Abstract

Communicative expertise in the host society’s dominant language is central to newcomers’ socio-professional integration. To date, SLA research has largely ignored laypeople’s perspectives about Lx communicative expertise, though they are the ultimate judges of real-life interactional success. Sociolinguistic studies have shown that laypeople may base their judgments of Lx speech not only on linguistic criteria, but also on extralinguistic factors such as gender and language background. To document laypeople perspectives, we investigated the professional characteristics attributed to four ethnolinguistic groups of French Lx economic immigrants (Spanish, Chinese, English and Farsi) who were nearing completion of the government-funded French language training program in Quebec City, Canada. We asked L1 naïve listeners (N = 49) to evaluate spontaneous speech excerpts, similar in terms of content and speech qualities, produced by a man and a woman from each target group. After they listened to each audio excerpt, we asked listeners to select the characteristics they associated with that person from a list of the most frequent professional qualities found in job advertisements. Data analysis showed that few Lx users were perceived as having strong communication skills in French. Logistic regression revealed no significant relationships between language group, gender, communicative effectiveness, and professional characteristics. However, there were significant associations between communicative effectiveness with the following characteristics: can work independently, can relate to others, is dynamic, has a sense of initiative, and shows leadership skills.

1. Introduction

In their 2016 article, the Douglas Fir Group proposed a transdisciplinary framework to unify second and additional (henceforth Lx) language acquisition research endeavours. Their framework highlights three levels of interrelated influences that shape Lx learning experiences: the micro level focuses primarily on the Lx learner/user and their developing repertoires, the meso level focuses on the sociocultural institutions and communities where learning may take place (e.g., schools, work settings, social organizations), and the macro level focuses on the ideological conditions of the Lx learning context. Their framework prioritises empirical attention to the affordances and constraints provided by the social-local world in which Lx learners and users evolve.

Though only a very small fraction of SLA literature focuses on adult Lx learning in migratory contexts (Plonsky 2017; Ortega 2019; current call for contributions for this special issue), the micro perspective, focusing on immigrants’ language learning trajectories and outcomes, is represented (e.g., Adamson and Regan 1991; Diskin and Regan 2015, 2017; Forsberg Lundell and Bartning 2015; Forsberg Lundell and Arvidsson 2021), as is the meso level, focusing on descriptions of curricular or teaching practices found in language training programs for adult immigrants (e.g., Murray and McPherson 2006; Strube 2010; Wedin and Norlund Shaswar 2019). Some SLA researchers have bridged the micro and meso perspectives to focus on Lx learners who have been enrolled in or recently completed a government-funded language training program (e.g., Derwing and Munro 2013; Norton Peirce 1993, 1995; Reichenberg and Berhanu 2019; White et al. 2002; Wong et al. 2001; Yates et al. 2014). This combined body of literature has shown that, for these learners, Lx learning is not only agentive, but also dynamic and shaped by a myriad of individual cognitive and psychological factors in addition to the perceived quality of instruction. These findings have informed theory about conditions that favour or hinder optimal Lx learning and have also inspired policy and curricular changes (i.e., focus on the development comprehensibility instead of accent reduction as a result of Dewring and Munro’s research program).

The current study aims to expand the SLA literature on Lx learning in different migration contexts by taking a macro perspective focused on target community ideologies that may affect perceptions of Lx economic immigrants’ language skills. We examine the relationship between learner characteristics, including gender and language background, and target community laypeople’s perceptions. We collected spontaneous speech excerpts from Lx learners completing the Programme d’intégration linguistique pour immigrants (PILI), a government-funded French language training offered Quebec newcomers. We matched the samples for speech qualities and presented them to L1 naïve listeners (N = 49). After listening to each excerpt, judges associated characteristics frequently mentioned in job advertisements with each speaker.

2. Background

2.1. Effect of Perceived Communicative Expertise on L1 Listeners’ Evaluation of Lx Speakers’ Characteristics

It is widely accepted that communicative expertise1 in the majority language of the host community mediates newcomers’ general well-being (Kim et al. 2012) and employment outcomes (Lang 2021). Due to its central role in the resettlement process of newcomers, Lx immigrants’ communicative expertise has attracted broad scientific interest. Researchers have documented target language learning outcomes of Lx adult learners and have established communicative expertise using self-assessment reports (e.g., Stevens 1999; Piller 2002), tasks/tests that predict general proficiency in the target language (based on constructs established in SLA theories, e.g., Cherciov 2011) and/or other empirically-measured aspects of communicative ability (e.g., comprehensibility in Derwing and Munro’s research program). However, as Sato and McNamara (2019) argue, laypeople’s perspectives (i.e., untrained language professionals) about Lx communicative expertise have been largely ignored both in the SLA and language testing literature, though laypeople are the “ultimate arbiters in real-life interactions as what counts as success” (p. 898; for an exception see Derwing and Munro (2013) who asked 16 English L1 petrochemical company workers to identify a preferred voice from pairs of Mandarin Lx and Slavic Lx accented English).

Furthermore, sociolinguists interested in resettlement trajectories have argued that communicative expertise alone does not facilitate successful socio-professional integration or upward mobility (Harrison 2014). In fact, L1 listeners play a determining role. Research has shown that speaker identity cues (e.g., age, gender, cultural background, etc.) influence listeners’ judgments about speaker personality, such as how warm or resourceful a person is. These evaluative reactions ultimately encourage or hinder Lx economic immigrants’ socio-professional integration, regardless of actual expertise in the target language (Cargile 2000; Deprez-Sims and Morris 2010; Harrison 2014; Meyer 2011). These judgments are largely a reflection of societal biases or ideologies circulating among target community members (Lippi-Green 2012). By studying L1 listener perceptions of Lx speech, researchers can document the macro level of Lx learning experiences (Douglas Fir Group 2016) and reveal the potential effects of societal intergroup dynamics on Lx economic immigrants.

