Reformulation in Early 20th Century Substandard Italian

Abstract

1. Introduction: A Pragmatic–Diachronic Study of Italian in the Early 20th Century

2. A Brief Account of Italiano Popolare

- Orthographic deviations, graphic inconsistencies (graphemics);

- Geographic markedness, simplification of clusters (phonetics);

- Malapropisms, reanalysis of derivational morphemes (lexicon and word formation);

- Reduced paradigms, analogical generalization or deletion of markers (morphosyntax);

- Redundancy, underspecification of connectivity relations (textuality).

3. The Di Raimondo Correspondence (DRC)

- Documents and Edition

- Timeframe and Location

- Writers

- Authorship and Scribal Mediation

4. Reformulation and Its Markers in Italian

5. Reformulation Markers in Italiano Popolare

5.1. Cioè

- (1)

- vi fo sapere che parllo peri la mia sfoltuna, ciove dela mia leceza‘I’ll let you know that I’m talking about my bad luck, that is, about my leave’

- (2)

- il grano ancora non l’ho trebiato cioè non l’ho ancora pisato‘I haven’t threshed the wheat yet, that is, I haven’t trodden it’

5.2. Anzi

- (3)

- caro sogero, io credo che sono stato ubidiente sempre apresso a voi e sempre spero esere, anzi meglio‘dear father-in-law, I believe I have always been obedient to you, and I hope I always will be so, well, [even] better’

- (4)

- mi hai scritto 24 lettere, ed io invece ne ho ricevute 4 che subito ti ho risposto, anzi senza riceverne io ti ho scrito‘You wrote me 24 letters, and I received four instead, to which I replied straight away, well, without receiving any I wrote to you’

- (5)

- io subito ti scrivo perché mi o madato a prendere il tuo derizio, anze ti facio sapere che stanno tutti bene di saluti‘I’m writing as I’ve asked for your address, well, I’ll let you know that everyone is fine’

5.3. Vuol Dire

- (6)

- Che io, adopo 18 mese che non vengo, a leceza mi apartene, e se non mi la tano mi fano cozimare a me, la vito ala lirbità. Perché dopo 40 mese di campagna mi fano cueso parllare, oldire che se uno che ave bona volondà di fare il sirivizio per cuesto campia peziero, oldire a 60 mese che facio il soldato, l’ho fato e oro se non mi mandono ce pezo io a fare cuello che faceno a me. Basta, termino [...]‘After 18 months of not coming [home], the leave belongs to me, and if they don’t give it to me, they’ll consume me, my life to freedom. Because after 40 months of campaigning they say such things, I mean, if one who has the good will to do [military] service then he changes his mind, I mean, I’ve been a soldier for 60 months, I did it, and now if they don’t send me [on leave] I’ll do to them what they are doing to me. Enough, I conclude’

- (7)

- Maruza o capito che faceste 3 tomele di formendi e non di potevito calare ordire che mage asai e sei molto grosa. Ma tu non puoi imaginarite cuale disiderio lo mio cuore e le mie ochie di vidirite, ma pacenza‘Maruzza, I see that you made three tomoli [around 50 kg] of wheat and you couldn’t bend over, this means that you eat a lot and you’re very fat. But you can’t imagine how much my heart and my eyes long to see you, but this can’t be helped’

