Abstract

Differential object marking (DOM) interacts with nominal structure in complex ways across Romance languages. For example, in Spanish, it has been claimed to ban bare nominals. For Romanian, in turn, two main restrictions have been discussed: (i) ban on overt definiteness on unmodified nominals; and (ii) ban on bare nominals, if the structure contains an overt modification. This paper has two main goals. First, it examines some contexts where these types of restrictions can be lifted for some speakers; such contexts allow us to grasp a better understanding of the limits of variation permitted by DOM in its interaction with nominal structure and determiner systems. Secondly, it proposes that a theory under which DOM signals a licensing strategy beyond Case can derive the variation patterns observed in the data. Subsequently, various parameters are examined, which encode (i) how specifications responsible for DOM interact with other features in the composition of nominals; and (ii) how the resulting complex containing DOM as well as other features is resolved at PF.

Keywords:

differential object marking; definiteness; bare noun; nominal licensing; Romanian; Spanish 1. Introduction

The phenomenon labeled differential object marking (DOM) is very common cross-linguistically. At its core it signals splits in the morpho-syntactic marking of direct objects, on the basis of features such as animacy, specificity, definiteness, etc. (Givón 1984; Bossong 1985, 1991, 1998; Comrie 1989; Lazard 2001; Aissen 2003; de Swart 2007; López 2012; Ormazabal and Romero 2013; Bárány 2017, a.o.). Many Romance languages exhibit typical DOM systems, regulated by animacy generally in conjunction with other specifications related to definiteness, specificity or topicality (Niculescu 1965; Rohlfs 1971; Roegiest 1979; Bossong 1998, a.o.). For example, descriptions of (standard and dialectal) Spanish (Laca 1995, 2006; Pensado 1995; Bruge and Brugger 1996; Torrego 1998; Leonetti 2003, 2008; Bleam 2005; Rodríguez-Mondoñedo 2007; López 2012; Ormazabal and Romero 2007, 2013, a.o.) indicate that objects which are animate and definite must carry obligatory differential marking, the latter homophonous with the dative preposition, as in (1-a). Inanimates, on the other hand, cannot have the same morphology and must, instead, stay unmarked, at least in contexts similar to (1-b)1.

| (1) | a. | Presentaron | *(a) | las | alumnas. | |

| present.pst.3pl | dat=dom | def.f.pl | student.f.pl | |||

| ‘They have presented (introduced) the female students.’ | ||||||

| b. | Presentaron | (*a) | los | proyectos. | ||

| present.pst.3pl | dat=dom | def.m.pl | project.m.pl | |||

| ‘They have presented the projects.’ | Spanish | |||||

| (2) | a. | L-au | prezentat | pe | un | important | |

| cl.3m.sg.acc-have.3pl | presented | loc=dom | a.m.sg | important.m.sg | |||

| lingvist. | |||||||

| linguist | |||||||

| ‘They have presented (introduced) an important linguist.’ | |||||||

| b. | Au | prezentat (*pe) | un | important | proiect. | ||

| have.3pl | presented loc=dom | a.n.sg | important.n.sg | project | |||

| ‘They have presented an important project.’ | Romanian | ||||||

| (3) | *DOM-Bare nominal. |

| (4) | a. | *Presentaron | a | alumnas. | ||

| present.pst.3pl | dat=dom | student.f.pl | ||||

| Intended. ‘They have presented (introduced) (the) female students.’ | ||||||

| b. | Presentaron | a | algunas | alumnas. | ||

| present.pst.3pl | dat=dom | some.f.pl | student.f.pl | |||

| ‘They have presented (introduced) some (specific) female students.’ | Spanish | |||||

| (5) | Siempre | golpean | *(a) | turistas. | |

| always | beat.pres.3pl | dat=dom | tourists | ||

| ‘They always beat tourists.’ | Spanish (García García2018, p. 225) | ||||

We are interested in examining such contexts in more detail, as well as the types of variation they give rise to.

A similar problem is seen in Romanian. In example (6-a) below, the differentially marked nominal which does not contain overt (in)definiteness is described as ungrammatical, even if it has adjectival modification and also clitic doubling. Just like in Spanish, to restore grammaticality either a definite or an indefinite determiner has to be added2. Note that in Romanian the definite is realized as a suffix.

| (6) | a. | ??/*I-am | văzut | pe | copii | frumoşi. | |

| cl.3pl.m.acc-have.1 | seen | loc=dom | children | beautiful.m.pl | |||

| Intended. ‘I’ve seen (the) beautiful children.’ | |||||||

| b. | I-am | văzut | pe | copiii | frumoşi. | ||

| cl.3pl.m.acc-have.1 | seen | loc=dom | children-def.m.pl | beautiful.m.pl | |||

| Intended. ‘I’ve seen the beautiful children.’ | |||||||

| c. | I-am | văzut | pe | un-i-i | copii | ||

| cl.3pl.m.acc-have.1 | seen | loc=dom | a-m.pl-def.m.pl | children | |||

| frumoşi. | |||||||

| beautiful.m.pl | |||||||

| Intended. ‘I’ve seen some (specific) beautiful children.’ | Romanian | ||||||

| (7) | a. | Am | văzut-o | pe | fată/*fat-a. | |

| have.1 | seen-cl.3f.acc.sg | loc=dom | girl/girl-def.f.sg | |||

| ‘I’ve seen the girl.’ | ||||||

| b. | Le-am | văzut | pe | fete/*fete-le. | ||

| cl.3f.acc.pl-have | seen | loc=dom | girl.f.pl/girl.f.pl-def.f.pl | |||

| ‘I’ve seen the girls.’ | Romanian | |||||

| (8) | *DOM-Modified nominal without overt (in)definiteness |

| (9) | *DOM-Overt definiteness on unmodified nominals. |

Proposal in a Nutshell

We propose that the two classes of restrictions are two sides of the same phenomenon. On the more formal side, we show that they are best derived under an account that takes DOM to signal an additional licensing operation on nominals, more specifically, a nominal licensing operation beyond uninterpretable Case ([uC]) per se (following Irimia 2020a, 2021). Points of variation arise, first, as a result of an overarching parameter related to whether DOM features are realized as an index on other independent functional projections (and their features thereof) via a process of bundling or not. In many Romance languages DOM appears to function as an index on other functional projections, the most frequently mentioned being the D head (see López 2012 for discussion). This property can be related to DOM’s nature as an anti-incorporation mechanism, filtering out nominals of type <e,t>, which function as predicates and can be interpreted as part of a (semantic) complex formed with V (Cornilescu 2000; Bleam 2005; López 2012; Ormazabal and Romero 2013, a.o.).

Following and adapting the observations in Irimia (2020a, 2021), referential definites contain relevant functional structure beyond the lexical contribution of the nominal. An important functional component is the D head associated with an uninterpretable Case ([uC]) feature, which requires licensing in the syntax. This allows referential definites to escape incorporation and function as true arguments. Given that the D head constructs arguments which escape (semantic) incorporation with V, DOM relevant features can be merged. But when such features are merged, for example grammaticalized animacy (which we encode here as Sent(ience), following Belletti 2018), an additional licensing mechanism will be triggered in the syntax. DOM related features have an important syntactic import, as detected, for example, in the numerous syntactic co-occurrence restrictions they give rise to (see especially Ormazabal and Romero 2007, 2013; López 2012 for Spanish, or Cornilescu 2020; Tigău 2020; Irimia, forthcoming for Romanian). The syntactic co-occurrence restrictions indicate that DOM features are related to nominal licensing in non-trivial ways. The result of the additional licensing operation, beyond ([uC]), on referential definites with grammaticalized animacy will be the spell-out of special morphology.

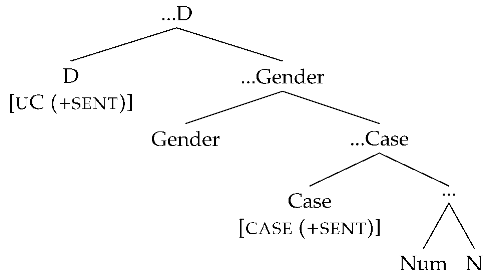

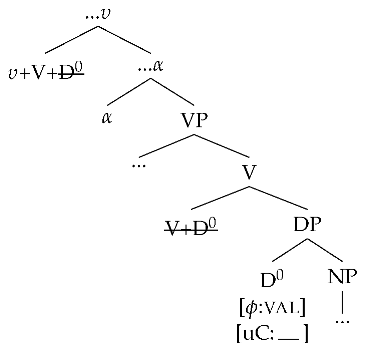

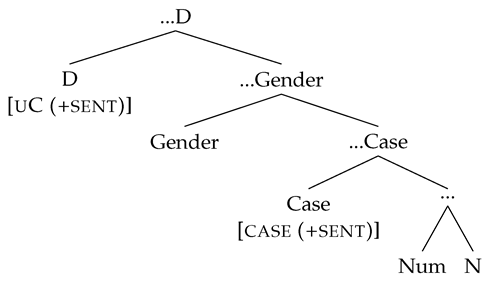

Bare nominals, on the other hand, have a more reduced structure. However, they are not as structurally simple as they might seem just by looking at their surface form. The data examined in this paper suggest that they can alternate between realizations as predicates of type <e,t> or as true arguments. What we would like to propose is that when they function as arguments, they contain a Case feature, merged lower in the nominal structure than [uC] in D, as schematically shown in (10).

| (10) |  |

In the data, the most salient features that can be merged in the lower Case projection and activate the low Case are focus, specificity, and genericity. Among these, focus appears to be the strongest. Most speakers mention that bare noun objects greatly improve under focus. For all speakers, DOM bare nouns need some type of interpretive correlation with features such as specificity or genericity, as we show in the next section.

