3.1. Overt Extraction

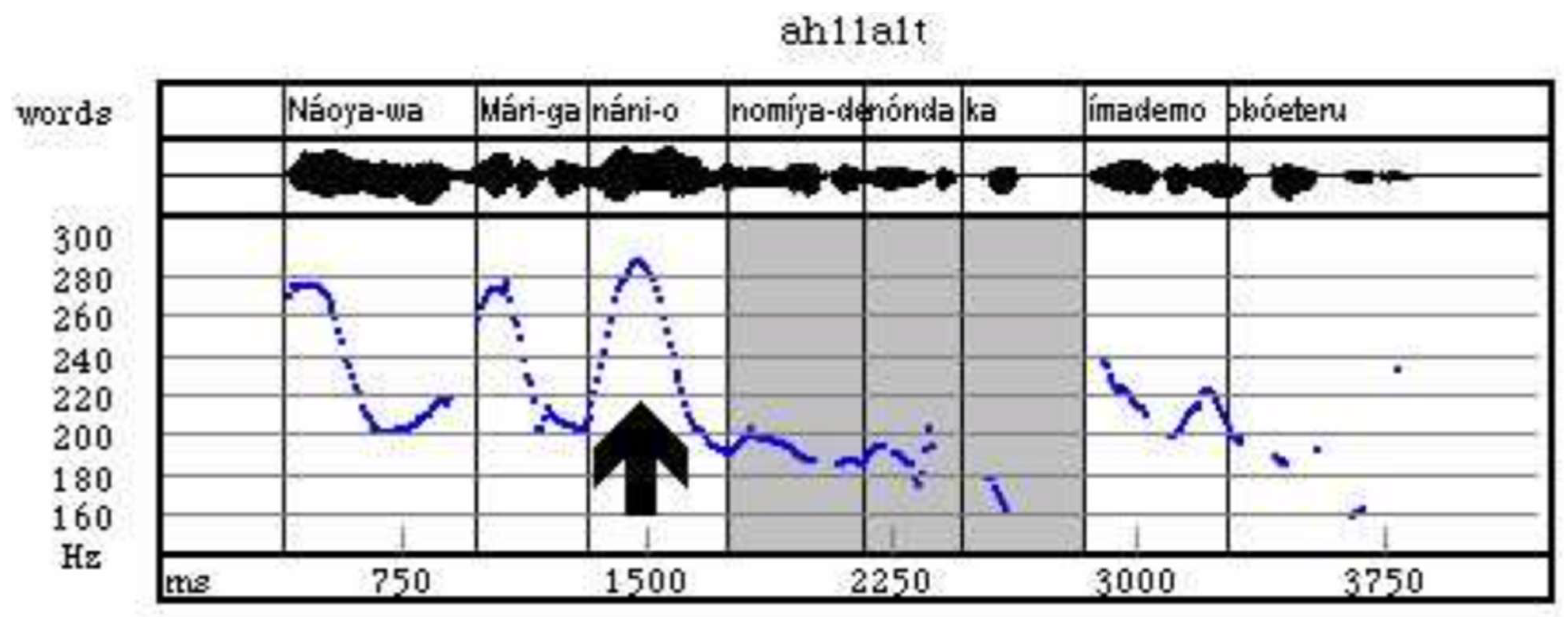

Let us begin with overt extraction. Contrary to the prediction of the LF-copying analysis, in this subsection, I demonstrate that overt extraction from PSE sites is possible. The first case to consider is raising-to-object constructions (

Hiraiwa, 2001;

Tanaka, 2002; among others), as illustrated in (12):

| (12) | [TPTaro-ga | [vPAi-oi | kokorokara | [CP ti | baka-da | to] | omotta]] |

| | Taro-nom | Ai-acc | really | | foolish-cop | c | thought |

| | ‘Taro really considered Ai to be a fool.’ |

The CP-internal accusative argument

Ai is moved to the matrix domain in (12), appearing beyond the matrix adjunct

kokorokara, ‘really’. When this sentence is reformulated as a yes-no question, as in (13a), the answer in (13b) now undergoes PSE:

| (13) | a. | [TPTaro-ga | [vP Ai-oi | kokorokara [CP ti | baka-da | to] | omotta]] | no? |

| | | Taro-nom | Ai-acc | really | foolish-cop | c | thought | q |

| | | ‘Did Taro really consider Ai to be a fool?’ |

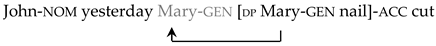

| | b. | [[CPTo]j [TP | Ken-ga [vP | Akemi-oi | kokorokara | tj | omotta]]] | yo |

| | | c | Ken-nom | Akemi-acc | really | | thought | prt |

| | | ‘Ken really considered Akemi to be a fool.’ |

In (13b), the embedded CP moves to the sentence-initial position via scrambling, ultimately leaving the overt C head

to behind. The sentence undergoes the following derivational steps, which are informally represented below:

| (14) | i. | [TP really [CP Akemi-acc foolish-cop c] thought ] prt |

| | ii. | ![Languages 10 00216 i004 Languages 10 00216 i004]() |

| | iii. | ![Languages 10 00216 i005 Languages 10 00216 i005]() |

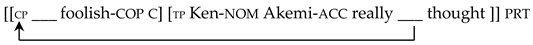

| | iv. | [[CP ___ foolish-cop c] [TP Ken-nom Akemi-acc really ___ thought ]] prt |

