Lexical Category and Downstep in Japanese

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| 1. | a. | ane-wa | aóku | nagái | négi | to | itta |

| big sister-TOP | blue | long | leek | COMP | say.PAST | ||

| ‘My big sister said, “Green and long leek”’. | |||||||

| b. | ane-wa | amaku | nagái | négi | to | itta | |

| big sister-TOP | sweet | long | leek | COMP | say.PAST | ||

| ‘My big sister said, “Sweet and long leek”’. | |||||||

2. Japanese Downstep and Syntax

| 2. | a. | An example of [N1 [N2 N3]] | ||

| nómo-no | !nára-no | mamé | ||

| Nomo-GEN | Nara-GEN | bean | ||

| ‘Nomo’s beans from Nara’ | ||||

| b. | An example of [A1 [A2 N]] | |||

| shirói | nagái | mamé | ||

| white | long | bean | ||

| ‘long white beans’ | ||||

| 3. | a. | An example of [[VPAST]RC [[APAST]RC N]]NP | ||

| [[niránda]RC | [[(!)darúkatta]RC | magó]]NP | ||

| stare.PAST | tired.PAST | grandchild | ||

| ‘a grandchild who stared disfavourably and was tired’ | ||||

| b. | An example of [[VPAST]RC [[VPAST]RC N]]NP | |||

| [[najínda]RC | [[!niránda]RC | magó]]NP | ||

| get adjusted.PAST | stare.PAST | grandchild | ||

| ‘a grandchild who got adjusted and stared disfavourably’ | ||||

| 4. | a. | An example of N-ga A | ||

