.1SG | |||

| peseurt garzaj | en dije | da brenañ. | |||

| What rubbish | he would.have | to buy | |||

| 15. | ‘It was on their news.’ She jerked her head back at the Dursleys’ dark living-room window. ‘I heard it.’ | ||

| Er c’heleier zoken ez eus bet kaoz eus se.” Gant he fenn e tiskouezas prenestr saloñs an tiegezh Dursley, a oa en deñvalijenn. | |||

| “Kement-se | am eus klevet | ma-unan. | |

| that.much | hear-PRS.PRF.1SG | myself | |

| 16. | a | Ha | pelec’h hoc’h eus | kavetar marc’h-tan-se?” | |||

| and | where get-PRS.PRF.2PL this motorbike | ||||||

| “Amprestet eo, | Kelenner | Dumbledore, Aotrou,” | |||||

| borrowed it.be-PRS.3SG | Professor | Dumbledore sir | |||||

| a respontas ar ramz, en ur ziskenn goustadik, gant evezh, diwar ar marc’h-tan. | |||||||

| b | Digant ar skoliad Sirius Black, | a zo | bet tapetganin | hiriv.” | |||

| from the pupil Sirius Black VRP obtain-PASS.PRS.PRF.3SG by.me | today | ||||||

| ‘And where did you get that motorbike?’ | |||||||

| ‘Borrowed it, Professor Dumbledore, sir,’ said the giant, climbing carefully off the motorbike as he spoke. ‘Young Sirius Black lent it me. I’ve got him, sir.’ | |||||||

| 17. | Touet hon eus, | pa hon eus en kemeret | ganimp, |

| swear-PRS.PRF.1PL when take-PRS.PRF.1PL | with.us | ||

| lakaat fin | d’an drocherezh-se, | ||

| put end to | that rubbish, | ||

| eme Donton Vernon. Touet | disober eus an holl draoù-se. | ||

| said Uncle Vernon. swear-PRS.PRF to | undo of all these things | ||

| ‘We swore when we took him we’d put a stop to that rubbish,’ said Uncle Vernon, ‘swore we’d stamp it out of him.’ | |||

