Abstract

Language teachers struggle to shift from monolingual ideologies and pedagogical practices, as advocated for in the promotion of multilingualism and inclusive pedagogy. Additionally, the role of English as a multilingua franca pushes English teachers to rethink their beliefs about the language and its use. Even when positive about multilingualism, teachers are often uncertain of how to address the complexities of multilingual ideals due to varying contextual factors and a lack of practical knowledge and skills. This study reports on English teachers’ (N = 110) language beliefs and self-reported practices in linguistically diverse classrooms in Norway based on an online survey. We applied factor analysis to investigate if any demographic factors influenced the results. A complexity paradox emerged in which the teachers’ acceptance of multilingual ideals was contradicted by their beliefs and teaching practices, which reflected monolingual ideologies. Teacher age, learner age group, and teacher gender were important factors in the respondents’ beliefs. The discussion suggests why various factors may influence teachers and explores the complexity of their multifaceted ecologies. We conclude with recommendations for practitioners and researchers.

1. Introduction

To capitalize on the richness of the multilingual and multicultural communities that are expanding in many regions of the world and to promote inclusiveness, many societies position multilingualism as a goal. In particular, schoolchildren are tasked with gaining multilingual competence through the acquisition of several languages. Still, researchers often debate the cognitive, social, and economic benefits of multilingualism, including building equity and promoting social justice (Berthele 2021; Beisbart 2021; Bialystok 2016; Jessner 1999, 2008; Cenoz 2003). Research and policy have encouraged and promoted the local adaptation of inclusive multilingual pedagogy as beneficial for individuals and society (European Commission 2017, 2018a; Cenoz and Gorter 2022; Rokita-Jaśkow and Wolanin 2021; Chumak-Horbatsch 2019; Sifakis and Bayyurt 2018). Yet, teachers still struggle to enact multilingual ideals in schools due to varying contextual factors, the need for increased knowledge and skills, and a lack of teaching and assessment tools that position multilingualism as a resource (Alisaari et al. 2019; Rodríguez-Izquierdo et al. 2020; Bayyurt et al. 2019; Erling and Moore 2021). The multilingual turn (May 2013) described in Western applied linguistics discourse questions monolingual views of language, pushing against long-standing monolingual and monoglossic ideologies in society and education. Fluid and dynamic views on language and communication have emerged as a result (Berthele 2021; García and Wei 2014), and there are calls for 21st-century skills and education experts who can adapt to the challenges of an evolving and complex future (Bransford et al. 2005). Furthermore, scholars have discussed new perspectives on the English language due to the expansive use of English as a multilingua franca (ELF; Jenkins 2015). ELF is an inherently multilingual means of communication involving people from different linguacultural backgrounds, each with unique multilingual language repertoires (Cogo et al. 2022; Seidlhofer 2018; Mauranen 2018; Jenkins 2017). Still, the teaching of English continues to be dominated by the ideals of the past, monolingual ideologies, and colonial perspectives of nation-states (García et al. 2021; García 2019). Learning objectives, teaching materials, and assessment protocols also typically position the “native speaker” as the measuring stick of English proficiency and success (Douglas Fir Group 2016; Sifakis 2017).

1.1. Multilingualism

Multilingualism is defined as “the acquisition and use of two or more languages”(Aronin and Singleton 2008, p. 2). Studied in many fields, including linguistics, socio- and psycholinguistics, and education, multilingualism can be addressed from two perspectives: that of the individual, or one’s ability to use languages, and that of society, or how languages are used within and across societal groups. Defining language, explaining how language is housed in the mind, and what boundaries separate languages (if any) are centrally debated matters in this field (see Berthele 2021 for an overview). Scholars have put forth many terms to describe the varying conceptualizations of multilingualism and multilingual communication, including plurilingualism (Council of Europe 2001), metrolingualism (Otsuji and Pennycook 2009), languaging (Jørgensen 2008), heteroglossia (Bailey 2007), and translanguaging (García and Wei 2014). Atomistic stances conceptualize languages as discrete, separate entities and multilingualism as additive (e.g., L1 + L2 + L3). In turn, holistic views conceptualize individuals’ complete linguistic repertoire as a qualitatively unique whole. They describe language as a repertoire of codes and resources that influence one another, intersect, and gain meaning through negotiated social practices (García 2009). This includes complex dynamic systems theorists, who see language as a process rather than a state (De Bot et al. 2015; Herdina and Jessner 2002), and languaging and translanguaging proponents. Languaging considers the contextualized social nature of language use as an activity, rather than as a system or a product (Pennycook 2010), while translanguaging posits that language consists of dynamic resources that comprise an integrated semiotic system creatively used by individuals in their identity development (García and Otheguy 2020; Cenoz and Gorter 2020; Leung and Valdes 2019; Canagarajah 2011).

Translanguaging has relevant conceptual, theoretical, pedagogical, and practical merits, which are actively discussed by researchers and practitioners. The translingual paradigm considers “the deployment of a speaker’s full linguistic repertoire without regard for watchful adherence to the socially and politically defined boundaries of named, national and state languages” (Otheguy et al. 2015, p. 81) and pushes back against previously accepted language usage norms (Poza 2017). With transformative roots, this paradigm redefines language from a perspective that promotes changes to sociopolitical structures that limit and exclude multilinguals and multilingual practices (García and Otheguy 2020; García and Wei 2014). Further, pedagogical translanguaging is a theoretical and practical application of translanguaging in educational settings. It is the use of two or more languages for pedagogical purposes with the goal of promoting multilingualism as a resource (Cenoz and Gorter 2020, 2022).

1.2. English as a Lingua Franca

Positioned under the umbrella of multilingualism, current scholarship on ELF is concerned with the widespread use of English as the “global default lingua franca” (Mauranen 2018, p. 7). Globally, ELF is used extensively in multilingual contexts, more often by non-native multilingual speakers than by native monolingual speakers. Unlike other lingua francas, English is used by individuals of all educational and socio-economic statuses to communicate in every possible sphere of livelihood in all corners of the globe (ibid.). Such breadth and depth of English use and the immense global interest in learning English uniquely positions the language. Moreover, ELF researchers question limiting the ownership of English to a few inner-circle countries and the long-standing focus on standardized English as the goal in teaching (Seidlhofer 2018; Holliday 2015). Rather, all users of English are suggested to have equal rights and opportunities to use and claim ownership of the language, regardless of their origin or background (Widdowson 1994, 2003). With such evolving views on the English language and the multilingual nature of its use, researchers and English language educators seek practical solutions for teaching and learning English in our globalized, interconnected world (Rose et al. 2021; Cogo et al. 2022; Bayyurt and Dewey 2020; Callies et al. 2022). One proposal is ELF-aware teacher education and pedagogy, which aims to challenge “teachers’ deep-seated convictions about language, communication and teaching” (Bayyurt and Sifakis 2015, p. 55). This is done by raising awareness and critically considering issues addressed by ELF research, including awareness of language and language use, instructional practice, and learning. From an ecological perspective, ELF-aware teaching practices and products (e.g., curricula, teaching materials, assessment) mindfully consider the whole learning environment, including contextual factors specific to the situation and various teaching constraints (Sifakis 2017).

Nevertheless, as teachers encounter the ideological notions of multilingualism and ELF and are encouraged to implement them in their teaching and assessment, many struggle to alter established practices and norms. They must synthesize evolving discourses found in policies and guidelines, such as changes in the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) first published in 2001 and revised in 2020 (Council of Europe 2001, 2020). For example, the revised CEFR emphasizes that the “idealized native speaker” was not the point of reference for the development of the new proficiency levels, while acknowledging that the 2001 levels had a native-speaker focus. Researchers and teacher educators have proposed that increased knowledge of multilingualism and multilingual pedagogy can lead to sustainable change if adapted to local teaching contexts (Hult 2014; Hornberger and Johnson 2007). However, not all agree on the specifics of what knowledge and skills are needed and how to promote multiple languages in meaningful and pedagogically beneficial ways (Leung and Valdes 2019; De Angelis 2011). Teachers also remain uncertain about how to address the complexities of this ideological shift due to varying contextual factors and constraints, as well as a lack of practical knowledge and skills (Bayyurt et al. 2019; Alisaari et al. 2019; Sarandi 2020; Dewey and Pineda 2020; Choi and Liu 2020; Yuvayapan 2019; Lopriore 2015).

