The Acquisition of French Determiners by Bilingual Children: A Prosodic Account

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Determiner Systems of French and Italian

| (1) | Il est professeur | ‘He is a teacher’ |

| He is teacher | ||

| (2) | avoir peur | ‘be afraid’ |

| have fright | ||

| (3) | Garçon ! Un café, s’il vous plaît | ‘Waiter! A coffee, please’ |

| Waiter! A coffee please | ||

| (4) | par hasard | ‘by chance’ |

| by chance |

| (5) | Luca beve acqua | ‘Luke drinks water’ |

| Luke drinks water | ||

| (6) | Luca vede gatti | ‘Luke sees cats’ (Kupisch 2007) |

| Luke sees cats |

3. Prosodic Status of Nouns in French (and Italian): Implications for Acquisition

3.1. Noun Length

| (7) | chapeau | [po] | ‘hat’ | (Demuth and Tremblay 2008, p. 125) |

| (8) | un médicament | [apamã] | ‘a medicine’ | (Wauquier and Yamaguchi 2013, p. 15) |

3.2. Lexical Stress

4. The Acquisition of Determiners in French

4.1. Monolingual French

4.2. Bilingual French

4.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses

5. Methodology

5.1. Participants

5.2. Analysis

| (9) | (je veux) pas [a] film | ‘I don’t want a movie’ | (Ju_fi, 2;1,18) |

| (I want) not [a] movie | |||

| (10) | [e] chien | ‘a dog’ | (Ju_fi, 2;2,7) |

| [e] dog |