6. Discussion

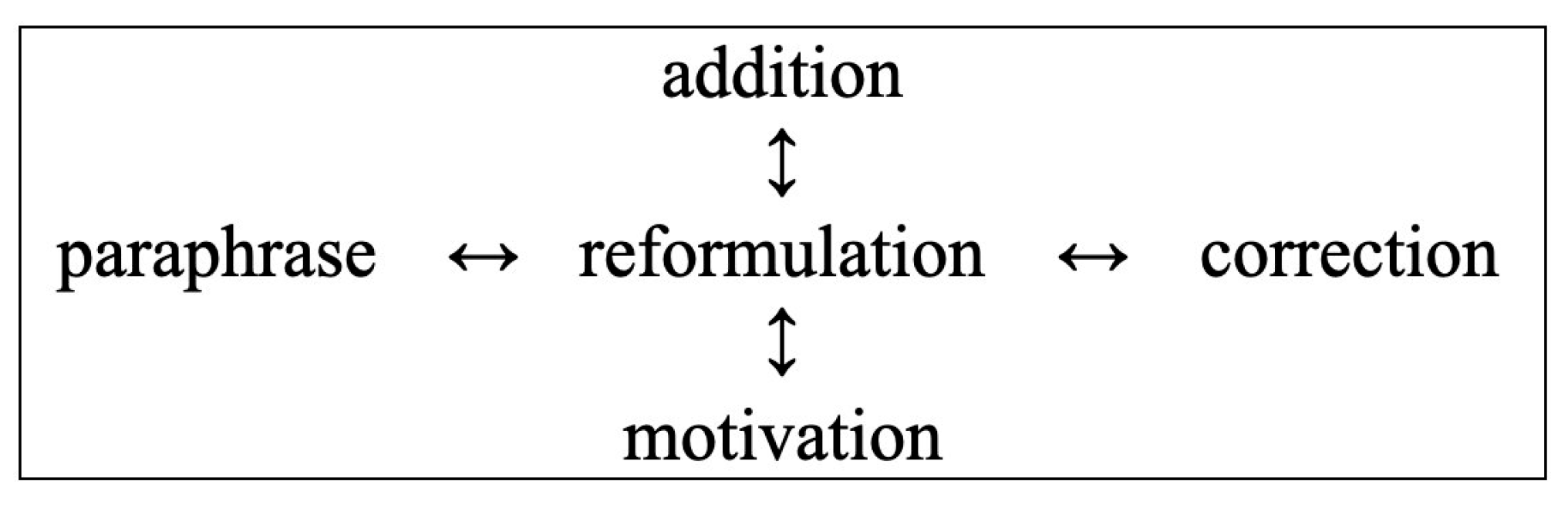

6.1. A Semantic-Pragmatic Map for Reformulation

6.2. Reformulation in the Continuum from Orality to Writing

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In the Italian context, the notion of dialect refers to Italo-Romance varieties, that is, languages that evolved from Latin in the Italian peninsula. Since the early standardization of Tuscan in the 16th century (then acknowledged as ‘Italian’), Italo-Romance languages like Sicilian have been non-standard or vernacular varieties, as far as they have been roofed by Italian as the Standard variety in a diglossic repertoire. |

| 2 | All editorial interventions are needed to ensure readability (while the fully faithful transcription–the diplomatic edition–is available in Scivoletto, 2024, pp. 363–431): (1) capitalization has been adjusted in accordance with orthographic conventions, including the so-called reverential uses (where the capital letter is intended to show respect to the very concept the word refers to), as well as more or less arbitrary ones. (2) punctuation—where present in the original text–has been preserved. Additional commas and periods have been added or adjusted, to clarify the structure of the text. (3) word boundaries are restored, when writers misspell them. In some cases, integrations and adjustments are necessary (e.g., ifamiglia > in famiglia; avvoi > a voi); (4) in the edited collection (Scivoletto, 2024), additions and adjustments are signaled in italics. In fact, in a few cases words or fragments have been added to help readers recognize a word, and sometimes to reconstruct passages (thanks to contextual or intertextual information that is not explicit in the very text) that otherwise would remain totally opaque; (5) repeated words or fragments have been eliminated, that are duplicated merely due to graphic disfluency; (6) graphic accents in polysyllabic words are restored, to clarify otherwise opaque oxytones (e.g., lirbita > lirbità, for It. libertà ‘freedom’); the case of ciove and giove (for cioè) is excluded, as far as this is a central topic of the present study and thus analyzed in detail; (7) abbreviations are spelled out (e.g., Rgg > reggimento ‘regiment’); (8) missing parts of the text (eroded, torn, or faded) are indicated by three dots in square brackets. For a more detailed discussion and exemplification, cf. Scivoletto (2024, pp. 25–30). |

| 3 | The notion of discourse structuring markers refers to “connectors that allow the speaker/writer (SP/W) to signal what relationship they wish the addressee/reader (AD/R) to deduce from the linking of discourse segments in a non-subordinate way” (Traugott, 2022, p. 4). |

| 4 | A good example is Sicilian bì, a marker that is used exactly to invalidate a mistaken segment of talk and correct it: e.g., a mmia u psicolugu, bì u psicolugu, u ddietolugu mi rissi [...] ‘my psychologist, oh, not my psychologist, my dietician told me [...]’ (Scivoletto, 2023, p. 196). Recently, Mereu and Dal Negro (2025, p. 7) have described the same corrective construction with cioè in Italian. |