To our knowledge, only three studies have specifically documented L1 listener perceptions of the relationship between Lx speaker characteristics and their communicative expertise. Wible and Hui (1985) examined the relationship between perceived communicative expertise (operationalized as command of the target language) and social characteristics of Chinese Lx speakers. In this study, nine Chinese L1 speakers listened to picture stories narrated by six Chinese Lx women and then rated their communicative expertise, operationalized as a general impression of language skills (correct grammar, accurate pronunciation, wide use of vocabulary, fluency and sounds authentic as natives), using a 9-point Likert scale (1 = very poor, 9 = L1 speaker). A different group of Chinese L1 speakers (N = 20) listened to the same stories and rated the speakers on 22 social characteristics (e.g., ambitious, competent, intelligent) on a 6-point scale (1 = not at all; 6 = extremely). A separate two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to analyze speaker effect on the traits attributed by the listeners, and the relation with the oral proficiency judgment. The results indicated that eight social characteristics (competent, serious, comfortable, ambitious, creative, mature, intelligent, and openness towards Chinese people) were strongly correlated with high communicative expertise. Characteristics related to personality (e.g., friendly, proud) or physical appearance (e.g., attractive, plain-looking) did not correlate with L1 listeners’ communicative expertise perception. These findings suggest that in a Chinese context, perceived communicative expertise in the target language appears to be associated with speaker status (i.e., judgments about speakers’ competence and upward, social mobility) and integration into the target language community.

White and Li (1991) also investigated the relationship between perceived communicative expertise (operationalized as command of the target language) and perceived social characteristics in English Lx and Chinese Lx. L1 raters (108 American English and 112 Chinese speakers) evaluated five speech samples (two male and three female) per language, each of which had been previously evaluated for proficiency level by expert judges. They rated the Lx speakers of their L1 on a ten-point semantic differential scale (e.g., good—bad). A multivariate repeated measure analysis of variance (MANCOVA) was performed to analyze the effect of communicative expertise and gender on the judgments of four trait dimensions. No effect of Lx speakers’ gender was found in either listener group. Regardless of gender, more proficient Chinese and English Lx speakers were rated as more intelligent, more ambitious and more competent, corroborating the association between communicative expertise and speaker status observed in Wible and Hui (1985). Those perceived as more experts in the target Lx were also perceived as physically stronger and more active than their less communicatively competent peers. Physical strength and activity are sometimes combined in sociolinguistic studies under the construct dynamism (e.g., Gallois and Callan 1981). Interestingly, the most proficient Chinese speaker of English was rated less positively than the most proficient American English speaker of Chinese, which suggests that Lx speakers of higher status languages may be granted more linguistic capital than their peers, as attested in research on attitudes towards accented speech (see Lindemann et al. 2014).

Last, Llurda (2000) further explored the relationship between comprehensibility (i.e., ease of understanding), communicative expertise, and social perceptions of Lx speakers by L1 listeners. Twelve women from different language backgrounds (Spanish, Russian, Mandarin, Hindi and Japanese) read aloud a 100-word passage in English. An English phonetics expert first made an impressionistic rating of the speech samples and assessed that they represented a range of proficiency levels (from low intermediate to near native). Then, using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not very; 5 = very), 28 L1 naïve listeners rated the same speech samples on comprehensibility, command of English (communicative expertise), and social characteristics related either to speakers’ status (intelligent, well educated, leadership ability, and hard-working) and solidarity (likeable, physically attractive, sense of humour, and trustworthy). Results revealed that scores associated with both comprehensibility and command of English were highly correlated. These constructs were, in turn, also highly correlated with three characteristics associated with speaker status (intelligent, well educated, and leadership ability), and two characteristics (likeable and trustworthy) related with what sociolinguistics literature refers to as speaker solidarity (i.e., their warmth, or presence of soft skills). It is worth noting that this study was the first to include evaluation of perceived communicative expertise by naïve L1 listeners making the association between that construct and social characteristics even more robust as discrepancies between expert and naïve judgments of oral proficiency have been observed (e.g., Bridgeman et al. 2012; Kang et al. 2019).

These three studies that have explored the link between communicative expertise and Lx speakers’ characteristics have established that when L1 listeners are asked to rate speech samples that vary in terms of communicative expertise, more experts Lx speakers generally tend to be granted more linguistic capital (i.e., their language resources are conferred greater value, see Bourdieu 1982) than their lower proficiency peers, regardless of speaker gender (White and Li 1991) or speaker L1 background (Llurda 2000). A different picture emerges, however, when L1 listeners are asked to rate speech samples produced by Lx speakers of comparable in terms of communicative expertise.

2.2. Effects of Social Identity Cues on L1 Listeners’ Evaluation of Lx Speakers’ Characteristics

Research has shown that L1 listeners may hold implicit social biases that likely affect how they perceive Lx speakers (Lindemann and Subtirelu 2013). This tendency is well illustrated in Gilchrist and Chevrot (2017). The researchers asked 184 French L1 listeners divided into two groups to rate the same speech sample recorded by an Arabic L1 female speaker. One group of judges (n = 93) was explicitly told they would rate the communicative expertise (operationalized as command of the target language) and academic potential of an Arabic L1 speaker. The second group (n = 91) was not told the origin of the speaker and when asked to determine her origin, were not able to correctly identify her as an Arabic speaker. Results showed that the speech sample was judged significantly differently by the two groups of L1 listeners. The L1 listeners who were informed that the speech sample was produced by an Arabic L1 speaker reacted more negatively, rating her communicative expertise and academic potential significantly lower than the other group of L1 listeners. These findings further corroborate the association between perceived communicative expertise and speaker status. The presence of differential evaluative reactions was explained in terms of activation of different expectations and stereotypes in the perceptual encoding of information of both groups of L1 listeners, which resulted in a negative evaluation of the speaker believed to belong to a negatively stereotyped group in France. The trend showing the presence of evaluative hierarchies is, in fact, well documented in research investigating attitudes towards Lx speakers matched in terms of communicative expertise (i.e., verbal guise experiments), both in general (e.g., Dragojevic and Goatley-Soan 2020) or work-related (Hosoda and Stone-Romero 2010) evaluative contexts. For example, in the United States, speech samples of comparable communicative expertise produced by job applicants from a French L1 or Chinese L1 background were evaluated positively for high-status jobs. This was because these Lx speakers were perceived as having equal status as members of the dominant group; Spanish L1 background applicants were, however, rated negatively for such a position (Cargile 2000; Hosoda and Stone-Romero 2010). In the specific societal context of the current study, (Beaulieu et al., forthcoming a, forthcoming b) have found that French Lx speakers perceived, by French L1 listeners in Quebec City, to come from Latin America or Western Europe were rated positively, unless they were associated with a former colonizing nation. In that case, they were evaluated as unfavourably as speakers from Asia.

It is worth noting that these studies have typically involved the evaluation of speech samples produced only by male Lx speakers. When researchers have presented listeners with speech samples produced by both male and female speakers from different language groups and closely matched in terms of communicative expertise (Gallois and Callan 1981; Beaulieu et al., forthcoming a, forthcoming b), they have still found that some language groups were rated more positively than others, but also that male and female speakers of the same language group were rated differently. The nature of the evaluations tended to parallel the gender stereotypes circulating in society. This body of literature thus indicates that the evaluation of groups of speakers, matched in terms of communicative expertise, may be biased by other social identity cues, with language background and gender of speaker likely intervening in the attribution of social characteristics.

