Abstract

Internationally, multi-/plurilingualism has been defined as an important educational goal and plurilingual education as a right for all learners. The present study investigates the readiness of Norwegian pre-service teachers (N = 54) to lay the foundations for multilingualism and life-long language learning (LLLL) for all pupils in the elementary school English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classroom. For this purpose, we studied pre-service teachers’ conceptualization of multilingualism and their cognitions about laying the foundations for LLLL, using pluralistic approaches, and the importance of cross-linguistic awareness. The following data collection instruments were employed: (a) a survey with open- and closed-ended questions and (b) a short Likert scale survey with items based on the Framework of References for Pluralistic Approaches to Languages and Culture (FREPA). We found that the participants’ conceptualization of multilingualism reflected key dimensions in the field. The great majority of them had a positive view of the contribution that elementary school EFL teaching can make to multilingualism. The overwhelming majority were also positive about laying the foundations for LLLL and agreed that cross-linguistic awareness is important for pupils. However, almost one-third of the pre-service teachers were skeptical about pluralistic approaches to teaching.

1. Introduction

International education policymakers, such as the Council of Europe (CoE 2007), have identified multi-/plurilingualism1 as an important educational goal and plurilingual education as a right for all learners (Beacco et al. 2016; Coste et al. 2009). For children with multilingual home backgrounds2, this includes enabling the children to exploit the full potential of their existing language competence and to understand multilingualism as an asset. For children with a monolingual background, this primarily means laying the foundations for plurilingualism and life-long language learning (LLLL). Plurilingualism is considered a key to democratic citizenship, social cohesion, and access to the labor market (Coste et al. 2009; cf. also Grin 2017, p. 116ff.). These ideas have also inspired national policies, for example, in Austria, French-speaking Switzerland, and Spain (Daryai-Hansen et al. 2015); in Norway (Norwegian Directorate 2013, 2020b; Norwegian Ministry 2004a, 2004b); Finland (Alisaari et al. 2019); Denmark (Daryai-Hansen et al. 2019); and Vanuatu (Willians 2013).

1.1. Pluralistic Approaches

In language teaching methodology, so-called pluralistic approaches3 provide the theoretical and practical means to reach the goals put forward in plurilingualism-inspired education policies. To this end, pluralistic approaches make use of teaching and learning activities that involve several varieties of languages or cultures (Candelier et al. 2012a, p. 6). Pluralistic approaches have the explicit aim of establishing “links between competences which the learners already possess and those which the educational system wishes them to acquire” (Candelier et al. 2012b, p. 247; cf. also Haukås and Speitz 2020; Cenoz and Gorter 2013; Piccardo 2013). Pluralistic approaches thus do not simply aim to promote the development of a plurilingual repertoire; they explicitly seek to draw on learners’ existing repertoires and learning experiences as a resource for (further) language learning.

In this context, metalinguistic knowledge and metalinguistic awareness play an important role. Metalinguistic knowledge, in other words, implicit and explicit knowledge about language(s) as opposed to knowledge of a language, is instantiated as metalinguistic awareness (Bialystok 2001). Metalinguistic awareness, in turn, has been proposed as an important factor in being able to make use of existing competencies to learn subsequent languages (e.g., Cenoz and Gorter 2013; Piccardo 2013; Bialystok et al. 2012; Bialystok 2001; cf. also Beacco et al. 2016). Due to their inherent reflexivity, plurilingual, cross-linguistic activities can contribute to enhancing learners’ metalinguistic awareness, and especially learners’ cross-linguistic awareness (cf. Beacco et al. 2016). According to Cenoz and Jessner (2009), cross-linguistic awareness can be defined as “the learner’s tacit and explicit awareness of the links between their language systems” (p. 127; our emphasis). Our understanding of cross-linguistic awareness, which draws on Möller-Omrani et al. (2021), goes one step further. We consider any instance of metalinguistic awareness requiring some form of language comparison as constituting an instance of cross-linguistic awareness.

Candelier and colleagues (2012a, 2012b; cf. also Piccardo 2013) distinguished three main language-targeted pluralistic approaches which differ in their respective focus but are not mutually exclusive. The integrated didactic approach is based on the idea of establishing links between the limited number of languages taught in the education system. Pupils’ first language or the language of education is used to aid the acquisition of a first foreign language. These two languages subsequently support the acquisition of a second foreign language. In intercomprehension between related languages, the language to be studied belongs to the same language family as one of the languages the learner is already familiar with (the home language, language of education, or another language). Last but not least, awakening to languages aims to introduce pupils to linguistic diversity and to recognize the varieties that pupils from diverse backgrounds bring to the classroom. While the language of education and/or other languages that may be learned in school (e.g., English) are within this spectrum, the approach is not limited to these or to any specific number of languages.

Pluralistic approaches to language teaching have also been proposed for the EFL4 classroom, for instance, focus on multilingualism (Cenoz and Gorter 2013; cf. also the TESOL Quarterly special topic issue “Plurilingualism in TESOL” (2013)) or, more recently, pedagogical translanguaging (Cenoz and Gorter 2020; Cenoz and Santos 2020). However, with regard to teaching (not only) ESL or EFL, so-called singular approaches, which recognize only one particular language or culture and deal with it in isolation (Candelier et al. 2012a, p. 6), have been dominant (e.g., Cummins 2017; Paquet-Gauthier and Beaulieu 2016; May 2014; Cenoz and Gorter 2013; Piccardo 2013). Such approaches create artificial “hard boundaries” (Cenoz and Gorter 2013), not only among the languages taught but also between learners’ existing linguistic repertoire and the language(s) to be learned.

Not surprisingly, recent studies indicated that pre- and in-service teachers lack the requisite knowledge and training for such approaches, even if they have a positive attitude toward plurilingualism and using multilingualism as a classroom resource (e.g., Dégi 2016; Krulatz and Dahl 2016; Haukås 2016; Surkalovic 2014; De Angelis 2011). Teacher preparedness is crucial, however, since the responsibility for implementing plurilingual policies falls on the education system and thus, ultimately, on the individual teacher. Here, teacher cognition—the “unobservable dimension of teachers’ professional lives” (Borg 2019, p. 1149)—comes into play.

1.2. Teacher Cognitions

When used as an umbrella term, teacher cognition stands for a cluster of complex aspects of teachers’ minds, such as knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, thoughts, and, more recently, emotions (Borg 2019). Teacher cognitions are shaped by teachers’ situated personal and professional experiences (ibid.). Teacher cognitions, in turn, shape the process of becoming a teacher, teachers’ professional practice, and their development (Borg 2019), although the relationship between cognition, development, and practice is also complex (cf. Borg 2006, 2018; Phipps and Borg 2009).

The existing body of research on teacher cognition about multilingualism, multilingualism as a resource, and pluralistic pedagogical approaches is limited. In a recent study of in-service teacher beliefs about multilingualism in a course on translanguaging, Gorter and Arocena (2020) summarize eight studies in the field (Portolés and Martí 2020; Tarnanen and Palviainen 2018; Arocena 2017; Otwinowska 2017; Dégi 2016; Haukås 2016; Arocena et al. 2015; Young 2014), in addition to studies already reviewed in Haukås (2016) (Heyder and Schädlich 2014; Jakisch 2014; Otwinowska 2014; De Angelis 2011). We have incorporated the results of several additional studies (Gorter and Arocena 2020; Rodríguez-Izquierdo et al. 2020; Alisaari et al. 2019; Daryai-Hansen et al. 2019; Lundberg 2019; Krulatz and Dahl 2016; Griva and Chostelidou 2012) into our own review. Several of these studies focus on elementary school teachers (Gorter and Arocena 2020; Lundberg 2019; Arocena 2017; Arocena et al. 2015) or at least include them in their overall data set (Rodríguez-Izquierdo et al. 2020; Tarnanen and Palviainen 2018; Otwinowska 2014, 2017; Krulatz and Dahl 2016; Young 2014; Griva and Chostelidou 2012). The remaining studies focus on secondary school teachers or have underspecified their participants.

