Abstract

This paper investigates the meaning of a specific intonation contour called linear lengthening intonation (LLI), which is found in the northern Australian language Iwaidja. Using an experimental field work approach, we analysed approximately 4000 utterances. We demonstrate that the semantics of LLI is broadly event-quantificational as well as temporally scalar. LLI imposes aspectual selectional restrictions on the verbs it combines with (they must be durative, i.e., cannot describe ‘punctual’, atomic events), and requires the event description effected by said verbs to exceed a contextually determined relative scalar meaning. Iwaidja differs from other northern Australian languages with similar intonation patterns in that it does not seem to have any argument NP-related incremental or event scalar meaning. This suggests that LLI is a decidedly grammatical, language-specific device and not a purely iconic kind of expression (even though it also possibly has an iconic dimension).

1. Introduction

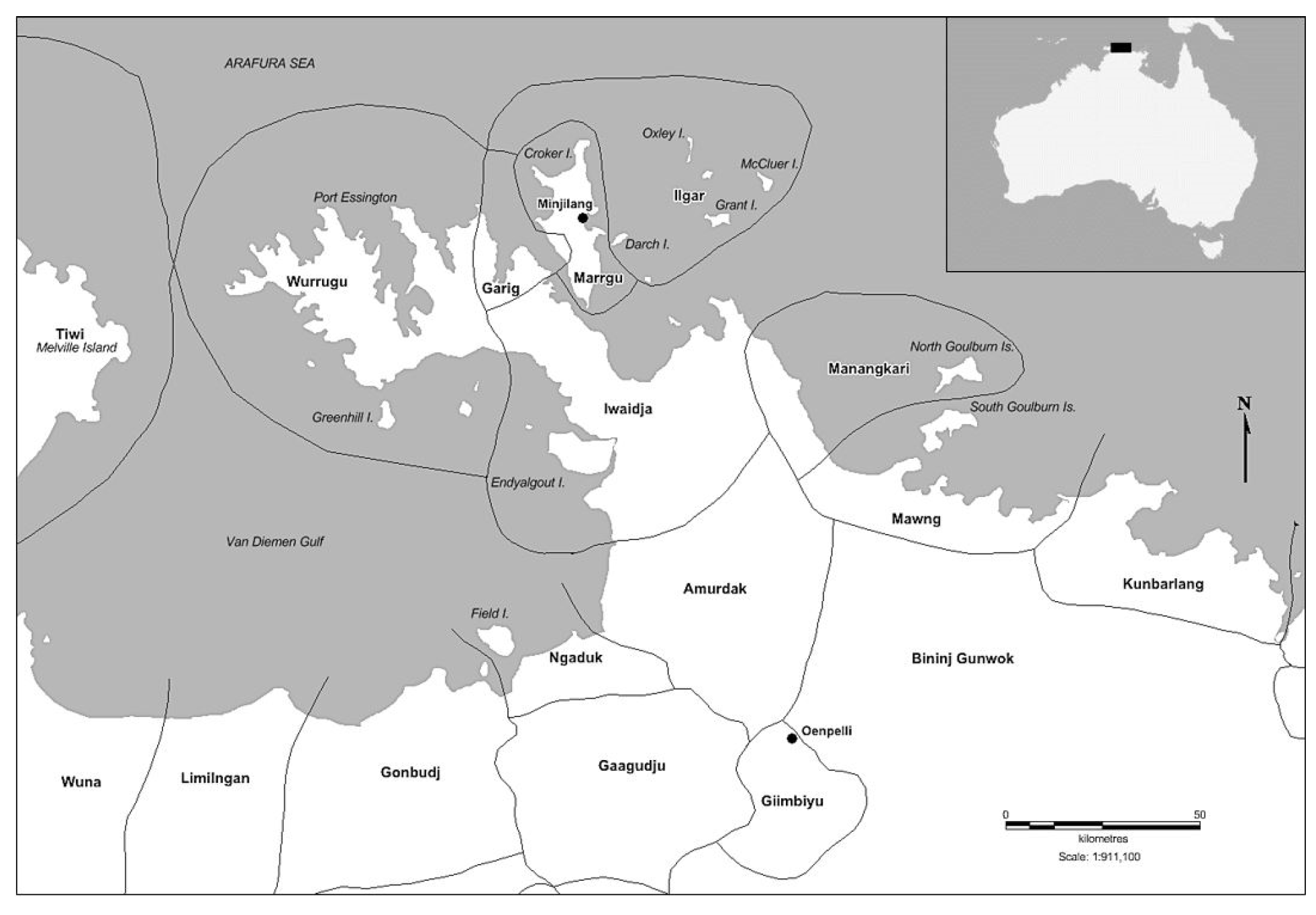

This paper will explore a remarkable intonational contour found in Iwaidja, a severely endangered Indigenous Australian language spoken in northwestern Arnhem Land, now mainly on Croker Island (cf. Figure 1). It will be based on data collected in the remote community of Minjilang (Croker Island, N.T.) using experimental elicitation methods as well as more traditional questionnaire-based investigations over the course of several years (2013–2019). It elaborates on preliminary results presented in Mailhammer and Caudal (2019) and will primarily be concerned with the semantics of this contour.

Figure 1.

Croker Island and Indigenous languages and their historical locations in northern Arnhem Land, from Mailhammer and Harvey (2018).

1.1. Linear Lenghtening Intonation at a Glance: Formal Properties

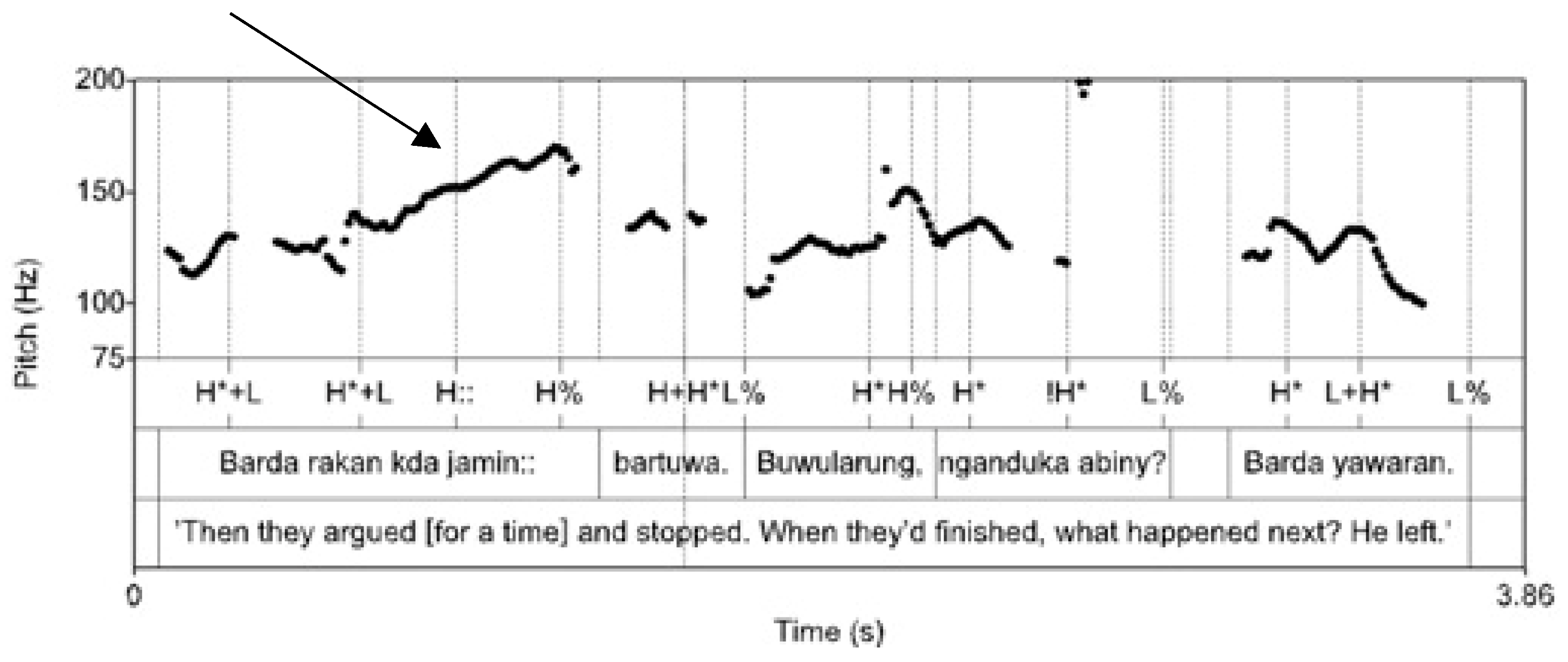

Many descriptions of Australian Indigenous languages mention a specific intonation as part of the tune inventory, characterised by a plateau in F0 finishing on a mid to high tone, plus additional lengthening of the last syllable nucleus in the intonational phrase, followed by a drop on the next intonation unit. Example (1) illustrates this phenomenon in Iwaidja, the language under scrutiny in this paper, and Figure 2 gives a graphic representation generated using Praat, cf. Boersma and Weenink (2021). In Iwaidja examples LLI is marked with a double colon “::” in interlinear glosses.1

| (1) | Barda r-aka-n | lda | jamin:: | bartuwa. |

| Then 3sg.m>3sgANT-argue-ANT | and | 3sg.RECP. | EndSequence |

Figure 2.

Linear lengthening intonation in Iwaidja, from Mailhammer and Caudal (2019) with added arrow pointing to the relevant section.

‘Then they argued for a long while, and (finally) stopped [lit. ‘that was it’].