| magó-ga | !nemúi | |||

| grandchild-NOM | sleepy | |||

| ‘‘(Someone’s) grandchild is sleepy’. | ||||

| b. | An example of N-ga V | |||

| magó-ga | !nirámu | |||

| grandchild-NOM | stare | |||

| ‘(Someone’s) grandchild stares (at someone) disfavourably’. | ||||

| 5. | a. | An example of [[VNONPAST]RC [[VNONPAST]RC N]]NP | |||

| [[mayóu]RC | [[!nayámu]RC | magó]]NP | |||

| get lost.NONPAST | worry.NONPAST | grandchild | |||

| ‘a grandchild who gets lost and worries’ | |||||

| b. | An example of [[VPAST]RC [[N CopulaPAST]RC N]]NP | ||||

| [[nayánda]RC | [[!dame | datta]RC | magó]]NP | ||

| worry.PAST | no good | Copula | grandchild | ||

| ‘a grandchild who worried and was no good’ | |||||

| c. | An example of N-ga N | ||||

| magó-ga | !námi | ||||

| grandchild-NOM | Nami | ||||

| ‘(My) grandchild is called Nami’. | |||||

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Speech Materials

| 6. | a. | [[N1 N2] N3] where N1 is accompanied by -to | ||

| [[négi-to | rámu-no] | nábe] | ||

| leek-and | lamb-GEN | hot pot | ||

| ‘hot pot that has leek and lamb’ | ||||

| b. | [[N1 N2] N3] where N1 is accompanied by -de | |||

| [[múmi-de | rámu-no] | nábe]6 | ||

| tasteless-DE | lamb-GEN | hot pot | ||