Not only have previous studies been conducted in a variety of national contexts, they also differ with regard to many other factors, such as the learning/teaching context (e.g., foreign language learning vs. content subjects), the level of the educational system (primary, secondary, tertiary education), the participants (pre-service vs. in-service teachers), and which pupils were targeted (e.g., foreign language learners vs. minority-language children). Research findings thus are not always easily comparable. However, several main tendencies can be discerned.

Overall, teachers seem to take a positive view of multilingualism and plurilingualism-inspired approaches to teaching (but see Lundberg 2019; Young 2014; Dooly 2005, 2007), whether for children with home languages other than the language of schooling or in the context of foreign language teaching. At the same time, previous studies indicate that teachers may not be and/or may not feel sufficiently well-prepared to implement a multilingual approach (Gorter and Arocena 2020; Alisaari et al. 2019; Daryai-Hansen et al. 2019; Tarnanen and Palviainen 2018; Dégi 2016; Haukås 2016; Krulatz and Dahl 2016; Otwinowska 2014; De Angelis 2011).

In addition, teachers’ overall favorable attitude collides with other conflicting beliefs (Alisaari et al. 2019; Arocena 2017; Arocena et al. 2015; De Angelis 2011), such as the value of language separation and the exclusive use of the target language to maximize exposure. Teachers may even acknowledge the value of children’s home languages in general while viewing the use of these languages in the classroom much less favorably and voicing concerns about, for instance, a delay in learning the language of schooling or concerns about pupils and teachers not familiar with these languages feeling excluded (Alisaari et al. 2019; De Angelis 2011).

In a similar vein, teachers seem to differentiate between the languages involved when it comes to cross-linguistic comparison and using multilingualism as a resource. On the one hand, teachers see previously acquired languages as a stepping stone to learning additional languages (Jakisch 2014; De Angelis 2011), and they report drawing on the language of schooling and on language(s) already learned in the educational system (Daryai-Hansen et al. 2019; Haukås 2016; Heyder and Schädlich 2014). Teachers are less inclined, on the other hand, to draw on the full spectrum of linguistic repertoires their pupils bring to the classroom, especially if they themselves are unfamiliar with these languages (Rodríguez-Izquierdo et al. 2020; Daryai-Hansen et al. 2019; Arocena 2017; Haukås 2016; Heyder and Schädlich 2014; De Angelis 2011). It is, therefore, not surprising that there seems to be a discrepancy between teachers’ overall positive stance and their (self-reported) practice (Daryai-Hansen et al. 2019; Dégi 2016; Haukås 2016; Arocena et al. 2015; Heyder and Schädlich 2014).

Teachers tend to view multilingualism and a plurilingualism-inspired approach to teaching more positively if they themselves are multilingual and their professional experience includes linguistically diverse classrooms. Studies looking at language teachers have found that, in general, these teachers are favorably predisposed to multilingualism and plurilingual approaches (Gorter and Arocena 2020; Otwinowska 2014, 2017; Haukås 2016; Krulatz and Dahl 2016; Heyder and Schädlich 2014), whereas this was not necessarily the case for teachers of other subjects (Young 2014; De Angelis 2011) or teachers with little experience in such settings (Alisaari et al. 2019; Lundberg 2019). At the same time, teachers’ level of proficiency in other languages seems to have an impact on their plurilingual awareness, defined as their “ability to promote plurilingual approaches in the language classroom” (Otwinowska 2014, p. 114).

Gorter and Arocena (2020) recently showed that teachers’ beliefs about a plurilingualism-inspired approach can be influenced favorably through professional training measures. Their participants, in-service teachers in the Basque Country in Spain (94% with a qualification for teaching English), had voluntarily signed up for a training course on new ideas about multilingualism (cf. Cenoz and Gorter 2013). As a result of this training, the teachers viewed several aspects of a plurilingualism-inspired teaching method more favorably than before. They agreed to a greater extent that one language can be helpful in learning another language, for example, and that comparing languages can be useful in this context. In addition, they took a more favorable view of mixing and alternating languages and a less favorable view of a strict language separation policy. While teachers’ cognitions can thus be influenced in favor of using a multilingual approach, this may not have an impact on their practice unless additional practical support is provided, for example, teaching materials with concrete activities using a pluralistic approach (Daryai-Hansen et al. 2019).

1.3. Pre-Service Teacher Cognitions

The number of studies that focus specifically on pre-service teacher cognition about multilingualism and/or pluralistic approaches is even more limited. Nevertheless, these studies mirror the findings for in-service teachers. Pre-service teachers seem to have a generally positive view of multilingualism and pupils’ home languages (Hegna and Speitz 2020; Llompart and Birello 2020; Portolés and Martí 2020; Cybulska and Borenic 2014)—maybe even more so than in-service teachers (Dooly 2005, 2007). However, pre-service teachers also share in-service teachers’ concerns when it comes to including the home languages of children with an immigrant background (Iversen 2021). Portolés and Martí (2020) showed that this can even be the case in a context where pre-service teachers express strong support for promoting minority languages. The participants in Portolés and Martí’s study, from the Valencian Community in Spain, seemed to associate the term “minority language” almost exclusively with autochthonous minority languages such as Catalan, which has co-official status in the Valencian Community and was the first language of many of the pre-service teachers in the study.

Similar to in-service teachers, pre-service teachers seem to be and/or to feel largely unprepared for multilingual classrooms and a multilingual approach, independently of whether they themselves have a migration background (Llompart and Birello 2020; Otwinowska 2014; Surkalovic 2014). In a recent study conducted in Norway, for example, Hegna and Speitz (2020) found that pre-service teachers of different language and content subjects associated multilingualism mainly with pupils having a different home language than the majority language, Norwegian. At the same time, Hegna and Speitz’s participants mainly seemed to associate the inclusion of several languages in the classroom with a transitional use of the pupils’ home languages until these pupils achieved sufficient fluency in the majority language. This suggests unfamiliarity with a wider concept of multilingualism and pluralistic approaches. However, pre-service teachers’ plurilingual awareness may also be connected to their own multilingualism, in other words, to the number of languages they speak and their proficiency in these languages (Otwinowska 2014; but see Cybulska and Borenic 2014).

Pre-service teachers themselves seem to recognize the need for further training and welcome offers of additional training (Portolés and Martí 2020; Cybulska and Borenic 2014). In this context, Woll (2020) and Portolés and Martí (2020) have recently shown that targeted training offers can have an impact on pre-service teacher cognitions about pluralistic approaches (see also Surkalovic 2014). This ties in with other studies which have found pre-service teachers more inclined to renegotiate their initial perceptions than in-service teachers (Dooly 2005) and their ideologies to not yet be fixed to the same degree (Iversen 2021). However, some aspects of pre-service teacher cognitions seem to be more difficult to influence than others, as the studies by Woll (2020) and Portolés and Martí (2020) show.

Woll (2020) conducted an intervention study on pre-service teacher cognition about pluralistic classroom practice. Her participants, pre-service teachers of ESL in the Canadian province of Quebec, attended a German language course in which they themselves experienced first a target-language-only approach and then a cross-linguistic approach. Her participants were overwhelmingly positive about their own experience of the cross-linguistic approach, and their pedagogical reflections seemed to be evolving during and after the intervention. However, Woll found that her participants’ cognition was subject to a variety of (sometimes conflicting) influences: theoretical knowledge acquired during teacher training, experiences gained in teaching practice and their own experiences as a learner. Personal experience as a learner did not seem to be enough on its own to challenge deep-rooted beliefs about good language teaching, such as a monolingual ideology.

