Abstract

Previous research points to a major role of L3 proficiency in L3 acquisition whereas language dominance and cognate status in bilinguals remain under-researched. The aim of this paper was to investigate the role of L3 proficiency, language dominance and cognate status on the production of the L3 Polish lateral. The dominance of Ukrainian over Russian was assessed with the use of an adapted version of the Bilingual Language Profile. Proficiency in Polish was gauged by means of a standardized placement test. The stimuli included tokens requiring a clear realization with the Polish lateral divided into four conditions depending on its production in cognates from Ukrainian/Russian. The results revealed that higher L3 proficiency was associated with an increase in target-like lateral productions in L3 Polish. Language dominance accounted for the less typical lateral pronunciations with a tendency to produce more labiovelar approximants by more Ukrainian-dominant speakers and fewer palatalized laterals by more balanced Ukrainian–Russian speakers. A similar lateral pronunciation in the cognates of both background languages influenced lateral production in the L3. Different lateral pronunciations in the cognates of the background languages had an effect on the more Ukrainian-dominant speakers who had a greater tendency to rely on the L1 Ukrainian pronunciation while producing L3 Polish.

1. Introduction

The paper presents a study on L3 Polish phonological ability of unbalanced Ukrainian-Russian bilinguals. Specifically, it examines the role of L3 proficiency and language dominance in the bilinguals’ production of L3 Polish lateral. It also examines cognateness as a factor that has received little attention in L3 phonology research to date. The significance of the study, thus, lies in investigating an interplay between phonology and lexicon in the acquisition of an under-represented combination of languages: L1 Ukrainian/L2 Russian and L3 Polish.

One aim of the study was to investigate L3 proficiency. The bilingual participants claimed equal proficiency in their L1 and L2 but reported different levels of proficiency in their L3, which made it possible to investigate L3 proficiency as a conditioning factor. Another aim of the study was to analyze the role of language dominance by looking into the different dominance patterns in the two background languages of the speakers. Finally, by using cognate and non-cognate vocabulary in the study, the effect of L1 and L2 lexical processing on phonological cross-linguistic influence (CLI) in the L3 was examined. The results lead to a better understanding of the role of L3 proficiency, language dominance and cognate status between L1-L2 and L3 vocabulary on the production of the lateral in the L3.

Target language proficiency has been identified as one of the most important factors conditioning CLI in L3 acquisition (Ringbom 1987; Williams and Hammarberg 1998). It has been noted that L2 influence in the L3 can be particularly prominent in the initial stages of L3 phonological acquisition but that it decreases as L3 proficiency increases (e.g., Hammarberg 2001; Wrembel 2010). The main assumption is that, with increasing L3 proficiency, there should be less CLI from either L1 or L2 and a greater reliance on target L3 structures (e.g., Williams and Hammarberg 1998). An interesting issue that is hitherto unclear is at what L3 proficiency level CLI from the background language decreases in favor of a greater reliance on L3 target-like pronunciation. The turning point at which L3 target-like pronunciation becomes predominant in the output is of interest for the current study.

The levels of proficiency in the L2 and L3 may also interact and shape L3 together (Cal and Sypiańska 2021; Sypiańska and Cal 2020). However, this typically happens when the speakers live in an L1 country and learn both L2 and L3 in a formal setting (e.g., Cal and Sypiańska 2021). In this case, the level of proficiency in L1 is comparable across the speakers and should not be treated as a potential factor. On the other hand, bilinguals who use both their languages on a daily basis will typically possess a dominant and a subordinate language rather than two languages with equal command (Grosjean 1998). Dominance in unbalanced bilinguals has been associated with language proficiency (e.g., Birdsong 2006) or language use (Pavlenko 2004). Proficiency cannot be treated synonymously with dominance as “one can be dominant in a language without being highly proficient in that language” (Gertken et al. 2014, p. 209). Similarly, greater frequency of use of a given language does not imply more dominance in said language. The differences in command contribute to variations in production (e.g., Guion et al. 2000). Thus, if both L1 and L2 are used in the L1 country, as is usually the case with early bilinguals, the differences in both languages’ use and/or proficiency may influence the L3 in different ways. Lloyd-Smith et al. (2017) showed that perceived foreign accent in L3 English of L1 German with Turkish as the heritage language originated mostly from L1 but a higher proficiency in L2 Turkish led to a more ambiguous sounding accent in L3. Similarly, Gabriel and Rusca-Ruths (2014) found CLI stemming from the L1 in L1 Turkish speakers of heritage German learning L3 Spanish. The higher frequency of use in Turkish augmented the tendency. Lloyd-Smith (2021) examined Italian–German bilinguals acquiring L3 English and found mostly L1 German influence in a general foreign accent in L3. However, there was an effect of dominance patterns on the minor Italian source of influence. Tsui and Tong (2019) found that unbalanced but not balanced bilinguals experience short-term phonetic convergence when shifting from one language to the other. Finally, in a study on active bilinguals by Gallardo del Puerto (2007), bilingual proficiency was not predictive for L3 perceptual ability in either balanced or unbalanced early Basque–Spanish bilinguals. In the current study, dominance is conceptualized as a global construct involving both proficiency and use but also language history and attitudes. The measurement of the construct of dominance is carried out with the use of the Bilingual Language Profile (Birdsong et al. 2012). Language use includes percentage of use of the given language with family, friends and at school/work and questions on counting and talking to yourself in a given language. Language proficiency is self-reported and refers to each language skill: reading, writing, speaking and listening (more information on the Bilingual Language Profile in Section 2).

Apart from target language proficiency, another factor that has been theorized to importantly condition CLI in L3 acquisition is the similarity between the languages in contact. This may concern the learner’s perceived similarity between languages and/or structures, i.e., psychotypology (Kellerman 1983) and/or actual genetic and structural relationships (for further discussion in the context of L3 phonological acquisition, see (Nelson et al. 2021)). In the current study, all languages (Ukrainian, Russian and Polish) are related within the Slavic family of languages and, thus, can be expected to share a large number of cognate words. Cognates are defined as words that overlap in their semantic, phonological and orthographic form (Janyan and Hristova 2007). It was of interest in this study to investigate the pronunciation of selected vocabulary items in L3 that are cognates (or not) with L1 and L2 equivalents in order to determine any cognate effects in L3 phonological learning. Research into L2 vocabulary learning has demonstrated that cognates are processed faster than non-cognates (Bosma et al. 2019), leading to the so-called cognate facilitation effect (Costa et al. 2000). Research on lexical processing has further shown that cognateness can affect phonological performance in that cognates are more prone to non-facilitative CLI compared to non-cognates (e.g., Lemhöfer and Dijkstra 2004). Mora and Nadeu (2012) found that Spanish–Catalan bilinguals produced a higher Catalan mid front vowel (with CLI from the higher Spanish mid front vowel) in Spanish–Catalan cognates than in non-cognates. Amengual (2012) showed that Spanish–English bilinguals increased VOT for /t/ in Spanish words with English cognates than those without English cognates.

