Word Order, Intonation, and Prosodic Phrasing: Individual Differences in the Production and Identification of Narrow and Wide Focus in Urdu

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Word Order and Information Structure in Urdu and Hindi

| (1) | XPTopic XPFocus Complex Predicate XPBackground/de-emphasis etc. |

| (2) | a. | Ẇhat happened? |

| b. | nɑ:z=ne seb khɑ.jɑ | |

| Naz=Erg apple.M.Sg eat.Perf.M.Sg | ||

| ‘Naz ate an apple’. | ||

| c. | Who ate an apple? | |

| d. | seb nɑ:z=neFocus khɑ.jɑ | |

| apple.M.Sg Naz=Erg eat.Perf.M.Sg | ||

| ‘Naz ate an apple’. |

1.2. Prosody of South Asian Languages

1.2.1. Bengali

1.2.2. Tamil

1.2.3. Hindi

1.3. Prosodic Phrasing in Urdu

1.3.1. Accentual Phrases

| (3) | Lp Hp |

| ʃɑ.ˈhi:.nɑ:=ne | |

| Shahina=Erg |

| (4) | Lp Hp LpHp |

| ʃɑ.ˈhi:.nɑ= neFocus |

1.3.2. Intonational Phrases

Recursive IPs in Urdu

| (5) | 213 - 4567 - 76 |

| (6) | a. | (2)AP (13)AP - (45)AP (67)AP - (76)AP | AP phrasing |

| b. | ((213)IP - (4567)IP - 76)IP | IP phrasing |

1.3.3. Focus Realization in Urdu

1.4. Individual Variation in Using Prosodic Cues

1.5. Research Questions

- Do speakers from a homogenous group in terms of age, gender, and education differ in their use of word order and intonation? (Interspeaker variation)

- Does an individual speaker vary in their use of word order and intonation? (Intraspeaker variation)

- To what extent are speakers’ productions correctly identified with reference to focus type and the position of focused nouns?

- Do the differences in word order and intonation affect the prosodic phrasing of declaratives produced in wide and narrow focus?

