Abstract

Azov Greek is a Modern Greek dialect currently spoken in several villages in the area of Mariupol (Eastern Ukraine). Recent studies in Modern Greek dialectology clearly demonstrate that all Modern Greek dialects (even so specific as Tsakonian) in some period (or periods) of their history were deeply influenced by other dialects or languages and the traces of this influence can be found on various linguistic levels. Azov Greek is no exception here. This contribution intends not only to specify languages involved in language contact with Azov Greek and to analyze the most remarkable features but also to reconstruct a timeline of these contacts. The analysis is based on the field research data collected in Greek speaking villages around Mariupol between 2001 and 2019 and considers folklore and literary texts in Azov Greek.

1. Introduction

Language contacts were an important factor for development of Greek throughout its long history. Already in Ancient Greek one can easily find all types of contact situations relevant for later stages as well:

- contacts with other languages (Christidis 2007, pp. 721–850);

- contacts between dialects/vernaculars and literary standard(s) which are typical for the languages with elaborated literary tradition;

- contacts between various dialects (e.g., powerful influence of Ionic on Attic, cf. Panayotou 2007, p. 413).

Analysis of contact phenomena has recently become an indispensable element of the studies in Modern Greek dialectology, especially for Modern Greek dialects outside mainland Greece, i.e., in the Asia Minor (Ralli 2019b), in South Italy (Ledgeway 2013), in various parts of Albania like Dropull (Kisilier et al. 2016) and Himara (Joseph et al. 2019), in Great Britain (Karatsareas 2021), Canada (Ralli 2019a), etc. However, Modern Greek dialects in the post-Soviet states are extremely rarely regarded from the point of view of contact linguistics.

This contribution is devoted to the Azov Greek still spoken in 17 villages around Mariupol (Eastern Ukraine). Chronologically, the studies of this dialect can be divided into four phases:

- Pre-Soviet (from mid-19th century till the Soviet revolution of 1917);

- Early Soviet (from late 1920s till 1938);

- Late Soviet (late 1950s–1980s);

- Post-Soviet (from 1990).

The Pre-Soviet period started with the activities of local ethnographer and historian Teoctist Khartakhay (1836–1880), who compiled the first dictionary published by Tatiana Chernysheva (1959). In 1874, Russian philologist Victor Grigorovich visited several Greek speaking villages in the Azov Sea region where he collected dialectal words, mentioned several linguistic peculiarities and suggested that Azov Greek should be divided in two subdialects—Northern with negation ðen and Southern with negation k or tʃ (Grigorovich 1874, pp. 6–8, I–III). His data was repeated by Otto Blau (1874) and later was used by Paul Kretschmer (1905, p. 18) in his discussion of the origin of Azov Greek (see also Section 4.4). Along with a rather superficial description, Grigorovich noticed that Azov Greek had signs of long coexistence with Russian (Grigorovich 1874, p. 6).

The first detailed linguistic studies of Azov Greek date back to the 1930s when the USSR launched a new policy aimed to support linguistic minorities and to create literatures in minor languages and local dialects. Thus, the Greeks of the USSR got their alphabet based on Demotic1. This alphabet was used by Azov and Pontic Greeks and reflected phonetic peculiarities in both dialects (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Soviet Greek alphabet.

Unlike Demotic, new orthography had only one way to express /e/, /i/ and /o/, used <υ> for /u/, <ζ> for /z/ and /ʒ/, <ςς> for /ʃ/ and <τςς> for /tʃ/. Creation of new orthography would have been impossible without a thorough field research in Greek speaking villages. Unfortunately, the data collected at that time is unavailable now and we have to be content with few publications (Sokolov 1930, 1932; Spiridonov 1930; Sergievskiy 1934). While Sokolov and Spiridonov mostly discuss history and subdialectal subdivision of Azov Greek, Sergievskiy provides a description of phonetics and morphology in various local variants of the dialect. Language contacts were not considered as long as the scholars were looking for a “pure language” free of any borrowings (cf. Sokolov 1930, p. 63).

In 1937, the state policy changed and since then all attempts to develop minor languages and local dialects were regarded as anti-Soviet. This policy change led to the death of many local activists, poets and writers and nobody dared to resume Azov Greek studies until 1960s when Andrey Beletskiy, Professor from Kyiv, and his student and wife Tatiana Chernysheva, organized several expeditions to the Azov Sea region. Based on the collected data, they provided a detailed description of the dialect in a series of articles (the most important are Chernysheva 1958; Beletskiy 1969) and were first to pay attention to the adoption of Tatar words in Azov Greek (Beletskiy 1964). Beletskiy’s activities had a tremendous influence on the local community: on the one hand, the scholar supported the poets who were writing in Azov Greek—he even created a new alphabet based on Cyrillic (see Kisilier 2009a, pp. 14–15 for more information about this alphabet; it was first officially used in Shapurmas 1986); on the other hand, local enthusiasts were so much inspired that they tried to carry out their own research. For example, Aleko Diamantopoulo-Rionis, a former student of Ivan Sokolov, started to compile a dictionary in 1966. It was published only 40 years later (Diamantopoulo-Rionis et al. 2006) and currently is the best and the largest dictionary of Azov Greek.

In the mid-1970s, Ekaterina Zhuravliova (better known as Pappou-Zouravliova) launched a series of expeditions to Novaya Karakuba and Maloyanisol’. At first, her attention was mainly focused on phonetic peculiarities (Zhuravliova 1980). However, when she moved to Greece, she managed to reveal Azov Greek to the international academic community (cf. Pappou-Zouravliova 1995, 1998). Thanks to Ekaterina Pappou-Zouravliova, specialists in Modern Greek linguistics and dialectology not just started to consider new data (cf. Drettas 1999, p. 92) but even decided to perform complex research of Azov Greek (Symeonidis and Tompaidis 1999). This new period is also marked by the growth of interest to possible contact phenomena (Pappou-Zouravliova 2002), code-switching. (Lisitskaya 2009) and general multilingual situation in the region from sociolinguistic point of view (Christou 2007). The aforementioned papers clearly demonstrate that contact-oriented research of Azov Greek may reveal and explain multiple peculiarities of the dialect both in synchronic and diachronic perspectives. This contribution intends to make at least three further steps:

- to specify languages and dialects that may be involved into contacts with Azov Greek and to connect them with specific features;

- to reconstruct an approximate timeline of these contacts;

- to demonstrate that along with oral communication there could be other domains of linguistic interaction, namely—with the language of Azov Greek folklore and literature.

These objectives influence the structure of the article: after an overview of the data used for the research (Section 2), I give a brief historical outline of Azov Greeks in Section 3 in order to detect possible connections with other nations and other Greek speaking communities. Section 4 provides a necessary linguistic description of the dialect and sociolinguistic situation in the region. It also discusses the place of Azov Greek among other Modern Greek dialects. In Section 5, I analyze all known contact situations and suggest which linguistic peculiarities can be identified as contact-induced.

2. Materials and Sources

Unfortunately, the archives of my predecessors are unavailable to me: they are either lost (like the materials of Sokolov which disappeared after his arrest in December 1933), or unpublished (cf. Chernykhin et al. 2014). Accordingly, the most data for diachronic analysis are to be found either in the publications mentioned before or in the collections of folklore texts (like Khadzhinov 1979; Kir’akov 1989, 1991, 1993a, 1993b, 1994; Ashla 1999, and others) and in Azov Greek literature2.

For a historical linguist, it may be very risky to analyze folklore and literary texts—they have a very special language with its own rules and restrictions. For example, in the verses by the Cretan poet Stephanos Sakhlikes (14th century), there are two sets of verb flexions (archaic and modern) and the choice between them depends on the hemistich where the verb is used (Fedchenko 2010, pp. 267, 272–73). Still, folklore and literature often reflect contact phenomena and facilitate approximate dating of the past contacts. Thus, in Sakhlikes one can easily find multiple lexical borrowings from Venetian (Fedchenko 2010, p. 271) that demonstrate that Crete in the 14th century already had a strong interaction between Greek and Italian at least in urban life.

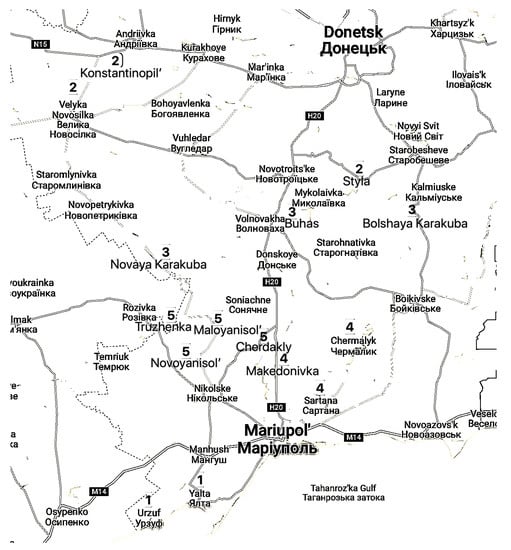

The main data for the analysis was collected by my colleagues from Saint Petersburg University (Elena Perekhvalskaya, Valentin Vydrin, Alexander Novik), 40 students and myself in 2001–2006. Due to a large number of participants, we were able to divide into several groups and to cover almost all Greek villages around Mariupol (see Figure 2). Special attention was paid to Urzuf, Yalta, Sartana, Novaya Karakuba, Buhas and Maloyanisol’. During the field research we managed to interview 139 speakers of different subdialects ageing from 6 to 97. Each researcher was responsible for a specific subject in phonetics, morphology, syntax, sociolinguistics, folklore or ethnography. Primarily, the data were collected by means of various questionnaires specially prepared for this project. Soon it became evident that this method is appropriate not for all speakers and narratives are much more reliable. We have recorded about 300 h of interviews and narratives3. The most important results of these expeditions are published in (Kisilier 2009a; Baranova 2010).

Social networks made it possible to get some important material through online communication with dialect experts when it was no more possible to organize an expedition. For this research, I also used dictionaries compiled by local enthusiasts (Animitsa et al. 2003; Diamantopoulo-Rionis et al. 2006).