Following Mailhammer and Caudal (2019), we will call it Linear Lengthening Intonation (LLI). LLIs are widely attested across Australian languages, especially northern Australian languages—cf. Birch (1999), Bishop (2002), Simard (2010, 2013), Ross (2011) and Fletcher (2014). Their formal properties appear reasonably clear, recurrent across all the Australian languages in which they have been documented so far, cf. Simard (2013, p. 67). Lengthening (noted in Figure 22 by the symbol H(::), lengthened high tone) and final high tone at the end of the intonational phrase (noted by H%, high boundary tone) are the two core criteria for identifying LLI in Iwaidja. Figure 2 demonstrates that, at least in this language, linear lengthening intonation need not show a plateau contour. Although the linear F0 progression can precede the last nucleus by a substantial amount of time, linear lengthening occurs on the last syllable of a word, which need not be the stressed vowel; see, e.g., jamin in Figure 2, a contrastive pronoun used in reciprocal constructions. The following intonational phrase can show a falling contour (as in Figure 2); a following intonational phrase can also be altogether missing or preceded by a pause of up to ten seconds. By and large, therefore, lengthening appears to demarcate the end of a prosodic unit, possibly an intonational phrase. Note that while we identified examples in our corpus showing not only lengthening of the verb’s final vowel, but also of an argument NP or a VP modifier, these are clearly marginal. It is unclear to us whether certain particle-like words or postverbal clitics could combine with LLI marking in Iwaidja, as some do in, e.g., Anindilyakwa, cf. Bednall (2020)—but this would be hardly surprising, as such particles are sometimes difficult to distinguish from clitics, and are known in Iwaidjan languages to be elements of the extended verb template (Singer 2006, pp. 73–74). However, some postverbal clitics/particles do seem to reject LLI marking in Iwaidja, in particular kirrk ‘completely’—we will come back to this later in the paper.

LLI, as shown in (1), formally and semantically contrasts with other prosodic lengthening, notably one conveying great spatial distance (we suffix the lengthening semi-colons with a D to distinguish this lengthening from LLI). The Iwaidja distal deictic baki, ‘over there’, has a lexicalised, mandatory lengthening attached to it (speakers rejected made-up examples without lengthening), approximating something like lexical tone (i.e., it contrasts with baki ‘tobacco’) (2).

| (2) | Baki::::D ! |

| There::::D | |

| ‘Over there, a long way away!’ |

Such lengthening is not associated with temporal properties, and cannot be followed by the kind of drop found with LLI. Bednall (2020) observes additional formal prosodic differences between ‘true’ LLI, and (possibly) distance-related prosodic marking in Anindilyakwa—thus, it can occur on the first syllable of a word, unlike LLI, which is always word final. For want of enough data points relating to, e.g., space-measuring lengthening in Iwaidja, we will leave this issue aside for future research, and focus instead on LLI, whose function is purely temporal-measuring.

1.2. Existing Analyses and the Semantics of Linear Lenghtening Intonation

In sharp contrast to its formal properties, the semantics of LLI has so far proved elusive (Sharpe 1972; Simard 2013). Existing analyses typically ascribe LLI an iconic status regardless of the language in which it was identified. For instance, Bishop (2002, p. 82) claims that it ‘dramatises’ the ongoing nature of the action’ or ‘the extent of some referent’—qua an ‘amount of a material substance’, or ‘extent of a geographical region’. However, from a theoretical semantic point of view, what this ‘dramatization’ function is really about is not very clear; several theoretical concepts come to mind—scalarity in the sense of e.g., Kennedy (2001), and/or some sort of expressive meaning, which could warrant for instance a multi-dimensional semantic approach (see, e.g., Potts 2005, 2007; Gutzmann 2015). Identifying the correct theoretical analysis and formal modelling for the semantics of LLI in Iwaidja will be of central importance to the present account.

It must be stressed that comparative facts alone are sufficient to suggest that the iconic view may not be warranted, at least not in the sense of an on-line, synchronically productive device. Thus, in Anindilyakwa, LLI is most commonly hosted by a special clitic =wa (glossed XTD ‘eXTendeD’ by J. Bednall in his work), possibly derived from adverbial ngawa (‘still’), cf. (3)–(4), Bednall (2020).

| (3) | nanga-luku-lukwa-mǝrrkaju-wa | d-adǝ-m-alǝka-langwiyu...wa |

| 3m/3f-rdp-tracks-follow-pst | 3f-f-inalp-foot-abl.prg…xtd | |

| yingǝ-lǝkarrki-lyǝmada | ||

| 3f-tracks-disappear-∅ | ||

| ‘he kept following her tracks until they disappeared’ [‘Search’ z47-8, Egmond (2012, p. 275)] | ||

Interestingly, ngawa itself can bear LLI as an isolated word:

| (4) | Engka | na-rndarrka. | Na-lawurrada |

| neut.other neut/neut-grab-∅ | neut-return-∅ | ||

| ebina-langwiya, | nga...wa | ||

| neut.that.same-abl.prg | still…xtd | ||

| ‘It [the she cat] grabbed another one [another kitten], then it brought [it] back, going along the same way (=all the way back)’. [Bujikeda, Egmond (2012, p. 220)] | |||

=wa can therefore be regarded as a morphological reflex of LLI—a fact which clearly demonstrates that at least in Anindilyakwa, LLI is not just an iconic intonational contour with a ‘transparent’ meaning; it involves an arbitrary form/meaning pairing—in this case, what seems to be a conventionalised construction, involving a specific adverbial in a specific syntactic position. In addition, there seems to be substantial formal variation in the inventory of LLI or LLI-like contours available in each given language—as was notably shown in, e.g., Bishop (2002), Bednall (2020). As indicated above, and in contrast to, e.g., Anindilyakwa and Bininj Gun-Wok, Iwaidja does not seem to licence word initial lengthening. If Bednall’s (2020) description of two distinct types of lengthening in Anindilyakwa is correct (i.e., if he is correct to assume semantic and phonological differences between word initial vs. word final lengthening, with respectively temporo-spatial/emphatic vs. purely temporal meanings), then LLI is just one out of several ‘dramatizing’ devices in this language. In this case, we are definitely dealing with two distinct grammaticalised prosodic markings with different form-meaning pairings. Consequently, if iconicity can be invoked, it can only be as a diachronic matter, or as an additional, non-necessary meaning. Synchronically, these constitute two distinct conventionalised form-meaning pairings.

1.3. Background on Iwaidja

Iwaidja is an under-described, severely endangered non-Pama-Nyungan language pertaining to the Iwaidjan language family (Mailhammer and Harvey 2018). Originally spoken in the Coburg Peninsula area of northwestern Arnhem Land, it is now one of several Australian Aboriginal languages spoken on Croker Island. Though until very recently, Iwaidja was the main language of the island, deaths of key speakers in the last 15 years and a general loss of speakers due to non-transmission and migration have adversely affected the speaker base. It is currently unknown if or to what degree Iwaidja is transmitted to children, and there are probably fewer than 50 proficient Iwaidja speakers currently living on Croker Island. These demographic circumstances preclude access to a large pool of speakers, and therefore render extremely difficult the use of quantitative methods in their standard form. Therefore, the type of experimental work we are reporting on in this paper is essentially of a qualitative nature (see Mailhammer and Harvey (2018, p. 332) for details on the documentary status, the level of analysis and the usage of Iwaidja).

Iwaidja can be described as a weakly polysynthetic language (Fortescue 2016), as its verb template is (i) holophrastic but (ii) does not exhibit productive noun-incorporation. Its verb template only comprises four positions, cf. Table 1: the first position is a typical northern Australian pronominal portmanteau exponent, combining person, gender and number information on the verb’s valency, plus some TAM information (TAM1), and optionally, deictic information (with a distal vs. proximal distinction). The verb stem occupies the second position, reduplication exponents optionally occupy the third, and another TAM exponent (TAM2) occupies the fourth and final position—with TAM1 and TAM2 forming a discontinuous single TAM morph, i.e., some manner of circumfixal morph (this is an instance of so-called distributed exponence; see Carroll (2016)).

Table 1.

The Iwaidja verb template.

Iwaidja possesses two realis/indicative past tense paradigms. The first of these is an aspectually underspecified anterior tense (ant), receiving imperfective readings with atelic utterances (except in inchoative, change-of-state contexts, of course), and perfective (or more rarely, perfect) readings with telic and other CoS utterances. The second is a general past imperfective viewpoint (ipfv), with clear pluractional properties as we will see (somewhat reminiscent of imperfective morphology in certain Slavic languages). Given this aspectual partial opposition between the two paradigms, it was highly desirable to control for viewpoint as a key condition of our experiments.

1.4. Our Research Question and Road-Map for the Present Paper

The goal we pursue in this paper is to determine the exact semantics of LLI in Iwaidja and what kind of theoretical and formal concepts should be used to account for its alleged ‘intensifying’ or ‘dramatizing’ functions.

The main contribution of the paper is to demonstrate that the semantics of LLI is broadly event-quantificational as well as temporally scalar. This is in a sense different from event scalarity (Kennedy 2012), for its scalar dimension is unrelated to event boundaries and changes-of-state measurement, and rather involves a contextually determined temporal duration scale—and a related standard of comparison. We will propose a formal treatment of this typologically unusual category3 at the semantics/pragmatics interface, reflecting on what we believe to be a kind of semantic/pragmatic complexity on a par with that of, e.g., tenses and temporal discourse connectives. We will specifically argue that it is at once a sentence-level marker, i.e., a VP-modifier constraining the aspectual type of VP-denoted event predicate, and a discourse connective-like item relating two distinct intonation units with respect to temporal ordering.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we elaborate on the experimental fieldwork we conducted to study LLI-marked event descriptions, using specially designed video clips to elicit naturalistic event descriptions, combined with targeted, questionnaire-based elicitation, conducted on this intonation contour in Iwaidja. As we will see, the methodology underlying our experiments rests on a classic two-component model of aspect (Smith 1991; Klein 1994), distinguishing between viewpoint aspect (essentially, functions denoted by inflectional verbal morphology, ranging over event predicates denoted by verbs) and event structure aspect (or so-called Aktionsart).

Section 3 discusses the results of our fieldwork; we will notably show that the behaviour of LLI in the data we collected is consistent with the view that it denotes an event predicate modifier—i.e., something akin to an aspectuo-temporal adverbial. In addition to this, we will also demonstrate that LLIs also behave like discourse-level aspectuo-temporal markers. They often associate with overt discourse connectives (e.g., the bartuwa discourse connective (‘and then/that’s it’)), reinforcing the inherent temporal ordering function of LLIs, and making explicit their interaction with discourse structural parameters. Indeed, LLIs constrain the establishment of discourse relations (Asher and Lascarides 2003); the rising pitch vs. low pitch intonation units involved in a LLI pattern such as in Figure 1 must be related by Narration, Result or, exceptionally, Elaboration.4 These facts reflect, we will argue, on the typologically complex and fine-grained grammar of event descriptions (especially with respect to event duration, closure and ordering) in Iwaidja, and in general, in Australian languages, cf. Caudal (2022b).