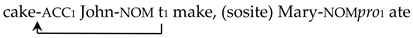

Beginning with the base structure in (14i), (14ii) demonstrates that the accusative argument

Akemi moves from the embedded CP into the matrix clause. In (14iii), the CP is scrambled across the matrix subject

Ken, and finally, in (14iv), it is elided via PSE. These derivational steps suggest that the accusative-marked

Akemi is extracted from the clausal argument that ultimately undergoes PSE, suggesting that the clause in question displays an overt internal structure.

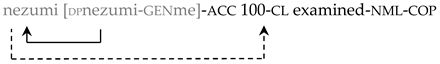

3Raising-to-subject constructions (

Hiraiwa, 2001,

2010, among others) in (15), together with the raising-to-object constructions, reinforce the current conclusion. The steps in their derivation are shown below:

| (15) | a. | [TP Taro-gai | minna-ni | [CP ti | baka-da | to] | omow-arete-iru] | no? |

| | | Taro-nom | everyone-dat | | foolish-pres | c | think-pass-pres | q |

| | | ‘Is Taro thought to be stupid by everyone?’ |

| | b. | [[CP To]j | [TP | Mary-gai | minna-ni | tj | omow-arete-iru]] | yo |

| | | c | | Mary-nom | everyone-dat | think-pass-pres | prt |

| | | ‘Mary is thought to be stupid by everyone.’ |

| (16) | i. | [TP everyone-dat [CP Mary-nom foolish-pres c] think-pass-pres] prt |

| | ii. | ![Languages 10 00216 i006 Languages 10 00216 i006]() |

| | iii. | ![Languages 10 00216 i007 Languages 10 00216 i007]() |

| | iv. | [[CP ___ foolish-pres c] [TP Mary-nom everyone-dat ___ think-pass-pres]] prt |

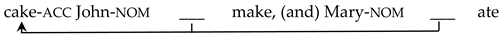

As shown in (16i), the matrix subject Mary is first base-generated within the embedded CP. Later in the derivation, it moves to the matrix Spec, TP position in (16ii), after which the CP scrambles over it in (16iii). Once displaced, the CP undergoes PSE in (16iv), producing the surface structure in (15b). These observations clearly point to overt extraction from the PSE sites, casting serious doubt on the LF-copying analysis, which does not predict surface representations such as (13b) and (15b).

Yet another argument regarding overt extraction is based on PP-internal N′-deletion, which is first developed by

Takita and Goto (

2013). Example (17a) illustrates a canonical case of N′-deletion (

Saito & Murasugi, 1990); (17b) shows that N′-deletion is still possible when a quantifier functions as its remnant, an observation that is crucial to Takita and Goto’s proposal:

| (17) | a. | Taro-no | taido-ga | yoi | ippou | Hanako-no | Δ-ga | yokunai |

| | | Taro-gen | attitude-nom | good | while | Hanako-gen | -nom | not.good |

| | | Lit. ‘Taro’s attitude is good while Hanako’s Δ is not good.’ |

| | b. | Sannin-no | sensei-ga | kita | ippou | gonin | Δ-ga | kaetta |

| | | three-gen | teachers-nom | come | while | fine | -nom | left |

| | | Lit. ‘three teachers came while fine Δ left.’ |

| | | (Adapted from Takita & Goto, 2013, p. 221) |

Consider (18), in which PP-internal N′-deletion takes place:

| (18) | a. | Kinseizin-wa | [ kinoo-no | kaseizin-no | koogeki | kara] | seikansita | |

| | | Venusians-top | yesterday-gen | Martians-gen | attack | from | survived | |

| | | Lit. ‘Venusians survived [from yesterday’s attack by Martians]’ |

| | b. | Suiseizin-wa | [kyoo-no | Δ | kara] | toosoosita | | |

| | | Mercurians-top | today-gen | | from | run.away | | |

| | | Lit. ‘Mercurians run away [from today’s Δ]’ |

| | c. | Suiseizin-wa | [kyoo-no | Δ | e] | taiousita | | |

| | | Mercurians-top | today-gen | | to | responded | | |

| | | Lit. ‘Mercurians responded [to today’s Δ]’ |

| | d. | Suiseizin-wa | [kyoo-no | Δ | de] | hiheisita | | |

| | | Mercurians-top | today-gen | | with | got.exhausted | |

| | | Lit. ‘Mercurians got exhausted [with today’s Δ]’ |

| | | (Adapted from Takita & Goto, 2013, pp. 217–218) |

With (18a) as the antecedent for (18b–d), while the postposition stranded in (18b) is identical to that in (18a), this is not the case in (18c–d). This suggests that PP-internal N′-deletion tolerates mismatches in postposition. Turning to (19), we observe that quantifiers can surface as remnants of PP-internal N′-deletion:

| (19) | a. | Kinseizin-wa | [subete-no | kaseizin-no | koogeki kara] | seikansita | |

| | | Venusians-top | all-gen | Martians-gen | attack | from | survived | |

| | | Lit. ‘Venusians survived [from all attacks by Martians]’ |

| | b. | Suiseizin-wa | [hotondo | Δ | kara] | toosoosita | | |

| | | Mercurians-top | most | | from | run.away | | |

| | | Lit. ‘Mercurians run away [from most Δ]’ |

| | c. | * | Suiseizin-wa | [hotondo | Δ | e] | taiousita | | |

| | | | Mercurians-top | most | | to | responded | | |

| | | | Lit. ‘Mercurians responded [to most Δ]’ |

| | d. | * | Suiseizin-wa | [hotondo | Δ | de] | hiheisita | | |

| | | | Mercurians-top | most | | with | got.exhausted | | |

| | | | Lit. ‘Mercurians got exhausted [with most Δ]’ |

| | | (adapted from Takita & Goto, 2013, p. 218) |

With (19a) as the antecedent, (19b), which employs the same postposition as (19a), is grammatical. In contrast, (19c–d), where different postpositions are stranded, are ungrammatical. Based on the contrast between (18) and (19), Takita and Goto conclude that PP-internal N′-deletion is blocked when (i) a quantifier serves as a remnant and (ii) the stranded postposition differs from that of the antecedent.

Takita and Goto’s (

2013) analytical basis follows

M. Takahashi’s (

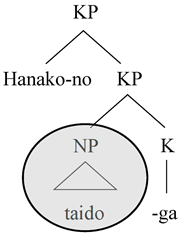

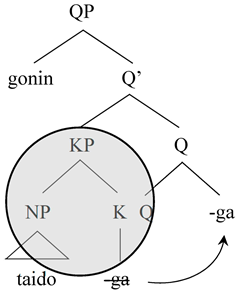

2011) formulation of N′-deletion, according to which the NP structure differs slightly depending on whether an ellipsis remnant includes a quantifier. Accordingly, the relevant structure for (17a) is (20a), while the quantifier-stranding version in (17b) corresponds to (20b), in which the K head overtly moves to Q, and the Spec-head licensing condition on the ellipsis is satisfied as a result.

4 Let us next consider how

M. Takahashi’s (

2011) analysis of N′-deletion accounts for the puzzling pattern of PP-internal N′-deletion above. Assuming that Japanese postpositions, such as case markers, belong to the K category,

Takita and Goto (

2013) analyze the elided structure in (19) as in (21), in which the K head undergoes overt movement to Q, thereby licensing the ellipsis of its KP complement:

The derivation in (21) suggests that the head movement of K only occurs when a quantifier remains after N′-deletion. Given that this process is akin to V-stranding VP-ellipsis, according to Takita and Goto, it is naturally expected that such N′-deletion is constrained by the well-known rigid identity condition on ellipsis (

Goldberg, 2005), which requires the remnant (i.e., the head) to be identical to the antecedent. The ungrammaticality of (19c–d) thus follows, since the heads that undergo movement differ between the antecedent (19a) and the targets (19c/d). The same explanation applies to (18). The structures involved are as follows:

| (22) | a. | [KP kinoo-no [NP kaseizin-no koogeki] kara] | (=(18a)) |

| | b. | [KP kinoo-no [NP kaseizin-no koogeki] kara] | (=(18b)) |

| | c. | [KP kinoo-no [NP kaseizin-no koogeki] e/de] | (=(18c/d)) |

| | | (Takita & Goto, 2013, p. 223) |

In the absence of a QP projection, head movement does not take place. Consequently, the rigid identity condition on ellipsis does not come into play, making postpositional mismatch possible. On this basis, Takita and Goto maintain that the structures and derivations outlined in (21) and (22) are empirically well justified.

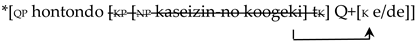

With these elements in place, let us examine whether overtly raised postpositions are compatible with PSE. If they are, this would suggest that there is an internal structure within the PSE site, thereby arguing against the LF-copying analysis. The answer is in the affirmative:

| (23) | a. | [Subete-no | kaseizin-no | koogeki | kara] | kinseizin-wa | seikansita | no? |

| | | all-gen | Martians-gen | attach | from | Venusians-top | survived | q |

| | | ‘Did Venusians survive from all attacks by Martians?’ |

| | b. | -Kara | pro (zannennagara) | seikansinakatta | yo | |

| | | -from | | unfortunately | not.survived | prt | |

| | | ‘(Unfortunately) they did not survive from all attacks by Martians.’ |

With (23a) as the antecedent, (23b) shows that the postposition -

kara, ‘from’, which survives N′-deletion, can undergo PSE. Moreover, various other postpositions and case markers also occur in post-ellipsis positions via PSE, which further confirms the current argument:

| (24) | a. | [ Subete-no | kaseizin-no | koogeki-de] | doseizin-wa | hiheisita | no? |

| | | all-gen | Martians-gen | attack-with | Saturnians-top | got.exhausted | q |

