1. Introduction

While numerous studies in the subfield of L2 sociolinguistics exist that address how L2 learners perceive specific regional, stylistic, and socially variable language use in L1 speech (

Chappell & Kanwit, 2022;

Del Saz, 2019;

Escalante, 2018;

Schmidt, 2018,

2020;

Schmidt & Geeslin, 2022), few to none have examined learners’ perception of the same forms in L2 speech. Research on attitudes towards sociolinguistic variation use by L2 learners has also focused almost exclusively on L1 judges (

DuBois, 2023;

Ruivivar & Collins, 2018;

Swacker, 1976). Why examine L2 attitudes towards the adoption of variation by their peers? To gain insight into why (and, often, why not) learners ultimately adopt variable and nonstandard speech forms (Type II variation) in the L2 and because perception by L1 speakers and L2 peers can impact learners’ access to input and therefore their language acquisition (

Geeslin, 2020). Studies have found that students are more likely to adopt regional speech forms according to factors like socializing with L1 speakers in the target language (

Pope, 2016;

Ringer-Hilfinger, 2012;

Trentman, 2013), exposure to regional variation (

Geeslin & Gudmestad, 2008;

Rehner et al., 2003;

Trentman, 2017), learner identity (

George & Hoffman-González, 2019;

Lybeck, 2002;

Raish, 2015), and attitudes towards the culture associated with a target variety (

Kinginger, 2004;

Schmidt, 2020). The present study examines another facet of the story of L2 sociolinguistic acquisition: the perceptions of the peer group. It also aims to further the understanding in the field that L2 learners abroad and in the classroom are their own speech community, with identities that differ from those of L1 speakers such that taking “native-like” variation rates as the target for acquisition may be problematic.

The present study will examine learner perceptions of L1 and L2 speech with coda [s] and /s/ deletion to determine L2 attitudes towards use of this highly variable cue by both populations. In Spanish, /s/ weakening is a widespread cue that occurs to some degree in many varieties, often carrying regional, social, and stylistic meaning. It is the production of /s/, usually in syllable-final or word-final position, not as the standard sibilant [s] but as a reduced variant, for instance, as aspirated [h] or fully lenited (/s/ deletion).

1.1. Sociolinguistic Awareness and Beliefs Among L2 Speakers

For classroom learners, most forms of variable language use will fall outside of the standard classroom varieties used by their instructors in the context of formal language learning (

Li, 2010,

2014;

Mougeon et al., 2004), in which prescriptivism emphasizes the importance of using correct, socially appropriate, and prestigious speech forms (

Lefkowitz & Hedgcock, 2006;

Mougeon et al., 2010). The instructor as a model of preferred or prestigious speech in the eyes of students was confirmed by

Lefkowitz and Hedgcock (

2006), who found that most high school and college students consider their instructor to be an “excellent” model of the accurate, desirable standard for speech in the L2. Regarding regional variation,

George (

2014) found that students were more likely to adopt a regional variant when their instructor used said variant in class.

Rehner and Mougeon (

1999) also found evidence of adoption of nonstandard variants by L2 French immersion students, although the standard variant was still favored by participants.

Research has shown that exposure to variation in the L2, usually through study abroad, is one of the main factors that predicts learners’ production of social and dialectal variation (

Kinginger & Blattner, 2009;

Pozzi & Bayley, 2021;

Regan et al., 2009;

Trentman, 2013,

2017), and yet adoption of regional cues is far from ubiquitous, even among study abroad participants (

Geeslin & Gudmestad, 2008;

George & Hoffman-González, 2019;

Ringer-Hilfinger, 2012). Furthermore, many classroom learners, especially those at the lower levels, may only be exposed to significant dialect variation when they come into contact with L1 speakers outside of the traditional classroom setting, in completing assignments that require them to speak with or listen to L1 speakers, or through the use of real-world materials in the language classroom. This lack of exposure is likely one of the main reasons why the production of regional variants is less common among classroom learners than among those who study abroad (

Geeslin & Gudmestad, 2008;

Sax, 2003).

Although it may not lead to production, explicit instruction on sociolinguistic variation still impacts learner awareness about variants and their meanings in the L2 (

Beaulieu et al., 2018;

Chappell & Kanwit, 2022;

Schmidt, 2018;

van Compernolle & Williams, 2013). Additionally, L2 learners with varying degrees of proficiency and experience have been found to connect specific accents and language use with social attributes, like prestige and social status (

Chappell & Kanwit, 2022;

Fernández-Mallat & Carey, 2017;

Michalski, 2023;

Schmidt & Geeslin, 2022). For instance,

Schmidt and Geeslin (

2022) examined the language attitudes held by L2 learners of Spanish towards four regional dialects, specifically measuring their evaluations of native speech in terms of solidarity (kindness) and standardness (prestige). While kindness was found to be similar across levels, students showed growth with proficiency primarily in their prestige associations, with advanced learners differentiating more in the prestige they attributed to Puerto Rican, Mexican, Argentine, and Castilian Spanish.