2. Methods: Production Experiment

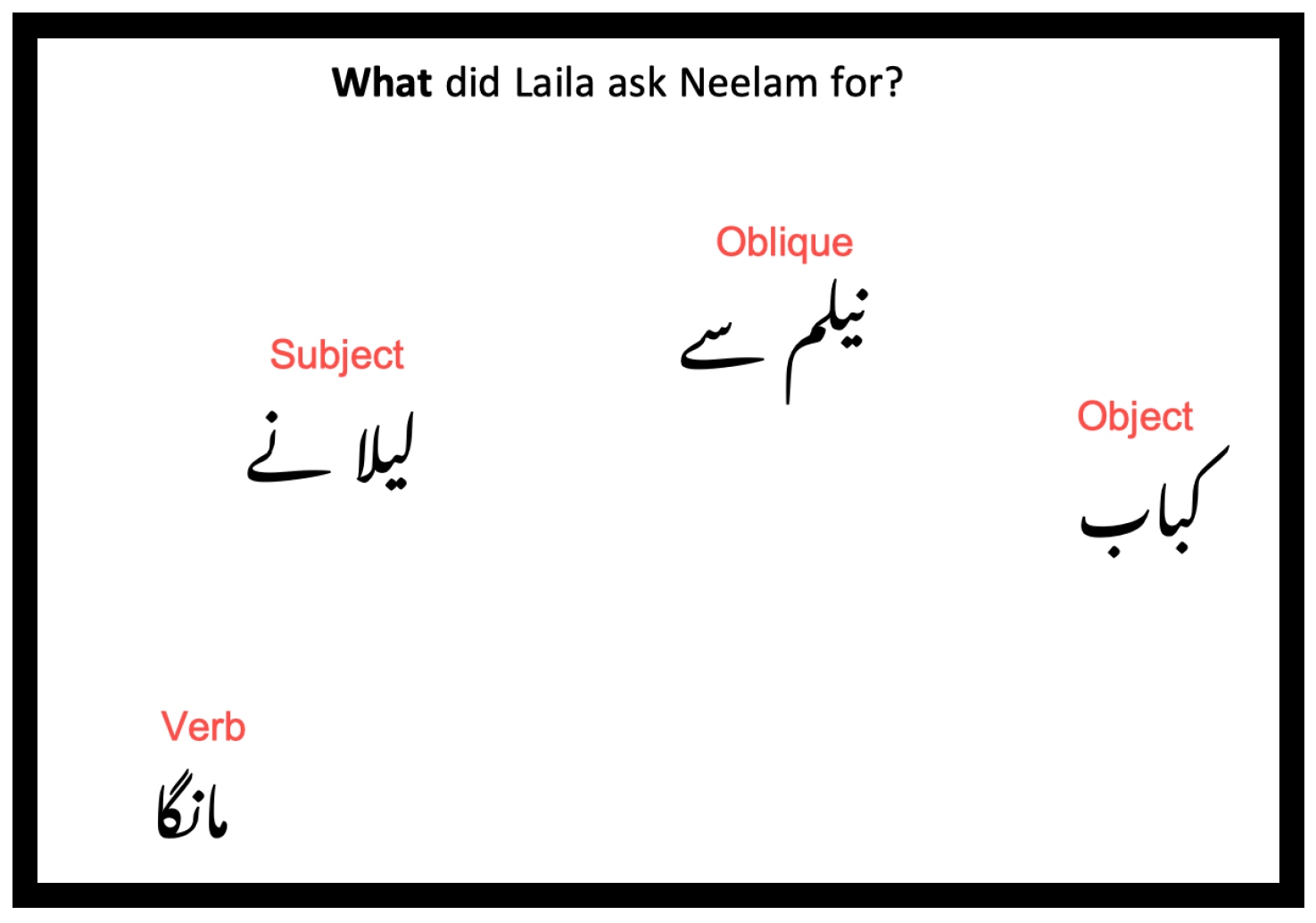

2.1. Material

| (7) | a. | What happened? | Wide focus |

| b. | Who asked Neelam for a kebab? | Subject focus | |

| c. | Whom did Laila ask for a kebab? | Oblique focus | |

| d. | What did Laila ask from Neelam? | Object focus | |