| | | ‘Did Saturnians get exhausted with all attacks by Martians?’ |

| | b. | -De | pro | hiheisita | wakedewanai | yo | |

| | | -with | | got.exhausted | it.is.not.the.case | prt | |

| | | ‘It is not the case that they got exhausted with all attacks by Martians.’ |

| (25) | a. | [Subete-no | kaseizin-no | koogeki-e] | doseizin-wa | taioosita | no? |

| | | all-gen | Martians-gen | attack-to | Saturnians-top | responded | q |

| | | ‘Did Saturnians respond to all attacks by Martians? |

| | b. | -E | pro | taioosita | yo | | |

| | | -to | | responded | prt | | |

| | | ‘They responded to all attacks by Martians.’ |

| (26) | a. | [Subete-no | kaseizin-no | koogeki-ga] | doseizin-o | nayamaseta | no? |

| | | all-gen | Martians-gen | attack-nom | Saturnians-acc | annoyed | q |

| | | ‘Did all attacks by Martians annoy Saturnians?’ |

| | b. | -Ga | suiseizin-o | nayamaseta-nda | yo | | |

| | | -nom | Mercurians-acc | annoyed-cop | prt | | |

| | | ‘They annoyed Mercurians.’ |

| (27) | a. | [Subete-no | kaseizin-no | koogeki-o] | doseizin-ga | yarisugosita | no? |

| | | all-gen | Martians-gen | attack-acc | Saturnians-nom | withstood | q |

| | | ‘Did Saturnians withstand all attacks by Martians?’ |

| | b. | -O | suiseizin-ga | yarisugosita-nda | yo | | |

| | | -acc | Mercurians-nom | withstood-cop | prt | | |

| | | ‘Mercurians withstood them.’ |

Examples (23) and (24–27) above indicate that ellipsis sites are equipped with full-fledged syntactic structures, leading to the ellipsis sites not being reconstructed via LF-copying.

Incidentally, data from N′-deletion provides further grounds for questioning the LF-copying theory. In their discussion of instances of N′-deletion such as (17a), which I repeat below,

Saito and Murasugi (

1990) argue that the -

no in the pre-ellipsis position is not pronominal:

| (28) | Taro-no | taido-ga | yoi | ippou | Hanako-no | Δ | -ga | yokunai |

| | Taro-gen | attitude-nom | good | while | Hanako-gen | | -nom | not.good |

| | Lit. ‘Taro’s attitude is good while Hanako’s Δ is not good.’ |

| | (adapted from Takita & Goto, 2013, p. 221) |

Building on

Kamio’s (

1983) observation that the pronominal -

no can only replace concrete and not abstract nouns, as shown in (29), Saito and Murasugi conclude that the -

no in (28) functions as a genitive case marker rather than as a pronoun:

| (29) | a. | [katai sinnen-o | motta] | hito |

| | | firmconviction-acc | have | person |

| | | ‘a person with a firm conviction’ |

| | b. | * | [katai no-o motta] hito | (adapted from Saito & Murasugi, 1990, p. 287) |

As suggested by

Kitagawa and Ross (

1982),

Saito et al. (

2008), and others, the insertion rule operates at PF, which suggests that linear order is essential for example (30). However, according to the LF-copying analysis,

no-stranding PSE examples such as the one below appear to be problematic, as they lack any preceding phonetic material in the PF component:

| (31) | a. | Taro-wa | Hati-no | nintaizuyosa-ni | kandousita | no? |

| | | Taro-nom | Hati-gen | patience-gen | impressed | q |

| | | ‘Was Taro impressed by Hati’s patience?’ |

| | b. | -No | tyuuseisin-ni | kandousita-n-dayo |

| | | -gen | loyalty-gen | be.impressed-nml-cop.prt |

| | | ‘He was impressed by Hati’s loyalty.’ |

In (31b), which follows (31a), the sentence-initial genitive case marker does not occur in the environment designated in (30) in the PF component and thus, never satisfies the condition for

no-insertion. The grammaticality of (31b) is therefore unexpected according to the LF-copying theory, as a covertly recovered structure, by definition, lacks phonological content.

