Plant Hormone Stimulation and HbHSP90.3 Plays a Vital Role in Water Deficit of Rubber Tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Cloning and Expression Analysis of HbHSP90.3

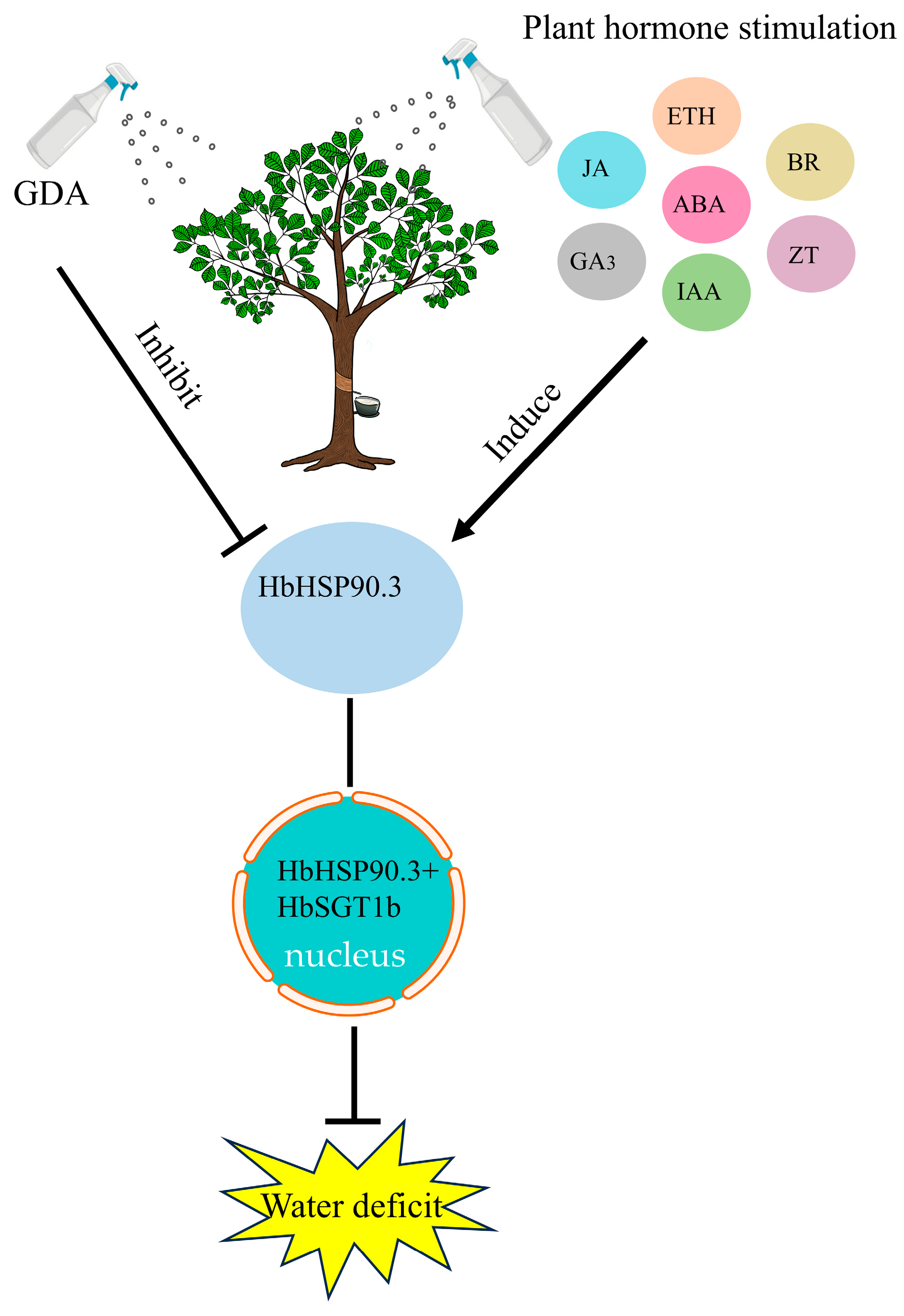

2.2. HbHSP90.3 Relieves Rubber Tree Water Deficit

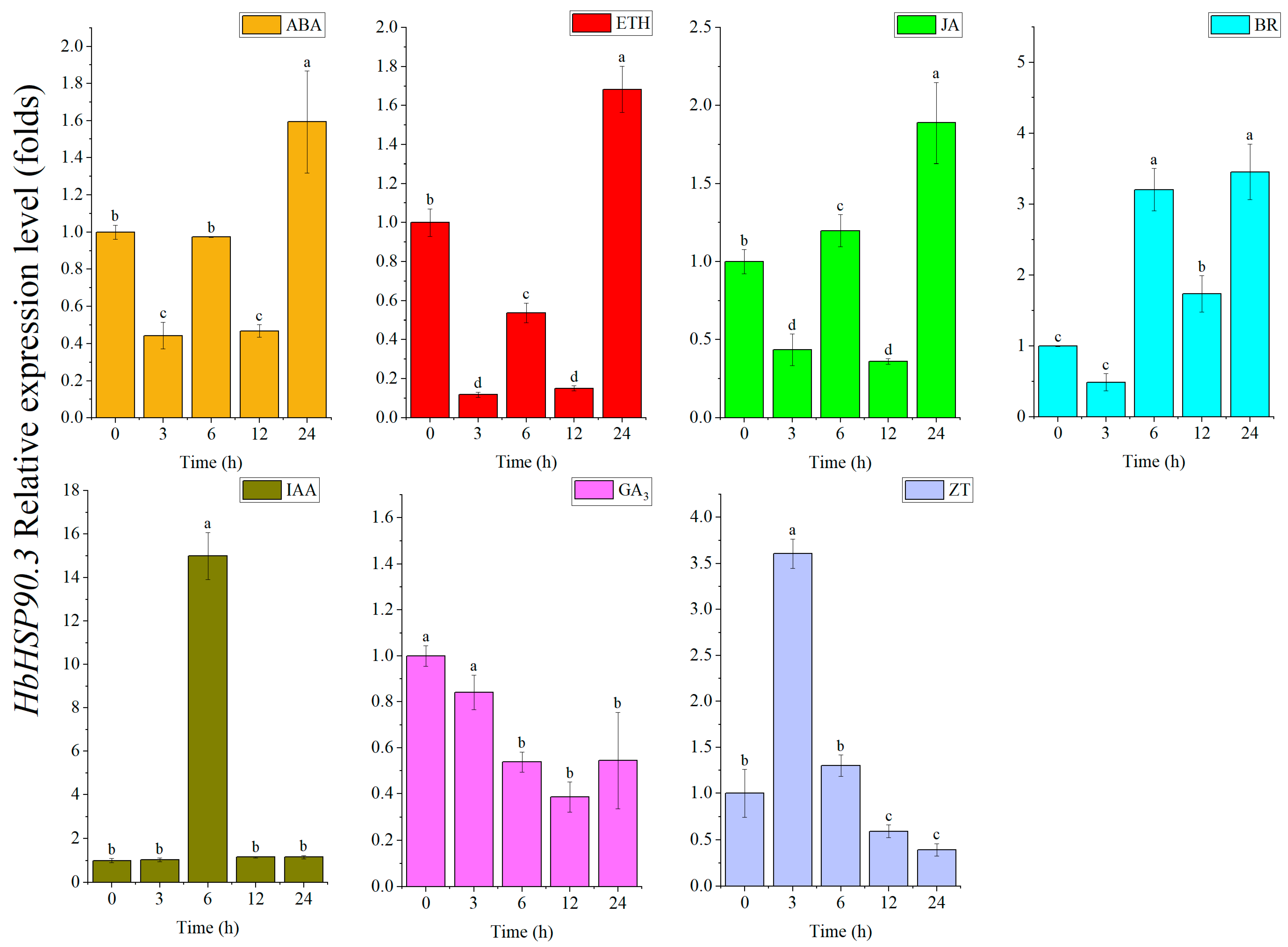

2.3. HbHSP90.3 Gene Responds to Plant Hormone Treatments

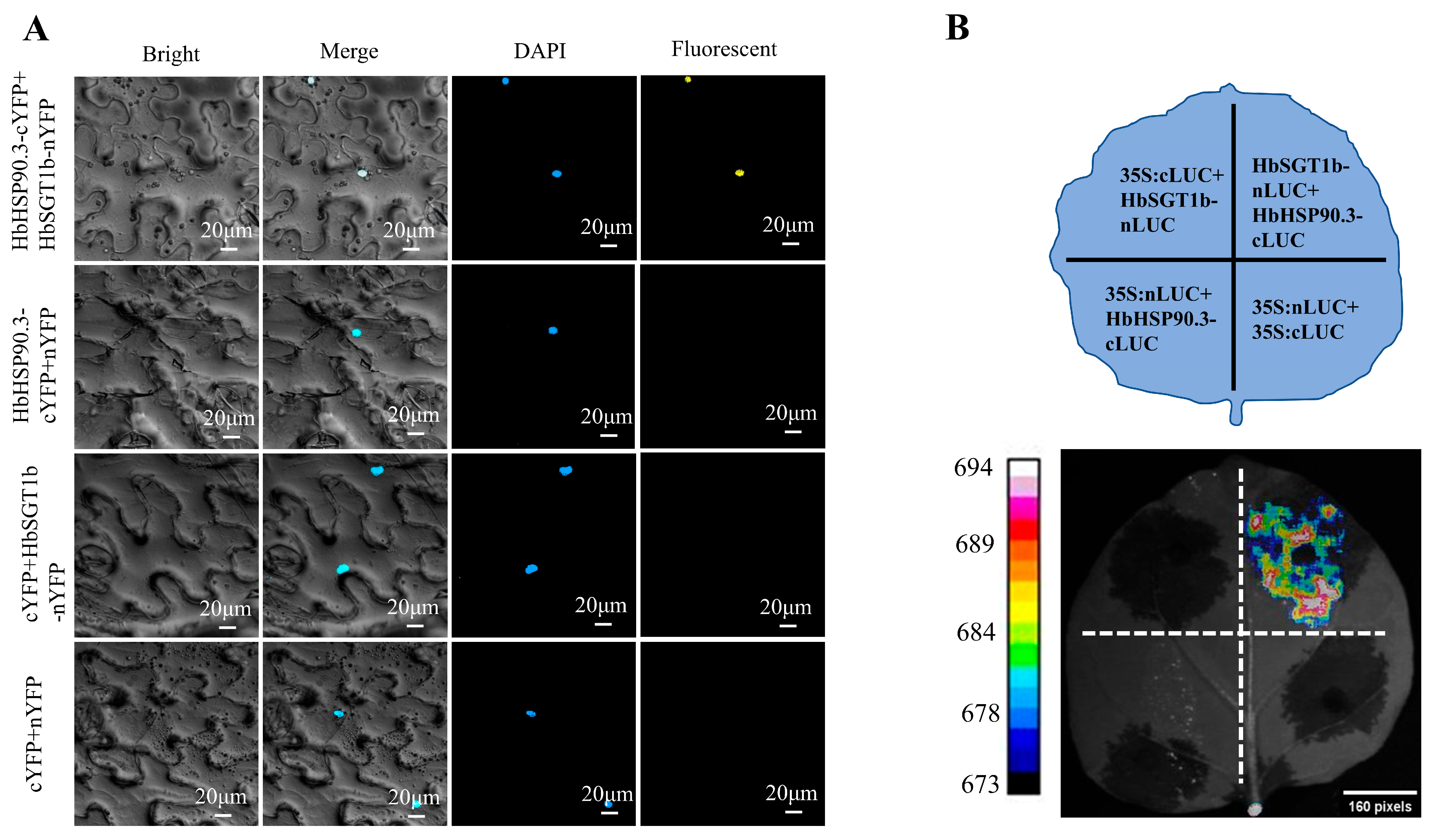

2.4. HbHSP90.3 and HbSGT1b Interacted in Tobacco Nucleus

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

4.2. Yeast Expression and Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) Analysis

4.3. Luciferase Complementation Assay (LCA)

4.4. Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation (BiFC) Assay

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agrawal, A.A.; Konno, K. Latex: A model for understanding mechanisms, ecology, and evolution of plant defense against herbivory. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2009, 40, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-F. Physiological and molecular responses to drought stress in rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 83, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, H.; Huang, X. Chilling-induced DNA Demethylation is associated with the cold tolerance of Hevea brasiliensis. BMC Plant Biol. 2018, 18, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, J.; Herbette, S.; Vandame, M.; Cavaloc, E.; Julien, J.L.; Ameglio, T.; Roeckel-Drevet, P. Contrasting strategies to cope with chilling stress among clones of a tropical tree, Hevea brasiliensis. Tree Physiol. 2010, 30, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.; Yang, M.; Fang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Gao, S.; Xiao, X.; An, Z.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, B.; Tan, X.; et al. The rubber tree genome reveals new insights into rubber production and species adaptation. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Lin, J.; Lin, Q.; Wang, J.; Liu, K.; Li, Z.; Xing, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; et al. Pan-genome and phylogenomic analyses highlight Hevea species delineation and rubber trait evolution. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 7232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tungngoen, K.; Viboonjun, U.; Kongsawadworakul, P.; Katsuhara, M.; Julien, J.L.; Sakr, S.; Chrestin, H.; Narangajavana, J. Hormonal treatment of the bark of rubber trees (Hevea brasiliensis) increases latex yield through latex dilution in relation with the differential expression of two aquaporin genes. J. Plant Physiol. 2011, 168, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.J.; Cai, F.G.; Tian, W.M. Ethrel-stimulated prolongation of latex flow in the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.): An Hev b 7-like protein acts as a universal antagonist of rubber particle aggregating factors from lutoids and C-serum. J. Biochem. 2016, 159, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.M.; Guo, D.; Yang, S.G.; Shi, M.J.; Chao, J.Q.; Li, H.L.; Peng, S.Q.; Tian, W.M. Jasmonate signalling in the regulation of rubber biosynthesis in laticifer cells of rubber tree, Hevea brasiliensis. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3559–3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Liu, M.; Yang, H.; Dai, L.; Wang, L. Brassinosteroids Regulate the Water Deficit and Latex Yield of Rubber Trees. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritonga, F.N.; Zhou, D.D.; Zhang, Y.H.; Song, R.X.; Li, C.; Li, J.J.; Gao, J.W. The Roles of Gibberellins in Regulating Leaf Development. Plants 2023, 12, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiosis, G.; Digwal, C.S.; Trepel, J.B.; Neckers, L. Structural and functional complexity of HSP90 in cellular homeostasis and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 797–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.-H.; Li, J.; Wang, T. Regulation of NLR stability in plant immunity. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2019, 6, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhao, R.; Fan, P.