Listening for Region: Phonetic Cue Sensitivity and Sociolinguistic Development in L2 Spanish

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Dialect Identification

2.1. Regional Variation and Dialect Recognition

2.2. Second Language Dialect Identification

2.3. Current Study and Research Questions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Tasks

3.1.1. Dialect Identification Task

3.1.2. Language Background Questionnaire and Grammar Task

3.2. Participants

3.3. Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Dialect Identification

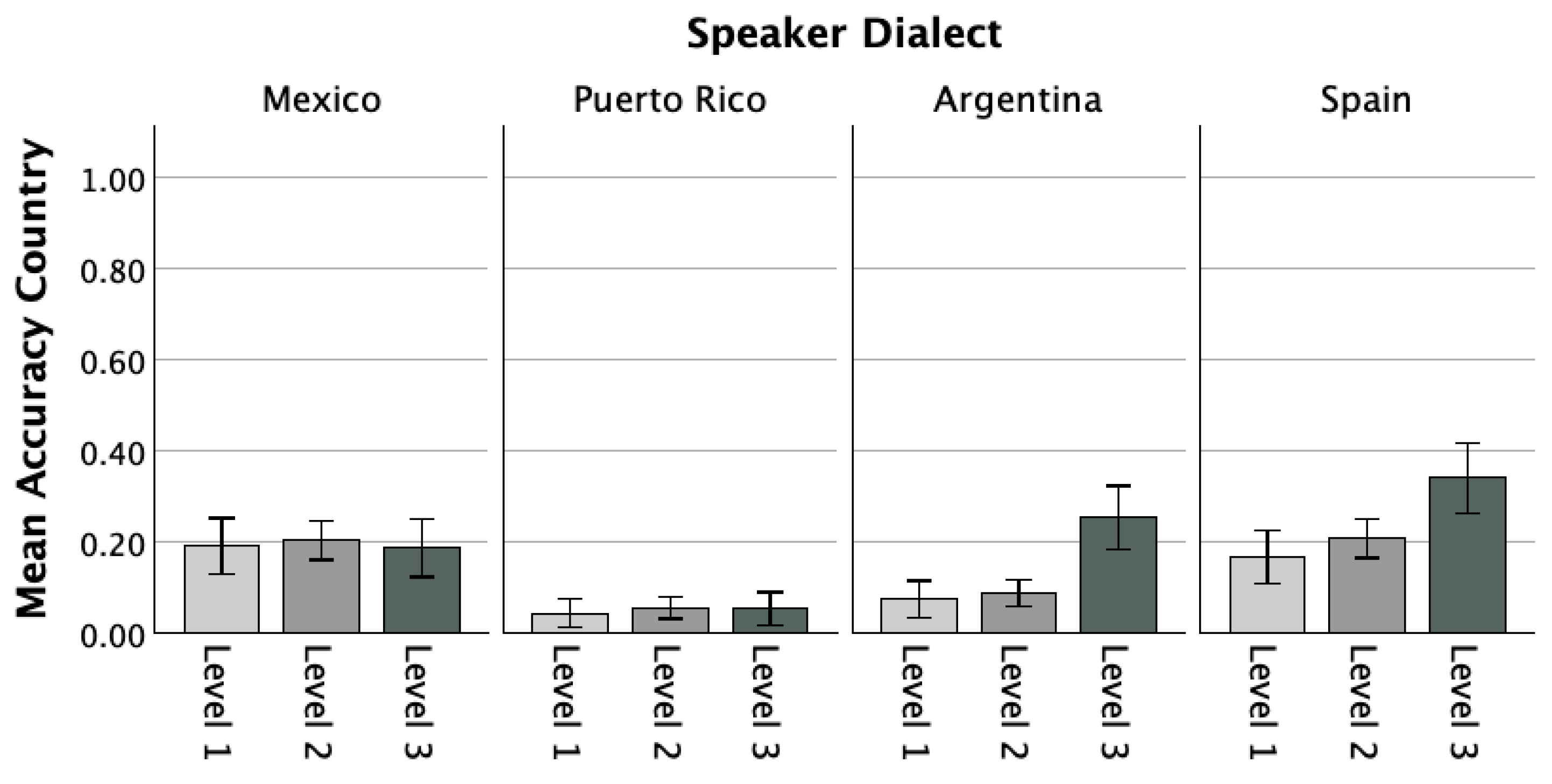