6. Results

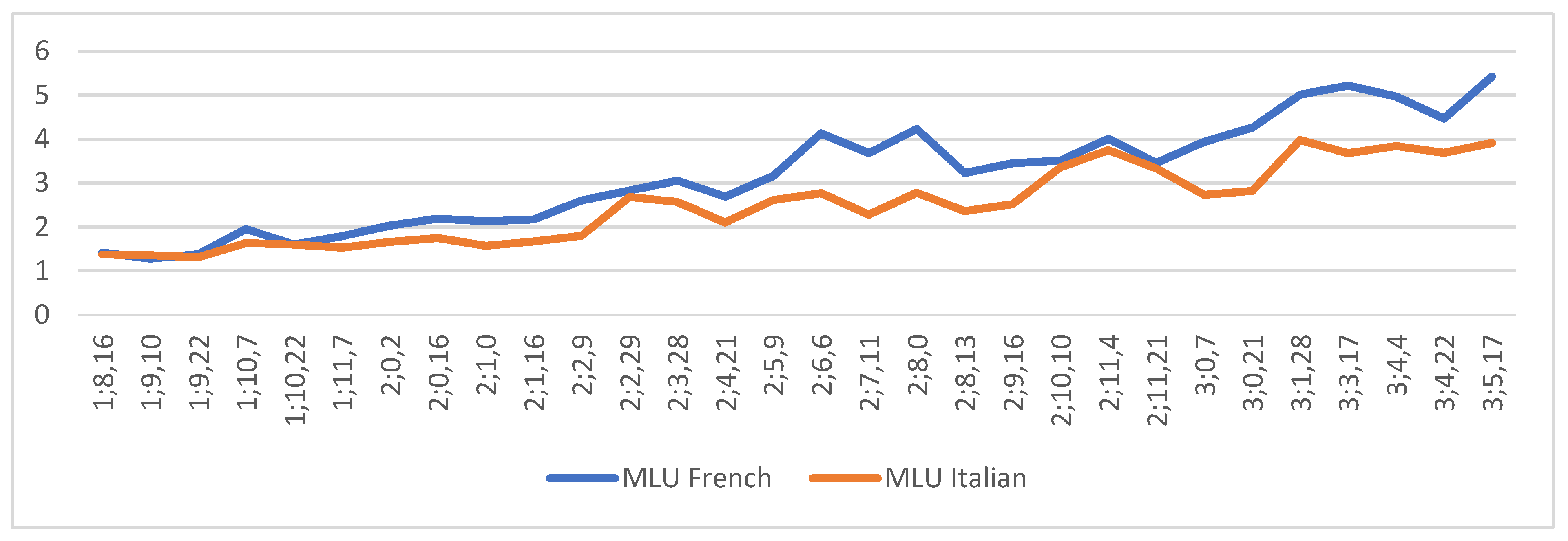

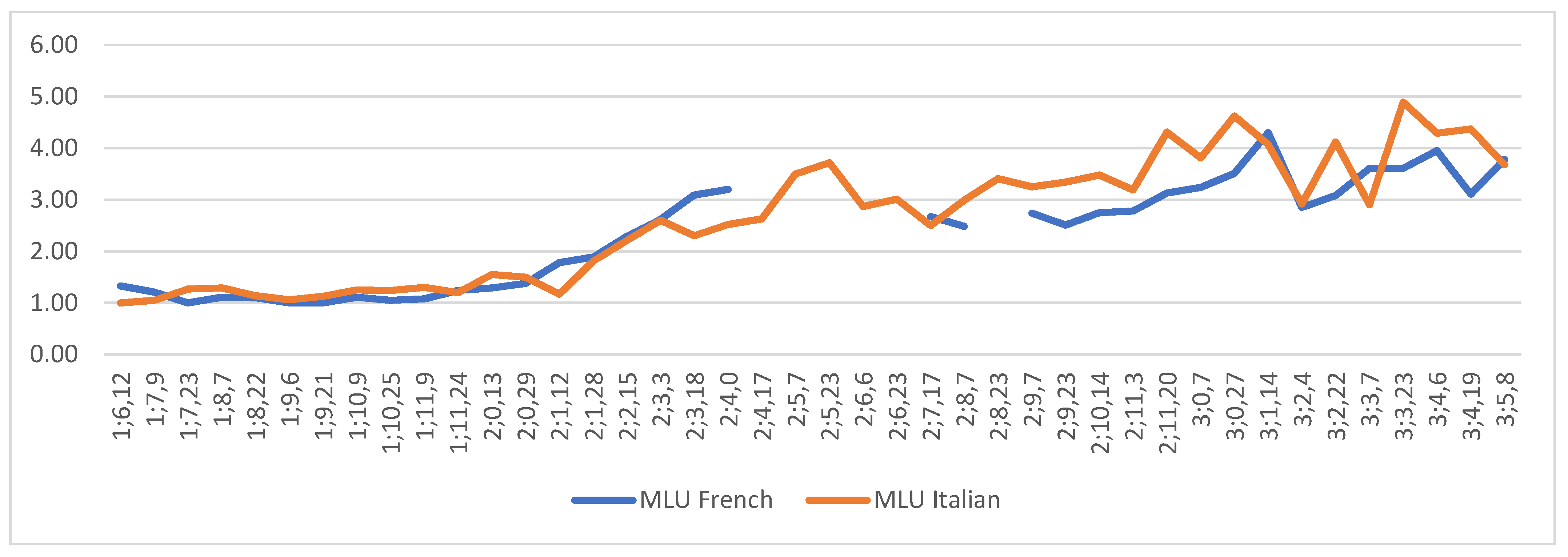

6.1. Acquisition Paths of Bilingual Children

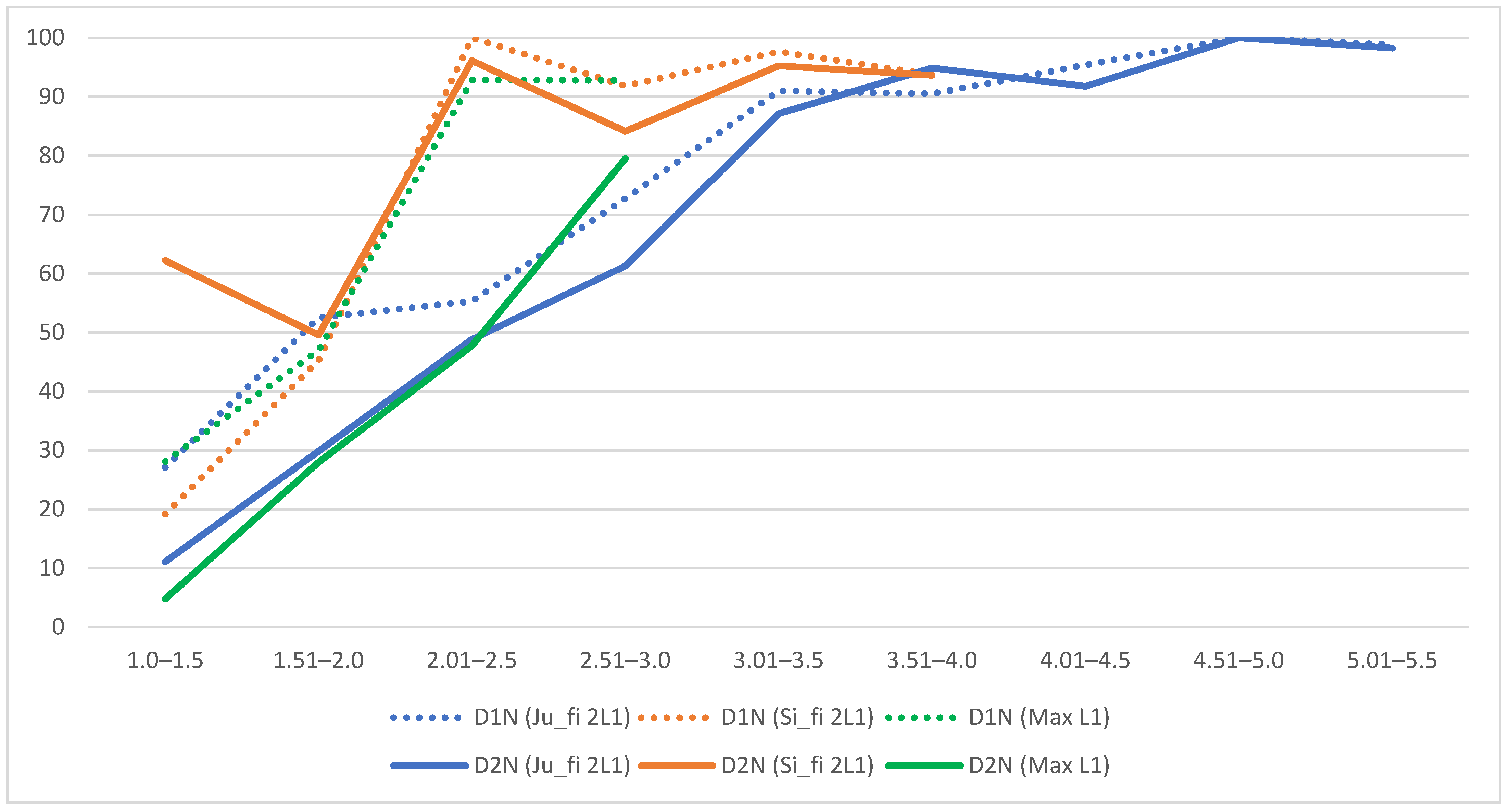

6.2. Bilinguals vs. Monolinguals

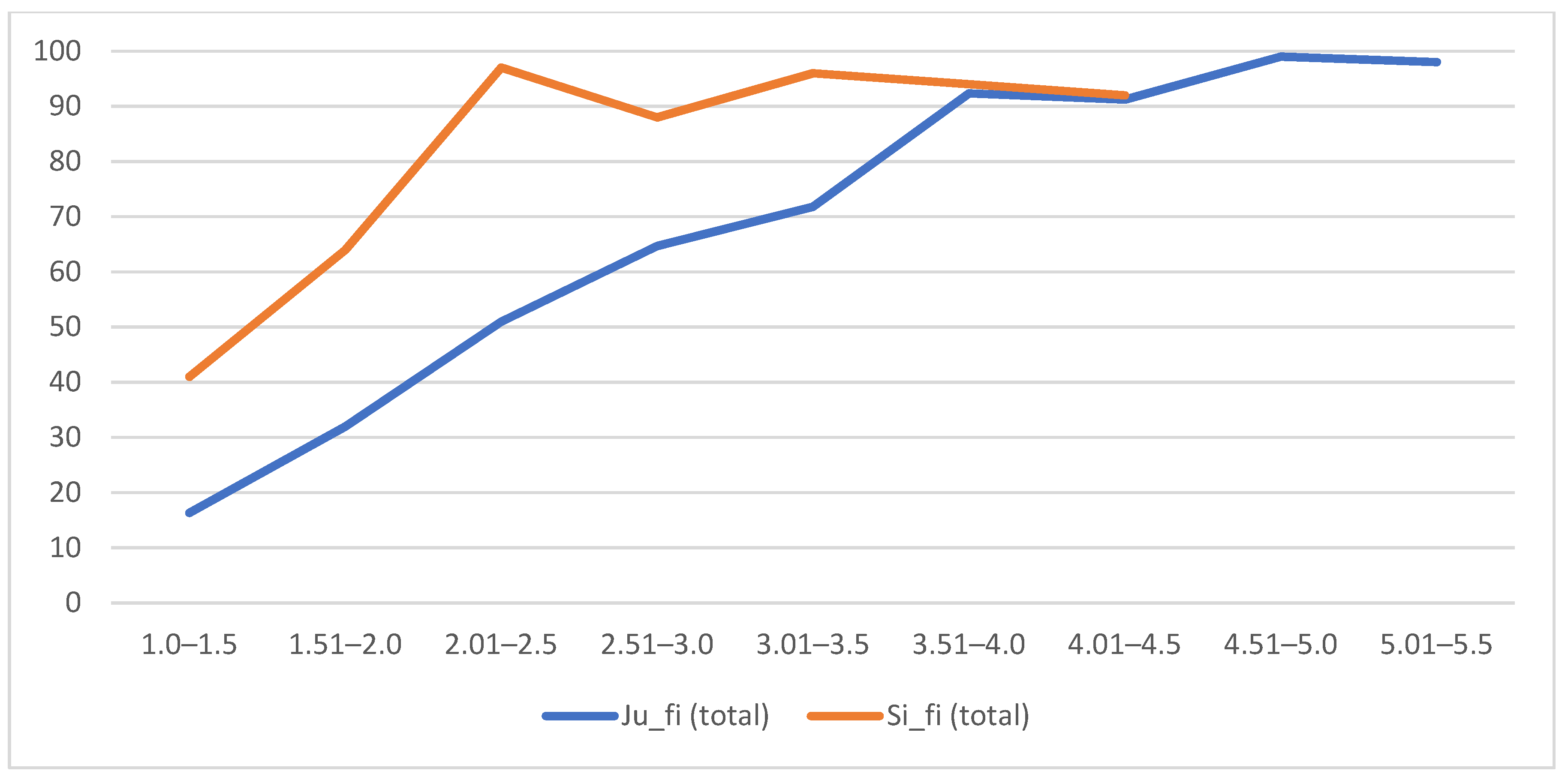

6.3. Language Dominance

7. Discussion and Conclusions

7.1. Interpretation of Results

7.2. Parametrization of Prosody

7.3. Outlook for Future Research

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Rec. | Age | MLU | NP | Target-Deviant Bare Nouns | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | 1N | % of 1N | 2N | % of 2N | 3+N | % of 3+N | ||||