3. History

Greek settlers came to the Azov steppe from the Crimea in the late 1770s (the first 7 villages were founded in 1779). Unfortunately, the information about Greeks in the Crimea before the peninsula became a protectorate of the Russian Empire in 1774 is scarce and not very reliable. However, we definitely know that

- Greeks first appeared in the Crimea during the colonization in the 8th century BC.

- As we can see from folklore (Akritic songs, see Section 5.1.1) and some linguistic features (clitic doubling, see Section 4.3.2) there were several waves of immigration in the Middle Ages. Supposedly at that time some Crimean Greeks got ethnonym Rúmej[s] < Ῥωμαῖος /roméos/ ‘citizen of the Byzantine Empire’ and their language/dialect was called Ruméjka.

- In the mid-13th century, the Crimea was annexed by the Golden Horde, and in the mid-15th century, it became the Crimean Khanate with the official Crimean Tatar language. As a result, urban Greeks switched from their native language to Crimean Tatar and their ethnonym changed to Urum (Turkic variant of Rúmej)4. Greek-speaking Rumejs were villagers and most of them were bilingual because Crimean Tatar became the official language of administration and trade.

- Rumejs were not the only Greek-speaking community in the Crimea. Since the 15th century, there was mass displacement of Trebizond Greeks to the Crimea (Sokolov 1932, p. 313), and in the early 1770s, after the defeat of the Orlov revolt, up to 4000 Peloponnesian Greeks fled to the Crimea (Christou 2007, p. 41).

The migration from the Crimea started in 1778 and involved 31,386 Greeks, both Rumejs and Urums (Animitsa and Kisilier 2009, p. 26). According to the official version supported by Azov Greek oral tradition, it was a voluntary initiative of the Crimean Greek Orthodox community who sent a request to the Russian Empress Catherine the Great (1729–1796). However, for the Russian Empire it was a very important project. Its goal was to populate the Azov steppe, which was frequently used by Tatars as a bridgehead for their devastating raids to Southern Russia. Some time later (in 1820s) there also appeared several German and Albanian settlements and one village (Anadol) of Pontic Greeks from the Asia Minor.

Probably, most migrants were the youngest members of the families and could not hope to inherit any property from their parents. Like in the Crimea, Rumejs and Urums did not settle together: Urums, probably from Bakhchysarai (Christou 2007, p. 68), founded the city of Mariupol, which became local cultural, religious and administrative center. Unlike Urums, Rumejs preferred rural life. Both communities often used familiar Crimean toponyms for their new settlements: Yalta, Urzuf and Eski Qırım (=Staryi Krym ‘Old Crimea’), etc. In the Cis-Azov region, the Urum language (subdialect of Crimean Tatar) retained its significance and in Mariupol Rumejs had to speak Urum as well. Before the 1870s, there was almost no impact of Russian and it was used only by local intellectuals. The situation started gradually to change when the Russian government decided to start obligatory military service for Azov Greeks (since 1874) and opened male and female gymnasia in Mariupol in 1875–1876 (Animitsa and Kisilier 2009, p. 34).

Soon after the Soviet revolution of 1917, the government decided to support local minorities. Thus, Greeks of the USSR, including Azov Greeks, got their first alphabet (see Table 1), Greek schools and Greek literature. Between 1924 and 1937 several hundreds of Greek books were published (cf. note 2). In most cases, this policy was implemented not by local Greeks but by the newcomers from Greece and Asia Minor who did not know and did not learn local dialects. The most ostensive example is Amphyction Demetriou who ran away from Turkey in 1917 to avoid military service and spent many years in Mariupol. He wrote poetry and compiled textbooks in Demotic (cf. Demetriou 1933 and Figure 1). Most parents were against the Hellenization of the school education and tried to send their children to Russian classes because as native speakers of Rumejka they could not understand Demotic (Baranova 2017, p. 105). This general neglect towards local dialects (both Azov Greek and Pontic) was caused mainly by two reasons:

Figure 1.

A page from “Primer for Adult Schools” by Demetriou.

- the ideas of internationalism, so popular in the USSR, implied that all Soviet Greeks should use one language comprehensible to the working class from Greece (Savvov 1931);

- local dialects were often regarded as poor from lexical point of view and inappropriate for literature (Baranova 2010, pp. 239–40).

Still, some scholars believed that the common Greek language should be based not on Demotic Greek but on local dialects (cf. Sokolov 1930, p. 67), and even in Demotic textbooks it is possible to find some local dialectal vocabulary like tʃol ‘field’ or dranás ‘[you] see’ (Demetriou 1933, pp. 49, 66). A group of poets and writers inspired by Georgiï Kostoprav (1903–1938) made a very successful attempt to create literary Rumejka. They were not just content with writing their own poetry and prose but published numerous literary translations of Russian, Ukrainian and European literary classics. Unfortunately, in 1937, the Soviet policy changed and any kind of support of local national identity and culture became the sign of separatism. It resulted in arrest and death of many activists and intellectuals, including Demetriou and Kostoprav. Since then, the knowledge of Russian became obligatory and inevitable.

Until 1961, nobody dared even to mention officially the name of Kostoprav. In November 1962, a poem by Kostoprav in Rumejka was recited during a TV broadcast (Animitsa and Kisilier 2009, p. 52). Despite all efforts of Andrey Beletskiy and Tatiana Chernysheva to revive Azov Greek literature (see Section 1), the first book was published only not long before the collapse of the Soviet Union (Shapurmas 1986).

After Ukraine became independent in December 1991, the role of Ukrainian in the Cis-Azov region has been constantly increasing. Unexpectedly, the biggest threat for Rumejka came from Modern Greek with the start of intensive contacts with Greeks from Greece. At first Rumejs believed that Modern Greek was a more powerful and “better” language (Baranova and Viktorova 2009, pp. 101–2) and it was much more profitable to speak Modern Greek instead of Rumejka. Visitors from Greece usually neglected local dialect, did not try to understand it and regarded it as a corrupt version of their native language. Difficult economic situation and illusions about the “paradise in Greece” led to mass emigration (Voutira 2003, pp. 150, 152; 2004, p. 534). However, many migrants from the former USSR were disappointed when they came to Greece and preferred either to live in two countries or even to return back (cf. Kaurinkoski 2018).

4. Azov Greek Dialect: General Remarks

In this section, there is no chance to provide any detailed linguistic description. Various views on Azov Greek phonetics, morphology and syntax may be found in (Sergievskiy 1934; Chernysheva 1958, pp. 44–78; Zhuravliova 1982; Pappou-Zouravliova 1995, 1998; Symeonidis and Tompaidis 1999; Kisilier 2009a), while a number of lexical archaisms are listed in (Henrich and Pappou-Zouravliova 2003). My goal here is just to underline some important peculiarities (Section 4.1, Section 4.2 and Section 4.3), to discuss the place of Azov Greek among other Modern Greek dialects (Section 4.4) and to provide a brief overview of subdialectal diversity (Section 4.5) and sociolinguistic situation (Section 4.6).

4.1. Phonetics

4.1.1. Vowels

Rumejka vocalism demonstrates several important differences from Standard Modern Greek (=SMG). There is a tendency to raise unstressed /e/ and /o/ to /i/ and /u/ respectively:

| (1) | alipú ‘fox’ | vs. SMG αλεπού /alepú/ |

| líγu ‘a little bit’ | vs. SMG λίγο /líγo/, |

along with a frequent loss of unstressed /i/ and /u/:

| (2) | piγáðj ‘spring, natural fountain’ | vs. SMG πηγάδι /piγáði/ |

| ðlíja ‘work’ | vs. SMG δουλειά /ðuljá / |

These features are often regarded as Northern (see Section 4.4). However, it is important to mention that there are examples when /o/ does not raise to /u/ (psofú ‘die’ vs. SMG ψοφώ /psofó/) and /u/ does not disappear (pulíts ‘little bird’ cf. SMG πουλί /pulí/ ‘bird’). Moreover, /ó/ also frequently turns into /ú/:

| (3) | úla ‘all’ vs. SMG όλα /óla/ |

Sometimes, /o/ instead of expected /u/ becomes /a/:

| (4) | ánθraps ‘man’ or áθarpus vs. SMG άνθρωπος /ánθropos/ |

It may also seem that unlike Standard Modern Greek Rumejka has both [i] and [ɨ]:

| (5) | [‘liγma] ‘curve’ vs. [‘lɨγus] ‘little’ |

Since [ɨ] is never encountered in the initial position and always follows a consonant (Nikolaenkova 2009, pp. 172–73) it is possible to assume that there is no phoneme [ɨ] in Rumejka. Thus, we do not have an opposition of [i] and [ɨ] but the one of palatalized and non-palatalized consonants that precede [i], cf. [‘ʎiγma] vs. [‘liγus] in (5).

The last important distinctive feature of Azov Greek vocalism to be mentioned here is the absence of glide formation, i.e., /ía/ is not transformed into /já/:

| (6) | piðía ‘children, guys’ vs. SMG παιδιά /peðjá/ |

4.1.2. Consonants

Rumejka consonants demonstrate more variation from village to village (cf. Section 4.5) than vowels. In general, there are several sounds absent from Standard Modern Greek: /ʒ/ (ʒangarí ‘blue’), /dʒ/ (dʒanavár ‘wolf’), /ʃ/ (maʃér ‘knife’), /tʃ/ (mátʃa ‘eyes’). Some of them, evidently, result from internal development of the dialect like palatalization: maʃér vs. SMG μαχαίρι /maxéri/, mátʃa vs. SMG μάτια /mátja/, while /ʒ/ and /dʒ/ are, probably, caused by language contacts (see Section 5).

The use of /d/ in most cases may be regarded as a mark of loanword either from Turkic (duʃmáns ‘enemy’, cf. Urum duʃmán) or Slavic (dekábr ‘December’, cf. Russian декабрь /dikábrj/), with the rare exceptions like dropí ‘shame’, cf. SMG ντροπή /dropí/ where /d/ results from some internal processes (Andriotis 1967, p. 233).