Similarly, Portolés and Martí (2020) investigated pre-service teachers’ beliefs about multilingual pedagogies and the impact of teacher training on these beliefs. The participants in their study, pre-service preschool and primary school teachers in the Valencian Community of Spain, were attending a course that revolved around teaching in English in multilingual contexts and integrating languages and content. Portolés and Martí (2020, p. 253) found significant training effects in four previously identified areas: (1) the status of European languages, the status of English, and multilingual policy in Europe; (2) benefits of multilingualism and the notion of multicompetence; (3) forms of immersion in English; and (4) the ideal profile of multilingual teachers and their professional development. Since their findings show a “shift toward greater alignment in beliefs with principles of multilingual education research” (2020, p. 261), Portolés and Martí conclude that teacher training programs can be effective when it comes to reshaping beliefs in this area. However, there was no significant effect from training in two other areas: (1) ways of enhancing multilingual education and (2) early foreign language learning. Portolés and Martí conclude that teacher training is more effective with respect to academic, theory-informed topics than with respect to controversial topics, such as including migrant children’s languages, or popular misconceptions, such as the “the earlier the better”.

To the best of our knowledge, to date, only one study has investigated pre-service teacher cognitions about plurilingualism and using pluralistic approaches in the EFL classroom. Cybulska and Borenic (2014) investigated the attitudes of Polish and Croatian pre-service EFL teachers and found, first of all, a positive attitude toward foreign languages and language learning—which is somewhat to be expected for future language teachers. When asked about the languages they would recommend that their pupils learn, the participants named mainly larger European languages (German, Spanish, French, and Italian), which were also the languages most widely spoken by these participants. However, when specifically asked whether they would recommend learning a less widely used language, almost 70% of the pre-service teachers showed openness toward recommending a less widely used language. Cybulska and Borenic’s participants also expressed a positive attitude toward promoting plurilingualism and using pluralistic approaches. This positive attitude tied in with Cybulska and Borenic’s finding that nearly all the pre-service teachers agreed that their knowledge of English would help them when learning another language from the same language family. Of these pre-service teachers, 95% also said they would draw on their own and their pupils’ language knowledge and skills in the classroom. At the same time, 82% of them showed an interest in further training. In contrast to Otwinowska (2014), Cybulska and Borenic did not find that the number of languages their participants spoke or their professional experience influenced their willingness to use pluralistic approaches.

The present study aims to make a contribution, from a Norwegian perspective, to the very limited body of research on pre-service teachers’ preparedness to promote multilingualism and to use pluralistic approaches in the EFL classroom. Similar to Cybulska and Borenic (2014) and in contrast to previous research focusing on linguistically diverse classrooms, we have investigated the degree to which Norwegian elementary school pre-service teachers of English are prepared to lay the foundations for multilingualism and LLLL for all pupils.

1.4. The Norwegian Context

In Norway, the education system is structured into elementary school (grades 1 to 7), lower secondary school (grades 8 to 10), and upper secondary school (grades 11 to 13). The first foreign language is English, which is taught from grade one, albeit for a limited number of hours. English is allocated a total of 138 teaching hours for grades one to four and a total of 228 hours for grades five to seven. Other foreign languages (mostly German, French, and Spanish) are regularly offered, beginning in eighth grade. At the same time, Norway is an inherently multilingual country with an abundance of immigrant languages in addition to two official written standards of Norwegian, several officially recognized minority languages, a rich landscape of geographical dialects, and strong historical ties with other Scandinavian countries and their languages (see, e.g., Haukås and Speitz 2020; Krulatz et al. 2018). According to Haukås and Speitz (2020), all Norwegian pupils can be considered plurilingual.

Recently, the Norwegian curriculum has been substantially revised, but multilingualism figures prominently in both the old (LK06)5 and the new curriculum (LK20), as does a pluralistic approach. However, the LK06’s “General Part” (Norwegian Directorate 1994), which dates to 1994 and outlines the values and vision of the curriculum, did not yet include the idea of multilingualism as a resource. Instead, learning about minority cultures and, in the case of Sami, about their language was a part of the educational vision. At the same time, the “Purpose” section of the LK06 curriculum for English, which outlined the general aims of the subject, explicitly stated that “[l]earning English will contribute to multilingualism and can be an important part of our personal development” (Norwegian Directorate 2013, p. 1). The LK06 concretized that language learning includes seeing “relationships between English, one’s native language and other languages” (p. 3)—clearly a cross-linguistic, pluralistic endeavor, which needs to be seen in connection with the acquisition of learning strategies advocated throughout the LK06. Specific competence aims, which pupils were to achieve by a certain grade, made for further concretization. After grade two, for example, pupils were expected to be able to “find words and phrases that are common to English and one’s native language” (p. 6). After grade seven, they were expected to be able to “identify some linguistic similarities and differences between English and one’s native language” (p. 8). Such aims could not be achieved without softening the boundaries between languages. In addition, these aims are closely linked to metalinguistic awareness since cross-linguistic comparison, such as identifying similarities and differences, is a profoundly metalinguistic activity. However, the idea of drawing on all pupils’ entire linguistic repertoire is not unequivocally expressed in LK06. In the authors’ own experience as teachers and teacher educators, teachers drew almost exclusively on Norwegian in their English classes and rarely for the purpose of cross-linguistic comparison but as a vehicle language “so that everybody understands”.

In the revised curriculum, which has been undergoing implementation since the fall of 2020, the idea of multilingualism as a resource and the promotion of plurilingualism have been made explicit. The new “Core Curriculum”—which replaces the former “General Part”—states that “[a]ll pupils shall experience that being proficient in a number of languages is a resource, both in school and society at large” (Norwegian Directorate 2020a, p. 2). This idea is repeated almost verbatim in the “Relevance and Central Values” section of the new curriculum for English, which outlines why the subject is important for pupils, working life, and society at large. The idea of multilingualism as a resource is further concretized in the new “Core Elements” for the English subject.6 The core element “Language learning” is now more explicit than the LK06 about including all pupils’ full linguistic repertoire: “Language learning refers to identifying connections between English and other languages the pupils know” (Norwegian Directorate 2020b, p. 2f.; our emphasis). This is again concretized in specific competence aims for the different grades.

Pre-service teachers in Norway are trained at universities and university colleges (for a more detailed description, see, for example, Krulatz and Dahl 2016 and Surkalovic 2014). Primary school teachers of English are required to take a minimum of 30 credits in the subject; for lower and upper secondary teachers, the requirement is 60 credits. Since these are comparatively recent requirements, many teachers lack the formal qualifications for teaching English. In 2018/19, only 32% of English teachers at elementary schools in Norway had formal qualifications for the subject (Statistics Norway 2019). In-service training courses offered at universities and university colleges are only gradually able to remedy the situation.

Plurilingualism and plurilingual approaches were not mentioned explicitly in the 2010–2018 national guidelines for the training of elementary school teachers of English, although they could be seen as implied in some passages under the general umbrella of diversity. Students were, for example, expected to be “able to plan, lead, and assess […] in a way that takes into account pupils’ diversity in regard to different needs and different cultural and linguistic backgrounds” (UHR 2010, p. 38). In terms of cross-linguistic comparison, the guidelines specifically called for students to acquire “knowledge about grammatical structures with special emphasis on differences and similarities between English and Norwegian” (p. 38; our translation and emphasis). However, students were also supposed to learn how to “guide pupils so that they can make use of differences and similarities between the mother tongue and English” (p. 38; our translation and emphasis). This mixed message may have contributed to the fact that few teacher training programs in Norway seem to have systematically included multilingualism and multilingual approaches in their education for future teachers of English (cf. Krulatz and Dahl 2016).