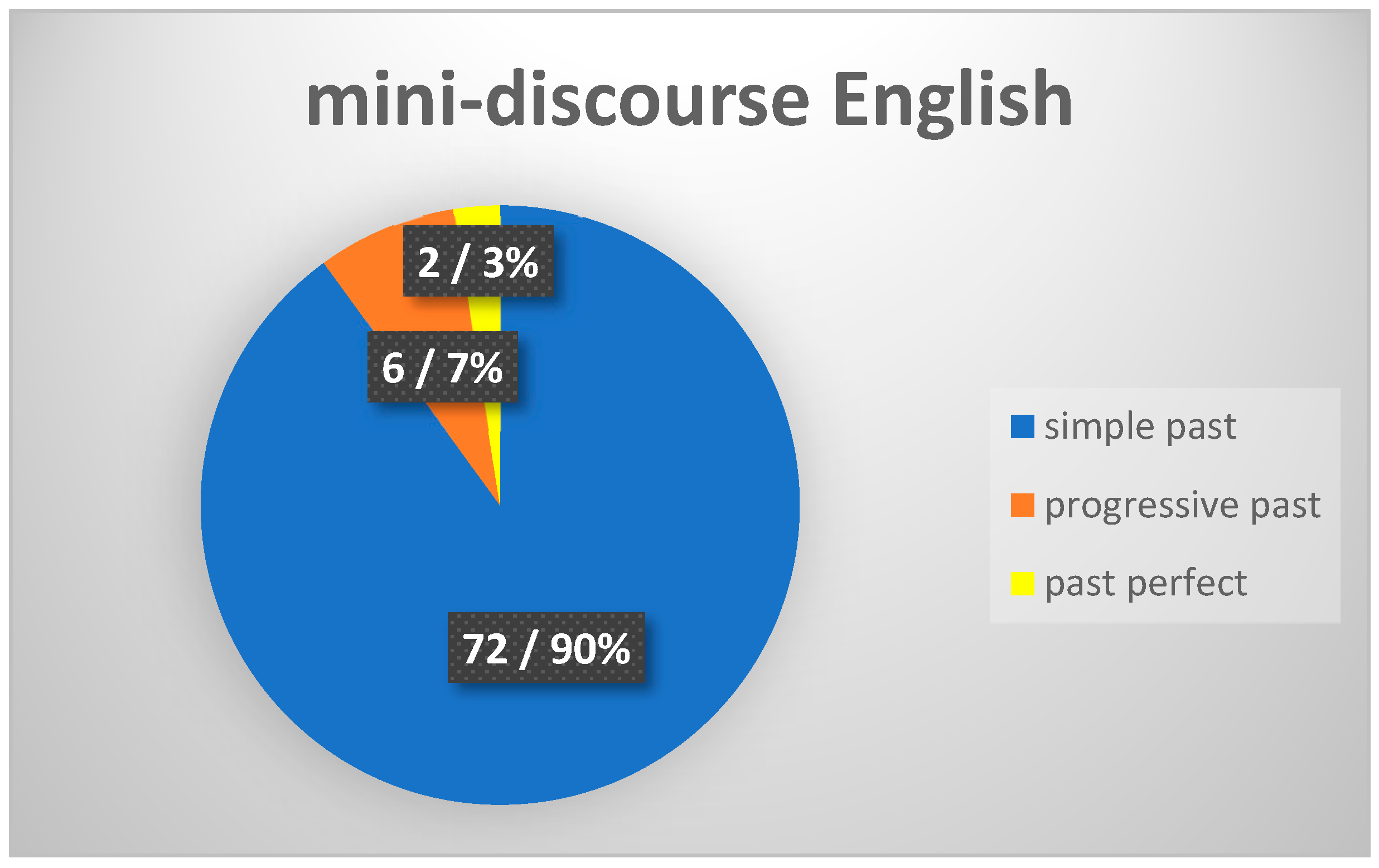

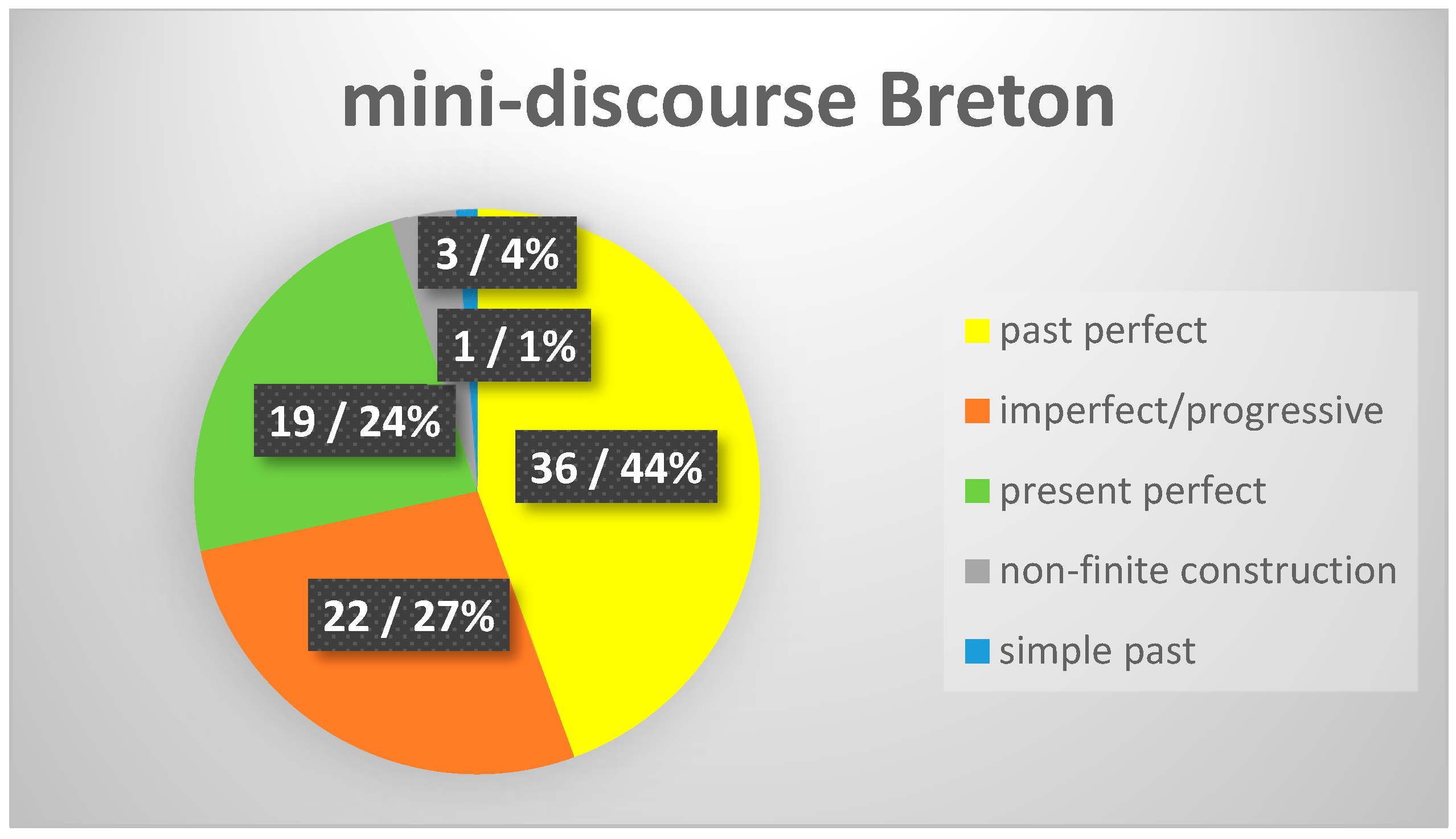

3.3. Corpus C: Mini-Discourse in Dialogue

| 18. | a | “Hervez a gonter, | e oa en em gavet | Voldemort | dec’h | e Godric’s | Hollow |

| as they say | VRP turn.up-PST.PRF.3SG | Voldemort | yesterday | in Godric’s | Hollow | ||

| b | Aet e oa | da-gaout | ar Bottered. | Hervez | ar vrud | ||

| go-PST.PRF.3SG | to get | the Potters. | According.to | the rumour | |||

| eo... | marv... | Lily ha | James Potter. | ||||

| be-PRS.3SG | dead | Lily and | James Potter. | ||||

| c | “Gwashoc’h zo | c’hoazh. Lavaret e vez | en devoa klasket | lazhañ o mab | Harry | ||

| Worse there.is | still said it.is | try-PST.PRF.3SG | kill | their son | Harry | ||

| d | met ne oa ket | betgouest | d’ober. | ||||

| but NEG be-PST.PRF.3SG | able | to do. | |||||

| Ne | oaket deuet a-benn | da lazhañ | ar paotrig-se. | ||||

| NEG | manage-PST.PRF.3SG | to kill | that little.boy | ||||

| e | “Ha gwir eo se?” a valbouzas ar gelennerez McGonagall. | ||||||

| “Goude an holl | daolioù en deus graet... | An holl dud | en deus lazhet... | ||||

| after the whole things do-PRS.PRF.3SG the whole people kill-PRS.PRF.3SG | |||||||

| f | n’ eo ket | betgouest | da lazhañ | ur paotrig? | |||

| NEG be-PRS.PRF.3SG | able to kill | a little.boy | |||||

| Sed a zo saouzanus... netra ne c’halle mirout outañ a-raok... | |||||||

| g | Met penaos | ma Doue en deus gallet Harry chom bev?” | |||||

| But how | my God can-PRS.PRF.3SG Harry stay alive | ||||||

‘What they’re saying,’ she pressed on, ‘is that last night Voldemort turned up in Godric’s Hollow. He went to find the Potters. The rumour is that Lily and James Potter are–are–that they’re–dead.’ (…) ‘That’s not all. They’re saying he tried to kill the Potters’ son, Harry. But–he couldn’t. He couldn’t kill that little boy. (…)

‘It’s–it’s true?’ faltered Professor McGonagall. ‘After all he’s done … all the people he’s killed … he couldn’t kill a little boy? It’s just astounding … of all the things to stop him … but how in the name of heaven did Harry survive?’