2. Materials and Methods: Experimental Elicitation of LLI-Marked Utterances in the Field

The data presented below were collected experimentally in the community of Minjilang (Croker Island, N.T., Australia, cf. Figure 1), between 2013 and 2018, either by Patrick Caudal and Rob Mailhammer, or by Rob Mailhammer alone, partly assisted by Bruce Birch. They are outcomes of a long-term collaborative project dedicated to the study of the TAM system of Iwaidja, which began with the creation of a dedicated experimental database, namely the Event Description Elicitation Database (EDED).

2.1. The Event Description Elicitation Database: Constitution and Features

The Event Description Elicitation Database (EDED) was originally devised to elicit naturalistic event descriptions in under-documented languages with complex tense-aspect systems, i.e., combining aspectually meaningful lexical verbs (i.e., endowed with Aktionsart meanings), and aspectually meaningful inflectional markers.

The EDED event type ontology can help elicit both simplex and complex event descriptions. Simplex event types comprise: (a) simple stative, positional stimuli (such as those expressed in English by the positional, stative meanings of sit (as in ‘be sitting’) or stand (as in ‘be standing’); (b) simple activities; (c) simple telic events (both achievements and accomplishments). Complex stimuli include: (a) iterated simplex events, (b) sequences of one or several simplex events, (c) temporal embedding of a simplex, telic event into a complex or simplex event and (d) sequences of distinct iterated simplex (=complex) events.

In addition to Aktionsart features, EDED targets the elicitation of aspectual viewpoint features in the sense of Smith (1991), in combination with all major Aktionsart classes, and including various aspectually coerced readings in the sense of de Swart (1998). Cases include (i) unfinished, imperfectively viewed accomplishment descriptions (e.g., ‘Rob was cutting the bread/the tree’), (ii) inchoative states and activities and (iii) non-culminating/avertive readings (‘X tried and failed to V/X nearly Ved’).

Perfective vs. imperfective viewpoint readings are elicited by means of the visual rendering in the clips of temporal ordering between events—namely strict succession for perfective viewpoint-inducing stimuli, vs. temporal overlap/partial ordering for imperfective viewpoint-inducing films. This corresponds to the now well-known discourse structural effects of aspectual classes of tenses: thus, within a Segmented Discourse Representation Theory (SDRT)-based discourse structural approach (Asher and Lascarides 2003) to context, temporal succession typically associates with the computation of Narration, Occasion, Continuation or Result rhetorical relations, whereas temporal overlap will typically lead to Background rhetorical relations; cf. e.g., Vet (1980), Molendijk (1983), Lascarides (1992), Asher et al. (2007) and Caudal (2012).

EDED was created over three years, in 2013–2014, by Patrick Caudal and Rob Mailhammer. Additional clips were created in 2016 by Patrick Caudal with the assistance of James Bednall. It currently consists of 250+ short video clips, arranged in different experimental protocols.5 Each of these protocols comprises between 34 and 83 video clips. The different protocols target the following phenomena:

- Protocol I: interactions between inflectional aspect/viewpoint and event structure

- Protocol II-IV: interactions between tense-aspect information and motion/posture (with sitting, standing, lying, squatting postures, plus iterative vs. eventive events being represented in the films)

- Protocol V: event structure, tense-aspect marking, event reduplication/habituality

- Protocol VI: a combination of all the above

2.2. Using EDED in the Field

In the field, we used EDED protocols with eleven participants, mostly in Minjilang (with one field trip in the community of Warruwi on South Goulburn Island). Nine of these participants were native speakers of Iwaidja (5 male, 4 female, between 40 and 75 years old). Seven completed the experiment in Iwaidja only; two participants also completed it in English; two participants were proficient speakers of Iwaidja who acquired the language in late childhood or adults (late bilinguals). These two participants completed the experiment in English only. All participants were shown a series of 34 video clips (List V, 2014); some were shown earlier, longer series I, II and III (see Appendix A). Our typical recording setup involved one to three informants, and at least two linguists. Informants were shown each of the films sequentially on a computer screen, and were then prompted to describe what happened in Iwaidja, using one of three past contexts:

- simple, non-iterated event description context (‘X did Y (once)’) (prompt: ‘what happened nanguj [‘yesterday’]/wularrud [‘a long time ago’]?’)

- iterated past event description (‘X did Y for a long time’) (prompt: ‘what did he/they keep doing till the sun went down nanguj [‘yesterday’]?’)

- past habit context (‘X used to do Y’) (prompt: ‘what did he/they keep on doing all the time wularrud [‘a long time ago’]?

Their answers were recorded using audio and video recording equipment, with up to two video recorders (front/back view); see Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Picture (a) shows a stimulus as seen by the informants, while picture (b) shows a typical set up (with from left to right: linguists Patrick Caudal and Bruce Birch, informant KM, linguist Rob Mailhammer, and informant AB; this photograph was taken on 11 July 2013 at Adjamarduku outstation, Croker Island).

This study and relevant protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of Western Sydney University (H10237), Chief Investigator Robert Mailhammer.

3. Results

Due to the limited number of participants (by laboratory standards)6, we were unable to construe our fieldwork experiment into a quantitative research project. We collected, transcribed and collected around 4000 utterances using EDED and complementary questionnaires bearing on a variety of TAM phenomena. However, only a fraction of these utterances bears LLI marking.7 The resulting corpus is evidently too limited to warrant the application of efficient quantitative methods—in contrast to other contributions to the present volume.8 LLI was identified perceptually and acoustically in terms of the pitch contour using the formal criteria in 1.1. In general, this was a straightforward process, as LLI is very salient. Both authors identified LLI and there was no disagreement.

Although the empirical generalizations we will propose here are based on solid, iterated attestations of certain phenomena or on grammaticality judgments, it is impossible to measure quantitatively what could be coined ‘semantic tendencies’ of LLI marking, and in general rank parameters constraining the interpretation of LLI, in a manner comparable to, e.g., Caudal and Bednall (this volume). Such a task will have to be deferred until substantial further investigations can be conducted in the field.

3.1. The Aspectual Profile of LLI: Event Structure Selectional Restrictions, and Distribution with Imperfective Contexts, Posture Serial Verbs Plus Reduplication

Our fieldwork using the EDED database was complemented by translation tasks from English targeting durative contexts (‘it lasted for a long time’); the questionnaires were specifically designed so as to cover most Aktionsart parameters (i.e., telicity/atelicity, dynamicity/stativity, durativity/punctuality, scalarity/non-scalarity). It eventually appeared that non-durative, punctual telic events tended not to associate with LLI. This was further confirmed by attempts at eliciting acceptability judgements on made-up Iwaidja punctual telic utterances bearing LLI marking. Several speakers (KM, CM, JC and RN) were adamant that prompt (5) was impossible (see (5)–(7)); some even questioned the very point of producing such forms.

| (5) | Linguist: “Would you be happy to say something like | *riwukban | |||

| 3sg.m>3sg.ant-give-ant | |||||

| arlirr::? | Or | karlu?’ | |||

| stick:: | NEG? | ||||

| JC: | ‘Arlarrarr’ | ||||

| NEG/nothing | |||||

| ‘No’ | (TAIM141124JCRNKMededIw_PC, RN: 01:13:13-40) | ||||

| (6) | [Another informant also reacting to prompt (5)] | ||

| RN: ‘Uh?? | *‘ri-wukba-n:: | (arlirr) Why would you want to say that?’ | |

| 3sg.m>3sg.ant-give-ant:: | (stick) | ||

| ‘he gave (the stick)’:: | (ibid.) | ||

| (7) | [Same informant as in (6), rejecting another prompt similar to (5)] | ||

| RN: ‘But you can’t say | *ri-wukba-n:: | ya-wara-n. | |

| 3sg3sg.m>3sg.ant-give-ant | 3sg.dist.ant-go-ant | ||

| No sense’ | (TAIM141124JCRNKMededIw, RN: 01:14:17-21) | ||

In contrast, LLI can associate with ‘durative’ telic event descriptions (accomplishments), cf. (8)–(9)—note that, while (8) does not clearly culminate, (9) clearly does; it even incorporates a maximal degree modifier (kirrk ‘completely/all’) which makes it clear that the maximal degree on the scale associated with the event was reached, and the entirety of the associated incremental theme (the clothing) was hung up. Similarly, in (10) the overt quantifier wardad (‘one’) makes it clear that a single tree is affected, and bartuwa indicates that it was thoroughly and successfully cut. Consequently, LLI cannot be described as semantically imposing a detelicising interpretation with verbs; rather, it appears to leave culmination as a matter of contextual, pragmatic inferences.9 The non-culmination reading of (8) is contextually determined, not enforced by LLI (though it undoubtedly helps in this example). We will return to non-culminating readings of LLI-marked verbs below.

| (8) | Iyi, | nganduka | a-bi-ny | mana? | Ri-ldalku-ny: |

| Yes, | pro.int | 3sg-say/do-ant | maybe | 3m.sg>3sg.ant-cut-ant | |

| ‘Yeah, what might he have been doing ? | He was cutting::’ | ||||

| (TAIM20130711aM-KM+AB, KM: 00:45:51.071–00:45:53.751) | |||||

| (9) | Ri-walkarti-ny:: | buldirrk:i:…ki | r-arndala-ng:: | ||

| 3m.sg>3sg.ant-put.up-ant | clothing | 3m.sg.>3sg.ant-put.to.dry.ant | |||

| kirrk. | Ka-walkarti-ny | yurrngud | kirrk, | bartuwa. | |

| ALL | 3f.sg.ant-put.up-ant | high | ALL | finished. | |

| ‘He hung all the clothing up:: he put it to dry (in the sun):: completely. She hung it all up, finished’ | |||||

| (TAIM20130711aM-KM+AB, KM: 00:46:47.318–00:46:52.558) | |||||

| (10) | ri-ldalku-ny:: | wardad | ri-ldalku-ny:: | bartuwa |

| 3m.sg>3sg.ant-cut-ant | one | 3m.sg>3sg.ant-cut-ant | finished | |

| “He cut it (long time). One he cut (long time) and that was it’ | ||||

| (TAIM141126ILededIw, IL:00:51:23.800–00:51:27.525) | ||||

This suggests that LLI imposes aspectuo-temporal restrictions on the event predicate conveyed by the verbs. More specifically, it seems to select a durative event predicate, whether telic or atomic, and clearly rejects what can be characterised as atomic telic event predicates, cf. Dowty (1986), Caudal (1999)—i.e., as non-scalar punctual event predicates (achievement verbs).10

