Varieties of Polar Question Bias: Lessons from Vietnamese

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Polar Question Constructions in Vietnamese

| (1) | Standard polar questions: | (based on Trinh, 2005, p. 30) |

|

|

| (2) | Particle polar questions: |

| Nó đọc sách { á / à / hả / chăng / ư / sao / nhỉ / … }? he/she read book á à hả … ≈ ‘Does he/she read books?’ | |

| (3) | Tag question: |

| Nó đọc sách phải không? he/she read book correct neg ≈ ‘He/she reads books, does not he/she?’ |

| (4) | Only standard polar questions can be embedded: (based on Trinh, 2005, p. 31) |

|

3. Varieties of Question Bias

3.1. Original Bias

| (5) | Original bias | (definition from B&K, p. 4) |

| A question Q uttered in a context c conveys original bias for a possible answer p iff Q indicates that the prior epistemic state of the speaker in c supports p over . | ||

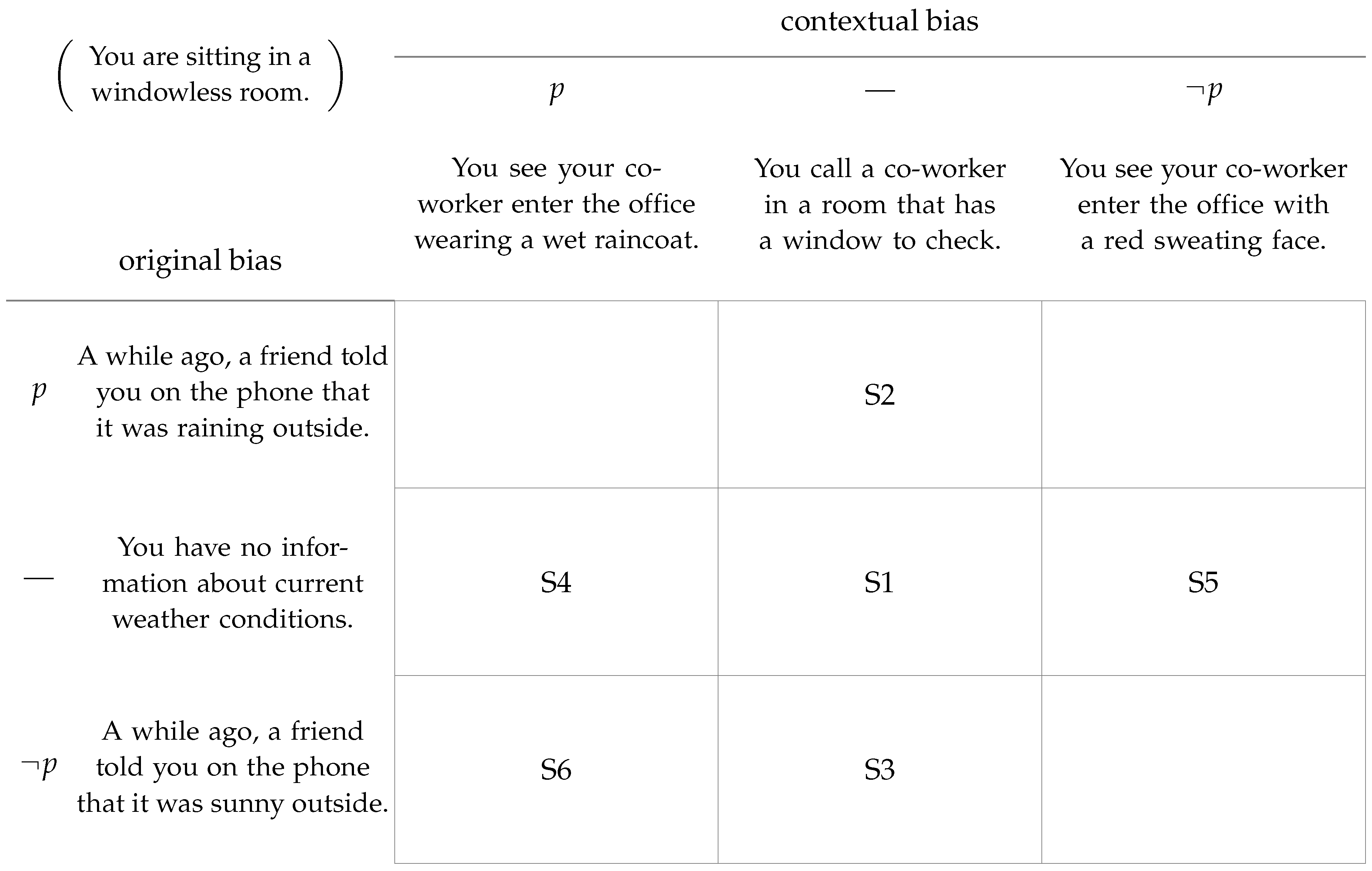

| (S1) | Situation 1: No bias |

| You are sitting in a windowless room with no information about current weather conditions. You call a co-worker in a room that has a window to check on the weather. | |

| (S2) | Situation 2: Original bias for |

| You are sitting in a windowless room. A while ago, a friend told you on the phone that it was rainy outside. You call a co-worker in a room that has a window to check. | |

| (S3) | Situation 3: Original bias for |

| You are sitting in a windowless room. A while ago, a friend told you on the phone that it was sunny outside. You call a co-worker in a room that has a window to check. |