| ‘hot pot that is tasteless and has lamb’ | ||||

| 7. | a. | [[V1 V2] N] where V1 is in the continuative form | ||

| [[nómi | nayámu] | mámi] | ||

| drink | worry | Mami | ||

| ‘Mami, who drinks and gets worried’ | ||||

| b. | [[V1 V2] N] where V1 is in the -te form | |||

| [[nón-de | nayámu] | mámi] | ||

| drink-TE | worry | Mami | ||

| ‘Mami, who drinks and then gets worried’ | ||||

| 8. | [[A1 A2] N] where A1 is in the continuative form | |||

| [[aóku | nagái] | négi] | ||

| blue | long | leek | ||

| ‘green and long leek’ | ||||

| 9. | a. | Accented trigger (=(8)) | ||

| [[aóku | nagái] | négi] | ||

| blue | long | leek | ||

| ‘green and long leek’ | ||||

| b. | Unaccented trigger | |||

| [[amaku | nagái] | négi] | ||

| sweet | long | leek | ||

| ‘sweet and long leek’ | ||||

3.2. Recording and Speakers

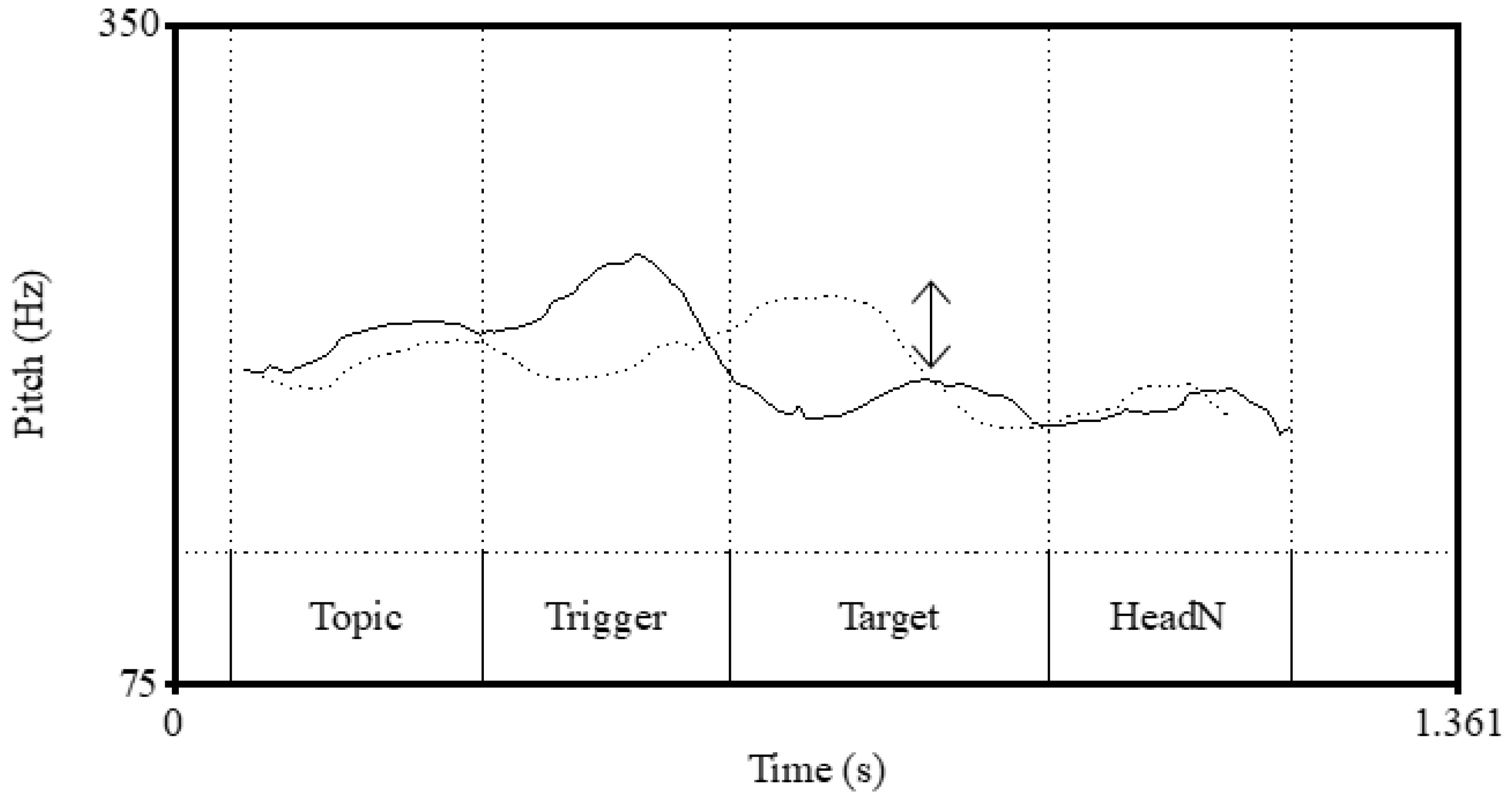

3.3. Acoustic Analysis and Statistics

| 10. | Peak f0s in intervals | ||||

| |ane-wa | |aóku | |nagái | |négi | |to itta | |

| sister-TOP | blue | long | leek | COMP say.PAST | |

| (My) sister said, ‘green and long leek’. | |||||

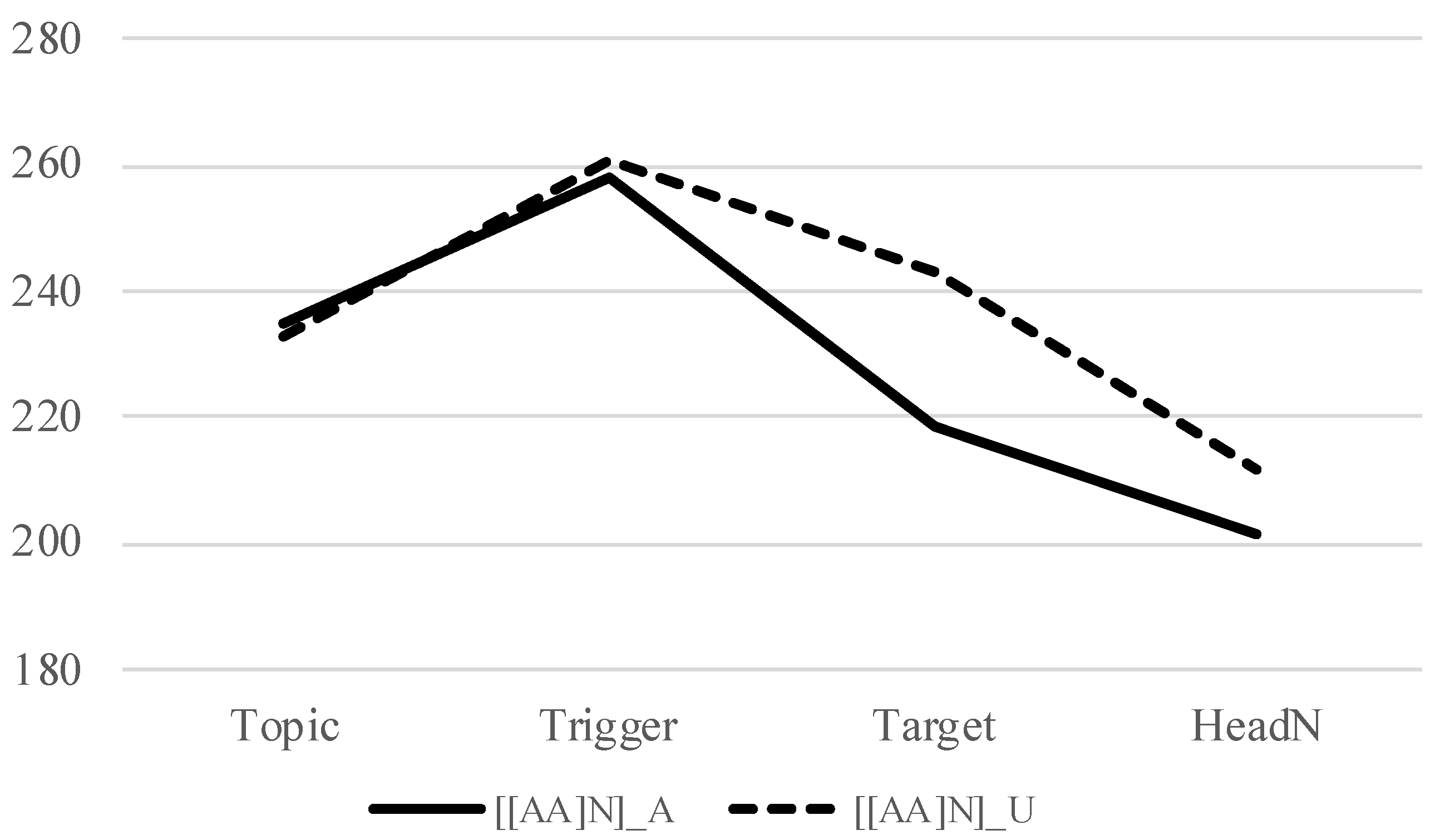

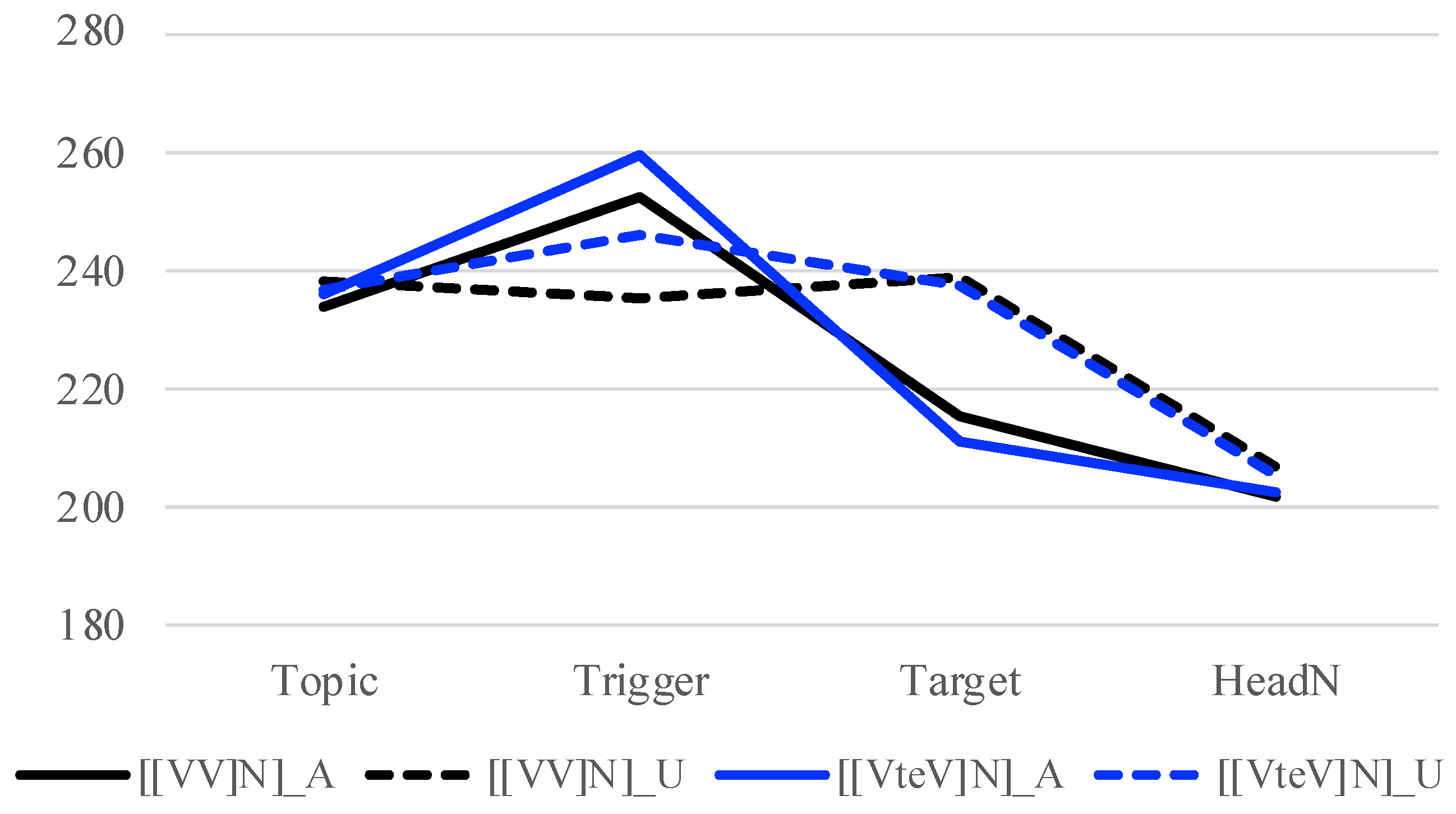

4. Results

5. Discussion