4.2. L2 Development of Dialect Identification

4.3. Phonetic Cue Use in Spanish Dialect Identification

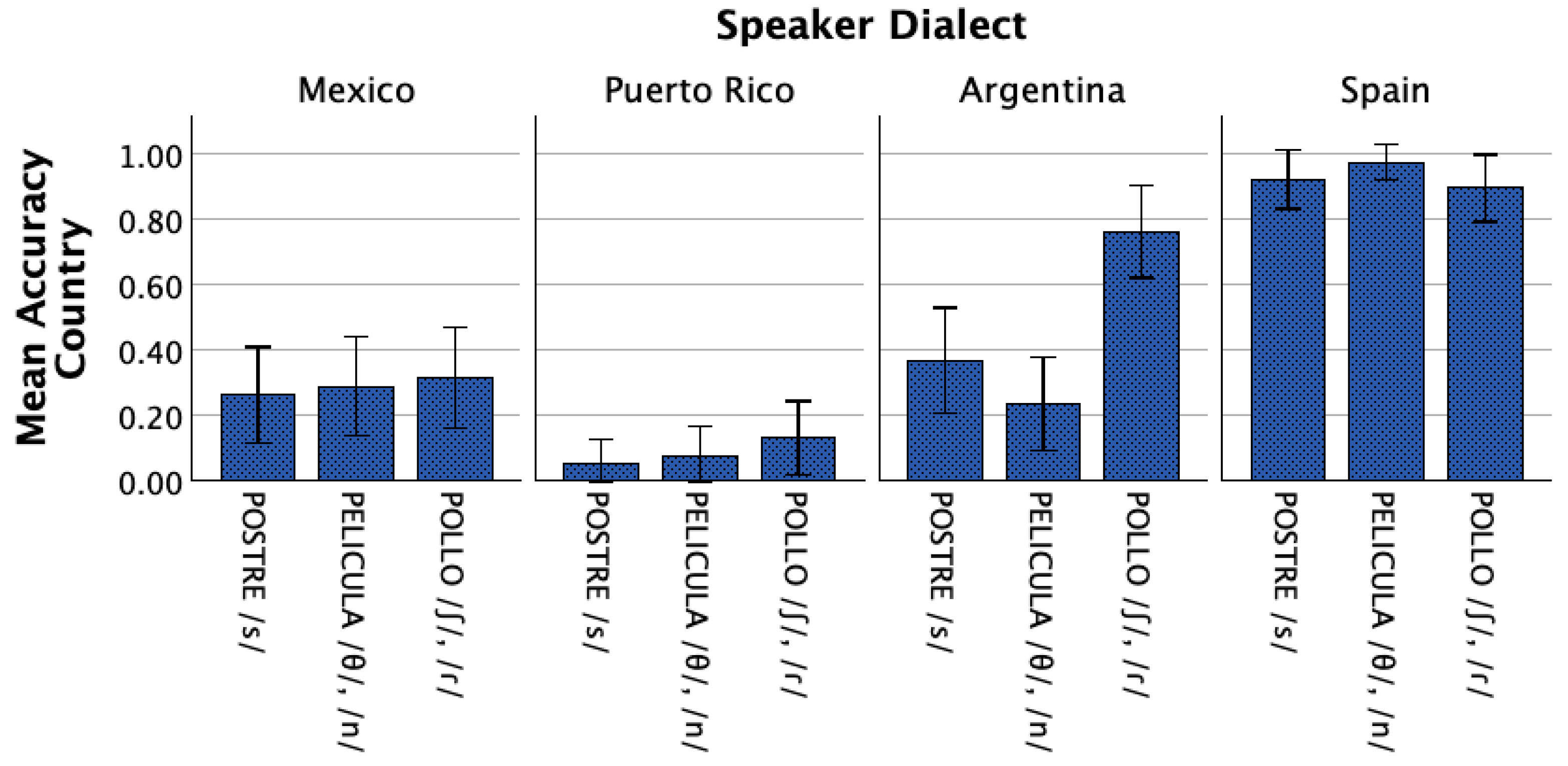

4.4. L2 Development in Phonetic Cue Use

5. Discussion

5.1. L2 Dialect Identification in Spanish

5.2. L2 Use of Sociphonetic Cues in Dialect Identification in Spanish

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The term country is used throughout for consistency and simplicity, including Puerto Rico, which, while an unincorporated U.S. territory and not a sovereign nation, is treated here as a distinct geopolitical entity due to its unique sociolinguistic profile. |