The policy background has now changed, and the new teacher education guidelines for elementary school (UHR 2018) explicitly require pre-service teachers of English to learn about multilingualism as a resource. It remains to be seen, however, to what degree this will be implemented in teacher education programs and how it will impact the cognition and practice of future pre-service and in-service teachers.

Several of the studies on teacher cognition reviewed above were conducted in Norway or included the Norwegian context (Iversen 2021; Hegna and Speitz 2020; Daryai-Hansen et al. 2019; Krulatz and Dahl 2016; Haukås 2016; Surkalovic 2014). Their results are in agreement with findings from other countries: Even though pre- and in-service teachers view plurilingualism as an asset, they are ill-prepared for promoting plurilingualism and using a multilingual teaching approach. The feedback that a first draft of the revised curriculum received in a national hearing is aligned with this: schools and teachers commented that they did not understand what multilingualism as a competence aim means and how it should be achieved (Norwegian Directorate 2018).

1.5. The Present Study

Against the background set out in the previous subsections, we raise the following research question: What cognitions do Norwegian pre-service teachers of English have about laying the foundations for multilingualism in elementary school EFL classes?

We have formulated five additional sub-questions:

- How do Norwegian pre-service teachers of English conceptualize multilingualism?

- What was their own school experience in terms of EFL classes promoting multilingualism?

- What are their cognitions about laying the foundations for LLLL in their future EFL teaching?

- What are their cognitions about using a pluralistic approach in their future EFL teaching?

- What are their cognitions about the importance of promoting cross-linguistic awareness in the EFL classroom?

We expected to be able to identify some tendencies consistent with previous studies, where such studies have been conducted. That is, we expected a predominantly positive view of multilingualism, plurilingual approaches, and pupils’ home languages. Likewise, we anticipated a predominantly positive attitude toward laying the foundations for learning additional languages. We also expected general agreement that (a) learning English contributes to multilingualism and that (b) it is important to promote cross-linguistic strategies in the classroom.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Fifty-four pre-service teachers participated in the study, 40 of them identifying as female and 14 as male (see Table 1). All of the participants were enrolled at a large, urban university college in Norway in a teacher education program for grades 1 to 7 (Norwegian elementary school) and had chosen English as an elective subject, in addition to mandatory mathematics and Norwegian. Thirty-one participants were first-year students at the end of their first semester. Twenty-three participants were second-year students at the beginning of their final semester of English who had one prior semester of English. Both groups had recently returned from teaching practice and had had a brief introduction to Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) as part of their studies.

Table 1.

Participants.

Fifty-two participants (96%) stated that their first language was Norwegian. Four of these considered themselves bilingual, with Norwegian and another language as first languages (L1) (Dutch, English, Tamil). Two participants stated that a language other than Norwegian was their L1 (Icelandic, Spanish). In response to the question of how many languages they felt able to carry out a conversation in—anything from ordering something at a restaurant to having an academic conversation—ten participants (19%) answered two, 28 (52%) said three, ten (19%) said four, and five (9%) said five (see Table 2). One participant did not answer the question.

Table 2.

Self-reported language competence: number of languages in which participants can carry out a conversation.

When participants were asked to state which additional languages they knew and how they would rate their overall confidence in these languages on a five-point scale from “not at all confident” to “very confident,” all 54 named English and gave a range from three to five points. The full spectrum of languages stated, as well as the participants’ self-reported competence level, is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Participants’ self-reported additional language competence on a 5-point scale from “not at all confident” (1) to “very confident” (5).

2.2. Method

A written questionnaire was administered to the participants. In section 1 of the questionnaire (see Table 4), they were asked to reflect on multilingualism and using a pluralistic approach to language teaching in their future career as EFL teachers. More specifically, the participants were asked about:

Table 4.

General instruction and items included in section 1 of the questionnaire.

- Their conceptualization of multilingualism (Item 1);

- Their own school experience in regard to EFL classes promoting plurilingualism (Item 2);

- Their cognitions about using an approach to EFL teaching which prepares pupils for learning additional languages (Item 3); and

- Their cognitions about including languages other than English in the EFL classroom (Items 4 and 5).

The questions in this section contained an open-ended or both an open-ended and a closed (yes/no) item.

In section 2 of the questionnaire, the participants were presented with a six-item, five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. The instructions given for the Likert scale items were: “Following are a number of statements about knowledge and skills related to language and language learning. To which extent do you agree that the English classroom should contribute to developing these? Please indicate the extent of your agreement/disagreement in the table below”.

The purpose of this Likert scale was to investigate the perceived importance of developing cross-linguistic knowledge and skills in the EFL classroom and, more specifically, the importance which the participants attributed to developing knowledge and skills for which a pluralistic approach to teaching is essential. All of the items on the scale were taken from the Framework of References for Pluralistic Approaches to Languages and Culture (FREPA) (Candelier et al. 2012a, 2012b). FREPA provides a set of global competences that pluralistic approaches contribute to developing and a detailed list of reference descriptors for resources that are presumed to contribute to the activation of these global competencies (Candelier et al. 2012a, 2012b). FREPA further postulates that the development of the resources described by the reference descriptors can be worked on in the classroom (Candelier et al. 2012a, p. 13). The reference descriptors are further sorted into three different but interrelated categories: knowledge, attitudes, and skills.

Six descriptors from the knowledge and skills sections of FREPA were selected for the Likert scale. Three criteria were applied in the selection process. First of all, descriptors were only considered if they related to language and were perceived as relating to metalinguistic awareness (cf. Candelier et al. 2012b, p. 77). That is, only descriptors that were considered to refer to knowledge about language(s) (knowledge category) or to the application of this kind of knowledge (skills category) were included. Secondly, only descriptors with a green key in FREPA were included. These are descriptors where the use of a pluralistic approach is considered essential in order to develop the respective resource. That is, the resource described by the descriptor probably cannot be attained without drawing on pluralistic approaches (cf. Candelier et al. 2012b, p. 17). Last but not least, the descriptors were chosen so as to be neither too abstract nor too specific. This was done to ensure that the descriptors were concrete enough to be easily understood while also ensuring a certain degree of generalization. The descriptors thus selected were used to create the final items for our Likert scale, which are shown in Table 5, together with their original FREPA code and section. For better comprehension, the original wording of K 6.5 was changed from “phonetic/phonological system” to “sound system” and in K 7.2 the bracketed text was removed. All other descriptors were included verbatim.

Table 5.

FREPA-based items used in the present study.

Section 4 of the questionnaire, which included two metalinguistic awareness tasks from the EVLANG (Candelier 2003) project, will not be reported in the present study. Section 5 collected the background information reported above (gender, first language(s), and additional languages, self-reported confidence in the use of these languages, context in which these languages were learned, desire to learn additional languages).

A pilot study was conducted with ten pre-service teachers, after which the original questionnaire was altered slightly with regard to the phrasing of some of the questions and the ordering of the sections. The final questionnaire was administered during seminars in EFL teacher education. The participants were told that there were no right or wrong answers and to write in the language they felt most comfortable in, whether English or Norwegian, even if the questions themselves were given in English. Furthermore, there was no time limit for answering. All participants answered within the 90 min duration of the seminar, with the longest time taken to complete the questionnaire being approximately 30 min.

The qualitative questionnaire data from section 1 of the questionnaire was analyzed with the help of NVivo 12 Pro through inductive thematic analysis (Nowell et al. 2017; Braun and Clarke 2006) using a semantic approach to coding (cf. Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 84). In the second step, we developed main themes on the basis of the number of speakers in whose answers we had identified these themes. The Likert scale items were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Agreement rates for individual items and levels (see Section 3.6) were calculated as follows: number of participants divided by the total number of participants.