| 11. | MaP phrasing for [X1 [X2 N]] | ||

| a. | X2 = A | ||

| Variation between ((X1)MiP)MaP ((X2)MiP (N)MiP)MaP and ((X1)MiP (X2)MiP (N)MiP)MaP | |||

| b. | X2 = N, V | ||

| ((X1)MiP (X2)MiP (N)MiP)MaP | |||

| 12. | MaP phrasing for [[X1 X2] N] and [N-ga X] | ||

| a. | [[X1 X2] N] | ||

| ((X1)MiP (X2)MiP (N)MiP)MaP | |||

| b. | [N-ga X] | ||

| ((N-ga)MiP (X)MiP)MaP | |||

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. List of Test Phrases

- Adjectives

| Trigger accent | Trigger | Target | Head N | |

| A-ku A-i | Accented | aóku | nagái | négi |

| green | long | leek | ||

| Accented | umáku | nagái | négi | |

| good | long | leek | ||

| Unaccented | maruku | nagái | négi | |

| round | long | leek | ||

| Unaccented | amaku | nagái | négi | |

| sweet | long | leek |

- 2.

- Verbs

| Trigger accent | Trigger | Target | Head N | |

| V-i V-u | Accented | nómi | nayámu | mámi |

| drink | get worried | Mami | ||

| Accented | yómi | nayámu | mámi | |

| read | get worried | Mami | ||

| Unaccented | umi | nayámu | mámi | |

| give birth to | get worried | Mami | ||

| Unaccented | yobi | nayámu | mámi | |

| call | get worried | Mami | ||

| -te | Accented | nónde | nayámu | mámi |