Cognate status has not been widely researched in L3 acquisition. However, there are some reports of a special status of cognates in L3 processing. In the context of L3 acquisition, similarly, Bouchhioua (2016) found a major tendency to produce a non-target nasalized vowel in L3 English when the word was an English–French cognate with a nasalized vowel in the French equivalent. No such tendency was found in non-related vocabulary. Amengual (2021) reported a cognate effect in a group of L1 Spanish, L2 English and L3 Japanese speakers that manifested in a degree of phonetic convergence in VOT. Moreover, Bartolotti and Marian (2018) found an effect of cognate status while teaching an artificial language to Spanish–English bilinguals. They report that although cognate vocabulary learnt faster, it suffers a phonological disadvantage as its pronunciation is less accurate at least at the beginning of the learning process. Additionally, the similarity of the L3 word to both background languages is more costly than its similarity to one background language. They conclude that two phonological representations have to be activated in the former case, which is more difficult than the activation of one phonological representation.

The paper is structured in the following manner. First, the research methodology is described including the battery of tests administered to the participants, the stimulus and procedure used for data elicitation and the hypotheses developed to find answers for the research questions. Secondly, the statistical analysis of the results is presented followed by a discussion in reference to the current literature.

2. Materials and Methods

The study focuses on the production of the lateral in L3 Polish by bilingual Ukrainian–Russian speakers. The lateral is clear [l] in Polish and palatalized only in the context of a high front vowel or a palatal approximant. The non-palatalized lateral is velarized in Russian (Cubberley 2002) and Ukrainian (Shevelov 2002) with no clear lateral variants. A velarized [ɫ] and a palatalized [lʲ] lateral may appear in Ukrainian and Russian without the need for a velar or palatal context.

The production of the lateral in L3 Polish was elicited from Ukrainian–Russian bilinguals with a task consisting in reading out loud words in isolation. The stimuli (Appendix A Table A1) included tokens (n = 418) of Polish words with the lateral divided into four conditions depending on its realization in Ukrainian/Russian cognates: (1) The VEL/VEL condition included Polish words for which its cognates in both Ukrainian and Russian contained a velarized lateral (n = 126), e.g., Polish lawa (Ukrainian: лава/Russian: лава) ‘lava’. (2) The PAL/PAL condition included Polish words for which its cognates in both Ukrainian and Russian contained a palatalized lateral (n = 63), e.g., Polish Polak (пoляк/пoляк) ‘Pole’. (3) The VEL/PAL condition comprised Polish words for which its Ukrainian cognates had a velarized lateral, and Russian cognates had a palatalized lateral (n = 105), e.g., Polish bilet (билет/билет) ‘ticket’. (4) The NoCog condition included Polish words with no cognates in Ukrainian or Russian (n = 124), e.g., Polish sklep (крамниця/магазин) ‘shop’. Contexts that would require palatalization in standard Polish were excluded. The criteria for coding words into the particular conditions were based on phonology and semantics but not orthography due to the difference in alphabets used for the three languages. Moreover, the cognates had to include a lateral. The productions were coded into four realizations (clear, velarized, palatalized and a labiovelar approximant) by means of an auditory analysis aided by the formant tracker in Praat (Boersma and Weenink 2021).

The participants were asked to read Polish words as they appeared on Powerpoint slides. The words were presented in isolation, and the recording was performed in one sitting. The recordings were carried out in a quiet room with the use of a RØDE N1 condenser microphone connected to a computer by means of a Focusrite Scarlett 2i2 2Gen 365 audio interface at the Pomeranian University in Słupsk. In another sitting, recordings of Russian and Ukrainian cognates from VEL/VEL, PAL/PAL and VEL/PAL categories were carried out, and the production of the lateral was analyzed auditorily with the help of the formant tracker in PRAAT. The data showed that all instances of the lateral were pronounced by the participants in accordance with the standard in both languages.

The participants comprised 21 native Ukrainians who attended the Pomeranian Academy in Słupsk, Poland, and had been residing in Poland for 4 to 7 months prior to recording. In order to select a homogenous group with regard to language background, a number of tests were employed. First and foremost, these included a biodata questionnaire on the basis of which two males and 19 females were chosen for recordings. All participants were from the western parts of Ukraine with uniform dialectal background (south-western dialects of Ukrainian). All of them had Ukrainian as a native language, and a vast majority claimed to use only Ukrainian at home. All participants reported exposure to Russian at an age of onset between 0 and 3 years of age, making them early Ukrainian–Russian bilinguals. Russian was either used at home, by extended family or in day care and/or kindergarten. Both Russian and Ukrainian use were reported at school and other institutions (Appendix A Table A2). In order to establish their bilingual language dominance in Ukrainian and Russian, an adapted version of the Bilingual Language Profile (BLP) (Birdsong et al. 2012) was employed. Only Ukrainian-dominant bilinguals were selected for participation in the study. The participants presented differences in the extent of dominance of Ukrainian over Russian ranging from −156.00 to −32.96 where 0 stands for a balanced bilingual, negative values stand for Ukrainian-dominance and positive values stand for Russian-dominance (Appendix A Table A3). The process of participant selection was challenging because, with over 100 potential candidates, only two were Russian-dominant and had to be excluded due to unequal samples. Others were excluded from the study because of insufficient Polish language proficiency (lower than A2), different dialectal background, lengthy stays in other Russian-speaking countries apart from Ukraine, parents with other Slavic language backgrounds, residence in Poland longer than 7 months (which translates to one semester at the Polish university including summer which they also spent in Poland), and age of onset of Russian at more than three years old (so as to include only early bilinguals).

The Bilingual Language Profile assesses language dominance with the use of four modules: Language History (6 questions each worth between 0 and 20), Language Use (5 questions each worth between 0 and 10), Language Proficiency (4 questions each worth between 0 and 6) and Language Attitudes (4 questions each worth between 0 and 6). The questions in each module have different weights with Language History the smallest weight and Language Proficiency and Language Attitudes the greatest weight. The final score is obtained by multiplying each question by the weight and then summing the scores for all questions. The mean scores for each module, thus, suggest particular dominance of Ukrainian over Russian in Language Use followed closely by Language Attitudes and Language History. Scores for Language Proficiency, on the other hand, point to similar self-reported proficiency in the two languages. The participants reported knowledge of three foreign languages: Polish, English and Russian1 (Appendix A Table A4). Proficiency in Polish was assessed by means of a standardized Polish placement test (Burkat et al. 2008) with levels ranging from A2 to A2+ to B1. Proficiency in Russian and English was self-reported indicating nearly native-like levels in Russian (based on the results of the Bilingual Language Profile) and intermediate to upper–intermediate (from A2+ to B1) levels of English. Prior to arrival, they attended a one-month intensive Polish course and they continued Polish classes (90 min) twice a week during their stay. Since they were students at a Polish university, their entire instruction with up to 20 h of classes (90 min per class) weekly was also carried out in Polish. On the other hand, the age of onset of their English was earlier than Polish (M = 9.24; SD = 1.4). The majority had private tutoring in English in Ukraine and continued with English classes once a week at the Polish university. Although based on chronology of onset, it is English and not Polish, which is language number three in the repertoire; the analysis of the production of the lateral in English or its influence on the Polish lateral is beyond the scope of the paper. Polish is analyzed as an L3 as it is assumed that the processes governing CLI in L3 and Ln are essentially the same (De Angelis 2007; Hammarberg 2010, 2018). Including Russian among the foreign languages, while claiming equal proficiency in the two languages, suggests that the speakers make a differentiation between the languages of their daily use at least in terms of the affective factor. The different approaches to the languages are confirmed by the results of the Language Attitudes module from BLP, which received the lowest scores for the Russian part. The Language Attitudes module includes questions on the degree to which the bilingual feels comfortable speaking each language (not referring to proficiency), the identification with each culture of the bilingual, the importance of using each of the two languages at a native speaker level, and the importance of being perceived as a native speaker of each of the languages by other speakers. The scores indicate that the speakers are far more comfortable using Ukrainian than Russian. They tend to identify more with Ukrainian culture rather than with Russian culture. They also place more importance on speaking Ukrainian at a native level and being perceived as a Ukrainian native speaker over being perceived as a native speaker of Russian.