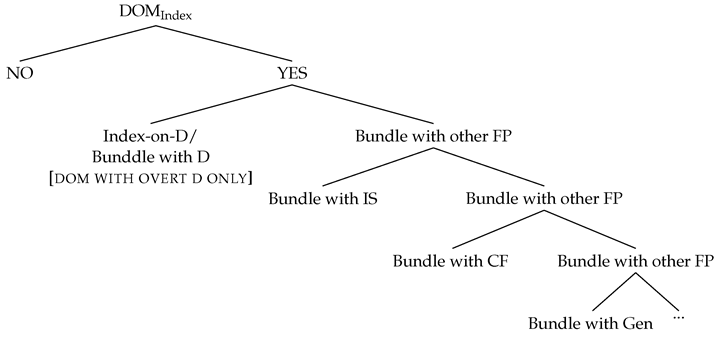

Putting all these observations together, we obtain various parameters, as listed below.

- Do DOM-related features bundle with other functional projections (i.e., are an index on an independent projection)?

- Do DOM-related features bundle with D (i.e., are an index on D)?

- Do DOM-related features bundle with Information Structure (Topic/Focus) features? (Mursell 2018; Belletti 2018; Leonetti 2004, 2008, a.o.)?

- Do DOM-related features bundle with other types of weak Case?

- In a bundle containing DOM-related features, are other features deleted at PF?

As we already mentioned, (1) is related to whether DOM features are an index on other, independent functional projections (and the features thereof), via a process of feature bundling, or are always an independent projection. (2), in turn, refers to whether DOM features are an index on D, or they can be merged independently of D. If the setting is specified as obligatory bundling with D, the relevant speakers will not permit DOM with categories that lack the D head, for example, bare nouns. As we discuss in the presentation of the data in the next section, there are indeed speakers who might not permit DOM with true bare nouns. Focusing our attention on speakers who allow DOM to be realized on bare nominals, we need to ask what types of features can DOM bundle with when they merge in the low Case projection, as discussed above. Here, there is an important split between the interaction of DOM with bare nouns under focus, as in parameter (3), and the interaction of DOM with bare nouns and other features that can activate the low Case, as in parameter (4). In turn, the bundling of DOM with other features predicts the existence of various types of PF effects, for example, deletion, as specified by parameter (5). As the restriction in (9) shows, this is exactly what we see in standard Romanian, where definiteness is deleted on unmodified nominals under DOM. The more detailed discussion in the next sections demonstrates, however, that the definite interpretation is maintained on the interpretive side, despite the absence of the definite morpheme on the surface. Thus, this is a purely PF process (Dobrovie-Sorin 2007; Giurgea, forthcoming, a.o.).

The structure of the paper is as follows. In Section 2 we illustrate the variation induced by DOM with determiner systems, and more precisely the definite, in Spanish. In Section 3 we turn to the points of variation seen in Romanian. Section 4 examines various theories of DOM as a nominal licensing strategy, as they are better equipped to address the data than accounts that see DOM just as a semantic mechanism related to specificity. However, as these accounts, originally formulated for Spanish, cannot fully capture the Romanian data, Section 5 proposes an adjustment, deriving DOM as an additional licensing mechanism on structurally complex nominals. Section 6 shows how variation can be addressed and accounted for, under the parametric options listed above. Section 7 concludes.

2. Spanish: *DOM-Bare Nominal

As mentioned in the introduction, an observation about standard Spanish (see especially López 2012: 12, fn.9, for discussion) is that the differential marker is not possible with a bare nominal. This is the restriction we have encoded in (3) and (4a) and which we repeat here under (11).

| (11) | *DOM-Bare nominal. | Spanish |

| (12) | a. | *Presentaron | a | alumnas. | |

| present.pst.3pl | dat=dom | student.f.pl | |||

| Intended. ‘They have presented (introduced) (the) female students.’ | |||||

| b. | *Vi | a | niño. | ||

| see.pst.1sg | dat=dom | child.m.sg | |||

| Intended. ‘I saw the/a child.’ | Spanish | ||||

| (13) | a. | Presentaron | a | las/unas | alumnas. | ||

| resent.pst.3pl | dat=dom | def.f.pl/a.f.pl | student.f.pl | ||||

| ‘They presented (introduced) the/some female students.’ | |||||||

| b. | Vi | al/ | a | un | niño. | ||

| see.pst.1sg | dat=dom-def.m.sg | dat=dom | a.m.sg | child.m.sg | |||

| Intended. ‘I saw the/a child.’ | Spanish | ||||||

| (14) | a. | Siempre | golpean | *(a) | turistas. | |||

| always | beat.3pl.pres | dat=dom | tourists | |||||

| ‘They always beat tourists’ | ||||||||

| b. | Aquí | odian | *(a) | mujeres. | ||||

| here | hate.3pl.pres | dat=dom | women | |||||

| ‘They hate women here.’ | ||||||||

| c. | Sobornarán | a | políticos | para | obtener | contratos. | ||

| bribe.3pl.fut | dat=dom | politicians | to | obtain | contracts | |||

| ‘They will bribe politicians to obtain contracts.’ | ||||||||

| d. | Mataron | a | jovenes. | |||||

| kill.pst.3pl | dat=dom | young | people | |||||

| ‘They killed young people.’ | ||||||||

| e. | No | puedes | herir | a | mendigos. | |||

| neg | can.pres.2sg | injure.inf | dat=dom | beggar.m.pl | ||||

| ‘You cannot injure beggars.’ | Spanish | |||||||

This latter observation seems to be confirmed by other works which have provided further observations about the interactions between DOM and bare objects. For example, Leonetti (2004, pp. 86–87), has discussed various contexts in which the presence of restrictive modifiers or focus renders DOM perfectly acceptable with bare nouns. Some illustrative examples are below:

| (15) | a. | ?? | Conocemos | a | profesores./✓Conocemos | a | profesores | |||

| know.1pl | dat=dom | teacher.m.pl/know.m.pl | dat=dom | teacher.m.pl | ||||||

| que | se | pasan | el | fin | de | semana | trabajando. | |||

| that | se | spend.pres.3pl | def.m.sg | end | of | week | working | |||

| ‘We know professors./We know professors who spend their weekend working.’ | ||||||||||

| (Leonetti 2004, ex. 14a) | ||||||||||

| b. | ?? | Detuvieron | a | hinchas./✓Detuvieron | a | |||||

| arrest.pst.3pl | dat=dom | supporter.m.pl/arrest.pst.3pl | dat=dom | |||||||

| hinchas | peligrosos | del | Atlético. | |||||||

| supporter.m.pl | dangerous.m.pl | of | Atlético. | |||||||

| ‘They arrested supporters./They arrested dangerous Atlético supporters.’ | ||||||||||

| (Leonetti 2004, ex. 14b) | ||||||||||

| c. | ?? | En | el | poblado | vi | a | pescadores./✓En | el | ||

| in | def.m.sg | village | see.pst.1sg | dat=dom | fisherman.m.pl/in | def.m.sg | ||||

| poblado | vi | a | PESCADORES, | no | a | turistas | ||||

| village | see.pst.1sg | dat=dom | fisherman.m.pl, | not | dat=dom | tourist.m.pl | ||||

| extranjeros. | ||||||||||

| foreign.m.pl | ||||||||||

| ‘In the village I saw fishermen./In the village I saw FISHERMEN, not foreign | ||||||||||

| tourists.’ | Spanish (Leonetti2004, ex. 14c) | |||||||||

3. Romanian: Two DOM Restrictions

Turning now to Romanian, as we have seen in the introduction, there are two interrelated problems. On the one hand, DOM cannot co-occur with overt definiteness, if the noun is unmodified. This restriction holds with both singular and plural nouns, as seen in (7), as well as in the sentences below:

| (16) | a. | Profesorul | le-a | premiat | pe | |

| professor.def.m.pl | cl.3f.pl.acc-have.3sg | awarded with a prize | loc=dom | |||

| studente(*-le). | ||||||

| student.f.pl-def.f.pl | ||||||

| ‘The professor awarded the female students with a prize.’ | ||||||

| b. | Ai | ajutat-o | pe | *femeia/✓femeie. | ||

| have.2sg | helped-cl.3sg.f.acc | loc=dom | woman.def.f.sg/woman | |||

| ‘You have helped the woman.’ | Romanian | |||||

| (17) | a. | I-au | invitat | pe | *(unii/nişte) | profesori | |

| have.3sg | invited | loc=dom | some.def.m.pl/some | professor.m.pl | |||

| importanţi. | |||||||

| important.m.pl | |||||||

| ‘They have invited some important professors.’ | |||||||

| b. | I-au | invitat | pe | profesori*(-i) | importanţi. | ||

| have.3sg | invited | loc=dom | professor.m.pl-def.m.pl | important.m.pl | |||

| ‘They have invited the important professors.’ | Romanian | ||||||

Relevantly for our purposes, the former restriction is lifted dialectally, while the latter appears to be more easily avoided in various registers of standard Romanian too. Given that blocking of definiteness on unmodified nouns is a special characteristic of Romanian, we will provide a basic overview to better ground its nature and subsequently derive its variation.

3.1. DOM and Article Drop in Romanian

The blocking effect of DOM with the definite suffix in standard Romanian has been addressed in both descriptive and formal orientations, and has given rise to a rich literature (see especially Pană Dindelegan 1997; Sala 1999; Dobrovie-Sorin and Giurgea 2006; Dobrovie-Sorin 2007; Mardale 2008; Nedelcu 2016, or Hill and Mardale 2021 for further references, a.o.).