3. The Current Study

Section 2.1 showed that perceived communicative expertise in the Lx tends to be invariably associated with speakers’ status (e.g., intelligent, competent, and ambitious). Other associations have been inconsistently observed across research contexts such as positive relationships with target community members (Wible and Hui 1985), speakers’ dynamism (White and Li 1991) or speakers’ solidarity (Llurda 2000). It is important to note, however, that these findings emerged from studies focusing on evaluation of speech samples dissociated from any communicative contexts. Since evaluation is dependent on the interactional space occupied by speakers (Harrison 2014), the reported observations have yet to be replicated in a more contextualized setting where Lx speakers’ language skills will likely be under scrutiny, such as workplace settings.

In addition, the studies reviewed in Section 2.1 suggest that evaluation of communicative expertise by naïve L1 listeners is solely based on actual speakers’ linguistic abilities and is not influenced by extralinguistic factors since effects of speaker identity have not been observed (i.e., speaker gender and speaker L1 background). It may be, however, that the absence of association is attributable to study design as speech samples produced by male and female speakers (White and Li 1991) or by speakers from different L1 backgrounds (Llurda 2000) were not matched in terms of communicative expertise. This may have blurred the potential effects of such social identity cues and prevented the activation of implicit social biases observed in the studies reviewed in Section 2.2.

To further explore the relationship between perceived communicative expertise and Lx speakers’ social characteristics and document societal biases or community-based ideologies, the current study focused on a specific population: male and female Lx speakers from four different language groups. Speakers were nearing completion of a government-funded language training program specifically designed for Lx adult newcomers. To address the limitations of previous studies exploring this relationship, we designed a verbal guise questionnaire set in a work-related evaluative context. The current study thus seeks to expand the scope of such inquiries by considering the effect of speaker gender and language background on perceived communicative expertise and personality evaluation in a work setting. In particular, the current study addresses the following research questions:

- (1)

- To what extent are male and female economic immigrants from different language backgrounds (Farsi, Spanish, English, Chinese) nearing completion of the PILI perceived by naïve L1 listeners to possess communicative expertise in French Lx?

- (2)

- What is the relationship between perceived communicative expertise and professional characteristics made by the same L1 listeners?

4. Methodology

4.1. Context

This study is part of a research program investigating intergroup relations in Quebec City, the capital city of the French-speaking Canadian province of Quebec. Quebec City is Canada’s seventh largest metro area, with an estimated metro population of 827,000 (with over 500,000 in the city itself, ISQ, 2019). It is a largely monolingual and monocultural French-speaking city where the immigration rate is on the rise (Bourque 2018). The research program focuses on four of the language groups which currently contribute the most to the transformation of the ethnocultural landscape of the city: English; Spanish, Mandarin, and Farsi2. The English-speaking community of Quebec City represents 1.4% of the total population (7395 residents; Statistics Canada 2017). This community is made up of descendants of the historic community as well as economic immigrants from the United States (Valiante 2019) and has access to English-medium schools, churches, health care services and community centres. Our previous studies have shown that L1 French L1 listeners tend to hold negative attitudes towards English Lx speakers of French (Beaulieu et al., forthcoming a, forthcoming b), likely the results of long-lasting historical tensions between French- and English-speaking Quebecers3. Quebec City has been home to a small Chinese community since the 1960s and is currently made up of 2500 residents (Statistics Canada 2017). Our previous research also documented negative attitudes towards the Chinese population, which we attributed to the community’s negative portrayal in Quebec media. Quebec City’s Hispanic community was established in the 1980s and currently counts 6425 residents (Statistics Canada 2017). Spanish-L1 speakers of French are perceived significantly more positively than English L1 and Chinese L1 speakers. Indeed, French L1 speakers report a degree of cultural affinity, likely due to common Latin origins and religious heritage (see Armony 2017). Finally, the Iranian community was established much more recently and is much smaller (500 residents; Statistics Canada 2017). Interestingly, our studies have shown that L1 listeners generally attributed a Western identity to Farsi Lx speakers of French who were in turn rated as favourably as Spanish speakers (Beaulieu et al., forthcoming a, forthcoming b).

4.2. The Speech Samples Used in the Questionnaire

For the current study, we designed a computer-based verbal guise questionnaire hosted on LimeSurvey with speech samples from Beaulieu et al. (2021). Speakers performed a semi-controlled oral production task (i.e., professional voicemail message), which offers the advantage of eliciting spontaneous naturalistic speech while maintaining similar message content across speakers (Dupere 2018).

All speakers were university-educated economic immigrants completing the final level of the PILI. The main objective of this program is for learners to reach the eighth level (equivalent to B2) of the Quebec proficiency scale for adult immigrants (see Quebec Government 2011), which is considered the threshold of linguistic autonomy. The eighth level corresponds with the ability to hold a professional white-collar position or pursue post-secondary studies in an entirely French-speaking environment (MIFI 2019). Findings from Beaulieu et al. (2021) showed that few learners actually displayed the language abilities expected to have been mastered at this level.

We thus presented naïve L1 listeners with speech samples that were representative of the average learners of that level (as established in Beaulieu et al. 2021), and which differed only in terms of gender and language group. Thus, from the 31 speech samples collected in Beaulieu et al. (2021), we selected eight (one male and one female from each of our four target language groups) that were rated similarly in terms of fluency, comprehensibility, accentedness, dynamism, and irritability by l3 language experts, using a 9-point Likert scale (i.e., their average scores on each construct differed by less than one point out of 9). To ensure that judges remained attentive to the evaluation task, we diversified our sample with distractors from two French Lx speakers (one woman and one man) who received significantly lower scores than the 8 target voices. The average length of each recording in the task was about 20 s. This duration is typical of verbal guise experiments because it is “sufficient for participants to make systematic speaker evaluations” (Kircher 2016, p. 199). In fact, first impressions literature suggests that interpersonal judgments made under very limited time exposure do not significantly differ from opinions based on much longer time intervals (see Carney et al. 2007).