The aim of the study was to investigate the effect of L3 proficiency and L1/L2 cognate status on L3 phonology of unbalanced bilinguals. Previous research points towards a propensity for the L2 as a source of cross-linguistic influence with low L3 proficiency that shifts towards the L1 as a source of CLI with greater L3 proficiency (e.g., Gut 2010; Tremblay 2007; Wrembel 2010) and/or indeed the target L3 realization (e.g., Williams and Hammarberg 1998). This study aimed to establish at what proficiency level L3 target-like pronunciation becomes predominant in the output. Another aim was to look into how the production of the lateral in cognate vocabulary from the background languages influences L3 production. For this purpose, the words for production were coded into the four categories described above. A final aim was to verify how different degrees of dominance in one background language over the other influences the choice of background language to rely on when producing the L3 word in the particular condition. The following research questions were formulated:

- Is the production of the lateral in L3 Polish influenced by the level of proficiency in the L3? If so, at what level of proficiency in L3 Polish does target-like pronunciation of the lateral become predominant?

- Is the production of the lateral in L3 Polish influenced by the pronunciation of the lateral in cognate vocabulary in background languages (Ukrainian and Russian)?

- How does the degree of dominance in Ukrainian over Russian influence the production of the L3 Polish lateral? How does the degree of dominance affect the lateral in words that are/are not cognates across the speakers’ three languages?

With a greater level of proficiency in L3 Polish, there should be a greater number of realizations with a clear lateral, which is the target pronunciation of the lateral in Polish (Hypothesis 1).

The effect of lateral production in cognate vocabulary in background languages should be visible in the choice of L3 production where there are two options for cognate vocabulary (condition VEL/PAL) with a tendency to produce a velarized lateral because the speakers are all Ukrainian-dominant and should rely on their Ukrainian and not Russian cognate pronunciation. In the NoCog condition, without the phonological disadvantage stemming from cognate status, there should be a greater propensity to produce the target-like lateral variant. There should be no effects of the condition in VEL/VEL and PAL/PAL where Ukrainian and Russian cognates have the same pronunciation (velarized and palatalized, respectively) (Hypothesis 2).

Dominance should not influence L3 Polish in terms of palatalization or velarization of the L3 lateral because both Ukrainian and Russian possess the palatalized and the velarized laterals. The influence of dominance may, however, be visible if the L3 lateral is pronounced as a labiovelar approximant (Hypothesis 3). As Ukrainian possesses the labiovelar approximant and Russian does not, pronouncing the L3 Polish lateral as a labiovelar approximant will suggest CLI from Ukrainian.

On the other hand, dominance in Ukrainian over Russian should also interact with the condition (Hypothesis 4). More Ukrainian-dominant speakers should be more likely to produce a velarized lateral condition VEL/PAL. Dominance should not matter in conditions VEL/VEL, PAL/PAL and NoCog in which both background cognates behave in the same way, or there are no cognates.

3. Results

The results show that the most frequent production was a velarized lateral [ɫ] (43%) followed by a clear [l] (38%), a palatalized [lj] (14%) and a labiovelar approximant [w] (5%)2. To answer the formulated research questions, a multinomial logistic regression was run with the level of proficiency, condition and dominance as fixed effects and dominance*condition as an interaction effect. The dependent variable is lateral realization with four categories: clear lateral, velarized lateral, palatalized lateral and labiovelar approximant. Nested model comparisons were used to compare the changes to the model. Based on the likelihood ratio tests the fitted model was statistically significant (χ2 = 45.138, p < 0.000). The results revealed a statistically significant effect of level of proficiency (χ2 = 29.373, p < 0.000) and smaller effects of condition (χ2 = 13.123, p = 0.032) and degree of dominance (χ2 = 11.240, p = 0.045). The interaction effect of dominance*condition was significant to a lesser extent (χ2 = 15.890, p = 0.04). Multiple comparisons tests were based on deviation.

3.1. Level of Proficiency

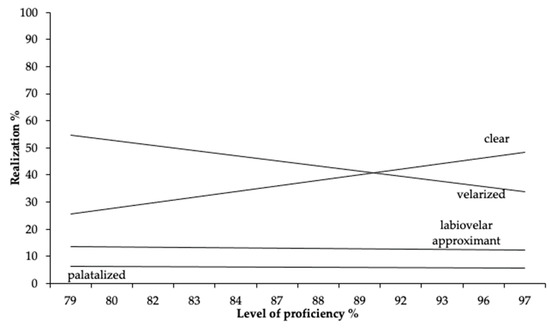

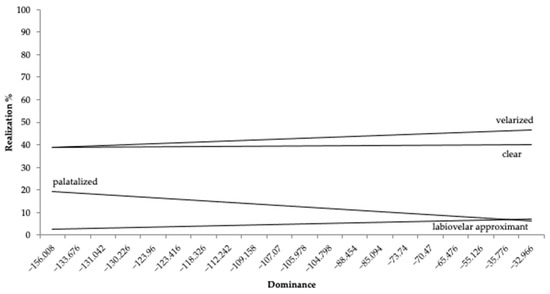

The first research question pertained to the influence of L3 level of proficiency on the production of the L3 lateral. The results showed that level of proficiency in L3 Polish had the greatest influence on the way the speakers produced the lateral in L3 Polish (Figure 1). With greater level of proficiency, there were more clear laterals (p < 0.001) and fewer velarized realizations (p < 0.001). The percentage of the labiovelar approximant and palatalized realizations remained unaffected by level of proficiency in the L3 (p = 0.563, p = 0.632, respectively). The second part of the first research question referred to the L3 level of proficiency at which target-like pronunciations become predominant in the L3 output. The results show that target-like pronunciation of the lateral in the L3 became predominant among participants with a 90% score in the Polish placement test, which corresponds to B1 level of proficiency in L3 Polish.