| 5 | The occurrences are found in the following texts from the collection (Scivoletto, 2024): T5 (i), T6 (ii, iii), T35 (iv), T111 (v), T124 (vi), T173 (vii), T201 (viii, ix), T102 (x), T3 (xi), T169 (xii), T111 (xiii, xiv), T150 (xv). |

| 6 | I wish to thank an insightful anonymous reviewer for suggesting me to elaborate on the limited inventory of reformulators, on its implications in a diachronic perspective, and on the influence of scribal mediation–as discussed in what follows. |

| 7 | The lexical form is termed hybrid (cf. Regis, 2016; Scivoletto, 2024, pp. 186–203) to the extent that the two codes (Italian and Sicilian) are mixed inside the wordform. In fact, the past participle pisa-to is made of the Sicilian root of the verb pisari (‘to thread’) and the Italian inflectional morpheme -to (Sicilian morpheme being -tu). |

| 8 | In using reformulation (and, above all, in reiterating this use), the pedagogic aim may be seen clearer if we understand wartime semi-literate letter writing as an instance of community of practice, based precisely on the shared effort to acquire both writing as a communicative tool and Italian as a linguistic code. This reflection, which falls outside the scope of this paper, is sketched in Scivoletto (2024, pp. 178–180, 321–325). |

| 9 | The distinction between orality and writing is intended here in the classical sense of Koch and Oesterreicher (1985), that is, in terms of Medium as well as Konzeption: the difference does not lie in the mere channel or mode of communication (phonic vs. graphic) but involves the distinction between the language of immediacy vs. distance (cf. also Briz, 2010 on the informal-conversational vs. formal distinction). The complex blend of oral and scriptural features in epistulary writing–in addition to this case of italiano popolare (already discussed in Scivoletto, 2023)–has been examined in letters from the Spanish Civil War by Pardo Llibrer (2025, and this issue). |

| 10 | This assumption is commonplace in the research that has focused on written texts of italiano popolare (cf. Berruto, 1987). A recent analysis that deconstructs this assumption is provided by Herbst (2022). A more detailed discussion on the topic is in Scivoletto (2024, pp. 325–330). |

References

- Alfonzetti, G. (2017). Introduction. Sociolinguistic research in Italy: A general outline. Sociolinguistic Studies, 11(2–4), 237–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antos, G. (1982). Grundlagen einer theorie des formulierens. Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzanella, C. (1986). I connettivi di correzione nel parlato: Usi metatestuali e fatici. In K. Lichem, E. Mara, & S. Knaller (Eds.), Parallela 2. Aspetti della sintassi dell’italiano contemporaneo (pp. 35–45). Narr. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzanella, C. (1995). I segnali discorsivi. In L. Renzi, G. Salvi, & A. Cardinaletti (Eds.), Grande grammatica italiana di consultazione (Vol. I, pp. 225–257). Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Bazzanella, C. (2003). Dal latino ante all’italiano anzi: La ‘deriva modale’. In A. Garcea (Ed.), Colloquia absentium. Studi sulla comunicazione epistolare in Cicerone (pp. 123–140). Rosenberg. [Google Scholar]

- Bergs, A. T. (2004). Letters. A new approach to text typology. Journal of Historical Pragmatics, 5(2), 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berretta, M. (1984). Connettivi testuali in italiano e pianificazione del discorso. In L. Coveri (Ed.), Linguistica testuale. Atti del XXII Congresso della Società di Linguistica Italiana (pp. 237–254). Bulzoni. [Google Scholar]

- Berruto, G. (1987). Sociolinguistica dell’italiano contemporaneo. Nuova Italia Scientifica. [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore, D. (1993). The relevance of reformulations. Language and Literature, 2(2), 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briz, A. (2010). El registro como centro de la variedad situacional. Esbozo de la propuesta del grupo Val.Es.Co. sobre las variedades diafásicas. In I. Fonte, & L. Rodríguez (Eds.), Perspectivas dialógicas en estudios del lenguaje (pp. 21–56). UANL. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, J. K. (2004). Dynamic typology and vernacular universals. In B. Kortmann (Ed.), Dialectology meets typology. Dialect grammar from a cross-linguistic perspective (pp. 127–145). Mouton de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Ciabarri, F. (2013). Italian reformulation markers: A study on spoken and written language. In C. Bolly, & L. Degand (Eds.), Across the line of speech and writing variation. Corpora and language in use—Proceedings 2 (pp. 113–127). Presses Universitaires de Louvain. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca, M. J. (2003). Two ways to reformulate: A contrastive analysis of reformulation markers. Journal of Pragmatics, 35(7), 1069–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, M. J., & Bach, C. (2007). Contrasting the form and use of reformulation markers. Discourse Studies, 9, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Achille, P. (1990). Sintassi del parlato e tradizione scritta della lingua italiana. Analisi di testi dalle origini al secolo XVIII. Bonacci. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Negro, S., & Fiorentini, I. (2014). Reformulation in bilingual speech: Italian cioè in German and Ladin. Journal of Pragmatics, 74, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mauro, T. (1970). Storia linguistica dell’Italia unita. Laterza. [Google Scholar]