Chappell and Kanwit (

2022) also examined learner perceptions, using a matched-guise methodology that specifically targeted coda /s/ productions as either /s/ or [h] in native speech from Puerto Rico and Mexico. Participants were L1 speakers of English learning Spanish at multiple levels, and they evaluated the speech samples in terms of status, confidence, and solidarity. The results revealed that advanced learners who had completed a phonetics course were more likely to recognize stimuli with /s/ weakening as being from the Caribbean and that advanced learners who had studied abroad in /s/ aspirating regions were more likely to connect coda /s/ with status. This seems to suggest that perhaps only more proficient and experienced students in the present study will associate prestige with coda /s/ production.

1.2. Perceptions and Attitudes Towards L2 Speech

The ideology that language learners should learn prestigious, prescriptively correct varieties and the low rates of adoption of socially or stylistically variable structures and cues by classroom learners could be related to negative perspectives and bias against L2 speakers who use nonstandard speech forms in their second language (

DuBois, 2023;

Ruivivar & Collins, 2018;

Swacker, 1976).

Swacker (

1976) performed a study in which L1 English speakers heard native and nonnative American English spoken with and without a strong East-Texas accent and grammatical markers. The speech was evaluated according to personality traits, with the native voices receiving positive evaluations and the nonnative voice with the regional speech cues being assessed most negatively, as having little education and sense of humor, and as being untrustworthy and poorly informed.

DuBois (

2023) also examined L1 attitudes towards stylistic variation in L2 speech, specifically the use of nonstandard lexical items on ratings of speaker linguistic proficiency, status, and solidarity. Participants were L1 speakers of Peninsular Spanish evaluating the speech of L1 and L2 Spanish speakers. The results showed that both groups were rated lower in status when using colloquial language, with worse ratings given to L2 speakers. Furthermore, while the L1 speakers received higher ratings for solidarity with colloquial speech, L2 speakers were rated similarly in this category regardless of the register they used. No difference was observed in ratings of linguistic proficiency.

Other studies have shown more positive attitudes towards L2 speakers’ use of socially variable language. For example,

Beaulieu (

2016) used a matched-guise experiment to gauge the attitudes of elderly L1 French patients towards stylistic variation in the speech of L2 French speaking nurses. Patients heard recordings of nurse–patient interactions that included phonological, grammatical, and lexical differences representing formal and informal speech styles and then completed an interview about their attitudes towards the caregiver in each. The majority of participants experienced the nurses as aloof, cold, and authoritative when they used the formal guise and warm, kind, and trustworthy when they used the informal guise.

George (

2017) examined the judgments of L1 Spanish speakers from Spain who rated the degree of foreign accent of L1 and L2 speech, investigating the impact of regional speech cues on degree of foreign accent. She asked native listeners to explain their ratings of L2 speech and found that nontarget-like productions were cited more in speech receiving higher (more foreign accented) ratings, while regional cue productions were cited more in speech receiving lower (less foreign accented) ratings. These findings suggest that the use of regional cues may make L2 speech sound less foreign accented.

Learners themselves have been found to hold somewhat stigmatized views of the speech of their peers, although most studies have not explicitly examined the adoption of regional and variable speech forms and whether L2 speakers assess them according to social values. Studies in this area have generally involved foreign accent, finding that learners assess the nativeness of their peers’ speech more critically than L1 speakers do (

Elliott, 1995;

Fayer & Krasinski, 1987;

Flege, 1988;

Munro et al., 2006;

Schoonmaker-Gates, 2015). In one study,

Hanson and Schoonmaker-Gates (

2025) examined the social values that L2 speakers attributed to the use of /θ/ by L2 speakers. The study examined L1 and L2 Spanish listeners’ evaluations of the status (intelligence), solidarity (kindness), and nativeness of L2 speech with /s/ or with /θ/. The findings revealed that L2 listeners rated L2 speech as more intelligent with /s/ than with /θ/, but the opposite was true of L1 listeners. Ultimately, the study suggests that learners may evaluate their peers’ adoption of regional variants in unexpected ways that differ from how the speech cues sound to L1 speakers.

1.3. /s/ Weakening as a Phonetic and Social Phenomenon

Sociophonetic cues are those that vary regionally, socially, and stylistically. Some, like Spanish /θ/ or [ʒ]/[ʃ], are used near-categorically in certain regions, while others, like /s/ weakening in Spanish, are widespread across the Spanish-speaking world but used at different rates and with different social meanings depending on the region, the speaker, and the communicative context. In Spanish, /s/ weakening is a common sociophonetic phenomenon that occurs primarily in informal registers (

Lipski, 2005).