4.3. Professional Characteristics Evaluated in the Questionnaire

We previously identified the most sought-after professional characteristics listed in public white-collar job offers in Quebec City and used these as a basis for the evaluation of the speech samples: holds a bachelor’s degree, can work independently, shows leadership, has a sense of initiative, can relate to others, can establish and maintain positive working relationships, is dynamic, is honest, can manage interpersonal issues with tact and sensitivity, is reliable and communicates efficiently (Beaulieu et al., forthcoming b). A frequent criticism of verbal guise questionnaires is that listeners may not share the same interpretation of certain characteristics (Garrett 2010). To address this issue, we asked five French L1 speakers to tell us how they defined ‘communicates efficiently’. A content analysis of their responses showed that they understood this construct as the ability to get their ideas across, an interpretation that aligned with the judges’ observations in Sato and McNamara (2019). Given this consensus, we were confident that ‘communicates effectively’ could serve as a proxy for communicative expertise in the current study.

4.4. Procedure

Thirty-nine women and ten men (N = 49) between the ages of 16 and 59 served as judges in the study. We used the official Facebook pages (between 2000 and 5550 members) of Quebec City neighborhoods (e.g., Comité citoyen de Saint-Roch-Ville de Québec, Faubourg Saint-Jean-Baptiste) to recruit judges. All were long-term Quebec City region residents, the majority of whom held a university degree in a variety of fields, including administration/marketing, engineering, education and social services. Since recent research has demonstrated that first impressions made under limited time exposure translate into categorical attributions (rather than scalar or nuanced ones, see Wingate and Bourdage 2019), we asked our L1 listeners to engage in categorical evaluative processes. We told them to imagine that we were consulting them about candidates that should be considered for a white-collar position. They were asked to listen to each speech sample and select the professional characteristic(s) that they believed were representative of the Lx speaker. Judges could also add characteristics to the 11 pre-set choices, but seldom made use of that option. Prior to assessing the speech samples, the listener group familiarized themselves with the question format in a training session. The questionnaire ended with background questions. The total experimental protocol lasted about 20 min.

5. Results

5.1. First Research Question

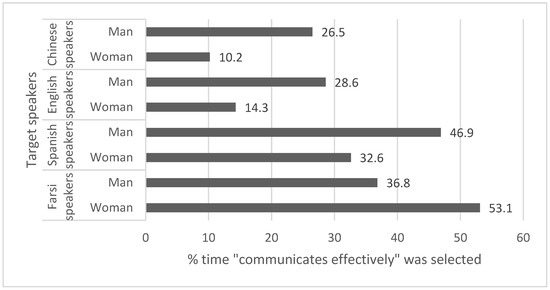

To answer the first research question (To what extent are male and female economic immigrants from different language backgrounds [Farsi, Spanish, English, Chinese] nearing completion of the PILI perceived by naïve L1 listeners to possess communicative expertise in French Lx?), we tallied the number of times the 49 listeners had selected “communicates effectively” from the list of 11 characteristics, for each of the 8 speech samples (for a total of 392 possibilities). Results show that Lx speakers from the four language groups were seldom perceived as being able to communicate effectively in French (122/392 or 31.1%). In addition, male speakers appeared to be rated slightly more positively than female speakers (17.3% vs. 13.8%, respectively). To determine whether the overall trend was representative of both male and female speakers of the four target language groups, we then calculated the number of times the characteristic “communicates effectively” was selected for each speech sample representing our four language groups.

Figure 1 shows that the language groups were not rated similarly. The Spanish and Farsi speakers were generally perceived as being more competent speakers of French than the Chinese and English speakers, with the Farsi-speaking woman considered to be best communicator by the majority of participants followed by the Spanish-speaking man. Figure 1 also reveals that, overall, male and female speakers appeared to be rated differently, with the men being judged as more efficient speakers of French than the women in all language groups but Farsi, where the opposite trend was observed.

Figure 1.

Listeners’ perception of communicative effectiveness across gender and language groups.

To determine whether the observed differences were significant, we conducted a two-way repeated measures ANOVA. The analysis showed a main effect for language group (F (3,336) = 9.36, p < 0.001) and gender (F (1,336) = 4.90, p < 0.028). We also observed a significant interaction among the two factors (F (3,336) = 3.80, p < 0.011). Consequently, we carried out a series of pairwise Bonferroni comparisons to determine the various levels of interaction between different factors.

We first tested the effect of gender and found no significant differences within language groups, except for the Chinese speakers. The male speaker was perceived as more proficient, significantly more often, than the female speaker (p = 0.272). We then tested the effect of language group and found significant differences between female speakers (p < 0.0001) but not between male speakers (p = 0.081). The female Farsi speaker was perceived as being more competent significantly more often than the Chinese (p < 0.0001) and English-speaking women (p = 0.0002). The Spanish-speaking woman was also perceived as being more competent significantly more often than the Chinese-speaking woman (p = 0.28).

5.2. Second Research Question

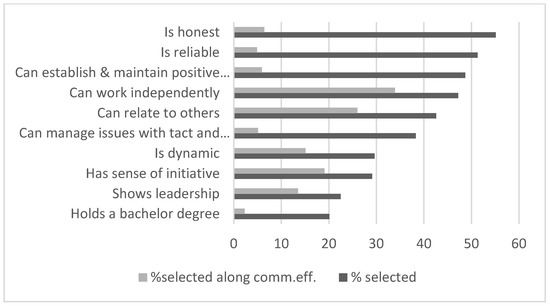

To answer our second research question (What is the relationship between perceived communicative expertise and professional characteristics made by the same L1 listeners?), we first identified which other professional characteristics were selected by the L1 listeners. Then, we identified which of those were selected when the speaker was considered a competent speaker of French. Figure 2 shows in dark grey the rank of general attribution of professional characteristics to our eight Lx speakers. It reveals that the three most often attributed characteristics are associated with solidarity (is honest, is reliable, can maintain and establish positive working relations) and the three least often selected are related to speaker status (has a sense of initiative, shows leadership, holds a bachelor’s degree). Figure 2 also shows that this attributional pattern changes when the speaker was perceived to communicate effectively in French (light grey line).

Figure 2.

Professional characteristics attributed to Lx speakers.

The analysis revealed a strong association between communicative effectiveness and the professional characteristics can work independently and can relate to others (i.e., they were selected between 60% and 70% of the time along with communicative effectiveness). In addition, a moderate association (they were selected between 40 and 60% of the time) was found between communicative effectiveness and three other characteristics (shows leadership, has a sense of initiative, and is dynamic). To establish whether these associations were significant and whether they were representative of all male and female speakers and of all the four target language groups, we analyzed the relationships between language group, gender, perceived communicative effectiveness, and each of the other ten professional characteristics using a generalized linear mixed model with a three-way repeated measures logistic regression. The analysis showed a simple significant interaction between communicative effectiveness and the five characteristics previously described: shows leadership (F (1,328) = 13.63, p < 0.0003), sense of initiative (F (1,328) = 4.73, p < 0.0303), can relate to others (F (1,328) = 8.90, p < 0.0031), can work independently (F (1,328) = 13.74, p < 0.0002), and is dynamic (F (1,328) = 7.19, p < 0.0077). All other factors and interactions between factors did not show significant trend differences, except for is dynamic which were attributed significantly more often to the female speakers.