1.3. Language Teacher Cognition

The theoretical frame used very often in language teacher education is language teacher cognition, or “what language teachers know, think, and do” (Borg 2003, p. 81). Language teacher cognition is theorized as emergent, situated, and woven into the complex contexts in which teachers are found and participate dynamically (Kubanyiova and Feryok 2015; Burns et al. 2015; Li 2020). This work takes a situated and ecological perspective of language teacher cognition, with a focus on what teachers do, why they do this, and the implications this has for learning from a bottom-up view. The goal is to identify “salient dimensions of language teachers’ inner lives” (Kubanyiova and Feryok 2015, p. 436). Formed early and resistant to change, teacher beliefs are often explored as one facet of language teacher cognition, characterized frequently as tacit, evaluative, and affective. Teachers’ beliefs are intertwined with their classroom experiences as learners and as practitioners (Burns et al. 2015; Borg 2006; Pajares 1992), and likewise, their beliefs deeply affect and influence their teaching practices (Borg 2009; Burns et al. 2015). The relationship is reciprocal in that teacher beliefs are influenced by teachers’ classroom experiences (past and present, as learners, student teachers, and as teachers), while their beliefs also influence their classroom practices. However, a straightforward relationship between teachers’ beliefs and actual classroom practices has not been found due to the complexity of the concept, how it is researched, and the multitude of factors that influence teaching practices (Pajares 1992). Further, research has described an interplay between belief sub-systems, one in which early-formed, stable core beliefs, often gained via experience, influentially compete with newer peripheral beliefs in decision-making in the classroom (Phipps and Borg 2009; Pajares 1992). For example, many teachers experienced British English as the preferred learning target for English education during their schooling, teacher education, and teaching practices at their schools, which may strengthen a core belief and choice to teach standard British English. Moreover, many teachers develop peripheral beliefs that are contradictory, such as knowledge and understanding of multilingualism as a positive phenomenon and the pervasive use of English in multilingual communication.

1.4. Previous Research in Norway

In Norwegian schools, an inclusive learning environment that recognizes diversity and multilingualism as a resource is required by law and stated in the National Curriculum (Utdanningsdirektoratet 1998, 2020a). Moreover, the Curriculum in English (Utdanningsdirektoratet 2020b) asserts that learners should be able to communicate with people locally and globally in English, as a lingua franca, irrespective of linguistic or cultural background. The curriculum thus grants ideological and implementational spaces (Hornberger 2002) for multilingual, ELF-aware perspectives. Research from Norway has found that English teachers generally have positive attitudes toward multilingualism and multilingual learners (Krulatz and Dahl 2016; Burner and Carlsen 2019; Calafato 2020; Haukås 2016; Angelovska et al. 2020). Yet, they require raised linguistic awareness and knowledge of multilingualism and multilingual pedagogy (Šurkalović 2014; Krulatz and Dahl 2016; Burner and Carlsen 2019; Flognfeldt et al. 2020; Iversen 2017), since monolingual ideologies are prevalent in Norwegian English teachers’ beliefs and practices (Flognfeldt et al. 2020; Flognfeldt 2018; Angelovska et al. 2020). Elite forms of multilingualism (Ortega 2019) are often promoted as well, mainly Norwegian–English bilingualism, while minoritized languages are not systematically included to promote multilingualism as a resource (Beiler 2020, 2021; Burner and Carlsen 2017; Iversen 2017; Christison et al. 2021; Haukås 2016). Rather, Norwegian is used regularly in English classes to ensure inclusion through sameness and avoid exclusion in using unknown migrant languages (Beiler 2021; Brevik and Rindal 2020; Flognfeldt 2018; Flognfeldt et al. 2020; Iversen 2017; Haukås 2016).

1.5. Aim of the Study

This study focuses on teacher beliefs about language within the evolving multilingual space in Norway. We inquired into teachers’ beliefs and self-reported practices about the English language and how English is used in the schoolroom and in teaching and assessment resources. Further, we analyzed which demographic factors may influence their cognition through ordinal regression statistical analysis. The aim of this study is to set a baseline and expose factors that influence cognition. The following research questions guided our work:

- What are English teachers’ beliefs and self-reported practices about the English language and English language use when teaching in multilingual classrooms in Norway?

- What factors influence English teachers’ beliefs and self-reported practices about the English language and English language use when teaching in multilingual classrooms in Norway?

The results of this study highlight the complexity of English teachers’ beliefs and practices in Norway’s diverse multilingual context. They may provide valuable insight for teacher educators, especially in planning pre- and in-service teacher education programs; policymakers in considering how teachers may meet and enact new educational policies; and researchers in planning further work about the beliefs of language teachers and their interplay with teaching and learning.

2. Research Design and Methodology

2.1. Methods

This study examined English teachers’ beliefs and self-reported practices from data collected in Norway in fall 2018 using an online, self-administered survey (Borg 2012; Sundqvist et al. 2021). The survey was linked to an Erasmus+ project, titled ENRICH: English as a Lingua Franca Practices for Inclusive Multilingual Classrooms (EU funded, grant: 2018-1-EL01-KA201-047894). It was collaboratively developed by the consortium members during the project’s needs analysis phase (Long 2005; see description in Lopriore 2021). The results informed the development of the ENRICH Course (see http://enrichproject.eu/). The Norwegian Centre for Research Data and corresponding bodies at partner institutions were consulted to confirm all necessary steps were taken to adhere to research ethics. Accordingly, the survey was made anonymous; we did not gather IP addresses during data collection, and data were stored securely. The participants were provided information about the purpose of the study and the protection of their collected data, and all gave consent to participate voluntarily.

The survey instrument was developed according to the traditions of questionnaire design found in applied linguistics (Dörnyei and Taguchi 2010) to capture information about teacher beliefs and practices, the multilingual context, background information, and learning experiences and needs. A literature review of key concepts informed the development of items, including multilingualism (e.g., Aronin and Singleton 2008; Martin-Jones et al. 2012; Cenoz 2003; Blommaert 2010); English as a lingua franca (e.g., Seidlhofer 2011; Jenkins et al. 2011; Mauranen 2006); language teaching and learning, such as the CEFR and its companion volume (Council of Europe 2001, 2020); teacher effectiveness, such as the Eurydice report (European Commission 2018b); and effective teacher education (e.g., Padwad and Dixit 2011; Richards and Farrell 2005; Vázquez 2016), including ELF awareness in English teacher education (Sifakis 2014, 2017; Sifakis and Bayyurt 2018). The instrument was piloted with stakeholders as a validation step before being distributed to teachers of English (Dörnyei and Taguchi 2010). Our study reports on 32 items from the original 43-item instrument. These items were chosen due to their relevance to our research questions inquiring about the beliefs and practices of English use in relation to teaching and include 6 items about demographics, 5 items about the characteristics of the multilingual context, and 22 items about teacher beliefs and self-reported teaching practices (see items in Appendix A). Non-probability sampling was utilized in a call for participation sent via email to the National Academic Council for English Studies, alumni of English teacher education courses, and professional and personal contacts. Posts were also made on several social media forums for teachers in Norway, as were announcements and presentations at several conferences for educators.

2.2. Data Analysis

The statistical analyses performed were descriptive statistical analysis and ordinal regression analysis for dependent variables measured using an ordinal scale and logistic regression analysis for dichotomous dependent variables. The participants’ demographic details were used as predictors in the regression analyses. The factors included age, gender, education, L1, learner age group, if they were aware that people with different language backgrounds live in Norway, if they knew the language education policies, if their school supported the social integration of learners with migrant backgrounds, and the percentage of multilingual learners in their classroom.