- ➢

- With the PST.PRF:

- -

- The main locating specific past time adverbials found are: dec’h, ‘yesterday’; ur wech e oa, ‘there was once’; en noz-se, ‘that night’.

- -

- The when-clause types are: (un deiz) pa, ‘(one day) when’; abaoe an deiz ma, ‘since the day when’; diwezhañ ma, ‘the last time that’; en noz end-eeun ma, ‘the same night when’.

- -

- The connectives are: a-raok, ‘before’; (ha) goude, ‘(and) afterwards’; neuze, ‘then’.

- ➢

- With the PRS.PRF:

- -

- Specific past time adverbials: n’eus ket pell zo, ‘not, long ago’.

- -

- A few connectives: da gentañ, ‘at first’; neuze, ‘then’; a-benn ar fin, ‘in the end’.

4. Discussion

| 19. | a | Me a | wele | dec’h | war ar | journal, |

| I VRP | see-IPF.3SG | yesterday | in the | paper | ||

| hiziv ne | ‘m eus ket bet | amzer | da lenn, | |||

| today NEG have-PRS.PRF.1SG time | to read | |||||

| b | mes dec’h | em eus lennet | un tammig ha | neuze... | ||

| but yesterday read-PRS.PRF.1SG | a bit and | then | ||||

| beñ | int | en em glemm | dija, | |||

| well | they | complain-PRS | already… | |||

| ‘I saw that yesterday in the paper, today I didn’t have time to read, but yesterday I read a bit, and then… they’re already complaining…’ | ||||||

| 20. | a | Ma niz eo, | hag … a | oa dle dezhañ | dont | |

| my nephew it.is and VRP | must-IPF.3SG come | |||||

| abalamour | eñ en deus komañset | troc’hañ | an han-, | |||

| because | he begin-PRS.PRF.3SG | cut | the hedge | |||

| ma hae neuze evit serriñ tout an traoù… | ||||||

| b | Mes eñ n’ en doa ket | telefonet | din | an deiz, | ||

| but he NEG | telephone-PST.PRF.3SG to.me that day | |||||

| heu, ma, pas | dec’h, | an deiz e-raok… | ||||

| Er but NEG | yesterday | the day before | ||||

‘Itssss’s my nephew, and… He was supposed to come because he’s started cutting the… my hedge, to collect the whole thing… But he didn’t call me on that day, eh, not yesterday, but the day before.’

| 21. | a | Neuze e | oamp aet | d’an daoulamm da borzh ar c’haouenned | |

| then VRP go-PST.PRF.1PL | at a run | to port of owls | |||

| da gas un tamm lizher d’ar c’helenner Dumbledore, | |||||

| b | Ha kavet hon eus | anezhañ | war an hent, en Trepas Bras. | ||

| and find-PRS.PRF.1PL | him | on the road in Entrance Hall | |||

| ‘… and we were dashing up to the owlery to contact Dumbledore when we met him in the Entrance Hall.’ | |||||

| 22. | [7] |

| a-Guy experienced a lovely evening last night. b-He had a fantastic meal. c-He ate salmon. d-He devoured lots of cheese. |

| 23. | a | Me | zo bet savet | gant ma mamm-gozh… | |

| 1SG | raise-PASS.PRS.PRF. | by my grandmother | |||

| b | Hag ur wech en devoa skoet ac’hanon | er mor diwar-lein beg ar c’hae, e Blackpool | |||