6. Discussion

The present study sought to explore the relationship between perceived communicative expertise and professional characteristics of Lx speakers as a means of documenting societal biases or ideologies circulating in the target community. To do so, we directed our empirical focus on target community members and examined 49 French L1 listeners’ perceptions of four groups of Lx speakers nearing completion of a government-funded French language training program in Quebec City (Canada). To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first attempt to empirically document host community members’ perspective on the language skills displayed by economic immigrants who took part in such a language training program for adult newcomers.

Our first research question aimed to shed light on the extent to which male and female speakers from four different language groups, and representing “regular” graduates from the PILI, were perceived by 49 L1 naïve listeners to possess communicative expertise in French. Our results showed that, as a group, they were generally not believed to possess such expertise (i.e., the characteristic “communicates effectively” was selected only 31.1% of the time). This finding corroborates previous learners’ (Amireault and Lussier 2008; Carrier-Giasson 2017) and researchers’ (Beaulieu et al. 2021) observations concerning the PILI whereby oral language skills do not appear to match stated end-of-program outcomes.

In addition, though the speech samples included in our questionnaire were judged similarly on measures of fluency, comprehensibility, strength of accent, dynamism and irritability by expert raters, they were perceived differently by naïve L1 listeners. This is also in line with previous observations revealing discrepancies between judgments of perceived oral proficiency made by experts and lay judges (e.g., Bridgeman et al. 2012; Kang et al. 2019). This finding may be explained, as previous studies have shown, by the fact that expert and naïve raters focus their attention, and in turn, base their evaluation on different aspects of Lx speakers’ oral performance (e.g., Kennedy and Trofimovich 2008; Sato and McNamara 2019). However, a more likely explanation is the difference in evaluative contexts. While our expert listeners assigned their ratings in a general evaluative context, dissociated from a communicative context (see Beaulieu et al. 2021 for details), the naïve listeners in the current study were required to judge whether the speakers displayed the oral skills required to successfully hold a white-collar position. Our rating task also forced them to engage in categorical evaluative processes. It thus appears that this specific and constrained evaluation context may have compelled the L1 listeners to have considered extralinguistic variables in their evaluation process.

In fact, speaker identity appears to have influenced the evaluation of perceived communicative expertise. On the one hand, men were generally considered to be competent speakers of French more often than women (17.3% vs. 13.8%). On the other hand, the language background of female speakers also appeared to have played a role in the listeners’ evaluation process. We found significant differences between the female Farsi speaker and the English and Chinese women. We also found significant differences between the Spanish- and the Chinese-speaking women. Overall, the Farsi- and Spanish-speaking women were rated more competent most often. Thus, similar to what had been observed in Gilchrist and Chevrot (2017), it seems that the evaluation of communicative effectiveness activated gender and language group biases. In the case of evaluation of communicative effectiveness for a white-collar, high-status position, these biases appear to favour men in general as well as women who are perceived to belong to a positively stereotyped group in the target community (see Beaulieu et al. forthcoming b an evaluative trend generally observed in sociolinguistics studies, but in relation to speaker status (Garrett 2010).

Our second research question sought to explore the relationship between perceived communicative expertise and personality evaluation, in a work-related evaluative context. Our findings showed that judges selected five professional characteristics significantly more often when they perceived the speaker as showing communicative expertise in French. Three of those professional characteristics (shows leadership, has a sense of initiative and can work independently) are related to speaker status, further confirming this association that has been consistently observed across research contexts (Llurda 2000; White and Li 1991; Wible and Hui 1985). This finding is not surprising as perception of target language mastery typically confers speaker status, be it in the L1 or a Lx (see Cargile and Bradac 2001). In addition, similar to previous findings, the association between perceived communicative expertise and speaker status was observed across L1 backgrounds (Llurda 2000) and across gender (White and Li 1991). This finding, however, contradicts Gallois and Callan (1981) who had found that male speakers displaying similar proficiency skills as female speakers were rated more favourably than women on the status dimension. This discrepancy might be explained by the fact that, overall, few speakers were considered competent speakers of French. That small number may have reduced the possibility of speaker identity to surface in our analysis.

In addition, we found that the characteristic can relate to others was selected in combination with communicative expertise nearly 70% of the time. This characteristic appears to be related to what Wible and Hui (1985) described as Lx speakers’ relations with target community speakers. This association, also pertinent for the current study, was explained in terms of implicit biases held by L1 listeners about what it takes to become a competent Lx speaker: to develop high levels of communicative expertise, one must be able to embrace the perspective of others. Similar to the association between communicative effectiveness and the three characteristics associated with speaker status, the selection can relate to others was not differentiated by speaker gender or language background.

Finally, the characteristic dynamic was also selected with communicative effectiveness across language groups but attributed significantly more often to women. The association between communicative expertise and perceived dynamism with female speakers belonging to different L1 backgrounds was previously observed in Llurda (2000), though this study included only female speech samples. The nature of our data does not allow us to explain why only this specific characteristic appeared to be associated with gender biases. Indeed, previous studies had shown the presence of gender stereotypes with attributes related to status (favouring men) and solidarity (favouring women) (e.g., Gallois and Callan 1981).

Also pertinent to discuss are other characteristics that were not associated with communicative effectiveness in our data set. The first characteristic which stands out is holds a bachelor’s degree, which was the least frequently selected characteristic (20.1%) and hardly ever selected in combination with perceived communicative expertise. It thus appears that our L1 listener samples held the belief that Lx speakers are, in general, poorly educated. This preconceived opinion is, however, unfounded as economic immigrants taking part in the PILI typically hold a university degree from their home country (MIFI 2017). Four other characteristics (is honest, is reliable, can establish and maintain positive working relations and can manage interpersonal issues with tact and sensitivity) were among the most often selected characteristics, but showed a very weak association with communicative effectiveness (selected in combination between 4.9% and 6.1% of the time). This trend is in line with Wible and Hui (1985) who showed that personal qualities related to speaker solidarity were judged as independent from language expertise.

A personal observation made by an L1 listener4 (see Excerpt 1) seems to confirm this observation, but also indicates that this distinction combined with social desirability biases may have artificially boosted the selection of these four characteristics.