Hualde (

2013) notes that /s/ weakening varies sociolinguistically both within and across speakers in most dialects, with broader use in the Caribbean and coastal regions of the Spanish-speaking world. According to

Núñez-Méndez (

2022), social factors that have been linked to /s/ weakening include gender, with males producing higher rates of /s/ reduction than females, age (with different trends depending on the dialect), and education level, with greater /s/ weakening among less educated speakers and in rural areas.

Phonetically, this variable cue occurs when the voiceless sibilant fricative [s] is produced as aspiration [h], glottal stop [ʔ], or full deletion. This phenomenon usually occurs in word-final or syllable-final (word medial) positions, with some dialects showing a reduction in word initial positions, as well (

Brown & Torres Cacoullos, 2002). Rather than occurring as a dichotomy of presence or absence of sibilance, recent phonetics research has shown that /s/ weakening in Spanish is realized to varying degrees that can range from full sibilant production, to aspiration, to full elision (

Núñez-Méndez, 2022), with instances of glottalization or deletion occurring primarily in the Caribbean (

Dohotaru, 1998;

Tellado González, 2007;

Valentín-Márquez, 2006). In the Andalusian Spanish of southern Spain, /s/ weakening also occurs after voiceless stops preceded by /s/, a phenomenon known as post-aspiration (

Torreira, 2012), which is particularly prominent among young people in Western Andalusia (

Cronenberg et al., 2020).

Unlike many regional variants in Spanish, /s/ weakening can lead to morphosyntactic and lexical convergence when it occurs, for instance, in second and third person singular verbs (i.e., second person “comes” “

you eat” and third person “come” “

he/she eats” and in minimal pairs, such as “pescado” “

fish” and “pecado” “

sin”). Because it varies stylistically rather than categorically, /s/ weakening may occur less in the speech directed at language learners, especially those at lower proficiency levels. Furthermore, because it usually occurs in syllable-final and word-final positions, it may be less salient to learners in the input they hear than other regional variants (

Redford & Diehl, 1999). Research shows that some learners may erroneously associate /s/ aspiration with a phoneme other than /s/ (

Escalante, 2018;

Schmidt, 2018), and the ability to accurately encode the feature improves with exposure and proficiency (

Del Saz, 2019;

Escalante, 2018;

Schmidt, 2018,

2020). When learners hear /s/ deletion, they may not encode it as the lexical item or verb form their interlocutor intended, causing additional comprehension challenges.

Studies on /s/ weakening in L2 Spanish speakers have found that the cue is not usually adopted in L2 speech (

Geeslin & Gudmestad, 2008;

Núñez-Méndez, 2022), probably due to its highly variable, informal nature, the stigma that may be attached to it in certain varieties and spaces, and its absence from learner-directed speech. When language learners do use it, it may not be clear to their interlocutors whether it is an instance of nontarget-like lexical or morphosyntactic errors (type 1 variation) or the use of a variant that occurs in L1 speech (type 2 variation) (

Adamson & Regan, 1991). Learners may also be hesitant to use /s/ weakening if they are worried about it violating the prescriptive rules of the formal morphosyntax that many have learned in classroom settings, and if interlocutors do not expect stylistic or regional variation in the speech of L2 learners, their audience may have trouble understanding their language use.

The research questions that guided the present study are as follows:

Does /s/ deletion in L1 Spanish impact L2 listeners’ perceptions of status (educated), solidarity (kindness), and nativelike pronunciation?

Does /s/ deletion in L2 Spanish impact L2 listeners’ perceptions of status (educated), solidarity (kindness), and nativelike pronunciation?

2. Materials and Methods

The present study examines the attitudes of 30 L2 learners of Spanish towards L1 and L2 speech in Spanish with and without coda /s/ production. Participants were

N = 15 L1 English speakers enrolled in lower-level (first and second semester) undergraduate college Spanish classes and

N = 15 L1 English speakers enrolled in advanced-level (sixth semester and beyond) undergraduate college Spanish classes. Lower-level learners were primarily taking the class to fulfill the institutional language requirement and did not have intentions to continue academically with the language. Their age of first exposure to Spanish ranged from 6 to 21 years old, with a mean of 13.6 and a mode of 13. Their ages at the time of participation ranged from 18 to 21, with an average of 19.3. Eight identified as women, and seven as men. None of the learners in the lower-level courses reported having studied abroad in a Spanish-speaking country. Although it is unlikely that instructors exhibited /s/ weakening in novice-level classrooms (e.g.,

Li, 2010,

2014), most (

N = 9) reported past and present exposure to instructors from the United States, with 4 exposed to instructors from locations with low to moderate rates of /s/ weakening (Central Spain, Costa Rica, and Inland South America) and 2 exposed to instructors from locations where /s/ weakening is more frequent (1 instructor each from Uruguay, Puerto Rico, and El Salvador) (

Lipski, 2005).