| 1 | 1;8,16 | 1.42 | 37 | 33 | 89 | 3 | 100.0 | 30 | 88.2 | 0 | |

| 2 | 1;9,13 | 1.28 | 66 | 54 | 82 | 7 | 53.8 | 43 | 89.6 | 4 | 80.0 |

| 3 | 1;9,23 | 1.38 | 100 | 80 | 80 | 24 | 64.9 | 56 | 88.9 | 0 | |

| 4 | 1;10,7 | 1.95 | 112 | 58 | 52 | 18 | 41.9 | 34 | 55.7 | 6 | 75.0 |

| 5 | 1;10,25 | 1.60 | 42 | 33 | 79 | 1 | 33.3 | 29 | 80.6 | 3 | 100.0 |

| 6 | 1;11,10 | 1.79 | 124 | 91 | 73 | 35 | 67.3 | 46 | 74.2 | 10 | 100.0 |

| 7 | 1;11,27 | 2.03 | 80 | 34 | 43 | 8 | 26.7 | 24 | 55.8 | 2 | 28.6 |

| 8 | 2;0,16 | 2.19 | 112 | 55 | 49 | 19 | 55.9 | 29 | 44.6 | 7 | 53.8 |

| 9 | 2;1,0 | 2.13 | 56 | 35 | 63 | 14 | 66.7 | 20 | 60.6 | 1 | 50.0 |

| 10 | 2;1,18 | 2.17 | 91 | 37 | 41 | 8 | 29.6 | 24 | 43.6 | 5 | 55.6 |

| 11 | 2;2,7 | 2.60 | 98 | 40 | 41 | 9 | 32.1 | 29 | 43.9 | 2 | 50.0 |

| 12 | 2;2,29 | 2.83 | 69 | 30 | 43 | 16 | 45.7 | 13 | 43.3 | 1 | 25.0 |

| 13 | 2;4,0 | 3.05 | 75 | 9 | 12 | 2 | 11.1 | 5 | 11.4 | 2 | 15.4 |

| 14 | 2;4,20 | 2.69 | 78 | 17 | 22 | 1 | 4.0 | 13 | 28.9 | 3 | 37.5 |

| 15 | 2;5,10 | 3.16 | 53 | 11 | 21 | 4 | 14.3 | 7 | 28.0 | 0 | |

| 16 | 2;6,7 | 4.13 | 121 | 18 | 15 | 2 | 4.3 | 6 | 1.02 | 10 | 40.0 |

| 17 | 2;7,13 | 3.68 | 80 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 10.6 | 3 | 11.1 | 0 | |

| 18 | 2;8,1 | 4.23 | 161 | 16 | 10 | 5 | 7.7 | 7 | 9.0 | 4 | 22.2 |

| 19 | 2;8,13 | 3.23 | 165 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 3.6 | 8 | 8.3 | 0 | |

| 20 | 2;9,15 | 3.45 | 125 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 2.7 | 5 | 6.8 | 1 | 7.1 |

| 21 | 2;10,11 | 3.51 | 149 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 10.2 | 3 | 4.2 | 1 | 3.4 |

| 22 | 2;11,1 | 4.01 | 154 | 12 | 8 | 2 | 3.8 | 7 | 10.0 | 3 | 9.7 |

| 23 | 2;11,19 | 3.46 | 183 | 20 | 11 | 7 | 13.5 | 10 | 10.0 | 3 | 9.7 |

| 24 | 3;0,10 | 3.94 | 88 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 7.7 | 0 | 2 | 18.2 | |

| 25 | 3;0,21 | 4.26 | 122 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 1.9 | 4 | 7.3 | 2 | 15.4 |

| 26 | 3;1,26 | 5.01 | 186 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 1.1 | 1 | 3.4 |

| 27 | 3;3,19 | 5.22 | 164 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2.4 | 1 | 2.1 | |

| 28 | 3;4,2 | 4.97 | 134 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7.4 | ||

| 29 | 3;4,22 | 4.47 | 163 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 5.4 | 2 | 2.9 | 2 | 10.0 |

| 30 | 3;5,18 | 5.42 | 173 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2.1 | 1 | 1.8 | 1 | 4.8 |

| total | 3361 | 750 | 22.3 | 210 | 16.9 | 461 | 27.1 | 79 | 18.8 | ||

| Rec. | Age | MLU | NP | Target-Deviant Bare Nouns | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | 1N | % of 1N | 2N | % of 2N | 3+N | % of 3+N | ||||

| 1 | 1;6,12 | 1.33 | |||||||||

| 2 | 1;7,9 | 1.21 | |||||||||

| 3 | 1;7,23 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 4 | 1;8,7 | 1.11 | |||||||||

| 5 | 1;8,22 | 1.10 | |||||||||

| 6 | 1;9,6 | 1.00 | 11 | 6 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 100.0 | ||

| 7 | 1;9,21 | 1.00 | 6 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100.0 | ||

| 8 | 1;10,9 | 1.11 | |||||||||

| 9 | 1;10,25 | 1.05 | 14 | 8 | 57 | 7 | 100.0 | 1 | 14.3 | 0 | |

| 10 | 1;11,9 | 1.08 | 11 | 4 | 36 | 0 | 4 | 36.4 | 0 | ||

| 11 | 1;11,24 | 1.24 | 20 | 12 | 60 | 2 | 40.0 | 10 | 66.7 | 0 | |

| 12 | 2;0,13 | 1.29 | 13 | 13 | 100 | 9 | 100.0 | 4 | 100.0 | 0 | |

| 13 | 2;0,29 | 1.38 | 22 | 20 | 91 | 5 | 83.3 | 9 | 47.4 | 6 | 100.0 |

| 14 | 2;1,12 | 1.78 | 22 | 10 | 45 | 2 | 66.7 | 8 | 88.9 | 0 | |

| 15 | 2;1,28 | 1.89 | 46 | 13 | 28 | 6 | 42.9 | 3 | 11.5 | 4 | 66.7 |

| 16 | 2;2,15 | 2.29 | 86 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 5.5 | 2 | 18.2 | |

