3. Conditions on DOM in Spanish

In Spanish, the differential object marking (DOM) seems to respond to two general conditions: certain characteristics of the object, and certain properties of the verb.

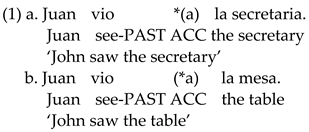

2Consider the following sentences

3:

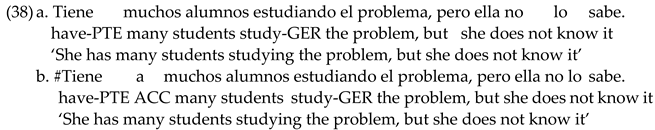

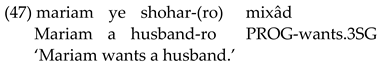

![Languages 07 00114 i001]()

The grammaticality of (1a) shows that a preposition A is mandatory with animate objects, and the impossibility of (1b) shows that the mark is not possible with inanimate objects. Thus, it is possible to establish the following first condition in relation to the Spanish DOM:

The Animacy Condition:

Direct objects can be marked with A if they are animates.

In this article, the topic of DOM in inanimate objects will not be developed; however, I would like to sketch some hypotheses about (2).

4 In cases such as (2a), the inanimate object would have been animated. In (2b), the morpheme A would not be a DOM mark; these are verbs that always govern the preposition A (see

Camacho Ramirez 2019).

5 In (2c), the DOM mark would be DOM, and would express plural. Cases such as (2c) are restricted to verbs that have a feature [quantize] in the verb, according to

Rodríguez-Mondoñedo (

2007). Therefore, we can say that the presence of A with inanimate objects (2) does not override the proposed Animacy Condition.

Tenny (

1987,

1992,

1994) attempts to provide an answer to the problem of the connection between syntax and semantics. The author proposes the AIH (Aspectual Interface Hypothesis), which establishes that: ‘The mapping between thematic structure and syntactic argument structure is governed by aspectual properties’ (

Tenny 1992, p. 2). According to the AIH, the grammar does not need to see the thematic roles, but only certain syntactic/aspectual structures to which the roles are associated. Specifically, the author will focus on the correspondence between two types of arguments: (1) The argument in a semantic representation with the aspectual role of the measure out; and (2) The internal syntactic argument of the verb.

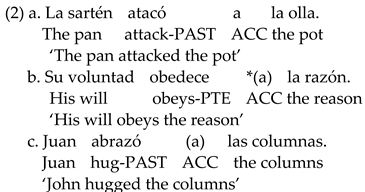

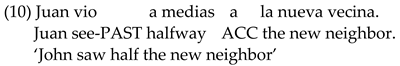

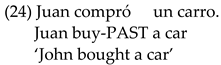

According to Tenny, affectedness can be defined in terms of measure out. The progress of affectedness on the object serves to measure the progress of the event. In the following cases, the progress on half of the object corresponds to half of the progress of the event. Thus, for example, if a piece of music was performed only halfway, the verbal event advances only halfway as well:

The author considers that measure out can interact with delimitation (an ‘endpoint’ at the time of the event). In (3), objects not only measure the event, but they also delimit it.

Tenny (

1987,

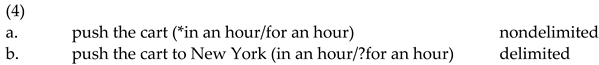

1992) argues that measure out can happen in contexts where the verb delimits the event, but not necessarily:

The morpheme in, which indicates delimitation, is possible only in (4b), where a destination (that delimits) was included. However, in both sentences, the object measures the event, because it is affected by the verb (the object undergoes a change because of the verbal action).

In this article, I will assume Tenny’s notion of measure out (which does not imply the presence of delimitation), although I will use the name affectedness to refer to it, which is perhaps a more common term in the literature.

The fact that there can be affectedness without delimitation implies that there can be not only affectedness in events that delimit (accomplishments and achievements), but also in events that do not delimit (for example, in activities).

According to Tenny, adverbs such as

every day (‘cada día’),

halfway (‘a medias’), and

a little bit (‘un poco’), indicate that the verb affects its object:

![Languages 07 00114 i005]()

As the b sentences of (5) and (6) show, only sentences with an object marked with A are compatible with adverbs that indicate affectedness. These verbs can delimit (5) or not (6).

6With regard to the possibility of having affectedness with verbs that do not delimit,

Tsunoda (

1985) argues that there may be affectedness with activities. Let us look at the author’s affectedness scale: ACTION>PERCEPTION>PURSUIT>KNOWLEDGE>FEELING>RELATION>ABILITY. The perception verbs (e.g., to see, to hear) appear as the seconds that can affect their objects.

Malchukov (

2005) makes a decomposition of the Tsunoda hierarchy into two subscales. The low subscale is defined according to the agent’s volitional control. Perception verbs also appear as seconds that affect their objects: kill>see>like>be cold.

Torrego (

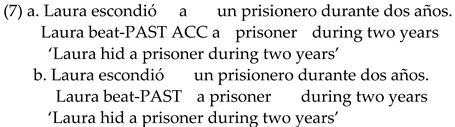

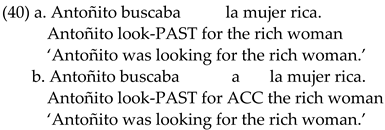

1998) contends that the DOM of Spanish depends on the following factors: agency, specificity, animacy, telicity, and affectedness. With regard to aspect, the author proposes that activity verbs can mark their objects with A:

Sentence (7a) is ambiguous between an activity reading (a repetitive act of hiding; there is no endpoint), where the adverb indicates the time during which various acts of hiding occurred, and an accomplishment reading (a single act of hiding, and, therefore, with an ending), where the adverb indicates the time during which the prisoner was hidden. Sentence (7b) only has the activity reading.

According to the author’s analysis, affectedness in an activity is optional. In the activity reading of (7a), there is affectedness (and the object is marked with A); in (7b), which has only an activity reading, there is no affectedness (and the object is not marked). For Torrego, it is possible to have affectedness with activities.

Torrego claims that there are two types of A-markers: those that express quirky case (which includes affectedness); and those that express structural case (which do not include affectedness):

![Languages 07 00114 i007]()

According to the author, there is necessarily affectedness in the verb golpear (‘to beat’), and the animate object must be marked (8); the verb ver (to see) would have no affectedness. This absence makes the A-marker optional (9). The presence of A with the verb ver depends on the specificity of the object, according to Torrego.

Following

Tsunoda (

1985) and

Malchukov (

2005), I am going to assume that perception verbs that express activity can also affect their objects:

![Languages 07 00114 i008]()

If affectedness is understood as measure out, it is possible that there is affectedness with the verb

ver (to see). Sentence (10) shows the compatibility of the adverb

a medias (halfway), which indicates affectedness (see also (6b)). Affectedness must be understood as an advance of the verbal event on the object. Seen in this way, it is possible to say that perception verbs can affect their objects. Something similar could be said of verbs such as

buscar (‘to look for’):

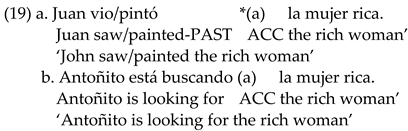

![Languages 07 00114 i009]()

The adverb

un poco más (a little more), which indicates affectedness (measure out), is compatible with the verb

buscar (‘to look for’). It follows that there must be affectedness in this verb. Interestingly, intensional verbs may not mark their object; in this case, the adverb is no more compatible:

![Languages 07 00114 i010]()

Cases (11) and (12) show that the verb

buscar can optionally affect its object. Furthermore, these data corroborate the relationship between affectedness and the A-marker. I return to the data with the verb

buscar in

Section 6.

I have argued so far that affectedness is possible with verbs that delimit (accomplishments and achievements) and with verbs that do not (activities); however, affectedness would not be possible with state verbs. By definition, a state verb does not establish a changing relationship with its object. According to Torrego, state verbs that mark their object with A have agentive subjects. As mentioned, for the author, agentivity is a necessary condition for having DOM in Spanish. Observe the author’s examples:

![Languages 07 00114 i011]()

The subject of (13) is not agentive, and the object cannot be marked with A. In (14), the object can be marked, and its subject is agentive.

On the other hand, Torrego points out that A is mandatory with the verb

odiar (‘to hate’), and is optional with the verb

conocer (‘to know’).

![Languages 07 00114 i012]()

The author explains this difference by arguing that the subject of

odiar is always agentive or “active”, and the subject of

conocer is not necessarily so. On the basis of

Pesetsky (

1995), Torrego contends that verbs of the kind of

odiar denote “active” and transitory emotions and that, therefore, its subject must be agentive.

It seems reasonable to assume that an agentive subject can affect the object. It would not be the agency itself that triggers DOM in Spanish, but rather the affectedness that is caused by this agent. A state event does not have an agentive subject, and its object is unaffected. On the other hand, an agentive subject must change the aspect of a state verb. Verbs such as

conocer (‘to know’), and

amar (‘to love’) (

Juan ama (a) una chica (‘John loves a girl’)), with marked objects, must have undergone a change of aspect, from state to activities.

7The analysis that was made allows us to conclude that the DOM of Spanish is subject to the following condition

8:

The Affectedness Condition: Direct objects marked with A must be affected.

The hypothesis that I defend for the Spanish DOM is the following:

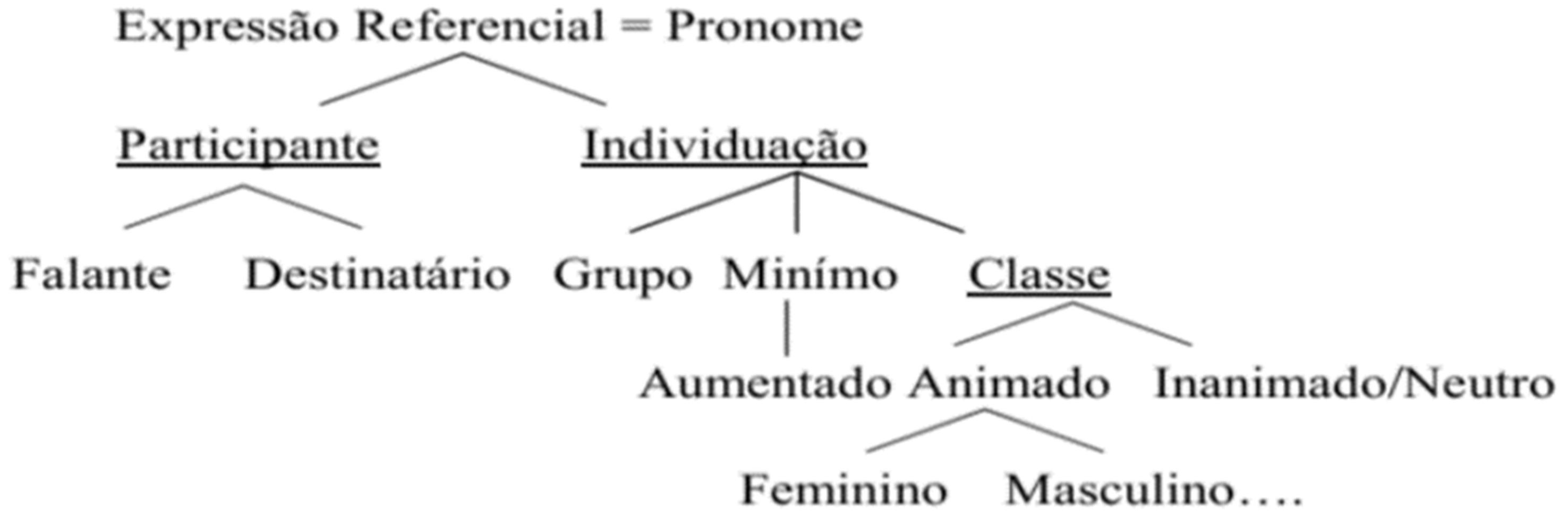

The DOM Hypothesis: The Spanish DOM depends on the licensing of the affectedness feature of the verb by the organizing node class. If class dominates the feature [animate], the object must be marked with A.