| drink | get worried | Mami | ||

| Accented | yónde | nayámu | mámi | |

| read | get worried | Mami | ||

| Unaccented | unde | nayámu | mámi | |

| give birth to | get worried | Mami | ||

| Unaccented | yonde | nayámu | mámi | |

| call | get worried | Mami |

- 3.

- Nouns

| Trigger accent | Trigger | Target | Head N | |

| N-to N | Accented | négi-to | rámu-no | nábe |

| leek-and | lamb-NO | hot pot | ||

| Accented | násu-to | rámu-no | nábe | |

| eggplant-and | lamb-NO | hot pot | ||

| Unaccented | nira-to | rámu-no | nábe | |

| Chinese chive-and | lamb-NO | hot pot | ||

| Unaccented | momo-to | rámu-no | nábe | |

| peach-and | lamb-NO | hot pot | ||

| N-de N | Accented | múmi-de | rámu-no | nábe |

| tasteless-and | lamb-NO | hot pot | ||

| Accented | múmi-de | négi-no | nábe | |

| tasteless-and | leek-NO | hot pot | ||

| Unaccented | mee-de | máma-no | mámi | |

| (my) niece-and | (a) mother-NO | Mami | ||

| Unaccented | mee-de | ána-no | mámi | |

| (my) niece-and | news caster-NO | Mami |

| 1 | The categories MaP and MiP are referred to as an intonation phrase and accentual phrase, respectively, in the ToBI frameworks (see Ishihara 2015, p. 570 for the variation in the terminology in the literature). |