The phenomenon has a clear PF nature (Dobrovie-Sorin 2007; Giurgea, forthcoming, a.o.), as despite the absence of the definite suffix on the surface, the definite interpretation on the unmodified nominal must be obligatorily maintained. As such, the sentence in (18-a) cannot be interpreted as an indefinite; an indefinite reading will require the obligatory spell-out of an indefinite marker, as in 54.

| (18) | a. | Le-am | văzut | pe | fete. | ||

| cl.acc.3f.pl-have.1 | seen | loc=dom | girls | ||||

| ‘I saw the girls.’ | |||||||

| # ‘I saw some girls.’/ # ‘I saw girls.’ | |||||||

| b. | Le-am | văzut | pe | unele/nişte | fete. | ||

| cl.f.3pl.acc-have.1 | seen | loc=dom | some.def.f.pl/some | girls | |||

| ‘I saw some of the girls/some of the girls’5. | Romanian | ||||||

We thus follow Dobrovie-Sorin (2007) in labelling it as ‘definite article drop’, a process otherwise seen with most prepositions in the language that take the accusative6. What we are interested in here is the observation that this DOM-Def restriction with unmodified nouns appears to be lifted in various dialects under certain conditions7. We have consulted three speakers of Serbian Romanian (Romanian spoken on the territory of Serbia) and 10 speakers of Moldovan (also called Moldavian) Romanian spoken on the territory of the Republic of Moldova. All the Serbian Romanian speakers accept examples such as (19); in fact, they mention that the variant with overt definiteness is better for them. Regarding Moldovan, 3 out of 10 speakers accept DOM with overt definiteness on unmodified nominals. These varieties are thus distinct from formal standard Romanian, where the ban against DOM and overt definiteness on unmodified nouns appears to be stricter. Some examples from varieties of Romanian (Serbian, and Moldavian) are given below8:

| (19) | a. | Am | văzut | pe | pescarul. | ||

| have.1sg | seen | loc=dom | fisherman.def.m.sg | ||||

| ‘I saw the fisherman.’ | Serbian Romanian | ||||||

| b. | Am | chemat | pe | primarul. | Serbian Romanian | ||

| have.1sg | called | loc=dom | mayor.def.m.sg | ||||

| ’I called the mayor.’ | Serbian Romanian | ||||||

| c. | I-a | invitat | pe | colegii. | |||

| cl.3m.pl.acc-have.3sg | invited | loc=dom | colleagues.def.m.pl | ||||

| ’S/he invited the colleagues.’ | Moldovan Romanian | ||||||

| d. | Le-a | bătut | pe | muierile. | |||

| cl.3m.pl.acc-have.3sg | beaten | loc=dom | women.def.f,pl | ||||

| ’S/he beat the women.’ | Moldovan Romanian | ||||||

| e. | O | adus-o | pe | vecina. | |||

| have.3pl | brought-cl.3f.sg.acc | loc=dom | neighbour.def.f.sg | ||||

| ‘They brought the female neighbour/our female neighbour.’ | Moldovan | ||||||

| f. | Să | îl | chemăm | aici | pe | primarul. | |

| sbjv | cl.3m.sg.acc | call.1pl | here | loc=dom | mayor.def.m.sg | ||

| ’Let’s summon the mayor here.’ | Moldovan Romanian | ||||||

3.2. DOM and Modified Nouns without Overt (in)Definiteness Marking in Romanian

Let’s turn now to the other restriction exhibited with DOM, namely the one that blocks the presence of a modified nominal without overt (in)definiteness. Apart from the problem of modification, this restriction is basically very similar to what we have seen in Spanish, where DOM is generally not possible with bare nouns. We repeat the descriptive content of the restriction here for both Romanian and Spanish, as well as the relevant Romanian example from the introduction. As we see in (22-a) vs (22-b) and (22-c) an object that contains modification is not grammatical with differential marking in the absence of an overt (definite or indefinite) determiner. A determinerless modified object can be used without differential marking, as in (22-d). This indicates that the problem comes from a restriction imposed by the differential marker.

| (20) | *DOM-Modified nominal without overt (in)definiteness | Romanian | |||||

| (21) | *DOM-Bare nominal. | Spanish | |||||

| (22) | a. | ??/*I-am | văzut | pe | copii | frumoşi. | |

| cl.3pl.m.acc-have.1 | seen | loc=dom | children | beautiful.m.pl | |||

| Intended. ‘I’ve seen the/some beautiful children.’ | |||||||

| b. | I-am | văzut | pe | copiii | frumoşi. | ||

| cl.3pl.m.acc-have.1 | seen | loc=dom | children.def.m.pl | beautiful.m.pl | |||

| Intended. ‘I’ve seen the beautiful children.’ | |||||||

| c. | I-am | văzut | pe | un-i-i | copii | ||

| cl.3pl.m.acc-have.1 | seen | loc=dom | a-m.pl-def.m.pl | children | |||

| frumoşi. | |||||||

| beautiful.m.pl | |||||||

| Intended. ‘I’ve seen some (specific) beautiful children.’ | |||||||

| d. | Am | văzut | copii | frumoşi. | |||

| have.1 | seen | children | beautiful.m.pl | ||||

| ‘I’ve seen beautiful children.’ | Romanian | ||||||

| (23) | a. | Ucid | pe | oameni | tineri. | |||

| kill.3pl | loc=dom | people.m.pl | young.m.pl | |||||

| ‘They kill young people.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Arestează | pe | politicieni | corupţi. | ||||

| arrest.3pl | loc=dom | politician.pl | corrupt.m.pl | |||||

| ‘They arrest corrupt politicians.’ | ||||||||

| c. | Condamnă | pe | doctori | spăgari. | ||||

| sentence.3pl | loc=dom | doctor.pl | easy | to | bribe | |||

| ‘They sentence doctors who take bribes.’ | ||||||||

| d. | Au | invitat | pe | profesori | celebri. | |||

| have.3pl | invited | loc=dom | professor.m.pl | famous.m.pl | ||||

| ‘They invited famous professors.’ | ||||||||

| e. | Au | consultat | pe | doctori | faimoşi. | |||

| have.3pl | consulted | loc=dom | doctor.pl | famous.m.pl | ||||

| ‘They consulted famous doctors.’ | ||||||||

| f. | Au | chemat | pe | specialişti | mari. | |||

| have.3pl | called | loc=dom | specialist.pl | great.m.pl | ||||

| ‘They called great specialists.’ | Romanian | |||||||

There appear to be important similarities with Spanish related to both the semantic make-up of the objects and the nature of the predicate. Thus, various predicates that select affected human objects, such as kill, arrest, sentence, etc. may suspend the restriction on obligatory (in)definiteness, as in (23-a), (23-b) or (23-c). In these sentences, the form without (in)definiteness is even better if a generic interpretation of the nominal is salient. Moreover, seeing the object as an authority also alleviates the restriction—in (23-d), (23-e) or (23-f), the doctors, the professors or the specialists are seen as prominent in their field, of high competence and reputation, thus qualifying adjectives such as ‘famous’, ’big name’, ‘well known’, ‘excellent’, etc10.

Another important observation is the following: DOM might be accepted with modified nominals lacking overt (in)definiteness only in the plural. With singulars, it results in ungrammaticality for all the speakers tested, as shown in (24). This, in itself, should not be surprising—count nouns in the singular are not possible in Romanian in the absence of overt (definite or indefinite) determiners, as seen in the examples in (25). The restriction against singulars applies to Spanish too, as in (12-b) or (56-a).

| (24) | a. | *Ucid | pe | om | tânar. | |||

| kill.3pl | loc=dom | man.m.sg | young.m.sg | |||||

| Intended: ‘They kill a/the young man.’ | ||||||||

| b. | *Au | invitat | pe | profesor | celebru. | |||

| have.3pl | invited | loc=dom | professor.m.sg | famous.m.sg | ||||

| Intended: ‘They invited a/the famous professor.’ | Romanian | |||||||

| (25) | a. | *Ucid | om | (tânar). | ||||

| kill.3pl | man.m.sg | young.m.sg | ||||||

| Intended: ‘They kill a/the (young) man.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Ucid | un | om/omul | (tânar) | ||||

| kill.3pl | a.m.sg | man.m.sg/man.def.m.sg | young.m.sg | |||||

| Intended: ‘They kill a/the (young) man.’ | ||||||||

| c. | *Au | invitat | profesor | (celebru). | ||||

| have.3pl | invited | professor.m.sg | famous.m.sg | |||||

| Intended: ‘They invited a/the (famous) professor.’ | ||||||||

| d. | Au | invitat | un | profesor/profesorul | (celebru). | |||

| have.3pl | invited | m.sg | professor.m.sg/professor.def.m.sg | famous.m.sg | ||||

| Intended: ‘They invited a/the (famous) professor.’ | Romanian | |||||||

| (26) | a. | Îi | ucid | pe | oameni | tineri, | în |

| cl.m.3pl.acc | kill.3pl | loc=dom | people.m.pl | young.m.pl | in | ||

| floarea | vârstei. | ||||||

| flower.def.f.sg | age.gen.f.sg | ||||||

| ‘They kill young people, at the peak of their age.’ | |||||||

| b. | Îi | consultă | DOAR | PE | PROFESORI | vestiţi, | |

| cl.3m.pl.acc | consult.3pl | only | loc=dom | professor.pl.m | famous.m.pl | ||

| de | mare | anvergură. | |||||

| of | great | status. | |||||

| ‘They consult ONLY famous professors, of great professional status.’ | |||||||

In summary, we see similarities between Spanish and Romanian when it comes to how DOM relates to bare nominals. The question is how to best derive these interactions and the patterns of variation they give rise to.