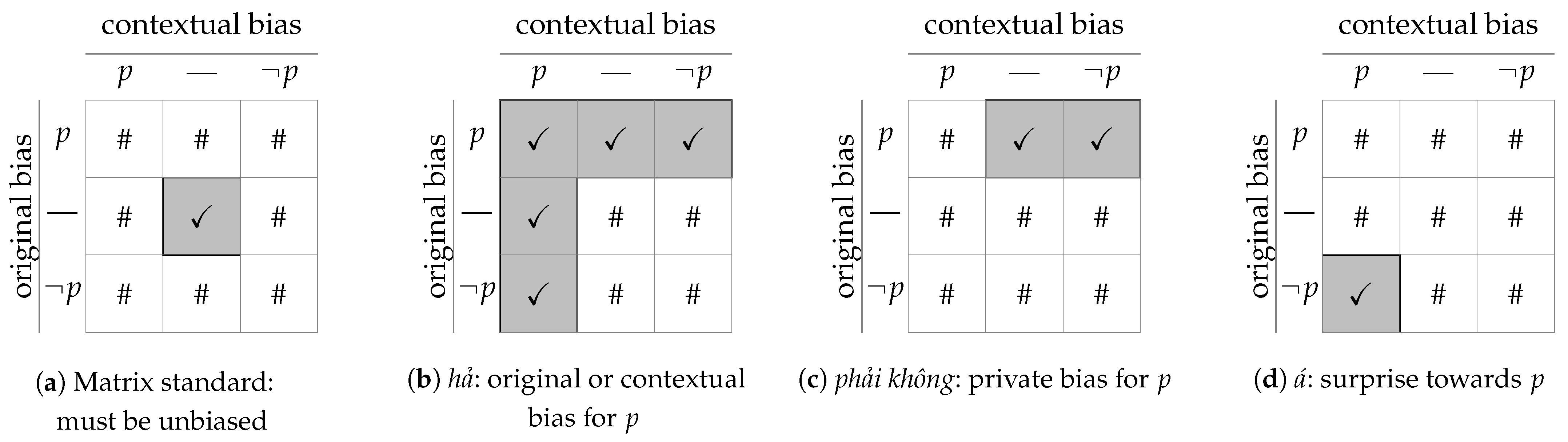

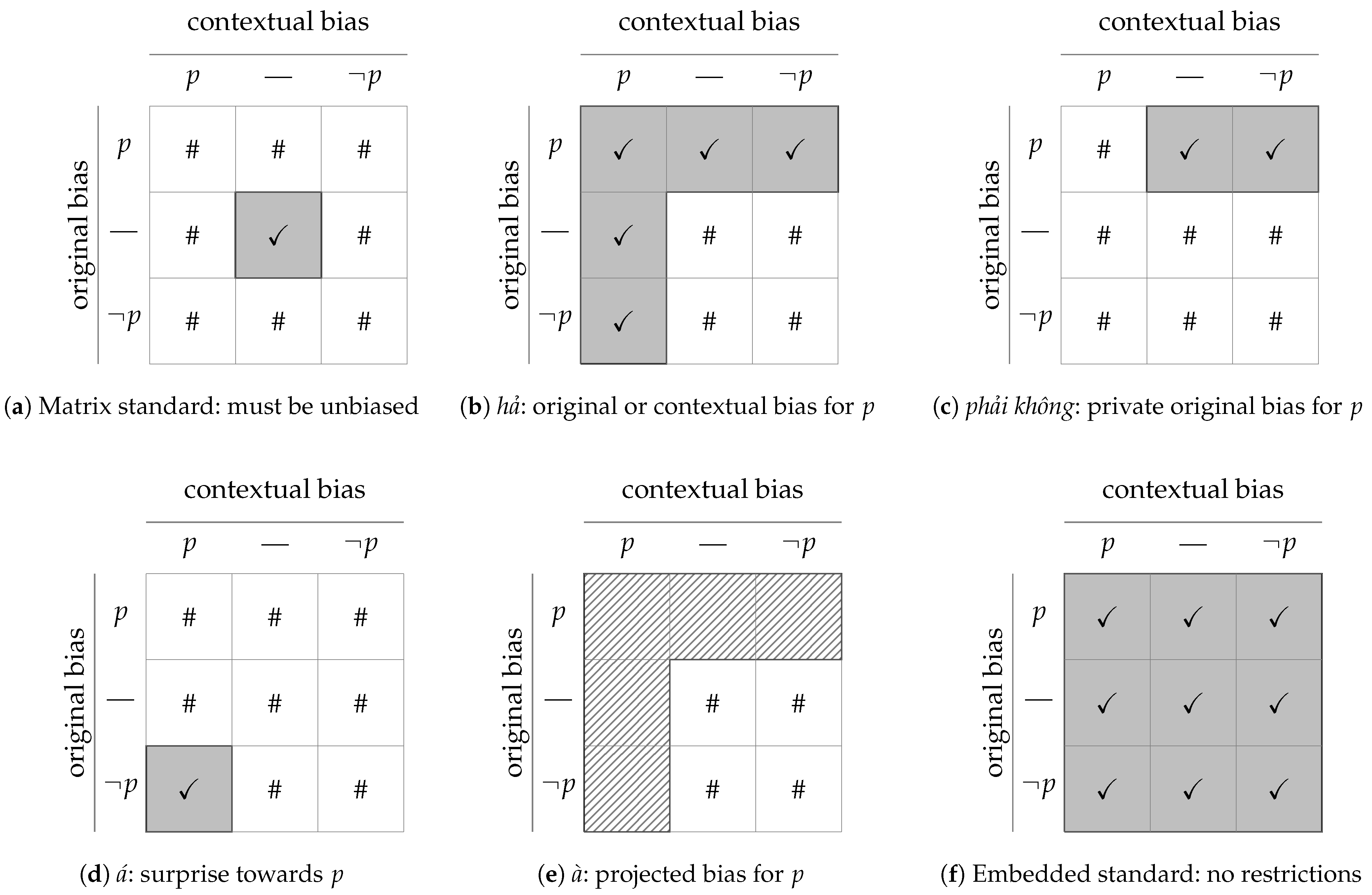

| (6) | Standard question requires no bias: | |

| Trời (có) đang mưa không? it aff prog rain neg ≈ ‘Is it raining?’ | S1 ✓ S2 # S3 # | |

| (7) | Original bias for licenses à and hả particle questions and tag questions: | |

| Trời đang mưa {à / hả / phải không }? it prog rain à hả correct neg ≈ ‘Is it raining?’ | S1 # S2 ✓ S3 # | |