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Li, Y. Overexpression of AtHsp90.2, AtHsp90.5 and AtHsp90.7 in Arabidopsis thaliana enhances plant sensitivity to salt and drought stresses. Planta 2009, 229, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, L.H.; Ye, T.Z.; Chen, R.J.; Gao, X.L.; Xu, Z.J. Molecular characterization, expression pattern and function analysis of the OsHSP90 family in rice. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2016, 30, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Shen, Z.; Meng, G.; Lu, Y.; Wang, Y. Genome-wide analysis of the Brachypodium distachyon (L.) P. Beauv. Hsp90 gene family reveals molecular evolution and expression profiling under drought and salt stresses. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Fukao, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Fukazawa, M.; Suzuki, I.; Nishimura, M. Cytosolic HSP90 Regulates the Heat Shock Response That Is Responsible for Heat Acclimation in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 37794–37804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.H.; Li, W.; Wei, Z.; Qiao, Z.; Wu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Wang, Y. Proteomics Analysis of Alfalfa Response to Heat Stress. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozeko, L. Different roles of inducible and constitutive HSP70 and HSP90 in tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana to high temperature and water deficit. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2021, 43, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Wang, J.Y.; Huang, S.; Xie, Y.; Zhu, T.D.; Liu, L.Y.; Li, L. HSP90s are required for hypocotyl elongation during skotomorphogenesis and thermomorphogenesis via the COP1-ELF3-PIF4 pathway in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2023, 239, 1253–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queitsch, C.; Sangster, T.A.; Lindquist, S. Hsp90 as a capacitor of phenotypic variation. Nature 2002, 417, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangster, T.A.; Salathia, N.; Lee, H.N.; Watanabe, E.; Schellenberg, K.; Morneau, K.; Wang, H.; Undurraga, S.; Queitsch, C.; Lindquist, S. HSP90-buffered genetic variation is common in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2969–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samakovli, D.; Roka, L.; Dimopoulou, A.; Plitsi, P.K.; Zukauskaite, A.; Georgopoulou, P.; Novák, O.; Milioni, D.; Hatzopoulos, P. HSP90 affects root growth in Arabidopsis by regulating the polar distribution of PIN1. New Phytol. 2021, 231, 1814–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigeta, T.; Zaizen, Y.; Sugimoto, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Matsuo, T.; Okamoto, S. Heat shock protein 90 acts in brassinosteroid signaling through interaction with BES1/BZR1 transcription factor. J. Plant Physiol. 2015, 178, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.J.; Fan, P.X.; Jiang, P.; Lv, S.L.; Chen, X.Y.; Li, Y.X. Chloroplast-targeted Hsp90 plays essential roles in plastid development and embryogenesis in Arabidopsis possibly linking with IPP1. Physiol. Plant. 2014, 150, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, A.; Casais, C.; Ichimura, K.; Shirasu, K. HSP90 interacts with RAR1 and SGT1 and is essential for RPS2-mediated disease resistance in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 11777–11782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Xiao, H.; Li, X.; Wan, S.; Yang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, B. Functional characterization of powdery mildew resistance-related genes HbSGT1a and HbSGT1b in Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 165, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, W.M.; Muskett, P.R.; Chuang, H.W.; Parker, J.E. Arabidopsis SGT1b is required for SCF(TIR1)-mediated auxin response. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1310–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.H.; Zhang, Y.; Kieffer, M.; Yu, H.; Kepinski, S.; Estelle, M. HSP90 regulates temperature-dependent seedling growth in Arabidopsis by stabilizing the auxin co-receptor F-box protein TIR1. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontiveros, I.; Fernandez-Pozo, N.; Esteve-Codina, A.; Lopez-Moya, J.J.; Diaz-Pendon, J.A.; Aranda, M.A. Enhanced Susceptibility to Tomato Chlorosis Virus (ToCV) in Hsp90- and Sgt1-Silenced Plants: Insights from Gene Expression Dynamics. Viruses 2023, 15, 2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.Y.; Wang, L.F.; Ke, Y.H.; Xian, X.M.; Wang, J.L.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y. Identification of HbHSP90 gene family and characterization HbHSP90.1 as a candidate gene for stress response in rubber tree. Gene 2022, 827, 146475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korres, N.E.; Norsworthy, J.K.; Tehranchian, P.; Gitsopoulos, T.K.; Loka, D.A.; Oosterhuis, D.M.; Gealy, D.R.; Moss, S.R.; Burgos, N.R.; Miller, M.R.; et al. Cultivars to face climate change effects on crops and weeds: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Wang, X.; Xia, Z.; Deng, Z.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Yin, H.; Li, D. Bark transcriptome analyses reveals molecular mechanisms involved in tapping panel dryness occurrence and development in rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis). Gene 2024, 892, 147894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul Rahman, S.N.; Bakar, M.F.A.; Singham, G.V.; Othman, A.S. Single-nucleotide polymorphism markers within MVA and MEP pathways among Hevea brasiliensis clones through transcriptomic analysis. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkov, V.; Schwenke, H. A Quest for Mechanisms of Plant Root Exudation Brings New Results and Models, 300 Years after Hales. Plants 2021, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardieu, F. Plant response to environmental conditions: Assessing potential production, water demand, and negative effects of water deficit. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeang, H.Y. The kinetics of latex flow from the rubber tree in relation to latex vessel plugging and turgor pressure. J. Rubb. Res. 2005, 8, 160–181. [Google Scholar]