3. Results

3.1. Pre-Service Teachers’ Conceptualization of Multilingualism

In order to investigate pre-service teachers’ conceptualizations of multilingualism, the participants were presented with the following statement: “Please explain what ‘multilingualism’ is.” (Item One). All of the participants answered, albeit in varying degrees of detail ranging from short definitions such as “Multilingualism is when you have several languages” (P31) and “multilingualism is a term that means ‘several languages’” (P53) to complex, highly reflective definitions such as “[p]laces, rooms, people etc. can be multilingual.—something that has several languages. Maybe even the definition on ‘language’ can variere [Norwegian <vary>]” (P41) or “My understanding of multilingualism is that someone is somewhat fluent in many languages, more specifically I believe it is more than two languages. In some cases, I also believe it can be connected to the different literacies, as well, in the sense that language we use on the internet and slang can be viewed as its own language” (P40). Thirteen participants (24%) provided the Norwegian translation “flerspråklighet” without further explanation. Three participants (5%) answered that they were not sure what multilingualism was.

We identified three main dimensions in the participants’ explanations, which correspond to three central dimensions in current discussions in the field (cf. Romaine 2017; Cenoz 2013): number of languages, competence, and individual vs. societal multilingualism (see Table 6). Thirty-eight participants (70%)7 defined multilingualism as involving either more than two or several languages (N = 25; 46%) or at least more than one language (N = 13; 24%). Two participants (4%) used both “several” and “more than one,” as exemplified in P19′s definition: “The ability to speak/use multiple languages. A multilingualist [sic] possesses more than one language they can speak or use.”

Table 6.

Main dimensions and subdimensions of participants’ conceptualization of multilingualism. Mentions are given as a percentage of the total number of participants, followed by the absolute number of mentions. More than one theme or subtheme can be present in a single participant’s answer.

Thirty-two participants (59%) made reference to competence. Overall, the participants seemed to conceptualize multilingualism as involving an active command of languages, such as being able to speak, communicate, express oneself, or use several languages (N = 30; 56%). This result should not be overinterpreted, however, since “speaking a language” is commonly used as a generic expression, and some of the same participants (N = 6; 11%) explicitly mentioned “understanding” several languages. A few of the participants also addressed multilingual literacy (N = 4; 7%).

Eleven participants (20%) made reference to the individual vs. societal dimension of multilingualism. They seemed to conceptualize multilingualism predominantly as individual and personal (N = 9; 17%) rather than societal (N = 2; 4%). However, multilingualism was also described as potentially being tied to different spaces and domains, such as a multilingual classroom at school, work, a specific room, or a specific conversation (N = 7; 13%). Interestingly, only three participants (6%) explicitly connected multilingualism to growing up with more than one language.

3.2. Pre-Service Teachers’ Own School Experience: The Contribution of English to Multilingualism

In order to investigate pre-service teachers’ own school experiences in regard to the contribution EFL teaching can make to multilingualism, the participants were asked the following question: “According to the Norwegian National Curriculum (LK06), ‘Learning English will contribute to multilingualism.’ Thinking back to your own school experience, do you agree?” (Item Two). The participants were then presented with a yes/no option before being asked to elaborate on why they did or did not agree with the statement. Forty-eight participants (89%) agreed that learning English contributes to multilingualism. Only five participants (9%) disagreed, and one participant left this item blank. Their reasons for agreeing and disagreeing were varied. The five participants who responded negatively referred mainly to the quality of EFL teaching and insufficient learning outcomes, such as their English classes being more focused on grammar than on communication and their having learned English mainly outside of school.

Of the 48 participants who agreed, 42 provided a further explanation. Not surprisingly, the main theme we identified (N = 30; 56%) was that learning English contributes to multilingualism by adding English to one’s linguistic repertoire (see Table 7). However, eight of these participants and an additional six others (i.e., a total of 14 (26%)) argued that learning English aids later language learning, be it in general (N = 6; 11%), by enabling learners to use cross-linguistic comparison as a learning strategy (N = 7; 13%), or by enhancing motivation (N = 1; 2%). P11′s answer illustrates the latter two and combines personal experience with a more general explanation: “[T]he more languages you learn, the easier it will be to learn new ones. This is because you have multiple languages in your head you can relate to when learning a new one. When I knew English, it was easier for me to learn French.” (P11). Some of the participants made explicit reference to the school setting as being important for learning English and other languages (N = 5; 9%).

Table 7.

Main dimensions and main subdimension (where applicable) of participants’ cognition about the positive contribution that learning English at school can make to multilingualism. Mentions are given as a percentage of the total number of participants, followed by the absolute number of mentions. More than one theme or subtheme can be present in a single participant’s answer.

3.3. Pre-Service Teacher Cognitions about Laying the Foundations for Life-Long Language Learning

In order to examine pre-service teachers’ cognitions about using an approach to EFL teaching which prepares pupils for learning additional languages, the participants were presented with the following item: “Think about your future job as an English teacher: would you teach in a way that also prepares your pupils for learning languages other than English?” (Item Three). The participants were then presented with a yes/no option again and asked to elaborate on why they would or would not do so. Forty-six participants (85%) answered yes, four (7%) answered no, and three (6%) did not answer the question. One participant (2%) indicated both yes and no and expressed a positive attitude toward learning strategies while simultaneously stressing the need to focus on English. The necessity of focusing on English was, in fact, also the participants’ main reason for answering negatively. Three participants (6%) used this argument, adding additional aspects such as the limited number of hours available for English in elementary school: “As I’ve seen in practice, the students need to focus on English during the little time they actually have English at school” (P15).

Of the 46 participants who answered affirmatively, 40 provided additional explanations. We identified two main reasons for being positive about teaching in this way (see Table 8). The most prominent reason (N = 27; 50%) given was to allow pupils to develop competencies that the pre-service teachers seemed to consider important for learning additional languages. We identified two larger subthemes. Subtheme one relates to helping pupils develop language-learning strategies (N = 24; 44%). Here, 15 participants (28%) made general statements about the usefulness of English, as the first foreign language, for this purpose. All of these participants argued that learning English performs an exemplary function for language learning in general. P25, for example, states that “when you learn English you can also learn strategies on how to learn other languages.” Eight participants (15%) more specifically addressed the usefulness of what we have labeled as cross-linguistic teaching and learning, which echoes a core idea of pluralistic approaches: drawing on similarities and differences between previously known or unknown languages in order to foster the acquisition of a new language and, moreover, to enable pupils to do this systematically and employ it as a learning strategy. In P54′s words, “That would be my goal. To let the pupils see the similarities and find their way of learning a new language, by teaching them English”. Two participants (4%) specified that learning about English would be helpful for learning other languages. Subtheme two relates to motivating pupils to engage in further language learning by fostering interest and openness (N = 5; 13%). A quote from P40 illustrates how both subthemes can come together: “If the pupils are taught in a way that makes them curious of other languages, and make[s] them see similarities and differences between them, I believe they will be more likely to pursue other languages as well—and succeed”.

Table 8.

Main dimensions and main subdimensions (where applicable) of participants’ cognition about teaching EFL in a way that prepares pupils to learn additional languages. Mentions are given as a percentage of the total number of participants, followed by the absolute number of mentions. More than one theme or subtheme can be present in a single participant’s answer.

A second main reason was the perceived importance of knowing languages (N = 14; 26%). Apart from making general statements about the importance and value of knowing languages (N = 5; 9%), the participants referred mainly to needs that are brought about by globalization (N = 9; 17%), whether “global” and “intercultural” communication in general, the demands of the labor market, or increasingly diverse societies. As P9 expressed it, “we live in a multi-cultural society in a globalized world”.

3.4. Pre-Service Teacher Cognitions about Including Other Languages

In order to investigate pre-service teachers’ cognitions about including languages other than English in the EFL classroom, the participants were asked the following question: “Would you include languages other than English in the English classroom?” (Item Four). The participants were then presented with a yes/no option again and asked to elaborate on why they would or would not do so. Thirty-six participants (67%) answered affirmatively. Fifteen participants (28%) answered in the negative, and three (6%) indicated both yes and no.