It does not come as a surprise, therefore, that LLI is repeatedly attested in our corpus in combination with markers which suggests a protracted, durative event description. In particular, LLI often pairs up with posture-verb based serial verb constructions (SVCs), cf. (11). As was shown in, e.g., Caudal and Mailhammer (2017), posture-verb SVCs in Iwaidja contribute an aspectual function whose semantics can be likened to that of a pluractional/iterative/durative aspectual verb ‘keep on V-ing’ in English. In addition to durative ‘keep on’ SVCs, LLI can combine with reduplication, either morphological (12) or lexical (13). LLI can also associate with imperfective morphology on the verb, cf. (13)–(15); and strikingly enough, its semantic effect is then often closer to a Slavic-style imperfective affix, rather than to an average, e.g., Romance, imperfective viewpoint tense, as it tends then to have pluractional effect, cf. e.g., (13), which spells out through full, lexical reduplication, the pluractional reading of the imperfective form ka-ldalku-ngung (‘she was cutting it, cutting it’)11. Additionally, (14) and (15) are also remarkable examples in that they show a pluractional, atelic reading of a verb, followed by an expression lexicalizing a successful termination—illustrating a common tendency among Australian languages to treat culmination as a non-lexical issue (again, cf. Caudal (2022b) for an extended discussion of this issue).

| (11) | a-ringan | Ø-birda-niny:: | ya-wara-n |

| 3sg.ipfv-stand-ipfv | 3sg.ant-sing-ant | 3sg.dist.ant-go-ant | |

| ‘He sang for a long while [lit. ‘was standing singing::’ ] then he stopped [lit. ‘left’]’ | |||

| (TAIM141124JCRNKMededIw_PC.eaf, RN:00:06.20-22). | |||

| (12) | a-ringan | Ø-birdadbirda-niny:: |

| 3sg.ipfv-stand-ipfv | 3sg.ant-red.sing-ant | |

| ‘He sang for a long while [lit. ‘was standing singing::’] | ||

| (TAIM20130717aW-WM+MM-tasc, MM: 00:56:11.380–00:56:12.860). | ||

| (13) | ka-ldalku-ngung:: | k-udba-ng | ka-ldalku-ny |

| 3f.sg>3sg.ipfv-cut-ipfv:: | 3f.sg.ant-put.down/leave-ant | 3f.sg.ant-cut-ant | |

| ka-ldalku-ny | ka-ldalku-ny | ||

| 3f.sg.ant-cut-ant | 3f.sg.ant-cut-ant | ||

| ‘she was cutting and put it down and cut, cut, cut, cut… [and then finished]’ | |||

| (TAIM141126ILededIw, IL: 00:11:16.000–00:11:20.796) | |||

| (14) | ri-ldalku-ngung | artbung:: | bartuwa |

| 3m.sg>3sg.ipfv-cut-ipfv | again:: | finished | |

| ‘He kept on cutting it again and again… then he finished’. | |||

| (TAIM141126ILededIw, IL 00:10:45.571–00:10:48.849) | |||

| (15) | ri-muni-ny:: | barda | wurlawu |

| 3m.sg>3sg.ant-pound-ant | then | ready | |

| ‘He kept pounding it [the food] and after a time it was ready.’ | |||

| (TAIM20130721aM-IL+ISL, IL 00:58:13) | |||

Equally unsurprisingly, LLI can freely combine with all types of reduplicated lexically telic verbs, as they describe durative, pluractional events. Examples (16)–(20) were elicited in an explicitly iterative context (‘what did he do till sunset?’). Given such a context, both with and without an overt iterative expression (SVC, duration adverbial or expression), LLI is always warranted. Both SVCs and reduplication are commonly associated with LLI in such contexts; their presence reinforces the markedness of the duration expressed, i.e., contributes to further stressing what seems to be an expressive dimension of LLI—which, in our opinion, exactly corresponds to its so-called ‘dramatizing function’, or so-called ‘iconicity’ in previous work.12

| (16) | ri-ldalku-ny:: | ri-ldalku-ngung | artbung:: | bartuwa |

| 3m.sg>3sg.ant-cut-ant:: | 3s.sg>3sg.ipfv-cut-ipfv | again:: | finished | |

| ‘he cut and cut and cut, he kept cutting and then was finished’ | ||||

| (TAIM141126ILededIw-PC, IL: 00:10:42.469–00:10:48.849) | ||||

| (17) | nanguj | a-ringan:: | Ø-kartbirru-ny:: |

| yesterday | 3sg.ipfv.stand.ipfv | 3sg.ant-throw-ant | |

| ‘Yesterday, he kept on throwing (the stone)’ | |||

| (TAIM141124JCRNKMededIw_PC, JC: 00:46:14.982–00:46:20.000) | |||

| (18) | a-ri-ng | r-arnaka-ng | jurra:: |

| 3sg.ant.stand-ant | 3m.sg>3sg.ant-stab-ant | paper (bag) | |

| ya-wurryi-ngan | manyij | ||

| 3sg.dist.ipfv-go.into.water-ipfv | sun | ||

| ‘He kept on stabbing the paper (bag) as the sun was setting’ | |||

| (TAIM141124JCRNKMededIw_PC, JC: 00:28:40-42) | |||

| (19) | ri-majbungku-ng:: | k-artbiru-ny | [wardyad] |

| 3sg.m>3sg.ipfv-lift.hold.up-ipfv::: | 3sg.ant-fall-ant | [stone] | |

| [context: slow motion of throwing a stone] | |||

| ‘He was lifting up/holding up [the stone] (then) it fell.’ | |||

| (TAIM141124JCRNKMededIw_PC, RM: 00:45:03-04) | |||

| (20) | nanguj | aringan | ri-majbungkungku-ng:: |

| yesterday | 3sg.ipfv.stand.ipfv | 3sg.ipfv-lift.red-ipfv | |

| ‘yesterday, he kept on lifting [that stone]’ | |||

| (TAIM141124JCRNKMededIw_PC, JC: 00:51:30.058-32.000) | |||

Both ANT and IPFV inflectional marking appear in our data (the latter with a durative, single-event reading (19) or a durative, pluractional reading, as in (16), (18) and (20)—where the presence of reduplication morphology enhances the pluractional reading). Sequence (21) gives two formally different utterances describing the same iterated event, with speaker RN reformulating in the imperfective of a previous utterance in the anterior. These two descriptions are therefore truth-conditionally equivalent; this demonstrates the pluractional, durative dimension of the semantics of the Iwaidja imperfective.

| (21) | JC: | nanguj | a-ri-ngan:: | Ø-kartbirruny:: |

| yesterday | 3sg.ipfv-stand-ipfv | 3sg.ant-fall-ant:: | ||

| ya-wurryildi-ny | manyij | |||

| 3sg.dist.ant-go.down-ant | sun | |||

| ‘Yesterday he kept on throwing [the stone] until the sun went down’ | ||||

| RN: | Ø-kartbirruku-ng | |||

| 3sg.ipfv-fall.red-ipfv | ||||

| (TAIM141124JCRNKMededIw_PC 00:46:14-27) | ||||

It is also worth observing the reformulation of (18) given in (22), where another speaker immediately describes the same event, but using a different form; the two utterances are given as nearly truth-conditionally equivalent. Starting from the LLI structure in (18), speaker RN paraphrases it in (22) as a markedly emphatic combination of (i) morphological reduplication (rarnanarkang), (ii) lexical reduplication (rarnanarkang jurra x 2), (iii) plus temporal ordering (kayrrik ‘and then’) and event-bounding (burruli ‘good/done’) expressions—the latter conveying the temporal and discursive function of the low tone, second intonation unit ‘closing off’ the phonologically complex LLI structure in (18). It is likely that this overtly emphatic reformulation originates in the already substantially emphatic nature of (18) (due to the combination of LLI with an SVC construction).13 By event bounding, we here refer to event boundedness, i.e., the fact that context or a linguistic expression specifying a limited duration—here LLI combined with an event-bounding expression or prosodic unit—can ascribe a final point on the temporal trace of event; see, e.g., Corre (2022), Bogaards (2022), this issue, for a similar concept.

| (22) | r-arnanaka-ng | jurra | r-arnaka-ng | jurra | |

| 3m.sg>3sg.ant-stab.again -ant | paper | 3m.sg>3sg.ant-stab-ant | paper | ||

| r-arnanaka-ng | jurra | kayirrk | kuburruburr | burruli | |

| 3m.sg>3sg.ant-stab-ant | paper | and.then | early.morning | good [done] | |

| ‘He kept stabbing though the paper, then in the early morning it was done.’ | |||||

| (TAIM141124JCRNKMededIw_PC, RN: 00:30:48–00:31:00) | |||||

It seems in fact that combining LLI with reduplication, posture SVCs and imperfective qua pluractionality bears the hallmark of marked durativity in general: it further emphasises their duration. In other words, we believe that the so-called ‘dramatizing’ function described in earlier works can be captured by likening LLI to a marked duration modifier, i.e., something akin to ‘for a long time’ (possibly, ‘for a really long time’), with ‘long’ constituting a subjective evaluation. In the discussion below, we will spell out, the theoretical and formal consequences of such a descriptive move.