| 17 | 2;3,3 | 2.62 | 53 | 12 | 23 | 3 | 12.0 | 9 | 32.1 | 0 | |

| 18 | 2;3,18 | 3.09 | 41 | 0 | |||||||

| 19 | 2;4,0 | 3.20 | 39 | 5 | 14 | 1 | 4.2 | 4 | 28.6 | 0 | |

| 20 | 2;5,7 | 2.44 | 40 | 0 | |||||||

| 21 | 2,6,6 | 2.73 | 33 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 6.7 | 0 | ||

| 22 | 2;7,17 | 2.67 | 26 | 3 | 12 | 1 | 10.0 | 2 | 15,4 | 0 | |

| 23 | 2;8,7 | 2.48 | 31 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 6.3 | 0 | ||

| 24 | 2;9,7 | 2.74 | 20 | 3 | 15 | 2 | 14.3 | 1 | 16.7 | 0 | |

| 25 | 2;9,23 | 2.51 | 18 | 3 | 17 | 1 | 12.5 | 2 | 20.0 | 0 | |

| 26 | 2;10,14 | 2.75 | 26 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 16.7 | 0 | ||

| 27 | 2;11,3 | 2.78 | 31 | 4 | 13 | 1 | 16.7 | 1 | 6.3 | 2 | 22.2 |

| 28 | 2;11,20 | 3.13 | 35 | 0 | |||||||

| 29 | 3;0,7 | 3.24 | 25 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20.0 | ||

| 30 | 3;0,27 | 3.51 | 50 | 5 | 10 | 2 | 11.8 | 3 | 10.0 | 0 | |

| 31 | 3;1,14 | 4.30 | 61 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 8.0 | 3 | 9.4 | 0 | |

| 32 | 3,2,4 | 2.85 | 84 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 13.2 | 0 | ||

| 33 | 3;2,22 | 3.08 | 35 | 0 | |||||||

| 34 | 3;3,7 | 3.61 | 43 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 5.3 | 1 | 6.7 | 1 | 11.1 |

| 35 | 3;3,23 | 3.61 | 35 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 25.0 | ||

| 36 | 3;4,6 | 3.95 | 84 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 8.6 | 1 | 8.3 | |

| 37 | 3;4,19 | 3.11 | 27 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 10.0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 38 | 3;5,8 | 3.78 | 68 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 14.3 | 2 | 6.7 | 0 | |

| total | 1156 | 155 | 13.4 | 49 | 10.7 | 81 | 14.1 | 25 | 21.0 | ||

| 1 | |

| 2 | Note that inanimate nouns have also been argued to have uninterpretable features (e.g., Pesetsky and Torrego 2007). Additionally, there are languages with agreement but without N to D movement. |

| 3 | A trochaic bias has been described cross-linguistically (e.g., Jusczyk et al. 1993; Boyle and Gerken 1997 on English; Bijeljac-Babic et al. 2016 on German), even though it does not seem to be empirically grounded across the board (cf. Stahnke 2022 for an overview of Romance languages). Monolingual French children do not perceive rhythmic differences at a very young age but are ‘stress deaf’, i.e., they do not have any preference for either trochaic or iambic structures (Bijeljac-Babic et al. 2016). Their first productions are iambic, reflecting properties of the input (Scullen 1997; Demuth and Johnson 2003; Tremblay 2006). |

| 4 | years;months(,days). |

| 5 | mean length of utterance. |

| 6 | Interestingly, the target-like reanalysis of numerals as indefinite D seems to trigger the production of gender and number features from ca. 2;0/2;4 onwards (MLU around 2.0), which coincide with a productive use of articles and complex DPs (e.g., D + A + N; Müller 1994, pp. 63–64). |

| 7 | Of course, there may also be negative influence from French on Italian if it is accepted that cross-linguistic influence is not only positive (cf. e.g., Flynn et al. 2004 on the concept of cumulative enhancement in second and third language acquisition). In the same vein, the massive syntactic evidence of realized D in French may also positively influence the acquisition of Italian D. Since this paper analyzes French, these options are not pursued in the study. |

| 8 | The data stem from the research project “Die Architektur der frühkindlichen bilingualen Sprachfähigkeit. Italienisch-Deutsch und Französisch-Deutsch in Italien, Deutschland und Frankreich im Vergleich” headed by Natascha Müller and financed by a grant of the German Research Foundation (project number 5452914). In this project, the role of the (Romance or German) majority language was assessed in bilingual language acquisition. |

| 9 | ‘Stability’ indicates that in the following recordings production rates do not drop below 50% and 90%, respectively (cf. Section 5.2 for details). |

| 10 | For all other pairings, numbers are too low to conduct statistical analyses. |