4.2. Morphology

4.2.1. Nouns

For many centuries, Azov Greek tended to eliminate formal gender differences. All inanimate nouns have become neuter, and the article in plural is always ta (cf. SMG τα /ta/) regardless of the gender. This process is accompanied by a simplification of nominal paradigms—Rumejka no longer has genitive plural and the use of genitive singular is extremely limited (more details in Mertyris and Kisilier 2017). It is possible to claim that there are only two cases: nominative and accusative (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Example of declension in singular of masculine ‘man’ and feminine ‘hen’.

Some descriptions even propose to treat the cases in Azov Greek as Direct and Indirect, but not as Nominative and Accusative (cf. Viktorova 2009, pp. 198–201). Rather often the functions of the genitive are performed by syntactic constructions with adjunction:

| (7) | gax | trapézj | |||

| corner | table | (Viktorova 2009, p. 205) | |||

| cf. SMG: | γωνία | του | τραπεζι-ού | ||

| /γonía | tu | trapezj-jú/ | |||

| corner | def.gen | table-gen | |||

| ‘corner of the table’ | |||||

A limited number of nouns have special flexions for the attributive function, which probably originates from the genitive endings:

| (8) | áθerp-u | laxardí | |

| man-attr | speech | ||

| ‘human speech’ (Viktorova 2009, p. 205); | |||

| cf. SMG: | ανθρώπ-ου | ||

| /anθróp-u/ | |||

| man-gen | |||

| (9) | níxta-s | pli | |

| night-attr | bird | ||

| night bird’ (Viktorova 2009, p. 205) | |||

| cf. SMG: | νύχτ-ας | ||

| /nixt-as/ | |||

| night-gen | |||

Another explanation of these attributive forms is to treat them as a constituent of a compound. Azov Greek demonstrates several types of compounding, for example, word + word (10) and stem + stem (11):

| (10) | θlíja ‘stomach’ | + pónus ‘pain’ | = θlijapónus ‘stomachache’ |

| (11) | aθrap- ‘man’ | + -u- + faγ- ‘eat’ + -us | = aθrapufáγus ‘cannibal’ |

The configurations such as (8) and (9), probably, follow a special pattern of the word + word type. However, this assumption cannot be discussed here and requires a separate thorough study.

4.2.2. Verbs

The Azov Greek verb system is typical for many regional varieties of Modern Greek. It is thoroughly analyzed in (Kuznetsova 2009). In short, there are two stems—present (imperfective) and aorist (perfective). For the future forms either the particle na or θa/ða is used. Azov Greek has neither perfect nor pluperfect.

4.3. Syntax

4.3.1. Word Order and Pro-Drop

Basic word order in Rumejka is SVO (or SV and VO if there is no either object or subject). It is neutral and much more frequent. Table 3 presents some quantitative data from the narratives and dialogues recorded in Maloyanisol’ in 2003–2004.

Table 3.

Word order calculations in Azov Greek (Kisilier 2009b, p. 375)5.

Even from the Table 3, it is evident that in Rumeika just as in Standard Modern Greek a sentence may have no subject. However, in Modern Greek pro-drop context-dependent subject pronoun ellipsis is the standard and the pronominal subject is always emphasized. In Azov Greek the situation is different and pronominal subjects are more frequently used than null subjects (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Pronominal subject in Azov Greek (Kisilier 2009b, p. 378)6.

The use of a pronominal subject in general has no connection with contrastivity which can be elsewhere in the sentence. Rumejka has a formal focus marker—particle pa (see Section 4.3.4). In (12), for example, pa indicates that the topic is the adverb but not the pronominal subject:

| (12) | γo | kamía=pa | tʃi=ðájna | s-u | skóʎa |

| I | never=foc | neg=went | in-def | school | |

| ‘I have never gone to school’ | |||||

Rumejka may be regarded as a pro-drop language only if we use a broad definition by Brian Joseph (1994, p. 27): “In a NON-pro-drop language <…> every finite verb which can have a subject must have a subject (thus a pro-drop language is one that is not a NON-pro-drop language”.

4.3.2. Clitic Doubling

At the beginning of Section 3, it was mentioned that Azov Greek has clitic doubling, which proves that there were Greek migrations to the Crimea in the Byzantine period (when this phenomenon appeared) or later. It is hardly possible that clitic doubling could have developed in Azov Greek independently. However, in Rumejka it has its own peculiarities. Along with a standard situation when a clitic duplicates a stressed pronoun (13), there are examples when two clitics are involved (14):

| (13) | pot | na=si=dranú | séna |

| when | fut=you=I.see | you | |

| ‘when shall [I] see you?’ (Borisova 2009, p. 400) | |||

| (14) | sis | mas=meγálnit=mas | |

| you | us=you.brought.up=us | ||

| ‘you have brought us up’ (Borisova 2009, p. 401) | |||

It is not clear if Rumejka has strong pronouns in plural. A similar situation can be seen in Tsakonian where personal pronouns in plural have no clitic forms and thus a weak pronoun in singular is frequently used instead:

| (15) | m=orákate | námu |

| me=you.saw | us | |

| ‘you saw us’ (Kisilier 2021, p. 241) | ||

Probably, the examples such as (14) and (15) demonstrate that in Rumejka and Tsakonian, the opposition between strong and weak pronouns has not developed to the full extent and both dialects are still trying various strategies to implement clitic doubling, which may be a rather recent borrowing.

4.3.3. Clitic Pronouns

In Rumejka, clitic pronouns are Xmax clitics7. In the corpus of oral narratives collected in 2001–2006, they more frequently follow finite verbs:

| (16) | éklepsis=mi |

| you.stole=me | |

| ‘you have stolen me’ |

Some factors such as the particles (=proclitics) na and θa/ða in front of the VP make clitic pronouns precede the verb:

| (17) | θa=ta=fáγu | ávir |

| fut=it=I.eat | tomorrow | |

| ‘[I]] shall eat it tomorrow’ | ||

4.3.4. Sentential Clitics

Unlike most Modern Greek dialects, Rumejka has a sentential clitic—a particle pa. It functions as a topic marker and can be added almost to any non-clitic constituent in the sentence. According to Comrie (1980, p. 86f), the position after topic is reserved for the main intonation break. Absence of prosodic stress makes it attractive for sentential clitics:

| (18) | atós | ðjavj | árta | makrá | γo=pa | na=páγu |

| he | he.went.away | rather | far | I=top | fut=I.go | |

| ‘he went rather far away, I shall go as well’ | ||||||

The use of pa in Rumejka seems a very archaic feature and resembles Ancient Greek particles γάρ /gar/ and δέ /de/. Regularly pa is used with the adverbs pánda ‘always’, kamía ‘never’, bðína ‘nowhere’, and with the pronouns ul ‘all’ and káθa is ‘anyone, everyone’.

The particle pa most likely derives from pal or páli ‘again’ (cf. SMG πάλι /páli/) like pa (pal) in Pontic which definitely comes from the same adverb (Papadopoulos 1961, pp. 130, 135, 138). It is tempting to compare the Azov Greek particle with pa from Zakynthos which is an abridged version of πάνω /páno/ ‘above’, cf. (19):

| (19) | Rumejka: | aðó=pa | |

| here=top | |||

| Zakynthos:8 | eðó=pa | ||

| here=top? | |||

| SMG: | εδώ | πάνω | |

| /eðó | páno/ | ||

| here | above | ||

| ‘exactly here’ | |||

However, this etymology is valid only for locative adverbs while in Rumjeka pa is used in many other contexts as well.

4.4. Rumejka and Modern Greek Dialects

The famous German linguist Paul Kretschmer was the first to compare Rumejka with other dialects of Modern Greek. He noticed that some important phonetic peculiarities of Azov Greek have parallels both in Northern Greek dialects) and in Pontic. He even suggested that Rumejka could be a variety either of Pontic or of Northern Greek (Kretschmer 1905, p. 18). In fact, it is not difficult to find a number of common features between Rumejka and these dialects.

4.4.1. Azov Greek and Pontic

Paul Kretschmer was right as he mentioned that both Rumeika and Pontic have palatalization:9

| (20) | Rumejka and Pontic ʃer ‘hand’ vs. SMG χέρι /xéri/; cf. Section 4.1.2 |

Moreover, Pontic and Rumejka lack glide formation /ía/ > /já/ (21) and demonstrate the loss of unstressed /u/ (22) and /i/ (20):

| (21) | Rumejka and Pontic karðía ‘heart’ vs. SMG καρδιά /karðjá/; cf. Section 4.1.1 ex. (6) |

| (22) | Rumejka pli ‘bird’ vs. SMG πουλί /pulí/ cf. Pontic γráftne ‘[they] write’ (Eloeva 2004, p. 82) vs. SMG γράφουν /γráfun/ |

Along with phonetics, Pontic and Rumejka have some similarities in vocabulary and phraseology, negations, verb flexions (see Symeonidis and Tompaidis 1999, pp. 133–39) and syntax. However, some scholars did not regard Rumejka as a variety of Pontic (Dawkins 1942, p. 24). In fact, there are important differences:

- Pontic has preserved /e/ which derives from Ancient Greek /e:/ (η): éton ‘[s/he] was’ vs. Rumejka ítun;

- unlike Pontic, Rumejka has lost /-n/: ðéndro/ðíndro ‘tree’ vs. Pontic ðéndron;

- the word used for pronoun ‘what’ is one of the most important lexical isoglosses that divides Modern Greek dialects into two groups. Azov Greek and Pontic belong to different groups: Rumejka ti vs. Pontic ndo;

- both Rumejka and Pontic have sentential particle pa (see Section 4.3.4) but in Pontic it has a much broader use (see Sitaridou and Kaltsa 2014, pp. 4–5, 7–10);

- in Pontic, clitic pronouns may only follow the verb even if it is preceded by a modal particle (cf. Section 4.3.3):

| (23) | a=traγuðó=se |

| fut=I.sing=you | |

| ‘[I] shall sing of you’ |

4.4.2. Azov Greek and Northern Greek Dialects

Paul Kretschmer found a set of important parallels between Rumejka and Northern Greek dialects in the development of unstressed vowels: both demonstrate the rise of /e/ to /i/ and /o/ to /u/ and loss of unstressed /i/ and /u/ (see Section 4.1.1). There is also an essential morphosyntactic common feature—instead of the genitive, both dialects use the accusative without a preposition for the indirect object:10

| (24) | Rumejka: | γo | ípa=tun | ||

| I | I.told=him.acc | ||||

| ‘I told him’ | |||||

| Northern Greek: | ána | tin=ípi | tin | mitéra=tis | |

| Ann | her.acc=s/he.told | acc | mother=her | ||

| ‘Ann told her mother’ | |||||

Moreover, the genitive plural is used only in cliches (Mertyris 2014, p. 213f; Mertyris and Kisilier 2017, pp. 468–69). The hypothesis of a Northern Greek origin of Rumejka is not less popular than the “Pontic” one (cf. Kontosopoulos 2001, p. 109; Sokolov 1930, p. 64). Still, it is important to underline that the pronominal syntax of Northern Greek dialects is the same as in Standard Modern Greek, while in Rumejka it resembles the medieval situation (see Section 4.3.3).