| 2 | In Selkirk and Tateishi (1991), downstep is defined differently than it is in most studies on Japanese downstep. They use the so-called syntagmatic diagnostic, in which the presence/absence of downstep is determined within a sentence (e.g., Kubozono 2007; Ito and Mester 2013). Other scholars have also taken the syntagmatic approach (e.g., Hirotani 2005; Nagahara 1994). Other researchers use paradigmatic—as opposed to syntagmatic—diagnostic, in which the presence/absence of downstep is judged by comparing sentences with an accented phrase before the target phrase and those with an unaccented phrase in the same position, as in this study (see Section 3). See Ishihara (2015, pp. 585–86) for other methodological issues with Selkirk and Tateishi (1991). |

| 3 | The different results between Selkirk and Tateishi (1991) and other works discussed here (Hirayama and Hwang 2016; Hwang and Hirayama 2021; Kubozono 1992) are not due to dialectal differences. In all the works, the participants are speakers of Tokyo Japanese, i.e., the dialect that has the Tokyo accentuation system. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | It would be important to confirm this native speaker intuition with an experiment of naturalness ratings of native speakers. We leave the investigation in future work. |

| 6 | The word múmi ‘tasteless’ may be ambiguous between a noun and an adjectival noun (aka nominal adjective). Some dictionaries (e.g., Yamada et al. 2012) treat it as a noun and others as both categories. Here, we treat adjectival nouns as a subclass of nouns because they pattern with nouns rather than with adjectives in downstep (Hirayama and Hwang 2019). It is important to further investigate the patterns that adjectival nouns demonstrate with respect to downstep in future works. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | Although unaccented items do not trigger downstep, we call them triggers in this paper if they are in the position before the targets. |

| 9 | The result showing the statistically significant effect of accentedness remains the same if semitone is used instead of Hz as the unit of pitch measurement. |

| 10 | The prosodic phrasing in (11) and (12) is possible when words are all accented. If they are unaccented, the phrasing should be made differently. See, for example, Ito and Mester (2013) for a review of prosodic phrasing in Japanese. Also in the phrasing in (11) and (12a), we assume that the head nouns are downstepped. |

| 11 | We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out. |

| 12 | |

| 13 | |

| 14 | Given this analysis, several predictions can be made, as pointed out by an anonymous reviewer. For example, if the two verbs are in the -teiru forms, the verbs can denote states rather than events, in which case the temporal precedence relation would not be expected to hold between the two verbs (see the discussion on adjectives below). If so, the flow from V1 to V2 may be disturbed and downstep may be blocked as a result. Furthermore, if the two verbs in the non-teiru forms are reversed and if a temporal precedence relation is not held with that order, downstep may also be blocked as a consequence. We leave these predictions to test in future research. |

| 15 | This predicts that if the two As in [A1 [A2 N]] are in different tense forms, downstep is not blocked within the whole NP. The temporal precedence relation is held between A1 and A2 because one is in the past and the other not in the past. Since there is not a conflict in terms of the semantic relation, there will not be a MaP boundary at the beginning of the A2 and prosodic phrasing would be ((A1)MiP (A2)MiP (N)MiP)MaP. |

| 16 | The mean scores were 3.68 for [A-i [A-i N]], 4.31 for [A-na [A-na N]], 4.88 for [A-i [A-na N]] and 5.50 for [A-na [A-i N]]. A mixed-effects analysis (with speaker as random effects) revealed that the scores for [A-na [A-na N]] (β = 0.6230, p < 0.01), [A-i [A-na N]] (β = 1.1967, p < 0.001) and [A-na [A-i N]] (β = 1.8197, p < 0.001) are individually higher than the score for [A-i [A-i N]]. |

| 17 | We thank an anonymous reviewer for drawing our attention to the focus and MiP boundary in an unaccented trigger discussed in the next paragraph. |