- Machado Costa, E.; Macedo Pezzopane, J.E.; Dan Tatagiba, S.; Miranda Teixeira Xavier, T.; De Souza Nóia Júnior, R.; Daniel Salgado, P.; Nair de Carvalho, J. Atmospheric evaporative demand and water deficit on the ecophysiology of Rubber seedlings. Biosci. J. 2022, 38, e38090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Woo, J.H.; Song, Y.; Lee, S.H.; Hasan, M.M.; Azad, M.A.; Lee, K.W. Heat Shock Proteins and Antioxidant Genes Involved in Heat Combined with Drought Stress Responses in Perennial Rye Grass. Life 2022, 12, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafqat, W.; Jaskani, M.J.; Maqbool, R.; Chattha, W.S.; Ali, Z.; Naqvi, S.A.; Haider, M.S.; Khan, I.A.; Vincent, C.I. Heat shock protein and aquaporin expression enhance water conserving behavior of citrus under water deficits and high temperature conditions. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2021, 181, 104270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, S.W.; Ren, Y.M.; You, Y.; Wang, Z.F.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhu, X.J.; Hu, P. Genome-wide identification of HSP90 gene family in Rosa chinensis and its response to salt and drought stresses. 3 Biotech 2024, 14, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.X.; Liu, W.; Hu, W.; Yan, Y.; Shi, H.T. The chaperone MeHSP90 recruits MeWRKY20 and MeCatalase1 to regulate drought stress resistance in cassava. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahan, M.S.; Hasan, M.M.; Rahman, M.A. Editorial: Hormones and biostimulants in plants: Physiological and molecular insights on plant stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1413659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, S.H.; Kumar, V.; Shriram, V.; Sah, S.K. Phytohormones and their metabolic engineering for abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Crop J. 2016, 4, 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, S.; Kudoyarova, G.R.; Veselov, D.S.; Arkhipova, T.N.; Davies, W.J. Plant hormone interactions: Innovative targets for crop breeding and management. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 3499–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, F.; Peter, P.; Gupta, R.; Kumari, S.; Nawaz, K.; Khan, M.I.R. Plant hormone ethylene: A leading edge in conferring drought stress tolerance. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Timko, M.P. Jasmonic Acid Signaling and Molecular Crosstalk with Other Phytohormones. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Chen, B.; Boubakri, H.; Farooq, M.; Mur, L.A.J.; Urano, D.; Teo, C.H.; Tan, B.C.; Hasan, M.D.M.; Aslam, M.M.; et al. The regulatory role of phytohormones in plant drought tolerance. Planta 2025, 261, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omena-Garcia, R.P.; Oliveira Martins, A.; Medeiros, D.B.; Vallarino, J.G.; Mendes Ribeiro, D.; Fernie, A.R.; Araújo, W.L.; Nunes-Nesi, A. Growth and metabolic adjustments in response to gibberellin deficiency in drought stressed tomato plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 159, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, P.E. Zeatin: The 60th anniversary of its identification. Plant Physiol. 2023, 192, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Donato, M.; Geisler, M. HSP90 and co-chaperones: A multitaskers’ view on plant hormone biology. FEBS Lett. 2019, 593, 1415–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, E.; Mano, S.; Nomoto, M.; Tada, Y.; Hara-Nishimura, I.; Nishimura, M.; Yamada, K. HSP90 Stabilizes Auxin-Responsive Phenotypes by Masking a Mutation in the Auxin Receptor TIR1. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 2245–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.C.; Millet, Y.A.; Cheng, Z.; Bush, J.; Ausubel, F.M. Jasmonate signalling in Arabidopsis involves SGT1b-HSP70-HSP90 chaperone complexes. Nat. Plants 2015, 1, 15049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.X.; Zeng, H.Q.; Liu, W.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, B.B.; Guo, J.R.; Shi, H.T. Autophagy-related genes serve as heat shock protein 90 co-chaperones in disease resistance against cassava bacterial blight. Plant J. 2021, 107, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, L.C.; Zhao, J.P.; Du, Y.M.; Zhao, X.J.; Han, M.; Liu, Y.L. Hsp90 Interacts With Tm-22 and Is Essential for Tm-22-Mediated Resistance to Tobacco mosaic virus. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, A.; Martinon, F.; De Smedt, T.; Pétrilli, V.; Tschopp, J. A crucial function of SGT1 and HSP90 in inflammasome activity links mammalian and plant innate immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Li, C.; Zhao, X.; Yan, C.; Wang, J.; Mou, Y.; Sun, Q.; Shan, S. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of HSP90-RAR1-SGT1-Complex Members From Arachis Genomes and Their Responses to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 689669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-F. Physiological and Molecular Responses to Variation of Light Intensity in Rubber Tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.; Fan, S.L.; Yu, H.Y.; Lu, Y.X.; Wang, L.F. HbMYB44, a Rubber Tree MYB Transcription Factor With Versatile Functions in Modulating Multiple Phytohormone Signaling and Abiotic Stress Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 893896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.B.; Fan, S.L.; Liu, M.Y.; Yang, H.; Dai, L.J.; Wang, L.F. ATP Synthase Members of Chloroplasts and Mitochondria in Rubber Trees (Hevea brasiliensis) Response to Plant Hormones. Plants 2025, 14, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khramov, D.E.; Nedelyaeva, O.I.; Konoshenkova, A.O.; Volkov, V.S.; Balnokin, Y.V. Identification and selection of reference genes for analysis of gene expression by quantitative real-time PCR in the euhalophyte Suaeda altissima (L.) Pall. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2024, 17, 2372313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, X.; Lu, J.; Kav, N.N.V.; Qin, Y.; Fang, Y. Identification and evaluation of suitable reference genes for gene expression analysis in rubber tree leaf. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 1921–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A.B.; Dobson, E.T.A.; Rueden, C.T.; Tomancak, P.; Jug, F.; Eliceiri, K.W. The ImageJ ecosystem: Open-source software for image visualization, processing, and analysis. Protein Sci. 2021, 30, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primers | Function | Sequences 5′–3′ |