The DOM hypothesis joins, in a single explanation, the two DOM conditions in Spanish: the Animacy Condition, and the Affectedness Condition.

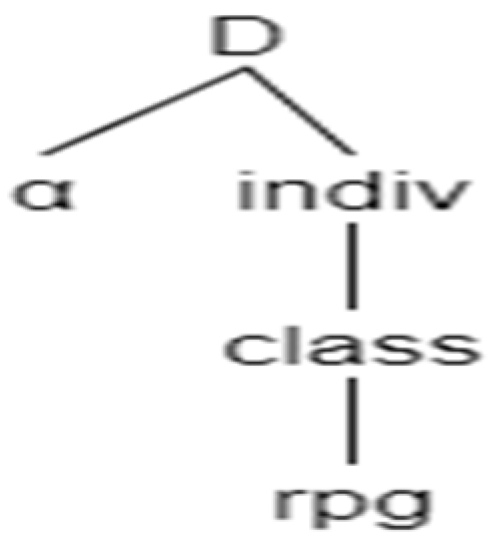

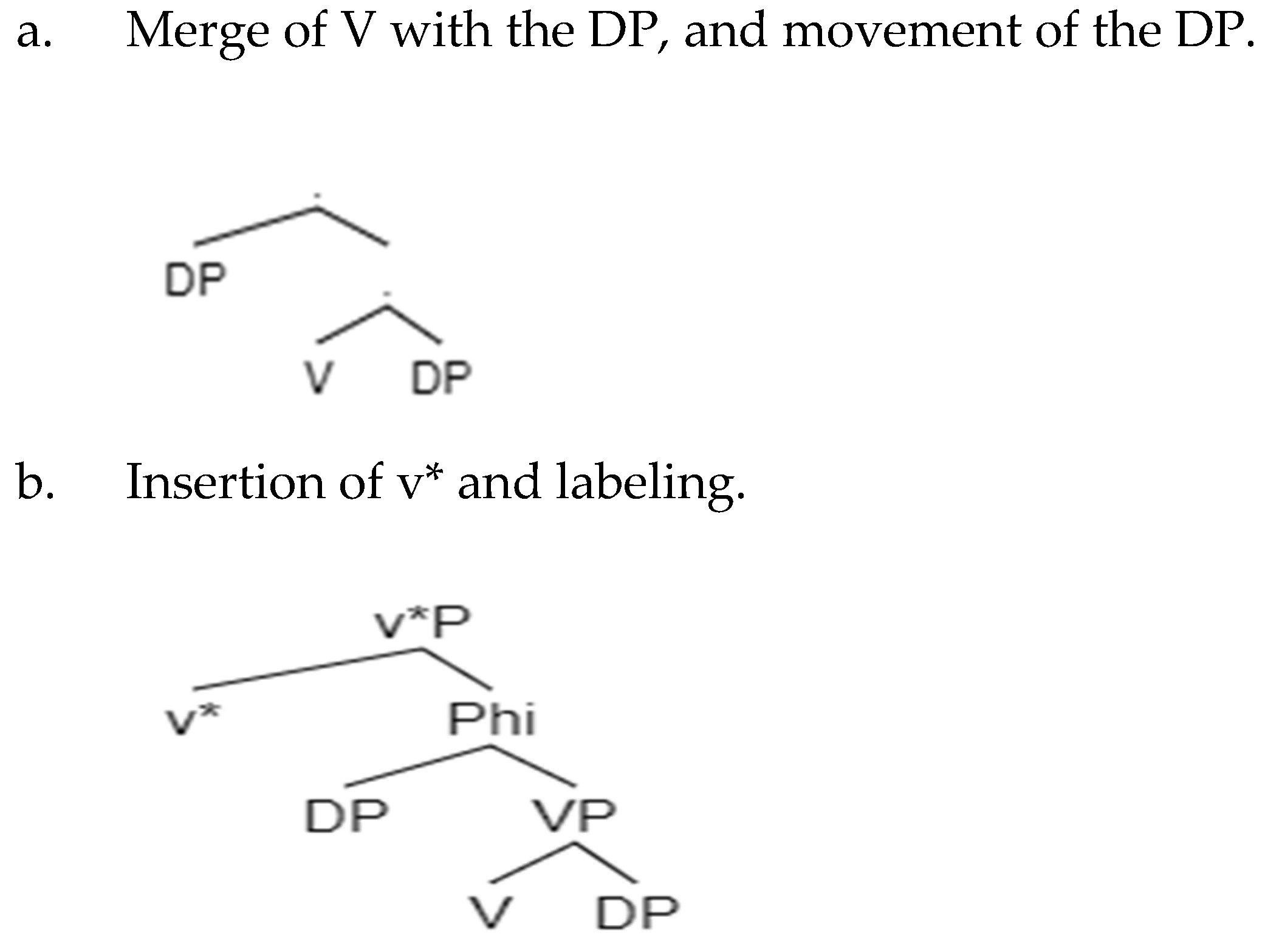

5. Inheritance, Labeling, and DOM

My proposal about the Spanish DOM is that the marked object must be affected, and that the lexical feature affectedness must be licensed with the ON (organizing node) class (of v). If class dominates [anim], there will be DOM. How can class-v license affectedness?

Chomsky’s (

2013,

2015) labeling theory provides a motivation for the existence of movement and agreement in languages. These operations exist to solve projection problems (POP) that appear when two heads or two phrases merge.

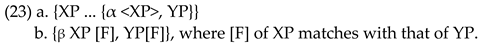

How is a label obtained? Chomsky proposes the existence of a labeling algorithm (LA) that searches the closest head or the least subordinate head of a syntactic object (SO). This head will be the label of the SO:

In (22a), the label will be H because it is the only head. In (22b), there is a projection problem because it has two heads: X for XP, and Y for YP.

Chomsky (

2013,

2015) proposes the following alternatives to generate the label in a context such as (22b):

<XP> is a copy of the moved XP in (23a). Chomsky assumes that copies cannot label, so the LA chooses YP to label. The situation is different in (23b); there is no copy. However, the two phrases share a feature [F]. This shared feature <F,F>, which would be the most prominent feature, is the label of β in (23b). Observe the following case:

![Languages 07 00114 i020]()

At some point in the derivation of (24), v*P (the v of a transitive verb) must merge with the DP

John. We have a projection problem similar to (22b). These two elements do not share an F feature because there is no agreement between them. Here, T appears, which merges with the constituent that merges the v*P and the DP.

20 The DP

John undergoes internal merge (IM) to the specifier position of T. Thus, v*P is the only element that can label because the copies cannot (this time, the DP copy). The solution to the created projection problem is by appealing to (23a). Once v*P is formed, T (a head) must label.

Note that, with the movement of the DP to the specifier position of T, a projection problem of type (22a) was created between the moved DP and the TP. The solution is the sharing of a feature <F,F>, which is a prominent feature.

21 How did this sharing happen? T, which inherited phi features from C (

Chomsky 2008), must establish an Agree relation with the DP (before moving). Thus, when the DP moves to spec,T, the TP already has features that were obtained from the DP itself. Now, it is possible to have the share <F,F>, which will be the label. This time, the solution to the projection problem was by appealing to (23b).

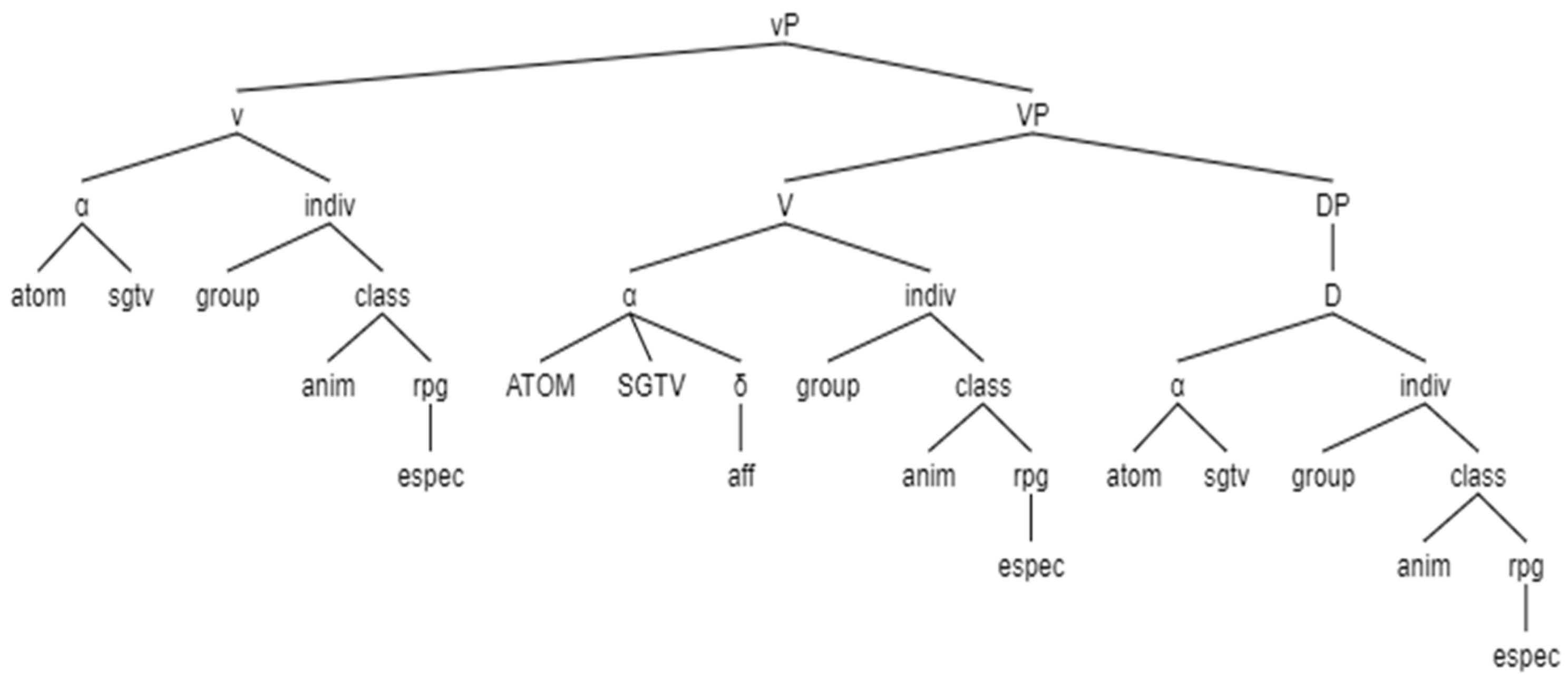

Let us look in more detail at labeling in the v* phase, according to Chomsky. Observe