We identified three main reasons for answering negatively (see Table 9). The first reason was concern about insufficient exposure to English (N = 7; 13%). The number of hours allocated to English is already quite limited at elementary school, and our participants expressed concern that the exposure time would be decreased even further if other languages were included. Secondly, the participants were concerned about leaving pupils confused and the inclusion of other languages proving too challenging as the participants felt that learning English alone was already a challenge (N = 5; 9%). Last but not least, the participants stated their own lack of knowledge of other languages as a reason (N = 4; 7%). The explanations that were given by participants who indicated both yes and no coincided with those given for negative answers but the “yes and no” participants seemed more undecided.

Table 9.

Participants’ cognition about including other languages: main dimensions of the participants’ negative answers. Mentions are given as a percentage of the total number of participants, followed by the absolute number of mentions. More than one theme can be present in a single participant’s answer.

Thirty-three of the 36 participants answering yes gave some further explanation. These included a wide range of topics with a single mention, ranging from promoting cross-cultural/cross-linguistic awareness to enhancing pupils’ “metacognitive thinking” (P40) and decisions being dependent on the specific class and topic. However, we identified three main tendencies with regard to including languages other than English (see Table 10).

Table 10.

Participant cognition about including other languages: main dimensions and subdimension(s) in participants’ positive answers. Mentions are given as a percentage of the total number of participants, followed by the absolute number of mentions. More than one theme or subtheme can be present in a single participant’s answer.

First of all, almost a third of the pre-service teachers (N = 15; 28%) would want to draw on their pupils’ home languages, for two different reasons. Eleven participants (20%) set this in relation to language learning goals, arguing, for example, that it would lead to deeper understanding: “[If] I have pupils in class who speak other languages, I would also involve them and ask how you say different words in that language. This could lead to a deeper understanding of the different languages” (P48; our translation). Four participants (7%) stated that their reason was acknowledging the pupils’ different cultural and linguistic backgrounds: “I think it needs to be an awareness xxx the multiple cultures that are present in the Norwegian classroom today. Acknowledging languages is also acknowledging and including students in the classroom with a different cultural background” (P2). Secondly, nine participants (17%) specifically mentioned wanting to include Norwegian. The main reason given for this was supporting pupils’ understanding (N = 7; 13%). As P41 put it: “Also, I think I will use Norwegian to make sure they understand, but hopefully not to [sic] much”. Last but not least, our participants would include additional languages for the purpose of cross-linguistic comparison (N = 10; 19%). They would especially want to look at similarities and differences in order to promote learning (N = 7; 13%). This supports the findings for subtheme one, language learning strategies, described in Section 3.3. Five of the pre-service teachers (9%) explicitly stated that they wanted to draw on their pupils’ background languages for this purpose. Only one participant (P4) connected a cross-linguistic strategy to using Norwegian: “It can be useful to compare language structures with the language they [the pupils] already know, whether it is Norwegian or another language” (our translation).

3.5. Pre-Service Teacher Cognitions about Which Languages to Include and Why

As a follow-up to Item Four, the participants were asked, “If your answer in question 4 was yes: Which languages would you include and why?” (Item Five). The majority of our findings in Section 3.5 echo and confirm those described in Section 3.3 and Section 3.4. All of the participants answered the question, and again the languages represented in the classroom (i.e., the pupils’ home languages) were those mentioned most frequently as the languages they would want to include (N = 18; 33%; see Table 11).

Table 11.

Other languages participants would include in the EFL classroom. Mentions are given as a percentage of the total number of participants, followed by the absolute number of mentions. More than one language can be present in a single participant’s answer.

For the most part, the participants did not elaborate on which languages these were. However, some languages were mentioned explicitly, including Arabic, German, and Russian, which can be considered fairly typical immigrant languages in the Norwegian context. The second most frequently mentioned languages were again Norwegian (N = 17; 31%)8, followed by Spanish (N = 12; 22%), German (N = 10; 19%), and French (N = 6; 11%).

We identified two main reasons for our participants’ choice of languages (see Table 12). The most prominent reasoning behind the participants’ language choice was again cross-linguistic comparison and exploiting the relationship between languages so as to enhance learning (N = 15; 28%). Apart from making general statements, such as “[b]ecause it can help some students to see the similarities and differences between Norwegian and English, when learning English” (P9), the participants also emphasized more specific aspects such as pupils being able to connect new to existing linguistic knowledge (P21 and P43). As P43 writes, “it could help the students to understand English if they could relate it to their native language”. In a similar vein, four participants (7%) referred to the usefulness of exploring linguistic similarities, such as similarities in vocabulary (P8 and P40), loan words (P42), and similar sentence structures (P51), which, in the opinion of some of the participants, could also lead to increased metalinguistic awareness (P37 and P40). Interestingly, not only Norwegian (see above), German, French, and Spanish were mentioned in the context of language comparison, but also Latin and Greek: “Maybe Greek, Latin, and French if anything. This is because these languages are the basis for English, and it would be helpful to see the connection” (P11).

Table 12.

Main dimensions of participants’ cognition about why to include other languages. Mentions are given as a percentage of the total number of participants, followed by the absolute number of mentions. More than one theme can be present in a single participant’s answer.

When looking more closely at the reasons why teachers may want to include pupils’ home languages, cross-linguistic comparison was reconfirmed as the main reason. Seven (13%) of the 10 participants who elaborated stated that they wanted to use these languages to foster language learning through cross-linguistic comparison and exploiting the similarities between languages. The same was true of the participants’ motivation to include Norwegian, which contrasts with our findings in Section 3.4. The reason most frequently given for including Norwegian was now cross-linguistic comparison (N = 7; 13%). Drawing on Norwegian for other teaching-related purposes, such as providing explanations and classroom management, was the second most frequently cited reason (N = 5; 9%). Some participants also gave the simple reason of Norwegian being “our L1” (N = 4; 7%).

The second main reason (N = 6; 11%) for the choice of languages was their perceived usefulness for international communication. Not surprisingly, the main languages named, apart from Norwegian, were three major European languages: Spanish, German, and French. These coincide with the main foreign languages offered in Norwegian high schools.

3.6. Pre-Service Teachers’ Perceptions of the Importance of Cross-Linguistic Metalinguistic Awareness

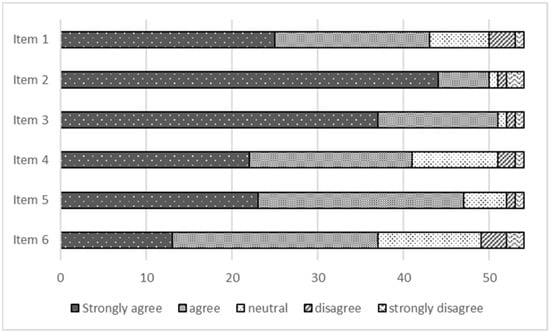

A six-item Likert scale (see Section 2.2) was administered to the participants in order to examine the importance pre-service teachers attribute to cross-linguistic metalinguistic knowledge and skills which necessitate a pluralistic approach to teaching in the EFL classroom. As the results in Figure 1 and Table 13 show, our participants predominantly agreed or strongly agreed with all of the Likert scale items. There was no difference between knowledge items, reflecting the importance of metalinguistic knowledge, or skills items, reflecting metalinguistic ability. This means that the participants overwhelmingly agreed that it is important for pupils to develop cross-linguistic knowledge and skills. However, some aspects of these seemed to be more controversial than others.

Figure 1.

Perceived importance of developing cross-linguistic knowledge and skills by item and number of participants.

Table 13.

