The Role of Linguistic Typology, Target Language Proficiency and Prototypes in Learning Aspectual Contrasts in Italian as Additional Language

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Learning Aspectual Morphology in Romance Languages

3. Tense and Aspect in Swedish and Romance

4. The Study

5. Materials and Methods

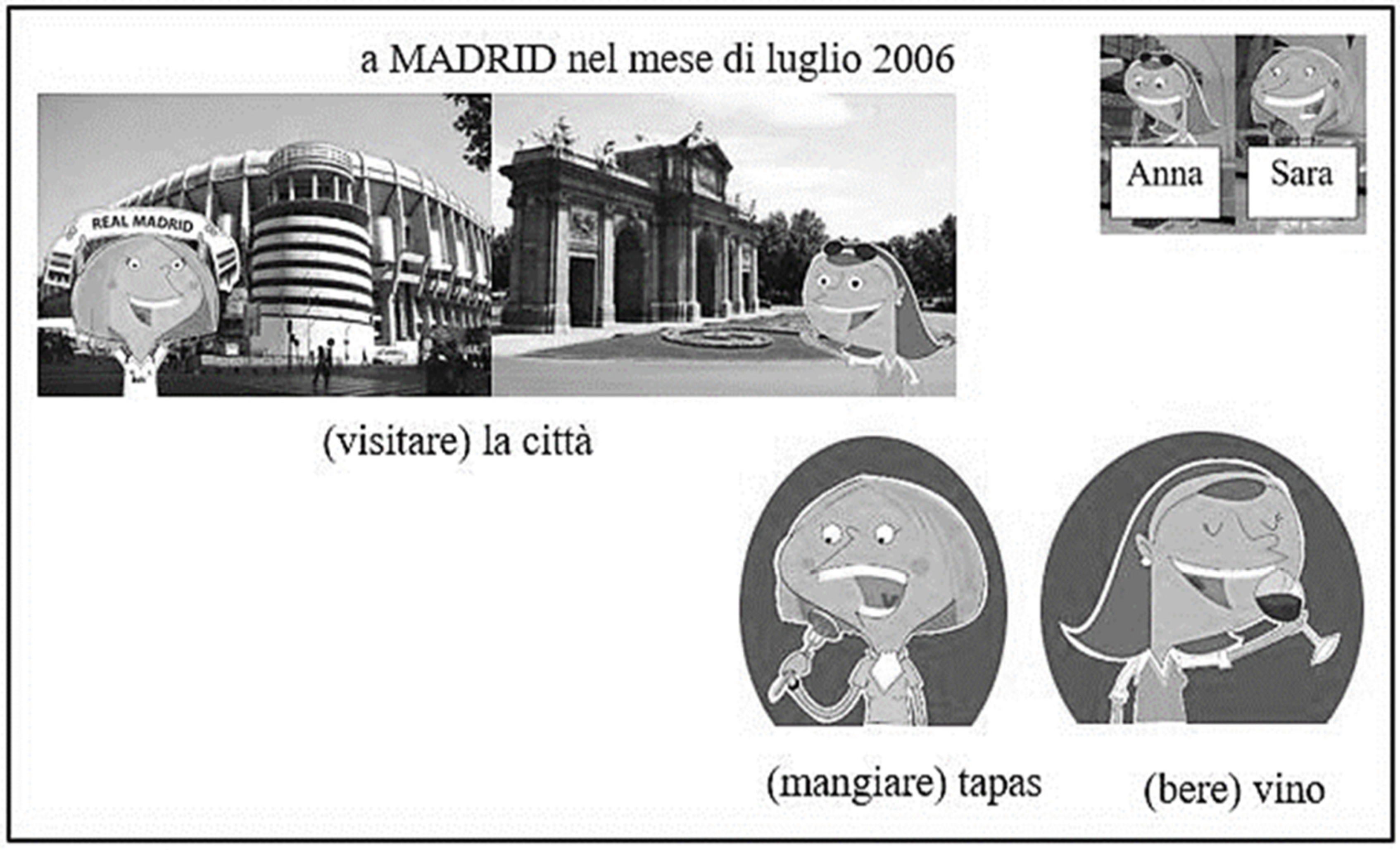