2.3. Research Context

The research context was Norway, where there has been an influx in migrants with diverse backgrounds in the past few decades. In 2021, 18.5% of the population had an immigrant background (Statistics Norway 2021a), and approximately 220 languages were represented in the population’s linguistic profile (Svendsen 2021). Schools reflect this diverse reality, and while no national statistics exist, 35% of the pupils in the Oslo school district had a linguistic minority background in 2020–2021 (Oslo Kommune Statistikkbanken 2021). Regarding language policy, Norway’s Language Act (Lov om språk), enacted in 2022, positions Norwegian as the “main national language” (Kulturdepartementet 2021, §4). In part, the act attempts to push back against the abundant use of languages other than Norwegian in society, particularly English (Språkrådet 2021). Special rights are granted to indigenous and minority languages in response to assimilation practices during nation building, as well as Scandinavian languages with historical ties to Norway.

The National Curriculum for basic education is the guiding document for educators and outlines competency aims and outcomes by subject and grade level. Teachers largely have autonomy to use learning materials and teaching methods they deem appropriate to meet these aims. Still, textbooks and published teaching resources are commonly purchased for entire school districts or schools. Our data were collected when Norway’s LK06 National Curriculum was in effect (Utdanningsdirektoratet 2013). Under that curriculum, English was described as an international language needed for communication with people from other countries. Learning English was to “contribute to multilingualism” and personal development (ibid., p. 2). A new National Curriculum, LK20, was introduced in August 2020. LK20 positions multilingualism as a resource and describes English from an ELF-aware perspective. Learners should gain an appreciation of linguistic diversity and its benefits, develop their linguistic identity, and “experience that being proficient in a number of languages is a resource, both in school and society at large” (Utdanningsdirektoratet 2020c, p. 5). LK20 also describes the role of English in a global society as necessary for knowledge growth, to participate in activities, and for employability in the 21st century. Further, learners should be able to use English “both locally and globally, regardless of cultural or linguistic background” (Utdanningsdirektoratet 2020b, p. 2).

English is the first foreign language taught from grade 1 in Norway, with a second introduced later, most often in lower secondary school. Teachers in basic education in Norway are often educated as semi-specialists qualified to teach two to four school subjects. To qualify to teach English, teachers are required to complete relevant coursework in English language pedagogy (i.e., 30 ECTS for grades 1–7 or 60 ECTS for grades 8–13). Markedly, English is the core subject taught most frequently by un-/under-qualified teachers, with as many as half of all English teachers in Norway not holding the required qualifications (Perlic 2019). Still, the more hours a teacher instructs in the subject per week, the more qualified they tend to be, with 26% of English teachers qualified who teach one hour per week and 82% qualified who teach five or more. The greatest lack of English teaching qualifications is in grades 1–4, where 64% of teachers had no qualifying coursework in 2018, and only 32% were fully qualified. In grades 5–7, 44% held full qualifications and 76% in grades 8–10 (ibid.). In response, a large-scale national strategy was started in 2014, Lærerløftet (Teacher Lift), to increase the qualifications of teachers in key subjects. This has aided over 1000 teachers of English per year to gain formal qualifications through continuing education programming, such as Kompetanse for Kvalitet (Competence for Quality).

2.4. Participants

There were 110 participants in this study. Table 1 provides information about their backgrounds, including gender, education, L1, age range, and the age group of their learners. The relevant BA/MA degrees listed in the survey were English language teaching, teacher education, English studies, or similar topics. In the survey, no inquiry of ECTS credits in English pedagogy was made. The participants’ education level is representative of teachers of basic education in Norway, with 14% having an MA in 2020 (Statistics Norway 2021b).

Table 1.

Participant demographic information.

The respondents all reported competencies in Norwegian and English and indicated the following languages as their L1: Norwegian (95), English (5), German (3), Icelandic, Punjabi, Swedish, Greek, Russian, Spanish, Latvian, and French (1 each). This indicates a higher percentage of respondents who had a linguistic minority background (L1 other than Norwegian) than is found in Norway’s general teacher population (13.6% vs. 7.5%; Statistics Norway). Many respondents reported competencies in multiple languages, with 83 (75.5%) being proficient in at least three languages and 50 (45.5%) in four or more. The most common language competencies were German (49), French (38), and Spanish (19), followed by Swedish and Italian (6 each); Arabic and Russian (3 each); Portuguese, Icelandic, and Sami (2 each); and Berber, Latvian, Frisian, Dutch, Danish, Greek, Czech, Urdu, Punjabi, and Irish Gaelic (1 each).

Regarding the participants’ context, 92 (83.6%) reported that they currently teach multilingual learners, and 104 (94.6%) were in agreement that people with different language backgrounds live in Norway. The average number of multilingual learners in the respondents’ English classes varied, reflecting differences found across schools: 0–25%: 57 (51.8%); 26–50%: 21 (19.1%); 51–75%: 11 (10%); and 76–100%: 21 (19.1%). While no national statistics exist, these numbers are similar to those available for the Oslo school district for multilingual learners: 0–25%: 55 (40.7%); 26–50%: 34 (25.2%); 51–75%: 26 (19.3%); and 76–100%: 20 (14.8%; Oslo Kommune Statistikkbanken 2021). These results indicate that the teachers are aware of their learners’ multilingual backgrounds and that they have varying numbers of multilingual learners in their classes.

Finally, 105 (95.5%) participants reported knowing Norway’s language educational policies, and 69 (62.7%) stated that their school supports the social integration of learners with migrant backgrounds through special programs and/or events. Such results can be explained by the role educational policies, mainly the National Curriculum and Educational Act, play in guiding education in Norway. Further, schools have legal obligations to support all learners and do so via various means at different schools and school districts, such as introductory classes for newly arrived migrants or bilingual teacher assistants. Noteworthy criticism has arisen as to the underlying premise of some of these programs, particularly that they are more political than pedagogical (Burner and Carlsen 2017).

3. Results

We report the results according to themes as they emerged from the analysis of the questions included in the survey (Braun and Clarke 2012; Hsieh and Shannon 2005). This process was carried out in two stages. First, the questions were tagged according to the themes that emerged, and preliminary categories were created (Miles et al. 2019). Then, some of the themes were replaced by researcher-generated ones to achieve a more coherent description of the topics identified. The researchers separately undertook the analysis and organization of the themes to enhance cross-verification, with differences jointly discussed and the themes finalized thereafter (see survey Appendix A with survey items and themes).

3.1. Teacher Beliefs and Reported Practices

3.1.1. Teacher Beliefs about English Use

The teachers’ beliefs about English use in teaching practices are presented in Table 2. The participants were uncertain if native speaker norms are desirable for English teachers or preferred by learners. The teacher responses spread across the middle of the scale on Q30 and Q33, indicating many were uncertain of their beliefs. However, we observed a general agreement about non-native English-speaking teachers and uses of English as good and acceptable in teaching in Q31 (94% agreement), Q32 (91%), Q39 (70%), and Q36 (72%). Such results indicate positive beliefs regarding non-native users and uses of English, which are deemed valid and suitable for teaching and point to a heightened awareness of ELF within their contexts. Still, we detected tension between uncertainty toward native speaker norms and validation of non-native speaking norms. On the one hand, the teachers were unable to dismiss native speakers as the most preferred or suitable model to learning English, indicating that a standard, monolingual language orientation remains in their beliefs. On the other hand, the teachers were welcoming toward non-native teachers, accents, and uses of English, validating their work as non-native teachers of English and their learners’ use of English as non-native speakers. Such beliefs convey more fluid perceptions of language and communication, as found in multilingual language ideologies.

Table 2.

Teacher beliefs about English use in teaching practices.

3.1.2. Teacher Beliefs and Practices about English Use in Assessment

The teachers’ beliefs about the use of English in assessment and feedback practices indicated some uncertainty or conflicting beliefs among them (see Q37 and Q38 in Table 3). These results may indicate that many teachers have not previously considered such practices or that they remain uncertain of if or how such practices should be incorporated into assessment and feedback. Likewise, this may reflect misperceptions of the terms used in the survey items. Assessment is commonly used as an overarching term for testing, assessments, and/or feedback, whereas tests are commonly defined as measurements of language proficiency at a given time, where accuracy and errors are key concepts. Alternative assessment refers to measuring overall communicative skills attained across time and often gathered in extended samples (Kouvdou and Tsagari 2018). We observed no clear tendency in beliefs about the role of a teacher in error correction (Q34), with responses spread across the middle points of the scale. A number of the teachers (Q37, 54%; Q38, 48%) were in agreement that tests should include interactions involving non-native users of English and that assessment should focus on intelligibility, but still, over one-third (Q37, 38%; Q38, 36%) were undecided about their beliefs on these issues. Regarding alternative assessment (Q23), 70% reported they sometimes or often incorporate such practices, which suggests most teachers are familiar with and practice alternative assessment. Indeed, the Norwegian educational authorities (Utdanningsdirektoratet n.d.) advocate for alternative assessment, as do researchers of multilingualism and ELF, who push forth a focus on communicative practices rather than native-speaker norms (Kouvdou and Tsagari 2018).