Figure 1.

The effect of level of proficiency on the realization of the L3 Polish lateral (in percentages).

3.2. Condition

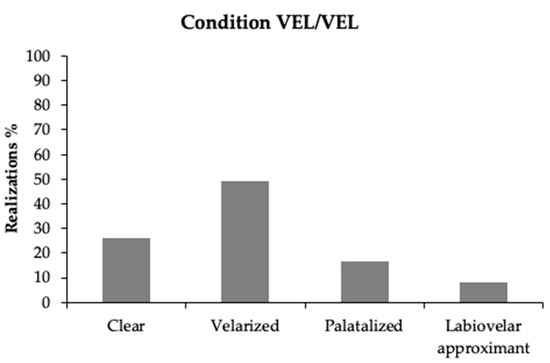

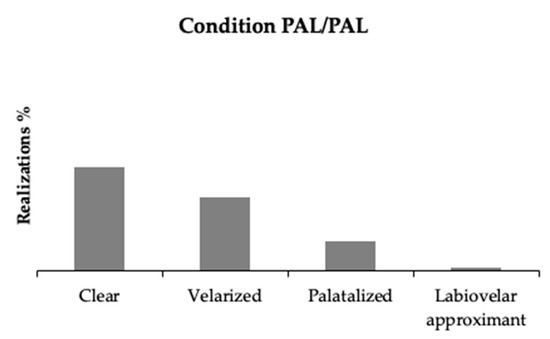

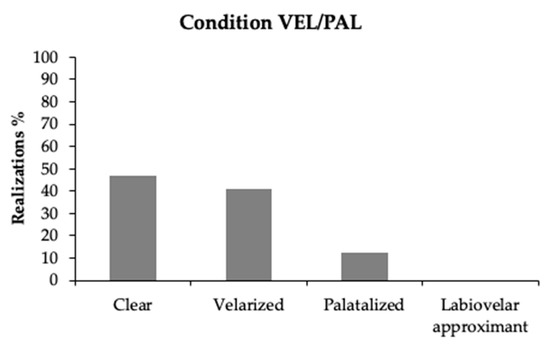

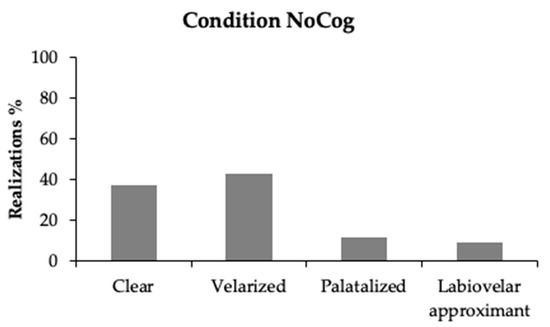

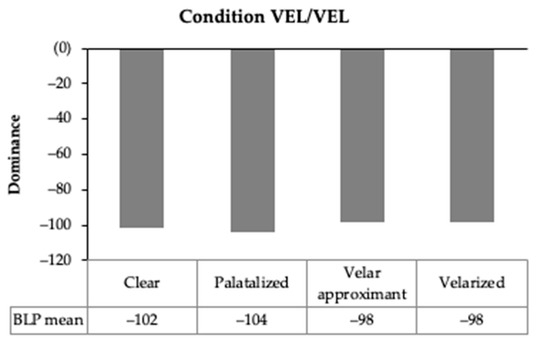

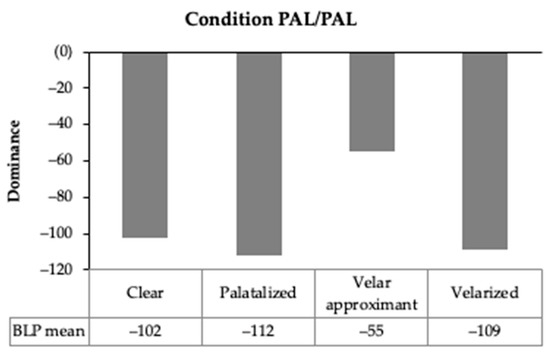

The second research question referred to the way that the L3 Polish lateral was influenced by the pronunciation of the lateral in cognate vocabulary in background languages (Ukrainian and Russian). In condition VEL/VEL, in which both background languages apply a velarized lateral in the cognate items, most participants’ L3 productions were also velarized (Figure 2). In condition PAL/PAL, with both background language cognates having a palatalized lateral, the tendency was to produce a clear lateral followed by a velarized lateral (Figure 3). The same tendency was visible in condition VEL/PAL in which the Ukrainian cognate had a velarized and the Russian cognate had a palatalized lateral (Figure 4). When no cognates were available in the background languages, as in condition NoCog, clear and velarized realizations were the most common (Figure 5). The difference between the clear and velarized lateral reached statistical significance in condition VEL/VEL and PAL/PAL (p > 0.001, p > 0.001, respectively), but it did not reach statistical significance in conditions VEL/PAL and NoCog (p = 0.121, p = 0.342, respectively).

Figure 2.

The production of the L3 lateral in condition VEL/VEL.

Figure 3.

The production of the L3 lateral in condition PAL/PAL.

Figure 4.

The production of the L3 lateral in condition VEL/PAL.

Figure 5.

The production of the L3 lateral in condition NoCog.

3.3. Language Dominance

The third research question addressed the influence of dominance in Ukrainian over Russian on the production of the L3 Polish lateral. The results indicated that language dominance produced a small significant result, revealing influence on the type of lateral produced by the speakers (Figure 6). The effect was visible in a smaller number of palatalized laterals among speakers that were more balanced (closer to 0 on the dominance scale) (p < 0.01). It was also manifested in a greater number of the labiovelar approximant (p = 0.045) among the more balanced speakers. The numbers for velarized and clear laterals were not affected by language dominance (p = 0.455, p = 0.998, respectively).

Figure 6.

The effect of dominance on the realization of the lateral.