| 2 | Mexico and Spain each represent both an individual country and a macrodialect in this analysis. Unlike the Caribbean and Rioplatense groups, where a nearby variety could still be counted as correct at the macrodialect level, no such overlap applies to Mexico or Spain, which creates an asymmetry in scoring that may contribute to lower macrodialect identification rates for these varieties. |

| 3 | L2 proficiency and cue use were analyzed separately from NS to isolate developmental patterns. NS perceptual patterns are expected to vary across native speech communities. |

| 4 | Certainly, other types of linguistic features are unique and distinctive to Mexico, such as the use of the pronoun le for affective/emphatic purposes (e.g., échale ganas ‘give it your best’), and may similarly ‘linguistically mark’ Mexican Spanish. |

References

- Alba, M. (2004). Fonética y fonología del español moderno: Guía didáctica. Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo. [Google Scholar]

- Bardovi-Harlig, K. (2001). Evaluating the empirical evidence: Grounds for instruction in pragmatics? In K. R. Rose, & G. Kasper (Eds.), Pragmatics in language teaching (pp. 13–32). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, S. (2015). Perceptual salience and social categorization of contact features in Asturian Spanish. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics, 8(2), 213–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, J. (2006). From usage to grammar: The mind’s response to repetition. Language, 82(4), 711–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Kibler, K. (2010). The sociolinguistic variant as a carrier of social meaning. Language Variation and Change, 22(3), 423–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1(1), 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrie, E., & McKenzie, R. M. (2018). American or British? L2 speakers’ recognition and evaluations of accent features in English. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 39(4), 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casasanto, D. (2008). Embodiment of abstract concepts: Good and bad in right-and left-handers. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 137(3), 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, W., & Kanwit, M. (2022). Do learners connect sociophonetic variation with regional and social characteristics?: The case of L2 perception of Spanish aspiration. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 44(1), 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L., & Schleef, E. (2010). The acquisition of sociolinguistic competence by German learners of English: A study of dialect comprehension and attitudes. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 14(5), 588–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clopper, C., & Bradlow, A. (2009). Free classification of American English dialects by native and non-native listeners. Journal of Phonetics, 37, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clopper, C. G., & Pisoni, D. B. (2004). Homebodies and army brats: Some effects of early linguistic experience and residential history on dialect categorization. Language Variation and Change, 16(1), 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clopper, C. G., & Pisoni, D. B. (2007). Free classification of regional dialects of American English. Journal of Phonetics, 35(3), 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coveney, A. (1996). Variability in spoken French: A sociolinguistic study of interrogation and negation. Elm Bank Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham-Andersson, U. (1996). Learning to interpret sociodialectal cues. Speech, Music, and Hearing: Quarterly Progress and Status Report, 37(2), 155–158. [Google Scholar]

- Dellwo, V., Leemann, A., & Kolly, M.-J. (2015). The role of segments and prosody in the identification of a speaker’s regional origin. Journal of Phonetics, 48, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J.-M. (2004). The acquisition of sociolinguistic competence in French as a foreign language: An overview. In F. Myles, & R. Towell (Eds.), The acquisition of French as a second language (pp. 120–139). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Campos, M., & Navarro-Galisteo, I. (2009). Perceptual categorization of dialect variation in Spanish. In J. Collentine, M. García, B. Lafford, & F. Marcos Marín (Eds.), Selected proceedings of the 11th hispanic linguistics symposium (pp. 179–195). Cascadilla Proceedings Project. [Google Scholar]