Table 3.

Teacher beliefs and practices about English use in assessment.

3.1.3. Teachers’ Self-Reported Practices for English Use

The teachers’ self-reported practices for English use in teaching indicated that they believe all uses of English are beneficial to learning and that classroom learning should link to extramural uses of English (see Table 4). The respondents reported that they provide learners opportunities to use English in the classroom (Q14, 95% agreement) and expose them to English similar to its extramural uses often or always (Q18, 61%). However, contradictions in the teachers’ beliefs and reported practices did emerge regarding the teaching of standard pronunciation. While the respondents reported often/always teaching standard British or American pronunciation (Q20, 78%), they were uncertain if teachers should have native-like pronunciation and affirm non-native uses and users of English as acceptable. While the teachers are seemingly open to non-standard uses of English, they still feel teaching standard forms is central to English language teaching. The teachers also described allowing the use of languages other than English in teaching sometimes or often, (Q24, 69%). Such results could indicate a pro-multilingual perspective on language learning. However, previous research in Norwegian English classes highlighted that the regular use of Norwegian is common, but the systematic use of other languages in learners’ and teachers’ multilingual repertoires is not (Beiler 2021; Brevik and Rindal 2020; Burner and Carlsen 2017). Without further data about which languages are used, the meaning of these results is unclear.

Table 4.

Teachers’ reported teaching practices for English use.

3.1.4. Teachers’ Reported Practices for English Use in Teaching Materials and Resources

Table 5 lists the results of the teachers’ reported practices for English use in teaching materials and resources. These revealed a strong tendency to use materials and resources with native speakers (Q21, 80% often/always; Q12, 72% in agreement) and native countries and cultures (Q16, 90% in agreement), more so than materials with non-native speakers or migrant cultures (Q22, 76%; Q25, 71%—rarely/sometimes; Q13). The infrequency with which learners are exposed to non-native speakers or cultures through learning materials points to uncertainty about if this is or should be done. Further, the common practice of developing additional learning materials for multilingual learners (Q19, 61% often/always) and the strong agreement among the teachers that they should use authentic materials, (Q35, 72% agreement) suggests that the teachers believe supplementary materials are needed and/or beneficial to learning. The types of materials developed and the reasoning for doing so remain unclear from the survey results. However, teachers who have recently completed continuing education to qualify to teach English have noted a newfound freedom to break away from the confinements of textbooks after gaining confidence in using and teaching English (Lund and Tishakov 2017).

Table 5.

Teachers’ reported practices for English use in teaching materials and resources.

3.2. Factors Influencing Teacher Beliefs and Practices

Teacher age, learner age group, and teacher gender were all factors that influenced the beliefs and reported practices of the teachers about the English language and English language use when teaching in Norwegian multilingual classrooms. We did not find the native language of the respondents to be a significant factor for any items.

3.2.1. Teacher Age

Teacher age was a significant factor for several items. The tendency noted was the younger their age, the more likely the teachers were to validate the use of non-native English in teaching and learning materials; allow learners opportunities to use English in classes; and focus on intelligibility in assessment and feedback. Younger teachers were more accepting of non-native teachers as acceptable models and users of English as well (Q31). The odds of the teachers aged 26–35 years old reporting that they strongly agree that non-native teachers can be good language models were 12.9 times higher than those aged 36–45 years old (b = 2.554, Wald χ2(1) = 5.252, p = 0.022). Additionally, younger teachers were more confident users of English (Q32), where the odds to strongly agree to being comfortable with their own accent were 18.7 times higher for the teachers aged 26–35 than the teachers aged 36–45 (b = 2.930, Wald χ2(1) = 7.984, p = 0.005).

Furthermore, the younger the teacher, the more likely they allowed their learners to interact in English in the classroom (Q14). For example, the odds of the teachers aged ≤25 to strongly agree with this statement were 42.7 times higher than those aged 26–35 (b = 3.755, Wald χ2(1) = 5.826, p = 0.016) and 14 times higher for those aged 26–35 than those aged 36–45 (b = 2.645, Wald χ2(1) = 5.722, p = 0.017). Likewise, younger teachers were more likely to frequently expose learners to English similar to extramural English uses (Q18), with the odds of the teachers aged 26–35 responding always being 8.7 times higher than the teachers aged 36–45 (b = 2.162, Wald χ2(1) = 5.061, p = 0.024). Younger teachers were also more likely to frequently use learning materials that expose their learners to non-native speakers (Q25) with the odds of the teachers aged ≤25 reporting always 10 times higher than the teachers aged 26–35 (b = 2.303, Wald χ2(1) = 3.899, p = 0.048). Finally, younger teachers were more likely to agree to a focus on what is intelligible when assessing learners (Q38), with 11.5 times higher odds of the teachers aged 26–35 marking strongly agreeing than the teachers aged 36–45 (b = 2.446, Wald χ2(1) = 7.201, p = 0.007). Younger teachers had greater odds as well to be more confident users of English and have beliefs and practices that indicate pro-multilingual language beliefs. Such results suggest that younger generations of teachers may hold different beliefs about language and language teaching, about the role of ELF, native/non-native English use, and what types of English should be used in teaching and assessment practices.

3.2.2. Learner Age Group

The age group of the learners whom the respondents teach was also a significant factor for several items. We observed differences in belief sets between the teachers of young learners (aged 6–10) and the teachers of other age groups. The teachers of young learners were less likely to agree that non-native teachers are good language models (Q31), to be comfortable with their accents (Q32), and to include interactions with non-native speakers in assessments (Q37). The odds of respondents teaching learners age ≥11 to strongly agree that non-native teachers can be good language models was 4.1 times higher than those teaching ages 6–10 (b = 1.409, Wald χ2(1) = 3.885, p = 0.049), and for being comfortable with their accent, it was 5.5 times higher than those teaching ages 6–10 (b = 1.696, Wald χ2(1) = 6.146, p = 0.013). The teachers of young learners were also less likely to agree that standard tests should include non-native speakers (Q37). The odds of the teachers of other age groups to strongly agree was 4 times higher than the teachers of ages 6–10 (b = 1.381, Wald χ2(1) = 4.985, p = 0.026) and 3.4 times higher than the teachers of ages 11–13 (b = 1.226, Wald χ2(1) = 4.246, p = 0.039). However, the teachers of young learners were more likely to focus on intelligibility in assessment (Q38), with odds to strongly agree 36.8 times higher than for the teachers of ages 14–17 (b = 3.606, Wald χ2(1) = 6.401, p = 0.011) and 3.7 more than the teachers of ages 11–13 (b = 1.307, Wald χ2(1) = 4.994, p = 0.025). In contrast, the odds were greater for the teachers of other age groups than 18+ to report that they agree that their role is to correct learners’ incorrect uses of English (Q34) and that they teach standard pronunciation (Q20). The odds of the teachers of other age groups to strongly agree to error correction was 17.3 times higher (b = 2.848, Wald χ2(1) = 5.492, p = 0.019) and, to always teach standard pronunciation, 11.22 times higher (b = 2.418, Wald χ2(1) = 4.077, p = 0.043) than that of the teachers of ages ≥18.

For the teachers of young learners, a focus on intelligibility could indicate how the learners’ age, developmental level, and new experience with learning English influence teacher beliefs and reported practices. Generally, the first years of English learning in Norway are low stakes and focus on experiencing the language through play, songs, and discovery (Utdanningsdirektoratet 2020b). In turn, teachers working with the oldest schoolchildren may have different beliefs due to the learners’ age, maturity, and generally high English competence (on average B1 level; Brevik and Rindal 2020). However, a contradiction has arisen in the teachers’ focus on intelligibility in assessments and on error correction in English use, highlighting tension in teacher beliefs.