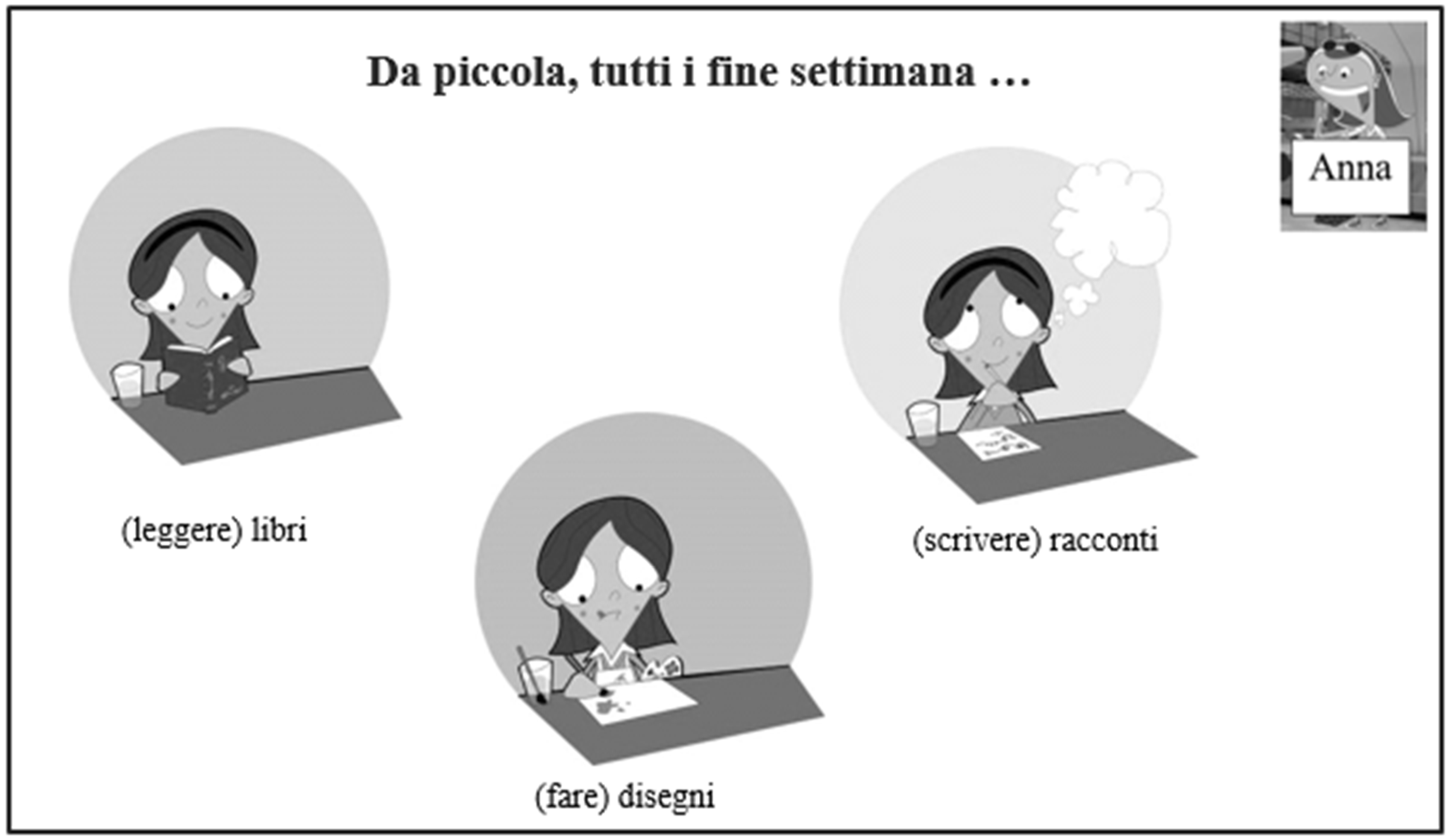

5.1. Material

5.2. Sample

5.3. Analysis of the Data

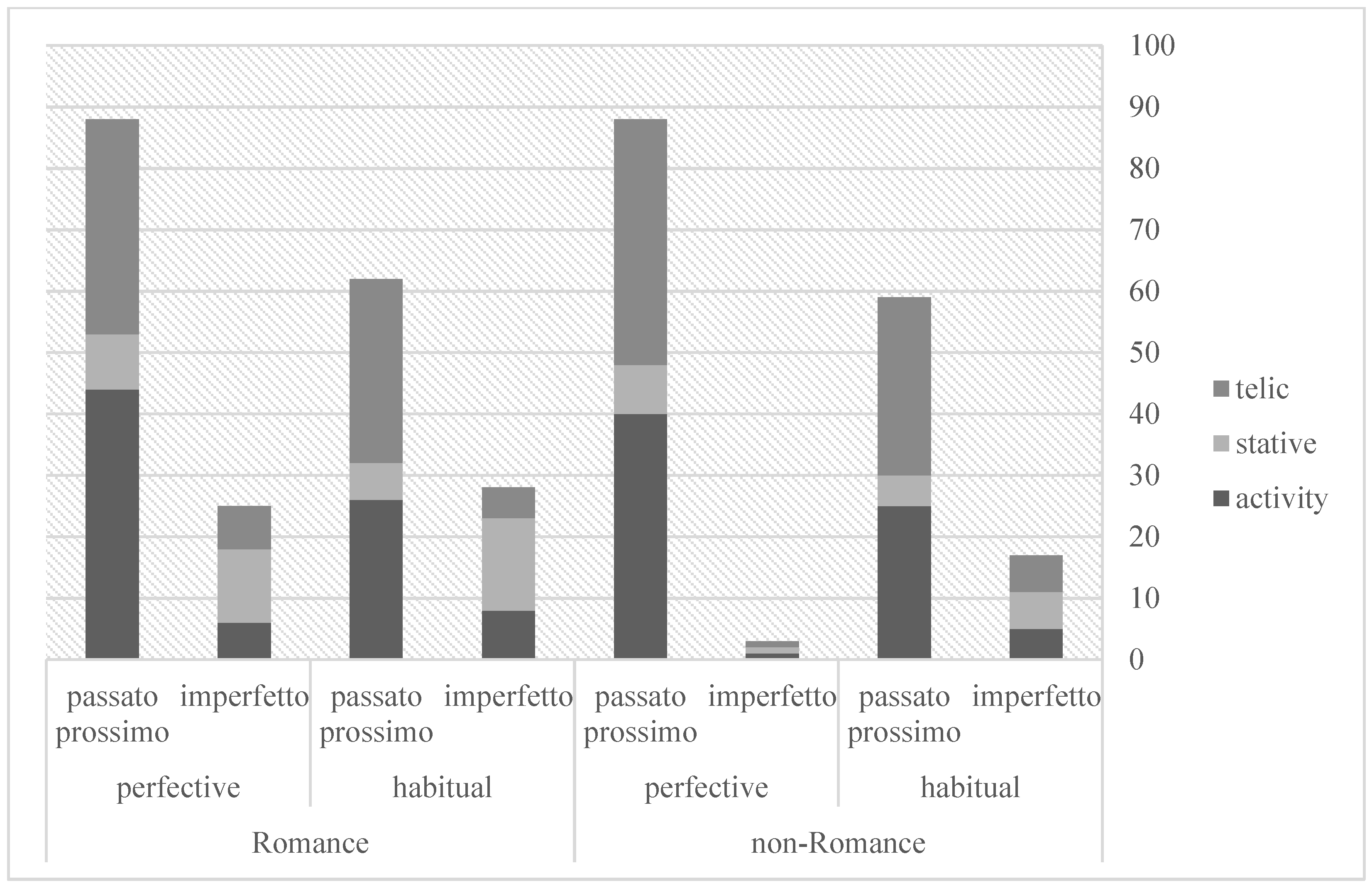

6. Results

6.1. Low-Proficiency Learners

6.2. High-Proficiency Learners

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Pp passar inte eftersom det är en avslutad händelse för länge sedan. Dåtid så sent som igår, alltså pp. Imperfetto skulle indikera längre förfluten tid. ‘Pp (passato prossimo) does not work because it is a completed event long ago. Past as late as yesterday, which is pp. Imperfetto would indicate more distant past time’.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| 1 | The SPLLOC project aimed to promote research on the acquisition of Spanish as L2 (for more details see www.splloc.soton.ac.uk accessed on 28 October 2021). |