4. DOM and Nominal Structure

As we have seen, the ban on bare nominals has been traditionally taken to be an important trait of differential object marking at least for Spanish; this language has received much more attention than Romanian even in initial studies and also from a diachronic perspective. Laca’s (2006) data briefly mentioned in Section 2 point out to corpora across various historical periods where there are 0% occurrences of DOM with bare nominals. In fact, as we have seen, various works might qualify this restriction as exception-less (see also Laca 1995; Weissenrieder 1991; Fish 1967, a.o., for additional discussion).

The explanation has generally started from a semantic source; more specifically, another commonly assumed characterization of DOM in Romance takes it to be a grammatical mechanism for constructing specificity. Initial remarks, at least in descriptive and functional frameworks (see also Rohlfs 1971; Roegiest 1979; Fish 1967, a.o.), clearly linked the special morphology surfacing on certain animate objects to interpretations related to specificity. It appears to be the case that, in various contexts, there are interpretive differences between unmarked and marked objects. The latter can more easily accept a specific reading or must be restricted just to specific readings, as the traditional wisdom goes.

For Spanish, let’s look at a telling contrast as in (27), from López (2012). In (27-a) we see that DOM not only obtains a specific interpretation, but it also permits the indicative mood. The unmarked nominal in (27-b), on the other hand, does not accept any of these interpretive and grammatical possibilities. Only a non-specific interpretation is possible and the subjunctive, which signals non-specificity (and non-actualization) in Spanish (see especially Rivero 1979) must be used, instead.

| (27) | a. | María | buscó | a | una | gestora | que | habla | alemán. | |

| María | searched | dat=dom | a.f.sg | manager | that | speaks.ind | German | |||

| ‘Maria looked for a (specific) manager that speaks German.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | María | buscó | una | gestora | que | *habla/hable | alemán. | |||

| María | searched | a.f.sg | manager | that | speaks.ind/speaks.sbjv | German | ||||

| ‘Maria looked for a manager that could speak German.’ | Spanish | |||||||||

| (López 2012, ex. 38a, b, p. 18) | ||||||||||

| (28) | a. | Ion | iubeşte/admiră/caută | o | femeie. | |||

| Ion | love.3sg/admire.3sg/look for.3sg | a.f.sg | woman | |||||

| ‘Ion loves/admires/is looking for a (certain) woman.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Ion | o | iubeşte/admiră/caută | pe | o | |||

| Ion | cl.3m.sg.acc | love.3sg/admire.3sg/look for.3sg | loc=dom | a.f.sg | ||||

| femeie. | ||||||||

| woman | ||||||||

| ‘Ion loves a certain woman.’ | Romanian | |||||||

| (29) | Spanish | ||||||

| a. | Compré | libros. | |||||

| buy.pst.1sg | book.m.pl | ||||||

| ‘I bought books/# the books/# specific books.’ | |||||||

| b. | Compré | los | libros | / | algunos | libros. | |

| buy.pst.1sg | def.m.pl | book.m.pl | / | some.m.pl | book.m.pl | ||

| ‘I bought the books/some (specific) books.’ | |||||||

| (30) | Romanian | |||||||

| a. | Am | văzut | cărţi/copii. | |||||

| have.1 | seen | book.f.pl/child.m.pl | ||||||

| ‘I saw books/children.’ | ||||||||

| ‘# I saw the books/the children. | ||||||||

| ‘# I saw specific books/children.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Am | văzut | cărţi-le | / | une-le | cărţi. | ||

| have.1sg | seen | book.f.pl-def.f.pl | / | some-def.f.pl | book.f.pl | |||

| ‘I saw the books/some (specific) books.’ | ||||||||

| c. | Am | văzut | copii-i | / | uni-i | copii. | ||

| have.1 | seen | child.m.pl-def.m.pl | / | some-def.m.pl | child.m.pl | |||

| ‘I saw the children/some (specific) children.’ | ||||||||

The various contexts provided by García García (2018), López (2012), Rodríguez-Mondoñedo (2007), among many others, show that differential marking is natural and well-formed in contexts where non-specificity is signalled by explicit grammatical means. For example, in (31-a) DOM co-occurs with a non-specific quantifier (cualquiera ‘no matter who’) and the subjunctive, the latter a well-established marker of non-specificity, as just mentioned. Similar examples are seen in Romanian; in (31-b) the adjectival modifier indicating non-specificity, namely oarecare (‘whatsoever’, ‘random’, ‘no matter who’, etc.) is perfectly well-formed with differential marking. The non-specific context in (32), one of the classical examples provided by Cornilescu (2000), illustrates the same point: Romanian DOM is not restricted just to specific interpretations. Cornilescu (2000) proposes instead that the impossibility of DOM with bare nominals derives from DOM acting as a semantic filter on nominals. It blocks property interpretations, of type <e,t>, which are more typical to bare nouns.

| (31) | a. | María | buscó | a | una | gestora | cualquiera | que | |

| María | looked-for | dat=dom | a.f.sg | manager | no-matter-who | that | |||

| *habla/hable | alemán. | ||||||||

| speaks.ind/speaks.sbjv | German. | ||||||||

| ‘Maria looked for a manager (no matter who) that could speak German.’ | |||||||||

| (López 2012, ex. 38a, p. 18) | Spanish | ||||||||

| b. | L-am | întrebat/chemat | în | ajutor | pe | un | om | ||

| cl.3m.sg.acc-have.1 | asked/called | in | help | loc=dom | a.m.sg | man | |||

| oarecare. | |||||||||

| no-matter-who | |||||||||

| ’I have asked/asked for help a random man.’ | Romanian | ||||||||

| (32) | Fiecare | parlamentar | l-a | numit | secretar | pe | |||

| every | member | of | parliament | cl.3m.sg.acc-has | appointed | secretary | loc=dom | ||

| un | prieten. | ||||||||

| a.m.sg | friend | ||||||||

| ‘Every member of parliament has appointed a friend (of his) as a secretary.’ | |||||||||

| Romanian (Cornilescu 2000, ex.32) | |||||||||

| (34) | Spanish | |||||||

| a. | Juan | no | amó | *(a) | ninguna | mujer. | ||

| Juan | neg | loved | dat=dom | no.f.sg | woman | |||

| ‘John loved no woman.’ | (López 2012, ex. 25d, p. 13, adapted) | |||||||

| b. | Juan | no | vio | *(a) | nadie. | |||

| Juan | neg | saw | dat=dom | nobody | ||||

| ‘John didn’t see anybody.’ | ||||||||

| c. | Está | buscando | *(a) | alguien. | ||||

| be.3sg | look-for.ger | dat=dom | someone | |||||

| ‘S/he is looking for someone.’ | (Leonetti 2003, pp. 72–76) | |||||||

| (34) | Romanian | |||||||

| a. | Nu | am | văzut | *(pe) | nimeni. | |||

| neg | have.1 | seen | loc=dom | nobody | ||||

| ‘I didn’t see anybody.’ | ||||||||

| b. | Am | văzut | *(pe) | cineva. | ||||

| have.1 | seen | loc=dom | somebody | |||||

| ‘I saw somebody.’ | ||||||||

4.1. DOM and Nominal Licensing

The presence of differential marking in various contexts, which cannot be unified in terms of features such as specificity or wide scope, has shifted attention and inquiry to a more abstract nature of this phenomenon. The analysis proposed in the paper builds on accounts in this direction, more specifically analyses which connect the special marking with an abstract licensing need on certain classes of nominals, similar to (uninterpretable) Case13. In incarnations of the Minimalist Program based on Chomsky (2000) et subseq., abstract14 Case is taken to be among the features characterized as ‘uninterpretable’ (uninterpretable Case, abbreviated as [uC]), in the sense that they cannot be read at the interfaces. A special mechanism is assumed to be necessary that could eliminate such features before they reach the interfaces. Appropriate licensing of the relevant nominals by functional heads in the extended clausal structure is part of this mechanism. Thus, special morphology on the differentially marked nominals would be taken to signal, at spell-out, the elimination of the uninterpretable Case features via adequate licensing.

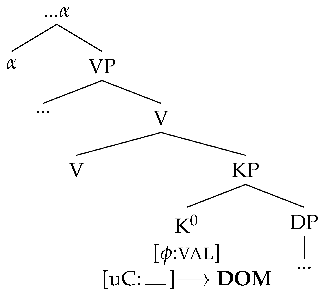

Against this general background, associating differential object marking with [uC] licensing was first proposed for Spanish (see especially Ormazabal and Romero 2007, 2013; López 2012; Bárány 2017, a.o.). For example, Ormazabal and Romero (2013) explicitly indicate that differentially marked nominals are the only type of objects that undergo licensing in the syntax. This is due to their containing a [uC] feature hosted in a KP layer in the extended nominal projection, as in the schematic representation in (35). Importantly, what is at stake is the complex structure of such nominals, as reflected in the presence of a KP layer, and not superficial features such as ‘specificity’. As a result, marked nominals might override the expected animacy and specificity restrictions, if the structure contains an extended functional layer without a specificity feature (such as the quantifiers illustrated in (33) or (34)). Similarly, as Ormazabal and Romero (2013) further observe, differential marking might become obligatory in contexts that signal nominal licensing, irrespective of animacy or specificity (such as small clauses or clause union configurations in which the shared argument has an object function, etc.)15.