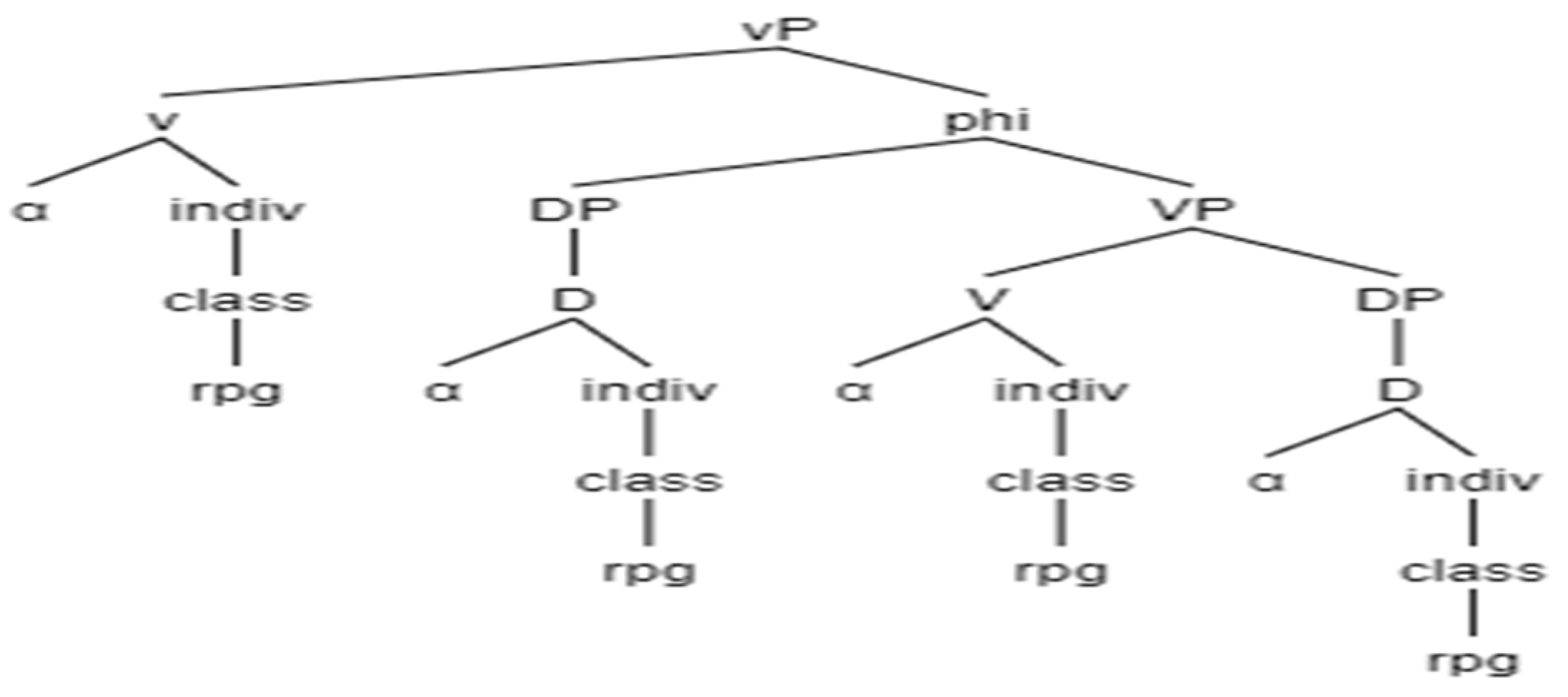

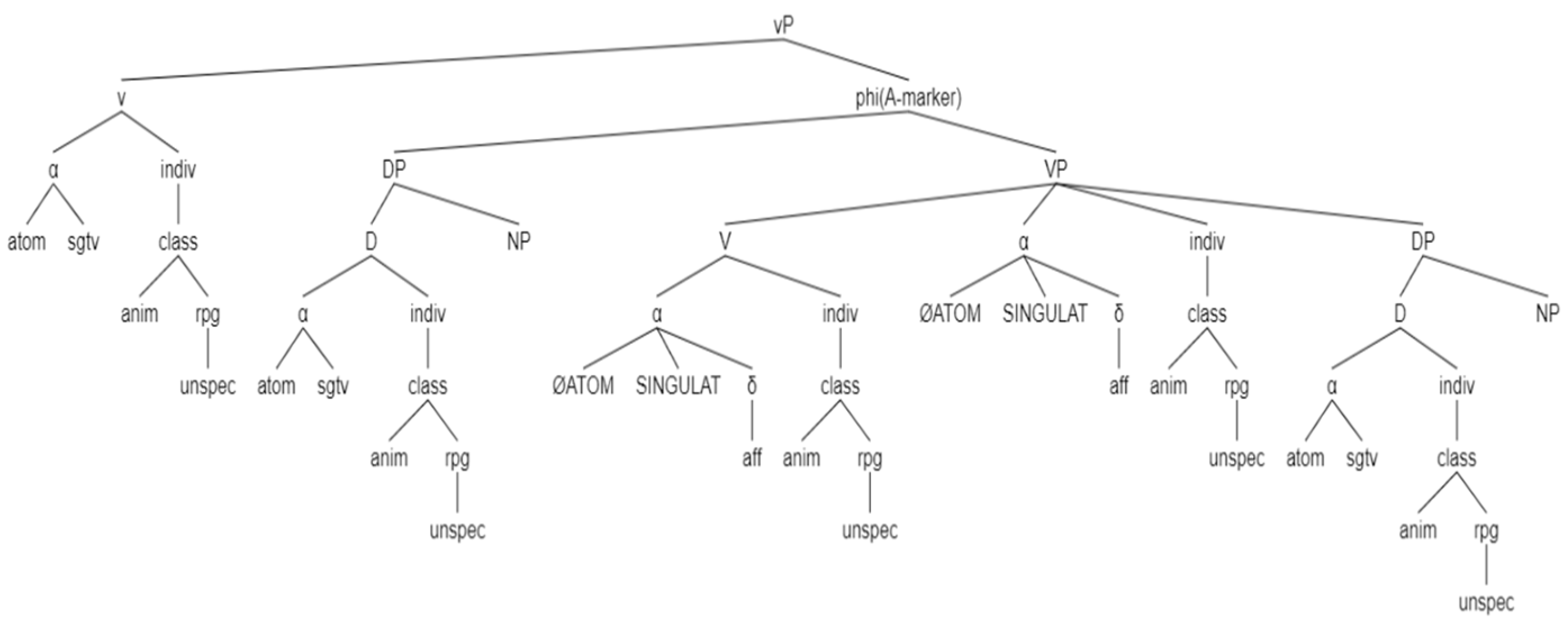

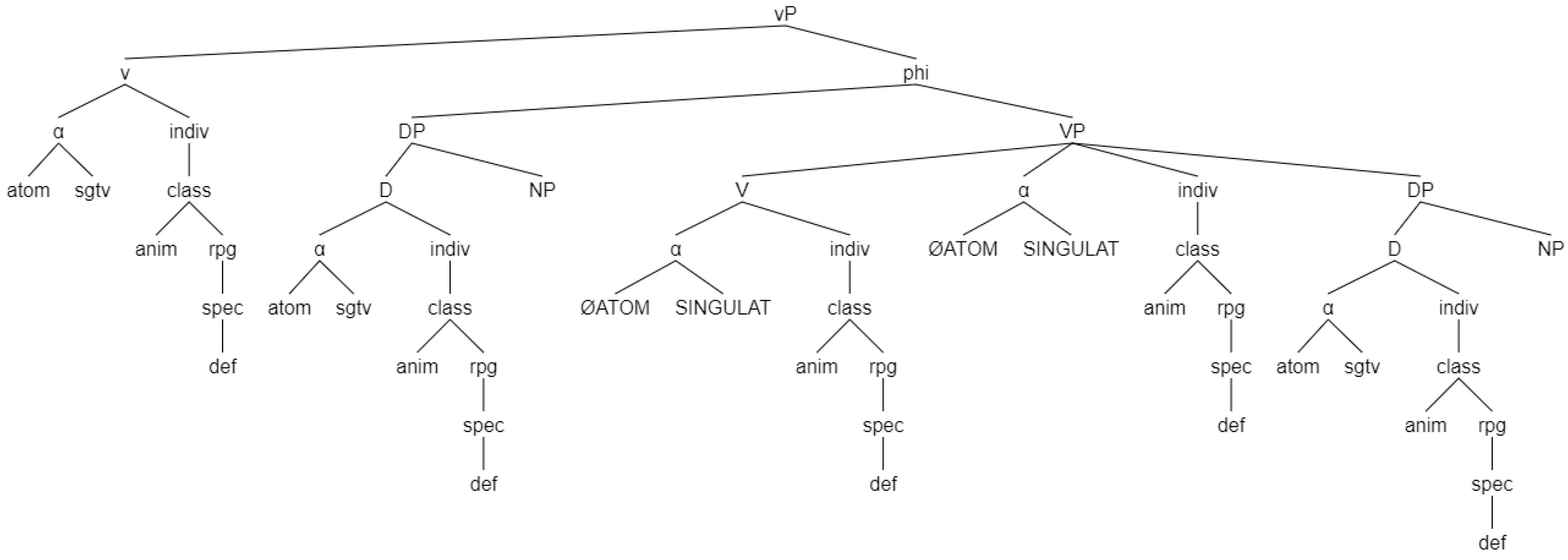

Figure 10:

There is in

Figure 10, an SO product of the merge of the verbal root, which is a head, and the object DP. Thus, the head should label; however, Chomsky, following

Marantz (

1997),

Borer (

2005,

2013), and

Embick and Marantz (

2008), assumes that roots are too weak to label, and that, therefore, a process must be initiated for V to label. The first is that the object undergoes internal merge (IM) to the specifier position of V. The object at this position is not contained in the mentioned SO; that is, the SO does not contain all the copies of the object, therefore, the object cannot label. Now, the only candidate to label is V; however, V is too weak to label. v* enters the derivation. The features of v* are inherited by V (

Chomsky 2008).

22 Then, Agree happens between v* and the moved object. The features of v* are valued, and the object receives a case. The inherited features by V are also valued.

The inherited phi features of v* allow the (now strengthened) root to label as VP. The other unlabeled node is labeled with the prominent phi feature that is shared between the VP label and the DP label of the moved object. This new label is Phi in

Figure 10b.