3.2. Contextual Bias

| (8) | Contextual bias | (definition from B&K, p. 4) | |

| A question Q uttered in a context c conveys contextual bias for a possible answer p iff Q indicates that some piece of evidence that has just become available in c supports p over . | |||

| (S4) | Situation 4: Contextual bias for |

| You are sitting in a windowless room. You see your co-worker enter the office wearing a wet raincoat. | |

| (9) | Felicity judgments for question forms in S4, with contextual bias for : |

| Trời đang mưa { #không / ✓à / ✓hả / #phải không }? it prog rain neg à hả correct neg ≈ ‘Is it raining?’ |

| (S5) | Situation 5: Contextual bias for |

| You are sitting in a windowless room. You see your co-worker enter the office with a red sweating face. |

| (S6) | Situation 6: Original bias for and contextual bias for | |

| You are sitting in a windowless room. A while ago, a friend told you on the phone that it was sunny outside. You see your co-worker enter the office with a wet raincoat. | ||

| (10) | Á question requires both original bias for and contextual bias for : | |

| Trời đang mưa á? it prog rain á ≈ ‘Is it raining?’ | S1 # S2 # S3 # S4 # S5 # S6 ✓ | |

3.3. Interim Summary

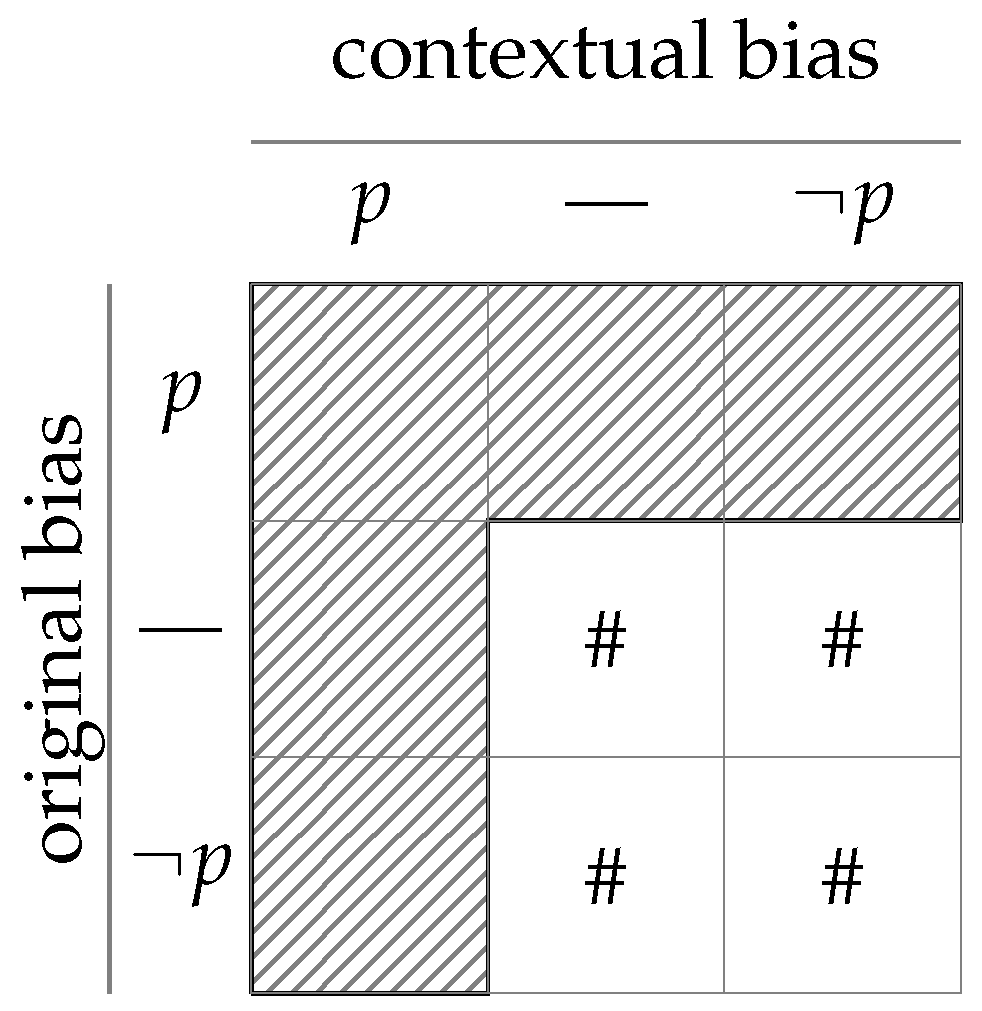

4. Projected Bias and À Questions

| (11) | Projected bias | (definition from B&K, p. 4) |

| A question Q uttered in a context c conveys projected bias for a possible answer p iff Q indicates that the speaker in c expects answer p rather than . | ||