Examples (21)–(23) illustrate particularly emphatic uses of LLI, in that they combine LLI with a posture SVC, and/or morphological or lexical reduplication. This extreme information redundancy ascribes (23) a four-fold, extremely emphatic durative-iterative reading.

| (23) | A-rin-gan | r-ahardalkbikbi-ny:: |

| 3sg.ipfv-stand-ipfv | 3sg.ant-jump.red-ant | |

| ‘He stood there jumping (repeatedly)’ | ||

| r-ahardalkbikbi-ny | a-ri-ngan:: | |

| 3sg.ant-red.jump-ant | 3sg.ipfv-stand-ipfv | |

| ‘He stood there jumping (repeatedly)’ | ||

| Bartuwa. | Ri-wularru-ng | |

| EndSequence | 3m.sg>3sg.ant-finish-ant | |

| ‘That was it. | It finished.’ | |

| (TAIM20130711aM-KM+AB.eaf, KM: 00:55:58.000–00:56:03.305) | ||

3.1.1. LLI and Aspectually Coerced Readings of Atomic Telic Verbs

Interestingly, it turned out that several speakers who had rejected some combinations of LLI with atomic telic verbs accepted them with special, marked readings. These uses seem to correspond to cases of aspectual coercion.

First and foremost, we should mention avertive readings (cf. Kuteva 1998; Kuteva et al. 2019) of LLI—where avertive designates a grammatical category covering a wide range of non-culminating meanings. Although the realis past anterior tense (ANT) is used in (24), the result normally associated with the relevant verb is not achieved. Furthermore, (24) closely parallels (25), which has no LLI marking, but bears a modal inflection specifying the ‘thwarted’ intention underlying the past realis verb (indeed, the FUT inflection often has volitional or hortative meanings in Iwaidja). We take such examples to be ‘non-culminating’ in a broad sense: although the target terminus point is reached, the teleologically predicted or desired result state does not come to hold; hence, an incomplete culmination (see (Caudal 2022a) for an extensive discussion of avertivity and non-culminating telic utterances in the context of Australian languages). Additionally, (26) further illustrates avertivity in connection with LLI, this time with a ‘keep on’ construction (waran (V) ‘he went on (V)’), followed by karlu (NEG): the intended goal of the iterative volitional construction with ‘go’ is thwarted, and the LLI marking contributes to this avertive reading.14

| (24) | R-urlukba-n:: | w-ardajb-ung |

| 3m.sg>3sg.ant-step.on-ant:: | 3sg.ant-couldn’t.break it-ant | |

| ‘He repeatedly tried (=tried hard) to break it with his foot but failed.’ | ||

| (25) | R-urlukba-n, | bana-rnukbun. |

| 3m.sg>3sg.ant-step.on-ant | 3sg.fut-break-fut | |

| ‘He stepped on it trying to break it.’ | ||

| (TAIM20130711aM-KM+AB, KM: 00:51:54.348–00:51:55.468) | ||

| (26) | W-ara-n:: | karlu | marukurnaj | ri-widari-ny. |

| 3sg.ant-go.on-ant | neg | pro.indef | 3m.sg>3sg.ant-prevent-ant | |

| ‘He went on for a while but nothing. Something prevented him from finishing.’ | ||||

| (TAIM20130721aM-IL+ISL, ISL: 00:49:34) | ||||

Apart from avertive readings, one could mention a range of cases in which LLI operates at an event’s macro-structural level, i.e., at the articulation between sub-events (see (Caudal 2005) for a discussion). Thus, (27) seems to illustrate a situation where LLI bears on the preparatory stage presupposed by the ‘come’ verb—it indicates that said preparatory stage was protracted.

| (27) | bingk-ung | kani:: | bartuwa |

| 3sg.ant.come-ant | here-LLI | EndSequence. | |

| ‘he came here slowly and then he was there’ | |||

| (Am_20160609_CMDC_IwAmld, CM:3:04) | |||

Additionally, (28)–(29) illustrate a coerced reading, in which a markedly long interval separates the event’s culmination/terminus from its normally expected result state. This interval introduces a temporal hiatus between an event’s inner stage and its result stage. This ‘hiatus’ effect is, to the best of our knowledge, a completely new type of aspectual coercion that has not been documented so far.

| (28) | ri-wu-ng :: | Ø-kartbuni-ny | |

| 3sg.m>3sg.ant-hit,kill-ant | 3sg.ant-fall-ant | ||

| ‘he hit/killed 3sg. After a while, 3sg. fell’ | |||

| (Am_20160608_CMDC_LLI, CM: 1:01) | |||

| (29) | ri-wunbu-ng:: | Ø-kartbuni-ny |

| 3sg.m>3sg.ant-hit.red-ant | 3sg.ant-fall-ant | |

| ‘he hit 3sg several times [at least twice] and then he fell’ | ||

| (Am_20160608_CMDC_LLI, CM:1:00) | ||

3.1.2. Combination with Degree Verbs and Impact on Nominal Quantification

Although we repeatedly tried to elicit LLI marking on scalar verbs, assuming the combination could convey some kind of high degree, or marked degree reading, or degree modulation in relation to some incremental theme argument or subject argument, we have systematically failed to find empirical support for the idea that LLI could interact with other measurable dimensions in the semantics of Iwaidja verbs; it seems thoroughly restricted to temporal duration. For example, we had absolutely no success in eliciting degree clitic/particle kirrk (‘completely’) with LLI. While kirrk can mark the post-lengthening intonation drop, conveying the culmination and closing of a protracted event, as in (9), it cannot be lengthened itself.

Speakers rejected all our attempts at construing such ‘high degree’ readings with both telic and atelic scalar verbs (i.e., with both open and closed scale verbs, see Kennedy and McNally (2005)). LLI cannot convey a high quantity of any argument either, given a scalar or telic verb. This suggests that if LLI associates with some sort of scalar meaning, its scalar meaning cannot map onto an event structure or argument referent-structure, as it cannot interact with incrementality, or argument structure (including with plural arguments) to mark a high degree. LLI is absolutely not about incrementality (nor any kind of event participant structure) or even culmination—it is telicity-neutral, as we have shown above—but about temporal duration.

Therefore, LLI seems to only relate some utterance to a contextually determined standard of duration—probably on the basis of world-knowledge and specific inferences made in a given context. This does not mean that such readings are impossible for LLI in other languages; however, claims made concerning the interaction of LLI with nominal semantics in other languages (as in, e.g., Bishop 2002) is not consistent with our data from Iwaidja.

4. Theoretical Discussion and Formal Analysis of Our Results

Let us now turn to the theoretical assessment and formal modelling of our results. Three salient generalizations uncovered during our field experiments need to be accounted for:

- LLI expresses subjectively marked durativity.

- LLI does not seem to relate its evaluative dimension to an event’s development per se, nor through an event’s degree scale, nor through incrementality nor the internal structure of the denotation of some argument.

- LLI normally rejects atomic telic utterances, but when combined with one, it can give rise to various coerced readings. In addition to this, it can (but need not) have non-culminating/non-resultative interpretative effects.

We will try to address these three different properties within a theoretical and formal model of LLI in the remainder of this paper.

4.1. A Temporal Scalar Meaning

It is obvious from the above generalizations that the semantics of LLI is similar to that of an event description modifier—i.e., some sort of aspectuo-temporal adverbial. As was proposed in Mailhammer and Caudal (2019), we will ascribe a tentative type ⟨⟨e,t⟩,⟨e,t⟩⟩ to its denotation. To be more specific, LLI seems (i) to be restricted to durative events, i.e., to events with a durative run-trace, and (ii) to convey a relative temporal comparison (in the sense of Kennedy 2001). LLI roughly expresses that the event at stake has a duration exceeding what is normally associated with the relevant event predicate—i.e., what we might want to call a temporal duration standard of comparison.

The idea that event predicates are associated with ‘typical duration’ is not novel, and has been elaborated upon, and even formalised, in past works, including, e.g., Wyngaerd (2001), Tatevosov (2008) and Gyarmathy (2015), among others; see also de Swart et al. (2022) in this issue, for a detailed crosslinguistic analysis of other durative expressions. Tatevosov (2008) thus proposed to formalise the notion of typical duration (TD), as in (30), where |τ (e)| notes the duration of the temporal trace of event e. Note that we are assuming TD to be contextually evaluated with respect to the speaker’s current beliefs and knowledge base; it is therefore a subjective and contextual standard of comparison—not an intersubjective, immutable standard. Tatevosov’s definition being extensional, this might prove problematic—but we will leave the issue of a better definition of TD aside for want of space to address it.15

| (30) | TD(P) = mean{n | ∃e[P(e) ∧ |τ(e)| = n]} |

We will assume that LLI is associated with a durative zero morph in Iwaidja (morpho-phonologically realised by particle/clitic = wa in Anindilyakwa), effectively an empty clitic attaching to the final syllable of the verb, and (i) causing the linear lengthening of said syllable and (ii) denoting a second order predicate over ‘long duration event’ predicate Lgdur.

Below, we formalise the semantics of Lgdur within Asher’s (2011) Type Composition Logic (TCL), as this framework makes it possible to state aspectuo-temporal constraints on event types in a straightforward way. Capitalizing on the ontological type hierarchy (i.e., sortal hierarchy) underpinning TCL, we will define non_atomic as the super type encompassing all event types except atomic telic events. π is a semantic stack argument ascribed to all predicative types in TCL; all type restrictions borne by a given function are stored in π and must be met as the relevant semantic derivation progresses. When they are met, during, e.g., the existential closure of some argument, the relevant restriction is pulled from the stack—or else, if they cannot be met during the relevant functional application, a type mismatch arises. π* ARG1P:non_atomic indicates that P’s first argument (its event variable e) must be a non-atomic event type, so that when P is bound and the tense operator binds e, if P is an atomic event predicate, then a type mismatch will arise. (Unless coercion bridging functions can apply and save the semantic derivation day—see below).

To put it in a nutshell, (31) indicates (a) that the predicate at stake must be durative (i.e., it must have a non-atomic run-trace) and (b) that the duration of P-events in the context must exceed the typical duration associated with P; furthermore, (31) also states that LLI requires a past temporal anchoring—indeed, it seems restricted to narrative contexts.16

| (31) | ⟦Lgdur⟧ = λP.λe.[P(e)(π* ARG1P:non_atomic)∧|τ(e)| ⪰TD(P) ∧τ(e)<n] |

Through (31), we are proposing a clearly productive, compositional semantic contribution for LLI, which sets this phenomenon apart from other prosodic markers studied so far with respect to their interpretative effects—see, e.g., Portes and Beyssade (2015), who argue against compositional analyses of other prosodic markers in French.