References

- Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2020. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer [Computer Program]. Available online: http://www.praat.org/ (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- den Dikken, Marcel, and Pornsiri Singhapreecha. 2004. Complex noun phrases and linkers. Syntax 7: 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Féry, Caroline. 2015. Extraposition and prosodic monsters in German. In Explicit and Implicit Prosody in Sentence Processing. Studies in Honor of Janet Dean Fodor. Edited by Lyn Frazier and Edward Gibson. Amsterdam: Springer, pp. 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- Fougeron, Cécile. 2001. Articulatory properties of initial segments in several prosodic constituents in French. Journal of Phonetics 29: 109–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hirayama, Manami, and Hyun Kyung Hwang. 2016. Downstep in Japanese revisited: Lexical category matters. Paper presented at the 15th Conference on Laboratory Phonology, Cornell University, New York, NY, USA, July 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama, Manami, and Hyun Kyung Hwang. 2019. Relative clause and downstep in Japanese. In Supplement Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Meeting on Phonology. Edited by Katherine Hout, Anna Mai, Adam McCollum, Sharon Rose and Matt Zaslansky. Washington: Linguistic Society of America. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, Manami, Hyun Kyung Hwang, and Takaomi Kato. 2019. Lexical category in downstep in Japanese. In Proceedings of the 19th International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Melbourne, Australia 2019. Edited by Sasha Calhourn, Paola Escudero Marija Tabain and Paul Warren. Canberra: Australasian Speech Science and Technology Association Inc., pp. 2851–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hirotani, Masako. 2005. Prosody and LF: Processing Japanese Wh-Questions. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, Hyun Kyung, and Manami Hirayama. 2021. Downstep in Japanese revisited: Morphology matters. NINJAL Research Papers 21: 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi, Yosuke. 2015. Intonation. In Handbook of Japanese Phonetics and Phonology. Edited by Haruo Kubozono. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton, pp. 525–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, Shinichiro. 2015. Syntax-phonology interface. In Handbook of Japanese Phonetics and Phonology. Edited by Haruo Kubozono. Berlin: de Gruyter Mouton, pp. 569–618. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara, Shinichiro. 2016. Japanese downstep revisited. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 34: 1389–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, Shinichiro. 2019. On the relation between syntactic and phonological clauses. Paper presented at 6th NINJAL International Conference on Phonetics and Phonology, National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics, Tokyo, Japan, December 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2012. Recursive prosodic phrasing in Japanese. In Prosody Matters: Essays in Honor of Elisabeth Selkirk. Edited by Toni Borowsky, Shigeto Kawahara, Takahito Shinya and Mariko Sugahara. Sheffield: Equinox, pp. 280–303. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2013. Prosodic subcategories in Japanese. Lingua 124: 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, Shigeto, and Takahito Shinya. 2008. The intonation of gapping and coordination in Japanese: Evidence for Intonational Phrase and Utterance. Phonetica 65: 62–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubozono, Haruo. 1988. The Organization of Japanese Prosody. Ph.D. dissertation, Edinburgh University, Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Kubozono, Haruo. 1989. Syntactic and rhythmic effects on downstep in Japanese. Phonology 6: 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubozono, Haruo. 1992. Modeling syntactic effects on downstep in Japanese. In Papers in Laboratory Phonology II. Edited by Gerard J. Docherty and D. Robert Ladd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 368–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kubozono, Haruo. 1993. The Organization of Japanese Prosody. Tokyo: Kurosio. [Google Scholar]