4.4.3. Azov Greek and Dialectal Isoglosses

An appropriate classification of Modern Greek dialects despite multiple promising attempts (cf. Newton 1972; Kontosopoulos 2001; Trudgill 2003; Ralli 2006) is still only desired due to the lack of reliable data. However, we already have a set of parameters (isoglosses) that are suitable for comparison of various dialects, although they are not sufficient for a proper dialectometric analysis. These isoglosses are:

- high vowel loss, see examples (1) and (2);

- gemination: South-eastern γrámma ‘letter’ vs. Rumejka γráma;

- glide formation, see example (6);

- preservation of Ancient Greek /e:/ (η), see Section 4.4.1;

- loss of intervocalic /-v-/, /-ð-/, /-γ-/: Southeastern láin ‘oil’ vs. Rumejka laðj, Southeastern fóos ‘fear’ vs. Rumejka fóvus, Southeastern máos ‘magician’ vs. Rumejka máγus;

- retention of final /-n/, see Section 4.4.1;

- dissimilation of fricatives and. plosives: Southeastern avgón ‘egg’ vs. Rumejka avγó;

- epenthesis of /γ/ in verb flexion -εύω /-évo/: Southeastern ðulévγo ‘to work’ vs. Rumejka ðulévu;

- palatalization, see Section 4.1.2;

- tsitakism: Old Athenian tserós ‘time’ vs. Rumejka kerós (with local variants tʃirós and tirós with palatalization);

- interrogative pronoun ‘what’ is ti, see Section 4.4.1;

- accusative is used instead of genitive, see example (24);

- pronominal clitic always precedes a finite verb unless the clause hosting the verb is in the imperative mood, see Section 4.3.3 and example (24);

- clitic pronouns are Xmax clitics, see Section 4.3.3.

Table 5 demonstrates how these parameters are represented in various dialects of Modern Greek including Rumejka.

Table 5.

Rumejka and Modern Greek dialects11.

Table 5 does not provide enough evidence to conclude which Modern Greek dialect is closer to Rumejka. In order to find out, we shall have to create numerous dialectal databases, and this process may take many years. However, even the very limited information from the Table 5 clearly demonstrates that Azov Greek has common features not only with Northern Greek or Pontic. Syntactically and prosodically, it seems to be rather close to Cappadocian, so the hypothesis that Rumejka belongs to the same group as Pontic, Cappadocian, Pharasiot and Silliot Greek (cf. Karatsareas 2014, p. 79) may have some grounds.

4.5. Subdialects of Azov Greek

The area where Rumejka is/was spoken is relatively large. It comprises at least 17 villages, and it is therefore no wonder that Azov Greek is not uniform but has its own local variants. Most scholars distinguish five subdialects of Rumejka (see Figure 2; cf. Diamantopoulo-Rionis et al. 2006, p. 9; Sokolov 1930, pp. 63–64), which are spoken in:

Figure 2.

Subdialects of Azov Greek.12

- [1]

- Urzuf and Yalta;

- [2]

- Bolshoj Yanisol (Velika Novosilka), Styla and Konstantinopil’;

- [3]

- Bolshaya (Staraya) Karakuba, Novaya Karakuba (Krasna Polyana) and Buhas;

- [4]

- Sartana, Chermalyk and Makedonivka;

- [5]

- Maloyanisol’, Novoyanisol’, Truzhenka and Cherdakly (Kremenivka).

Sokolov believed that this classification reflected the distance between local variants of Rumejka and Standard Modern Greek. For example, the negation is

- ðen—in Urzuf and Yalta [subdialect 1], Bolshoj Yanisol, Styla and Konstantinopil’ [2] and Sartana, Chermalyk and Makedonivka [4];

- ti (<Ancient Greek οὔχι /úxi/) in Bolshaya Karakuba, Novaya Karakuba and Buhas [3] and tʃi (also from οὐχί /uxí/) in Maloyanisol’, Novoyanisol’, Truzhenka and Cherdakly [5].

At the same time Sokolov (1930, p. 65) supposed that southern subdialects (probably [1] and [4]) had tsitakism. The differences between subdialects are found at various linguistic levels except syntax. Here are some examples:

| (25) | vowels: | neró ‘water’ [1] vs. niró [2, 3, 4, 5] |

| ðendró ‘tree’ [1] vs. ðendrú [4] vs. ðindró [3, 4, 5] | ||

| xron ‘year’ [1, 2] vs. xrónu [3, 4, 5] | ||

| consonants: | tifáʎ ‘head’ [1], tifál [2], ftjal [3, 4], tʃfal [5] | |

| (26) | vocabulary: | títirj ‘yellow’ [1, 2] vs. títírns [2] vs. panjár[u/i]s [3] vs. panjárk[us] [4] vs. sari[s] [3, 4, 5] |

| (27) | verb morphology: | imperfect of the verb ðúγu ‘give’ (1sg)—jéðuγa [1] vs. jéðuγa [2] vs. ðújʃka [3], éðuγa [4], ðókuʃka [5] (Kuznetsova 2009, p. 291) |

Only phonetic distinctive features are systematic enough to be regarded as possible local isoglosses. For example, imperfect forms with -ʃka are encountered not only in subdialects three and five as it could be concluded from (28):

| (28) | kámu ‘do’ (1sg)—jékamna [1] vs. kámjiʃka [2] vs. ékaγa and kámjiʃka [3], éftaγa [4], éftaγa and kámjiʃka [5] (Kuznetsova 2009, p. 289) |

It is important to mention that almost all phonetic peculiarities generally described as special features of Rumejka (see Section 4.1) are relevant only for some subdialects; cf. (25).

4.6. Current State of Azov Greek

In 1859, the famous ethnographer and historian Teoctist Khartakhay (already mentioned in Section 1) compiled the first dictionary of Rumejka entitled “Glossary of a dying Greek idiom” (published in Chernysheva 1959). Although Khartakhay himself did not explain what he meant but it is not difficult to suppose that in the mid-19th century, older and younger generations did not speak Rumejka the same way. Nearly all linguists who studied Azov Greek in the 20th century also pointed out that the dialect required protection and support because young people were not much interested in it (cf. Chernysheva 1958, p. 18; Chatzidaki 1997). This observation fully describes the situation I saw in 2004 and later. However, it was always possible to find multiple dialect experts. There are two possible explanations:

- Not everybody was ready to speak Rumejka and give interviews in front of a stranger;

- Young people who did not pay much attention to their dialect began to think about their identity as they grew older and then connected it with their capability to speak Rumejka.

The situation when people decide to speak their native dialect only when they get old is not something exceptional (cf. Vahtin and Golovko 2004, pp. 129–31). It seems that the language/dialect can exist this way for many generations. During the expeditions of 2001–2006, it became evident that Rumejka is a language of adults. Children and teens did not speak the dialect, but generally their passive knowledge was good enough to understand it (Gromova 2009). In some villages, for example in Maloyanisol’, Rumejka was frequently used as a “secret” male language and it motivated younger men to speak it.

There are no monolingual speakers of Azov Greek (only once in Maloyanisol’ I met a woman (93 years old) who could not speak and understand either Russian or Ukrainian). Everyone, born after 1935, has Russian as L1. Recently, the importance of Ukrainian has increased and there could be multiple speakers whose L1 is Ukrainian. After 1960s, the linguistic situation in different villages was not the same. The coastal resorts Urzuf and Yalta started to lose the dialect due to a permanent influx of tourists. Most inhabitants of these villages, even the older ones, could generally recollect just a couple of words in Azov Greek.

The recent war in Ukraine may have disastrous consequences for Azov Greek. If the Greek-speaking minority decides to migrate from the region, the dialect will be extinct within the next 20–30 years. The experience of migration to other parts of Ukraine, to Russia, to Greece, etc., clearly demonstrates that the next generation will have no intention to study the dialect in a new place and their Greek identity will be fully connected with Standard Modern Greek.

5. Language Contacts

The historical evidence (cf. Section 3) makes it possible to provide a list of languages involved in contact with Rumejka:

- Turkic (Crimean Tatar and Urum);

- Slavic (Russian and Ukrainian);

- Modern Greek and its varieties (for example, Pontic).

I did not include German and Albanian in the list although there were/are several Albanian and German villages in the region (see Section 3). Nothing is known about their interactions with Greeks, and I failed to find any linguistic feature in Rumejka that could be even hypothetically interpreted as German or Albanian.