| (12) | Surprised but willing to believe : |

| Minh is a classmate at school. He’s discussed his family before but did not mention any siblings, so you think he’s an only child. Your friend tells you that Minh went to the airport to pick up his (Minh’s) sister. You reply: | |

| Minh có chị { ✓à / ✓á / ✓hả }? Tớ cứ tưởng nó là con một. Minh have sister à á hả I thought he cop only.child ‘Minh has a sister? I thought he’s an only child.’ | |

| (13) | Surprised and unwilling to believe : |

| You and Minh have been friends since grade school, so you have known that he’s an only child. But you have been out of town recently and had not heard that Minh’s parents have adopted a girl. Your friend tells you that Minh went to the airport to pick up his (Minh’s) sister. You reply: | |

| Minh có chị { #à / ✓á / ✓hả }? Không thể nào! Minh have sister à á hả neg possible prt ‘Minh has a sister? That’s impossible!’ |

| (14) | Double-checking context: | (based on Rudin, 2018, p. 37; Rudin, 2022, p. 346) |

| You and your friend made plans two days ago to get drinks tonight. You have not spoken about it since and worry that the friend may have forgotten. | ||

| Chúng ta vẫn đi tối nay { ??à / ✓hả / ✓phải không} 1pl still go tonight à hả correct neg ‘We’re still on for tonight?’ | ||

5. Bias in Embedded Questions

| (15) | Embedded standard question is insensitive to original bias: | |

| You are sitting in a windowless room. | ||

| ||

| You ask your officemate, in the same room as you: Nếu tớ muốn biết [trời có đang mưa không] thì tớ phải hỏi ai? if I want know it aff prog rain neg then I must ask who ‘If I want to know whether it’s raining, who should I ask?’ a ✓ b ✓ c ✓ | ||

| (16) | Embedded standard question is insensitive to contextual bias: | |

| You know Sam wanted to get the first prize in the contest. | ||

| ||

| Nếu tớ muốn biết [Sâm có đạt giải nhất không] thì tớ phải hỏi ai? if I want know Sam aff get prize first neg then I must ask who ‘If I want to know whether Sam got the first prize, who should I ask?’ a ✓ b ✓ c ✓ | ||

6. The Limits of Pragmatic Competition

| (17) | Surprise context supports various question forms: |

| You are sitting in a windowless room. A while ago, a friend told you on the phone that it was sunny outside. You see your co-worker enter the office with a wet raincoat. | |

| ✓ Trời đang mưa { á / à / hả / phải không }? it prog rain á à hả correct neg ≈ ‘Is it raining?’ |

7. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFF | affirmative |

| NEG | negative |

| PROG | progressive |

| PFV | perfective |

| PRT | particle |

| COP | copula |

| B&K | Bill and Koev (2023) |

| 1 | For discussion of the syntax of standard polar questions and their properties, such as the aspect-agreement effect and unavailability of negation, we refer readers to (Trinh, 2005, 2025; Duffield, 2013; Phan & Starke, 2022; Phan, 2024; Trinh et al., 2024; and Liao & Lin, 2024). | ||

| 2 | For instance, à is attributed to Northern and Central dialects (see Tran, 2009, pp. 42–43; Le, 2015, p. 28), whereas Nguyen (1997, p. 240) and Trinh et al. (2024, p. 77), respectively, describe sao and hông as associated with the Saigon dialect (Southern). See also Alves (2012, pp. 9–10), for some discussion of other forms in Central Vietnamese. | ||

| 3 | Embedded standard polar questions can also be introduced by a complementizer liệu (Phan & Starke, 2022, p. 193). | ||

| 4 | Note that the relevant contextual manipulations in S2 and S3 support the plausibility of the speaker having original bias for p or , but do not guarantee it. The speaker may or may not take a particular piece of prior information (here, an earlier report from a friend) to affect their epistemic state with regard to p and . The judgments we report here are for where the manipulations in S2 and S3 do lead to such a relevant change. For speakers who do not take situations S2 and S3 to support a relevant original bias in the speaker’s mind, we expect both situations to pattern with S1 in the felicity of particular question constructions | ||

| 5 | An anonymous reviewer has made the interesting observation that the phải không tag question improves here if the context is changed to S4’ below. The second author shares this judgment.