The

N = 15 upper-level learners were all majors and minors in Spanish taking the class for credit towards their degree and, unlike the lower-level learners, motivated by long-term language goals to use the language during study abroad experiences and in their communities and professional lives after graduation. Although all identified English as their native language and did not report learning Spanish from family or friends in their home environment growing up, their age of first exposure to Spanish ranged from 2 to 17 years old, with a mean of 9.9 and a mode of 13. Their ages at the time of participation ranged from 18 to 22 (all but three were 21), with a mean of 20.7. Thirteen of the upper-level learners identified as women, and two as men. Eight of the upper-level participants had studied abroad for one semester of college (four months) prior to participating, with five in Seville (which is in the Western Andalusian region of southern Spain, where /s/ aspiration is common and post-aspiration occurs) and three in Barcelona (which is in northern Spain, where /s/ aspiration is less common than in southern Spain or certain Latin American varieties) (

Núñez-Méndez, 2022). In general, the upper-level learners reported exposure to more regional varieties through their past and present instructors than the lower-level learners. Nine reported exposure to instructors from locations with low to moderate rates of /s/ weakening (Central Spain, Costa Rica, and Inland South America), and six reported exposure to instructors from locations with higher rates of /s/ weakening (Central America, the Caribbean, the Southern Cone, and Southern Spain). That being said, most of the exposure had occurred at the college level, and only one instructor they mentioned from the Southern Cone (Argentina) spoke with /s/ weakening even in the pedagogical setting.

Participants completed four tasks. The first was a background questionnaire about prior experience learning and speaking Spanish, studying abroad, and past and present exposure to regional varieties through the media and contact with L1 speakers of Spanish. The questionnaire included extensive information about the specific regions of the Spanish participants had been exposed to, including where their past instructors were from, where (if at all) they had studied abroad, and where any L1 Spanish-speaking friends, family, or acquaintances were from. The background questionnaire was followed by three perception tasks.

The stimulus participants heard was speech elicited via a sentence reading task completed by 8 L1 English speakers, 4 women and 4 men, all enrolled in lower-level (first and second year) college classes in Spanish. The read speech of 4 L1 Spanish speakers, 2 women and 2 men, was also used. They were international graduate students who had grown up in central and northern Spain and were residing in the United States at the time of the recording. Their read speech did not have any naturally occurring instances of /s/ weakening. Each of the 12 speakers was recorded reading the following utterances: “El polo norte no está en Cuba” “The North Pole is not in Cuba,” “A ti te gustan las tapas” “You like the tapas,” and “No hay pumas en la costa” “There are no pumas on the coast.” Recordings were made in a sound-proof room using a head-mounted Shure microphone and a USB Pre audio interface connected to a computer with CoolEdit software version 2.0. Each experimental sentence was read multiple times by the speaker, and the best of the recordings was used.

Two manipulated versions of each utterance were created using Praat, one that resulted in a reduction of the [s] production and one that created distractors that were 15% faster than the original utterance. The /s/ was reduced by using the “view and edit” feature in Praat to identify the segment of the spectrogram that corresponded with the frication of each coda /s/, beginning where the periodicity ended on the wave form prior to frication and ending where the dark bar corresponding with the fricative ended on the top of the spectrogram. None of the /s/ segments had been aspirated, so the beginning and end of each was clear. After identifying and selecting the /s/ on the spectrogram, Praat’s manipulation tool was used to reduce all wave activity and frication to zero while maintaining the timings, essentially replacing the fricative with an equal period of silence. This form of manipulation was meant to give the semblance of /s/ deletion without introducing anything new into the manipulated speech signal that listeners might use to distinguish it from the unmanipulated version. It was also deemed better than inserting a period of silence because it avoided a clipped insertion effect and kept all elements of the speech and wave form the same across both versions. That said, this manipulation was not meant to be a perfect match of naturally occurring /s/ weakening, as elision (deletion) would not have maintained the same timings and /s/ aspiration would have involved an initial period of turbulent noise characteristic of the production of a glottal fricative [h]. Naturally, an additional goal of this study was to determine whether the speech modification sounded enough like /s/ deletion to be a valid methodology. Because L1 speech with /s/ manipulation was rated as equally nativelike as L1 speech with the original coda /s/, and because L2 speech with /s/ manipulation was ultimately perceived as more nativelike than the same speech with coda [s], the manipulations were deemed to sound sufficiently natural to be used. Future studies may wish to manipulate the duration of the /s/ segment further, perhaps creating a range from full /s/ production to full deletion (reducing the /s/ without maintaining the timings).