| and one time push-PST.PRF.3SG me | in sea off end of pier | in Blackpool | |||

| c | Darbet e oa bet | din bezañ beuzet. | |||

| be on the verge-PST.PRF.3SG | to.me be drowned | ||||

| d | Netra ne | c’hoarvezas | a-raok ma’m boa tapet | ma eizh vloaz. | |

| nothing NEG happen-SPST.3SG before that get-PST.PRF.1SG my eight years | |||||

| e | Un deiz e | oa deuet | ma eontr-kozh | Algie… | |

| one day VRP | come-PST.PRF.3SGF my great-uncle | Algie | |||

‘Well, my gran brought me up and she’s a witch… he [a great-uncle] pushed me off the end of Blackpool pier once, I nearly drowned–but nothing happened until I was eight. Great-uncle Algie came round for tea…’

| 24. | a | Da noz Kala-goañv en devoa klasket tremen dirak | ar c’hi | e dri fenn! | ||||

| at Halloween try-PST.PRF.3SG pass | before the dog | of three heads | ||||||

| b | Setu da belec’h ‘oa ‘vont | pa | hor boa gwelet | anezhañ. | ||||

| this to where go-PST.PROG.3SG | when see-PST.PRF.1PL him | |||||||

| ‘He tried to get past that three-headed dog at Halloween. That’s where he was going when we saw him.’ | ||||||||

| 25. | a | Snape n’ | en devo nemet lavarout ne | oar ket | ||

| Snape NEG have.to only say | NEG know-PRS.3SG | |||||

| b | Penaos eo deuet | an troll e-barzh | ar skol | da Gala-goañv | ||

| how | come-PRS.PRF.3SG the troll into | the school | at Halloween | |||

| c | ha | n’ | en deusket taolet troad ebet en trede estaj. | |||

| and | NEG | set.foot-PRS.PRF.3SG none in third floor | ||||

‘Snape’s only got to say he doesn’t know how the troll got in at Hallowe’en and that he was nowhere near the third floor…’