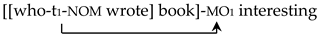

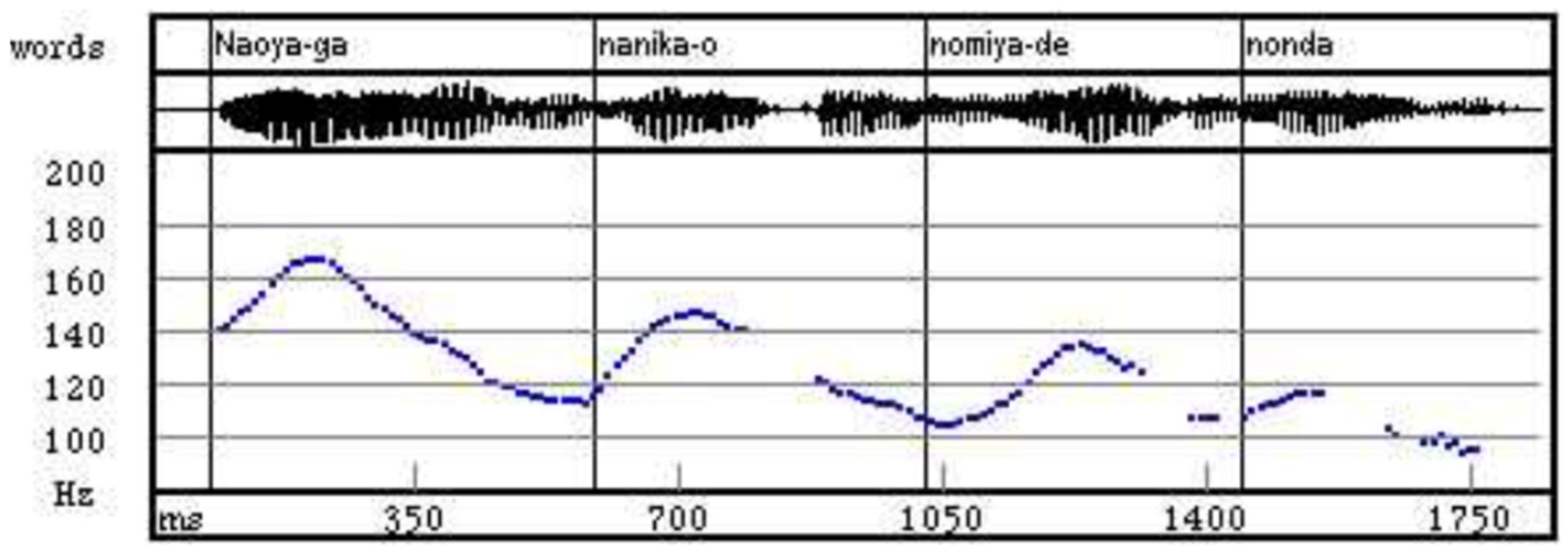

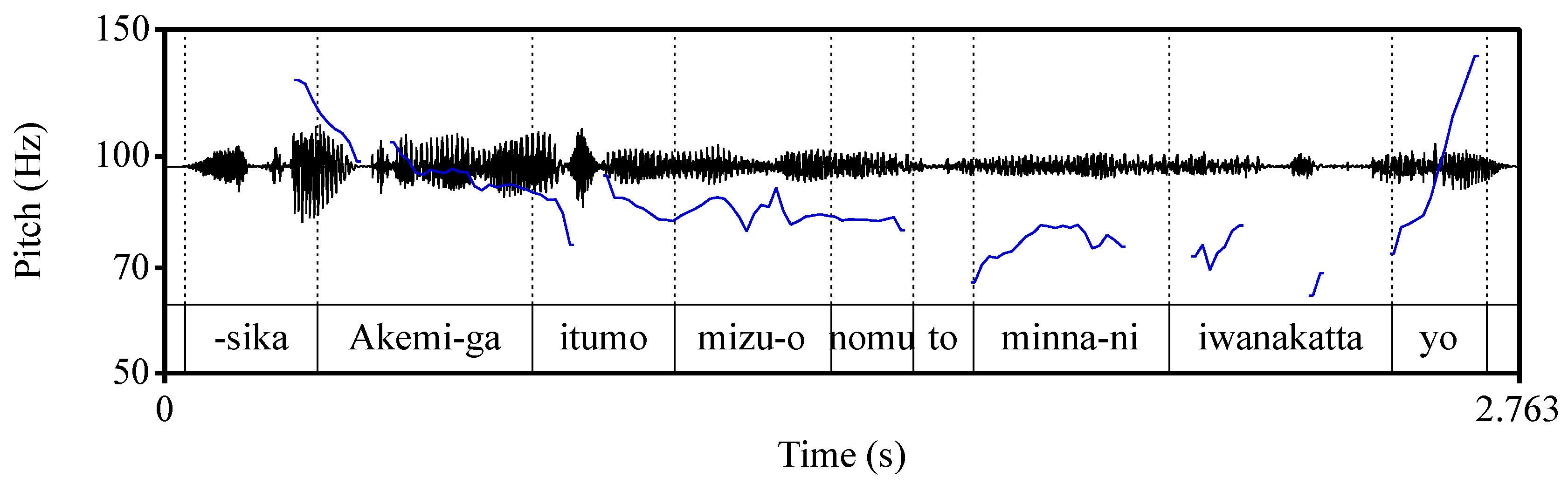

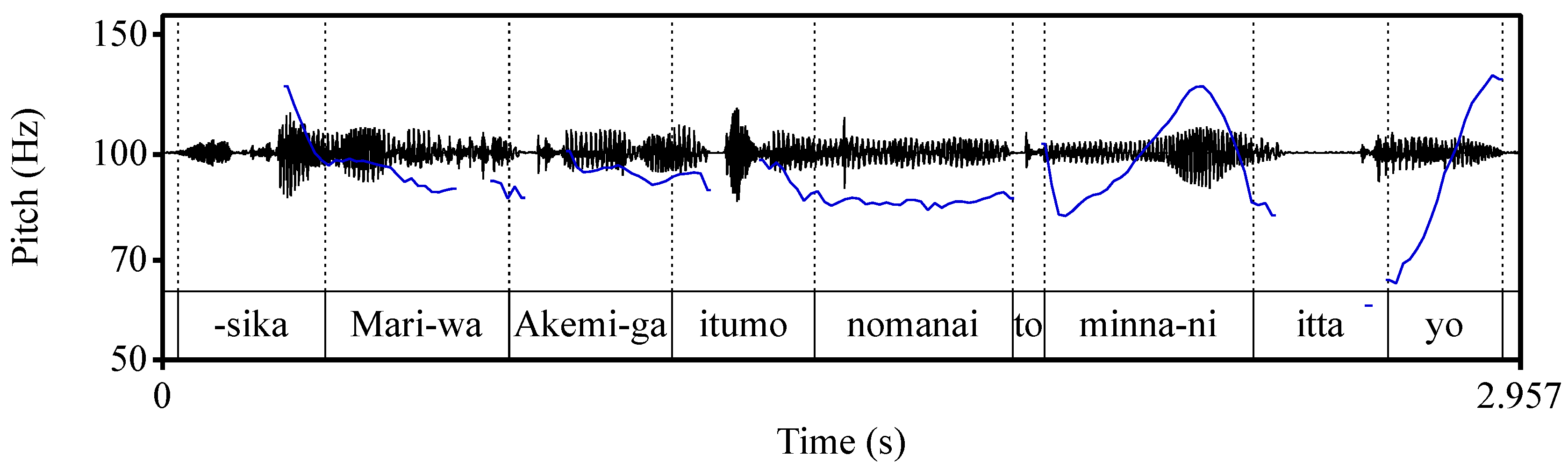

7 3.2. Covert Across-the-Board Movement

An additional challenge to the LF-copying-based analysis of PSE is due to covert ATB movement. Drawing on examples such as (32),

Bošković and Franks (

2000) persuasively argue that such covert movement does not exist in the grammar.

| (32) | a. | Some delegate represented every candidate and nominated every candidate. |

| | b. | * Who said [that John bought what] and [that Peter sold what]? |

| | | (Bošković & Franks, 2000, pp. 113, 110, respectively) |