Perceived importance of developing cross-linguistic knowledge and skills: agreement rates.

Items 2 and 3 had the highest agreement rates. Ninety-four percent of the participants (N = 51) agreed or strongly agreed that it is important that pupils can use knowledge and skills acquired in one language to learn another (Item 3). Similarly, 93% (N = 50) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that it is important that pupils know that one can build on similarities between languages in order to learn languages (Item 2). Items 2 and 3 were also the items with which the highest percentage of participants agreed strongly (81% and 69%, respectively). Common to both items is that they are fairly general statements that resonate with major themes identified in the qualitative data, namely developing language learning strategies (see Section 3.3) and exploiting the similarities between languages (see Section 3.3, Section 3.4 and Section 3.5), from the perspective of metalinguistic knowledge (“know that one can build on”) and metalinguistic ability (“can use”).

Slightly fewer participants (N = 47; 87%) agreed or strongly agreed that it is important that pupils can identify their own reading strategies in the first language (L1) and apply them to the second language (L2) (Item 5). Nine percent (N = 5) chose the middle of the scale for Item 5, indicating that they were unsure whether to consider this important or not. Four percent (N = 2) disagreed or strongly disagreed. Yet again fewer participants (N = 43; 80%) agreed or strongly agreed that it is important that pupils know that certain “loan words” have spread across a number of languages (for example, taxi, computer, hotel) (Item 1). Four participants (7%) disagreed or strongly disagreed with Item 1, and seven (13%) were unsure. It is somewhat surprising that fewer participants agreed or strongly agreed with Item 1 than with Item 2 since Item 1 could be considered a specification of Item 2.

Seventy-six percent of the participants (N = 41) agreed or strongly agreed that it is important that pupils know that each language has its own sound system (Item 4). At the same time, a comparatively high number of participants (N = 10; 19%) were unsure whether to consider this important or not. The most controversial statement turned out to be it is important that pupils can compare sentence structures in different languages (Item 6). Here, the highest number of participants (N = 5; 9%) disagreed or strongly disagreed, and the highest number (N = 12; 22%) indicated that they were unsure. Nevertheless, 69% (N = 37) agreed or strongly agreed with this statement, even if the percentage that strongly agreed was also the lowest of all items (N = 13; 24%). Regardless, it is surprising that the results are much lower than for Item 2 since it could be argued that the two are related: building on similarities between languages arguably requires comparisons to be made between them. Item 6 could thus have been interpreted as a skill included in Item 2, which is more abstract and knowledge-related. There are several possible explanations for this. First of all, Item 2 may have been perceived as more useful since it explicitly includes a purpose, “in order to learn other languages,” whereas Item Six may have been interpreted as referring to grammar exercises in their own right. In addition, Item 2 leaves it open which similarities are being referred to. In the light of the participants’ future careers as elementary school teachers, they may have considered sentence structure as too challenging since it is arguably more complex than, for example, similarities and differences in the lexicon.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we employed a questionnaire with open and closed-ended items to investigate (1) how Norwegian pre-service teachers of English conceptualize multilingualism, (2) the cognitions that these pre-service teachers have about EFL classes promoting multilingualism (based on their own school experience), (3) their cognitions about laying the foundations for LLLL in their future EFL teaching, and (4) their cognitions about using a pluralistic approach in their future EFL teaching. Finally, we used a 5-point Likert scale based on FREPA to study (5) these pre-service teachers’ cognitions about the importance of promoting cross-linguistic awareness in the EFL classroom. Many of our results confirm earlier findings for pre-service teachers (discussed in Section 1) and show, once more, that pre-service and in-service teacher cognitions are similar when it comes to multilingualism and pluralistic approaches.

In our survey, we found that Norwegian pre-service EFL teachers conceptualized multilingualism along three central dimensions. The main aspects mentioned—and in which their conceptualizations differed—were the number of languages involved (at least two vs. several), which kinds of competence(s) multilingualism involves (e.g., active vs. passive), the individual/social dimension, and the situational context of multilingualism (e.g., school and work). These reflect current and past discussions in linguistics (cf. Romaine 2017; Cenoz 2013).

The great majority of the participating pre-service teachers had a positive view of the contribution that learning English at school can make to developing multilingualism, even though multilingualism here seems to have been interpreted mainly as adding English to one’s linguistic repertoire. However, a substantial number of our participants also addressed the usefulness of learning English for learning subsequent languages, for example, by allowing learners to develop cross-linguistic strategies. Participants who did not agree that learning English would contribute to multilingualism mainly cited insufficient quality of teaching as the reason, which does not mean that these participants did not value the potential contribution of EFL teaching.

The great majority of the pre-service teachers were also open to laying the foundations for LLLL in the EFL classroom, in other words, to teaching in a way that prepares pupils for learning additional languages. The most prominent reason for this was to facilitate the skills and mindset that many of them seemed to deem important in this context: language-learning strategies, especially a cross-linguistic strategy, and an interest in and openness toward languages and language-learning. A substantial proportion of the participants also referred to the importance of knowing languages in the wider context of globalization as a reason for wanting to teach in this way. On the other hand, the main reason against a more open approach to teaching English seemed to be rooted in a concern that the core of the subject, namely teaching and learning the English language, would be compromised—a concern that is shared by in-service teachers (e.g., Jakisch 2014).

When asked more specifically about a pluralistic approach (i.e., including languages other than English in the EFL classroom), the pre-service teachers were far more skeptical, which mirrors previous findings for pre-service teachers (e.g., Iversen 2021 but see Cybulska and Borenic 2014) and in-service teachers (e.g., Arocena et al. 2015). Almost one-third of the participants did not want to include other languages, again mainly because they were concerned about the already limited amount of time that pupils are exposed to English, but also because they feared placing a greater demand on pupils’ cognitive abilities. However, over two-thirds of the participants were open to the idea of including other languages.

The participating pre-service teachers would want to include mainly the pupils’ home languages, and the majority-culture language, followed by the more widely spoken European languages typically taught in the national education system. Previous studies have found that pre- and in-service teachers were less inclined to draw on the full spectrum of linguistic repertoires that their pupils bring to the classroom than on the languages used and taught in the education system (e.g., Iversen 2021; Rodríguez-Izquierdo et al. 2020; Daryai-Hansen et al. 2019). Against this backdrop, we find it promising that roughly one-third of our participants explicitly mentioned wanting to include the languages represented in the classroom or, in other words, the pupils’ home languages. Including any of these languages appeared to be motivated mainly by a wish to use them for cross-linguistic comparison, to exploit similarities and differences in order to enhance language learning. Another main reason, however, especially in relation to the majority culture language, was to foster comprehension in the EFL classroom. A second, lesser motivation for the choice of languages was the perceived importance of these languages for international communication, which ties in with our other findings and with earlier studies in the field (Cybulska and Borenic 2014).

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has used FREPA as a research tool. Since our Likert-scale results are aligned with the other findings in the survey, our study shows that FREPA can be a valuable tool for creating scales that elicit cognitions about cross-linguistic awareness. When the pre-service teachers were directly presented with FREPA statements about the importance of different aspects of cross-linguistic awareness, they highly valued cross-linguistic knowledge and skills—much more so than was evident from the qualitative part of our study, where we had already identified cross-linguistic comparison as an important recurrent theme (see Section 3.3, Section 3.4 and Section 3.5). However, the participants’ perception of its importance varied from item to item. The more general the statement and the more “buzz words” such as “strategies” it contained, the more the participants tended to agree with it. We interpreted this as insecurity regarding the details of how to promote and make use of cross-linguistic awareness that is analogous to being positively inclined toward preparing pupils for LLLL and cross-linguistic comparison (Section 3.3), but skeptical about a pluralistic approach (Section 3.4). As we included only FREPA items for which a pluralistic approach is considered essential and as the mean agreement rate for all items combined was 83% (“strongly agree” and “agree” combined), even participants who said that they would not include other languages in the classroom (28%; Section 3.4) thus indirectly recognized the need for a pluralistic approach.