- del Saz Rubio, M. M., & Fraser, B. (2003). Reformulation in English [Unpublished manuscript]. Available online: http://people.bu.edu/bfraser/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Elspass, S. (2012). The use of private letters and diaries in sociolinguistic investigation. In J. M. Hernández-Campoy, & J. C. Conde-Silvestre (Eds.), The handbook of historical sociolinguistics (pp. 156–169). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, A. (2014). Linguistica del testo. Principi, fenomeni, strutture. Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari, A. (2022). Il testo scritto tra coerenza e coesione. Franco Cesati. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentini, I., & Sansò, A. (2017). Reformulation markers and their functions: Two case studies from Italian. Journal of Pragmatics, 120, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzmaurice, S. M. (2002). The familiar letter in early modern english: A pragmatic approach. Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Flores Acuña, E. (2009). La reformulación del discurso en español en comparación con el italiano. In M. P. Garcés Gómez (Ed.), La reformulación del discurso en español en comparación con otras lenguas (pp. 93–136). Universidad Carlos III y Boletín Oficial de Estado. [Google Scholar]

- Geddo, C. (2023). Parafrasare, ripetere, riformulare: Il caso di cioè/ce nel parlato contemporaneo. In D. Mastrantonio, I. G. M. Abdelsayed, M. Marrucci, M. Bellinzona, O. Paris, & V. Bianchi (Eds.), Repetita iuvant, perseverare diabolicum. Un approccio multidisciplinare alla ripetizione (pp. 57–69). Edizioni Università per Stranieri di Siena. [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi, C. (2022). Vagueness markers in Italian: Age variation and pragmatic change. FrancoAngeli. [Google Scholar]

- Gülich, E., & Kotschi, T. (1983). Les marqueurs de reformulation paraphrastique. Cahiers de Linguistique Française, 5, 305–351. [Google Scholar]

- Gülich, E., & Kotschi, T. (1995). Discourse production in oral communication. In U. M. Quasthoff (Ed.), Aspects of oral communication (pp. 30–66). de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, A. (2022). Textualität im italienischen nonstandard. Distanzsprachliche kompetenz und textkonstituierende verfahren in autobiographischen texten aus dem 20. Jahrhundert. De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Hobsbawm, E. (1994). The age of extremes: The short twentieth century, 1914–1991. Pantheon. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, P., & Oesterreicher, P. (1985). Sprache der nähe, Sprache der Distanz. Mündlichkeit und Schriftlichkeit im Spannungsfeld von Sprachteorie und Sprachgeschichte. Romanistiches Jahrbuch, 36, 15–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzotti, E. (1999). Spiegazione, riformulazione, correzione, alternativa: Sulla semantica di alcuni tipi e segnali di parafrasi. In L. Lumbelli, & B. Mortara Garavelli (Eds.), Parafrasi. Dalla ricerca linguistica alla ricerca psicolinguistica (pp. 169–206). Edizioni dell’Orso. [Google Scholar]

- Mereu, D., & Dal Negro, S. (2025). Pragmatic functions and phonetic reduction: Cioè and ce in contemporary spoken Italian. Journal of Pragmatics, 236, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurant, L., Sinte, A., & Gabarró-López, S. (2022). A multimodal approach to reformulation. Contrastive study of French and French Belgian Sign language through the productions of speakers, signers and interpreters. Languages in Contrast, 22(2), 322–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miestamo, M. (2017). Linguistic diversity and complexity. Lingue e Linguaggio, 16(2), 227–253. [Google Scholar]