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The abbreviations used in this article for the morphological gloss of the examples are the following: INF (infinitive), IPF (imperfect), PASS (passive), PROG (progressive), PRS.PRF (present perfect), PST.PRF (past perfect), PST.PTCP (past participle), SPST (simple past), and VRP (verbal particle). We put in boldface the past forms of the verbs in the examples, both in English and in Breton. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | The translator made a few changes in this passage: he chose not to mention an explosion, as in the original, but instead presented the event as a car crash. Excerpt (e) literally reads: ‘in the end there has been someone making her car crash.’ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | The two authors do not say anything about the English pluperfect: their focus is exclusively on Romance languages. Becker (2020) contrasts the use of the three available perfect(ive) tenses (simple past, present perfect, past perfect) in Spanish, French and Italian. He concludes that contrary to Spanish and French, where the past perfect does not yet have the ability to « create per se a narrative discourse structure » (278), the Italian past perfect offers a possibility for propelling the action forward, it has a ‘propulsive capacity’ (294). A full comparison of the Italian past perfect with the Breton, however, is outside the scope of this paper. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | https://time-in-translation.hum.uu.nl/, accessed on 1 January 2022. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Banque Sonore des Dialectes Bretons. Conception: Adrien Desseigne; comité d’édition: Loïc Cheveau, Adrien Desseigne, Pierre-Yves Kersulec. Available online: http://banque.sonore.breton.free.fr/index.html (accessed on 1 January 2022). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Welsh, a Celtic language of the same family as Breton, does not have a have/be perfect, but for the perfect function it uses an aspectual particle, wedi, homophonous with the preposition wedi, ‘after’, followed by an infinitive verb. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | ‘Imperfect’ is the name given to one of the six synthetic (i.e., non-periphrastic) tenses of Breton, which are: the present, future, preterite (our SPST), imperfect, ‘potential’ conditional, and ‘hypothetical’ conditional. (Hewitt 2002, p. 2). The Breton imperfect has roughly the same uses as the imperfects of Romance (French, Spanish, Italian): it is used mainly for stative, progressive, and habitual situations, i.e., it is an imperfective tense-aspect. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | The term peurunvan means ‘totally unified’ in Breton. The history of the unification of Breton orthography is a long one, with many different versions. Suffice it to say that two dialects in particular served as a model for written Breton: Léonais (North-West) and Haut-Vannetais (South-East). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | According to Bottineau (2010), the ‘focal’ of the Breton sentence is the constituent that is information-structurally a focus, corresponding to either the explicit or implicit answer to a question originating from the addressee in the preceding discourse in an interaction; it has syntactic consequences on the sentence, as the different forms of the verb are sensitive to selection of the focal. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | The particle e is chosen over a to indicate that the preceding term is neither a subject nor a direct object. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | Breton is known for its several morphemes corresponding to the verb be, the choice of which depends on many factors (semantic and discourse configurational, mainly): invariable zo (which requires that its subject precede it), variable eo (third person present)/oa (third person past) for all other cases; situative emañ (present)/edo (past) if the subject is definite; habitual vez. All these forms except eo can be found in the progressive construction. For more information on Breton auxiliary constructions, see Corre (2005). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | As suggested by one of the editors, the use of the SPST in English, which lacks grammatical aspect, might be a default use in (11c), independently of relations with the Speech time. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Borillo et al. (2004), borrowing this temporal constraint from Lascarides and Asher (1993) and Caenepeel (1995), indicate that ‘this does not mean that there should be no interval of time between the two events e1 and e2, but rather that no relevant event can occur during this interval.’ (318). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | http://banque.sonore.breton.free.fr/index_en.html accessed on 1 January 2022, presentation page. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15 | Partee (1973) has shown that the past tense in English behaves like a deictic expression; a sentence in the simple past can be uttered out of the blue, to refer to a contextually salient (past) moment (as in John went to Harvard; I didn’t turn off the stove); also, Schaden (2008) p. 10), following comments by Kratzer (1998), argues that in sentences like I won! or Boromini built this church, English may have a ‘Hot News’ component of meaning, unavailable in French and German, for example, as well as in Breton, for the SPST. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | As suggested by one of the editors, these contexts are reminiscent of the « anti-presuppositional nature » of the PRS.PRF (Michaelis 1994; van der Klis et al. 2021). The resultative PRS.PRF has an event-reporting function in excerpt (16) and is not anaphorically linked to a previous event (it is non-presuppositional in that sense). In the next section, we see that when further information is provided about a pragmatically presupposed event, that is where we find the PST.PRF in Breton (which is what the SPST does in English) (Michaelis 1994, pp. 143–44). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | However, in another passage of the book, we find the same comment by Uncle Vernon about swearing to get magic out of Harry, but in the PST.PRF:

Didn’t we swear when we took him in we’d stamp out that dangerous nonsense? (44):(42). The difference is that here, Vernon is reminding (Soñj mat ‘teus, ‘you have good memory’) his interlocutor (Aunt Petunia) of the already known past event, which he feels obliged to reconstruct sequentially, and that is enough to trigger the use of the PST.PRF. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | As indicated in De Swart (2007, p. 2274), we owe to Boogaart and Ursula (1999) the observation that a tense which is used in a temporal clause headed by when is diagnostic of narrative use. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | Thanks to Henriette de Swart (p.c.) for suggesting this explanation. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | ‘The topic of a segment is the overarching description of what the segment is about’. (Lascarides and Asher 1993, p. 20). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | p.c. (2019). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Apothéloz, Denis. 2016. Sémantique du passé composé en français moderne et exploration des rapports passé composé/passé simple dans un corpus de moyen français. In Aoristes et Parfaits. Edited by Pierre-Don Giancarli and Marc Fryd. Leiden: Brill Rodopi, pp. 199–246. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, Martin. 2020. The Pluperfect and its discourse potential in contrast. Revue Romane. Langue et Littérature. International Journal of Romance Languages and Literatures 56: 267–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benveniste, Emile. 1966. Problèmes de Linguistique Générale. Paris: Gallimard, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bertinetto, Pier-Marco. 2010. Non-conventional uses of the Pluperfect in the Italian (and German) literary prose. Quaderni del laboratorio di linguistica 9: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Boogaart, Ronny, and Johannes Ursula. 1999. Aspect and Temporal Ordering: A Contrastive Analysis of Dutch and English. Ph.D. dissertation, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Borillo, Andrée, Bras Myriam, Le Draoulec Anne, Vieu Laure, Molendijk Arie, de Swart Henriette, Verkuyl Henk, Vet Co, and Carl Vetters. 2004. Tense, connectives and discourse structure. In Handbook of French Semantics. Edited by Francis Corblin and Henriette de Swart. Stanford: CSLI Publications, pp. 309–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bottineau, Didier. 2010. Les temps du verbe breton: Temps, aspect, modalité, interlocution, cognition–des faits empiriques aux orientations théoriques. In Système et Chronologie. Edited by Catherine Douay. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, pp. 129–57. [Google Scholar]