Last but not least, we would like to address some caveats. The findings in this study are, of course, subject to all the general challenges in investigating cognitions, to which we have only indirect access. First of all, it is impossible to know whether the participants’ answers faithfully reflect their cognition about a certain topic or whether they instead gave answers that they thought were expected and acceptable in the given context. We tried to reduce this risk by making the questionnaire anonymous, emphasizing that there were no right or wrong answers, and employing methodological triangulation in regard to cognitions about pluralistic approaches. Secondly, a written questionnaire does not allow for follow-up questions, which could have helped to clarify the participants’ answers and to shed light on additional layers of cognition. Furthermore, it should be remembered that if a participant did not mention a certain theme or dimension, this does not automatically mean that the participant would disagree with it or not consider it to be important if directly prompted. However, we are confident—despite these caveats—that our findings provide a good overview of what Norwegian pre-service teachers of English consider important in relation to laying the foundations for multilingualism through pluralistic approaches to teaching. We are also confident that the results are a good point of departure for subsequent studies.

5. Conclusions

The present study set out to investigate, from a Norwegian perspective, pre-service teachers’ cognitions about laying the foundations for multilingualism in elementary school EFL teaching, with special reference to pluralistic approaches and cross-linguistic awareness. Overall, we found that the great majority of the pre-service teachers held a favorable view of promoting multilingualism as part of EFL teaching. They also viewed positively pluralistic approaches in the EFL classroom. Finally, the pre-service teachers overwhelmingly agreed that it is important for pupils to develop cross-linguistic awareness. However, a positive attitude does not necessarily translate into corresponding practice once pre-service teachers begin their professional practice. Bearing in mind the growing linguistic diversity in today’s classrooms and plurilingualism as an educational goal (see Section 1), knowledge about multilingualism, pluralistic approaches, and cross-linguistic awareness—as well as a corresponding pedagogical repertoire--need to be firmly anchored in teacher education programs so that future teachers of English can not only use their pupils’ multilingualism as a resource but can also successfully contribute to promoting plurilingualism in all pupils. It remains to be seen whether policy changes, such as the new teacher education guidelines in Norway (UHR 2018), will also lead to changes in implementation. Awareness of and a positive attitude toward these topics are, however, a good starting point for further training.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.-O. and A.-K.H.S.; methodology, C.M.-O. and A.-K.H.S.; software, not applicable; validation, C.M.-O. and A.-K.H.S.; formal analysis, C.M.-O. and A.-K.H.S.; investigation, A.-K.H.S.; resources, Western Norway University of Applied Sciences; data curation, C.M.-O. and A.-K.H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.-O.; writing—review and editing, C.M.-O. and A.-K.H.S.; visualization, C.M.-O.; supervision, C.M.-O.; project administration, C.M.-O. and A.-K.H.S.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to full anonymity of the participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was waived due to full anonymity of the participants.

Data Availability Statement

Data available from the first author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the pre-service teachers who participated, for their time and effort.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | We will be using the terms multilingualism and plurilingualism interchangeably, in the sense of an individual’s full repertoire of languages and language varieties (CoE 2007) as opposed to societal multilingualism. |

| 2 | Here, we mean children who grow up with either two or more home languages or a home language that is different from the respective country’s majority language(s). |

| 3 | These may also be referred to as plurilingualism-inspired approaches, plurilingual approaches, or multilingual approaches. In the following, we will use all four terms synonymously. |

| 4 | Throughout this paper, we will be using the term English as a Foreign Language (EFL) in order to emphasize the formal educational setting of our study, namely EFL teaching at elementary school in Norway. In instances where studies we reviewed defined their own context as English as a Second Language (ESL), we have kept the original terminology. In addition, we would like to point out that there is an ongoing debate as to whether the English language has the status of a foreign language in Norway or that of a second language (cf. Rindal 2014, 2020; Speitz 2020; Simensen 2010). It has, in fact, been argued that English in Norway (and in many other countries) is currently in transition from EFL to ESL (e.g., Rindal 2020). |

| 5 | LK06 was still in use when the data for the present study were being collected. |

| 6 | The core elements describe the most important content (e.g., topic areas, terminology, methods) pupils need to learn in order to master a subject and to make use of what they have learned. |

| 7 | Percentages in the text are given in relation to the total number of participants (N = 54). Absolute numbers and percentages indicate the prominence of a theme in the overall data set. More than one theme or subtheme can be present in a single participant’s answer. |

| 8 | Norwegian is, in the context of the present study, the majority culture language and would often be the dominant home language. It is not clear how many participants implicitly included Norwegian in their conceptualization of home languages, but most of the participants seemed to mean languages other than Norwegian when referring specifically to pupils’ home languages. Participants’ reasons for including home languages and for including Norwegian are therefore considered separately. |

References

- Alisaari, Jenni, Leena Maria Heikkola, Nancy Commins, and Emmanuel O. Acquah. 2019. Monolingual ideologies confronting multilingual realities. Finnish teachers’ beliefs about linguistic diversity. Teaching and Teacher Education 80: 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arocena, Elizabet, Jasone Cenoz, and Durk Gorter. 2015. Teachers’ beliefs in multilingual education in the Basque country and in Friesland. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education 3: 169–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arocena, Miren Elizabet. 2017. Multilingual Education: Teachers’ Beliefs and Language Use in the Classroom. Ph.D. thesis, University of the Basque Country, Leioa, Spain. Available online: https://addi.ehu.es/bitstream/handle/10810/25839/TESIS_AROCENA_EGA%c3%91A_MIREN%20ELISABET.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Beacco, Jean-Claude, Michael Byram, Marisa Cavalli, Daniel Coste, Mirjam Egli Cuenat, Francis Goullier, and Johanna Panthier. 2016. Guide for the Development and Implementation of Curricula for Plurilingual and Intercultural Education. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok, Ellen. 2001. Bilingualism in Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok, Ellen, Fergus I. M. Craik, and Gigi Luk. 2012. Bilingualism: Consequences for mind and brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 16: 240–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borg, Simon. 2006. Teacher Cognition and Language Education: Research and Practice. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, Simon. 2018. Teachers’ beliefs and classroom practices. In The Routledge Handbook of Language Awareness, 1st ed. Edited by Peter Garrett and Josep M. Cots. London: Routledge, vol. 1, pp. 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, Simon. 2019. Language teacher cognition: Perspectives and debates. In Second Handbook of English Language Teaching. Edited by Xuesong Gao. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1149–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelier, Michel. 2003. L’éveil aux Langues à L’école Primaire. EVLANG: Bilan D’une Innovation. Brussels: de Boeck. [Google Scholar]

- Candelier, Michel, Antoinette Camilleri-Grima, Véronique Castellotti, Jean-François de Pietro, Ildikó Lörincz, Franz-Joseph Meissner, Artur Noguerol, and Anna Schröder-Sura. 2012a. FREPA. A Framework of Reference for Pluralistic Approaches to Languages and Cultures: Competences and Resources. Graz: European Centre for Modern Languages/Council of Europe. Available online: https://www.ecml.at/Resources/ECMLresources/tabid/277/ID/20/language/en-GB/Default.aspx (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Candelier, Michel, Petra Daryai-Hansen, and Anna Schröder-Sura. 2012b. The framework of reference for pluralistic approaches to languages and cultures: A complement to the CEFR to develop plurilingual and intercultural competence. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching 3: 243–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, Jasone. 2013. Defining multilingualism. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 33: 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, Jasone, and Alaitz Santos. 2020. Implementing pedagogical translanguaging in trilingual schools. System 92: 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]