- Molinelli, P. (2010). Le strutture coordinate. In G. Salvi, & L. Renzi (Eds.), Grammatica dell’italiano antico (Vol. II, pp. 241–271). Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Murillo Ornat, S. (2007). A contribution to the pragmalinguistic contrastive study of explicatory reformulative discourse markers in contemporary journalistic written English and Spanish [Doctoral dissertation, Universidad de Zaragoza]. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo Llibrer, A. (2025). La oralidad en las cartas desde el frente durante la Guerra de España: Prolegómenos de un estudio diacrónico del siglo XX a través de la epistolografía bélica. In A. Aguete, L. Domínguez, & L. Fernández (Eds.), Filología e innovación: Aproximaciones lingüísticas, literarias y culturales (pp. 249–269). Visor Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Pons Borderìa, S., & Salameh Jiménez, S. (2024). From synchrony to diachrony: The study of the 20th century as a distinct place for language change. In S. Pons Borderìa, & S. Salameh Jiménez (Eds.), Language change in the 20th Century. Exploring micro-diachronic evolutions in Romance languages (pp. 1–6). Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Pons Bordería, S. (2013). Un solo tipo de reformulación. Cuadernos AISPI, 2, 151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Procacci, G. (2000). Soldati e prigionieri italiani nella Grande guerra. Bollati Boringhieri. [Google Scholar]

- Regis, R. (2016). Contributo alla definizione del concetto di ibridismo: Aspetti strutturali e sociolinguistici. In V. Orioles, & R. Bombi (Eds.), Lingue in contatto. Atti del XLVIII congresso internazionale di studi della Società di Linguistica Italiana (pp. 215–230). Bulzoni. [Google Scholar]

- Rossari, C. (1990). Projet pour une typologie des opérations de reformulation. Cahiers de Linguistique Française, 11, 345–359. [Google Scholar]

- Rossari, C. (1994). Les operations de reformulation: Analyse du processus et des marques dans une perspective contrastive français-italien. Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Rossari, C., Chessex, J., Ricci, C., & Sanvido, L. (2022). La reformulation paraphrastique dans le discours à visée informative: Étude sur corpus avec une perspective comparative français-italien. Éla. Études de Linguistique Appliquée, 207, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulet, E. (1987). Complétude interactive et connecteurs réformulatifs. Cahiers de Linguistique Française, 8, 111–140. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, A. (2024). Dall’anteposizione spazio-temporale al contrasto: Lo sviluppo diacronico dei connettivi avversativi anziché e anzi. Cuadernos de Filología Italiana, 31, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainz, E. (2014). El reformulador italiano anzi y sus formas equivalentes en español. In E. Sainz (Ed.), De la estructura de la frase al tejido del discurso (pp. 141–175). Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Salameh Jiménez, S. (2021). Reframing reformulation: A theoretical-experimental approach. Evidence from the sp. discourse marker o sea. Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin, D. (1987). Discourse markers. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scivoletto, G. (2023). Il siciliano bì e l’espressione della miratività. Cuadernos de Filología Italiana, 30, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scivoletto, G. (2024). Una guerra con la lingua. L’italiano popolare in un epistolario siciliano (1915–1919). Centro di studi filologico e linguistici siciliani. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, L. (1921). Italienische kriegsgefangenenbriefe. Materialien zu einer charakteristik der volkstümlichen italienischen korrespondenz. Hanstein. [Google Scholar]

- Traugott, C. E. (2022). Discourse structuring markers in english: A historical constructionalist perspective on pragmatics. Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Trudgill, P. (2009). Sociolinguistic typology and complexification. In G. Sampson, D. Gil, & P. Trudgill (Eds.), Language complexity as an evolving variable (pp. 98–109). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Visconti, J. (2015). La diacronia di anzi: Considerazioni teoriche, dati e prime ipotesi. Cuadernos de Filología Italiana, 22, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visconti, J. (2021). Anzi: Dalla realtà eventiva all’interazione. Studi Italiani di Linguistica Teorica e Applicata, 50(1), 196–211. [Google Scholar]