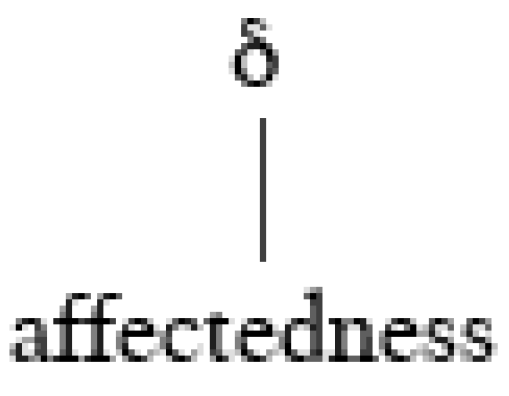

Although Chomsky is not explicit about the purpose of strengthening, I would like to propose that such strengthening amounts to licensing the lexical features of V with the ONs of v* that were inherited by V. The ON class-v should be inherited to license the lexical feature affectedness; the ON rpg-v should be inherited to license the lexical feature δ; and the ON individuation-v should be inherited to license the lexical feature α-V.

In the literature (

Rivero (

1977);

Enç (

1991);

Leonetti (

2004)), the notion of existence has often been associated with specificity. My version of this relationship is between the presupposition of existence (δ) and rpg (the ON that dominates the [spec] and [unspec] features).

23 The ON rpg-v must be inherited by V to license the lexical feature δ. Then, rpg-v is valued with rpg-D, and the ON rpg inherited by V, rpg-V, is also valued. On the other hand, on the basis of

Verkuyl (

1972,

1989,

1993),

Link (

1983,

1987),

Bach (

1986), and

Krifka (

1989,

1992),

Borer (

2005) argues that a telic event involves quantification. According to the author, telicity is achieved when an aspectual node enters into a relation with a quantified DP. This is the spirit of my proposal. The ON individuation-v must be inherited by V to license the lexical feature α-V (the lexical aspect). Next, individuation-v is valued with individuation-D, and the individuation that V inherited, individuation-V, also ends up valued.

It should be the case that when the ONs individuation-v, class-v, and rpg-v are inherited, the ON α-v should also be inherited; in other words, v* should inherit all of its ONs.

In

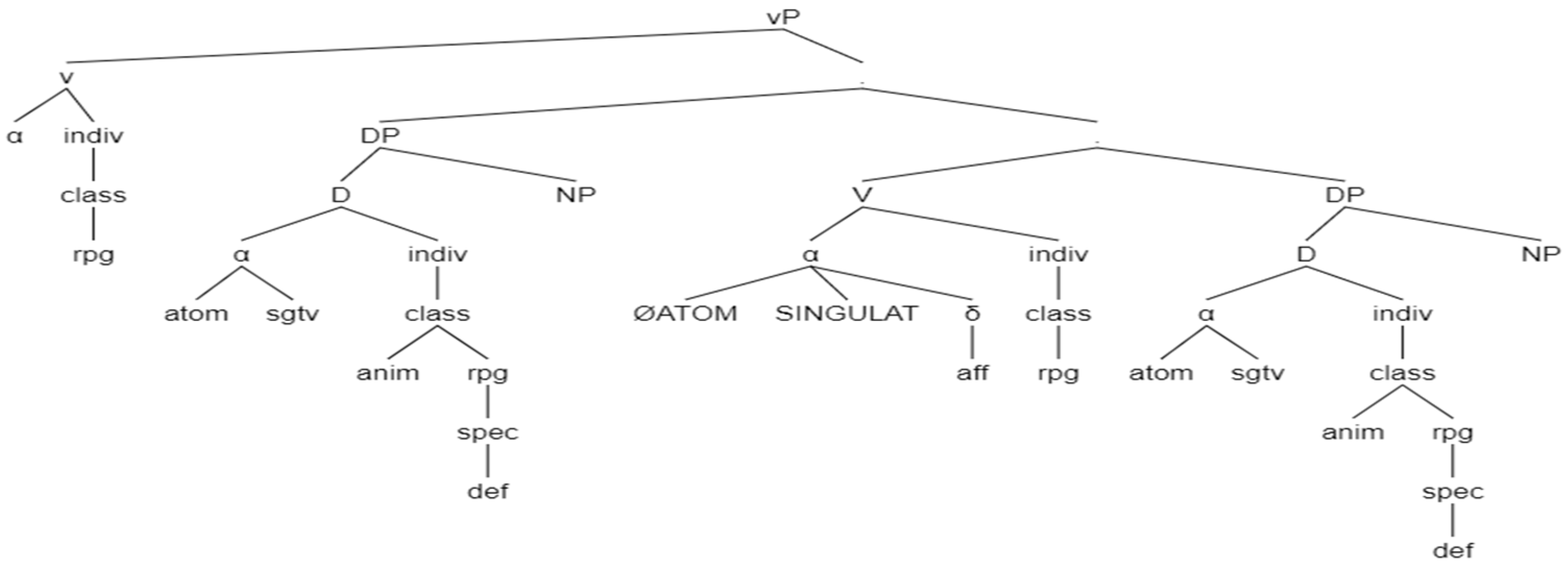

Figure 11, the same ONs of D must be in v*. These ONs of v* are inherited by V.

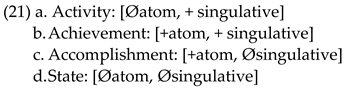

We can say that a root with its lexical features licensed can label (because it has already been strengthened). At what point does this licensing happen? Chomsky argues that inheritance should happen before Agree. In our proposal, this amounts to saying that unvalued ONs will be inherited by V. As a consequence of Agree, the ONs of v* are valued, and so are the ONs that are inherited by V. When are the lexical features of V (δ and affectedness) inserted into the derivation? Note that V inherits α from v*, as stated; the features δ and affectedness are not inherited, they are inserted from the lexicon. There would be a way to know when these lexical features are inserted. The ON α-v does not dominate the same features that the ON α-V dominates. The [atom] and [singulative] features that α-v dominates were valued from the α-D of the object; the [ATOM] and [SINGULATIVE] features that α-V dominates are not valued from D.

24 For example, if the verb is intransitive, v should not have an α-v (nor the other ONs); however, that sentence does have a lexical aspect, that is, V will have an α-V that dominates the features, [ATOM] and [SINGULATIVE], features that must come from the lexicon (i.e., they are not a result of the valuation with D). If α-V has its own features (not inherited from v*), it must be the case that the lexical features of V enter the derivation before Agree occurs. If these lexical features entered after Agree, α-V would dominate the same features of atomicity and singulativity that α-v dominates, because the same valued features of v are the features that V will inherit. However, α-V does not dominate the same features as α-v, and so the features that α-V dominates must enter the derivation before Agree. Specifically, the features [ATOM] and [SINGULATIVE] must enter the derivation after inheritance and before Agree. It seems reasonable to assume that, along with these features, δ and affectedness are also inserted. Thus, when v* passes its ONs to V, V does not yet have [ATOM], [SINGULATIVE], δ, or affectedness. These features enter the derivation after v* passes its ONs to V (the ONs α, individuation, class, and rpg).

25Is it possible that lexical features could be present in V before inheritance, that is, that V enters the derivation with its lexical features? This does not seem to be the case because, in order to insert affectedness and δ, it is necessary to have α-V, because α-V dominates these features (see

Figure 9). α-V is inherited from v, so affectedness and δ (features that are dominated by α-V) could not be present before inheritance.

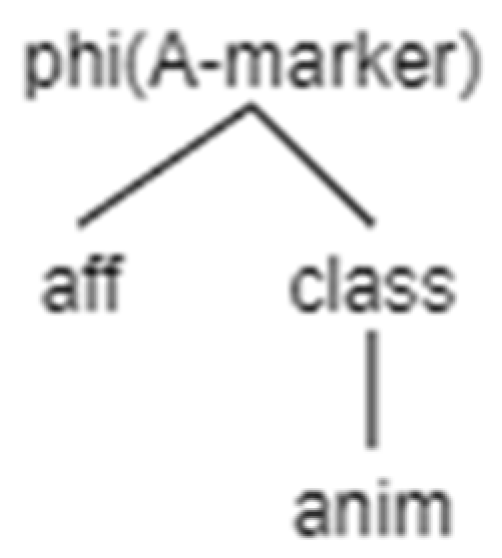

It has been said that, in the case of Spanish, class-v must be inherited by V in order to license affectedness; the ON individuation-v must be inherited to license α-V (the lexical aspect); and the ON rpg-v must be inherited to license δ (the presupposition of existence). With this strengthening, V should be labeled as VP. What features does the VP label have? There are at least two options: (i) The VP label must contain a copy of the lexical features of V with its licensing ONs and dominated features; (ii) The VP label must contain only the prominent ON with its dominated feature and the licensed lexical feature. I will opt for option (i). According to option (i), we can define Phi (the label that dominates the VP) as a subset of the features of the VP. Phi should contain only the prominent feature with its dominated feature and the licensed lexical feature.

26The steps seen to label (and, therefore, to have DOM) are the following: (a) IM of the object to the specifier position of V; (b) insertion of v* with its ONs; (c) V inherits those ONs from v*; (d) insertion of lexical features in V ([ATOM], [SINGULATIVE], δ, affectedness); (e) Agree between v and the moved object, and case assignment to the object; (f) licensing of the lexical features; (g) creation of the VP label; (h) sharing of the prominent feature between the VP and the moved object; and (i) creation of the Phi label, where the DOM mark will be generated.

In the hypothesis that I advocate, DOM is the materialization of Phi label features: the prominent ON with its dominated feature, and the licensed lexical feature. For Spanish, this prominent feature would be the ON class. If Phi has affectedness and class dominates [anim], there will be DOM. On the other hand, if class dominates the default [inanim], there will be no DOM, but class will always be the prominent feature that allows Phi to be labeled.

27In the proposed analysis, the VP label and the Phi label contain lexical features that are licensed with morphosyntactic features (ONs). This fits with the hypothesis that labeling is motivated by interpretive principles (

Chomsky 2013,

2015;

Rizzi 2016). In the following section, let us observe the application of the ideas that have been presented so far.

6. Explaining the DOM in Spanish (Geometries)

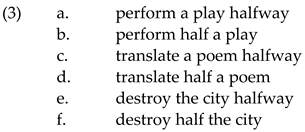

In this section, the geometries of the analyzed heads that have been seen so far will be presented. I start with the sentences of (1), which are repeated here:

![Languages 07 00114 i021]()

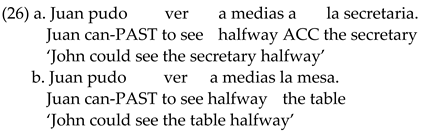

As is shown in (26), the sentences of (25) are compatible with an adverb that indicates affectedness:

![Languages 07 00114 i022]()

If the verb has affectedness, and the object is animate, that object will be marked with A. In (25b), there is affectedness, but the object is inanimate, therefore, it is not marked.