In (32a), every is not allowed to take wide scope over some, suggesting that covert movement from each conjunct is prohibited. The ungrammaticality of (32b) further demonstrates that what cannot undergo covert ATB extraction from each conjunct, even though English generally permits partial wh-in-situ in multiple wh-questions. Considered together, these examples indicate that covert ATB movement is not a legitimate grammatical option.

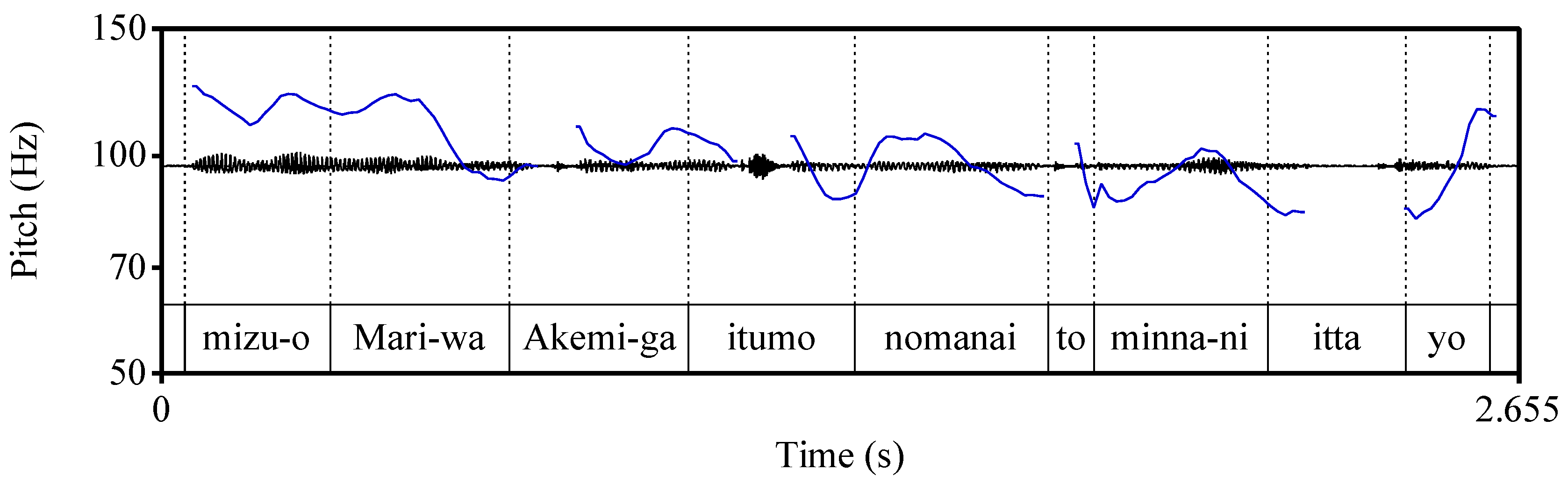

Against this background, we now turn to left-node raising constructions in Japanese, as illustrated in (33a), which represent the mirror image of right-node raising in English (33b). Two sentences are conjoined in such constructions, with their shared object DP (e.g.,