We suspect that this variant, with no raincoat but wet shoes and spots, opens up the possibility that the addressee is not aware of the relevant evidence. In this case, it does not count as contextual evidence, which Büring and Gunlogson (2000) describe as what “has just become mutually available to the participants in the current discourse situation” (p. 7), clarifying its non-private nature. This information is then instead a source of private evidence for the speaker, and hence, licenses the use of phải không, which is associated with private bias. | ||

| 6 | See also Sudo (2013) for an earlier articulation of the idea that original and contextual bias must be distinguished, based on the behavior of different polar question types in English and Japanese. Note that Sudo (2013) refers to the two notions using the terms epistemic and evidential bias, which are also found in much of the literature. We choose to avoid these terms, because they are both “‘epistemic’ in some broad sense,” as B&K note (p. 6). In their study of different polar question types in Medumba (Grassfields; Cameroon), Keupdjio and Wiltschko (2018) motivated a distinction between bias that tracks information from past versus present situations. From our reading of the facts there, it appears that Keupdjio and Wiltschko’s (2018) discussion of past- versus present-oriented bias is another statement of the original versus contextual bias distinction here. We thank Harold Torrence for bringing this work to our attention. | ||

| 7 | Domanesci et al. (2017) and Šimík (forthcoming) have employed a similar mode of presentation for the bias profiles of different polar question strategies, considering nine possible situations that cross three values each of original bias and contextual bias, for English and German and for Serbian and Czech, respectively. | ||

| 8 | Adopting the notion of projected bias may also allow for a reanalysis of cases in the literature that have been described as making conventional reference to the “strength” of biases, i.e., distinguishing between strong vs. weak bias of a particular type. See for example (Oshima, 2017; Keupdjio & Wiltschko, 2018; and Bill & Koev, 2023). Such apparent strength distinctions could perhaps instead be described in terms of the alignment between one form of bias and the overall projected bias. For instance, what these prior works describe as “strong” contextual bias for p may refer to the combination of contextual bias for p as well as projected bias for p, whereas “weak” contextual bias for p may describe situations with contextual bias for p but without projected bias for p, which would have to be due to perceived unreliability of the contextual evidence or the presence of conflicting information. We leave the full exploration of this possibility open for future work. | ||

| 9 | For situations with negative original or contextual bias, the speaker can instead use a particle or tag question built from the negation of p (as these question forms allow negation in their prejacent, unlike standard questions), or else another proposition q that is contextually equivalent or similar to . See the end of Section 3 for discussion of this point. | ||

| 10 | The unembeddability of particle and tag questions may in fact be related to their conventionalized bias. In her discussion of the articulated left periphery of interrogatives, Dayal (forthcoming) discussed English rising declaratives and similar biased polar questions in other languages and proposes that biased questions necessarily involve the outermost possible projection of questions, called the Speech Act Phrase (SAP; see also Speas & Tenny, 2003), which cannot be embedded. Phan (2024) also located a number of unembeddable sentence-final particles in Vietnamese in SAP. We leave the more detailed analysis of Vietnamese particle and tag questions and their unembeddability for future work. |

References

- Alves, M. J. (2012). Notes on grammatical vocabulary in Central Vietnamese. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bill, C., & Koev, T. (2023). Question bias. Available online: https://www.corybill.com/publications/BillKoev2023may.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Büring, D., & Gunlogson, C. (2000). Aren’t positive and negative polar questions the same? [Unpublished manuscript]. Available online: https://urresearch.rochester.edu/fileDownloadForInstitutionalItem.action?itemId=1347&itemFileId=1635 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Dayal, V. (Forthcoming). The interrogative left periphery: How a clause becomes a question. Linguistic Inquiry. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domanesci, F., Romero, M., & Braun, B. (2017). Bias in polar questions: Evidence from English and German production experiments. Glossa, 2(26), 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Duffield, N. (2013). Head-first: On the head-initiality of Vietnamese clauses. In D. Hole, & E. Löbel (Eds.), Linguistics of Vietnamese: An international survey (pp. 127–154). de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Goodhue, D. (2022). Isn’t there more than one way to bias a polar question? Natural Language Semantics, 30, 379–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunlogson, C. (2001). True to form: Rising and falling declaratives as questions in English [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of California Santa Cruz.