- Voghera, M. (2017). Dal parlato alla grammatica. Costruzione e forma dei testi spontanei. Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- VS = Piccitto, G., Tropea, G., & Trovato, S. C. (Eds.). (1977–2002). VS = Vocabolario siciliano (5 vols.). Centro di studi filologici e linguistici siciliani. [Google Scholar]

| N | Context | Text5 | Type (Token) |

|---|---|---|---|

| i | il grano ancora non l’ho trebiato, cioè non l’ho ancora pisato | Letter from Giorgio to his son Angelo (2.7.1915) | cioè (cioè) |

| ii | noi non abbiamo ancora trebiato, cioè pisato | Postcard from Giorgio to his son Angelo (9.7.1915) | cioè (cioè) |

| iii | perché non scrivi con cartolina militare cioè del Regio Esercito | Postcard from Giorgio to his son Angelo (9.7.1915) | cioè (cioè) |

| iv | Carisimo padre, vi scrivo giove rispondo ala vostra cartolina | Postcard from Angelo to his father (26.4.1916) | cioè (giove) |

| v | vi fo sapere che parllo peri la mia sfoltuna, ciove dela mia leceza | Postcard from Angelo to his father (21.8.1917) | cioè (ciove) |

| vi | da molto tempo, che non ricevo notizie vostre, cioè dal giorno 15 corrente mese | Postcard from Antonino to his parents (28.2.1918) | cioè (cioè) |

| vii | apena arivo vicino dove erovava, ciove dove mi trovava io | Letter from Raimondo to his father (31.5.1919) | cioè (ciove) |

| viii | avete fatte tutto con la vostra idealità, di vostro sapere. Cioè, che avete fatto come cuando io non era al mondo | Letter from Angelo F. to his friend (11.9.1919) | cioè (Cioè) |

| ix | questa lettera, che tu mi ai mantato, ora mi là dovevi mandare nel principio, da quando tù avevi questa idea, cioè questo penziero | Letter from Angelo F. to his friend (11.9.1919) | cioè (cioè) |

| x | caro sogero, io credo che sono stato ubidiente sempre apresso a voi e sempre spero esere, anzi meglio | Postcard from Giovanni G. to his father-in-law (24.5.1917) | anzi (anzi) |

| xi | ne ho ricevute 4 che subito ti ho risposto, anzi senza riceverne io ti ho scritto | Letter from Giorgio to his son Angelo (28.6.1915) | anzi (anzi) |

| xii | io subito ti scrivo perché mi o madato a prendere il tuo derizio, anze ti facio sapere che stanno tutti bene di saluti | Postcard from Antonino to his brother Raimondo (12.5.1919) | anzi (anze) |

| xiii | dopo 40 mese di campagna mi fano cueso parllare, oldire che se uno che ave bona volondà di fare il sirivizio per cuesto campia peziero | Postcard from Angelo to his father (21.8.1917) | vuol dire (oldire) |

| xiv | uno che ave bona volondà di fare il sirivizio per cuesto campia peziero, oldire a 60 mese che facio il soldato, l’ho fato e oro se non mi mandono [...] | Postcard from Angelo to his father (21.8.1917) | vuol dire (oldire) |

| xv | Cara Maruza o capito che faceste 3 tomele di formende e non di potevito calare, ordire che mage asai e sei molto grosa | Postcard from Orazio to his wife (8.7.1918) | vuol dire (ordire) |

| Type | Equivalent Form in Standard Italian | Equivalent Form in Sicilian | Diachronic Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| cioè (9 occurrences by 5 writers) | cioè | / | Italian: ciò è (‘that is’) |

| anzi (3 occurrences by 3 writers) | anzi | anzi | Latin: ante (‘in front of, before, in contrast to’) |

| vuol dire (3 occurrences by 2 writers) | / (cf. voglio dire, lit. ‘I want to say’) | voddiri | Sicilian: vo’ diri (lit. ‘it wants to say’) |

| Reformulation Markers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sicilian [source] | italiano popolare | Standard Italian [target] | ||

| [vordiri, anzi, etc.] | cioè | [cioè, anzi, etc.] | ||

| ciove | ||||

| giove | ||||

| anzi | ||||

| anze | ||||

| oldire | ||||

| ordire | ||||

| Instances of Reformulation | ||

|---|---|---|

| + orality – writing  – orality + writing | disfluent uses |

|

| in-between uses |

| |

| strategic uses |

| |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Scivoletto, G. Reformulation in Early 20th Century Substandard Italian. Languages 2025, 10, 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070165

Scivoletto G. Reformulation in Early 20th Century Substandard Italian. Languages. 2025; 10(7):165. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070165

Chicago/Turabian StyleScivoletto, Giulio. 2025. "Reformulation in Early 20th Century Substandard Italian" Languages 10, no. 7: 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070165

APA StyleScivoletto, G. (2025). Reformulation in Early 20th Century Substandard Italian. Languages, 10(7), 165. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10070165