References

- Abney, Steven P. 1987. The English Noun Phrase in Its Sentential Aspect. Ph.D. thesis, MIT, Massachussetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. Available online: http://www.ai.mit.edu/projects/dm/theses/abney87.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Andreassen, Helene N., and Julien Eychenne. 2013. The French foot revisited. Language Sciences 39: 126–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Arnaus Gil, Laia, and Natascha Müller. 2019. Frühkindlicher Trilinguismus. Französisch, Spanisch, Deutsch. Tübingen: Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Bassano, Dominique. 1998. Sémantique et syntaxe dans l’acquisition des classes de mots: L’exemple des noms et des verbes en français. Langue française 118: 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassano, Dominique, Isabelle Maillochon, and Sylvain Mottet. 2008. Noun grammaticalization and determiner use in French children’s speech: A gradual development with prosodic and lexical influences. Journal of Child Language 35: 403–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belletti, Adriana, and Maria Teresa Guasti. 2015. The Acquisition of Italian. Morphosyntax and Its Interfaces in Different Modes of Acquisition. Amsterdam: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Berkele, Gisela. 1983. Die Entwicklung des Ausdrucks von Objektreferenz am Beispiel von Determinanten. Eine empirische Untersuchung zum Spracherwerb bilingualer Kinder Französisch/Deutsch. State Exam thesis, University of Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardini, Petra. 2003. Child and adult acquisition of word order in the Italian DP. In Invulnerable Domains in Multilingualism. Edited by Natascha Müller. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 41–82. [Google Scholar]

- Berstein, D. 1993. Topics in the Syntax of Nominal Structure across Romance. Ph.D. thesis, CUNY, University Microfilms International, New York, NY, USA. Available online: http://www.ai.mit.edu/projects/dm/theses/more/bernstein93.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Bijeljac-Babic, Ranka, Barbara Höhle, and Thierry Nazzi. 2016. Early prosodic acquisition in bilingual infants: The case of the perceptual trochaic bias. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 1–8. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00210/full (accessed on 15 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Bottari, Piero, Paola Cipriani, and Anna Maria Chilosi. 1993. Protosyntactic devices in the acquisition of Italian free morphology. Language Acquisition 34: 327–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, Mary K., and LouAnn Gerken. 1997. The influence of lexical familiarity on children’s function morpheme omissions. Journal of Memory and Language 36: 117–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chierchia, Gennaro. 1998. Reference to kinds across langues. Natural Language Semantics 6: 339–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chierchia, Gennaro, Maria Teresa Guasti, and Andrea Gualmini. 2001. Nouns and Articles in Child Grammar and the Syntac/semantics Map. College Park: University of Milan, University of Siena and University of Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, Eve V. 1986. The acquisition of Romance, with special reference to French. In The Cross-Linguistic Study of Language Acquisition. Edited by Dan Isaac Slobin. Hillsdale: Erlbaum, pp. 687–782. [Google Scholar]

- Demuth, Katherine, and Mark Johnson. 2003. Truncation to submiminal words in early French. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 48: 211–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuth, Katherine, and Annie Tremblay. 2008. Prosodically-conditioned variability in children’s production of French determiners. Journal of Child Language 35: 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuth, Katherine, Meghan Patrolia, Jae Yung Song, and Matthew Masapollo. 2012. The development of articles in children’s early Spanish: Prosodic interactions between lexical and grammatical form. First Language 32: 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresher, B. Elan, and Jonathan D. Kaye. 1990. A computational learning model for metrical phonology. Cognition 34: 137–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Féry, Caroline. 2001. Focus and phrasing in French. In Audiatur vox Sapientiae: A Festschrift for Arnim von Stechow. Edited by Caroline Féry and Wolfgang Sternefeld. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, pp. 153–81. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn, Suzanne, Claire Foley, and Inna Vinnitskaya. 2004. The cumulative-enhancement model for language acquisition: Comparing adults’ and children’s patterns of development in first, second and third language acquisition of relative clauses. The International Journal of Multilingualism 1: 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granfeldt, Jonas. 2000. The acquisition of the determiner phrase in bilingual and second language French. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 33: 263–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granfeldt, Jonas. 2003. L’acquisition des Catégories Fonctionnelles: Etude Comparative du Développement du DP Français Chez des Enfants et des Apprenants Adultes. Ph.D. thesis, Department of Romance Languages, Lund University, Lund, Sweden. Available online: https://lucris.lub.lu.se/ws/portalfiles/portal/4748375/837916.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Guasti, Maria Teresa, Anna Gavarró, Joke De Lange, and Claudia Caprin. 2008. Article omission across child languages. Language Acquisition 152: 89–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser-Grüdl, Nicole, Lastenia Arencibia Guerra, Franziska Witzmann, Estelle Leray, and Natascha Müller. 2010. Cross-linguistic influence in bilingual children: Can input frequency account for it? Lingua 12011: 2630–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Bruce. 1995. Metrical Stress Theory. Principles and Case Studies. London: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heinen, Sabine, and Helga Kadow. 1990. The acquisition of French by monolingual children. A review of the literature. In Two First Languages: Early Grammatical Development in Bilingual Children. Edited by Jürgen M. Meisel. Dordrecht: Foris, pp. 47–71. [Google Scholar]