It should be noted that (31) is both similar to, and different from, the denotation of subjectively marked, long duration adverbials such as for a long time in English, or in any language possessing comparable markers. Existing formal accounts of such duration adverbials should, of course, be discussed to make the analysis proposed in (31) more precise in many respects—notably for habitual/generic or iterative readings; indeed, LLI-marked utterances frequently combine with morphological reduplication, to convey such meanings—see, e.g., (24) above—and even habitual meanings. Providing an account of such iterative and habitual meanings falls outside the scope of the current paper,17 but one could of course capitalise on insights offered by existing formal semantic works on unrelated languages focusing on durational phrases, from Geenhoven (2003), Boneh and Doron (2008) to, e.g., Landman and Rothstein (2012a, 2012b). Note that the last analysis allows for duration adverbials to combine with accomplishments under certain circumstances only, and that in general, for phrases can be problematic with most telic verbs. If our fieldwork observations are correct, LLI in Iwaidja differs from for adverbials in that it seems to allow for a wide range of telic verbs—though mostly accomplishments—without giving rise to iterated or habitual readings. However, our description is certainly in need of further data collection and experimental validation in the field with respect to habitual and iterative readings, so we should certainly leave a more precise discussion of such issues to future research. This being said, one important semantic difference between LLI and for adverbials is already fairly clearly established: if the lengthening component of LLI is followed by a tune-dropping IU, then the overall meaning is more complex than a mere for duration phrase. We will return to this further down.

4.2. Accounting for ‘Marked’ Readings with Atomic Telic Verbs

As we have seen above, the contribution of Lgdur(P) is essentially that whatever event e predicate P describes in the current context, it must be a non-atomic telic event variable, and that the duration of τ(e), the run-trace of e, must exceed that of some ‘mean’ P-event (e’). However, what if our LLI marker bears on an atomic telic verb?

Then two situations can hold: either a ‘bridging function’ (a semantic adaptor, metaphorically speaking) can intervene between Lgdur and P, so that an otherwise unwarranted functional application can be salvaged, or no such bridging function can be used, and the relevant combination is ill-formed.

Following a strategy developed in Caudal (2020), we will define such ‘bridging functions’ as lexically conventionalised meaning extensions attached to lexical verbs, or to verb classes at best. Asher (2011) introduced bridging functions to account for what is generally analysed as cases of aspectual coercion (de Swart 1998). Let us consider (27) again (here repeated as (32)).

| (32) | Ø-bingk-ung | kani:: | bartuwa |

| 3sg.ant.come-ant | here-lli | EndSequence. | |

| ‘he came here slowly and then he was there’ | |||

| (Am_20160609_CMDC_IwAmld, CM: 3:04) | |||

Setting aside the problem of how Ø-bingk-ung kani should be analysed at the syntax/semantics interface and assuming that it can be seen as contributing an event predicate akin to come in English, then it normally conveys an atomic event description, cf. (33):18

| (33) | ⟦come’⟧ = λe.λx.come’(e,x,π*ARG1come:atomic) |

The application of Lgdur to the denotation of come’ thus yields a type mismatch (non_atomic ≠ atomic). Following a proposal made in Asher (2011, p. 220), we will here use an aspectual coercion19 mechanism developed within the TCL framework in order to explain how such mismatches are overcome. Technically, if a function a of type α requires as one of its arguments b a meaning of type β but is instead combined with an argument c with some inappropriate type γ, then TCL will look for some context-dependent bridging function , capable of “accommodating” a type γ meaning into a type β meaning—i.e., takes an argument of type γ, and yields a meaning of type β. One can then apply a to the result of the application of to c. That is: *a:α [c:γ] triggers an attempt at deriving instead a:α ((c:γ)), with (c:γ) yielding an a-appropriate meaning c’:β.

The context-sensitivity of is rendered by introducing a polymorphic type (Asher 2011, p. 219) event function in its logical form, i.e., an underspecified event predicate noted φϵ (am, ... a1), where ϵ (am, ..., a1) indicates an underspecified semantic type ϵ, whose interpretation depends on the typing of its arguments am, ..., a1. To give an example, consider the interpretation of John finished a cigarette. The denotation f of finish must be applied to that of John and that of the cigarette. However, given that f requires an event predicate type as its object argument, the semantic type of f does not qualify and a bridging function finish must intervene. It should accommodate f by incorporating an underspecified event predicate function φϵ (am, ... a1). Contextual as well as lexical/real-world knowledge about the interrelation between the argument types of φϵ will make it possible to infer that a smoking event predicate is here involved: given a human agent type and a cigarette type appearing respectively as the agent referent and object referent types for φϵ in the current context, then the latter will be interpreted as having a meaning akin to the denotation of ‘smoke’, as human agents typically smoke cigarettes. See Asher (2011, pp. 226–36) for further details, as well as Caudal et al. (2012) for several comparable instances of TCL bridging-function based analyses in another Australian language.

Coming back to the analysis of (32), we will posit a bridging function 1 capable of overcoming the aforementioned type mismatch, by having the ability to extend the denotation of Ø-bingk-ung (‘he came’) in (27/32) with a ‘protracted preparatory stage’ component of meaning. We are giving in (34) an implementation of 1, such that its application to the denotation of Ø-bingk-ung results in a logical form endowed with a dual (rather than single) event structure, combining the coming event proper (e), existentially bound, with a non-atomic, unbound preparatory event λ-variable e’; τ(e’) < °τ(e) notes a left-abut temporal relationship between the runtraces of events e’ and e. The application satisfies π’s initial selectional restriction in the latter logical form (namely π*ARG1come:atomic); as the coming event e is existentially bound in 1, the corresponding selectional restriction is retrieved from π. The application of (34) to (33) is given in (34′); it makes the non-atomic e’ variable the main event variable remaining to be bound for the resulting logical form, so that (32) can be straightforwardly applied to its result, as the latter satisfies Lgdur’s own selectional restriction in (31) (i.e., π* ARG1P:non_atomic).

| (34) | 1 = λQλe’λxλπ.∃e[Q(e:atomic,x,π) ∧ ϕϵ (non_atomic, type(Q), type(x)) (e’,x,π, π*ARG1ϕ: non_atomic) ∧ agent(x,e‘) ∧ τ(e’) < °τ(e)]20 |

| (34‘) | a. | λQλe’λxλπ.∃e[Q(e:atomic,x,π) ∧ ϕϵ (non_atomic, type(Q), type(x)) (e’,x,π, π*ARG1ϕ: non_atomic) ∧ agent(x,e‘) ∧ τ(e’) < °τ(e)]( λe.λx.come’(e,x,π*ARG1come:atomic)) |

| b | ↝λe’λxλπ.∃e[come’(e:atomic,x,π) ∧ ϕϵ (non_atomic, type(Q), type(x)) (e’,x, π*ARG1ϕ: non_atomic) ∧ agent(x,e‘) ∧ τ(e’) < °τ(e)] |

Furthermore, in (34), ϕϵ(non_atomic, type(Q), type(x)) indicates that ϕϵ is an underspecified, contextually determined (preparatory stage) event predicate of non_atomic (i.e., durative) type, whose sortal type (i.e., lexical event type) can be inferred on the basis of the type of predicate Q and the type of its external argument x. The precise semantic nature of ϕϵ can be contextually determined using a TCL Glue Logic rule (36),21 following the standard TCL rule format given in (35) (cf. Asher 2011, pp. 227–28). In the absence of satisfying types in the logical form of an utterance, (36) cannot apply, and ϕϵ remains undefined; we will argue that this results in a degraded acceptability for the coerced reading.

| (35) | (e⊑e ∧ a⊑a) > ϵ (e, a) = P(e, a) | (with e event type, a object referent type) |

| (36) | (e⊑come ∧ a⊑animate) > ϵ (e, a) = directed_motion(e, a) |

Similar bridging functions can be formulated for all the other coerced interpretations identified in Section 3.1; however, for want of space, we cannot spell them out here.

4.3. On the Temporal Ordering, Discourse-Structural Effect of LLI

In addition to its sentence-level, compositional semantic contributions, it appears that LLI is frequently endowed with a discourse-structural function. In particular, it predominantly appears in sequence-of-event contexts, and can certainly mark event ordering (although this is not necessarily the case). This is quite obvious in its very frequent association with an ‘event bounding’ expression on its right—qua a post lengthening ‘closing off’ expression, cf. e.g., bartuwa ‘that’s it/finished’, as in e.g., (1), (23) and (32).

This might seem paradoxical given the durative and frequently imperfective aspectual semantics of LLI-marked verbs. However, as we have seen above, the Iwaidja past imperfective tense often appears to have a pluractional semantics in such contexts (cf. e.g., (16)), rather than a bona fide imperfective viewpoint content in the style of, e.g., Romance past imperfectives. After all, imperfectivity does not warrant event overlap; it can be associated with sequences of events—as is shown by the existence of, e.g., ‘narrative’ uses of various kinds of imperfective tenses, and in general by ‘temporal shifts’ one can apply to imperfective events as well. See, e.g., Caudal (2022c) for a detailed discussion of such issues in the light of a formal theory of discourse structure.

Following the latter reference, and coming back to a question raised in §4.1, we will propose that LLI has the ability to convey constraints on possible rhetorical relations attaching whatever expression will appear on the right-hand side of the LLI tune, in its ‘drop’ component. LLI should in a sense be viewed as coming in two brands: a single intonation-unit-based prosodic marker without any drop component (and lacking an event-bounding/temporal ordering function) as in (18), and a double intonation-unit based prosodic marker, with an event bounding function. In the latter prosodic construction, the first position corresponds to the discourse referent attached to the LLI-marked VP, and the second to the ‘event bounding’ expression attached to the tune-dropping intonation unit (cf., e.g., bartuwa in (1)/(23)/(32)); temporally speaking, the contribution of the second elements of such structure can be likened to a temporal discourse clitic of the ‘now/then’ type, familiar from several works dedicated to Australian languages—see, e.g., Ritz et al. (2012), Ritz and Schultze-Berndt (2015) and Browne (2020).