Speech rate manipulation was performed using Praat’s overlap-add feature to change the duration of the entire utterance by a specific percentage (in this case, 85% of the duration of the original). The overlap-add feature removes overlapping segments to manipulate duration without noticeably impacting specific speech cues. The resulting faster utterances were used as distractors, such that a third of the utterances heard were unmanipulated, a third were manipulated with coda /s/ frication removed, and a third were manipulated in the entire duration of the utterance.

Participants heard a total of 108 utterances (12 speakers × 3 sentences × 3 versions = 108). The utterances were divided into three blocks of 36 items each in Qualtrics and took participants between 15 and 20 min to complete in total. Participants were encouraged to work at their own pace and take breaks as needed to avoid fatigue. Although it is possible that participant fatigue may have occurred, it would have impacted the third block that addressed “kindness.” The first block examined how native-like the speech sounded, the second block examined the perceived education level of the speaker, and the third block examined the perceived kindness of the speaker. Each block contained all three versions of a given sentence spoken by a specific speaker (the original, the utterance with modified /s/ frication, and the utterance with modified duration) for comparison purposes, as each block examined a different attitude. Each block contained 36 items, with 12 produced by L1 Spanish speakers and 24 items produced by L2 Spanish speakers. Within each block, all utterances appeared in a randomized order. After hearing each item, in the first task, participants responded to the question “How close to native Spanish is the pronunciation of the phrase?” using a 7-point scale that ranged from “Not at all close to native Spanish (1)” to “Very close to native Spanish (7).” In the second task, participants heard each item and responded to the question “How educated does the person sound?” using a 7-point scale ranging from “Not at all educated (1)” to “Very educated (7).” In the final task, participants heard each item and responded to the question “How kind does the person sound?” using a 7-point scale ranging from “Not at all kind (1)” to “Very kind (7).”