Before moving on to the geometries, I repeat here the steps to generate the DOM mark:

![Languages 07 00114 i023]()

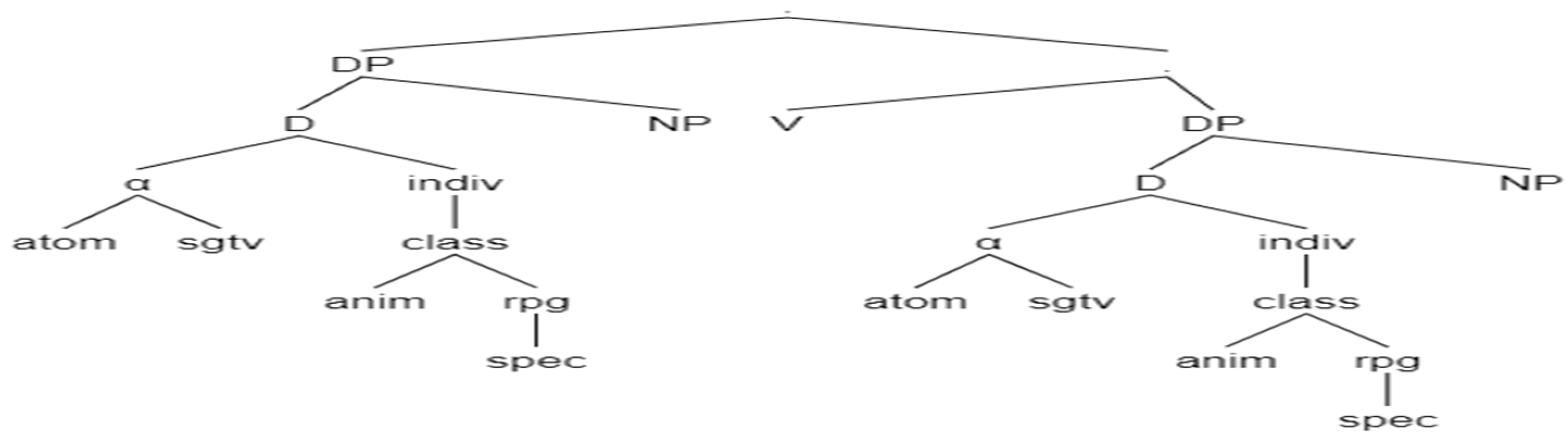

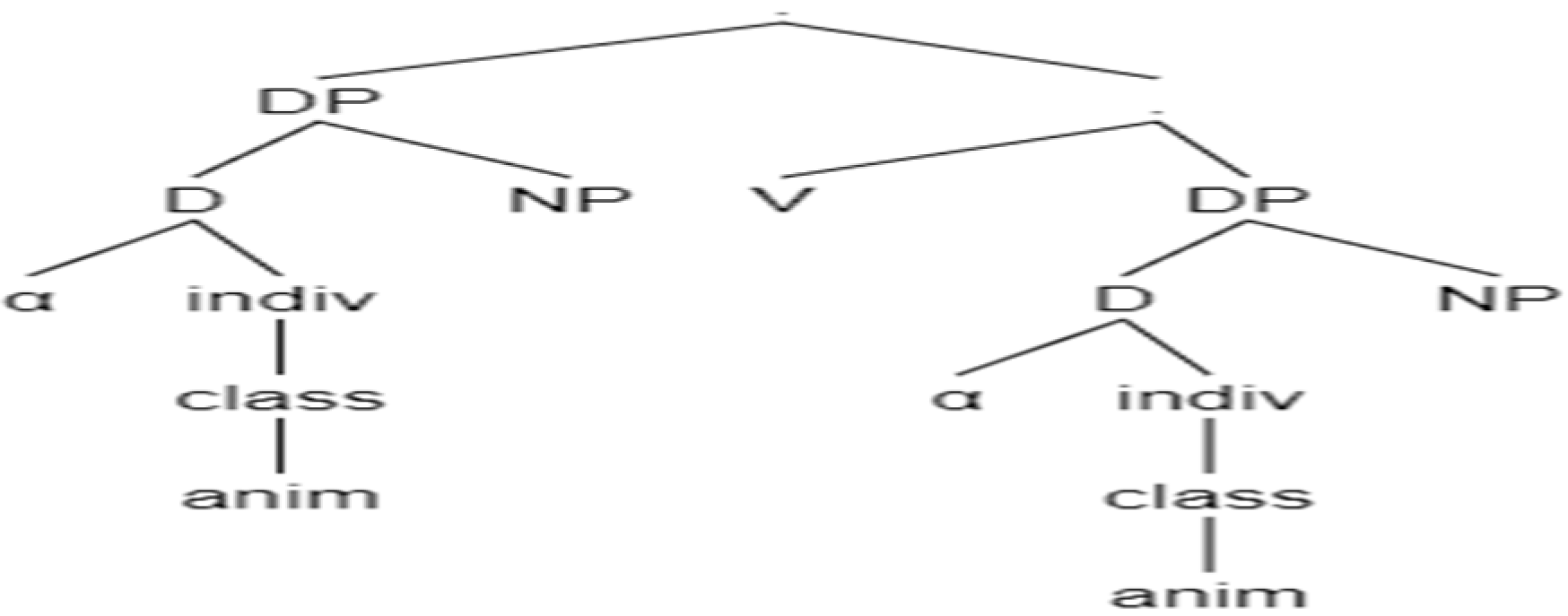

In the geometries that follow, I will assume the DP structure in

Figure 12:

The NP content will not be developed. In the operations that generate the Spanish DOM, the features of the NP do not seem to participate. To cite an example, the Agree operation is between v* (the probe) and D (the goal).

The geometries of the heads of sentence (25a),

Juan vio *(a) la secretaria (‘John saw the secretary’), are as follows:

![Languages 07 00114 i024]()

As discussed, I have assumed that the label has the same features as its head, and that, therefore, the DP will dominate the same features as D, as is shown in (a) below. However, in order to obtain a better understanding of the geometries in what follows, the set of features that the DP must dominate will not be considered, as shown (b). I will preserve the features that D dominates because I assume that v* must probe the head D, and not the label DP. Thus, in the following, I will use the geometry (b) of

Figure 13 in the representations.

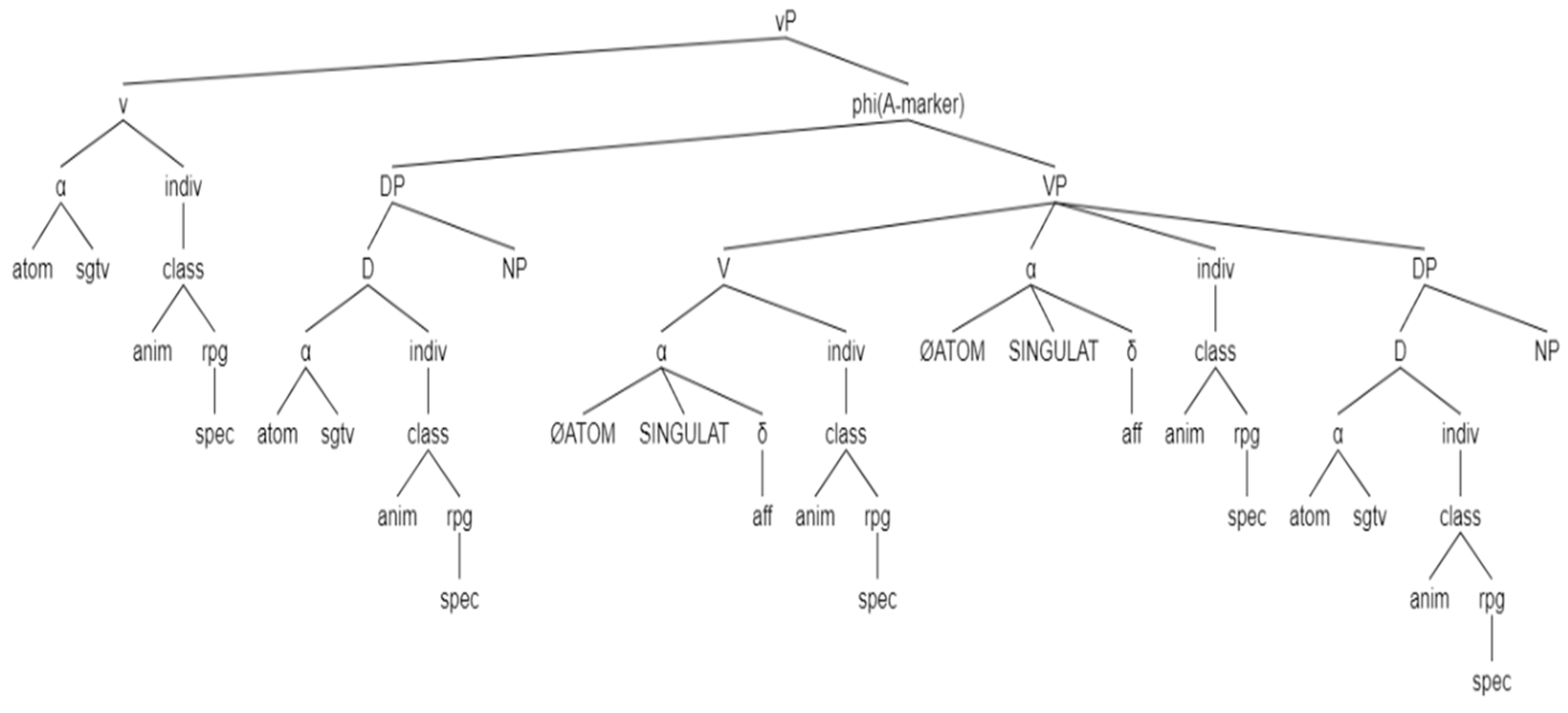

STEP 3: Insertion of v*; and STEP 4: V inherits those ONs from v*. Observe

Figure 14.

STEP 5: Insertion of lexical features. Observe

Figure 15.

Specifically, in this geometry, the lexical features [ØATOM], [SINGULATIVE], δ, and affectedness are inserted into V.

The probe of v* matches the goal D (of the moved DP), and copies the features of that D into v*. The features are also copied into V. The DP receives case.

STEP 7: Labels.

The labels VP and Phi (where the A-marker is generated) appear. The VP label must dominate the same feature set as its head V. I will keep the feature set that the VP label dominates because the prominent ON of that set must be shared with the prominent ON of D. On the other hand, the Phi label must dominate the prominent ON and the lexical feature that is licensed by that ON, as assumed. See cases a and b in

Figure 17 below. For design reasons, the feature set that the Phi label dominates has been set aside (b).

Let us review the steps to mark the object. V merges with the DP object. It is not possible to label and, therefore, the object must be moved to specifier of V. v* is merged. If v* must have the same ONs that D dominates, as assumed, v* must have α-v, individuation-v, class-v, and rpg-v. All of these ONs must be inherited by V. Before Agree, the lexical features [ATOM], [SINGULATIVE], δ, and affectedness should be inserted into V. There is Agree between v* and the moved object, which will receive case, and the ONs of v* will be valued; the inherited ONs by V are also valued. Inserted lexical features are licensed with inherited and valued ONs; V was strengthened, so it can be labeled as VP. VP shares with D its prominent ON and the dominated feature. Specifically, in (25a) Juan vio *(a) la secretaria, class and [anim] must be shared. The result of this sharing is the Phi label. It is possible to have DOM because in Phi there is class dominating [anim] and affectedness.

The geometry of the heads of (25b), Juan vio (*a) la mesa, is similar to the geometry of (25a), Juan vio *(a) la secretaria; the only difference is that class dominates [inanim]. The feature [inanim] may not be in the geometry because it is the default. It is not possible to mark the object with A in (25b) because, for that to happen in Spanish, it is necessary that class dominates the feature [anim].