- Jeong, S. (2018). Intonation and sentence type conventions: Two types of rising declaratives. Journal of Semantics, 35, 305–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keupdjio, H., & Wiltschko, M. (2018). Polar questions in bamileke medumba. Journal of West African Languages, 45(2), 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Krifka, M. (2015). Bias in commitment space semantics: Declarative questions, negated quetions, and question tags. Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory, 25, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, D. R. (1981). A first look at the semantics and pragmatics of negative questions and tag questions. Proceedings of the Chicago Linguistic Society, 17, 164–171. [Google Scholar]

- Le, G. H. (2015). Vietnamese sentence-final particles [Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Southern California.

- Liao, Y.-L. I., & Lin, T.-H. J. (2024). The left-peripheral nature of the right-edge particle không in Vietnamese. Taiwan Journal of Linguistics, 22(1), 115–133. [Google Scholar]

- Malamud, S. A., & Stephenson, T. (2015). Three ways to avoid commitments: Declarative force modifiers in the conversational scoreboard. Journal of Semantics, 32, 275–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D. H. (1997). Vietnamese: Tiếng Việt Không Son Phấn. London Oriental and African Language Library. [Google Scholar]

- Oshima, D. Y. (2017). Remarks on epistemically biased questions. Proceedings of the Pacific Asia Conference on Language, Information and Computation, 31, 169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, T. (2024). Where two ends meet: Non-at-issue meanings on the syntactic treetops of Vietnamese [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. National Tsing Hua University.

- Phan, T., & Starke, M. (2022). Yes-no questions and Vietnamese clause structure. Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, 15(4), 192–211. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, M. (2024). Biased polar questions. Annual Review of Linguistics, 10, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, D. (2018). Rising above commitment [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of California Santa Cruz.

- Rudin, D. (2022). Intonational commitments. Journal of Semantics, 39, 339–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speas, P., & Tenny, C. (2003). Configurational properties of point of view roles. In A. M. Di Sciullo (Ed.), Asymmetry in grammar, volume 1: Syntax and semantics (pp. 315–344). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Sudo, Y. (2013). Biased polar questions in English and Japanese. In D. Gutzmann, & H.-M. Gärtner (Eds.), Beyond expressives: Explorations in use-conditional meaning (pp. 275–295). Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Šimík, R. (Forthcoming). Polar question semantics and bias: Lessons from Slavic/Czech. In B. Gehrke, & R. Šimík (Eds.), Topics in the semantics of Slavic languages. Language Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, T. (2009). Wh-quantification in Vietnamese [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Delaware.

- Trinh, T. (2005). Aspects of clause structure in Vietnamese [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Humboldt University.

- Trinh, T. (2010, June 10–11). Asking with assertions. Program of the 20th SEALS Meeting, Zürich, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, T. (2025). Partition by exhaustification and polar questions in Vietnamese. Languages, 10(9), 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T., Phan, T., & Vu, D. N. (2024). Negation and polar questions in Vietnamese: Present and past. Taiwan Journal of Linguistics, 22(1), 67–88. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Erlewine, M.Y.; Nguyen, A. Varieties of Polar Question Bias: Lessons from Vietnamese. Languages 2025, 10, 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090238

Erlewine MY, Nguyen A. Varieties of Polar Question Bias: Lessons from Vietnamese. Languages. 2025; 10(9):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090238

Chicago/Turabian StyleErlewine, Michael Yoshitaka, and Anne Nguyen. 2025. "Varieties of Polar Question Bias: Lessons from Vietnamese" Languages 10, no. 9: 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090238

APA StyleErlewine, M. Y., & Nguyen, A. (2025). Varieties of Polar Question Bias: Lessons from Vietnamese. Languages, 10(9), 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10090238