Excerpt 1.

I listened to the speech sample and immediately noted the qualities I perceived. But after doing so, I often realized that I hadn’t selected many qualities which made me question whether I was being racist. So, I often went back to the list of qualities and said to myself: “well, just because she’s still learning French doesn’t mean she’s not honest or reliable” … But the other qualities that were more work-related, I still told myself, “she’s not yet capable of displaying them in French”. I chose these specific [work-related] qualities only when I felt that the person was really at ease in French5.

This participant’s comments shed invaluable light on his evaluative process. It not only shows that perceived communicative expertise was a mediator of person evaluation in a work-related evaluative context, but it also illustrates the clear distinction made between professional and more general personal attributes.

Curricular Implications

Overall, our findings revealed some of the ideological forces Lx speakers may face as they complete a language training program. First, since judges evaluated these university-educated Lx speakers as not possessing the communicative expertise required for a high-status, white-collar position, it may be more difficult for these Lx speakers to find employment that matches their professional qualifications. In addition, despite matching the Lx speakers in our sample in terms of speech qualities and PILI level, we found discrepancies in the ratings indicating that the return on investment may not be the same for all French Lx learners. For example, men and women who were perceived as belonging to positively stereotyped language groups were judged as more competent speakers of French. Of course, ideological stances favouring some Lx speakers over others is not unique to Quebec City. It is indeed highly likely that past and present intergroup dynamics of any migration context will shape the experiences and integration paths of newcomers (Lasagabaster 2006). Though differential evaluations based on gender and language background in social and workplace settings will likely always happen, curricular changes in language training programs may be able to mitigate or at least raise Lx learners’ awareness about these issues. First, Lx learners should engage in candid discussions about these issues, as exemplified by the School Kids Investigating Language and Society (SKILLS) program which invites minority speakers in the United States to reflect on the relationship between their language resources and their (attributed) identity. This approach enhances speaker agency because they identify possible plans of action to assert their place as legitimate Lx speakers (Larsen-Freeman 2019). Second, additional investment in programs that facilitate interaction between adult newcomers and target community members (e.g., Human libraries, BANQ 2017) and/or in programs that raise awareness of existing target community biases (e.g., Derwing and Munro 2014) would also be highly beneficial.

7. Conclusions

The present study contributes to the SLA literature on Lx learning in migration contexts by shedding light on what the Douglas Fir Group (2016) refers to as the macro level of Lx learning experiences. By investigating target community members’ perceptions, our findings have highlighted that though completion of government-funded language training program is thought to provide Lx learners with the communicative expertise necessary to be hired in French-speaking workplaces, such outcome may, at best, be uncertain. Indeed, as Duff (2019) argues, Lx learning does not occur in a vacuum, but rather in a symbolically and culturally coded environment, and language practices inevitably face subjective evaluations. Though Lx speakers from negatively stereotyped language groups may objectively display similar language resources as those used by speakers perceived to belong to a positively stereotyped group, they will unlikely be granted the same linguistic capital. These findings thus call for more research initiatives taking into consideration the specificities of the social-local language learning contexts not only to document, as we have done, the state of the linguistic market in which Lx users evolve, but more importantly to experiment ways in which changes in that linguistic market can be introduced. This study is not, however, without limitations. First, it focused on a very narrow work-related context (one white-collar position) in a city largely populated by white-collar workers (Langlois 2017). Further research is needed to explore the same research questions, but in relation to a variety of jobs desired by economic immigrants and in other immigration contexts. Moreover, the speech samples presented to the LI listeners were judged to show comparable speech qualities by expert raters. Since experts and lay judges tend not to base their evaluation on the same speech characteristics, further research could consider including speech samples that have previously been judged by naïve listeners. This methodological precaution would further strengthen the observed relationship between communicative expertise and professional characteristics. Finally, further research, employing mixed-method design with introspective measures, is needed to identify the linguistic and extralinguistic features associated with these speaker judgments. Reaction time measurements would also help shed further light on how speech samples are processed, with fast reaction times reflecting unconscious, deeply seated opinions and slower reaction times more likely an afterthought resulting from social desirability biases (Álvarez-Mosquera and Marín-Gutiérrez 2018).

Nevertheless, despite certain limitations, this study provides invaluable insights into how the evaluative processes impacts Lx speakers’ professional credibility in their target language environment. We hope that our findings may be used to justify the implementation of curricular innovations that will help all Lx newcomers gain linguistic and cultural capital in their new community.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and L.M.F.; Data curation, J.B.; Formal analysis, J.B. and L.M.F.; Funding acquisition, S.B., L.M.F. and K.R.; Methodology, S.B.; Project administration, S.B.; Writing—original draft, S.B.; Writing—review & editing, J.B., L.M.F. and K.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, grant number 430-2018-00848.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Université Laval (2018-239 Phase II A-3 R-2/28 January 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In this study, we chose to adopt the term communicative expertise (Hall et al. 2006) to refer to Lx users’ display of communicative repertoires (i.e., the language resources on which they draw to participate in their social worlds). It is an umbrella term encompassing similar constructs named differently in other research traditions, such as (perceived) language proficiency (e.g., White and Li 1991) or command of the target langue (e.g., Gilchrist and Chevrot 2017). |

| 2 | Another Lx representative community in Quebec city is Arabic L1 users who received formal schooling in French in their home country (i.e., Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia or Lebanon). Their oral skills were rated significantly higher than the other four groups who had received similar average ratings (see Beaulieu et al. 2021), and were thus excluded from the current study. |

| 3 | Indeed, Engish-speaking Quebecers long made up the economic elite of the province. Social and professional upward mobility of French-speaking Quebecers was difficult until Bill 101, the Charter of the French Language was ratified in 1977, making French the official language of government agencies and schools, as well as the language of commerce and communication (see Kircher 2014). This change led to increasing economic and social mobility for French-speaking Quebecers and more evenly distributed status and power between French and English speakers. |

| 4 | At the end of the questionnaire, participants were invited to write to the research team if they wished to comment on the study protocole. |

| 5 | Orginal comment made in French: J’écoutais l’extrait et je notais tout de suite les qualités que je percevais. Mais souvent, je trouvais que je n’avais pas donné beaucoup de qualités et ça m’a fait me questionner à savoir si j’étais raciste. Ça fait que souvent je relisais la liste de qualités et je me disais: « ben, c’est pas parce qu’elle est encore en train d’apprendre le français qu’elle n’est pas honnête ou fiable … mais, les autres qualités qui avaient plus rapport au travail, je me disais qu’elle n’était pas encore pas encore capable de les faire valoir en français. Ces qualités-là, je les choisissais quand je percevais que la personne était vraiment à l’aise en français. |