5.1. Contacts before Migration

It is very difficult to create with complete certainty a timeline of language contacts, but there is no doubt that some languages were in contact with Rumejka earlier than the late 18th century, i.e., before the emigration from the Crimea, for example, Gothic, Khazar and even Italian dialect of Genova—in 1261 merchants from Genova got special trade priorities on the Black Sea (Chernysheva 1958, p. 24). Possible contacts with these languages will not be observed in this subsection for two reasons:

- they left no visible traces in Rumejka;

- nobody knows when and where Rumejka appeared. It is not clear if the dialect already existed in the 13th or 14th century but a Russian Byzantine Greek textbook of the 15th century and the Letter of the Crimean Khan to the Republic of Genova (written about 1470) along with certain Northern Greek and Pontic features demonstrate some peculiarities which resemble Rumejka (Henrich 1998) like the use of the word mursí ‘cellar’ (Christou 2007, p. 28).

I insist that for the Crimean period we can seriously observe only contacts with Modern Greek and its varieties (Section 5.1.1) and with Crimean Tatar and Urum (Section 5.1.2). We probably should exclude from consideration any possible contacts with Slavic, although according to Christou (2007, p. 82) the aforementioned documents of the 15th century had some Slavic elements such as masculine flexion -ij for all genders of an adjective.

5.1.1. Azov Greek and Other Varieties of Greek

Contacts with other varieties of Greek must have been constant before the speakers of Rumejka moved to the Azov Sea. According to Tatiana Chernysheva (1958, p. 39), residents of Urzuf and Yalta [subdialect 1, cf. Section 4.5] used the expression lej kritiká ‘[s/he] speaks Cretan’ when they wanted to say that someone spoke non-local Greek. Chernysheva believes that since their ancestors lived in the Crimea close to the sea (as one can see from the toponymics they brought with them from the Crimea), they had trade relations with Cretan merchants.

Azov Greek folklore has many songs that appeared in the Crimea in the Middle Ages. Akritic song about Yannis and Dragon is a very good sample. In (29) I cite its first four lines (from Khadzhinov 1979; singer born in 1904; transcription, punctuation and translation are mine—MK):

| (29) | Janákus ðjávin stu niró, stun piγáðj ekatévinne íver ki ton ðjrákunda stu piγaðjé ta ʃíli.“Ne kaliméra, ðrákunda!”—“Kalós tun Janáku!” akónepsa ta ðóndja=mu, irévu na=se=fáγu” ‘Yannis went to fetch some water, [he] came down to a spring [and he] found a Dragon on the edge of the spring. “Well, good morning, Dragon!”—“Hello, Yanni! [I] have sharpened my teeth and [I] want to eat you”’ |

The metre of this song (and of all old songs brought from the Crimea) is the traditional dekapentasyllable. Its language has multiple peculiarities typical for Azov Greek, for example

- /e/ > /i/: niró [line 1] vs. SMG νερό /neró/;

- /o/ > /u/: [s]tu[n] [1, 2, 3] vs. [σ]το[ν] /[s]to[n]/, Janáku[s] [1, 3] vs. Γιαννάκο[ς] /janáko[s]/, ðjrákunda [2, 3] vs. SMG δράκοντα /ðrákonda/, irévu [4] vs. SMG γυρεύω /jirévo/, fáγu [4] vs. SMG φάω /fáo/;

- palatalization: ʃíli [2] vs. SMG χείλη /xíli/.

At the same time, there are several non-Azov Greek features:

- /e/ ≯ /i/: se [4] = SMG σε /se/ instead of si, example (13);

- /o/ ≯ /u/ ton [2] = SMG τον /ton/ instead of tun [3];

- Modern Greek possessive pronoun mu [4] = SMG μου /mu/ instead of m (with the loss of unstressed /u/).

Different variants of the song may have different sets of features: some singers try to get rid of all “alien” elements, others, on the contrary, preserve even more “Modern Greek” peculiarities: neró (Kir’akov 1994, p. 25) = SMG νερό /nero/ vs. niró [1].

Pontic influence on Azov Greek that could result in some similarities in phonetics, morphology and multiple lexical and phraseological borrowings (see Section 4.4.1) and even borrowing of a sentential clitic pa (Section 4.3.4) most likely took place during the Crimean period.

5.1.2. Azov Greek and Turkic

There is no doubt that Azov Greeks became bilingual (i.e., speakers of both Greek and Crimean Tatar or its subdialect Urum) already in the Crimea because in the Crimean Khanate Crimean Tatar was the only language of administration and trade. The start of this bilingualism perhaps dates to the 16th century (Aradzhioni 1998). It is important to mention that Crimean Tatars have influenced not only the language of Greek speakers but their cooking (like traditional deep-fried turnover chebureki; for more details see Novik 2009, pp. 68–70) and traditions (e.g., folk wrestling Kuresh typical for Central Asia). It is also amazing that some Greek-speaking villages have Turkic names. For example, in toponyms Bolshaya or Staraya Karakuba and Novaya Karakuba the second constituent is of the Turkic origin, cf. Turkik kara ‘black’ and Turkish kubbe ‘dome, vault’. Initially, the first toponym, instead of the Russian words Bolshaya ‘big’ or Staraya ‘old’, had Arγín (Henrich and Pappou-Zouravliova 2003, p. 126), cf. Turkish argın ‘exhausted, tired’.

The Crimean Tatar/Urum—Greek bilingualism had an impact on various linguistic levels of Rumejka. Most profoundly it affected vocabulary, where many words from different semantic classes and with various stylistic background are of the Turkic origin. Here are some of them (for a more representative list, see Horbatsch 1979–1980, pp. 428–44):

| (30) | nouns: | burán ‘storm’ = Urum13 |

| jardím ‘help’ = Urum | ||

| tʃitʃák ‘flower’, cf. Urum tʃitʃék | ||

| tʃol ‘field’, cf. Urum tʃöʎ | ||

| vaxt ‘happiness’ = Urum | ||

| adjectives: | γaríp or γarípku ‘poor’, cf. Urum γaríp | |

| jáʃis or jáʃkus ‘young’, cf. Urum jaʃ | ||

| ʒangár or ʒangarí ‘blue’, cf. Crimean Tatar zenger ‘sky blue’ | ||

| temiz[lix] ‘clean’, cf. Urum temiz | ||

| xazáx ‘alien’, cf. Urum xazáx ‘Russian or Ukrainian’ |

Turkic borrowings are perfectly incorporated into Azov Greek grammar. Nouns usually have plural form:

| (31) | tʃol | > | tʃóʎ-a |

| field | field-pl | ||

| tʃitʃák | > | tʃitʃákj-a | |

| flower | flower-pl |

Masculine animated nouns of Turkic origin usually get flexion -s(j)/-us/-is (the choice mostly depends on the subdialect) and are declined like other nouns in the singular (see Table 2):

| (32) | nom | duʃmán-s ‘enemy’ (cf. Urum duʃmán) |

| acc | duʃmán | |

| nom | misafír-sj ‘guest’ (cf. Urum misafír) | |

| acc | misafír |

Nouns borrowed from Turkic are frequently used for verb formation (see also Kuznetsova 2009, p. 275):

| (33) | jangáz ‘sourpuss’ (cf. Crimean Tatar jañğırdı ‘tinkling’) > jangazlévu14 ‘to grumble’ |

| laxardí ‘speech, conversation’ (cf. Urum laxirdí) > laxardévu ‘to speak’ | |

| tʃitʃák > tʃitʃakíz[u] or tʃitʃakónu ‘to blossom’ | |

| xulátʃ ‘step’ (cf. Urum xulátʃ ‘girth, measure of length’) > xulatʃévu ‘to pace’ |

Adjectives may have various gender endings: jáʃk-us (masculine), jáʃk-a (feminine). Some words of Turkic origin may have Greek equivalents, e.g., dʒanavár ‘wolf’ (also ‘beast’ = Urum) and líkus (cf. SMG λύκος /líkos/).

A brief analysis of the lexical borrowings makes me believe that the many words come not from Crimean Tatar but from Urum:

| (34) | dʒanavár ‘wolf, beast’, cf. Urum dʒanavár ‘wolf, beast’ and Crimean Tatar canavar ‘beast’ |

| laxardí, cf. Urum laxirdí and Crimean Tatar laqırdı | |

| xulátʃ, cf. Urum xulátʃ and Crimean Tatar qulaç |

In phonetics, sounds [ɨ] (see also Section 4.1.1, especially example (5)), /ʃ/, /tʃ/ and /dʒ/ may also result from the impact of Turkic (cf. Podolsky 1986, pp. 101–102) as they are regularly encountered in the borrowed words. In morphology, one could suspect Turkic influence in possessive pronouns:

| (35) | ‘older brother’ | γáka-s |

| older.brother-nom | ||

| ‘my older brother’ | γáka=m | |

| older.brother=my | ||

| ‘my father’ (Urum) | baba-m | |

| father-my |

However, there is an alternative explanation as well: possessive pronouns have lost in Rumejka the vowel due to high vowel loss (mu > m ‘my’, su > s ‘your’, tu > t ‘his’, tis > ts ‘her’) and flexion -s in γákas was assimilated by /m/.

5.2. Contacts after Migration

During several decades after moving to the new place, the linguistic situation remained the same: Urum was the language of administration and commerce, and it was spoken in the main city of the region—in Mariupol. Nevertheless, I think that all phenomena described in Section 5.1.2 have already appeared in Rumeika by the time of migration because the contacts with Urum in the Crimea were much longer and probably more profound. Hence, in this subsection I shall observe only interactions with Slavic (Section 5.2.1) and Modern Greek (Section 5.2.2).

5.2.1. Azov Greek and Slavic

Before the 20th century any education in a language other than Russian was impossible and most renowned persons of Azov Greek origin could speak Russian from their childhood, e.g., the aforementioned Teoctist Khartakhay (born in 1836) and the famous painter Arkhip Kuindzhi (born in 1841). However, some scholars believe that until the Soviet revolution of 1917 ordinary villagers did not speak Russian (Iakubova 1998, p. 88). This opinion does not seem to be correct. Fyodor Braun who visited Greek villages around Mariupol in 1890 pointed out that all males could speak Russian, and youngsters usually used Russian for male communication and even sang Russian songs. By contrast, local women were “more conservative” and could speak only Rumejka (Braun 1890, p. 85).