Although we will not propose a detailed formal implementation of the discourse structural function of the event-bounding, event-ordering type of LLIs22 here, we will put forth some analytical, formal suggestions. If we assume a SDRT-style approach of discourse structure (Asher and Lascarides 2003), with the additional technical twist that temporal-ordering expressions can convey constraints on discourse relations (as proposed in Caudal (2022c)), and that discourse relations can be incorporated in a compositional semantics, then we can formulate the two following very coarse-grained, tentative definitions for the discourse structural semantics of the two intonational components of LLI constructions (high contour + plateau intonation unit in (37)), with a durative function meaning, vs. dropping tune intonation unit, with an event ordering function meaning in (38)).

| (37) | DurativeLLI =∃β(β:[…V…]∧Lgdur(V) ∧ ?(α, β) ∧α=?) |

| (38) | BoundingLLI =∃β(Sequence_of_Event_Rel(α, β) ∧ α:[…V…]∧Lgdur(V) ∧α=?]) |

The definition in (37) merely incorporates into an undefined discourse structural function denotation, the Lgdur non-atomic event, durative scalar function already identified above, and applying to the head verbal predicate V in the DRS dominated by β. Indeed, ?(α, β, γ) indicates that the durative LLI-marked discourse referent β can attach to the discourse context at segment α, via whichever discourse relation type will be compatible with its semantic profile (we are leaving this as an open question for future investigations).

The definition in (38) stipulates that the meaning of the ‘dropping tune’ in LLI constructions is to introduce a novel discourse referent β, by attaching it to some segment α previously introduced by the DurativeLLI function (37) (cf. condition α:[…V…]∧Lgdur(V)). It connects β to α via a sequence-of-event inducing discourse relation type Sequence_of_Event_Rel. Discourse relations being binary illocutionary functions between speech act referents, within our TCL-type sortal semantics, they are part of the sortal hierarchy, and Sequence_of_Event_Rel corresponds to the supertype subsuming the Narration, Occasion and Result rhetorical functions (see Caudal 2022c).

5. Conclusions

The main contribution of the paper was to demonstrate that the meaning of LLI is broadly event-quantificational as well as temporally scalar (in a sense different from event scalarity, see Kennedy (2012)). We have seen that its scalar dimension is unrelated to event boundaries and changes-of-state measurement (notably qua incrementality, or so-called event scalarity), and rather involves a contextually determined temporal duration scale—and a related standard of comparison. We have proposed a formal treatment of this typologically unusual category at the semantics/pragmatics interface, reflecting on what we believe to be a kind of semantic/pragmatic complexity on a par with that of, e.g., tenses and temporal discourse connectives. We have specifically argued that it is at once a sentence-level marker, i.e., a VP-modifier constraining the aspectual type of VP-denoted event predicate, and a discourse connective-like item relating two distinct intonation units with respect to temporal ordering. Indeed, like aspectual modifiers, LLI imposes aspectual restrictions on the event predicate conveyed by the verb—it selects for durative atelic or telic event predicates (it either rejects or coerces atomic telic event predicates), and it often co-distributes with reduplication (full or partial), imperfective inflectional morphology and associated posture serial verb constructions (in the sense of Enfield (2002)), all of which have clear pluractional/iterative/durative effects in Iwaidja.

However, LLIs also behave like discourse-level aspectuo-temporal markers: they often associate with overt discourse connectives (e.g., the bartuwa discourse connective (‘and then/that’s it’), reinforcing the inherent temporal ordering function of LLIs, and making explicit their interaction with discourse structural parameters. Indeed, LLIs constrain the establishment of discourse relations as defined in Asher and Lascarides (2003); the rising pitch vs. low pitch intonation units involved in a LLI pattern such as Figure 1 must be related by Narration, Result or, exceptionally, Elaboration. These facts reflect, we argue, on the typologically complex and fine-grained grammar of event descriptions (especially with respect to event duration, closure and ordering) in Iwaidja, and in general, in Australian languages.

Author Contributions

Conception of field work experiments and questionnaires: P.C. and R.M.; data collection in the field: R.M., P.C. (with some assistance from Bruce Birch); writing—original draft preparation, P.C.; writing—review and editing, R.M.; supervision, R.M. and P.C.; project administration, P.C. and R.M.; funding acquisition, R.M. and P.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Labex Empirical Foundations of Linguistics (Agence Nationale de la Recherche programme Investissements d’Avenir, ANR–10LABX–0083), subprojects GD4, GL3 and MEQTAME (Strands 3 and 2) (CI: Patrick Caudal) (2010-), the CNRS SMI project Complexité morphologique et sémantique de la modalité en Iwaidja (2018–2019) (CI: Patrick Caudal), the CNRS FEMIDAL (‘Formal/Experimental Methods and In-depth Description of Australian Indigenous Languages’) International Research Project (2021-) (CI: Patrick Caudal), and by a Discovery Grant (DP130103935, CI Robert Mailhammer) by the Australian Research Council. The APC was funded by the Labex EFL (GL3, Strand 3, Project GL3, CI: Patrick Caudal).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Western Sydney University (H10237, 3 October 2013).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to our Iwaidja consultants and teachers for sharing their insights and discussing the data with us as well as for sitting through the experiments. We also thank Bruce Birch for discussions about Iwaidja from which many insights resulted, and for his support of our fieldwork.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

| LIST I | LIST II | LIST III | LIST IV | List V (19-11-2014) |

| 1. Door open | 1. Open closed door | 1. Open closed door | 1. Sad | 1. Singing no posture |

| 2. Baby sleeping | 2. Baby sleeping | 2. Baby sleeping | 2. Hanging | 2. Kissed |

| 3. Closed door | 3. Closed door | 3. Closed door | 3. Baby sleeping | 3. Baby sleeping |

| 4. Arguing1 fades in out | 4. Arguing1 fades in out | 4. Arguing1 fades in out | 4. Closed door | 4. Sang cooked |

| 5. Started Turning wheel II | 5. Started Turning wheel II | 5. Started Turning wheel II | 5. Extending arms | 5. Extending arms |

| 6. Sitting gave axe | 6. Sitting gave axe | 6. Sitting gave axe | 6. Open closed door | 6. Pierced |

| 7. Started drinking | 7. Started drinking | 7. Started drinking | 7. Black then white | 7. Sit down sneezes stands up |

| 8. Rob cutting Pat greeted | 8. Rob cutting Pat greeted | 8. Rob cutting Pat greeted | 8. White then black | 8. Crouch stand iterated |

| 9. Cutting the tree down | 9. Cutting the tree down | 9. Cutting the tree down | 9. Singing no posture | 9. Threw stone |

| 10. Started Running | 10. Started Running | 10. Started Running | 10. Coughing | 10. Lift crate frustrative |

| 11. Hanging up washing | 11. Hanging up washing | 11. Hanging up washing | 11. Spinning | 11. Open fridge |

| 12. Sleeping woke up | 12. Sleeping woke up | 12. Sleeping woke up | 12. Drinking | 12. Open fridge frustrative |

| 14. Peeling potato | 14. Peeling potato | 14. Peeling potato | 13. Blinking | 13. Hanging up washing interruption |

| 15. Thinking | 15. Thinking | 15. Thinking | 14. Kissed | 14. Was knocking ran by |

| 16. Cut tree down | 16. Cut tree down | 16. Cut tree down | 15. Squatting grinding | 15. Stood up jumped sat down |

| 17. Argued1 fades in out | 17. Argued1 fades in out | 17. Argued1 fades in out | 16. Sing whistle | 16. Cut bread |

| 18. Sleeping starts crying | 18. Sleeping starts crying | 18. Sleeping starts crying | 17. Whistle sing | 17. Push fridge frustrative succeed |

| 19. Cutting wood gave | 19. Cutting wood gave | 19. Cutting wood gave | 18. Squatting ground scratched | 18. Push fridge frustrative |

| 20. Took bottle | 20. Took bottle | 20. Took bottle | 19. Lying ground ate scratched | 19. Broke Stick |

| 21. Cut tree down saw | 21. Cut tree down saw | 21. Cut tree down saw | 20. Scratched started singing | 20. Rake sweep go |

| 22. Cutting bread II | 22. Cutting bread II | 22. Cutting bread II | 21. Squatting scratched ground | 21. Sneezing |

| 23. Sad | 23. Sad | 23. Sad | 22. Cooked sang | 22. Switch on |

| 24. Throwing stone imperf | 24. Throwing stone imperf | 24. Throwing stone imperf | 23. Shook took out bread | 23. Cut tree down saw |

| 25. Peeled potato | 25. Peeled potato | 25. Peeled potato | 24. Sang cooked | 24. Cutting wood gave |

| 26. Broke bottle | 26. Broke bottle | 26. Broke bottle | 25. Draw scratch sing | 25. Whistled sang whistled sang whistled |

| 27. Sat Drank Put Down | 27. Sat Drank Put Down | 27. Sat Drank Put Down | 26. Turned Wheel Looked out | 26. Eat biscuit |

| 28. Stood up left | 28. Stood up left | 28. Stood up left | 27. Turning looking | 27. Sneezing gave water |

| 29. Extending arms | 29. Extending arms | 29. Extending arms | 28. Slid grinding | 28. Switch off light |

| 30. Baby crying | 30. Baby crying | 30. Baby crying | 29. Scratching sing whistle | 29. Looking ate biscuit |

| 31. Spinning | 31. Spinning | 31. Spinning | 30. Started Running | 31. walked sat down slept woke up |

| 32. Jumping pointed | 32. Jumping pointed | 32. Jumping pointed | 31. Running | 32. Switch on and off |

| 33. Running | 33. Running | 33. Running | 32. Cutting branch | 33. Squatting ground scratched |

| 34. Cut bread | 34. Cut bread | 34. Cut bread | 33. Cut branch | 34. Kept dropping stone |

| 35. Hanging up washing interruption | 35. Hanging up washing interruption | 35. Hanging up washing interruption | 34. Breaking stick imperfective | |

| 36. Baby sleeping kissed | 36. Baby sleeping kissed | 36. Baby sleeping kissed | 35. Broke Stick | |

| 37. Cutting tree down saw | 37. Cutting tree down saw | 37. Cutting tree down saw | 36. Receiving | |

| 39. Started walking | 39. Started walking | 39. Started walking | 37. Received | |