Consider the cases with an indefinite object:

![Languages 07 00114 i025]()

The object of the sentence (29a) is specific, as is shown by the compatibility of the phrase ‘a María’. The compatibility of the adjunct in parentheses in (30a) shows that the object in (29a) is affected. As stated, in Spanish, an affected and animate object must be marked with A. Sentence (29b) shows that the marked object is also compatible with a complement that expresses the absence of the feature [spec]. The proposal is that this object is [unspec(ific)].

One evidence that the v* of (29b) has an rpg dominating [unspec] would be in the impossibility of having clitics. If we assume that clitics are the materialization of phi features in v* (

Suñer (

1988);

Sánchez (

2006); among others), a case in which rpg-v* is valued would be when it is possible to have accusative clitics (

lo(s), la(s)). These clitics should have [spec(ificity)] and [def(initeness)] features, as well as the corresponding definite and specific determiners (

el/los, la(s)) to which they are related.

28 It is expected that, in cases such as (29b), no clitic is possible (because rpg-v* dominates an [unspec] feature), and, in cases such as (29a), it should be possible. The prediction is borne out.

![Languages 07 00114 i026]()

On the other hand, as (30b) shows, the object of (29b) is affected.

Let us look at labeling. The object that merged with V moves to the V specifier position (as part of the process of labeling V). v* is merged with the same ONs that D dominates. Thus, v* from (29a) and v* from (29b) should have the following ONs: α-v, individuation-v, class-v, and rpg-v. These ONs are inherited by V. Before Agree, the lexical features [ATOM], [SINGULATIVE], δ, and affectedness should be inserted into V. There is Agree between v* and the object that was moved to Spec, V. The object receives case, v* values its ONs, and the ONs that are inherited by V are also valued. V (strengthened, i.e., with its lexical features licensed) is labeled as VP. This VP label contains the ONs, their dominated features, and the lexical features of V. The VP shares its prominent ON and dominated features (class and [anim]) with D. The result of this sharing is the Phi label. DOM is necessary in (29a) and (29b) because there is class, [anim], and affectedness in Phi. The difference between the heads of these sentences is that rpg dominates [spec] in (29a); in (29b), rpg dominates [unspec].

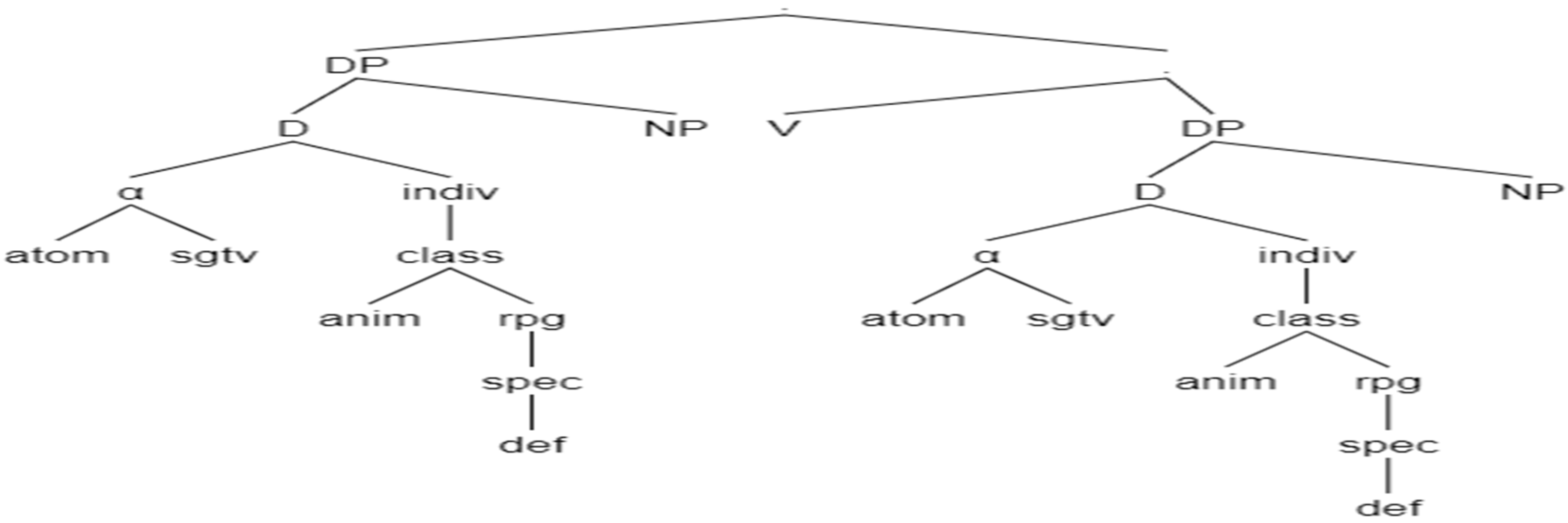

In the following, only two geometries will be presented. First, the geometry after IM of the object and before the operations (insertion of v*, inheritance, insertion of lexical features, Agree, and labeling). Second, the final geometry with the Phi label formed, the label where the A-marker is generated. The geometries of the heads of (29a) and (29b) are as follows:

- (32)

Geometry of the heads of (29a),

Juan vio a una actriz, a María [specific] (‘John saw an actress, Mary’). See

Figure 18,

Figure 19 and

Figure 20.

The DP A María has not been represented in the geometry.

As mentioned, this Phi label in

Figure 20 is the same as the Phi label in

Figure 19. For design reasons it was necessary to set it aside.

In the geometry of

Figure 18, D dominates an ON individuation, which dominates a feature [minimal], that does not appear because it is default. The ON α-D dominates the features [atom] and [singulative], because it is an I(ndividual) object. The ON class-D dominates the feature [anim], and the ON rpg-D dominates the feature [spec]; there is no [def] because the object is indefinite. All of these features are copied, via Agree, into v*. These features are also copied into V, except for the features that α-V dominates ([ØATOM] [SINGULATIVE]), which are the features that describe an activity; these features must be extracted directly from the lexicon. The VP label must dominate the same features as V, as was assumed. The Phi label dominates the prominent ON of Spanish (class) and the lexical feature that is licensed with that ON (affectedness), as is shown in

Figure 20. There is an A-marker because class dominates [anim].

- (33)

Geometry of the heads of (29b),

Juan vio a una actriz; pero no sé a cuál [unspecific]; (‘John saw an actress; but I don’t know which one’). Observe

Figure 21 and

Figure 22.

Note that the A-marker of the object is possible, even with an object [unspec] (29b, 30b). This suggests that the specificity does not participate (directly) in the DOM of Spanish.

30 The lexical feature δ is necessary in order to have affectedness because the former dominates the latter, according to the assumed geometry. The ON rpg is required to license δ; it is not necessary that the object be [spec]. Thus, an [unspec] object can also license δ because [unspec] is also dominated by the ON rpg. With δ licensed, it is possible to have affectedness and to mark the animate object with A.

Let us now observe sentence (29c),

(*De aquel grupo) Juan vio una actriz. The object cannot be included in the set that are in parentheses, which indicates that this object has no specificity. Is it necessary to postulate an rpg-D with [unspec], as in (29b)? According to

Bleam (

2005), objects without a determiner and indefinite, animate, unmarked objects (as in (29c)) are <e,t> properties that can appear in an argument position. These elements, without D, are incorporated (semantically) into the verb, and thus, they cannot be marked with A. According to the author, the properties do not contain an existential quantifier as part of the inherent denotation of the nominal. Taking Bleam’s ideas as a basis, it seems reasonable to think that such properties do not have an ON rpg-D. In the D of the object of (29c), which is a property, it would not be possible to have an ON rpg dominating [spec] or [unspec]; such an object should not have rpg-D. On the other hand, it seems to be the case that a property does not need to be related to the lexical feature of presupposition of existence (δ). Thus, it must not have rpg-D in the object of (29c), and it must not have δ in the verb, because δ could not be licensed without rpg.

If v* must have the same ONs that D dominates, the v* of (29c) must have α-v, individuation-v, and class-v that dominate its valued features from D. That v* must not have rpg-v, because there is no rpg-D. Those ONs must be inherited by V. On the other hand, as is shown in sentence (30c),

Juan vio (*a medias) una actriz, there is no affectedness in (29c). Thus, the V of (29c) has no δ or affectedness; it would only have α-V, the lexical aspect. We are facing an unprecedented situation: having an ON in V that does not license any lexical feature of V; the ON class-V does not license affectedness (because there is no affectedness in V). I assume that this ON class-V must be maintained (even without licensing affectedness) in order to label the VP. The ON class of the VP and its feature [anim] are shared with class of the DP and its feature [anim]. The label Phi must have only class dominating [anim]. There is no DOM, because affectedness is also necessary to mark the object.

31- (34)

Geometry of the heads of (29c),

(*De aquel grupo), Juan vio una actriz [nonspecific]; (‘(Out of that group), John saw an actress’). See

Figure 23,

Figure 24 and

Figure 25.

The question arises with regard to the features that α-D would dominate in (29c) (and α-v as well, because α-v is valued with α-D). A property would have an α-D without dominating any feature [atom] or [singulative], because those features would apply only to entities (individual, kind, mass, group). The presence of α-D (without dominated features), and the absence of rpg-D would indicate that we are facing a property.

If so, α-v must not dominate any feature either. On the other hand, α-V must dominate the features [ØATOM], [SINGULATIVE], which describe the activity event of (29c). As said, the features that are dominated by α-V are not inherited from α-v, but they are extracted from the lexicon. It might be thought that α-v is not necessary because it does not dominate any feature; however, α-v is necessary because it must be inherited by V. α-V is the ON that is responsible for the lexical aspect (an activity in (29c)).

We can say that the difference between the Ds of the objects in (29b) and (29c) is that, in the former, there is an rpg-D that dominates [unspec], and, in the latter, there is no rpg-D. In (29b), there is an α-D dominating the features that describe a noun I, [atom], and [singulative]. In (29c) there is an α-D that does not dominate any feature, this is a property.

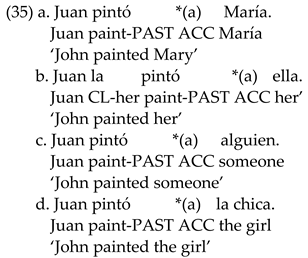

Consider the following cases:

![Languages 07 00114 i027]()

The data in (35) show that the A-marker is required with objects such as proper nouns, pronouns, indefinites such as

alguien (‘anyone’), and specific definite DPs. Why should this be so? All of the objects in (35) have α-D (dominating [atom] and [singulative]), class-D (dominating [anim]), and rpg-D (dominating [spec]); in (35c), the object could be [unspec]). As assumed, v* should have the same ONs that D dominates. These ONs of v* should be inherited by V. I also proposed that the lexical features of V be inserted after inheritance (α-V dominates the lexical features δ and affectedness, therefore, these lexical features cannot be in V before V inherits α from v*). In this analysis, it seems reasonable to assume that the insertion of lexical features depends on the presence of ONs that can license them. This implies that it will not be possible to insert a lexical feature if it does not have a licenser that is present. Thus, if there are class-V and rpg-V in V (inherited from v*), it will be possible to insert δ and affectedness because they are going to be licensed. Looking at (35), we notice that D has an ON class dominating [anim]. v* must also have these features, which it passes to V; with class and [anim] in V, it is possible to insert affectedness which, when licensed, forces the presence of the mark in (35). The assumption that the insertion of lexical features depends on the presence of ONs that can license them must apply also for the other lexical features, δ and α-V, which can be inserted if there is rpg-V and individuation-V, respectively. On the other hand, in order to be able to insert lexical features into V, it is necessary that V be compatible with these features. A state verb (e.g.,

tener (‘to have’, possessive)) is not marked to affect its object, so even if class dominates [anim] in V, it will not be possible to have affectedness. Licensing ONs do not force the presence of the lexical features to be licensed.