There is no doubt that after the Soviet revolution contacts with Russian became more intense, and Rumejka borrowed multiple words for new concepts. It is evident from folk songs:

| (36) | tu kamúna ti nuníz? manítsja as ta fóta aluníz xórsit méγa tu zajáh manítsja, pjémena ðixos ʃajáh tata=s, mána=s en kalí manítsja, plóγu=s iʃ amán skilí ‘what does the commune (= kolkhoz) think about? [my] Mommy thrashes [even] on the Epiphany. [She] paid a big tax. Mommy, [I] am left without [any] shawl. Your Daddy [and] your Mommy are good, [Oh] Mommy, [and you] are like a dog yourself’15 |

The Soviet word kamúna, which was later replaced with word kolhoz, has a very specific Russian phonetic feature—a shift from unstressed /o/ to /a/, i.e., in Russian the word is written кoммуна (kommuna) and pronounced /kamúna/. It is also noteworthy that unlike (29), the song in (36) is totally Russian or Ukrainian in its metre and rhyme. The Azov Greek literature that was created at that time also took Russian literature as a sample. Many literary oeuvres were translated from Russian. Azov Greek poets and writers took multiple literary devices but tried to avoid direct linguistic borrowing. They used Russian vocabulary when there was no equivalent in Rumejka. For example, in Kostoprav’s translation of Chekhov one can find γοςτίνιτςα (gostínitsa) ‘hotel’ and κοριντόρ (koridór) ‘corridor’ (Chekhov 1936, p. 5). These words were definitely absent from Rumejka, and Kostoprav, although he knew Demotic Greek (cf. Section 5.2.2), preferred to borrow lexemes from Russian.

After 1937, when Greek was completely forbidden from official life and education (see Section 3), the destiny of Azov Greeks was to become speakers of Russian. For the first time Rumejka ceased to be the dominant language for its native speakers, except the generation born in 1920 and earlier. Even in the period of Crimean Tatar/Urum—Rumejka bilingualism, Rumejka has never been an “orphan child” in this pair. In opposition with Russian, Rumejka had to retreat even as a tool for “internal” communication. The impact of Russian (and later of Ukrainian) is so strong that code-switching has become quite a regular phenomenon. In example (37), the Russian verb is followed by the Greek morphosyntactic construction:

| (37) | reʃíla | na=ksevj | oks | maréja |

| she.decided | to=go.out | out | side | |

| ‘[she] decided to go out’ (Lisitskaya 2009, p. 150) | ||||

Russian morphosyntactic constructions may be used as well, such as Russian nominal predicate in the ablative (38) instead of the nominative, which is more typical for Azov Greek (39):

| (38) | atjí | ðulévj | agronóm-am | (Lisitskaya 2009, p. 144), | |

| cf. Russian: | oна | рабoтает | агрoнoм-oм | ||

| /aná | rabótaǝt | agronóm-am/ | |||

| she | works | agronomist-abl | |||

| (39) | atjí | ðulévj | agronóm-ø | ||

| she | works | agronomist-nom | |||

| ‘she works as an agronomist’ | |||||

Even very competent speakers of Rumejka tend to use Russian numerals, especially when they are bigger than ten:

| (40) | jomúsa | vósjemdjesjat | dva |

| I.filled | eighty | two | |

| ‘[I] was eighty two’ | |||

Apart from code-switching, it is easy to find multiple phenomena that result from the influence of Russian and Ukrainian. Expectedly, Rumejka has a lot of lexical borrowings from Russian. Even the country name ‘Greece’ is borrowed from Russian:

| (41) | ta | traγóðja=s | <…> | traγuðún=ta | písu | γrjétsija |

| def | songs=your | they.sing=them | in | Greece | ||

| ‘your songs <…> [they] sing them in Greece’ | ||||||

Nouns of Russian and Ukrainian origin can be used either with an article or without any:

| (42) | γo | aγapú | tu | kravátj |

| I | I.love | def | bed | |

| γo | aγapú | kravátj | ||

| I | I.love | bed | ||

| ‘I like [my] bed’16 (Lisitskaya 2009, p. 139) | ||||

They usually make the plural with the same flexions as other Rumejka nouns:

| (43) | tsíberk-a | > | tsibérk-is |

| bucket-sg | bucket-pl | ||

| urók-ø | urókj-a | ||

| lesson-sg | lesson-pl |

Sometimes it is rather difficult to disentangle code-switches from borrowings. This is the case of the Russian infinitive in (44):

| (44) | pos | numát | na=ðájnam | pjis | éna | spjitj | evakuíravatsa |

| how | men | subj=we.go | in | one | house | to.be.evacuated (inf) | |

| ‘How many persons from [our] house would go to get evacuated’17 | |||||||

On the one hand, Azov Greek has no verb ‘to evacuate’ as it was irrelevant before the Second World War. That is why evakuíravatsa may be treated as a loanword. On the other hand, the infinitive replaces the Azov/Modern Greek construction “na + subjunctive”, i.e., the speaker switches from the Azov Greek morphosyntax to the Russian one as he discusses the situation, which has to do with her former Soviet identity. Moreover, when the Russian infinitive is borrowed, it is used in combination with a verb kámu ‘to do’ but not separately as it was in (44):

| (45) | kámu | t͡ʃitátj |

| I.do | to.read (inf) | |

| ‘[I] read’ | ||

| ékama | ʒáritj | |

| I.did | to.roast (inf) | |

| ‘[I] roasted’ | ||

In the hortative, the Greek particle as ‘let’ is regularly duplicated with Russian daváj with the same meaning. Probably, in Rumejka, daváj has become either an adverb or discourse particle:

| (46) | daváj | as=válum | míla |

| let.us | let.us=we.put | apples | |

| ‘let us put apples…’ (Lisitskaya 2009, p. 151) | |||

Russian adverbs of place (47) are generally accompanied with a sentential clitic pa (see Section 4.3.4) like the Azov Greek ones (48):

| (47) | kruγóm=pa |

| around=top | |

| (48) | pandú=pa |

| everywhere=top | |

| ‘everywhere’ |

Some phonetical peculiarities of Azov Greek resemble those of Russian. They both have [ɨ] (see also Section 4.1.1, especially example (5)) /ʃ/, /tʃ/ and /ʒ/. In Russian, unstressed /e/ becomes /i/ (49) and unstressed /o/ turns into /a/ (50):

| (49) | Russian: | /ʎisá/ ‘woods’ | vs. /ʎés/ ‘wood’ |

| Rumejka: | pitú ‘to fly’ | vs. SMG πετώ /petó/ (cf. Section 4.1.1, example (3)) | |

| (50) | Russian: | /paʎá/ ‘fields’ | vs. /póʎe/ ‘field’ |

| Rumejka: | áθarpus ‘man’ | vs. SMG άνθρωπος /ánθropos/ |

Like in Rumejka (see Section 4.3.1), in Russian the pronominal subject can be omitted and its use is not connected with emphasis and the neutral word order tends to be SVO (SV and VO). In my opinion, these phenomena may also be contact-induced, although it is almost impossible to prove this hypothesis.

5.2.2. Azov Greek and Modern Greek

Since the second part of the 19th century, some Azov Greek intellectuals knew Modern Greek. For example, in the notebooks of Teoctist Khartakhay there is a Greek song about the war with Napoleon (published in Vasileva and Kisilier 2018, pp. 281–83) free from any local dialectal features. Several decades later, in 1902, Demian Bgaditsa transformed the renown Cretan masterpiece “The Sacrifice of Abraham” into several songs in Rumejka that were popular until recently (two variants are published in Karpozilos (1994) and Kisilier (2019, pp. 114–19)). It is remarkable that the language of these translations is more influenced by Russian than by Greek. Bgaditsa even uses an Old Russian word paláta ‘house, palace’ for a good rhyme (Kisilier 2019, p. 114).

Since the Soviet policy was focused on Demotic Greek (see Section 3), all local men of letters had to take it into account. Most literary texts were written in Demotic such as the following abstract by Aleko Rionis (written in 1933):

| (51) | Oρμάτε | μπρος! | Σαν | τι | φοτιά, |

| /ormáte | mbros | san | ti | fotjá/ | |

| Για | να | φλογίςτε | κάθε | βλέμα | |

| /ja | na | floγíste | káθe | vléma/ | |

| ‘Rush forward! Like a fire | |||||

| In order to set fire to each glance’ (Fotiadis 1990, p. 78) | |||||

Even the poets and writers who tried to create literary Rumejka could not completely get rid of Demotic influence. The best local poet Georgiï Kostoprav wrote the following in the afterword to his most famous poem “Leontiǐ Honagbeǐ”:

| (52) | Μετρύ | χριαζυμένο | να | λέγυ | κάμποςα | λόγια |

| /metrú | xrjazuméno | na | léγu | kámbosa | lója/ | |

| για | τυ | πιίμα | «Λεόντι | Χοναγμπέις». | ||

| /ja | tu | piíma | leónti | xonaγbéjs/ | ||

| Τυ | πιίμα | μυ | ίνε | γραμένυ | για | |

| /tu | piíma | mu | íne | γraménu | ja/ | |

| τυς | γιαςςλαρύς | |||||

| /tus | jaʃlarús/ | |||||

| ‘[I] think it is important to say some words about the poem “Leontiǐ Honagbeǐ”. My poem is written for young people’ | ||||||

In (52), there are several purely Demotic features:

- λέγυ /léγu/ ‘say’ (cf. SMG λέγω /léγο/) vs. Rumejka laxarðévu;

- μυ /mu/ (cf. SMG μου /mu/) vs. Rumejka m, see (35);

- τυς /tus/—article masculine plural accusative (cf. SMG τους /tus/); in plural Rumejka uses article ta for all genders (cf. Section 4.2.1);

- ίνε γραμένυ /íne γraménu/ ‘is written’ (cf. SMG είναι γραμμένο /íne γraméno/; original Rumejka has no participles that are not adjectivized and passive perfect forms like this one are hardly possible. It is noteworthy that Kostoprav made such a wide use of these forms that Sergievskiy (1934, pp. 582–83) even included them in his grammatical description.