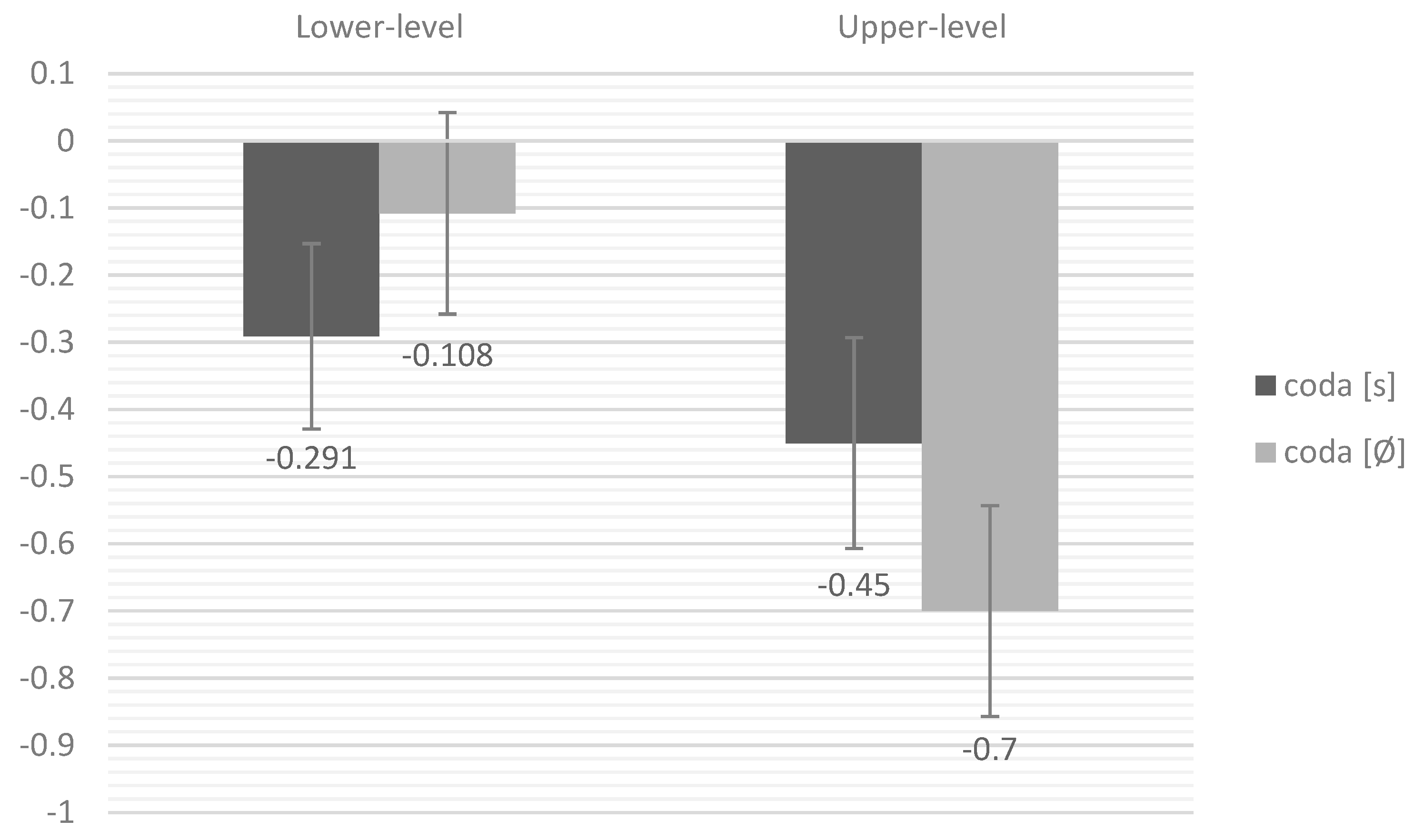

Following

Chappell and Kanwit (

2022), after data collection, participant answers on the 7-point scale were centered such that 0 was the middle point of each and the numbers ranged from −3 to +3. This did not change the statistical analysis, but it was done to make clear where the mean attitudes fell on the scale between the two extremes. This meant that negative numbers fell on the negative end of their respective scale (“not at educated,” “not at all close to native”) and positive numbers on the positive end of the respective scale (“very educated,” “very close to native.”).

In order to answer the research questions, differences between each participant’s rating of the original utterance and the same exact utterance (spoken by the same person) with /s/ modification were calculated. This allowed for a mean difference for each participant and across participants to be found for each block (how native-like the person sounded, how educated the person sounded, and how kind the person sounded). To examine whether participants rated speech differently with coda [s] and coda [Ø], mixed-effects linear regression models were run for each of the following dependent variables: (a) status (not at all educated/very educated), (b) solidarity (not at all kind/very kind), and (c) native-like pronunciation (not at all close to native/very close to native). The independent variables tested in each model were variant ([s] or [Ø]) and enrollment level (lower-level or upper-level), which were both categorical fixed effects, and participant and sentence, which were random effects.

4. Discussion

Participants rated L1 speech from Spain as significantly less educated with coda [Ø] than with coda [s] in the speech samples. This was regardless of learner level, as the interaction effect between variant and level was not significant, which could mean that both lower-level and upper-level learners are sensitive to the social meaning attached to /s/ deletion in Spanish and that minimal exposure is required for learners to develop attitudes towards this type of widespread variant.

Schmidt and Geeslin (

2022) and

Michalski (

2023) both found that even lower-level L2 learner perceptions patterned with more advanced participants in rating certain varieties or guises lower for prestige than others. In both cases, upper-level learners also showed some important signs of development in

Schmidt and Geeslin (

2022) by distinguishing additional dialects and in

Michalski (

2023) with trends that started to resemble those of native listeners. While it may be that certain sociolinguistic phenomena and norms are so ubiquitous in the target language that even novice level learners pick up on them through real-world exposure to music and media, other explanations seem warranted, such as, for instance, if students are drawing on their established L1 sociolinguistic attitudes or learned L2 classroom ideologies.

For instance, it is possible that learners in the present study were not responding to the question of status (how educated the speaker sounded) as a social phenomenon but in terms of how prescriptively “correct” the speech was based on their prior academic experience. As discussed earlier, in speaking with L2 learners, instructors and native speakers likely will not employ stylistic and socially stigmatized (in some regions) variants like /s/ weakening in their interactions with learners, especially those with limited proficiency (

Li, 2010,

2014;

Mougeon et al., 2004,

2010). In the formal language learning setting, most learners develop a sense of the standard prestigious prototype for speaking the L2 (

Lefkowitz & Hedgcock, 2006), against which, in the absence of social experience or direction, less experienced learners might compare L1 speech in this type of task. If the speech stimuli sounded different from what the learners were accustomed to, taught explicitly, or heard in the speech of their instructors, they may have been more prone to deem that language use as sounding less educated simply because it sounded less prototypical, prescriptively correct, or accurate. As learners become more advanced and are exposed to more sources of the L2, their ability to suspend the prescriptive ideology appears to grow, as found by

Solon and Kanwit (

2022), who reported that L2 learner preference for less prototypical, intervocalic /d/ deletion increased with proficiency.