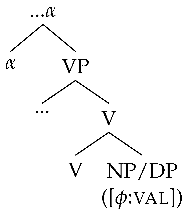

In this line of argumentation, unmarked nominals are assumed to systematically lack a [uC] feature and the KP layer. As a result, they do not need licensing in the syntax, and thus no special marking at PF. Unmarked nominals might contain just interpretable and valued -features (abbreviated here as [:val]), such as gender or number, as seen in (36). In fact, Ormazabal and Romero (2013) hypothesize that unmarked nominals in languages like Spanish might be the correspondent of nominals that undergo (pseudo-)incorporation with V in languages that illustrate this process more transparently.

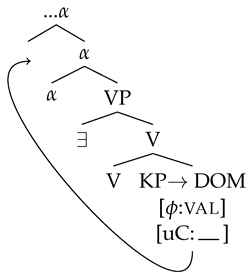

| (35) | differentially marked objects (building on Ormazabal and Romero 2013) |

| |

| (36) | unmarked objects |

|

4.2. López (2012): Types of Nominals and Their Licensing Requirements

Further refinements on the licensing accounts can be found in López (2012). A very important conclusion reached in this work is that, although analyzing marked nominals as categories that are subject to licensing is on the right track, what sets them apart from the unmarked ones is not necessarily the fact that the latter are always unlicensed. López (2012) provides several pieces of evidence motivating the conclusion that at least some types of non-differentially marked nominals must contain a [uC] feature. But, if there are types of unmarked nominals which contain a [uC] feature, similarly to the marked ones, the challenge is in understanding why only the latter are overtly signaled at PF.

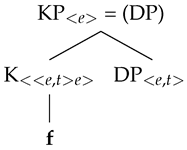

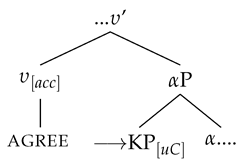

The analysis López (2012) proposes attributes the difference between marked and unmarked nominals to two crucial syntactic factors: (i) the precise featural composition of the K head in differential objects; (ii) a special licensing position of marked objects. More precisely, for López (2012), the Case feature in the K projection of marked nominals is associated with a choice function, as in (37); the choice function not only changes the semantic type of the nominal from <e, t > (or a higher type for quantifiers) to e, but it also requires the nominal to raise to a position above (existential closure at) VP, as it cannot be interpreted below VP. In a nutshell, the choice function in K requires short scrambling of the marked nominal to the specifier of , an intermediate functional projection between V and , as shown in (38). The head contains a conglomerate of applicative and aspectual features, explaining the dative surface morphology differential objects obtain in Spanish. The [uC] licenser is , and raising of the object to [Spec, ] brings the nominal to its immediate c-command position. As a result, the marked object carrying a [uC] feature linked to a choice function can be probed by (as part of an AGREE operation) and have its accusative [uC] feature licensed.

| (37) | Choice function in K | (López 2012, ex.13, p. 78) | |

| |||

| (38) | a. DOM raising (based on López 2012) | ||

| |||

| b. DOM—Accusative Case checking | (adapting López 2012) | ||

|

| (39) | [uC] licensing on unmarked definites (adapting López 2012) |

|

5. DOM beyond Case

Given that the differential marker is the spell-out of a K functional head, an immediate prediction is that it should not be possible with bare nominals. The latter do not contain a DP layer and thus the KP layer cannot be projected either. This raises questions about the types of interactions with bare nouns we are examining here. Additionally, although analyses of DOM as obligatory licensing (via raising) avoid the problems with specificity, they need some further adjustments for Romanian. Before introducing the analysis we propose to derive the variation patterns with bare nouns, we present some facts from Romanian.

5.1. Romanian DOM

We will be touching on three aspects related to the formalization of DOM in Romanian (see Cornilescu 2000; Cornilescu et al. 2017; Irimia 2020a; Hill and Mardale 2021, a.o., for further discussion). First, it is not clear how to independently motivate the process of D incorporation into V and subsequently into , so as to implement the structure in (39). This, in turn, leads to more detailed scrutiny into assumed positional differences between marked and unmarked objects. And, thirdly, the hypothesis that the K head in differentially marked objects contains a choice function, with all unmarked nominals lacking this piece of structure, does not follow as straightforwardly for Romanian.

The evidence López (2012) provides to support DOM raising to a position above VP comes from binding. More specifically, according to López (2012), Spanish differentially marked objects c-command the indirect object (IO), indicating that they must be higher. In the example below, a reading under which prisoners are matched to their own sons is possible, and thus it must be the case that the differentially marked object allows a quantifier-variable interpretation when paired with the indirect object. According to López’s (2012) judgments, this precise reading seems to be absent if the direct object shows up without the differential marker. These data follow immediately under short scrambling to the specifier of , as in (38), as this operation places DOM into a position that c-commands the IO. Given that the IO must be merged in the structure in a position between VP and (see López 2012 for details), it must be the case that DOM is merged even higher, and in any case above VP.

| (40) | Context: What did the enemies do? The enemies delivered X to Y and Z to W, but... | |||||||||

| Los | enemigos | no | entregaron | a | sui | hijo | a/∅ | ningún | prisionero. | |

| the | enemies | neg | delivered.pl | dat | his | son | dat=dom/∅ | no | prisoner | |

| ‘The enemies did not deliver any prisoner to his son.’ | (López 2012, ex. 18, p. 41) | |||||||||

Turning to Romanian, various works (more recently Tigău 2020; Cornilescu 2020; Irimia 2020b, 2021; Hill and Mardale 2021, a.o.) have pointed out that the Romanian binding facts are not that straightforward. These contributions note a complex picture: the various examples presented in Hill and Mardale (2021) show configurations in which binding from the differentially marked object into the IO does not go through, while binding from the IO into the DOM-ed nominal is fine, irrespective of the linear position of the IO and the differentially marked object. Tigău (2020) addresses quantificational dependecies within ditransitives, and identifies cases where DOM may bind into the (bare) IO, but when DOM is clitic doubled (using the accusative form of the clitic). It has been shown that clitic-doubled DOM has a high position in Romanian (see Cornilescu 2020 for recent discussion and exemplification); for example, it allows binding into external arguments, an option excluded in the context of DOM with no clitic doubling16. In general, the evidence from binding does not support the hypothesis that DOM has a higher position than unmarked nominals in Romanian; other types of diagnostics in its favor are equally hard to come by.

Another problem relates to the mechanism of choice function, which López (2012) assumes to be the crucial structural characteristic of marked objects, as opposed to the unmarked ones. Remember that the choice function in K, as in (37), is responsible not only for the scopal and interpretive variability of differentially marked objects (which, as we have seen, can be both specific or non-specific), but also forces the raising of the marked object above VP; the choice function cannot be interpreted below VP, according to López (2012). Crucially, López (2012) provides numerous examples which indicate that unmarked objects do not have the same flexibility: they appear to be restricted only to non-specific interpretations and are only possible with the subjunctive (a marker of non-specificity). We repeat here a relevant contrast:

| (41) | a. | María | buscó | a | una | gestora | que | habla | alemán. | |

| María | searched | dat=dom | a.f.sg | manager | that | speaks.ind | German | |||

| ‘Maria looked for a (specific) manager that speaks German.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | María | buscó | una | gestora | que | *habla/✓hable | alemán. | |||

| María | searched | a.f.sg | manager | that | speaks.ind/speaks.sbjv | German | ||||

| ‘Maria looked for a manager that could speak German.’ | Spanish | |||||||||

| (López 2012, ex. 38a, b, p. 18) | ||||||||||

| (42) | Romanian unmarked indefinites with specific readings | |||||

| a. | Ion | iubeşte/admiră/caută | o | femeie. | ||

| Ion | love.3sg/admire.3sg/look for.3sg | a.f.sg | woman | |||

| ‘Ion loves/admires/is looking for a (certain) woman.’ | ||||||

| b. | Ion | iubeşte/admiră/caută | o | femeie | anume. | |

| Ion | love.3sg/admire.3sg/look for.3sg | a.f.sg | woman | certain | ||

| ‘Ion loves/admires/is looking for a certain woman.’ | ||||||

We have thus motivated the following two conclusions about Romanian: (i) marked objects do not necessarily have a higher position than the unmarked ones; (ii) unmarked and marked indefinites are not set aside via the absence or presence of a choice function (a mechanism which was assumed by López 2012 to hold only with DOM). Additionally, we know from independent evidence that DOM is a syntactic mechanism in Romanian, related to nominal licensing (similarly to Spanish); for example, it gives rise to various types of co-occurrence restrictions which cannot be resolved in the morphology (see especially Cornilescu 2020; Tigău 2020; Irimia, forthcoming). But it does not seem to be the only possible licensing mechanism for nominals. Thus, we need to find a way to correctly set DOM apart from other nominals that are subject to licensing, and then see how the proposed account fares with respect to interactions with bare nominals.

5.2. DOM as an Additional Licensing Mechanism

The hypothesis we would like to explore in this paper is that DIM is linked to a nominal licensing mechanism beyond Case. It is important to note that relating DOM to information structure, generally signaling a type of (familiarity) topic is common in both descriptive and more formally oriented accounts. For Romance, see especially Leonetti (2004, 2008), Belletti (2018), Escandell-Vidal (2009), Hill (2013, 2017), Onea and Mardale (2020), Hill and Mardale (2021), a.o., and the for general cross-linguistic picture, Dalrymple and Nikolaeva (2011).