- Dossey, E., Clopper, C. G., & Wagner, L. (2020). The development of sociolinguistic competence across the lifespan: Three domains of regional dialect perception. Language Learning and Development, 16(4), 330–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drager, K. (2005). From bad to bed: The relationship between perceived merger and speech production. Te Reo, 48, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Drager, K. (2010). Sociophonetic variation in speech perception. Language and Linguistics Compass, 4(7), 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, M. (1982). A study of social variation in adult second language acquisition. Language Learning, 32(2), 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, M. (1986). Target language variation and second-language acquisition: Learning English in New York City. World Englishes, 5, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- File-Muriel, R. (2009). Acoustic cues of lenition in the Spanish of Barranquilla, Colombia. Hispania, 92(4), 850–872. [Google Scholar]

- Friesner, M., & Dinkin, A. J. (2006, May 27–30). The acquisition of sociolinguistic competence in a study abroad context: The case of L2 learners of French. 2006 Annual Conference of the Canadian Linguistic Association, North York, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, P., Coupland, N., & Williams, A. (2003). Investigating language attitudes: Social meanings of dialect, ethnicity and performance. University of Wales Press. [Google Scholar]

- George, A. (2014). Study abroad in central Spain: The development of regional phonological features. Foreign Language Annals, 47(1), 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, G. P. (2024). Categorization of second-language accents by bilingual and multilingual listeners. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 42(3), 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, L. M. (1987). The role of language exposure in second language phonological acquisition [Doctoral Dissertation, Cornell University]. [Google Scholar]

- Gooskens, C. S., & van Bezooijen, R. (1999). Identification of language varieties: The contribution of different linguistic levels. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 18(1), 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmestad, A., & Kanwit, M. (2025). Reconsidering the social in language learning: A state of the science and an agenda for future research in variationist SLA. Languages, 10(4), 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen Edwards, J. (2020). The acquisition of English L2 sociolinguistic variation. In D. Edmonds-Wathen, & S. Chelliah (Eds.), The routledge handbook of language revitalization (pp. 485–495). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, J., & Drager, K. (2010). Stuffed toys and speech perception. Linguistics, 48(4), 865–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henríquez Ureña, P. (1921). Observaciones sobre el español en América. Revista de Filología Española, 8, 357–390. [Google Scholar]

- Hualde, J. I. (2005). The sounds of Spanish. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvella, R., Bang, E., Jakobsen, A. L., & Mees, I. M. (2001). Of mouths and men: Non-native listeners’ identification and evaluation of varieties of English. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 11, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, I., Ender, A., & Kasberger, G. (2019). Varietäten des österreichischen Deutsch aus der HörerInnenperspektive: Diskriminations-fähigkeiten und sozio-indexikalische. In L. Bülow, A. Fischer, & K. Herbert (Eds.), Dimensionen des sprachlichen Raums: Variation—Mehrsprachigkeit—Konzeptualisierung (pp. 341–362). Peter Lang Verlag. Schriften zur deutschen Sprache in Österreich. [Google Scholar]