Interestingly, the learners did not rate L1 speech with coda [s] and coda [Ø] differently in terms of how close to native it sounded, perhaps because this was experienced as a different dimension for them than how prescriptively “correct” the speech and speaker sounded.

Castellanos (

1980) found that L1 speakers of Spanish from multiple varieties rated native speech samples from the Caribbean (Puerto Rico, Cuba, and coastal Venezuela) as significantly “less correct” than native speech samples from regions where retention of /s/ and other consonants is more common (Mexico, Bolivia, and Peru). In that study, listener ratings that measured status (socioeconomic class, education level, racial identity) were also found to be significantly lower for the samples from the Caribbean than for the samples from non-Caribbean regions. While the present study did not separate perceptions of linguistic accuracy from perceptions of social status, it is possible that L2 learners might have converged the two due to a lack of social knowledge about Spanish sociolinguistic norms. This seems especially likely due to the familiarity of the concept of “perceived correctness” for students (which

Lefkowitz & Hedgcock, 2006, confirmed) and because the only measure used to evaluate status was education level. Furthermore, in each task, participants responded to L1 and L2 speech presented in a randomized order, and, in the context of L2 speech, the question of education level in Spanish might in fact be interpreted as prescriptive correctness or adherence to an educational standard ideology rather than prestige and social status.

Schmidt and Geeslin (

2022) measured prestige in terms of perceived intelligence and wealth rather than education, using both the words “prestige” and “standardness” to refer to this same category, which suggests that the two are sometimes conflated.

Hanson and Schoonmaker-Gates (

2025) performed a study similar to the present one to gauge L2 learners’ perception of their peers’ adoption of /θ/, a variant used in Castilian Spanish, also measuring status in terms of intelligence. The results of that study found that lower-level L2 learners rated L2 speech with /θ/ as less intelligent than speech without /θ/, while L1 listeners from outside of Spain showed the opposite trend. The authors suggest that learners may have rated speech differently because they were reacting to /θ/ as they would to a lisp in their L1 (English), with inherent bias (

Aronson, 1973). These findings could suggest that beginning-level learners may draw on their existing L1 sociolinguistic knowledge or attitudes (

Ladegaard, 1998;

Wirtz & Ender, 2025), especially in assessing unfamiliar L2 phenomena. This seems possible in the present study in which /s/ deletion was equated with lower prestige if participants were influenced by L1 sociolinguistic stereotypes they held. The deletion of third person singular and possessive /s/ is a characteristic of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) (e.g.,

Labov, 1972;

Thomas, 2007), and discrimination and bias against speakers of this variety are well-established in sociolinguistics research (e.g.,

Lippi-Green, 1997;

Purnell et al., 1999).

Regarding learner ratings of L2 speech, variant was found to be a significant predictor of how native-like the speech sounded to L2 learners, as items with coda [s] sounded less native-like and items with coda [Ø] sounded more native-like to participants. This suggests that when L2 learners adopt regional variants, their speech may sound more native-like to their peers than learner speech without those variants. This confirms what was previously found by

George (

2017) for L1 listeners and by

Hanson and Schoonmaker-Gates (

2025) for L2 listeners, that the presence of regional variants in learner speech appears to lessen the degree of foreign accent perceived by interlocutors. The present study extends the previous findings to L2 perception, as well, as

Hanson and Schoonmaker-Gates (

2025) only found this to be the case in ratings given to a single L2 speaker whose speech was rated as more foreign accented than the L2 speakers in that study.

One possible explanation for this may be that the presence of certain regional sounds draws attention away from or lessens the severity of other nonnative-like sounds or intonations present in foreign accented speech, impacting how accented it sounds. Studies abound that examine how speech perception is significantly impacted by listener beliefs about the speech and the speaker (e.g.,

Casasanto, 2008;

Niedzielski, 1999), and it seems possible that the presence of regional cues could elicit certain expectations that the pronunciation will be more native-like than if the cues were not present.

The present findings also do not find evidence that L2 listeners hold the same attitudes that L1 listeners do towards learner speech with nonstandard forms. For instance, L2 listeners in the present study did not deem the speech of their peers with /s/ deletion to sound kinder (

Beaulieu, 2016), lower in status (

DuBois, 2023), or less educated (

Swacker, 1976) than speech with coda [s]. It is also possible that ratings of L1 speech but not L2 speech varied in terms of status with coda [s] and coda [Ø] for the reasons listed above, that learner speech is judged in the classroom along the prescriptively correct and incorrect continuum and not in terms of status or social appropriateness.