- Hulk, Aafke. 2004. The acquisition of the French DP in a bilingual context. In The Acquisition of French in Different Contexts: Focus on Functional Categories. Edited by Philippe Prévost and Johanne Paradis. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 243–74. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, Sun-Ah, and Cécile Fougeron. 2000. A phonological model of French intonation. In Intonation: Analysis, Modeling and Technology. Edited by Antonis Botinis. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 209–42. [Google Scholar]

- Jusczyk, Peter W., Anne Cutler, and Nancy J. Redanz. 1993. Preference for the predominant stress patterns of English words. Child Development 64: 675–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehoe, Margaret. 2002. Developing vowel systems as a window to bilingual phonology. The International Journal of Bilingualism 6: 315–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupisch, Tanja. 2003. The DP, a vulnerable domain? Evidence from the acquisition of French. In InVulnerable Domains in Language Multilingualism. Edited by Natascha Müller. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kupisch, Tanja. 2004. On the relation between input frequency and acquisition patterns from a Crosslinguistic perspective. In Proceedings of GALA 2003. Edited by Jacqueline van Kampen and Sergio Baauw. Utrecht: LOT, pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar]

- Kupisch, Tanja. 2006. The Acquisition of Determiners in Bilingual German-Italian and German-French Children. München: Lincom Europa. [Google Scholar]

- Kupisch, Tanja. 2007. Testing the effects of frequency on the rate of learning. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Input Frequencies in Acquisition. Edited by Insa Gülzow and Natalia Gagarina. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 83–113. [Google Scholar]

- Kupisch, Tanja. 2008. Dominance, mixing and cross-linguistic influence. On their relation in bilingual development. In First Language Acquisition of Morphology and Syntax. Perspectives Across Languages and Learners. Edited by Pedro Guijarro-Fuentes, María Pilar Larrañaga and John Clibbens. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 209–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kupisch, Tanja, and Petra Bernardini. 2007. Determiner use in Italian Swedish and Italian German children: Do Swedish and German represent the same parameter setting? NORDLYD: University of Tromsø Working Papers on Language and Linguistics 344: 209–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleó, Conxita. 1998. Proto-articles in the acquisition of Spanish. In Models of Inflection. Edited by Ray Fabri, Albert Ortmann and Teresa Parodi. Tübingen: Niemeyer, pp. 175–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lleó, Conxita. 2001. The interface of phonology and syntax: The emergence of the article in the early acquisition of Spanish and German. In Approaches to Bootstrapping: Phonological, Syntactic and Neurophysiological Aspects of Early Language Acquisition. Edited by Jürgen Weissenborn and Barbara Höhle. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lleó, Conxita. 2002. The role of markedness in the acquisition of complex prosodic structures by German-Spanish bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingualism 6: 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleó, Conxita. 2006. The acquisition of prosodic word structures in Spanish by monolingual and Spanish-German bilingual children. Language and Speech 49: 205–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleó, Conxita. 2016. Acquiring multilingual phonologies 2L1, L2 and L3: Are the difficulties in the interfaces? In Manual of Grammatical Interfaces in Romance. Edited by Christoph Gabriel and Susann Fischer. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 519–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lleó, Conxita, and Katherine Demuth. 1999. Prosodic constraints on the emergence of grammatical morphemes: Crosslinguistic evidence from Germanic and Romance languages. In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Annabel Greenhill, Heather Littlefield and Cheryl Tano. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 407–18. [Google Scholar]

- Longobardi, Giuseppe. 1994. Reference and proper names. A theory of N-movement in syntax and logical form. Linguistic Inquiry 254: 609–65. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, Brian. 2000. The Childes Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk: The Database. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mancini, Federico, and Miriam Voghera. 1994. Lunghezza, tipi di sillabe e accento in italiano. Archivo Glottologico Italiano 79: 51–77. [Google Scholar]

- Meisel, Jürgen M., ed. 1990. Two First Languages. Early Grammatical Development in Bilingual Children. Dordrecht: Foris. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Natascha. 1994. Gender and number agreement within DP. In Bilingual First Language Acquisition. French and German Grammatical Development. Edited by Jürgen M. Meisel. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 53–88. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Natascha, and Aafke Hulk. 2001. Crosslinguistic influence in bilingual language acquisition: Italian and French as recipient languages. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 41: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Natascha, Laia Arnaus Gil, Nadine Eichler, Jasmin Geveler, Malin Hager, Veronika Jansen, Marisa Patuto, Valentina Repetto, and Anika Schmeißer. 2015. Code-Switching: Französisch, Italienisch, Spanisch. Eine Einführung. Tübingen: Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Özçelik, Öner. 2017. The foot is not an obligatory constituent of the prosodic hierarchy: “Stress” in Turkish, French and child English. The Linguistic Review 341: 157–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Johanne. 2001. Do bilingual two-year-olds have separate phonological systems? International Journal of Bilingualism 5: 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Johanne, and Fred Genesee. 1996. Syntactic acquisition in bilingual children. Autonomous or interdependent? Studies in Second Language Acquisition 18: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, Johanne, and Fred Genesee. 1997. On continuity and the emergence of functional categories in bilingual first-language Acquisition. Language Acquisition 62: 91–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesetsky, David, and Esther Torrego. 2007. The syntax of valuation and the interpretability of features. In Phrasal and Clausal Architecture: Syntactic Derivation and Interpretation. Edited by Simin Karimi, Vida Samiian and Wendy K. Wilkins. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 262–94. [Google Scholar]