- Brinton, Laurel. 1988. The Development of English Aspectual Systems: Aspectualizers and Post-Verbal Particles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bybee, Joan, Revere Perkins, and William Pagliuca. 1994. The Evolution of Grammar: Tense, Aspect, and Modality in Languages of the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caenepeel, Mimo. 1995. Aspect and text Structure. Linguistics 33: 213–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corre, Éric. 2005. L’auxiliarité en anglais et en breton. Le cas de do et d’ober. Cercles, Occasional Papers Series, Revue Pluridisciplinaire du Monde Anglophone. pp. 27–52. Available online: www.cercles.com (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Corre, Eric. 2021. Le Marqueur Grammatical de L’habitude en Breton–le Verbe bez/vez. Lille: Presses Universitaires de Lille, to appear. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, William. 2012. Verbs: Aspect and Causal Structure. Oxford: Oxford Linguistics. [Google Scholar]

- Davalan, Nickolaz. 2017. Méthode de Breton–Brezhoneg Hentenn Oulpan. Rennes: Skol an Emsav. [Google Scholar]

- De Swart, Henriette. 2007. A cross-linguistic discourse analysis of the Perfect. Journal of Pragmatics 39: 2273–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Swart, Henriette. 2021a. Intermediate Perfects, Joint Work with Teresa Maria Xiqués and Eric Corre. Talk Presented at the Workshop New Perspectives on Aspect: From the ‘Slavic Model’ to Other Languages, Paris, France, April 8. Available online: https://time-in-translation.hum.uu.nl/news/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- De Swart, Henriette. 2021b. Tense Use in Discourse and Dialogue: A Parallel Corpus Approach. Talk at ZAS Berlin, December 8. [Google Scholar]

- Desbordes, Yann. 1983. Petite Grammaire du Breton Moderne. Lesneven: Mouladurioù hor yezh. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, Martín, and Paz González. 2022. Perfect-Perfective Variation across Spanish Dialects: A Parallel-Corpus Study. Languages 7: 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favereau, Francis. 1987. Etre dec’h Hag Arc’hoazh. Morlaix: Skol Vreizh. [Google Scholar]