| e. | lɛ.lɑ=ne ni:.ləm=se kə.bɑ:b mã:.gɑ | ||

| Laila=Erg Neelam=Obl kebab.Nom.M ask.Perf.M.Sg | |||

| ‘Laila asked Neelam for a kebab’. |

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Word Order

2.4.2. Intonational Analysis

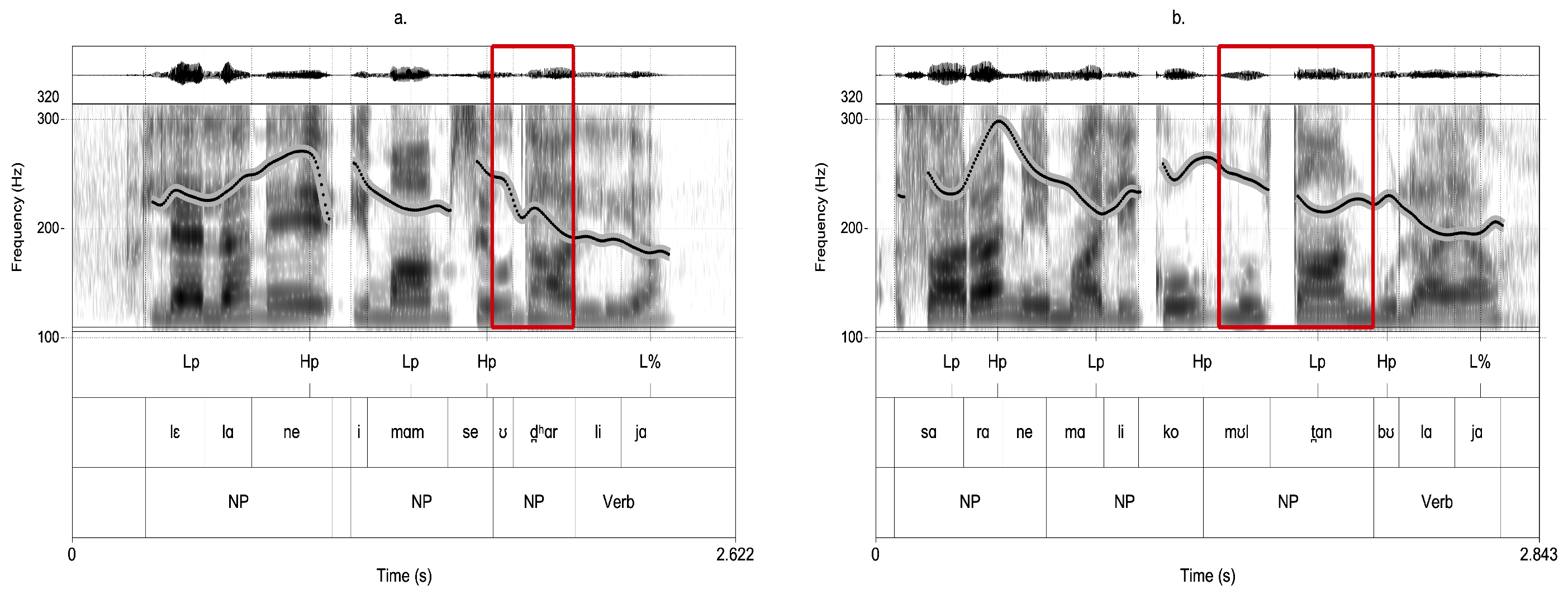

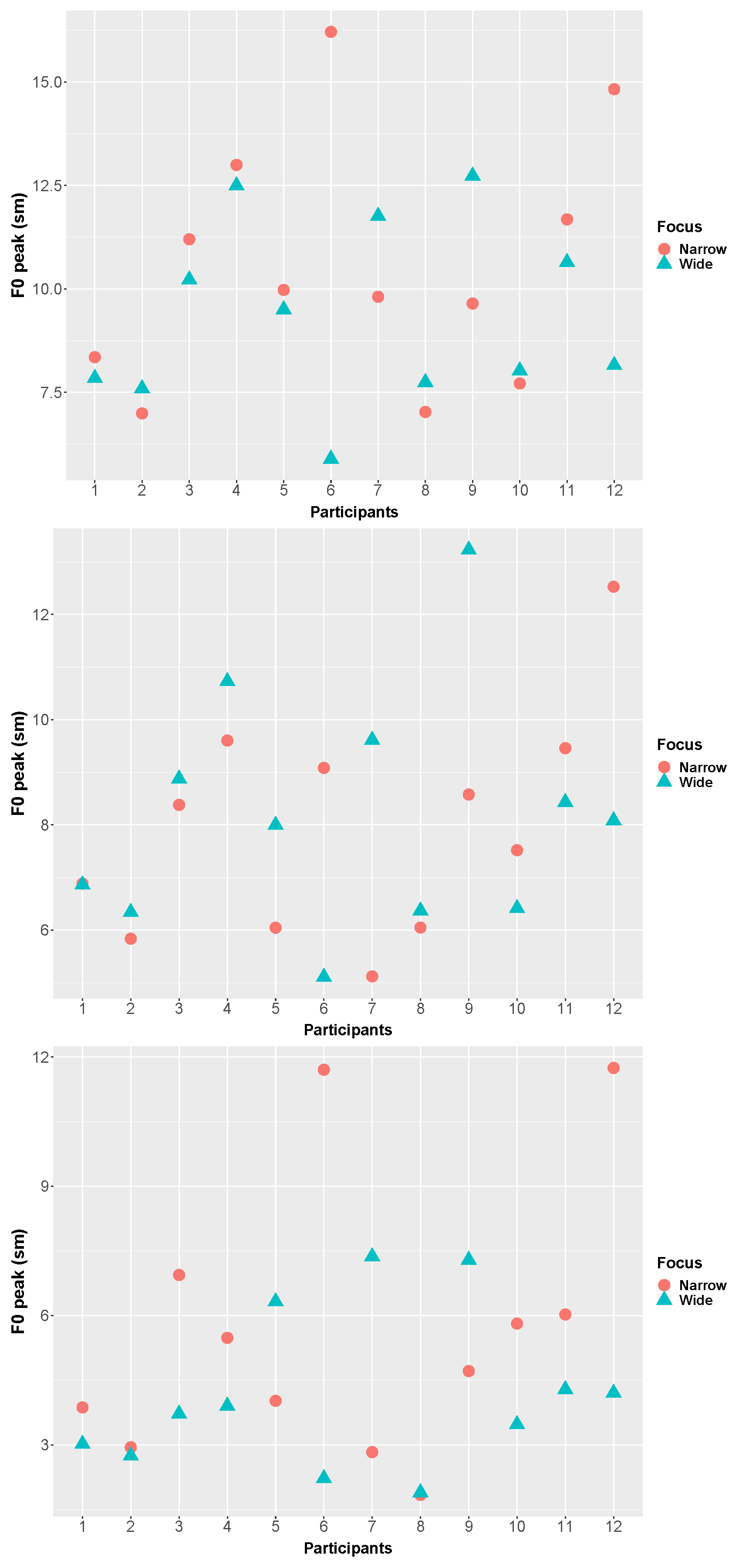