References

- Adamson, H. Douglas, and Vera Regan. 1991. The acquisition of community speech norms by Asian immigrants learning English as a second language: A preliminary study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 13: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Mosquera, Pedro, and Alejandro Marín-Gutiérrez. 2018. Implicit language attitudes toward historically white accents in the South African context. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 37: 238–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amireault, Valérie, and Denise Lussier. 2008. Représentations Culturelles, Expériences D’apprentissage du Français et Motivations des Immigrants Adultes en lien avec leur Intégration à la Société Québécoise: Étude Exploratoire. Québec: Office québecois de la langue française. [Google Scholar]

- Armony, V. 2017. Les Québécoises et Québécois d’origine Latino-américaine: Une Population Bienvenue mais reléguée? Available online: http://www.mifi.gouv.qc.ca/publications/fr/dossiers/valoriser-diversite/memoires/015_MEM_CILQ.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Beaulieu, Suzie, Leif M. French, Javier Bejarano, and Kristin Reinke. 2021. Cours de français langue seconde pour personnes immigrantes: Portrait des habiletés orales en fin de parcours. Revue Canadienne de Linguistique Appliquée 24: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, Suzie, Kristin Reinke, Adéla Šebková, and Leif M. French. Frothcoming a. I hear you, I see you, I know who you are: Attitudes towards ethnolinguistically marked French Lx speech in a traditionally homogeneous city. Journal of Second Language Pronunciation.

- Beaulieu, Suzie, Kristin Reinke, and Adéla Šebková. Forthcoming b. Compétences professionnelles perçues chex quatre groupes linguistiques de Néo-Québécois de la ville de Québec. Minorités Linguistiques et Société.

- Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec (BANQ). 2017. L’organisation d’une bibliothèque vivante (Fiche d’information No 9). Available online: https://www.banq.qc.ca/documents/services/espace_professionnel/milieux_doc/ressources/bibliotheque_vivante/bibliotheque_vivante.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1982. Ce que parler veut dire. Paris: Fayard. [Google Scholar]

- Bourque, François. 2018. Portrait Statistique des Immigrants de Québec. Le Soleil. September 7. Available online: https://www.lesoleil.com/chroniques/francois-bourque/portrait-statistique-des-immigrants-de-quebec-1d03725cbb3a226815e18e7e65fd8a9b (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Bridgeman, Brent, Powers Donald, Stone Elizabeth, and Pamela Mollaun. 2012. TOEFL iBT speaking test scores as indicators of oral communicative language proficiency. Language Testing 29: 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargile, Aaron. 2000. Evaluations of employment suitability: Does accent always matter? Journal of Employment Counseling 37: 165–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargile, Aaron, and James Bradac. 2001. Attitudes toward language: A review of speaker-evaluation research and a general process model. Annals of the International Communication Association 25: 347–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, Dana R., C. Randall Colvin, and Judith A. Hall. 2007. A thin slice perspective on the accuracy of first impressions. Journal of Research in Personality 41: 1054–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier-Giasson, Nadja. 2017. Le services d’enseignement du français langue seconde et leur contribution à l’intégration de personnes Immigrantes Allophones adultes à Saguenay. Master’s thesis, Université du Québec, Chicoutimi, QC, Canada. Available online: https://constellation.uqac.ca/4134/1/CarrierGiasson_uqac_0862N_10300.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Cherciov, Mirela. 2011. Between Attrition and Acquisition: The Dynamics between Two Languages in Adult Migrants. Doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Deprez-Sims, Anne-Sophie, and Scott B. Morris. 2010. Accents in the workplace: Their effects during a job interview. International Journal of Psychology 45: 417–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwing, Tracey, and Murray Munro. 2013. The development of L2 oral language skills in two L1 groups: A 7-year study. Language Learning 63: 163–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwing, Tracey, and Murray Munro. 2014. Training native speakers to listen to L2 speech. In Social Dynamics in Second Language Accent. Edited by Levis John and Moyer Alene. Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 219–36. [Google Scholar]

- Diskin, Chloé, and Vera Regan. 2015. Migratory experience and second language acquisition among Polish and Chinese migrants in Dublin, Ireland. In Cultural Migrants and Optimal Language Acquisition. Edited by Fanny Forsberg Lundell and Inge Bartning. Bristol, Buffalo and Toronto: Multilingual Matter, pp. 137–77. [Google Scholar]

- Diskin, Chloé, and Vera Regan. 2017. The attitudes of recently-arrived Polish migrants to Irish English. World Englishes 36: 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas Fir Group. 2016. A transdisciplinary framework for SLA in a multilingual world. The Modern Language Journal 100: 19–47. [Google Scholar]