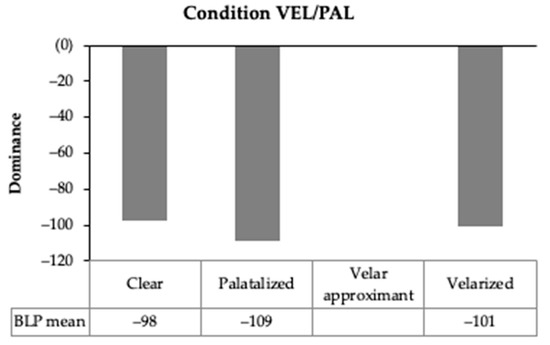

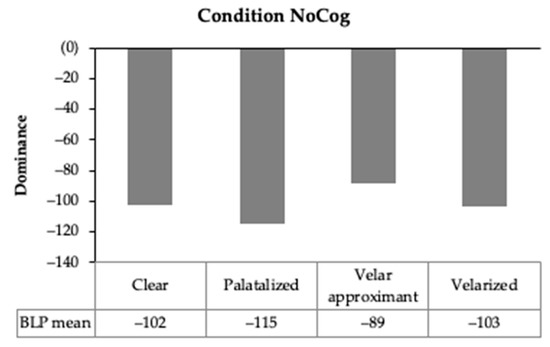

3.4. Interaction of Language Dominance and Condition

The second part of the third research question referred to the interaction of language and dominance. The analysis demonstrated that the interaction was not visible in condition VEL/VEL (Figure 7). In condition PAL/PAL (Figure 8), the labiovelar approximant was chosen by the more balanced speakers than the other realizations of the lateral. In condition VEL/PAL (Figure 9), more Ukrainian-dominant speakers (with lower BLP mean scores) produced a velarized lateral rather than a palatal or clear lateral. In condition NoCog (Figure 10), more Ukrainian-dominant speakers were more likely to produce a palatalized lateral than a clear or velarized lateral. Finally, in the last condition, the labiovelar approximant was produced by more balanced speakers than the other realizations of the lateral.

Figure 7.

The interaction effect of condition VEL/VEL and language dominance.

Figure 8.

The interaction effect of condition PAL/PAL and language dominance.

Figure 9.

The interaction effect of condition VEL/PAL and language dominance.

Figure 10.

The interaction effect of condition NoCog and language dominance.

4. Discussion

The results showed that the two most common ways to pronounce the L3 Polish lateral by unbalanced Ukrainian–Russian bilinguals included a velarized followed by a clear lateral. There were two other minor pronunciations, i.e., a palatalized lateral and a labiovelar approximant instead of the lateral. The velarized lateral did not reflect a particular language in the speakers’ repertoire as both Ukrainian and Russian possess a velarized lateral. One reason why the velarized and not the palatalized lateral was the most common pronunciation may lie in the speakers’ perception of similarity of the target sound in their three languages. According to Flege’s Speech Learning Model (Flege 1995), learners who perceptually assimilate the L2 (and by extension the L3) sound, and a similar counterpart in their background language(s) will show CLI from that language in the production of the target sound (e.g., Sypiańska and Constantin 2021). The speakers in the current study may have perceived the L3 Polish lateral as a highly similar sound to the velarized but not to the palatalized lateral; as a consequence, they produced the L3 Polish lateral with velarization and not palatalization. Future research needs to test this perception-based explanation by developing and applying suitable measures of the perceived cross-linguistic similarity in L3 learners/speakers.

Another reason for a prevalence of the velarized lateral in the results may be the influence from the speakers’ English. If they produce the English lateral with velarization, then it is another language in their linguistic repertoire with a velarized lateral. Being the highly predominant variety of lateral in the linguistic repertoire may have contributed to the fact that the velarized lateral is the most common variety of lateral in their L3 Polish. This source of CLI, however, would need to be verified by an analysis of lateral production in the speakers’ English.

The statistical tests showed that the L3 level of proficiency exerted the strongest influence on the production of the lateral in L3. The impact of proficiency consisted in a greater percentage of clear target-like pronunciations and a lower percentage of velarized pronunciations among the participants with a higher level of proficiency in L3, confirming the first hypothesis. The numbers for the other two pronunciations (palatalized and labiovelar approximant) remained unaffected by an increasing level of proficiency in L3. The results demonstrated that learning to pronounce the Polish lateral by the Ukrainian–Russian speakers consisted in suppressing the most common non-target realization that is velarization of the lateral. Target-like pronunciation became predominant among speakers who reached a B1 general level of proficiency in the L3. Although this study is cross-sectional in nature, the results it offers are not necessarily in contrast with recent findings on L3 phonological development as a non-linear process (e.g., Kopečkova et al. 2019). The current data show that, most likely at a B1 level of L3 proficiency, the L3 target-like pronunciation becomes predominant in the output of the speakers; however, there still is variation in the speakers’ pronunciation reflective of CLI from background languages. The claim that there may be a threshold after which L3 target-like production is predominant in L3 does not preclude further development of L3 forms including periods of regression at higher levels of L3 proficiency.

The results on proficiency are in line with previous reports (e.g., Hammarberg and Hammarberg 2005; Wrembel 2010) in that L3 proficiency plays a decisive role in shaping L3 production. An important finding was that the L3 target pronunciation became predominant in the output at a B1 level in L3 Polish. This was the threshold at which the majority of instances were pronounced with a clear lateral regardless of other factors and influences. Previous research (e.g., Williams and Hammarberg 1998) points to a possible level of L3 proficiency at which CLI from the background languages starts to decrease and a greater reliance on L3 target-like pronunciation begins. The results of the current study provide evidence that the B1 level of general proficiency in the L3 may constitute such a turning point.

The investigation of the influence of the lateral production in cognate vocabulary in background languages (Ukrainian and Russian) demonstrated that the two main variants (clear and velarized lateral) were the ones responsible for the effect of condition in the data. Hypothesis 2 regarding the condition was not fully supported by the data. Differences in lateral realization were visible only in the first two conditions: VEL/VEL and PAL/PAL. In condition VEL/VEL, in which both background languages had a velarized lateral in the cognate, there was a greater tendency to produce a velarized lateral in L3 Polish. In the second condition in which both background languages had a palatalized lateral in the cognate, the majority of instances were produced with a clear lateral. These results point to a booster effect that background languages may have on the developing L3. When both languages had a velarized lateral in the cognate, the tendency to produce the velarized variant in L3 was stronger than when only one (or no) background language cognate had the velarized variant. This indicates that CLI from two background languages may have a greater impact on L3 than CLI from one language only. This tendency was not present in condition PAL/PAL with both background language cognates having a palatalized lateral because the palatalized variant was only a minor pronunciation in the data. In condition VEL/PAL in which both cognates had a different lateral, the velarized lateral was not a more frequent choice. Moreover, in condition NoCog, non-cognate vocabulary did not trigger more correct pronunciations than cognate vocabulary. This finding is contrary to previous reports on cognate status in which strong tendencies for CLI from background languages were found in cognates (Bouchhioua 2016; Bartolotti and Marian 2018). The current study did not provide evidence of a phonological disadvantage in cognate vocabulary as the accuracy levels were not affected by cognate status. The reason for this result may be the general similarity of the three languages (Polish–Russian–Ukrainian) of the linguistic repertoire to the speakers. In languages that are so closely related and similar, the cognate vocabulary may not stand out as being similar (or more similar than other types of vocabulary) for the speakers.

Language dominance was found to influence only the minor realizations of the lateral, the palatalized lateral and the labiovelar approximant. More balanced speakers produced fewer palatalized laterals, whereas more Ukrainian-dominant speakers produced more labiovelar approximants, confirming Hypothesis 3. The number of velarized and clear laterals was not affected by language dominance. These results also suggest that the minor pronunciations were not idiosyncratic but resulted from a particular dominance distribution in bilinguals’ languages.