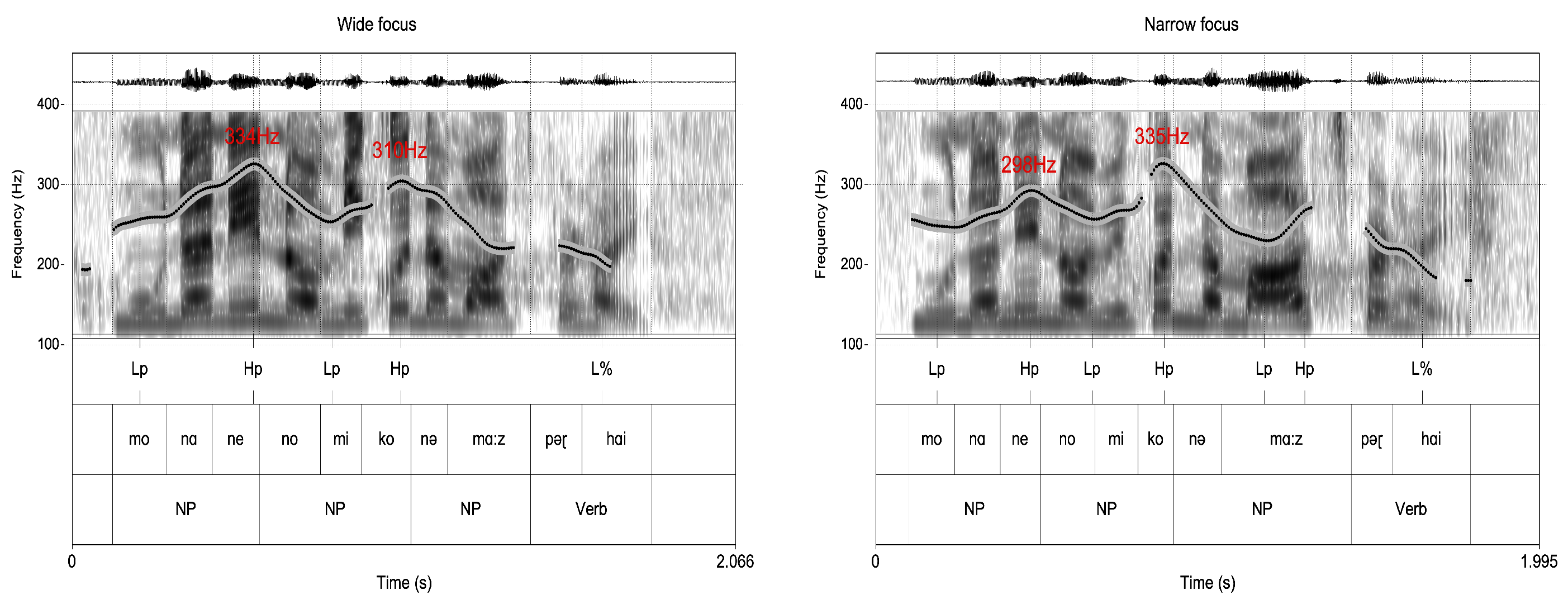

F0 Contour and Peak Scaling

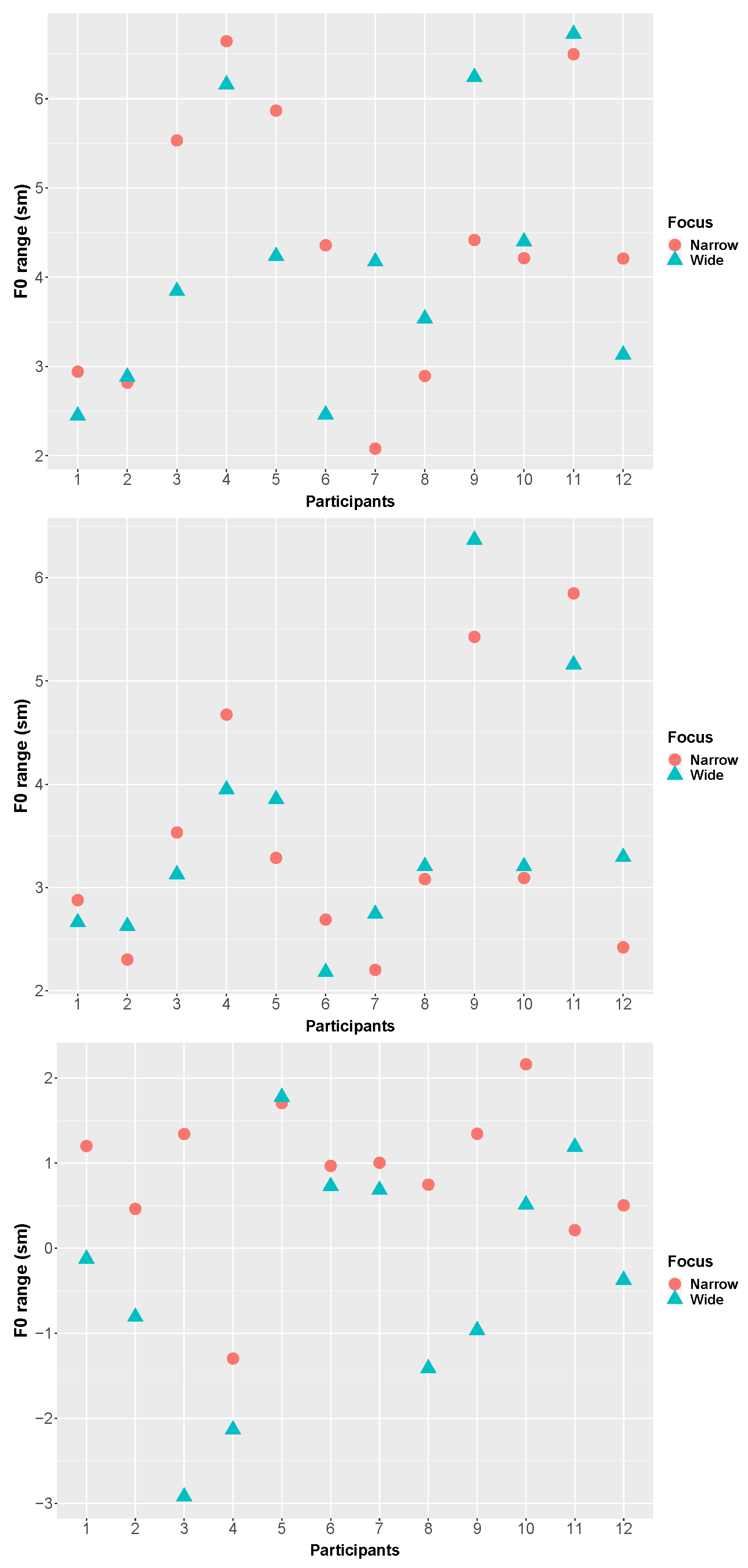

F0 Range

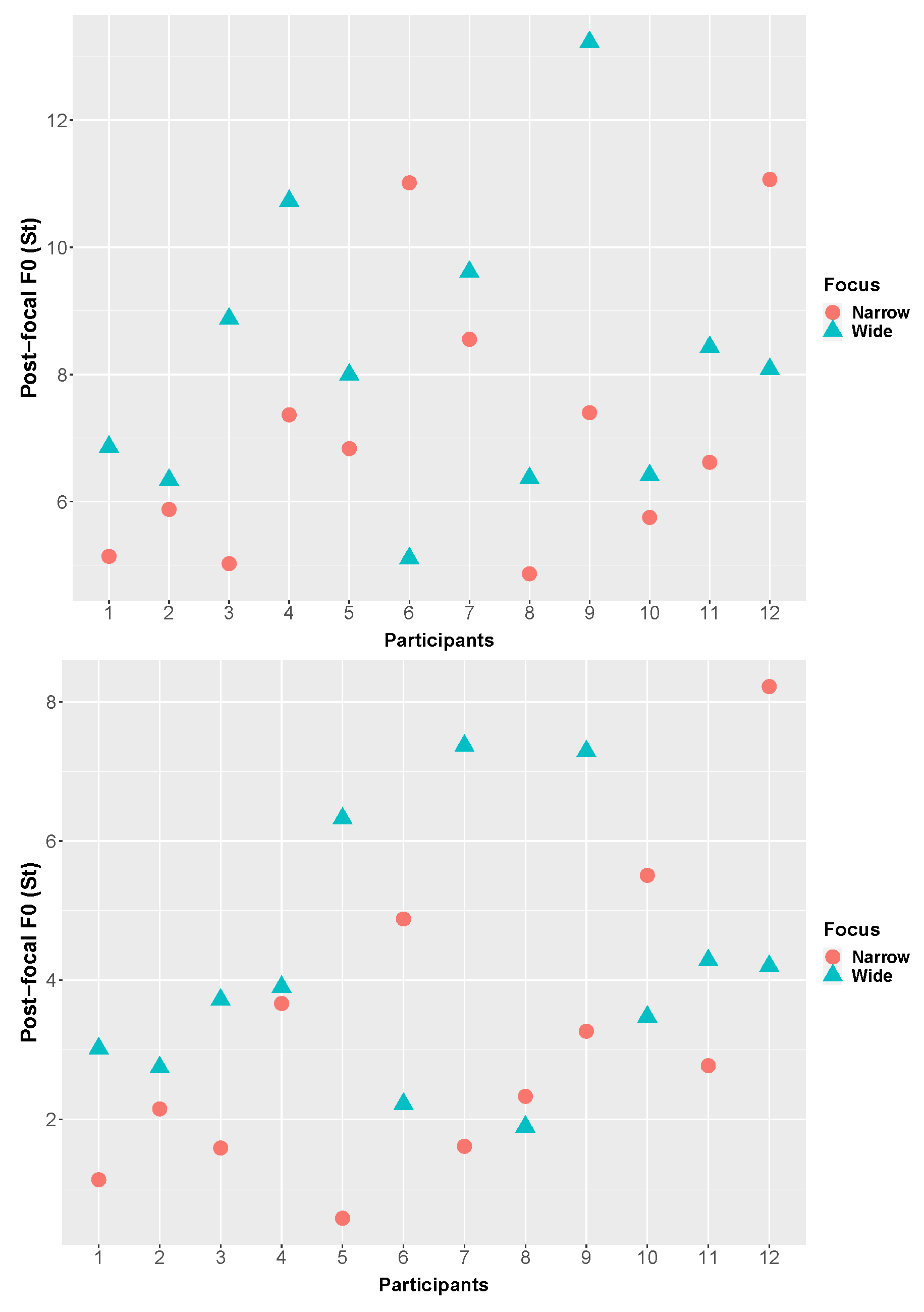

Postfocal Compression

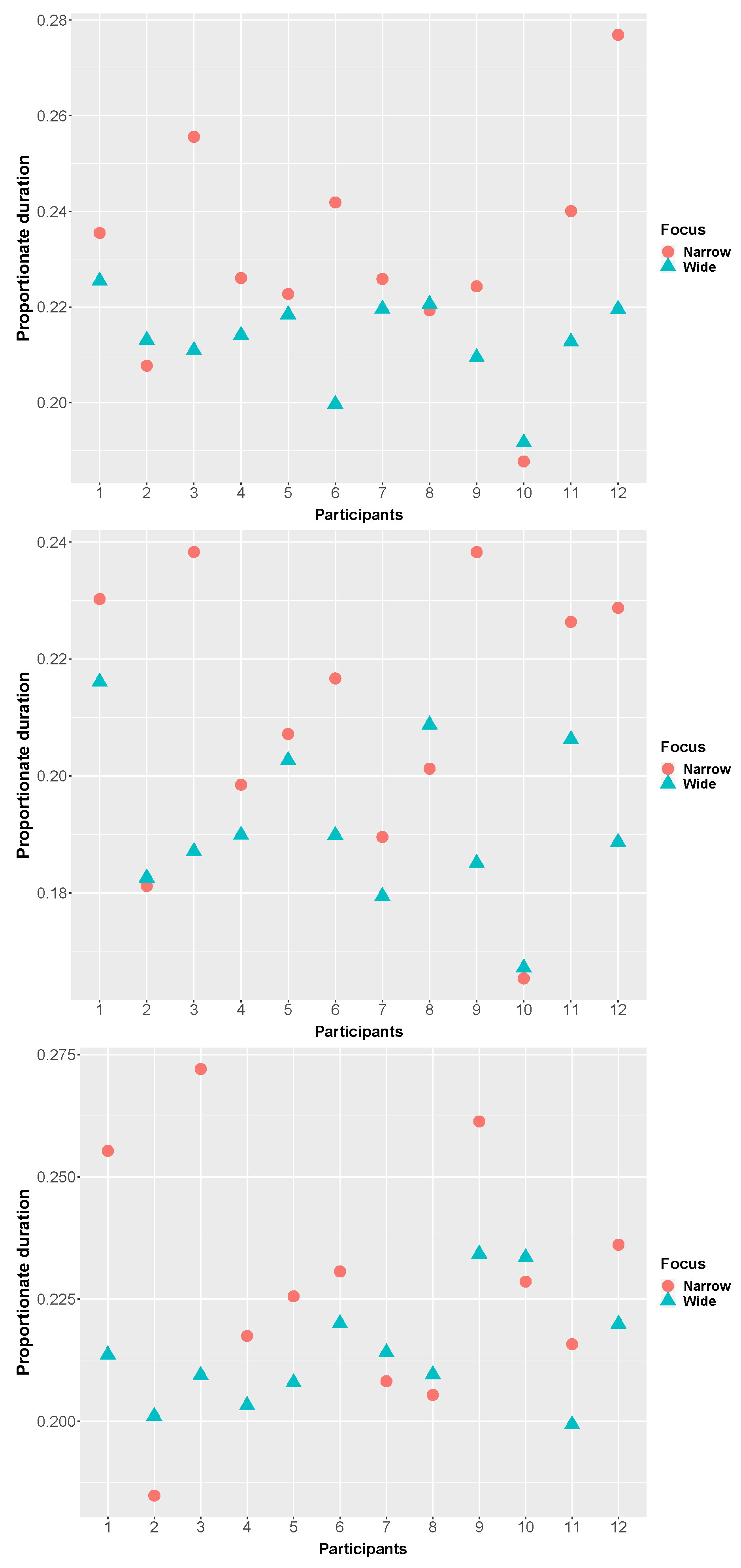

Proportionate Duration

2.4.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results: Production Experiment