It appears undeniable that a link between DOM and topicality exists in many contexts across Romance; in fact, there are varieties such as Balearic Catalan where DOM is only possible on topical objects (see Escandell-Vidal 2009’s work for examples and extensive discussion). But it is equally clear that in various Romance languages, such as Spanish and Romanian, DOM is not restricted just to topicality. As López (2012) also notices, and as we have seen in the data presented in the paper, Spanish DOM is grammatical under focus, for example under contrastive focus. On the basis of contexts such as (43-a) or (43-b), López (2012) rejects an analysis in terms of information structure for Spanish DOM. Note that marked nominals under focus can be determiner-less (in the plural), as in (43-a), or can contain overt (definite) determiners, as in (43-b).

| (43) | Spanish DOM possible under focus | |||||||

| a. | Yo | contrato | A | TRADUCTORES, | no | A | REDACTORES. | |

| I | hire.1sg | dat=dom | translators | not | dat=dom | editors | ||

| ‘I hire TRANSLATORS, not EDITORS.’ (López 2012, ex. 44, p. 54, adapted) | ||||||||

| b. | Vi | AL | LADRÓN. | |||||

| see.pst.1sg | dat=dom-def.m.sg | thief | ||||||

| ‘I saw THE THIEF.’ | ||||||||

| (44) | Romanian DOM possible under focus | |||||||

| a. | Pe | cine | au | arestat? | ||||

| loc=dom | who | have.3pl | arrested | |||||

| ‘Who have they arrested?’ | ||||||||

| b. | L-au | arestat | PE | UN | CRIMINAL | FOARTE | ||

| cl.3m.sg.acc-have.3pl | arrested | loc=dom | a.m.sg | criminal | very | |||

| PERICULOS. | ||||||||

| dangerous.m.sg | ||||||||

| ‘They have arrested a very dangerous criminal.’ | ||||||||

| (45) | Romanian DOM possible under constrastive focus | |||||||

| a. | Pe | cine | au | lăudat? | ||||

| loc=dom | who | have.3pl | praised? | |||||

| ‘Who have they praised?’ | ||||||||

| b. | Au | lădat-o | PE | ADRIANA, | nu | PE | ||

| have.3pl | praised-cl.3sg.f.acc | loc=dom | Adriana, | neg | loc=dom | |||

| GEORGE. | ||||||||

| George | ||||||||

| ‘They have praised Adriana, not George.’ | ||||||||

| (46) | a. | Pe | haină, | nu | o | mai | vreau. | |||

| loc=dom | coat, | neg | cl.3sg.f.acc | more | want.1sg | |||||

| ‘The coat, I don’t want it, after all.’ | CLLD | |||||||||

| b. | Nu | mai | vreau | (*pe) | haină/✓ | haina | /✓ | o | haină. | |

| neg | more | want.1sg | loc=dom | coat/ | coat.def.f.sg/ | a.f.sg | coat | |||

| ‘I don’t want the coat/a coat.’ | Romanian | |||||||||

| (47) | Romanian animates under CLLD | |||||||||

| a. | Fata | frumoasă, | nu | am | mai | văzut-o. | ||||

| girl.def.f.sg | beautiful.f.sg | neg | have.1sg | more | seen-cl.3f.sg.acc | |||||

| Lit. ‘The beautiful girl, I haven’t seen her anymore.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Pe | fata | frumoasă, | nu | am | mai | ||||

| loc=dom | girl.def.f.sg | beautiful.f.sg | neg | have.1sg | more | |||||

| văzut-o. | ||||||||||

| seen-cl.3f.sg.acc | ||||||||||

| Lit. ‘The beautiful girl, I haven’t seen her anymore.’ | ||||||||||

Two recent contributions by Irimia (2020a, 2020b) have proposed a further adaptation of licensing accounts such as the various aspects of differential marking can be captured in a uniform way for both Romanian and Spanish. The main tenet in these accounts is that DOM can be unified as signaling an additional licensing operation beyond the valuation of [uC], irrespective of information structure. Other languages, even non Indo-European, have been shown to follow the same structural make-up for DOM in Irimia (2021).

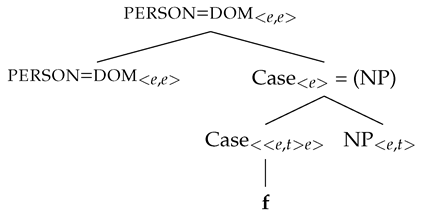

The crucial observation is that a nominal can contain more than one feature that requires licensing. As a result, this complex type of nominal can enter into multiple licensing operations such that all the features can get licensed (following, for example, Béjar and Rezac 2009). Here, we further adapt an account along these lines. The more precise formulation starts from the (generally assumed) characterization of DOM as restricted to categories with argumental status, which escape incorporation with V. As we mentioned above, a long line of research following Cornilescu (2000) takes DOM to be a denotation filter on objects, isolating the categories of type e. What we would like to explore is an additional restriction on DOM: the differential marker does not signal argumental status, but nominal classes that contain additional specifications beyond the structure signaling their argumental status. One way to implement this is to assume that the additional feature(s) on DOM denote(s) a partial function of type ⟨e, e⟩ defined only for individuals (of type e) building on Heim and Kratzer’s (1998) analysis of gender features. This formalization would be different from López’s (2012) proposal in (37) according to which the choice function in K, responsible for differential marking, changes the semantic type of the nominal from <e, t > (a predicate)19 to e. We have seen that this latter hypothesis is not enough for Romanian, where unmarked indefinites need a choice function too.

The presence of a structural Case feature that requires licensing is one of the means to obtain a nominal with argumental status, of type e. DOM involves an additional licensing operation beyond the valuation of structural Case (which outputs a nominal with argumental status). At PF, the result of this additional licensing operation is the spell-out of the oblique marker on differentially marked objects.

6. Patterns of Variation

The apparatus we have introduced above allows us to start addressing the patterns of variation we have identified in the interaction of differential marking with determiner systems. We need to mention first two other formal aspects that are important in the analysis of DOM.

First, we follow recent discussions (Cornilescu 2000; Rodríguez-Mondoñedo 2007; Richards 2008; Adger and Harbour 2007, or Ledgeway et al. 2019, a.o.) which take the difference between grammaticalized animates and inanimates to be linked to the presence of a [+ person] specification in the composition of the former. More generally, this feature can be taken to signal the relevance of grammaticalized animates in the discourse. Adapting the terminology in Belletti (2018), we assume certain nominals contain a functional head labeled Sentience hosting [+ person] and signalling the grammaticalized animates the speaker relates to due to their discourse salience.

Secondly, it is necessary to say a few words about another important parameter related to the nature of DOM, namely its status as an index on an independent functional projection. We mentioned above that in some analyses (see especially López 2012) differential object marking is formalized as signaling an index on D. This explains why overt D-related morphology (the definite, etc.) is obligatory for some speakers in the context of differential marking. However, the hypothesis of an index on D does not easily explain grammaticality with bare nouns, at least for certain speakers, as discussed in the paper. Here we would like to maintain the hypothesis that DOM acts as an index; however, to derive the facts, the parameter needs to be formulated in wider terms, more specifically whether DOM is an index on a separate functional projection (which constructs an argument of type e) or can be merged separately. DOM as an index on D is just a setting of this larger parameter.

The idea of an index on a separate functional projection can also be captured by using a description in terms of feature bundling, that is the situation in which a given functional head contains more than one (independent) feature. The importance of feature (and head) bundling in narrow syntax was first extensively explored by Pylkkänen (2008) in the domain of Voice-related phenomena. Here, we are employing the same concept to the realm of DOM.

Let’s now look at the options permitted by this system, as illustrated by the five parameters below and in the options in (48). First, when macroparameter (1) is set as NO, differential marking is predicted to be realized as an independent functional projection, which does not bundle with other projections. The cases we are most concerned with are those related to bundling, which appear to be salient in Romance languages. In this class, if DOM is set as an index of D or as bundling with D, then it will be ungrammatical on nominals that do not have an (overt) D head. We have seen that for some speakers, this is indeed the case, as DOM is not grammatical if overt D-related morphology is missing. In turn, if no bundling with D is obligatory, we need to ask the question of whether bundling with other projections/types of features is possible.

Going back to the data, we have shown that bare nouns become acceptable with DOM under processes related to Information Structure (Focus, or Topic), as well as if a specific or generic interpretation is possible. But if a D head is not merged, what do DOM-related features bundle with when these interactions are possible? What we would like to propose is that DOM-related features can bundle with a functional projection (FP) hosting a low Case feature, merged lower than D, as in (49). There are various possibilities to activate low Case—for example, when a Focus feature is merged, predicting interactions with Information Structure (IS); or when the projection hosts a choice function (CF), deriving specificity, or when a variable merged there is bound by an implicit generic (Gen) operator higher in the clause.

- Do DOM-related features bundle with other functional projections (i.e., are an index on an independent projection)?

- Do DOM-related features bundle with D (i.e., are an index on D)?

- Do DOM-related features bundle with Information Structure (Topic/Focus) features? (Mursell 2018; Belletti 2018; Leonetti 2004, 2008, a.o.)?

- Do DOM-related features interact with (other tyoes of) weak Case (e.g., choice function or genericity introduced lower than D)?