| 2 | Overall, there were 15 female and 10 male participants. Their age ranged from 21 to 76 (M = 44.7; SD = 19.47). Twenty-one participants were recruited from seven undergraduate courses of Italian. Except for the first two preparatory courses consisting of 15 ECTS each, a full-time course generally spans over a term and consists of 30 ECTS, although some courses are also offered at half-time pace. In Sweden, there are no official guidelines concerning the correspondence between each course and proficiency level according to the Common European Framework for Languages (Council of Europe 2001). However, the most advanced course within undergraduate studies (i.e., Kandidat) implies that the student is able to write a thesis about Italian literature or linguistics. Hence, these skills would approximately be equivalent to the advanced level C1. The distribution of the participants is as follows: five participants were recruited from the first preparatory course of Italian, three from the second preparatory course, four from Italian I, four from Italian II, two from Italian III, two from Italian IV and one from the Bachelor thesis course in Italian (Kandidat). Given the difficulty in recruiting undergraduate students of Italian, the researcher also published an advertisement on social media specifying the inclusion criteria for taking part in the project; four participants responded to the advertisement. They all had knowledge of Swedish and were studying or had recently studied Italian privately or through educational associations (Studieförbund). |

| 3 | The majority of the participants completed the retelling story test during an online meeting, which was audio recorded. However, as the oral retelling story test was the last test of a test battery, a few participants had to leave the meeting. Thus, they were allowed to record themselves autonomously and to send the file to the researcher. We are aware that the absence of the researcher when these learners completed the test is problematic. However, the researcher stressed the importance of completing the test in a spontaneous way, and the participants were discouraged to plan or prepare it in advance. Because the recordings showed several traces of hesitation and uncertainty, we believe that the learners followed the instructions. Hence, all the learners were included in the final sample. |

| 4 | The English Interpretation Test, adapted from Eibensteiner (2019), aimed to test aspectual knowledge in English, operationalized in terms of the contrast between Simple Past and Progressive Past. The test consisted of 15 tasks, each including a context in Swedish and two target sentences in English. The maximum score of this test was 24. Five tasks elicited perfective contexts, with the Simple Past yielding correct interpretations, while seven tasks elicited progressive contexts, with the Progressive Past yielding correct interpretations. There were three additional distractor tasks. See Vallerossa et al. (forthcoming) for a detailed description of the English Interpretation Test. |

| 5 | It is important to point out that the constructions with the present tense observed in the study are target-like and not used to supply past tense forms not yet acquired by the learners. |

| 6 | Other forms produced by the learners are: congiuntivo imperfetto, gerundio, imperativo, infinito, infinito passato, participio passato, passato remoto, the periphrastic construction with stare + gerund and trapassato prossimo. Seven forms, which could not be categorized, were coded as “target-deviant”. |

| 7 | As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, the division into subgroups based on proficiency complicates the possibility of making any generalizations, as the number of participants resulting from the grouping criteria is limited. An alternative way would have been that of juxtaposing groups based on their knowledge of a Romance L2, or lack thereof, but disregarding proficiency in Italian. Since learners were recruited from several courses and their proficiency in Italian varied greatly, we decided to control for TL proficiency by dividing the learners into four subgroups. |

References

- Ågren, Malin, Camilla Bardel, and Susan Sayehli. 2021. Same or different? Comparing language proficiency in French, German and Spanish in Swedish lower secondary school. Paper presented at the Conference Exploring Language Education (ELE) 2021: Teaching and Learning Languages in the 21st Century, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, June 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, Roger. 1993. Four operating principles and input distribution as explanation for underdeveloped and mature morphological systems. In Progression and Regression in Language. Edited by Kenneth Hyltenstam and Åke Viberg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 309–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardel, Camilla. 2005. L’apprendimento dell’italiano come L3 di un apprendente plurilingue. Il caso del sistema verbale. In Omaggio a/Hommage à/Homenaje a Jane Nystedt [Homage to Jane Nystedt]. Edited by Michael Metzeltin. Wien: Drei Eidechsen, pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bardel, Camilla. 2006. DITALS di I e II livello per gli insegnanti di italiano in Svezia. In La DITALS risponde 3. Edited by Pierangela Diadori. Perugia: Guerra Edizioni, pp. 187–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bardel, Camilla. 2015. Lexical cross-linguistic influence in third language development. In Transfer Effects in Multilingual Language Development. Edited by Hagen Peukert. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 111–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardel, Camilla, and Christina Lindqvist. 2007. The role of proficiency and psychotypology in lexical cross-linguistic influence. A study of a multilingual learner of Italian L3. In Atti del VI Congresso Internazionale dell’Associazione Italiana di Linguistica Applicata, Napoli, 9–10 Febbraio 2006. Edited by Marina Chini, Paola Desideri, Maria Elena Favilla and Gabriele Pallotti. Perugia: Guerra Edizioni, pp. 123–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bardel, Camilla, Susan Sayehli, and Malin Ågren. Forthcoming. Developing a C-test for young learners of foreign languages at the A1-A2 level in Sweden. Methodological considerations. Manuscript in preparation.