The interaction effect of language dominance and condition further showed how the choice of lateral realization took place. As predicted in Hypothesis 4, more Ukrainian-dominant speakers were more likely to produce a velarized lateral in L3 Polish when the Ukrainian cognate had a velarized lateral (in condition VEL/PAL). Dominance was also responsible for the difference in the productions in condition NoCog. With no background language cognate to rely on, more Ukrainian-dominant speakers preferred a palatalized lateral and more balanced bilinguals preferred a velarized lateral.

The results on language dominance confirm and extend previous reports in the literature on the significance of background language use. Similarly to Kopečkova (2016), the specific dominance in the languages was not of crucial importance in the data as it was not responsible for the accuracy of the production of the lateral. However, language dominance was found to influence the minor realization of the lateral. This result is similar to Lloyd-Smith (2021) who found that dominance patterns were responsible for the minor Italian source of influence in their L3 data. It can be concluded that language dominance in unbalanced bilinguals may not be the main factor, but it can affect the variation of pronunciations present in the L3. Interestingly, dominance interacted with cognate status as it increased the likelihood of pronouncing a velarized lateral in L3 by the more Ukrainian-dominant individual when there was a velarized lateral in the Ukrainian cognate. This tendency was contrary to a general propensity of the more Ukrainian-dominant individual to choose a palatalized rather than a velarized lateral.

In summary, the study informs the area of L3 acquisition in a number of aspects. First of all, it contributes to a better understanding of how chosen factors shape CLI from the background languages to the L3. The results on the factor of L3 proficiency lend support to the main assumption in the L3 acquisition literature regarding the workings of L3 proficiency, namely that the increase in L3 proficiency is linked with more target-like productions in L3. An important finding is the establishing of an L3 proficiency threshold at which CLI from the background languages starts to decrease and a greater reliance on L3 target-like pronunciation begins. This result supplements previous mentions of such a threshold in L3 acquisition literature by providing a concrete point on the proficiency scale. It may also improve future study designs that aim to compare CLI in initial stages of L3 acquisition and CLI present later on in the L3 acquisition process. However, future investigations should explore this issue further across different structures, language domains and language repertoires. The present findings on the factor of dominance confirm previous L3 acquisition work that suggests that language dominance may not be of key importance for shaping CLI to the L3. It may, however, explain some of the less significant CLI outcomes such as the labiovelar approximant in the current study. The study also shows evidence of a booster effect that consists in stronger CLI in L3 when two of the background languages share a particular source structure. When it comes to the factor of cognate status, the current study has not provided support for a phonological disadvantage that multilinguals may experience when producing words that are cognates with one or more of the background languages. This finding is a promising aspect of CLI in multilinguals that could suggest greater metaphonological awareness of multilinguals, which allow them to suppress non-facilitative CLI when faced with L3 words of similar structures to their background languages. On the other hand, the result may also be due to the particular language repertoire in which the languages are overall quite similar so that cognates do not stand out as being more similar than other vocabulary. The replication of the study should then be carried out in a language repertoire with languages that are structurally much different but share cognates.

Secondly, the study broadens the scope of L3 acquisition. It incorporates underrepresented languages and linguistic profiles. It broadens the spectrum of linguistic data analyzed in L3 acquisition by focusing on a hitherto unstudied aspect of L3 phonology that is the lateral.

Lastly, the study shows how Ukrainian–Russian bilinguals produce the lateral in their L3 Polish. Although the study did not aim to research sources of CLI in L3 lateral production, it did show some tendencies for source of CLI in the L3. Greater dominance in Ukrainian increased the likelihood of producing the labiovelar approximant, which is evidence of CLI from the L1 Ukrainian. Moreover, L1 was the most frequent choice of CLI source among Ukrainian-dominant speakers when the L1-L2 cognates of the L3 piece of vocabulary had two different lateral realizations.

A shortcoming of the study is not including the effect of the speakers’ English in the analysis, which was performed due to an insufficient participant sample. Since English also has a velarized lateral (or a clear and a velarized one depending on the variety), it would be interesting to see how it is produced and which factors contribute to its realization. More importantly, it would be vital to see whether the speakers’ production of the English lateral impacts their L3 Polish lateral. Another drawback is the number of participants and delimiting the dominance factor to Ukrainian-dominant speakers only. However, including a sufficiently large sample of Russian-dominant speakers would be a difficult, if not impossible, task as they will most likely be representatives of different Ukrainian dialects from regions that are currently war-stricken.

5. Conclusions

The results of present study show that L3 proficiency plays an essential role in the production of L3 phonology. Target L3 pronunciation seems to become predominant in L3 production at B1 level of general proficiency. While language dominance is not of major influence in L3 production, it can shape less typical pronunciations. Finally, the study shows that the cognate status does not affect L3 production accuracy alone, at least in the repertoire of languages investigated in this study, but rather in combination with the bilinguals’ degree of language dominance.” Finally, by using cognate and non-cognate vocabulary in the research, the role of background languages (L1 and L2) in shaping CLI to L3 on a structure-by-structure basis was measured. The results allowed a better understanding of the role of L3 proficiency, language dominance based on use and cognate status between L1–L2 and L3 vocabulary on the production of the lateral in L3.

Funding

This research was funded by the Polish National Science Centre, grant number 2018/02/X/HS2/01244.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pomeranian Academy in Słupsk, Poland (date of approval 10 February 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Stimuli divided into conditions and their cognates in Ukrainian and Russian.

Table A1.

Stimuli divided into conditions and their cognates in Ukrainian and Russian.

| Polish Stimuli | Condition | Ukrainian | Russian |

|---|---|---|---|

| lawa (Eng. lava) | VEL/VEL | лава [ɫ] | лава [ɫ] |

| flag (Eng. flag, genitive, plural) | VEL/VEL | флагoв [ɫ] | флагoв [ɫ] |

| laurowy (Eng. laurel, adj.) | VEL/VEL | лаурoвий [ɫ] | лаврoвый [ɫ] |

| myślałam (Eng. think, past tense, 1st person, singular fem.) | VEL/VEL | мслила [ɫ] | мьíслила [ɫ] |

| mleko (Eng. milk) | VEL/VEL | мoлoкo [ɫ] | мoлoкo [ɫ] |

| Polak (Eng. Pole) | PAL/PAL | пoляк [lʲ] | пoляк [lʲ] |

| chleb (Eng. bread) | PAL/PAL | хліб [lʲ] | хлеб [lʲ] |

| lubić (Eng. like) | PAL/PAL | любити [lʲ] | любить [lʲ] |

| leczyć (Eng. cure) | PAL/PAL | лікувати[lʲ] | лечить[lʲ] |

| lód (Eng. ice) | PAL/PAL | лід [lʲ] | лед [lʲ] |

| bilet (Eng. ticket) | VEL/PAL | билет [ɫ] | билет [lʲ] |

| seler (Eng. celery) | VEL/PAL | селéра[ɫ] | сельдерей [lʲ] |

| naklejka (Eng. sticker) | VEL/PAL | наклейка [ɫ] | наклейка [lʲ] |

| lekko (Eng. lightly) | VEL/PAL | легкo[ɫ] | легкó [lʲ] |

| lew (Eng. lion) | VEL/PAL | лев [ɫ] | лев [lʲ] |

| sklep (Eng. shop) | No Cog | крамниця | магазин |

| zespole (Eng. team, locative, singular) | No Cog | кoмáнді | кoмáнде |

| kolejny (Eng. next) | No Cog | наступний | следующий |

| pisklę (Eng. baby bird) | No Cog | цыпленoк | курча |

| lukier (Eng. frosting) | No Cog | глазур | глазурь |

Table A2.