- In a bundle containing DOM-related features, are other features deleted at PF?

| (48) | |

| |

| (49) | |

|

Before turning to the interactions with weak Case a more general question is salient (as also remarked by one of the reviewers): why is it that these types of features are relevant to DOM, as opposed to other possible features? For example, why would information structure, specificity, or genericity matter? Why would the presence of a D head (with its associated features) be important? Although we cannot give a full answer to this question (which requires an extensive investigation of a larger database of DOM contexts), we would like to emphasize once more an observation regarding DOM we have already mentioned. In various accounts (see Cornilescu 2000, Bleam 2005; López 2012, a.o.) it has been shown that the true nature of this type of marking lies in its acting as an anti-incorporation mechanism. More specifically, it is a strategy in the grammar of human languages which blocks the functioning of the nominal as a predicate that might construct a complex predicate with V.

As we pointed out above, for Cornilescu (2000) DOM is a filter which blocks categories of type <e,t >. Note that what is at stake here is the notion of semantic (anti)incorporation, which might not necessarily have a syntactic correlate in the sense that it does not need to entail V-NP adjacency, for example. As we discuss below, focus, specificity, etc., have independently been shown to either create or reinforce a nominal’s status as an argument or introduce a structural Case feature; these mechanisms independently prevent semantic incorporation (see, for example, de Hoop 1996; Meinunger 2000, a.o.) and introduce structure on the nominal which requires adequate licensing in the syntax. Thus, they are optimal candidates as categories with which DOM-related features can bundle. This leaves open the possibility of DOM bundling with other features that might have the same status. In fact, one of the reviewers mentions that affectedness appears to be relevant to (at least some of) the Spanish examples with DOM and bare nouns. As the results we obtained from the native speakers do not unambiguously signal affectedness, we do not discuss it here. Note however that, although this notion is notoriously difficult to capture, it has been noticed that it comes with important syntactic and morphological correlates cross-linguistically: a higher position, dedicated Case marking, etc., signaling nominals that behave like true arguments.

6.1. DOM Bare Nouns and Interactions with Information Structure

The data we have introduced in Section 2 have shown that Information Structure processes, such as topicalization or focus can lift restrictions introduced by DOM even on nominals that are not found in an overtly dislocated position. Remember that in Spanish, the restriction repeated in (50) has been claimed to apply to DOM, explaining why examples such as (51) which involve DOM with bare nominals are ungrammatical:

| (50) | *DOM-Bare nominal. | Spanish | ||

| (51) | *Presentaron | a | alumnas. | |

| present.pst.3pl | dat=dom | student.f.pl | ||

| Intended. ‘They have presented/introduced (the) female students.’ | Spanish | |||

| (52) | ?? | En | el | poblado | vi | a | pescadores./✓En | el |

| in | def.m.sg | village | see.pst.1sg | dat=dom | fisherman.m.pl/in | def.m.sg | ||

| poblado | vi | a | PESCADORES, | no | a | turistas | ||

| village | see.pst.1sg | dat=dom | fisherman.m.pl | not | dat=dom | tourist.m.pl | ||

| extranjeros. | ||||||||

| foreign.m.pl | ||||||||

| ‘In the village I saw fishermen./In the village I saw fishermen, not foreign tourists.’ | ||||||||

| (Leonetti 2004, ex. 14c) | ||||||||

López (2012) proposes a different explanation for examples such as (52), while still maintaining the hypothesis that DOM spells out a KP category, which switches the object’s type to e. The main assumption is that information-structure-related mechanisms construct DPs, which have a null D (see (Irimia 2020b) for similar remarks regarding Romanian). The result is that grammaticalized animacy will force overt differential marking on those types of bare nouns that are DPs as a result of the presence of focus or topic. We do not follow this solution here as it makes a prediction that is not met by the data. Standard Spanish definite animates, which contain the D head, need obligatory DOM. For all the speakers consulted here, the sentence below is ungrammatical without differential marking (under a referential interpretation of the definite):

| (53) | Vi | *(a) | los | pescadores. | |

| see.pst.1sg | dat=dom | def.m.pl | fisherman.m.pl | ||

| Intended: ‘I saw the fishermen.’ | Spanish | ||||

| (54) | Vi | (a) | PESCADORES. | |

| see.pst.1sg | dat=dom | fisherman.m.pl | ||

| Intended: ‘I saw FISHERMEN.’ | Spanish | |||

| (55) | Juan | no | vio | *(a) | nadie. | |

| Juan | neg | saw | dat=dom | nobody | ||

| ‘John didn’t see anybody.’ | Spanish | |||||

Independent evidence that DOM signals an additional licensing mechanism comes from its interaction with bare singulars of count nouns. As opposed to bare plurals, these always give rise to ungrammaticality (irrespective of focus, or other specifications). In (56-a) we see a DOM bare singular in Spanish which is ungrammatical to all the speakers consulted, and in (56-b) a DOM singular on a nominal with modification in Romanian, which is equally ungrammatical:

| (56) | a. | *Vi | a | profesor/A | PROFESOR. | ||||

| see.pst.1sg | dat=dom | professor | |||||||

| Intended. ‘I saw a/the professor/PROFESSOR.’ | Spanish | ||||||||

| b. | *Am | prins | pe | hoţ/HOŢ | periculos, | care | a | atacat | |

| have.1 | caught | loc=dom | thief | dangerous.m.sg | who | have.3sg | attacked | ||

| mai | muţi | oameni. | Romanian | ||||||

| more | many | people | |||||||

| Intended. ‘I caught a/the dangerous thief/THIEF who has attacked several | |||||||||

| people.’ | |||||||||

6.2. DOM Bare Nominals and Their Interaction with Other Types of Weak Case

The examples examined in this paper have revealed that DOM is possible on bare nouns in another context, namely when there is heavy modification and the nominals are interpreted as specific. We repeat some examples below, from both Spanish and Romanian. In Romanian, according to what the native speakers mention, such examples are even better when the objects refer to prominent animate entities, well known for their attributes:

| (57) | a. | ?? | Conocemos | a | profesores./ | ✓Conocemos | a | profesores | ||

| know.1pl | dat=dom | teacher.m.pl/know.m.pl | dat=dom | teacher.m.pl | ||||||

| que | se | pasan | el | fin | de | semana | trabajando. | |||

| that | se | spend.m.pl | def.m.sg | end | of | week | working | |||

| ‘We know professors./We know professors that spend their weekend working.’ | ||||||||||

| (Leonetti 2004, ex. 14a) | ||||||||||

| b. | ?? | Detuvieron | a | hinchas./ | ✓Detuvieron | a | ||||

| arrest.pst.3pl | dat=dom | supporter.m.pl/arrest.pst.3pl | dat=dom | |||||||

| hinchas | peligrosos | del | Atlético. | |||||||

| supporter.m.pl | dangerous.m.pl | of | Atlético. | |||||||

| ‘They arrested supporters./They arrested dangerous Atlético supporters.’ | ||||||||||

| (Leonetti 2004, ex. 14b) | Spanish | |||||||||

| (58) | a. | Au | consultat | pe | doctori | faimoşi. | ||||

| have.3pl | consulted | loc=dom | doctor.pl | famous.m.pl | ||||||

| ‘They consulted famous doctors.’ | ||||||||||

| b. | Îi | consultă | doar | pe | profesori | vestiţi, | de | |||

| cl.3m.pl.acc | consult.3pl | only | loc=dom | professor.pl.m | famous.m.pl | of | ||||

| mare | anvergură. | |||||||||

| great | status. | |||||||||

| ‘They consult famous professors, of great professional status.’ | Romanian | |||||||||

| (59) | Choice function in Case and dom |

| |

| (60) | Romanian unmarked indefinites with specific readings | |||||

| a. | Ion | iubeşte/admiră/caută | o | femeie. | ||

| Ion | love.3sg/admire.3sg/look for.3sg | a.f.sg | woman | |||

| ‘Ion loves/admires/is looking for a (certain) woman.’ | ||||||

| b. | Ion | iubeşte/admiră/caută | o | femeie | anume. | |

| Ion | love.3sg/admire.3sg/look for.3sg | a.f.sg | woman | certain | ||

| ‘Ion loves/admires/is looking for a certain woman.’ | ||||||

What about the generic interpretations? According to the speakers they are possible with bare nouns under DOM. An example is repeated in (61), from García García (2018).

| (61) | Siempre | golpean | *(a) | turistas. | |

| always | beat.3pl.pres | dat=dom | tourists | ||

| ‘They always beat tourists’ | Spanish | ||||

However, there are differences between focus, on the one hand, and specificity and genericity, on the other hand. Topic/Focus give rise to uniformly higher rates of acceptability when it comes to DOM and bare nouns. For various speakers, DOM with bare nouns is only possible under information-structure specifications with clear prosodic effects (special intonation, etc.). Thus, a distinction between contexts such as (52) vs. (57). Also, the addition of Focus renders the examples with DOM bare nouns and heavy modification even better. In fact, none of the consultants mentioned they would accept bare nouns with DOM under specificity, while rejecting bare nouns with DOM under Topic/Focus. This indicates that the latter have a more profound affinity with DOM, probably because the presence of Information Structure features can more easily force an argumental status of the bare nominal. For this reason, we have separated bundling with Focus under a different parameter.

Now, let’s also turn to the following question. What about the speakers who do not accept DOM with bare nouns? We assume that the answer resides in the nature of the lower Case features, which are ‘weaker’ than the [uC] feature in D. We rephrase the distinction as follows: the latter Case feature is introduced on a head, such as D, which acts as a phase edge, constructing a ‘complete’ nominal category, and thus requiring obligatory licensing in sentential syntax. As a result, the nominal is forced to escape complex predicate formation with V. The lower Case, in contrast, does not require obligatory licensing in sentential syntax, is introduced on a projection that is not the phase edge, and might require activation by other pieces of structure inside the extended projection of the nominal. We would like to propose that this distinction is related to a non-trivial dichotomy of features that are involved in the licensing of nominals. Recently, various formal approaches have supported a non-unitary view about feature licensing: some features do not lead to crash if left unlicensed, while others must be obligatorily licensed (see especially Preminger 2014). The Case features seen with DOM bare nominals are more similar to the ones that do not lead to crash if left unlicensed.