32Before moving on to the case of intensional verbs, I will return to the case of the verb,

tener (‘to have’). I repeat sentence (20) as (36); the examples of

Torrego (

1999) are added in (37):

Sentence (36) shows that there could be presupposition of existence without affectedness. The incompatibility of the adverb between the parentheses shows that there can be no affectedness there. Without affectedness, it is not possible to have A-marker, according to the hypothesis that I defend. However, it is possible to mark the object of

tener. According to

Torrego (

1999), it is possible to mark the object of the verb

tener with A when the subject has responsibility or causality. Thus, in the following contrast of the author, only (38a) is possible:

It is not possible that the subject has sent many students to study a problem without being responsible for it. I will assume Torrego’s analysis. If the A-marker always expresses affectedness, it is expected that in (37b), with an A-marker, this lexical feature is present. I propose the cases in (39) with the adverb

parcialmente, that show the presence of affectedness. I have added the adjunct

bajo su responsabilidad (‘under his responsibility’), in order to emphasize the responsibility in the subject that is observed by Torrego. Sentence (39a) can be stated within a context in which Mary shares responsibility with someone else.

![Languages 07 00114 i030]()

In version (39a), the object with an A-marker is compatible with an adverb that expresses affectedness, parcialmente (‘partially’). Version (b), without marking the object, is not possible. If there is affectedness in the verb and the object is animate, that object must be marked with A.

Assuming Torrego’s ideas, we can say that the verb tener (‘to have’) can mark its object with A when it has the meaning of causation or responsibility. In this case, the verb must affect its object.

I continue with the verb

buscar (‘to look for’). Unlike nonintensional verbs, such as

ver (‘to see’) and

pintar (‘to paint’), intensional verbs allow a definite animate object without A. Observe the following sentences of Fernández

Ramírez (

1986) (apud

Brugè and Brugger (

1996)):

![Languages 07 00114 i031]()

According to Brugè and Brugger, the definite animate object without A is always a kind, and the object with A is always an I(individual). Assuming that the complement ‘

a María’ denotes an I, sentence (41a) shows that the object without A cannot be an I; sentence (41b) shows that the object with A is an I:

![Languages 07 00114 i032]()

The version without A (40a) is incompatible with adjuncts that denote affectedness (

un poco más):

![Languages 07 00114 i033]()

The contrast of (42) shows that the verb buscar can optionally have affectedness. If there is affectedness in V, the animate object will be marked with A (42b).

I have assumed that the lexical feature δ dominates the lexical feature affectedness. The question arises as to whether the lack of affectedness in (42a) is caused by the lack of δ. A distinctive feature of an intensional verb is that it can suspend the presupposition of existence of its object. The subject may look for something that he does not presume exists (for example, unicorns). If intensional verbs have the option of not having δ, this absence must lead to a lack of affectedness. Sentences such as (40a) must not have δ, and, therefore, there should be no affectedness either (42a). Constructions such as (40b) must presuppose the existence of the object and have affectedness (42b).

Possible evidence of the presence or absence of δ in the verb

buscar (‘to look for’), could be as follows. Let us imagine the following situation: Maria considers that there is no decent president; however, if she finds one who is decent, she will begin to believe in the decency of presidents. Crucially, she does not presuppose the existence of a decent president (she begins the search to prove her point that there is no decent president). Which of the two sentences of (43) expresses this context? It could just be (43a). In (43b), the A-marker expresses the presence of affectedness, but it is necessary to have δ in order to have affectedness (because δ dominates affectedness); that is, there must be presupposition of existence. However, crucially, Maria does not presuppose the existence of this president. The object marked in (43b) generates a contradiction with the described context. In (43a), the absence of the mark indicates that there is no affectedness, because there is no δ:

![Languages 07 00114 i034]()

The data indicate that the marked object of an intensional verb such as

buscar (‘to look for’) must presuppose its existence; the unmarked object cannot.

33 The analysis shows that the lack of affectedness in the verb

buscar in (42a) coincides with the lack of δ. This is explained if we assume that δ dominates affectedness. If affectedness dominated δ, it would be possible to have affectedness without δ, but the data show that sentences with marked objects (affected objects) can only have the reading that presupposes existence (the reading with δ).

It is interesting to note that, in constructions such as (40b),

Antoñito buscaba a la mujer rica, it is not possible to have δ without affectedness. This might suggest that it is affectedness that dominates δ; but this would not be the case. The presence of affectedness in (40b) could be explained by the hypothesis that states that, if there is a licenser of a lexical feature in V, that feature will be inserted (if the verb is marked to have that feature). The D of the object (40b) has class with [anim]. These features will also appear in v*, and will be inherited by V. It is possible to insert affectedness with class present in V. If class dominates [anim], there will be DOM.

34The geometry of the heads of (40a), Antoñito buscaba la mujer rica (‘Antoñito was looking for the rich woman’) are shown in

Figure 26,

Figure 27 and

Figure 28.

In the Phi label of the

Figure 28, there is no affectedness and, therefore, there can be no DOM.

Note that v* passes rpg to V. This creates a context so that δ can be inserted; however, intensional verbs would have the option of not inserting δ, as discussed. Without δ, it is not possible to have affectedness. Without affectedness, it is not possible to mark the animate object with A.

The geometry of (40b),

Antoñito buscaba a la mujer rica (‘Antoñito was looking for the rich woman’) are shown in

Figure 29 and

Figure 30.

The Spanish data with DOM in intensional verbs show that it is perfectly possible to have an unmarked object animate and definite (40a), which is something improbable with nonintensional verbs, for example, (1a)

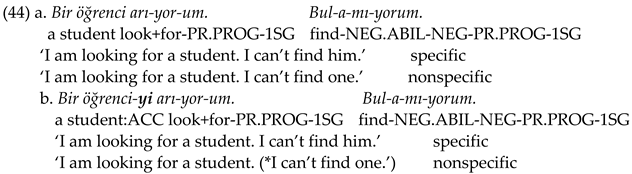

Juan vio *(a) la secretaria. This option is not unique to Spanish. Other languages display the same pattern. In Turkish, the prominent ON is rpg. If rpg dominates [spec], there is DOM. In Romanian, the prominent ON is composed: class and rpg. If class dominates [anim], and rpg dominates [spec], there is DOM. In Persian, the prominent ON can be rpg or individuation. If rpg dominates [spec], there will be DOM; if individuation dominates [group], there will also be DOM. In Kannada, it can be ON prominent individuation, class, and rpg. If individuation dominates [group], there is DOM; if class dominates [anim], there is DOM; if rpg dominates [spec], there will also be DOM.

36Sentence (44b) has a marked object, so the only possible reading is specific. This is the expected situation if we assume that the Turkish DOM responds to the [spec] feature. Interestingly, the unmarked version on the object in (44a) allows for two readings: the nonspecific reading (the expected), and the specific reading (the unexpected). The specific reading is unexpected if we assume that Turkish [spec] objects must be marked.

One possible explanation for the absence of the mark before an object [spec] (one of the readings of 44a) could be that it lacks δ in V, which is the lexical feature that should be licensed to have mark in Turkish. In Spanish, I propose that an intensional verb may not have δ (without δ, it is not possible to have affectedness) to explain the absence of the mark on an animate object of an intensional verb (40a); the hypothesis seems to work also in the case of Turkish. Without δ, it is not possible to mark the object in Turkish; affectedness does not participate in the Turkish DOM. On the other hand, the possibility of having specific reading in an unmarked object (one of the readings of (44a)) must be because the object must have an rpg-D dominating [spec], although it is also possible to not have rpg-D (which would explain the nonspecific reading of (44a)). There must be no δ in both readings of (44a), so the mark is not possible.

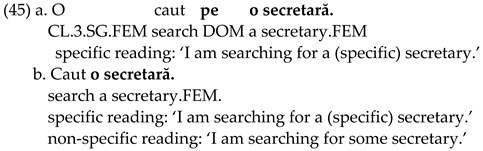

The object of the sentences of (45) is animate and may be specific, as in (45a) and one of the readings of (45b); or it may be nonspecific, as in the other reading of (45b). If the Romanian’s mark expresses [spec] and [anim], the object of (45a) is expected to be marked. Interestingly, an object [spec] and [anim] may not be marked either, as in one of the readings of (45b). Similar to Turkish, the explanation may be that, in (45b), there is never δ in V, but there is an rpg-D dominating [spec] (in the specific reading of (45b)), or there may be no rpg-D (in the nonspecific reading of (45b)). The analysis is plausible if we assume that intensional verbs may not have δ.

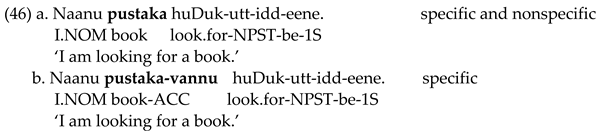

37Note the Kannada data in an intensional context (

Lidz 2006). The DOM mark is

vannu.

![Languages 07 00114 i037]()

In the unmarked version (46a), a nonspecific reading is possible (as expected, if the mark in Kannada can express [spec]), but a specific reading is also possible. In the specific reading of (46a), rpg-D must dominate [spec], but V must not have δ. If v* has the same ONs as object D has, v* must also have rpg, which must be inherited by V; however, there is no DOM in (46a) because V would not have δ (As discussed, an intensional verb could optionally have the feature δ (the presupposition of existence)). As assumed, the Phi label must also have the licensed lexical feature in order to have DOM. On the other hand, in the nonspecific reading of (46a), rpg-D and rpg-v must not be present; δ must also be absent. In (46a), the intensional verb would never have δ. In sentence (46b), with a mark, it should have rpg-D, rpg-v, rpg-V, and δ. As expected, the only possible reading is the specific one.

Note the Persian data in an intensional context (

Clair 2016):

![Languages 07 00114 i038]()

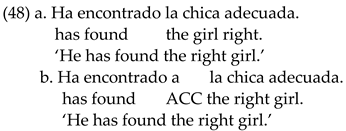

In Persian, the DOM mark (-ro) can express [spec]. In sentence (47), the verb is intensional, and the DOM mark becomes optional. As in the case of Spanish, Turkish, Romanian, and Kannada, a possible explanation for the alternation of the DOM mark in (47) might be that an intensional verb may not have the feature δ, that denotes the presupposition of existence.

The data from the languages show that, in an intensional context, the DOM mark becomes optional. One explanation for this unexpected optionality is that the lexical feature of V that participates in the DOM in these languages may not be present; in the observed cases (44–47), this feature is δ. An intensional verb may not have δ, as discussed. On the other hand, we observe that, even without δ, it is possible to have a specific reading. This reading should be possible because of the presence of the feature [spec] in D; however, this feature would not license δ from V because δ would be absent from V.