3.2.3. Teacher Gender

Teacher gender was a significant factor for two items, namely intelligibility in assessment practices (Q38) and materials development for multilingual learners (Q19). The odds of the female teachers to strongly agree that teachers should focus on assessing intelligibility was 3.3 times higher than the male teachers (b = 1.182, Wald χ2(1) = 4.045, p = 0.044). The percentage of female teachers working in primary schools in Norway is high (74.4%, Statistics Norway), so these results may be considered in light of the learner age group findings for Q38 (discussed above), where the teachers of young learners were more likely to focus on intelligibility in assessment. Furthermore, the odds of the female teachers to report always to developing materials to aid their multilingual learners was 13.9 times greater than the male teachers (b = 2.632, Wald χ2(1) = 15.860, p < 0.0005). These results indicate female teachers may be more likely to hold certain pro-multilingual beliefs, though further research is needed to confirm and explore them (Ricklefs 2021).

4. Discussion

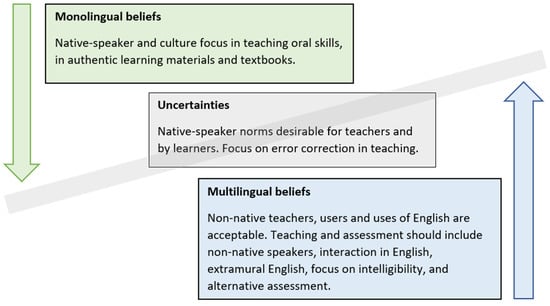

The current study aimed to gauge the beliefs and reported practices of English teachers about the English language and English language use when teaching in multilingual classrooms in Norway, as well as explore what factors influence these beliefs and practices. The findings point to tensions and uncertainties. Notably, some of the teachers’ beliefs and reported practices indicate monolingual ideologies of language, while others imply multilingual ideologies. These conflicting beliefs and practices seem to coexist paradoxically. As represented in Figure 1, the beliefs push against and overlap one another, creating tension and a gray zone of uncertainties where what the teachers believe should be practiced in teaching contradicts what they reported practicing in their own classrooms. We found prominent tension in the space given to native speaker norms in teaching practices and materials used (Flognfeldt et al. 2020; Flognfeldt 2018), as opposed to a general affirmation of non-native speakers and uses of English as acceptable and good (Angelovska et al. 2020; Krulatz and Dahl 2016; Burner and Carlsen 2019; Haukås 2016). Previous studies have found similar results of the conflicting ideologies present in teacher beliefs and practices (Ricklefs 2021; Birello et al. 2021; Kroskrity 2010; De Korne 2012).

Figure 1.

Tensions and uncertainties in English teachers’ language beliefs and reported practices in the Norwegian multilingual context.

Complex Multifaceted Ecologies

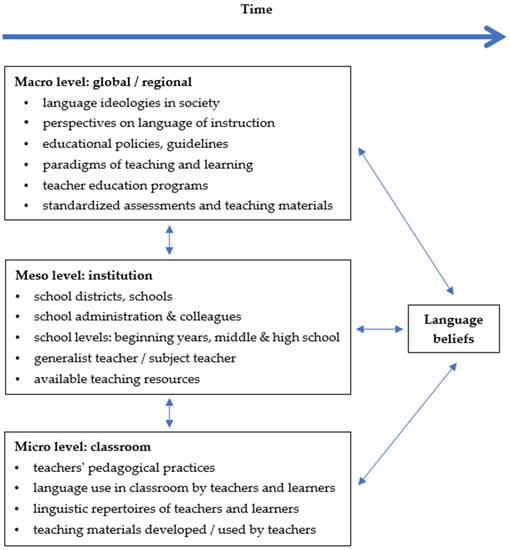

With its ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner 1979), the multifaceted nature of the language learning and teaching framework helps tease apart the complexity of language teaching, and learning. We use this framework to consider the influences on the teachers’ language beliefs within a larger structure (Douglas Fir Group 2016; De Costa and Norton 2017). Language teacher beliefs are rooted in and intertwined with the social experiences teachers have as learners, educators, and members of various groups in society (Borg 2019; Kroskrity 2010). There are many influences on teachers’ beliefs, some more salient than others, that we attempted to identify from our data, results, and discussion and sort according to the levels of the language learning and teaching framework. Figure 2 presents an overview of the mutually dependent contextual levels (macro, meso, and micro) that may influence language teachers’ beliefs and practices. It also includes time in reference to the historical context, or teachers’ past experiences.

Figure 2.

Contextual levels that impact teachers’ language beliefs.

The macro level of ideological structures considers global and regional influences with widespread impact, including the language ideologies found in society at large and the shifting perspectives of the language of instruction, such as English as an expansively used multilingua franca. Further influences are global and national educational policies and guidelines, such as the CEFR and national curriculum; paradigms of language teaching and learning, such as English-only pedagogy and communicative language teaching; teacher education programs; and standardized assessments and teaching materials, such as high-stakes tests and published textbooks. The macro level highlights a multitude of diverse and evolving ideologies that influence teachers, who must navigate them in real time to the best of their ability, according to the resources available. Our results suggest English teachers in Norway are influenced by various ideological structures to varying degrees, similar to findings presented by others (Haukås and Mercer 2021; Chvala 2020; De Korne 2012; Kroskrity 2010). Markedly, the teachers reported that they were unable or unwilling to escape the influence of monolingual language ideologies in their teaching practices. These ideologies seem to be rooted in teachers’ core beliefs on account of their long-standing dominance in both society and language education paradigms. They are further reflected in policies, teacher education programs, assessments, and teaching materials (Leung and Valdes 2019; Douglas Fir Group 2016; Canagarajah 2006; Galloway and Numajiri 2020; Galloway 2018; Callies et al. 2022). Newer and less established multilingual ideologies seem to be peripheral beliefs, more easily overlooked or canceled out by steadfast core beliefs during teaching practices. Another consideration on a regional level is linked to teacher education and qualifications, particularly the lack of teachers who hold professional qualifications to teach English in Norway. Such teachers tend to be less confident users and teachers of English and depend more on textbooks, which may adhere to monolingual language ideologies (Galloway 2018), to guide their teaching (Lund and Tishakov 2017).

The meso level considers the influence of sociocultural institutions and communities, including social identities and groups, such as the school district, school, department, or educational level within which teachers work, as well as their social identity as general or subject teachers. Likewise, the teaching resources available at a school or in a school district may affect beliefs and practices. According to our results, the teachers of grades 5 and over were more likely to hold pro-multilingual beliefs of English, which may point to differences in the focus and organization of teaching at the different levels of schooling and the teachers’ identities and qualifications. In the beginning grades, Norwegian schools are characterized by a strong focus on the development of basic numeracy, literacy in Norwegian, and social skills (Norges Offentlige Utredninger 2003; Hoff-Jenssen et al. 2020). Teachers at this level are commonly generalists who teach core subjects, including English, to one class or parallel classes. Individual teachers often instruct a few hours of English per week, and a substantial percentage do not hold the required qualifications to teach English, as noted in the section Research Context. In the middle grades, the focus of schooling shifts towards the use of literacy skills to learn various subjects. The number of hours of English instruction per week increases, and more teachers with the required qualifications teach the subject. Additionally, more identify as semi-specialist subject teachers, such as teachers of English, math, and science. Influences on teachers at various levels of schooling and their identity/qualifications as teachers at these levels may be salient in these results.