3.1. Word Order

3.2. F0 Contour in Wide Focus

3.3. F0 Peak Scaling

3.4. F0 Range

3.5. Proportionate Duration

3.6. Summary

4. Discussion: Production Experiment

4.1. Phonetic Cues

4.2. Word Order

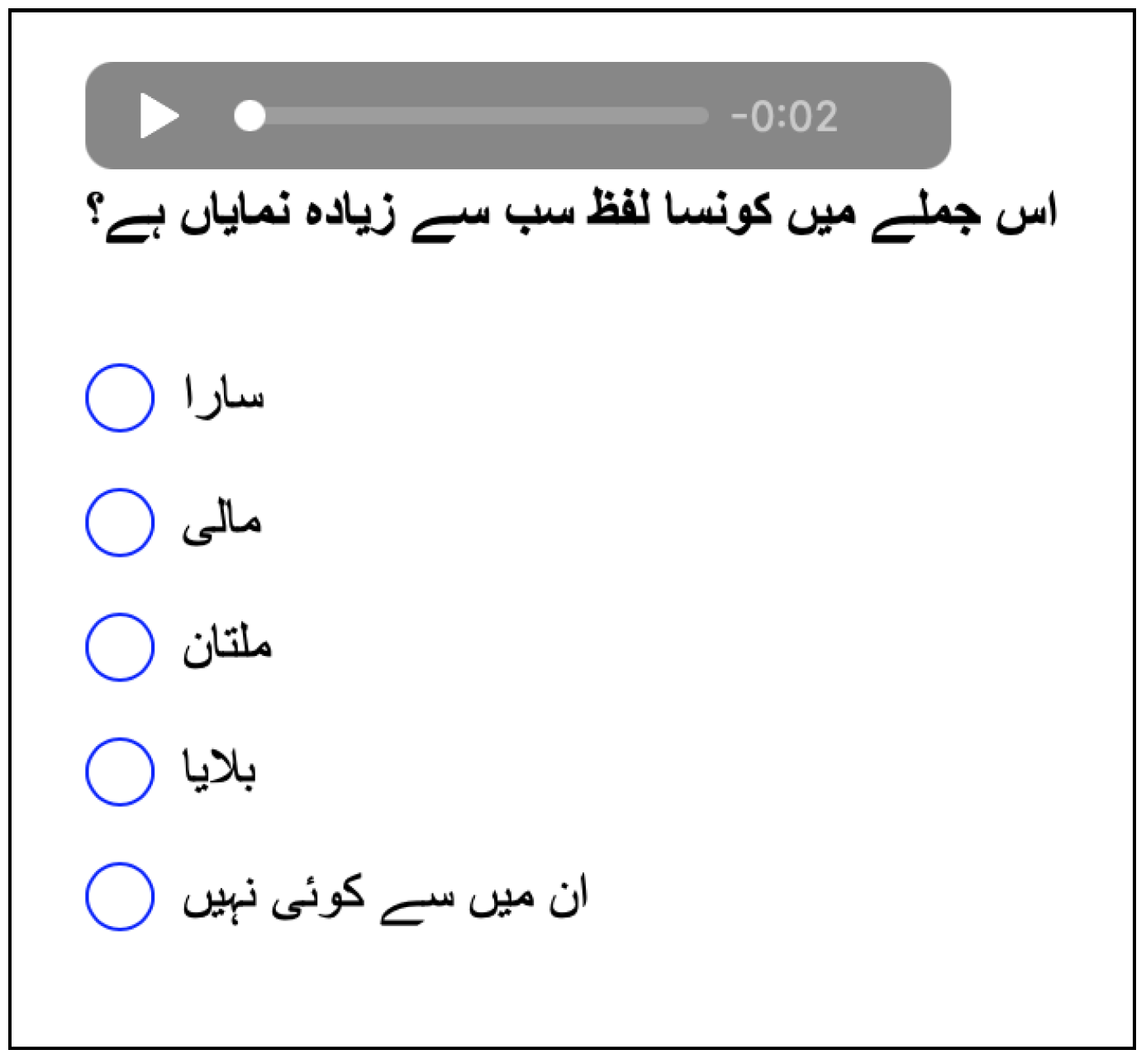

5. Identification of Focus Type and Position

5.1. Methods: Focus Identification

5.1.1. Apparatus and Stimuli

5.1.2. Participants

5.1.3. Data Analysis

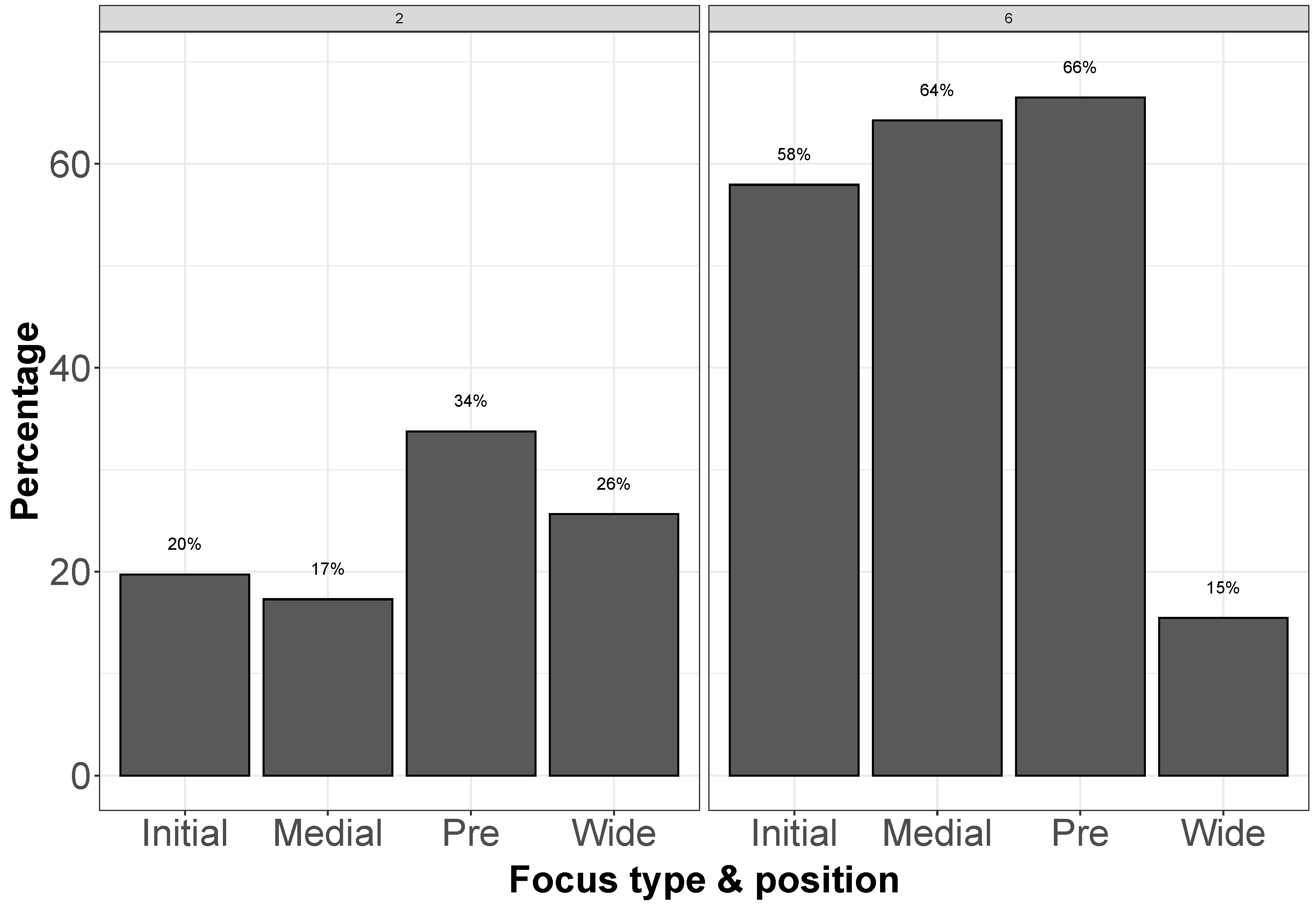

5.2. Results: Focus Identification

5.3. Discussion: Focus Identification

6. Prosodic Phrasing

6.1. Prefocal Upstepping

6.2. Prefocal Lengthening

6.3. Postfocal Compression

6.4. Discussion: Prosodic Phrasing

| (8) | a. | [ [Subject]IP ObjectFocus Object Verb]IP | Medial narrow focus |

| b. | [ Subject Object Object Verb]IP | Wide focus |

| (9) | a. | [ Subject [ObjectFocus Object Verb]IP ]IP |

7. Identification of Prosodic Phrasing

| (10) | a. | The sentences with wide or narrow focus formulate one IP and the use of narrow focus does not affect prosodic phrasing at the IP level. |

| b. | There is a recursive Intonational Phrase boundary on the left edge of narrowly focused nouns. | |

| c. | There is an Intermediate Phrase boundary on the left edge of narrowly focused nouns. |