| 40. Breaking stick imperfective | 40. Breaking stick imperfective | 40. Breaking stick imperfective | 38. Was piercing | |

| 41. Sleeping | 41. Sleeping | 41. Sleeping | 39. Pierced | |

| 42. Shook took out bread | 42. Shook took out bread | 42. Shook took out bread | 40. Throwing stone imperf | |

| 43. Coughing | 43. Coughing | 44. Jumped | 41. Threw stone | |

| 44. Jumped | 44. Jumped | 46. Sat down fell asleep | 42. Cutting bread II | |

| 46. Sat down fell asleep | 46. Sat down fell asleep | 48. Sit down sneezes stands up | 43. Cut bread | |

| 47. Jumping CUT BEG | 47. Jumping CUT BEG | 49. Turning looking | 44. Peeling potato | |

| 48. Sit down sneezes stands up< | 48. Sit down sneezes stands up< | 50. Walking sat | 45. Peeled potato | |

| 49. Turning looking | 49. Turning looking | 51. Turning wheel | 46. Cutting tree down saw | |

| 50. Walking sat | 50. Walking sat | 54. Threw stone | 47. Cut tree down saw | |

| 51. Turning wheel | 51. Turning wheel | 55. Broke Stick | 48. Sleeping woke up | |

| 52. Blinking | 52. Blinking | 56. Threw stone better | 49. Lying grinding jumped | |

| 53. Sit down sneezes< | 53. Sit down sneezes< | 57. Turned Wheel Looked out | 50. Cutting wood gave | |

| 54. Threw stone | 54. Threw stone | 58. Dug up | 51. Sat Drank Put Down | |

| 55. Broke Stick | 55. Broke Stick | 61. Kissed | 52. Sit down sneezes stands up | |

| 56. Threw stone better | 56. Threw stone better | 62. Hanging | 53. Walking sat | |

| 57. Turned Wheel Looked out | 57. Turned Wheel Looked out | 66. Laughing | 54. Lying eating jumped | |

| 58. Dug up | 58. Dug up | 67. Throw stick | 55. Hanging up washing interruption | |

| 59. Cutting branch imperfective | 59. Cutting branch imperfective | 68. Cut branch | 56. Sitting grinding gave | |

| 60. Drinking | 60. Drinking | 69. Was piercing | 57. Stood up jumped sat down | |

| 61. Kissed | 61. Kissed | 70. Cooked sang | 58. Was jumping ran by | |

| 62. Hanging | 62. Hanging | 71. Pierced | 59. Stood up knocked sat down | |

| 64. Threw stone up | 64. Threw stone up | 72. Scratched started singing | 60. Was knocking ran by | |

| 65. Sitting | 65. Sitting | 73. Sang cooked | ||

| 66. Laughing | 66. Laughing | 74. Sang scratched | ||

| 67. Throw stick | 67. Throw stick | 75. Received | ||

| 68. Cut branch | 68. Cut branch | 76. Receiving | ||

| 69. Was piercing | 77. Squatting grinding gave | |||

| 70. Cooked sang | 78. Squatting grinding | |||

| 71. Pierced | 79. Squatting ground scratched | |||

| 72. Scratched started singing | 80. Squatting scratched ground | |||

| 73. Sang cooked | 81. Sitting ate scratched ground | |||

| 74. Sang scratched | 83. Lying ground ate scratched | |||

| 75. Received | 84. Sitting grinding gave | |||

| 76. Receiving | 85. slid grinding | |||

| 77. Squatting grinding gave | 86. Lying eating jumped | |||

| 78. Squatting grinding | 87. Whistle sing | |||

| 79. Squatting ground scratched | 88. Sing whistle | |||

| 80. Squatting scratched ground | 89. Scratching sing whistle | |||

| 81. Sitting ate scratched ground | 90. Draw scratch sing | |||

| 82. Lying grinding jumped | ||||

| 83. Lying ground ate scratched | ||||

| 84. Sitting grinding gave | Discard 1. Door open | |||

| 85. slid grinding | ||||

| 86. Lying eating jumped |

Notes

| 1 | We use Leipzig Glossing Rules with the following addition: ant=anterior. We use the standard Australianist practical spelling: <rr> = /ɾ/, <rd> = /ɽ/, <ld> = /lɾ/, <rld> = /ɭɾ/, <rt> = /ɖ/, <rn> = /ɳ/, <ny> = /ɲ/ (Iwaidja) <nj> = /ɲ/ (Anindilyakwa), <ng> = /ŋ/, <rl> = /ɭ/, <y> = /j/, <h> = [ɰ]. Voicing in stops is not contrastive. We generally use voiced symbols, except for /g/ which is spelt <k>, so that sequences /ng/ can be easily distinguished orthographically (<nk>) from the velar nasal /ŋ/, which is written <ng>. |

| 2 | The lengthening part of the contour is signaled by an arrow on Figure 2; it lies on the final syllable of jamin, and is followed by a low tone, bounding IU situated on bartuwa. |

| 3 | While such intonational patterns are common in Australia, to the best of our knowledge they are only attested in some languages of Papua-New-Guinea (Bruno Olsson, p.c.) and possibly in some Austronesian languages (David Gil, p.c.). So at the global typological level, these phenomena seem to be rare, and restricted to a few zones of the world. |

| 4 | Discourse relations are discussed in a more detailed way further down the paper; see also Caudal and Bednall (this volume) for a more substantial discussion of their interaction with aspectuo-temporal parameters in general. |

| 5 | The various sets of EDED video clips, alongside with the relevant documentation, are accessible upon requests from the authors. To this day, EDED has been used by over 20 other researchers in the field, in order to elicit naturalistic event descriptions in a variety of languages. |

| 6 | Initials of the relevant informants are cited in the examples below, but their names cannot be disclosed here. |

| 7 | Overall, roughly 10 to 15% of the EDED-based descriptions offered by our informants contained LLI marking. However this figure should be considered with the utmost caution, as our elicitation protocols were not even throughout our corpus. Some of our EDED protocols involved prompting speakers for re-formulations in iterative contexts, while others did not; some early protocols did not comprise films with visual iteration of events, while later EDED protocols did. This resulted in significant variations in proportions of LLI in each series of EDED protocol. Also, there are obvious competence effects in the production of LLI. Elderly, more fluent speakers are more prone to using LLI than younger, less fluent speakers; this was independently observed by James Bednall and Patrick Caudal for similar lengthening phenomena in Anindilyakwa, also using EDED protocols. |

| 8 | As an aside, our corpus, like that of Caudal. |

| 9 | This is consistent with a general tendency among at least a number of Australian languages, not to semantically encode (a)telicity in a very rigid way. Iwaidja seems thus to also license non-culminating readings of ordinary, non-LLI marked utterances in the ANT involving seemingly telic verbs (in the sense of e.g., ‘non-culminating accomplishments’, cf. e.g., Martin and Demirdache 2020). See Caudal (2022a) for further details on that question in Iwaidja and other Australian languages. |

| 10 | We are departing from claims earlier made in Mailhammer and Caudal (2019), where it was argued that LLI did not tend to associate with accomplishment verbs. A more thorough corpus investigation has proven this generalization to be incorrect. |

| 11 | It is quite difficult to render in English the meaning of the corresponding reduplicated verb root. |

| 12 | Clearly, reduplication also has an expressive/evaluative dimension of meaning, hence its being often associated with various scalar/expressive meanings (depreciative/appreciative, etc.). See, e.g., Legentil (2019) for some observations about reduplication in Iwaidja along these lines. Posture SVCs do not seem to possess a similar expressive meaning, but they certainly convey a scalar temporal content (i.e., ‘for a long time’). |

| 13 | By ‘emphatic’, we mean that the speaker further emphasises the evaluative dimension of the temporal duration here measured—it is really, REALLY long. |

| 14 | Caudal (2022a) argues that from an areal typological point of view, reduplication and LLI are common markers for construing avertive readings in numerous Australian languages. |

| 15 | Moreover, whether or not the difference between the event’s duration, and the standard of comparison determined by (TD) is emphatic, might well be a contextual matter. When the prosody is extremely marked, or when additional durative markers are used (reduplication, SVCs), then the event being refered to seems to have significantly longer duration than the relevant standard of comparison—hence a feeling of emphasis. However, we will not attempt to formalise further here this possible context sensitivity, as our data is not sufficient for us to ascertain whether non-emphatic readings of LLI are possible, and if so, in what context they appear. |

| 16 | Instances of LLI in our corpus involved a past temporal anchoring; speakers seemed extremely reluctant to produce it outside of such contexts. Whether LLI can mark a present tense-marked utterance, providing it is an instance of so-called ‘narrative present’, is an empirical question we must leave open for future fieldwork. |

| 17 | For instance, providing a more precise account of (24) would require a detailed formal theory of the meaning of verbal reduplication in Iwaidja. Given the complexity of this question—morphologically, semantically and pragmatically—we cannot address it within the confines of this paper. However, see Legentil (2019) and Caudal et al. (2021) for some tentative, partial implementation, and an overview of this phenomenon. |

| 18 | It should be noted that we did not ascribe DP-type to the subject argument of the verb (unlike in e.g., Caudal et al. 2012), for the sake of simplicity—and because unless the verb receives an explicit subject NP in the syntax, it is actually debatable whether such projections are legitimate for verbal lexical entries given a polysynthetic language such as Iwaidja. |

| 19 | With the important proviso that aspectual coercion is seen as involving conventionalised bridging functions, as suggested in Caudal (2020); the latter reference observes that many aspectual coercion effects synchronically observed, are the result of construction-driven, lexical evolutions through time—therefore, they should not be regarded as lexically ‘abstract’, semantic-type driven functions. They are conventionalised uses of particular verbs (and/or particular grammatical forms). For want of sufficient data to clarify this issue, we will not discuss here the lexical/syntactic locus of the encoding of bridging functions attached to particular LLI-marked verbs. It could well be that these are collocational matters. For simplicity’s sake, we will simply assume they are lexical meaning-extension rules attached to verbs or verb classes. |

| 20 | e:atomic stipulates that e is of type atomic. Arguments, once bound, are removed from π. This notation indicates that e is an atomic event type. |