- Dragojevic, Marco, and Sean Goatley-Soan. 2020. Americans’ attitudes toward foreign accents: Evaluative hierarchies and underlying processes. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 43: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, Patricia A. 2019. Social dimensions and processes in second language acquisition: Multilingual socialization in transnational contexts. The Modern Language Journal 103: 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupere, Alyssa. 2018. Les attitudes d’élèves américains à l’égard de la compétence bilingue d’enseignants de FLE. Master’s thesis, Université Laval, Quebec City, QC, Canada. Available online: https://corpus.ulaval.ca/jspui/bitstream/20.500.11794/33295/1/34975.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Forsberg Lundell, Fanny, and Inge Bartning. 2015. Cultural Migrants and Optimal Language Acquisition. Bristol, Buffalo and Toronto: Multilingual Matter. [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg Lundell, Fanny, and Klara Arvidsson. 2021. Understanding High Performance in Late Second Language (L2) Acquisition—What Is the Secret? A Contrasting Case Study in L2 French. Languages 6: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallois, Cynthia, and Victor Callan. 1981. Personality impressions elicited by accented English speech. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 12: 347–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, Peter. 2010. Attitudes to Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist, Claire, and Jean-Pierre Chevrot. 2017. Snap Judgment: Influences of Ethnicity on Evaluations of Foreign Language Speaking Proficiency. Corela Cognition, Représentation, Langage, 15–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Joan Kelly, An Cheng, and Matthew T. Carlson. 2006. Reconceptualizing multicompetence as a theory of language knowledge. Applied linguistics 27: 220–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Gai. 2014. Accent and ‘Othering’ in the workplace. In Social Dynamics in Second Language Accent. Edited by Levis John and Moyer Alene. Boston and Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 255–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hosoda, Megumi, and Eugene Stone-Romero. 2010. The effects of foreign accents on employment-related decisions. Journal of Managerial Psychology 25: 113–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Okim, Donald Rubin, and Alyssa Kermad. 2019. The effect of training and rater differences on oral proficiency assessment. Language Testing 36: 481–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Sara, and Pavel Trofimovich. 2008. Intelligibility, comprehensibility, and accentedness of L2 speech: The role of listener experience and semantic context. Canadian Modern Language Review 64: 459–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sun Hee, John Ehrich, and Laura Ficorilli. 2012. Perceptions of settlement well-being, language proficiency, and employment: An investigation of immigrant adult language learners in Australia. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 36: 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircher, Ruth. 2014. Thirty Years after Bill 101: A Contemporary Perspective on Attitudes towards English and French in Montreal. Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics/Revue Canadienne de Linguistique Appliquee 17: 20–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kircher, Ruth. 2016. The Matched-Guise Technique. In Research Methods in Intercultural Communication: A Practical Guide. Edited by Zhu Hua. Malden: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 196–211. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, Julia. 2021. Employment effects of language training for unemployed immigrants. Journal of Population Economics 35: 719–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlois, Simon. 2017. Québec se rapproche de Montréal. Contact. January 25. Available online: http://www.contact.ulaval.ca/article_blogue/quebec-se-rapproche-de-montreal/?fbclid=IwAR36VzoVklV7rubuyakXQEIzlSi7_gVQYiXsRb9Mc1JuJvbO2AZIJbKXa7k (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Larsen-Freeman, Diane. 2019. On language learner agency: A complex dynamic systems theory perspective. The Modern Language Journal 103: 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasagabaster, David. 2006. Les attitudes linguistiques: Un état des lieux. Ela: Études de Linguistique Appliquée 4: 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, Stephanie, and Nicholas Subtirelu. 2013. Reliably biased: The role of listener expectation in the perception of second language speech. Language Learning 63: 567–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, Stephanie, Janson Litzenberg, and Nicholas Subtirelu. 2014. Problematizing the dependence on L1 norms in pronunciation teaching: Attitudes toward second-language accents. In Social Dynamics in Second Language Accent. Edited by Levis John and Moyer Alene. Boston and Berlin: De Gruyter, pp. 171–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lippi-Green, Rosina. 2012. English with an Accent: Language, Ideology, and Discrimination in the United States. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Llurda, Enric. 2000. On competence, proficiency, and communicative language ability. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 10: 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Jeanne. 2011. Accents et discriminations: Entre variation linguistique et marqueurs identitaires. Cahiers Internationaux de Sociolinguistique 1: 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministère de l’Immigration de la Francisation et de l’Intégration (MIFI). 2017. Portrait des 17 régions Administratives du Québec. Available online: http://www.mifi.gouv.qc.ca/publications/fr/recherches-statistiques/Fiches_Regionales_2017_20180727.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Ministère de l’Immigration de la Francisation et de l’Intégration (MIFI). 2019. Programme d’intégration linguistique pour les Immigrants. Available online: http://www.mifi.gouv.qc.ca/publications/fr/divers/Pili.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Murray, Denise, and Pamela McPherson. 2006. Scaffolding instruction for reading the Web. Language Teaching Research 10: 131–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton Peirce, Bonny. 1993. Language Learning, Social Identity, and Immigrant Women. Unpublished. Doctoral dissertation, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Norton Peirce, Bonny. 1995. Social identity, investment, and language learning. TESOL Quarterly 29: 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Lourdes. 2019. SLA and the study of equitable multilingualism. The Modern Language Journal 103: 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piller, Ingrid. 2002. Passing for a native speaker: Identity and success in second language learning. Journal of Sociolinguistics 6: 179–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plonsky, Luke. 2017. Quantitative research methods. In The Routledge Handbook of Instructed Second Language Acquisition. Edited by Shawn Loewen and Masatoshi Sato. New York and London: Routledge, pp. 505–21. [Google Scholar]

- Quebec Government. 2011. Échelle québécoise des niveaux de compétence en français des personnes Immigrantes Adultes. Available online: https://www.immigration-quebec.gouv.qc.ca/publications/fr/langue-francaise/Echelle-niveaux-competences.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Reichenberg, Monica, and Girma Berhanu. 2019. Overcoming language barriers to citizenship: Predictors of adult immigrant satisfaction with language training programme in Sweden. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 14: 279–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Takanori, and Tim McNamara. 2019. What counts in second language oral communication ability? The perspective of linguistic laypersons. Applied Linguistics 40: 894–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. 2017. Census Profile 2016, Québec, Ville [Census subdivision], Quebec and Canada [Country]. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CSD&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&TABID=1&B1=All&type=0&Code1=2423027&SearchText=quebec (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- Stevens, Gillian. 1999. Age at immigration and second language proficiency among foreign-born adults. Language in Society 28: 555–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strube, Susana. 2010. Conveying meaning: Oral skills of L2 literacy students. TESOL Quarterly 44: 628–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiante, Giuseppe. 2019. Quebec City’s Small Anglophone Community Vibrant and Close-Knit but Faces Precarious Future. The Globe and Mail. September 7. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-quebec-citys-small-anglophone-community-vibrant-and-close-knit-but/ (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Wedin, Åsa, and Annika Norlund Shaswar. 2019. Whole class interaction in the adult L2-classroom: The case of Swedish for immigrants. Apples—Journal of Applied Language Studies 13: 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Cynthia, Noel Watts, and Trlin Andrew. 2002. New Zealand as an English-language learning environment: Immigrant experiences, provider perspectives and social policy implications. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 148–62. [Google Scholar]

- White, Michael, and Yan Li. 1991. Second-language fluency and person perception in China and the United States. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 10: 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wible, David, and Harry Hui. 1985. Perceived language proficiency and person perception. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 16: 206–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingate, Timothy G., and Joshua S. Bourdage. 2019. Liar at first sight? Early impressions and interviewer judgments, attributions, and false perceptions of faking. Journal of Personnel Psychology 18: 177–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Ping, Patricia Duff, and Margaret Early. 2001. The impact of language and skills training on immigrants’s lives. TESL Canada Journal 18: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yates, Lynda, Agnes Terraschke, Beth Zielinski, Elizabeth Pryor, Jihong Wang, George Major, Mahesh Radhakrishnan, Heather Middleton, Maria Chisari, and Vera Williams Tetteh. 2014. Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) Longitudinal Study 2011—2014: Final Report. Sydney: Macquarie University. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).