|---|---|---|

| HbHSP90.3-QF | qRT-PCR | CTTGACCAACGACTGGGAGG |

| HbHSP90.3-QR | GCTCATTTTCTTGCGGGTGT | |

| HbACTIN-F | GATGTGGATATCAGGAAGGA | |

| HbACTIN-R | CATACTGCTTGGAGCAAGA | |

| HbHSP90.3-F | Yeast expression | CTTGGTACCGAGCTCGGATCCATGGCTGATGCTGAGACCTTCG |

| HbHSP90.3-R | TAGATGCATGCTCGAGCGGCCGCTTAGTCGACTTCCTCCATCTTGC | |

| HbHSP90.3-F | BiFC | TGGCGCGCCACTAGTGGATCCATGGCTGATGCTGAGACCTTCG |

| HbHSP90.3-R | GTACATCCCGGGAGCGGTACCGTCGACTTCCTCCATCTTGCTC | |

| HbSGT1b-F | CCCAGGCCTACTAGTGGATCCATGGCGTCTGATCTCGAAAGG | |

| HbSGT1b-R | CTCCTACCCGGGAGCGGTACCTCAATACTCCCATTTCTTCACCTCC | |

| HbHSP90.3-F | LCA | TACGCGTCCCGGGGCGGTACCATGGCTGATGCTGAGACCTTCG |

| HbHSP90.3-R | TGTAGTCCATTTGTTGGATCCTTAGTCGACTTCCTCCATCTTGC | |

| HbSGT1b-F | GTCGACGGTATCGATAAGCTTATGGCGTCTGATCTCGAAAGG | |

| HbSGT1b-R | TTTACTCATACTAGTGGATCCATACTCCCATTTCTTCACCTCCAT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, M.; Fan, S.; Wang, C.; Guo, B.; Yang, H.; Phen, P.; Wang, L. Plant Hormone Stimulation and HbHSP90.3 Plays a Vital Role in Water Deficit of Rubber Tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.). Plants 2025, 14, 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233679

Liu M, Fan S, Wang C, Guo B, Yang H, Phen P, Wang L. Plant Hormone Stimulation and HbHSP90.3 Plays a Vital Role in Water Deficit of Rubber Tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.). Plants. 2025; 14(23):3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233679

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Mingyang, Songle Fan, Cuicui Wang, Bingbing Guo, Hong Yang, Phearun Phen, and Lifeng Wang. 2025. "Plant Hormone Stimulation and HbHSP90.3 Plays a Vital Role in Water Deficit of Rubber Tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.)" Plants 14, no. 23: 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233679

APA StyleLiu, M., Fan, S., Wang, C., Guo, B., Yang, H., Phen, P., & Wang, L. (2025). Plant Hormone Stimulation and HbHSP90.3 Plays a Vital Role in Water Deficit of Rubber Tree (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.). Plants, 14(23), 3679. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233679