Biodata: age, nationality, region, native language and language(s) spoken at home.

Table A2.

Biodata: age, nationality, region, native language and language(s) spoken at home.

| Participant | Age | Nationality | Region | Native Language | Language(s) Spoken at Home | Language(s) Spoken Outside Home |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 17 | Ukrainian | Lviv | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 3 | 18 | Ukrainian | Khmelnytskyi | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 43 | 19 | Ukrainian | Vinnytsia | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 44 | 20 | Ukrainian | Ivano-Frankivsk | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 5 | 21 | Ukrainian | Rivne | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 6 | 20 | Ukrainian | Lviv | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 9 | 22 | Ukrainian | Khmelnytskyi | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 30 | 20 | Ukrainian | Lviv | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 18 | 21 | Ukrainian | Volyn | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 19 | 20 | Ukrainian | Volyn | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 20 | 20 | Ukrainian | Rivne | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 24 | 20 | Ukrainian | Volyn | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 25 | 20 | Ukrainian | Volyn | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 16 | 19 | Ukrainian | Ivano-Frankivsk | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 15 | 19 | Ukrainian | Ivano-Frankivsk | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 41 | 19 | Ukrainian | Ivano-Frankivsk | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 39 | 20 | Ukrainian | Ivano-Frankivsk | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 40 | 19 | Ukrainian | Ivano-Frankivsk | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 100 | 20 | Ukrainian | Zhytomyr | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 58 | 19 | Ukrainian | Lviv | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

| 26 | 21 | Ukrainian | Ternopil | Ukrainian | Ukrainian | Ukrainian/Russian |

Table A3.

BLP: language history, language use, language proficiency and language attitudes.

Table A3.

BLP: language history, language use, language proficiency and language attitudes.

| Participant | BLP | Language History | Language Use | Language Proficiency | Language Attitudes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −118.326 | −19.976 | −37.06 | −6.81 | −54.48 |

| 3 | −65.476 | −15.436 | −25.07 | −2.27 | −22.7 |

| 43 | −104.798 | −12.258 | −40.33 | −11.35 | −40.86 |

| 44 | −133.676 | −26.786 | −50.14 | −24.97 | −31.78 |

| 5 | −32.966 | −6.356 | −15.26 | −6.81 | −4.54 |

| 6 | −131.042 | −35.412 | −47.96 | −15.89 | −31.78 |

| 9 | −88.454 | −25.424 | −40.33 | −15.89 | −6.81 |

| 30 | −73.74 | −27.24 | −28.34 | −2.27 | −15.89 |

| 18 | −105.978 | −30.418 | −39.24 | −2.27 | −34.05 |

| 19 | −85.094 | −11.804 | −39.24 | 0 | −34.05 |

| 20 | −70.47 | −13.62 | −25.07 | 0 | −31.78 |

| 24 | −130.226 | −38.136 | −51.23 | −4.54 | −36.32 |

| 25 | −55.126 | −17.706 | −28.34 | 0 | −55.126 |

| 16 | −133.584 | −25.424 | −46.87 | −9.08 | −52.21 |

| 15 | −123.96 | −22.7 | −49.05 | 15.89 | −36.32 |

| 41 | −166.722 | −42.222 | −35.97 | −34.05 | −54.48 |

| 39 | −123.416 | −17.706 | −51.23 | 0 | −54.48 |

| 40 | −156.008 | −44.038 | −37.06 | −20.43 | −54.48 |

| 100 | −35.776 | −6.356 | −2.18 | 0 | −27.24 |

| 58 | −107.07 | −6.81 | −45.78 | −11.35 | −43.13 |

| 26 | −109.158 | −32.688 | −44.69 | −4.54 | −27.24 |

Table A4.

Foreign language knowledge (L3 Polish based on placement test results, Russian proficiency based on BLP and other foreign language proficiency is self-reported).

Table A4.

Foreign language knowledge (L3 Polish based on placement test results, Russian proficiency based on BLP and other foreign language proficiency is self-reported).

| Participant | Polish Placement Test Results | Other Foreign Languages |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 97% B1 | Russian, English (B1) |

| 3 | 96% B1 | Russian, English (A2) |

| 43 | 97% B1 | Russian, English (B1) |

| 44 | 97% B1 | Russian, English (B1) |

| 5 | 93% B1 | Russian, English (A2) |

| 6 | 87% A2+ | Russian, English (A2) |

| 9 | 97% B1 | Russian, English (A2) |

| 30 | 80% A2 | Russian, English (A2) |

| 18 | 79% A2 | Russian, English (B1) |

| 19 | 79% A2 | Russian, English (B1) |

| 20 | 79% A2 | Russian, English (B1) |

| 24 | 88% A2+ | Russian, English (A2) |

| 25 | 87% A2+ | Russian, English (B1) |

| 16 | 82% A2 | Russian, English (A2) |

| 15 | 84% A2 | Russian, English (B1) |

| 41 | 97% B1 | Russian, English (B1) |

| 39 | 96% B1 | Russian, English (B1) |

| 40 | 96% B1 | Russian, English (B1) |

| 100 | 89% A2+ | Russian, English (B1) |

| 58 | 83% A2 | Russian, English (B1) |

| 26 | 92% B1 | Russian, English (B1) |

Notes

| 1. | Although all participants use Russian on a daily basis, they refer to the language as foreign. |

| 2. | There were two instances of the voiced labiodental fricative and three instances of the palatal approximant that were discarded from the final analysis. |

References

- Amengual, Mark. 2012. Interlingual influence in bilingual speech: Cognate status effect in a continuum of bilingualism. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 15: 517–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amengual, Mark. 2021. The acoustic realization of language-specific phonological categories despite dynamic cross-linguistic influence in bilingual and trilingual speech. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 149: 1271–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartolotti, James, and Viorica Marian. 2018. Learning and processing of orthography-to-phonology mappings in a third language. International Journal of Multilingualism 16: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birdsong, David. 2006. Age and Second Language Acquisition and Processing: A selective overview. Language Learning 56: 9–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdsong, David, Libby M. Gertken, and Mark Amengual. 2012. Bilingual Language Profile: An Easy-to-Use Instrument to Assess Bilingualism. University of Texas at Austin. Available online: https://sites.la.utexas.edu/bilingual/ (accessed on 2 January 2019).