- Kubozono, Haruo. 2007. Focus and intonation in Japanese: Does focus trigger pitch reset? In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Prosody, Syntax, and Information Structure (WPSI2), Interdisciplinary Studies on Information Structure. Edited by Shinichiro Ishihara. Potsdam: Potsdam University Press, vol. 9, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kuno, Susumu. 1973. The Structure of the Japanese Language. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nagahara, Hiroyuki. 1994. Phonological Phrasing in Japanese. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Nespor, Marina, and Irene Vogel. 1986. Prosodic Phonology. Dordrecht: Foris Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pierrehumbert, Janet, and Mary Beckman. 1988. Japanese Tone Structure. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Poser, William. 1984. The Phonetics and Phonology of Tone and Intonation in Japanese. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. 2019. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Selkirk, Elisabeth O. 1984. Phonology and Syntax: The Relation between Sound and Structure. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, Elisabeth. 2009. On clause and Intonational Phrase in Japanese: The syntactic grounding of prosodic constituent structure. Gengo Kenkyu 136: 35–73. [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk, Elisabeth, and Koichi Tateishi. 1991. Syntax and downstep in Japanese. In Interdisciplinary Approaches to Language. Edited by Carol Georgopoulos and Roberta Ishihara. Dordrecht: Kluwer, pp. 519–43. [Google Scholar]

- Takano, Yuji. 2004. Coordination of verbs and two types of verbal inflection. Linguistic Inquiry 35: 168–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 1995. Phonological Phrases: Their Relation to Syntax, Focus, and Prominence. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Yi. 2013. ProsodyPro—A Tool for Large-scale Systematic Prosody Analysis. Paper presented at Tools and Resources for the Analysis of Speech Prosody (TRASP 2013), Aix-en-Provence, France, August 30; pp. 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada, Tadao, Takeshi Shibata, Kenji Sakai, Yasuo Kuramochi, Akio Yamada, Zendo Uwano, Masahiro Ijima, and Hiroyuki Sasahara, eds. 2012. Shinmeikai Kokugo Jiten (Shinmeikai Japanese Dictionary), 7th ed. Tokyo: Sanseido. [Google Scholar]

- Yamakido, Hiroko. 2000. Japanese attributive adjectives are not (all) relative clauses. Paper presented at WCCFL 19 Proceedings, Los Angeles, CA, USA, February 4–6; pp. 588–602. [Google Scholar]

- Yamakido, Hiroko. 2005. The Nature of Adjectival Inflection in Japanese. Ph.D. dissertation, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

| Noun | Adjective | Verb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attributive ([X [X N]]) | Nonpast | Yes | No | Yes |

| Past | Yes | Yes/No 1 | Yes | |

| Predicative (N-ga X) | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| β (Hz) | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [[N1-to N2 ] N] (6a) | (intercept) | 215.590 | 16.48 | <0.001 |

| Trigger unaccented | 29.569 | 25.87 | <0.001 | |

| [[N1-de N2 ] N] (6b) | (intercept) | 219.688 | 16.88 | <0.001 |

| Trigger unaccented | 22.547 | 17.45 | <0.001 | |

| [[V1 V2 ] N] (7a) | (intercept) | 215.88 | 17.66 | <0.001 |

| Trigger unaccented | 23.25 | 19.70 | <0.001 | |

| [[V1-te V2 ] N] (7b) | (intercept) | 211.403 | 16.79 | <0.001 |

| Trigger unaccented | 26.102 | 23.20 | <0.001 | |

| [[A1 A2 ] N] (8) | (intercept) | 219.684 | 17.36 | <0.001 |

| Trigger unaccented | 23.430 | 16.01 | <0.001 |

| Noun | Adjective | Verb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attributive | [X [X N]] | Nonpast | Yes | No | Yes |

| Past | Yes | Yes/No 1 | Yes | ||

| [[X X] N] | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| Predicative (N-ga X) | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hirayama, M.; Hwang, H.K.; Kato, T. Lexical Category and Downstep in Japanese. Languages 2022, 7, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010025

Hirayama M, Hwang HK, Kato T. Lexical Category and Downstep in Japanese. Languages. 2022; 7(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleHirayama, Manami, Hyun Kyung Hwang, and Takaomi Kato. 2022. "Lexical Category and Downstep in Japanese" Languages 7, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010025

APA StyleHirayama, M., Hwang, H. K., & Kato, T. (2022). Lexical Category and Downstep in Japanese. Languages, 7(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010025