The micro level of social activity is the classroom, where teachers have the most direct impact on pedagogical and linguistic practices. At this level, the teachers’ beliefs are enacted in practice. This includes what languages are used or excluded in accordance with their beliefs about language and language learning and any constraints present, such as time pressure, teaching resources, learning outcomes, and assessment requirements. The linguistic repertoire of the teachers and learners is another available resource to draw upon, but it is often overlooked in Norway (Flognfeldt 2018; Christison et al. 2021). The participants reported allowing languages other than English in the classroom sometimes or often; however, research has found that in practice, this refers almost solely to Norwegian (Brevik and Rindal 2020). The native language of the teacher (Norwegian/non-Norwegian) was considered as a factor but was not found to be significant. These results are in agreement with the findings of Bernstein et al. (2021). Still, other research results have determined that the native language of a teacher is significant to their language beliefs (Ricklefs 2021). Additionally, researchers have identified other related factors are significant for pro-multilingual beliefs, including experience learning another language (Bernstein et al. 2021) and the number of languages instructed by a teacher (Calafato 2020, 2021). Such varying results highlight the complexity of language beliefs and the need for more research about how the richness of teachers’ linguistic repertoires and various types of experiences with learning and teaching languages may influence their language beliefs.

Lastly, the historical context considers influences across time, including the lived experiences of teachers as language learners and teacher students, generally agreed to have significant influence on language teacher cognition (Borg 2006; Li 2020). The historical context provides insight into our findings that younger teachers are more likely to favor multilingual ideologies, similar to Bernstein et al. (2021), who specified that age and years of experience are significant. Younger generations of teachers have grown up in an expanding multilingual context in Norway with vastly different experiences and opportunities to use and learn English. This is due to the expanding global use of English in recent decades and the inclusion of English as an obligatory subject in Norwegian schools from grade 1 since 1997. Furthermore, teacher education programs evolve over time, socializing generations of teachers into the profession in varying ways as epistemological changes take hold (Johnson 2009). For example, multilingualism and multilingual pedagogy have been included as topics in English teacher education in some programs in Norway since 2013. Younger generations of teachers prefer more multilingual language ideologies and seem to have a different trajectory than that of past generations.

Teachers are part of a complex, evolving multilingual ecology that has many ideological structures permeating various sociocultural institutions and communities. In this space and time, both multilingual and monolingual language ideologies diffuse into English language teachers’ beliefs and practices. Within the beliefs of individual teachers and groups of teachers, the degree of monolingual and/or multilingual language ideologies varies. Language ideologies do not neatly transfer into the cognition of individual teachers as whole set entities. Rather, teachers are influenced by various ideological structures and beliefs and all the interrelated contextual levels, and they form their own dynamic belief system that guides their classroom practices.

5. Conclusions

Our communities and schools are rich in linguistic resources, and schoolteachers are pivotal in promoting multilingualism as a resource, as called for in educational policies and by researchers. In this study, we investigated Norwegian English teachers’ beliefs about the English language and its use, and we identify factors which influence them. We found a complexity in which contradictory beliefs about language remain adjacent in the teachers’ dynamic belief sets, with a gray zone of uncertainty regarding some matters. We found teacher age, learner age group, and teacher gender to be significant factors for some beliefs. Finally, we used the multifaceted nature of the language learning and teaching framework to reflect on the mutually dependent contextual levels that influence teachers’ language beliefs. Our results suggest that teachers’ trajectories are in transition, with the language beliefs of some groups of teachers indicating pro-multilingual ideals.

While the methodology used in this study allowed for a large sample size from across Norway and statistical analysis of the results, it has some limitations. First, calls for participation were sent out by the local project team, all members of the same teacher education program, and may have resulted in many alumni responding rather than other participants. Further, we did not address meso- and micro-level contextual factors and the teachers’ reasoning behind their beliefs and practices. We also did not observe the teachers’ actual classroom practices. Finally, our analysis did not consider if proficiency in multiple languages was a factor in teachers’ beliefs. We recommend further qualitative investigation to contextualize English teachers’ language beliefs and practices at the macro, meso, and micro levels. They may investigate why different groups of teachers are more likely to favor multilingual language ideologies and can further study actual teaching practices in schools and classrooms.

As the makeup of learners diversifies, schools and educational authorities must mindfully avoid assumptions of a shared linguistic and cultural background among learners and their families. They must not overlook or downplay the richness of the semiotic and cultural resources all learners bring with them, especially those with multilingual backgrounds. As uniting spaces, schools are a key platform for the promotion of multilingualism as a resource in learning and across society and must work to stop the reproduction of standard monolingual ideologies. Considering the calls to rethink the standing of English and how language is theorized, our results may indicate such a transition has begun, if ever so gradually, among some groups of teachers. Nevertheless, continued opportunities for English teachers are needed that allow for reflection on concepts surrounding multilingualism and ELF and to try multilingual pedagogical practices in local teaching environments. Two especially relevant resources that may be used in pre- and in-service teacher education and development programs to aid in this effort include English as a Lingua Franca for EFL Contexts, an edited edition by Sifakis and Tsantila (2019) that provides empirical perspectives about ELF of particular importance to EFL teachers and stakeholders. Further, the ENRICH Course (see http://enrichproject.eu/) provides an open-access, asynchronous, continuing professional development course for EFL teachers and stakeholders. This includes short lectures and activities to guide teachers toward an understanding of English within an ELF-aware, multilingual perspective.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.T. and T.T.; methodology, D.T.; formal analysis, T.T. and D.T.; writing—original draft preparation, T.T.; writing—review and editing, T.T. and D.T.; visualization, T.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, after consultation with the Norwegian Centre for Research Data due to anonymous data collection which did not include sensitive or identifying personal data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the reported results is securely stored.

Acknowledgments

The study presented was linked to an Erasmus+ project, titled ENRICH: English as a Lingua Franca Practices for Inclusive Multilingual Classrooms (EU funded, grant: 2018-1-EL01-KA201-047894). The project was coordinated by the Hellenic Open University and included partners at: Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway; Bogazici University, Turkey; Roma Tre University, Italy; University of Lisbon, Portugal; Computer and Technology Institute, Greece. We acknowledge the project consortium members for the development of the survey and OsloMet’s project team for the collection of data in Norway.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Survey Items and Themes

| Part A: Biographical Information |

| Q1 Age |

| Q2 Gender |

| Q4 Education/qualifications |

| Q5 First language(s) |

| Q6 Other languages |

| Q7 Age range of learners |

| Part B: Characteristics of the Multilingual Context |

| Q8 People with different language backgrounds live in the country where I live and work. |

| Q9 I know the language education policies (e.g., what the language curricula specify) in country I live and work in. |

| Q10 The school where I teach supports the social integration of learners of migrant backgrounds with special programs and/or events. |

| Q11 The average percentage of multilingual learners in my classrooms is approximately |

| Part C: Teacher Beliefs and Reported Practices about English Use in the Multilingual Teaching Context |

| Teacher Beliefs about English Use in Teaching Practices |

| Q30 Teachers of English should have native-like pronunciation. |

| Q31 Non-native teachers can be good language models. |

| Q32 I am comfortable with my own accent. |

| Q33 My learners prefer being taught by native English speakers. |

| Q36 It is important that I integrate examples of English used by non-native speakers in my teaching. |

| Q39 The current status of English as a global language implies that non-native uses of English are as valid as native uses of English. |

| Teacher Beliefs and Practices about English Use in Assessment |

| Q23 In my teaching, I incorporate methods of alternative assessment (e.g., self assessment and peer assessment). |

| Q34 My role as a teacher of English is to correct my learners’ incorrect uses of English. |

| Q37 English language standard tests should also include interactions involving non-native speakers. |

| Q38 When assessing their own learners’ spoken and written production and interactions, teachers should mainly focus on what is intelligible. |

| Teachers’ Reported Teaching Practices for English Use |

| Q14 In my class I give learners several opportunities to interact in English. |

| Q18 I expose my learners to uses of English similar to those they may be exposed to outside the classroom. |

| Q20 I teach standard (British or American) English pronunciation to my learners. |

| Q24 During my English classes I allow my learners to also use languages other than English. |

| Teachers’ Reported Practices for English Use in Teaching Materials and Resources |

| Q12 The coursebook(s) which I use in my class(es) focus/es on the way native English speakers (e.g., British, American, Australian) use the language. |

| Q13 Cultures relevant to my learners, including those of migrant backgrounds, are included in the coursebook(s) which I use in my class(es). |

| Q16 The coursebook(s) which I use in my class(es) include/s topics related to English-speaking-countries traditions, cultures, art, history, and values. |

| Q19 I develop my own additional teaching materials to address the needs and wants of my multilingual learners. |

| Q21 In my teaching, I use authentic materials (TV series, films, songs, etc.) involving predominantly native speakers of English. |

| Q22 In my teaching, I use authentic materials (TV series, films, songs, etc.) involving predominantly non-native speakers of English. |

| Q25 In my experience, my learners are exposed to communication involving non-native speakers of English through teaching materials used in the classroom. |

| Q35 Teachers should use authentic materials in teaching. |

References

- Alisaari, Jenni, Leena Maria Heikkola, Nancy Commins, and Emmanuel O. Acquah. 2019. Monolingual Ideologies Confronting Multilingual Realities. Finnish Teachers’ Beliefs about Linguistic Diversity. Teaching & Teacher Education 80: 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelovska, Tanja, Anna Krulatz, and Dragana Surkalovic. 2020. Predicting EFL Teacher Candidates’ Preparedness to Work with Multilingual Learners: Snapshots from Three European Universities. European Journal of Applied Linguistics and TEFL 9: 183–208. [Google Scholar]