Given that the presence of the lower Case feature does not lead to crash if left unlicensed, there are at least two possible explanations when it comes to the speakers who might not accept DOM with bare nominals: (i) either the low Case feature is not activated, possibly because the type of specificity, genericity, etc. is not strong enough or is not actually grammaticalized for this second class of speakers; (ii) the Case feature is activated, but stays unlicensed, because only the Case feature on a phase head needs obligatory licensing.

Taking this into accounts, the data give rise to yet another question: given that some Case features can be weak as they do not require obligatory licensing, one prediction would be that such features could actually get deleted at PF, as in a bundle with DOM-related features the latter introduce obligatory licensing on the nominal anyway. Is this prediction borne out?

6.3. DOM Bundling and PF Effects

This problem is related to parameter 5, repeated here. We will say a few words about this option too, given that a definiteness morpheme deletion process has actually been claimed to apply to Romanian. We cannot, however, provide an exhaustive discussion as the issue goes beyond the problem of DOM per se (it is seen with most prepositions introducing the accusative, as we have mentioned), as well as beyond the data and space available here.

- 5.

- In a bundle of features containing DOM-related features, are other features deleted at PF?

Standard Romanian examples such as (62) have always been a source of puzzle. As we have mentioned, the problem is that DOM does not allow an overt definite, even if the interpretation of the nominal is a definite one. The relevant restriction has been formulated as in (63):

| (62) | a. | Am | văzut-o | pe | fată/*fata. | |

| have.1 | seen-cl.f.sg.acc | loc=dom | girl/girl.def.f.sg | |||

| ‘I’ve seen the girl.’ | ||||||

| b. | Le-am | văzut | pe | fete/*fetele. | ||

| cl.3f.acc.pl-have | seen | loc=dom | girl.f.pl/girl.f.pl-def.f.pl | |||

| ‘I’ve seen the girls.’ | Romanian | |||||

| (63) | *DOM-overt definiteness on unmodified nominals. | Romanian | ||||

| (64) | a. | Am | văzut-o | pe | fata | frumoasă | / | *fată | |

| have.1 | seen-cl.f.sg.acc | loc=dom | girl.def.f.sg | beautiful.f.sg | / | girl.f.sg | |||

| frumoasă. | |||||||||

| beautiful.f.sg | |||||||||

| ‘I saw the beautiful girl.’ | |||||||||

| b. | Le-am | văzut | pe | fetele | frumoase | / | |||

| cl.3f.acc.pl-have.1 | seen | loc=dom | girl.f.pl-def.f.pl | beautiful.f.pl | / | ||||

| *fete | frumoase. | ||||||||

| girl.f.pl | beautiful.f.pl | ||||||||

| ‘I saw the beautiful girls.’ | Romanian | ||||||||

In fact, Dobrovie-Sorin (2007) has attributed the absence of overt definiteness in examples like (62) to a rule (applying at PF or even in narrow syntax) which deletes the definite article when the latter occurs inside an extended head formed by the N and P. There are two steps involved in the formation of this complex head, as in (65) and (66). A rule subsequently applies that deletes the article, as it is found in the same Extended Head as the Preposition. The rule is in (67).

| (65) | (i) D and N form a complex head: [P [Det [N ] ] ] → [P [D0/N0 Det & N ] ] | |

| (66) | (ii) P forms a complex head with D and N: [P [D0/N0 Det & N ] ] → [P0/D0/N0 P&Det | |

| & N ] ] | ||

| (67) | The definite article is deleted whenever it is governed by a preposition that belongs | |

| to the same extended head. | (adapted from Dobrovie-Sorin 2007) | |

| (68) | P does not form a complex head with D and N: [P [D0/N0 Det & N ] ] → [P [D0/N0 |

| Det & N ] ] |

7. Conclusions

This paper has addressed some points of variation introduced by differential marking in its interaction with bare nouns. It has explored the nature of three restrictions that have been assumed to hold with DOM in Spanish and Romanian. First, the paper touched on the restriction in (69) which has been formulated to explain why DOM is not possible with bare nominals in Spanish.

| (69) | *DOM-Bare nominal. | Spanish |

| (70) | *DOM-Modified nominal without overt (in)definiteness | Romanian |

| (71) | *DOM-overt definiteness on unmodified nominals. | Romanian |

The paper has proposed, first, that a theory under which DOM is seen as an additional licensing mechanism on nominals of type e is more adequate in that it not only better accounts for the Romanian facts, unifying them with Spanish, but it also opens the path to addressing points of variation. Five parameters have been illustrated which refer to (i) how the specifications responsible for DOM interact with other features in the nominal structure; and (ii) how the resulting bundle containing DOM-related features as well as other features is resolved at PF:

- Do DOM-related features bundle with other functional projections (i.e., are an index on an independent projection)?

- Do DOM-related features bundle with D (i.e., are an index on D)?

- Do DOM-related features bundle with Information Structure (Topic/Focus) features? (Mursell 2018; Belletti 2018; Leonetti 2004, 2008, a.o.)?

- Do DOM-related features interact with weak Case?

- In a bundle containing DOM-related features, are other features deleted at PF?

These parametric options are, in fact, predicted by current theories on nominal licensing and the syntax-PF interface. It is thus not surprising to see that the loci of variation they encode are borne out in the data. Remaining questions for future research relate to whether the types of variation discussed here are also seen in other Romanian and Spanish varieties, in other Romance languages with robust DOM systems more generally, or in other languages with robust DOM and rich determiner systems. Another important aspect is that the restrictions related to DOM and bare nouns cannot be overridden across the board, and not all examples in which they might be overridden have the same level of acceptance. Hopefully, future work will provide further insight into these more refined parameters too.

Funding

This work has been supported by a research grant provided by the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

A big thank you goes to the three anonymous reviewers for their very useful and constructive feedback. All errors are our own.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

acc = accusative, cl = clitic, dat = dative, def = definite, dom = differential object marking, f = feminine, fut = future, ger = gerund, ind = indicative, inf = infinitive, io = indirect object, loc = locative, m = masculine, n = neuter, neg = negative, obl = oblique, pl = plural, pres = present, pst = past, se = pan-Romance pronominal element with reflexive, medio-passive and other related interpretations, sg = singular, sbjv = subjunctive.

Notes

| 1 | Abbreviations are at the end. | ||||||||||||

| 2 | In Romanian, one type of specific indefinite, namely the one illustrated in (6-c) is constructed from the indefinite root un- to which plural morphology and definiteness morphology must be added. | ||||||||||||

| 3 | A reviewer mentions that for them example (14-b) is not grammatical, while the other examples in (14) are acceptable. | ||||||||||||

| 4 | As in Romanian only marked objects allow accusative clitic doubling, another possibility to obtain an indefinite reading in the plural is to use just the bare noun. Compare (i) with (18-a):

| ||||||||||||

| 5 | As already mentioned in fn. 2, the Romanian indefinite stem ’un-’ needs to take the definite suffix in certain contexts. | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Among the exceptional prepositions that can show the definite suffix on unmodified nouns is the preposition cu ’with’.

| ||||||||||||

| 7 | Examples such as (19) appear to marginally be accepted even by a limited percentage of speakers of standard Romanian, especially in informal contexts. At least 5 of the 40 speakers in the Standard Romanian class tested here mentioned that such examples are not necessarily ungrammatical to them, although they are not perfect either. For other speakers (10 out of 40), acceptability depends on the noun class. A generalization grasped from these speakers is that nouns that are individualized, such as primar ‘mayor’ as opposed to coleg ‘colleague’ or femeie ‘woman’, can more easily accept DOM with the overt definite on unmodified nouns. Also note that, in standard Romanian, kinship nouns such as ‘mother’, ‘father’, etc., must preserve definiteness under DOM, even if unmodified, when they entail a kinship relation to the speaker. In this sense, they behave as highly individualized, unique nouns:

If these nouns appear bare under DOM, they are not interpreted as entailing a kinship relation to the speaker (or hearer), but instead refer to an entity that has the specific property, in this case, that of being a mother:

| ||||||||||||

| 8 | Note that in some dialects, such as the Serbian Romanian ones, DOM can more easily be used without the corresponding accusative clitic double. We leave this aspect aside here. | ||||||||||||

| 9 | The data are part of a larger questionnaire that asked the consultants to judge the grammaticality of various sentences illustrating DOM and its grammatical correlations (interactions with clitic doubling, with bare nominals, etc.). All sentences have been presented with an accompanying context, given the sensitivity of (Romanian) DOM to various pragmatic factors, besides the more syntactically oriented ones. | ||||||||||||

| 10 | As one of the reviewers note, the switch to past tense in the last three examples more easily favors a specific interpretation. These examples, however, are different from more ‘canonical’ DOM examples, where a specific interpretation requires the overt presence of a definite or indefinite determiner (interpreted as specific). The reviewer also wonders whether these examples might not illustrate types of small clauses. One problem with this assumption is that small clauses are subject to a restriction in Romanian which requires their argument to contain an overt determiner. | ||||||||||||

| 11 | For Romanian, a preference towards clitic doubling of DOM is mentioned by most consultants who accept these examples. As the interaction with clitic doubling would take us too far afield, we leave it aside here. | ||||||||||||