keeki, ‘cake’, in (33a)) being fronted:

| (33) | a. | Keeki-o | John-ga | tukuri, | (sosite) | Mary-ga | tabeta |

| | | cake-acc | John-nom | make | and | Mary-nom | ate |

| | | ‘The cake, John made, and Mary ate.’ |

| | b. | John made, and Mary ate the cake. | (Nakao, 2010, p. 156) |

As

Nakao (

2010) points out, it is logically possible that the ‘shared’ object is not structurally shared; instead, each gap may have a distinct grammatical source: The object in the first conjunct could undergo scrambling, while the second could involve a phonologically null pronoun, options that are freely available in Japanese, as shown in (34):

Although Japanese left-node raising constructions can be reduced to the interaction of scrambling and a phonetically null pronoun in this scenario, Nakao argues that this does not tell the entire story, and proposes that constructions such as (33a) can be better explained by an ATB movement analysis. Let us briefly review her arguments.

Left-node raising constructions are reported to resist case mismatch between the two gap positions, as illustrated in (35).

| (35) | a. | ??Mary-ni | John-ga | hana-o | okuri, | Tom-ga | nagusameta | |

| | | Mary-dat | John-nom | flower-acc | send, | Tom-nom | comforted | |

| | | ‘(To) Mary, John sent a flower, and Tom comforted.’ |

| | b. | ??Mary-o | John-ga | dansu-ni | sasoi, | Tom-ga | raburetaa-o | kaita |

| | | Mary-acc | John-nom | dance-to | invite, | Tom-nom | loveletter-acc | wrote |

| | | ‘(To) Mary, John invited to a dance, and Tom wrote a love letter.’ |

| | | (Nakao, 2010, p. 157) |

In (35a),

okuru, ‘send’, takes a dative object, while

nagusameru, ‘comfort’, takes an accusative one. Similarly, in (35b),

sasou, ‘invite,’ is an accusative-assigning predicate, and

kaku, ‘write’, assigns a dative case. Both examples are degraded. However, as (36) illustrates, null object constructions with the same predicates do not show the same degradation, which points to an important difference from left-node raising constructions:

| (36) | a. | Mary-ni | John-ga | hana-o | okutta. | Tom-wa | pro | nagusameta | |

| | | Mary-dat | John-nom | flower-acc | sent | Tom-top | | comforted | |

| | | ‘John gave a flower to Mary. Tom comforted (her).’ |

| | b. | Mary-o | John-ga | dansu-ni | sasotta. | Tom-wa | pro | rabu | retaa-o | kaita |

| | | Mary-acc | John-nom | dance-to | invited | Tom-top | | love | letter-acc | wrote |

| | | ‘John invited Mary to a dance. Tom wrote a love letter (to her).’ |

| | | (Nakao, 2010, p. 157) |

Another of

Nakao’s (

2010) observations concerns distributive scope. As

Abels (

2004) notes, the shared objects in English right-node raising constructions allow for a distributive interpretation. In particular, (37a), but not (37b), can be interpreted to mean that the song that John sang and the song that Mary recorded were two different songs:

| (37) | a. | John sang, and Mary recorded, two quite different songs. |

| | b. | John sang two quite different songs, and Mary recorded two quite different songs. |

| | | (Abels, 2004, p. 51) |

It is intriguing that left-node raising in Japanese also permits a distributive interpretation. In (38), the shared object

hutatsu-no betsubetsu-no kyoku, ‘two separate songs’, can be interpreted as John sang one song, Mary recorded another, and the two songs were different:

| (38) | Hutatu-no | betubetu-no | kyoku-o | John-ga | utai, | Mary-ga | rokuonsita |

| | two-gen | separate-gen | song-acc | John-nom | sing, | Mary-nom | recorded |

| | ‘Two separate songs, John sang, and Mary recorded.’ | (Nakao, 2010, p. 159) |

Of note, the

pro-occurring counterpart in (39) does not allow for the distributive reading. Consequently, the sentence is interpreted as referring to the same two songs:

8| (39) | Hutatu-no | betubetu-no | kyoku-o | John-ga | utatta. | Mary-ga | pro | rokuonsita |

| | two-gen | separate-gen | song-acc | John-nom | sang | Mary-nom | recorded | |

| | ‘John sang two separate songs. Mary recorded (them).’ | | (Nakao, 2010, p. 159) |