- Aronin, Larissa, and David Singleton. 2008. Multilingualism as a New Linguistic Dispensation. International Journal of Multilingualism 5: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Benjamin. 2007. Heteroglossia and Boundaries. In Bilingualism: A Social Approach. Edited by Monica Heller. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 257–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bayyurt, Yasemin, and Martin Dewey. 2020. Locating ELF in ELT. ELT Journal 74: 369–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayyurt, Yasemin, and Nicos C. Sifakis. 2015. Developing an ELF-aware Pedagogy: Insights from a Self-Education Programme. In New Frontiers in Teaching and Learning English. Edited by Paola Vettorel. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bayyurt, Yasemin, Yavuz Kurt, Elifcan Öztekin, Luis Guerra, Lili Cavalheiro, and Ricardo Pereira. 2019. English Language Teachers’ Awareness of English as a Lingua Franca in Multilingual and Multicultural Contexts. Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics 5: 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beiler, Ingrid Rodrick. 2020. Negotiating Multilingual Resources in English Writing Instruction for Recent Immigrants to Norway. TESOL Quarterly: A Journal for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages and of Standard English as a Second Dialect 54: 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beiler, Ingrid Rodrick. 2021. Marked and Unmarked Translanguaging in Accelerated, Mainstream, and Sheltered English Classrooms. Multilingua 40: 107–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisbart, Claus. 2021. Complexity in Multilingualism (Research). Language Learning 71: 39–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, Katie A., Sultan Kilinc, Megan Troxel Deeg, Scott C. Marley, Kathleen M. Farrand, and Michael F. Kelley. 2021. Language Ideologies of Arizona Preschool Teachers Implementing Dual Language Teaching for the First Time: Pro-multilingual Beliefs, Practical Concerns. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 24: 457–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthele, Raphael. 2021. The Extraordinary Ordinary: Re-engineering Multilingualism as a Natural Category. Language Learning 71: 80–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialystok, Ellen. 2016. Bilingual Education for Young Children: Review of the Effects and Consequences. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21: 666–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birello, Marilisa, Júlia Llompart-Esbert, and Emilee Moore. 2021. Being Plurilingual Versus Becoming a Linguistically Sensitive Teacher: Tensions in the Discourse of Initial Teacher Education Students. International Journal of Multilingualism 18: 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blommaert, Jan. 2010. The Sociolinguistics of Globalization. Cambridge Approaches to Language Contact. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, Simon. 2003. Teacher Cognition in Language Teaching: A Review of Research on What Language Teachers Think, Know, Believe, and Do. Language Teaching 36: 81–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, Simon. 2006. Teacher Cognition and Language Eeducation: Research and Practice. London: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, Simon. 2009. Language Teacher Cognition. In The Cambridge Guide to Second Language Teacher Education. Edited by Anne Burns and Jack C. Richards. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 163–71. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, Simon. 2012. Current Approaches to Language Teacher Cognition esearch: A Methodological Analysis. In Researching Language Teacher Cognition and Practice: International Case Studies. Edited by Roger Barnard and Anne Burns. Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters, pp. 163–71. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, Simon. 2019. Language Teacher Cognition: Perspectives and Debates. In Second Handbook of English Language Teaching. Edited by Xuesong Gao. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1149–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bransford, John, Sharon Derry, David Berliner, and Karen Hammerness. 2005. Theories of Learning and Their Roles in Teaching. In Preparing Teachers for a Changing World. Edited by Linda Darling-Hammond and John Bransford. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 40–87. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2012. Thematic Analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. Edited by Harris Cooper, Paul M. Camic, Debra L. Long, Abigail T. Panter, David Rindskopf and Kenneth J. Sher. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Brevik, Lisbeth M., and Ulrikke Rindal. 2020. Language Use in the Classroom: Balancing Target Language Exposure with the Need for Other Languages. TESOL Quarterly 54: 925–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burner, Tony, and Christian Carlsen. 2017. English Isntruction in Introductory Classes in Norway. In Kvalietet og kreativitet i klasserommet. Edited by Kåre Kverndokken, Norunn Askeland and Henriette Hogga Siljan. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget, pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Burner, Tony, and Christian Carlsen. 2019. Teacher Qualifications, Perceptions and Practices Concerning Multilingualism at a School for Newly Arrived Students in Norway. International Journal of Multilingualism 19: 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, Anne, Donald Freeman, and Emily Edwards. 2015. Theorizing and Studying the Language-Teaching Mind: Mapping Research on Language Teacher Cognition. The Modern Language Journal 99: 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafato, Raees. 2020. Language Teacher Multilingualism in Norway and Russia: Identity and Beliefs. European Journal of Education 55: 602–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafato, Raees. 2021. Teachers’ Reported Implementation of Multilingual Teaching Practices in Foreign Language Classrooms in Norway and Russia. Teaching and Teacher Education 105: 103401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callies, Marcus, Stefanie Hehner, Philipp Meer, and Michael Westphal, eds. 2022. Glocalising Teaching English as an International Language. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Canagarajah, Suresh. 2006. Changing Communicative Needs, Revised Assessment Objectives: Testing English as an International Language. Language Assessment Quarterly 3: 229–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canagarajah, Suresh. 2011. Translanguaging in the Classroom: Emerging Issues for Research and Pedagogy. Applied Linguistics Review 2: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, Jasone. 2003. The Additive Effect of Bilingualism on Third Language Acquisition: A Review. International Journal of Bilingualism 7: 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, Jasone, and Durk Gorter. 2020. Pedagogical Translanguaging: An Introduction. System 92: 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, Jasone, and Durk Gorter. 2022. Pedagogical Translanguaging. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Koun, and Yongcan Liu. 2020. Challenges and Strategies for ELF-aware Teacher Development. ELT Journal 74: 442–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christison, MaryAnn, Anna Krulatz, and Yeşim Sevinc. 2021. Supporting Teachers of Multilingual Young Learners: Multilingual Approach to Diversity in Education (MADE). In Facing Diversity in Child Foreign Language Education. Second Language Learning and Teaching. Edited by Joanna Rokita-Jaśkow and Agata Wolanin. Cham: Springer, pp. 271–89. [Google Scholar]