- Bardovi-Harlig, Kathleen. 2000. Tense and Aspect in Second Language Acquisition: Form, Meaning and Use. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Bardovi-Harlig, Kathleen, and Llorenç Comajoan-Colomé. 2020. The aspect hypothesis and the acquisition of L2 past morphology in the last 20 years. A state-of-the-scholarship review. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 42: 1137–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, Anna. 1995. The Expression of Past Temporal Reference by English speaking Learners of French. Doctoral disstertation, Pennsylvania State University, Pennsylvania, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Blensenius, Kristian. 2013. En pluraktionell progressivmarkör? Hålla på att jämförd med hålla på och. Språk och stil 23: 175–204. [Google Scholar]

- Blyth, Carl. 2005. From Empirical Findings to the Teaching of Aspectual Distinctions. In Tense and Aspect in Romance Languages: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives. Edited by Dalila Ayoun and M. Rafael Salaberry. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 211–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Laura. 2002. The roles of L1 influence and lexical aspect in the acquisition of temporal morphology. Language Learning 52: 43–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diaubalick, Tim, Lukas Eibensteiner, and M. Rafael Salaberry. 2020. Influence of L1/L2 linguistic knowledge on the acquisition of L3 Spanish past tense morphology among L1 German speakers. International Journal of Multilingualism. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, Laura, Nicole Tracy-Ventura, María J. Arche, Rosamond Mitchell, and Florence Myles. 2013. The role of dynamic contrasts in the L2 acquisition of Spanish past tense morphology. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 16: 558–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibensteiner, Lukas. 2019. Transfer in L3 Acquisition: How does L2 aspectual knowledge in English influence the acquisition of perfective and imperfective aspect in L3 Spanish among German-speaking learners? Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics 8: 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Rod, and Gary Barkhuizen. 2005. Analysing Learner Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, Ylva, and Camilla Bardel. 2021. L3 proficiency and development. Some essential methodological considerations. Paper presented at L3-AIS 2021, Virtual Workshop on L3 Development after the Initial State, Boston University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and University of Applied Sciences Burgenland, Eisenstadt, Austria, October 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Foote, Rebecca. 2009. Transfer and L3 acquisition: The role of typology. In Third Language Acquisition and Universal Grammar. Edited by Yan-Kit Ingrid Leung. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Giacalone Ramat, Anna. 1990. Presentazione del progetto di Pavia sull’acquisizione di lingue seconde. Lo sviluppo di strutture temporali [Presentation of Pavia project about the acquisition of second languages. The development of temporal structures]. In La temporalità nell’acquisizione delle lingue seconde: Atti del convegno internazionale: Pavia, 28–30 ottobre 1988. Edited by Giuliano Bernini and Anna Giacalone Ramat. Milano: Franco Angeli, pp. 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- Giacalone Ramat, Anna. 2002. How do learners acquire the classical three categories of temporality? Evidence from L2 Italian. In The L2 Acquisition of Tense-Aspect Morphology. Edited by M. Rafael Salaberry and Yasuhiro Shirai. Language Acquisition and Language Disorders 27. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 200–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Paz, and Lucía Quintana Hernández. 2018. Inherent aspect and L1 transfer in the L2 acquisition of Spanish grammatical aspect. The Modern Language Journal 102: 611–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarberg, Björn. 2009. Introduction. In Processes in Third Language Acquisition. Edited by Björn Hammarberg. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Martin. 2005. Les contextes prototypiques et marqués de l’emploi de l’imparfait par l’apprenant du français langue étrangère. In Nouveaux Développements de l’imparfait. Edited by Emmanuelle Labeau and Pierre Larrivée. New York and Amsterdam: Rodopi, pp. 175–97. [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo, Jesús, and Laura Collins. 2008. The facilitative role of L1 influence in tense-aspect marking: A comparison of Hispanophone and Anglophone learners of French. The Modern Language Journal 92: 350–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, Jesús, and Maria Kihlstedt. 2019. L2 Imperfective functions with verb types in written narratives: A cross-sectional study with instructed Hispanophone learners of French. The Modern Language Journal 103: 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessner, Ulrike. 2006. Linguistic Awareness in Multilinguals: English as a Third Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kihlstedt, Maria. 2002. Reference to past events in dialogue: The acquisition of tense and aspect by advanced learners of French. In The L2 Acquisition of Tense-Aspect Morphology. Edited by M. Rafael Salaberry and Yasuhiro Shirai. Language Acquisition and Language Disorders 27. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 323–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, Wolfgang. 2009. How Time is encoded. In The Expression of Time. Edited by Wolfgang Klein and Ping Li. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 39–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klein-Braley, Christine. 1985. A cloze-up on the C-Test: A study in the construct validation of authentic tests. Language Testing 2: 76–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein-Braley, Christine. 1997. C-Tests in the context of reduced redundancy testing: An appraisal. Language Testing 14: 47–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labeau, Emmanuelle. 2005. Beyond the Aspect Hypothesis. Tense-aspect development in advanced L2 French. EUROSLA Yearbook 5: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, Kevin. 2011. The Development of Aspect in a Second Language. Doctoral dissertation, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. Available online: http://theses.ncl.ac.uk/jspui/handle/10443/1292 (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- McManus, Kevin. 2015. L1/L2 differences in the acquisition of form-meaning pairings: A comparison of English and German learners of French. The Canadian Modern Language Review 71: 51–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaberry, M. Rafael. 2000. The Development of Past Tense Morphology in L2 Spanish. Studies in Bilingualism 22. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaberry, M. Rafael. 2005. Evidence for transfer of knowledge of aspect from L2 Spanish to L3 Portuguese. In Tense and Aspect in Romance Languages: Theoretical and Applied Perspectives. Edited by Dalila Ayoun and M. Rafael Salaberry. Studies in Bilingualism 29. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 179–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaberry, M. Rafael. 2008. Marking Past Tense in Second Language Acquisition. A Theoretical Model. London and New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Salaberry, M. Rafael. 2020. The conceptualization of knowledge about aspect. In Third Language Acquisition: Age, Proficiency and Multilingualism. Edited by Camilla Bardel and Laura Sánchez. Eurosla Studies 3. Berlin: Language Science Press, pp. 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Laura, and Camilla Bardel. 2017. Transfer from an L2 in third language learning: A study on L2 proficiency. In L3 syntactic Transfer: Models, New Developments and Implications. Edited by Tanja Angelovska and Angela Hahn. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, pp. 223–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, Yasuhiro, and Roger Andersen. 1995. The acquisition of tense/aspect morphology: A prototype account. Language 71: 743–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Carlota. 1997. The Parameter of Aspect (Studies in Linguistics and Philosophy 43). Dordrecht, Boston and London: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Vallerossa, Francesco. 2021. L’apprendimento dell’italiano in prospettiva multilingue: Il sistema tempo-aspettuale. Paper presented at University for Foreigners of Siena, Siena, Italy, October 11. [Google Scholar]