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2021. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer. Computer Program Version 6.2.03. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Bosma, Evelyn, Elma Blom, Eric Hoekstra, and Arjen Versloot. 2019. A longitudinal study on the gradual cognate facilitation effect in bilingual children’s Frisian receptive vocabulary. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22: 371–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bouchhioua, Nadia. 2016. Cross-Linguistic Influence on the Acquisition of English Pronunciation by Tunisian EFL. Learners European Scientific Journal 12: 260–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burkat, Agnieszka, Agnieszka Jasińska, Małgorzata Małolepsza, and Aneta Szymkiewicz. 2008. HURRA!!! Po Polsku—Test Kwalifikacyjny. Kraków: Prolog Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Cal, Zuzanna, and Jolanta Sypiańska. 2021. The interaction of L2 and L3 levels of proficiency in third language acquisition. Poznan Studies in Contemporary Linguistics 56: 577–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Albert, Alfonso Caramazza, and Nuria Sebastián-Gallés. 2000. The Cognate Facilitation Effect: Implications for Models of Lexical Access. Journal of Experimental Psychology, Learning Memory and Cognition 26: 1283–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubberley, Paul. 2002. Russian: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis, Gessica. 2007. Third or Additional Language Acquisition. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Flege, James E. 1995. Second-language Speech Learning: Theory, Findings, and Problems. In Speech Perception and Linguistic Experience: Issues in Cross-language research. Edited by Winifred Strange. Timonium: York Press, pp. 229–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, Christoph, and Exequiel Rusca-Ruths. 2014. Der Sprachrhythmus bei deutsch-türkischen L3-Spanischlernern: Positiver Transfer aus der Herkunftssprache? In Mehrsprachigkeit als Chance. Herausforderungen und Potentiale Individueller und Gesellschaftlicher Mehrsprachigkeit. Edited by Stefanie Witzigmann and Jutta Rymarczyk. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo del Puerto, Francisco. 2007. On the Effectiveness of Early Foreign Language Instruction in School Contexts. In Fremdsprachenkompetenzen für ein Wachsendes Europa: Das Leitziel Multiliteralität. Edited by LutzKüster Daniela Elsner and Britta Viebrock. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, pp. 215–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gertken, Libby, Mark Amengual, and David Birdsong. 2014. Assessing Language Dominance with the Bilingual Language Profile: Perspectives from SLA. In Measuring L2 Proficiency: Perspectives from SLA. Edited by Pascale LeClercq, Amanda Edmonds and Heather Hilton. Bristol: Multilingual Matters, pp. 208–25. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, François. 1998. Studying bilinguals: Methodological and conceptual issues. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 1: 131–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guion, Susan, James E. Flege, and John D. Loftin. 2000. The effect of L1 use on pronunciation in Quichua-Spanish bilinguals. Journal of Phonetics 28: 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gut, Ulrike. 2010. Cross-linguistic influence in L3 phonological acquisition. International Journal of Multilingualism 13: 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarberg, Björn. 2001. Roles of L1 and L2 in L3 production and acquisition. In Cross-Linguistic Influence in Third Language Acquisition: Psycholinguistic Perspectives. Edited by Jasone Cenoz, Britta Hufeisen and Ulrike Jessner. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hammarberg, Björn. 2010. The languages of the multilingual: Some conceptual and terminological issues. IRAL, International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching 48: 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarberg, Björn. 2018. L3, the tertiary language. In Foreign Language Education in Multilingual Classroom. Edited by Andreas Bonnet and Peter Siemund. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, pp. 127–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hammarberg, Björn, and Britta Hammarberg. 2005. Re-setting the basis of articulation in the acquisition of new languages: A third language case study. In Processes in Third Language Acquisition. Edited by Björn Hammarberg. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Janyan, Armina, and Marina Hristova. 2007. Gender-Congruency and Cognate Effect in Bulgarian-English Bilinguals: Evidence from a Word-Translation Task. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society 29: 1121–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman, Eric. 1983. Now you see it, now you don’t. In Language Transfer in Language Learning. Edited by Susan M. Gass and Larry Selinker. Rowley: Newbury House Publishers, pp. 112–34. [Google Scholar]

- Kopečkova, Romana. 2016. The bilingual advantage in L3 learning: A developmental study of rhotic sounds. International Journal of Multilingualism 13: 410–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopečkova, Romana, Ulrike Gut, and Christina Golin. 2019. Acquisition of the /v/-/w/ contrast by L1 German children and adults. Paper presented at 19th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Melbourne, Australia, August 5–9; pp. 3745–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lemhöfer, Kristin, and Ton Dijkstra. 2004. Recognizing cognates and interlingual homographs: Effects of code similarity in language-specific and generalized lexical decision. Memory & Cognition 32: 533–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Smith, Anika. 2021. Perceived foreign accent in L3 English: The effects of heritage language use. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Smith, Anika, Henrik Gyllstad, and Tanja Kupisch. 2017. Transfer into L3 English: Global accent in German-dominant heritage speakers of Turkish. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 7: 131–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mora, Juan-Carles, and Marianna Nadeu. 2012. L2 effects on the perception and production of a native vowel contrast in early bilinguals. International Journal of Bilingualism 16: 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Christina, Iga Krzysik, Halina Lewandowska, and Magdalena Wrembel. 2021. Multilingual learners’ perceptions of cross-linguistic distances: A proposal for a visual psychotypological measure. Language Awareness 30: 176–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlenko, Aneta. 2004. ‘Stop Doing That, Ia Komu Skazala!’: Language Choice and Emotions in Parent—Child Communication. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 25: 179–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringbom, Håkan. 1987. Role of the First Language in Foreign Language Learning. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Shevelov, George Yurij. 2002. Ukrainian. In The Slavonic Languages. Edited by Bernard Comrie and Greville G. Corbett. London: Routledge, pp. 947–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sypiańska, Jolanta, and Zuzanna Cal. 2020. The influence of level of proficiency in the L2 and L3 on the production of the L3 Spanish apico-alveolar sibilant. Research in Language 18: 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sypiańska, Jolanta, and Elena-Raluca Constantin. 2021. New vs. similar sound production accuracy: The uneven fight. Yearbook of the Poznań Linguistic Meeting 7: 155–79. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, Annie. 2007. Bridging the Gap between Theoretical Linguistics and Psycholinguistics in L2 Phonology: Acquisition and Processing of Word Stress by French Canadian L2 Learners of English. Unpublished. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Hawai’i, Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui, Rachel K. Y., and Xiuli Tong. 2019. Impact of language dominance on phonetic transfer in Cantonese–English bilingual language switching. Applied Psycholinguistics 40: 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Sarah, and Björn Hammarberg. 1998. Language switches in L3 production: Implications for a polyglot speaking model. Applied Linguistics 19: 295–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrembel, Magdalena. 2010. L2-accented speech in L3 production. International Journal of Multilingualism 7: 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).