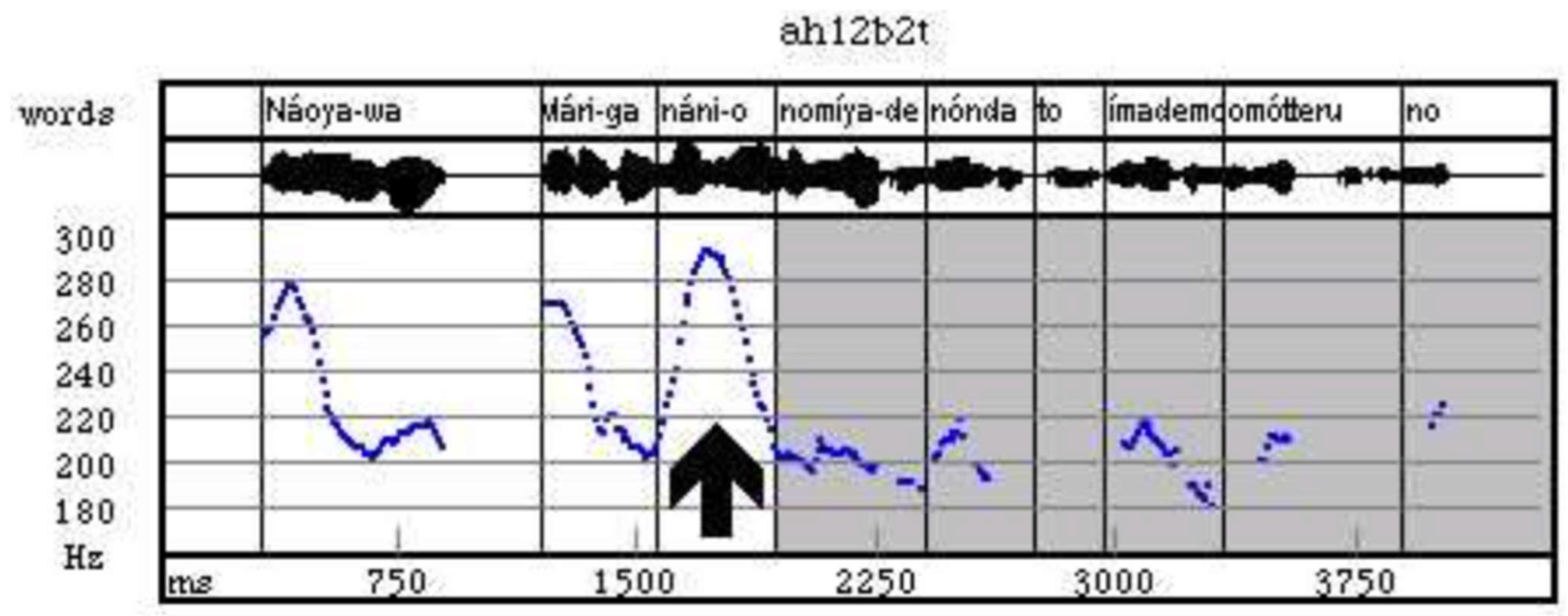

With these observations in mind, Nakao argues that left-node raising constructions are best explained by ATB movement. According to her analysis, the derivation in (40) is assigned to (33a):

| (40) | ![Languages 10 00216 i014 Languages 10 00216 i014]() |

Nakao’s ATB movement analysis finds crosslinguistic support from Polish, in which the ATB movement requires that the case of both gap positions be uniform:

| (41) | a. | Coacc | Jan | lubi | tacc | i | Maria | uwielbia tacc? |

| | | what | Jan | likes | | and | Maria | adores |

| | | ‘What does Jan like and Maria adore?’ |

| | b. | * | Coacc | Jan | lubi | tacc | i | Maria | nienawidzi tgen? |

| | | | what | Jan | likes | | and | Maria | hates |

| | | | ‘What does Jan like and Maria hate?’ | (Citko, 2003, p. 89) |

Bearing

Nakao’s (

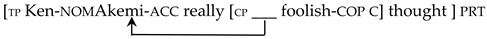

2010) ATB analysis in mind, we now examine (42), in which (42a) is a yes-no question modeled after Nakao’s original example in (33a), and the response is given via PSE in (42b):

| (42) | a. | Keeki-o | John-ga | tukuri, | (sosite) | Mary-ga | tabeta | no? |

| | | cake-acc | John-nom | make | and | Mary-nom | ate | q |

| | | ‘Did John make the cake and Mary eat it?’ |

| | b. | -O | John-ga | tukuri, | (sosite) | Hanako-ga | tabeta(-n-desu) | |

| | | -acc | John-nom | make | and | Hanako-nom | ate-nml-cop | |

| | | ‘John cooked the cake and Hanako ate it.’ |

Given the grammaticality of (42b), the LF-copying analysis must derive it using covert ATB movement, as shown in (43):

| (43) | i. | John-nom cake-acc make, (and) Hanako-nom cake-acc ate(-nml-cop) |

| | ii. | ![Languages 10 00216 i015 Languages 10 00216 i015]() |

After the objects

cake are covertly copied into each relevant position in (43i), they are moved to the sentence-initial position via covert ATB movement in (43ii). However, the derivation goes against the conclusion reached by

Bošković and Franks (

2000), who argue that ATB movement cannot take place covertly.

9In this section, I have shown that the core prediction of the LF-copying theory of PSE (i.e., the ban on overt extraction from a PSE site) is not supported. Furthermore, I have demonstrated that PSE is fully compatible with the ATB environment, contrary to

Bošković and Franks’ (

2000) widely accepted conclusion that ATB movement cannot occur covertly. If the arguments in this section are correct, they significantly undermine the explanatory power of the LF-copying analysis.