- Vallerossa, Francesco, and Camilla Bardel. Forthcoming. ”He was finishing his homework or il finissait ses devoirs”: A case study of multilingual students’ reflections on Romance verb morphology. Manuscript in preparation.

- Vallerossa, Francesco, Anna Gudmundson, Anna Bergström, and Camilla Bardel. Forthcoming. Learning aspect in Italian as additional language. The role of second languages. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, Submitted.

- Wiberg, Eva. 1996. Reference to past events in bilingual Italian-Swedish children of school age. Linguistics 34: 1087–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Sarah, and Björn Hammarberg. 2009. Language switches in L3 production: Implications for a polyglot speaking model. In Processes in Third Language Acquisition. Edited by Björn Hammarberg. Edinburgh: EUP, pp. 28–73, Originally in Applied Linguistics 19: 295–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff, Stefanie, Nick C. Ellis, Ute Römer, Kathleen Bardovi-Harlig, and Chelsea J. Leblanc. 2009. The acquisition of tense–aspect: Converging evidence from corpora and telicity ratings. The Modern Language Journal 93: 354–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Swedish | Romance | |

|---|---|---|

| Perfective | Jag läste en bok igår ‘I read.PAST a book yesterday’ | Ho letto un libro ieri J’ai lu un livre hier Leí un libro ayer ‘I read.PERF a book yesterday’ |

| Imperfective Habitual | Jag läste mycket som barn ‘I read.PAST a lot as a child’ | Da piccolo leggevo molto En tant qu’enfant je lisais beaucoup De pequeño leía mucho ‘As a child I read.IMP a lot’ |