- Chumak-Horbatsch, Roma. 2019. Using Linguistically Appropriate Practice: A Guide for Teaching in Multilingual Classrooms. Bristol: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Chvala, Lynell. 2020. Teacher Ideologies of English in 21st Century Norway and New Directions for Locally Tailored ELT. System 94: 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogo, Alessia, Fan Fang, Stefania Kordia, Nicos Sifakis, and Sávio Siqueira. 2022. Developing ELF Research for Critical Language Education. AILA Review 34: 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2020. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages; Learning, Teaching, Assessment—Companion Volume. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis, Gessica. 2011. Teachers’ Beliefs about the Role of Prior Language Knowledge in Learning and How These Influence Teaching Practices. International Journal of Multilingualism 8: 216–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bot, Kees, Carol Jaensch, and María del Pilar García Mayo. 2015. What is Special about L3 Processing? Bilingualism 18: 130–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Costa, Peter I., and Bonny Norton. 2017. Introduction: Identity, Transdisciplinarity, and the Good Language Teacher. The Modern Language Journal 101: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Korne, Haley. 2012. Towards New Ideologies and Pedagogies of Multilingualism: Innovations in Interdisciplinary Language Education in Luxembourg. Language and Education 26: 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, Martin, and Inmaculada Pineda. 2020. ELF and Teacher Education: Attitudes and Beliefs. ELT Journal 74: 428–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Zoltán, and Tatsuya Taguchi. 2010. Questionnaires in Second Language Research: Construction, Administration, and Processing. Florence: Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas Fir Group. 2016. A Transdisciplinary Framework for SLA in a Multilingual World. The Modern Language Journal 100: 19–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erling, Elizabeth J., and Emilee Moore. 2021. Introduction–Socially Just Plurilingual Education in Europe: Shifting Subjectivities and Practices through Research and Action. International Journal of Multilingualism 18: 523–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2017. Rethinking Language Education in Schools. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2018a. Teaching Careers in Europe: Access, Progression and Support. Eurydice Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2018b. Council Recommendations on Improving the Teaching and Learning of Languages. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/education/education-in-the-eu/council-recommendation-on-improving-the-teaching-and-learning-of-languages_en (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Flognfeldt, Mona Evelyn. 2018. Teaching and Learning English in Multilingual Early Primary Classrooms. In Den viktige begynneropplæringen. Edited by Kirsten Palm and Eva Michaelsen. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, pp. 229–48. [Google Scholar]

- Flognfeldt, Mona Evelyn, Dina Tsagari, Dragana Šurkalović, and Theresé Tishakov. 2020. The Practice of Assessing Norwegian and English Language Proficiency in Multilingual Elementary School Classrooms in Norway. Language Assessment Quarterly 17: 519–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, Nicola. 2018. ELF and ELT Teaching Materials. In The Routledge Handbook of English as a Lingua Franca. Edited by Jennifer Jenkins, Will Baker and Martin Dewey. London: Routledge, pp. 468–80. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, Nicola, and Takuya Numajiri. 2020. Global Englishes Language Teaching: Bottom-Up Curriculum Implementation. TESOL Quarterly: A Journal for Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages and of Standard English as a Second Dialect 54: 118–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- García, Ofelia. 2009. Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Malden and Oxford: Wiley/Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia. 2019. Decolonizing Foreign, Second, Heritage and First Languages. In Decolonizing Foreign Language Education. Edited by Donaldo Macedo. New York: Routledge, pp. 152–66. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia, and Li Wei. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, Palgrave Pivot. [Google Scholar]

- García, Ofelia, and Ricardo Otheguy. 2020. Plurilingualism and Translanguaging: Commonalities and Divergences. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23: 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Ofelia, Nelson Flores, Kate Seltzer, Li Wei, Ricardo Otheguy, and Jonathan Rosa. 2021. Rejecting Abyssal Thinking in the Language and Education of Racialized Bilinguals: A Manifesto. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 18: 203–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haukås, Åsta. 2016. Teachers’ Beliefs about Multilingualism and a Multilingual Pedagogical Approach. International Journal of Multilingualism 13: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haukås, Åsta, and Sarah Mercer. 2021. Exploring Pre-service Language Teachers’ Mindsets Using a Sorting Activity. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdina, Philip, and Ulrike Jessner. 2002. A Dynamic Model of Multilingualism: Perspectives of Change in Psycholinguistics. Bristol: Channel View Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff-Jenssen, Reidun, Mari Odberg Bjerke, and Hilde Wågsås Afdal. 2020. Begynneropplæring—Et kjent, men uklart begrep: En analyse av læreres perspektiver. Nordisk Tidsskrift for Pedagogikk og Kritikk 6: 143–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holliday, Adrian. 2015. Native-Speakerism: Taking the Concept Forward and Achieving Cultural Belief. In (En)Countering Native-Speakerism. Edited by Anne Swan, Pamela Aboshiha and Adrian Holliday. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hornberger, Nancy H. 2002. Multilingual Language Policies and the Continua of Biliteracy: An Ecological Approach. Language Policy 1: 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornberger, Nancy H., and David Cassels Johnson. 2007. Slicing the Onion Ethnographically: Layers and Spaces in Multilingual Language Education Policy and Practice. TESOL Quarterly 41: 509–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, Hsiu-Fang, and Shannon E. Shannon. 2005. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15: 1277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hult, Francis M. 2014. How Does Policy Influence Language in Education? In Language in Education: Social Implications. Edited by Rita Elaine Silver and Soe Marlar Lwin. London: Continuum, pp. 159–75. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen, Jonas. 2017. The Role of Minority Students’ L1 When Learning English. Nordic Journal of Modern Language Methodology 5: 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, Jennifer. 2015. Repositioning English and Multilingualism in English as a Lingua Franca. Englishes in Practice 2: 49–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jenkins, Jennifer. 2017. Not English but English-within-Multilingualism. In New Directions for Research in Foreign Language Education. Edited by Simon Coffey and Ursula Wingate. New York: Routledge, pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, Jennifer, Alessia Cogo, and Martin Dewey. 2011. Review of Developments in Research into English as a Lingua Franca. Language Teaching 44: 281–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessner, Ulrike. 1999. Metalinguistic Awareness in Multilinguals: Cognitive Aspects of Third Language Learning. Language Awareness 8: 201–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessner, Ulrike. 2008. A DST Model of Multilingualism and the Role of Metalinguistic Awareness. The Modern Language Journal 92: 270–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Karen E. 2009. Second Language Teacher Education: A Sociocultural Perspective. ESL & Applied Linguistics Professional Series; London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen, J. Normann. 2008. Polylingual Languaging Around and Among Children and Adolescents. International Journal of Multilingualism 5: 161–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvdou, Androniki, and Dina Tsagari. 2018. Towards an ELF-aware Alternative Assessment Paradigm in EFL Contexts. In ELF for EFL Contexts. Edited by Nicos Sifakis and Natasha Tsantila. Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters, pp. 227–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kroskrity, Paul. 2010. Language Ideologies—Evolving Perspectives. In Society and Language Use. Edited by Jürgen Jaspers, Jan-Ola Östman and Jef Verschueren. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Krulatz, Anna, and Anne Dahl. 2016. Baseline Assessment of Norwegian EFL Teacher Preparedness to Work with Multilingual Students. Journal of Linguistics and Language Teaching 7: 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Kubanyiova, Magdalena, and Anne Feryok. 2015. Language Teacher Cognition in Applied Linguistics Research: Revisiting the Territory, Redrawing the Boundaries, Reclaiming the Relevance. The Modern Language Journal 99: 435–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulturdepartementet. 2021. Lov om språk (Språklova). Oslo: Kulturdepartementet. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, Constant, and Guadalupe Valdes. 2019. Translanguaging and the Transdisciplinary Framework for Language Teaching and Learning in a Multilingual World. Modern Language Journal 103: 348–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Li. 2020. Language Teacher Cognition. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Michael H. 2005. Second Language Needs Analysis. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lopriore, Lucilla. 2015. ELF and Early Language Learning: Multiliteracies, Language Policies and Teacher Tducation. In Current Perspectives on Pedagogy for English as a Lingua Rranca. Edited by Yasemin Bayyurt and Sumru Akcan. Berlin, Munchen and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar]

- Lopriore, Lucilla. 2021. Needs Analysis. In The handbook to English as a Lingua Franca Practices for Inclusive Multilingual Classrooms. Edited by Lili Cavalheiro, Luis Guerra and Ricardo Pereira. Apartado: Edições Húmus. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, Ragnhild, and Theresé Tishakov. 2017. “I Feel Much More Confident Now.” Om Engelsklærere og Vidreutdanning. In Kvalitet og kreativitet i klasserommet. Edited by Kåre Kverndokken, Norunn Askeland and Henriette Hogga Siljan. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget, pp. 171–92. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Jones, Marily, Adrian Blackledge, and Angela Creese, eds. 2012. The Routledge Handbook of Multilingualism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]