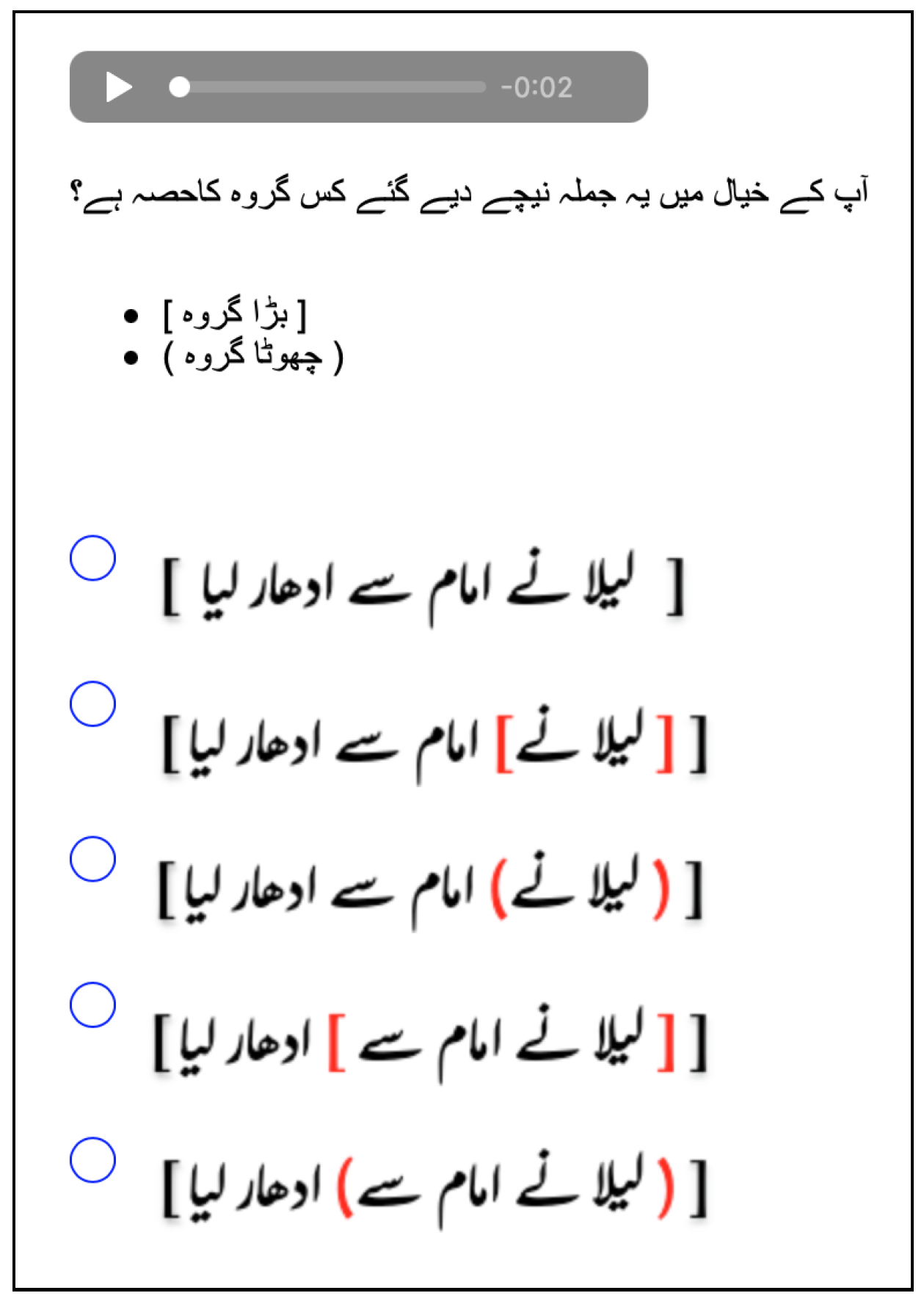

7.1. Methods: Phrasing Identification

7.1.1. Apparatus

| (11) | a. | [Subject Object Noun Verb] | One Intonational Phrase |

| b. | [ [Subject Object] Noun Verb] | IP embedded in IP | |

| c. | [ (Subject Object) Noun Verb] | ip embedded in IP |

| (12) | a. | [Subject Object Noun Verb] | One IP |

| b. | [ [Subject] Object Noun Verb ] | Recursive IP | |

| c. | [ (Subject) Object Noun Verb ] | ip within IP | |

| d. | [ [Subject Object] Noun Verb ] | Recursive IP | |

| e. | [ (Subject Object) Noun Verb ] | ip within IP |

7.1.2. Stimuli

7.1.3. Participants

7.1.4. Data Analysis

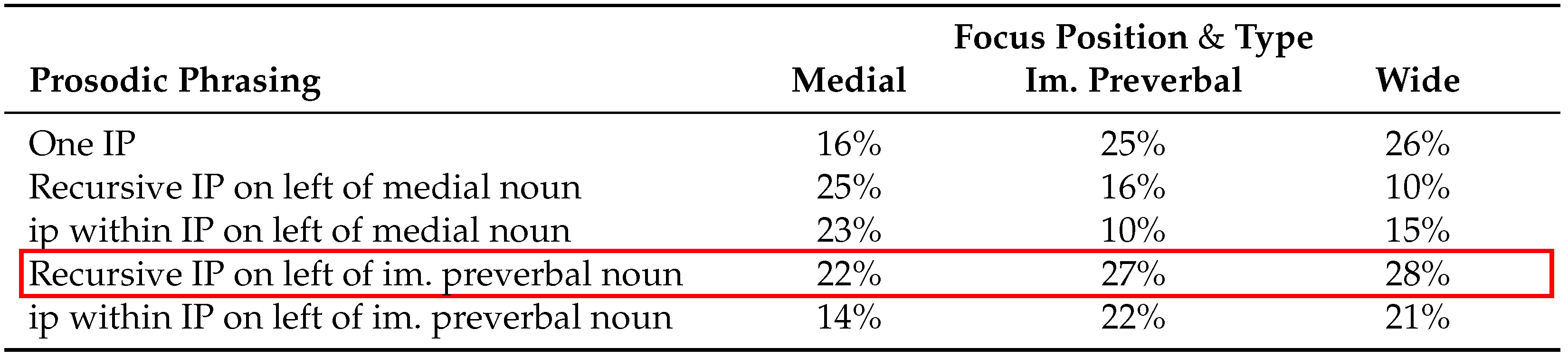

7.2. Results: Phrasing Identification

8. General Discussion

8.1. Word Order and Intonation

8.2. Syntax–Phonology Interface

8.3. Position and (Non-)Specificity

8.4. Prosodic Phrasing

8.4.1. Recursive AP Boundary

| (13) | a. | [ NP1 | NP2Focus | NP3 Verb ] | Medial narrow focus |

| b. | [ NP1 NP2 | NP3Focus Verb ] | Im. preverbal narrow focus | |

| c. | [ NP1 NP2 | NP3 Verb ] | Wide focus |

| (14) | a. | (NP1)AP (NP2)AP (NP3 Verb)AP | Wide focus |

| b. | (NP1)AP (NP2)AP (NP3)AP (Verb)AP | Im. preverbal narrow focus |

8.4.2. Recursive IP Boundary

| (15) | a. | [ NP1 NP2 NP3 Verb ]IP | Wide focus |

| b. | [ [NP1 NP2 ]IP NP3Focus Verb ]IP | Im. preverbal narrow focus |

8.4.3. Intermediate Phrase Boundary

8.4.4. Structural Phrase Boundary

| (16) | a. | [ [NP1 ]IP NP2Focus | NP3 Verb ]IP | Medial narrow focus |

| b. | [ [NP1 NP2 ]IP NP3Focus Verb ]IP | Im. preverbal narrow focus | |

| c. | [ NP1 NP2 | NP3 Verb ]IP | Wide focus |

| (17) | [ [NP1 NP2 ]IP NP3 Verb ]IP | Wide focus |

8.5. Variation in Prosodic Phrasing

| (18) | a. | (NP1)AP NP2 NP3 Verb | Initial narrow focus |

| b. | (NP1)AP (NP2)AP (NP3 Verb)AP | Wide focus |

9. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IP | Intonational Phrase |