“Domination” of Demotic was not too strong and finished too quickly (in 1937) to have any visible influence on the spoken Rumejka. Only after more than forty years, Azov Greeks had a chance to “meet” Standard Modern Greek again. This “encounter” was in no way beneficial for Rumejka: definitely it seemed less attractive to the younger generation than Standard Modern Greek.

Most young Azov Greeks who started to learn Standard Modern Greek did not speak Rumejka, so Standard Modern Greek affected the status of Rumejka but not the dialect itself. However, in the newborn Azov Greek literature that reappeared in 1990s, it is possible to find some Modern Greek elements. The best way to demonstrate them is to compare the titles of two popular books of poetry:

| (53) | (Shapurmas 1986): | karðjakó=m | to | Priazóvje |

| cordial=my | def | Azov.region | ||

| ‘My darling Azov region’ | ||||

| (Meotis 1996): | xrisí=mu | Meotíða | ||

| golden=my | Meotida | |||

| ‘My golden Meotida (= Azov region)’ | ||||

While in the first title, one can see the Rumejka possessive pronoun m, the second title has a possessive pronoun mu (= SMG μου /mu/).

6. Conclusions

The history of Azov Greek started long before its speakers appeared in the Azov steppe. The dialect almost always had to interact with different languages. The contacts with other varieties of Greek are the longest and the most difficult for research. For the most part it is not clear if the peculiarity was borrowed from another variety of Greek or is a cognate developed parallelly without contact involved. This is the case with the Northern features in Rumejka or similarities with Pontic: Rumejka could either be one of Northern/Pontic dialects or just have a long-term contact with them (for example, the speakers of Pontic appeared in the Crimea in the 15th century and in the Cis-Azov region in 1820s). The interactions with Standard Modern Greek were neither intensive nor very long (in 1930s and then since 1990s) and they visibly affected only the language of Azov Greek literature.

Much more transparent are the contacts with Turkic and Slavic. In the Crimea, Greeks coexisted with Crimean Tatars for many centuries. Probably, by the 16th century, some of them even lost their native Greek dialect and started to speak a variety of Crimean Tatar (Urum) while others had to become bilingual. Even the migration to the Azov steppe did not cause immediate [socio]linguistic changes. Only in the second part of the 19th century Urum ceased to be an important language of culture and commerce and gave way to Russian. Initially, Russian was used among males but from 1937 it became the obligatory and dominant language. In the USSR, the Cis-Azov region belonged to Ukraine, and Azov Greeks had some contacts with Ukrainian (for example at school), although their region was mainly Russian-speaking. As Ukraine became independent in 1990s, the importance of Ukrainian kept constantly increasing.

All these mentioned languages affected Rumeka:

- in vocabulary—Pontic, Crimean Tatar/Urum, Russian and Ukrainian;

- in phonetics possibly —Pontic, Urum, Russian and Ukrainian;

- in morphology and morphosyntax possibly—Urum, Russian and Ukrainian;

- in syntax—Russian and possibly some varieties of Modern Greek.

Contact-induced phenomena may have different outcomes. The most common one is direct borrowing. Contact studies of the world languages clearly prove that almost anything can be borrowed. Thus, in the dialect of Eratyra (Western Macedonia) we can even find incorporation of pronominal clitic—the phenomenon which is typical for Albanian:

| (54) | Eratyra: | lisí-me-ti | |

| untie.pfv-me-imp.2pl | |||

| vs. SMG: | λύσ-τε | με | |

| untie.pfv-imp.2pl | =me | ||

| ‘untie me’ (Lopashov 2006, p. 162) | |||

| cf. Albanian: | ndihmo-na-ni | ||

| help-us-imp.2pl | |||

| ‘help us’ (Buchholz and Fiedler 1987, p. 452) | |||

Sometimes in the course of interaction, languages do not exchange elements or patterns but play the role of motivators, provoke or support the development of some internal processes. For example, Ancient Greek specially in its popular narrative tradition could rarely use periphrastic constructions, which consisted of the past forms of the verb ‘to be’ and a participle as forms of imperfect (Björck 1940; Caragounis 2004, p. 177):

| (55) | ἦν | διδάσκων |

| /ẽ:n | didáskɔ:n/ | |

| he.was | teaching | |

| ‘[he] taught’ | ||

Due to the Semitic linguistic influence, these kind of periphrastic constructions became so widespread in Koine Greek that some scholars even treated it as Semitism (cf. Blass and Debrunner 1990, pp. 285–87; Turner 1976).

In my opinion, contact-induced phenomena in Rumejka largely belong to the same type: many features that were discussed in this contribution were not borrowed, but their evolution could be motivated and “supported” by other languages (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Features hypothetically supported by language contacts.

Funding

The research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, Project No. 22-48-09003, https://rscf.ru/project/22-48-09003/ (accessed on 12 April 2022).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Saint Petersburg University.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to restrictions in data collection policy and to protect participant anonymity.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the editors of this volume and anonymous reviewers for the emendations and thought-provoking commentaries.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Its creators are still unknown to me. |

| 2 | Several years ago, we started to digitalize Soviet Greek books published in 1924–1937. This collection is constantly increasing and it can be freely accessed online (https://archive.org/details/sov-greek?tab=collection, accessed on 10 April 2022). |

| 3 | Unfortunately, poor condition does not allow us to use all of them. |

| 4 | Despite the change of language, Tatar-speaking Greeks remained orthodox. |

| 5 | S in the Table 3 refers only to pronominal subjects. |

| 6 | Table 4 is based on the oral corpus. |

| 7 | The clitics of this type generally follow the verb or precede it in case of the special syntactic or prosodic context (cf. Condoravdi and Kiparsky 2002, pp. 2–3, 5–15). |

| 8 | The example is from the archive of the Centre of Dialectology (Academy of Athens), box no. 757. I am grateful to Ms. Aksiopi Mourelatou who helped me to find it. |

| 9 | Pontic examples mentioned here without any reference are from the archives collected by Fatima Eloeva in 1989–1905 in Georgia and in the Pontic community of Leningrad/Saint Petersburg, by Vladimir Panov in 2014 in Adygea (Southern Russia) and by Maxim Kisilier in 2016–2022 in Athens and in Southern Russia. |

| 10 | Examples from Northern Greek are taken from the archive of the Minor Dialect Atlas of the Balkan languages (Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (the Kunstkamera), Russian Academy of Sciences). The data were collected in Eratyra (Western Macedonia, Greece) in 1998–2000 by Andrey Sobolev, Anna Borisova, Tatiana Zajkovskaya, Vitaly Zajkovskij and Yuri Lopashov. |

| 11 | The signs used in the Table 5 require an explanation: “+”—the feature is typical for the dialect, “−”—the feature is absent from the dialect, “+/−”—the feature is rather frequent but irregular, “−/+”—the feature may rarely appear in the dialect, “−”—the feature is absent from the dialect. “?”—the situation is not clear or the data are not reliable enough. |

| 12 | The numbers on the Figure 2 correspond to the numbers in the list of subdialects at the beginning of Section 4.5. |

| 13 | Urum examples are taken from (Garkavets 2000) and Crimean Tatar examples are borrowed from “Crimean Tatar Online Dictionary” (https://medeniye.org/en/lugat, accessed on 1 March 2022). |

| 14 | -l- is a part of a Turkic verb stem but in Rumejka it has become a part of the affix. Most verbs with Turkic root have -lévu or -évu. |

| 15 | This song was given to me by Oleksandr Demchenko who wrote it down from his grandfather Yuri Kolesnikov (born in 1922). |

| 16 | Unlike traditional Azov Greek kurvátj, which took a lot of space in the room and was used not only for sleeping but also for a wide range of activities, such as eating, cooking, parties, etc. (cf. Novik 2009, pp. 73–74), modern kravátj appeared only in Soviet times. In Russian kravátj is a loanword from Byzantine Greek (κραβάτιον /kravátion/), and in the 20th century Azov Greeks borrowed the word together with the object it denotes. |

| 17 | The story refers to the Second World War. |

References

- Andriotis, Nikolaos P. 1967. Ετυμολογικό λεξικό της Κοινής Νεοελληνικής [Etymological dictionary of Modern Greek], 2nd ed. Thessaloniki: Institute of Modern Greek Studies [Manolis Triandaphyllidis Foundation], (In Modern Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Animitsa, Gennadiĭ, and Maxim Kisilier. 2009. Istoriia Urumeev. Khronologiia osnovnykh sobytiĭ (1771–2003) [History of Urums and Rumejs. Chronology of main events (1771–2003)]. Chapter 1. In Lingvisticheskaia i etnokulturnaia situatsiia v grecheskikh selakh Priazov’ia. Po materialam ekspeditsiĭ 2001–2004 godov [Language and Ethno-Cultural Situation in Greek Villages of Azov Region. Field Research Data Collected in 2001–2004]. Edited by Maxim Kisilier. Saint-Petersburg: Aletheia, pp. 25–64. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Animitsa, Gennadiĭ, N. Balaban, Ivan Zgara, L. Zhigil’, M. Madina, Tatiana Nicheporenko, E. Sedletskaia, S. Temir, and Vasiliĭ Haia. 2003. Rumeĭsko-russkiĭ slovar’ [Rumejka-Russian Dictionary]. Volodarskoe and Kyiv: Greek Societies of the Villages Cherdakli, Kremenivka and Kas’anovka. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Aradzhioni, Margaryta. 1998. K voprosu ob etnolingvisticheskoĭ situatsii v Krymu v XVI–XVIII vv. [About etholinguistic situation in the Crimea in 16th–18th centuries]. Zapiski istoriko-filologicheskogo tovarishchestva A. Beletskogo [Notes of the Historical and Philological Association of Andrey Beletskiy] 2: 70–86. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Ashla, Alexander. 1999. Τα Μαριουπολίτικα. Τραγούδια, παραμύθια και χοροί των Ελλήνων της Aζοφικής [The Dialect of Mariupol. Songs, Fairy Tales, and Dances of Azov Greeks]. Athens and Ioannina: Dodoni, (In Modern Greek and Rumejka). [Google Scholar]