| Imperfective Progressive | Jag läste en bok igår ‘I read.PAST a book yesterday’ Jag höll på att läsa en bok igår ‘I keep on.PAST to read.INF a book yesterday’ | Leggevo un libro ieri Je lisait un livre hier Leía un libro ayer ‘I read.IMP a book yesterday’ |

| States | Activities | Telic | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perfective | (riflettere) sulla causa dell’incidente “reflect on the cause of the accident” (avere) posti nuovi “have new seats” | (mangiare) tapas “eat tapas” (bere) vino “drink wine” (visitare) la città “visit the city” (parlare) della loro infanzia “talk about their childhood” | (prendere) il treno “take the train” (sentire) gocce d’acqua “feel water drops” (tranquillizzarsi) “calm down” (chiedere) aiuto al controllore “ask the ticket collector for help” (essere) un incidente1 “have an accident” |

| Imperfective Habitual | (essere) molto diverse “be very different” | (leggere) un libro “read a book” (fare) disegni “make drawings” (fare) i compiti la notte “do homework at night” (scrivere) un racconto “write a novel” (giocare) a calcio “play football” | (andare) a scuola in bicicletta “bike to school” (andare) al cinema “go to the cinema” (finire) i compiti presto “do homework early” (alzarsi) presto “wake up early” (arrivare) tardi a scuola “arrive late at school” (addormentarsi) tardi “fall asleep late” |

| C-Test Italian | C-Test Romance | EIT | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | p | n | M | SD | p | n | M | SD | p | ||

| Low-Proficiency | Non-Rom | 6 | 40.67 | 6.18 | 0.716 | 6 | 15.33 | 3.09 | 0.481 | ||||

| Rom | 7 | 39.43 | 5.8 | 7 | 51.14 | 6.06 | 0.538 | 7 | 16.57 | 3.02 | |||

| High-Proficiency | Non-Rom | 4 | 59 | 2.74 | 0.515 | 4 | 19.5 | 2.06 | 0.220 | ||||

| Rom | 8 | 57.63 | 3.53 | 8 | 48.25 | 10.65 | 8 | 17.38 | 2.87 | ||||

| Non-Romance | Romance | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Passato prossimo | 88 | 77.88% | 88 | 65.67% | 176 | 71.26% |

| activity | 40 | 35.40% | 44 | 32.84% | 84 | 34.01% |

| stative | 8 | 7.08% | 9 | 6.72% | 17 | 6.88% |

| telic | 40 | 35.40% | 35 | 26.12% | 75 | 30.36% |

| Imperfetto | 3 | 2.65% | 25 | 18.66% | 28 | 11.34% |

| activity | 1 | 0.88% | 6 | 4.48% | 7 | 2.83% |

| stative | 1 | 0.88% | 12 | 8.96% | 13 | 5.26% |

| telic | 1 | 0.88% | 7 | 5.22% | 8 | 3.24% |

| Present | 11 | 9.73% | 9 | 6.72% | 20 | 8.10% |

| activity | 1 | 0.88% | 1 | 0.75% | 2 | 0.81% |

| stative | 6 | 5.31% | 7 | 5.22% | 13 | 5.26% |

| telic | 4 | 3.54% | 1 | 0.75% | 5 | 2.02% |

| Other | 11 | 9.73% | 12 | 8.96% | 23 | 9.31% |

| activity | 3 | 2.65% | 4 | 2.99% | 7 | 2.83% |

| stative | 2 | 1.77% | 1 | 0.75% | 3 | 1.21% |

| telic | 6 | 5.31% | 7 | 5.22% | 13 | 5.26% |

| Total | 113 | 100% | 134 | 100% | 247 | 100% |

| Non-Romance | Romance | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Passato prossimo | 59 | 67.05% | 62 | 60.78% | 121 | 63.68% |