| ip | Intermediate Phrase |

| AP | Accentual Phrase |

| SA | South Asian |

Appendix A. Data Set

| a. | mo.nɑ=ne no.mi=ko nə.mɑ:z pəɽ.hɑi |

| Mona=Erg Nomi=Acc prayer.Nom.F.Sg read.Perf.F.Sg | |

| ‘Mona had Nomi say a/the prayer’. | |

| b. | nɛ.nɑ=ne lɛ.lɑ=ko ʧə.nɑ:b=mẽ ph.kɑ |

| Naina=Erg Laila=Acc Chenab=in throw.Perf.M.Sg | |

| ‘Naina threw Laila in (the river) Chenab’. | |

| c. | sɑ.rɑ=ne mɑ.li=ko mʊl.t̪ɑ:n bʊ.lɑ.jɑ |

| Sara=Erg gardner.M.Sg=Acc Multan call.Perf.M.Sg | |

| ‘Sara summoned a/the gardner to (the city of) Multan’. | |

| d. | lɛ.lɑ=ne ni:.ləm=se kə.bɑ:b mã:.gɑ |

| Laila=Erg Neelam=Obl kebab.Nom.M ask.Perf.M.Sg | |

| ‘Laila asked Neelam for a kebab’. | |

| e. | lɛ.lɑ=ne i.mɑm=se ʊ.d̪hɑ:r li.jɑ |

| Laila=Erg Imam=Obl loan.Nom.M.Sg take.Perf.M.Sg | |

| ‘Laila borrowed from Imam’. |

Appendix B. Statistical Model

| (19) | a. | Ṁodel = lmer(DV ∼ focus_type * participants + (1 | item), data) |

| b. | Anova(Model, type = “III”) |

| 1 | |

| 2 | This is the last syllable of the sentence initial noun phrase. |

| 3 | Last syllable of the sentence medial noun phrase. |

| 4 | As a reviewer pointed out, speaker 6 exhibited upstepping and elongation on the left edge of narrowly focused nouns but did not use postfocal compression on the right edge. However, the results of the identification survey showed a high rate of correct identification of focus position (63%) for the sentences produced by her. Speaker 1 would have been a likely candidate to provide data for this survey as she used prefocal upstepping and elongation as well as postfocal compression. However, there is no data available for focus identification for this speaker. Therefore, I decided to make a trade-off and to use data from speaker 6 who used all the phonetic cues consistently to mark narrow focus as well as two of the three phrasing-related cues. |

References

- Baayen, Harold, Doug J. Davidson, and Douglas M. Bates. 2008. Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language 59: 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bates, Douglas, Martin Mächler, Ben Bolker, and Steve Walker. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, Stefan, Martine Grice, and Susanne Steindamm. 2006. Prosodic marking of focus domains–Categorical or gradient? Paper presented at Speech Prosody, Dresden, Germany, May 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, Rajesh, and Veneeta Dayal. 2007. Rightward scrambling as rightward movement. Linguistic Inquiry 38: 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2013. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer [Computer Program, v. 6.0.56]. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 20 November 2017).

- Breen, Mara, Chigusa Kurumada, Michael Wagner, Duane Watson, and Kristine Yu. 2018. Introducing prosodic variability. Laboratory Phonology: Journal of the Association for Laboratory Phonology 9: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Butt, Miriam. 1993. Object specificity and agreement in Hindi/Urdu. In Papers presented at 29th Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society: Volume 1: The Main Session. Chicago, IL, USA: The Chicago Linguistic Society, pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, Miriam, and Tracy H. King. 1996a. Focus, adjacency, and nonspecificity. Paper presented the Linguistic Society of America Annual Meeting, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 21 January 1996; Edited by Rajesh Bhatt. Available online: https://www.ling.upenn.edu/sassn/512/node16.html (accessed on 27 June 2019).

- Butt, Miriam, and Tracy H. King. 1996b. Structural topic and focus without movement. Paper presented at First LFG Conference, Grenoble, France, August 26–28; Edited by Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King. Stanford: CSLI Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, Miriam, and Tracy Holloway King. 1997. Null Elements in Discourse Structure. Written to Be Part of a Volume that Never Materialized. Available online: http://ling.uni-konstanz.de/pages/home/butt/ (accessed on 14 April 2021).

- Butt, Miriam, Farhat Jabeen, and Tina Bögel. 2016. Verb cluster internal wh-Phrases in Urdu: Prosody, syntax and semantics/pragmatics. Linguistic Analysis 40: 445–87. [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, Sasha, Emma Wollum, and Emma Kruse Va’ai. 2019. Prosodic prominence and focus: Expectation affects interpretation in Samoan and English. Language and Speech 64: 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangemi, Francesco, Martina Krüger, and Martine Grice. 2015. Listener-specific perception of speaker-specific productions in intonation. In Individual Differences in Speech Production and Perception. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, pp. 123–45. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, Arunima. 2015. Interaction between prosody and information structure: Experimental evidence from Hindi and Bangla. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Das, Kalyan, and Shakuntala Mahanta. 2019. Intonational phonology of Boro. Glossa 1: 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Elvira-García, Wendy. 2018. Extract F0 from Points. Barcelona: University of Barcelona, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Available online: http://www.wendyelvira.ga/ (accessed on 31 August 2018).

- Ernestus, Mirjam. 2012. Segmental within-speaker variation. In The Oxford Handbook of Laboratory Phonology. Edited by Abigail C. Cohn, Cécile Fougeron, Marie K. Huffman and Margaret E. L. Renwick. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Féry, Caroline. 2010. The intonation of Indian languages: An areal phenomenon. In Festschrift for Ramakant Agnihotri. Edited by Imtiaz Hasnain and Shreesh Chaudhury. Singapore: Akar Publishers, pp. 288–312. [Google Scholar]

- Féry, Caroline. 2017. Intonation and Prosodic Structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Féry, Caroline, Pramod Pandey, and Gerrit Kentner. 2016. The prosody of focus and givenness in Hindi and Indian English. Studies in Language 40: 302–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fox, John, and Sanford Weisberg. 2019. Companion to Applied Regression. [Retrieved v. 3.0-6]. Available online: https://r-forge.r-project.org/projects/car/ (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Gambhir, Vijay. 1981. Syntactic Restrictions and Discourse Functions of Word Order in Standard Hindi. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Genzel, Susanne, and Frank Kügler. 2010. The prosodic expression of contrast in Hindi. Paper presented at Speech Prosody 2010, Chicago, IL, USA, May 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Bruce, and Aditi Lahiri. 1991. Bengali intonational phonology. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 9: 47–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2012. Recursive prosodic phrasing in Japanese. In Prosody Matters: Essays in Honor of Elisabeth Selkirk. Edited by Toni Borowsky, Shigeto Kawahara, Takahito Shinya and Mariko Sugahara. London: Equinox, pp. 280–303. [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen, Farhat. 2017. Position vs. prosody: Focus realization in Urdu/Hindi. Paper presented at Phonetics and Phonology in Europe (PaPE) Conference, Köln, Germany, June 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen, Farhat. 2019a. Interpretation of LH intonation contour in Urdu/Hindi. Paper presented at International Congress of Phonetic Science, Melbourne, Australia, August 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen, Farhat. 2019b. Recursive intonation phrases in Urdu/Hindi. Paper presented at Phonetik und Phonologie (PundP) Conference, Düsseldorf, Germany, September 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen, Farhat. 2019c. Prosody and Word Order: Prominence Marking in Declaratives and Wh-Questions in Urdu/Hindi. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Konstanz, Konstanz, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen, Farhat. 2020. Focused or questioned? Intonation of polar questions and narrow focus in Urdu/Hindi. Paper presented at FASAL 10, Columbus, OH, USA, March 21–22. [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen, Farhat, and Bettina Braun. 2018. Production and perception of prosodic cues in narrow and corrective focus in Urdu/Hindi. Paper presented at Speech Prosody 2018, Poznań, Poland, June 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen, Farhat, and Elisabeth Delais-Roussarie. 2019. Towards a phonological analysis of the rising contours in Urdu/Hindi. Paper presented at ICPHS satellite Workshop Intonational Phonology of Typologically Rare or Understudied Languages, Melbourne, Australia, August 4. [Google Scholar]