- Baranova, Vlada, and Ksenia Viktorova. 2009. Rumeiskiĭ iazyk v Priazov’e. Sotsiolingvisticheskiĭ ocherk [Rumejka in the Cis-Azov region. Sociolinguistic essay]. Chapter 4. In Lingvisticheskaia i etnokulturnaia situatsiia v grecheskikh selakh Priazov’ia. Po materialam ekspeditsiĭ 2001–2004 godov [Language and Ethno-Cultural Situation in Greek Villages of Azov Region. Field Research Data Collected in 2001–2004]. Edited by Maxim Kisilier. Saint-Petersburg: Aletheia, pp. 97–112. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Baranova, Vlada. 2010. Iazyk i etnicheskaia identichnost’: Urumy i rumei Priazov’ia [Language and Ethnic Identity: Urums and Rumejs of the Cis-Azov Region]. Moscow: HSE University Publishing House. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Baranova, Vlada. 2017. Local language planners in the context of Early Soviet language policy: The case of Mariupol Greeks. Revue des études slaves 88: 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beletskiy, Andrey A. 1964. Rezul’taty dvuiazychiia v govorakh rumeĭskogo iazyka na Ukraine (tiurkizmy rumeĭskogo iazyka) [Results of bilingualism in Rumejka idioms in Ukraine (loans from Turkic)]. In Proceedings of the Conference “Current Issues of Contemporary Linguistics and Linguistic Heritage of Yevgeny D. Polivanov”. Absracts of the Linguistic Conference, 9–15 September 1964. Edited by Leonid Roisenson and Aleksandr Khaiutin. Samarkand: Samarkand State University of Ali-Shir Nava’i, vol. 1, pp. 120–22. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Beletskiy, Andrey A. 1969. Grecheskie dialekty iugo-vostoka Ukrainy i problema ikh iazyka i pis’mennosti [Greek dialects of South-East Ukraine and the problem of their language and alphabet]. Uchenye zapiski LGU [Memoirs of Leningrad State University] 343: 5–15. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Björck, Gudmund. 1940. HΝ ΔΙΔAΣΚΩΝ: Die Periphrastischen Konstruktionen im Griechischen. O. Harrassowitz (Skrifter utgivna av K. Humanistiska Vetenskaps-Samfundet i Uppsala 32. 2). Uppsala and Leipzig: Almqvist Wiksells Boktryckeri-A.-B. [Google Scholar]

- Blass, Friedrich, and Albert Debrunner. 1990. Grammatik des Neutestamentlichen Griechisch, 17th ed. Edited by Fredrich Rehkopf. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, Otto. 1874. Über die Griechischen-türkische Mischbevölkerung von Mariupol. Nach W. Grigorowitsch’s Bemerkungen über die Sprache der Taten. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 28: 576–83. [Google Scholar]

- Borisova, Anna. 2009. Mestoimennyĭ povtor dopolneniia [Clitic doubling]. Chapter 13. In Lingvisticheskaia i etnokulturnaia situatsiia v grecheskikh selakh Priazov’ia. Po materialam ekspeditsiĭ 2001–2004 godov [Language and Ethno-Cultural Situation in Greek Villages of Azov Region. Field Research Data Collected in 2001–2004]. Edited by Maxim Kisilier. Saint-Petersburg: Aletheia, pp. 394–402. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Fyodor (Friedrich). 1890. Mariupol’skie greki [Greeks of Mariupol]. Zhivaia starina [Living Antiquity] 2: 78–92. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz, Oda, and Wilfried Fiedler. 1987. Albanische Grammatik. Leipzig: VEB Verlag Enzyklopädie. [Google Scholar]

- Caragounis, Chrys C. 2004. The Development of Greek and the New Testament: Morphology, Syntax, and Textual Transmission. Wissenschsftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament 167. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidaki, Aspasia. 1997. H Ελληνική διάλεκτος της Μαριούπολης. Διατήρηση ή μετακίνηση [Greek dialect of Mariupol. Preservation or shift]. In «Ίσχυρες» και «ασθενείς» γλώσσες στην Ευρωπαϊκή Ένωση. Όψεις του γλωσσικού ηγεμονισμού [“Strong” and “Weak” Languages in the European Union. Aspects of Linguistic Hegemonism], Proceedings of the International Conference. Thessaloniki, 26–28 March 1997. Edited by Anastassios-Fivos Christidis. Thessaloniki: Centre for the Greek Language, vol. 2, pp. 517–24, (In Modern Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Chekhov, Anton P. 1936. Ι χοριάτες [Peasants]. Mariupol: Greek Publishers of Donbas. (In Rumejka) [Google Scholar]

- Chernykhin, Evgen, Tymur Horbach, Olexij Kupchenko-Grinchuk, and Valentina Los’. 2014. Arkhiv ukraїnskykh filologiv A. O. Biletskogo i T. M. Chernyshovoї u fondakh Instytutu rukopysu Natsional’noї biblioteky Ukraїнy imeni В. І. Vernadskogo: Biografiche doslidzhennia [Archive of the Ukrainian Philologists Andey Beletskiy and Tatiana Chernysheva in the Stock of the Institute of Manuscripts of the National Library of Ukraine: Biographic Research]. Scholarly Catalogue. Kyiv: National Library of Ukraine. (In Ukrainian) [Google Scholar]

- Chernysheva, Tatiana. 1958. Novogrecheskiĭ govor sël Primorskogo (Urzufa) i Ialty, Pervomaĭskogo raĭona, Stalinskoĭ oblasti (istoricheskii ocherk i morfologiia glagola) [Modern Greek Dialect of the Villages Promorskoe (Urzuf) and Yalta in Pervomaïsky District of the Stalin Region (Historical Outline and Verb Morphology)]. Kyiv: Taras Shevchenko State University of Kyiv Publishers. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Chernysheva, Tatiana. 1959. Grecheskiĭ glossariĭ F. A. Khartakhaia [Greek glossary by Teoctist Khartakhay]. Visnyk Kiïvs’kogo universytetu. Seriia filologiï ta zhurnalistyky. Movoznavstvo [Bulletin of Kyiv University. Series of Philology and Journalism. Linguistics] 2: 113–24. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Christidis, Anastassios-Fivos, ed. 2007. A History of Ancient Greek. From the Beginnings to Late Antiquity. Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Cape Town, Singapore and São Paulo: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christou, Haido. 2007. Γλωσσική συρρίκνωση στην Κριμαιοαζοφική διάλεκτο (Ιστορικοκοινωνικό πλαίσιο—Επαφή με την Κοινή Νεοελληνική—Επιπτώσεις στο αρχαϊκό λεξιλόγιο) [Linguistic Contraction in Crimean Azov Dialect (Sociohistorical Framework—Contacts with Standard Modern Greek—Impact on Archaic Vocabulary]. Mariupol: Mariupol State University, (In Modern Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Comrie, Bernard. 1980. Morphology and word order reconstruction: Problems and prospects. In Historical Morphology. Trends in Linguistics. Studies and Monographs 17. Edited by Jacek Fisiak. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Condoravdi, Cleo, and Paul Kiparsky. 2002. Clitics and clause structure. Journal of Greek Linguistics 2: 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dawkins, Richard M. 1942. The dialects of Modern Greek. Transactions of the Philological Society 39: 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetriou, Amphyction. 1933. Aλφαβητάριο για τα σκολία τον ιλικιομένον τις πρότις βαθμίδας [Primer for Adult Schools of the First Grade]. Mariupol: Ukrainian State Publishers for Ethnic Minorities, (In Demotic Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulo-Rionis, Aleko, Dmitriĭ Demerdzhi, A. Davydova-Diamantopoulo, Anton Shapurma, Raisa Kharadabot, and Donat Patricha. 2006. Rumeisko-russkiĭ i russko-rumeiskiĭ slovar’ piati dialektov grekov Priazov’ia [Rumejka-Russian and Russian-Rumejka Dictionary of Five Dialects of Azov Greeks]. Mariupol: Typography “Novyĭ Mir”. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Drettas, George. 1999. Ergative versus accusative structure: The case of Pontic Greek in a typological perspective. Mediterranean Language Review 11: 90–117. [Google Scholar]

- Eloeva, Fatima A. 2004. Pontiĭskiĭ dialekt v sinkhronii i diakhronii [Pontic Dialect in Synchrony and Diachrony]. Saint-Petersburg: Saint-Petersburg State University. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Fedchenko, Valentina. 2010. Stefan Sakhlikis. Formirovanie kritskogo poeticheskogo koine [Stephan Sakhlikis. Formation of the Cretan poetic koiné]. In Poetika traditsii [Poetics of Tradition]. Edited by Yaroslav Vassilkov and Maxim Kisilier. Saint Petersburg: Evropejskij Dom Publishers, pp. 258–74. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Fotiadis, Konstantinos. 1990. O Ελληνισμός της Κριμαίας. Μαριούπολη, δικαίωμα στη μνήμη [Hellenism in the Crimea. Mariupol, Right for Memory]. Thessaloniki: Herodotos, (In Modern Greek). [Google Scholar]

- Garkavets, Oleksandr. 2000. Urums’kyĭ slovnyk [Urum Dictionary]. Alma-Ata: Baur. (In Ukrainian) [Google Scholar]

- Grigorovich, Viktor. 1874. Zapiska antikvara o poezdke ego na Kalku i Kal’mius, v Korsunskuiu zemliu i na iuzhnye poberezhia Dnepra i Dnestra [Notes of Antiquarian about his journey to Kalka and Calmius, to Corsun and South Banks of Dnieper and Dniester]. Odessa: Typography of I. Frantsov. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]