| activity | 25 | 28.41% | 26 | 25.49% | 51 | 26.84% |

| stative | 5 | 5.68% | 6 | 5.88% | 11 | 5.79% |

| telic | 29 | 32.95% | 30 | 29.41% | 59 | 31.05% |

| Imperfetto | 17 | 19.32% | 28 | 27.45% | 45 | 23.68% |

| activity | 5 | 5.68% | 8 | 7.84% | 13 | 6.84% |

| stative | 6 | 6.82% | 15 | 14.71% | 21 | 11.05% |

| telic | 6 | 6.82% | 5 | 4.90% | 11 | 5.79% |

| Present | 10 | 11.36% | 4 | 3.92% | 14 | 7.37% |

| activity | 0.00% | 3 | 2.94% | 3 | 1.58% | |

| stative | 9 | 10.23% | 1 | 0.98% | 10 | 5.26% |

| telic | 1 | 1.14% | 0.00% | 1 | 0.53% | |

| Other | 2 | 2.27% | 8 | 7.84% | 10 | 5.26% |

| activity | 0.00% | 1 | 0.98% | 1 | 0.53% | |

| telic | 2 | 2.27% | 7 | 6.86% | 9 | 4.74% |

| Total | 88 | 100% | 102 | 100% | 190 | 100% |

| Non-Romance | Romance | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Passato prossimo | 69 | 67.65% | 154 | 70.64% | 223 | 69.69% |

| activity | 19 | 18.63% | 53 | 24.31% | 72 | 22.50% |

| stative | 3 | 2.94% | 19 | 8.72% | 22 | 6.88% |

| telic | 47 | 46.08% | 82 | 37.61% | 129 | 40.31% |

| Imperfetto | 22 | 21.57% | 21 | 9.63% | 43 | 13.44% |

| activity | 8 | 7.84% | 6 | 2.75% | 14 | 4.38% |

| stative | 10 | 9.80% | 12 | 5.50% | 22 | 6.88% |

| telic | 4 | 3.92% | 3 | 1.38% | 7 | 2.19% |

| Present | 4 | 3.92% | 22 | 10.09% | 26 | 8.13% |

| activity | 0.00% | 1 | 0.46% | 1 | 0.31% | |

| stative | 3 | 2.94% | 18 | 8.26% | 21 | 6.56% |

| telic | 1 | 0.98% | 3 | 1.38% | 4 | 1.25% |

| Other | 7 | 6.86% | 21 | 9.63% | 28 | 8.75% |

| activity | 4 | 3.92% | 10 | 4.59% | 14 | 4.38% |

| stative | 1 | 0.98% | 4 | 1.83% | 5 | 1.56% |

| telic | 2 | 1.96% | 7 | 3.21% | 9 | 2.81% |

| Total | 102 | 100% | 218 | 100% | 320 | 100% |

| Non-Romance | Romance | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Passato prossimo | 3 | 5.17% | 14 | 9.72% | 17 | 8.42% |

| stative | 0.00% | 5 | 3.47% | 5 | 2.48% | |

| telic | 3 | 5.17% | 9 | 6.25% | 12 | 5.94% |

| Imperfetto | 52 | 89.66% | 121 | 84.03% | 173 | 85.64% |

| activity | 19 | 32.76% | 45 | 31.25% | 64 | 31.68% |

| stative | 9 | 15.52% | 33 | 22.92% | 42 | 20.79% |

| telic | 24 | 41.38% | 43 | 29.86% | 67 | 33.17% |

| Present | 1 | 1.72% | 6 | 4.17% | 7 | 3.47% |

| stative | 1 | 1.72% | 4 | 2.78% | 5 | 2.48% |

| telic | 0.00% | 2 | 1.39% | 2 | 0.99% | |

| Other | 2 | 3.45% | 3 | 2.08% | 5 | 2.48% |

| activity | 1 | 1.72% | 0.00% | 1 | 0.50% | |

| telic | 1 | 1.72% | 3 | 2.08% | 4 | 1.98% |

| Total | 58 | 100% | 144 | 100% | 202 | 100% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vallerossa, F. The Role of Linguistic Typology, Target Language Proficiency and Prototypes in Learning Aspectual Contrasts in Italian as Additional Language. Languages 2021, 6, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040184

Vallerossa F. The Role of Linguistic Typology, Target Language Proficiency and Prototypes in Learning Aspectual Contrasts in Italian as Additional Language. Languages. 2021; 6(4):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040184

Chicago/Turabian StyleVallerossa, Francesco. 2021. "The Role of Linguistic Typology, Target Language Proficiency and Prototypes in Learning Aspectual Contrasts in Italian as Additional Language" Languages 6, no. 4: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040184

APA StyleVallerossa, F. (2021). The Role of Linguistic Typology, Target Language Proficiency and Prototypes in Learning Aspectual Contrasts in Italian as Additional Language. Languages, 6(4), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6040184