- Post, Brechtje. 2000. Tonal and Phrasal Structures in French Intonation. The Hague: Holland Academic Graphics. [Google Scholar]

- Prévost, Philippe. 2009. The Acquisition of French: The Development of Inflectional Morphology and Syntax in L1 Acquisition, Bilingualism, and L2 Acquisition. Amsterdam: Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Pupier, Paul. 1982. L’acquisition des déterminants français chez les petits enfants français-anglais. In L’acquisition Simultanée du Français et le L’anglais chez des Petits Enfants de Montréal. Edited by Paul Pupier. Québec: Édition officielle du Québec, pp. 173–214. [Google Scholar]

- Romaine, Suzanne. 1995. Bilingualism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, Petra, and Angela Grimm. 2019. The age factor revisited: Timing in acquisition interacts with age of onset in bilingual acquisition. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1–18. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02732/full (accessed on 15 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Scullen, Mary Ellen. 1997. French Prosodic Morphology: A Unified Account. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club. [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1978. The French foot: On the status of the ‘mute’ e. Studies in French Linguistics 1: 141–50. [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, Elisabeth O. 1984. Phonology and Syntax: The Relation between Sound and Structure. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stahnke, Johanna. 2019. Cross-linguistic prosodic influence in bilingual language acquisition. In Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. Edited by Sasha Calhoun, Paola Escudero, Marija Tabain and Paul Warren. Melbourne: Australia, pp. 3403–3407. [Google Scholar]

- Stahnke, Johanna. 2022. First language acquisition of Romance phonology. In Manual of Romance phonetics and phonology. Edited by Christoph Gabriel, Randall Gess and Trudel Meisenburg. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 375–406. [Google Scholar]

- Stahnke, Johanna, Laia Arnaus Gil, and Natascha Müller. 2021. French as a heritage language in Germany. Languages 6: 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, Annie. 2005. On the status of determiner fillers in early French: What the child knows. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development. Edited by Alejna Brugos, Manuella R. Clark-Cotton and Seungwan Ha. Somerville: Cascadilla Press, pp. 604–15. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, Annie. 2006. Prosodic constraints on the production of grammatical morphemes in French: The case of determiners. University of Connecticut Occasional Papers in Linguistics 4: 377–88. [Google Scholar]

- Valois, Daniel. 1991. The Internal Syntax of DP. Ph.D. thesis, Department of Linguistics, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA. Available online: https://linguistics.ucla.edu/general/Dissertations/Valois.1991.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2022).

- Valois, Daniel. 1997. On French DPs. La revue Canadienne de Linguistique 41: 349–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Velde, Marlies. 2004. L’acquisition des articles définis en L1. Étude comparative entre le français et le néerlandais. Acquisition et Interaction en Langue Étrangère 21: 9–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oostendorp, Marc. 2015. Parameters in phonological analysis: Stress. In Contemporary Linguistic Parameters. Edited by Antonio Fabregas, Jaume Mateu and Michael Putnam. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 234–58. [Google Scholar]

- Veneziano, Edy, and Hermine Sinclair. 2000. The changing status of ‘filler syllables’ on the way to grammatical morphemes. Journal of Child Language 27: 461–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wauquier, Sophie, and Naomi Yamaguchi. 2013. Templates in French. In The Emergence of Phonology: Whole-Word Approaches and Cross-Linguistic Evidence. Edited by Marilyn M. Vihman and Tamar Keren-Portnoy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 317–42. [Google Scholar]

| French | Italian | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| indefinite | ||||

| singular | plural | singular | plural | |

| masculine | un [œ̃(n)] | des [de(z)] | un [un] uno [’uno] | dei [dei] degli [’deʎi] |

| feminine | une [yn] | un’, una [’un(a)] | delle [’dele] | |

| definite | ||||

| masculine | le [l(ə)] | les [le(z)] | il [il] l(o) [l(o)] | i [i] gli [ʎi] |

| feminine | la [l(a)] | l(a) [l(a)] | le [le] | |

| French (Demuth and Johnson 2003) | Italian (Guasti et al. 2008) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| monosyllabic | 45% chat ‘cat’ | 3% re ‘king’ | |

| disyllabic | 47% maison ‘house’ | 59% strada ’street’ | |

| trisyllabic | 7% animal ‘animal’ | 8% | 38% colore ‘color’ |

| other | 1% | ||

| First Appearance: Age (MLU) | Stability: Age (MLU) | |

|---|---|---|

| 50% D1N | 1;1 (1.1) | 2;0 (1.9) |

| 90% D1N | 2;1 (2.2) | 2;2 (2.6) |

| 50% D2N | 2;1 (2.4) | |

| 90% D2N | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stahnke, J. The Acquisition of French Determiners by Bilingual Children: A Prosodic Account. Languages 2022, 7, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030200

Stahnke J. The Acquisition of French Determiners by Bilingual Children: A Prosodic Account. Languages. 2022; 7(3):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030200

Chicago/Turabian StyleStahnke, Johanna. 2022. "The Acquisition of French Determiners by Bilingual Children: A Prosodic Account" Languages 7, no. 3: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030200

APA StyleStahnke, J. (2022). The Acquisition of French Determiners by Bilingual Children: A Prosodic Account. Languages, 7(3), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7030200