Although variant did not significantly predict perceptions of status in L2 speech, the interaction of variant and level approached significance, with upper-level learners rating L2 speech with the same trend that that they showed for L1 speech ratings, with coda [Ø] sounding less educated than coda [s]. Lower-level learners diverged from this, rating coda /s/ as less educated than coda [Ø] in learner speech, a trend that resembled participants’ general ratings of how native-like the L2 speech sounded. Although it did not reach significance, this could be a preliminary indication that more experienced, proficient learners might be more prone to draw on their sociolinguistic knowledge, connecting /s/ weakening with lower status even in L2 speech. As discussed above, less proficient learners, perhaps due to a lack of experience or knowledge about social norms in Spanish, may have conflated the measures of status (education) and native-like production. Numerous previous studies (

Chappell & Kanwit, 2022;

Michalski, 2023;

Schmidt & Geeslin, 2022) have confirmed that learners hold sociolinguistic attitudes in their assessments of L1 speech, with differences resulting from proficiency and past experience. The present findings could indicate that while learners do rate L1 speech with coda [s] and coda [Ø] differently in terms of status, they do not transfer that sociolinguistic knowledge as readily to the evaluation of learner speech.

Listeners may not waiver much in their ratings of status for L2 speakers due to internalized bias against foreign accented speech (

Gluszek & Dovidio, 2010;

Lambert, 1967;

Lippi-Green, 1997) if regional variants go largely unnoticed in learner speech as a result of strong foreign accents that draw listeners’ attention and guide their assessments. It is also possible that because learners are primarily taught more formal, academic speech and judged in the language classroom in terms of prescriptive language use and correctness, their concept of learner identity may not be associated with regional cues the way L1 speaker identity is (

Lefkowitz & Hedgcock, 2006). For this reason, classroom learners might be less uniform or less able to judge the speech of their peers in terms of measures with social meaning attached to them, like status, if they project this view of L2 identity on the speakers they are rating. This also calls into question whether the L1 speech community and “native-like” or even bilingual variation rates should be taken as the target for L2 learners acquiring sociolinguistic competence, or if the language classroom and L2 speakers abroad should be viewed as their own unique speech communities, as suggested by the literature on L2 varieties (

Bolton & Kwok, 1990;

Lefkowitz & Hedgcock, 2006;

Li, 2010;

Lybeck, 2002;

Norton, 2000). This aligns with recent arguments in the field that critically question the “native speaker” model for determining linguistic competence (

Grammon & Babel, 2024).

5. Conclusions

The present study found evidence that L2 listeners rate L1 speech differently for “status” and L2 speech differently for “nativeness” according to the presence and absence of syllable-final [s]. These findings suggest that when using socially marked features of the target language, L2 speakers are perceived differently from L1 speakers by their L2 peers. These findings could have implications for learners who choose to adopt regional variants in the target language, leading them to sound more nativelike to peers and potentially impacting their access to real-world practice as members of the L2 speech community.

This research has clear limitations, including the fact that the stimuli used were not naturally occurring and furthermore were samples of read speech, which does not usually undergo /s/ weakening or deletion. Hearing an informal variant in a context in which it would not normally be expected could lead speech to sound less nativelike to listeners. Additional research is needed to determine how naturally occurring speech stimuli are rated by listeners. This study also did not include L1 listener participants, and so it was limited in its ability to compare L1 and L2 perceptions, relying solely on the previous literature for this. However, in L2 dialect acquisition, often, L1 standards cannot and should not be used as a target for L2 speakers, whose identity and experiences will surely impact the use and perception of sociolinguistic variants in ways that are fundamentally different from L1 speakers. Predicting or expecting similar rates of use by both populations, especially when L1 perceptions will vary based on the specific speech community, would seem to violate basic sociolinguistic principles, as L1 and L2 group memberships are identity measures that must be accounted for rather than overlooked.

Finally, it is likely that the findings presented here have somewhat limited applicability to regional variation in general, as they may be variant-specific. Because /s/ weakening is an especially widespread and flexible phenomenon in Spanish that is not limited to one region, context, or socioeconomic status, the same L1 speaker may vary in the degree and frequency of their production depending on audience, content communicated, and context, making it an especially challenging variant for learners to master and understand. Therefore, additional study is needed to determine the impact of dialectal and stylistic variation on L2 peer perceptions. Even so, this research suggests that L2 learners may not attribute the same social values to L2 speech that they do to L1 speech and that even learners lacking experience with sociophonetic cues or sociolinguistic instruction may use their existing knowledge or bias in assessing speech in the target language, be it as the result of newly developed L2 attitudes, learned classroom ideologies, or from existing L1 sociolinguistic bias. The findings from this study are useful for anyone learning a second language who is interested in how their pronunciation, especially the adoption of regional and socially variable cues, might impact the way they are perceived by their peers, which could ultimately affect their access to input and, consequently, their L2 acquisition.