We have seen that nonintensional verbs, such as

ver (‘to see’),

saludar (‘to greet’), and

pintar (‘to paint’), do not allow a direct definite, animate object without A (e.g., (1a)

Juan vio *(a) la secretaria); intensional verbs do allow an unmarked object (e.g., (40a

Antoñito buscaba la mujer rica). Verbs such as

ver do not have the option of not having δ; therefore, if V has class and rpg, there will be δ and affectedness (in accordance with the proposed hypothesis that lexical features will be inserted into V if there are ONs to license them). Nonintensional verbs, such as

ver, would have the option of suspending δ (the presupposition of existence) at the cost of changing the semantic type of the object. In cases without δ, such as (29c) (

(*De aquel grupo) Juan vio una actriz)), the object is a property (without rpg-D). On the other hand, the absence of the lexical feature δ in intensional verbs such as

buscar seems to have different effects. In (40a), the object is a kind, according to Brugè and Brugger. Note, however, that it is not necessary for the object to be a kind in order to suspend the lexical feature δ. Consider the following case:

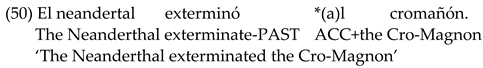

![Languages 07 00114 i039]()

The object of the verb encontrar (‘to find’) is not a kind but an I(individual). The object of the verb encontrar, which is a nonintensional verb, can optionally have A, even if such an object is definite (hence, [spec]) and animate. Thus, it seems to be the case that the verb encontrar has the existence presupposition optionally. It is possible to find something that was not assumed to exist (a unicorn, for example). The version without A (48a) would express the lack of presupposition of existence and affectedness; in the version with A (48b), there would be such a presupposition and affectedness.

The examples in (49) show that, in the version without A, there is no affectedness. Sentence (49b) could be spoken in a context in which the boy partially fulfills the requirements for the job:

![Languages 07 00114 i040]()

According to

Brugè and Brugger (

1996), the A-unmarked object of an intensional verb is a kind. However, as expected, it is possible to have marked kind objects in nonintensional verbs with δ.

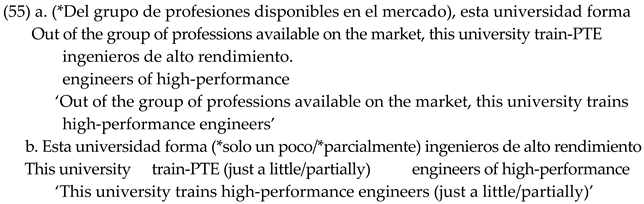

![Languages 07 00114 i041]()

The verb exterminar (‘to exterminate’) only takes kind complements. This verb is not intensional, and it seems to presuppose the existence of the object, so there must be δ in (50). δ dominates the affectedness feature; with affectedness and the features [class] and [anim], the object must be marked with an A.

I continue the analysis with objects without a pronounced D. Note the following data:

As noticed by

Brugè and Brugger (

1996), objects without a pronounced determinant do not allow the A-marker (51). According to

Bleam (

2005),

Laca (

1990), and

McNally (

1995), ‘bare’ plural objects in Spanish are always properties. I will assume this hypothesis. As was seen, properties would not have rpg-D. The object without rpg-D cannot be [spec] (because rpg dominates [spec]); (52a) shows that the object cannot be included in the set inside the parentheses, which suggests that it does not have the feature [spec].

![Languages 07 00114 i043]()

Properties would also not be associated with the lexical feature δ (see the analysis of (29c) ((*De aquel grupo) Juan vio una actriz). It would not be possible to have affectedness without δ because the first dominates the second. Sentence (52b) shows the incompatibility of affectedness adverbs.

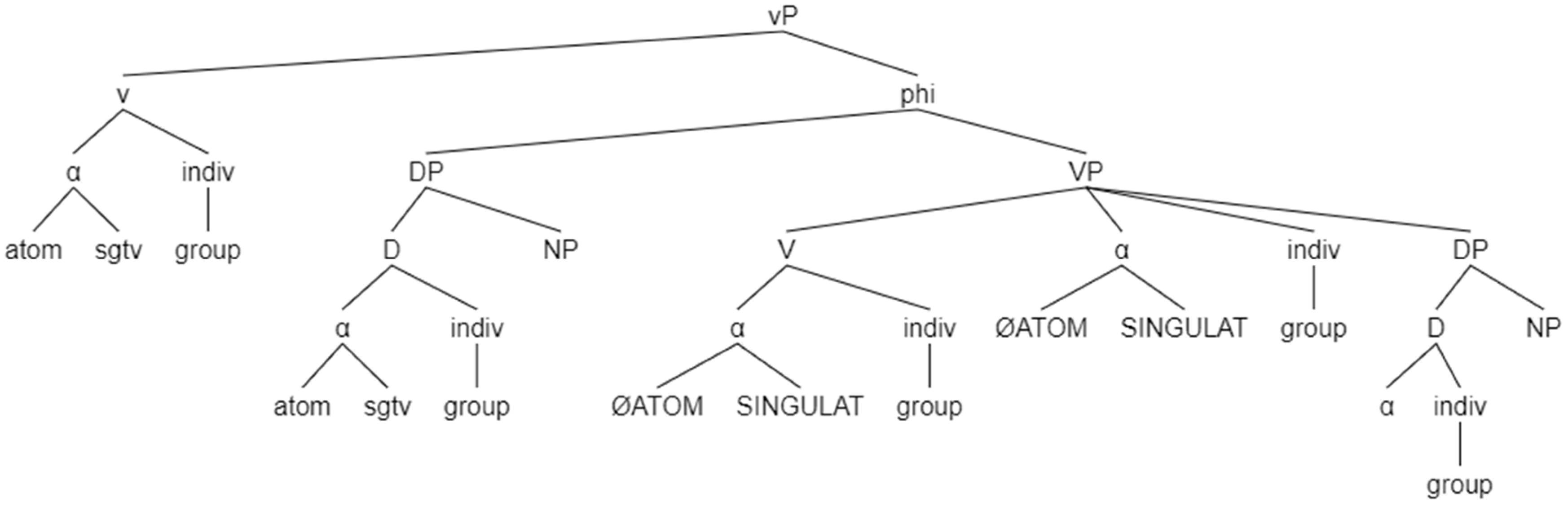

I am going to assume that the unpronounced D of (51) must have only individuation dominating [group]

38; there would be no class-D or rpg-D. V must contain only the lexical feature α-V (the lexical aspect), which must be licensed with the ON individuation that V inherited from v*. The geometry of the heads of (51) is shown in

Figure 31.

If the object of (51) is a property, it must have an α-D without dominating any feature; rpg-D must also be absent (see the analysis of sentence (29c) (*De aquel grupo) Juan vio una actriz). In (51), there is neither class nor affectedness (52b) and, therefore, it will not be possible to mark the object with A. In relation to the features of the Phi label, the only option seems to be that Phi must dominate the features individuation, [group], and the lexical feature α-V dominating [ØATOM] and [SINGULATIVE].

Objects with an unpronounced D allow A optionally if they are modified:

![Languages 07 00114 i044]()

Let us first look at the sentence with an A-marker (53a). As we have seen, it is possible to have δ if there is rpg-D, and it is possible to have affectedness if there is δ. Sentence (54a) shows the compatibility of a set that includes the object (which indicates that this object is [spec], and, consequently, that there is rpg-D), and (54b) shows the compatibility of adverbs of affectedness. If there is affectedness and the object is animate, it should be marked:

![Languages 07 00114 i045]()

The version without A (53b) does not allow a set (55a) or affectedness adverbs (55b):

![Languages 07 00114 i046]()

The reading of sentence (53b), with an object without a mark, is that there is only one type of engineer, with the characteristic that they are high performance. The ‘

alto rendimiento’ (‘high-performance’) complement does not form a subgroup and, therefore, there is no rpg-D, as is shown by the incompatibility of the set in (55a).

39 It is not possible to have rpg-v without rpg-D, and without rpg-v, it is not possible to have rpg-V; therefore, δ cannot be inserted (according to the hypothesis that lexical features will be inserted into V if it has ONs to license them). It is not possible to have affectedness (55b) without δ because the second dominates the first.

Consider the data with intensional verbs:

![Languages 07 00114 i047]()

The situation is similar to that observed with nonintensional verbs, such as formar (‘to form’) (i.e., objects without a pronounced D do not allow the A-marker unless they are modified). However, although similar, there would be a difference. As assumed, intensional verbs can suspend the existence presupposition of the object so that it is not necessary for the object to be a property in order for it not to be marked. It is sufficient with choosing the version without δ of the intensional verb to have no affectedness and, therefore, there will be no A-marker either. Thus, version (57b) would have two possible derivations: one with the object as a property; and another with the object as a nonproperty. In both versions, there is no δ in the verb. With nonintensional verbs, as in (53b) (Esta universidad forma ingenieros de alto rendimiento), the only option is for the object to be a property, which causes the lack of δ and affectedness, as assumed.

By way of a summary of

Section 6, I can say that the proposed DOM analysis appeals to an interaction between morphosyntactic features and lexical features. Specifically, the A-marker of Spanish direct objects appears when the Phi label (which is the result of the VP and DP prominent feature sharing) contains the lexical feature affectedness, and the ON class dominating the feature [anim]. In addition to labeling theory (

Chomsky 2013,

2015), I used the feature geometry of

Harley and Ritter (

2002) to implement the interaction between the features. To that geometry were added the ONs rpg and α. With that theoretical background, the DOM on definite objects could be explained. Indefinite objects require an extra assumption, which is that indefinite DPs can be properties. A property would not have rpg-D, which is the δ licensor. As proposed, δ would be the feature that expresses the presupposition of existence, and which dominates affectedness. Thus, without rpg-D it will not be possible to license δ. Without δ, it is not possible to have affectedness. This would explain why animate, indefinite objects can perfectly well not be A-marked with all kinds of verbs. In this case, they will be properties. On the other hand, animate, definite DPs can be unmarked when they are objects of intensional verbs. The hypothesis that I defend for these cases is that an intensional verb can optionally have δ in V, which is a lexical idiosyncrasy. Without δ, it is not possible to have affectedness (because the former dominates the latter). Without affectedness in V or in Phi, it is not possible to mark the animate object. The dependence of affectedness on δ also became apparent in cases with objects with unpronounced Ds. If these objects are not modified, they cannot have rpg-D. Without rpg-D, it is not possible to have rpg-v or rpg-V. Without rpg-V, δ cannot be inserted. Without δ, it is not possible to have affectedness. Although the Spanish DOM depends (indirectly) on the presence of rpg and δ, it would not be correct to say that in Spanish DOM expresses specificity, because it is possible to have the A-marker with unspecific objects. Nor would it be correct to say that the A-marker expresses rpg (which would become the prominent ON instead of class), because, if that were the case, it should be possible to mark every inanimate object, which is something that is not allowed in Spanish. What the DOM of Spanish expresses is affectedness with class dominating [anim], as was shown in the analysis.