- Hemon, Roparz. 1975. A Historical Morphology and Syntax of Breton. Dublin: Institute for Advanced Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, Steve. 1990. The progressive in Breton in the light of the English progressive. In Celtic Linguistics: Readings in the Brythonic Languages. Edited by Martin J. Ball, James Fife, Erich Poppe and Jenny Rowland. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt, Steve. 2002. The Impersonal in Breton. JCeltL 7: 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, Paul. 1982. Aspect Between Discourse and Grammar: An Introductory Essay for the Volume. In Tense-Aspect–Between Semantics and Pragmatics. Edited by by Paul J. Hopper. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, Koko. 1979. An Analysis of the English Present Perfect. Linguistics 17: 561–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kervella, Frañsez. 1976. Yehzadur Bras ar Brezhoneg. Brest: Al Liamm. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Wolfgang. 1994. Time and Language. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Koss, Tom, Astrid De Wit, and Johan van der Auwera. 2022. The Aspectual Meaning of Non-Aspectual Constructions. Languages 7: 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzer, Angelika. 1998. More structural analogies between pronouns and tenses. In Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistics Theory (SALT), 8th ed. Edited by Devon Strolovitch and Aaron Lawson. Washington, DC: Linguistic Society of America, pp. 92–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lascarides, Alex, and Nicholas Asher. 1993. Temporal interpretation, discourse relations and commonsense entailment. Linguistics and Philosophy 16: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Bruyn, Bert, Martijn van der Klis, and Henriëtte de Swart. 2019. The Perfect in dialogue: Evidence from Dutch. In Linguistics in the Netherlands 2019. Edited by Janine Berns and Elena Tribushinina. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 162–75. [Google Scholar]

- Le Bruyn, Bert, Martín Fuchs, Martijn van der Klis, Jianan Liu, Chou Mo, Jos Tellings, and Henriëtte de Swart. 2022. Parallel Corpus Research and Target Language Representativeness: The Contrastive, Typological, and Translation Mining Traditions. Languages 7: 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Cawley, James. 1971. Tense and Time Reference in English. In Studies in Linguistic Semantics. Edited by Charles J. Fillmore and D. Terence Langendoen. NewYork: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- McCoard, Robert. 1978. The English Perfect: Tense-Choice and Pragmatic Inferences. Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis, Laura A. 1994. The ambiguity of the English present perfect. Journal of Linguistics 30: 111–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nishiyama, Atsuko, and Jean-Pierre Koenig. 2010. What Is a Perfect State? Language 86: 611–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partee, Barbara H. 1973. Some structural analogies between tenses and pronouns in English. The Journal of Philosophy 70: 601–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portner, Paul. 2003. The temporal semantics and the modal pragmatics of the perfect. Linguistics and Philosophy 26: 459–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichenbach, Hand. 1947. Elements of Symbolic Logic. New York: MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, Martin, Jean-Christophe Pellat, and René Rioul. 1994. Grammaire Méthodique du Français. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. [Google Scholar]

- Rouveret, Alain. 1994. Syntaxe du gallois: Principes Generaux et Typologie. Paris: Editions du CNRS. [Google Scholar]

- Rowling, Joanne Kathleen. 1997. Harry Potter, The Philosopher’s Stone (Chapters 1, 4 and 17). London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Rowling, Joanne Kathleen. 2012. Harry Potter ha Maen ar Furien (Chapters 1, 4 and 17). Translated by Mark Kerrain. Pornizh: An Amzer Embanner. [Google Scholar]

- van der Klis, Martijn, Bert Le Bruyn, and Henriette de Swart. 2021. A multilingual corpus study of the competition between past and perfect in narrative discourse. Journal of Linguistics 58: 423–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaden, Gerhard. 2008. On the Cross-Linguistic Variation of ’One-Step Past-Referring’ Tenses. Proceedings of SuB 12. Oslo: ILOS, pp. 537–51. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Carlota. 2003. Modes of Discourse. The Local Structure of Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

| Perfect Type: | Number of Tokens: |

|---|---|

| Present—Continuative | 26 |

| Present—Experiential | 5 |

| Present—Resultative | 28 |

| Perfect Type: | Number of Tokens: |

|---|---|

| Continuative | 13 |

| Experiential | 19 |

| Resultative | 81 |

| ’weak’ narration | 20 |

| Other (infinitive, conditional, future) | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corre, É. Perfective Marking in the Breton Tense-Aspect System. Languages 2022, 7, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030188

Corre É. Perfective Marking in the Breton Tense-Aspect System. Languages. 2022; 7(3):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030188

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorre, Éric. 2022. "Perfective Marking in the Breton Tense-Aspect System" Languages 7, no. 3: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030188

APA StyleCorre, É. (2022). Perfective Marking in the Breton Tense-Aspect System. Languages, 7(3), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030188