- Kissling, E. M. (2015). Teaching pronunciation: Is explicit phonetics instruction beneficial for FL learners? The Modern Language Journal, 99(3), 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labov, W. (1990). The intersection of sex and social class in the course of linguistic change. Language Variation and Change, 2(2), 205–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladegaard, H. J. (1998). National stereotypes and language attitudes: The perception of British, American and Australian language and culture in Denmark. Language and Communication, 18(4), 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, H., & O’Brien, M. G. (2014). Perceptual dialectology in second language learners of German. System, 46, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. (2010). Sociolinguistic variation in the speech of learners of Chinese as a second language. Language Learning, 60(2), 366–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipski, J. M. (1994). Latin American Spanish. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, G. (2010). The combined effects of immersion and instruction on second language pronunciation. Foreign Language Annals, 43(3), 488–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, S., & Munson, B. (2012). The influence of /s/ quality on ratings of men’s sexual orientation: Sounding gay and sounding straight. Journal of Phonetics, 40(1), 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, R. M. (2008). The role of variety recognition in Japanese university students’ attitudes towards English speech varieties. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 29(2), 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milroy, J., & Milroy, L. (1999). Authority in language: Investigating standard English. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mougeon, R., Nadasdi, T., & Rehner, K. (2010). The sociolinguistic competence of immersion students. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Niedzielski, N. (1999). The effect of social information on the perception of sociolinguistic variables. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 18(1), 62–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics. (2015). Qualtrics [Computer software]. Qualtrics. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Regan, B. (2022). Individual differences in the acquisition of language-specific and dialect-specific allophones of intervocalic /d/ by L2 and heritage Spanish speakers studying abroad in Sevilla. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 45(1), 65–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringer-Hilfinger, K. (2012). Learner acquisition of dialect variation in a study abroad context: The case of the Spanish [θ]. Foreign Language Annals, 45(3), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scales, J., Wennerstrom, A., Richard, D., & Wu, S. H. (2006). Language learners’ perceptions of accent. TESOL Quarterly, 40(4), 715–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L. B. (2022). L2 development of dialect awareness in Spanish. Hispania, 105(2), 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L. B., & Geeslin, K. L. (2022). Acquisition of linguistic competence: Development of sociolinguistic evaluations of regional varieties in a second language. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada, 35(1), 206–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonmaker-Gates, E. (2017). Regional variation in the language classroom and beyond: Mapping learners’ developing dialectal competence. Foreign Language Annals, 50(1), 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonmaker-Gates, E. (2018). Dialect comprehension and identification in L2 Spanish: Familiarity and type of exposure. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics, 11(1), 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, M., & Kanwit, M. (2025). Exploring the relationship between preference and production as indicators of L2 sociophonetic competence. Languages, 10(4), 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, L. (2014). Processing, evaluation, knowledge: Testing the perception of English subject–verb agreement variation. Journal of English Linguistics, 42(2), 144–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, C. (1997). The unknown Englishes? Testing German students’ ability to identify varieties of English. In E. W. Schneider (Ed.), Englishes around the world: Studies in honour of manfred görlach (pp. 93–108). John Benjamins Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Strand, E. A. (1999). Uncovering the role of gender stereotypes in speech perception. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 18(1), 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, M., Kim, S. K., King, E., & McGowan, K. B. (2014). The socially weighted encoding of spoken words: A dual-route approach to speech perception. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarone, E., & Swain, M. (1995). A sociolinguistic perspective on second language use in immersion classrooms. The Modern Language Journal, 79(2), 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A., Garrett, P., & Coupland, N. (1999). Dialect recognition. In D. Preston (Ed.), Handbook of perceptual dialectology (Vol. 1, pp. 345–358). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, M. A., & Ender, A. (2025). Functional prestige in sociolinguistic evaluative judgements among adult second language speakers in Austria: Evidence from perception. Languages, 10(4), 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # (No.) | Stimulus |

|---|---|

| 1 (POSTRE) | Pablo pidió un postre de chocolate para la fiesta. ‘Pablo ordered a chocolate dessert for the party.’ |

| 2 (PELÍCULA) | La nueva película de acción glorificó a la nación. ‘The new action film glorified the nation.’ |

| 3 (POLLO) | Comí pollo y carne en la calle del norte. ‘I ate chicken and meat on north street.’ |

| Dialect | Macrodialect | POSTRE | PELÍCULA | POLLO |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico a | Mexican | (maintained-) laminal-/s/ postre [ˈpos-tɾe] | seseo acción [ak-ˈsi̯on] | yeísmo pollo [ˈpo-ʝo] |

| Puerto Rico | Caribbean | lenited-/s/ b postre [ˈpo-tɾe] | seseo; velar-/n/ acción [ak-ˈsi̯oŋ] | yeísmo; lambdacism pollo [ˈpo-ʝo]; carne [ˈkal-ne] |

| Argentina | Rioplatense | aspirated-/s/ postre [ˈpoh-tɾe] | seseo acción [ak-ˈsi̯on] | assibilated palatal pollo [ˈpo-ʃo] |

| Spain | Castilian | apical-/s/ postre [ˈpos̪-tɾe] | interdental fricative acción [ak-ˈθi̯on] | yeísmo pollo [ˈpo-ʝo] |