- Jabeen, Farhat, and Elisabeth Delais-Roussarie. 2020. The Accentual Phrase in Urdu/Hindi: A prosodic unit at the interplay between rhythm and intonation. Paper presented at International Conference on Speech Prosody 2020, Tokyo, Japan, May 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, Elinor. 2014. The intonational phonology of Tamil. In Prosodic Typology II: The Phonology of Intonation and Phrasing. Edited by Sun-Ah Jun. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 118–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kentner, Gerrit, and Caroline Féry. 2016. A new approach to prosodic grouping. The Linguistic Review 30: 277–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Sameer ud Dowla. 2008. Intonation Phonology and Focus Prosody of Bengali. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Sameer ud Dowla. 2014. The intonational phonology of Bengladeshi Standard Bengali. In Prosodic Typology II: The Phonology of Intonation and Phrasing. Edited by Sun-Ah Jun. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 81–117. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Sameer ud Dowla. 2016. The intonation of South Asian Languages: Towards a comparative analysis. Paper presented at FASAL 6, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA, March 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Sameer ud Dowla. 2018. Building a unified intonational model for South Asian languages: InTraSAL. Paper presented at 34th South Asian Languages Analysis Roundtable, Konstanz, Germany, June 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kidwai, Ayesha. 2000. XP-Adjunction in Universal Grammar: Scrambling and Binding in Hindi-Urdu. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jiseung. 2019. Individual differences in the production of prosodic boundaries in American English. Paper presented at International Congress of Phonetic Science, Melbourne, Australia, August 5–9; Available online: https://icphs2019.org/icphs2019-fullpapers/pdf/full-paper_865.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2020).

- Krifka, Manfred. 2008. Basic notions of information structure. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 55: 243–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kügler, Frank. 2020. Post-focal compression as a prosodic cue for focus perception in Hindi. Journal of South Asian Linguistics 10: 38–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova, Alexandra, Per B. Brockhoff, and Rune H. B. Christensen. 2017. lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software 82: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ladd, D. Robert. 1986. Intonational phrasing: The case for recursive phrasing. Phonology Yearbook 3: 311–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, Aditi, and Jennifer Fitzpatrick-Cole. 1999. Emphatic clitics and focus intonation in Bengali. In Phrasal Phonology. Edited by René Kager and Wim Zonneveld. Dordrecht: Foris Publications, pp. 119–44. [Google Scholar]

- Luchkina, Tatiana, and Jennifer Cole. 2019. Perception of word-level prominence in free word order language discourse. Language and Speech 64: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchkina, Tatiana, Jennifer Cole, Preeti Jyothi, and Vandana Puri. 2015. Prosodic and structural correlates of perceived prominence in Russian and Hindi. Paper presented at 18th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Glasgow, UK, August 10–14; Available online: https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/icphs-proceedings/ICPhS2015/Papers/ICPHS0793.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2018).

- Ohala, Manjari. 1983. Aspects of Hindi Phonology. Dordrecht: Indological Publishers and Booksellers. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, Iris, and Elsi Kaiser. 2015. Individual differences in the prosodic encoding of informativity. In Individual Differences in Speech Production and Perception. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, pp. 147–88. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, Umesh, Gerrit Kentner, Anja Gollrad, Frank Kügler, Caroline Féry, and Shravan Vasishth. 2008. Focus, word order and intonation in Hindi. Journal of South Asian Linguistics 1: 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Peppé, Sue, Jane Maxim, and Bill Wells. 2000. Prosodic variation in Southern British English. Language and Speech 43: 309–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, Vandana. 2013. Intonation in Indian English and Hindi Late and Simultaneous Bilinguals. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2014. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing [v. 3.6.1]. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rooth, Mats. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 75–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuppler, Barbara, and Bogdan Ludusan. 2020. An analysis of prosodic boundary detection in German and Austrian German read speech. Paper presented at International Conference on Speech Prosody 2020, Tokyo, Japan, May 23–26. [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, Elizabeth. 1984. Phonology and Syntax: The Relation between Sound and Structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, Elizabeth. 1986. On derived domains in sentence phonology. Phonology Yearbook 3: 371–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkirk, Elizabeth. 2011. The syntax-phonology interface. In The Handbook of Phonological Theory. Edited by John Goldsmith, Jason Riggle and Alan Yu. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 435–84. [Google Scholar]

- Stoet, Gijsbert. 2010. PsyToolkit—A software package for programming psychological experiments using Linux. Behavior Research Methods 3: 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoet, Gijsbert. 2017. PsyToolkit: A novel web-based method for running online questionnaires and reaction-time experiments. Teaching of Psychology 44: 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urooj, Saba, Benazir Mumtaz, and Sarmad Hussain. 2019. Urdu intonation. Journal of South Asian Linguistics 10: 2–22. [Google Scholar]

- Venables, William, and Brian Ripley. 2002. Modern Applied Statistics with S. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, Hadley. 2016. Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

| Role | Initial | Medial | Im. Preverbal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | 87% | 13% | - |

| Indirect object | 9% | 91% | - |

| Direct object | 29% | 71% | - |

| Null-marked object | - | - | 100% |

| Locative | - | 8% | 92% |

| Total | 35% | 33% | 32% |

| Role | Initial | Medial | Im. Preverbal | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scrambled | 16% | 17% | - | 11% |

| in situ | 84% | 83% | 100% | 89% |

| Phonetic Cues | Position | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Higher F0 peak | Medial | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Preverbal | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Initial | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Wider F0 range | Medial | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||||

| Preverbal | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Initial | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Longer duration | Medial | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Preverbal | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Target Production | Identified | Label |

|---|---|---|

| Initial narrow focus | Medial narrow focus | Incorrect |

| Initial narrow focus | Initial narrow focus | Correct |

| Wide focus | Preverbal narrow focus | Incorrect |

| Speaker | Incorrect | Correct |

|---|---|---|

| 02 | 76% | 24% |

| 06 | 49% | 51% |

| Incorrect | Correct |

|---|---|

| 37% | 63% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jabeen, F. Word Order, Intonation, and Prosodic Phrasing: Individual Differences in the Production and Identification of Narrow and Wide Focus in Urdu. Languages 2022, 7, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020103

Jabeen F. Word Order, Intonation, and Prosodic Phrasing: Individual Differences in the Production and Identification of Narrow and Wide Focus in Urdu. Languages. 2022; 7(2):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020103

Chicago/Turabian StyleJabeen, Farhat. 2022. "Word Order, Intonation, and Prosodic Phrasing: Individual Differences in the Production and Identification of Narrow and Wide Focus in Urdu" Languages 7, no. 2: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020103

APA StyleJabeen, F. (2022). Word Order, Intonation, and Prosodic Phrasing: Individual Differences in the Production and Identification of Narrow and Wide Focus in Urdu. Languages, 7(2), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020103