| Group | n | M Age (SD) | Grammar Score M (SD, Range) | % Span Majors (n), Minors (n) | N Hours Span × Week | % Study Abroad (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2 Level 1 | 27 | 19.7 (1.34) | 6.9 (1.27; 3–8) | 7% (0, 2) | 1 (1.35) | 4% (1) |

| L2 Level 2 | 59 | 19.8 (1.39) | 11.2 (1.54; 9–14) | 49% (11, 18) | 2 (2.50) | 19% (11) |

| L2 Level 3 | 25 | 20.0 (1.35) | 17.6 (2.49; 15–23) | 92% (14, 9) | 2 (2.43) | 68% (17) |

| NS (Spain) | 19 | 22.8 (5.10) | 23.1 (1.23; 19–24) | - | - | - |

| Group | n | Mexico Contact | Puerto Rico Contact | Argentina Contact | Spain Contact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L2 Level 1 | 27 | 30% (8) | 11% (3) | 4% (1) | 15% (4) |

| L2 Level 2 | 59 | 49% (29) | 19% (11) | 9% (5) | 32% (19) |

| L2 Level 3 | 25 | 68% (17) | 12% (3) | 24% (6) | 72% (18) |

| NS (Spain) | 19 | 5% (1) | 0% (0) | 37% (7) | 100% (19) |

| Dialect (Country/Macrodialect) | L2 Accuracy Country 1 | L2 Accuracy Macrodialect 2 | NS Accuracy Country 1 | NS Accuracy Macrodialect 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico/Mexico | 19.7% (39.6) | 19.7% (39.6) | 28.9% (45.6) | 28.9% (45.6) |

| Puerto Rico/Caribbean | 5.3% (22.2) | 17.5% (38.0) | 8.8% (28.4) | 46.5% (50.1) |

| Argentina/Rioplatense | 12.2% (32.5) | 18.8% (39.1) | 45.6% (50.0) | 57.0% (49.7) |

| Spain/Spain | 22.7% (41.9) | 22.7% (41.9) | 93.0% (25.7) | 93.0% (25.7) |

| Total | 14.9% (35.6) | 19.6% (39.7) | 44.1% (49.7) | 56.4% (49.6) |

| Dialect | Sentence | Targeted Feature | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | POSTRE | laminal-s | 22% (42.0) | 16% (36.9) | 12% (32.8) |

| PELÍCULA | seseo | 22% (42.0) | 27% (44.6) | 22% (41.8) | |

| POLLO | yeísmo | 13% (33.9) | 18% (38.4) | 22% (41.8) | |

| Puerto Rico | POSTRE | lenited-s | 0% (0.0) | 7% (25.2) | 8% (27.3) |

| PELÍCULA | velarized-n | 7% (26.3) | 6% (23.7) | 4% (19.8) | |

| POLLO | lambdacism | 6% (23.0) | 4% (19.2) | 4% (19.7) | |

| Argentina | POSTRE | aspirated-s | 4% (19.0) | 4% (20.2) | 10% (30.4) |

| PELÍCULA | seseo | 7% (26.3) | 7% (25.2) | 2% (14.1) | |

| POLLO | assib. palatal /ʃ/ | 11% (31.6) | 15% (36.0) | 62% (48.8) | |

| Spain | POSTRE | apical-s | 4% (19.0) | 3% (18.1) | 6% (24.0) |

| PELÍCULA | inter. fric. /θ/ | 43% (49.7) | 46% (49.9) | 88% (32.7) | |

| POLLO | yeísmo | 4% (19.0) | 13% (33.4) | 8% (27.3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schmidt, L.B. Listening for Region: Phonetic Cue Sensitivity and Sociolinguistic Development in L2 Spanish. Languages 2025, 10, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080198

Schmidt LB. Listening for Region: Phonetic Cue Sensitivity and Sociolinguistic Development in L2 Spanish. Languages. 2025; 10(8):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080198

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchmidt, Lauren B. 2025. "Listening for Region: Phonetic Cue Sensitivity and Sociolinguistic Development in L2 Spanish" Languages 10, no. 8: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080198

APA StyleSchmidt, L. B. (2025). Listening for Region: Phonetic Cue Sensitivity and Sociolinguistic Development in L2 Spanish. Languages, 10(8), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages10080198